Introduction

The two first decades of the twenty-first century have been marked by democratic stagnation and setbacks, as both old and new democracies grapple with a range of internal and external challenges (van Beek Reference Van Beek2019; Carothers and O’Donahue 2019; Cassani and Tomini Reference Cassani and Tomini2020). In various contexts, political actors are attempting to separate democracy from liberalism (Plattner Reference Plattner, Vormann and Weinman2021). The foundational rules of liberal democracy - as the basis of the polity within and beyond the state- its core principles and values have become a source of conflict, and the EU is no exception. Not only are rights, pluralism and multiculturalism contested, but so is the rule of law – a longstanding normative ideal that has shaped political regimes and supranational polities to prevent arbitrary power and to guarantee individual rights (Tamanaha Reference Tamanaha2004).

Whether there was ever a consensus over liberal democracy, or whether it was simply a value taken for granted, or even an illusion (Barthels et al. Reference Barthels, Daxecker, Hyde, Lindberg and Nooruddin2023), it now seems to have been shattered. We have reached a point where liberal democracy is not only a politicised but also a polarising issue, both at the level of the European Union (EU) and within its member states. While contestation of liberal democracy and expressions of opposition have always existed, this phenomenon is no longer confined to the margins of the political spectrum: it has moved to the core. On the one hand, across Europe and beyond, populist radical-right parties rise against the core pillars of liberal democracy, fuelling discontent and polarisation (Börzel et al. Reference Börzel and Börzel2024). On the other hand, as Vormann and Weinman (Reference Vormann, Weinman, Vormann and Weinman2021) have underlined, there is also a crisis of conviction at the centre and a mainstreaming of the critique towards liberal democracy, with a more diverse group of actors claiming that democracy needs to be reinvented. Whether it is the Greens in the UK and Germany advocating for deep reform to improve transparency and citizen representation, the Pirate Party advocating for direct democracy as a solution to democracy’s problems or anti-establishment parties such as the Five Star Movement calling for substantial changes to how democracy functions in Italy, critiques of liberal democracy are no longer restricted to populist radical-right actors. Many voices, including at the centre, focus on the weaknesses of liberal democracy, the lack of accountability, the weak linkage with society and the difficulties of democratic institutions and procedures in tackling popular concerns, ultimately fuelling democratic disenchantment (Rosanvallon Reference Rosanvallon2008; Stoker Reference Stoker2006). Claims against liberal democracy are coming not only from more diverse ideological corners but are also supported by a broader range of social actors than ever before. Moreover, the current conflicts around liberal democracy feature an inherent conductivity, effectively transferring dissent between the social, legal and political arenas and making it more complex and challenging as the institutions, procedures and rules that are supposed to channel social, political and legal conflicts over core principles of liberal democracy seem to also be contested, eroded or even failing.

While there have been many studies on the crises of democracy, this article aims to contribute by concentrating on the nature of the dissensus over liberal democracy. In political science and political theory, dissensus has often been understood as a pre-condition for democracy, used in EU studies as a metaphor rather than as an established empirical concept. Drawing on its Latin etymology, “dis” means apart and “sensus” means sense, in other words “a sense apart”. In its basic definition in the Oxford Dictionary, the term is the antonym of consensus, therefore denoting the absence of consensus, a difference of opinion or an agreement to disagree, while implying the expression of different views or ways of making sense. While there is a broad academic consensus that dissensus encapsulates “the essence of politics” (Rancière Reference Rancière2010), it has been rarely studied per se, as a concept or as a phenomenon. This is precisely the ambition of this article and the research agenda presented in this special issue: to understand the growing dissensus over liberal democracy, or put differently, the lack of consensus over liberal democracy. This article proposes an empirical definition for this concept, supported by a typology or four ideal types of dissensus.

The article is organised as follows. Section "How to study the fading consensus over liberal democracy?" depicts the phenomenon under consideration and questions whether dissensus as a phenomenon can be studied through the lenses of well-established concepts in political science, namely opposition and contestation. Section "Defining dissensus as a two-dimensional concept" proposes an empirical definition of dissensus as well as a typology, both developed to enable researchers to understand how the nature of the conflict over liberal democracy and the heterogeneity of actors’ goals can lead to four types of dissensus: mild, constructive, disruptive and destructive. These four ideal-types of dissensus are then explained and illustrated in Section "A descriptive typology of mild, severe, disruptive and destructive dissensus" through concrete examples in reference to the principles of liberal democracy and its practice.

How to study the fading consensus over liberal democracy?

Over recent decades, liberal democracy has been at the centre of political debates within nation-states and at the supranational level. While in nation-states the ability of liberal democracy to satisfy the needs of citizens has been increasingly questioned (Berman Reference Berman2019), at the supranational level as well, the authority of the liberal international order has been increasingly contested (Börzel and Zürn Reference Börzel and Zürn2021). International relations scholars have examined how the growing liberal intrusiveness of international institutions has led to various contestation strategies (Börzel and Zürn Reference Börzel and Zürn2021: 282; Zürn Reference Zürn2018), while scholars of comparative politics and EU studies have focused their attention on the growing politicisation of the norms and principles of liberal democracy and the “end of the permissive consensus” (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2009; Sus and Hadeed Reference Sus and Hadeed2021). In the US, growing polarisation at the elite and citizen levels has facilitated the rise of illiberal behaviours and attitudes and driven growing contestation of the key rules and procedures of liberal democracy (Börzel et al. Reference Börzel and Börzel2024).

