The apparent dilemma between nuclear deterrence and disarmament is as old as nuclear weapons themselves. On the one hand, deterrence proponents contend that secure second-strike capabilities prevent systemic great-power wars and thus have saved countless lives (Betts Reference Betts1987; Jervis Reference Jervis1989). On the other hand, disarmament advocates warn that deterrence breakdowns risk millions of casualties and even civilizational collapse (Deudney Reference Deudney2007; Fihn Reference Fihn2015; Pelopidas Reference Pelopidas2017; Toon, Robock, and Turco Reference Toon, Robock and Turco2008). This divide has become a defining feature of the atomic age.

That deterrence and disarmament are generally seen as mutually exclusive has come to dominate scholarly debates. This is unsurprising at first glance. Security through nuclear targeting and security through a world without nuclear weapons may seem highly incongruous. Differences between deterrence and disarmament approaches to nuclear weapons may heighten perceptions of incompatibility. Old and new academic literature on deterrence emphasizes nuanced strategic logic (Kroenig Reference Kroenig2018; Schelling Reference Schelling1966), while scholarship on disarmament tends to focus on morality, norms, and activism (Albin Reference Albin2001; Alexis-Martin Reference Alexis-Martin and Woodward2019; Ritchie Reference Ritchie2022). Likewise, deterrence has largely become identified with the realist school of international relations and disarmament with the constructivist school (Martin Reference Martin2013).

However, a small group of scholars have increasingly highlighted ways in which nuclear deterrence and disarmament may not truly be incompatible. They have proposed novel interpretations about how rational and moral thinking can inform both deterrence and disarmament (Fuhrmann Reference Fuhrmann2024; Nye Reference Nye2023). They have also identified commonalities between these policies, viewing them as compatible approaches under certain conditions, such as nuclear rearmament serving as a deterrent in a disarmed world (Schell Reference Schell2007). Accordingly, recent literature highlights the strategic value of “nuclear latency,” “virtual nuclear deterrence,” and “weaponless deterrence” (Fuhrmann Reference Fuhrmann2024; Fuhrmann and Tkach Reference Fuhrmann and Tkach2015; Mehta and Whitlark Reference Mehta and Whitlark2017; Volpe Reference Volpe2023). While this scholarship provides an important corrective, it tends to overlook a crucial actor in nuclear politics: individuals. We therefore build on scholarship that articulates the above policy linkages to explore whether the public—whose views are subject to robust study in the nuclear domain—views deterrence and disarmament as dichotomous or, instead, as mutually compatible.

As with the public, the thinking of national leaders rarely fits squarely into the deterrence-disarmament dichotomy. US presidents from Ronald Reagan to Barack Obama exhibited a distaste for nuclear weapons while remaining committed to the deterrence mission. Donald Trump even explained that Washington “must greatly strengthen and expand its nuclear capability until such time as the world comes to its senses regarding nukes” (quoted in Morello Reference Morello2016). Trump’s 2018 Nuclear Posture Review likewise retained Obama’s objective of eventual nuclear disarmament.

This duality is not unique to the Global North or to leaders of nuclear-armed states. For instance, Egypt’s inability to obtain nuclear weapons to counter Israel led President Gamal Abdel Nasser to instead forswear the bomb. Nasser instrumentally used the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) to stigmatize Jerusalem (Solingen Reference Solingen2007; Walsh Reference Walsh2001). The above examples show that those who initially support policies of deterrence or disarmament may, ironically, come to embrace the other option in pursuit of their goals.

Recent survey-based literature investigating public views likewise suggests that there may be more than meets the eye to the deterrence-disarmament binary. Several experimental studies have indicated that shockingly high proportions of Western democratic publics may support the retaliatory strikes underpinning nuclear deterrence—breaching the “nuclear taboo” (Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Eguchi, Nakagawa, Shibata and Tago2023; Dill, Sagan, and Valentino Reference Dill, Sagan and Valentino2022; Press, Sagan, and Valentino Reference Press, Sagan and Valentino2013; Sagan and Valentino Reference Sagan and Valentino2017). However, other experimental and observational surveys illustrate that these very same publics back nuclear abolition and want their governments to ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) (Baron, Gibbons, and Herzog Reference Baron, Gibbons and Herzog2020; Egeland and Pelopidas Reference Egeland and Pelopidas2021; Herzog, Baron, and Gibbons Reference Herzog, Baron and Gibbons2022). Meanwhile, a paucity of opinion studies in the Global South and nondemocratic countries makes it difficult to determine the breadth of this phenomenon.

This myopic view has consequences for scholarship. International relations studies tend to homogenize the Global South’s nuclear preferences. The literature does so by overwhelmingly focusing on the moral arguments these states advance during multilateral negotiations (Verschuren Reference Verschuren, Gruszczak and Kaempf2023). Authors use historical evidence or statements of current leaders and their administrations to trace national preferences, with very little work exploring public opinion (Biswas Reference Biswas2014; Coe and Vaynman Reference Coe and Vaynman2015; Mpofu-Walsh Reference Mpofu-Walsh2022; Rodriguez and Mendenhall Reference Rodriguez and Mendenhall2022; Walker Reference Walker2000). For example, the participation of most Global South states in nuclear-weapon-free zones is seen as evidence of their backing for disarmament (Mpofu-Walsh Reference Mpofu-Walsh2020). This stands in contrast to common notions of a strategic focus among the Global North prioritizing nuclear deterrence (Fuhrmann Reference Fuhrmann2018; Kroenig Reference Kroenig2018). Hence the literature often lacks lenses to capture within-region and cross-country variation and the domestic preferences that inform, enable, and constrain states’ nuclear policies.

In this reflection essay, we thus ask: Do publics worldwide exhibit nuclear attitudes neatly reflecting beliefs favoring either deterrence or disarmament? How can there somehow be simultaneous approval of both using and banning the world’s most powerful weapons? And how do these preferences vary across geographies? These answers matter, as the literature has demonstrated that political and military leaders are responsive to public opinion about the use of force, even including nuclear strikes (Chu and Recchia Reference Chu and Recchia2022; Lin-Greenberg Reference Lin-Greenberg2021; Smetana et al. Reference Smetana, Sukin, Herzog and Vranka2025). Yet scholars and policy makers still lack a comprehensive map of global public opinion toward nuclear policies.

In pursuing these questions, we aim to provide considerable new data to the research community with a global study of public attitudes toward the bomb. We designed a large-scale observational survey to provide insights into real-world nuclear choices facing publics (Rosenbaum Reference Rosenbaum2020). Our dataset offers a greater breadth of national data than existing studies of nuclear attitudes. We include states from the Global North and the Global South, democracies and autocracies, and numerous publics that have rarely—if ever—been surveyed by academics about nuclear issues. By making available these data and systematically assessing patterns in worldviews, this study makes valuable contributions to the nuclear politics literature. It provides checks on existing scholarship on nuclear preferences, offering a means to assess the generalizability of phenomena typically studied in a small number of states, and usually one at a time.

