Introduction

The ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East have caused major geopolitical shocks, prompting multiple states to recalibrate their grand strategies: long-term biases shaping how states define and pursue security.Footnote 1 Scholars agree that grand strategies rarely change but disagree on what triggers transformation. Some cite catastrophic events, whilst others stress path dependency and entrenched heuristics that inhibit change, even in the face of these event-types.Footnote 2

Ontological security scholars examine rhetoric after ‘critical situations’ to identify how leaders employ memories to contextualise the event.Footnote 3 Similarly, memory studies scholars argue that leaders employ historical analogies to justify and legitimise their chosen responses to traumatic events.Footnote 4 This resonates with the ‘strategic narratives’ literature, which posits that rhetoric can reveal a state’s grand strategy by delineating leaders’ long-term visions and how they propagate that vision.Footnote 5 Scholars have increasingly applied strategic narratives to understand when, how, and if a state’s grand strategy changes. Nevertheless, these outputs remain US-centric.Footnote 6 Further, despite the similarities with the trauma and ontological security literature as illustrated above, grand strategy and strategic narratives scholars alike rarely engage with these literature-sets.

This article addresses this gap and asks: how and to what extent do small states’ strategic narratives and grand strategies exhibit continuity or change after traumatic geopolitical events? It employs qualitative content analysis of leaders’ speeches in two small states – Israel and Czechia – following two distinct traumatic events: Russia’s February 2022 Ukraine invasion (Czechia) and the 7 October 2023 attacks (Israel). For both Czechs and Israelis, these events were significant external shocks that challenged each state’s ontological and physical security. Concurrently, the level of shock is dissimilar. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine unsettled many Czechs, but it was a distant event and a predicted – albeit a worst case – scenario.Footnote 7 Whereas Hamas’s attacks were an unexpected, direct attack within Israel’s borders.Footnote 8 This variance allows for comparative analysis to assess whether a more geographically distant shock precipitated a less significant grand strategic change and whether and how this manifested in leaders’ rhetoric.

This article illustrates that both critical situations engineered grand strategic shifts. However, the degree of change was proportional to the perceived level of shock and threat. Hamas’s attacks engineered a significant Israeli grand strategic overhaul. Czechia by contrast underwent a less substantial grand strategic adjustment. Concurrently, changes in strategic narratives reflected and enabled shifts in both states’ grand strategies. However, grand strategic change and continuity is not a binary. Israeli and Czech leaders advocated recalibrating their state’s grand strategies in response to each event. Yet to justify these changes, they also drew on existing rhetoric, analogies, and policies. For instance, in both cases, leaders invoked traumatic in-group events to contextualise the contemporary event and to therefore build legitimacy for a policy change. Thus, grand strategic continuity and change not only co-exist but are also co-dependent. This was the case in both Israel and Czechia, despite the divergences in the levels of trauma and the subsequent grand strategic shift.

This article makes several contributions by presenting new Israeli and Czech primary source data, extending grand-strategy analysis beyond great powers, and showing how rhetoric enables and constrains change. It begins by reviewing the grand strategy and strategic narratives literature. Subsequently, it delineates its case studies and methodology, which combines inference from the ontological security, memory studies, and grand strategy literature. It then employs this framework to analyse grand strategy and strategic narratives in Israel and Czechia. It subsequently compares this data to media reports, rhetoric, opinion polls, and policies from before each traumatic event and after the three-month period covered in the primary dataset. It ends by identifying the degree of grand strategic change and the role strategic narratives played in legitimising change in both cases.

Literature review

Grand strategy, strategic narratives, and ontological security

The study of grand strategy is changing. Traditionally, scholars limited the concept’s applicability to assessing how great powers employ force to counter systemic threats to their national security.Footnote 9 More contemporary approaches broadened grand strategy’s conceptual boundaries, to entail the study of why and how actors employ their resources inside and outside of wartime to achieve their goals.Footnote 10 The concept remains contested. Yet there is a relative consensus that grand strategy concerns long-term planning.Footnote 11 This spans how an actor views present, past, and future geopolitics, their vision for advancing their interests, and the tactics and tools they use to get there.Footnote 12

Scholars are increasingly cognisant of the great power centrism within the research programme of grand strategy. Recent works have argued that because they are particularly constrained by limited capabilities and face greater existential threats, small states need grand strategies more than great powers.Footnote 13 Small states may prioritise coalition-building; they may, conversely, ally with a hegemon and practice ‘derivative power’ by using their influence to shape the hegemon’s policies to better align with their own interests.Footnote 14 Others seek to exert disproportionate influence through international organisations such as the European Union or United Nations, projecting and maximising their individual and collective power for the same ends.Footnote 15

Corresponding to this conceptual broadening, a growing number of scholars have scrutinised elite rhetoric. Traditionally, scholars assessed a state’s grand strategy through official documents, whilst dismissing rhetoric as cosmetic.Footnote 16 More contemporary works argue that rhetoric reflects what tools of statecraft a state’s leaders advocate to advance its interests and what actions they deem legitimate.Footnote 17 Further, rhetoric reflects hegemonic perceptions within that state of how the international system is ordered and functions; it labels external actors as allies, rivals, or threats, providing policy prescriptions accordingly.Footnote 18 In short, rhetoric reveals three components of a state’s grand strategy: a socially constructed vision of its national interests; what foreign policy tools that state prefers to achieve these interests and in which situations; and who or what constitutes a threat and how to counter these threats.Footnote 19

The above dovetails with the literature on strategic narratives and ontological security. Rhetoric contains ‘strategic narratives’, which identify how states depict themselves and ‘the obstacles they face’.Footnote 20 Strategic narratives ‘promote specific collective values’ that a state seeks to advance, whilst identifying an in-group who share those values and an out-group who do not.Footnote 21 Similarly, ontological security scholars examine narratives to trace how a state’s sense of self-identity ‘constrains or enables states to pursue certain actions over others’.Footnote 22 Narratives contain perceived threats to not only a state’s physical security but also its ontological security: cognitive biases that engender continuity and establish and project a stable self-identity.Footnote 23 These biases are institutionalised through a state’s established routines, which sort friend from foe and perpetuate a policy path dependency. They therefore ‘create opportunities for action, as well as taboos that make certain action unimaginable’.Footnote 24

Recent works have employed assumptions from the ontological security, memory studies, and strategic narratives literature to produce insights into the study of grand strategy. One scholar claims that ‘grand strategy is […] an intention’ that becomes operational when leaders legitimise their policy preferences through strategic narratives.Footnote 25 Similarly, grand strategy is a two-level game, because leaders engage in ‘storytelling’, tailoring strategic narratives that justify their policy preferences to internal and external audiences.Footnote 26 They also draw on national memories to imply that their contemporary and future policy choices reflect long-term national interests.Footnote 27 Thus, strategic narratives ‘weave together past, present and future [and] such a narrative is constitutive of grand strategy’.Footnote 28 Elite rhetoric reflects a state’s ‘normative narrative’, which is a sine qua non for understanding consistencies in that state’s past, present, and future behaviour – its grand strategy.Footnote 29

Grand strategic shifts and ‘critical situations’

But one enduring debate that this conceptual synergy has not yet been applied to is the question of whether, how, and when grand strategy changes. Scholars largely agree that grand strategic shifts are rare. This is because grand strategy is inherently long-term and shaped by entrenched biases and worldviews that themselves are resistant to change.Footnote 30 But scholars have noted how shocking, unexpected external stimuli elicit grand strategic shifts more than any other input.Footnote 31 Others argue that grand strategies resist even these shocks.Footnote 32

Even those who agree that extraordinary events do elicit a grand strategic shift are divided over what outcome is more remarkable and salient: continuity or change. One scholar differentiates between grand strategic overhauls and grand strategic adjustments. The former occurs when a state adopts a new grand strategy, such as the US’s shift from containment to primacy. The latter occurs when a state alters its short-term tactics but not its long-term vision.Footnote 33 The Obama administration’s pivot to Asia, whilst retaining a grand strategy of primacy, is an example of this.Footnote 34 Another labels each categorisation a first or second order change respectively and posits that first order changes occur when a state faces a new threat; otherwise, a shock is likely to induce second order changes only.Footnote 35

Rhetoric-focused grand strategy made important contributions to this debate. They have illustrated, for instance, that US President Franklin Roosevelt consistently propagated a grand strategic shift within his rhetoric, but this alone was not enough; it took both Roosevelt’s legitimisation of grand strategic overhaul and the external stimuli of the Pearl Harbor attacks to engineer change.Footnote 36 Conversely, extraneous shocks are insufficient: grand strategic overhaul requires a combination of a shocking external event and leaders successfully legitimising their proposed policy changes through rhetoric.Footnote 37

The findings of ontological security and memory politics scholars also delineate important inference. Ontological security scholars argue that, by being unexpected and traumatic, ‘critical situations’ inherently challenge a state’s sense of self and others as formalised through institutionalised routines.Footnote 38 Thus, hegemonic perceptions, beliefs, and policy prescriptions appear at best flawed and at worst incorrect. Accordingly, political elites seek to respond with narratives that ‘provide comfort and relief’, by contextualising the event through familiar analogies.Footnote 39 In so doing, they seek to capture and communicate the magnitude of the event to internal and external audiences, by comparing it to widely acknowledged historical traumas.Footnote 40

But leaders’ invocations of traumatic pasts also serve a strategic end. By propagating or sustaining such an analogy, they are categorising the contemporary ‘critical situation’ within a case universe of past trauma.Footnote 41 This, in turn, justifies a significant policy shift, given that states rarely respond to trauma by carrying on as normal. Thus, trauma analogies are rarely passive and unintentional. Instead, leaders choose those historic episodes that most intensify emotional resonance or political urgency.Footnote 42

Correspondingly, leaders do not have carte blanche to invoke any memory or advocate any policy change. Instead, both must resonate within their audience’s collective memory.Footnote 43 They must therefore employ familiar framings to justify policy change. But these framings are equally constraining, because the policy change must conform to existing narratives to sustain a state’s sense of ontological security.Footnote 44 These findings infer that debates over grand strategic change often miss a fundamental commonality: that policy continuity and change not only co-exist but are also co-dependent.

