1. Introduction

The concept of engagement has garnered increasing scholarly attention in applied linguistics over the past few years. Recent publications (Hiver et al., Reference Hiver, Al-Hoorie and Mercer2021; Mercer & Dörnyei, Reference Mercer and Dörnyei2020) and systematic reviews (Hiver et al., Reference Hiver, Al-Hoorie, Vitta and Wu2024) have highlighted this trend. Engagement has been regarded as ‘the holy grail of learning’ (Sinatra et al., Reference Sinatra, Heddy and Lombardi2015, p. 1). Research in educational psychology has demonstrated that higher levels of student engagement contribute to improved academic performance and student well-being (Reschly & Christenson, Reference Reschly and Christenson2022). The field of second language acquisition (SLA) has also recognized the potential benefits of engagement in L2 reading comprehension (Khajavy, Reference Khajavy, Hiver, Al-Hoorie and Mercer2021) and L2 achievement (Eerdemutu et al., Reference Eerdemutu, Dewaele and Wang2024). Furthermore, lower levels of L2 engagement have been found to negatively predict L2 writing procrastination (Zhou & Hiver, Reference Zhou and Hiver2022). Despite its promising potential for holistically capturing the student learning process, the concept of engagement faces two key issues that must be addressed. The first concerns the overlapping nature of engagement (Hiver et al., Reference Hiver, Al-Hoorie, Vitta and Wu2024). Engagement is multifaceted with behavioural, cognitive, and emotional engagement as its core components (Fredricks et al., Reference Fredricks, Blumenfeld and Paris2004). Additionally, social engagement (Philp & Duchesne, Reference Philp and Duchesne2016) and agentic engagement (Reeve, Reference Reeve2013) have been identified as important constructs. It is true that the multifaceted nature of engagement allows researchers to examine the learning process from a holistic perspective; however, it also implies conceptual overlap that ultimately leads to inconsistencies in the literature. Reschly and Christenson (Reference Reschly and Christenson2022) described this problem as the ‘jingle-jangle issue’ (p. 4), indicating that the same term may refer to a different construct of engagement. Conversely, different terms might describe the same construct. Hiver et al. (Reference Hiver, Al-Hoorie, Vitta and Wu2024) also pointed out in their systematic review that fewer than 35% of the studies examined clearly defined engagement. The second issue relates to the blurred boundaries between engagement and associated concepts, particularly motivation (Teravainen-Goff, Reference Teravainen-Goff2022; Vo, Reference Vo2024). Given the growing body of research on the relationship between motivation and engagement (Khajavy, Reference Khajavy, Hiver, Al-Hoorie and Mercer2021; Noels et al., Reference Noels, Lascano and Saumure2019; Oga-Baldwin et al., Reference Oga-Baldwin, Nakata, Parker and Ryan2017), it is crucial to distinguish these two concepts clearly. According to Hiver et al. (Reference Hiver, Al-Hoorie, Vitta and Wu2024), ‘action is key in distinguishing engagement from motivation. Motivation represents initial intention and engagement is the subsequent action’ (p. 23). In the field of educational psychology, according to Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Ginns and Papworth2017), ‘motivation is defined as the inclination, energy, emotion, and drive relevant to learning, working effectively, and achieving; engagement is defined as the behaviors that reflect this inclination, energy, emotion, and drive’ (p. 150). These notions highlight a fundamental difference between motivation and engagement.

SLA researchers have made significant efforts to address these two issues, particularly in developing valid and reliable measurement tools through questionnaires. For example, Oga-Baldwin and Nakata (Reference Oga-Baldwin and Nakata2017) and Hiver et al. (Reference Hiver, Zhou, Tahmouresi, Sang and Papi2020) refined engagement scales adapted from general education, focusing equally on behavioural, emotional, and cognitive engagement. In contrast, the study conducted by Teravainen-Goff (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023), replicated in the current study, approached the aforementioned issue from a different perspective. Teravainen-Goff (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) defined the concept of engagement as follows: ‘engagement is an ultimately behavioral concept with underlying cognitive and affective facets’ (p. 2). This operationalization aligns with the action-oriented definition of engagement as ‘the amount (quantity) and type (quality) of learners’ active participation and involvement in a language learning task or activity’ (Hiver et al., Reference Hiver, Al-Hoorie, Vitta and Wu2024, p. 2). Teravainen-Goff’s (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) pioneering research addressed the issues surrounding the construct of engagement through a novel methodological approach based on a solid theoretical foundation, making this initial study worthy of replication for the further development of engagement research in SLA. Teravainen-Goff (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) also emphasized the need for further investigation, stating that ‘further research is therefore needed to test the Intensity and Perceived Quality of L2 Engagement Questionnaire in various language learning contexts’ (p. 9). In response to this call, the present study aims to replicate Teravainen-Goff’s (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) study in the Japanese EFL context to contribute to a deeper understanding of engagement through meaningful comparisons with the initial study.

The validation of Teravainen-Goff’s (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) study through replication was also motivated by concerns raised by Sudina (Reference Sudina2021) about questionnaire quality in applied linguistics. Among several recommendations for quality improvement, Sudina emphasized the need for transparency in questionnaire development, specifically stating that researchers should report ‘whether scale items were adopted or adapted, and, in the case of the latter, what specific modifications (i.e. both the amount and type) were made’ (p. 1183). Furthermore, Manapat et al. (Reference Manapat, Anderson and Edwards2025) reported the replicability of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) in questionnaire development in the field of psychology, noting that ‘although this is a relatively new area of methodological focus, there is empirical evidence in the factor analytic literature that can be considered issues of replication’ (p. 1). Given these concerns about questionnaire quality (Sudina, Reference Sudina2021) and EFA replicability (Manapat et al., Reference Manapat, Anderson and Edwards2025), we determined that a replication framework best served our purpose, because replication research requires strict adherence to initial study protocols, yet it allows researchers to examine target variables systematically (Porte & McManus, Reference Porte and McManus2019). We used the term ‘initial’ rather than ‘original’ to describe the work by Teravainen-Goff (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023), which was based on the discussion by Marsden et al. (Reference Marsden, Morgan-Short, Thompson and Abugaber2018). Therefore, the present study leverages a replication framework to report comprehensive information (e.g. variable modification and psychometric properties) and revisit the validity of this newly developed L2 engagement scale (Teravainen-Goff, Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) in the Japanese EFL context. We believe that this study contributes not only to deepening our understanding of engagement but also demonstrates the importance of questionnaire validation, particularly exploratory factor analysis (EFA), through a replication framework in applied linguistics (McManus, Reference McManus2024).