Scholars who study the history of ideas remind us that liberalism and democracy have always been disputed (Blondy Reference Blondy2018). Democracy has always been a contested concept. It is not just an old idea – it is also an enduring ideal that has evolved over several thousands of years (Dahl Reference Dahl1989: 2) from the Athenian democracy (Parekh Reference Parekh1992: 160) to the French Revolution (Berman Reference Berman2019: 284). Not only have various definitions existed since the seminal works of Przeworski (Reference Przeworski1991), Dahl (Reference Dahl1966) and Sartori (Reference Sartori1966), but so have different ideological conceptions rooted in conservative, social-democratic, liberal, neoliberal and radical ideas. Their confrontation is the essence of democracy (Mouffe Reference Mouffe, Palonen, Pulkkinen and Rosales2008). Like democracy, liberalism has also attracted its critics. As Berman reminds us, “liberalism and democracy are not the same thing, nor did they develop at the same time” (2019: 398). It was only after 1945 that liberalism and democracy fully united (Dahl Reference Dahl1989: 213) and the expression liberal democracy gained a modern meaning, being understood as a unique mix of individual rights and popular rule that has long been a dominant type of government in North America and Western Europe (Mounk Reference Mounk2018: 14). Thus, modern democracy derives its specificity from the articulation of two different traditions: on the one hand, the democratic tradition based on equality and popular sovereignty (Mouffe Reference Mouffe, Palonen, Pulkkinen and Rosales2008: 14), and on the other, the liberal tradition based on the rule of law, the respect for human rights and individual liberties. If democracy, historically speaking, is about “who rules”, which requires the people to be sovereign, the adjective “liberal” encapsulates less the idea of how rulers are chosen and more the limits to their power (Plattner Reference Plattner, Vormann and Weinman2021: 44). As Lacroix and Pranchère (Reference Lacroix and Pranchère2019) point out, there is no democracy without rights. In the same vein, rule of law outside a democracy is simply the most effective instrument of authoritarianism and worse (Weiler 2021). In other words, liberal democracy puts forward the tenets of liberalism: the rule of law must be guaranteed, minorities protected, individual civil liberties respected, and the political equality of all citizens accepted (Berman Reference Berman2019: 385), implying that all forms of democracy today have a liberal component (Rhoden Reference Rhoden2014).

The collapse of communism in Central and Eastern Europe gave rise to a global promotion of liberal democracy or the approximation of the Dahlian polyarchy (Dahl Reference Dahl1971). This ideal received global endorsement as a form of consensus (or an illusion of global consensus). For the first time since the French Revolution, in 1989 democracy faced no ideological competition (Berman Reference Berman2021: 72). But the illusion or consensus of the 1990s has been shattered (Coman 2022). As noted by Sus and Hadeed (Reference Sus and Hadeed2021), the consensus on the rules of the political game seems to have disappeared as new challengers contest liberal values. Mainstream elites are no longer shielded from illiberal tendencies. Today, debates about liberal democracy are no longer solely the purview of academic discussions. The core pillars of liberal democracy are politicised and, in some cases, significantly eroded (Gora and De Wilde Reference Gora and De Wilde2022). The post-war institutional arrangements seem to have reached their limits, being challenged by globalisation, European integration and social transformations. Key institutions, norms and values of liberal democracy, previously uncontested or taken for granted, are nowadays transported into the sphere of politics and are at the heart of a new line of conflict (Eigmüller and Trenz 2020).

Given not only the importance but also the complexity of this phenomenon, scholars have sought to trace its causes and to understand its implications, with some exploring the new waves of transition away from democracy (be it imperfect or with adjectives) towards autocracy (Grillo et al. 2023; Plattner Reference Plattner, Vormann and Weinman2021; Zakaria Reference Zakaria1997) or looking more specifically at the rise of populist parties (Eatwell and Goodwin Reference Eatwell and Goodwin2018; Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2012; Pappas Reference Pappas2019). While the phenomenon has many angles and can be illuminated through the analysis of endogenous and exogeneous factors, the decline of liberal democracy has been explained through the lenses of economic and sociocultural grievances (Berman Reference Berman2021; Castells Reference Castells2018). On the one hand, it has been argued that globalisation, neoliberal policies, rising inequality and technological change have engendered discontent and divisions among citizens. On the other hand, there are also sociocultural trends that may cause dissatisfaction with the core values of liberal democracy (Berman Reference Berman2021: 75). Party and public opinion scholars have examined this phenomenon in terms of politicisation, defined by De Wilde and Zürn (2012: 139) as the increased salience of liberal democracy in the public sphere. Others have focused on party competition to scrutinise how parties challenge democratic norms and procedures (Engler et al. Reference Engler, Gessler, Abou-Chadi and Leemann2023; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). Research has also examined citizen attitudes towards liberal democracy and its “disfigurations” as a key variable to understand democratic backsliding (Ananda and Dawson Reference Ananda and Dawson2024; Jacobs Reference Jacobs2024; König Reference König2022). Since this debate is not confined to the nation-states, Zürn has argued that “world politics is embedded in a normative and institutional structure that contains hierarchies and power inequalities and thus endogenously produces contestation and resistance” (2018: 3). The question of whether it is one explanation or the other, or all combined, that explains growing dissensus over liberal democracy as a phenomenon is beyond the scope of this article. The ambition here is to understand its nature rather than its causes.

Opposition and contestation are well-established forms of expressing dissent in any democratic regime. The right to criticise and publicly contest the measures and policies adopted by the government are one of the fundamental pillars of democratic regimes (Dahl Reference Dahl1966; Reference Dahl1971; Helms Reference Helms2021). Although democracies are based on a diversity of opinions (Dahl Reference Dahl2006: 78), in the study of democracy attention has been devoted to the emergence of what Rawls (1987: 2) called the “overlapping consensus”, meaning “how a constitutional regime characterised by the fact of pluralism might, despite its deep divisions, achieve stability and social unity by the public recognition of a reasonable political conception of justice” that is important for securing the stability of a constitutional regime. Scholars such as Manin (Reference Manin1987) and Elster (Reference Elster1988) have all in different ways focused on the virtues of consensus, understood as basic agreement in democracy, reached through “deliberation” (Manin Reference Manin1987), rational and consensual-oriented dialogue (Habermas Reference Habermas1996) taking the form of an “aggregative model of democracy” (Elster Reference Elster and Elster1998).

