Introduction

Embryo implantation, a critical event in early pregnancy, typically occurs between days 9 and 13 of pregnancy in sows (Ye et al. Reference Ye, Zeng and Cai2021a). Implantation failure during this period is a major cause of early embryo loss and represents a major limiting factor for litter size in sows, with approximately 30–50% of embryonic loss occurring at this stage (Geisert and Schmitt Reference Geisert and Schmitt2002). The steroid hormones estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4) play essential roles in regulating the uterine microenvironment to support pregnancy and promote implantation by ensuring conditions favorable for embryo survival, development, and attachment (Dias Da Silva et al. Reference Dias Da Silva, Wuidar and Zielonka2024). Meanwhile, E2 and P4 maintain appropriate reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels by regulating redox homeostasis in the uterus during the pre-implantation period, and such physiological levels of ROS are involved in the regulation of embryo development (Luo et al. Reference Luo, Yao and Xu2021). However, during implantation, the marked increase in metabolic activity in the uterus and placenta disrupts redox homeostasis, leading to excessive ROS production and oxidative stress in both maternal and embryonic tissues, which may compromise embryonic viability and lead to implantation failure (Grzeszczak et al. Reference Grzeszczak, Łanocha-Arendarczyk and Malinowski2023).

Currently, increasing attention has been directed toward nutritional interventions aimed at improving reproductive performance in animals, particularly litter size. Dietary sodium butyrate (SB) supplementation in pregnant rats enhances embryo implantation efficiency by modulating ovarian P4 synthesis (Ye et al. Reference Ye, Cai and Wang2019, Reference Ye, Zeng and Wang2021b). Additionally, SB treatment can enhance the receptivity of porcine endometrial epithelial cells (Ye et al. Reference Ye, Li and Xu2023). Selenium (Se) is an essential trace nutrient for mammals, and its supplementation before or during pregnancy has been shown to improve blastocyst quality and implantation efficiency (Mamon and Ramos Reference Mamon and Ramos2017). The effects of Se on reproductive performance are associated with its antioxidant properties, as it enhances the activity of antioxidant enzymes, thereby protecting the embryo and placenta from oxidative stress (Gernand et al. Reference Gernand, Schulze and Stewart2016). Furthermore, compared to inorganic Se, organic forms such as selenium yeast (SeY), exhibit lower maternal and embryonic toxicity and reduced the number of stillborn (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Han and Guan2016; Fortier et al. Reference Fortier, Audet and Giguère2012; Quesnel et al. Reference Quesnel, Renaudin and Le Floc’h2008). Soy isoflavones (SIF) phytoestrogens extracted from plants, exhibit structural and functional similarity to E2 (McLaren et al. Reference McLaren, Seidler and Neil2024). They regulate regulatory effects on follicular development and embryogenesis. Makarevich et al. reported that SIF can stimulate the ovary to produce E2, P4 and cAMP, thereby promoting oocyte maturation and pre-implantation embryo development (Makarevich et al. Reference Makarevich, Sirotkin and Taradajnik1997).

Although SB, SeY and SIF are known to enhance reproductive performance, it remains unclear whether supplementation limited to the early implantation window can promote embryo implantation and increase litter size. This study hypothesizes that the combined use of SB–SeY–SIF additives can synergistically improve embryo implantation during early pregnancy. We recorded reproductive performance data of both groups, and measured serum sex hormones and antioxidant biomarkers. In addition, we performed 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing of the fecal microbiota and conducted serum and fecal metabolomic profiling in sows during early pregnancy to comprehensively evaluate the effects of SB–SeY–SIF supplementation.

Materials and methods

Animals and experiment design

The experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University (HZAUSW-2025-0066). A total of 120 healthy, 6–7 parity Landrace × Yorkshire (L × Y) sows, which had not previously been involved in any experiments, were selected from the experimental pig farm. These sows were randomly assigned to two groups: (1) the control group (Ctrl), including 65 sows, fed a basal diet (composition in Table 1); (2) the treatment group (SB–SeY–SIF), including 55 sows, fed the basal diet supplemented with SB–SeY–SIF from pregnancy days 1–28. Sows that were non-pregnant, experienced abortion, or died were excluded. As a result, 56 sows in the control group and 47 sows in the SB–SeY–SIF group successfully farrowed and were included in the final analysis. Randomization was performed based on last parity farrowing records (Table 2) to ensure no statistical differences in farrowing data of the previous parity between groups, thereby minimizing reproductive performance-related bias.

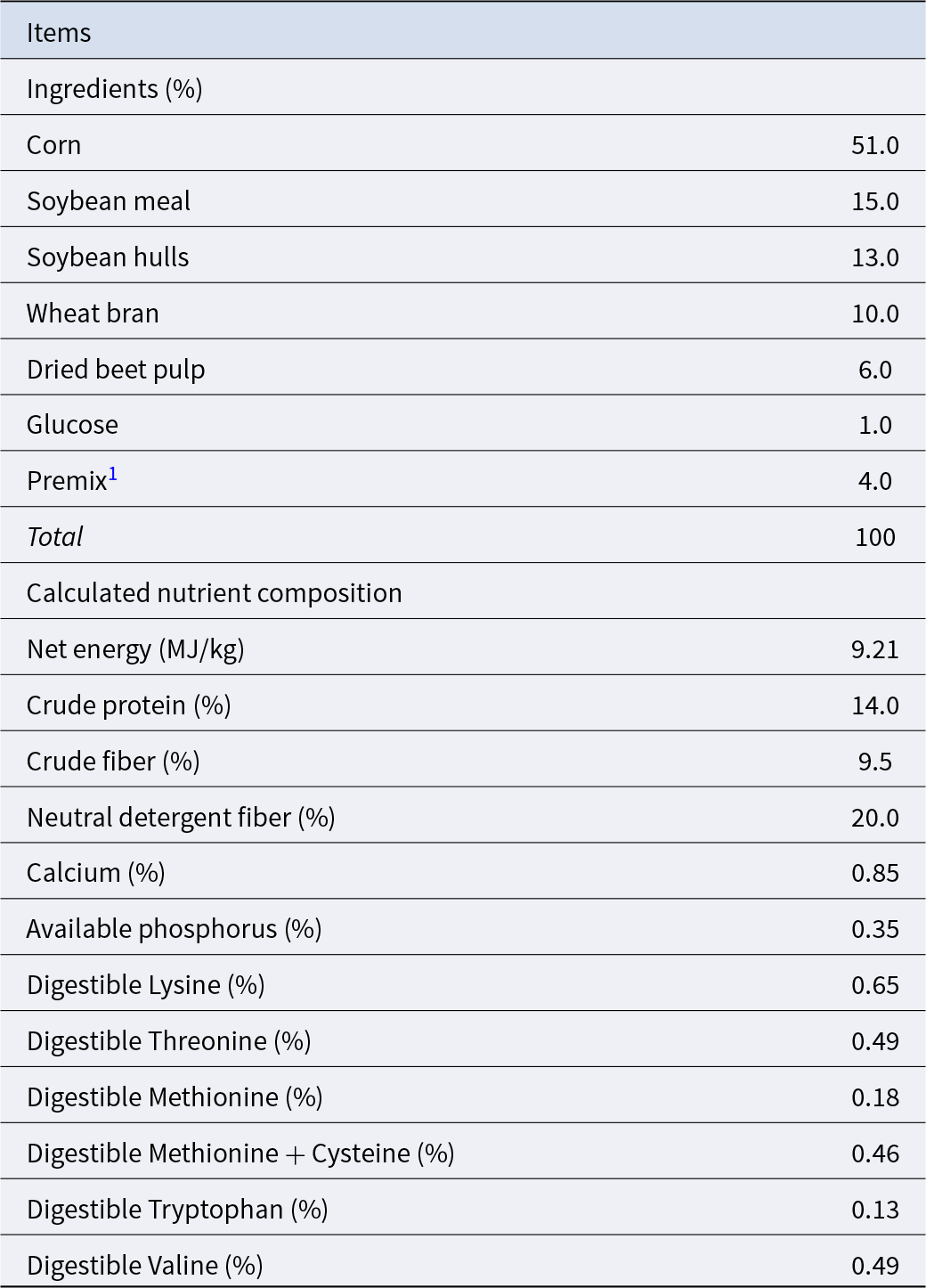

Table 1. Composition and nutrient composition of the basal diet for sows

1 Premix was provided per kilogram of diet: Iron, 220 mg; Copper, 18 mg; Zinc, 120 mg; Manganese, 60 mg; Iodine: 0.4 mg; Selenium: 0.2 mg; Chromium: 0.2 mg; Vitamin A, 11500 IU; Vitamin D3, 3500 IU; Vitamin E, 120 IU; Vitamin B1, 3.4 mg; Vitamin B2, 9.8 mg; Vitamin B6, 5.8 mg; Vitamin B12, 0.034 mg; Niacin, 30 mg; Folic acid, 4.8 mg; D-pantothenic acid, 20 mg.

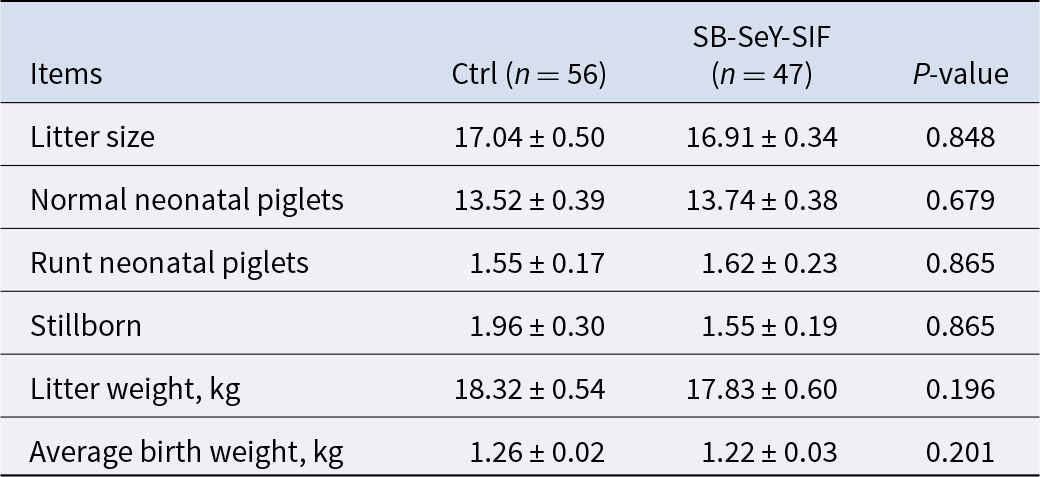

Table 2. Reproductive performance of sows in the previous parity

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Ctrl, control group; SB–SeY–SIF, sodium butyrate–selenium yeast–soy isoflavones treatment group.

The sow trial was conducted at Fusui Pig Farm of Guangxi Jiade Animal Husbandry Co., Ltd. Estrus detection was performed twice daily, and sows exhibiting standing heat were artificially inseminated twice (at 8:30 and 14:30) with the insemination date designated as pregnancy day 0. From pregnancy days 1–28, sows received 2 kg/day of diets, divided into two equal meals at 7:30 and 14:00 daily. From five days before mating until P104, sows were housed individually in gestation pens, and from P104 until weaning, they were moved to farrowing pens. Water was provided ad libitum throughout gestation, and health status was assessed daily. Throughout the entire experiment, both groups were maintained under identical conditions in the same environmentally controlled.

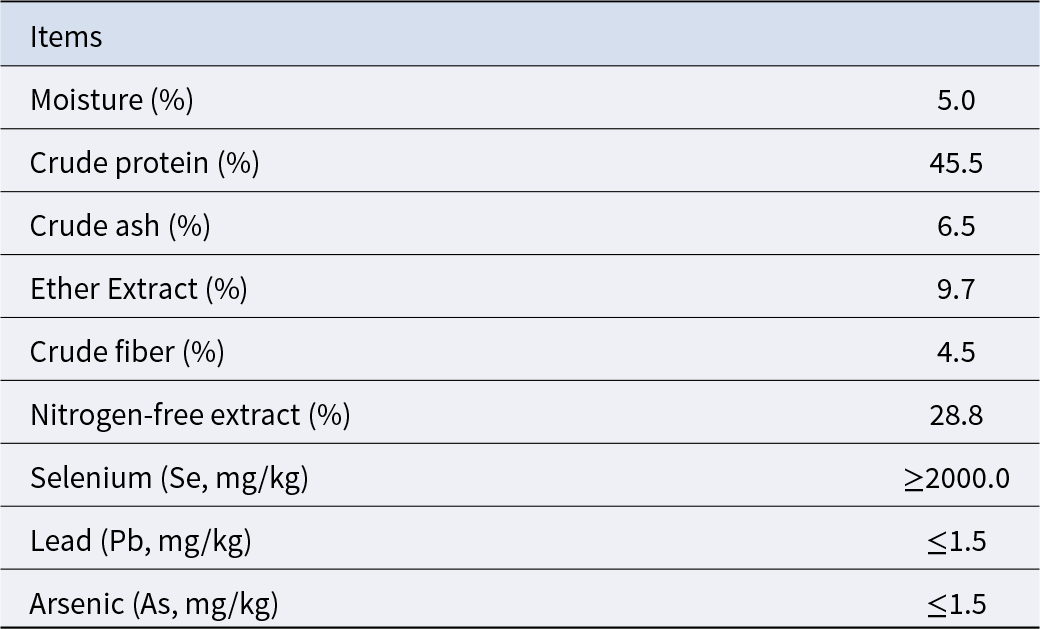

The dosage of SB was determined based on our unpublished studies, in which supplementation with 0.05% SB among several dosages had a better effect on improving reproductive performance. The Se supplementation level was selected according to the existing literature reporting that adding 0.3 ppm Se to a basal diet containing 0.055 ppm Se increased litter size and live litter size (Mahan and Peters Reference Mahan and Peters2004). The pregnancy basal diet used in this study was measured to contain 0.27 ppm Se, and therefore an additional 0.1 ppm Se was supplemented. SeY with a Se content of 0.2% was used as the Se source, resulting in an inclusion of 50 ppm SeY in the diet. High doses of SIF have been shown to adversely affect normal reproductive function, while supplementation at 0.025% does not exert such effects (Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Zhang and Li2012). Therefore, the SIF dosage was set at 0.02% in this study. In summary, the additive supplementation amount in this experiment is 0.05% SB (purity ≥ 99.0%), 50 ppm SeY (composition shown in Table 3) and 0.02% SIF (composition shown in Table 4).

