Introduction

The beginning of the twenty-first century could have been expected to be the era of democratic triumph after a long period of international instability, including the Cold War and internal pressures stemming from the crisis of representation and voters’ apathy. The democratization waves of the 1980s and 1990s seemed to give some credit to that expectation, with many states becoming democratic for the first time (Diamond Reference Diamond2021). The collapse of communism in Central and Eastern Europe, along with the global transformations of the 1990s, gave rise to—or created the illusion of—an international consensus not only in favour of democracy over non-democratic regimes but also in support of a democracy based on the separation of powers, the rule of law, and individual rights—that is, liberal democracy. As noted by Wolff, the struggle over the meaning of democracy diminished, resulting in a convergence around “a decontested liberal democracy” (2023).

Over the past decades however, the consensus around liberal democracy has broken down, if it ever existed (Coman Reference Coman2022). Liberal democracy—or constitutional democracy (Plattner 2021: 45)—which has been promoted for decades by a variety of regional, national and international actors—is at a crossroads as it is receding across the world (Boese et al. 2022; Börzel et al. 2024). Although various studies remind us that this is not the first time that liberal democracy has come under strain (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016; Berman Reference Berman2019), over the past decade, contestation has heightened, political and social actors within the EU and beyond becoming ever more institutionally embedded and vocal in contesting either the ideal of liberal democracy or its practice. This contestation has led to various forms of conflict opposing political, social, and legal actors both within nation-states and at the supranational level, about the nature of the polity and often taking the form of conflicts of sovereignty (Bickerton et al. Reference Bickerton, Brack, Coman and Crespy2022).

Yet, political actors vary in their opposition to liberal democracy, with some explicitly advocating its complete dismantlement, while others selectively challenging specific liberal democratic principles and practices without rejecting the system entirely. These positions can be found across the political spectrum, emerging from parties in opposition but also from parties in government, from the left and the right and extend beyond party politics to include institutional actors and civil society organizations operating both at national and supranational levels.

The current dissensus over liberal democracy takes place against the backdrop of a global crisis of democracy whose causes and consequences overlap and feed one another. Although particular attention has been paid to the crises of the last decades, a large body of literature shows that the transformation of European democracies is a process with more distant origins (Mair Reference Mair2007, 2023). In that respect, the European Union constitutes an interesting field to examine how liberal democracy has become a source of conflict as the decade of crises has provided a fertile ground for its contestation, with a growing success of radical and populist parties (at the bottom, in the Member States) and the increasing centralization of powers among executives (at the top, in the EU polity).

Against this backdrop, the aim of this Special Issue is to address, theoretically and empirically, the following questions:

-

1. What is the nature of the current dissensus over liberal democracy?

-

2. How and to what extent do different actors contribute to the ongoing dissensus?

-

3. What are the implications of this dissensus for the EU’s policies and policy instruments?

In this Special Issue, dissensus is understood as a “conflict between different types of actors, either about the fundamental principles of liberal democracy (its institutions or polity) and rights or about their implementation through specific policies, or both” (Coman and Brack, 2025, in this issue). Dissensus over liberal democracy refers to the ongoing context where liberal democracy is politicized, when it emerges in public debate as a dominant theme amid ongoing social and political transformations. Dissensus, we argue, shapes both policies and polity.

The introduction to this Special Issue is organized as follows: Section The puzzle: dissensus over liberal democracy, a turning point for European democracies introduces the puzzle and situates the concept of dissensus in the literature. Section How to study dissensus and the Special Issue discusses how dissensus can be studied as dependent and independent variables and provides an overview about how the contributions in this issue address these questions.

The puzzle: dissensus over liberal democracy, a turning point for European democracies

We live in a world in which the hopes of the 1990 s that democracy and rights would triumph everywhere are crumbling, in some contexts like a sandcastle, in others in more incremental and elusive ways and the EU is no exception. Not only its foundations—institutions, norms and values—are eroding, but also the belief in the efficacy and the responsiveness of liberal democracy has declined (Berman Reference Berman2019). Different factors are disputed to explain the global crisis of democracy (Börzel et al. 2024). Some of them are recent, such as the Great Recession of 2008 and the eurozone crisis, the rise of populism and of undemocratic liberalism (Mudde Reference Mudde2021), amplified by the global health crisis. Others are older and go back to the domestic transformation of the Nation States after the WWII and to the emergence of polities beyond the state, including the EU. The transformation of democracy in Western Europe and the crisis of representative democracy cannot be dissociated from European integration which has reshaped their institutions, democratic norms and practices (Bickerton Reference Bickerton2012; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2006).