Opposition

The literature on opposition in democracy tends to focus on political opposition, namely on parliamentary opposition and more specifically on the minority parties in parliament (Helms Reference Helms2021). In the words of Dahl (Reference Dahl1966: 18), “there is opposition when B is opposed to the conduct of government A”. A distinction is made between political opposition as an institutionalised form of contestation and opposition as a non-institutionalised form of disagreement with power holders (Barnard Reference Barnard1972). Many typologies have been provided, drawing on Kirchheimer’s (1957: 130–136) seminal distinction between “classical opposition”, through which those not in government oppose and offer alternatives to the policies pursued by the government (Mair Reference Mair2007: 6), and “opposition of principle”, in which those opposed to the government object not only to its policies but also to the whole system of governance (Mair Reference Mair2007: 6). The latter has been defined by Sartori (Reference Sartori1966: 151) as “anti-system opposition”, through which actors – usually on the fringes of the political spectrum – challenge the legitimacy of the political system (or the polity). Not only does opposition target different dimensions (policy or polity), but it can be also “loyal”, “semi-loyal” or “disloyal”, denoting whether the actors act constructively, obstructively/irresponsibly or with violence (Linz Reference Linz1978; Sartori Reference Sartori1966). While the concept has mainly been used in relation to political parties, in recent years a burgeoning literature has developed to expand the concept of opposition to social actors and movements, especially those contesting the nature of political regimes, with a focus on the role of antidemocratic actors (from political parties to churches and social movements) in providing support for authoritarian politics or even autocratisation tendencies (Semán and García Bossio Reference Semán and García Bossio2021).

While nation-states have institutionalised channels to express opposition to varying degrees, in contrast, the political regime of the EU has been designed to accommodate the participation of a variety of actors in a fragmented and non-hierarchical system (Brack and Costa Reference Brack and Costa2017). The EU lacks the traditional “majority/opposition axis”. As Mair (Reference Mair2007:4) put it, there is little opposition in the sense of the institutional government-opposition dynamic. Opposition to the EU has been studied through the lenses of euroscepticism, often understood as the expression of “growing opposition towards European integration and/or the EU” (Taggart and Szczerbiak 2001). Yet, even in this case it remains unclear “what this opposition involves” (Mair Reference Mair2007: 3). As a result, classical opposition, directed towards policies, tends to turn into principled opposition, directed towards the polity (Mair Reference Mair2007: 5–6), while principled or qualified opposition to the EU as polity closely resembles anti-system opposition (Brack Reference Brack2018).

Contestation

Contestation is another potential candidate among existing theoretical tools to understand the actions, strategies or processes through which individuals, actors or states challenge the status quo, be it existing power structures, institutions or norms (Pulzer in Kolinksy Reference Kolinsky1987; Börzel and Zürn Reference Börzel and Zürn2021). The concept has been used in the study of social movements, ranging from protests to civil disobedience and violence, to examine actors’ strategies and their repertoire of actions, the networks of actors, as well as the relation between institutional structure and the effectiveness of the forms of contestation. In international relations (IR) research, contestation refers to the “disapproval of norms” (Wiener Reference Wiener2014: 1). Very recently, the adjective “deep” has been added to the concept in order to encapsulate the challenging of the principles and procedures through which policies are made and to denote the high degree of mobilisation and radicalisation (Börzel et al. Reference Börzel and Börzel2024). Like opposition, contestation is oriented towards power or governmental action. Contestation is an “interactive practice” that involves “at least two participating agents” (Wiener Reference Wiener2014: 1). Like opposition, contestation “depends on the respective environment where contestation takes place” (Wiener Reference Wiener2014: 1). Both are shaped by the institutional settings or political opportunity structures in which they manifest in response to power structures.

Against this backdrop, one could argue that studying dissensus over liberal democracy through the lenses of opposition or contestation is certainly feasible. Both concepts encapsulate the idea of conflict involving specific categories of actors, either political and social actors in domestic politics or non-state actors against international institutions – against power authorities. Actors are motivated by specific goals and aims, often animated by demands for change. We argue, however, that there are three main shortcomings in using these concepts.

First, a focus on contestation or opposition would restrict the phenomenon to specific actors, depending on the actors’ positions on the political spectrum. While we share Palonen et al.’s (2014) view that dissensus is a reflection of parliamentary politics, we contend that dissensus over liberal democracy in the current stage of EU integration goes beyond this arena. Second, since liberal democracy is no longer contested at the periphery of political systems, using contestation or opposition would exclude parties in government. Third, opposition and contestation are strategies used by actors to either target democratic institutions, norms and values (polity) or the policies of liberal democracy. In other words, following Rawls (Reference Rawls1993), they target both fundamental principles (the powers of legislature, executive and judiciary) and equal basic rights and liberties, essential components of the ideal of justice. Using the concepts of opposition or contestation would lead to research focused mostly on actors in national or international politics, without considering other actors and their interactions. As noted by Druckman (Reference Druckman2023), a wide range of actors – political elites, legal staff, societal organisations – are important to understand the current challenges facing liberal democracy. In our view, what is key to understand is the proliferation of actors contesting and opposing liberal democracy, not each one à part but all of them together, in interaction, understanding their goals and preferences and the nature of their dissensus. Dissensus deserves to be studied per se, not through other conceptual tools. The phenomenon implies a clash between actors who contest/oppose liberal democracy and actors defending this ideal. These actors can have different claims and express them in different institutional arenas at the national or supranational levels, as discussed in the next section.