Research design

Analytical framework

This article addresses grand strategy’s great power centrism and its lack of comparative studies, whilst contributing to the debate on grand strategic shifts. It analyses two small states – Israel and Czechia – and asks: to what extent do strategic narratives and grand strategies exhibit change or continuity after a traumatic externally induced event?

This article assumes that strategic narratives reflect grand strategy and how it is ‘sold’ to internal and external audiences as a long-term plan to enhance and maintain a state’s physical and ontological security. It unpacks the research question above by answering two secondary questions: if an unexpected event induces a policy shift, how extensive is this change, and to what extent is it enabled by and reflected in strategic narratives? It examines Israeli and Czech grand strategy (policies) and strategic narratives (rhetoric) both before and after a traumatic event. It categorises policy and narrative change as either a grand strategic adjustment (tactics and means, such as tools of statecraft), or a grand strategic overhaul (goal and vision, such as a shift from a revisionist to a status quo power or vice versa).

There exists a relative consensus as to what characteristics these event-types share. One grand strategy scholar argues that ‘high impact events, which were either assigned a low probability or unforeseen completely’ are a necessary condition for undoing the ‘psychological or institutional inertia’ that precludes grand strategic change.Footnote 45 Another defines them as ‘rapidly changing external conditions sufficiently shocking to disconfirm the assumptions of the status quo’.Footnote 46 One ontological security scholar suggests that ‘critical situations’ are ‘so shocking and unexpected that they disturb the “institutionalized routines” of states’.Footnote 47 But none of these literature-sets have sought to compare degrees of ‘critical situations’. To address this literature gap, this article examines two case studies that both contain ‘critical situations’ of divergent order and magnitude. It asks a further secondary question: does a first order critical situation induce a greater extent of grand strategic disruption than a second order critical situation?

Concurrently, this article focuses on elite rhetoric, because it is a state’s leaders who possess the most agency to justify and operationalise their policy preferences.Footnote 48 This is particularly true after ‘critical situations’, when strategic narratives are at their most salient within leaders’ rhetoric.Footnote 49 This is because shocking and unexpected events are often traumatising in the physical damage they cause and/or because they apparently invalidate a collective sense of routine or ontological security.Footnote 50 Thus, ‘publics are eager for someone to step forward to make sense of confusing global events […] public demand for storytelling is elevated’.Footnote 51

Leaders attempt to meet this demand by tailoring their rhetoric to internal and external audiences; as such, they employ multiple and sometimes contrasting framings to illustrate they understand the magnitude of the event and what actions need to be taken in response. In these situations, strategic narratives ‘reveal leaders’ assertions of causality, how they understand the event, their classification of the involved parties as either victims or perpetrators and their proposed policy responses’.Footnote 52 Leaders construct a ‘case narrative’ that illustrates how states understand themselves, the actor that caused the critical situation, and the critical situation itself.Footnote 53

Analysing leaders’ rhetoric can therefore identify: (i) a state’s geopolitical vision and long-term goals; (ii) preferences for particular tools of statecraft to achieve those goals; (iii) whether they categorise other actors as rivals, threats, or allies; and (iv) how a state defines itself and others in the international system. After a critical situation, strategic narratives also contain: (v) a state’s understanding of what caused the event; (vi) how that event affects a state’s self-identity; and (vii) what policies it should pursue in response. This article identifies to what extent the critical situations that Israel and Czechia faced precipitated their leaders’ to either advocate new policies and goals and to reconsider their beliefs, or to contextualise the event within existing biases and respond to it via existing policy choices. In each of the categories above, this article draws on the existing scholarly literature and primary sources to identify Israeli and Czech grand strategy before the event in question. It then examines leaders’ speeches after the event to trace continuity and/or change through qualitative content analysis.

Case selection

Strategic narratives are particularly salient in democracies, given that leaders must justify their prescriptions to their voters.Footnote 54 Equally, though great powers often delineate strategic narratives in official documents, small states rarely do so.Footnote 55 This makes analysing leaders’ rhetoric to identify strategic narratives and a state’s grand strategy an appropriate framework for a comparative case analysis of Israel and Czechia. There are very few English-language academic outputs that examine Czechia’s foreign and security policies, let alone its grand strategy. The publications that do exist are largely dated.Footnote 56 By contrast, studies of Israeli foreign, domestic, and security policy proliferate, but there are surprisingly few works on either its grand strategy or its strategic narratives.Footnote 57

This article analyses Israeli and Czech strategic narratives during two contemporary conflicts: the Hamas-led incursion into Israel on 7 October 2023 leading to the subsequent Gaza war; and Russia’s Ukraine invasion from 22 February 2022. Both are transformative and geopolitical events. Their shocking nature is illustrated by their death tolls: over a million in the Russia/Ukraine war and over 50,000 in the Israel/Gaza war.Footnote 58

Israel experienced the largest loss of life in one day in its history on 7 October 2023. The attacks were an intelligence failure that constituted an ‘unbearably difficult trauma’, with Israel ‘still grieving’ one year later.Footnote 59 By contrast, multiple intelligence agencies predicted Russia’s Ukraine invasion of 22 February 2022. Nevertheless, the invasion created an acute sense of insecurity in Czechia and was a traumatic ‘foreign political shock’.Footnote 60 Given their geographical location, many Czechs felt the invasion was taking place in their backyard. Worse still, that the Soviet Union had previously invaded, occupied, and imposed its own political system on Czechoslovakia made the threat appear even more direct and salient.Footnote 61 Accordingly, this article categorises the October 7 attacks as a first order critical situation for Israel, given the unexpected and direct nature of that incident. Russia’s February 2022 Ukraine invasion was, by contrast, a second order critical situation for Czechia, given that it was both (at least partially) predicted by major western intelligence agencies and took place outside that country’s borders.

Israel and Czech grand strategies and strategic narratives pre-critical situation

Israel and Czechia are two very different countries in two very different geopolitical milieu. Israel perceives itself to be in a ‘tough neighbourhood’ defined by violent conflict.Footnote 62 Force-centrism and unilateralism have long underpinned Israel’s grand strategy; relatively hawkish and dovish leaders alike have embraced the ‘iron wall’.Footnote 63 This approach to foreign and security policy affirms that normal regional relations are impossible until the Arab world reconciles itself with Israel’s existence. The only way Israel can expedite this is by prioritising military force.Footnote 64 This is because regional actors will only consider coexistence after they acknowledge the strategic inefficiency of violence. Hence Israel spends a higher percentage of its GDP on military expenditure than Russia and every NATO member state.Footnote 65

Israel often finds itself subjected to international criticism. Israelis, in turn, feel like the international community does not understand them.Footnote 66 But, in the words of Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, ‘what matters is not what the gentiles think, but what the Jews do’.Footnote 67 Israel should not waste time on prolonged diplomacy or alter its policy in response to criticism from international organisations; Ben-Gurion described the United Nations as worth ‘nothing’.Footnote 68 What matters instead is decisive, unilateral (often military) action and the creation of ‘facts on the ground’ that advance Israel’s long-term interests, by ensuring its survival when faced with existential threats.Footnote 69

Whilst this attitude appears anathema to the rules-based world order, Israel has long framed itself as a western nation. Israel’s strategic narratives have long claimed it constitutes ‘the only democracy in the Middle East’: an outpost of stability in a violent region.Footnote 70 Israel enjoys a ‘special relationship’ with the United States, from whom it receives more military and economic aid than any other country. Israel’s leaders rationalise this relationship as the product of shared interests and values.Footnote 71 These span common adversaries – such as Iran, Hezbollah, and other revisionist actors within the self-proclaimed ‘Axis of Resistance’ – alongside mutual appreciation for democracy and freedom.Footnote 72

By contrast, Czechia enjoys a privileged position in central Europe, one of the most conflict-free regions in the world.Footnote 73 Whilst Israel feels regionally isolated, Czechia has found itself torn between two geographical poles: East and the West. After the Second World War, the Soviet Union imposed its answer to this question upon Czechoslovakia. Since the end of the Cold War, Czechoslovak and – since 1993 – Czech grand strategy have reflected a national identity that has stressed its sovereignty and independence. Czech diplomats emphasise the country’s home-grown secular liberalism and historical-cultural commonalities with western Europe.Footnote 74 Czechia’s self-identification as a liberal democracy committed to a rules-based international order and the promotion of human rights is rooted in a reimagining of its past. Czech strategic narratives frequently invoke humanist figures like Czechoslovakia’s first president, T. G. Masaryk, and Czechia’s first post-communist leader, Václav Havel.Footnote 75

