Impact Statement

In line with sustainable aviation goals, prolific research is being conducted into propeller-driven aircraft. Designs featuring a conventional tractor–propeller configuration typically have 40 % of their lifting surface area immersed in the propeller slipstream. This fraction of area is expected to increase with the development of distributed propulsion systems, which feature multiple propulsors mounted along the span of a lifting surface. The propeller slipstream encountered by the lifting surface is highly unsteady, encompassing a helical system of blade tip and wake vorticity. This vortical system convects over the downstream lifting surface, where it undergoes a cyclic interaction with the developing boundary layer. The unsteady interaction can affect lifting surface performance through local vortex-induced separation of the boundary-layer flow, although this has received limited attention in the literature. Hence, the objective of our work is a quantification of the flow topology associated with the vorticity–boundary-layer interaction and the underlying mechanisms driving incipient, local separation of the boundary layer. Particularly, we resolve all three velocity components in a three-dimensional (3-D) volume encompassing the near-wall advection of the propeller tip vortices, where the concentration of the helical vorticity is expected to cause the strongest adverse interaction with the turbulent boundary layer.

1. Introduction

The growing volume and footprint of air traffic has been motivating the development of more sustainable aircraft (Bonet et al. Reference Bonet, Schellenger, Rawdon, Elmer, Wakayama, Brown and Guo2011). Within these development efforts there has been revived interest in propeller-driven aviation, with modern advancements in propeller-blade design and integration proposing up to 10 %–30 % in fuel savings as compared with the best engines in service (Atanasov et al. Reference Atanasov, Wehrspohn, Kühlen, Cabac, Silberhorn, Kotzem, Dahlmann and Linke2023; Guynn et al. Reference Guynn, Berton, Haller, Hendricks and Tong2012). Their scalability also allows for a multitude of smaller propellers to be combined with emerging hybrid-electric propulsion technology, featured in numerous development programs for next-generation aircraft (De Vries et al. Reference De Vries, Brown and Vos2019; Deere et al. Reference Deere, Viken, Carter, Viken, Wiese and Farr2017). However, the challenge with these configurations still lies in the optimal integration of the propeller onto the airframe, as well as reducing the relatively higher noise levels. Historically, and in modern aviation, the choice has been to install propeller systems in the tractor configuration. For two or more engines this is typically onto a lifting surface such as the main wing or, more unconventionally, onto the tailplane (Van Arnhem et al. Reference Van Arnhem, de Vries, Sinnige, Vos and Veldhuis2022).

Studies have shown that the tractor configuration benefits from more favourable acoustic characteristics as opposed to the pusher configuration, wherein the unsteady impingement of the wing-pylon wake onto the propeller disk leads to additional noise generation (Block & Gentry Reference Block and Gentry1986; Eret et al. Reference Eret, Kennedy, Amoroso, Castellini and Bennett2016; Sinnige et al. Reference Sinnige, De Vries, Corte, Avallone, Ragni, Eitelberg and Veldhuis2018a). Compared with over-the-wing (OTW) propeller configurations that have emerged in the recent past, tractor–propeller systems generally exhibit lower lift-to-drag ratios and higher flyover noise (Broadbent Reference Broadbent1976; Marcus et al. Reference Marcus, de Vries, Kulkarni and Veldhuis2018; Müller et al. Reference Müller, Heinze, Kožulovic, Hepperle and Radespiel2014), but retain important advantages that leave them as an attractive design choice. They have been noted to offer higher propulsive efficiencies than OTW propulsors (Müller et al. Reference Müller, Heinze, Kožulovic, Hepperle and Radespiel2014), and are not subject to viscous interaction with the wing boundary layer (BL). The latter has been reported to be a complex phenomenon, whereby OTW systems can induce as well as be directly affected by BL separation over the wing surface (De Vries et al. Reference De Vries, Van Arnhem, Avallone, Ragni, Vos, Eitelberg and Veldhuis2021; Dekker et al. Reference Dekker, Tuinstra, Baars, Scarano and Ragni2025; Müller et al. Reference Müller, Heinze, Kožulovic, Hepperle and Radespiel2014).

In the tractor–propeller configuration, the downstream lifting surface is exposed to the unsteady impingement of the propeller slipstream. Propeller slipstream vorticity comprises a helical sheet of blade tip and wake vorticity, generated as a result of loading on the propeller blades. At typical propeller–wing separation distances in aeronautical applications, the slipstream has not yet destabilised at the time of impingement onto the lifting surface. The vorticity in the slipstream exhibits high spatio-temporal coherence and resulting induced velocities in the flow over the lifting surface show periodic behaviour, at the blade passage frequency (and its harmonics) of the propeller (Felli Reference Felli2021; Sinnige et al. Reference Sinnige, De Vries, Corte, Avallone, Ragni, Eitelberg and Veldhuis2018 a). The resulting interaction between the vortical structures in the slipstream and the lifting surface has been the topic of many studies (Felli Reference Felli2021; Johnston & Sullivan Reference Johnston and Sullivan1990; Muscari et al. Reference Muscari, Dubbioso and Di Mascio2017; Sinnige et al. Reference Sinnige, De Vries, Corte, Avallone, Ragni, Eitelberg and Veldhuis2018 a; Veldhuis Reference Veldhuis2005).

The unsteady surface pressure fields induced by advecting tip and wake vorticity lead to the generation of additional noise sources (Sinnige et al. Reference Sinnige, De Vries, Corte, Avallone, Ragni, Eitelberg and Veldhuis2018a), while also forcing local modulation of the BL flow (Roosenboom et al. Reference Roosenboom, Heider and Schröder2007; Virgilio et al. Reference Virgilio, Biler, Chaitanya and Ganapathisubramani2024). In particular, Duivenvoorden et al. (Reference Duivenvoorden, Suard, Sinnige and Veldhuis2022) and Hawkswell et al. (Reference Hawkswell, Miller and Pullan2024) show that the propeller slipstream can force large changes in the separation topology over the downstream lifting surface, most prominent in high-lift, high-thrust scenarios. Here, globally advanced BL separation by the slipstream can majorly impact propeller-aircraft performance, such as in take-off or landing, as well as aircraft operating limits. While these studies have reported global modulation of the separation front, the incipient, unsteady mechanisms leading to the early onset of BL separation in tractor–propeller–wing configurations have received limited attention in the literature. We explore these mechanisms within this work, with an aim to enable a more comprehensive understanding of viscous propeller–wing interaction.

A central factor to the vortex BL dynamics is the strength and orientation of the impinging vorticity, which can strongly affect local induced velocities and in turn the character of the viscous interaction. This has been observed as strong local advancement of the separation front over the lifting surface in the vicinity of the propeller blade-tip regions (Duivenvoorden et al. Reference Duivenvoorden, Suard, Sinnige and Veldhuis2022), where the BL flow is exposed to the passage of propeller tip vortices. The concentrated tip vorticity convecting over the downstream lifting surface is largely focused in the wall-normal direction, in the near-wall region. However, the extent of streamwise and spanwise tilt of the tip vortices is strongly dependent on their interaction with the leading edge of the lifting surface, with the leading-edge thickness to vortex core size reported as a governing parameter (Felli Reference Felli2021). For thin leading edges, with radii comparable to the vortex core radius, the vortices are ‘sliced’ as they convect over the surface and retain their largely wall-normal character. As leading edge thickness increases, the vortices experience significant distortion as they wrap around the leading edge, exhibiting a strong axial tilt. The impingement of concentrated vortices onto walls has been extensively studied in the literature, albeit with only a single component of vorticity. Bodstein et al. (Reference Bodstein, George and Hui1996) and Patel and Hancock (Reference Patel and Hancock1974) detail the dynamics of streamwise-vortex interaction with wings, Felli (Reference Felli2021), Johnston & Sullivan (Reference Johnston and Sullivan1990), Krishnamoorthy and Marshall (Reference Krishnamoorthy and Marshall1998) and Marshall and Krishnamoorthy (Reference Marshall and Krishnamoorthy1997) have described orthogonal vortex impingement in the context of propeller–wing and blade–vortex interaction studies while numerous other studies (Conlisk Reference Conlisk1998; De Vries et al. Reference De Vries, Van Arnhem, Avallone, Ragni, Vos, Eitelberg and Veldhuis2021; Didden & Ho Reference Didden and Ho1985; Peridier et al. Reference Peridier, Smith and Walker1991; Virgilio et al. Reference Virgilio, Biler, Chaitanya and Ganapathisubramani2024) have dealt with spanwise vortices convecting over BLs.

