Statement of Research Significance

Research Question(s) or Topic(s): This study examined the neuropsychological underpinnings of body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs), focusing on deficits in inhibitory control, attention, and memory. Main Findings: Individuals with self-reported BFRBs did not demonstrate impaired inhibitory control compared to controls. However, they showed attentional difficulties and immediate memory deficits. Notably, the neurocognitive deficits appeared to affect only a subset of individuals with BFRBs. These findings should be interpreted within the realm of the study’s limited generalizability due to its online format, a high drop-out rate, and the absence of independent diagnostic confirmation. Study Contributions This study adds to the growing literature of neurocognition in BFRBs. It highlights attentional and memory deficits as relevant cognitive features in a subgroup. These findings suggest that BFRBs are neuropsychologically heterogeneous. The importance of identifying moderating factors such as motivation, stress, and stigma in future research is addressed.

Introduction

Body-focused repetitive behaviors (BFRBs) are harmful repetitive motor actions directed toward one’s body (Okumuş & Akdemİr, Reference Okumuş and Akdemİr2023) that are classified as obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders in the DSM-5 (APA, 2013). They encompass a range of different subtypes of activities such as trichotillomania (hair pulling), skin picking, lip-check biting, awake bruxism, and nail biting. These actions are often performed to remove parts of the body and can lead to significant impairment. Mild forms of the conditions are common (Houghton et al., Reference Houghton, Alexander, Bauer and Woods2018; Moritz et al., Reference Moritz, Scheunemann, Jelinek, Penney, Schmotz, Hoyer, Grudzień and Aleksandrowicz2024) and do not necessarily warrant treatment as they subside after adolescence (Moritz et al., Reference Moritz, Scheunemann, Jelinek, Penney, Schmotz, Hoyer, Grudzień and Aleksandrowicz2024). In more severe cases, BFRBs can cause irreversible long-term scars and/or wounds (e.g., Kang et al., Reference Kang, Lee, Ro and Lee2012; Odlaug & Grant, Reference Odlaug and Grant2008; Thompson, Reference Kim, Garrison and Thompson2013) and can compromise well-being and quality of life (Ricketts et al., Reference Ricketts, Peris, Grant, Valle, Cavic, Lerner, Lochner, Stein, Dougherty, O’Neill, Woods, Keuthen and Piacentini2024).

Neuropsychological deficits in body-focused repetitive disorder

Brain dysfunction was suspected early in BFRBs (Harbauer, Reference Harbauer1978). Deviances from controls were detected in regions implicated in habit formation and impulse control, such as the striatum and the prefrontal cortex (e.g., Chamberlain et al., Reference Chamberlain, Menzies, Fineberg, del Campo, Suckling, Craig, Müller, Robbins, Bullmore and Sahakian2008; Odlaug et al., Reference Odlaug, Hampshire, Chamberlain and Grant2016), as well as a dysregulated reward circuity (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Peris, Ricketts, Bethlehem, Chamberlain, O’Neill, Scharf, Dougherty, Deckersbach, Woods, Piacentini and Keuthen2022). Individuals with BFRBs have also been shown to have more disorganized white-matter tracts, which are involved in motor generation and suppression (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Odlaug, Hampshire, Schreiber and Chamberlain2013). In a review on neuroimaging findings in trichotillomania, Slikboer and colleagues (Reference Slikboer, Reser, Nedeljkovic, Castle and Rossell2018) reported that structural and functional changes in the ventral striatum, caudate, amygdala, occipital lobe, cerebellum, and frontal lobe are correlated with trichotillomania symptoms. However, according to the authors, these findings do not allow for robust conclusions because of small sample sizes and heterogeneity in imaging methods.

Brain dysfunction often manifests in neurocognitive deficits. Yet, the examination of neurocognitive deficits in BFRB is still in its infancy, unlike in other disorders such as depression (e.g., Hammar et al., Reference Hammar, Ronold and Rekkedal2022) or schizophrenia (e.g., Catalan et al., Reference Catalan, McCutcheon, Aymerich, Pedruzo, Radua, Rodríguez, Salazar de Pablo, Pacho, Pérez, Solmi, McGuire, Giuliano, Stone, Murray, Gonzalez-Torres and Fusar-Poli2024). Additionally, most studies have pertained to single BFRB subtypes, mainly trichotillomania and skin picking disorder, preventing generalizations.

A recent review (Barber & Lee, Reference Barber and Lee2025) on neurocognition in trichotillomania and skin picking disorder reported consistent deficits in both disorders in response inhibition (e.g., inability to suppress an already triggered motor command, reflecting an insufficiency in top-down motor control). In contrast, dysfunction in cognitive flexibility (i.e., the ability to undergo rapid changes in behavior to adapt to environmental demands) was more conclusive for trichotillomania than skin picking. Updating (which encompasses monitoring, adding, and removing information in working memory) has been found to be consistently impaired in trichotillomania but has remained largely unstudied in skin picking disorder (Barber & Lee, Reference Barber and Lee2025). Compatible findings emerged in a meta-analysis on trichotillomania that included 15 studies investigating 12 neurocognitive domains (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ioannidis, Grant and Chamberlain2024). The authors found only inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility to be impaired in people with trichotillomania compared to controls at a medium effect size. Other neurocognitive domains (“verbal learning, intradimensional (ID) shifting, road map spatial ability, pattern recognition, nonverbal memory, executive planning, spatial span length, Stroop inhibition, Wisconsin card sorting, and visuospatial functioning,” p. 158) were not impaired. Partly in line with the meta-analysis by Ali and colleagues (2024), in their literature review on 16 studies assessing the neuropsychology in trichotillomania, Slikboer and colleagues (2018) reported deficits and mixed findings in the domains of divided attention, visual memory, working memory, and the ability to suppress automatic motor reactions. Processing speed, verbal abilities, visual abilities, focused attention, short-term memory, perseveration and set shifting, planning, problem solving and decision-making, and general motor function were intact. Overall, results must be interpreted with caution because of the low number of studies on certain neurocognitive domains and small sample sizes (Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ioannidis, Grant and Chamberlain2024; Barber & Lee, Reference Barber and Lee2025).