Post–Cold War Czechia has lacked an agreed external state-level threat. Political debates traditionally concerned domestic issues, not foreign policy.Footnote 76 Czechia’s 2015 National Security Strategy (NSS) did not name any rival and determined that the probability of invasion was very low.Footnote 77 Since Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia and 2014 annexation of Crimea, sections of Czech opinion increasingly perceived Russia to constitute a growing threat. But until 2022 this was far from a consensus view.Footnote 78 Czechia remained reliant on Russian gas and oil. Key figures from Czechia’s governing elite – notably President Miloš Zeman – advocated closer ties to Russia.Footnote 79

Whilst Czechia is, like Israel, a small state, it seeks to mitigate this disadvantage very differently. Czechia prioritises soft power, such as by offering its experience of transition from communism to liberal democracy as a model for other nations.Footnote 80 Having ended military conscription in 2004 and with its defence spending remaining lower than 2 per cent of its GDP from the 1990s to 2024, Czechia lacks Israel’s force-centrism.Footnote 81 Instead, Czechia’s armed forces have long complained of being under-funded.Footnote 82 Czechia has deployed its armed forces abroad on multiple occasions, but these have always been as part of a multinational mandate.Footnote 83 This illustrates Czechia’s third grand strategic pillar: embedding itself in international organisations as a force multiplier to increase its influence and agency. Czechia joined NATO in 1999; it later acceded to the EU in 2004.Footnote 84

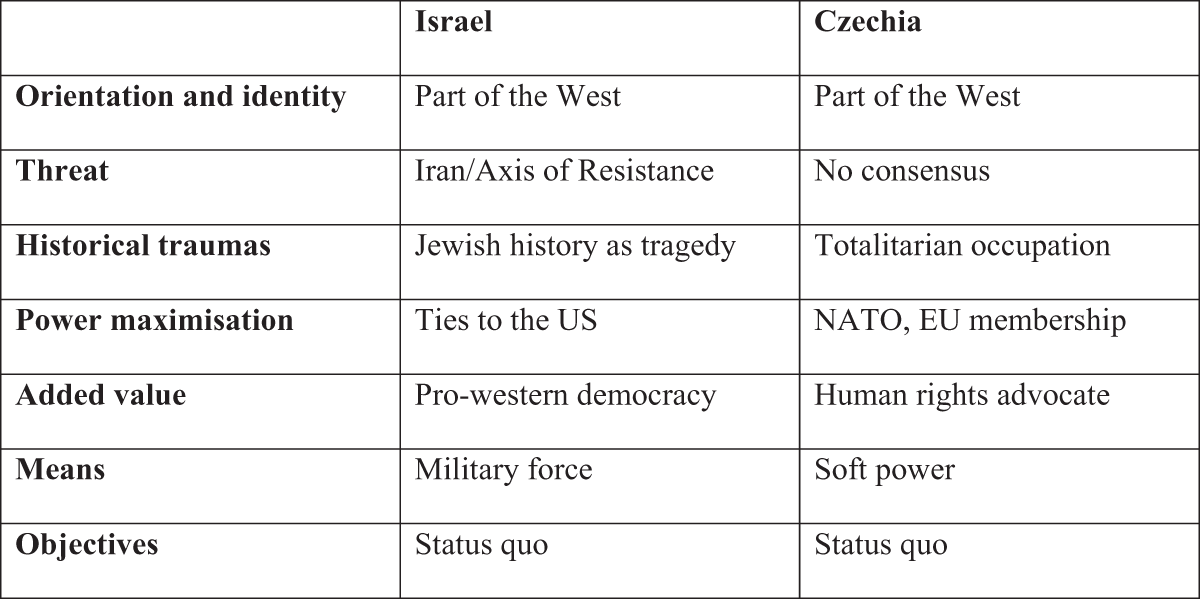

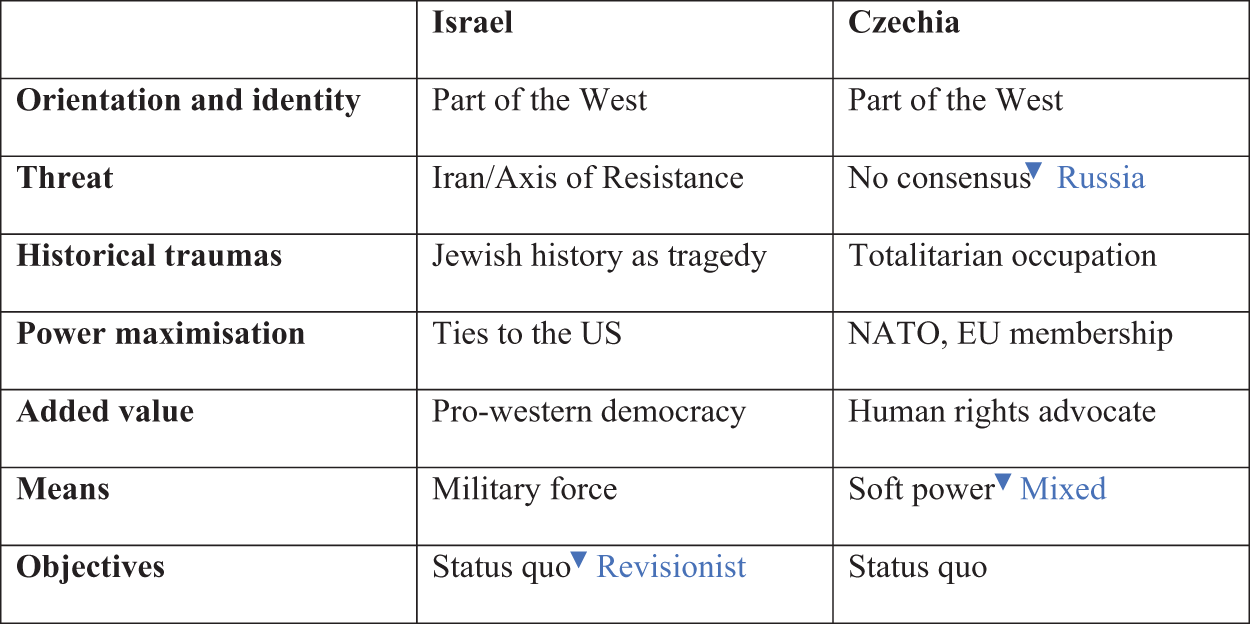

These divergences notwithstanding, Figure 1 illustrates both countries’ grand strategic commonalities. Both see themselves as part of ‘the West’ and are traditionally status quo powers. Both states’ leaders draw on historical trauma to contextualise contemporary geopolitics. Czechia employs its focus on liberal democracy and human rights to advance its national interests, but this is in turn the product of its traumatic past under totalitarian regimes. Israel’s leaders, from Menachem Begin in the 1980s to Ariel Sharon in the early 2000s and Netanyahu today, have frequently enjoyed the Nazi moniker to refer to regional rivals. They have also evoked traumatic Jewish memories, such as pogroms and the Holocaust, to justify Israel’s force-centric response to these regional threats.Footnote 85

Figure 1. Comparing Israeli and Czech grand strategy pre-critical situation.

Measuring grand strategic change through strategic narratives

This article identifies (i) if and to what extent Israeli and Czech strategic narratives and grand strategies changed in response to a critical situation and (ii) how leaders employed new and existing strategic narratives to justify grand strategic change or continuity. It employs a dataset of 224 Israeli and 72 Czech leaders’ speeches. The divergence in number of speeches likely corresponds to the perception of the threat. Israel endured a first order critical situation, whereas Czechia faced a second order critical situation. The date range for both datasets was up to three months after the event: 22 February 2022–22 May 2022 (Czechia) and 7 October 2023–7 January 2024 (Israel). To minimise potential selection bias, we included all available speeches by key politicians during the period under review, collected from their personal websites as well as from the websites of the institutions and political parties they represent. Given the substantially smaller volume of data on the Czech side, we supplemented the public speeches with leading politicians’ newspaper interviews retrieved from the Newton One database. Additionally, to balance the comparatively small size of the Czech dataset, a control sample of ten media comments from the same period was used to verify that these findings were not limited to a narrow group of leaders.

This article focuses on the figures within each country’s political system with the most executive power. Thus, the Israeli dataset includes speeches by the prime minister (Benjamin Netanyahu), defence minister (Yoav Gallant), foreign minister (Eli Cohen), and president (Isaac Herzog). The Czech dataset included the prime minister (Petr Fiala), president (Miloš Zeman), foreign minister (Jan Lipavský), and defence minister (Jana Černochová). To minimise potential selection bias, we included all available speeches by these key politicians during the period under review. These were collected from their personal websites as well as from the websites of the institutions and political parties they represent.

Scholars have identified four key components of grand strategy that manifest in rhetoric: (i) identity; (ii) international environment; (iii) means to work towards an overall purpose; and (iv) overall purpose.Footnote 86 This article modifies this framework for critical situations by adding an additional category that examines how the event itself is framed. It applies this framework to delineate the following themes:

(i) Event and threat: How leaders’ rhetoric describes the traumatic event; what rhetoric is employed to describe the antagonist that precipitated the trauma.

(ii) Identity: How a state defines itself and how this relates to the event.

(iii) International environment: How broader geopolitics corresponds to the traumatic event and the state’s interpretation of that event.

(iv) Means: the tools of statecraft that leaders prioritise and justify in response.

(v) Overall purpose: what a state is seeking to achieve and how a traumatic, externally induced event influences its pursuit of those long-term political objectives.

