Overview

The objective of this study is to conduct an exploratory analysis of the power of policy narrators in communicating policy guidance to their audience. We rely on the Narrative Policy Framework (NPF; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Smith-Walter, McBeth, Shanahan and Weible2023) as our theoretical basis, because the NPF, whose main objective is to capture how policy narratives shape the policy process, has validated narrative constructs. Whereas much of NPF scholarship has focused on the narrative concepts housed in narrative form (e.g., characters, setting, plot) and content (e.g., strategic use of narrative form, policy beliefs) (McBeth, Jones, and Shanahan Reference McBeth, Jones, Shanahan, Sabatier and Weible2014; Jones, McBeth, and Shanahan Reference Jones, McBeth, Shanahan, Jones, Shanahan and McBeth2014; Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, McBeth, Radaelli, Weible and Sabatier2018; Jones et al. Reference Jones, McBeth, Shanahan, Smith-Walter, Song, Weible and Workman2022; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Smith-Walter, McBeth, Shanahan and Weible2023), narrative concepts also exist in a larger narrative environment, beyond the NPF’s narrative form or content, such as the narrator (Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, DeLeo, Koebele, Taylor, Crow, Blanch-Hartigan, Albright, Birkland and Minkowitz2025). This study contributes to the NPF by (i) theorizing the role, definition, and operationalization of the narrator and offering an empirical illustration and (ii) systematically assessing the relative effect of different types of narrators through the use of an embedded survey experiment. In this paper, we advance understanding of the narrator as a narrative element, thereby finding support for broadening the NPF’s enumeration of narrative elements.

Despite the potential for narrator influence on the audience (e.g., motivation, perceptions, behaviors) and the need to understand the effects more clearly, the role of the narrator in communicating policy and in the NPF is explicitly largely undertheorized. We begin by detailing the narrator’s definition, features, and function. We assert that studies of the influence of narrators must be anchored to theory, similar to how NPF requires the examination of policy beliefs to be grounded in theory (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Smith-Walter, McBeth, Shanahan and Weible2023, 166). As such, we begin by describing the theory we use to ground the narrator feature of psychological distance to the audience to examine the effectiveness of proximal (friend as narrator) versus more distal experts (your doctor, the CDC as narrators) in motivation to get the COVID-19 vaccine. We then proceed to detail the experimental design, hypotheses, methods, and analysis used for our models. We describe the results of our exploratory study by hypothesis and then offer a discussion of these results in the context of furthering studies of the narrator as a narrative element.

The features and function of the narrator

Consistent with the original building blocks of the NPF (Jones and McBeth Reference Jones and McBeth2010), we rely on narratology, the study of the form and function of narrative (Prince Reference Prince1982), to describe the role of the narrator. Specifically, we discuss how the definition, features, and functions of a narrator in literature and film inform the conceptualization and theorizing around the role of narrator of a policy narrative. By definition, the narrator is the one to tell the story (de Jong Reference de Jong, de Jong, Nünlist and Bowie2004). By extension, for the NPF, the narrator is the one who tells the policy story or constructs the policy reality (Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, McBeth and Lane2013). However, for narratologists, such as Chatman (Reference Chatman1978), there is general agreement that the role of the author is distinct from that of the narrator, since the narrator is a creation of the author in fictional works. For example, Huck Finn, Scout Finch, and the Iliad’s Muse are story narrators who are characters separate from the respective authors’ perspective or commentary through these literary works.

For the NPF, this narrator–author distinction is less applicable to the conceptualization of narrators of policy narratives. Given the underlying assumption of social construction in the NPF (Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Jones, McBeth and Lane2013), it is entirely possible for a narrative to have multiple narrators. Policy narratives argue for a distinct policy preference, and they are delivered by author(s) who strategically craft the narrative argument. As such, the identity of the author and narrator are often the same for policy narratives. However, there are cases, such as media accounts, in which an author of a policy narrative may be distinct from in-text narrator characters. Consider, for example, a journalist’s account of a press conference in which a governor is encouraging the public to install solar panels on their homes. A coalition of policy actors–legislators, interest groups, subject matter experts–author a policy narrative to advance a policy preference. The governor, as narrator, communicates that narrative to the assembled press. A journalist may write the narrative, but the governor is the narrator communicating the story that has been written by a separate author, communicating policy preference. Another example might be media coverage of the President of the United States’ State of the Union Address to Congress. The journalists in the media are writing the narrative but the President is the narrator, telling the story of a preferred policy outcome in an attempt to persuade lawmakers. These examples are simplifications meant to convey both the distinction between the author and narrator and the potential avenues for there to be multiple authors of one narrative. On the whole, we are in alignment with the narratology definition of narrator, and we retain the possibility of the narrator and author as being distinct.