Beyond our data contribution, we find compelling evidence that publics do not rigorously adhere to the deterrence-disarmament binary characterizing much scholarship and policy discourse. We find broad public support for both nuclear deterrence and disarmament. This carries policy implications. The malleability of public opinion could allow policy entrepreneurs to capitalize on entangled public views to advance either an agenda of deterrence or disarmament.

This reflection essay proceeds as follows. First, we summarize the relevant literature, highlighting how oversimplifying public views has led to misperceptions of a categorical divide between deterrence and disarmament. Next, we lay out several potential mechanisms through which deterrence and disarmament thinking may coexist among individuals. In the third section, we describe the methodology of our cross-national survey and introduce our dataset. We then discuss our initial findings: our novel dataset provides clear evidence of complex nuclear thinking among global publics. Across the world, we find that individuals commonly back both deterrence and disarmament as viable options for reducing nuclear dangers. The empirical evidence from our dataset challenges the deterrence-disarmament binary and offers valuable context for understanding global nuclear views. Finally, we conclude with directions for future research about perceptions of the bomb, including studies that may draw directly on our data contribution.

Dichotomies in International Nuclear Politics

In a seminal study, Sagan and Valentino (Reference Sagan and Valentino2017, 58) surveyed the willingness of Americans to support using nuclear weapons in conflict. Their results were startling: nearly 60% of the US public would back nuclear strikes on Iran—killing two million people—to save the lives of 20,000 US soldiers. Yet other analyses have found the US public to be far more dovish. For example, Herzog, Baron, and Gibbons (Reference Herzog, Baron and Gibbons2022, 592) found that 65% of Americans wanted to eliminate nuclear arms through the TPNW. These are representative examples of a broader literature, but a close reading of nuclear survey research continuously reveals results that appear inexplicable, if not paradoxical. How could the same population support strikes killing millions using the very weapons that they seek to abolish?

A bifurcation in the literature makes these positions seem incompatible. Namely, two very different camps have emerged to explain state preferences. Some scholars contrast a strategic logic driving nuclear deterrence with a moral logic behind nuclear disarmament. Gibbons and Lieber (Reference Gibbons and Lieber2019, 33–34), for instance, argue that rational cost–benefit assessments drive strategic logic, while ethical revulsion and rectitude guide moral logic. After all, it seems difficult to reconcile calculated nuclear targeting—including of population centers—for deterrence with the humanitarian rhetoric of disarmament. In recent years, however, a small group of scholars have critiqued such dichotomous portrayals of deterrence and disarmament. They have done so by advancing strategic explanations for disarmament, proposing moral accounts for deterrence, and even suggesting that deterrence may be possible for non-nuclear-armed states via nuclear latency (Fuhrmann Reference Fuhrmann2024; Nye Reference Nye2023; Schell Reference Schell2007; Weiner Reference Weiner2023). They have accordingly identified potential commonalities between deterrence and disarmament, raising questions about whether this dichotomy is necessary or accurate.

This minority of scholars points to what is missing from many analyses of nuclear policies and preferences: there are major points of convergence between deterrence and disarmament. Although they employ different tools, deterrence and disarmament are both intended to provide protection to states and societies by reducing nuclear dangers. While several important works have highlighted congruities between deterrence and disarmament, the dominant scholarly and policy approach nevertheless continues to view them in opposition to one another, often pitting competing strategic logics for deterrence against moral logics for disarmament.

Nuclear deterrence theorists argue that state preferences reflect rational self-interest. The entire process of decision making—from proliferation to nuclear weapon use—is said to be subject to cost–benefit analyses. The thinking follows that acquiring a nuclear arsenal is a strategic decision taken when a state faces a serious security threat (Debs and Monteiro Reference Debs and Monteiro2017). Likewise, nuclear postures are responses to adversarial capabilities and may not be constrained by legal or moral considerations. Since deterrence is premised on making potential aggressors fear high retributive costs, nuclear-armed states may adopt postures explicitly violating such guidelines (Schelling Reference Schelling1966, 2–4). Existing deterrence scholarship even suggests that restraint may not necessarily result from legal obligations or moral imperatives to reduce civilian casualties. Instead, strategic fears of setting harmful precedents may inspire nuclear nonuse (Gaddis Reference Gaddis1987; Sagan Reference Sagan, Hashmi and Lee2004).

Studies focusing on disarmament have argued otherwise, pointing to beliefs that nuclear arms are immoral because of their indiscriminate effects on human lives, bodies, and the environment (Potter Reference Potter2017). The resultant, often US-centric, argument is that strong public and elite attitudes on the immorality of nuclear weapons have gradually emerged (Tannenwald Reference Tannenwald1999; Reference Tannenwald2007). According to this group of scholars, both the US public and policy makers have concluded that nuclear weapons are excessively destructive, by killing noncombatants on a large scale, and that they are therefore illegitimate and repulsive (Crawford Reference Crawford, Evangelista and Shue2014; Traven Reference Traven2015). Although this “nuclear taboo” does not necessarily prevent states from having or threatening to use nuclear arsenals, there is a belief that it has restrained their actual use. Furthermore, scholars explain that non-nuclear states have also developed a moral revulsion to nuclear arsenals and have tried to stigmatize them to promote disarmament (Egel and Ward Reference Egel and Ward2022; Müller and Wunderlich Reference Müller and Wunderlich2020).

Nuclear policy trends likewise reflect this divide. In the face of great-power competition and challenges to arms control, nuclear powers have announced plans to modernize their arsenals to deter attacks on themselves and their allies (Bollfrass and Herzog Reference Bollfrass and Herzog2022). These countries have rejected calls to prohibit nuclear possession, threats, and use, which could jeopardize deterrence (Ritchie and Kmentt Reference Ritchie and Kmentt2021). Meanwhile, many non-nuclear states have moved to stigmatize the bomb with the creation of the TPNW (Gibbons Reference Gibbons2018; Herzog Reference Herzog2025). Slow progress in eliminating nuclear arsenals, together with nuclear modernization and threats, have made disarmament an appealing alternative to deterrence. For proponents of a nuclear ban, deterrence carries unacceptable humanitarian and environmental risks (Gibbons and Herzog Reference Gibbons and Herzog2022; Reference Gibbons, Herzog, Gibbons, Herzog, Wan and Horschig2023). TPNW supporters have accordingly designed public opinion campaigns to turn populations against nuclear weapons.