Although the propeller tip vortex is inherently three-dimensional, its largely wall-normal orientation in the near-wall region results in predominantly wall-parallel induced velocities over the lifting surface. On the outboard side of the vortex core, these inductions act to oppose the incoming flow and vice versa on the inboard side. The resulting strong local deceleration on the outboard side can promote sudden, local BL separation in these regions. However, this interaction is inherently unsteady, with the transient passage of tip vorticity temporally modulating the separation process. In this light, it is important to establish some hallmarks of unsteady BL separation. In contrast to the condition of vanishing shear stress at the wall for a BL undergoing steady separation, it is well known that this does not necessarily hold in the unsteady scenario (Didden & Ho Reference Didden and Ho1985; Rott Reference Rott1956; Sears & Telionis Reference Sears and Telionis1975). Additionally, the presence of flow reversal is not an indicator of separation (Sears & Telionis Reference Sears and Telionis1975; Yapalparvi & Van Dommelen Reference Yapalparvi and Van Dommelen2012), even more so in 3-D flows (Cousteix Reference Cousteix1986; Surana et al. Reference Surana, Jacobs, Grunberg and Haller2008). Rather, unsteady separation has been described through the Moore–Rott–Sears condition (Moore Reference Moore and Görtler1958; Rott Reference Rott1956; Sears Reference Sears1956), occurring where the shear stress vanishes at a point within the BL, as opposed to at the wall. This is at a streamwise location where the velocity at this point vanishes within a frame of reference moving with the separation point. Van Dommelen and Shen (Reference Van Dommelen and Shen1980) describe an abrupt thickening of the BL at this point, with BL vorticity erupting into a narrow spike normal to the wall. The erupting shear layer is unstable and typically rolls up into a vortical structure (Chuang & Conlisk Reference Chuang and Conlisk1989; Didden & Ho Reference Didden and Ho1985; Peridier et al. Reference Peridier, Smith and Walker1991; Serra et al. Reference Serra, Crouzat, Simon, Vétel and Haller2020). Comprehensive studies on the unsteady separation process have been reviewed in Cassel and Conlisk (Reference Cassel and Conlisk2014), Serra et al. (Reference Serra, Crouzat, Simon, Vétel and Haller2020) and Simpson (Reference Simpson1989), with it being a feature of vortices convecting over BL flows.

Numerous studies have described the dynamics of propeller vorticity itself over a downstream lifting surface, specialised cases of viscous vortex–wall interactions and the unsteady separation process. However, the coupling between these mechanisms is yet to be fully understood in the context of an applied propeller–wing scenario. Thus, the focus of our study is to address the viscous nature of propeller–wing interaction from a fundamental perspective, through the following unanswered research questions on vortex–boundary-layer interaction.

-

1. What is the local spatio-temporal organisation of a turbulent boundary layer (TBL) modulated by tip vorticity generated by an upstream propeller? Here, the 3-D vorticity is primarily oriented in a direction wall normal to the surface over which the TBL develops.

-

2. To what extent does the passage of the tip vortices lead to deceleration in the near-wall flow, affecting potential TBL separation?

This study attempts to answer these questions through experimental observations on a TBL developing over an elliptic leading edge encountering a propeller slipstream. This arrangement is further detailed in § 2. A discussion of the time-averaged flow features is presented first, highlighting overall slipstream organisation and the time-averaged imprint of the unsteady interaction on the BL. We then conduct an analysis of the unsteady fluid structures through triple decomposition of the flow field, separating the large-scale periodic motion from unsteadiness in the BL. Here, we investigate the phase-locked dynamics of the propeller tip vorticity and TBL, and detail the inherent three-dimensionality of the flow field.

2. Experimental methodology

2.1. Wind-tunnel model

Experiments were conducted at the low-speed Small Low Turbulence facility, an open return type wind tunnel located at the Delft University of Technology. The tunnel was operated in an open-jet configuration, with a 900 mm

![]() $\times$

600 mm rectangular nozzle, and a turbulence intensity of approximately

$\times$

600 mm rectangular nozzle, and a turbulence intensity of approximately

![]() $0.1 \,\%$

at the conditions tested. The tractor–propeller configuration is simulated using an off-the-shelf (OTS) propeller and a flat plate with an elliptic leading edge (LE), both mounted onto a custom aluminium beam structure. Figure 1 presents a simplified schematic of the relative positioning of the propeller, plate and measurement systems. The propeller sits to the side of the plate, with the entire set-up placed semi-immersed in the open jet of the wind tunnel. The coordinate system was selected to be right handed, with the respective positive directions indicated by the axes in figure 1. The origins of the coordinate system for

$0.1 \,\%$

at the conditions tested. The tractor–propeller configuration is simulated using an off-the-shelf (OTS) propeller and a flat plate with an elliptic leading edge (LE), both mounted onto a custom aluminium beam structure. Figure 1 presents a simplified schematic of the relative positioning of the propeller, plate and measurement systems. The propeller sits to the side of the plate, with the entire set-up placed semi-immersed in the open jet of the wind tunnel. The coordinate system was selected to be right handed, with the respective positive directions indicated by the axes in figure 1. The origins of the coordinate system for

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

are the start of the plate LE, flat section of the plate upper surface and propeller axis, respectively.

$z$

are the start of the plate LE, flat section of the plate upper surface and propeller axis, respectively.

Figure 1. Experimental propeller–plate configuration semi-immersed in the open-jet flow. The shaded grey region represents part of the wind-tunnel nozzle exit area while the shaded green region indicates the plate-on particle image velocimetry (PIV) field(s) of view (FOV). (a) Front view. (b) Top view. The magenta and cyan dots indicate the origins of the

![]() $x, y, z$

and

$x, y, z$

and

![]() $x_p, y_p, z_p$

(§ 3) coordinate systems respectively. (c) Side view of semi-elliptic LE and PIV measurement domain.

$x_p, y_p, z_p$

(§ 3) coordinate systems respectively. (c) Side view of semi-elliptic LE and PIV measurement domain.

The semi-immersed nature of the set-up was selected to allow for more accessible measurements of the small-scale BL interactions, through scaling up of the propeller and plate. This was supported by the region of interest for these interactions lying in the vicinity of the propeller-blade tip, away from the open-jet shear layer and propeller hub flow. Section 3 details the state of the slipstream in the vicinity of the blade tip, to further support this configuration. Propeller–wing integration effects such as the nacelle–BL interaction were then also neglected. Additionally, the open-jet configuration enables near-complete optical access with the PIV measurement system.

2.1.1. Plate geometry and operating conditions

Boundary-layer measurements were conducted over a flat plate with a semi-elliptic LE, depicted in figure 1(c). The dimensions of the ellipse were selected to ensure smooth attachment of the flow at the LE, while limiting the effect of LE curvature on the slipstream–BL interaction. After termination of the elliptic section, the plate transitions into being fully flat and extends 1.1 m downstream. A full-span strip of zigzag tape (0.79 mm thickness,

![]() $60^\circ$

apex angle) was positioned 30 mm downstream of the LE on both its upper and lower surfaces, to induce laminar-to-turbulent transition of the BL.

$60^\circ$

apex angle) was positioned 30 mm downstream of the LE on both its upper and lower surfaces, to induce laminar-to-turbulent transition of the BL.

The plate was placed 350 mm downstream of the nozzle, resulting in a propeller–plate separation of

![]() $x_{\textrm {LE}}/D \sim 0.3$

, where

$x_{\textrm {LE}}/D \sim 0.3$

, where

![]() $D$

is the propeller diameter. This was selected such that the shear layer of the open jet was sufficiently far from the measurement domain around the blade tip, estimated from a previous characterisation of the wind-tunnel facility (Knoop et al. Reference Knoop, Hassanein and Baars2026). The choice of

$D$

is the propeller diameter. This was selected such that the shear layer of the open jet was sufficiently far from the measurement domain around the blade tip, estimated from a previous characterisation of the wind-tunnel facility (Knoop et al. Reference Knoop, Hassanein and Baars2026). The choice of

![]() $x_{\textrm {LE}}/D$

can have consequences for the propeller–plate interaction (Sinnige Reference Sinnige2018; Veldhuis Reference Veldhuis2005), that were taken into consideration. An estimate of the slipstream age at the plate LE was made, through a ratio of the propeller rotation time scale to that of the free-stream flow (

$x_{\textrm {LE}}/D$

can have consequences for the propeller–plate interaction (Sinnige Reference Sinnige2018; Veldhuis Reference Veldhuis2005), that were taken into consideration. An estimate of the slipstream age at the plate LE was made, through a ratio of the propeller rotation time scale to that of the free-stream flow (

![]() $U_{\infty }/nB x_{\mathrm{LE}}$

, where

$U_{\infty }/nB x_{\mathrm{LE}}$

, where

![]() $n$

is the propeller rotational frequency,

$n$

is the propeller rotational frequency,

![]() $B$

is the number of blades). This was found to be quite close to that of modern turboprop aircraft operating at low values of the advance ratio

$B$

is the number of blades). This was found to be quite close to that of modern turboprop aircraft operating at low values of the advance ratio

![]() $J$

(where

$J$

(where

![]() $J = U_{\infty }/nD$

). Additionally, the upstream influence of the plate on the propeller loading was expected to be very small, due to the plate generating no lift and being of low thickness with respect to the propeller disk.

