Introduction

Short selling is one of the most salient issues facing financial regulators and supervisors around the world. Stock markets crashed following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and a bearish outlook prevailed on the markets. Investors heavily engaged in shorting stocks in times of market turmoil, which prompted regulators to view it as a potential threat to market stability. Short selling bans and restrictions were implemented in multiple jurisdictions for consecutive months in an attempt to maintain financial stability, and Korea was not an exception.Footnote 1 The Korean government introduced a temporary three-month restriction on short selling for all stock items on 13 March 2020. This measure was subsequently extended several times and remained in effect until 2 May 2021; as a result, Korea became the country with the world’s longest short selling ban. The regime then partially resumed short selling for benchmark indexes whose components are large-cap stocks having greater trading liquidity.Footnote 2 However, the government implemented a full ban on shorting stocks, effective from 6 November 2023 until the end of June 2024, and has most recently extended this ban through 30 March 2025.Footnote 3

The regulatory concern about short selling is nothing new; it has arisen at any time when there was a significant decline in stock prices that caused substantial loss and stress in the financial system.Footnote 4 In particular, following the 2008 global financial crisis, short selling drew great attention from both regulators and the public. Faced with historic market volatility and huge trading losses, commentators and politicians alike suspected short selling as one of the main culprits of the crisis, and regulators should have taken action to ‘show that they do their job’.Footnote 5 In many jurisdictions, including the EU and the US, regulators implemented various restriction measures. In addition to imposing a temporary ban on short sales, authorities introduced rules requiring disclosure of short positions and tightened sanctions on abusive trading practices (such as unlawful manipulation). The Korean government also reinforced short sale rules in line with international standards. Furthermore, it has hitherto fine-tuned the system, adding enforcement measures to its regulatory toolkit. Consequently, Korea is recognised for having the most stringent short selling system.Footnote 6

However, much criticism is directed at the short selling regime in Korea. Many commentators claim that ‘the illicit practice of selling short is prevalent in Korean markets but authorities are hesitant to identify and penalise short sellers who engage in abusive trading tactics’.Footnote 7 Moreover, some critics argue that the Korean market is an ‘un-level playing field’ which favours foreign and institutional investors over domestic retail investors by virtue of lower margin requirements and more flexibility to keep a short position open.Footnote 8 In their opinion, foreign and institutional investors exploit those significant advantages to earn undue profits at the expense of individual investors. Some retail investors even attribute Korea’s recent disappointing stock market performance to short sellers and advocate a complete ban on the practice.Footnote 9 Amidst the prevalent public discontent, short selling has surfaced as a highly politicised subject in Korea, prompting policymakers to bring it onto the reform agenda. Indeed, the Korean government has proposed or enacted a string of amendments to existing law and regulations.

This paper presents a critical analysis of the regulatory regime for short selling in Korea and offers suggestions for creating a more effective regulatory framework. Specifically, it argues that market authorities should take a balanced approach when regulating short selling activities, weighing the benefits and costs of restrictions. This perspective enables us to address the question of when a ban on short selling is reasonable and justifiable. It also notes that Korea’s short selling regime is ostensibly robust but archaic, which is why it requires substantial revision. Furthermore, it explains how the legal standards for emergency measures to restrict or ban short selling suffer from a lack of clarity and consistency, rendering regulators vulnerable to political interference.

The argument proceeds as follows. First, the article examines the rationales for and against regulating short sale transactions, bringing together supportive evidence and reasoning. It then provides an international comparison of regulatory frameworks for short selling across major jurisdictions. Thereafter, the Korean short selling law and regulations are critically reviewed, with an in-depth analysis of the issues in the current regime and measures will be proposed to improve regulatory performance. The final section offers concluding remarks.

Rationales for and against short selling regulation

The basic mechanics of short selling

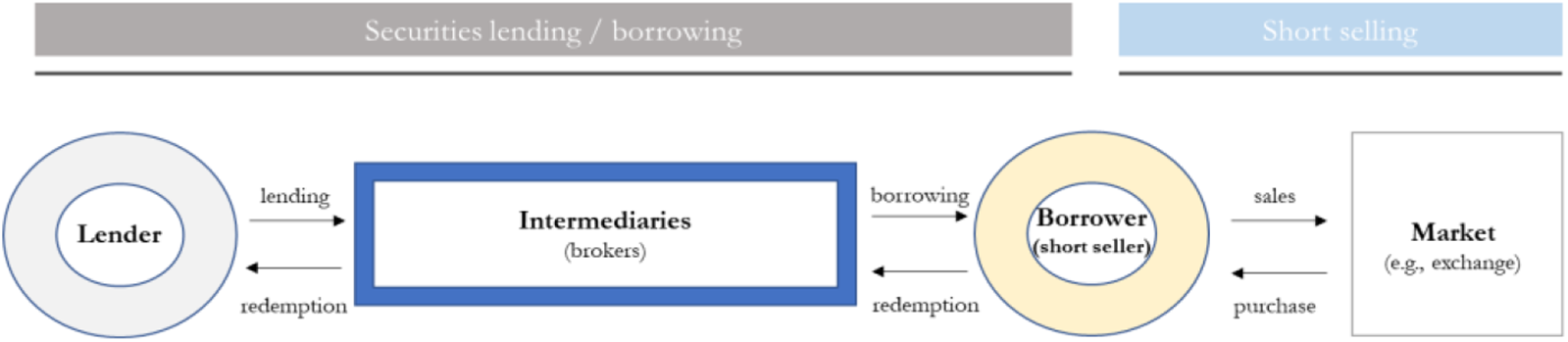

Short selling is a trading strategy that involves selling a stock not owned by investor who speculates on a potential decline in the stock price.Footnote 10 In shorting a stock, investors typically open a margin account to ‘borrow a share of stock from a broker before selling it’ in the open market to other market participants and then ‘closes out the trade by buying the security back, hopefully at a lower price’ to repay the loaned stock to the broker (see Figure 1).Footnote 11 If the share price falls as expected, the short seller makes a profit. However, if the stock’s price moves up instead of down, the trader incurs a loss in addition to fees and other charges for taking the short position.

Figure 1. The mechanics of short selling.