Since the early 2010s, liberal democracy has been openly contested from below. The most outspoken and virulent criticism of liberal democracy has come from “exclusionary populists”, i.e. authoritarian and nativist populists or anti-establishment parties, as they blatantly attack the core pillars of liberal democracy (Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Kaltwasser2012). As noted by Pappas (Reference Pappas2016: 33–35), the main threat to political liberalism comes from populists. They thrive where institutions are weak and majoritarian tendencies are strong. Initially marginal in Europe in the 1980s, populist parties have flourished in recent years and ascended to power in several Member States of the EU (Mudde Reference Mudde2021). There has been an extensive academic debate as to whether populism is a threat or a corrective to liberal democracy (Bugarič, Reference Bugarič, Krygier, Czarnota and Sadurski2022; Galston Reference Galston2018; Kaltwasser Reference Kaltwasser2012; Vittori Reference Vittori2022). Populists accept the basic principles of democracy, such as the ideal of popular sovereignty and majority rules (Mudde Reference Mudde2013: 14), but they embrace “a vision of democracy which is not tied to liberalism or to constitutionalism” (Plattner Reference Plattner2010:88). Indeed, populism challenges the essence of contemporary liberal democracy. At the same time, populism comes in different forms. Scholars have distinguished between authoritarian populism and democratic populism (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). The former leads to democratic backsliding as it targets pluralism, and has mediated forms of political representation as well as checks and balances (Pappas Reference Pappas2016; Rummens 2017; Urbinati Reference Urbinati2014; Vittori Reference Vittori2022). The latter can be seen as a corrective for democracy which can foster democratization and inclusiveness (Bugarič, Reference Bugarič, Krygier, Czarnota and Sadurski2022: 28), in particular, when it “remains in the boundaries of liberalism” (Corso Reference Corso, Krygier, Czarnota and Sadurski2022: 76).

Although not all populists share the same agendas, recent examples show that once in power, radical populist parties have targeted the transformation of norms and institutions of liberal democracy (Blokker, 2022; Krekó and Enyedi Reference Krekó and Enyedi2018), through abusive constitutionalism (Krygier Reference Krygier, Krygier, Czarnota and Sadurski2022: 6), autocratic legalism (Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018), constitutional coups (Sadurski Reference Sadurski2019), or abuse of the constitution (Blokker 2014) paving the way towards autocratization. In some cases, their explicit aim is to separate democracy from liberalism, in the name of a certain conception of democracy and of the people which excludes the intermediation of liberal democratic institutions (Schmidt 2023). As an illustration, since the 2010s, in Poland and in Hungary elected officials have undone checks and balances through a wide range of interventions in the judiciary, limiting the powers of Constitutional Courts as well as the independence of judges, “twisting and turning of the rule of law” (Krygier Reference Krygier, Krygier, Czarnota and Sadurski2022: 6). The “bad” elite has been replaced by the “good” elite (Bill Reference Bill2022), the one supposed to represent the interests of the true demos. Pluralism and multiculturalism have also been under attack, as well as rights and freedoms, all in the name of the people and against supranationalization (Bill and Stanley Reference Bill and Stanley2020; Sata 2023). Only elections seem to still remain “competitive”, but, as Krygier put it, in a context in which freedoms are eroded (2022: 7). In a nutshell, the pillars of liberal democracy, characterized by electoral regimes, political and civil rights, as well as accountability and the structure of power (Merkel Reference Merkel2004) have been dismantled one by one, in some contexts incrementally and in others more abruptly.