Nuclear scholars and policy makers thus tend to treat deterrence and disarmament as exclusionary. For some scholars, there is an important nuance. These authors have articulated a role for latent deterrence instead of nuclear possession (Fuhrmann Reference Fuhrmann2024; Schell Reference Schell1984) and argued that normative views regarding first-use preferences may fade away in nuclear retaliation scenarios (Sukin Reference Sukin2020b). By and large, however, the dichotomy remains in the often-siloed nature of academic debates and government structures. For instance, it is not uncommon for states to have separate bureaucracies working on nuclear deterrence and disarmament. This can affect policy outcomes. In some cases, NATO states that are seen as leaders on disarmament have resisted participating in sensitive nuclear planning conversations. States that are heavily invested in (extended) nuclear deterrence have generally repudiated the TPNW and declined to participate in its proceedings, even as observers.

In sum, with some limited exceptions, a preponderance of nuclear scholarship and policy analysis has long presented a landscape of incongruity between deterrence and disarmament. This is exacerbated by the literature’s emphasis on divisions in the global nuclear order based on regional geography. Although these distinctions may seem useful as teaching heuristics or policy talking points, they oversimplify the world in at least two counterproductive ways. First, they homogenize countries into regional blocs that may not accurately reflect national thinking. Second, they tend to apply official positions to diverse polities and publics, erasing important debates. These issues can lead to the appearance of scholarly discrepancies, such as different surveys showing that publics accept both sides of the apparent nuclear deterrence-disarmament binary.

The Compatibility of Deterrence and Disarmament

Despite the dominant view in the scholarly literature, we believe that it is important to build on the work of the minority of scholars suggesting some level of compatibility between nuclear deterrence and disarmament. We accordingly identify plausible mechanisms that could explain concurrent favorability toward both policies. In contrast to the dichotomous approach, we develop a framework suggesting that preferences for deterrence and disarmament may not be mutually exclusive. We then provide observational evidence—from a new wide-ranging dataset of public attitudes from states across the globe—that this is the case. Our findings and data point toward a need for future scholarship on nuclear preferences to widen analysis beyond the oft-studied US and Western European cases. Put simply, scholars must delve deeper into the causes of complexity in nuclear preferences.

While both deterrence and disarmament aim to reduce nuclear dangers, much academic research and policy decision making appear to reinforce notional mutual exclusivity. However, in a longer view, deterrence and disarmament are hardly incompatible. Instead, heterogeneous preferences at the national and international levels can lead to political outcomes that embrace both. As Maurer (Reference Maurer2018) has shown, motivations for reducing arsenals through arms control can include nuclear disarmament, deterrence stability, and military advantage. Oftentimes negotiators from opposing parties come to the table with different motivations, and seemingly divergent preferences are typical among officials within national governments. At the substate level, surveys show that publics and elites may well hold preferences that can inform policy actions in line with both deterrence and disarmament (Onderco and Smetana Reference Onderco and Smetana2021; Smetana and Onderco Reference Smetana and Onderco2022). Negotiations between governments can also produce concurrency between disarmament and deterrence policies. Most prominently, the NPT itself embraces both views, allowing the five designated nuclear weapon states—China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—to possess arsenals that enable deterrence (Art. IX, para. 3) in exchange for long-term disarmament progress (Art. VI).

Other scholarship shows that—beyond heterogeneity among different individuals—the same individuals can actually value both deterrence and disarmament at once. Instead of a dichotomy between strategy and morality, some scholars have used the distinction between categorical and consequentialist reasoning to study nuclear preferences. They analyze whether the public has principled and unmoving moral obligations (categorical logic) or if they are subject to rationalist trade-offs (consequentialist logic) (Dill, Sagan, and Valentino Reference Dill, Sagan and Valentino2022, 7–10). The deterrence-disarmament dichotomy suggests a categorical approach. In contrast, if publics use consequentialist reasoning when assessing nuclear policy, they may prefer deterrence-based options under some conditions and disarmament approaches under others. For this reason, one might, for example, support disarmament for other states but deterrence for their own. Recent work by Schwartz (Reference Schwartz2024), for instance, shows that Americans are significantly more likely to view nuclear weapon use as unacceptable when carried out by an adversary than by Washington. While categorical reasoning may be common for certain types of decision making, immovable preferences are rare for low-salience issues, such as nuclear policy among the public.Footnote 1

Consequentialists adjudicate between competing motivations and frameworks to maximize utility, rather than using categorical rules to inform their preferences. As a result, their moral thinking can filter their strategic reasoning, and strategic motivations might also shape their moral views. For example, moral foundations theory shows that information about the effects of weapon use is interpreted through individual values (Rathbun and Stein Reference Rathbun and Stein2020; Smetana and Vranka Reference Smetana and Vranka2021). Moral reasoning may therefore influence strategic preferences. In military decision making, moral preferences for restraint may also be disguised as—or conflated with—strategic ones because of contextual aversion to “emotional” decision making (Emery Reference Emery2021; Pauly Reference Pauly2018).

Consequentialist approaches also emphasize preferences that can enable individuals to accept a wide variety of pathways so long as they lead toward a valued goal. In the nuclear domain, people’s primary motivation is to protect themselves and their loved ones (Allison, Herzog, and Ko Reference Allison, Herzog and Ko2022; Dill, Sagan, and Valentino Reference Dill, Sagan and Valentino2022; Egel and Hines Reference Egel and Hines2021; Smetana and Onderco Reference Smetana and Onderco2023). Hence those who believe nuclear weapons are repulsive might also place a moral value on protection, allowing that demand to outweigh other considerations. Moreover, individuals are rarely aware of how their self-interest affects their moral reasoning (Kurzban Reference Kurzban2010). This interpretation mirrors that of many successive US presidents. If morality is instrumental to preserving one’s own security, it could seem more morally justifiable to deter a nuclear-armed adversary than to remain unprotected from adversary threats. Conversely, other scholars argue that moral reasoning in warfare is mere “window dressing” to make strategic decisions palatable. For example, researchers have attempted to understand how officials superimpose morality onto nuclear strategies, including with religious justifications (Adamsky Reference Adamsky2023). This approach can provide popular legitimacy for strategically motivated objectives.

Others argue that moral and strategic preferences coexist, but that moral preferences are only weakly held. Some research finds that individuals claim to believe in the nuclear taboo but nevertheless support situational nuclear weapon use (Press, Sagan, and Valentino Reference Press, Sagan and Valentino2013) or proliferation (Sukin Reference Sukin2020a). Psychological scholarship suggests that individuals interpret morality flexibly, with an eye toward their own strategic interests (Weeden and Kurzban Reference Weeden and Kurzban2017). To this end, individuals might selectively dismiss predominant conceptions of morality when they become an obstacle weakening their own personal security relative to others (Robinson and Kurzban Reference Robinson and Kurzban2007).