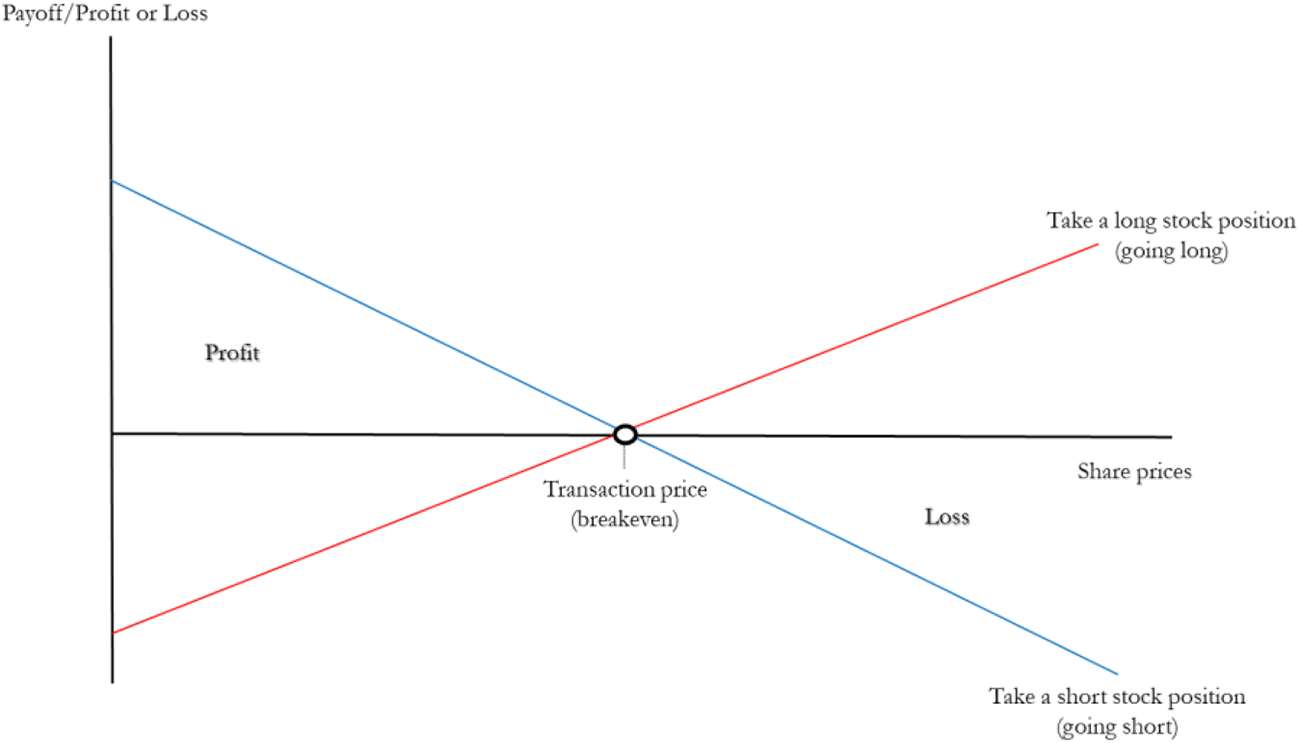

In this respect, short selling differs from ‘the more conventional trading strategy of taking a long position (or going long)’ that involves buying and holding (or owning) stocks with the intention of selling them at a higher price afterwards for a profit.Footnote 12 Indeed, the payoffs associated with the two positions are quite the opposite (as shown in Figure 2). When going long, the downside risk is limited as the share price can only fall to zero, whereas the potential upside is theoretically unlimited. In contrast, a short position offers a fixed upside as the lowest attainable share price is zero, but the losses for the short seller could potentially be limitless.Footnote 13 Moreover, although short selling and short positioning in the derivatives market can be used for similar trading purposes, they are technically differentiated in that futures, options, and swap contracts do not necessarily involve the physical delivery of the assets (in this case, securities) to the buyer.

Figure 2. (Going) ‘long’ versus ‘short’ stock payoff diagram.

Of note is that short selling entails substantial risks. The primary risk with shorting a stock pertains to the potential for adverse price movement, as seen above, that goes against a trader’s bearish bet. When combined with a short squeeze, a phenomenon where a heavily shorted stock experiences a sharp rise in price, the situation can become worse as short sellers may be compelled to cover their positions to limit losses.Footnote 14 Furthermore, short sellers are normally required to pay interest or fees to their brokers to maintain their short positions and adhere to the margin requirements; they face the risk of receiving a margin call if the value of the assets held in their margin account drops below a predetermined threshold.Footnote 15 Given the costs and intricacies associated with short selling, it is generally recognised as a sophisticated investment strategy that is most appropriate for experienced or professional investors.Footnote 16

Pros and cons of short selling regulation

The regulatory concerns related to short selling can be grouped into three main categories: (i) creating a ‘disorderly market’ and destabilising the financial system; (ii) facilitating ‘market abuse’ (eg, market manipulation); and (iii) causing ‘settlement disruptions’ triggered by a failure to deliver (or short delivery).Footnote 17

The first concern principally relates to the risk of ‘its capacity to add an incremental weight of selling to the weight of long sales which refers to selling stocks that investors already own and therefore do not need to borrow’.Footnote 18 In normal circumstances, short selling is not likely to pose significant risks; the price decline induced by short selling is usually short-lived and can be restored once the short seller covers her short position, ceteris paribus.Footnote 19 However, the destabilising risk is most pronounced in a bear market, ‘where short selling can trigger a downside spiral in prices’.Footnote 20 As evidenced during the 2008 financial crisis, a precipitous drop in share prices coincided with a significant upsurge in short selling orders for equity securities.Footnote 21 Increased short selling can prompt ‘long’ holders to sell stocks, thereby exacerbating the downward pressure on securities prices.Footnote 22 Furthermore, the plunges in share prices can seriously impair ‘investor confidence and possibly contaminate the pricing of other similar stocks in the market’.Footnote 23

With respect to this concern, however, empirical evidence suggests that short selling is not the main driver of a market collapse: ‘other factors, such as the media coverage of bearish news, investor herding, and long sellers (who sell stocks they actually own) not short sellers are likely to have had a more significant impact on the rapid fall in share prices’.Footnote 24 In fact, numerous studies support the idea that ‘short selling can have a beneficial effect on financial markets’.Footnote 25 According to the efficient capital market hypothesis, short selling serves as a mechanism for disseminating negative information which is otherwise not available to the marketplace regarding target issues, and thereby ‘facilitates price corrections in overvalued stocks’.Footnote 26 It is also well documented that short selling promotes market efficiency through ‘enhancing liquidity and trading opportunities’; it can facilitate hedging and arbitrage, enabling market participants to find it easier to take positions in the capital markets.Footnote 27 The increased number of potential sellers and their trading partners can bolster a market’s capacity to engage in price discovery. Separately, economic scholarship abounds with the diverse contributions of short sellers to improving market quality.Footnote 28

On a related note, much of the academic literature has expressed scepticism regarding the efficacy of short selling bans, with scholars demonstrating that short selling bans and restrictions are of ‘limited or no effectiveness in curbing price declines, instead resulting in a degradation of market quality’.Footnote 29 On a global level, for example, bans on short selling implemented during the 2008 financial crisis were ‘at best neutral in the effects on stock prices’.Footnote 30 Similarly, short selling bans that were imposed in the US on the premise that ‘short sales were driving stock prices below their fundamental value’ ultimately proved ineffective in preventing further declines in those prices. The bans led to unintended consequences such as ‘lowering market liquidity (proxied by the bid-ask spread) and boosting trading costs’.Footnote 31 A more recent study, which examined the short selling bans implemented in 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, reached a comparable conclusion.Footnote 32 Restricting short selling activities in the European stock markets widened bid-ask spreads, particularly for large-cap shares and had adverse impacts on market liquidity.Footnote 33

Another significant regulatory concern pertains to the use of short selling by those who are primarily intent on ‘manipulating the market in a stock’.Footnote 34 Short selling can be employed as a means to effect market abuse by ‘adding incremental weight to a downward’ or be used in conjunction with ‘false rumours designed to encourage others to sell’ shorted stocks.Footnote 35 Obviously, such actions can ‘[artificially] position prices, distort markets or mislead investors’, and, in doing so, ‘may well increase the scope to carry out the abuse’.Footnote 36

Nevertheless, it should be recognised that every major jurisdiction has already established a regulatory regime directed at market abuse.Footnote 37 For example, the EU Market Abuse Regulation (MAR), a pan-European framework for securities regulation, tackles these issues directly, and in the US, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Exchange Act) primarily regulates abusive practices in connection with securities transactions. Of particular note is that countermeasures under these regulatory mechanisms do ‘not interfere with the potentially beneficial effects of short selling’.Footnote 38 It is thus questionable whether extra short selling rules to combat market abuse are genuinely needed. If the existing set of provisions are deemed insufficient, it could only ‘merit a reconsideration of these rules and their enforcement’.Footnote 39

The last concern of settlement disruption stems from the potential for a delivery shortfall that occurs when short sellers have not borrowed the shares in advance and fail to settle the securities transactions.Footnote 40 Investors might not have ‘arranged borrowing ahead of sales and felt under no strong incentive’ to deliver the shares, given the lax settlement rules or disciplines, or might have been exposed to the risk of ‘sudden shortages or the unexpected recall of stock’ due to an abrupt decline in liquidity in the securities lending market.Footnote 41 Failure to deliver is a troublesome issue for regulators because it could not only increase ‘liquidity and operational risks’ for trading counterparties but also ‘propagate to other transactions, and potentially trigger a disturbance of the smooth settlement process’.Footnote 42 That is, the impacts can be systemic.

However, it is perceived to be ‘an issue that is relatively easy to tackle with stringent settlement rules and penalties’ to disincentivise default.Footnote 43 Besides, regulators have already paid particular attention to ‘uncovered (or naked) short selling wherein no effective borrowing arrangements are made ahead of short sales: as seen below, naked short selling is typically subject to strict prohibitions in major jurisdictions.Footnote 44 In this respect, settlement risk does not appear to be a significant challenge when compared to the two aforementioned issues.

Regulatory approaches to short selling: international comparisons

IOSCO’s key regulatory standards

Given the regulatory concerns associated with short selling discussed in the previous section, market authorities in many jurisdictions have sought to devise their own schemes to regulate the trading practices. As a result, short selling regulation varies considerably across the globe and suffers from a lack of consistency.Footnote 45 At the international level, the International Organisation of Securities Commission (IOSCO) set out principles of short selling regulation following the 2008 financial crisis, with the aim of reducing disparities in regulatory approaches among member countries. It also pursued the overarching objectives of securities regulation:

restore and maintain investor confidence under the financial crisis with a view to addressing the objectives of investor protection, helping to ensure that markets are fair, efficient, and transparent, and reducing systemic risk.Footnote 46

Specifically, the international body recommended the following four principles:

• Short selling should be subject to appropriate controls to reduce or minimise the potential risk that could affect the orderly and efficient functioning and stability of financial markets.