Defining dissensus as a two-dimensional concept

The most advanced discussions of the concept of dissensus in relation to liberal democracy find their origins in political theory. In the 1990s and the 2000s, when consensus had become “the gold standard of political justification” and “an ideal to secure political legitimacy” (Dryzek Reference Dryzek2000; Dryzek and Niemeyer Reference Dryzek and Niemeyer2006), in response to Habermas (Reference Habermas1996) and Rawls’ (Reference Rawls1993) thesis on deliberative democracy, Mouffe (2016), Rancière (Reference Rancière2010) and Dryzek (Reference Dryzek2000), among others, sought to point out the limits of the aggregative model of democracy. They have taken a critical stance vis-à-vis consensus, arguing in favour of a “more robust pluralism” (Dryzek and Niemeyer Reference Dryzek and Niemeyer2006: 634) instead of a harmonious agreement where all conflicts and differences are solved. In their view, democratic theory needs to acknowledge “the impossibility of achieving a fully inclusive rational consensus” (Mouffe Reference Mouffe2000: 1). In a political debate, consensus is the exception and not the rule, dissensus being the essence of politics (Rancière Reference Rancière2010) and the quintessence of democracy.

For Rancière (Reference Rancière2010: 2), political dissensus “is not a discussion between speaking people who would confront their interests and values. It is a conflict about who speaks and who does not speak” – in other words, a conflict between different categories of actors, powerful and less powerful. Mouffe (Reference Mouffe2000) coined a theory of conflict, distinguishing between antagonism (conflict between friends and enemies) and agonism (conflict between adversaries who recognise the legitimacy of each other’s positions) while also admitting that it is difficult to distinguish the two. Both views provide important ontological and epistemological conceptions about conflict in democracy; yet dissensus has rarely been defined per se to be used as an empirical concept beyond its normative significance.

Building a concept is not only an ambitious endeavour but also a complex process, and an interactive one involving theory and empirics. Concepts often have different interpretations that are rarely consensual precisely because “progress of cultural sciences occurs through conflicts over terms and definitions” (Gerring, referring to Max Weber Reference Gerring1999: 359). As Mair (Reference Mair, Porta and Keating2008: 190) put it, not only must every concept have a core or minimal definition, but it must also be shared by others. Our focus is on dissensus over liberal democracy, not dissensus as such, although the concept can be applied to the study of other key controversies in our democracies.

Against this backdrop, we define dissensus over liberal democracy as a conflict between different types of actors, either about the fundamental principles of liberal democracy (its institutions or polity) and rights or about their implementation through specific policies, or both. Put differently, dissensus encapsulates a conflict that drives actors “apart” (dis-) over the sense (-sensus) of liberal democracy. The conflict can pertain to the ideal or the practice, leading actors to seek to preserve, restructure or replace liberal democracy. Dissensus defined in this way becomes observable when liberal democracy is politicised, when it emerges in public debate as a dominant theme amid ongoing social and political transformations. Based on this definition, dissensus has two essential dimensions: (1) the focus of the conflict, as it can target the very principles (fundamentals and rights) of liberal democracy or its practice (its policies), and (2) the heterogeneity of the actors’ goals.

What is at stake? The ideal, the implementation of liberal democracy or both

The decade of crises in Europe has given rise to various conflicts – between the EU and domestic actors, as well as within nation-states between political, social and legal domestic actors. Against this backdrop, dissensus over liberal democracy has taken different forms, translating into conflict either between rights and liberties or between egality and popular sovereignty, as well as between political and legal constitutionalism. As noted by Börzel and Zürn (Reference Börzel and Zürn2021), we must distinguish between conflicts pertaining to the practice of liberal democracy (policies) and conflicts pertaining to its existence or essence, that is, the very principles of liberal democracy and its core characteristics (polity). This distinction echoes the classical work of Easton (Reference Easton1975), who distinguished between specific support and diffuse support. While diffuse support refers to beliefs in the legitimacy of and values underlying the political system and the political community itself, specific support refers to what political authorities do and how they do it. Similarly, we argue that the conflict over liberal democracy can primarily pertain to, on the one hand, the practice of liberal democracy and its performances or the forms it takes, as expressed by its institutions and through its policies, and on the other, the principles of liberal democracy as an ideal, its values and its very existence. The consequences of the nature of the conflict for liberal democracy are different: while conflict over the practice of liberal democracy can be critical, it is likely to remain within the boundaries of democratic institutions. Conflict over the fundamentals of liberal democracy is more likely to disrupt the polity and test the resilience of institutions.

In other words, when the practice (policies) of liberal democracy is under debate, what is at stake is how decisions are adopted and how the values and principles of liberal democracy are implemented, not the ideal of liberal democracy per se. The conflict is fuelled by situations where liberal democracy contradicts its own principles and values. Examples are countless. The values of liberal democracy are currently under strain in the field of migration, trade (globalisation), climate change, gender issues, relationships to a colonial past or decisions about foreign policy. Actors might then point out the contradiction between the ideals of liberal democracy, such as equality and rights, and their implementation (Zürn et al. 2024). The practice of democracy is contested not only within the nation-states but also in terms of its reconfiguration at the supranational and international levels, taking the form of both vertical (within member states) and horizontal conflicts (between national and supranational actors) (Brack et al. Reference Brack, Coman and Crespy2019). From this perspective, dissensus over liberal democracy can be thought of as dissatisfaction with national practices colliding with supranational practices.

When it comes to conflicts over the principle of liberal democracy (polity), two recent examples are relevant: the eurozone and the EU rule of law crisis. The first encapsulates the tension between economic and political liberalism, and the second the tension between political and legal constitutionalism (Czarnota Reference Czarnota2024). In both cases, what was at stake was the power of elected institutions versus the power of independent institutions (whether the European Central Bank or the courts). In the case of the eurozone crisis, decisions in areas of core state power have been adopted behind closed doors at the supranational level, giving rise to concerns about legitimacy and sovereignty. In the case of the rule of law crisis, when the Hungarian and Polish governments assaulted domestic courts (Bugarič and Ginsburg Reference Bugarič and Ginsburg2016; Pech and Scheppele Reference Pech and Scheppele2017), they challenged constitutional issues and the balance of power in the political regime, altering the core of the domestic and supranational polity. The EU is even more prone to conflicts about the nature of the polity as the question of who has the last word in solving such conflicts (national or supranational institutions) has remained open, as an expression of constitutional pluralism (Coman 2022; Scholtes Reference Scholtes, Krygier, Czarnota and Sadurski2022: 401).