Individuals could support both deterrence and disarmament policies because they are each pathways toward reducing nuclear conflict risks. For example, arms control and deterrence can be complementary to improving strategic stability. Individuals may also distinguish between objectives with different timelines: one might support long-term disarmament but view short-term deterrence as necessary, as in the case of many US presidents. Or, policy preferences may be loosely held and subject to changing geopolitical environments. That is, individuals may prefer deterrence or disarmament, but without precluding the alternative pathway if circumstances change.Footnote 2

Accordingly, the literature is rife with examples of states that championed disarmament after political and technical obstacles ruled out nuclearization (Hymans Reference Hymans2012; Narang Reference Narang2022). Such flexible and contingent thinking is consistent with psychological literature indicating that individuals can adapt if certain frameworks of assessment would undermine their self-interests (DeScioli and Kurzban Reference DeScioli and Kurzban2013). To this end, Coppock (Reference Coppock2022) argues that people update their views in the direction of persuasive information.

These diverse mechanisms have a major similarity in that they do not necessarily separate the foundations of nuclear deterrence and disarmament. Instead, they argue that societies and individuals can hold competing preferences or even shift between decision-making frameworks when faced with different scenarios. In some cases, strategic priorities will reinforce predominately moral choices. In others, moral reasoning will underpin mainly strategic preferences. In other words, for publics and individuals worldwide, deterrence and disarmament, like strategy and morality, are not categorical, mutually exclusive approaches to managing nuclear risks.

In subsequent sections, we demonstrate the compatibility of deterrence and disarmament in three ways, based upon our novel dataset. First, we show that individuals hold simultaneous preferences for nuclear deterrence and disarmament, suggesting that an embrace of one set of policies does not constitute rejection of the other. Second, we show global approval for both deterrence and disarmament, demonstrating that this phenomenon goes well beyond the narrow set of cases that most of the literature on nuclear preferences relies upon. Our results challenge notions of geographical blocs sharing similar normative attitudes on nuclear politics. Across both the Global North and the Global South, we observe preferences for both deterrence and disarmament.Footnote 3 Third, we offer suggestive evidence that the simultaneity of deterrence and disarmament preferences may reflect individuals making situationally contingent judgments.

Being honest about any study’s limitations is important. While we cannot identify the precise mechanisms determining any individual’s nuclear preferences, our results raise questions for the dominant literature’s deterrence-disarmament dichotomy. Indeed, our data analysis highlights the importance of scholarship that nuances the compatibility of these policy directions. Taken together, our study points to considerable space in the academic literature to unpack nuclear preferences beyond simple dichotomies such as deterrence-disarmament. Future studies could test causal explanations for why individuals in different threat environments support both policies, how they rank them, and when they pivot from their first- to their second-order preferences. Our data and findings here seek to stimulate these conversations among scholars.

Methodology

To observe global nuclear policy attitudes, we conducted a novel survey in 24 countries on six continents (N = 27,250). We asked questions about both deterrence and disarmament. We find that respondents’ nuclear preferences do not fall neatly within two mutually exclusive camps, instead embracing a broad range of possibilities.

Our data contribution allows for the measurement of nuclear attitudes in societies that differ on many dimensions. Below, we zoom in on the microfoundations of attitudes toward the global nuclear order and identify consistencies and contradictions within popular opinion. Our findings challenge the perceived divide between deterrence and disarmament summarized earlier in this essay. The accompanying dataset offers scholars a much broader and more nuanced view on global nuclear preferences than any previous academic survey research on nuclear weapons.

Studying Public Opinion in the Global North and the Global South

National security and nuclear weapons have long been seen in academia as the domain of elite-level policy makers, but this viewpoint is overly limiting (Saunders Reference Saunders2019). Civil society and social movements have been instrumental in campaigns seeking to stigmatize nuclear weapons and abolish nuclear test explosions (Higuchi Reference Higuchi2020; Hogue and Maurer Reference Hogue and Maurer2022; Knopf Reference Knopf1998). Scholars studying these actors usually suggest that international civil society uses ethical arguments to create a common global morality around nuclear issues. Studies have also considered the role of domestic politics, including the influence of the public, in shaping nuclear policy (Saunders Reference Saunders2019).

Studies of nuclear attitudes generally share an emphasis on the US context, although new research focusing on other publics is emerging (Allison, Herzog, and Ko Reference Allison, Herzog and Ko2022; Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Eguchi, Nakagawa, Shibata and Tago2023; Dill, Sagan, and Valentino Reference Dill, Sagan and Valentino2022). But even this literature primarily emphasizes democratic countries in the Global North and US allies. A broader focus, including on the Global South, is necessary to draw stronger, generalizable conclusions. By sampling from both the Global North and the Global South, we avoid the pitfalls of overtheorizing from so-called WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, and Democratic) countries (Muthukrishna et al. Reference Muthukrishna, Bell, Henrich, Curtin, Gedranovich, McInerney and Thue2020).

Nuclear studies—on public opinion and otherwise—tend to draw overarching lessons from a narrow set of cases. For example, Braut-Hegghammer (Reference Braut-Hegghammer2019) identifies two kinds of US bias in nuclear scholarship. First, there is a tendency to extrapolate the US experience to study nuclear statecraft. Second, the parochial scope of US-focused studies could create a generalization bias regarding global public preferences. Hence studying nondemocracies, non-nuclear states, and states outside the Global North is necessary to advance scholarship.

Accurately evaluating public views in the Global North and the Global South matters for academic and practical policy reasons. While literature on public opinion in Global North countries often debates their willingness to support the strategic logic of deterrence, scholars readily project common moral values onto publics across Global South countries.Footnote 4 Understanding the diversity of public views is important to assess the effects of these attitudes on foreign policy. However, few studies broach the topic beyond Western democratic countries, with notable exceptions studying the approval of nuclear use in India (Schwartz Reference Schwartz2024), proliferation attitudes in Brazil (Spektor, Fasolin, and Camargo Reference Spektor, Fasolin and Camargo2022), and Chinese public opinion (Egel and Hines Reference Egel and Hines2021)

Public opinion is further relevant since policy makers have deployed campaigns to gain public support for deterrence and disarmament. NATO has committed to “raising the nuclear IQ” to convey the value of nuclear deterrence and increase public support for policies such as nuclear sharing. Meanwhile, the transnational movement of activists supporting the TPNW is focused on stigmatizing the bomb among publics to secure additional treaty ratifications (Mekata Reference Mekata2018).

Fielding a Global Nuclear Survey

In June 2023, we conducted simultaneous public opinion surveys across the world with the internet sampling firm Cint and its subsidiary Lucid. Using representative quotas based on age and gender, we assessed a sample of the public in each country under study, meaning that our samples reflect a given country’s gender balance and age distribution.Footnote 5 We collected additional demographic data, including the education level, political ideology, veteran status, income, and policy experience of each respondent.Footnote 6 Our dataset contains significant variation along these demographics, allowing us to evaluate how these characteristics correlate with nuclear attitudes.