2. Background

2.1. Literature review

Extensive research has been conducted on motivation (Boo et al., Reference Boo, Dörnyei and Ryan2015); however, motivation alone cannot fully explain the complexities of the learning process (Teravainen-Goff, Reference Teravainen-Goff2022). Therefore, a more comprehensive construct was required to capture the learning process. Scholarly attention consequently shifted to engagement, which offers a holistic perspective on the learning process (Hiver et al., Reference Hiver, Al-Hoorie, Vitta and Wu2024).

Engagement is a multifaceted construct encompassing behavioural, cognitive, and affective dimensions (Fredricks et al., Reference Fredricks, Blumenfeld and Paris2004). Behavioural engagement refers to ‘students’ continuous performance in learning as determined by their expenditure of efforts on learning tasks, the quality of their participation, and their degree of active involvement in the learning process’ (Sang & Hiver, Reference Sang, Hiver, Hiver, Al-Hoorie and Mercer2021, p. 21). Cognitive engagement involves mental efforts such as connecting new concepts to existing knowledge (Hiver et al., Reference Hiver, Al-Hoorie and Mercer2021; Sang & Hiver, Reference Sang, Hiver, Hiver, Al-Hoorie and Mercer2021). Affective engagement manifests through emotional experiences during the learning process (Sang & Hiver, Reference Sang, Hiver, Hiver, Al-Hoorie and Mercer2021). Two additional dimensions have also been proposed: social engagement, which involves the collaborative aspects of learning with teachers and peers (Philp & Duchesne, Reference Philp and Duchesne2016), and agentic engagement, which describes learners’ active contributions to their learning environment (Reeve, Reference Reeve2013). The multifaceted nature of engagement provides a holistic view of the learning process; however, this multidimensionality necessitates a clearer operationalization of engagement within its dimensions, such as the behavioural and cognitive dimensions, and in relation to adjacent constructs, for example, motivation. A systematic review by Hiver et al. (Reference Hiver, Al-Hoorie, Vitta and Wu2024) also revealed a notable gap in SLA research, reporting that fewer than 35% of the studies examined demonstrated a clear operationalization of engagement. This lack of conceptual clarity underscores the fundamental weakness in the current theoretical development of engagement.

The current lack of conceptual clarity could be a result of the relatively short history of engagement research in SLA. Nonetheless, SLA researchers have substantially tried to deepen our understanding of this construct. A crucial step in this line of research was the development of valid and reliable measurement tools to evaluate learner engagement based on clear operationalization. Among the various methods available to measure engagement, questionnaires are the most widely adopted approach (Fredricks, Reference Fredricks, Reschly and Christenson2022). These questionnaires are generally categorized as either general engagement scales or domain-specific scales (Fredricks, Reference Fredricks, Reschly and Christenson2022). Within the field of SLA, there is a pressing need for domain-specific engagement scales that address the unique aspects of language learning. Recent efforts to develop such scales have shown promising progress. For example, Eerdemutu et al. (Reference Eerdemutu, Dewaele and Wang2024) attempted to develop a valid, reliable, and domain-specific engagement scale based on Hiver et al.’s (Reference Hiver, Zhou, Tahmouresi, Sang and Papi2020) study, using rigorous analytical procedures for high school students in the Chinese EFL context and university students studying Japanese in China. Similarly, using a mixed-method approach, Guo et al. (Reference Guo, Xu and Chen2023) developed a foreign language classroom engagement scale in the Chinese EFL context. Teravainen-Goff’s (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) work replicated in this study aligns with this trend of developing domain-specific L2 engagement scales. Among the reviewed scales (Eerdemutu et al., Reference Eerdemutu, Dewaele and Wang2024; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Xu and Chen2023; Teravainen-Goff, Reference Teravainen-Goff2023), we selected Teravainen-Goff’s (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) study for replication because of its innovative methodology, which is based on a strong theoretical foundation. A summary of the initial study and our rationale for this selection are presented in the following section.

2.2. Initial study: Teravainen-Goff (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023)

The initial study began by examining the literature on engagement, focusing on conceptual ambiguities in the previous definition. Building on a systematic review conducted by Hiver et al. (Reference Hiver, Al-Hoorie, Vitta and Wu2024), this study conceptualized engagement as ‘quantity and quality of learners’ active participation’ (Teravainen-Goff, Reference Teravainen-Goff2023, p. 3), developing a new instrument, the ‘Intensity and Perceived Quality of L2 Engagement’ questionnaire. A total of 378 secondary school language learners (mean age = 13 years) from England participated in the study. Of these, 77.5% of students learned French, 46.3% learned German, and 18.3% learned Spanish as a foreign language in compulsory foreign language classes. Additionally, 40.1% of participants were learning a foreign language for a General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) qualification and 1.9% for an A-level qualification.

