Introduction

The Liberal-Labour minority government that had governed since 2012, had already implemented most of its agenda of welfare state reform before 2016. Hence, 2016 was mainly a year of preparation for the 2017 parliamentary election, with a campaign on the EU-Ukraine referendum as a prelude to that election.

Election report

EU-Ukraine Association Agreement Referendum

In October 2015 sufficient signatures had been gathered to hold a non-binding referendum on the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement (Otjes 2016). The focus of the Agreement was free trade between the EU and the Ukraine. It would also allow Ukrainians to enter the EU more easily and it would support the development of the rule of law in Ukraine. The Agreement formed a key element in the ongoing Ukraine crisis: when, in 2013, Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych refused to sign the Agreement, pro-European citizens protested in Kiev. The protests led to the impeachment of Yanukovych, but also triggered the Russian annexation of Crimea and the civil war in eastern Ukraine.

The petition drive for the referendum was organised by GeenPeil (NoPoll)Footnote 1 – a joint venture of the right-wing shock blog GeenStijl (No Style) and two Eurosceptic organisations, the Burgercomité EU (Citizens’ Committee EU) and the Forum voor Democratie (Forum for Democracy). These organisations also represented the ‘no’ campaign. They were joined by three parties in parliament: the Party for Freedom, the Socialist Party and the Party for the Animals. The key arguments of the ‘no’ campaign were economic and geopolitical: the Agreement would be bad for Dutch taxpayers and workers. Geopolitically, the ‘no’ campaign saw the Agreement as a first step towards EU membership for Ukraine, which they opposed. They warned that ratifying the Agreement would damage the relationship with Russia, as the EU would bring Ukraine into its sphere of influence.

The ‘yes’ campaign was represented by Stem Voor (Vote in Favour), a coalition of left-wing and right-wing political activists. The governing Liberal and Labour Parties, and the opposition parties D66, GreenLeft, CDA and ChristianUnion also were in favour of the Agreement. Except for D66, the parties did not wage a vigorous campaign. The ‘yes’ campaign also used geopolitical and economic arguments. On the economic side, the Association Agreement would facilitate trade. On the geopolitical side, it would increase stability and democracy in Ukraine and strengthen its ties with the EU. They also warned that not ratifying the Agreement would make the EU appear divided, which could bolster Russia. On 6 April 2016 the ‘yes’ campaign lost the referendum: 32 per cent of those eligible voted and nearly three out of five voters voted against (see Table 1). As discussed below, the follow-up of the referendum would be one of the key issues in the political year (see Issues in national politics).

Table 1. Results of the referendum on the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement in the Netherlands in 2016

Source: https://www.kiesraad.nl/

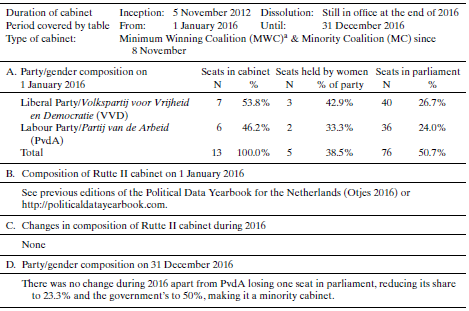

Table 2. Cabinet composition of Rutte II in the Netherlands in 2016

Note: aAs the government lacked a majority in the upper house, it was in effect a minority coalition from its start.

Sources: PDC, http://www.parlement.com/

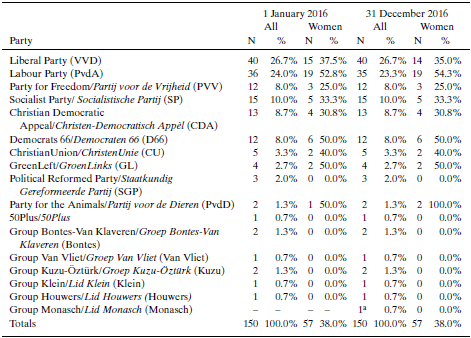

Table 3. Party and gender composition of the Lower Chamber (Tweede Kamer) of the parliament (Staten-Generaal der Nederlanden) in the Netherlands in 2016

Notes: a From PvdA.

Sources: PDC, http://www.parlement.com/

Table 4. Party and gender composition of the Upper Chamber (Eerste Kamer) of the parliament (Staten-Generaal der Nederlanden) in the Netherlands in 2016

Source: PDC, http://www.parlement.com/

Table 5. Changes in political parties in the Netherlands in 2016

Sources: PDC, http://www.parlement.com/

Cabinet report

There were no changes in the cabinet during 2016.