Our sampling strategy is ideal for answering our research questions for four main reasons. First, quota-based representative samples collected by Cint and Lucid are well established as a credible data source for academic studies. They perform comparably or favorably to alternatives (Coppock and McClellan Reference Coppock and McClellan2019; Peyton, Huber, and Coppock Reference Peyton, Huber and Coppock2022). Second, gender and age correlate strongly with political demographics like ideology and party affiliation. This has made stratification on these covariates a frequently used sampling strategy for political science research. Third, although quotas forgo some benefits of random probability sampling, they are more economical and help to assure representation of males and the elderly—usually underrepresented in randomized internet and telephone sampling (Sanders et al. Reference Sanders, Clarke, Stewart and Whiteley2007; Yeager et al. Reference Yeager, Krosnick, Chang, Javitz, Levendusky, Simpser and Wang2011). Fourth, we fielded the survey at a time of unusually high nuclear salience, due largely to Russia’s persistent nuclear threats. This allowed us to capitalize on a real-world “treatment” of nuclear risk to provide observational data about nuclear attitudes, differing from past work using hypothetical experiments to temporarily manipulate perceptions.

Table 1 depicts the geographical breakdown of our respondents.Footnote 7 Our sample covers a broad geographic scope, with variation in economic strength, political systems, military capabilities, alliance memberships, and other factors that might influence nuclear policy attitudes. Our dataset includes several nuclear-armed states, as well as host states for US tactical nuclear weapon deployments (Kristensen and Korda Reference Kristensen and Korda2023). We also surveyed states without nuclear weapons on their territory, ranging from those with formal nuclear security guarantees to those lacking any nuclear assurances. The countries span both those that face nuclear-armed adversaries and other dire military threats and those that do not.

Table 1 Survey Sample Composition

Our study is ideal for examining global nuclear preferences and providing useful data for researchers. It samples several publics from the Global North and the Global South in countries that greatly differ across covariates of interest to scholars. Additionally, several publics in our study have not previously been surveyed by researchers regarding their views on nuclear weapons. We therefore present a valuable observational dataset to enhance understanding of the global distribution of nuclear attitudes.Footnote 8

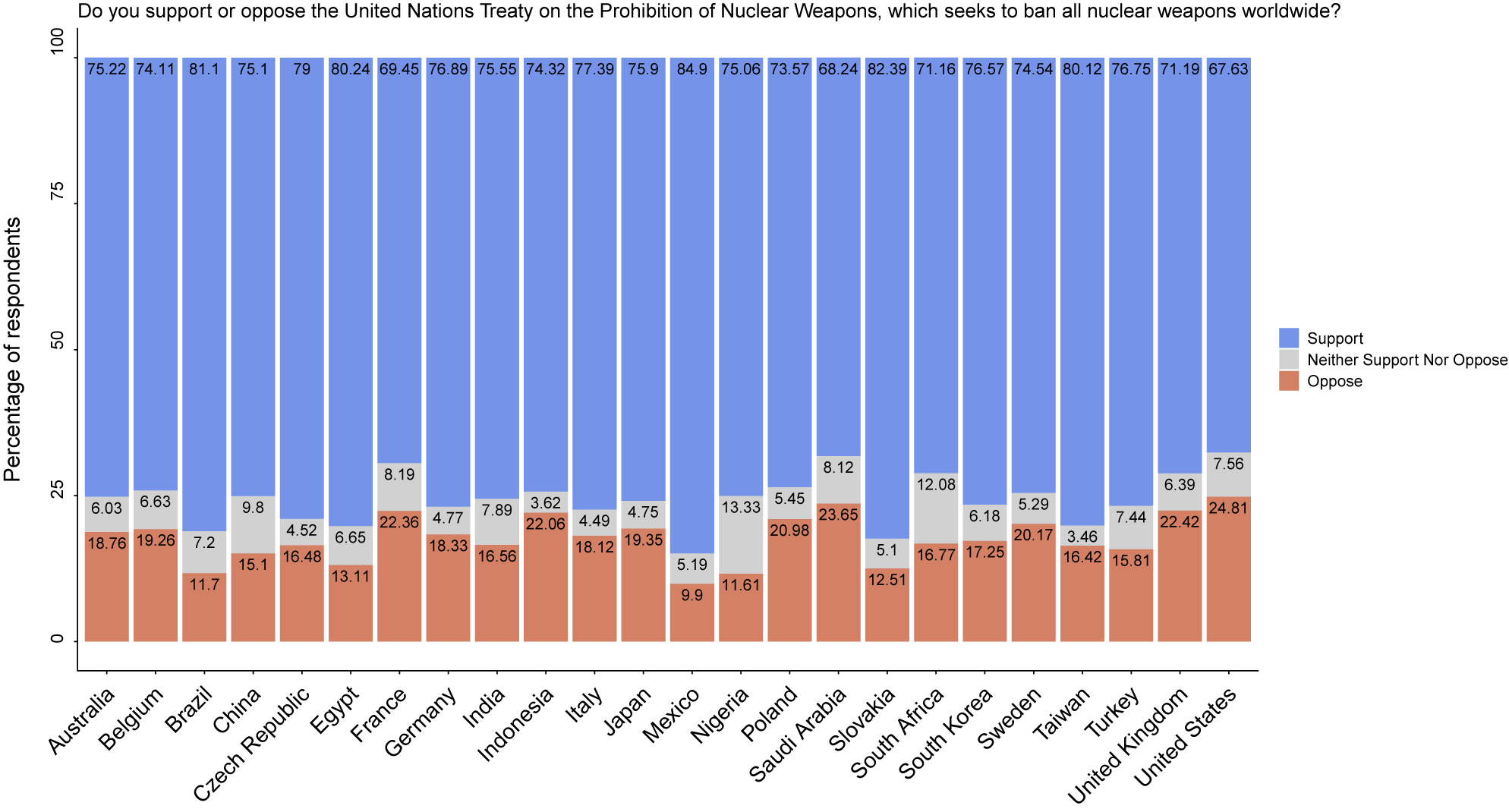

We asked respondents about their views on nuclear policy, including how they evaluate nuclear weapon use, deterrence and disarmament, and various legal and moral issues. For example, regarding disarmament, we asked respondents if they “support or oppose the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which seeks to ban all nuclear weapons worldwide” and assessed whether they believe the United States should “decrease the size of the U.S. nuclear arsenal.” We also assessed attitudes about the nuclear taboo by asking whether respondents believe that “the use of nuclear weapons can be morally justified.”