The questionnaire development process followed a rigorous methodology. First, the researcher conducted a comprehensive review of engagement studies in both general education and applied linguistics. Second, the study incorporated the findings from a qualitative interview study (Teravainen-Goff, Reference Teravainen-Goff2022), in which learners’ and teachers’ perceptions of factors influencing engagement in language learning had been explored. The researcher then carefully screened relevant items to avoid measuring pretense engagement or unintentionally tapping into the concept of motivation. Following these procedures, 60 items were compiled, with wording adapted from Hiver et al. (Reference Hiver, Zhou, Tahmouresi, Sang and Papi2020). The questionnaire comprised three constructs (intensity, perceived usefulness, and satisfaction of engagement) and four aspects (teachers, peers, activities, and teaching content). The three constructs included these four aspects, resulting in 12 distinct factors in the initial structure (e.g. intensity of engagement with peers, satisfaction of engagement with teachers, and usefulness of engagement with activities). Subsequently, the items underwent expert review by four researchers in this field, leading to a refined 36-item engagement questionnaire. Finally, data collected from the participants using this 36-item scale were analyzed. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with oblique rotation revealed six latent factors. The researcher proposed a five-factor model with 18 items through subsequent expert evaluation and reliability testing. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) demonstrated good fit indices; χ2 (df = 125) 337.4, p < .001; comparative fit index (CFI) = .938; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = .916; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (90%CI) = .067 (.059; .076).

2.3. Motivation for this replication study

This approximate replication study was driven by the increasing scholarly attention to L2 engagement and the need to address its conceptual challenges. Following Porte and McManus’s (Reference Porte and McManus2019) framework, we classified this as an approximate replication study, which investigated ‘the effects of two variables on outcomes’ (p. 78).

The decision to replicate Teravainen-Goff’s (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) study is justified by its significant contribution to engagement research through a novel yet theoretically sound approach. This initial work (Teravainen-Goff, Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) was recently published in System and demonstrates its value through its novel but theoretically robust approach. To our knowledge, this study was the first to reorganize related engagement literature, operationalize the concept of engagement with a focus on the behavioural construct (Hiver et al., Reference Hiver, Al-Hoorie, Vitta and Wu2024), and subsequently develop an L2 engagement scale. As discussed above, this newly developed scale was created based on a theory-supported operationalization that reorganized the constructs of engagement and clearly distinguished between engagement and motivation. Therefore, this novel but theoretically sound approach has the potential to address key concerns about conceptual ambiguities raised by several researchers (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Ginns and Papworth2017; Nagy et al., Reference Nagy, Martin and Collie2022; Vo, Reference Vo2024). Given that the initial study was conducted in a UK context with a sample of 378 secondary school students, this replication study offers additional insights into the concept of engagement and the validity and reliability of the newly developed scale in a different context. To facilitate meaningful comparisons, this approximate replication study modified the target language and participant demographics. This replication set out to confirm to what extent the initial study’s findings hold in a new context when these two key variables are changed. By doing so, this study enables us to examine whether the action-oriented engagement scale functions consistently across different learner populations and educational contexts. This, in turn, provides additional support for the scale’s methodological foundation and contributes to advancing theoretical discussions on the multifaceted and context-dependent nature of engagement, a point also emphasized in the initial study by Teravainen-Goff (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023).

The first modification involved changing the target language variable from a UK context of learning various foreign languages to a Japanese context of learning English as a foreign language. The initial study was conducted in the UK, where the participants were learning foreign languages other than English such as French and German. In response to the following call in the initial study, ‘it would be interesting to investigate whether the target language may have an impact on the findings, especially given that English as a Foreign Language (EFL) was not considered in this study’ (Teravainen-Goff, Reference Teravainen-Goff2023, p. 9), we conducted this replication study in Japan, where students learn English from primary school to university as a foreign language.

The second modification involved the demographic variables, particularly age. The initial study focused on UK secondary school students (mean age = 13 years), whereas our study targeted Japanese university students (typically ages 18–22; see details in Table 1). This age difference is considered a meaningful modification because previous research into motivation has shown that motivational factors and models vary across different age groups (Kormos & Csizer, Reference Kormos and Csizer2008; Papi & Teimouri, Reference Papi and Teimouri2012). Therefore, this replication study also modified the age of participants to examine whether the scale functions similarly across different developmental stages. This approach helps us gain a clearer understanding of the extent to which Teravainen-Goff’s scale reflects age-specific engagement patterns or more universal features of engagement. This comparison also allows us to determine whether this scale is sensitive to developmental differences or whether it captures stable features of engagement that remain consistent across age groups. As regards other variables, we strictly adhered to the methodology of the initial study. Recognizing that scale translation could influence the findings (Dörnyei & Dewaele, Reference Dörnyei and Dewaele2023), we implemented a comprehensive translation process. The process involved working with a professional translation company to conduct back-translation and certify minimal semantic differences between the English and Japanese versions. Despite these rigorous measures, translation effects cannot be eliminated; thus, acknowledging this as a minor modification facilitates the careful interpretation of our findings.

Table 1. Comparative summary of participants from the initial and present studies

3. The present study

This study was designed to address three out of the four aims of the initial study. Our modifications to the initial study aim are presented below in italics. We excluded the first aim of the initial study, ‘provide a theoretical conceptualization of how the intensity and perceived quality of L2 engagement could be measured’, because the present study was conducted based on Teravainen-Goff’s (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) theoretical conceptualization of engagement. Given the comparative nature of this study, we added aim (d): ‘Investigate the similarities and differences in engagement between the initial and present studies’.

