Introduction

The current global power competition is opening stimulating conceptual perspectives for students of international relations. While traditional debates used to pit realism, with its emphasis on military competition, against liberalism, with its emphasis on economic cooperation, growing scholarly interest in geoeconomics, economic sanctions, trade wars, and, more generally, the overlapping of international economic and security policies tends to blur this cleavage.Footnote 1 Concepts such as ‘weaponized interdependence’,Footnote 2 the ‘balance of dependence’,Footnote 3 or ‘predatory liberalism’Footnote 4 contribute to building bridges between paradigms by combining the notions of ‘dependence’ and ‘interdependence’, which are traditionally used by students of international political economy, with the mechanisms of coercion and ‘balancing’, which are dear to realist students of military rivalry. If asymmetric interdependence can be ‘weaponised’ against competitors and if threatened states are incentivised to seek to ‘balance’ dependence to protect themselves, then the concept of dependence seems increasingly close to that of power.

This welcome convergence invites us to revisit the rich debate on the relationship between power and dependence and consider that power and dependence can both apply to the economic and military spheres and can be conceived as two sides – active and passive – of the same relationship.Footnote 5 In other words, if actor A depends on actor B, B has power over A. This conceptualisation also highlights a theoretical problem. Consider a relationship where state A has power over state B while B has equivalent power over A. From a realist perspective, this relationship is analysed as a balance of power between A and B, which tends to protect each side against the power of the other by allowing them to ‘prevent’ domination and ‘deter’ aggression.Footnote 6 However, from a liberal perspective, this relationship is analysed as an interdependence that potentially poses coordination and uncertainty problems. To respond to these issues, states may be encouraged to establish international institutionsFootnote 7 or even transfer part of their respective powers to a supranational organisation tasked with the management of their interdependence.Footnote 8

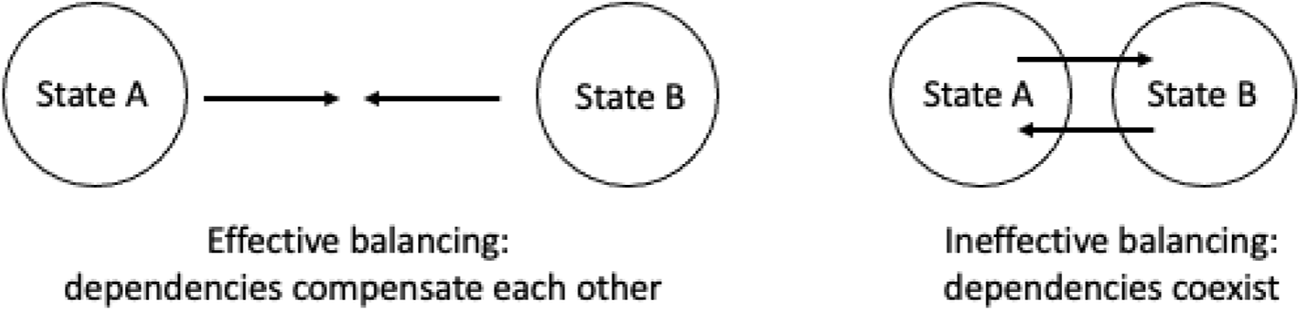

It thus appears that the same situation – A has power over B and vice versa – can lead to two radically opposite mechanisms: the realist horizontal logic of the balance among states and the liberal vertical logic of power centralisation into a supranational organisation able to impose its decisions on states. Whereas balancing reflects the anarchic logic of ‘mutual adaptation’, integration follows the hierarchical logic of ‘super- and subordination’ (Figure 1).Footnote 9

Figure 1. Balancing and integrating.

I argue that providing a typology of the relationships between power and dependence can help us better understand the way in which states navigate between balancing and integration and, more generally, help bridge the divide between realist and liberal perspectives.

Security studies offer a rich typology of strategies that states can adopt, which not only includes balancing but also ‘bandwagoning’ by joining forces with a powerful competitor;Footnote 10 ‘buck-passing’Footnote 11 by free riding on the balancing efforts of others; institutional ‘binding’, in which states bandwagon in exchange for the establishment of rules that restrain the arbitrary exercise of the hegemon’s power;Footnote 12 and ‘hedging’, which combines elements of both balancing and bandwagoning.Footnote 13 As for institutionalists, they have detailed the various typical coordination problems that can lead states to establish international institutions: uncertainty, transaction costs, non-credible commitments, and free riding.Footnote 14

Here, I explore a third intermediary dimension, namely, the different possible relationships not between states, but rather between the powers and dependencies that link those states. These relationships can act as the mechanism underlying an effective strategy (for example, A may effectively balance B by relying on the fact that A’s power over B tends to limit B’s power over A), and they also reveal coordination problems that can make international organisations either more or less useful or more or less hindering. In other words, a power–dependence relationship is not a mere strategy or problem, but rather a structure in which strategies and problems meet.

Although students of the convergence between interdependence and power have offered typologies of the various measures used in geoeconomic competition, distinguishing among ‘shielding’, stifling, and spurring’Footnote 15 or between offensive and defensive measures,Footnote 16 they have not fully explored the structure of power–dependence relations. Here, I distinguish three main kinds of power–dependence relationships:

- Limitation: A’s power over B (or B’s dependence on A) can directly restrict B’s power over A;

- Neutralisation: A’s power over B can make it costly for B to use its power over A to harm A, particularly by mobilising A’s capacity to harm B in return, thus alleviating A’s dependence on B;

- Competition: A is simultaneously dependent on B and C, and investing power to address its dependence on B can reduce A’s ability to address its dependence on C.

First, when state A’s power over state B can limit or neutralise its dependence on B, power and dependence compensate for each other, which means that a balancing strategy can be effective in protecting A against the negative effects of its dependence on B. On the other hand, if A’s power over B cannot limit or neutralise A’s dependence on B, even if the A–B power relationship is symmetrical, then the balancing strategy will be ineffective in protecting A. A’s dependence on B and B’s dependence on A will simply coexist without offsetting each other. As a response to this problem, centralising A’s power over B and B’s power over A in a supranational organisation, by removing decisions from both states’ direct control, can provide stronger guarantees and become an attractive alternative.