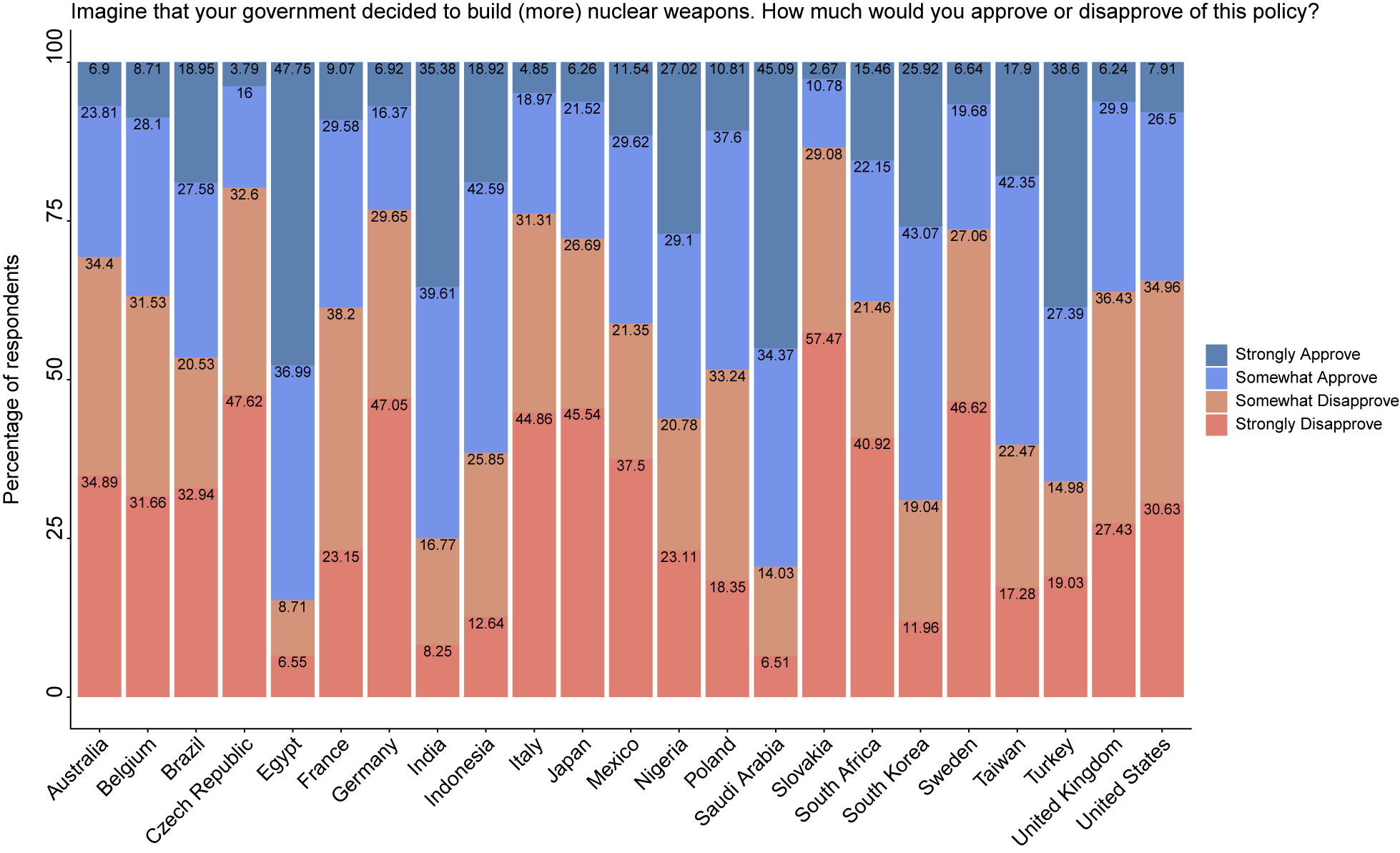

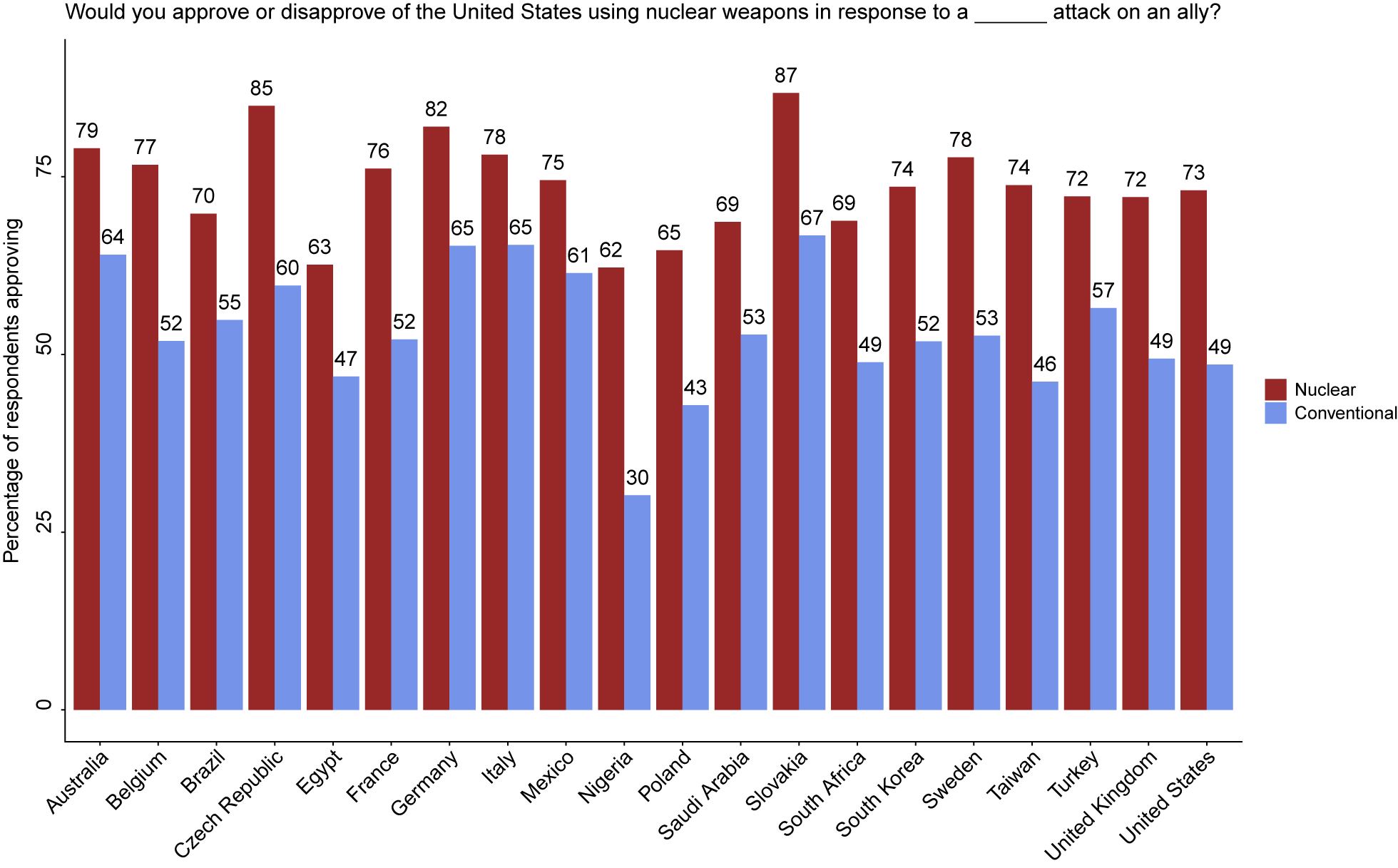

Additionally, we evaluated deterrence attitudes. These include respondents’ (dis)approval of whether their country should “build nuclear weapons” if it is a non-nuclear power or “build more nuclear weapons” if it is a nuclear-armed power. Finally, we identified views about extended deterrence by asking about (dis)approval of “the United States using nuclear weapons in response to” two scenarios of attacks on US allies. In one scenario, the adversary used “conventional (i.e., non-nuclear) weapons.” In the other, the adversary used “nuclear weapons.”