One often-cited feature of the narrator is that of the distinction between overt-covert narrators (Chatman Reference Chatman1978) or internal-external narrators (de Jong Reference de Jong, de Jong, Nünlist and Bowie2004). An overt or internal narrator is featured as a character in the story, whereas a covert or external narrator is passively or not explicitly featured. This feature reflects the narrator’s involvement in the story, with the former engaging the audience, and the latter more or less neutral. Often, this is translated by what is called point of view or the perspective from which the story is told (Phelan and Booth Reference Phelan, Booth, Herman, Manfred and Ryan2005). An internal narrator uses first person or “I” or “we” to tell a story and is a character in the narrative who shares their own policy reality (beliefs, perspective, statements) of the policy issue. By contrast, an external narrator is one where the narrator uses the third-person point of view or “he,” “she,” or “they” to present a policy reality. While no NPF research has explored the power of overt/internal versus covert/external policy narrators, health researchers have found first person accounts to be more persuasive than the third person in influencing health decisions (Chen and Bell Reference Chen and Bell2022). Additional narrator features include demographic characteristics such as gender identity (Witus and Larson Reference Witus and Larson2022), age (Oakes and North Reference Oakes and North2011), political affiliation, cultural background, or profession (Faour-Klingbeil et al. Reference Faour-Klingbeil, Osaili, Al-Nabulsi, Jemni and Todd2021), and values/beliefs, communication skills (e.g., charisma; Engelbert et al. Reference Engelbert, van Elk, Kandrik, Theeuwes and van Vugt2023) would advance the understanding of the power of the narrator as a narrative element. In sum, NPF research on narrators can be advanced by considering narrator features identified in adjacent literatures.

Narratology describes the function of the narrator as critical to how compelling the content is to the audience. In narratological studies, assessments of how narrators function are often analyzed in terms of narrator reliability or unreliability (Booth Reference Booth1983). An unreliable narrator misleads the audience, either knowingly or unwittingly. The reliability of the narrator was originally thought to be assigned by the author, who narratologists consider to be separate from the narrator. However, more recent theorizing considers the audience’s role in making the judgment or interpretation of the reliability of the narrator (Nünning Reference Nünning and Nünning2015). For the NPF, the adjacent concept to narrator reliability/unreliability is narrator trust, which is predicated on the audience finding credibility in the narrators. Thus, for the NPF, narrator trust is not wholly or even partially imparted by an author, but, rather, sits squarely in the possession of the audience. The NPF’s narrator trust hypothesis posits that narrative persuasiveness is positively associated with the audience’s trust in the narrator (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Smith-Walter, McBeth, Shanahan and Weible2023, 172). NPF studies on the role of the narrator (e.g., Costie and Olofsson Reference Costie and Olofsson2022; Hand, Megan, and Rai Reference Hand, Megan and Rai2023; Ertas Reference Ertas2015; Lybecker, McBeth, and Sargent Reference Lybecker, McBeth, Sargent, Jones, McBeth and Shanahan2022) embody mixed results regarding narrator influence. These mixed results may be due to variation in study designs, as some include the interaction of congruent policy beliefs in narrative content while others isolate narrator effects.

It is important to note the underlying purpose of the features and function of the narrator: to influence policymakers, elites, and the public to promote a preferred policy outcome. Policy narratives are strategically crafted to achieve a political end, meaning that political gamesmanship is important. Framing policy narratives and competing narratives is one tool to exert power in political discourse (Lukes Reference Lukes2021). In the context of political rhetoric, authors of a policy narrative have to tell the story of the narrative but also defend it in the face of political competition (Riker Reference Riker, Calvert, Mueller and Wilson1996). This is particularly true of highly-contested policy issues that result in framing contests among competing coalitions who are trying to advance a policy issue (Yordy et al. Reference Yordy, You, Park, Weible and Heikkila2019). In the context of the COVID-19 vaccinations, the features and function of the narrator are important because of their framing ability and their use of power to persuade their audience for a preferred policy outcome.

Psychological proximity as theory for narrator influence

All narrators are not created equal in terms of their potential to influence audience beliefs, opinions, or behavior. The feature(s) a narrator embodies is(are) likely to have varied effects on audiences. In this study, we sought to test the narrator feature of psychological distance from the audience, grounded in psychological studies that find the degree to which individuals construe or interpret something in the abstract versus concrete can determine how they perceive various phenomena. Construal Level Theory (CLT) is the scaffolding for studies of psychological distance, with high-construal or distal events interpreted abstractly (e.g., a healthy diet prevents heart disease) and low-construal or proximal events understood concretely (e.g., I will buy vegetables for tonight’s dinner) (Trope and Liberman Reference Trope and Liberman2010). Fiedler et al. (Reference Fiedler, Jung, Wänke and Alexopoulos2012) argue that “with increasing distance of the beholder, mental representations of the world are expected to become increasingly abstract, simplified, and idealized. As distance decreases, conversely, mental representations become more concrete, complex, and situated.”

Psychological distance has multiple dimensions, such as time (distal future is more abstract than proximal present), space (a distal country is typically more abstract than a proximal hometown), or relational (a distal leader is more removed than proximal friends). High construal or distal features are found to be more effective in long-term goal setting such as healthcare policy (Trope and Liberman Reference Trope and Liberman2003), whereas low construal or proximal features are found to be more effective on immediate action or compliance, such as getting a COVID-19 vaccine (Hansen and Wänke Reference Hansen and Wänke2010). As greater psychological proximity is introduced in narratives, individuals are better able to understand the potential risks and facets of a problem and are better positioned to respond to calls for individual action. For example, when presented with messages about climate change, individuals are significantly more likely to support climate mitigation measures when those messages are more proximate and catalyze concrete and specific mental images of climate change effects (Chu Reference Chu2022). “Psychological distance is thus egocentric: Its reference point is the self,” thereby determining how people imagine the world around them (Trope and Liberman Reference Trope and Liberman2010).