To shed further light on the putative impairment of response inhibition in individuals with BFRB, we describe here some of the relevant original studies. To investigate this domain, the Go/No-Go task (Georgiou & Essau, Reference Georgiou and Essau2011) and the Stop-Signal Test (Matzke et al., Reference Matzke, Verbruggen, Logan, Wixted and Wagenmakers2018) are typically used. Both tests examine motor inhibition despite some differences. The Go/No-Go seems to tap into response selection mechanisms, whereas for the Stop-Signal inhibition is achieved by “proactive biasing of the sensory-motor system in preparation for the stop signal, followed by a fast reflexive inhibitory process” (Raud et al., Reference Raud, Westerhausen, Dooley and Huster2020, p. 12). Two early studies found impaired inhibitory control, assessed with the Stop-Signal Test, in both trichotillomania (Chamberlain et al., Reference Chamberlain, Fineberg, Blackwell, Robbins and Sahakian2006) and pathological skin picking (Odlaug et al., Reference Odlaug, Chamberlain and Grant2010), which is in accordance with more recent results by Chamberlain (Reference Chamberlain2021) who found stop-signal reaction times to be significantly impaired in individuals with trichotillomania compared to controls, indicating impairments in top-down executive control in BFRB disorders. In another study, Grant and colleagues (Reference Grant, Odlaug and Chamberlain2011) found impaired inhibitory control (stop-signal reaction times) in patients with pathological skin picking compared to healthy controls, whereas deficits in inhibitory control were less clear in the trichotillomania group (which had intermediate stop-signal reaction times between control and pathological skin picking group), pointing to the possible existence of subgroups of individuals with such deficits (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Odlaug and Chamberlain2011). Adding to this assumption, in another study (Bohne et al., Reference Bohne, Savage, Deckersbach, Keuthen and Wilhelm2008), motor inhibition deficits, assessed with the Go/No-Go task, were present in only a subgroup of patients with trichotillomania characterized by an earlier age of onset, thus only partly supporting the hypothesis of motor inhibition deficits in trichotillomania. Another study did not find any differences in motor inhibition except for emotion-based impulsivity in a student sample with skin picking (Snorrason et al., Reference Snorrason, Smári and Ólafsson2011), while Chamberlain and colleagues (2007) found no impairments in an affective Go/No-Go paradigm in people with trichotillomania. Regarding onychophagia (pathological nail biting), a study by Blum and colleagues (Reference Blum, Redden and Grant2017) found no significant differences in the impulsivity (i.e., motor inhibition) or cognitive flexibility of individuals with onychophagia compared to healthy controls, but the results pointed toward a trend of impaired stop-signal reaction times in onychophagia.

As the meta-analyses above indicate, memory seems to be unaffected in people with BFRBs. Yet, some of the early primary studies reported impairments in spatial memory compared to healthy controls (Keuthen et al., Reference Keuthen, Savage, O’Sullivan, Brown, Shera, Cyr, Jenike and Baer1996; Rettew et al., Reference Rettew, Cheslow, Rapoport, Leonard, Lenane, Black and Swedo1991; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Hannay and Breckenridge1997). In one other study, which assessed learning and memory besides other neurocognitive functions, the authors did not find any deficits in the comorbidity-free trichotillomania sample except for spatial working memory, which is different from explicit memory/learning (Chamberlain et al., Reference Chamberlain, Fineberg, Blackwell, Clark, Robbins and Sahakian2007). Similarly, other results do not suggest memory deficits in visual memory pattern recognition (Bohne, Savage, et al., Reference Bohne, Savage, Deckersbach, Keuthen, Jenike, Tuschen-Caffier and Wilhelm2005; Chamberlain et al., Reference Chamberlain, Fineberg, Blackwell, Clark, Robbins and Sahakian2007; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Hannay and Breckenridge1997), nor in verbal immediate or in short- and long-delayed free recall/memory (Bohne et al., Reference Bohne, Savage, Deckersbach, Keuthen and Wilhelm2008; Bohne, Keuthen, et al., Reference Bohne, Keuthen, Tuschen-Caffier and Wilhelm2005; Bohne, Savage, et al., Reference Bohne, Savage, Deckersbach, Keuthen, Jenike, Tuschen-Caffier and Wilhelm2005; Keuthen et al., Reference Keuthen, Savage, O’Sullivan, Brown, Shera, Cyr, Jenike and Baer1996; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Hannay and Breckenridge1997).Footnote 1

The present study

The neurocognitive profile of BFRB is not well understood. Research is hindered by the limited sets of studies characterized by small sample sizes and a narrow focus on single BFRB subtypes, as well the wide array of neurocognitive tests administered. Of note, tests intended to tap the same domain are not fully redundant (see Raud et al., Reference Raud, Westerhausen, Dooley and Huster2020) and may provide divergent results. Therefore, further research with larger, well-controlled, and diverse samples covering various BFRBs are warranted to identify subtypes and thoroughly assess neurocognitive functioning.