$J = U_{\infty }/nD$

). Additionally, the upstream influence of the plate on the propeller loading was expected to be very small, due to the plate generating no lift and being of low thickness with respect to the propeller disk.

In order to distinguish between the BL region and the external flow over the plate, a locus of points is extracted where the wall-normal gradient of the

![]() $u$

-velocity profiles runs asymptotically to zero or attains its local maximum. The velocity magnitudes along this locus are considered the local velocities external to the BL flow,

$u$

-velocity profiles runs asymptotically to zero or attains its local maximum. The velocity magnitudes along this locus are considered the local velocities external to the BL flow,

![]() $\overline {U_e}$

. In this process, the nominal BL thickness

$\overline {U_e}$

. In this process, the nominal BL thickness

![]() $\delta$

is estimated using the conventional

$\delta$

is estimated using the conventional

![]() $\delta _{99}$

length scale. This was extracted as the height above the wall at which the velocity profile attains

$\delta _{99}$

length scale. This was extracted as the height above the wall at which the velocity profile attains

![]() $0.99\overline {U_e}$

, and is used for subsequent discussion in this work. Figure 1(c) depicts this, where

$0.99\overline {U_e}$

, and is used for subsequent discussion in this work. Figure 1(c) depicts this, where

![]() $\delta _0$

is the propeller-off, time-averaged

$\delta _0$

is the propeller-off, time-averaged

![]() $\overline {\delta _{99}}$

at the start of the measurement domain. Estimating a BL scale from the position of the local maximum is considered a valid approach for both the propeller-on and -off cases, as an inviscid flow would attain its local maximum at the wall.

$\overline {\delta _{99}}$

at the start of the measurement domain. Estimating a BL scale from the position of the local maximum is considered a valid approach for both the propeller-on and -off cases, as an inviscid flow would attain its local maximum at the wall.

All measurements were conducted at a free-stream inflow velocity of

![]() $U_{\infty }$

= 10 m s

$U_{\infty }$

= 10 m s

![]() $^{-1}$

, limited by torque and power constraints required to operate the propeller. The Reynolds number (

$^{-1}$

, limited by torque and power constraints required to operate the propeller. The Reynolds number (

![]() $Re_{\delta }$

) was estimated to develop in the

$Re_{\delta }$

) was estimated to develop in the

![]() $x\hbox{-}$

direction from 2800 to 4500 within the PIV measurement domain. Additionally, a friction Reynolds number

$x\hbox{-}$

direction from 2800 to 4500 within the PIV measurement domain. Additionally, a friction Reynolds number

![]() $Re _{\tau }$

for the TBL was estimated through a Clauser fit (Clauser Reference Clauser, Dryden and von Kármán1956) of the propeller-off TBL velocity profiles, varying from 170 to 270 over the domain.

$Re _{\tau }$

for the TBL was estimated through a Clauser fit (Clauser Reference Clauser, Dryden and von Kármán1956) of the propeller-off TBL velocity profiles, varying from 170 to 270 over the domain.

2.1.2. Propeller geometry and operating conditions

The propeller used was 3-bladed and 68.58 cm (27 inches) in diameter, with a fixed 34.08 cm (12 inches) pitch. It was manufactured from carbon fibre and is available OTS from Mejzlik Propellers™. A custom electronic speed controller cabinet with a 15 kW power supply unit was used to power the drivetrain system to which the propeller is attached. The propeller drivetrain is mounted onto an aluminium X-95 beam set, which is placed such that the propeller disk plane lies 150 mm downstream of the nozzle exit. The propeller rotates in the counter-clockwise direction when viewed from upstream and is positioned in the

![]() $y-z$

plane for two main purposes: first, to maximise the percentage of its blade immersed in the core flow of the open jet. Second, to maximise the time spent by the immersed blade in core flow within the angular sector above the plate. This allows for the unsteady loading of the blade to adjust to the desired operating condition as it slices into the open jet. In this configuration, approximately 25 % of the propeller disk area is exposed to the wind-tunnel jet, indicated nominally by the shaded grey area in figure 1(a,b).

$y-z$

plane for two main purposes: first, to maximise the percentage of its blade immersed in the core flow of the open jet. Second, to maximise the time spent by the immersed blade in core flow within the angular sector above the plate. This allows for the unsteady loading of the blade to adjust to the desired operating condition as it slices into the open jet. In this configuration, approximately 25 % of the propeller disk area is exposed to the wind-tunnel jet, indicated nominally by the shaded grey area in figure 1(a,b).

The propeller was set to operate at a non-installed thrust coefficient of

![]() $T_c = 1$

(

$T_c = 1$

(

![]() $T_c = 2T/\rho U_{\infty }^2 D^2$

, where

$T_c = 2T/\rho U_{\infty }^2 D^2$

, where

![]() $T$

is thrust,

$T$

is thrust,

![]() $\rho$

is the air density), assuming a fully symmetric condition with uniform inflow over the entire propeller disk. This was nominally selected to simulate the high-thrust condition in which modern turboprop aircraft operate during take-off. As no instrumentation was used to measure the forces on the propeller, the conditions for

$\rho$

is the air density), assuming a fully symmetric condition with uniform inflow over the entire propeller disk. This was nominally selected to simulate the high-thrust condition in which modern turboprop aircraft operate during take-off. As no instrumentation was used to measure the forces on the propeller, the conditions for

![]() $T_c = 1$

were estimated from performance data charts provided by the manufacturer i.e. a propeller rotational speed of

$T_c = 1$

were estimated from performance data charts provided by the manufacturer i.e. a propeller rotational speed of

![]() $n = 48.6$

Hz, corresponding to

$n = 48.6$

Hz, corresponding to

![]() $J = 0.3$

at a uniform speed of

$J = 0.3$

at a uniform speed of

![]() $U_{\infty }$

= 10 m s

$U_{\infty }$

= 10 m s

![]() $^{-1}$

. While

$^{-1}$

. While

![]() $J = 0.3$

is lower than what is typically expected for the simulated scenario, this was limited by the operating range of the propeller, with a maximum propulsive

$J = 0.3$

is lower than what is typically expected for the simulated scenario, this was limited by the operating range of the propeller, with a maximum propulsive

![]() $J \sim 0.55$

. Within this operating range, the spatial separation between tip vortices (

$J \sim 0.55$

. Within this operating range, the spatial separation between tip vortices (

![]() $\sim U_\infty /nB$

) does not increase much for a large decrease in the thrust coefficient. Thus,

$\sim U_\infty /nB$

) does not increase much for a large decrease in the thrust coefficient. Thus,

![]() $J=0.3$

was selected primarily for the blade loading condition, over tip-vortex spacing, for the current study. It should also be noted that

$J=0.3$

was selected primarily for the blade loading condition, over tip-vortex spacing, for the current study. It should also be noted that

![]() $T_c = 1$

for the 3-bladed propeller likely results in a higher loading per blade than what would be typical for a multi-bladed aircraft propeller operating at the same thrust coefficient. A consequence of this is stronger tip vorticity in the slipstream.

$T_c = 1$

for the 3-bladed propeller likely results in a higher loading per blade than what would be typical for a multi-bladed aircraft propeller operating at the same thrust coefficient. A consequence of this is stronger tip vorticity in the slipstream.

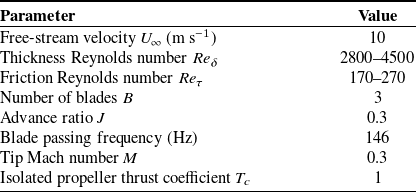

The rotational speed of the propeller was measured with a differential rotary encoder (1024 CPR) mounted onto the drivetrain shaft. The encoder reading was used to control propeller rotational frequency with a custom-made control loop and features a 1-per-revolution trigger signal that was used to synchronise the phase-locked PIV measurements. A summary of the operating conditions for the propeller–plate set-up is presented in table 1.