• Short selling should be subject to a reporting regime that provides timely information to the market or to market authorities.

• Short selling should be subject to an effective compliance and enforcement system.

• Short selling regulation should allow appropriate exceptions for certain types of transactions to ensure efficient market functioning and development.

In essence, IOSCO’s stance is to balance the potentially beneficial effects of the practice with the risks. IOSCO acknowledges that short selling plays a crucial role in the securities markets, such as ‘providing more efficient price discovery, mitigating market bubbles, increasing market liquidity, facilitating hedging and other risk management activities’.Footnote 47 However, it also stresses the role of adequate regulation against certain imprudent strategies (such as naked short selling) that can undermine financial stability and lead to disorderly market conditions.Footnote 48

Admittedly, the IOSCO principles are intended only as guidance and are neither sufficiently detailed nor legally binding. Nonetheless, these are oft-cited as good references when evaluating regulatory frameworks pertaining to short selling.

EU/UK short selling rules and regulations

A devastating financial crisis or a fraud-related scandal often leads to a revamp of regulatory systems, and the EU Short Selling Regulation (EU SSR) is the typical example.Footnote 49 In the EU, unilateral and uncoordinated national approaches to regulating short selling among Member States were perceived to be problematic during the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent European sovereign debt crisis. Reforms were pushed forward that aimed to harmonise the regulatory standards across the EU level, and Regulation (EU) 236/2012 entered into force in 2012.Footnote 50 It is notable that the resulting EU regime encompasses sovereign debts (ie, bonds issued by state entities of the Member States or the Union) as well as shares of stock within the regulatory perimeter. This represents the emergency response of EU legislators to the unprecedented sovereign credit risk, prompting European regulators to put top priority on preserving financial stability and restoring resilience in European capital markets. Some commentators point out that the European approach is politicised in that the EU’s regional rule is ‘entwined with that of hedge fund regulation’.Footnote 51 Indeed, hedge funds are alleged to be a main culprit of the sovereign debt crisis and widely blamed for having ‘worsened fiscal woes of euro-zone countries through raising borrowing costs’ at the time.Footnote 52

The EU short selling regime is far-reaching in scope and has a multi-layered framework. It applies to ‘all financial instruments that are admitted to trading on a venue in the Union, including such instruments when traded outside a trading venue’ (ie, having extraterritorial effects) and to ‘all derivatives that relate or are referenced’ thereto.Footnote 53 Importantly, however, the EU rule does not apply to ‘shares of a company where their principal trading venue is located outside the Union’.Footnote 54

Moreover, the EU framework is structured to be ‘complemented by national laws and regulations by the National Competent Authorities (NCAs), which govern the administration, the enforcement, and the sanctions for violations of the EU SSR’.Footnote 55 The pertinent regulations are predominantly implemented and enforced by NCAs in adherence to their respective domestic legislation, and it is at the national government’s discretion to establish the applicable rules.Footnote 56 Consequently, Member States exhibit a great divergence, particularly in terms of sanctions enforcement: for example, penalties for breaches of the short selling rules are up to €500,000 in Germany and even up to €100 million in France, while violations in Estonia are punishable by a maximum fine of only €32,000.Footnote 57

Nonetheless, it should be noted that considerable regulatory powers are also conferred on the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA). Although the EU authority typically ‘limits itself to coordinating the practices of NCAs’, it possesses the ability to exercise intervention powers in exceptional circumstances.Footnote 58 For example, ESMA may require market participants who have net short positions in relation to ‘in-scope’ instruments to ‘notify a NCA or to disclose to the public details of any such position or prohibit or impose conditions on short sales’.Footnote 59 There is a caveat, though: it must be deemed necessary for ESMA to ‘address a threat to the orderly functioning and integrity of financial markets or to the stability of the financial system and there are cross-border implications’, given that ‘no competent authority has taken measures to adequately address the threat’.Footnote 60

On a related note, the UK has questioned the validity of the ESMA’s power of intervention. Asking the European Court of Justice (ECJ) for review in an action for annulment, the UK government challenged the ‘compliance of the authority’s supervisory and rule-making powers with the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (EU Treaty)’.Footnote 61 In particular, it argued that ECJ precedents (the Meroni and the Romano rulings) ‘prohibit such delegation of powers’ and that the direct supervisory powers of ESMA over market participants lack a rational basis.Footnote 62 However, the ECJ ruled that the EU regulation was in fact compliant with all the requirements laid down in the EU treaty and dismissed the action.Footnote 63

The EU SSR takes a two-pillar approach to the regulation of short selling: (i) prohibiting the naked short selling of all in-scope instruments (including sovereign credit default swap agreements) and (ii) imposing transparency requirements for legitimate covered short sales.Footnote 64 The reason the EU regulation covers credit default swaps (CDSs) linked to sovereign debt is that derivative contracts have ‘an (economically) equivalent mechanism to directly short selling the sovereign debt’.Footnote 65 That is, the holder of a naked CDS (eg, a CDS without having a long position in the underlying asset to hedge against the risk thereof) benefits from the ‘deterioration of the creditworthiness of the issuer’ in the same manner as a short seller of debt securities takes profits from falling prices.Footnote 66 Naked short selling is deemed problematic because it is more likely to cause a failure to deliver and a severe decline in securities prices than covered short selling wherein a short seller has ‘ensured that she actually holds the securities at the settlement date’.Footnote 67 For these reasons, all transactions in uncovered sovereign CDSs along with naked selling of shares and sovereign debt are banned in the Union.Footnote 68

With respect to legitimate (covered) short selling, ‘two-tier private and public reporting’ is required for market participants holding net short positions.Footnote 69 Pursuant to the provisions of the EU SSR, a short seller must ‘notify the relevant NCA of a net short position that reaches or falls below a threshold that equals 0.1% of the issued share capital of the company concerned and each 0.1% above that’.Footnote 70 If a net short position has reached or fallen below a threshold of 0.5% of the issued share capital, the investor is then required to ‘disclose details of that position to the public’.Footnote 71 However, it is worth noting that notifying the NCA suffices for sovereign debt transactions.Footnote 72 Understandably, the aim of all these measures is to provide timely information to the market and market authorities so that they can make informed investment or regulatory decisions.

Furthermore, NCAs may exercise a wide range of intervention powers in times of emergency. When an NCA considers that adverse events or developments pose ‘a serious threat to financial stability or market confidence’, the regulatory authority may require market participants to privately report or publicly disclose their net short positions in specific financial instruments (such as corporate bonds) that fall outside the purview of the regulation.Footnote 73 Additionally, the EU SSR empowers national regulators to ‘prohibit or impose conditions relating to market participants entering into short sales or similar transactions’ and allows them to ‘ban transactions or limit the value’ of sovereign CDSs.Footnote 74 However, all these measures are just ‘valid for an initial period not exceeding three months from the date of publication of notice’ even though they can be ‘renewed further for another three months’ following the review.Footnote 75 That is, unless renewed, the measures automatically expire.

Meanwhile, the EU SSR has put some exemptions in place. Market makers and authorised primary dealers who are acting pursuant to agreement with a sovereign issuer are, in accordance with the provisions referred to in Article 17, largely exempt from complying with the EU rules.Footnote 76 As reasonably expected, allowing for exceptions as such is to support efficient market functioning and development.

The UK’s regulatory stance towards short selling is consistent with the EU approach. However, the UK regime is currently shifting from the EU-style law towards establishing its own regulatory framework after Brexit, which marked the withdrawal of the UK from the EU on 31 January 2020.Footnote 77 The UK government is committed to repealing and replacing retained EU law relating to financial services with a new legislation that is ‘tailored to the interests and needs of the UK economy’.Footnote 78 In doing so, the government wants to ‘support market integrity and bolster the (international) competitiveness of UK financial markets’.Footnote 79

On a related note, the draft of the Short Selling Regulations 2024 – the Draft Statutory Instruments (Draft SI) – that HM Treasury published on 22 November 2023 is a significant step forward in achieving these policy goals.Footnote 80 According to the Draft SI and an accompanying explanatory policy note, the UK’s incoming revised short selling regime is set to be far lighter-touch than the EU system in several important aspects. Indeed, the UK’s new short selling legislative framework implements the measures that aim to relax of the existing UK short selling regulations.