Nuclear weapons possession and use are two critical topics in nuclear scholarship. In most scholarship, nuclear possession—or umbrella protection from a nuclear-armed ally—is vital for deterrence (although deterrent benefits of nuclear latency may be plausible). Deterrence has also long been premised on credible threats of nuclear weapon use (Schelling Reference Schelling1966). Public willingness to support nuclear use could thereby influence the credibility of deterrence.Footnote 9 While a significant body of scholarship has examined public attitudes about nuclear possession and use, this literature remains geographically limited in scope. As discussed above, dominant explanations for the two most fundamental components of nuclear deterrence in most literature—nuclear proliferation and threats of nuclear use—emphasize strategic motivations, diminishing the role of moral considerations. Our survey instrument can be found in online appendix A.

As scholarship indicates, members of the public hold meaningful preferences on foreign and security policy (Jentleson Reference Jentleson1992; Kertzer Reference Kertzer, Huddy, Sears, Levy and Jerit2023). To better assess these preferences, we fielded the survey when nuclear policy was unusually salient due to nuclear threats during Russia’s war on Ukraine. High-salience topics increase respondents’ attentiveness (Bradburn Reference Bradburn1978; Lohr Reference Lohr2022).

We used several standard quality checks, including dropping inattentive respondents.Footnote 10 This ensured that our sample was composed of legitimate survey takers and reinforces that our findings are not merely an artifact of inattentive respondents. They are, in fact, consistent with the minority of scholarship suggesting some level of compatibility between deterrence and disarmament (Fuhrmann Reference Fuhrmann2024; Nye Reference Nye2023; Schell Reference Schell2007; Weiner Reference Weiner2023).

In the subsequent section, we reveal significant commonalities among publics of the Global North and the Global South regarding their understanding of nuclear dangers. Yet there are some notable distinctions between and within groups. Ultimately, we show that publics around the world have complex and noncategorical nuclear preferences. That individuals can engage in disarmament advocacy and also support nuclear deterrence raises questions about the dichotomous way these subjects have often been studied.

Both Deterrence and Disarmament

Our respondents do not categorically support nuclear deterrence or nuclear disarmament. Instead of approving or rejecting these policies in a principled and unmoving way, they express simultaneous preferences for policies that have traditionally been seen as pro- or antinuclear.

To measure attitudes about nuclear deterrence, we developed an index reflecting responses to three questions about nuclear weapon acquisition or use. The first two asked whether respondents would support nuclear use in retaliation to an attack by an adversary, in both nuclear- and conventional-strike scenarios. While these questions indicated a willingness, or lack thereof, to use nuclear weapons, the third question measured whether respondents would support their country’s horizontal or vertical proliferation. Each question was measured as a binary indicator, and the index weights each equally, such that respondents can be scored from zero (disapprove of both types of nuclear weapon use and of proliferation) to three (approve of both types of nuclear weapon use and of proliferation). While this index includes only a subset of possible pronuclear policies, it highlights two major types of nuclear behavior—possession and use—that are generally seen as critical components of deterrence. Furthermore, extended nuclear deterrence is a prominent feature of the current political order, and changing geopolitical dynamics are making discussions of nuclear proliferation more prominent in places like Canada, Germany, Poland, South Korea, and Ukraine.

To measure views on nuclear disarmament, we developed a second index. This again aggregates responses to three questions. The first is a measure of the nuclear taboo; respondents are coded as believing in the taboo if they strongly believe the use of nuclear weapons cannot be morally justified. The second focused on nuclear arms reductions and asked respondents if they would approve of the United States decreasing its arsenal. The third question indicated whether respondents support TPNW membership for their country. Respondents can score between zero (indicating nonbelief in the nuclear taboo and opposition to both strategic arms reductions and the TPNW) and three (indicating belief in the nuclear taboo and support for strategic arms reductions and the TPNW). This index represents only a subset of possible antinuclear views, ranging from attitudes about nuclear proliferation to those about nuclear weapon use. The inclusion of a measure of the nuclear taboo allows us to evaluate the primary mechanism through which scholarship has assessed moral reasoning in the nuclear domain. The TPNW question evaluates policy preferences regarding the most prominent element of the nuclear disarmament regime. The question on US nuclear arms reductions provides balance relative to the questions on extended deterrence, offering an indicator of attitudes about disarmament separate from considerations of international law.

To assess whether respondents hold seemingly contradictory views on nuclear deterrence and disarmament, we measure disagreement between these two indexes. Respondents exhibit no disagreement if they score zero on at least one index. Respondents exhibit mild disagreement if they hold a single competing view (if they score a one on each index), moderate disagreement if they hold two competing views (if they score a two on each index or a two on one index and a one on the other), and high disagreement if they hold three competing views (if they score a three on each index or a three on one index and a one or a two on the other index). We use an ordinal measure ranging from no competing views (one) to a high level of competing views (four).

Figure 1 illustrates public views in each sampled country. In every case, we find that the majority of the public holds competing views.Footnote 11 The modal respondent scores a three on the scale, indicating moderate support for both deterrence and disarmament.Footnote 12 This is not simply an indicator of respondents lacking knowledge. This finding persists if we subset the sample to veterans, respondents who indicated that they work in policy-related fields, respondents with graduate degrees, and respondents who self-report reading about politics often.Footnote 13 Entanglement also remains high regardless of age, gender, political ideology, education level, or household income.Footnote 14 Overall, respondents across the globe demonstrate very similar levels of support for both deterrence and disarmament.