Table 1. Operating conditions for the propeller-plate wind-tunnel set-up

2.2. Measurement techniques

2.2.1. Static wall-pressure measurements

The LE section of the plate was equipped with 2 rows of 16 static pressure taps each, spaced 10 mm apart from each other. The spanwise positioning of the two rows was selected in accordance with the positioning of the propeller with respect to the plate, being at

![]() $z/R = 0.7$

and

$z/R = 0.7$

and

![]() $z/R = 1.3$

, respectively. This was to enable quantification of the streamwise time-averaged wall pressure and pressure gradient both at a location within and outside of the propeller slipstream. The static pressure was acquired with a custom-made pressure scanner (

$z/R = 1.3$

, respectively. This was to enable quantification of the streamwise time-averaged wall pressure and pressure gradient both at a location within and outside of the propeller slipstream. The static pressure was acquired with a custom-made pressure scanner (

![]() $\pm 160$

Pa range, with a nominal accuracy of

$\pm 160$

Pa range, with a nominal accuracy of

![]() $\pm 4$

Pa) at a frequency of 10 Hz for 15 s, for both the propeller-off and propeller-on cases. These acquisitions were performed for each spanwise location (

$\pm 4$

Pa) at a frequency of 10 Hz for 15 s, for both the propeller-off and propeller-on cases. These acquisitions were performed for each spanwise location (

![]() $z$

-location) of the measured PIV planes and averaged together to reduce uncertainty in the measured static pressure distribution.

$z$

-location) of the measured PIV planes and averaged together to reduce uncertainty in the measured static pressure distribution.

2.2.2. Particle image velocimetry

Low-speed stereoscopic-PIV was used to quantify the interaction between the propeller tip vortices and plate BL, through velocity field measurements near the LE region of the flat plate. Figure 1(a) depicts the positioning of the two-camera and laser system, which provided a field of view (FOV) of 90 mm

![]() $\times$

60 mm for each position of the stereo-image plane. The camera system was manually translated downstream to a second overlapping FOV of the same dimensions, for a second set of independent velocity field acquisitions. This allowed for a streamwise extension of the FOV to 140 mm

$\times$

60 mm for each position of the stereo-image plane. The camera system was manually translated downstream to a second overlapping FOV of the same dimensions, for a second set of independent velocity field acquisitions. This allowed for a streamwise extension of the FOV to 140 mm

![]() $\times$

60 mm, while maintaining resolution in the wall-normal direction. The two cameras and laser were additionally each mounted onto their own Zaber X-LRQ traverse, with movement of all three synchronised through external controllers. This was to enable precise translation of the PIV set-up in the out-of-plane direction. Independent acquisitions were conducted for each FOV at 16 spanwise locations separated by 4 mm, with a total spanwise measurement extent of 60 mm as shown in figure 1(a,b). The selected arrangement of the PIV set-up is used to obtain a scan of the slipstream in the region encompassing the tip vortices, allowing for a pseudo-volumetric reconstruction of the flow topology.

$\times$

60 mm, while maintaining resolution in the wall-normal direction. The two cameras and laser were additionally each mounted onto their own Zaber X-LRQ traverse, with movement of all three synchronised through external controllers. This was to enable precise translation of the PIV set-up in the out-of-plane direction. Independent acquisitions were conducted for each FOV at 16 spanwise locations separated by 4 mm, with a total spanwise measurement extent of 60 mm as shown in figure 1(a,b). The selected arrangement of the PIV set-up is used to obtain a scan of the slipstream in the region encompassing the tip vortices, allowing for a pseudo-volumetric reconstruction of the flow topology.

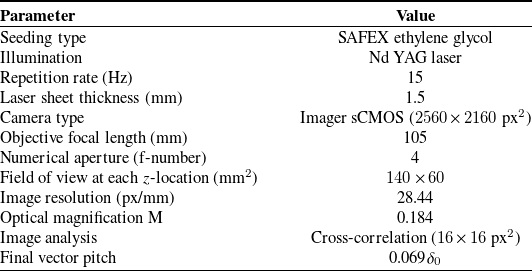

Table 2. Particle image velocimetry illumination and imaging

The fluid was seeded using a SAFEX Twin Fog DP generator, with a mixture of diethylene-glycol and water, and illuminated using a 200 mJ Quantel Evergreen low-speed laser. An optical lens arrangement consisting of two spherical lenses and one cylindrical lens of focal lengths

![]() $f = -50, 100$

and

$f = -50, 100$

and

![]() $-100$

respectively was selected to shape the beam into a 1.5 mm thick laser sheet. The laser pulse separation time was tuned for a minimum particle displacement of 5–6 pixels in low-speed regions. The two cameras used for acquisitions were identical, each a 16-bit LaVision Imager sCMOS with a 2560

$-100$

respectively was selected to shape the beam into a 1.5 mm thick laser sheet. The laser pulse separation time was tuned for a minimum particle displacement of 5–6 pixels in low-speed regions. The two cameras used for acquisitions were identical, each a 16-bit LaVision Imager sCMOS with a 2560

![]() $\times$

2160 px

$\times$

2160 px

![]() $^2$

sensor and a pixel size of 6.5 μm. A Nikkor 105 mm lens with a Scheimpflug adaptor was mounted onto each camera to allow for the required stereoscopic FOV, while a numerical aperture (f-number) of 4 was set to obtain a particle image diameter of 2–3 pixels and a depth of field of 5 mm. Particle image pairs were acquired at a frequency of 15 Hz and processed using the LaVision DaVis 10.2 software. Stereoscopic cross-correlation was performed with 48

$^2$

sensor and a pixel size of 6.5 μm. A Nikkor 105 mm lens with a Scheimpflug adaptor was mounted onto each camera to allow for the required stereoscopic FOV, while a numerical aperture (f-number) of 4 was set to obtain a particle image diameter of 2–3 pixels and a depth of field of 5 mm. Particle image pairs were acquired at a frequency of 15 Hz and processed using the LaVision DaVis 10.2 software. Stereoscopic cross-correlation was performed with 48

![]() $\times$

48 px

$\times$

48 px

![]() $^2$

and 16

$^2$

and 16

![]() $\times$

16 px

$\times$

16 px

![]() $^2$

as the window sizes for the initial and final passes with 50 % overlap, resulting in a final spatial resolution of 0.32 mm. Spurious vectors were removed after each computation stage through rejecting vectors with a stereoscopic reconstruction error of less than 0.5 px, and through the use of a three-pass regional median filter (Westerweel Reference Westerweel1994). This resulted in an uncertainty of less than 0.8 % in the averaged velocity fields.

$^2$

as the window sizes for the initial and final passes with 50 % overlap, resulting in a final spatial resolution of 0.32 mm. Spurious vectors were removed after each computation stage through rejecting vectors with a stereoscopic reconstruction error of less than 0.5 px, and through the use of a three-pass regional median filter (Westerweel Reference Westerweel1994). This resulted in an uncertainty of less than 0.8 % in the averaged velocity fields.

Uncorrelated acquisitions of 1000 image pairs were done for the propeller-off and propeller-on cases, triggered using a LaVision programmable timing unit (PTU). In addition to this, phase-locked measurements were performed for the propeller-on case by synchronising the PTU trigger to the 1P signal obtained from the propeller encoder. In the current work we consider three phases of

![]() $\phi = 0^\circ$

,

$\phi = 0^\circ$

,

![]() $\phi = 40^\circ$

and

$\phi = 40^\circ$

and

![]() $\phi = 80^\circ$

. For each phase a total of 400 image pairs were acquired for construction of the phase-averaged velocity statistics. Table 2 summarises the specifications of the PIV measurement system.

$\phi = 80^\circ$

. For each phase a total of 400 image pairs were acquired for construction of the phase-averaged velocity statistics. Table 2 summarises the specifications of the PIV measurement system.

3. Isolated propeller slipstream

Due to the semi-immersed nature of the set-up described in § 2.1, it is important to first characterise the flow field associated with the isolated propeller slipstream, without the downstream plate installed. This is to ensure that the slipstream is coherent and representative of a non-installed propeller slipstream in uniform inflow conditions, primarily within the plate-on measurement domain. Solely for the analysis of the isolated propeller slipstream, the origin of the coordinate system is selected to be at the propeller disk, axis and hub for the

![]() $x_p$

,

$x_p$

,

![]() $y_p$

and

$y_p$

and

![]() $z_p\hbox{-}$

directions, respectively.

$z_p\hbox{-}$

directions, respectively.

Figure 2. Isolated propeller slipstream. (a) Time-averaged velocity contours with phase-locked vorticity isolines (

![]() $\phi = 80^\circ$

) in the axial–radial plane,

$\phi = 80^\circ$

) in the axial–radial plane,

![]() $y_p/R = 0$

. Solid and dashed black lines represent negative and positive values of

$y_p/R = 0$

. Solid and dashed black lines represent negative and positive values of

![]() $\overline {\omega _y}^{\textrm {PL}}$

, respectively. The grey line indicates the location of the plate LE in the installed condition, green box is the plate-on PIV measurement domain. (b) Time-averaged velocity contours with in-plane velocity vectors overlayed,

$\overline {\omega _y}^{\textrm {PL}}$

, respectively. The grey line indicates the location of the plate LE in the installed condition, green box is the plate-on PIV measurement domain. (b) Time-averaged velocity contours with in-plane velocity vectors overlayed,

![]() $x_p/R = 0.6$

. Dashed line is the propeller disk, grey box is a cross-section of the plate in the installed condition.