(a) Propose and test a structure for the Japanese version of the Intensity and Perceived Quality of L2 Engagement Questionnaire

(b) Examine the reliability and validity of the questionnaire in the Japanese EFL learning context

(c) Provide insight into the intensity and perceived quality of engagement for a sample of EFL learners in universities in Japan

(d) Investigate the similarities and differences in engagement between the initial and present studies

3.1. Method

All relevant and detailed information is shared on the OSF via this link (https://osf.io/an3ze/?view_only=064e30a1c4d4487dabde9496816f0d70), following our commitment to open science principles (Al-Hoorie et al., Reference Al-Hoorie, Cinaglia, Hiver, Huensch, Isbell, Leung and Sudina2024; Liu, Reference Liu2023; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Chong, Marsden, McManus, Morgan-Short, Al-Hoorie, Plonsky, Bolibaugh, Hiver, Winke, Huensch and Hui2022) and facilitating future replication of this study. Following Soderberg’s (Reference Soderberg2018) recommendation, we present the files below with descriptive names (e.g. file name: ‘example’) to facilitate easy access to relevant information.

3.2. Participants

In this study, we used convenience sampling to recruit participants, making every effort to include individuals from various academic backgrounds and different regions across Japan to enhance the generalizability of the findings. This study primarily used EFA and CFA; therefore, power analyses were not conducted to determine the ideal sample size. We endeavored to gather data from more than 300 participants, which was comparable to the initial study’s sample size of 378. Given that learners’ engagement can be influenced by teachers (Teravainen-Goff, Reference Teravainen-Goff2023), we requested the participation of as many English teachers as possible to minimize this influence. Consequently, eight English teachers cooperated with this study.

Table 1 presents a comparative summary of the participants of this study and those of the initial study. A total of 438 participants were involved in this study, with two excluded for not having provided their consent. On the other hand, 378 participants joined the initial study. Participants for this study were recruited from six universities located in Eastern and Western Japan. The participants were from diverse academic fields, including foreign language, humanities, law, social welfare, education, psychology, health science, sociology, law and economics, textile science and technology, societal safety sciences, economics, engineering, international and English interdisciplinary studies, and international studies, whereas the initial study recruited participants from five secondary schools in the UK.

In terms of the gender distribution, the participants in this study showed a balanced distribution comprising 188 male and 240 female participants, with ten participants preferring not to disclose their gender. This contrasts with the initial study, which had mostly female participants (75.1%). The age groups also differed. In this study, 314 participants were in the first year, 111 were in the second year, six were in the third year, six were in the fourth year, and one classified as ‘others’. Participants typically ranged from 18 to 22 years old within the Japanese education system. In contrast, the initial study involved participants with a mean age of 13 years. Regarding the target language, the participants in the initial study were learning foreign languages such as French, German, and Spanish, while participants in this study were learning English as a foreign language. All the participants in this study were enrolled in English classes at their respective universities. In terms of participants’ first language, 96% of the participants in this study identified Japanese as their first language, which was not mentioned in the initial study. Additionally, 36% of participants in this study reported taking external English proficiency tests, such as the TOEIC, in addition to their regular English coursework. This is compared to 40.1% of UK students who are studying for GCSE qualifications.

3.3. Instruments

The questionnaire was carefully created through a rigorous procedure because the wording in a cross-linguistic context could influence the results (Dörnyei & Dewaele, Reference Dörnyei and Dewaele2023). Initially, the first author translated 36 items of the initial scale into Japanese, ensuring that the meaning of each word was maintained and that the wording retained the underlying action-focused meanings. Subsequently, two researchers in applied linguistics checked the wording for clarity and consistency. Based on their recommendations, the phrases of items were refined to enhance participants’ comprehension of each item. To ensure cross-linguistic equivalence, Ulatus (https://www.ulatus.com/), an ISO-certified translation service provider (ISO17100), conducted back-translation. Minor refinements were made to improve clarity based on their suggestions. During the back-translation process, the company reported three minor discrepancies between the original English and the back-translated English versions, the details of which are shared below for transparency. The translation company certified that these variations maintained content equivalence. The certification documentation was uploaded to the OSF platform for transparency (see file name: ‘certification’).

(a) Original: ‘I usually pay attention to what my teacher says’; back-translation: ‘I usually listen carefully to my English teacher’

(b) Original: ‘I usually ask my teacher questions when something is not clear’; back-translation: ‘I usually ask the teacher questions during class if I do not understand something’

(c) Original: ‘There is usually a good mix of different types of activities’; back-translation: ‘There is a good balance of different types of activities incorporated in the regular classes’

Finally, the Japanese-translated version of this instrument was piloted with a sample of 37 university students. The analysis revealed high-reliability scores: McDonald’s ω = 0.964 [CI: 0.948, 0.978], Cronbach’s α = 0.963 [CI: 0.942, 0.978]. Based on these sound psychometric properties, we proceeded to use the Japanese version of the Intensity and Perceived Quality of L2 Engagement Questionnaire for the main study. The instrument used in this study is available on OSF (file name: ‘instrument’).

3.4. Data collection and analysis

Data were collected between June and July 2024. We obtained approval from our institutional ethics review board before data collection. We followed the data analysis procedures of the initial study as rigorously as possible. While the initial study used SPSS, we employed JASP (version 0.18), a free, open-source software package, for our statistical analyses, having confirmed beforehand that JASP could perform the same statistical analyses as SPSS. Prior to the primary analysis, we checked the assumptions for EFA. First, we assessed sample adequacy using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test. Second, we examined the correlation matrix for both multicollinearity (correlations > 0.9) and insufficient correlations (correlations < 0.3). Third, we determined the number of factors by examining the eigenvalues greater than one and inspecting the scree plot. Following the initial study, we retained items with factor loadings above 0.3. Finally, we conducted EFA using principal axis factor analysis with oblique rotation to examine the factor structure of the scale. Given that ‘EFA is an inherently subjective process requiring a series of researcher judgments’ (Plonsky & Gonulal, Reference Plonsky and Gonulal2015, p. 19) and recognizing the critical need for methodological transparency, comprehensive documentation of every step of the EFA procedures is presented in a supplementary file available on OSF. Following EFA, we conducted CFA using maximum likelihood estimation. We assessed model fit using the same criteria in the initial study: CFI > 0.9, TLI > 0.9, and RMSEA between 0.05 and 0.08. Within the CFA framework, we examined both the relationships between items and their intended factors, and the correlations among factors. We acknowledge that using the same dataset for both EFA and CFA is not ideal for inflated model fit values (Fokkema & Greiff, Reference Fokkema and Greiff2017). However, following van Prooijen and van der Kloot (Reference Van Prooijen and van der Kloot2001) reasoning, we used the CFA fit indices as a reference: ‘If a good fit is questionable when the factor structure is confirmatively tested on the same data, we cannot expect that a test of the factor structure in a confirmative follow-up study, that is, on different data, will lead to a good fit’ (p. 790).