Table 3. Composition of selenium yeast

Table 4. Composition of soy isoflavones

Sample collection and farrowing data recording

Blood and fecal samples were collected at pregnancy day 14 and day 28 (P14 and P28). Fresh fecal samples were collected from the same 35 sows per group at each time point. Blood samples were collected from 16 randomly selected sows per group at each time point. To minimize physiological stress, different sows were used for blood collection at P14 and P28. Blood samples were drawn from the anterior vena cava using sterile disposable needles. After 3-hour clotting at room temperature, serum was separated by centrifugation at 1500 × g for 15 min. All samples underwent immediate flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen followed by long-term storage at −80°C. Samples from sows with failed farrowing or hemolyzed samples were excluded. Ultimately, 30 fecal samples per group per time point were included. For serum samples, 14 samples were collected from the control group at P14 and P28; 14 samples from the SB–SeY–SIF group at P14, and 12 samples at P28, for subsequent detection experiments.

The reproductive performance data were recorded per litter: litter size, normal neonatal piglets (birth weight > 0.7 kg and without malformations), runt neonatal piglets (birth weight < 0.7 kg or with malformations), stillborn, litter weight and average birth weight.

Serum sex hormones assays

Serum E2 and P4 concentrations were determined using Iodine[125I] Estradiol Radioimmunoassay Kit and Progesterone Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay Kit (Beijing North Institute of Biotechnology, Beijing, China). All procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Serum antioxidant biomarkers assays

Serum total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), catalase (CAT) activity, superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity, glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activity, thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) activity and malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations were determined using commercial assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). All procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Serum inflammatory cytokines assays

The concentrations of the inflammatory cytokines in serum, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), were determined using ELISA kits (Elabscience Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Wuhan, China). All procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Fecal bacterial DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene high-throughput sequencing

Total microbial genomic DNA was extracted from fecal samples using the YH-FastPure Stool DNA Isolation Kit (MJYH, Shanghai, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the primers 27 F (5’-AGRGTTYGATYMTGGCTCAG-3’) and 1492 R (5’-RGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3’). PCR conditions were: 95°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s; final extension at 72°C for 10 min. High-fidelity reads were generated from SMRTbell libraries constructed with the PacBio Prep Kit (Pacifc Biosciences, CA, USA) and sequenced on the PacBio Sequel IIe platform (Pacifc Biosciences, CA, USA). Raw reads were quality-filtered using fastp (v0.19.6) and merged using FLASH (v1.2.11). Denoising was performed in QIIME2 to generate operational taxonomic units (OTUs). Sequences classified as chloroplasts or mitochondria were removed. Rarefaction was applied to 20,000 reads per sample, with average Good’s coverage reaching 99.09%. Taxonomic assignment was conducted using a Naive Bayes classifier against the SILVA 16S rRNA database (v138).

Alpha diversity was calculated using Mothur (v1.30.1). Beta diversity was assessed using the principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) (Bray–Curtis distance) and tested for significance using PERMANOVA (Vegan v2.5). The linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) identified differentially abundant bacterial taxa (LDA > 2, P < 0.05). Spearman correlation heatmap analysis was performed with |r| > 0.6 and P < 0.05 as significance thresholds.

Serum and fecal untargeted metabolomics analysis

For sample preparation, 100 μL of serum was mixed with 400 μL of extraction solution (acetonitrile:methanol = 1:1) containing 0.02 mg/mL of the internal standard (L-2-chlorophenylalanine). The mixture was vortexed for 30 s and then subjected to low-temperature ultrasonic extraction at 5℃ and 40 kHz for 30 min, followed by incubation at − 20℃ for 30 min. After centrifugation at 13,000 × g and 4℃ for 15 min, the supernatant was collected and dried under nitrogen gas. The residue was reconstituted in 100 μL of reconstitution solution (acetonitrile:water = 1:1) with low-temperature ultrasonic extraction at 5℃ and 40 kHz for 5 min, and finally centrifuged again at 13,000 × g and 4℃ for 10 min.

Approximately 50 mg of fecal sample was mixed with 400 μL of extraction solvent (methanol:water = 4:1, v/v) containing an internal standard (L-2-chlorophenylalanine, 0.02 mg/mL). Metabolites were extracted using a refrigerated tissue homogenizer for 6 min (−10°C, 50 Hz), followed by low-temperature ultrasonic extraction for 30 min (5°C, 40 kHz). The mixture was then incubated at −20°C for 30 min and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C.

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed using a Thermo UHPLC-Q Exactive HF-X system equipped with an ACQUITY HSS T3 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm; Waters, USA) at Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. Mass spectrometry was conducted in both positive and negative electrospray ionization modes. Raw data were processed using Progenesis QI software for peak detection, alignment, retention time correction, and integration. Metabolite identification was conducted by matching against the HMDB, Metlin, and Majorbio Database. The resulting data matrix included sample names, m/z values, retention times, and peak intensities. Data preprocessing involved filtering out features present in less than 80% of samples, imputing missing values with the minimum detected value, and normalizing to the total ion intensity per sample. Quality control features with a relative standard deviation > 30% were excluded.

The preprocessed data matrix was subjected to principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) using the R package “ropls” (v1.6.2). Model stability was evaluated by 7-fold cross-validation. Significant differential metabolites were identified based on variable importance in projection (VIP) scores from the OPLS-DA model and false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P-values (VIP > 1, P < 0.05). These metabolites were annotated against the KEGG database to identify associated pathways. Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the Python package “scipy.stats.”

Statistical analysis

All data were assessed for normality. Normally distributed data were analyzed using Student’s t-test, while non-normally distributed data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, while P-values between 0.05 and 0.100 were interpreted as indicating a tendency. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (v30) and GraphPad Prism (v10) software.

Results

Effects of dietary supplementation with SB–Sey-SIF on reproductive performance in sows

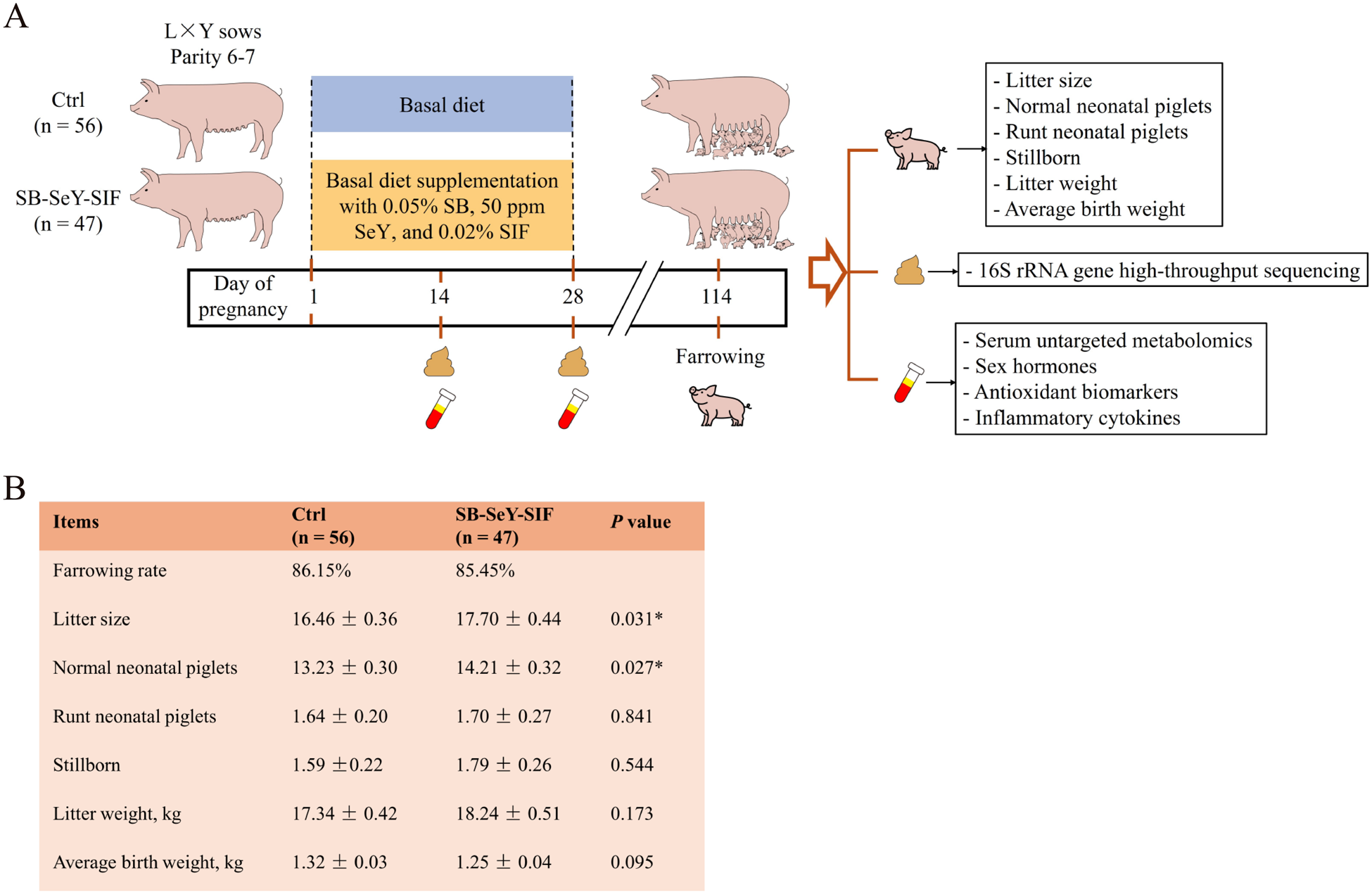

Figure 1A showed the trial flowchart for sows. The farrowing rate of the SB–SeY–SIF group was 85.45%, while that of the control group was 86.15%. The two groups exhibited comparable farrowing rates, indicating that dietary supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF does not adversely affect the farrowing rate of sows. Dietary supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF significantly increased litter size (17.70 vs. 16.46) and the number of normal neonatal piglets (14.21 vs. 13.23) compared with the control group (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences between the two groups in the number of runt neonatal piglets, stillborn, or litter weight. However, compared to the control group, there was a trend toward reduced average birth weight (1.25 kg vs. 1.32 kg) in the SB–SeY–SIF group (P = 0.095) (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that dietary supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF during early pregnancy can increase litter size and normal neonatal piglet numbers in sows.

Figure 1. (A) Schematic of the sow trial design. (B) Table of sow reproductive performance data. (C) Rarefaction curves of observed species based on 16S rRNA gene high-throughput sequencing. (B) Ctrl, n = 56; SB–SeY–SIF, n = 47. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Ctrl, control group; SB–SeY–SIF, sodium butyrate-selenium yeast-soy isoflavones treatment group; P14, pregnancy day 14; P28, pregnancy day 28.