One of the most important pathways through which psychological proximity shapes individual health behaviors is by bolstering--or undermining--trustworthiness. Sungur et al. (Reference Sungur, Hartmann and van Koningsbruggen2016), for example, find that congruency between individual mindsets and perceived psychological distance are positively associated with perceived trustworthiness--more specifically, the “believability”--of online resources. More precisely, psychological distance effectively serves as a heuristic for quickly evaluating the likely credibility of information presented online. Franke and Groeppel-Klein (Reference Franke and Groeppel-Klein2024) echo these findings in their study of the effectiveness of human-like versus cartoon-like virtual influencers. Their novel experimental design shows that not only is the psychological distance between cartoon-like influencers greater in comparison to the human-like influencers, but that greater distance is associated with decreased trustworthiness. Other research has demonstrated a strong connection between proximity and concepts closely linked to trust, like emotional connectedness (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Hon and Won2018).

Thus, our study explores whether the construal level of narrator features influences the audience’s individual motivation to get the COVID-19 vaccine. We assert the same proximal to distal effects attached to events can also be applied to narrators themselves. Specifically, each narrator is imbued with characteristics/features that make them more or less proximal to the audience with which they are communicating. Within the context of a public health crises, like the COVID-19 pandemic, the narrator’s positionality within the larger public health/healthcare information ecosystem, which can range from high-level bureaucratic institutions (distal) to a friend or loved one who provides medical opinions or thoughts (proximal), is a useful proxy for precisely the types of relational proximal-distal features highlighted in CLT. However, narrators as a narrative element do not operate in a vacuum; they exist in a narrative context as well. Spatial psychological distance in a narrative may occur in a setting (country vs community) or in other elements such as characters (proximal to distal victims). Thus, we explore whether congruence between narrator features of relational proximity-distance in tandem with spatial proximity-distance have an effect on audience behavior. In sum, a narrator’s policy prescriptions must be communicated through narratives that can either serve to accentuate or undermine the relative narrator influence depending on the other elements in the narrative (e.g., form and content) and audience trust in the narrator.

Hypotheses

Drawing from the literature on the role of the narrator and psychological proximity/distance, we posit three hypotheses.

Proximity hypothesis. In comparison to the control, the most relationally proximal narrator (“your friend”) will have significant positive total effects on motivation to get the COVID-19 vaccine, across all levels of narrative content, from spatially proximal to distal.

Congruence hypothesis. In comparison to the control, there is a significant effect of the narrator whose relational distance is congruent with the spatial distance of the narrative content or the victim portrayed. In our experimental survey design, we examine the relationship between spatial distance in narrative content of who is cast as the victim to be protected by the audience (proximal “yourself” to intermediate “your circle” to distal “your community”) with relational distance in narrators (proximal “your friend” to intermediate “your doctor” to distal “the CDC”). We anticipate the proximal psychological distance that is congruent between “your friend” and “protect yourself” to have the greatest effect, given previous studies’ findings that individual actions are most affected by more personal or lower construal levels. However, we explore the effects for each congruent pairing.

-

In the “protect yourself” visual policy narrative, the narrator “your friend” will have significant positive total effects on motivation to get the COVID-19 vaccine in comparison to the control.

-

In the “protect your circle” visual policy narrative, the narrator “your doctor” will have significant positive total effects on motivation to get the COVID-19 vaccine in comparison to the control.

-

In the “protect your community” visual policy narrative, the narrator ‘the CDC’ will have significant positive total effects on motivation to get the COVID-19 vaccine in comparison to the control.

-

In the “get the vaccine” visual message, the control condition “someone” will have significant positive total effects on motivation to get the COVID-19 vaccine in comparison to the control.

Narrator trust hypothesis. The higher the trust of the narrator as a source of information, the higher the total effects of the narrator on motivation to get the COVID-19 vaccine, in comparison to the control.