$x_p/R = 0.6$

. Dashed line is the propeller disk, grey box is a cross-section of the plate in the installed condition.

An axial–radial slice of the time-averaged

![]() $u$

-velocity component is presented in figure 2(a). The flow field here is distinctly divided into two zones: one with flow at a velocity close to

$u$

-velocity component is presented in figure 2(a). The flow field here is distinctly divided into two zones: one with flow at a velocity close to

![]() $U_\infty$

, and the other a region of higher-velocity fluid. The latter is the propeller slipstream, where the total pressure imparted by the propeller leads to an acceleration of the flow. The changeover between slipstream and free stream occurs at approximately

$U_\infty$

, and the other a region of higher-velocity fluid. The latter is the propeller slipstream, where the total pressure imparted by the propeller leads to an acceleration of the flow. The changeover between slipstream and free stream occurs at approximately

![]() $0.9R$

, due to contraction of the slipstream upstream of the measurement domain. The

$0.9R$

, due to contraction of the slipstream upstream of the measurement domain. The

![]() $u$

-velocity is also seen to attain its local maximum in the

$u$

-velocity is also seen to attain its local maximum in the

![]() $z_p$

-direction at

$z_p$

-direction at

![]() $z_p/R \sim 0.7$

, which is consistent with propellers typically featuring maximum blade loading around the 70 % blade-radius location. In addition to the time-averaged velocity contours, isolines of the phase-locked out-of-plane

$z_p/R \sim 0.7$

, which is consistent with propellers typically featuring maximum blade loading around the 70 % blade-radius location. In addition to the time-averaged velocity contours, isolines of the phase-locked out-of-plane

![]() $\omega _y$

-component of vorticity are shown. Here, the spatial organisation of the propeller-blade tip and wake vorticity can be clearly observed. Close to the slipstream boundary, propeller-blade vorticity rolls up into concentrated, coherent tip vortices. Further inboard, the trace of the blade wakes can be seen, with their in-plane inclination due to self-induction by the entire helical vortex system. At close to

$\omega _y$

-component of vorticity are shown. Here, the spatial organisation of the propeller-blade tip and wake vorticity can be clearly observed. Close to the slipstream boundary, propeller-blade vorticity rolls up into concentrated, coherent tip vortices. Further inboard, the trace of the blade wakes can be seen, with their in-plane inclination due to self-induction by the entire helical vortex system. At close to

![]() $z_p/R = 0.7$

,

$z_p/R = 0.7$

,

![]() $\overline {\omega _y}^{\textrm {PL}}$

in the wake changes sign. This is also associated with a maximum loading point on the propeller blade, where the radial loading gradient over the blade changes sign. The LE of the plate in the installed condition, as well as the PIV measurement domain, are also indicated in Figure 2. The PIV domain lies on the outboard side of the slipstream here. However, spanwise deflection of the slipstream over the plate surface in the installed condition ensures it is correctly positioned for those measurements. Finally, it should be noted that there is still mild axial development of the slipstream beyond the plate LE. This implies the presence of an imposed favourable pressure gradient (FPG) by the slipstream on the plate in the installed condition.

$\overline {\omega _y}^{\textrm {PL}}$

in the wake changes sign. This is also associated with a maximum loading point on the propeller blade, where the radial loading gradient over the blade changes sign. The LE of the plate in the installed condition, as well as the PIV measurement domain, are also indicated in Figure 2. The PIV domain lies on the outboard side of the slipstream here. However, spanwise deflection of the slipstream over the plate surface in the installed condition ensures it is correctly positioned for those measurements. Finally, it should be noted that there is still mild axial development of the slipstream beyond the plate LE. This implies the presence of an imposed favourable pressure gradient (FPG) by the slipstream on the plate in the installed condition.

Additionally, figure 2(b) presents contours of the

![]() $u$

-velocity component and vectors of the in-plane velocity within a plane parallel to the propeller actuator disk (

$u$

-velocity component and vectors of the in-plane velocity within a plane parallel to the propeller actuator disk (

![]() $x_p/R = 0.6$

). Once more, a well-organised slipstream region can be observed. The orientation of the in-plane velocity vectors represents the combined effect of propeller-induced swirl and radial contraction of the slipstream (Veldhuis Reference Veldhuis2005). The downward flow within the slipstream is consistent with the measurements being located on the downgoing blade side of the propeller. The effect of slipstream contraction is the presence of radial flow toward the propeller axis, which is maximum near the slipstream edge. This radial velocity typically persists outside of the slipstream, which is seen in the inward orientation of the vectors in figure 2(b) for

$x_p/R = 0.6$

). Once more, a well-organised slipstream region can be observed. The orientation of the in-plane velocity vectors represents the combined effect of propeller-induced swirl and radial contraction of the slipstream (Veldhuis Reference Veldhuis2005). The downward flow within the slipstream is consistent with the measurements being located on the downgoing blade side of the propeller. The effect of slipstream contraction is the presence of radial flow toward the propeller axis, which is maximum near the slipstream edge. This radial velocity typically persists outside of the slipstream, which is seen in the inward orientation of the vectors in figure 2(b) for

![]() $z_p/R \gt 0.9$

. It is also seen that the PIV measurement domain lies away from the shear layer of the open jet, which is identified as the velocity deficit region at the bottom-right of the domain in figure 2(b).

$z_p/R \gt 0.9$

. It is also seen that the PIV measurement domain lies away from the shear layer of the open jet, which is identified as the velocity deficit region at the bottom-right of the domain in figure 2(b).

The selected semi-immersed wind-tunnel configuration implies that the propeller slipstream is not rotationally symmetric, as would be the case for an isolated propeller with uniform inflow. However, the features described above indicate that the flow field generated by the current propeller configuration locally exhibits the characteristics of an isolated propeller slipstream within the plate-on PIV measurement domain. As such, the subsequent analyses conducted in this work are considered representative of propeller-vortex associated BL interactions.

4. Time-averaged interacting slipstream

4.1. Triple decomposition of velocity fields

Statistical analysis of the interacting flow field is carried out through two types of averaging, which yield either time-averaged (

![]() $\overline {u_i}$

) or phase-locked (

$\overline {u_i}$

) or phase-locked (

![]() $\overline {u_i}^{\text{PL}}$

) velocity quantities, through the following operations, respectively:

$\overline {u_i}^{\text{PL}}$

) velocity quantities, through the following operations, respectively:

with

![]() $i = 1,2,3$

corresponding to the axial, wall-normal and spanwise coordinate directions, respectively. Using the above definitions for these operations, we employ a triple decomposition of the flow field (Ambrogi et al. Reference Ambrogi, Piomelli and Rival2022; Hussain & Reynolds Reference Hussain and Reynolds1970) where the instantaneous flow field is separated into time-averaged, periodic and stochastic components as

$i = 1,2,3$

corresponding to the axial, wall-normal and spanwise coordinate directions, respectively. Using the above definitions for these operations, we employ a triple decomposition of the flow field (Ambrogi et al. Reference Ambrogi, Piomelli and Rival2022; Hussain & Reynolds Reference Hussain and Reynolds1970) where the instantaneous flow field is separated into time-averaged, periodic and stochastic components as

The various components of the triple decomposition can be connected to each other through the relations

It follows from (4.4) that the periodic velocity fields

![]() $\widetilde {u}_i$

can be obtained by subtracting the time-averaged velocity fields from the phase-locked velocities, with the components of the triple-decomposed

$\widetilde {u}_i$

can be obtained by subtracting the time-averaged velocity fields from the phase-locked velocities, with the components of the triple-decomposed

![]() $u$

-velocity presented in Figure 3. Comparison between Figures 3(b) and 3(c) shows that the large-scale periodic perturbation is of overall higher amplitude than the turbulent fluctuations, with the spatial standard deviation of the former being approximately 3 times larger than the latter. This implies that the TBL response is primarily driven by the tip-vortex-induced velocities, while the turbulence field plays a smaller, secondary role. Thus, our discussion of unsteady flow features in this study will focus on the phase-locked velocity fields, which is presented later in § 5.

