Introduction

After a very difficult 2017 owing to the wave of fires throughout the country in the summer and autumn, 2018 was quite calm. Prime Minister Antonio Costa's Socialist minority government was able to govern with the continuing support of the two left‐wing parties, Block of the Left/Bloco da Esquerda (BE) and the Portuguese Communist Party/Partido Comunista Português (PCP).

Election report

There were no elections scheduled in 2018.

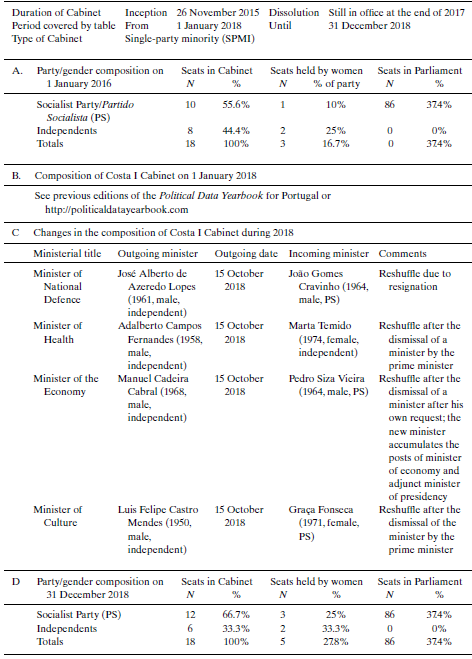

Cabinet report

A major government reshuffle took place on 15 October 2018. This was announced by the prime minister after an 11‐hour marathon meeting of the Council of Ministers in which the final budget draft for 2019 was negotiated and agreed. The respective ministers of health, culture and economy were informed only after the meeting. The catalyst for the change was the resignation of the defence minister, the international law professor José Alberto Azeredo Lopes, after it was found after an investigation that in 2017 weapons from the military base of Tancos were stolen by criminals with the support of army insiders, with many questions remaining unanswered. In this context, Prime Minister Antonio Costa used the occasion also to get rid of the less efficient or controversial ministers, particularly health Minister Adalberto Campos Fernandes, who was held accountable for the ongoing financial mismanagement of the national health service.

The new defence minister became João Gomes Cravinho, who is son of historical eminence grise of the party João Cravinho and who had been a member of the Socrates government as state secretary between 2005 and 2011. Marta Temido, an experienced hospital manager and until then president of the Portuguese Association of Hospital Managers, became the new health minister in the hope of changing the negative headlines of the government. The new minister of culture became Graça Fonseca, who was previously state secretary for administrative modernization and worked in local politics for the Socialist Party. The former Joint Minister Pedro Siza Vieira became the new economy minister. He has been a successful lawyer in the private sector, and had made a name as an arbiter in difficult negotiations between enterprises. However, throughout the year, he became allegedly involved in revolving doors cases, showing some conflicts of interest in his role as head of the economy ministry, and was criticized for it. Moreover, it was found that he had a conflict of interests in his post as minister and being simultaneously executive partner in his law firm. It seems that when he found about it, he desisted being the executive partner at the law firm. In December 2018, the Constitutional Court declared this a minor case of culpability and did not impose any sanctions on the minister.

Parliament report

Approval of the budget 2019

The most important event of 2018 was the approval of the budget for the year 2019 in the autumn. This was the last budget of the Socialist minority government of Antonio Costa before the scheduled general elections in autumn 2019. In this regard, the two left‐wing parties, the BE and the PCP‐BE, tried to obtain more funding for their social policies, particularly for working people with the lowest wages and retired people with small pensions. As in previous years, Finance Minister Centeno was very keen to reduce the budget deficit, so that not a lot of manoeuvring was possible. Moreover, the budget included some tax incentives to reduce the fiscal burden on enterprises. In this context, Centeno was able to present a balanced budget. On 29 December 2018, the budget was approved with the votes of the left‐wing parties PS, BE and PCP‐PEV, as well as the one‐man Party of the Animals and Nature/Partido dos Animais e Natureza (PAN). It was rejected by the right‐centre Social Democratic Party/Partido Social Democrata (PSD) and the Democratic Social Centre‐People's Party/Centro Democrático e Social‐Partido Popular (CDS‐PP).