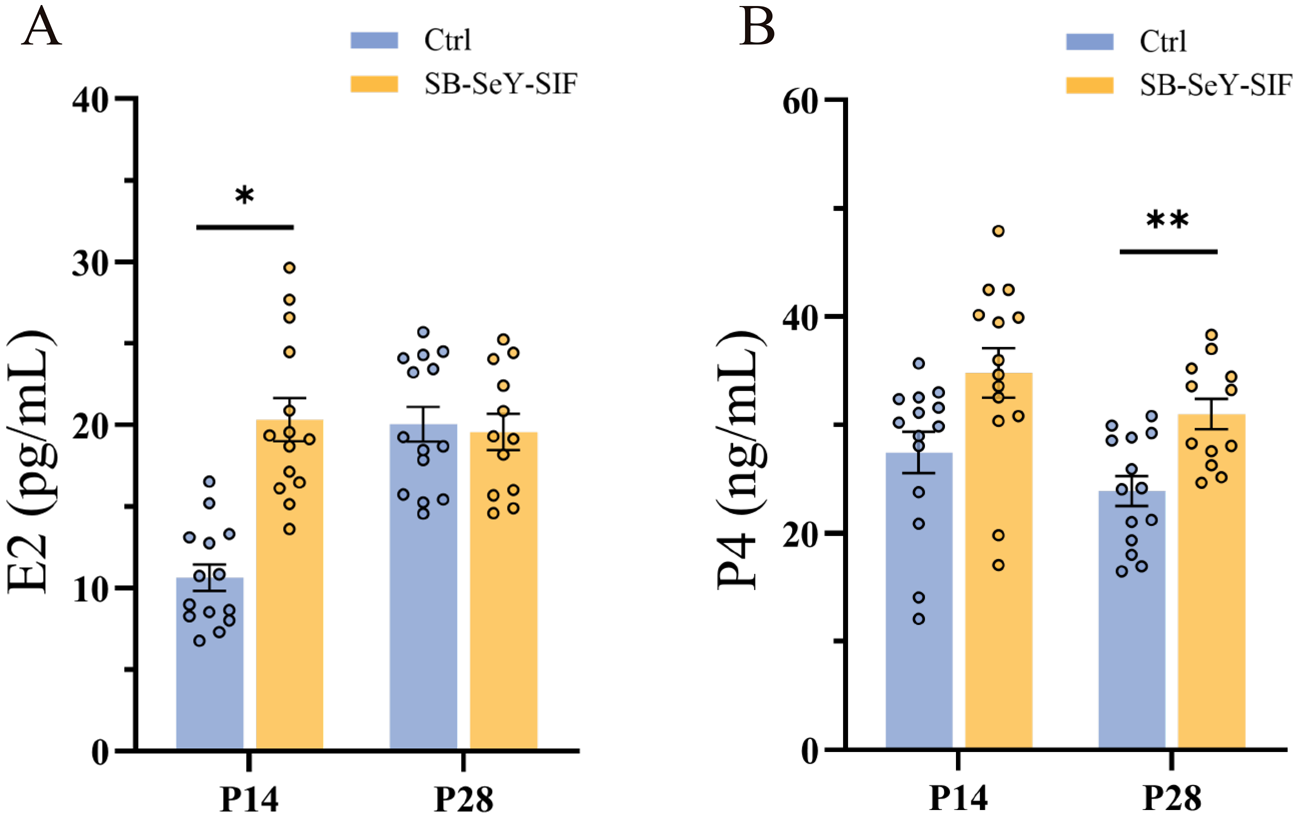

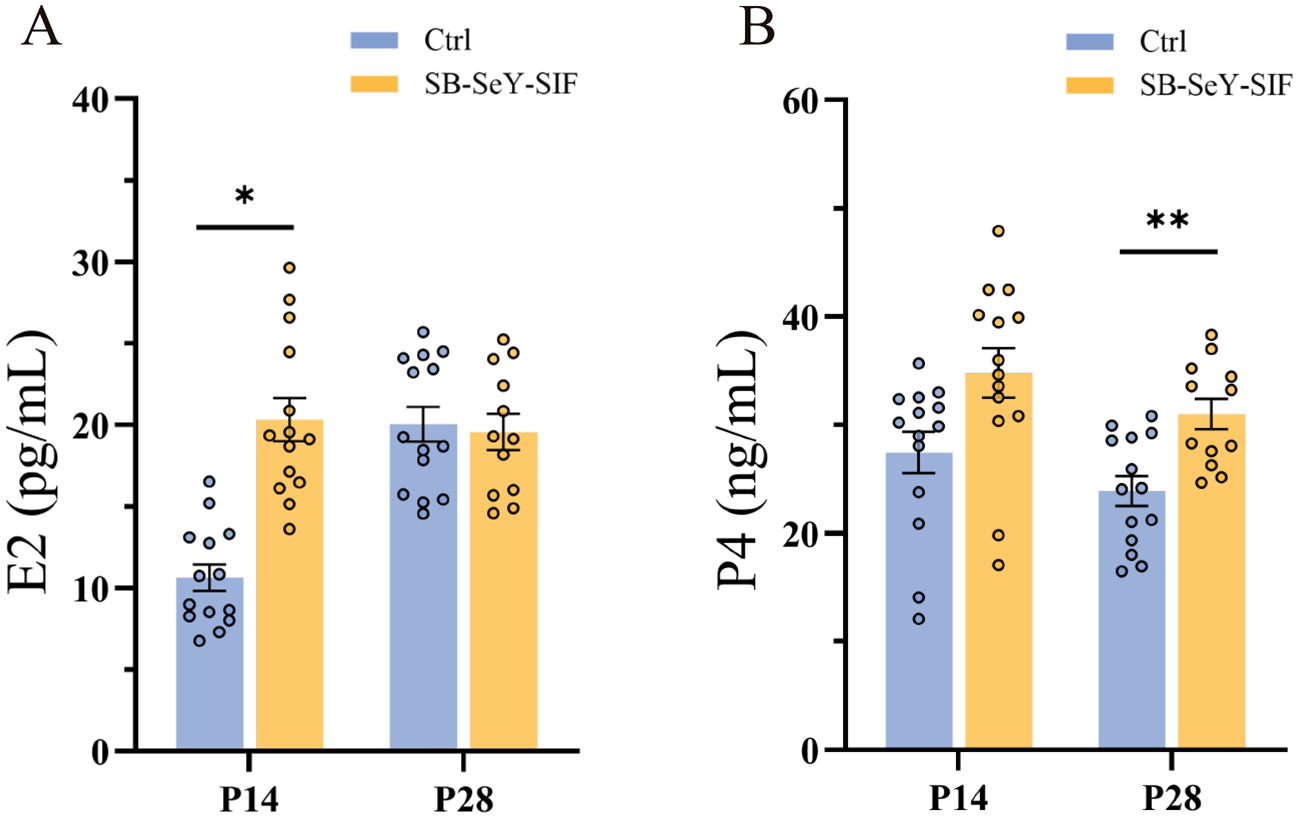

Effects of dietary supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF on sex hormones in sows

As key steroid hormones synthesized by the ovary, E2 and P4 play key roles in promoting embryo implantation and development during early pregnancy. We determined the E2 and P4 concentrations in serum. Dietary supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF significantly increased E2 concentrations at P14 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). Although P4 levels did not differ significantly at P14, they were significantly higher than those in the control group at P28 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that dietary SB–SeY–SIF supplementation can improve the synthesis of E2 and P4 during early pregnancy.

Figure 2. (A–B) Serum E2 (A) and P4 (B) concentrations in sows at P14 and P28. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; Ctrl P14, n = 14; SB–SeY–SIF P14, n = 14; Ctrl P28, n = 14; SB–SeY–SIF P28, n = 12. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. E2, estradiol; P4, progesterone; Ctrl, control group; SB–SeY–SIF, sodium butyrate–selenium yeast–soy isoflavones treatment group; P14, pregnancy day 14; P28, pregnancy day 28.

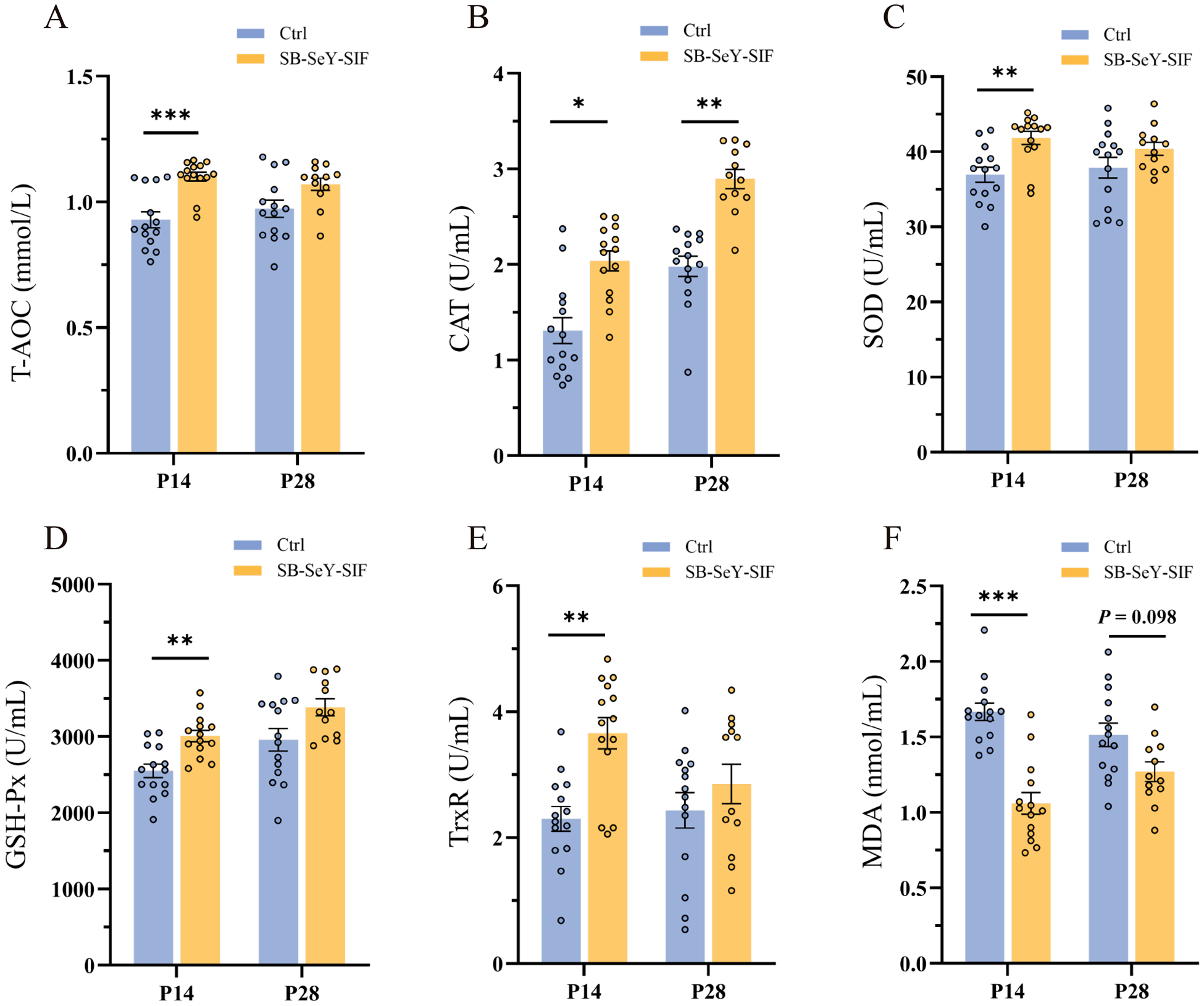

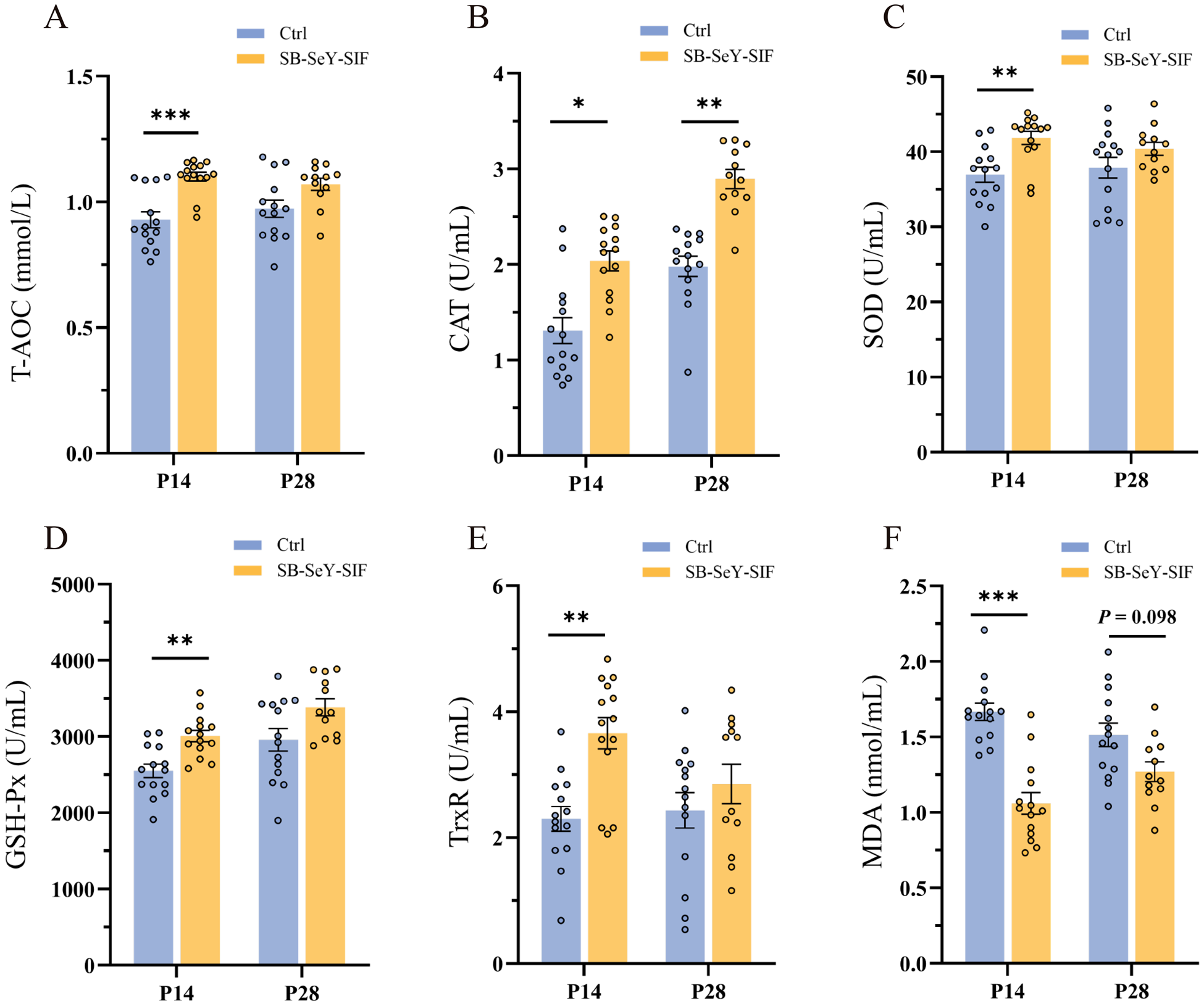

Effects of dietary supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF on antioxidant capacity in sows