We employed these five categories as the foundation of our deductive coding scheme, which served to classify statements made by individual politicians. To ensure coding consistency and intercoder reliability, a comprehensive codebook with a clear definition of parent and child codes was created and the data was coded in a two-step process in NVivo. All coding decisions were documented and coding rules were applied consistently across both cases.Footnote 87

To locate the relevant passages within the texts, the Word Frequency Query function in NVivo was employed to identify the most frequently occurring expressions, nouns, and concepts. These passages were subsequently assigned to individual codes derived from our deductive scheme. After coding 10 per cent of the speeches, we reviewed the procedures of both coders. Where disagreements arose, these were discussed until consensus was reached, and the codebook was adjusted accordingly to prevent recurrence.

During this procedure, the five concept-driven parent codes were supplemented with inductively derived child codes, which captured the identified most common aspects within each respective area (e.g., within the category of means, specific tools of statecraft such as diplomacy, military measures, or sanctions). To further mitigate any potential bias and identify any coding errors or discrepancies, this article was peer reviewed in multiple scholarly fora. We reflected on our positionality as researchers with expertise in the cases analysed and sought to mitigate any interpretive bias through peer debriefing and transparency in coding decisions.

By breaking down the results of our coding by the five components of a state’s grand strategy delineated above, the analysis below identifies the most salient analogies, actors, or themes that Israeli and Czech leaders invoked. The text delineates – in percentage form – how many speeches they appeared in. The corresponding figures illustrate the three mode references per category and the total number of speeches that these references appeared in.

Israeli and Czech strategic narratives post-critical situation

Event and threat

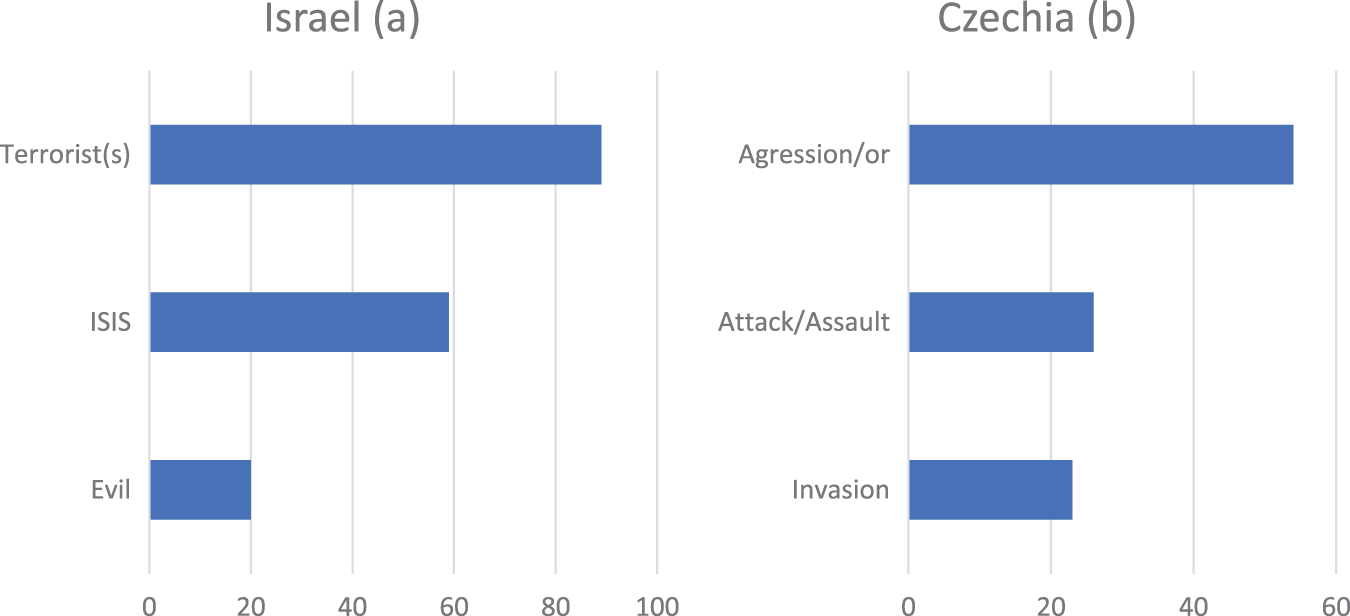

As Figure 2 illustrates, Czech leaders unequivocally denounced Russia’s Ukraine invasion as ‘aggression’ in 75 per cent of the sampled speeches and employed adjectives such as ‘barbaric’ (in 11 per cent of the sampled speeches). Czech leaders labelled Putin as a ‘bandit’, ‘terrorist’, ‘war criminal’, ‘tyrannical’, and ‘insane’, whilst Czech media denounced Russian policy and deemed Putin ‘pure evil’.Footnote 88 Israel’s leaders, in turn, condemned the October 7 attacks as a ‘war crime’ and ‘massacre’. They emphasised civilian victims: these spanned children (in 29 per cent of the sampled speeches), women (13 per cent), and babies (6.7 per cent). By contrast, they only referenced adult male victims in 2 per cent of speeches, even though they accounted for over 50 per cent of fatalities.Footnote 89 Surprisingly, Israel’s leaders prioritised delegitimising Hamas through contemporary rather than historical in-group analogies: 26 per cent of speeches referred to Hamas as ‘ISIS’ whilst 6 per cent employed the ‘Nazi’ moniker; a frequently recurring term was ‘Hamas–ISIS’, implying there was no distinction between these groups.

Figure 2. Top Three Israeli framings of Hamas and October 7 (a) and Czech framings of Russia’s and its invasion of Ukraine (b); speeches (N).

Identity

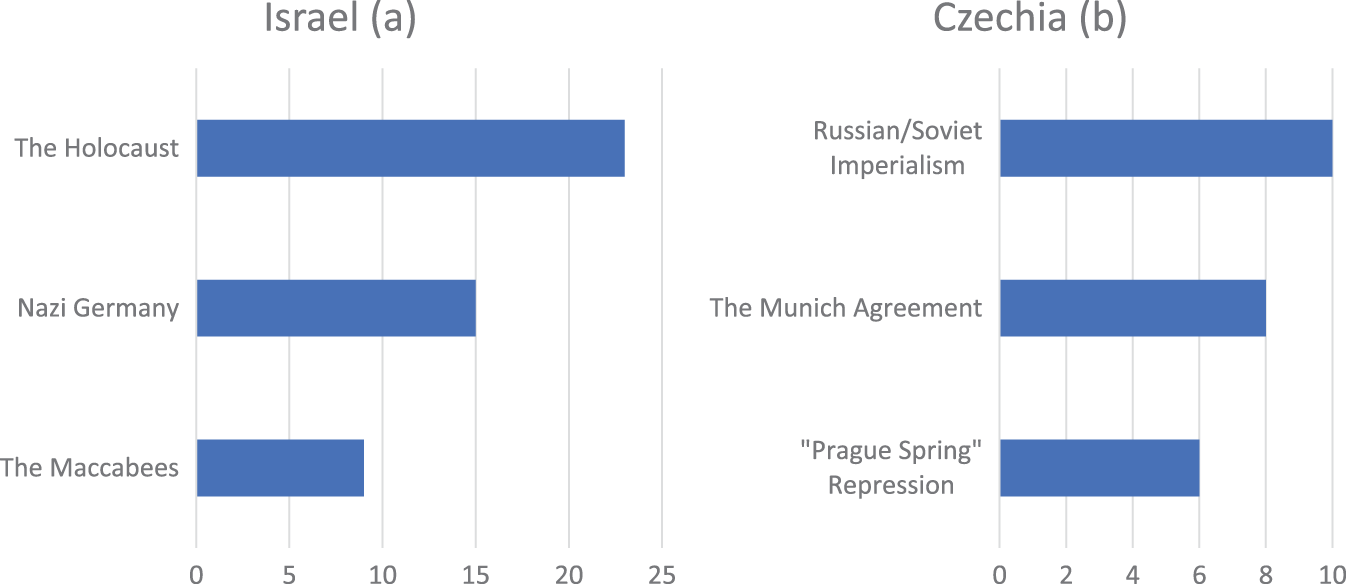

Israel’s strategic narratives contextualised the October 7 attacks and justified the country’s response via Jewish historical-religious themes; the word ‘Holocaust’ appears in 10 per cent of speeches (see figure 3), whilst 13 per cent of speeches invoked God. Of these, 91 per cent were made by Netanyahu, who called on God to bless Israeli soldiers, curse their enemies, and pray for victory. Netanyahu frequently referenced the Maccabees, an ancient Jewish warrior priest dynasty. This was partly because the dataset coincides with Hannukah, the Jewish holiday when the Maccabees are remembered. But Netanyahu also invoked the term to compare Israel’s contemporary armed forces, who were fighting against Hamas, to the ancient dynasty who fought against the Seleucid empire. Two complementary themes also repeatedly manifested in the Israeli dataset. First, 44 per cent of speeches claimed that Israel is part of the ‘civilised world’. Second, Israel is fighting on behalf of the ‘civilised world’, who must support it. In 7 per cent of speeches, Israel’s leaders claimed that if they failed to do so, ‘the West’, or Europe, ‘will be next’.

Figure 3. Top three references to Jewish (a) and Czech (b) history; speeches (N).