Most notably, there is to be a significant easing in disclosure regime. Specifically, the Draft SI ‘set the initial notification threshold for net short position reporting to regulators (in this case, UK Financial Conduct Authority, FCA) at 0.2% of the issued share capital’, up from the current 0.1% (restoring back to the level prior to the COVID-19 pandemic).Footnote 81 The FCA would then ‘aggregate and publish net short positions by issuer’, removing the current public disclosure regime based on individual net short positions above 0.5%.Footnote 82 Additionally, the UK government plans to scrap ‘existing short selling restrictions on sovereign debt or sovereign credit default swaps (CDS), and the related reporting requirements’.Footnote 83 The UK was in fact opposed to these regulations upon their introduction within the EU regime, contending that ‘such restrictions would have a detrimental impact on the liquidity of sovereign debt markets’.Footnote 84 The government asserts that, since their inception, it has not found any evidence to support this distinctive approach adopted by the EU.Footnote 85

However, the Draft SI empowers the FCA to make the detailed rules concerning short selling activity, which ‘includes, but is not limited to, the authority to impose restrictions on uncovered short selling to ensure settlement of trades, borrowing and locate arrangements’, and to ‘exempt certain shares or trading activities (such as market making and stabilisations)’ from the regulatory requirements.Footnote 86 With many of the particulars shifting from extant legislation to the FCA’s rules, the UK regime is poised to be rendered ‘far nimbler than the EU system, where changes must be effected by amending primary legislation’.Footnote 87 Further, the UK’s new short selling regime grants the FCA powers to intervene in exceptional circumstances. These powers include (i) ‘restricting short sales following a significant price fall where the authority considers this necessary to prevent a disorderly decline in the price of the financial instrument’, and (ii) requiring ‘notifications of short positions and information on lending fees, as well as prohibit or impose conditions on short sales and related transactions if there are adverse events or developments which constitute a serious threat to financial stability or to market confidence in the UK’.Footnote 88 Noteworthy here is that the FCA’s emergency power extends the range of covered instruments far beyond shares and related instruments; that is, financial instruments in scope of emergency interventions encompass all derivatives and debt instruments (which includes sovereign debt and CDS).Footnote 89 Notably, however, in order to exercise such powers, the market authority has to ‘assess that the intervention is necessary and that it will not have a detrimental impact on financial markets which is disproportionate to its benefits’.Footnote 90 The Draft SI, laid before Parliament in November 2024, was enacted in January 2025 and is subject to phased implementation, with main commencement planned for the first half of 2026.Footnote 91

US short selling rules and regulations

The US short selling regulation dates back to the 1930s, when there was a radical overhaul of the rules governing securities markets following the stock market crash of 1929. When the Exchange Act (or 1934 Act) was before Congress, it granted the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) plenary authority to regulate short selling of exchange registered securities, and the SEC has long been committed to striking a balance, recognising that (i) ‘concentrated short selling in a declining market can be a tool to destabilise and manipulate the market’ and (ii) short selling has beneficial effects on the securities market particularly in terms of ‘market liquidity and pricing efficiency’.Footnote 92

The US regime has extraterritorial reach and has put in place a wide range of rules to date.Footnote 93 Under Regulation SHO (which governs short selling), a broker-dealer is required to mark sell orders in any equity security as ‘long’, ‘short’, or ‘short exempt’ (Rule 200(g), marking requirements) and is generally prohibited from accepting or effecting a short sale order in an equity security unless the broker-dealer ‘has either itself borrowed the stock or has reasonable grounds to believe that the security can be borrowed so that it can be delivered on the date delivery is due before effecting a short sale order in any equity security’ (Rule 203(b)(1), locate requirements).Footnote 94 Moreover, a broker-dealer must be able to purchase or borrow securities of like kind and quantity so as to close out a failure to deliver (FTD) position by the beginning of regular trading on the next business day following the settlement date (Rule 204, close-out requirements).Footnote 95 The SEC anti-fraud rule, Rule 10b-21, is another provision that is designed to deter illegitimate short selling activities. It targets short sellers who ‘deceive broker-dealers about their intention or ability to deliver securities by the settlement date’; that is, misrepresenting to the broker or agency that they had located securities to enable them to settle the trades.Footnote 96 In effect, the combination of these rules ‘equate[s] to a de facto ban on naked short sales’.Footnote 97

The US rules include constraints on short selling in connection with seasoned equity offerings. Rule 105 of Regulation M generally prohibits selling short a security that is

the subject of the offering and purchasing the offered securities (to cover a short sale) from an underwriter or broker or dealer participating in the offering if such short sale was effected during a defined restricted period.Footnote 98

A central purpose of enforcing the rule is to protect market integrity, ensuring that ‘offering prices are determined by two competing forces of supply and demand without undue influence’ of speculative forces that could artificially depress market prices.Footnote 99

There are also some transparency rules. In addition to marking (short-sale ‘flagging’) requirements referred to above, self-regulatory organisations (SROs) are obliged to receive short-interest data from members and publish the aggregated data by security. Nevertheless, of note is that these do not constitute the core of US regulation. In lieu of the direct enforcement of reporting and disclosure requirements, the SEC is working with SROs to enhance transparency surrounding short sale transactions.Footnote 100 Specifically, in the US, brokers-dealers report their short interest positions for all equity securities to the applicable SROs, and in turn the SROs (such as the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, FINRA) publicly disseminate the ‘daily aggregate short selling volume information’ for individual equity securities. They also provide ‘website disclosure on a one-month delayed basis of information regarding individual short sales transactions in all equity’.Footnote 101 However, this approach has been subject to substantial criticism regarding its perceived shortcomings in terms of the ‘completeness, accuracy, accessibility, and timeliness’ of transactional data.Footnote 102 First, the information does not include data on non-FINRA firms. Next, although the SEC can ‘gather necessary information from SROs or request it directly from broker-dealers when investigating short sellers for potential trading abuses’, it has been observed that the process can be rather cumbersome and time-consuming.Footnote 103 Further, in contrast to the EU rules, the US regulation anonymises transactional data so that ‘no current data regularly provides the identities of short sellers to the SEC’.Footnote 104 In this regard, a new ‘data repository and reporting utility covering all information concerning orders and execution for exchange listed securities and options’, called the Consolidated Audit Trail (CAT), is likely to fix the existing problems considerably, even though it is still in the implementation phase and much will hinge on how it ultimately proceeds.Footnote 105

The most noticeable feature of the US short selling policy is its keen advocacy of the ‘tick test’ (in this case, the uptick rule), which restricts short selling in a declining market. Indeed, the uptick rule has long been the ‘heart of the SEC policy’ since its inception in 1938.Footnote 106 Former Rule 10a-1 under the Exchange Act banned ‘short sales on a minus-tick or a zero-minus tick’. That is, subject to certain exceptions, short sales were only permissible ‘(i) at a price above the price at which the immediately preceding sale was effected (plus tick), or (ii) at the last sale price if it is higher than the last different price (zero-plus tick)’.Footnote 107 Essentially, this rule aimed to prevent short sellers from accelerating the downward momentum of stock prices during periods of extreme market volatility.

The SEC rescinded the ‘uptick rule’ in 2007, demonstrating that the price restriction rule has been proven to be ineffective in stabilising stock prices by mitigating excessive sales pressure from investors in a falling market.Footnote 108 The decimalisation of price quotes introduced in the early 2000s was also one reason for the repeal of the price test; the SEC recognised that with decimal pricing, ‘even a one-penny price increase (after a steady fall in the price)’ would enable a trader to make massive profits from shorting a stock.Footnote 109 However, the trajectory of liberalisation on short sale transactions experienced an abrupt reversal with the onset of the 2008 financial crisis. As numerous financial institutions failed and many retail investors incurred heavy losses, the SEC came under tremendous pressure to ‘do something’ or at least to ‘show lawmakers and the investing public that it has an ability and willingness to tackle the issue’ so that it might hold firm stature as a regulator. Indeed, politicians of the time strongly called for the SEC’s short selling policy reforms, which forced the agency into a spate of rulemaking in the name of emergency measures, most notably including the re-imposition of a tick test.Footnote 110 Under newly adopted Rule 201 of Regulation SHO in 2010, the short sale price test is now subject to a ‘trigger’ rule that becomes active when a circuit breaker kicks in. That is, this so-called ‘alternative uptick rule’ that permits short selling when the price of a covered security is above the current national best bid is applicable only if the price of the shorted stock falls by more than 10% from its closing price on the previous day.Footnote 111 Once the circuit breaker in Rule 201 is triggered, it remains valid until the end of the following trading day (when it can be retriggered).Footnote 112 In adopting Rule 201, the SEC intended to enable long sellers to exit their positions before any short sellers in a bear market.Footnote 113