Since SeY is known to enhance antioxidant capacity, we further evaluated whether SB–SeY–SIF supplementation improved the maternal antioxidant status during early pregnancy by measuring serum antioxidant biomarkers. Dietary supplementation with SB-SeY-SIF significantly increased T-AOC (P < 0.001), SOD activity (P < 0.01), GSH-Px activity (P < 0.01), and TrxR activity (P < 0.01) at P14, while significantly decreasing serum oxidative stress biomarker MDA levels (P < 0.001). Additionally, CAT activity was significantly elevated at both P14 (P < 0.05) and P28 (P < 0.01), with a trend toward reduced MDA levels at P28 (P = 0.098) (Fig. 3A-F). These findings imply that dietary supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF can alleviate oxidative stress and enhance antioxidant capacity during early pregnancy in sows.

Figure 3. (A–F) Serum T-AOC (A), CAT activity (B), SOD activity (C), GSH-Px activity (D), TrxR activity (E) and MDA concentrations (F) in sows at P14 and P28. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; Ctrl P14, n = 14; SB-SeY-SIF P14, n = 14; Ctrl P28, n = 14; SB–SeY–SIF P28, n = 12. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. T-AOC, total antioxidant capacity; CAT, catalase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase; TrxR, thioredoxin reductase; MDA, malondialdehyde; Ctrl, control group; SB–SeY–SIF, sodium butyrate–selenium yeast–soy isoflavones treatment group; P14, pregnancy day 14; P28, pregnancy day 28.

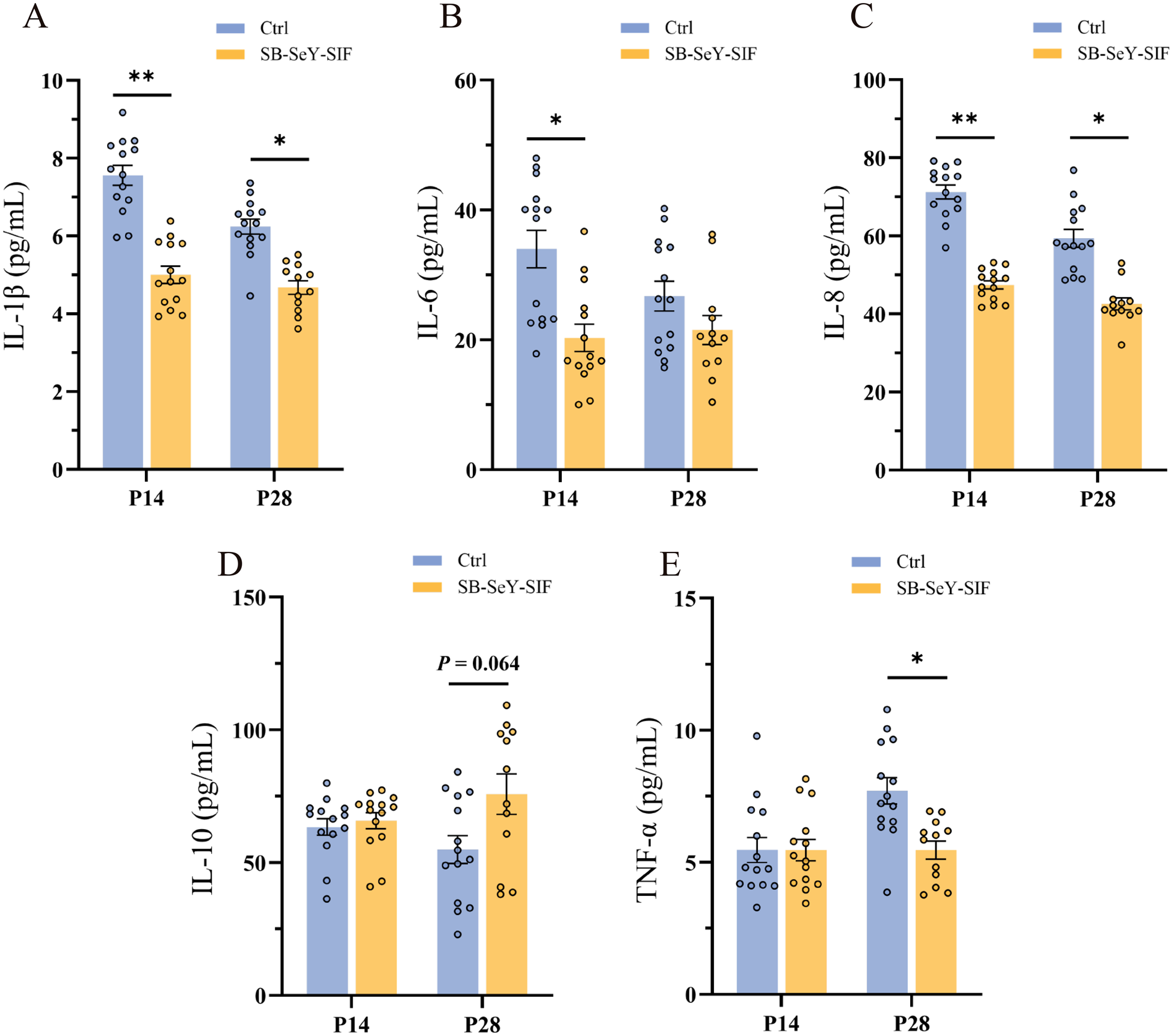

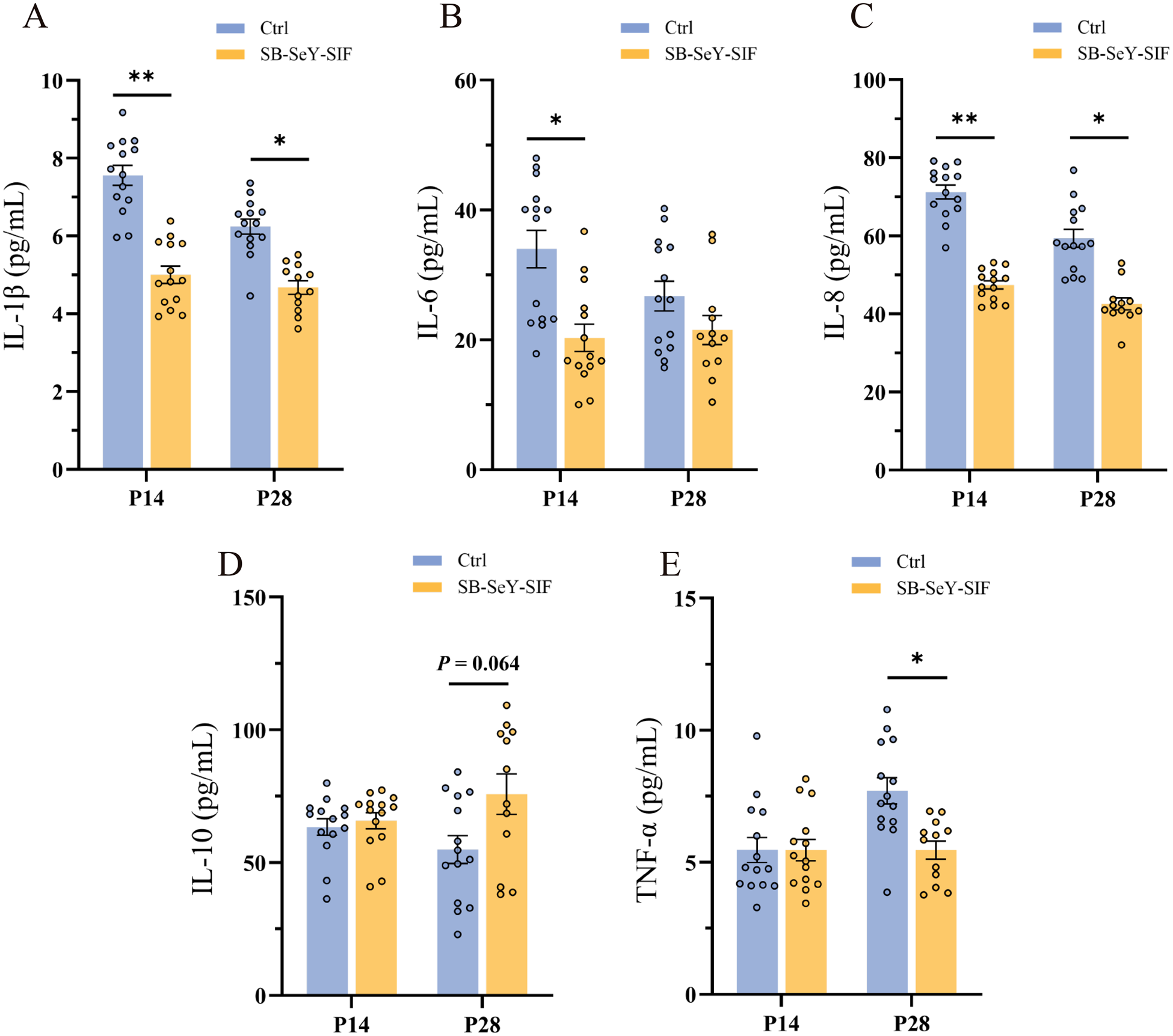

Effects of dietary supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF on inflammatory response in sows

Oxidative stress is typically accompanied by elevated inflammation, as excessive production of ROS and other oxidative stress biomarkers can activate pro-inflammation signaling pathways. To further investigate the antioxidant effects of SB–SeY–SIF during early pregnancy, we measured the serum levels of inflammatory cytokines.

Compared to the control group, the SB–SeY–SIF group showed significantly lower serum concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines at P14, including IL-1β (P < 0.01), IL-6 (P < 0.05) and IL-8 (P < 0.01). At P28, SB–SeY–SIF supplementation significantly decreased levels of IL-1β (P < 0.05), IL-8 (P < 0.05) and TNF-α (P < 0.05), while there was a trend toward increased concentrations of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (P = 0.064) (Fig. 4A-E). These findings demonstrate that SB–SeY–SIF supplementation can alleviate inflammation levels during early pregnancy.

Figure 4. (A–E) Serum concentrations of IL-1β (A), IL-6 (B), IL-8 (C), IL-10 (D) and TNF-α (E) in sows at P14 and P28. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; Ctrl P14, n = 14; SB–SeY–SIF P14, n = 14; Ctrl P28, n = 14; SB-SeY-SIF P28, n = 12. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. IL-1β, interleukin 1β; IL-6, interleukin 6; IL-8, interleukin 8; IL-10, interleukin 10; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α; Ctrl, control group; SB–SeY–SIF, sodium butyrate–selenium yeast–soy isoflavones treatment group; P14, pregnancy day 14; P28, pregnancy day 28.