The Czech dataset lacked religious analogies but contained comparatively salient invocations of democracy. The word ‘democracy’ appears eight times in the Israeli dataset and refers primarily to other countries. By contrast, 27 per cent of speeches in the Czech dataset described Czechia as a democracy. Czech leaders argued that EU and NATO membership safeguarded their country’s liberal democratic values.Footnote 90 Correspondingly, 32 per cent of speeches referenced Czechia’s membership of ‘the West’. But the dataset also stressed Czech cultural and political similarities to Ukrainians, with the word ‘solidarity’ appearing in 32 per cent of speeches. Similarly, one of the sampled news articles claimed that ‘by helping Ukraine, we will help ourselves’.Footnote 91 Czech leaders invoked memories of Soviet imperialism to describe Russia’s contemporary actions in 14 per cent of the dataset. Their speeches frequently mentioned the Soviet incursion of 1968 and the subsequent violent repression of the ‘Prague Spring’ reforms, which featured in 8 per cent of speeches. Similarly, the 1938 Munich Agreement featured in 11 per cent of speeches. Identical analogies also frequently appeared in newspaper commentaries.Footnote 92

International environment

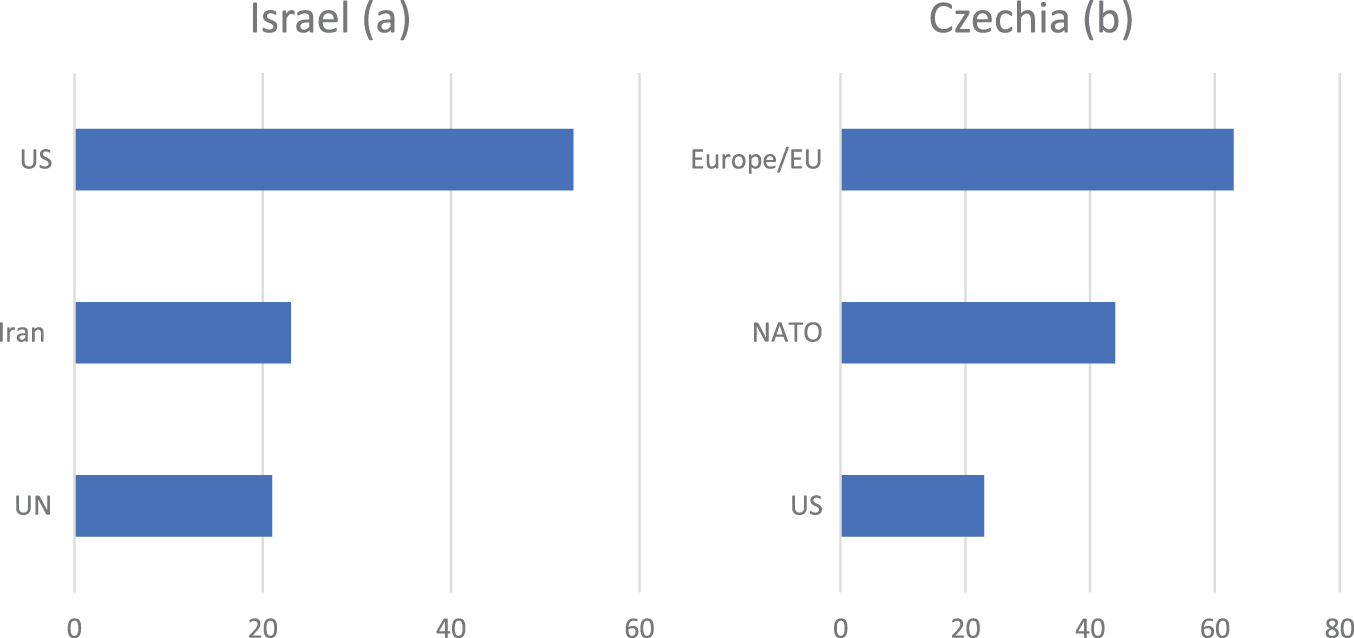

As Figure 4 illustrates, Israel’s leaders repeatedly contextualised the October 7 attacks within a broader regional conflict. Iran was referenced in 10 per cent of speeches. They argued that it was Iran, not Israel and its ‘moderate Arab’ partners, that impedes regional stability.Footnote 93 But, ‘moderate Arabs’ did not include the Palestinian Authority, who were only referenced in 4 per cent of speeches and depicted as impediments to peace.Footnote 94 Conversely, 24 per cent of speeches stressed the US–Israel ‘special relationship’. Beyond the Middle East and the United States, the most-referenced region is Europe, featuring in 8 per cent of speeches. The UN featured in 9 per cent of speeches. These references range from invoking UN resolutions to illustrate Israel’s compliance with international law, to condemning the UN for its purported bias; Herzog even argued that it was the UN – not Israel – that precipitated Gaza’s humanitarian crisis.Footnote 95 Overall, each of these references conformed to existing Israeli strategic narratives. In short, the country’s strategic narratives have long perceived Iran as Israel’s pre-eminent regional foe and the United States as Israel’s most important ally and great power guarantor, and exemplified Israel’s fractious relationship with the UN.Footnote 96

Figure 4. Top three actors/regions in Israel (a) and Czechia (b); speeches (N).

Whilst 32 per cent of Czech speeches referenced the US, Europe and NATO took precedent and featured in 92 per cent and 61 per cent of speeches. These were invoked for similar purposes as Israel’s leaders referenced the United States: to illustrate Czechia’s geopolitical orientation, stress a shared purpose, and portray a Russian defeat as synonymous with western interests.Footnote 97 Czechia’s strategic narratives also invoked the invasion to justify several policy shifts. Firstly, Czech leaders criticised ‘the West’ for its lacklustre response to previous Russian irredentism.Footnote 98 Similarly, one of the sampled articles urges to ‘remember the Czech politicians who contributed towards this global catastrophe [by appeasing Russia]’.Footnote 99 Second, despite Germany not being a traditional preferred partner for Czech security cooperation, it was referenced in 25 per cent of speeches as ‘a key neighbour, a key partner’.Footnote 100 Third, 7 per cent of speeches justify a US–Czech defence agreement – a new bilateral treaty – as a necessary response to Russian expansionism.

Means

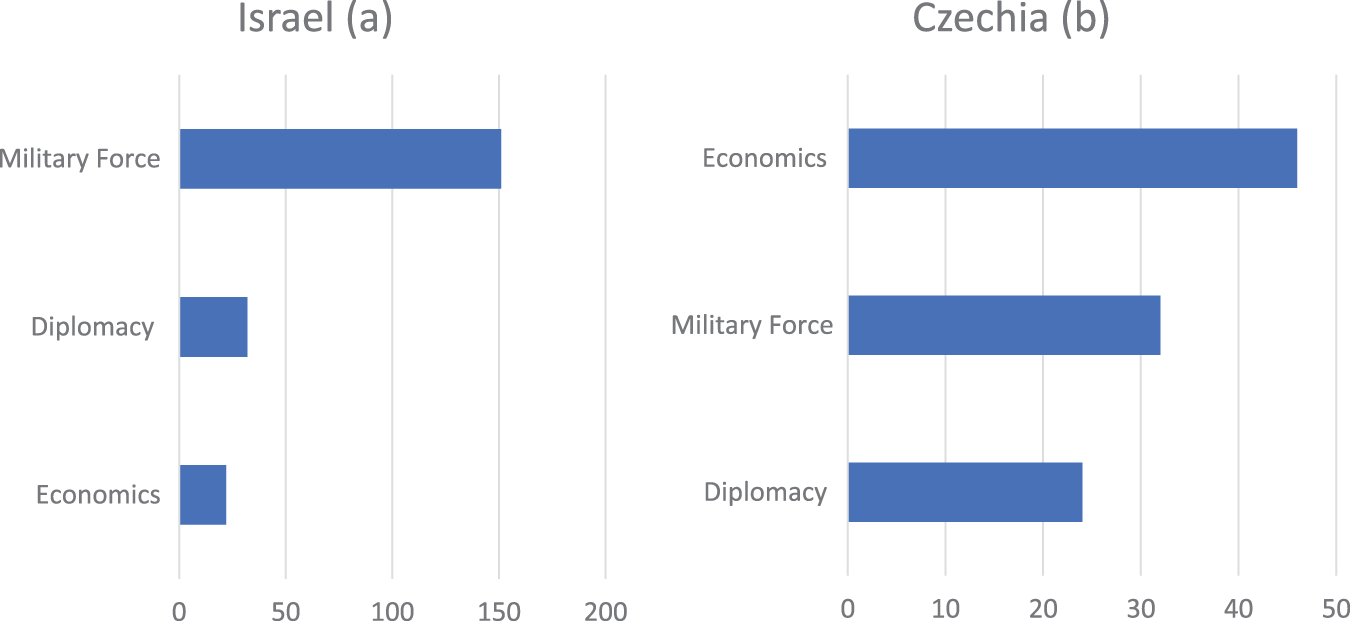

Military force was Israel’s most frequently referenced tool of statecraft, invoked in 67 per cent of speeches, whilst diplomatic and economic measures feature in 14 per cent and 10 per cent of speeches (see Figure 5). The words ‘soldier(s)’ and ‘war’ appear 154 and 418 times, whereas ‘ceasefire’ appears only 18 times. Herzog was the exception to the force-centric rhetoric and repeatedly stressed that ‘we are not fighting the people of Gaza’.Footnote 101 He was also responsible for 63 per cent and 75 per cent of all uses of ‘humanitarian’ and ‘aid’ in the dataset. Only 3 per cent of speeches address rebuilding and rehabilitating the territory and residents harmed on October 7, suggesting that Israel’s focus remained on military force. The only exception was the conflict with Hezbollah on Israel’s northern border, where officials preferred diplomatic means.Footnote 102 This is on the one hand unsurprising, because of the unprecedented strategic shock and loss of life that Hamas’s attacks caused. But it also conforms to pre-existing Israeli grand strategy preferencing the use of force as the country’s primary tool of statecraft.Footnote 103

Figure 5. Top three tools of statecraft in Israel (a) and Czechia (b); speeches (N).