Meanwhile, the GameStop and other ‘meme’ stock trading frenzy in 2021 made the SEC reconsider its short selling transparency rules. As is well documented in its staff report, the SEC learned that it was possible for stocks with high short-interest to cause wild price swings in a bull market.Footnote 114 In particular, short squeezes en masse occurred, which drove the price up to a new high and ‘forced other short sellers to exit their positions, adding further upward price pressure and so on’.Footnote 115 Besides, it raised many tough questions regarding manipulative trading amongst market participants, including retail investors and trading platforms.Footnote 116

In response to these challenges, on 13 October 2023, the SEC introduced new rules aimed at enhancing the transparency of short selling activity. According to the newly adopted Rule 10c-1a, market participants involved in securities lending and borrowing must provide certain information about the loans, such as ‘name of the issuer of the securities to be borrowed, loan dates, loaned amount, type of collateral and rates (including fees and charges) for the loan’ to FINRA.Footnote 117 FINRA is then required to make publicly available ‘certain information it receives, along with daily information pertaining to the aggregate transaction activity and distribution of loan rates for each reportable security’.Footnote 118 Specifically, the final rule states that most of this data will be ‘published on an aggregate anonymised basis the following day’.Footnote 119 However, taking into industry’s concern account, FINRA will opt to ‘delay release of loan amounts by 20 business days’ as a concession.Footnote 120

The SEC also adopted Rule 13f-2, requiring investment managers (including investment advisers, banks, insurance companies, pension funds, and corporations) having large short positions in equity securities to submit monthly reports detailing ‘those positions and related short sale activity’ to the agency.Footnote 121 The threshold for reporting short position and short activity is set to be triggered if an investment manager holds a short position of ‘at least $10 million or 2.5 percent or more of the average total outstanding shares in a month for a specific equity security issued by a reporting issuer’, and for equity securities issued by a nonreporting issuer, the threshold stands at ‘$500,000 on any settlement day of the month’.Footnote 122 The SEC plans to then publish ‘aggregated, anonymised data about the gross short positions’ on a delayed basis and also make public the ‘net aggregated daily activity data for each settlement day’.Footnote 123 Arguably, this new transparency measure would ‘supplement presently available short sale-related data’ by extending the scope of information beyond what is not being provided within FINRA’s current short interest reporting regime.Footnote 124 The SEC expects these additional data to help the public and the agency know more about market-wide short bets and make informed decisions.Footnote 125

Other Asian short selling regimes: Japan and Hong Kong

The regulatory approach to short selling in Japan is largely similar to that of the US and shares many features. The Japanese securities law and regulations – the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA) and the Order for Enforcement thereunder (FIEA Enforcement Order) – stipulate the general prohibition on naked short selling, a ban against short covering in connection with public offering (akin to SEC Regulation M), marking requirements (Japan’s version of SEC Rule 200 of Regulation SHO), and the short-sale price test restriction (uptick rule subject to triggering a circuit breaker).Footnote 126 With respect to transparency requirements, however, the Japanese rules are comparable with those of EU law. The reporting and disclosure regime operates on a two-tier system that commences at 0.2% for private reporting, at 0.5% for public disclosure, and the scope of the data provided to the authorities mostly overlap. Moreover, unlike the US, both the EU and Japanese regimes publish data on short positions per investor, thereby disclosing the identities of reporting parties.Footnote 127

All these provisions were implemented with the ‘benefit of hindsight vis-à-vis US and European regulatory reforms in the aftermath of the financial crisis’.Footnote 128 In 2013, the Japanese government repealed the emergency (or temporary) restrictions (such as the naked short selling ban and position reporting requirements) imposed during the 2008 financial crisis to replace them with a permanent regime. The timing of regulatory reform was impeccable for the Japanese government because the domestic stock market had rebounded due to aggressive expansionary macroeconomic policies, and therefore, there was lower political pressure on lifting restrictions.Footnote 129

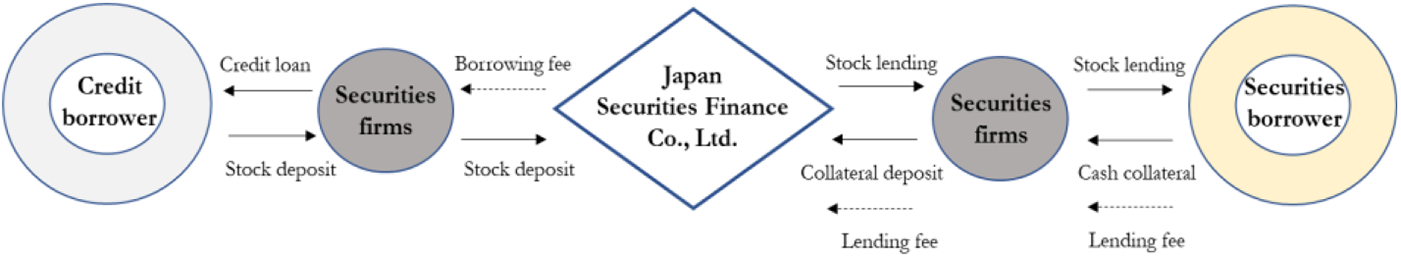

Apart from the statutory regulations directed at short selling activities, it is worth noting that Japan operates a securities lending (or stock loan) system especially designed for retail investors who engage in shorting a stock. As illustrated in Figure 3, Japan Securities Finance (JSF), a licensed company under the FIEA, plays a key role in this. Pooling loanable securities from institutional investors (mostly securities firms), JSF lends securities needed to settle trades to securities firms, which can then use these securities to extend loans to their retail clients. In doing so, it facilitates individual investors’ short sales, which are otherwise often unavailable. Relatedly, JSF provides securities lending services without having any predetermined limit. It may lend via securities firms as many shares of stock as short sellers demand to settle trades. If investor demand exceeds stocks held in JSF, it would fill the gap by purchasing stocks in the market.Footnote 130

Figure 3. Margin transactions and JSF’s stock loan services.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong is well-known for its strict short selling rules.Footnote 131 Naked shorting is an illegal practice, marking is required, and an uptick rule applies, although there exist exemptions for certain trading activities.Footnote 132 In addition, Hong Kong’s financial regulator, the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC), imposes reporting obligations on short sellers. The Securities and Futures (Short Position Reporting) Rules (LN 48 of 2012) establishes the reporting threshold for net short positions, which is determined as either ‘equal to or exceeding 0.02% of the market capitalisation of the issuer, or HK$30 million, whichever is lower’, and the SFC publishes the aggregated data on anonymous basis.Footnote 133 Moreover, Hong Kong has tight settlement rules; it has ‘implemented measures to prevent brokers from late delivery’.Footnote 134 If a failure to deliver occurs on the settlement day (ie, T+2), a compulsory buy-in process will be initiated.Footnote 135 Furthermore, infringements of statutory requirements constitute a criminal offence punishable by fine and imprisonment.Footnote 136

However, the most notable feature of Hong Kong’s regime is arguably the requirement that short selling orders on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEx) be limited to certain ‘Designated Securities’. The Rule of the HKEx provides that short selling is permitted only for securities that pass an eligibility test, and it sets out criteria to be considered as Designated Securities.Footnote 137 To be a shortable stock, among other things, it must have sufficiently large volume and high liquidity: eligibility criteria will be fulfilled, for example, when a stock has ‘market capitalisation of not less than HK$3 billion and an aggregate turnover during the preceding 12 months to market capitalisation ratio of not less than 60%’.Footnote 138

Some commentators argue that Hong Kong’s political and economic ties to China have been a critical factor in shaping its short selling system.Footnote 139 Presumably, its ‘close relationship with China and the politics surrounding its institutional governance’ have substantial influence over regulatory decisions made by market authorities.Footnote 140 In actuality, HKEx, which determines the list of Designated Securities eligible for short selling, is under the supervision of the SFC, whose board members are appointed by the Chief Executive of Hong Kong (head of the government), and its largest shareholder is the Hong Kong Government (with 5.9% of holding as of the end of 2022).Footnote 141 In light of this, some scholars suggest the likelihood that there have been ‘regulatory collaborations between China and Hong Kong’ and that regulators have ‘preferences for protecting issuers in which Chinese institutional investors have ownership interests from short sellers’ by excluding them from the list of Designated Securities eligible for short selling.Footnote 142 The same reasoning applies to dual-listed companies: For stocks that are both ‘listed on Mainland Chinese exchanges and HKEx, shorting may be strategically banned’ to reduce price impacts across the markets.Footnote 143

The Korean short selling regime in comparison

Korea’s short selling regime is claimed by the government to be the most rigorous compared to many other systems.Footnote 144 In actuality, the ongoing reforms and policy developments have all encompassed a wide array of short sale-related measures that are implemented in major jurisdictions. Table 1 highlights the historical development of short selling regulation in Korea.