But the crisis of liberal democracy, we argue, goes beyond the rise of right-wing populist parties (Milstein 2021: 27). In recent years, mainstream political parties have contributed to the rise of “undemocratic liberalism” (White 2020) or “authoritarian liberalism” (Wilkinson 2018) fuelled by “emergency politics” or “governing by the principles of necessity” in the European Union (White 2020). In the decade of crises, decisions have been taken away from representative bodies or by legislation put in the hands of experts or constitutional judges (Czarnota Reference Czarnota, Krygier, Czarnota and Sadurski2022). The Eurozone crisis, as well as the attempts of the EU to sign new trade agreements, are good illustrations of the contestation of decisions taken for the people but without the people (Schmidt 2020). Despite the attempts to democratize the EU in the post-Maastricht era, this phenomenon became increasingly pronounced and amplified, particularly during periods of crisis. Although concerns about the EU’s democratic deficit predate the succession of recent crises and have partially been imputed to its technocratic and free-market bias (Caramani Reference Caramani2017; Follesdal and Hix Reference Follesdal and Hix2006), the EU’s response to these crises has had a significant impact on its decision-making process, its nature and policies. In particular, the succession of crises has placed additional strain on democratic institutions (Fasone and Fromage 2017; Christiansen et al. Reference Christiansen, Griglio and Lupo2021). Decision-making processes have been increasingly conducted without public scrutiny, elevating the role of non-majoritarian institutions (Schäfer and Zurn, 2023) and unelected actors, notably lawyers and technical experts (Bickerton 2023; Kovanic and Steuer Reference Kovanic and Steuer2023). In this context, the executive branch has emerged as the main actor, with increasing oversight and extended powers to technocratic institutions such as the ECB, the Commission, and the Court of Justice of the EU, while parliamentary debates and parliamentary authority have been bypassed both at the national and EU level (Bickerton et al. Reference Bickerton, Hodson and Puetter2015; Schmidt 2023). This way of managing crises with major implications (Schmidt 2020) has cast a shadow on democracy and has fuelled waves of discontent and dissatisfaction. Both EU and national leaders have, with varying degrees of success, obscured the political nature of the measures taken to deal with the various crises, whether austerity, recovery plans or responses to the pandemic (Bourgeaux, 2023; Borriello Reference Borriello2017; Donà, Reference Donà2022). And these measures were mostly justified on the basis of the need to return to “market conditions” and competitive economic practices, and were presented as the only viable alternative. However, They also have given rise to questions about “who governs” (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2022) and about the relationship between democracy and the economy, or the coexistence between capitalism and democracy (Wolff Reference Wolff2023). As Dahrendorf (Reference Dahrendorf1996) already noted three decades ago, globalization and crises create perverse choices for liberal democracy, as governments have to square the circle of ensuring economic competitiveness, social cohesion and political freedom.

For political scientists, the question of whether it is the financial and economic crisis that has fuelled the success of populism or whether it is the way liberal democracy responded to crises that explain the great success of populist parties is still open to interpretations. Some scholars argue that populism is a consequence of undemocratic liberalism (Mudde Reference Mudde2021), while others consider that economic liberalism has failed but political liberalism is held responsible (Vormann and Weinman, 2021: 11). More generally, populism is often seen as a threat to democracy (Galston Reference Galston2018; Ruth-Lovell and Grahn Reference Ruth-Lovell and Grahn2023). The polarizing effect of global markets and economic insecurity might lead to authoritarian temptations, as governments try to ensure social cohesion and economic competitiveness at the expense of some aspects of liberal democracy (Dahrendorf Reference Dahrendorf1996; Anheier and Filip Reference Anheier and Filip2021). This Special Issue does not discuss the sequence of events and their causal links. Yet, all these crises combined set the stage for the flourishing dissensus surrounding liberal democracy.