Second, if state A is dependent on two different sources of dependence, B and C, and these two dependencies compete with each other, then integration with B but without C risks reducing A’s flexibility and hindering its ability to invest power to address its dependence on C. In this case, surrendering autonomy to a supranational organisation risks making A more vulnerable to C, which renders integration unattractive. Overall, the structure of the power–dependence relationship tends to shape the relative attractiveness of autonomy versus centralisation.

Empirically, I illustrate these mechanisms by showing that post-war European integration started as a response to a situation of cross-temporal interdependence between France and West Germany, which tended to make limitation and neutralisation unreliable. However, military integration was later hindered by the tension between competing sources of dependence for France, which increased the cost of the loss of flexibility entailed by centralisation. Revisiting the early history of European integration through the prism of power–dependence relations thus sheds new light on the question of the transition between balancing and integration.

The alternative between balancing and integrating

Although a wealth of literature has offered compelling explanations of European integration, most authors have largely neglected the problem of the alternative between balancing and integrating. Liberals see integration as a way of managing interdependence between European states when there is uncertainty about future decisions, but do not fully consider balancing strategies as a viable alternative.Footnote 17 This bias is explicit in Moravcsik’s approach, which assumes that coercion and punitive sanctions are ‘not cost-effective negotiating tactics among European democracies’.Footnote 18 However, states faced with interdependence and uncertainty may use balancing strategies to constrain or weaken their competitor. For example, faced with the risk of dependence on recovered German power, French post-war decision-makers opted initially not for integration but rather for a balancing strategy consisting of an effort to divide Germany politically and to weaken it economically and militarily while forming anti-German alliances. Liberal historian Milward blames the ‘economic irrationality’Footnote 19 of France’s initial strategy and accuses it of having come ‘so close to repeating the economic errors’ of the Versailles Treaty.Footnote 20 Similarly, Ikenberry sees supranational integration as an extreme form of institutional binding,Footnote 21 which he considers more likely to be a post-war settlement when the leading state’s power advantage is large and among democracies. However, these variables cannot explain the sudden shift from balancing to integration, such as in the case of post-war France. Ikenberry does not fully explore the comparative advantages of balancing and simply sees binding as the superior strategy.Footnote 22 Liberals thus tend to rule out balancing as an irrational or less advanced strategy.

Realists generally see integration as part of a balancing strategy, be it hard balancing against the Soviet Union in the 1950sFootnote 23 or soft balancing against the United States in the 2000s.Footnote 24 However, these explanations display a gap between the application of a realist logic of balancing vis-à-vis extra-European states on the one hand, and a liberal logic of seeking ‘efficiency’ in collective action through integration regarding relations between European states on the other hand.Footnote 25 As Howorth and Menon put it, ‘What the soft balancers fail to appreciate is that [the] logic of international politics applies within the EU in much the same way as it does in its relations with the outside world’.Footnote 26 In the 1950s, it is not completely clear why the French prioritised the collective efficiency of managing their power relationship with West Germany through integration over the preservation of their national autonomy through the balancing option. Indeed, in the pure neorealist logic, in which states seek to preserve their sovereignty, integrating to better balance an external threat is similar to ‘committing suicide out of fear of death’.Footnote 27

A second group of realists view balancing and integrating as two opposite logics.Footnote 28 However, to explain how states navigate between these two strategies, they largely rely on ad hoc unit-level ideational variables, particularly the way leaders ‘learned from history’.Footnote 29 Finally, Eilstrup-Sangiovanni sees integration as a solution to avoid a preventive war between a dominant and a rising state.Footnote 30 The purpose of the supranational organisation is to restrain the exercise of the rising state’s power so that the initial power relation is ‘frozen’, and the dominant state does not have an incentive to attack before power shifts. Theoretically, the problem is that such an objective would require only the unilateral transfer of the rising state’s growing power,Footnote 31 not integration, which implies reciprocal power transfers from both sides.

Overall, because liberals and realists have not provided a precise explanation of how states move from balancing to integration, this problem has mainly been addressed by constructivists, who show that decision-makers’ ideas and beliefs play a role in the way they arbitrate between different logics.Footnote 32

Balancing, integration, and power–dependence relations

In this section, I present a theory of power–dependence relations explaining how states arbitrate between the logics of balancing and integrating.

Definitions

The concepts of dependence and interdependence are often limited to the economic sphere,Footnote 33 but their association with the notion of power highlights their broader value. Indeed, the concepts can also apply to ‘strategic’ or ‘military’ relations.Footnote 34 Moreover, although some authors limit dependence to situations in which the breaking of a relationship based on exchanges has costly effects,Footnote 35 herein, I include situations in which an actor could directly impose costly effects on another, such as in the case of a military threat.Footnote 36 In other words, here, dependence means vulnerability to an external actor’s power. Dependence is also relevant in alliance politics. At the primary level, an actor is dependent because it can be directly harmed by another actor; at the secondary level, an actor is dependent because it needs an ally’s assistance and thus would be indirectly harmed in the event of abandonment.Footnote 37

As for the notion of power, its connection with dependence highlights its relational dimension, that is, not only how A’s capabilities compare to B’sFootnote 38 but also how A’s capabilities can affect B and vice versa.Footnote 39 As such, power is not conceived here as a property of the power wielder, but as a relationship. More specifically, I define A’s power over B (or B’s dependence on A) as A’s capacity to harm, that is, to impose costs, on B, that is to say as a potential, not an outcome.Footnote 40 Finally, A is more or less autonomous vis-à-vis B to the extent that A can act without being constrained by a dependence on B.

The relationship between power and dependence has been widely discussed since the 1970s by realists and liberals alike. For Waltz, as an actor’s power increases, its dependence on others decreases.Footnote 41 Conversely, for many authors, if A depends on B less than B depends on A, it implies that A has power over B.Footnote 42 As such, dependence can be conceived as the opposite of power.Footnote 43 However, considering dependence as the opposite of power does not mean that A’s power over B will necessarily offset B’s power over A. These two relationships can simply coexist without weakening each other; we will see that this problem can render balancing strategies ineffective. In the following sections, I explore how power–dependence relationships affect the viability of two ways of managing a reciprocal power relationship (or interdependence), namely, balancing and integration.