Research design

This study is built on a previous survey experiment whereby we tested the influence of visual policy narratives on COVID-19 vaccine motivation and uptake (Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Li, DeLeo, Alright, Koebele, Taylor, Crow, Birkland, Dickinson, Minkowitz and Zhang2023). Because we know from repeated studies that the hero is effective in shaping attitudes, affective responses, and behaviors (e.g., Jones Reference Jones, McBeth, Shanahan, Jones, Shanahan and McBeth2014; Raile et al. Reference Raile, Shanahan, Ready, McEvoy, Izurieta, Reinhold, Poole, Bergmann and King2022; Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Reinhold, Raile, Poole, Ready, Izurieta, McEvoy, Bergmann and King2019), we constructed the visual policy narrative experimental conditions to hold constant the hero (the audience who ‘protects’) and moral/solution (‘get the COVID-19 vaccine’), and to vary the less studied character of victim. We identified victim characters by using the spatial dimension of psychological distance: proximal (“protect yourself”) to intermediate (“protect your circle”) to distal (“protect your community”) (Table 1; Shanahan et al., Reference Shanahan, Li, DeLeo, Alright, Koebele, Taylor, Crow, Birkland, Dickinson, Minkowitz and Zhang2023). We chose the three levels of spatial distance to represent the individual to collective continuum that is often the values that drives behavior choices (Chen and Unal Reference Chen and Unal2023), given the growing polarization over the COVID-19 vaccine at the time (Paul, Eberl, and Partheymüller Reference Paul, Eberl and Partheymüller2021). To our surprise, in this prior study, we found the intermediate and distal narrative content (who was cast as the victim) to be more effective than the proximal content at individual vaccine motivation and adoption.

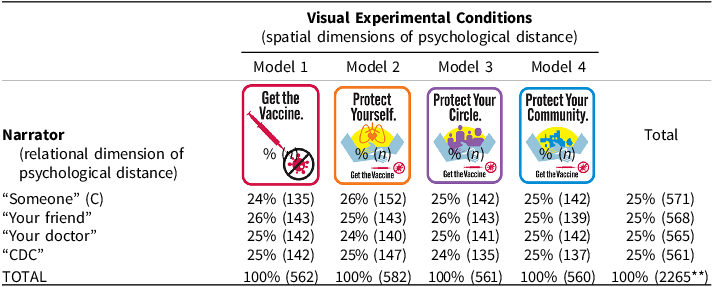

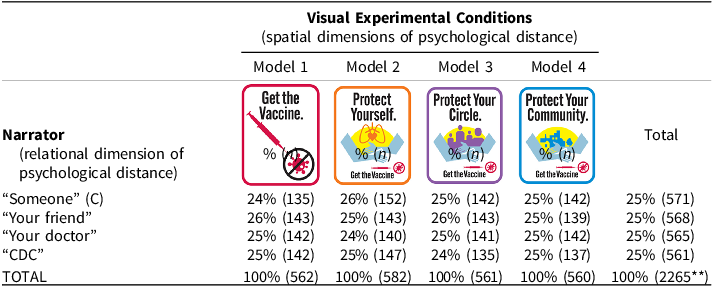

Table 1. Experimental design: visual experimental conditions by narrator

*C = control

** The difference between the total participants in all four experimental groups (2265) and total participants in T2 (2268) is due to 3 participants not completing the experimental part of the survey.

In this study, we further developed our inquiry using the relational dimension of psychological distance by affixing one of three narrators (“your friend”, “your doctor”, or “the CDC”) or a control condition (“someone”) to the same visual policy narrative treatments that respondents had received in a previous wave of the survey. As such, we test the power of the proximal to distal narrator for each experimental condition, based upon the expectations that CLT offers, thereby holding the content of the policy narrative constant.

We paired relational features of the narrators to each level spatial distance: “your friend” with “yourself”; “your doctor” with “your circle;” and “the CDC” with “your community.” Our rationale was to match proximities across relational and spatial dimensions of CTL, thinking primarily from the perspective of the respondent. We chose “the CDC” to be paired with “your community” (e.g., people who share a geographic proximity to the respondent, but people who the audience may not know), given the prolific presence of the CDC in messaging “We are in this together.” We chose to pair “your doctor” with “your circle” (e.g., people who the respondent knows such as teachers or your neighbor, but who are not necessary friends). Finally, we chose to pair “your friend” with “yourself,” given (in part) that not all people have positive relationships with family members and someone the respondent would call a friend would inherently be believable.