For the current study, we aimed to address this knowledge gap by administering the Go/No-Go test as a test of inhibitory control (primarily assessed with the No-Go trials; see the methods section, where we describe why we decided against the Stop-Signal Test) but also of attentional processes (Georgiou & Essau, Reference Georgiou and Essau2011; Hong et al., Reference Hong, Wang, Sun, Li and Tong2017). To examine whether neurocognitive deficits are global or more specific to impulse control, we also administered a test of explicit memory; the Verbal Learning and Memory Test (VLMT), was used to evaluate memory, learning ability, and recall. Our study assessed a large and heterogeneous sample of individuals with and without self-reported BFRBs. Alongside objective tests of neurocognition, we also examined subjective neurocognitive complaints and possible moderators of performance. Given the findings presented above, we expected impairments in inhibitory control (errors of commission) but no memory impairment.

Methods

Participants

A sample of individuals experiencing various self-reported BFRBs was recruited online via social media platforms and self-help organizations specializing in obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders. Controls were recruited from an independent trial investigating neuropsychological dysfunction in the general population (Mascherek et al., Reference Mascherek, Werkle, Göritz, Kühn and Moritz2020). The neuropsychological assessments described below were identical for both groups.

A total of 2,129 participants entered the online survey study. Blind to results, we discarded data from 738 participants for the following reasons (in descending order of frequency; multiple reasons could apply): no VLMT or Go/No-Go test (n = 579), absence of BFRB although the participant joined in the survey for individuals with BFRB (n = 218), alcohol dependence (n = 46), severe neurological conditions (i.e., Parkinson, multiple sclerosis, stroke or epilepsy, n = 39), below the age of 18 (n = 23), schizophrenia (n = 23), bipolar disorder (n = 21), did not fill out truthfully according to self-report (n = 11), made incomprehensible text entries casting doubt on reliability (n = 7), and above 70 years of age (n = 6). In subsequent analyses, we later excluded participants with other conditions than BFRB as comorbid conditions rather than the primary variable of interest may explain group differences. The final sample consisted of 419 participants with BFRB and 972 controls. Using the MatchIt function (Ho et al., Reference Ho, Imai, King and Stuart2011) in R (method “Cardinality”; Visconti & Zubizarreta, Reference Visconti and Zubizarreta2018), performed by the solver Gurobi (Gurobi Optimization LLC, 2023), we created two samples of 412 participants each, matched for age and gender (see Table 1).

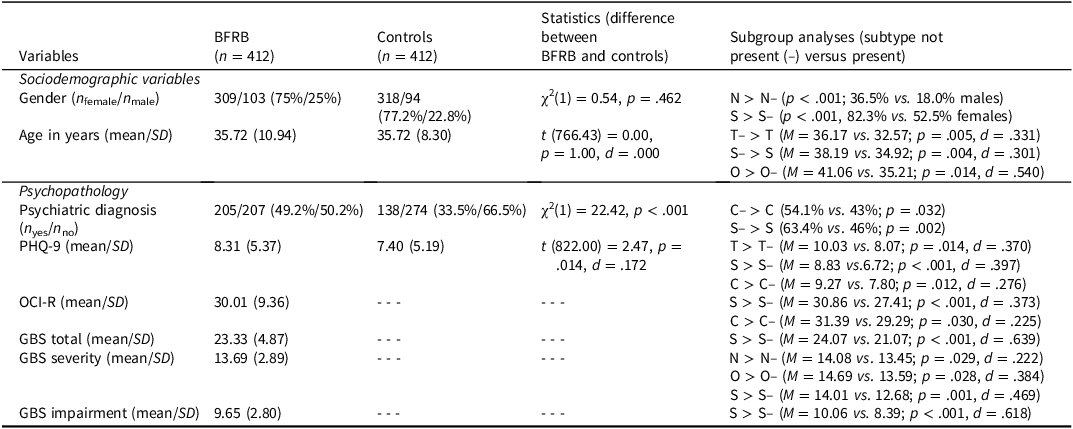

Table 1. Group differences in sociodemographic and psychopathological characteristics. Frequency, mean and standard deviation (in brackets)

Note: BFRB = body-focused repetitive behavior, C = cavitadaxia, GBS = Generic BFRB Scale, N = nail biting, O = other BFRBs, OCI-R = Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory revised, PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9, S = skin picking, T = trichotillomania.

Procedures

At first, all participants provided informed consent. In the introductory sociodemographic section, participants were asked about their age and gender. Those with self-reported BFRBs were asked whether they had ever engaged in skin picking. This was repeated for trichotillomania, nail biting, lip/cheek biting, and miscellaneous other BFRBs (e.g., thumb sucking, awake bruxism). Further, all participants were asked to report whether they had ever received a psychiatric diagnosis (i.e., no psychiatric diagnoses, obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychosis/schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorder, substance dependence, borderline personality disorder and other diagnoses or psychological problems including BFRBs, attention deficit disorder, and autism). Subsequently, somatic and neurological illnesses had to be reported, as well as medications. Any control participants who reported a BFRB were excluded from the study and did not proceed to the remaining questionnaires.