Balancing

I assume that states seek to protect themselves from the costs that can potentially be inflicted on them by external actors. One way to do this is to balance this dependence.Footnote 44 If A is vulnerable to B’s power, A can balance this dependence by mobilising its own power or that of allies.Footnote 45 This balance-of-dependence strategy broadly corresponds to the logic of the balance of power, except that actors do not seek to balance power in absolute terms but only insofar as they depend on it and seek to preserve their autonomy. Some authors restrict the concept of balancing to the aggregation of military capabilities to prevent invasion.Footnote 46 However, states can mobilise all kinds of power resources to counter one another; such efforts include economic balancing.Footnote 47 Similarly, states may want to balance their competitors to preserve their autonomy against not only the risk of military invasion but also economic domination.Footnote 48

For a balancing strategy to be effective, A’s power over B must provide protection against B’s power over A. This can be achieved through reliance on two kinds of power–dependence relationships: limitation and neutralisation. A’s power can be used to directly restrict B’s capacity to harm A (limitation), for example, by reducing B’s capabilities. Alternatively, A can try to make it costly for B to harm A, particularly by mobilising A’s capacity to harm B in return (neutralisation). In this latter case, the reciprocal power relationship – or interdependence – can have a self-neutralising effect. If the relationship is balanced, each state’s capacity to harm the other constitutes a guarantee against the threat of the other. For example, if two states depend equally on each other’s trade, these vulnerabilities tend to neutralise each other, as neither side has an interest in harming the other by breaking the relationship. Similarly, if two states pose a nuclear threat to each other, the prospect of mutually assured destruction can neutralise those threats. This does not mean that neutralisation eliminates the possibility of conflicts. Nevertheless, actors’ efforts to make it costly for others to harm them can alleviate their vulnerability and tend to preserve their autonomy. However, if A is weak and unable to find adequate support to limit or neutralise its dependence on B – that is, if the power relationship is too asymmetrical – B will dominate A, which can force A to make costly concessions to B or even to bandwagon with B.

When balancing becomes unreliable

However, balancing strategies are not always reliable. Limitations can be impossible or too costly to achieve. For example, it can be very difficult to prevent a rival from acquiring threatening capabilities or to reduce dependence on a critical supplier. Even if A has power over B, it does not necessarily mean that A is able to significantly destroy B’s power over A. In this case, A’s power over B and B’s power over A will remain. Neutralisation can also be unreliable, even if the power relationship is symmetrical, to the extent that A’s power over B cannot make it costly for B to harm A, and vice versa. This can be the consequence of a time inconsistency problem.Footnote 49 Time inconsistency can occur particularly in the case of cross-temporal interdependence. If A has power over B today but expects to depend on B tomorrow, the mutual neutralisation of these dependencies is impossible because A’s power over B today cannot make it costly for B to exploit its future dominant position tomorrow. A can pressure B today, but B’s commitment to not exploit A when A is no longer able to make it costly for B would lack credibility. If A’s power over B today cannot limit A’s future dependence on B, for example, because A is not able to launch an effective preventive war against B,Footnote 50 then B will be vulnerable to A today, and A will be vulnerable to B tomorrow.

When balancing strategies are unreliable, even if the A–B power relationship is symmetrical, A will not be able to constrain B’s ability to harm A, and vice versa. Instead of compensating for each other, mutual vulnerabilities will coexist, which means that A and B will each remain exposed to the risk of costly effects imposed by the other (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effective and ineffective balancing.

Integration

When balancing strategies cannot provide effective guarantees against the costly effects of interdependence, actors might be tempted to turn to an alternative option. Integration provides a framework that can allow states to manage the implications of mutual vulnerabilities that do not limit or neutralise one another. The logic is that A’s power over B and B’s power over A are transferred to a supranational organisation through the pooling or delegation of decision-making.Footnote 51 Instead of directly depending on each other, states thus depend on this organisation, which has the power to impose decisions on them that may potentially go against their preferences, in areas in which these states would otherwise be able to adopt their own decisions. This process removes decisions from states’ direct control but also allows them to constrain each other indirectly via the centralised power of the organisation. When neutralisation is unreliable, integration can thus provide a stronger guarantee. In particular, integration allows states to make intertemporal transactions between present and future powers, which would not be possible if decisions remained decentralised.Footnote 52 If A has power over B today but expects to depend on B’s power tomorrow, the transfer of these powers to a supranational organisation can reduce A’s fear of being exploited tomorrow when A is no longer able to directly sanction B; conversely, integration provides B with immediate guarantees vis-à-vis A, even if B is not yet able to sanction A. This is not to say that integration provides absolute guarantees against future defection or conflicts (even unitary states are subject to the risks of secession or civil war). Integration can only increase the visibility and cost of the decision to return to unilateral decision-making.Footnote 53

Through integration, states not only reciprocally transfer their power to the supranational level but are also granted some powers within the organisation through the joint design and control of delegation or voice opportunity in pooled decisions.Footnote 54 In other words, they now seek to protect themselves not by preserving their autonomy but rather by participating from within in the centralised regulation of their interdependence. Integrated states still compete and mobilise their respective power, but to influence centralised institutions and prevent other members from capturing these institutions.Footnote 55 The international struggle for power is replaced by the struggle ‘to influence or control the controllers’.Footnote 56 The balancing logic is transferred to the domestic level within the integrated organisation, not among separate sovereign states but among integrated constitutional powers.