4. Results

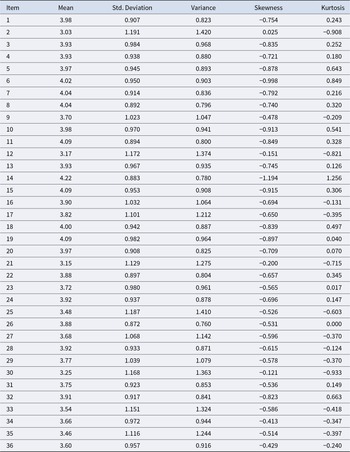

Table 2 summarizes the results for each item. All items showed skewness and kurtosis values within the range ±2, indicating normal distribution (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Hair, Hult, Ringle and Sarstedt2022). Before conducting EFA, we checked several assumptions. The KMO test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were conducted. The KMO test yielded an overall score of 0.939, with individual item scores ranging from 0.701 to 0.974, confirming adequate sampling (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Babin, Black and Anderson2019). Bartlett’s test of sphericity recorded p < .001, indicating that there were sufficient correlations (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Babin, Black and Anderson2019). Subsequently, the correlation matrix was checked to minimize the multicollinearity issue (> .90) and eliminate the weak correlations with other items (< .30). Based on these criteria, Item 21 (without > 0.3 correlations with other items) was removed from the initial analysis. The complete correlation matrix is available on OSF (see file name: ‘correlation matrix’).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for all the items

Note: N = 427. Eleven participants were excluded from the original sample of 438 due to potentially careless responding (i.e. selecting the same response option across all items).