Subsequent to the sociodemographic section, participants had to read the word list of the VLMT, followed by an assessment of immediate recall (see below), which was then repeated (intermediate recall). In between the second and third VLMT recalls, we administered the Go/No-Go test as well as additional questionnaires that differed across samples (individuals with BFRB: Generic Body-Focused Repetitive Behavior Scale-8 (GBS-8; Moritz et al., Reference Moritz, Gallinat, Weidinger, Bruhns, Lion, Snorrason, Keuthen, Schmotz and Penney2022); Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Gilbody et al., Reference Gilbody, Richards, Brealey and Hewitt2007; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001); Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-revised (OCI-R; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Huppert, Leiberg, Langner, Kichic, Hajcak and Salkovskis2002); controls: PHQ-9 and other questionnaires of similar length as the ones administered in the BFRB group; see (Mascherek et al., Reference Mascherek, Werkle, Göritz, Kühn and Moritz2020)). We then asked all participants whether they experienced problems with memory and attention and whether other people had ever noticed these problems (see Table 2). After this, the third recall of the VLMT was administered, followed by a recognition trial. We also asked BFRB participants whether they were distracted by their symptoms. Finally, all participants were asked whether they had responded truthfully. Both groups of participants received a manual on relaxation exercises upon study completion. Individuals with self-reported BFRBs were also provided with the self-help “Free from BFRB” manual, providing information on alleviating BFRBs. The manuals were created by our working group. Ethical approval for this study has been granted by the ethics committee of Medical Center Hamburg (Germany, LPEK-0769b). The study followed the Helsinki Declaration.

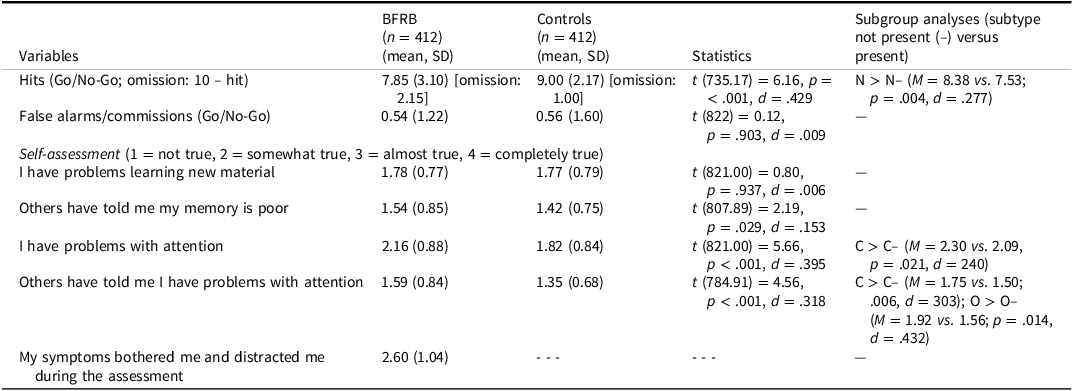

Table 2. Group differences on inhibitory control/attention (Go/No-Go) and self-assessments. Frequency, mean and standard deviation (in brackets)

Note. BFRB = body-focused repetitive behavior, C = cavitadaxia, N = nail biting, O = other BFRBs, S = skin picking, T = trichotillomania.

Neuropsychological assessment

Inhibitory control/attention: Go/No-Go

Inhibitory control was measured using a task similar to the Go/No-Go tasks from the Test Battery for Attentional Performance (Zimmermann & Fimm, Reference Zimmermann and Fimm1995). Participants were instructed to click the mouse as quickly as possible when a black “x” (target stimulus) appeared on the screen, while ignoring three distractors (red “x,” black “+,” red “+”). After a short practice, each of the four stimuli appeared 10 times in random order (40 trials total). When clicking any stimulus, this was highlighted by a red square. The program automatically recorded errors (false alarms and omissions) without providing feedback to participants. The number of false alarms serves as an indicator of deficits in inhibitory control, while omission errors (i.e., failure to respond to Go-trials) represent a measure for inattention (Meule, Reference Meule2017; Zimmermann & Fimm, Reference Zimmermann and Fimm2009) and attentional lapses (Perri et al., Reference Perri, Spinelli and Di Russo2017). Performance was calculated as hits (correct mouse clicks) minus false alarms.

In contrast to previous studies on BFRBs, we opted for a different inhibition task than the Stop-Signal Test because it poses significant challenges for online administration. Specifically, the Stop-Signal Test requires participants to withhold a response when a tone is played. In a self-paced online setting, it is impossible to control whether participants have their sound enabled or the volume set appropriately, making the Stop-Signal Test unsuitable for this format. In addition, it has been shown that both the modality of the stop signal and the volume of the tone result in different response trajectories, suggesting the reaction times rely on modality-specific cognitive resources (Van Der Schoot et al., Reference Van Der Schoot, Licht, Horsley and Sergeant2005; Weber et al., Reference Weber, Salomoni, St George and Hinder2024), which were not the subject of interest in the current study. Moreover, the Go/No-Go test serves as both a test of inhibitory control (primarily assessed with the No-Go trials) and of attentional processes (Georgiou & Essau, Reference Georgiou and Essau2011; Hong et al., Reference Hong, Wang, Sun, Li and Tong2017), allowing to test both domains. It also has the advantage that the degree of resemblance of the distractors to the target can be varied (target and distractors could vary on one or two dimensions in our test).

Memory: Verbal Learning and Memory Test

Memory was assessed using a modified version of the VLMT (Helmstaedter et al., Reference Helmstaedter, Lendt and Lux2001), the German version of the Auditory Verbal Learning Test (Rey, Reference Rey1964), which is effective in identifying mnestic deficits (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Lv, Zhou, Hong and Guo2012, Reference Zhao, Guo, Liang, Chen, Zhou, Ding and Hong2015). Participants were instructed to memorize the 15 words (word list A) that were individually presented to them for three seconds each. Participants were then asked to recall the words without any prompts and type them in any order, separated by commas. After another presentation, they performed a second recall (including the words already remembered). A third recall, without first presenting word list A, was conducted after the Go/No-Go Test and several questionnaires were administered (see above). Finally, participants received the recognition list of the VLMT consisting of all original and 17 distractor words (11 phonetic, 6 semantic). Deviating from the original version, participants were asked to rate their confidence in their response for each word using the following options: shown before, certain/uncertain; not shown before, certain/uncertain. The number of correctly recalled words (hits) at each time point represent short-, intermediate-, and long-term memory performance. False alarms (i.e., words recalled/recognized but not in the list) as well as metacognition (i.e., confidence ratings) were computed as well.