When integration becomes a hindrance

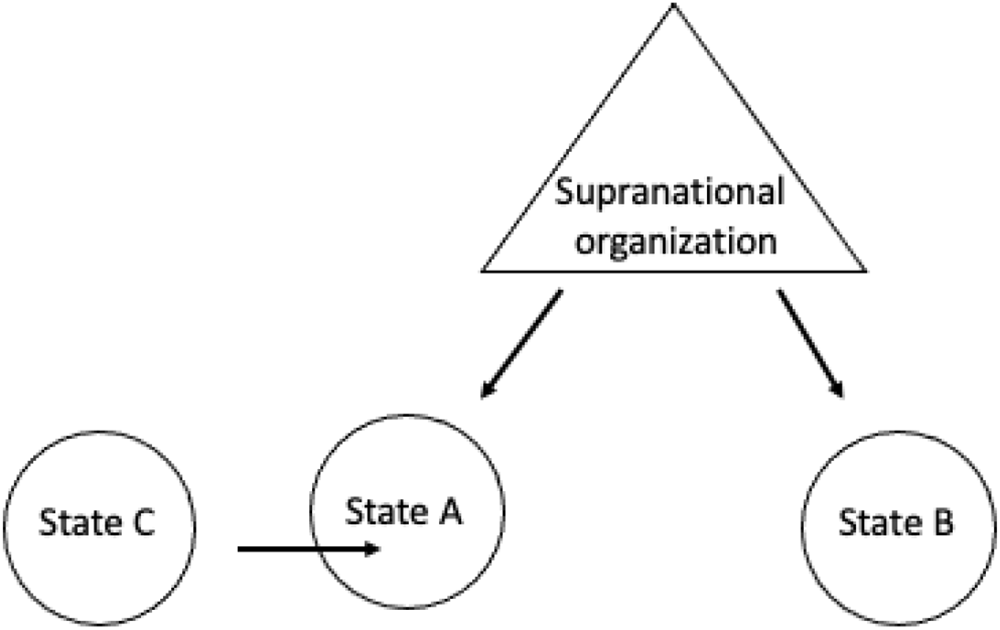

If integration can provide stronger guarantees than unreliable balancing strategies can, it also comes at a cost in terms of flexibility. Because it reduces states’ autonomy, integration makes interdependence easier to manage among integrated actors but at the expense of relations with other non-participant actors.Footnote 57 For A, integration with B may provide guarantees vis-à-vis one source of dependence while simultaneously constraining A’s ability to address other sources of dependence (C) involving other actors. If A’s dependencies compete with each other, that is, if A’s focus on B can reduce A’s ability to invest power to address its dependence on C, then the loss of flexibility entailed by integration can be costly (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Competing dependencies.

For example, because it removes some decisions from A’s direct control, integration can reduce A’s ability to focus its efforts alternatively on B or C depending on the context or to invest in multitasking solutions that can address both issues simultaneously. The more A depends on C, the greater the potential cost of A’s integration with B at the expense of A’s relations with C. Eventually, for A, the cost of the lost room for manoeuvring in its relationship with C risks being higher than the benefit that integration offers by imposing stronger constraints on B. Put differently, the cost of being constrained by integration with B can be greater than the benefit of better constraining B. For example, in the 1950s, the UK’s strong economic interdependence with the Commonwealth prevented it from joining the European Community.

At a secondary level, integration may also induce a loss of flexibility in terms of alliances because of the exclusive logic of supranational organisations.Footnote 58 Indeed, these organisations provide integrated actors with voice opportunities (e.g., voting rights) that allow them to contribute to the formation of internal decisions at the expense of non-members. Because they have surrendered part of their autonomy through delegation or pooling, member states have to follow these decisions reflecting the internal distribution of power, which hinders their ability to coordinate their efforts with external allies. As a consequence, integration can be a source of relative weakness if it partially cuts a member state from its non-member allies’ support. If A depends on C’s support to balance B, integration with B without C can make A more isolated in internal decision-making and thus relatively weak vis-à-vis B. For example, in the 1960s, the Netherlands feared that exclusion of the UK from the Community would increase the danger of a ‘Franco-German preponderance’.Footnote 59

Case studies and empirical hypotheses

To illustrate this theory, I focus on the origins of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and the failure of the European Defence Community (EDC). These cases are selected because they correspond to the very first steps of the European integration process and thus are likely to make empirically visible the problem of the transition from traditional balancing strategies to integration. Subsequent developments, such as the discussions that led to the 1957 treaties of Rome, took place in an environment that was at least partially shaped by the existence of ECSC institutions and the failure of the EDC.Footnote 60 The paradigm shift was thus purer and clearer in the first initiatives. The case of the EDC is included because it provides an example of integration failure and an opportunity to test hypotheses on the factors inhibiting integration.

I focus on France’s policy because France inspired both the ECSC and the EDC and was the one that eventually scuttled the EDC. The case of the first mover is particularly significant because states that join an already launched integration project may do so not because they see integration as an attractive option but because they fear the cost of exclusion.Footnote 61 In addition, while West Germany, the other major initiator, was a defeated power and did not enjoy full sovereignty after WWII, France was not only a sovereign state but also one of the main victorious powers occupying Germany. The transition from balancing strategies to a logic of integration represents a more radical and puzzling change in the case of France. An analysis of France’s policy cannot explain all of the dimensions of the European integration process; however, France, as a crucial actor,Footnote 62 provides a good case to illustrate a theory that seeks to account for how states arbitrate between balancing and integration.

In addition to secondary sources, this article relies on French archives. Empirical records were analysed through process tracing to assess to what extent the theoretical mechanisms discussed above were present and played out as expected.Footnote 63 The main empirical predictions derived from my theoretical arguments are as follows:

- First, the decreasing capacity of France’s power over Germany to limit or neutralise Germany’s future power tends to increase the unreliability of balancing and the attractiveness of integration.

- Second, the increasing importance of another dependence of France, in competition with its dependence on Germany, tends to cause the loss of flexibility that is entailed by integration with Germany to become a hindrance, which renders integration an unattractive option.

France between balancing and integrating (1944–54)

At the end of WWII, French leaders’ main security concern was that restored German power could again become a source of vulnerability for France: ‘If France were to suffer the onslaught of Germany a third time in the next few generations, it is to be feared that this time it would succumb once and for all.’Footnote 64

The balancing strategy

To respond to this vulnerability, France initially relied on a traditional balancing strategy. According to his Foreign Minister Georges Bidault, General de Gaulle, who led the French government from 1944 to 1946, saw Germany ‘according to the [1648] Treaties of Westphalia’ and thought that peace ‘could only be the result of Germany’s powerlessness’.Footnote 65 This strategy seemed viable at first because, as an occupying power, France had considerable power over Germany.