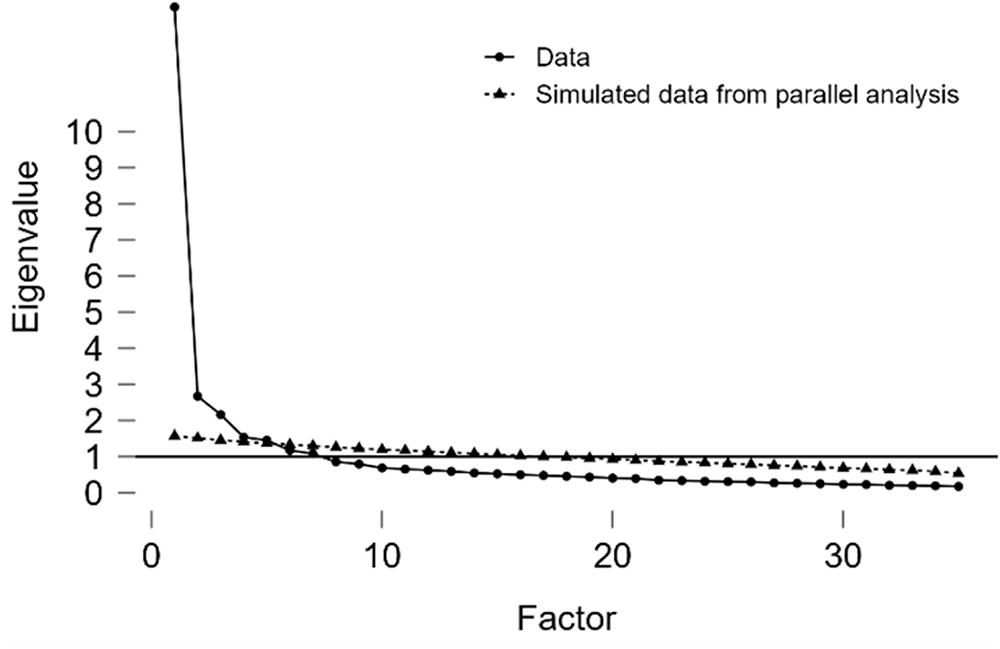

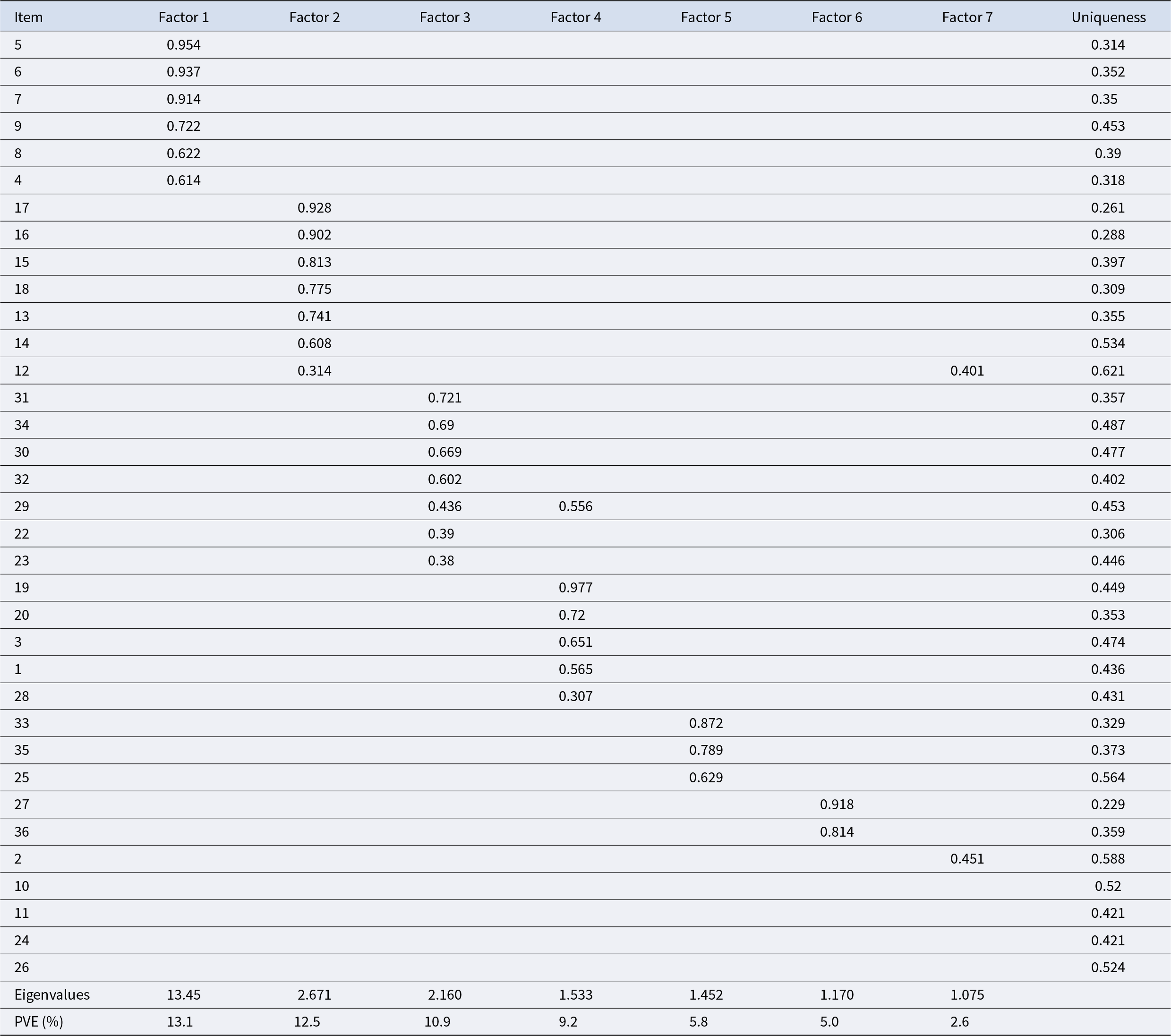

After checking the assumption, the main EFA was conducted. Initially, the number of factors to be retained was determined based on an eigenvalue greater than one (see Table 3) and a scree plot (see Figure 1). The results indicate that the seven-factor solution explained 59% of the variance. Table 3 lists the factor loadings for each item in descending order of value.

Figure 1. Scree plot.

Table 3. Factor characteristics and loadings from the initial analysis

Note: The applied rotation method is promax. PVE = proportion of variance explained.

After verifying all assumptions for EFA, we conducted our analysis following the same procedure as Teravainen-Goff (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023). The cut-off value for retaining the item was set to be greater than 0.3. Consequently, four items (10, 11, 24, and 26) were removed. Next, Item 2 emerged as the only item loaded onto Factor 7 (see file name: ‘EFA first stage’). In addition, the proportion of variance explained (PVE) of Factor 7 was 2.6%. Thus, Item 2 was removed in this stage. The following analysis indicated that Item 29 had cross-loading onto Factor 3 and Factor 4 (see file name ‘EFA second stage’); therefore, this item was removed. The above-mentioned procedure was the pre-set protocol mentioned in the data analysis section. The aim of the initial study by Teravainen-Goff (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) was to develop a questionnaire with reasonable numbers of items for each factor, with the author having mentioned that ‘this was considered important to ensure the final questionnaire does not have too many items and thus will not take too long to complete in the classroom’ (p. 6). Following the same procedure as the initial study, further examination was conducted to refine the questionnaire. The initial criteria for factor loading to retain the item were set to be > .30. This cut-off criterion was raised to > .40. Consequently, Item 12 and Item 28 were deleted (see file name ‘EFA third stage’). At this stage, the number of items for Factor 1 to Factor 6 was 6, 6, 6, 4, 3, and 2, respectively (see file name; ‘EFA fourth stage’). To develop a smaller set of items in each scale and with the initial study having a maximum of four items for each factor, Item 22 and Item 23, having the lowest loadings were removed. Further, Item 4 and Item 8, with the lowest loadings (see file name: ‘EFA fifth stage’), were also removed. For transparency, both items had factor loadings of 0.580. These values were high; however, examining the items’ contents revealed that they conveyed nearly identical meanings as other items within the same factor. Therefore, we concluded that these two items could be removed without losing the essential meaning of the intended factor. Lastly, Items 14 and 13 were considered (see file name: ‘EFA sixth stage’). At this point, the target factor contained six items, including Items 14 and 13. Following our protocol of maintaining a maximum of four items per factor, we removed Item 14 because it had the lowest factor loading. Item 13, despite having the second-lowest loading, displayed a strong factor loading (0.708), making its removal challenging to justify. Given that construct validity was prioritized over the number of items, we decided to retain Item 13. The final factor structure of the scale is presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Final factor structure

Note: The applied rotation method is promax. Factors 1 and 2 were reordered to allow for easier comparison with the subsequent sections.