$u$

-velocity presented in Figure 3. Comparison between Figures 3(b) and 3(c) shows that the large-scale periodic perturbation is of overall higher amplitude than the turbulent fluctuations, with the spatial standard deviation of the former being approximately 3 times larger than the latter. This implies that the TBL response is primarily driven by the tip-vortex-induced velocities, while the turbulence field plays a smaller, secondary role. Thus, our discussion of unsteady flow features in this study will focus on the phase-locked velocity fields, which is presented later in § 5.

Figure 3. Contours of the triple-decomposed

![]() $u$

-velocity components at

$u$

-velocity components at

![]() $z/R = 1$

,

$z/R = 1$

,

![]() $\phi = 0^\circ$

. (a) Time averaged (

$\phi = 0^\circ$

. (a) Time averaged (

![]() $\overline {u}/U_\infty$

), (b) periodic (

$\overline {u}/U_\infty$

), (b) periodic (

![]() $\widetilde {u}/U_\infty$

) and (c) stochastic (

$\widetilde {u}/U_\infty$

) and (c) stochastic (

![]() $u'/U_\infty$

).

$u'/U_\infty$

).

4.2. Time-averaged velocity fields

The interaction between a propeller slipstream and downstream surface can be described in a steady sense through time averaging of the flow field. We discuss the pertinent features of this time-averaged interaction here to establish the mean flow topology of the slipstream within the measurement domain as a baseline for later analyses. Figure 4 presents slices of the flow field along the three orthogonal planes within the measurement domain. The propeller acts as an actuator, adding momentum to the flow within its slipstream. This is evidently seen in figure 4(a), a wall-parallel slice at 15 mm (

![]() $y/R = 0.044$

,

$y/R = 0.044$

,

![]() $y/\delta _0 = 3.41$

) off the surface, where fluid is approximately 1.7 times the free-stream velocity. The interior of the slipstream can thus be identified as this region of increased dynamic pressure, with an accompanying increase in local

$y/\delta _0 = 3.41$

) off the surface, where fluid is approximately 1.7 times the free-stream velocity. The interior of the slipstream can thus be identified as this region of increased dynamic pressure, with an accompanying increase in local

![]() $Re$

. The exact slipstream edge, however, is ambiguously defined, as the velocity gradient across it is continuous. We identify a band of maximum fluctuation through a time-averaged fluctuation kinetic energy

$Re$

. The exact slipstream edge, however, is ambiguously defined, as the velocity gradient across it is continuous. We identify a band of maximum fluctuation through a time-averaged fluctuation kinetic energy

The slipstream edge is then defined as lying within the

![]() $\overline {k}/U_\infty ^2 = 0.065$

isoline band, with the two isolines in figure 4(a) demarcating the outboard and inboard bounds of this band. The choice of

$\overline {k}/U_\infty ^2 = 0.065$

isoline band, with the two isolines in figure 4(a) demarcating the outboard and inboard bounds of this band. The choice of

![]() $\overline {k}/U_\infty ^2 = 0.065$

is through Gaussian fitting of the spanwise profiles of

$\overline {k}/U_\infty ^2 = 0.065$

is through Gaussian fitting of the spanwise profiles of

![]() $\overline {k}$

, which leads to the two isolines lying approximately one standard deviation away from the

$\overline {k}$

, which leads to the two isolines lying approximately one standard deviation away from the

![]() $z\hbox{-}$

location of each spanwise

$z\hbox{-}$

location of each spanwise

![]() $\overline {k}$

-profile peak. As a result, the selected band is representative of the largest fluctuations in the domain. The use of flow field fluctuation in the context of identifying the propeller slipstream boundary is also seen in Avallone et al. (Reference Avallone, Casalino and Ragni2018) and Sinnige et al. (Reference Sinnige, De Vries, Corte, Avallone, Ragni, Eitelberg and Veldhuis2018

a), although the fluctuating quantity used is the unsteady pressure coefficient.

$\overline {k}$

-profile peak. As a result, the selected band is representative of the largest fluctuations in the domain. The use of flow field fluctuation in the context of identifying the propeller slipstream boundary is also seen in Avallone et al. (Reference Avallone, Casalino and Ragni2018) and Sinnige et al. (Reference Sinnige, De Vries, Corte, Avallone, Ragni, Eitelberg and Veldhuis2018

a), although the fluctuating quantity used is the unsteady pressure coefficient.

Figure 4. Time-averaged

![]() $u$

-velocity slices of the flow field. Cyan, magenta lines indicate the respective positions of each slice plane. (a) Shows

$u$

-velocity slices of the flow field. Cyan, magenta lines indicate the respective positions of each slice plane. (a) Shows

![]() $y/R = 0.044$

. Thick black lines are the

$y/R = 0.044$

. Thick black lines are the

![]() $\overline {k}/U_\infty ^2=0.065$

band, thin black lines are in-plane streamlines. (b) Shows

$\overline {k}/U_\infty ^2=0.065$

band, thin black lines are in-plane streamlines. (b) Shows

![]() $z/R = 0.965$

. Dashed line is

$z/R = 0.965$

. Dashed line is

![]() $\overline {\delta _{99}}$

with estimation uncertainty indicated by the grey shaded region. (c) Shows

$\overline {\delta _{99}}$

with estimation uncertainty indicated by the grey shaded region. (c) Shows

![]() $x/R = 0.5$

. Black lines are

$x/R = 0.5$

. Black lines are

![]() $\overline {k}/U_\infty ^2=0.065$

band with in-plane velocity vectors.

$\overline {k}/U_\infty ^2=0.065$

band with in-plane velocity vectors.

The slipstream over the surface experiences positive spanwise deflection, as indicated by the mean streamlines and orientation of the edge isolines in figure 4. This is due to two primary mechanisms: an image vortex effect associated with the presence of the solid surface, and spanwise surface pressure gradients induced by the propeller–plate interaction. Both have been well established in previous works (Johnston & Sullivan Reference Johnston and Sullivan1993; Muscari et al. Reference Muscari, Dubbioso and Di Mascio2017; Sinnige Reference Sinnige2018). Additionally, the location of the slipstream edge in the domain is a function of the interaction at the plate LE (Felli Reference Felli2021) and the spacing between the propeller and plate, lying slightly inboard of the propeller-blade tip here. Figure 4b presents a streamwise–wall-normal slice of the slipstream at

![]() $z/R = 0.965$

. The relative orientation of the slice to the spanwise shearing effect results in the axial velocity gradient observed. It should be noted that, due to the 3-D nature of the flow field and arbitrary choice of coordinate system, this gradient is not indicative of streamwise fluid acceleration.

$z/R = 0.965$

. The relative orientation of the slice to the spanwise shearing effect results in the axial velocity gradient observed. It should be noted that, due to the 3-D nature of the flow field and arbitrary choice of coordinate system, this gradient is not indicative of streamwise fluid acceleration.

The mean swirl induced by the propeller within the slipstream is minimal in the measurement domain, as seen in a plane at

![]() $x/R = 0.5$

relative to the plate LE (figure 4

c). This could be attributed to vanishing inductions due to the propeller close to the blade tip in combination with the low advance ratio. It is apparent that the orientation of the vectors in figure 4(c) is in contrast to figure 2(b). This is once more due to the effect of the plate on the slipstream, and the resulting spanwise deflection discussed earlier. A mean vertical deflection of fluid is also observed on the outboard edge of the slipstream, far above the wall. Given the helical nature of the discrete tip-vortex system and the positioning of the measurements on the downgoing side of the propeller blades, this aligns with the expected mean induced velocities in this region. Additionally, there is a local variation in BL thickness in the spanwise direction around the slipstream edge, which is further discussed in the following section.

$x/R = 0.5$

relative to the plate LE (figure 4

c). This could be attributed to vanishing inductions due to the propeller close to the blade tip in combination with the low advance ratio. It is apparent that the orientation of the vectors in figure 4(c) is in contrast to figure 2(b). This is once more due to the effect of the plate on the slipstream, and the resulting spanwise deflection discussed earlier. A mean vertical deflection of fluid is also observed on the outboard edge of the slipstream, far above the wall. Given the helical nature of the discrete tip-vortex system and the positioning of the measurements on the downgoing side of the propeller blades, this aligns with the expected mean induced velocities in this region. Additionally, there is a local variation in BL thickness in the spanwise direction around the slipstream edge, which is further discussed in the following section.