The Czech dataset comparatively lacks force-centrism. Though 44 per cent of speeches invoked military means, Czech leaders rejected using force against Russia. Instead, economics are the mode tool of statecraft, featuring in 63 per cent of speeches. Czechia’s leaders advocated economic assistance for Ukraine, Ukrainian refugees, and for Czechs hurt by skyrocketing energy bills.Footnote 104 The belief that supporting refugees and aiding war-torn Ukraine aligns with Czechia’s strategic interests was shared by periodicals on the political left and right alike.Footnote 105

Czechia’s leaders argued that the country required a greater focus on energy independence and military spending.Footnote 106 They also advocated that the international community adopt ‘the toughest possible sanctions’ against Russia.Footnote 107 There was, however, a consensus to keep Russia and Czechia’s embassies in Prague and Moscow open to maintain bilateral ‘channels of communication’.Footnote 108

Overall purpose

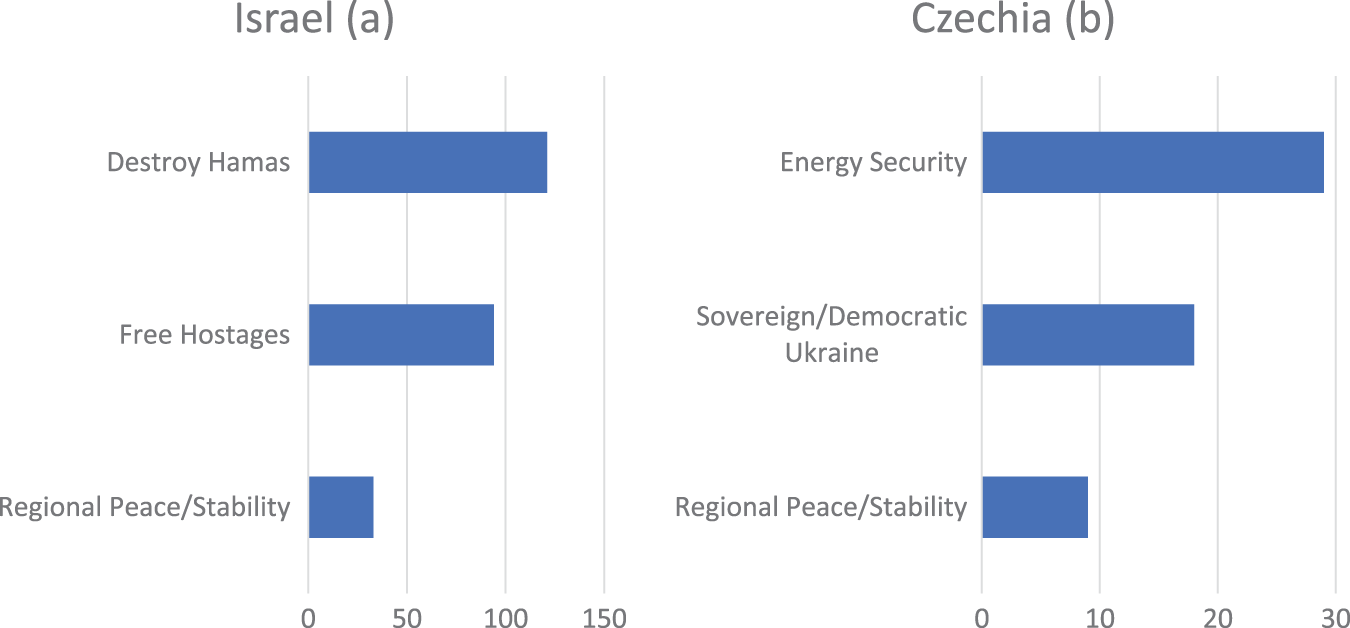

Figure 6 demonstrates that Israel’s strategic narratives demonstrated a consistent primary objective: destroying Hamas, which featured in 54 per cent of speeches. The words ‘eliminate’, ‘destroy’, and ‘defeat’ appear 118, 91, and 43 times respectively.Footnote 109 By contrast, ‘peace’ appears forty-nine times and a goal of regional peace and/or stability featured in 15 per cent of speeches. When peace and stability were invoked, these were primarily the articulated result of Israel’s war against Hamas. In short, Israel’s strategic narratives suggest that it would achieve regional peace or stability only through confronting Hamas with military force and comprehensively defeating the group. In 12 per cent of speeches, Israel’s leaders propagated an existential narrative: the conflict was ‘our second war of independence’; Israel had to ‘destroy’ Hamas to secure its own future.Footnote 110 The second consistent objective was freeing Israel’s hostages from Hamas captivity, which featured in 42 per cent of speeches; the word ‘hostage/s’ appears 200 times.

Figure 6. Top three goals in Israel (a) and Czechia (b); speeches (N).

Czechia’s leaders were united in their overall purpose: facilitating a ‘free, secure and democratic Ukraine’.Footnote 111 Whilst they sought to return Ukraine to its pre-war status quo, Czechia’s leaders argued that Russia’s invasion meant that their own country had to become more self-sufficient. This included military modernisation and increasing defence spending to 2 per cent of GDP.Footnote 112 Czech leaders called for the country to end its dependence on Russian oil and gas, which 40 per cent of speeches framed as a threat to national security. Fiala, for instance, advocated that Czechia pivot towards long-term investment in nuclear energy and revise its previous emphasis on green energy to achieve ‘energy security’.Footnote 113 Zeman even proposed that the EU reconsider its ‘Green Deal’ policy to advance this end.Footnote 114

Continuity and change in Israeli and Czech grand strategy

Israel

As early as 2010, Netanyahu described Iran as the head of an ‘octopus’ of ‘extremist Islam’, which ‘sends out its tentacles in the form of Hamas and Hezbollah’.Footnote 115 This illustrates that Israel’s consistent declared primary threats have been the Iranian-led ‘Axis of Resistance’, which includes state-level Islamist threats (Iran) and violent non-state Islamist actors (Hamas and Hezbollah). In 2014, Netanyahu argued that ‘Hamas is ISIS’ and likened both groups to the Nazis.Footnote 116 Netanyahu’s rhetoric reflected long-term trends in public opinion; polling from as early as 2004 illustrated that Iran was the most salient perceived threat to Israel’s interests and even its survival.Footnote 117 It is, therefore, unsurprising that 73 per cent of Israelis supported the government’s subsequent decision to directly attack Iran in June 2025; over 60 per cent of Israelis believed that the war should continue until the Iranian regime collapses.Footnote 118

The October 7 attacks led Israel’s leaders to propagate these existing strategic narratives. After the Hamas-led attacks, Israel’s leaders referred to ‘Hamas–ISIS’ who were puppets, ‘directed by their proxy commanders in Iran’.Footnote 119 They were also part of an Iranian-led ‘empire of evil’, who ‘want to return the Middle East to the […] barbaric fanaticism of the Middle Ages’; thus, ‘just as the civilized world united to defeat the Nazis [and] ISIS, the civilized world has to stand united behind Israel to defeat Hamas’.Footnote 120

Equating Israel to ‘the civilised world’ exemplifies the long-term strategic narrative that anchors the country within ‘the West’. This recurred after October 7 to justify Israel’s policies and rally support against its rivals. The country’s leaders implored that the international community ‘stand with Israel. Stand with civilization’, otherwise ‘the west will be next’.Footnote 121 Herzog stated that ‘never again is now’, implying that October 7 tested the international community’s intent to prevent a future Holocaust.Footnote 122 Netanyahu suggested that ‘the civilized world’ comprised ‘[Israel], the moderate Arabs, the United States [and] Europe’; this coalition was ‘the allies’, in contrast to ‘the new Nazis’: Hamas, Iran, and Hezbollah.Footnote 123 This conforms to the grand strategic patterns of other small states, who often seek to leverage their strategic location or align themselves with a powerful coalition.Footnote 124

Concurrently, Israel’s leaders employed the long-term framing of Jewish history as tragedy to contextualise October 7. Netanyahu described Hamas as ‘evil’ and a ‘genocidal terrorist cult’ who seek to ‘kill all the Jews’.Footnote 125 He claimed that: ‘like Anne Frank, Jewish children hid in attics from these monsters […] as in Babi Yar, Jews were machine-gunned in killing pits’.Footnote 126 Herzog drew parallels between the Holocaust and ‘scenes of Jewish women and children […] being herded into trucks’ on October 7.Footnote 127 This anchored the October 7 attacks within a case universe of tragedy; indeed, 57 per cent of Jewish Israelis drew direct parallels between October 7 and the Holocaust.Footnote 128