Psychopathology

Depression was measured by the German version of the PHQ-9 (Gilbody et al., Reference Gilbody, Richards, Brealey and Hewitt2007; Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) on a 4-point scale (from 0 = not at all to 3 = almost every day). The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self-report scale that has shown satisfactory internal consistency and test–retest reliability as well as criterion and construct validity (Kroenke et al., Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001; Kroenke & Spitzer, Reference Kroenke and Spitzer2002; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Rief, Klaiberg and Braehler2006).

BFRBs were measured with the GBS-8 (Moritz et al., Reference Moritz, Gallinat, Weidinger, Bruhns, Lion, Snorrason, Keuthen, Schmotz and Penney2022). With its 8-items, the scale captures different forms of BFRBs by asking participants for a joint rating if they had more than one BFRB. Every item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale. The time frame is set to the past week. The scale has two subscales measuring symptom severity (items 1–4) and impairment (items 5–8).

The OCI-R (Foa et al., Reference Foa, Huppert, Leiberg, Langner, Kichic, Hajcak and Salkovskis2002; German version by Gönner et al., Reference Gönner, Leonhart and Ecker2008), which has good psychometric properties (Abramowitz & Deacon, Reference Abramowitz and Deacon2006; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Huppert, Leiberg, Langner, Kichic, Hajcak and Salkovskis2002; Gönner et al., Reference Gönner, Leonhart and Ecker2007, Reference Gönner, Leonhart and Ecker2008; Huppert et al., Reference Huppert, Walther, Hajcak, Yadin, Foa, Simpson and Liebowitz2007), was administered to assess OCD symptoms.

Results

Tables 1–3 contrast individuals with self-reported BFRBs against matched controls on sociodemographic, psychopathological, and neuropsychological parameters. In the last column of the tables, we also report significant differences for subgroups with current symptoms versus no current symptoms (current symptoms, skin picking: n = 311, 74.49% of the BFRB sample; trichotillomania: n = 51, 12.38%; nail biting: n = 156, 37.86%; cavitadaxia: n = 142, 34.47%; other BFRBs: n = 36, 8.73%). Regarding depression, participants with BFRBs showed greater depression severity (PHQ-9) compared to controls at a small effect size. Those with self-reported BFRBs also more often reported a history of a psychiatric disorder. We therefore decided to conduct secondary analyses in which all participants with a history of psychiatric disorders (excluding BFRBs in the experimental sample) were removed (final subsamples, BFRB: n = 207, controls: n = 274) to rule out the possibility of comorbid conditions accounting for group differences rather than the primary variable of interest. The two samples without psychiatric disorders did not differ on age, gender, or depression (p > .1).

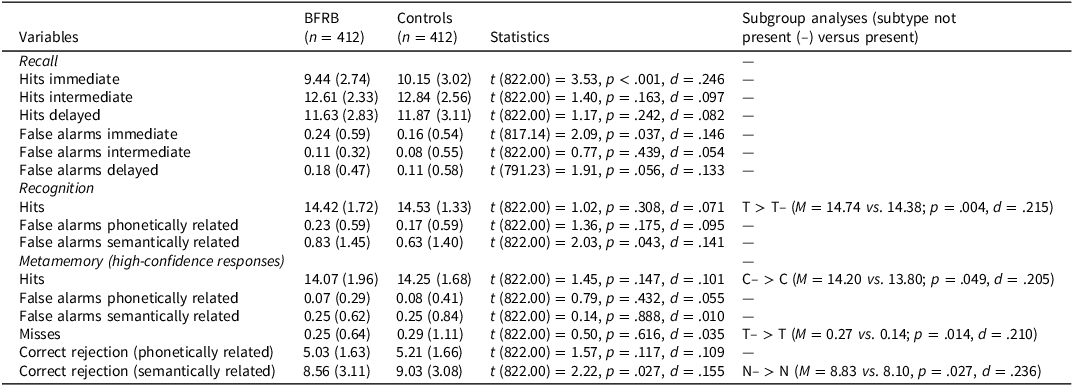

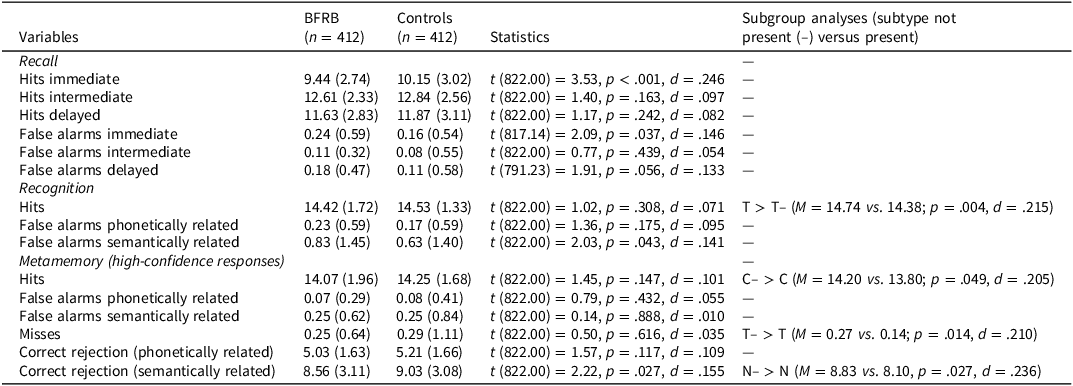

Table 3. Group differences on the verbal learning memory test (VLMT). Frequency, mean and standard deviation (in brackets)

Note. BFRB = body-focused repetitive behavior, C = cavitadaxia, GBS = Generic BFRB Scale. O = other BFRBs, N = nail biting, S = skin picking, T = trichotillomania.