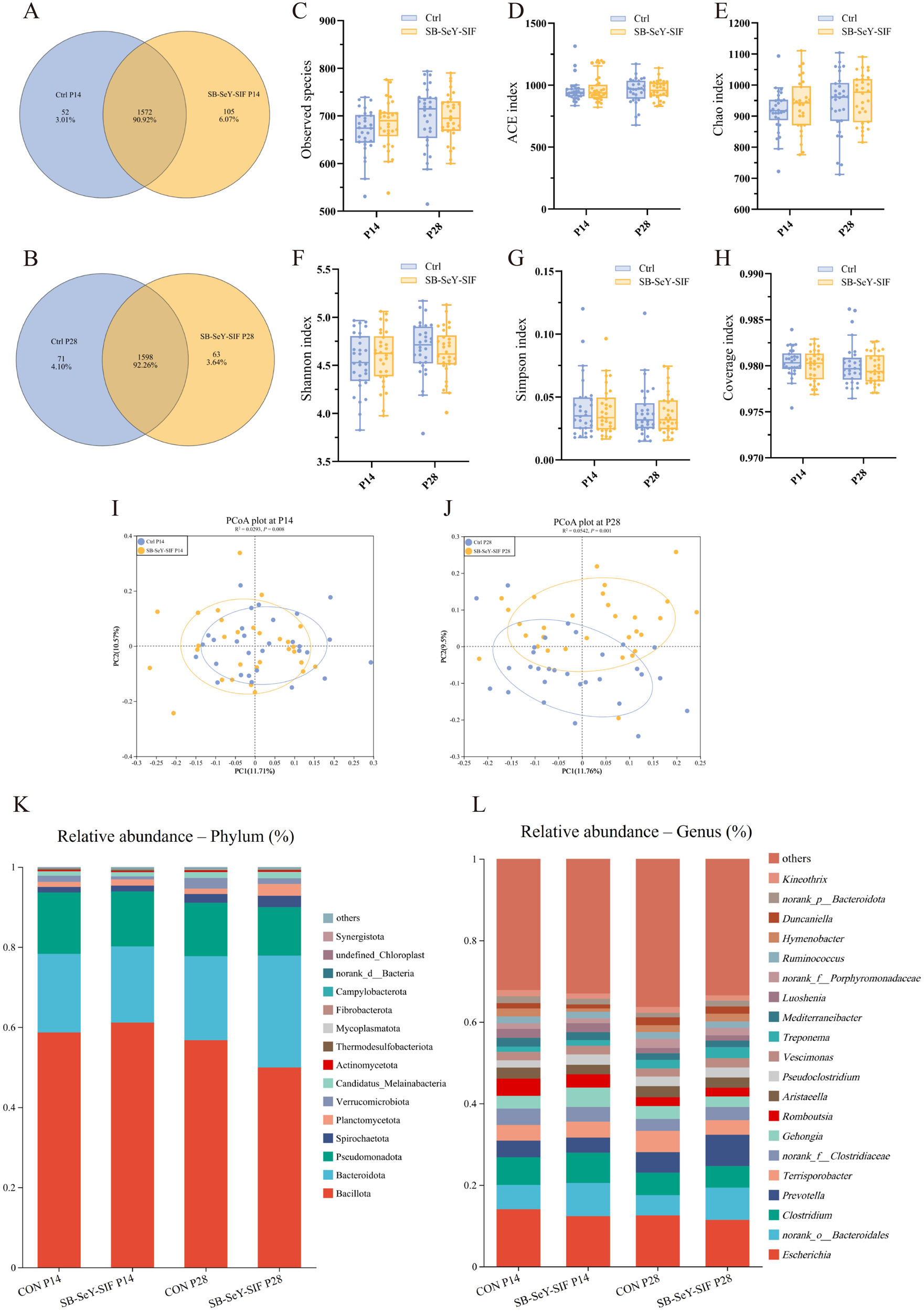

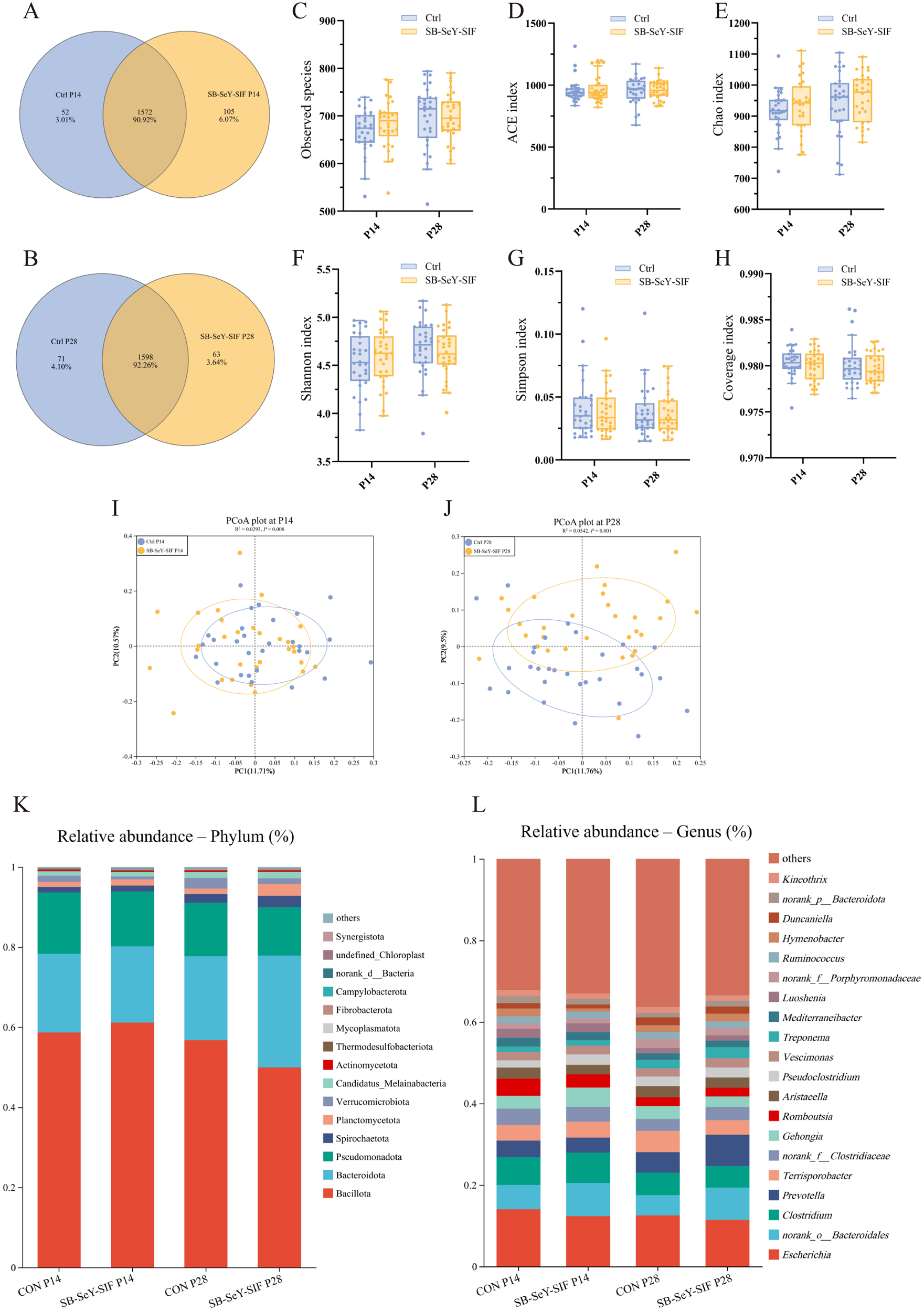

Effects of dietary supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF on fecal microbial composition in sows

In addition to participating in nutrient digestion and absorption, the gut microbiota also plays a regulatory role in the host reproductive system. In sows, gut microbial composition influences reproductive performance. Therefore, to comprehensively evaluate the effects of dietary SB–SeY–SIF supplementation, we performed 16S rRNA gene high-throughput sequencing on fecal samples collected at P14 and P28. The Venn diagram showed that a total of 1729 OTUs were identified at P14, among which 52 were unique to the control group, while 105 were unique to the SB–SeY–SIF group. At P28, a total of 1732 OTUs were identified, among which 71 were unique to the control group and 63 were unique to the SB–SeY–SIF group (Fig. 5A-B). Compared with the control group, the SB–SeY–SIF group did not significantly alter any α-diversity indexes at P14 and P28 (Fig. 5C-H). PCoA plots showed significant differences in fecal microbial community composition between the control and SB–SeY–SIF groups at both P14 and P28 (Fig. 5I-J). Bar plots of taxonomic composition were shown the relative abundance of gut microbiota at both phylum and genus levels. The dominant bacterial taxa at both the phylum (Fig. 5K) and genus (Fig. 5L) levels were similar between the two groups after SB––SIF supplementation.

Figure 5. (A–B) Venn diagrams of fecal microbiota OTUs in sows at P14 (A) and P28 (B). (C–H) Alpha diversity indexes of the fecal microbiome during early pregnancy, including observed species (C), ACE (D), Chao (E), Shannon (F), Simpson (G), and Coverage (H) indexes. (I–J) PCoA plots of fecal microbiome at P14 (I) and P28 (J). (K–L) Bar plots of taxonomic composition of fecal microbiome at phylum (K) and genus (L) levels. Bar plots showing the relative abundance of the top 15 bacterial phyla and the top 20 bacterial genera. N = 30. PCoA, principal coordinates analysis; Ctrl, control group; SB–SeY–SIF, sodium butyrate–selenium yeast–soy isoflavones treatment group; P14, pregnancy day 14; P28, pregnancy day 28.