The heterogeneity of actors’ goals

For dissensus to erupt in the public sphere, liberal democracy needs to be debated and politicised. The recent decade of crises has constituted a major disruption, causing societal and political transformations in Europe (Hernandez and Kriesi Reference Hernandez and Kriesi2016) and affecting actors, their interests and preferences. Liberal democracy is no longer challenged at the periphery of political regimes but rather at their core, both on the right and the left sides of the political spectrum. As noted by Sus and Hadeed (Reference Sus and Hadeed2021: 429), “until recently, agreement around liberal democracy and its inherent values seemed to bind the major political and social movements in European countries and political elites seem to be somewhat shielded from illiberal tendencies.” In the current context, there is growing heterogeneity and fragmentation among elites, not only regarding policy issues but more importantly regarding the rules of the political game. This fuels dissensus as the more distant elites are from each other, the more dissensus will increase.

On the right and the far right, political parties have mobilised around the notion of liberal democracy and its core pillars, competing to offer diagnoses and solutions (Enyedi 2024; Smilova 2021: 179). Their critique focuses on political, economic and cultural liberalism. They do not operate in a vacuum. Over the past decade, they have managed to establish close links with civil society organisations, think tanks and intellectuals who support their programmes (Buzogány and Varga Reference Buzogány and Varga2021; Coman and Volintiru Reference Coman and Volintiru2021), seeking to “reinforce the party’s political narratives” (Bill Reference Bill2022: 120). Church and religious organisations play a major role in this process (Gherghina and Mișcoiu Reference Gherghina and Mișcoiu2022). The role of intellectuals is also pivotal as they are also actively engaged in think tanks, foundations and even academic institutions, which act as counter-hegemonic actors in Gramscian terms, targeting liberal democracy, its core values and institutions (Behr Reference Behr2021; Bohle et al. 2023; Pető, 2016).

On the left and radical left, the critique of liberal democracy sees democracy as impoverished (Smilova 2021), being reduced to elections and rights, without politics. From this perspective, the failure of liberal democracy lies with economic liberalism. What is disputed is the prevailing tendency to view democracy in such a way that it is almost exclusively identified with the rule of law and the defence of human rights, without regard to popular sovereignty (Mouffe 2016). In recent years, a wide range of protests have erupted in different EU member states, directed against neoliberal policies. The protests sparked by EU trade agreements such as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with the USA or the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with Canada (Crespy and Rone Reference Crespy and Rone2022; Oleart Reference Oleart2021) are a compelling example, not to mention the disobedience movements in reaction to emergency politics, “There is no Alternative” in the context of the eurozone crisis (Borriello Reference Borriello2017) or, more recently, climate protests.

We argue that actors of dissensus have developed a broader spectrum of preferences regarding liberal democracy, encapsulating four types of goals seeking 1) to preserve the status quo or national democratic models; 2) to restructure it at the national level, acknowledging liberal democracy’s failures and seeking to reform it with a focus on specific policies or even some aspects related to the polity; 3) to restructure liberal democracy at the supranational level, with a focus on specific policies or even some aspects related to the polity; 4) to replace liberal democracy tout court by other forms of non-democratic political organisation.