In terms of limitations, France used its military presence in Germany to support not only Germany’s disarmament and demilitarisation but also its political and economic weakening. Politically, France initially opposed the establishment of a central German government, a position later replaced by a demand for ‘the loosest possible federalism’.Footnote 66 Economically, French diplomats argued that

In the long term, the security of Western countries cannot be maintained if Germany is not deprived of most of its raw materials, such as coal, and of the facilities that are essential for the functioning of its steel and chemical industries.Footnote 67

The Ruhr had to be internationalised, and the Saar was included in the French customs territory; factories had to be transferred to the Allies, particularly those ‘directly usable for war purposes’.Footnote 68 This policy aimed at not only limiting Germany’s capabilities but also strengthening France by redirecting Germany’s coal production to the French steel industry.Footnote 69

France also sought to form alliances able to neutralise a potential German threat. In December 1944, de Gaulle and Bidault negotiated in Moscow a ‘rear alliance’ with the USSR, committing both states to jointly oppose ‘any initiative that might make it possible for [Germany] to attempt aggression again’.Footnote 70 This preventive dimension was demanded by the French.Footnote 71 The French–British alliance signed by Bidault in March 1947 also committed the parties to jointly oppose any threat arising from German actions and provide each other with military support in the event of not only a German attack but also a preventive war against Germany.Footnote 72

The crisis of limitation and neutralisation

The rise of the Cold War encouraged the United States to restore Germany’s power instead of weakening it to better resist Soviet influence, which made limitation increasingly impossible to achieve and neutralisation increasingly unreliable.

In January 1947, the Americans and the British decided to fuse their occupation zones and delegated some powers to German representatives. In January 1948, bizonal institutions were reorganised with a two-chamber parliament, an executive and a high court of justice.Footnote 73 These were the first steps towards the restoration of a German central government above Länder, and France was faced with a ‘fait accompli’: ‘Weak and without a lot of resources, we are witnessing the erosion of our positions.’Footnote 74 In November 1948, France was once again faced with a fait accompli. American–British authorities decided to leave it to the future German government to settle the question of the ownership of the Ruhr’s mines and steel industries, which went against French support for international property.Footnote 75 The Americans were increasingly hostile to factory dismantling for reparations and announced an increase in steel production aimed at a rapid return to pre-war levels.Footnote 76 Overall, France’s position in Germany had ‘collapsed’.Footnote 77

Moreover, in a context marked by the US and British occupation of most of West Germany, a preventive war with the aim to impose France’s limitation objectives, comparable to the 1923 invasion of the Ruhr, was unrealistic. The ‘determinants of war and peace’ were now in the hands of the two superpowers.Footnote 78 As noted by French diplomats, both the USSR and the United States were seeking to ‘use [Germany] for its own benefit’; as a consequence, ‘The Franco-German duel is historically outdated and can only occur as a secondary phase of a larger conflict’.Footnote 79

Another balancing strategy remained, namely, neutralisation. However, France’s balancing alliances were not strong guarantees against a revitalised Germany. The French–Soviet alliance soon became an empty shell, as the Soviets refused to support France’s policy vis-à-vis Germany.Footnote 80 Similarly, the French–British alliance was hindered by the two partners’ deep divergences over the future of Germany.Footnote 81 In 1948, the French were also looking for guarantees from the United States against any violation by Germany of its security obligations.Footnote 82 However, as the United States was increasingly seeking to empower Germany, the risk was that ‘Germany will be the US’ main pawn on the European chessboard’.Footnote 83

To neutralise Germany’s growing economic power, France finally relied on the new International Authority for the Ruhr (IAR). France obtained the creation of the IAR at a conference on the future of West Germany organised in early 1948 in London among Western allies and the Benelux countries. The compromise reached in London provided that the IAR would control the distribution of the Ruhr’s coal, coke, and steel between German consumption and export but not its production management, as demanded by the French.Footnote 84 The IAR would have the power to impose sanctions on Germany if it failed to comply with IAR decisions. The main problem was that the IAR was dependent on other inter-Allied agencies, particularly the coal and steel boards, which had important but only temporary management powers.Footnote 85 The risk was that, eventually, the IAR would prove to be powerless. The French thus demanded that the powers of the coal and steel boards should be transferred to the IAR and rendered permanent, but this solution was rejected by the Americans.Footnote 86

Integration as a response to cross-temporal interdependence

In the late 1940s, France still had the power to neutralise Germany through the IAR, but this power was temporary. The French anticipated that Germany might become dominant in the future, at which point France would no longer be able to limit or neutralise German power. This cross-temporal power relationship could not be resolved by the traditional balancing strategy.

In 1948, French diplomats in charge of the German question first observed that ‘it is no longer possible to prevent the restoration of Germany’.Footnote 87 Since France was unable to match the pace of German economic recovery, West Germany could ‘become economically stronger than us in a few years’.Footnote 88 This was an acknowledgement that limitation was a no longer viable strategy. Second, drawing on the experience of the inter-war period, the French feared that control mechanisms would prove unreliable; they also doubted that the United States and the UK would be willing to exercise these controls firmly.Footnote 89 This was the anticipation of the fact that the neutralisation of German power would soon no longer be a credible option.

As a consequence, the Directorate of Europe argued that

We have a real chance of being assured of knowing what is going on in Germany or of exercising serious control over it only to the extent that the Germans themselves will accept or be involved in such controls.Footnote 90

The note proposed a ‘European steel pool in which Germans and French would sit on an equal footing’, which ‘implies that we are prepared to sacrifice some of our sovereignty’.

The key advantage of integration was that, through reciprocal sovereignty transfers, it made possible an intertemporal transaction between the Germans’ present dependence on occupying powers and the French’s future dependence on restored German power. Since they anticipated that the Germans would sooner or later recover equal economic rights, with US and UK support, French diplomats recommended making immediate concessions in exchange for an agreement on a European framework that would ‘set now a distribution of power that is stable, consistent with our security and economically justifiable’.Footnote 91 ‘Anticipating, to control it, on a fatal development, we would enclose the inevitable German recovery in the framework of a European agreement.’Footnote 92 Through integration, the French would renounce their discriminatory control over Germany in the short term in exchange for longer-term guarantees on future German economic power. The cross-temporal nature of the interdependence at stake also meant that the French could not afford to wait too long. ‘We are still the strongest […] By waiting longer, we risk seeing the balance of forces shift to our disadvantage.’Footnote 93

The unreliability of balancing and the emergence of the ECSC

The eventual launch of the ‘Schuman plan’ was not so much the outcome of an ideological choice than that of a systemic selection. Foreign Minister Schuman (1948–53) explored several different options; most of them simply did not work. It was the failure of the logic of long-term neutralisation through the IAR that prompted him to turn to integration.