Revised Law on Public Funding for Political Parties

The early part of the year saw continued controversy over party funding laws. On 21 December 2017, the revised law on public funding for political parties (Lei de Financiamento dos Partidos Politicos e Campanhas Eleitorais) was approved in Parliament. However, President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa vetoed the bill on 3 January 2018 due to major objections. On the one hand, the revised law allowed for political parties to receive value‐added tax (VAT) for all expenses of political parties and, on the other, the cap on private donations per year was removed, which had stood at about €640,000. Moreover, political parties could use public spaces for free. The concerns of the president were taken into account, but only the VAT aspect was reduced to expenses related to the dissemination of political messages (letters or publicity sent to voters), while no limits were set for private donations. Most of the bill was kept as it was previously, and President Rebelo de Sousa decided not to veto the bill again on 24 March 2018. Unfortunately, auditing party finances is several years in arrears. In 2017, several irregularities were found in the reports for 2009, for example, and the Constitutional Court suspended penalties for parties for non‐compliance because of the ongoing revision of the law. Moreover, the Entity for the Accounts and Finances of the political parties (Entidade de Contas e Financiamentos Politicos – ECFP) is under‐resourced to do a proper financial auditing of the political parties.

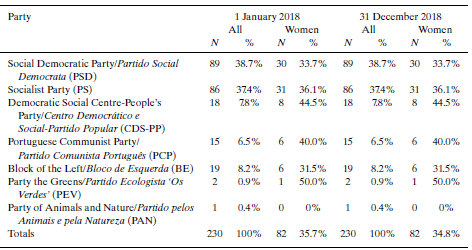

Table 2. Party and gender composition of Parliament (Assembleia da República) in Portugal in 2016

Source: Assembleia da República (2019).

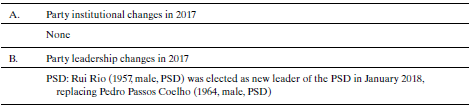

Political party report

After the announcement of Pedro Passos Coelho, President of the PSD, that he would resign from the leadership of the party at the end of 2017, primaries were organized to determine who would be his successor. Two candidates emerged as likely successors, namely the former mayor of Oporto, Rui Rio, and former Prime Minister Pedro Santana Lopes. On 13 January 2018, the results of the primaries became known. The winner was Rui Rio with 22,748 votes (54.1 per cent), while runner‐up Santana Lopes received 19,244 (45.85 per cent). The overall participation rate was 60.34 per cent. On 18 February 2018, Rui Rio was confirmed as the new leader in the 37th party conference.

Throughout the year, Rui Rio focused on developing his policies for the general elections of 2019. Inside the party, there was discomfort that he was too cooperative with Antonio Costa's government. However, he countered that it is necessary first to build credibility among the population.

His runner‐up rival, Pedro Santana Lopes, decided to found a new political party called Alliance/Aliança on 23 October 2018. Ideologically, it is a conservative liberal party to the right of the PSD.

Table 3. Changes in political parties in Portugal in 2018

Issues in national politics

The continuing success of the booming economy

Portugal was one of the bailout countries in which the troika consisting of the European Commission, European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) monitored the implementation of a quite strict package of austerity measures and economic reforms between June 2011 and May 2014. Therefore, the credibility of the minority Socialist government depended on its success to keep on the path of economic reform and control the budget deficit as well as public debt. Finance Minister Mário Centeno was able to use the growth of the Portuguese economy to reduce considerably the budget deficit for a third year in a row. The year 2018 was the first in which Portugal was no longer under the Excessive Budget Procedure (EDP). In 2017, the Portuguese government ended with a –3 per cent budget deficit owing to the financial support to the main Portuguese state bank Caixa Geral de Depósitos, However, according to estimations by the Budgetary Office of the Parliament, in 2018 Centeno managed to reduce the budget deficit to 0.4 per cent. One of the main reasons for the deficit seemed to be the €792 million that the government had to contribute to the banking resolution fund, which was destined to go to Novo Banco (New Bank), which was still making losses that year. This was quite controversial, because in 2017 the US investment fund Lone Star had bought Novo Banco under very good conditions, but tax payers were still underwriting its losses and this could last for several more years. The control of the budget deficit was only possible with a very disciplined budgetary policy imposed by Centeno. It meant that a lot of programmed spending was retained or delayed, leading to financial bottlenecks or even crisis in certain sectors, such as the national health service, in which the level of debt had increased considerably, and payments to external providers was extremely late. This led to the dismissal of the health minister, Adalberto Campos Fernandes, on 15 October 2018, and his replacement by Marta Temido, a professional health administrator, as noted above. Moreover, the Portuguese government relied extremely on the European Union Structural and Investment Funds, which required just 15 per cent co‐funding from the public and private sectors. Therefore, Centeno reduced national public investment levels in order to reduce the deficit. A major problem remained the high levels of public debt, which were slightly down from 124.8 per cent in 2017 to an estimated 121.5 per cent in 2018. A major achievement was the advance payment of the last tranche owed to the IMF share of the bailout in December.