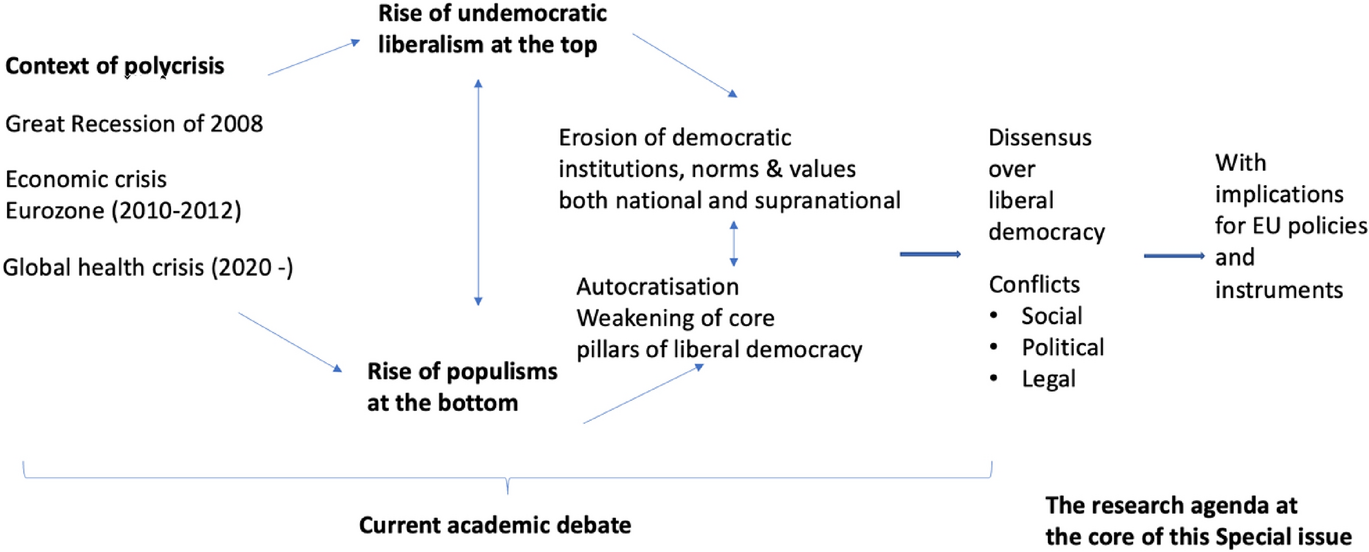

We argue that these two broad and interconnected phenomena—the challenge to liberal democracy from below and from the top—have provided fertile ground for debates about the nature of the polity and its core values, but also for the erosion of democratic institutions, norms, and values in some countries, while in others, it led to the dismantlement of core pillars of liberal democracy and even autocratization. Dissensus over liberal democracy takes place in this specific context (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Situating dissensus over liberal democracy in current academic debates

Liberal democracy has always had been contested, notably by radical and anti-system actors.

However, we argue in this issue that:

-

1. The stances and claims against liberal democracy are no longer located at the extremes of the political spectrum but have become mainstreamed and have expanded beyond the fringes of society. Not only populists from different ideological corners target liberal democracy, there is also a crisis of conviction in the centre (Vormann and Weinman, 2021), leading a wide range of actors—less studied in the literature—to politicize aspects of liberal democracy and to contend that liberal democracy needs to be reinvented or reformed (Berman Reference Berman2019; Vormann and Weinman, 2021; Mudde Reference Mudde2021).

-

2. Dissensus manifests in different arenas (social, political, and legal). Various conceptions of democracy and its core pillars are disputed within the EU, at the domestic and supranational levels, as a wide range of national political, social, and legal actors and the EU compete in safeguarding and upholding democratic institutions and values.

-

3. Dissensus over liberal democracy shapes both specific policies (ranging from climate change to migration and gender issues) to core principles of the political game (polity), which for long have been taken for granted.

Dissensus does not occur in a vacuum. It is shaped by the institutional context in which it takes place. Indeed, the institutional features of the political regime matter to understand contemporary dissensus. First, they determine what form(s) and degree of dissensus are possible. The institutional design, for instance, the electoral system and the structure of the state as well as the nature of the political regime, can have an impact on the degree of conflict: regimes with proportional representation and multiparty coalitions are less prone to extreme polarization (Horne et al. Reference Horne, Adams and Gidron2023; Van der Meer and Rijpkema Reference van der Meer and Rijpkema2022) and can be expected to be less conducive to extreme conflict. Second, the institutional design also conditions the arenas, the actors’ tools and expressions of the conflict over liberal democracy. The constitutional and legal structures of the polity determines at which level(s) conflicts may take place, especially in a multilayered system like the EU, but also the potential tools (political, social, legal) actors can mobilize to politicize the conflict and the channels through which dissensus can be voiced (Diamond Reference Diamond2021).