The first option was to rely on the IAR, the only permanent control mechanism over West Germany that the French had managed to achieve. However, in 1950, the French administration observed that the IAR was ‘going through a very serious crisis’ and was weakened by ‘forced inaction’ because of its lack of effective power and US scepticism towards its missions.Footnote 94 Because of Americans’ growing reluctance to impose discriminatory control over West Germany, the French representative of the Coal Board estimated that it was very unlikely that the IAR would be granted permanent powers over the management of the Ruhr unless this control were also exercised over the French industrial region of Lorraine.Footnote 95 In other words, France also had to agree to surrender part of its sovereignty.

The second option was to rely on French–British-led integration. In 1948, France proposed to the UK and Benelux countries the establishment of a European Assembly designated by national parliaments.Footnote 96 Although this assembly was supposed to have initially only consultative powers, its role was to prepare the creation of a ‘European Union’ that would provide a framework for the integration of Germany:

If we want to prevent Germany from returning to the course of an independent policy, which would be ultimately detrimental to the security of the continent, it must be strongly linked to the emerging group.Footnote 97

However, the French proposal clashed with the British government’s preference for an intergovernmental organisation.Footnote 98 For the French, the problem was that Germany would not be constrained by ‘a series of conferences among Prime Ministers’: ‘such a loose formation will break at the first serious difficulty’. The French could not accept Germany’s recovery ‘if its integration into Western Europe is not ensured by procedures such that progress made on the road to a federation is irreversible’.Footnote 99 A compromise was found, and a ‘Council of Europe’ was established in May 1949, with a Committee of Ministers deciding by unanimity and a Consultative Assembly. However, all subsequent attempts by the Assembly to launch integration initiatives were blocked by the Committee of Ministers, particularly the British government.Footnote 100 In April 1950, the Directorate of Europe, fearing that West Germany would soon recover its full independence with US and UK support, still hoped that

The Council of Europe, modifying its present physiognomy, would group together members that have renounced in its favour certain attributes of their sovereignty and would have a certain degree of supranational authority imposing decisions on the states of Western Europe.Footnote 101

However, there was no reason to believe that the UK would allow such an evolution.Footnote 102

The obstacles to the strengthening of the IAR and the Council of Europe explain why, in May 1950, Schuman welcomed Planning Commissioner Jean Monnet’s plan for the pooling of French and German coal and steel production under a supranational High Authority. According to the Directorate of Economic Affairs, this new initiative could be explained by the fact that France’s policy conducted thus far vis-à-vis Germany had ‘largely failed’.Footnote 103 As Schuman put it, ‘In the spring of 1950, we had the feeling that we were at a standstill in dead ends’.Footnote 104

However, even in May 1950, Schuman still pursued several options at the same time. On 3 May, at a meeting of the French Council of Ministers, he presented a strategy involving West Germany’s accession to the Council of Europe, the strengthening of the IAR, and the new project of the High Authority.Footnote 105 A few days later, Schuman reported that no agreement had been reached with the United States and the UK on the powers of the IAR and concluded that ‘it would be a dangerous illusion to rely on unilateral control, all the more reason to maintain our plan’.Footnote 106

The Schuman plan turned out to be more viable internationally than alternative options to establish strong control mechanisms over West Germany’s future economic power. Because it offered immediate equality of rights to West Germany, it was enthusiastically endorsed by Chancellor Adenauer,Footnote 107 which opened the possibility of providing the High Authority with more effective powers than those of the IAR. In exchange, France accepted the dissolution of the IAR when the ECSC treaty took force.Footnote 108 For the same reason, the Schuman plan was also more acceptable for Americans, who were hostile to punitive measures but supportive of European integration.Footnote 109 According to the National Assembly’s Foreign Affairs Committee’s rapporteur Alfred Coste-Floret, the Schuman plan was preferable to the IAR, which had more limited powers and ‘was not eternal’.Footnote 110 Integration was a response to the expected power shift in West Germany’s favour:

Germany is in full development […] and it is precisely when we could conceivably be worried about this evolution that the Schuman plan timely intervenes to stabilize the situation and to remove from the German national state, just as it removes from the French national state, the disposition of its heavy industry for war purposes.Footnote 111

If the High Authority provided guarantees vis-à-vis West Germany, it also constrained France’s autonomy. Because the UK was France’s traditional ally against Germany and because the British were unwilling to embrace the principle of supranational powers,Footnote 112 French–German integration partially cut France from a potential source of support in its relationship with West Germany. As noted by French diplomats, ‘Perhaps for the first time since the beginning of the century, we are going to witness, in Paris, the development of international negotiations of considerable importance, in which Germany will take part alongside France, without England being involved’.Footnote 113 However, French–British cooperation within the IAR or the Council of Europe had proven incapable of providing strong guarantees against future West German economic power, and the shift in France’s German policy from balancing to integrating implied that the preservation of the supranational character of the initiative was regarded as more valuable than the inclusion of the UK. In addition, the French did not expect West Germany to be able to dominate the ECSC: UK participation ‘is not indispensable today, given the respective strengths of the partners involved, but it may become so tomorrow’.Footnote 114 The ECSC treaty was signed on 18 April 1951.

Extending integration to the military area

North Korea’s invasion of South Korea on 25 June 1950 led to a new crisis of France’s balancing strategy by raising the question of West Germany’s rearmament. Until then, Germany’s disarmament had remained a central aspect of France’s balancing strategy. On 24 November 1949, Schuman declared to the National Assembly that the government ‘considered the reconstruction of a German military force to be out of the question’.Footnote 115

Because the offensive had likely been approved by Moscow, Western leaders feared that it was the prelude to a Soviet offensive in Europe.Footnote 116 On 12 September 1950, Secretary of State Dean Acheson declared that the United States was willing to send ‘substantial forces’ to Europe only if its European allies were prepared to make an effort and to accept German rearmament within NATO.Footnote 117 The French were firmly opposed to this prospect but found themselves isolated and under pressure.