The factors were named according to the initial study, except for Factor 6. Factor 1, containing items related to teacher support (e.g. ‘My teacher usually helps me to succeed in my learning’), was named ‘perceived quality of engagement with the teacher’. Factor 2, comprising items about peer relationships (e.g. ‘I usually feel that I learn a lot from working with my classmates’), was called ‘perceived quality of engagement with peers’. Factor 3, consisting of items addressing learning materials and topics (e.g. ‘The topics we cover are useful for my learning’), was dubbed ‘perceived usefulness of engagement with teaching content’. Factor 4, containing items related to student effort (e.g. ‘I usually try my best when my teacher asks us to do something’), was identified as ‘intensity of effort in learning’. Factor 5, comprising items related to student satisfaction with learning materials (e.g. ‘I usually find the content boring’), was named ‘perceived satisfaction of engagement with teaching content’. Factor 6, consisting of items addressing task difficulty (e.g. ‘I usually feel the activities are at the right level of challenge for me’), was called ‘perceived difficulty of teaching content and learning activities’.

Table 5 presents a comparative summary of the detailed factor structures of both the initial study and the present study. The initial study had five factors with 18 items, whereas the present study included six factors with 22 items. Both studies identified similar factors, such as perceived quality of engagement with teachers and peers, and the intensity of effort in learning. However, the present study had new factors, including perceived satisfaction of engagement with teaching content, perceived usefulness of teaching content, and perceived difficulty in teaching content and learning activities, while not including the intensity of social engagement and perceived quality of engagement with learning activities.

Table 5. Detailed comparison between the initial and present studies

Note: The numbers associated with the factors correspond to the items in the questionnaire.

The factorial structure extracted through EFA proceeded to the CFA stage. Table 6 summarizes the model fit indices. The result shows that the chi-square value was significant (p < .001); however, this value was considered to have been influenced by the sample size (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Babin, Black and Anderson2019). Therefore, we evaluated the model using other indices such as factor loadings and model fit indices. The CFI and TLI values were greater than 0.9, indicating a good fit. The RMSEA value also indicated a reasonable fit, and the SRMR value likewise demonstrated a good fit. The fit indices of the current study’s model are nearly equal to those of the initial study’s model described in Table 6.

Table 6. Model fit indices

The factorial structure detailed in Table 7 depicts all items loaded on their target factors with values between 0.611 and 0.95, supporting construct validity. Table 8 presents the details of factor covariance, demonstrating low to moderate relationships ranging from 0.159 to 0.699.

Table 7. Detailed factor structure

Table 8. Factor covariance

4.1. Validity and reliability

Regarding construct validity, each factor in the model was well specified, as reflected in Table 7. For convergent validity, we examined the average variance extracted (AVE) values, using 0.5 as the threshold. Factors 1 to 6 recorded values of 0.612, 0.661, 0.491, 0.521, 0.562, and 0.740, respectively. These results support convergent validity, although the AVE (0.491) for Factor 3 was marginally below the cut-off value. Regarding discriminant validity (see Table 9), we examined the heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) values. All values were below 0.9 (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Babin, Black and Anderson2019), supporting discriminant validity. As regards reliability, both McDonald’s omega (ω) and Cronbach’s alpha (α) were calculated. McDonald’s omega is considered to provide a more robust estimate than Cronbach’s alpha (Hayes & Coutts, Reference Hayes and Coutts2020). Both coefficients (see Table 10) confirmed good reliability scores (coefficient ω = 0.943; coefficient α = 0.909). The initial study reported that each factor’s coefficient alpha ranged from 0.7 to 0.9, which was nearly the same as the coefficient alpha in this study.

Table 9. Heterotrait-monotrait values

Table 10. Scale reliability

5. Discussion

This study endeavored to replicate Teravainen-Goff’s (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) study based on the aforementioned aims (a), (b), (c), and (d). Aims (a) and (b) are discussed separately, whereas aims (c) and (d) are discussed together to facilitate meaningful comparisons with the findings of the initial study. The first aim (a) was to propose and test the structural validity of the engagement scale. Building on the initial 36-item engagement scale and ensuring cultural equivalence through a rigorous translation process, we collected data from university students in the Japanese EFL context. As reported in the results section, EFA yielded a six-factor structure comprising 22 items. Subsequently, CFA verified the proposed structure, demonstrating a good model fit. The second aim (b) was to examine the validity and reliability of the scale. Multiple validity assessments were conducted to achieve this objective. Construct validity was evaluated through factor loadings and model fit indices. Convergent validity and discriminant validity were assessed using AVE and HTMT, respectively. For construct validity, all items demonstrated substantial factor loadings ranging from 0.61 to 0.95 on their intended factors, and model fit indices confirmed a well-defined factorial structure. Although Factor 3 fell slightly below the threshold value regarding convergent validity, the overall evidence supported convergent validity. Based on HTMT values, discriminant validity confirmed that all factors were distinctly separable.

The third and fourth aims, (c) and (d), were to gain insights from the engagement scale used in this study and compare the findings with those of the initial study. As Table 5 summarizes the key findings from both studies, the analyses revealed distinct structural differences: the initial study yielded a five-factor structure, whereas the present study identified a six-factor structure. Despite following identical procedures, the number of retained items differed between the studies. A detailed examination of the extracted factors revealed similarities and differences across studies. Regarding ‘perceived quality of engagement with teachers’, both scales demonstrated identical patterns with nearly identical items. This result suggests that teachers play a crucial role in promoting student engagement, regardless of the target language and participant demographics. Similarly, ‘perceived quality of engagement with peers’ demonstrated consistent patterns across studies. These findings highlight the significant roles of peers in student engagement. Furthermore, regarding ‘intensity of effort in learning’, similar patterns emerged across studies, although the specific items comprising these factors differed slightly. Despite these differences, all items retained the core semantic meaning of student effort.