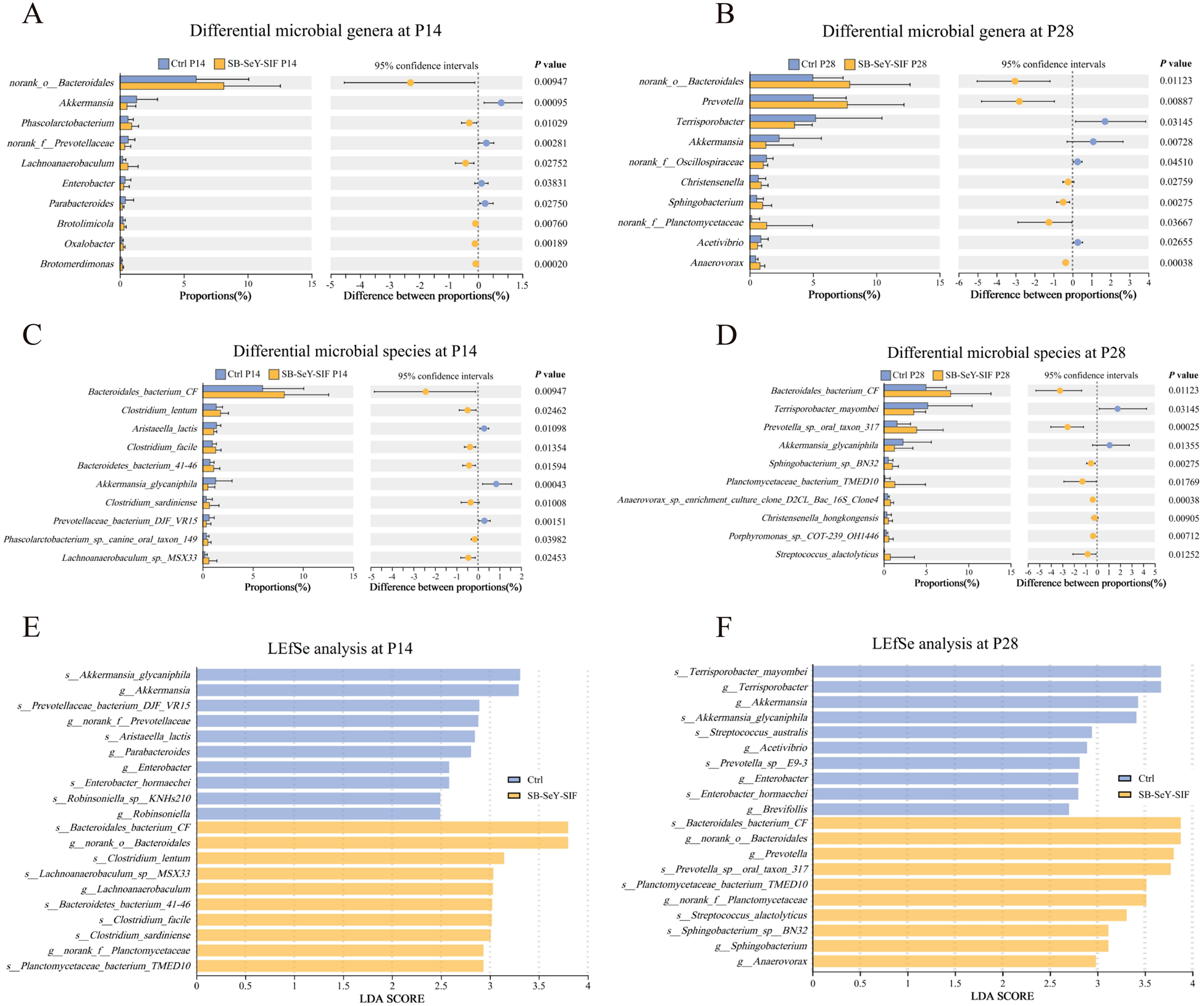

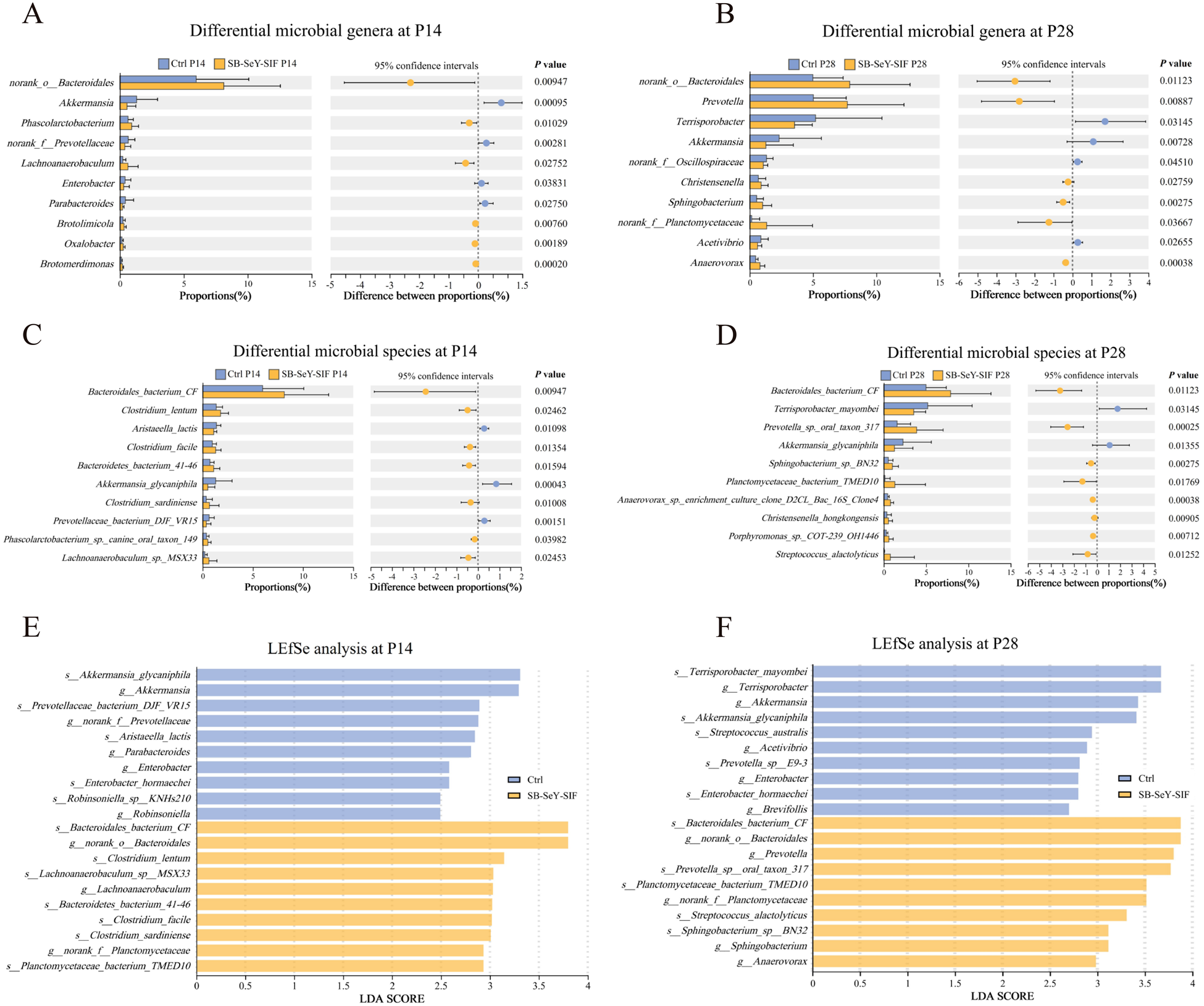

We further analyzed the differential microbial taxa between the two groups. Figure 6A-D showed the top 10 genera (Fig. 6A-B) and species (Fig. 6C-D) with the highest relative abundance that differed significantly between groups at P14 and P28, respectively. In addition, LEfSe analyses were performed to identify key microbial taxa. Following SB–SeY–SIF supplementation, at P14, the key microbial taxa enriched in the SB–SeY–SIF group at the genus level included norank_o_Bacteroidales, Lachnoanaerobaculum, norank_f_Planctomycetaceae, while at the species level, they included Bacteroidales bacterium CF, Clostridium lentum, Lachnoanaerobaculum sp. MSX33, Bacteroidetes bacterium 41-46, Clostridium facile, Clostridium sardiniense, and Planctomycetaceae bacterium TMED10 (Fig. 6E). At P28, the SB–SeY–SIF group was characterized by enrichment of norank_o_Bacteroidales, Prevotella, norank_f_Planctomycetaceae, Sphingobacterium, and Anaerovorax at the genus level, and by Bacteroidales bacterium CF, Prevotella sp. oral taxon 317, Planctomycetaceae bacterium TMED10, Streptococcus alactolyticus, and Sphingobacterium sp. BN32 at the species level (Fig. 6F). These findings suggest that dietary supplementation with SB-SeY-SIF can modulate the composition of gut microbiota during early pregnancy in sows.

Figure 6. (A–B) The top 10 most abundant differential microbial genera at P14 (A) and P28 (B). (C–D) The top 10 most abundant differential microbial species at P14 (C) and P28 (D). (E–F) The top 10 key differential microbial genera and species were identified based on LDA score ranking between groups at P14 (E) and P28 (F). (A–D) Significance was tested using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. (E-F) Taxa with P < 0.05 and LDA score ≥ 2.0 were considered discriminative features. N = 30. LEfSe, linear discriminant analysis coupled with effect size; Ctrl, control group; SB–SeY–SIF, sodium butyrate–selenium yeast–soy isoflavones treatment group; P14, pregnancy day 14; P28, pregnancy day 28.

Effects of dietary supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF on serum and fecal metabolic profiles in sows

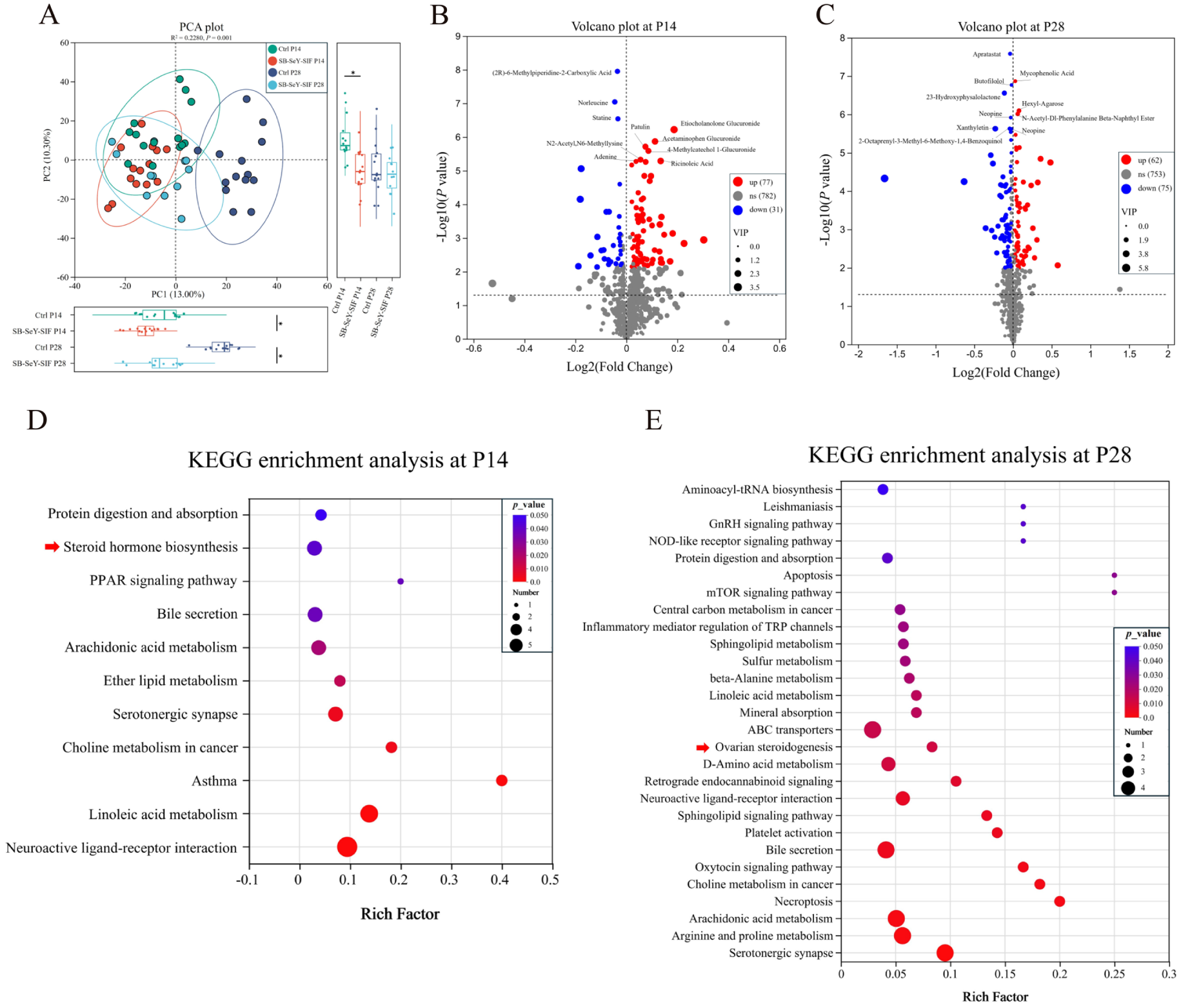

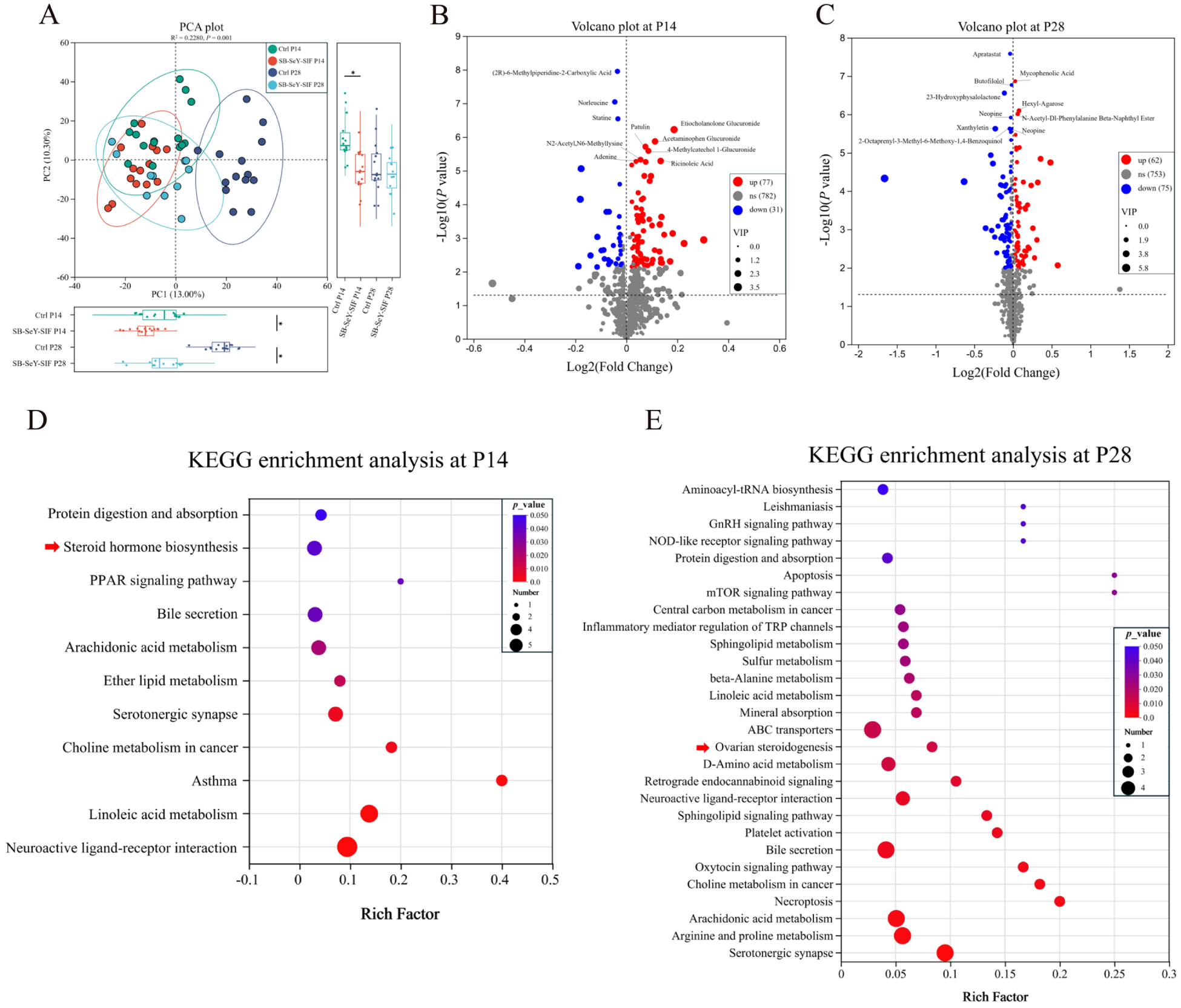

We employed untargeted metabolomics to investigate the differences in metabolites and metabolic pathways in serum. PCA plot revealed significant differences in serum metabolic profiles between the control and SB–SeY–SIF groups at P14 and P28 (Fig. 7A). A total of 616 metabolites were detected and annotated in serum samples. With SB–SeY–SIF supplementation, compared with the control group, 77 serum metabolites were significantly increased and 31 were decreased in the SB–SeY–SIF group at P14. At P28, 62 serum metabolites were upregulated, while 75 were downregulated in the SB–SeY–SIF group compared to the control group (Fig. 7B-C). We further performed KEGG pathway enrichment analysis to identify the main metabolic pathways associated with the differential metabolites. At P14, the differential metabolites between the control and SB–SeY–SIF groups were significantly enriched in neuroactive ligand–receptor interaction, linoleic acid metabolism, asthma, choline metabolism in cancer, steroid hormone biosynthesis, among others. Additionally, at P28, the significantly enriched pathways included serotonergic synapse, arginine and proline metabolism, arachidonic acid metabolism, necroptosis, ovarian steroidogenesis, among others (Fig. 7D-E).