4.3. Boundary-layer modulation

The discrete vortical system comprising the propeller slipstream induces unsteady pressure fluctuations over the plate surface. In a time-averaged sense, this changes the steady loading experienced by the developing BL. Figure 5 presents the averaged static pressure coefficient (

![]() $c_p = 2(p - p_\infty )/\rho _\infty U_\infty ^2$

) distribution measured from the two arrays of pressure taps, indicative of the change in loading between the propeller-off and propeller-on cases. The reference pressure

$c_p = 2(p - p_\infty )/\rho _\infty U_\infty ^2$

) distribution measured from the two arrays of pressure taps, indicative of the change in loading between the propeller-off and propeller-on cases. The reference pressure

![]() $p_\infty$

here is the ambient pressure outside of the open-jet flow. In the absence of a slipstream, the TBL flow continues to accelerate beyond the trip location to attain a mild suction peak at

$p_\infty$

here is the ambient pressure outside of the open-jet flow. In the absence of a slipstream, the TBL flow continues to accelerate beyond the trip location to attain a mild suction peak at

![]() $x/R \sim 0.28$

, before starting to relax into a zero-pressure-gradient flow. The TBL flow in the PIV measurement domain is hence exposed to a very low adverse pressure gradient (APG). With the propeller on, the solid

$x/R \sim 0.28$

, before starting to relax into a zero-pressure-gradient flow. The TBL flow in the PIV measurement domain is hence exposed to a very low adverse pressure gradient (APG). With the propeller on, the solid

![]() $c_p$

curves in figure 5 exhibit higher

$c_p$

curves in figure 5 exhibit higher

![]() $c_p$

values overall. This due to the slipstream-induced change in loading experienced by the plate (Veldhuis Reference Veldhuis2005). The section immersed in the slipstream at

$c_p$

values overall. This due to the slipstream-induced change in loading experienced by the plate (Veldhuis Reference Veldhuis2005). The section immersed in the slipstream at

![]() $r/R = 0.7$

(

$r/R = 0.7$

(

![]() $\square$

) experiences a swirl-induced negative angle of attack, with the

$\square$

) experiences a swirl-induced negative angle of attack, with the

![]() $c_p$

distribution exhibiting a strong FPG up to

$c_p$

distribution exhibiting a strong FPG up to

![]() $x/R = 0.4$

. It should also be noted that there is increased total pressure within the slipstream which provides a positive offset to the

$x/R = 0.4$

. It should also be noted that there is increased total pressure within the slipstream which provides a positive offset to the

![]() $c_p$

distribution measured here. The FPG at

$c_p$

distribution measured here. The FPG at

![]() $z/R = 1.3$

(

$z/R = 1.3$

(

![]() $\circ$

), external to the slipstream, is much milder in comparison. This is due to lower-amplitude secondary inductions caused by the spanwise loading gradient at the slipstream edge (Sinnige Reference Sinnige2018; Veldhuis Reference Veldhuis2005).

$\circ$

), external to the slipstream, is much milder in comparison. This is due to lower-amplitude secondary inductions caused by the spanwise loading gradient at the slipstream edge (Sinnige Reference Sinnige2018; Veldhuis Reference Veldhuis2005).

Figure 5. (a) Pressure coefficient distributions for the propeller-on (solid black lines) and off (dotted black lines) cases, with uncertainty represented by the grey shaded regions. Leading-edge geometry is shown as the solid grey line. Shaded green area indicates the PIV measurement domain for the plate-on measurements.

Figure 6. (a) Relative change in TBL thickness with

![]() $\overline {U_e}$

vectors (grey). Solid black lines are the

$\overline {U_e}$

vectors (grey). Solid black lines are the

![]() $\overline {k}/U_\infty ^2 = 0.065$

band, dashed lines are where BL velocity profiles are shown,

$\overline {k}/U_\infty ^2 = 0.065$

band, dashed lines are where BL velocity profiles are shown,

![]() $z/R = 1.00$

(magenta),

$z/R = 1.00$

(magenta),

![]() $z/R = 0.95$

(black),

$z/R = 0.95$

(black),

![]() $z/R = 0.92$

(cyan). (b) Streamwise (

$z/R = 0.92$

(cyan). (b) Streamwise (

![]() $\circ$

) and cross-flow (

$\circ$

) and cross-flow (

![]() $\square$

, scaled by a factor of 5 for visualisation) velocity profiles.

$\square$

, scaled by a factor of 5 for visualisation) velocity profiles.

A relative change in the time-averaged TBL thickness

![]() $\overline {\delta _{99}}$

between the propeller-off and propeller-on cases is used as a global estimator to quantify BL modulation caused by the slipstream, within the measurement domain. This is computed using the criterion described in § 2.1.1 for each spanwise PIV measurement plane in the domain and presented in Figure 6(a). There is observed to be a local thickening of the TBL in a band roughly centred around the slipstream edge, within an amplitude range of

$\overline {\delta _{99}}$

between the propeller-off and propeller-on cases is used as a global estimator to quantify BL modulation caused by the slipstream, within the measurement domain. This is computed using the criterion described in § 2.1.1 for each spanwise PIV measurement plane in the domain and presented in Figure 6(a). There is observed to be a local thickening of the TBL in a band roughly centred around the slipstream edge, within an amplitude range of

![]() $1.2 {-} 1.5$

times the propeller-off

$1.2 {-} 1.5$

times the propeller-off

![]() $\overline {\delta _{99}}$

. On the contrary, the increase in local

$\overline {\delta _{99}}$

. On the contrary, the increase in local

![]() $Re$

within the slipstream due to increased dynamic pressure as well as the strengthened FPGs on the downgoing blade side would indicate an overall decrease in BL thickness. The observed change in

$Re$

within the slipstream due to increased dynamic pressure as well as the strengthened FPGs on the downgoing blade side would indicate an overall decrease in BL thickness. The observed change in

![]() $\overline {\delta _{99}}$

is thus attributed to the unsteady passage of the propeller tip vortices within the

$\overline {\delta _{99}}$

is thus attributed to the unsteady passage of the propeller tip vortices within the

![]() $\overline {k}/U_\infty ^2 = 0.065$

band. Here, the maximum variation in relative

$\overline {k}/U_\infty ^2 = 0.065$

band. Here, the maximum variation in relative

![]() $\overline {\delta _{99}}$

change is observed to be on the outboard side of this band, where the unsteady vortical inductions oppose the free stream. Boundary-layer thickening is also noted to occur on the inboard side of the slipstream edge, where the vortical inductions accelerate the free-stream fluid. The relative

$\overline {\delta _{99}}$

change is observed to be on the outboard side of this band, where the unsteady vortical inductions oppose the free stream. Boundary-layer thickening is also noted to occur on the inboard side of the slipstream edge, where the vortical inductions accelerate the free-stream fluid. The relative

![]() $\overline {\delta _{99}}$

increase within the slipstream decays at more inboard sections with BL thinning observed at the farthest inboard point in figure 6(a), as would be expected. The origins of the local time-averaged thickening of the BL around the

$\overline {\delta _{99}}$

increase within the slipstream decays at more inboard sections with BL thinning observed at the farthest inboard point in figure 6(a), as would be expected. The origins of the local time-averaged thickening of the BL around the

![]() $\overline {k}/U_\infty ^2 = 0.065$

isolines in figure 6(a) are further discussed in § 5 from the unsteady point of view.

$\overline {k}/U_\infty ^2 = 0.065$

isolines in figure 6(a) are further discussed in § 5 from the unsteady point of view.

The TBL also exhibits strong three-dimensionality in the mean flow, owing to the inherently 3-D nature of the external flow imposed by the slipstream. This can be seen in figure 6(a) where the vectors represent the local in-plane external velocity at the edge of the BL. The positive deflection of the slipstream induces a mean spanwise flow into the BL throughout the measurement domain. The full effect of this can be seen by decomposing the 3-D BL profiles into streamwise and cross-flow velocity profiles (figure 6

b) based on the local

![]() $\overline {U_e}$

vectors. There is a non-zero component of cross-flow for all extracted profiles, largest at the most inboard location within the domain. This corresponds to the increased shearing effect of the slipstream at more inboard locations, as can be seen with the vectors in figure 6(a).

$\overline {U_e}$

vectors. There is a non-zero component of cross-flow for all extracted profiles, largest at the most inboard location within the domain. This corresponds to the increased shearing effect of the slipstream at more inboard locations, as can be seen with the vectors in figure 6(a).

5. Phase-locked flow topology

This section presents an analysis of the unsteady features of the tip-vortex–TBL interaction, through phase-locked measurements of the flow field. Additionally, the volumetric reconstruction described in § 2 enables the identification of coherent, periodic structures pertinent to the unsteady passage of the propeller tip vortices through the measurement domain.