In 2018, it is estimated that the Portuguese economy grew by 2.6 per cent. Unemployment decreased from 9.6 per cent to 7.6 per cent. One major problem remained: a deteriorating or stagnating trade balance. Imports of goods increased more rapidly than exports, so that the coverage level was reduced to 77.1 per cent, 2 percentage points less than in the previous years, and the worst balance since 2011. However, the booming tourism and services industry helped to balance out the deteriorating trade in goods situation.

Rising contestation of civil servants

Since 2007, civil servants had their wages cut or frozen. Although the Socialist minority government started a process of repaying the lost income of civil servants, teachers’ trade unions also wanted the payment of lost progression pay for a period of over nine years. Finance Minister Centeno was very keen to keep payments to an absolute minimum in order to achieve the budget deficit target. However, the left‐wing parties BE and PCP‐PEV supporting the minority government wanted the demands of the trade unions to be included in the 2019 budget. In spite of several negotiation rounds with the teachers’ unions, an agreement was not achieved until the end of the year. There was the danger that any concessions to the teachers’ trade unions would generate similar demands among other groups in the large civil service, such as the police and the health sector.

Cooperation between the two main parties in core issues of national importance

The new president of the PSD, Rui Rio, was very keen to cooperate closely with the government in policies of strategic national importance. Such cooperation materialized in working towards securing the same levels of funding from EU Investment and Structural Funds for the period 2021–27, and establishing a commission on decentralization consisting of experts in the matter.

Although the PSD was critical of the reallocation of the EU structural and investment funds to the region of Lisbon, and away from other regions, it supported the government in securing the same amount of funding for the next period, 2021–27. There was a general concern among the two political parties that Portugal had to accept a 7 per cent reduction of EU Structural and Investment Funds in the next period. Moreover, the European Commission wanted to reduce the participation of the EU funds from 85 per cent to 70 per cent, with the rest then having to be funded by the national government and the private sector. This was regarded as something to avoid because of the implications for the already quite fragile budgetary process.

The two parties agreed to establish an independent commission for the decentralization chaired by eminence grise Socialist João Cravinho, father of the defence minister, which started in October 2018. The commission selected a number of well‐known scholars to draft a plan for decentralization. According to different declarations in the press, the tendency was to propose a regionalization of the country as enshrined in the constitution, but never implemented. Such a regionalization attempt failed after a previous negative referendum on 8 November 1998.

Socioeconomic agreement between social partners

On 18 June 2018, a major tripartite socioeconomic agreement was signed in order to reform the labour market and introduce measures to reduce the level of precarious work. Moreover, employment incentives were agreed in order to transform fixed‐term contracts into permanent ones. The agreement was signed by the major employers’ confederations and the General Union of Workers (UGT); however, the Communist‐dominated General Confederation of Portuguese Workers (CGTP‐In) was against it and did not sign it (Comissão Permanente de Concertação Social (CPCS) 2018).

The labour market agreement had to be approved by Parliament, which led to the introduction of changes proposed by MPs of the Socialist Party, BE and Communists. It was approved in a first reading by the PS, BE and Communists, and abstained by the PSD, CDS and PAN in July 2018. The main employers, the Confederation CIP, already announced that the deal would not be any longer valid if changes were undertaken to the agreement. The bill was still awaiting approval at the end of the year.

The government is high in the opinion polls

New PSD leader Rui Rio was not able to change the dominant position of the Socialists in the opinion polls. On the contrary, the share of the vote of the PSD has been declining. One of the main reasons was that he had to deal with the formation of a new party, Alliance, founded by his former rival the charismatic Pedro Santana Lopes. According to the opinion polls of late November, the PS would get 40 per cent, the PSD 24.8 per cent, the BE 7.6 per cent, the CDS 7.1 per cent, the CDU 7.1 per cent, the Alliance 4 per cent, the PAN 1.4 per cent and the other 7.5 per cent. Political parties were making preparations for the forthcoming European Parliament election in May and the General election in October 2019.