Figure 7. (A) PCA plot of serum metabolome. (B–C) Volcano plots of serum metabolome at P14 (B) and P28 (C). (D–E) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis for the different metabolites in serum at P14 (D) and P28 (E). (B–C) The top 10 metabolites with the smallest P-value are labeled. Differential metabolites were defined as those with P < 0.05, VIP (from OPLS-DA) > 1, and |FC| > 1. Ctrl P14, n = 14; SB–SeY–SIF P14, n = 14; Ctrl P28, n = 14; SB–SeY–SIF P28, n = 12. PCA, principal component analysis; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; Ctrl, control group; SB–SeY–SIF, sodium butyrate–selenium yeast–soy isoflavones treatment group; P14, pregnancy day 14; P28, pregnancy day 28.

In addition, secondary metabolites produced by gut microbiota are also involved in regulating sow reproductive performance. Therefore, we analyzed the fecal metabolic profiles during early pregnancy to further explore the effects of SB–SeY–SIF supplementation. Supplementary Fig. 1 showed the KEGG-enriched pathways of differential fecal metabolites between the two groups at P14 and P28 (Supplementary Fig. 1A-B). The results show that differential metabolites at both time points were commonly enriched in several pathways, including tryptophan metabolism, neuroactive ligand–receptor interaction, fatty acid biosynthesis, penicillins, cAMP signaling pathway, tropane, piperidine and pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, tyrosine metabolism, and biosynthesis of plant secondary metabolites. These results indicate that SB–SeY–SIF supplementation can alter the serum metabolic profile and the secondary metabolic processes of the gut microbiota during early pregnancy.

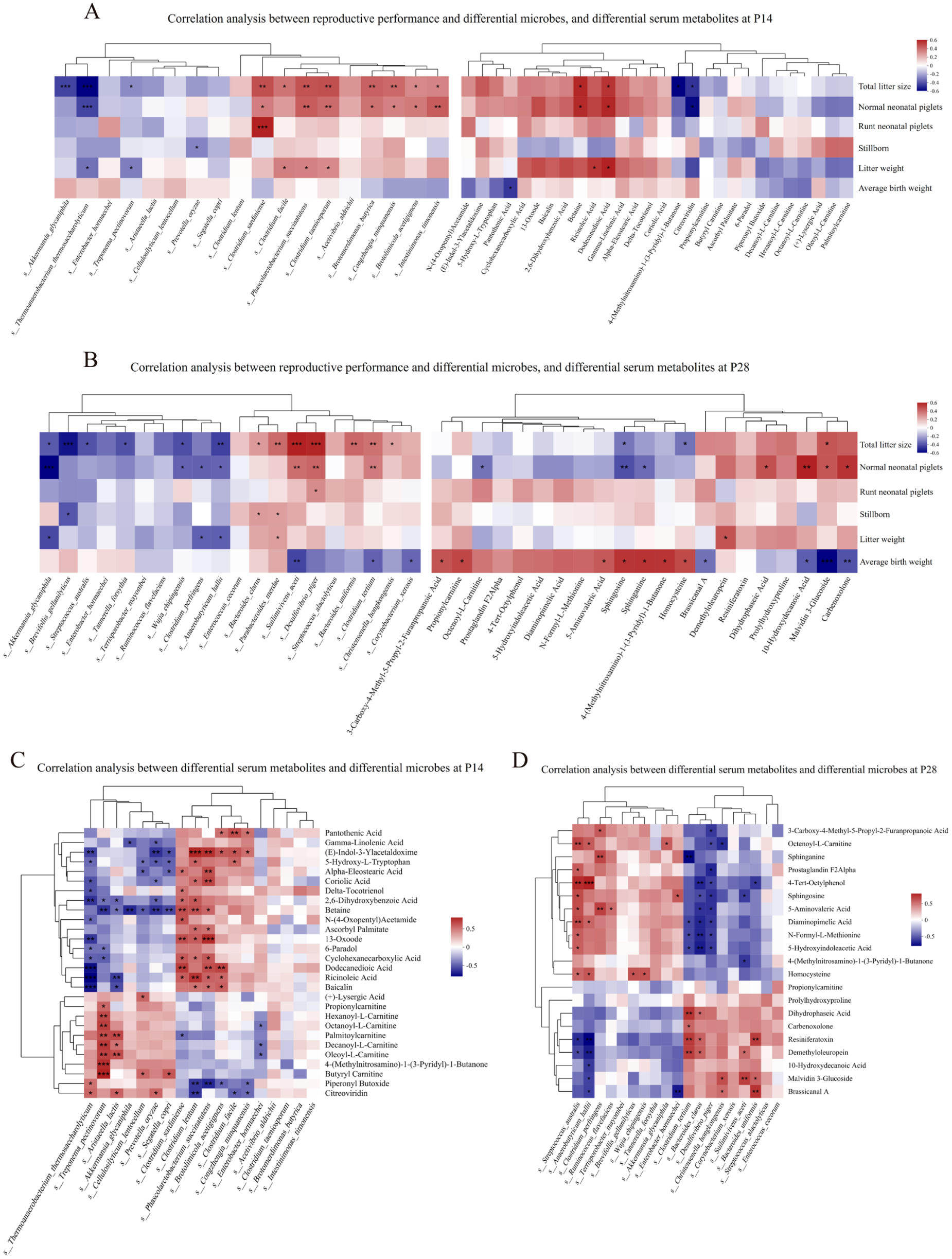

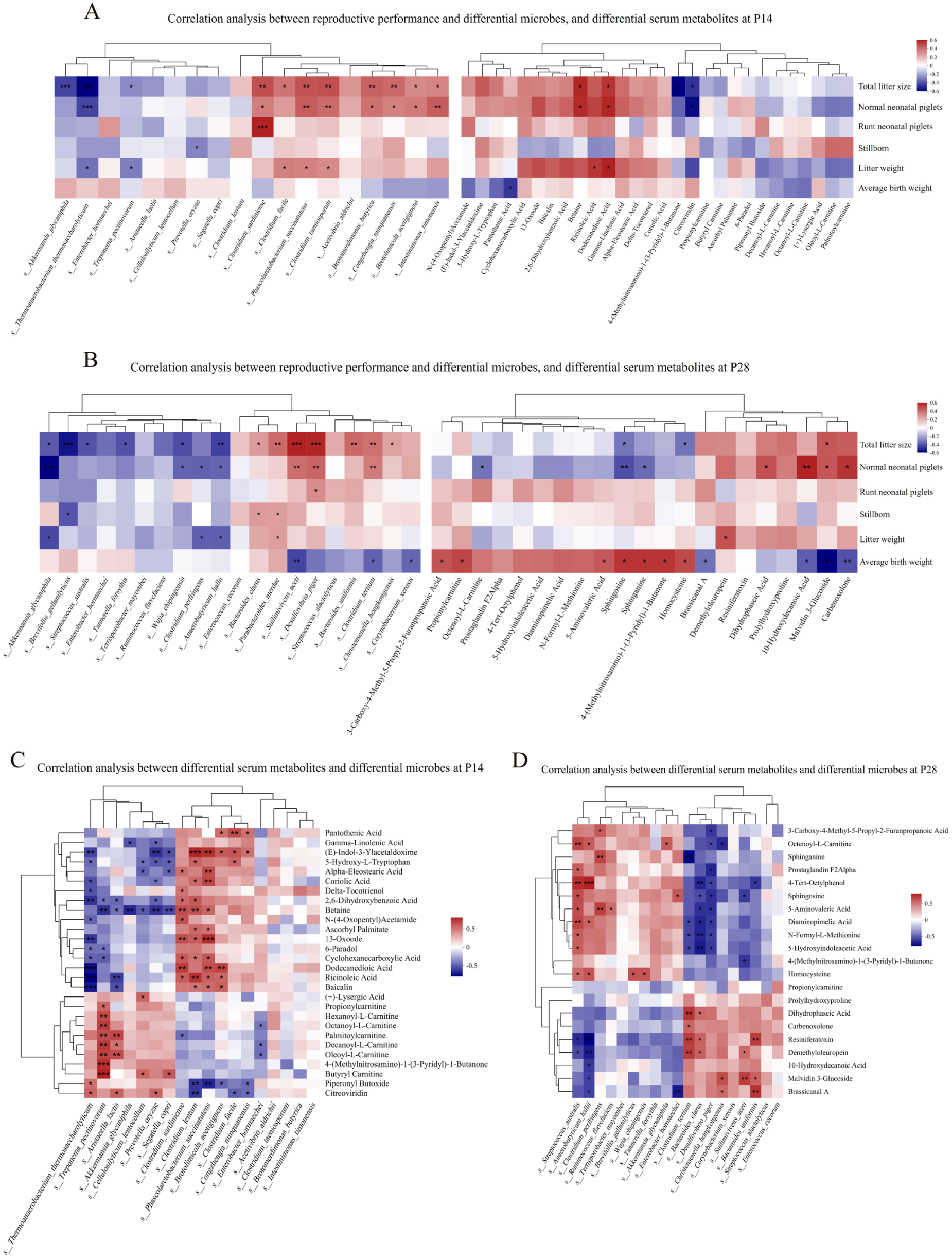

Correlation analysis between reproductive performance, fecal microbiota, and serum and fecal metabolites

We performed Spearman correlation analyses between sow reproductive performance, differential fecal microbiota taxa with high LDA scores identified by LEfSe analysis, as well as differential serum metabolites with high VIP values. At P14, seven microbial taxa, including C. sardiniense, Clostridium taeniosporum, Phascolarctobacterium succinatutens, Brotomerdimonas butyrica, Congzhengia minquanensis, Brotolimicola acetigignens and Intestinimonas timonensis, showed significant positive correlations with both litter size and normal neonatal piglet numbers. Among the serum metabolites, betaine and dodecanedioic acid (DDDA) were positively correlated with both litter size and normal neonatal piglet numbers, whereas Akkermansia giganiphila, Treponema pectinovorum and Thermoanaerobacter thermosaccharolyticum and metabolites 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and citreoviridin were negatively correlated with litter size (Fig. 8A). At P28, 3 microbial taxa, including Suilimivivens aceti, Desulfovibrio piger, and Clostridium tertium, as well as the serum metabolite malvidin 3-glucoside (mv-3-glc) showed significant positive correlations with both litter size and normal neonatal piglet numbers, while A. glycaniphila, S. australis, Brevifollis gellanilyticus, Wujia chipingensis, Tannerella forsythia, Anaerobutyricum hallii and metabolites sphingosine and homocysteine were negatively correlated with the litter size (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8. (A–B) Heatmap of Spearman correlation between sow reproductive performance and differential fecal microbial species with high LDA scores (left) and differential serum metabolites with high VIP values (right) at P14 (A) and P28 (B). (C–D) Heatmap of Spearman correlation between differential microbial species and differential serum metabolites at P14 (C) and P28 (D). Colors indicate the strength and direction of the correlations: red denotes positive correlations, while blue denotes negative correlations. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. Ctrl, control group; SB–SeY–SIF, sodium butyrate–selenium yeast–soy isoflavones treatment group; P14, pregnancy day 14; P28, pregnancy day 28.

We further performed correlation analyses between fecal metabolites enriched in KEGG pathways and sow reproductive performance. At P14, Prostaglandin I2 (PGI₂), caprylic acid, kynurenic acid, 5α-campestan-3-one, ecgonine methyl ester, 5β-cholestane-3α,7α,12α,23 R,25-pentol, estriol and L-DOPA were positively correlated with both litter size and the number of normal neonatal piglets. At P28, octopine, 5-methoxytryptamine, PGI₂, caprylic acid, 6-keto-Prostaglandin F1α, lotaustralin and β-tyrosine showed positive correlations with litter size and the number of normal neonatal piglets (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Further correlation analyses between these microbial taxa and metabolites were performed. Among the taxa and metabolites that were positively correlated with both litter size and the number of normal neonatal piglets, at P14, C. sardiniense and P. succinatutens were positively correlated with betaine and DDDA, whereas at P28, S. aceti was positively correlated with mv-3-glc (Fig. 8CߝD). In addition, Supplementary Fig. 3 presents the correlation patterns between early-pregnancy differential gut microbes and differential fecal metabolites.