This situation led the French government to adopt Monnet’s new idea of an integrated European army as an alternative to an autonomous West German army. Indeed, the US determination to rearm the Germans severely weakened any limitation strategy. On 14 October 1950, Monnet wrote the following to the President of the Council, René Pleven:

If we let things go, sooner or later, we shall have to accept a compromise solution (priority granted to France, but a German army of small units) that will only be an illusion. The German army will be reconstituted through the back door. Our resistance will have been for nothing.Footnote 118

French decision-makers were also sceptical towards the neutralisation of future West German military power because they feared that control mechanisms would not hold and that France’s relative position vis-à-vis West Germany would decline. As Monnet put it,

If German rearmament is accepted – whatever the forms and precautions (limitations, delays, controls) by which this acceptance is to be mitigated – Germany, through its direct relationship with the US and its regained power, will have acquired considerable prestige and political room for manoeuvre: in the short term, it will take a position on the continent that France, through the Schuman plan, could have claimed.Footnote 119

As an alternative, the Pleven plan proposed the creation of a European army, which would accomplish ‘a complete merger of human and material elements’ under ‘a single political and military European authority’.Footnote 120 Similar to the Schuman plan, the European army plan, by locking West Germany’s commitment, sought to make possible an intertemporal transaction in which France abandoned its present power to discriminate against West Germany in exchange for the ability to maintain some control over West Germany in the future. For the French negotiator, the main advantage of the EDC treaty signed on 27 May 1952 by the six ECSC members was that, within a European army, ‘Germany cannot autonomously dispose of forces in Europe for the accomplishment of its own purposes’.Footnote 121 For Schuman, any attempt to recreate an autonomous German army would thus be ‘difficult’ and ‘quickly defeated’.Footnote 122 In exchange, the EDC treaty banned any discriminatory measure against West Germany.

The dilemma of competing dependencies

It remained to be seen whether integration would not turn out to be too costly an option by reducing France’s ability to address other important sources of dependence.Footnote 123 As French diplomats put it,

For us, European unity is not a mystique but a policy. […] This policy has both a condition and a limit, namely, the maintenance of France’s global positions. This raises both the problem of Indochina and the problem of North Africa.Footnote 124

Indeed, since 1946, France had been engaged in a colonial war in Indochina. Beginning in 1951, more than 120,000 soldiers were engaged in Indochina.Footnote 125 Moreover, in 1952, another colonial conflict broke out: the uprising of France’s protectorates in North Africa. Although 16,000 soldiers were already in Tunisia, two infantry divisions were sent as reinforcements in 1954; in Morocco, the number of French soldiers rose from 45,000 in 1952 to 100,000 in 1956.Footnote 126

France’s overseas vulnerabilities directly affected its ability to participate in the EDC. On 23 August 1951, the Joint Chiefs of Staff outlined the points on which they urged the government to be firm in negotiating the EDC treaty. First, France would need to keep some forces under national command to secure its presence in Indochina and North Africa. Second, France needed to be able to assign more forces than West Germany to the European army to ensure that the EDC Commander-in-Chief would be French.Footnote 127 Indeed, a European army under German leadership would have precipitated West Germany’s pre-eminence instead of preventing it. These simultaneous requirements conflicted with each other, as troops had to be assigned to either the EDC or the defence of the colonies. After the EDC treaty was signed, the problem was aggravated by the worsening situation in Indochina. The government was led to reduce its forecast for French forces that would be integrated into the EDC. German land forces were expected to outnumber the French contingent by 115,000 soldiers in 1954.Footnote 128 The Joint Chiefs of Staff planned to integrate into the EDC French forces in North Africa; however, from 1952 to 1953, riots in Tunisia and Morocco necessitated the deployment of additional troops from Europe instead, thus widening the potential gap between the French and West German forces in Europe.Footnote 129

First, the EDC restricted France’s military flexibility and its ability to use its forces overseas. The French government sought to address this problem and managed to have its five European partners sign, on 24 March 1953, interpretative protocols that facilitated, under certain conditions, the withdrawal of some forces from the European army to address an overseas crisis. However, for General Billotte, who was a member of the National Assembly, the EDC would lead to the loss of French officers’ ‘multitask training’ and of the ‘the incomparable experience provided to our army by alternative service in the metropolitan territory and overseas’.Footnote 130 As a consequence, French soldiers trained and equipped by the European army would be ill suited for overseas missions. According to Billotte, preserving French forces’ flexibility was ‘also the means by which France will be able to contribute indigenous troops to the defence of Europe. In the face of Germany, France must be able to preserve this advantage.’Footnote 131

At a secondary level, the EDC also induced a loss of flexibility in terms of the support that France could mobilise against West Germany. Because the EDC voting procedure depended on member states’ contributions to the European army but did not take into account overseas missions, General Billotte estimated that West Germany would have 33.6 per cent of the votes and France only 24.8 per cent: ‘Being almost master of the Community’, with a blocking minority on certain decisions, West Germany would certainly ‘use this advantage at the Atlantic and global levels’.Footnote 132 Whereas within the NATO framework, France would be able to rely on US and UK support to balance German influence, France could become more isolated ‘in the face of a Germany that in the European army system would become dominant’.Footnote 133 Similarly, for Gaullist representative Philippe Barrès, accepting the EDC was to say: ‘Let us distance ourselves from our Anglo-Saxon allies, let us cut ourselves off from the French Union [the French colonial empire].’Footnote 134 Integration was a source of weakness because ‘Germany dominates only within an integrated Europe where national cells are broken up and external help is impossible’.Footnote 135 The exclusive nature of integration hindered France’s ability to rely on the military power of its overseas territories and its American and British allies and thus weakened its position vis-à-vis West Germany.