5.1. Three-dimensional vortical structures

Coherent vortical structures are visualised using the normalised

![]() $Q$

-criterion (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Wray and Moin1988; Mula et al. Reference Mula, Stephenson, Tinney and Sirohi2013), where

$Q$

-criterion (Hunt et al. Reference Hunt, Wray and Moin1988; Mula et al. Reference Mula, Stephenson, Tinney and Sirohi2013), where

isolating rotationally dominant regions of fluid. As shown in figure 7, isosurfaces of the

![]() $Q$

-criterion at a fixed rotation phase

$Q$

-criterion at a fixed rotation phase

![]() $\phi = 80^\circ$

reveal a distinct, well-organised tip-vortex system located in the

$\phi = 80^\circ$

reveal a distinct, well-organised tip-vortex system located in the

![]() $z/R = 0.9 {-} 1$

vicinity. This system comprises a double-vortex structure, with the two component features labelled the primary and secondary vortices for the remainder of this discussion. As the TBL flow is resolved up to approximately 0.5

$z/R = 0.9 {-} 1$

vicinity. This system comprises a double-vortex structure, with the two component features labelled the primary and secondary vortices for the remainder of this discussion. As the TBL flow is resolved up to approximately 0.5

![]() $\overline {\delta _{99}}$

in the vicinity of this vortex system, only the outer-region TBL interaction is captured.

$\overline {\delta _{99}}$

in the vicinity of this vortex system, only the outer-region TBL interaction is captured.

Figure 7. Isosurfaces of vortex core regions for

![]() $QR^2/U_\infty ^2 = 24$

(dark grey),

$QR^2/U_\infty ^2 = 24$

(dark grey),

![]() $1200$

(black) from phase-locked velocity fields at

$1200$

(black) from phase-locked velocity fields at

![]() $\phi = 80^\circ$

. White vectors represent local vorticity vectors on the

$\phi = 80^\circ$

. White vectors represent local vorticity vectors on the

![]() $QR^2/U_\infty ^2 = 24$

isosurface. Surface slices are

$QR^2/U_\infty ^2 = 24$

isosurface. Surface slices are

![]() $\overline {u}^{\textrm {PL}}/U_\infty$

and black lines are streamlines, both at

$\overline {u}^{\textrm {PL}}/U_\infty$

and black lines are streamlines, both at

![]() $y/\delta _0 = 0.72$

. Magenta and cyan lines respectively indicate the outboard (I) and inboard (II)

$y/\delta _0 = 0.72$

. Magenta and cyan lines respectively indicate the outboard (I) and inboard (II)

![]() $z$

-locations discussed in § 5.2. (a) Inboard side, downstream view. (b) Outboard side, upstream view.

$z$

-locations discussed in § 5.2. (a) Inboard side, downstream view. (b) Outboard side, upstream view.

The primary vortex structure exhibits a 3-D character largely focused in the wall-normal

![]() $y$

-direction, associated with the impinging propeller tip vortex. The spatial organisation of the

$y$

-direction, associated with the impinging propeller tip vortex. The spatial organisation of the

![]() $QR^2/U_\infty ^2 = 1200$

isosurface with respect to the wall-normal component of the

$QR^2/U_\infty ^2 = 1200$

isosurface with respect to the wall-normal component of the

![]() $QR^2/U_\infty ^2 = 24$

surface indicates that both structures comprise the primary vortex, with the former representing a strongly rotational core region of the tip vortex. Away from the wall, the primary vortex displays a negative inclination in the spanwise (

$QR^2/U_\infty ^2 = 24$

surface indicates that both structures comprise the primary vortex, with the former representing a strongly rotational core region of the tip vortex. Away from the wall, the primary vortex displays a negative inclination in the spanwise (

![]() $z$

) direction and a positive axial (

$z$

) direction and a positive axial (

![]() $x$

) tilt, consistent with a helical organisation of discrete vorticity in the propeller slipstream. In the near-wall region, the axial inclination of the vortex increases in the positive

$x$

) tilt, consistent with a helical organisation of discrete vorticity in the propeller slipstream. In the near-wall region, the axial inclination of the vortex increases in the positive

![]() $x$

-direction and the inner core exhibits contraction. This shift in orientation near the wall can stem from two sources: first, the interaction between the impinging vorticity and the LE of the plate. Second, viscous shear of the BL flow exerted on the tip-vortex core. With regard to the former, Felli (Reference Felli2021) and Thom (Reference Thom2011) have indicated that the ratio of LE-to-vortex core size can strongly influence the extent of vortex wrapping around the plate LE, with the ratio here estimated to be near unity. This would correlate to the mild axial deformation of the tip vortex observed in figure 7, although the full development from the point of impingement is not resolved here.

$x$

-direction and the inner core exhibits contraction. This shift in orientation near the wall can stem from two sources: first, the interaction between the impinging vorticity and the LE of the plate. Second, viscous shear of the BL flow exerted on the tip-vortex core. With regard to the former, Felli (Reference Felli2021) and Thom (Reference Thom2011) have indicated that the ratio of LE-to-vortex core size can strongly influence the extent of vortex wrapping around the plate LE, with the ratio here estimated to be near unity. This would correlate to the mild axial deformation of the tip vortex observed in figure 7, although the full development from the point of impingement is not resolved here.

The secondary vortex structure is observed to emerge from within the TBL and wraps around the primary vortex as it progresses downstream (figure 8). This secondary structure is characterised by its proximity to the wall and its eventual convergence with the primary vortex. Near the wall, the secondary vortex exhibits predominantly axial and spanwise vorticity components, consistent with its origin in the BL. As it convects upward and outward, the structure becomes more fully three-dimensional, indicating entrainment and roll-up by and into the primary vortex. This process is elucidated by the surface vorticity vectors in figure 7. This wrapping and merging process appears to intensify over the passage of the tip vortex through the measurement domain, with the secondary vortex growing and progressing away from the wall at more downstream locations (figure 8).

Figure 8. Isosurfaces of vortex core regions at phases

![]() $\phi = 0^\circ , 40^\circ , 80^\circ$

. See figure 7 caption for colours. Surface slices are wall-normal velocity

$\phi = 0^\circ , 40^\circ , 80^\circ$

. See figure 7 caption for colours. Surface slices are wall-normal velocity

![]() $\overline {v}^{\textrm {PL}}/U_{\infty }$

and black lines are streamlines, both at

$\overline {v}^{\textrm {PL}}/U_{\infty }$

and black lines are streamlines, both at

![]() $y/\delta _0 = 0.72$

. Left column: outboard side, downstream view. Right column: inboard side, upstream view.

$y/\delta _0 = 0.72$

. Left column: outboard side, downstream view. Right column: inboard side, upstream view.

We postulate that the genesis of the secondary vortex is driven by the forcing introduced by the primary vortex on the BL. A velocity deficit region of approximately 60 % the free-stream velocity is observed on the outboard side of the vortex (region I in figure 7), aligned with the direction of induced velocities due to the primary wall-normal vorticity in this region. Conversely, the inboard side of the vortex (region II in figure 7) corresponds to a region of accelerated flow, with the flow locally reaching 1.8

![]() $U_\infty$

. These regions of locally decelerated and accelerated flow are associated with strong local velocity gradients, causing a local amplification of BL vorticity. Additionally, the BL undergoes spanwise deflection in the vicinity of the primary vortex, illustrated by the streamlines in figures 7 and 8. The resulting spanwise gradients, in combination with the amplified BL vorticity, facilitate the development of the secondary vortex structure which couples with the primary vortex to feed back into the overall 3-D interaction. This viscous–inviscid coupling mechanism has been similarly detailed by Didden & Ho (Reference Didden and Ho1985) for 2-D vortex–BL interaction. The relative contributions of each vortex structure to the BL response are difficult to isolate, due to their overlapping and mutual inductions. A deeper analysis of the dynamics of this 3-D interaction is carried out in the following section.

$U_\infty$

. These regions of locally decelerated and accelerated flow are associated with strong local velocity gradients, causing a local amplification of BL vorticity. Additionally, the BL undergoes spanwise deflection in the vicinity of the primary vortex, illustrated by the streamlines in figures 7 and 8. The resulting spanwise gradients, in combination with the amplified BL vorticity, facilitate the development of the secondary vortex structure which couples with the primary vortex to feed back into the overall 3-D interaction. This viscous–inviscid coupling mechanism has been similarly detailed by Didden & Ho (Reference Didden and Ho1985) for 2-D vortex–BL interaction. The relative contributions of each vortex structure to the BL response are difficult to isolate, due to their overlapping and mutual inductions. A deeper analysis of the dynamics of this 3-D interaction is carried out in the following section.

5.2. Dynamics of boundary-layer response

The BL response to the tip-vortex structures reveals two distinct regimes of interaction, corresponding to the outboard (region I, figure 7) and inboard (region II, figure 7) regions relative to the primary vortex core. Similar near-wall flow topology is observed at varying spanwise distance from the tip-vortex cores, within each of these respective regions. This dual-regime behaviour underscores the inherently asymmetric, 3-D nature of the BL modulation induced by the 3-D vortex system.

In the outboard region the TBL exhibits localised axial velocity deficits (figure 7