How to study dissensus and the Special Issue

Dissensus over liberal democracy can be studied as something to be explained (i.e. its contours and forms of expression in terms of actors and goals) or as something which explains (i.e. the impact that dissensus has on policies and polity for instance). The articles of this Special Issue either concentrate on the nature of dissensus or seek to understand the implications of dissensus for policies and polity.

Scholars interested in analysing dissensus as dependent variable might focus on its nature and main dimensions. Five articles in this Special Issue are an illustration of this approach.

As noted by Ramona Coman and Nathalie Brack , shedding light on this phenomenon requires close attention to the nature of dissensus and to whether the conflict is centred on the ideals of liberal democracy or on its practices. With dissensus being the very essence of politics (Rancière Reference Rancière2010) and democracy itself, dissensus over liberal democracy is understood as a conflict opposing different types of actors, whose aim vary between preserving, restructuring, or replacing this model of political organization. If democracy is a work in progress everywhere, dissensus as a conflict encompasses actors with different goals, some of them being in favour of maintaining the status quo, others of replacing liberal democracy or rejecting it altogether, whether by reforming its policies or its fundamental principles. In other words, dissensus is not limited to those actors who aim to replace liberal democracy with non-democratic forms, altough the frontal critique of liberal democracy comes from these actors. Coman and Brack propose a typology of dissensus based on two dimensions: the focus of the conflict (the fundamentals or ideal of liberal democracy or its practice) and the heterogeneity of the goals of the actors. Four types of dissensus are conceptualized. First, mild dissensus refers to a conflict in which actors target the practice of liberal democracy, namely a specific policy or decision-making procedures, and in which their preferences are rather homogeneous despite differences. Second, severe dissensus reflects a situation where the conflict pertains to the practice of liberal democracy but where the actors’ goals are heterogeneous and far apart from each other. Third, disruptive dissensus pertains to the principles of liberal democracy as new claims or actors start to challenge the rules of the game. Conflicts are disruptive due to the underlying ambitions that drive them and actors’ preferences are at odds with pre-existing ones. The last type is destructive dissensus, which arises when both the ideal of democracy and its practice are at the heart of the conflict and the goals of the actors are fundamentally irreconcilable.

With a focus on the polity level, Martin Deleixhe draws insight from the discussions in political theory on dissensus to examine the alleged lack of a European demos as a democratic problem and the rise of a pan-European dissensus that could usher a European people. To do so, the article examines the relationship between consensus, dissensus, opposition, and partisanship. The author argues that a dissensus-based understanding of peoplehood has the potential to break the current conceptual deadlock regarding whether (or not) the attempt to build a democracy at the European level can claim to rely on a European people.

The next two articles focus on dissensus at the regime level and dissensus over liberal democracy.

Focusing on the transformation of the Constitutional Tribunal in Poland under the PiS government, Wojciech Włoch and Maciej Serowaniec discuss the issue of dissensus at the constitutional level and the relationship between constitutionalism and extra-systemic dissensus. The article does not only uncover the sources of extra-systemic dissensus in Poland, namely the insufficient social legitimization of the Constitution and the perception of the Constitution by one of the main political actors as establishing an “unequal playing field for politics”, but it also shows that dissensus over liberal democracy can start as a national conflict on the polity and spill over into the EU.

Through an analysis of legislative networks as arenas of dissensus, with a focus on key moments of the constitutionalization of liberal democracy, Marta Matrakova shows how actors’ strategies matter greatly. Studying democratic reforms in three countries (Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova), article shows that institutions are arenas of dissensus. At the same time, it also shows how specific political actors develop strategies to allow, control or constrain dissensus when it comes to constitutionalizing liberal democracy, in other words how dissensus shapes the nature of the polity.

As argued in this issue, not only political but also social actors fuel dissensus over liberal democracy. Two articles contribute to understanding the nature of dissensus and the goals of the actors by exploring illiberal or anti-liberal think tanks and their ties with political institutions and media as well as with other international actors. With a focus on Hungary and Poland and on the intellectual foundations of the political projects led by Jarosław Aleksander Kaczyński and Viktor Orbán, Zsolt Enyedi and Benjamin Stanley show how the radicalization of conservative thought in the West, particularly in the United States of America, facilitated the illiberal turn of these two countries during the 2010s. In so doing, the article identifies the intellectual groups and figures at the heart of the anti-liberal dissensus, presents some of the major criticisms used against liberal democracy by these groups, traces their origins, and finally, maps the organizational infrastructure that facilitates the linkages between the circulation of ideas and their political articulation.