Discussion

Most nutritional strategies to improve sow reproductive performance target the entire pregnancy period. In this study, we demonstrated that dietary supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF limited to pregnancy days 1–28 increased litter size and the number of normal neonatal piglets, indicating that early pregnancy SB–SeY–SIF supplementation has considerable potential for practical application in sow nutrition and production. However, a downward trend in average birth weight was observed. Birth weight is a critical parameter in commercial piglets, as it is closely associated with postnatal growth performance. High embryo implantation rates may lead to uterine crowding, which in turn imposes nutritional restriction on fetal development and results in reduced birth weights (Foxcroft et al. Reference Foxcroft, Dixon and Novak2006). Although only a decreasing trend in piglet birth weight was observed in this study, it will be important in future research to determine whether this trend influences subsequent growth performance, such as weaning weight and feed conversion efficiency. Moreover, to address the production challenge of increased litter size accompanied by reduced birth weight, nutritional strategies for sows with high embryo implantation rates should be further optimized to ensure adequate nutrient supply for fetal development.

Given the crucial roles of E2 and P4 in supporting embryo implantation during early pregnancy, we measured their concentrations in serum. Consistent with the KEGG-based predictions, dietary supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF significantly increased E2 and P4 concentrations, suggesting that SB–SeY–SIF may maintain embryo implantation and increases litter size by promoting sex hormones synthesis in early pregnancy. Subsequently, we found that supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF significantly increased serum total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) and the activities of antioxidant enzymes, while reducing the levels of the oxidative stress marker malondialdehyde (MDA). Correspondingly, systemic inflammation was also alleviated. Oxidative imbalance during embryo implantation can compromise embryo viability and contribute to implantation failure (Wisdom et al. Reference Wisdom, Wilson and McKillop1991). Morphological and immunohistochemical studies have shown that placental tissues from early spontaneous abortion exhibit significantly increased oxidative damage compared to healthy placentas (Hempstock et al. Reference Hempstock, Jauniaux and Greenwold2003). Moreover, oxidative stress triggers the release of large amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which have been demonstrated to impair embryonic development (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Haimovici and Anderson1987; Kawamura et al. Reference Kawamura, Kawamura and Kumagai2007). Gene expression analysis of implantation failure sites in pigs revealed significantly elevated mRNA levels of IL-1β and TNF-α, suggesting that acute inflammatory responses during the implantation period may lead to implantation failure (Tayade et al. Reference Tayade, Black and Fang2006, Reference Tayade, Fang and Hilchie2007). In subsequent correlation analyses between differential gut microbiota, differential serum metabolites and sow reproductive performance, we also identified the antioxidant-associated bacterium P. succinatutens (Gao et al. Reference Gao, Zhuang and Liu2025), as well as the serum metabolites betaine (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Liu and Mao2022) at P14 and mv-3-glc (Yue et al. Reference Yue, Shi and Yang2025) at P28, which were significantly positively correlated with litter size and the number of normal neonatal piglets. In contrast, compounds known to induce oxidative stress or exacerbate inflammation, such as NNK and citreoviridin (Bai et al. Reference Bai, Jiang and Liu2015; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Guo and Liu2023) were negatively correlated with litter size and number of normal neonatal piglets. These results indicate that the effect of SB–SeY–SIF supplementation in increasing litter size and the number of normal neonatal piglets is positively associated with maternal sex hormone levels and antioxidant status, thereby maintaining an environment favorable for embryo implantation and survival.

In sows, accumulating evidence suggests that the gut microbiota plays a regulatory role in reproductive performance (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Qin and Yan2021; Ye et al. Reference Ye, Hu and Jiang2025, Reference Ye, Luo and Han2024). Previous studies have shown that fecal microbiota transplantation from Meishan sows, a Chinese indigenous breed renowned for its excellent reproductive performance and high litter size, into L × Y sows increased the endometrial glandular area of L × Y recipients and enhanced E2 synthesis in granulosa cells (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Qin and Yan2021). In addition, comparative analyses of the gut microbiota between Meishan and L × Y sows have identified microbial species that may improve litter size by promoting ovulation and enhancing endometrial receptivity (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Qin and Chen2025; Ye et al. Reference Ye, Hu and Jiang2025, Reference Ye, Luo and Han2024). In our study, although dietary SB–SeY–SIF supplementation did not alter microbial α-diversity, it significantly reshaped the composition and structure of the gut microbiota. SB–SeY–SIF supplementation increased the relative abundance of S. alactolyticus at both P14 and P28. As a potential probiotic, S. alactolyticus has antioxidant effects and shows great potential for application in livestock production (Gu et al. Reference Gu, Wang and Wang2024; Hao et al. Reference Hao, Zhang and Zhang2013). In the correlation analyses between reproductive performance and gut microbiota at the species level, we identified several microbial species that were significantly positively correlated with litter size. At P14, P. succinatutens, a core commensal in the pig intestine, has been shown to enhance intestinal epithelial barrier function, and improve intestinal morphology in germ-free mice (Hu et al. Reference Hu, Chen and Ma2024), as well as enhancing host antioxidant capacity (Gao et al. Reference Gao, Zhuang and Liu2025). At P28, P. merdae was identified as a key bacterial species and was significantly positively correlated with litter size. Notably, decreased abundance of P. merdae during pregnancy has been associated with impaired host immune function and increased susceptibility to sepsis (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wu and Li2023), while early pregnancy SB–SeY–SIF supplementation effectively enhanced the abundance of this bacteria. These results suggest that the increased litter size observed with SB–SeY–SIF supplementation is associated with improvements in the gut microbiota. Despite the beneficial effects of SB–SeY–SIF supplementation on gut microbial modulation during early pregnancy, we observed a reduction in the abundance of Akkermansia, a genus known to play a positive role in maintaining host health and combating diseases (Cani et al. Reference Cani, Depommier and Derrien2022; Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Zhu and Sun2025). Previous studies have found that dietary Se supplementation reduces the abundance of Akkermansia (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Shi and Chen2024; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Wu and Wang2022), and our findings further support this observation. The mechanisms underlying Se-mediated suppression of Akkermansia growth warrant further investigation to address the critical question of maintaining optimal Akkermansia abundance under Se supplementation diet while preserving host health.

To further investigate the maternal metabolic effects following SB-SeY-SIF supplementation, we performed untargeted metabolomic profiling of serum samples collected during early pregnancy. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differential metabolites revealed that arachidonic acid metabolism was significantly enriched at both P14 and P28. Arachidonic acid plays a crucial role in reproductive physiology by regulating the cytosolic phospholipase A2α/cyclooxygenase-2 pathway, thereby inducing prostaglandin (PGs) synthesis, which are essential for endometrial decidualization (Wang and Dey Reference Wang and Dey2006). Notably, our metabolomic data showed that arachidonic acid was significantly upregulated, while PGF2α was significantly downregulated at P28. PGF2α promotes uterine contractions (de Assis et al. Reference de Assis, Kayisli and Ozmen2024) and exerts detrimental effects on embryo implantation. These results demonstrate that dietary supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF maintained embryo implantation by upregulating the arachidonic acid pathway while specifically reducing PGF2α. Moreover, steroid hormone biosynthesis and ovarian steroidogenesis pathways were significantly enriched at P14 and P28, respectively. Steroid hormones are a class of important lipophilic hormones primarily synthesized in the adrenal glands, gonads, and placenta. During early pregnancy, P4 suppresses uterine contractions and induces decidualization of endometrial stromal cells, facilitating embryo implantation and nutrient exchange. E2 works in synergy with P4 to enhance endometrial receptivity (Dias Da Silva et al. Reference Dias Da Silva, Wuidar and Zielonka2024). Our measurements of maternal serum sex hormones during early pregnancy further indicate that E2 and P4 may play key roles in promoting embryo implantation following SB–SeY–SIF supplementation. Correlation analysis between reproductive performance and differential serum metabolites revealed that betaine at P14 were positively correlated with litter size. Betaine, a naturally occurring compound widely found in plants and animals, possesses antioxidant properties (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Liu and Mao2022). In addition, betaine enhances the synthesis of E2 and P4, while promoting embryonic development and increasing neonatal piglets birth weight (Abnosi et al. Reference Abnosi, Tabandeh and Mosavi-Aroo2023; Christensen et al. Reference Christensen, Faquette and Gebert2025; Jia et al. Reference Jia, Song and Gao2015), suggesting its potential role in enhancing reproductive performance. Moreover, as a methyl donor, betaine participates in methylation reactions by transferring a methyl group to homocysteine under enzymatic catalysis, thereby regenerating methionine. Notably, our study identified a negative correlation between homocysteine levels and litter size, consistent with previous findings that the accumulation of homocysteine impairs embryo implantation and development (Matte et al. Reference Matte, Guay and Girard2006). These findings suggest that supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF may influence reproductive outcomes in sows by improving maternal metabolic status.

Secondary metabolites derived from the gut microbiota also play important roles in regulating sow reproductive performance. Notably, KEGG pathway-enrichment analysis of differential fecal metabolites revealed that tryptophan metabolism was commonly enriched at both P14 and P28. Previous studies have shown that dietary supplementation with tryptophan during early gestation enhances tryptophan metabolism in sows, thereby improving reproductive performance (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Xue and Li2025). Our findings further support that microbial tryptophan metabolism may influence sow reproductive outcomes. In addition, estriol levels in P14 feces were significantly increased in the SB–SeY–SIF group and showed a strong positive correlation with both litter size and the number of normal neonatal piglets. Estriol, a form of estrogen, was elevated in the feces of the SB–SeY–SIF group sows, suggesting that the gut microbiota may participate in its biosynthesis or conversion. Furthermore, correlation analysis between differential fecal metabolites and reproductive performance indicated that PGI₂ levels at both P14 and P28 were highly positively correlated with litter size and normal neonatal piglet numbers. PGI₂ is known to promote uterine epithelial decidualization, which is critical for embryo implantation (Cong et al. Reference Cong, Diao and Zhao2006; Ye et al. Reference Ye, Hama and Contos2005). Collectively, these results suggest that microbial biosynthetic and metabolic processes may contribute to the regulation of embryo implantation in sows, ultimately affecting reproductive performance.

In this study, we used sows of 6–7 parity, whose reproductive performance has already declined compared with that of younger sows. Therefore, whether the combined additive SB–SeY–SIF exerts similar regulatory effects on reproductive performance during early pregnancy in replacement gilts or low parities sows remains to be rigorously validated. Future studies may focus on evaluating the effects of SB–SeY–SIF supplementation on reproductive performance across sows of different parities. In addition, this study included only a composite supplementation group and a control group, without single-component control groups (SB alone, SeY alone, and SIF alone). Therefore, our research was unable to determine the specific advantages of SB–SeY–SIF compared with individual components, nor could we identify which component contributed to the improvement in metabolic status and reproductive performance. Future experiments should incorporate these single-supplement groups to elucidate the specific roles of the three components during early pregnancy. Moreover, the dosage of each component in the composite additive was determined based on previous studies and published literature. Thus, only one supplementation ratio was tested. Whether synergistic interactions exist among the three substances, and whether such interactions may alter the optimal dosage of each component, remains unknown. Future research should include multiple treatment groups with varying dose ratios to determine a more effective supplementation strategy.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our research demonstrated that dietary supplementation with SB–SeY–SIF enhances ovarian steroid hormones synthesis, elevates antioxidant capacity, improves gut microbiota and serum metabolic profiles. These synergistic effects create a uterine microenvironment favorable for embryo implantation, which correlates with increases in both litter size and the number of normal neonatal piglets. Moreover, through correlation analysis with reproductive performance, we identified several potential probiotics and metabolites associated with increased litter size, which have important application prospects. Our study indicates that SB–SeY–SIF supplementation during early pregnancy increases litter size and normal neonatal piglet numbers, which is associated with enhanced maternal sex hormone synthesis, improved antioxidant capacity, and beneficial modulation of the gut microbiota, highlighting its potential for practical application in sow production.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/anr.2025.10023

Data availability statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32230099 and 31925037), the Foundation of Hubei Hongshan Laboratory (No. 2021hszd018), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Project 2662023DKPY002). Z.Y. and X.Y. reviewed the literature and designed the experiments. Z.Y., C.Y., Y.H., H.J. and N.C. performed the experiments. Z.Y. analyzed and organized the experimental data. Z.Y. and X.Y. wrote the manuscript. Z.Y., B.X., and X.Y. critically reviewed the manuscript. X.Y. supervised the experiments and obtained the funding. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. We thank all members of the Yan Lab for their assistance during the research process. We also appreciate the Fusui Pig Farm of Guangxi Jiade Animal Husbandry Co., Ltd. for providing the experimental site and comprehensive support. We are grateful to Angel Yeast Co., Ltd. for donating SeY, and to Dr. Yan Li from Guangxi Guilin Layn Natural Ingredients Corp. for providing SIF to support this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.