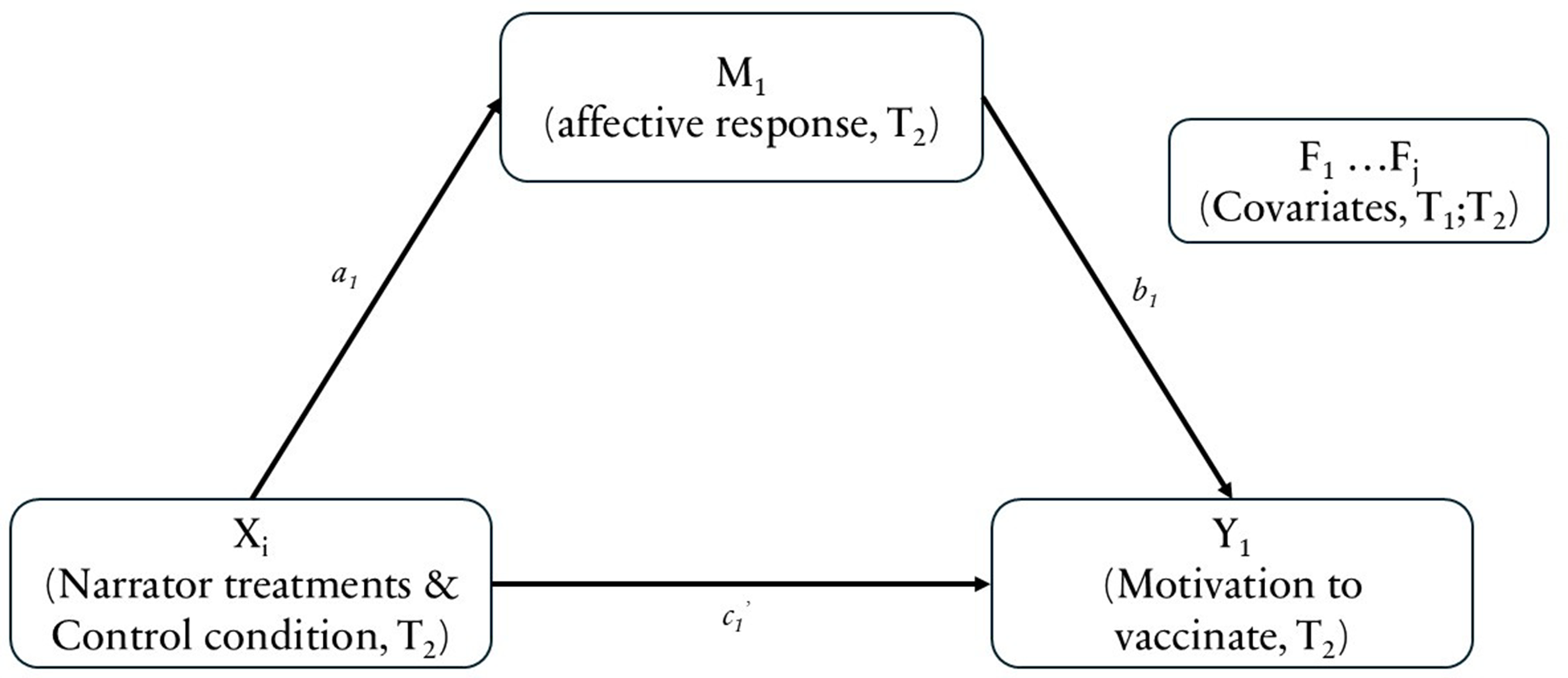

As with multiple NPF studies (e.g., Shanahan et al. Reference Shanahan, Reinhold, Raile, Poole, Ready, Izurieta, McEvoy, Bergmann and King2019), we also account for the mediating effects of affective response to the narrator on motivation to get the COVID-19 vaccine (Figure 1). Fludernik (Reference Fludernik2009, 27) describes the main purpose of a narrator is to activate an affective response (e.g., sympathy, antipathy) for certain characters. Given the NPF’s narrator hypothesis and the extensive scholarship surrounding the import of reliability or credibility of narrators, we assess the extent to which the respondent trusts the narrator as a covariate (amongst other demographic, beliefs, and behavior covariates detailed in Supplement A). By grounding our narrator choice in psychological distance theory and accounting for affective response to and trust of the narrator, we offer a novel way to understand the influence of the narrator (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual figure of mechanisms of narrative effects on motivation to vaccinate.

Methods

Our research team constructed a three-wave panel survey of individuals in 50 U.S. states and Washington D.C. in 2021, with QualtricsXM supplying panel participants and survey administration. The survey study was approved by Bentley University’s Institutional Review Board (Exempt #10202024) to adhere to ethical standards described in the Belmont Report. In this study, if a respondent reported getting the COVID-19 vaccine, we did not ask if they intended to get the vaccine; thus, we limited our testing to Wave 2 data for intention results. Given the well-documented disparities in COVID-19’s vaccine uptake (Reitsma et al. Reference Reitsma, Goldhaber-Fiebert and Salomon2021), we purposefully oversampled individuals who identified as Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black, compared to non-Hispanic White respondents. This sampling scheme helped ensure our findings are generalizable to communities disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. While our sample is thus not statistically representative of the US adult population, our randomized study design and control for demographic (gender, age, race, education, income), belief (political ideology, religiosity), and behavioral (flu vaccine uptake) characteristics result in our study being internally valid.

Participants in T1 (n = 3,900; fielded between January 11 and February 3, 2021) were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions, consisting of three visual policy narrative treatment conditions and a control condition (Table 1). In T2 (n = 2,268; fielded between March 22 and April 9, 2021), the research team added one of three narrators to each experimental condition: “your friend”; “your doctor”; and “the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)” or a control condition: “someone” (Table 1). In T2, participants received the same visual message condition they were exposed to in T1, with the addition of one of four randomly assigned narrators. In T2, the visual policy message was presented below the following prompt: “[narrator/control] sent this to you.” Between T1 and T2, the distribution across each condition was about the same (approximately 25%), assuring that no one condition from T1 experienced more non-responses in T2 (Table 1).