In a similar vein but drawing on data retrieved from Twitter, Ramona Coman, Leonardo Puleo, Emilien Paulis and Noemi Trino examine dissensus over liberal democracy in Poland and Hungary as a counter-hegemony process driven by illiberal think tanks tied with a wide range of actors in which intellectuals seem to play a pivotal role. They show how illiberal think tanks serve as crucial nodes in connecting national, European, and American intellectuals, mediating, building, disseminating, and legitimizing illiberal ideas in this emerging transnational field. Through their work and their accumulation of cultural and academic capital, these think tanks contribute to fostering dissensus over liberal democracy in Central and Eastern Europe and beyond.

Scholars examining dissensus as an independent variable might investigate how it shapes policies and polities at the national and supranational levels. In the latter case, attention would be less devoted to the nature of dissensus and more to its outcomes, as dissensus has managed to influence policies and decision-making processes both in the EU and in its member states (Zaun and Ripoll Servent Reference Zaun and Ripoll Servent2023; Coman Reference Coman2022; Schmidt 2023). The focus would either be on domestic policies or on the impact of said dissensus on the EU’s capacity to act in its internal and external policies and on the instruments used by EU institutional actors.

Christina Eckes examines dissensus in relation to climate change, focusing on the criminalization of climate protests in France, Germany, Switzerland, and the UK. Her article reflects on the role of judges in legal conflicts arising from illegal acts of climate protest. Eckes argues that judges play a crucial role in determining the nature of the dissensus and in deciding whether a potentially disruptive dissensus can become constructive. This article explores how judges can either receive dissenting voices of climate protesters and making them productive for (the legitimacy of) the democratic process, or conversely suppress them. While constructive dissensus seeks to renegotiate fundamental conceptions of justice, norms, and values through dialogue, disruptive dissensus abandons persuasive exchange in favour of confrontation, actively undermining the normative frameworks it opposes. One of the case studies examines civil disobedience, which is seen, because of its illegality as on the dividing line between constructive and disruptive dissensus. While it can be seen as constructive dissensus, the article highlights that this case illustrates how judges criminalize protesters’ actions and deprive democracy of their constructive contribution to democratic processes. Still at the level of policies, Andrea Capati and Thomas Christiansen explore dissensus in socio-economic policy. Their article analyses the interplay between legitimacy and political dissensus in EU economic governance, focusing on the European Semester and Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) implementation. Through an analysis of the Italian case, the authors examine how different types of legitimacy—democratic, technocratic and procedural—play out in EU economic policymaking, under what conditions political dissensus occurs, and what impact it has on implementing the facility. They convincingly show that strong technocratic legitimacy combined with weak democratic legitimacy leads to dissensus. What they call a "legitimacy disequilibrium" has the potential to generate political dissensus at the EU and national levels, with significant implications for EU macroeconomic governance sustainability.

Finally, Sergiu Gherghina, Bettina Mitru, and Sergiu Miscoiu examine dissensus among citizens to understand EU politics more comprehensively. They demonstrate that citizens'dissatisfaction with how the EU handled the pandemic, coupled with limited trust in its future management capabilities, significantly increases their preference to exit the EU. What the authors conceptualize as "disruptive dissensus" is linked to both retrospective and prospective attitudes towards EU policy initiatives. Their analysis reveals that the EU's (in)action in a single policy field can have tremendous consequences on citizens' preferences regarding the broader European polity.

The concept of dissensus opens new research horizons beyond studying far right actors' rejection of liberal democracy, examining instead how various political forces seek to transform democratic governance and practices. While this phenomenon has deep historical roots, its contemporary manifestations reveal crucial insights about the evolution of democratic systems and their potential future—representing one of political science’s fundamental questions about the nature and resilience of liberal democracies.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors and the editorial assistant for their support, trust, and assistance with this special issue. We also thank the authors of the various contributions in this Special Issue for their input.