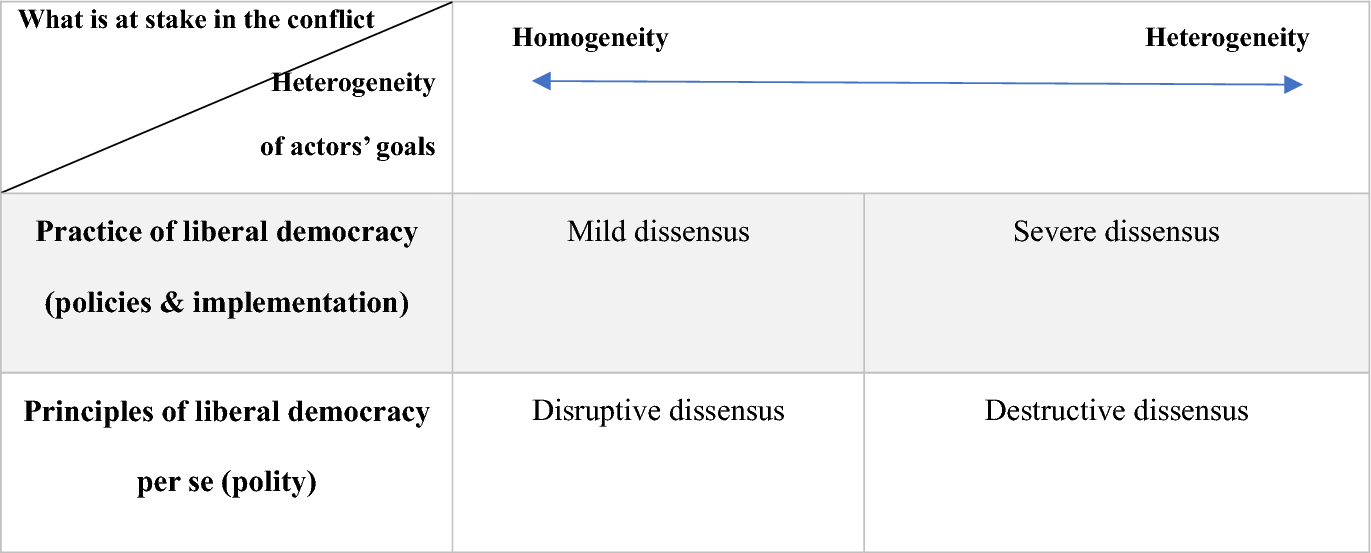

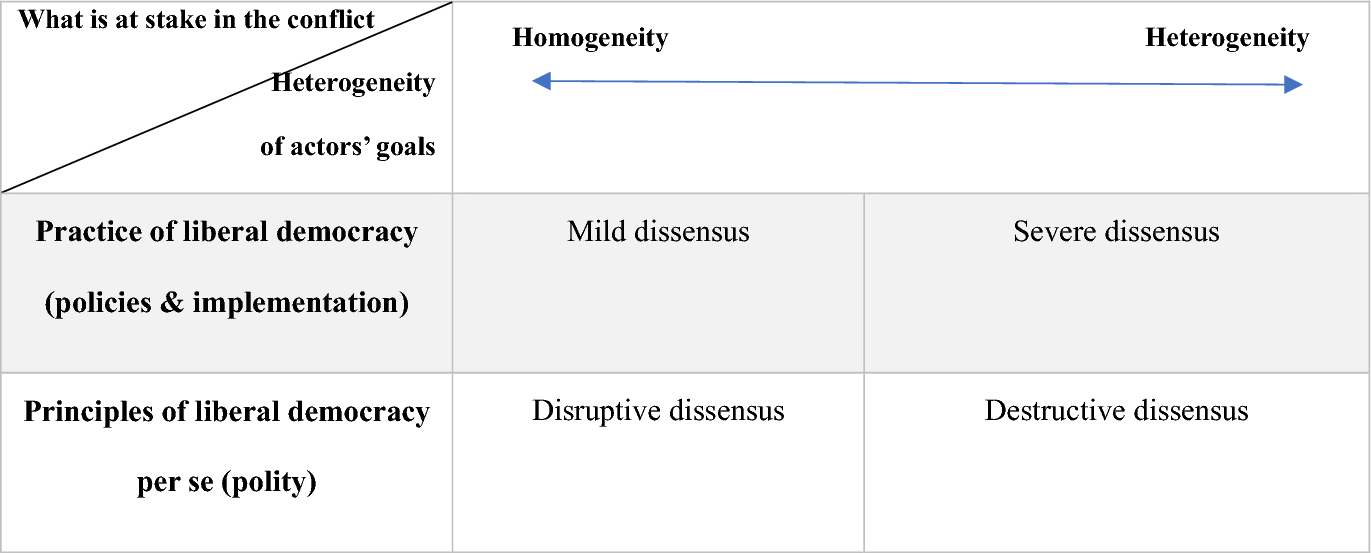

To sum up, the concept of dissensus over liberal democracy as we conceptualise it brings together two dimensions: (1) what is at stake (the ideal/fundamentals of liberal democracy or its practice) and (2) the heterogeneity of the actors’ goals (see Fig. 1). It also aims to take into account the linkages between arenas and interactions between actors, as the clash over liberal democracy is no longer restricted to the political arena but has spread to the social and legal arenas. Dissensus allows us to study all actors within these spheres, and not only fringe actors opposing or contesting governmental action, its policies or the nature of the polity. Furthermore, dissensus bridges the gap between opposition to policies and opposition to the polity: as noted by scholars recently, some actors do not always explicitly claim their opposition to liberal democracy but once in power, they nevertheless erode it either through reforms of the polity or gradual changes in policies leading to fundamental changes to liberal democracy.Footnote 1

Fig. 1 A descriptive typology of dissensus over liberal democracy

A descriptive typology of mild, severe, disruptive and destructive dissensus over liberal democracyFootnote 2

Typologies are created through the combination of two or more dimensions, with the categories of a classification acquiring two- or multidimensional characteristics (Mair Reference Mair, Porta and Keating2008: 183). They help in “forming and refining concepts, drawing out underlying dimensions, creating categories for classification and measurement, and sorting cases” (Collier et al. Reference Collier, LaPorte and Seawright2012: 217). Typologies can be descriptive or explanatory (Collier et al. Reference Collier, Laporte, Seawright, Box-Steffensmeier, Brady and Collier2010: 153). In descriptive typologies, the cells of the rows and columns correspond to specific dimensions of the concept; explanatory typologies can be translated into hypothesised outcomes. In our attempt to elaborate a descriptive typology of dissensus, we bring together the two key dimensions discussed in the previous section: the focus of the conflict and the heterogeneity of the goals of the actors (Fig. 1). The purpose of the typology is to distinguish between different types or intensities, so as to avoid using this notion as an overly broad or catch-all category.

We propose a 2 × 2 typology based on two dimensions (Fig. 1). While the first dimension is categorical, the second dimension is a spectrum. This means that what is at stake in the conflict is key to determining the kind of dissensus a political system faces (over the practice or principle of liberal democracy), whereas the second dimension refers to the degree of homogeneity/heterogeneity among actors’ goals, which in turn has an effect on the type of dissensus. If actors’ goals do not differ much or are congruent with each other or not very salient, we can speak of homogeneity – for instance, if all actors challenge liberal democracy to restructure it or to preserve it. In contrast, if the actors’ goals are incongruent, with one group seeking to preserve liberal democracy, one group seeking to restructuring it and one group seeking to replace it, polarisation will increase as their goals are very heterogeneous. Four ideal-types can thus be distinguished, which can be used to study dissensus in general or dissensus over liberal democracy in particular.

Mild dissensus refers to a conflict in which actors target the practice of liberal democracy, namely a specific policy or decision-making procedures, and in which their preferences are rather homogeneous despite differences. The conflict does not target the very existence of liberal democracy, and the goals of the actors are not far from each other. Actors can seek to preserve or change/restructure rules/practices and correct their failures while keeping them in line with the norms of liberal democracy. One recent example is the regulation of social media in Europe. Many note that digitalisation and the success of social media have had a profound impact on the public sphere. More particularly, the disruptions brought about by radicalised discourses diffused through digital and social media leads to the renewed salience of polarised value conflicts (Sunstein Reference Sustein2018; Trenz 2024). The EU has legislated the regulation of social media through the Digital Services Act (DSA), seen as a way to regulate social media but also to protect the EU from a shift from liberal to post-factual democracy. This particular policy relates to key rights and values, namely regulation and freedom of expression. But neither its content nor the decision-making process led to divisive conflict among political actors. Except for some fringe or challenger parties advocating for a libertarian idea of freedom of expression, there was little conflict as actors’ positions were not heterogeneous. In the European Parliament, the text was adopted at first reading, with 539 votes in favour, 54 against and 30 abstentions.