Table 1. Timeline: a brief history of short selling regulation in Korea

Source: Korea Exchange (https://data.krx.co.kr/contents/MDC/MDI/mdiLoader/index.cmd?menuId=MDC0203).

First, naked short selling is strictly prohibited under the provision of the Financial Investment Services and Capital Markets Act (FSCMA). In order to place a short-sell order, investors are required to either borrow the share or obtain a confirmation to borrow it beforehand.Footnote 145 Next, many rules and regulations have been enacted to enhance market transparency, including comprehensive reporting and disclosure obligations. As per the Korean rules, marking (ie, flagging orders) is required, and short sellers are obliged to ‘file a report with the Financial Services Commission (FSC) and an exchange (which indicates the Korea Exchange, KRX)’, detailing their net position if it exceeds a specified threshold level, to be precise, 0.01% of the issued share capital of the company.Footnote 146 The disclosure (via an exchange) threshold has been aligned with the reporting obligation, reduced from 0.5% to 0.01% of the issued share capital or KRW 1 billion or more, effective 1 December 2024.Footnote 147 Furthermore, the rules include restrictions on short sellers’ participation in public offerings. Investors who have ‘sold short, or entrust short-selling orders on, may not cover short sales with the same stocks that they acquire through public offerings’ if the short sale trades are conducted within the period extending ‘from the day after the initial publication of the offering plan to the publicly announced valuation’.Footnote 148 Additionally, the uptick rule (plus or zero-plus tick test) applies as outlined in Articles 17 and 18 of the Business Regulations of the KRX.

Relatedly, an important observation is that market makers are subject to the price test restrictions as well. The Korean government discontinued the ‘uptick rule exemption for market makers in stock markets to address the issue of unfair treatment of market participants’.Footnote 149 In addition to imposing the tick test, the market authority has also prohibited market makers from selling short ‘mini-KOSPI 200 futures and options (when acting in their capacity as market makers)’ and imposed certain constraints on market making for high-liquidity items, with the aim of ‘encouraging low liquidity share trades’.Footnote 150

Besides, the financial regulators mandate that the KRX restrict covered short selling of securities designated as ‘overheated short selling stock items’ in accordance with regulatory guidelines. According to the KRX rules, any security traded in the Korean stock market becomes an overheated short sale issue when all the following conditions are met: either (i) a daily decline in stock prices by 5% to 10%, (ii) a short selling proportion that exceeds three times the proportion observed in the preceding quarter, and (iii) short sale transactions that surpass six times the average trading value of short sales recorded over the preceding 40-day period, or (i) a daily decline in stock prices by 10% or more and (ii) short sale transactions that surpass six times the average trading value of short sales recorded over the preceding 40-day period. In addition, the FSC recently added new criteria for designating such stocks: a share of stock is designated as an overheated short selling stock item ‘when the percentage of short orders reaches 30% or higher, regardless of relatively low price decline (3% or more) and a modest increase in the volume of short selling transactions (twice or more)’.Footnote 151 Further, it has made the restriction renewed on an ongoing basis, by ‘automatically extending the application of short-selling ban when stock prices decline 5% or more’.Footnote 152 Also, there are rules empowering regulators to impose prohibitions on short selling in exceptional circumstances. Article 180(3) of the FSCMA recognises the FSC’s authority to restrict ‘covered short selling, upon request from an exchange, by specifying the scope of listed securities, types of sales, time limits, and other relevant factors’, if it is likely to undermine securities market stability and to impede the formation of fair market prices.

At the enforcement level, the Korean government has toughened sanctions against illegal practices of short selling (such as naked short selling). In the past, unlawful transactions relating to short sales were punishable by minor administrative fines or cautions, which faced significant criticism for their lack of deterrent effect.Footnote 153 Thus, the revised FSCMA, which came into effect on 6 April 2021, introduced a penalty surcharge for violators of short selling rules ‘within the amount of illegal short orders placed’.Footnote 154 Additionally, it now imposes the severest level of criminal sanctions available under the current FSCMA, specifically punishing by ‘imprisonment for at least one year or by a fine equivalent to four to six times the profit accrued or loss avoided by a violation’.Footnote 155

All these rules, in effect, reflect the government’s commitment to keeping abreast of international standards. It can be tricky to make like-for-like comparisons between jurisdictions, but, as shown in Table 2, the Korean authority has incorporated short selling rules of other major jurisdictions exhaustively into its regulatory toolkit. This is why the Korean short selling regime is frequently blamed for its intricate and burdensome nature.

Table 2. International comparison of short selling regimes

Note: In jurisdictions where the individual public disclosure regime is not in operation (such as the US, the UK, and Hong Kong), regulatory bodies periodically publish the aggregated data pertaining to short positions by issuer instead.

Issue analysis and suggestions for improvement

One of the most pressing issues at present regarding the regulation of short selling in Korea is whether and how to liberalise the trading activities that the government banned all of a sudden, effective from 6 November 2023 until the end of March 2025.Footnote 156 Just before this emergency action was taken, short selling was restricted to stocks listed on the KOSPI 200 and KOSDAQ 150 indices. This sort of eligibility criterion, resembling the approach taken in Hong Kong, was enforced on 3 May 2021, with the objective of mitigating the impact of short selling on the markets.Footnote 157

In fact, the market authority’s recent decision to reimpose a full ban on the practice of short selling was not predicted at all. Up until recently, regulators were considering lifting the remaining restrictions at the earliest opportunity, subject to certain conditions being met, such as a pause on interest rate hikes in recognition that the restriction was impeding foreign traders from investing in domestic stocks.Footnote 158 The impediment to trading by foreign investors (including short sellers) was a significant concern for the Korean government, which has been striving for inclusion of its domestic market in the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) developed market index. To be eligible for inclusion in the MSCI index, it is required to fully lift curbs on shorting a stock; thus, a ban or restriction on short selling is commonly viewed as an obstacle to attaining this objective.Footnote 159

However, such a deregulatory mood swiftly transitioned to its opposite. The FSC argued in a policy statement that stock price volatility in domestic markets has recently ‘risen to much higher levels compared to other major markets, which caused anxiety in the market’.Footnote 160 Also, it added that several instances of illicit trading practices undertaken by foreign and institutional investors have been detected, contributing to the erosion of public trust in the markets.Footnote 161 According to the enforcement authority, an ongoing investigation of large-scale naked short selling involving global investment banks is underway, revealing further instances of unlawful activities.Footnote 162

On a related note, regulators are currently seeking to establish a new system that would ‘root out the illegal practice once short selling resumes thereafter’.Footnote 163 Furthermore, the Korean government set out a plan to ‘work on improving the system in a way that levels the playing field between institutional and retail investors’.Footnote 164 Specifically, the FSC is considering an option to ‘loosen stock short-selling rules for retail investors, while tightening rules for institutional and foreign investors’, which is an unprecedented policy move.Footnote 165

To be sure, short selling regulation stands as a highly politicised topic in Korea, coupled with increased public scrutiny and interest. Political interference has further complicated the matter, causing regulators to often stray off the course and revise their approach on an ad hoc basis. The ensuing arguments tackle some vexing problems confronting the Korean government and offer some suggestions to improve the system, resolving the unsettled issues surrounding the regulation of short selling.

Revamping the archaic system based on a principled approach

When tackling highly politicised and convoluted issues such as short selling regulation, the best policy is to establish the indubitable principle of enforcing the rules, weighing the benefits and risks. This perspective enables regulators to focus on the fundamental problems, aiming for viable solutions to meet them rather than merely replicating or adopting practices of other jurisdictions. Additionally, this approach can help avoid bias toward popularity or existing social conventions when making tough regulatory decisions.