Parliament report

On 13 January Khadija Arib (Labour Party) was elected as speaker of the lower chamber. She succeeded Anouchka van Miltenburg (Liberal Party), who had resigned on 12 December 2015. Miltenburg stepped down because she was criticised for shredding a letter of an anonymous whistle-blower that concerned the Teeven deal that had already brought down Minister of Justice Ivo Opstelten and State Secretary Fred Teeven (Otjes Reference Otjes2016), instead of passing it on to a commission of inquiry. Arib was elected in the fourth ballot, with 83 votes out of 149. She was born in Morocco and is the first speaker of the lower chamber with an immigrant background. Because Arib has a dual nationality (Dutch and Moroccan), Party for Freedom leader Geert Wilders called her election ‘a dark day in parliamentary history’ (de Volkskrant, 15 January 2016).

On 7 November Jacques Monasch broke away from the parliamentary group of the PvdA. In April he had already strayed from the party line when he voted in favour of a motion asking for an act to repeal the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement. Now he disagreed with the party executive regarding some aspects of the election of the party leader (see Political party report). As a result, the governing Liberal-Labour coalition lost its narrow majority in the lower house, having now only 75 out of 150 seats. As the cabinet had already built up a constructive relationship with a number of opposition parties in order to secure a majority in the upper house, the loss of the parliamentary majority did not substantially change the way the government operated.

Political party report

The EU-Ukraine Association Agreement referendum campaign also had an impact on the upcoming election: the representatives of the ‘no’ campaign either registered as political parties, as Forum for Democracy as GeenPeil did, or they joined other new parties: Jan Roos (of GeenStijl) became the party leader of the Voor Nederland (For the Netherlands, VNL), a party formed in 2014 by MPs that had left the PVV. GeenPeil wants to pursue ‘direct’ democracy; if it were to gain seats in parliament, it would poll its members on every vote in parliament and vote accordingly. Forum for Democracy is a more traditional radical right-wing populist party, which focuses on breaking the control of political parties on political appointments and introducing a binding referendum.

In 2016 the parties began preparing themselves for the parliamentary election of 15 March 2017. In the second half of the year most parties represented in parliament published their draft election manifestos. In nearly all these programs issues such as health care and immigration dominated. In November and December, the congresses of the ChristianUnion, D66, the GreenLeft, the Party for the Animals and the Liberal Party approved their party's manifestos. All parties also appointed their top candidates. In most cases he (only the Party for the Animals had a female leader) was the same one as at the parliamentary election in 2012. ChristianUnion and GreenLeft had a relatively new leaders – in both cases appointed in 2015.

Only the Labour Party selected a new top candidate in 2016. Non-members who wanted to vote in the internal elections could become temporary members for a small fee (so-called ‘flash members’). Four candidates applied to take on incumbent party leader Diederik Samsom. Two of them did not fit the criteria, according to the party executive, and were excluded. The third one, MP Monasch, withdrew, as the party executive did not meet his demand that if elected he would be allowed to adapt the draft election manifesto. He left the parliamentary group of the PvdA on 7 November (see Parliament report). On 28 November he founded the party Nieuwe Wegen (‘New Ways’), which will participate in the parliamentary election of 15 March 2017. The party is in favour of a strict asylum policy and of a drastic transformation of the EU. Like the Freedom Party of Wilders, it does not accept members.

Eventually one opposing candidate remained in the Labour Party leadership race: vice-Prime Minister Lodewijk Asscher. As both he and Samsom had been responsible for the policy of the Rutte II cabinet, the political differences between the two candidates were small. Samsom's position, however, was weaker because he was held responsible for the low opinion polls on the Labour Party. On 9 December it was announced that Asscher had won the election with 55 per cent of the vote; he became the new party leader. Samsom got 46 per cent (turnout was 62 per cent).

Institutional changes

From the parliamentary election of September 2012 until the end of 2015, seven MPs had broken away from their parliamentary groups. In December 2015, to reduce parliamentary fragmentation the presidium of the lower chamber installed a working group, which had to propose measures to discourage split-offs. In June 2016, the committee presented its report: the individual mandate of the dissident MPs, which was founded on the constitution, remained untouched. Instead, the working group proposed to change the rules of procedure of the lower chamber: including less speaking time and lowering financial support for MPs who had broken away. On 8 December a large majority in the lower house voted in favour of these measures.

Issues in national politics

A dominant issue in 2016 was how the government would deal with the result of the EU- Ukraine Association Agreement referendum. Prime Minister Rutte, who had been relatively silent during the campaign, set out to broker a deal at the European level that could be ratified at the national level. As the government by the end of the year no longer had a majority in either house of parliament, he would need the support of opposition MPs.

After nine months of negotiations, a deal was struck in the European Council: an addendum would be added to the treaty that stated that Ukraine was not a prospective member of the EU, and that EU member states were not required to support Ukraine militarily or support the country financially more than they already did. D66, GL and the OSF expressed their support. This meant that the government's proposal had a majority in the lower house, but a minority in the upper house. The deal would need two more votes in the upper house. The remaining members of the upper house had either voted against the Association Agreement earlier or their parties had expressed that they wanted to respect the referendum outcome (SGP, CU and CDA). By the end of 2016 no vote had been held on the subject.