Another consistency within Israel’s strategic narratives was an emphasis on the ‘special relationship’ with the United States. Many of the diplomatic references within the narratives are US-centric, thanking the Biden administration for providing munitions and ‘a diplomatic Iron Dome that allows us to continue fighting’.Footnote 129 Overall, these references served several consistent purposes: to emphasise the US–Israel bond; identify Israel as defending the US’s interests; and highlight Israel’s military campaign as serving those interests. Gallant encapsulated this multifaceted framing when he claimed that: ‘Our common enemies around the world are watching, and they know that Israel’s victory is the victory of the free world, led by the United States of America.’Footnote 130 This suggests that Israel’s response to trauma was to double down on its ‘special relationship’ and source of derivative power. Again, this rhetoric corresponded to public opinion; in late October 2023 a record number of Israelis – 81 per cent – approved of the US’s regional role and policies.Footnote 131

Yet these commonalities within Israel’s strategic narratives before and after the critical situation mask the significant policy changes that took place following the October 7 attacks. In 2019, Netanyahu claimed that Israel would ‘topple the Hamas regime’ in Gaza.Footnote 132 But Israel did the opposite and helped transfer funds from abroad to keep Gaza’s Hamas government afloat.Footnote 133 This conformed to Israel’s status quo grand strategy, which preferred consistency over power vacuums and uncertainty. In 2019, Netanyahu claimed that ‘those who want to thwart the establishment of a Palestinian state should support strengthening Hamas’.Footnote 134 This is because doing so kept the Occupied Palestinian Territories divided between a Palestinian Authority-ruled West Bank and a Hamas-ruled Gaza. Israel could thus perpetuate the status quo of a frozen peace process, because Palestinian groups were allegedly too weak (the PA) or too illegitimate (Hamas) to negotiate with.Footnote 135

Israel abandoned this status quo grand strategy after October 7 by committing to ‘a crushing victory over Hamas, toppling its regime and removing its threat to the State of Israel’.Footnote 136 In contrast to previous declarations, Netanyahu’s government followed through. Previously, Israeli military doctrine favoured short, escalatory warfare to force a return to the status quo: a strategy termed ‘mowing the grass’, or using force to constrain and deter revisionist actors.Footnote 137 Whereas after October 7, Israel’s military conducted indefinite counter-insurgency campaigns in Lebanon, the West Bank, and Gaza.Footnote 138 Further, Israel’s inability to delineate a ‘day after’ plan in Gaza suggests that it is increasingly comfortable with power vacuums on its borders. Israel’s long-term goals in Gaza remain opaque at the time of writing. But multiple opinion polls, policy decisions, and rhetoric have all demonstrated a consistent preference against returning to the pre-war status quo, where Hamas ruled Gaza and Israeli forces were deployed on the other side of the border only, rather than directly controlling territory within all or parts of Gaza itself.Footnote 139

Similarly, before October 7, despite rhetorical sabre-rattling and a persistent ‘shadow war’, Israel refrained from directly attacking Iran.Footnote 140 After the Hamas-led attacks, however, Israel escalated conflict against Hezbollah in late 2024 and directly attacked Iran in a comprehensive, twelve-day campaign in mid-2025. Israel struck other targets previously considered off-limits, notably Hamas leaders in Doha in September 2025, regardless of the fact that Qatar was concurrently acting as a mediator between both parties. In short, the October 7 attacks de-legitimised the perception that the status quo advanced Israel’s interests. Instead, Netanyahu declared that Israel would ‘dramatically change the face of the Middle East’.Footnote 141 This rhetoric and Israel’s initial policies in Gaza illustrate the beginning of the country’s grand strategic shift away from status quo maintenance.

After the three-month period covered by the dataset, Israel’s shift from a status quo towards a force-centric revisionist grand strategy – and possibly even the pursuit of regional hegemony – became more prolonged and pronounced.Footnote 142 Before October 7, commentators noted a shift towards more hawkish policy preferences in Israeli opinion polls and electoral choices.Footnote 143 But it was the October 7 attacks – a shocking, traumatic and unexpected ‘critical situation’ – that exacerbated this trend and led to a grand strategic shift.Footnote 144

Though force-centrism has long been central to its grand strategy, the dataset illustrates that after October 7, Israel not only used this tool of statecraft to pursue revisionism rather than status quo maintenance; Israel’s leaders also emphasised military force at the expense of all else. This includes Gallant’s statements that: ‘I have ordered a complete siege on the Gaza Strip. There will be no electricity, no food’ and ‘I released all restraints […] we will destroy everything’.Footnote 145 Israel’s leaders even applied military rhetoric to economic issues. For instance, Netanyahu claimed that: ‘We will defeat the enemy militarily and we will also win the economic war’ and ‘the ship of the Israeli economy […] needs to arm itself with more cannon’.Footnote 146 This corresponds to a policy change: after October 7, Israel’s defence spending rose from 4.5 per cent of its GDP to 9 per cent.Footnote 147

Israel’s strategic narratives illustrate its twin war goals: destroying Hamas and freeing the hostages the group seized on October 7. There are fifty-four references to using force alone to free the hostages, compared to ten references invoking force and diplomacy. But at the time of writing, military action has freed only eight hostages. Indeed, military force has killed multiple hostages, either by ‘friendly fire’, or because Hamas operatives executed their prisoners when Israeli forces were nearby. By contrast, though just 2 per cent of the speeches in the dataset frame a ceasefire as an effective tool to free hostages, three negotiated ceasefires saw Hamas free 168 living hostages.Footnote 148 In short, Israel’s strategic narratives contain two assertions: (i) that destroying Hamas and freeing the hostages are complementary objectives; and (ii) that military force is the most effective tool to achieve both objectives.

Czechia

Czechia’s 2015 NSS did not identify any state-level actor as a significant external.Footnote 149 The dataset, however, reveals a striking shift: Russia’s Ukraine invasion caused the former to be framed as endangering Czechia’s national security and even its survival. Czech leaders de-legitimised any justification of Russia’s actions, because: ‘violence is violence, murder is murder. No one provoked or threatened Russia.’Footnote 150 Even the previously relatively pro-Russian Zeman labelled the invasion an ‘unprovoked aggression’ and charged that ‘Russia is committing a crime’.Footnote 151

This new consensus manifested in policy. Less than two weeks after Russia’s incursion, the Czech government declared a state of emergency and decreed public displays of pro-invasion sentiment illegal.Footnote 152 The 2023 NSS explicitly names Russia as Czechia’s most pressing threat and begins by stating that ‘Czechia is not secure’.Footnote 153 That this was published over a year after the period covered in the primary dataset illustrates that these were not solely short-term shifts in Czechia’s strategic narratives and its resultant policies. Indeed, in both 2022 and 2025, 74 per cent of Czechs identify Russia’s actions in Ukraine as a threat to world.Footnote 154

Czech leaders employed the increased threat perception to justify a shift away from soft power and towards a more balanced application of means. That military force is mentioned in nearly half the speeches in the dataset illustrates its increased salience. Czech leaders advocated increasing defence spending and modernising the country’s armed forces.Footnote 155 Similarly, the 2023 NSS states that: ‘Czechia must prepare thoroughly for the possibility that it could become part of an armed conflict.’Footnote 156

These strategic narratives corresponded to a policy shift. First, Czechia passed a law in 2023 mandating that defence spending must total at least 2 per cent of GDP.Footnote 157 By contrast, when the 2015 NSS was published, defence spending totalled under 1 per cent of Czechia’s GDP.Footnote 158 Second, Czechia gifted its antiquated military equipment to Ukraine; it then embarked on an ambitious military spending and modernisation programme.Footnote 159 This continued after the period within the dataset and included Czechia’s purchase of F-35 fighter jets from the United States in early 2024 and 2A8 Leopard tanks from Germany in September 2025.Footnote 160

Concurrently, both the speeches within the dataset and the 2023 NSS advocate increased societal resilience and economic interventionism as a necessary force multiplier to sustain Czechia’s policy shift. Czechia’s strategic narratives backed ending the country’s long-term reliance on Russian gas and oil to achieve ‘energy security’, whilst acknowledging that this would require significant economic changes and for consumers to pay a personal price.Footnote 161 The NSS notes that ‘the state now plays a much stronger role’ in the economy; this is because Czechia’s government ended energy supply contracts with Russia and provided stipends to citizens affected by the subsequent cost of living crisis.Footnote 162 As such, both the dataset and NSS exhibit how Czechia’s energy and economic policies were securitised. It was, in turn, the invocation of national security concerns that legitimised previously untenable policies. One such prominent example was Czechia’s January 2025 declaration that it had ended its energy dependence on Russia and would subsequently import no more Russian oil.Footnote 163

Whilst cutting ties with Russia, providing Ukraine with equipment would ensure that ‘the Czech army will have fewer supplies’, but ‘we must help our friends in difficult times, even at the cost of our own discomfort’.Footnote 164 These new strategic narratives corresponded to a policy change. Czechia was among the countries that provided military and material assistance to Ukraine very rapidly and, relative to its population, accepted the largest number of Ukrainian refugees. Although in the years following the Russian invasion it was no longer among the top supporters of Ukraine in either absolute or relative terms, it maintained a clear pro-Ukrainian stance, and humanitarian support from Czech civil society persisted. In addition, the Czech government distinguished itself through its active diplomatic engagement, most notably through the ‘ammunition initiative’. Since 2024, Czechia worked with seventeen other countries to deliver more than two million artillery shells to Ukraine; according to one report, this ‘strengthened Prague’s role as a key enabler of European defence support’.Footnote 165