Second, severe dissensus reflects a situation where the conflict pertains to the practice of liberal democracy but where the actors’ goals are heterogeneous and far apart from each other. The conflict will be salient as a result, although actors can seek to preserve or change/restructure rules/practices and correct their failures while keeping them in line with the norms of liberal democracy. One example is the recent discussions on climate change and how the state should take measures to fight against it (or not). In some countries such as the UK, the Netherlands and Belgium, this conflict went beyond the traditional opposition between left-wing, right-wing and Green parties, as the conflict spread across several fields of society. Demonstrations took place to denounce a lack of action in terms of measures to fight against climate change, putting pressure on political actors. The positions of political actors have been very heterogeneous in terms of their stances, with some pitching the economy against the environment and others claiming that the environment should be the gold standard through which to assess all other policies. Some others, especially on the radical right, have claimed that climate change should not even be a priority. The conflict has also spread to the judicial arena, as cases against the state have been brought to the courts. Although the conflict started at the policy level, some court cases pertain to the rights of activists in the public space, but also to the power of judges in democracy. While these manifestations of dissensus can be severe, they are usually solved within the framework of liberal democracy because, despite the salience of the conflict, they deal with the practice of liberal democracy and not its very existence.

Third, disruptive dissensus pertains to the principles of liberal democracy. The conflict is about the core values, rights and norms of the polity, as new claims or new actors start to challenge the rules of the game. Conflicts are disruptive due to the underlying ambitions that drive them. Actors’ preferences are at odds with pre-existing ones. Yet, despite their disruptive nature the preferences and goals of actors are rather homogeneous. This is either because the new preferences find support among other actors who adjust their own goals to preserve or restructure liberal democracy or because the conflict does not involve very heterogeneous and polarised groups.

For instance, at more or less regular intervals, debates arise in Belgium over the power of national or international judges and courts. When judges issue controversial rullings (whether on climate or migration or specific rights), political actors on the right, and especially populist, politicise a key aspect of liberal democracy, namely the principle of checks and balances and the independence of judges. They openly express their preferences for subordinating judicial power to either the legislative or executive branch. In 2016, for example, the conservative Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie (N-VA), through its State Secretary for Migration, launched an online campaign against “the government of the judges” after the Court of Appeal compelled the State Secretary to issue a visa to a refugee family. The N-VA claimed that the court had overstepped its bounds and insisted that it is the role of the government and parliament to make rules. In 2023, the N-VA went further by proposing a “people’s appeal” mechanism that would allow parliament to override rulings of the Constitutional Court (Kelepouris and Van Horenbeek 2023; Struys 2023). This proposal was unanimously rejected by the other mainstream parties, who reaffirmed the importance of judicial independence and the rule of law as a cornerstone of liberal democracy (Nieuwsblad 2016). While the N-VA raised these issues, the party did not persistently pursue them or mobilise significant support around them. This type of dissensus can be disruptive, as it challenges a core pillar of liberal democracy, however the goals of the vast majority of actors are homogeneous and seek to preserve liberal democracy, while only a small minority seek to restructure liberal democracy without mobilising on it or politicising it.

Another situation arises when a new challenger party mobilises to restructure the foundations of liberal democracy, for instance by advocating the introduction of direct or participatory democracy elements into the decision-making process such as citizens' assemblies or referenda. If established political actors shift their preferences to align with those of the challenger, the resulting dissensus would be disruptive, as it concerns fundamental aspects of liberal democracy and would likely require constitutional reform or changes to the rules of the game. However, this form of dissensus would not necessarily be fragmented or polarised, as the actors’ preferences would remain relatively aligned rather than deeply divided.

Finally, the last type of dissensus is destructive dissensus. In this type of situation, both the ideal of democracy and its practice are at the heart of the conflict and the goals of the actors are heterogeneous and fundamentally irreconcilable. In this type of dissensus, actors seeking to replace liberal democracy would prevail and compete with actors seeking to preserve the status quo or to restructure liberal democracy. Destructive dissensus therefore becomes a confrontation between actors who seek to preserve or restructure liberal democracy and those looking to dismantle its core pillars and replace it with an alternative non-democratic political regime.

The examples of the Fidesz party in Hungry and the Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland are particularly illustrative, although they differ in nature and are not isolated cases in Europe, since radical-right parties have also won elections in countries such as the Netherlands, Italy, France, Germany and Austria. In the context of their rise in the EU, this type of dissensus – which targets not only the practice but also the foundations of liberal democracy – is likely to be observed in other national contexts. In Italy, for example, Fratelli d’Italia party seeks to change the constitution to allow a considerable concentration of powers in the hands of the executive and its media law is likely to become a point of scrutiny at the EU level.