Inhibitory control/attention (Go/No-Go)

We conducted a two-way mixed ANOVA with Group (BFRB, controls) as the between-subject factor and Memory Condition (hits, false alarms) as the within-subject factor. The number of responses served as the dependent variable (i.e., accuracy). The interaction was significant at a small effect size, F(1,822) = 24.10, p < .001, ηp 2 = .028, reflecting fewer hits in individuals with BFRBs (see Table 2) and comparable performance for false alarms. If we confined the sample to those without psychiatric disorders (other than BFRB in the experimental group), the effect remained essentially unchanged (p < .001, ηp 2 = .026).

We calculated the percentage of participants who fell at least one standard deviation below the mean of the control group for performance on the Go/No-Go (hits minus false alarms), which was 20.1% in the BFRB group versus 9.2% in controls (χ2 (1) = 19.62, p < .001).

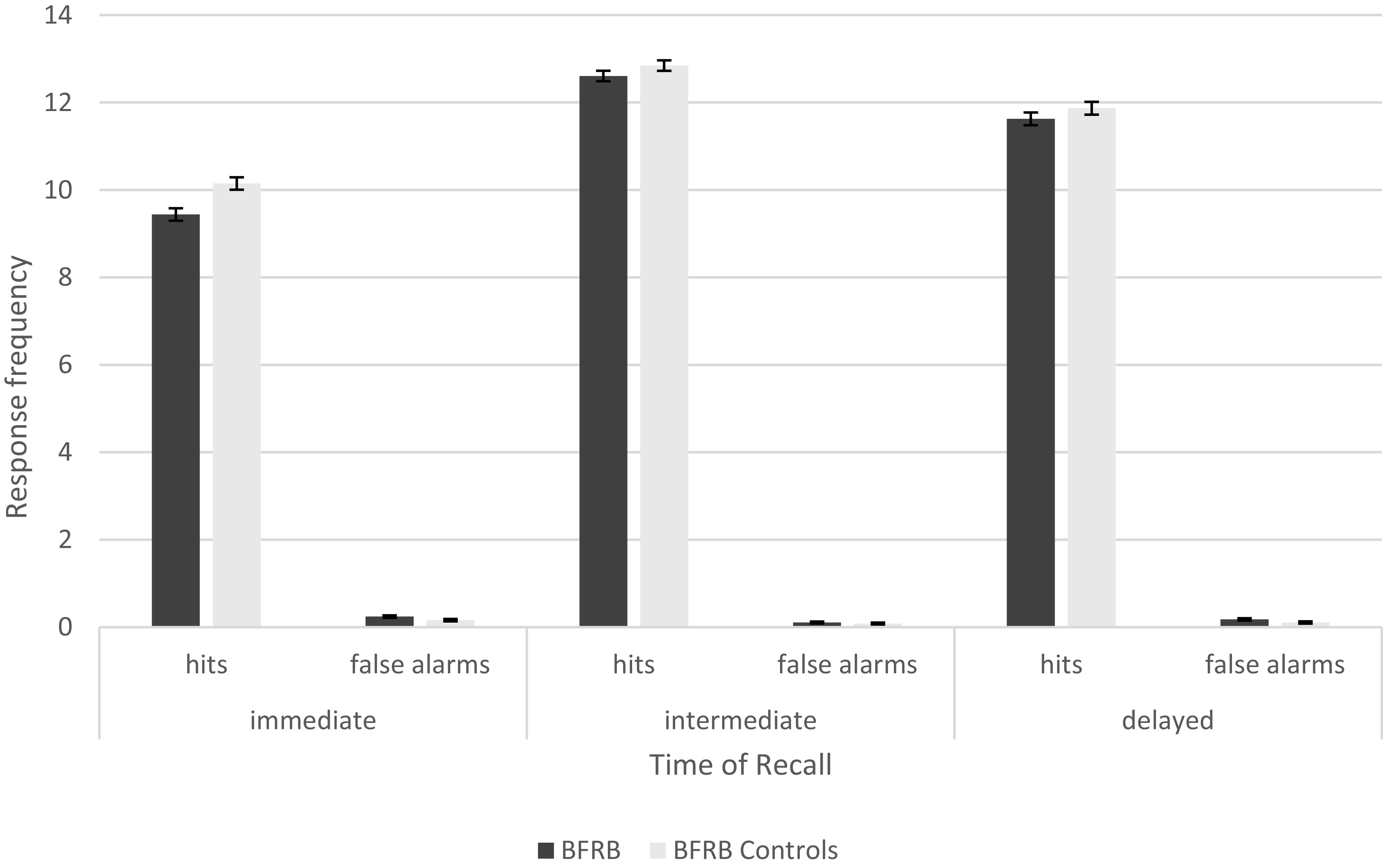

Verbal memory (VLMT), recall

We conducted a three-way ANOVA with Group (BFRB, controls) as the between-subject factor and Interval (immediate, intermediate, delayed), Memory Condition (hit, false alarms) as the within-subject factors, and VLMT recall (i.e., accuracy) as dependent variable. While the main effect of Group failed to reach statistical significance, F(1, 822) = 3.79, p = .052, ηp 2 = .005, all interactions involving Group as a factor achieved significance at a small effect size (at least p < .015, ηp 2 < .01). Figure 1 shows the three-way interaction, F(2,1644) = 7.35, p < .001, ηp 2 = .009). Individuals with BFRBs had fewer hits and more false alarms after the initial encoding (immediate recall) but did not differ from controls at the intermediate or delayed interval (see Table 3). When the sample was confined to those without psychiatric problems (except BFRB in the experimental group), the main effect again was not significant, F(1, 479 = 3.41, p = .065, ηp 2 = .007). Only the interaction of Group and Memory Condition remained significant, F(1, 479) = 5.42, p = .02, ηp 2 = .011, reflecting more hits in the control group and more false alarms in the BFRB group.