However, notable differences between the two studies also emerged. The initial study identified ‘perceived quality of engagement with learning activities’ as a factor. In contrast, the present study did not extract the core meaning of learning activities; instead, the present study revealed ‘perceived satisfaction of engagement with teaching contents’ as a factor, with only one item overlapping with the initial study’s ‘perceived quality of engagement with learning activities’. Additionally, the present study identified the ‘perceived usefulness of engagement with teaching content’ as a factor. These comparisons with the initial study suggest that university students in the Japanese EFL context tend to associate their engagement more with learning content rather than activities. This finding may also be related to ‘the intensity of social engagement’. The initial study identified this factor with its core meaning of group work and class discussion. However, this factor was not revealed in the present study. This interesting difference could be explained by several factors, one of which is culturally bound learning styles. As Albertson (Reference Albertson2020) noted, ‘Japanese student perspectives toward class participation suggest they may incline toward silence due to aspects of the Japanese communication style’ (p. 47). Furthermore, learning in Japanese contexts is frequently characterized by a teacher-centered approach (Albertson, Reference Albertson2020). These factors might influence the findings. In addition, the present study identified a unique factor that was not anticipated in the initial scale: ‘perceived difficulty of teaching content and learning activities’. This factor, comprising two items with high factor loadings, suggests that university students in the Japanese EFL context tend to show high levels of engagement if the level of contents and activities match their level of English.

This discussion builds upon Teravainen-Goff’s (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) newly developed engagement scale, which focuses on the fundamental concept of engagement as ‘action’. This primary focus on behavioural engagement allowed us to conduct our data interpretation and discussion with conceptual clarity without being complicated by other dimensions, such as emotional engagement and cognitive engagement, or related concepts, such as motivation (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Ginns and Papworth2017; Nagy et al., Reference Nagy, Martin and Collie2022; Vo, Reference Vo2024). Most importantly, this precise and clearer operationalization of engagement within the replication framework (Porte & McManus, Reference Porte and McManus2019) provided a methodologically sound basis for conducting systematic comparisons across different contexts, thereby contributing to the applicability of this newly developed scale (Teravainen-Goff, Reference Teravainen-Goff2023) through our findings.

6. Conclusion

This study conducted an approximate replication of Teravainen-Goff (Reference Teravainen-Goff2023), having modified two variables: the target language and participant demographics. The present study identified a six-factor model with 22 items, compared to the initial study’s five-factor structure with 18 items. Using the same engagement scale, we identified both common and unique factors across the studies. Both studies extracted three common factors: ‘perceived quality of engagement with teachers,’ ‘perceived quality of engagement with peers’, and ‘intensity of effort in learning’. Different factors also emerged. The initial study identified ‘perceived quality of engagement with learning activities’ and ‘intensity of social engagement’. In contrast, the present study revealed three different factors: ‘perceived satisfaction with teaching content’, ‘perceived usefulness of teaching content’, and ‘perceived difficulty of teaching content and learning activities’. From these differences, it is inferred that participants from the initial study associated their engagement primarily with learning activities, whereas participants in the present study related their engagement to learning content.

In summary, this study provides interesting and meaningful findings that contribute to a better understanding of engagement from theoretical, methodological, and pedagogical perspectives. Theoretically, this study offers empirical evidence for further discussion to clarify the construct of engagement and its blurred boundaries with similar concepts such as motivation. Methodologically, we demonstrated the promising potential of scale development using a replication framework based on open science principles. The fundamental principle of identifying which elements to modify and which to maintain in replication studies enables the systematic accumulation of research findings across diverse contexts. Pedagogically, this study confirms the significant role of teachers and peers in learner engagement, suggesting that attention to these relationships is fundamental for promoting student engagement (Philp & Duchesne, Reference Philp and Duchesne2016). In the Japanese EFL context with university participants, the learning content and its difficulty level play a crucial role in promoting engagement; therefore, teachers need to provide interesting and tailored (i.e. at an appropriate difficulty level) tasks for language practice.

Despite its valuable findings, this study has a few limitations. First, although we aimed to collect data from a diverse sample to ensure the generalizability of our findings, further research is needed with both a broader participant population and English teachers representing diverse educational backgrounds and instructional approaches. Second, as noted in the data analysis section, we used the same dataset for EFA and CFA, which may have led to inflated model fit indices. Future replication studies using different datasets for this questionnaire would provide more robust evidence for validity.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the teachers and students who participated in this study. We are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which helped improve the manuscript.

Funding statement

This work was supported by JST SPRING, Grant Number JPMJSP2150, granted to the first author of this article.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

AI disclosure

We acknowledge the use of Claude 3.5 sonnet in the writing of this paper. The AI prompts used were ‘Improve this English’ or ‘Check the grammatical errors.’ The output from these prompts was used to write the following sections: introduction, literature review, data analysis, results, discussion, and conclusion. After using this AI tool, we reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Yohei Nakanishi is a Ph.D. student at the Graduate School of Foreign Language Education and Research, Kansai University. His current research interests include young language learners’ motivation, foreign language enjoyment, and engagement. He has published articles in journals such as Research Methods in Applied Linguistics.

Osamu Takeuchi, Ph.D., is a professor in the Faculty of Foreign Language Studies and the Graduate School of Foreign Language Education and Research at Kansai University, Osaka, Japan. His current research interests include language learning strategies, self-regulation in L2 learning, L2 learning motivation, and the application of technology to language teaching. He has published articles in journals such as Applied Linguistics, International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching (IRAL), Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, RELC Journal, Research Methods in Applied Linguistics, and System. Dr Takeuchi received the JACET Award for Outstanding Academic Achievement in 2004, the LET Award for Outstanding Academic Achievement in 2009, and the JLTA Award for Outstanding Academic Articles in 2024.