To test the influence of the narrator, we conducted a mediation analysis (Figure 1) on four models. Each model contained one visual message condition: “get the vaccine”; “protect yourself, get the vaccine”; “protect your circle, get the vaccine”; “protect your community, get the vaccine” (see Table 1 for visual messages). Each visual message condition had one of four experimental narrator conditions affixed to it. As depicted in Figure 1, we test for direct effects of narrator condition (Xi) on motivation to vaccinate (Y1) and for the mediation effects of narrator condition (Xi) through affective reaction (M1) and motivation to vaccinate (Y1), controlling for covariates (F1…Fj) (see Supplement A for descriptive statistics of all variables). We control for covariates known in previous literature to affect how narrative messages are received. Specifically, we include covariates for trust in information provided from sources that match all three of the narrators in this survey experiment (e.g. Lybecker et al. Reference Lybecker, McBeth, Sargent, Jones, McBeth and Shanahan2022; Dodd and Rife Reference Dodd and Rife2024; DeLeo et al. Reference DeLeo, Shanahan, Taylor, Jeschke, Crow, Birkland, Koebele, Danielle Blanch-Hartigan, Sangappa, Albright and Minkowitz2024). We also account for belief covariates: perceptions of risk severity and likelihood, religiosity, and political ideology (Koebele et al. Reference Koebele, Albright, Dickinson, Danielle Blanch-Hartigan, DeLeo, Shanahan and Roberts2021; Elgin Reference Elgin2014; Calvillo et al. Reference Calvillo, Ross, Garcia, Smelter and Rutchick2020; Druckman et al. Reference Druckman, Ognyanova, Baum, Lazer, Perlis, Volpe and Santillana2021). Demographic variables of age, gender, race, income, education, and having children are also included, as a number of studies suggest that COVID-19 vaccination attitudes and uptake differ based on these characteristics (Dhanani and Franz Reference Dhanani and Franz2022; Paul, Steptoe, and Fancourt Reference Paul, Steptoe and Fancourt2021). Previous experience with COVID-19 and previous flu vaccine frequency are included to account for differences in attitudes towards the risk (Dolu et al. Reference Dolu, Turhan and Yalnız Dilcen2021; Dhamayanti et al. Reference Dhamayanti, Andriyani, Moenardi and Putri Karina2024).

For the analysis, we used Hayes’ (Reference Hayes2022) PROCESS macro in SPSS to examine the mediating effects in our study. Based on the conceptual model (Figure 1), we selected model 4 in the PROCESS macro to include one mediator, affective reaction, and set motivation to get the vaccine as the dependent variable for the four models. We specified narrator condition as multi-categorical and chose indicator coding such that each treatment condition (i.e., narrator) is compared to the control condition (“someone”) to determine effect on the mediator and outcome variable. We included all the 15 covariates listed in Supplement A. Finally, we built four models following the same settings above for each of the four visual experimental conditions (“get the vaccine”; “protect yourself, get the vaccine”; “protect your circle, get the vaccine”; “protect your community, get the vaccine”).

To test for multicollinearity, we performed Fisher’s exact tests between each pair of categorical independent variables to see whether there were significant correlations among predictors. The significant p-values suggest possible multicollinearity among some variables. We then calculated a modified Generalized Variance Inflation Factor (GVIF) using the approach suggested by Fox and Monette (Reference Fox and Monette1992). The results of the multicollinearity test are reported in Supplement B, whereby each column of figures represents the modified GVIF estimates of each narrative model. Using the threshold of modified GVIF greater than 10 (Vittinghoff et al. Reference Vittinghoff, Glidden, Shiboski and McCulloch2005), none of the variables in the models were found to have yielded a GVIF that exceeded the threshold.