The question of whether and how to regulate short selling should be addressed in terms of the need for government policy to correct a market failure. Market failure here refers to a broader situation in which a market does not function properly due to multiple reasons, including investors’ behavioural traits such as ‘irrational exuberance and irrational pessimism’.Footnote 166 When a market by itself does not suffice to bring fairness and efficiency for investors, regulatory intervention would be reasonable and justifiable. Further, if government intervention is deemed necessary, a credible cost-benefit analysis (mainly in the form of empirical assessment, not merely past experiences or a rule of thumb) would be required to implement appropriate measures in a proportionate manner. Given the substantial likelihood that unintended adverse consequences of regulatory decisions cancel out the social benefits, government authorities ought to be cautious in crafting rules and regulations.

As is well known, the foremost principle of short selling regulation is ‘facilitating short selling and the benefits it provides to the orderly and effective functioning of the market, while protecting against risks’.Footnote 167 Thus, it is crucial to ensure that this balance is correctly met in the regulatory system. This is exactly what the IOSCO made clear in its final report: short selling should be regulated to control the risks that could have a detrimental effect on the ‘orderly and efficient functioning and stability of financial markets’.Footnote 168 With such risks contained, however, the practice of short selling should be promoted to fully capitalise on investment prospects.

In light of this, the Korean regime for short selling has deviated from the regulatory features delineated by the foundational principle referred to above, being swayed by the enduring influence exerted by diverse policy stakeholders, such as politicians and civil society groups. Faced with such pressures, the Korean government has resorted to an expedient strategy, incorporating regulatory measures of other major jurisdictions into its domestic legal system. Additionally, the market authority has introduced some idiosyncratic rules on an ad hoc basis, resulting in the presence of overly complicated and rigid short selling regulations.

Against this backdrop, it is no wonder that there are vigorous arguments advocating for a complete overhaul of the Korean short selling regime to ensure its alignment with the overarching policy objectives. Market authorities need to be first ‘clear about what they are seeking to achieve via regulation’.Footnote 169 Regulators must remember that short selling bans and market restrictions may have reasonable grounds during moments of crisis, particularly when shorting securities has the potential to destabilise the financial system and impair the orderly functioning of markets. Short selling that occurs during periods of market turbulence tends to be ‘uninformed and consequently does not provide beneficial information’ to the markets, and only drawbacks can be made manifest.Footnote 170 All these observations are consistent with the existing empirical evidence.Footnote 171 However, tying the hands of short sellers in normal times would only degrade market quality, impeding price discovery and reducing pricing efficiency.Footnote 172

Naked short selling prohibition serves a prophylactic purpose: such a practice can trigger market disruptions, or be the cause of a systemic crisis.Footnote 173 Moreover, the somewhat tight reporting and disclosure regime is acceptable given the need for enhancing market transparency and regulators’ capabilities to do their job properly in today’s fast paced, ever changing market environments.Footnote 174 A too-low threshold comes with a caveat, though, that it may create lots of ‘white noise, making it difficult for regulators to draw sensible conclusions from the data’.Footnote 175 Also, when it comes to public disclosure obligations, regulators need to be cautious because revealing the identities of short sellers carries the risk of discouraging short selling activity, which could, in turn, reduce overall market liquidity.Footnote 176 Relatedly there is another risk that ‘public disclosure by an influential short seller’ could trigger herding behaviour, which could thereby ‘reinforce price tendency and exacerbate a downward spiral’ in a declining market - precisely the outcome that the regulators strive to prevent.Footnote 177 In light of this, the stringent transparency requirements in Korea’s short selling regime are likely to have a detrimental impact on the market. Therefore, it would be preferable for market authorities to rethink these rules and align the regulatory standards more closely with those of other markets (such as the US or the UK). Meanwhile, the Hong Kong style eligibility test (ie, an exchange’s designation of securities eligible for short selling) is not a well-established method and easily susceptible to political influences. Therefore, the Korean government needs to scrap this method when it lifts the current ban on short sale trading (which is scheduled at the end of March 2025).

Furthermore, it should be noted that Korea’s short selling rules are more stringent compared to those of major jurisdictions around the world. To be precise, it is the manner in which these rules are applied and enforced, rather than the regulatory system itself, that has resulted in Korea’s short selling regulations being the strictest. Therefore, they need to be relaxed to support stock market functioning and mitigate the adverse effects of trading constraints on market competitiveness. For example, the Korean version of an uptick rule is always in effect, enabling it to be enforced more frequently. There is a need for adding a new mechanism such as a circuit breaker to the existing tick test rule so that it may be triggered into effect only when share prices go into freefall (which is consistent with the approach taken in the US and Japan). Relatedly, a modified uptick rule can be much more sophisticated. Specifically, it is possible for the tick test rule to be designed in a way that reflects

a percentage fall in the market price as compared to a weighted average price comprising the previous day’s closing price, which should be assigned the biggest weight, the average closing price of the preceding week and the average closing price of the preceding month, which is assigned the lowest weight.Footnote 178

Under such a rule, the circuit breaker halt would not likely be activated with excessive frequency, allowing it to ‘capture market trends that extend beyond a day’s trading’.Footnote 179

Further, the designation rules of ‘overheated short selling stock items’ de facto serve a function that is akin to that of the short-sale-related circuit breaker system referred to above in that it temporarily halts transactions to prevent a market disruption arising from short selling.Footnote 180 The Korean government has consistently expanded the scope of the regulation since its inception, and in particular, recently extended the short selling ban on designated stocks from 1 to 10 trading days.Footnote 181 Compared with EU and US rules, which specify a 2-day limit, this 10-day duration is too long.Footnote 182 Restrictions on trading must be of reasonable duration, and thus the period should be shorter. Or alternatively, regulators may opt to repeal whichever regulation is found to be less effective given their functional overlap.Footnote 183

Additionally, the Korean government has significantly narrowed the scope of regulatory exemption permitted to market makers. The market authority has recently introduced some constraints on short sale trades and ‘discontinued the uptick rule exemption for market makers’.Footnote 184 Certainly, these were intended to mollify aggrieved retail investors alleging that market makers are given unfair preferential treatment in the marketplace.Footnote 185 However, market makers are obliged to continuously quote prices at which they will buy or sell a stock; they commit to standing ready to trade at all times and during all market outlooks. In order to place bids for securities that are not held, or otherwise to provide more liquidity to the market as needed, market makers should be able to freely engage in short selling. Therefore, bona fide market making (as well as hedging and arbitrage transactions) must be restored as ‘exempted activities for efficient market functioning and development’.Footnote 186

Finally, as noted earlier, short selling is a trading practice that is typically and widely accepted in the capital markets; it is lawful to the extent that it does not qualify as market abuse. As with other major jurisdictions, the Korean law has its own regulatory regime to combat financial misconduct. In this respect, it seems to be problematic that short selling provisions (Articles 180 to 180-5 thereunder) are currently written within the FSCMA under the heading of ‘unfair trading’ (market abuse). They need to be separately stipulated in the law.

Turning a regulatory challenge into trust through commitment to accountability in law enforcement

No matter how hard the government strives to revamp the regulatory system in alignment with a principled approach, achieving this goal is improbable in the absence of trust in market institutions. The term trust refers to ‘a willingness to accept vulnerability under conditions of uncertainty’.Footnote 187 Accordingly, the more trusting investors are in the market, the more effective regulatory interventions (which could be unfavourable decisions to the investors) will be. Conversely, investors will ‘leave the market when they lose trust in the market system’.Footnote 188 Or otherwise, even if suspicious investors do not actually leave the market, such a lack of confidence ‘will undermine regulatory effectiveness’.Footnote 189 In particular, it is well documented that ‘transaction costs that investors incur when trading on public (or impersonal) markets become extraordinarily high’ without trust, resulting in a loss of trading opportunities that could have been mutually beneficial.Footnote 190 In such circumstances, equity investors might choose not to participate in transactions involving ‘abstract and intangible assets, such as corporate securities’, and instead shift their interest towards alternative ‘tangible assets, such as commodities and real estate’.Footnote 191 Thus, it can be said that the significance of investor trust to the securities market is ‘proven by the very existence of the market’.Footnote 192

Noteworthy is the fact that investors’ trust originates from faith in the integrity of the market system, rather than faith in the honesty or reliability of other market participants. Investors participate in the capital markets ‘not because they trust managers, brokers, and investment advisers, but because they rely on the legal system to discourage their counterparts from behaving like the scoundrels’.Footnote 193 Simply put, investors are willing to engage in market transactions due to the existence of ‘some degree of government-imposed protection’.Footnote 194 A well-designed regulation is also beneficial to industry players such as financial institutions. It provides them with ‘government support in their efforts to gain investors’ trust in the financial market’.Footnote 195 By offering the regulated entities a ‘stamp of good housekeeping’, regulators can reduce not only investors’ costs in ‘monitoring issuers and institutions’ but also institutions’ costs in ‘convincing investors of their trustworthiness’.Footnote 196

The importance of investor trust to the securities markets is more pronounced ‘when prices fall; in particular, it becomes more meaningful during or immediately after a crash’.Footnote 197 When markets collapse and investors lose large sums of money, they are likely to be sceptical of market integrity. Even investors who attribute the economic loss to their poor judgement tend to harbour ‘suspicions that something wrong in the system caused the crash’.Footnote 198 Given that short selling is prevalent in bear markets, regulators should be able to intervene in short sale transactions to prevent investor pessimism from reaching extreme levels that could erode trust in market institutions. To this end, as discussed earlier, short selling bans and restrictions can be used to temporarily halt or limit trading activities. However, at a more fundamental level, establishing a favourable reputation for regulators characterised by objectivity and impartiality is essential to restoring investor trust, and the government must develop regulations with this goal in mind.