Figure 1. Immediate, intermediate and delayed responses on the Verbal Learning and Memory Test by group. Note. Learning performance (active recall).

We calculated the percentage of participants who fell at least one standard deviation below the mean of the control group for performance on the VLMT conditions. Impairment was observed in 16% of the BFRB group versus 11.2% in controls for immediate recall (χ2 (1) = 4.13, p = .042), 17.5% versus 17% for intermediate recall (χ2 = 0.03, p = .854), and 15.3% versus 15% for delayed recall (χ2 (1) = 0.01, p = .923).

Verbal memory (VLMT), recognition

We conducted a two-way ANOVA with Group (BFRB, controls) as the between-subject factor, Memory Condition (hit, false alarms phonetically, false alarms semantically) as the within-subject factor, and accuracy (VLMT recognition) as the dependent variable. Neither the main effect of Group, F(1, 8.22) = 0.90, p = .344, ηp 2 = .001, nor the interaction was significant, F(2, 1644) = 3.26, p = .059, ηp 2 = .004. The same applied to the subgroup analyses with no psychiatric disorder other than BFRB (main effect: p = .168, ηp 2 = .004; interaction: p = .144, ηp 2 = .004).

Verbal memory (VLMT), metacognition

For metacognition, we conducted a 2 × 4 ANOVA with Group (BFRB, controls) as the between-subject factor and Memory Condition (correct [hits, correct rejections]; incorrect [misses, false alarms]) as the within-subject factor. The number of high-confidence responses (parameter of metacognition) served as the dependent variable. While the main effect of Group was significant, F(1, 822) = 6.17, p = .013, ηp 2 = .007, reflecting a higher overall propensity of controls to make high-confidence responses, the interaction was not, F(1, 822) = 3.36, p = .0.67, ηp 2 = .004. As Table 3 shows, groups differed on only one of the six VLMT conditions capturing metacognition. Subgroup analyses with no psychiatric disorders showed similar findings (main effect: p = .043, ηp 2 = .005, interaction: p = .148, ηp 2 = .003).

Distraction and subjective neurocognition

Two thirds of the BFRB group reported no distraction by their BFRB symptoms during the trials. At a small to medium effect size, those with BFRBs reported self- or other-observed attentional difficulties. At a small effect size, more participants with self-reported BFRB than controls indicated memory problems as noted by others.

Subgroup analyses

The last column of each table reports comparisons of those with versus without certain BFRB subtypes. Nail biting (versus no nail biting) was more common in men than women; the opposite was true for skin picking. In particular, current skin picking and cavitadaxia were associated with more psychological symptoms. For neuropsychological variables, few significant differences emerged, and none achieved a medium effect size.

Correlations

For the BFRB group, we calculated correlations between the psychopathological scales (PHQ-9, OCI-R, GBS subscales, and total score) and the main neuropsychological parameters (Go/No-Go performance, comprised of hits minus false alarms; VLMT: hits for immediate, intermediate, and delayed recall, recognition hits, recognition high-confidence correct, recognition high-confidence incorrect). The GBS total score was negatively correlated with Go/No-Go performance (hits minus false alarms: r = −.117, p = .017). The GBS total score was also correlated with VLMT immediate false alarms (r = −.109, p = .028). Distraction by BFRB symptoms was negatively correlated with the following parameters of the VLMT: immediate correct (r = −.145, p = .003, intermediate correct (r = −.174, p < .001), delayed correct (r = −.138, p = .005), hit recognition (r = −.172, p < .001), and high-confidence correct recognition (r = −.149, p = .003).

In view of the evidence for subjective attentional problems in a subgroup of individuals with self-reported BFRB, we correlated subjective memory and attention problems (either based on their own or others’ observations) with the Go/No-Go task (hits minus false alarms), which were uncorrelated (r < .02, p > .9). However, self-reported attentional difficulties were correlated with depression (self-report: r = .499; others’ observation: r = .317; both p < .001).

Discussion

The literature on BFRBs such as trichotillomania and nail biting is marked by inconsistencies. Neuropsychological assessments have yielded mixed results in cognitive flexibility and motor inhibition, with most studies reporting deficits (e.g., Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ioannidis, Grant and Chamberlain2024; Barber & Lee, Reference Barber and Lee2025), whereas no impairment has been found for memory performance in most studies (e.g., Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ioannidis, Grant and Chamberlain2024).