Results

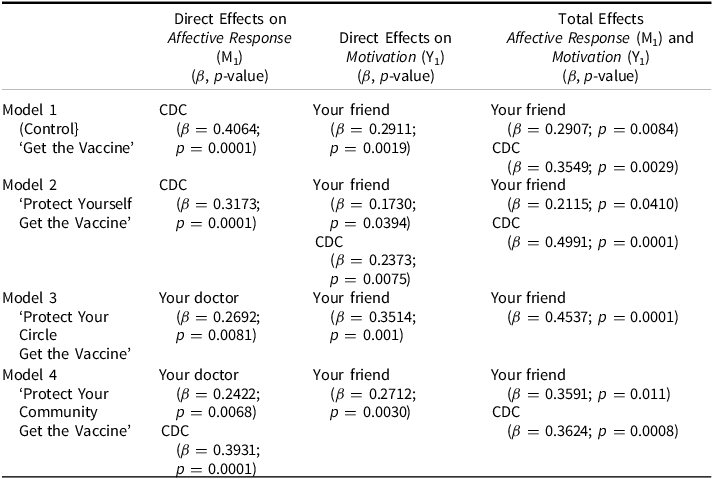

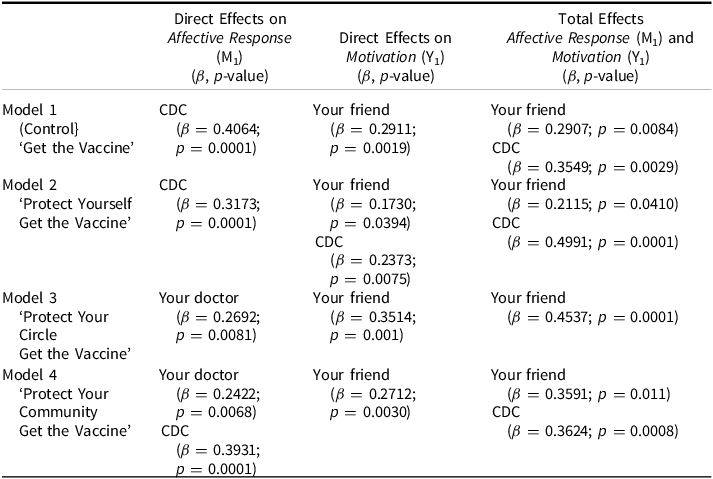

We present results by hypothesis; for full results, see Supplement C. The proximity hypothesis assesses the extent to which lower construal levels (closer proximity of the narrator) influence motivation to get the COVID-19 vaccine, regardless of the visual narrative content. We measure significance through the total effects of the narrator’s proximal influence, which accounts for both the direct effects on motivation and indirect or mediated effects of affective response. Given that construal level theory suggests that individual level decisions (in contrast to higher level goals) are motivated by more proximal messaging, we hypothesized that the most proximal narrator, “your friend”, would have significant effects on motivation to get the vaccine in comparison to the control (“someone”) across all visual policy message conditions. The proximity hypothesis is not upheld, given that the total effects for “your friend” was not significant regardless of narrative content. Indeed, no narrator or control condition held significance, holding the visual message conditions essentially constant. In sum, the low construal level or proximal narrator alone did not reveal consistent total effects on motivation to vaccinate.

This then leads to our next hypothesis concerning congruence, which predicted statistical significance of narrator effect when there was congruence between the spatial distance presented in the visual policy narratives and the relational distance in the narrator. The congruence hypothesis is upheld for proximal congruence. The effects were significant on motivation to get the COVID-19 vaccine for the most relationally proximal narrator (“your friend”) and the most spatially proximal narrative content (“protect yourself”) (β = 0.5109, p = 0.0690). In other words, those who received the message to “protect yourself, get the vaccine” from “your friend” as the narrator were motivated to get the vaccine at statistically higher rates in comparison to the control. Thus, in this exploratory study, proximal narrators when paired with proximal narrative content appear to have some influence on motivation. However, we also discovered two contrary findings. First, the most distal narrator, “the CDC,” also had a statistically significant effect (β = 0.4837, p = 0.0809) on vaccination motivation in the spatially proximate narrative content “protect yourself, get the vaccine”. Second, whereas we expected significant effects when the middle-distanced narrator, “your doctor” was paired with the middle spatial distance in the message content (“your circle”), we found that there was a negative significant effect in motivation to vaccinate. One interpretation of these seemingly contradictory findings is that, although narrators matter, their impact is refracted through a much more complex narrative environment where the content of narratives themselves can either magnify or diminish their (the narrators’) relative influence.

The results for the narrator trust hypothesis revealed interesting dynamics in the case of COVID-19 vaccine. When we observed the significant influence of the congruent proximal narrator “your friend” with the proximal “protect yourself” visual policy narrative treatment on motivation to vaccinate, we find that higher levels of trust in the friend narrator is significant in total effects (β = 0.2115, p = 0.0410). Thus, the narrator trust hypothesis is upheld for proximal narrators paired with proximally congruent narrative content.

Additionally, we found illuminating results when examining the influence of trust in narrators as sources of information on affective response and motivation alone (Table 2). Higher levels of trust in “the CDC” as a source of information for COVID-19 vaccines resulted in higher levels of affective responses across three of the models, and higher levels of trust in “your doctor” as a source of information for COVID-19 vaccines resulted in higher levels of affective responses for the intermediate and distal visual policy narrative messages “protect your circle” and “protect your community,” respectively. In tandem, higher levels of trust in “your friend” as a source of information for COVID-19 vaccines resulted in higher levels of motivation to get the vaccine across all models. Thus, trust in more distal sources of information – “the CDC” and “your doctor” narrators – evoked greater affect, whereas trust in the most proximal source – “your friend” – instilled motivation to vaccinate. These results give some indication that what moves people affectively and motivationally is a combination of trust in proximal and the expertise of our distal narrators. Echoing the findings reported in the previous paragraph, our findings regarding the importance of trust challenge a monolithic perspective of how a narrator can wield influence in the policy process. From a practical perspective, this suggests that some narratives may yield more immediate actions on the part of the audience than will others, which will have a subtler and perhaps longer-lasting influence on attitudes about the messages propagated by particular classes of narrators.

Table 2. Role of trust in narrators

Discussion

Because narratives are intended to motivate action or shape thinking in the target audience, this exploratory study investigates the extent to which the nature of the narrator is consequential with respect to key variables such as narrator proximity, congruence, and trust. In our study, we found that the relationships between narrators and the recipients of narratives are complex and, in some ways, unexpected. We discovered that the proximal narrator, “your friend”, had no significant effect across models as the Construal Level Theory would suggest for individual decisions (e.g., thinking about getting the COVID-19 vaccine), which may be attributed to the fact that individuals were engaging in social distancing. Bowen (Reference Bowen2021) explains that social distancing is a form of geographic distancing, in which individuals are separated physically. In such instances, individuals will be led to think more abstractly about the people they are closest to relationally. Consequently, individuals would be led to focus more on their feelings about their friends and loved ones and their central attributes.