If so, how can regulators effectively cultivate their reputation and foster public trust in market institutions? The answer lies in ensuring the credibility of regulatory policy enforcement, among other things. This is simply because ‘trust is learned’: whether or not to trust counterparts (including market authorities) heavily depends on ‘one’s past experiences in similar situations’.Footnote 199 Therefore, a government that has a poor track record in credibility (which often arises due to time-inconsistent policy making) is at potential risk of falling into the ‘Tacitus Trap – an existential legitimacy crisis caused by losing the confidence of the public’.Footnote 200 Once the trap is sprung, regulators would likely face widespread resistance from distrustful market participants, irrespective of their genuine intent and policy effectiveness.

In this context, exercising some restraint over the extensive authority currently vested in the Korean government seems required to restore trust in regulatory practices. Notably, Article 180(3) of the FSCMA, which empowers the FSC to temporarily ban short sales of certain stocks in exceptional circumstances, does not set out any predictable standards for the emergency market intervention. Specifically, the statutory provision merely stipulates that the FSC ‘may, at the request from an exchange, restrict the covered short sale by determining the scope of listed securities and the types of sales transactions, if it is likely to undermine the stability of the securities market and formation of fair market prices’, not providing further detail of when or how the Commission considers it will use its emergency powers. Simply put, the authorities are entirely at the government’s discretion. It is therefore presumed that regulators have an incentive to be more reliant on such a contingency measure in times of stress. In actuality, the Korean government has issued bans on short selling during the acute phase of crisis more often than not, and once the measures are taken, they have lasted for prolonged periods of time (see Table 3).Footnote 201

Table 3. Short selling bans issued in times of stress

Source: Financial Services Commission.

Delegating government powers that involve a wide margin of discretion and policy decisions may pose a significant challenge to the consistent and predictable application of the law. It would thus be imperative to establish some clarity on this rule. In particular, setting the criteria for a triggering condition and an expiration date will be required; more specifically, a new provision that draws a contour map of the triggering event needs to be written in the enforcement decree of the FSCMA. Regulators should be able to explain what is meant by the market condition that will ‘likely impair financial stability and the mechanism of price formation’. Specifically, the market authority may suggest some metrics, such as certain consecutive days exceeding a daily trading limit (ie, the maximum price range limit that is allowed to fluctuate, currently set at 30% in Korea) and a doubling period of market volatility indicators; though, of course, this only exemplifies the application of some criteria and would merit a rigorous empirical evaluation. Furthermore, establishing the period of restrictions (eg, up to three months, as with EU rules) and specifying conditions for extending any temporary measures are necessary for promoting accountability in law enforcement.Footnote 202

Another important way to foster trust in a regulatory regime involves authorities enforcing the law in an objective and impartial manner. Punishment for violations of the law should be proportional to their severity and fairly administered. Failing which, the public will lose confidence in their legal system, showing reluctance to obey the rules. In this respect, the Korean short selling regime has not garnered trust among the investing public enough to warrant their acceptance of policy decisions they oppose. The government had not established the severe penal system to prevent financial crime involving the illegal practice of short selling until the 2021 amendment to the FSCMA, and had long been under criticism for its wishy-washy attitude when penalising abusive short trades.Footnote 203 Indeed, as Table 4 shows, short sellers who breached the short selling rules were only subjected to minor administrative fines or cautions until more severe penalties were imposed for the first time in March 2023.Footnote 204

Table 4. Sanction records for short selling law violations for the period 2010-2022

Source: Financial Supervisory Service.

With the introduction of new sanctions and disciplinary measures, the market authority’s commitment to enforcing the regulations against illicit short trades will be reinforced. As noted earlier, the Korean government has implemented the toughest criminal rules regarding unlawful short sale transactions compared to any major jurisdiction. Certainly, this is to improve the efficacy of law enforcement in terms of deterring violations of short selling rules; given constraints in supervisory budgets and resources, regulators may as well ‘focus more on increasing severity of punishment (rather) than on increasing the probability of detection’.Footnote 205

However, it should be noted that such an enforcement strategy will only be effective among conservative (ie, ‘risk averse’) investors. Much literature on law and economics highlights that risk averse investors who prefer certainty over potential gains are ‘deterred more by increases in the severity of punishment than an equivalent increase in the probability of punishment, while risk lovers are deterred more by increases in the probability of detection’.Footnote 206 Here arises the question as to whether short sellers can be classified as risk-averse investors. Considering the inherent characteristics of leveraged investing and the major participants (eg, hedge funds) in the market, it is conceivable that short sellers do not, in fact, align with the profile of conservative investors. If that is the case, regulators had better ‘opt for close monitoring and assume that when the detection rate is high, punishing to the minimum necessary extent will suffice’.Footnote 207 To be sure, this issue merits further examination.Footnote 208 Nonetheless, what is clear is that severe punishment alone is not the panacea and that authorities should steer clear of overcriminalisation and disproportionate punitive measures.

Preventing undue political influence by conducting prudent short selling policy

Regulatory independence plays a pivotal role in ‘helping to protect regulators by safeguarding their decision-making process against undue political influence’ and in ‘helping to guard against some forms of industry capture’.Footnote 209 For this reason, regulators seek to achieve independence to fulfil their mandate. Mounting evidence suggests that political interference not only degrades the quality of regulation but also even ‘cripples the financial system in the run-up to the financial crisis’.Footnote 210

However, in reality, regulatory authorities are ‘at once independent and beholden’. Even if they are ‘independent executive agencies that function outside the administration and, unlike a cabinet agency, have the ability to work’ autonomously, they are subject to political oversight, which necessitates their ‘compliance with the request of the legislature’ and includes its extensive scrutiny of the functioning, operating, and budgeting of the regulatory bodies.Footnote 211 There can be a trade-off between regulatory independence and accountability (a sine qua non for regulatory trust). Overemphasising accountability may reduce independence; conversely, stressing too much the role of independence may reduce accountability.Footnote 212 Therefore, balancing these two competing goals is needed, but in practice, it is easier said than done.Footnote 213

The unique feature of the market environment in Korea renders the issue more challenging to address. Among others, retail investors’ holdings are notably higher in the Korean stock market compared to their counterparts in other advanced economies. As of 2022, approximately 53% of the total trading volume in Korea originates from retail investors. During the pandemic-fuelled trading frenzy of 2020, it recorded a historic high of 66%, followed by 63% in 2021.Footnote 214 By contrast, in 2020, US retail investors accounted for about 20% of the total trading volume, while over the preceding decade, this percentage fluctuated between 10 and 15%.Footnote 215 The number is reportedly lower in the EU: even though retail investor participation has doubled since 2020 and is now approaching 20%, their activities ‘made up only 5 to 7% of total trading volume’ during the past decade.Footnote 216

However, the real issue surrounding short selling activity lies in the market dominance of foreign and institutional investors. According to the FSC, immediately prior to the onset of COVID-19 (as of 2019), short selling in the KOSPI market represented a mere 2.4% of total trading issues and 6.4% of trading volume, but more than 98% of these transactions were attributable to foreign and institutional investors.Footnote 217 Table 5 demonstrates that their prevailing position has remained unchanged despite the imposition of short selling constraints in 2020.

Table 5. Short sale transactions by types of investors for the period 2019-2021 (in 100million KRW)

Source: Financial Services Commission. Note: Numbers in parentheses indicate the percentage (%) of short sales turnover by each type of investors.