Both Fidesz and PiS came to power using narratives denouncing the imperfect post-communist democratisation and the perceived failures of Europeanisation (Bill Reference Bill2022; Buzogány and Varga Reference Buzogány and Varga2021). Both aimed to transform the very nature of the post-communist political regimes, by strengthening the powers of the executive and limiting the independence of judges (targeting the nature of the polity), while limiting the space for pluralism and multiculturalism and putting citizens’ rights under strain through specific policies (Coman and Volintiru Reference Coman and Volintiru2021). Whether the outcomes of these transformations are an illustration of “democratic backsliding” (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016; Cianetti et al. Reference Cianetti, Dawson and Hanley2021; Vachudova Reference Vachudova2020) or “autocratisation” (Cassani and Tomini Reference Cassani and Tomini2020) goes beyond the topic of this paper. Destructive dissensus is an extreme type of dissensus that is not about the confrontation of alternative views, as in any democracy, but about the imposition of irreconcilable views as they are at odds with the basic ideal of democracy. The conflicts in these contexts target the fundamentals of the polity and policies, which are changed through non-democratic means, with rights being limited and power centralised in the hands of the executive. The actors of destructive dissensus challenge the core principles of liberal democracy, attempting to develop a counter-hegemony, finding support within society and fuelling conflicts over key constitutional principles, which gain support among other political parties and large categories of actors within civil society. This type of dissensus is destructive because it seeks to replace an imperfect liberal democracy, as denounced by its challengers, with non- or illiberal democratic models constraining the expression of dissensus. It is destructive in the sense that it also limits the expression of opposition. Furthermore, the preferences of the actors are heterogeneous and extremely polarised across different arenas: both in Poland and in Hungary, there have been demonstrations in the streets, mobilisation of intellectuals and opposition parties and a clash between the national government and supranational institutions, as well as legal disputes in the courts. When the Fidesz government rejected the Istanbul Convention claiming that the Convention promotes “gender ideology” (Pető et al. Reference Pető, Kováts, Kuhar and Paternotte2017), civil society actors mobilised to defend women’s rights and to oppose the dominant narrative of the government. They anchored their claims in broader concepts and norms of liberal democracy as stated in the constitution, such as freedom, non-discrimination and equality before the law, and connected these claims to the international and European legal frameworks. Their resistance also included strategic litigation and political engagement, with opposition parties increasingly adopting gender equality as a key component of their discourse (Ybanci 2024: 11).

These examples are context-dependent: no single policy domain is inherently more prone to one type of dissensus than another. The type of dissensus also depends on political and institutional traditions, and in particular the ability of institutions to cope with conflicts and polarisation, as well as with dissensus. Dissensus is the quintessence of democracy. Its nature will depend on the structure of the political competition, the preferences and goals of political actors, and their interactions. The advantage of the typology presented in this article is not only that it allows distinguishing between different types of dissensus but also that it underlines that a conflict can evolve through different stages of dissensus from mild to severe and from disruptive to destructive. These types of dissensus are not static; they are dynamic and responsive to institutional, social and political conditions.

Conclusion and new avenues for research

Democracy in general, and liberal democracy in particular, are at a turning point on a global level (Merkel 2022; Mounk Reference Mounk2018). The EU, where liberal democracy is both politicised and polarising, serves as an ideal environment to study the phenomenon of dissensus. We have argued that dissensus over liberal democracy has taken new forms and is no longer restricted to the fringes of society. The stances and claims against liberal democracy are no longer located at the extremes of the political spectrum but have become mainstream. Not only are populist radical-right parties in many countries large enough to play a governing role or to put pressure on governing parties, but there are also flourishing forms of contestation that target the core principles of the political game, which have long been taken for granted. As noted by Wiebrecht and his colleagues (Reference Wiebrecht, Sato, Nord, Lundstedt, Angiolillo and Lindberg2023), the focus is no longer only on the procedural or electoral aspects of democracy but increasingly on its non-majoritarian and liberal components, such as freedom of expression, minority rights and the rejection of social pluralism and the rule of law. In addition to the increasing number of actors politicising liberal democracy, European democracies also face a crisis of conviction among mainstream actors and an apparent failure of the institutions meant to manage conflicts, as these institutions are themselves increasingly divided. With the rise to power of either populist, radical-right or mainstream actors, the debates over liberal democracy, its shortcomings and possible reforms, have become a major conflict in several EU member states, while in others they have ended up in democratic backsliding. As a result, different conceptions of liberal democracy seem to be disputed within the EU, with implications for domestic and supranational polities and a wide range of national and European policies.

This article proposes a two-dimensional definition of dissensus and distinguishes between four types: mild, severe, disruptive and destructive dissensus. To do so, we first attempted to situate the contestation of liberal democracy in its intellectual context, in order to de-singularise the present. Democracy and liberalism are notions that have long been used separately, and both have their critics on the left and the right of the political spectrum. Unchallenged in the 1990s, liberal democracy has become a key topic of debate within the EU over the past decades. As consensus over liberal democracy has now crumbled, the question is how to study it. As well-established concepts in the discipline, opposition and contestation are ideal candidates. Yet they have their limits in capturing the nature of this phenomenon. To support empirical analyses, we define dissensus over liberal democracy as a conflict between different types of actors, either over the key principles of liberal democracy (its institutions or polity) and over rights, over their implementation through specific policies, or both. Dissensus encapsulates a conflict that drives actors “apart” (dis-) regarding the sense (-sensus) of liberal democracy. In this conflict, actors seek to preserve, restructure or replace liberal democracy. Drawing on this definition, we proposed a typology along two dimensions: the focus of the conflict (which can target the practice or the ideal of liberal democracy) and the goals of the actors (their relative heterogeneity leading to politicisation and fragmentation). Combining these dimensions, we established a fourfold typology of dissensus: mild, severe, disruptive and destructive dissensus.

What is the added value of focusing research on dissensus over liberal democracy and of providing a typology? While there is a very intellectually stimulating debate about the decline of liberal democracy in the EU (and elsewhere), the concept of dissensus stresses the need to focus more systematically on what is at stake, on the key preferences of actors and on their goals. It is all the more important now that liberal democracy is no longer just a target for radical-right parties and there is also dissatisfaction on the left and radical left, as well as at the centre. Dissensus over liberal democracy allows taking into account the various forms of this phenomenon, as well as its intensity and nature (as illustrated by the typology in Fig. 1). The concept and the typology are developed with a focus on conflicts in the EU, but given the current global trend it could be extended and be enriched by its application to other realities and political contexts.

The article is also a call to launch a new research agenda that aims to enrich the already well-established literature explaining how and why (liberal) democracy is being contested, declining or dying worldwide (Börzel et al. Reference Börzel and Börzel2024; Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019). In the face of this social and political context, our objective is to take a step further and examine how the confrontations of competing claims and preferences may lead to liberal democracy’s renewal, remplacement or survival.