Our study contributes to and extends this work by examining inhibitory control, attention, and memory in individuals with the whole spectrum of self-reported BFRBs. Our results indicate that patients with self-reported BFRBs do not have significant memory deficits. While those with BFRBs showed some deficits in immediate recall, they caught up at the intermediate and delayed recalls. We also found no substantial impairment in recognition compared to controls. As for metamemory, measured by confidence ratings, the control group showed a tendency to give high-confidence responses, irrespective of accuracy. However, significant results never surpassed a small effect size. These results align well with studies that have found no substantial memory impairments in this population (e.g., Ali et al., Reference Ali, Ioannidis, Grant and Chamberlain2024; Bohne, Savage, et al., Reference Bohne, Savage, Deckersbach, Keuthen, Jenike, Tuschen-Caffier and Wilhelm2005; Bohne, Keuthen, et al., Reference Bohne, Keuthen, Tuschen-Caffier and Wilhelm2005; Chamberlain et al., Reference Chamberlain, Fineberg, Blackwell, Clark, Robbins and Sahakian2007; Keuthen et al., Reference Keuthen, Savage, O’Sullivan, Brown, Shera, Cyr, Jenike and Baer1996; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Hannay and Breckenridge1997). There was some evidence that memory was impaired due to distraction from BFRB symptoms, again at a small effect size. According to Slikboer and colleagues (2018), BFRB trigger-relevant stimuli might be needed to evoke cognitive biases leading to memory deficits in BFRB, which could explain why we did not find any differences in memory between the BFRB group and healthy controls. This hypothesis awaits testing in future studies.

Regarding inhibitory control/attention, assessed with the Go/No-Go task, patients performed worse than controls overall, as indicated by their lower number of hits than the controls. However, only approximately every fifth individual with self-reported BFRB (20.1% versus 9.2% of the control group) exhibited scores more than one standard deviation below the mean of the control group. Of note, omission errors represent attentional lapses rather than inhibitory control per se (e.g., Meule, Reference Meule2017; Perri et al., Reference Perri, Spinelli and Di Russo2017), tentatively speaking against severe executive dysfunction in people with BFRB. While this seems to coincide with self-reports of attentional impairment in individuals with BFRB, objective and subjective impairments were uncorrelated in the current study, and the latter was somewhat associated with depression (for compatible findings, see Moritz et al., Reference Moritz, Ferahli and Naber2004). In sum, attention deficits were present in a subgroup but were not a pervasive feature in the BFRB group. Importantly, it should be mentioned that most previous studies on inhibitory control used the Stop-Signal Test instead of the Go/No-Go Task that was applied in this study. This might to some extent explain the divergent findings as the two tests are not fully redundant as they engage overlapping but distinct neural circuits (e.g., Raud et al., Reference Raud, Westerhausen, Dooley and Huster2020; Swick et al., Reference Swick, Ashley and Turken2011).

We consider the detailed analysis of the tests’ subdomains a considerable strength of this paper. Additionally, the association of the objective test results with the subjective assessment of the participants’ perception of their performance and of their metacognition provides novel insights into the neuropsychology of people with BFRB. It is, however, important to note some limitations of our study. While the online format allows for broad participation across diverse backgrounds, it also has limitations related to reduced control over data quality due to the self-report nature of the responses and no oversight during the neuropsychological assessment. Given the online self-report format of the study, we were unable to confirm the BFRB diagnosis using an independent rater. Although our sample size was large, some BFRB subgroups (e.g., cavitadaxia) were relatively small. A large number of participants (n = 738) provided unusable data, and of these n = 579 participants did not finish the neuropsychological assessment. The assessment was relatively long, and there was no financial incentive. However, we used a material incentive, which, according to Göritz (Reference Göritz2006), motivates people to start and complete a survey. This might explain our relatively low attrition rate (25%) compared to the results of Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Zhao and Fils-Aime2022), who reported an average online survey completion rate of 44.1%. The OCI-R and GBS-8 were not administered to the control group, who instead completed alternative questionnaires of equal length. Another limitation of our study is that we did not cover the entire spectrum of neurocognitive domains but focused on inhibitory control/attention and verbal memory. Especially since previous studies have found differing results in various neurocognitive domains for different subtypes of BFRB (e.g., Grant et al., Reference Grant, Odlaug and Chamberlain2011), the current study’s limited coverage of both BFRB subtypes and neuropsychological assessments restricts the generalizability of our results. Generalizability is further constrained by the online recruitment of the sample, which might differ in currently unknown ways from a clinical sample with confirmed diagnoses. For example, only a low percentage of patients with BFRBs (∼10%) seek treatment (Moritz et al., submitted). Thus, a clinical sample might not be representative of the actual BFRB population as clinical patients might score differently than the broader actual BFRB population on traits such as shame and perceived stigma. Moreover, the reported correlations were rather small, which is why the associations between the GBS score and the Go/No-Go Performance as well as the VLMT immediate false alarms should be interpreted with caution.

Future research should explore potential moderators of dysfunction such as motivation, disgust, and stress. For instance, patients may perform worse on neurocognitive tasks because they are distracted by BFRB urges or pain because of scars; this may be especially relevant when manipulating physical objects, as in the block design task. Our results point in this direction; distraction, however, was only captured with a single item. Self-stigma/defeatist beliefs could also play a role, as they do in individuals with schizophrenia (e.g., Chan et al., Reference Chan, Kao, Leung, Hui, Lee, Chang and Chen2019), leading patients to not make their best effort or give up prematurely. Understanding these mediators could provide deeper insights into the variability of cognitive impairments observed in BFRBs.

It is crucial not to overstate the neurocognitive deficits associated with BFRBs. While our study highlights the presence of attention problems in a small subgroup, the majority of patients did not exhibit substantial cognitive impairment. Whether deficits are primary or secondary has not yet been tested. Future research should focus on identifying the specific characteristics and mechanisms underlying the subgroup to better understand the heterogeneity within BFRBs. Additionally, longitudinal studies should explore whether neurocognitive deficits remain stable or vary with symptoms and/or stress, and how they affect the clinical course. Refining our understanding of these behaviors may help in developing more targeted and effective interventions.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author contributions

Steffen Moritz: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Lisa Borgmann: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Abud Alfawal: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Stella Schmotz: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Funding statement

None.

Competing interests

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.