The cost of losing flexibility and the failure of the EDC

The tension between European and overseas commitments and the lack of flexibility within an integrated army were at the heart of the opponents’ arguments. General Juin, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, initially supported the European army option ‘because it is essential to immediately strengthen the defence of Western Europe and because a negative position would have led to the reconstitution of the German army, with the complicity of the US’.Footnote 136 However, a key condition for Juin was that ‘the French contingents should be larger than the German contingents’.Footnote 137 When it became clear that this condition could not be met, Juin publicly criticised the EDC on 3 January 1953:

With the events already happening in Indochina and those beginning to happen in North Africa, we would be in an impossible situation, and the Germans would soon constitute the overwhelming majority of the Community, which was not what was originally planned.Footnote 138

During the National Assembly’s ratification debates in August 1954, the Defence Committee’s rapporteur, Gaullist Raymond Triboulet, argued that France’s ability to keep some forces under national command for overseas missions would be constrained by the EDC treaty, which was bad for not only France but also the defence of Europe. As WWII had shown, ‘Who could defend Europe without Africa?’Footnote 139 Triboulet concluded,

We are told, ‘Equip fourteen divisions for the EDC; afterward, take care of Africa and overseas territories, if you still have resources and men left.’ Here comes fully to light what is unacceptable for France in the EDC. […] Because the EDC would ruin the defence of the French Union and, thereby, the defence of Europe, your National Defence Committee asks you to reject it.Footnote 140

On 30 August, the Assembly rejected the EDC. The French government immediately sought a replacement solution that was less integrated and thus less constraining for French forces. At the London conference (28 September to 3 October 1954), the French President of the Council Pierre Mendès France reluctantly agreed that West Germany should join NATO, which corresponded to the initial American plan of 1950. However, Mendès France sought to prevent the risk of unlimited West German rearmament through another framework, namely, the 1948 Brussels Pact between France, the UK, and the Benelux countries, joined by West Germany and Italy.Footnote 141 With the establishment of the Western European Union (WEU) on 23 October 1954, France returned to a balancing logic that relied first on an armament control mechanism (limitation) and second on the UK’s commitment to maintain troops on the continent to ensure that France and its allies could constrain West Germany in case of difficulties (neutralisation).

Compared with the defunct European army project, NATO entailed a lower level of military integration. This meant more autonomy for West German national authorities, particularly regarding the financing, recruitment, administration, and equipment of their troops, as well as the selection, training, and advancement of their officers, which many pro-EDC representatives saw as a potential source of insecurity.Footnote 142 However, it also meant more autonomy for France, and, as pointed out by Mendès France, this solution avoided the constraints imposed by the EDC regarding French overseas territories.Footnote 143 For the pro-EDC representative Pierre-Henri Teitgen, this was a return to ‘the old, very old system of balances and alliances’.Footnote 144

Power–dependence relations in the current global power competition

Although France’s post-war policy offers a particularly clear case of decision-makers arbitrating between balancing and integration strategies, the structure of power–dependence relations can also illuminate more recent cases of power competition in which supranational integration is not necessarily at stake.

For example, in the context of the current global geoeconomic competition, some states aim to reduce their vulnerability to Chinese economic coercion through measures such as foreign investment screening,Footnote 145 trade diversification, or friend-shoring.Footnote 146 This corresponds to the logic of limitation, through which states aim to reduce China’s economic power over them. Theoretically, this approach is the most directly effective protection against external coercion. However, just as France’s post-war policy of limiting West Germany’s economy quickly became impossible once the United States stopped supporting it, a full economic decoupling from China would be very costly or even impossible in today’s global economy.Footnote 147 An alternative approach can be used to ‘neutralize the Xi regime’s coercive behavior without decoupling’,Footnote 148 by mobilising China’s own economic dependence on other states. Following this neutralisation logic, states do not attempt to eliminate China’s ability to harm them but rather seek to use ‘the threat of punishment with trade retaliation to impose significant and unacceptable costs on China’ and thus ‘shape and deter Beijing’s predatory behavior’.Footnote 149 However, just as France’s strategy of neutralising post-war West Germany’s economic power faced a credibility problem in the context of the power shift between the two countries, a current strategy of neutralising China’s economic power would also be ‘only as effective as it is credible’.Footnote 150 Among the potential targets of Chinese coercion, there would be a high incentive to free ride.Footnote 151 In other words, even if there were a symmetry between China’s economic power over others and its economic dependence on others, neutralisation could be challenging or even unreliable. While 1950 France sought to overcome its credibility problem by relying on a supranational organisation, some authors argue that those states seeking to credibly neutralise Chinese coercion should formalise an ‘economic Article 5–type of defense framework’,Footnote 152 or even an ‘economic NATO’.Footnote 153

The logic of competition between dependencies, which led to the failure of the European army project in the 1950s, also has echoes in the current evolution of US military strategy. Just as France faced competing military dependencies between Europe and overseas colonies in the 1950s, the United States has increasingly emphasised that its military commitments in Europe must not come at the expense of its prioritisation of the Chinese challenge in the Pacific.Footnote 154 In the 1950s, French decision-makers feared that the EDC would undermine the French army’s global flexibility; similarly, the Trump administration today sees NATO as a potential hindrance to its military efforts in America and the Pacific.Footnote 155

Overall, the study of power–dependence relations provides a conceptual framework that not only covers both the economic and military spheres in a world where the US–China rivalry plays out in both but also bridges the gap between the issues of credibility and coordination that have been highlighted by liberals and the issues of flexibility and autonomy that have been raised by realists. This is accomplished by showing that these two kinds of concerns stem from particular configurations in terms of limitation, neutralisation, and competition between power and dependence.

Conclusion

I have argued that power–dependence relations are crucial dimensions to analyse for a better understanding of how states navigate between realist and liberal logics, particularly between balancing and integration strategies.

Specifically, I have highlighted three types of relationships between power and dependence: limitation, neutralisation, and competition. Limitation and neutralisation make the balancing strategy viable by allowing power to offset dependence and thus preserve the autonomy of the state. On the other hand, when limitation and neutralisation are no longer workable, particularly in the case of cross-temporal interdependence, the balancing strategy becomes unreliable, which makes states vulnerable to each other. In this case, integration offers an attractive alternative that allows an intertemporal transaction between powers that cannot balance each other directly. In the case of competition between a state’s different sources of dependence, the loss of flexibility brought about by integration may prove dangerous by limiting the state’s ability to address various dependencies simultaneously. The analysis of power–dependence relations thus supports the understanding of why the value of autonomy and centralisation may vary according to the situation and how states arbitrate between the realist logic of balancing and the liberal logic of integration.

Finally, while the analysis of power–dependence relations in terms of limitation, neutralisation, and competition is enlightening for understanding the alternative between balancing and integration, it could also, more generally, provide a useful typology for the study of power competition and facilitate dialogue between international political economy and international security, as well as between the realist and liberal paradigms.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the two anonymous EJIS reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments.

Pierre Haroche is Associate Professor of European and International Politics at the Catholic University of Lille. Previously, he worked at Queen Mary University of London, the French Ministry of the Armed Forces’ Institute for Strategic Research (IRSEM, Paris), and King’s College London.