We discovered that congruence between narrator and narrative content in terms of proximal dimensions does influence participant motivation. Thus, narrators do not exist in a vacuum, but, rather, are necessarily tethered to narrative content. And the proximal feature prevailed. One could argue that this finding is consistent with core NPF assumptions, which assert that narratives are a mosaic of features that collectively shape individual and policymaker behavior. Therefore, a change in any one feature of the narrator or narrative content necessarily changes the overall effect of both on key outcomes.

Equally important, we found that greater trust in more distal narrators – one’s doctor or the CDC – is associated with a greater affective response, while trust in more proximal narrators is associated with greater motivation to seek vaccination. While ours is hardly the first study to highlight trust as an important predictor of individual behavior, it is the first, to our knowledge, to explicitly link trust to narrator influence.

Contributions and future directions

Our analysis yields major contributions to the study of the NPF. The NPF has long recognized the power of narrative form (e.g., characters) and content (e.g., devil-angel shift) in the policy process. Yet, the power of the narrator, the one telling the story, is not as well understood in the NPF primarily due to a lack of robust theoretical thinking about the role of the narrator. This study attempts to close this gap by highlighting the work in narratology on narrators to inform inquiries of policy narrators, specifically narrator definition, features (overt–covert, demographic features), and functions (trust). In our study, we assert that the narrators in our experiment are the purveyors of a COVID-19 vaccine visual risk message. The narrator feature we test is that of psychological distance, informed by Construal Level Theory (CTL; Trope and Liberman Reference Trope and Liberman2010). The narrator function we test is that of narrator trust, informed by the audience’s assessment of the narrator’s credibility (Nünning Reference Nünning and Nünning2015).

More practically, our findings point toward different strengths of trust in different types of narrators over the course of individual decision processes. Inducing a positive affective response is sometimes an important mediator to behavior, but there may also be a direct effect on the desired behavioral outcome, in this case, the deeply personal decision to adopt a novel vaccine. When put in this context, it follows that higher levels of trust in proximal narrators may be required to more directly affect respondents to adopt a risk mitigating behavior as opposed to having an indirect effect through affective response. Narrator characteristics cannot be viewed in a vacuum and as one attribute changes, it may modify the influence that the narrator has overall.

Expanding upon the work presented here, there are other theories NPF scholars may bring to bear in assessing the role of the narrator. For example, to what extent do known narrators evoke system 1 thinking (fast, automatic, intuitive thinking that allows for quick judgments) and unknown narrators evoke system 2 thinking (slow, deliberate, conscious thinking that requires deeper consideration) (Kahneman Reference Kahneman2011). Another suggestion for NPF scholars to build on these findings is to test the transportability of point of view (overt-covert) theory and the positive association between first person accounts and behavior uptake. Do these results hold across environmental, energy, or other social policy contexts? Anchoring inquiries to theory with clear operationalization of concepts will allow for the bank of NPF narrator studies to lead to valid and reliable results.

Narrator studies tend to be micro-level studies to measure effect size. Our findings suggest that NPF scholars should also grow knowledge of the power of narrators in meso-level studies as well. For example, whereas in this study we assess the relative effect of rather specific narratives emanating from equally specific narrators at a fairly fixed point in time, meso-level studies may look at how evolving trust in specific groups of narrators across time affects the relative influence of their narratives. Indeed, several years have passed since our survey was fielded and, in that time, we have observed marked decline in trust for both doctors (Perlis et al. Reference Perlis, Ognyanova, Uslu, Trujillo, Santillana, Druckman, Baum and Lazer2024) and key public health institutions, including the CDC. At a meso-level, we may expect diminishing levels of trust in their actors to have a profound effect on receptivity to the various narratives communicated by these narrators.

For the NPF, the importance of the narrator as a narrative element is understudied. While narrator trust has long been hypothesized to be a key function of a narrator, we suggest that narrative features have remained largely unexplored and undertheorized. As a framework, NPF draws on theory from psychology, neurology, marketing, sociology and more to inform and anchor tests of narrative influence. We offer an example in this exploratory study of using CLT to test narrator characteristics. Additionally, distilling the complexity of the power of narrators alone compared to the power of narrators paired with narrative form and content will significantly advance our larger understanding of the power of policy narratives in the policy process.

Conventional political wisdom tells us that, in policy and in life, the messenger is often just as important as the message. Indeed, the proliferation of ad hominem attacks as a strategy for promoting or blocking the emergence of new ideas within the political system pays testament to the fact that narrators serve a vital role in disseminating policy narratives and, ideally, convincing others of their viability. To this end, we implore the NPF community to continue working towards a more robust understanding of the role of narrators within the policy process, as doing so will not only advance a core conceptual tenet of the framework but will also help ensure that we remain adept at informing ongoing debates about the role of narratives within contemporary political discourse.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X25100937

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available on the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/2LCWPI

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation under Grant No. DRMS-2102905 and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15AI176375. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health.