Russia’s Ukraine invasion also re-affirmed Czechia’s existing strategic narratives. Zeman claimed that: ‘Every morning, we should repeat our gratitude that we are not at war and that our country is a member of NATO and the EU’.Footnote 166 Černochová argued that EU and NATO membership ensured Czechia was ‘the safest in its history’, despite the unprecedented threat.Footnote 167 Almost every speech within the dataset mentions Europe; NATO appears in over 60 per cent of speeches. The NSS, in turn, declares Czechia’s continued preference for ‘cooperation in international organisations’ and ‘collective approaches to security and defence’.Footnote 168

Hence, the decision to sign a defence cooperation agreement with the United States and Czechia’s increasingly salient relations with Germany are less a policy shift. They are more a strengthening of existing strategic narratives that frame ‘the West’ and EU and NATO membership as essential for Czechia’s physical and ontological security, continuing the country’s long-standing grand strategy of employing its membership of these organisations as a source of collective power. Nevertheless, Czech support for both EU and NATO membership increased steadily from 2022 to 2025. Whereas previously, EU membership was a contentious issue, in 2025 65 per cent of Czechs stated that their country benefits from the EU membership, mostly because the EU contributes to strengthening peace and security.Footnote 169 Even Andrej Babiš – a former Eurosceptic Czech prime minister and leader of the biggest opposition party during the country’s 2025 parliamentary elections – emphasised his opposition to Russia’s policies in Ukraine and stressed his loyalty to NATO.Footnote 170

Czechia’s post-invasion strategic narratives also re-affirmed the country’s added value as a human rights advocate. Czech leaders repeatedly stressed that Russia’s actions were both a security threat and an anathema to Czechia’s home-grown liberalism. Lipavský emphasised the need to defend these values, whilst Putin ‘paranoidly fears’ democracy.Footnote 171 The NSS, in turn, invokes ‘democracy’, ‘human rights’, and the ‘rule of law’, thirty-four, fourteen, and ten times respectively.Footnote 172 The NSS delineates the first principle of Czechia’s national security policy, which constitutes support for ‘democratic values and principles’ alongside ‘the protection of […] human rights and fundamental freedoms’, whilst countries ‘with a poor human rights record poses a security threat’.Footnote 173 As such, Czechia doubled down on strategic narratives that propagate its affinity for human rights and the rule of law as a source of intrinsic power.

Though Czech leaders repeatedly advocated ‘a diplomatic solution’, Lipavský claimed that ‘appeasement does not bring peace’.Footnote 174 Černochová rejected any compromise that would only ‘cater to Putin’s appetite for more territory’.Footnote 175 Instead, she advocated ‘the strongest possible sanctions’ to ‘hit the Russian elite, the Russian economy and the standing of living of Russians hard’.Footnote 176 Similarly, the 2023 NSS claims that ‘the war represents a threat to the international order’ and warns that ‘if the West fails in its responsibility to protect that order, it will open the door to potentially even more destructive conflicts’.Footnote 177 In sum, in both the dataset and NSS, Russia’s invasion was framed as a revisionist act, which re-affirmed Czechia’s overall purpose as a status quo power.

Czechia’s strategic narratives utilised familiar memories of the country’s traumatic past under totalitarian rule to contextualise the Russian threat and to justify a policy shift as a necessary response. Černochová expressed frustration that, despite ‘our common past linked to the Soviet era’, Hungary did not consider Russia’s behaviour threatening.Footnote 178 Equally notable is the invocation of the Munich Agreement of 1938. Fiala claimed that: ‘We know well from the past what it is like when allies […] abandon us for the sake of a supposed peace’, because Czechia’s ‘historical experience […] makes us many times more sensitive to the situation where imperial countries try to force the obedience of their neighbours through tanks’.Footnote 179

Within the dataset, Fiala stated that: ‘Ukrainians are fighting for their country, for their independence […] but equally, they are fighting for us’.Footnote 180 Correspondingly, a persistent claim manifested: that Czechs and Ukrainians share significant historical, national, and cultural similarities. Indeed, after Russia’s invasion Czechia admitted over 400,000 Ukrainian refugees, increasing the country’s population by over 5 per cent.Footnote 181 At the time of writing, this appears to be the only one of the above narrative and policy shifts whose future remains in doubt. Opinion polls similarly show a Czech public that continued to support NATO and EU membership more than any time in recent decades, but it is also weary of prolonged war, open-ended military aid, and refugee absorption; it was these trends that contributed to Babiš’s election as the leader of Czechia’s largest party and potential incoming prime minister in October 2025.Footnote 182

Conclusions

Figure 7 illustrates that after two different critical situations, Israeli and Czech strategic narratives and grand strategies exhibited significant continuity. Because the October 7 attacks and Russia’s Ukraine invasion were perpetrated by actors outside ‘the West’, it is unsurprising that Israeli and Czech strategic narratives re-affirmed their attachment to ‘the West’ as a source of physical and ontological security. Both maintained and stressed their power maximisation strategies, via the EU and NATO (Czechia), or ‘special relationship’ with the US (Israel). This corresponds to existing studies of small states, which suggests that these actor-types practice ‘shelter seeking’ within a great power’s security umbrella, or by embedding themselves in international organisations.Footnote 183 Both states also re-affirmed their self-designated value as a pro-western democracy or human rights champion, whilst employing their strategic narratives to frame threats as antithetical to these values.

Figure 7. Comparing Israeli and Czech grand strategy pre-critical situation.

But whilst Israeli and Czech grand strategies each changed after a critical situation, they did so in different ways and orders of magnitude. Czechia’s strategic narratives reveal a new and sustained consensus that Russia constitutes a threat to state survival. Czechia’s leaders framed economic, energy, and foreign policies through a securitised lens, which they employed to justify a significant policy shift towards more military spending and energy independence. They also invoked political solidarity and cultural similarities to justify a new programme of humanitarian and military aid for Ukraine. Israel’s strategic narratives exhibited a consistency of perceived threats and the related rhetoric to describe these threats. Its grand strategy retained its force-and-US-centric bias. Yet this masks a systemic change: after the October 7 attacks, Israel transitioned from a status quo to a revisionist regional power.

Thus, Israel underwent a grand strategic overhaul, whilst Czechia’s changes constituted a grand strategic adjustment. Israel employed consistent means to achieve inconsistent ends. Czechia, by contrast, altered its means in response to a new threat, but pursued the same ends as before its critical situation. The independent variable was the level of trauma and threat that the critical situation endangered. Czechia suffered a second order critical situation, whereas Israel endured a first order critical situation. Czechia’s 2023 NSS was the first such document for eight years, illustrating the level of the emergent threat and subsequent policy change. Indeed, the document calls for ‘a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach’: a grand strategy.Footnote 184 But this article illustrates that the 2023 NSS did not invent a Czech grand strategy. Instead, it and Czechia’s broader strategic narratives perpetuated existing heuristics and biases and articulated how they must adjust to a new geopolitical reality, to uphold consistent goals.

In sum, this article’s findings diverge from the literature on grand strategic shifts by rejecting the change/continuity binary. One scholar argues that ‘it is not change but the roots of stability that need explaining’.Footnote 185 But continuity and change not only coexisted in Czechia and Israel; continuity precipitated change, rather than impeded it. Invoking past collective trauma, for instance, anchored a critical situation within a familiar historical continuum. Conversely, invoking past trauma served to illustrate how extraordinary the critical situation was and thus also legitimised a policy shift in response. Equally, in neither case was grand strategic change a clean break from the past. In both Czechia and Israel, any degree of grand strategic change was accompanied by significant policy consistency. One scholar claims that second order changes (means) often follow first order ones (ends).Footnote 186 This article illustrated no such neat continuum. Israel underwent a first order change, without a corresponding second order shift; in Czechia, the opposite was true. Scholars should look therefore less at whether a grand strategy changes (or not). Instead, they should identify how continuity can both preclude and promote change and under which circumstances.

Given that grand strategy is inherently long-term, future works should examine how sustained the policy shifts delineated here were. Equally, at the time of writing, both conflicts are ongoing. Yet even a short period after a ‘critical situation’ offers a crucial window into elite meaning-making when narratives are most fluid and political choices most revealing of underlying strategic assumptions.Footnote 187 Further, the literature beyond these case studies demonstrates that when a significant policy shift does happen after an unexpected external input – as took place in Israel and Czechia – rarely do states return to their pre-existing policy choices, because the perceptions, heuristics, and beliefs that underlined them are no longer hegemonic.Footnote 188 Indeed, this article’s findings support that claim; the sub-section titled ‘continuity and change in Israeli and Czech grand strategy’ examined beyond the three-month period and found that – in both cases – the policy shifts identified in the primary dataset after each critical situation remained largely consistent.

Though this article’s findings diverge from the grand strategy literature, they conform to studies of ontological security, trauma, and strategic narratives, which assert that familiar narratives are necessary to understand uncertainty and justify change, because ‘narratives of national security rest on enduring identity narratives’.Footnote 189 Thus, rhetoric and the strategic narratives it contains are not purely cosmetic. Instead, they play a central role in reflecting, enabling, and constraining grand strategic change.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge funding from the Charles University Research Centre Program PRIMUS/22/HUM/011, as well as Charles University grant UNCE 24/SSH/018 (Peace Research Center Prague II).

Rob Geist Pinfold is Lecturer in International Security at King’s College London, a research fellow at the Peace Research Center Prague and the Herzl Center for Israel Studies in the Faculty of Social Sciences at Charles University in Prague, and an adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) in Bologna, Italy.

Zuzana Lizcová is Assistant Professor in International Relations at Charles University in Prague, Czechia, and a research fellow at the Peace Research Center Prague.