Figure 1 Public Entanglement on Nuclear Deterrence and Nuclear Disarmament Views

While these preferences may seem inconsistent, they are not necessarily incompatible. For example, respondents may support deterrence for themselves but disarmament for others. This is not unlike recurrent patterns among the US public of supporting lower taxes and increased public services (Welch Reference Welch1985). This is often taken as evidence of naivety, as public services usually require higher taxes. However, further investigation reveals that the true preference is for services for oneself to be paid for with taxes of others. In this way, public attitudes are not incoherent. Another approach might suggest that this seeming inconsistency can be resolved if preferences are hierarchical; perhaps respondents prefer disarmament, but in the event of its impossibility support deterrence as an alternate route to attenuating nuclear risks. We do not adjudicate among these frames. Instead, we argue that individuals can use these and other frames to justify a wide variety of preferences aligning with their goals. Future research should explore the logic individuals use to contextualize competing preferences.

Even if the public’s views are seen to be inconsistent, this inconsistency matters. Competing support for deterrence and disarmament opens political space for savvy entrepreneurs to generate powerful coalitions favoring many different nuclear policies. The publics in our sample, across geographies and geopolitical contexts, do not have a categorical preference for deterrence or disarmament. Shrewd entrepreneurs can sway opinion in favor of different policies. For example, despite high levels of support for disarmament in Finland and Sweden, nuclear threats from Russia allowed Finnish and Swedish political leaders to persuade their publics in favor of accession to NATO, a nuclear alliance (Gibbons and Herzog Reference Gibbons, Herzog, Gibbons, Herzog, Wan and Horschig2023).

Our results are particularly noteworthy because they highlight that past scholarly results can be reconciled. That is the crux of this reflection essay: wide-aperture global public opinion data pose a substantial challenge to decades of narrow scholarship describing a deterrence-disarmament binary. On the one hand, we observe persistent global interest in nuclear proliferation. But on the other hand, we find strong support for banning the acquisition and possession of nuclear arms. Furthermore, we see that while publics are willing to support nuclear use in extended deterrence contexts, they also express moral opposition to nuclear use. This provides strong support for the idea that individuals do not make categorical distinctions between deterrence and disarmament.

To Be a Nuclear Power or Not to Be

We now delve deeper into the concurrence of support for seemingly incompatible nuclear policies. Specifically, we provide observational data on support among global publics for a variety of important nuclear policy outcomes. Our dataset on global preferences offers scholars a more comprehensive perspective on nuclear preferences than past work focusing on isolated cases and aspects of the atomic age (i.e., deterrence or disarmament). While we focus on the concurrence of support for elements of both deterrence and disarmament in this essay, our data and findings offer potentially valuable extensions to a variety of key nuclear politics work. Such work has assessed nuclear preferences—such as public support for the TPNW, nuclear proliferation, or nuclear weapon use—in a far more limited number of unique cases.

In this section, we focus on nuclear possession, showing the global distribution of preferences on a key antinuclear policy (support for the TPNW) as well as for a key pronuclear policy (support for nuclear proliferation). Although banning and possessing the bomb may appear to sharply conflict, we nonetheless find robust public support for both.

Policy tensions over the TPNW epitomize the perceived binary choice between deterrence and disarmament. Treaty advocates argue that eliminating nuclear weapons will reduce threats to humanity (Potter Reference Potter2017). Opponents claim that banning the bomb undermines deterrence, which keeps the world safe from nuclear war (Vilmer Reference Vilmer2022). Both camps seek to mitigate nuclear dangers, but they disagree on the tools for doing so. Accordingly, scholars and policy makers who label these actors as being at odds miss a fundamental similarity in their objectives.

The TPNW is among the most significant alterations to the global nuclear order since the creation of the NPT. It was negotiated by 124 states—predominantly from the Global South—in 2017 and entered into force with 50 ratifications in 2021. The treaty, which bans the possession, threat, and use of nuclear weapons, has been ratified by four states in our sample: Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, and South Africa. Brazil has signed but not ratified. Most states in our sample have neither signed nor ratified.

Yet figure 2 shows that in every sampled state, a strong majority expresses support for the TPNW and its initiative to ban the bomb. This demonstrates the global appeal of nuclear disarmament. The disjuncture between public opinion and national treaty status demonstrates one way in which antinuclear morals are not categorical. Instead, they may be bent by states facing unpredictable security environments (Mathy Reference Mathy2022).

Figure 2 Global Views on the TPNW

We find mild variation across states depending on their relationship to the US nuclear umbrella. Approximately 75% of respondents from states with nuclear security guarantees support the TPNW, only slightly less than the 77% from non-nuclear countries lacking such guarantees.Footnote 15 Pivotally, this means that public support for the treaty persists even among states that rely on US nuclear assurances.Footnote 16 These results reflect the widespread appeal and impact of the antinuclear movement, contrary to notions of a massive rift in nuclear attitudes between the Global North and the Global South. Still, gaps between public preferences and state policy highlight challenges facing disarmament advocates.

Eliminating nuclear arsenals is the fundamental goal of TPNW advocacy. However, we find that respondents are surprisingly open to nuclear proliferation—even those supporting a nuclear ban. We asked respondents whether they would approve or disapprove if their government decided to pursue an indigenous nuclear weapons program (horizontal proliferation) or expand an existing nuclear arsenal (vertical proliferation).Footnote 17 Both contravene the objectives of the TPNW.

The results appear in figure 3. In one-third of the states in our sample, a clear public majority supports proliferation. This points to much broader interest in nuclear proliferation than has been identified in previous scholarship.

Figure 3 Global Interest in Nuclear Proliferation

We find that there is significant public support in Egypt (85%), India (75%), Indonesia (62%), Nigeria (56%), Saudi Arabia (79%), South Korea (69%), Taiwan (60%), and Turkey (66%) for the acquisition or expansion of a nuclear arsenal by their governments. Many of these states face serious security threats. Notably, South Korea and Turkey are covered by the US nuclear umbrella, but interest in proliferation is strong nonetheless, raising questions about the long-term viability of nuclear security guarantees. This challenges assumptions in the literature regarding the nonproliferation value of such guarantees (Bleek and Lorber Reference Bleek and Lorber2014; Debs and Monteiro Reference Debs and Monteiro2017).

Additionally, a substantial minority of the public in several other states would support their government establishing a nuclear weapons program. These include Belgium (37%), Brazil (47%), Mexico (41%), Poland (48%), and South Africa (38%). Sizable minorities in France (39%), the United Kingdom (36%), and the United States (34%) believe their government should increase the size of its nuclear arsenal.

These results are remarkable. They show widespread global interest in nuclear proliferation, at least in principle. We find support for nuclear weapons development in countries that have been considered proliferation risks: Egypt, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Taiwan, and Turkey. We also find new evidence of interest in countries where nuclear proliferation has not been considered a substantial risk, such as Indonesia and Nigeria. This suggests that, for many countries, public opposition may not be strong enough to curb nuclear ambitions among entrepreneurial political leaders. It also suggests the need for some modicum of caution in globally expanding civilian nuclear energy.

However, this does not prevent publics from supporting the TPNW. Indeed, the three states in our sample that ratified the TPNW—Mexico, Nigeria, and South Africa—still see nontrivial support for nuclear proliferation. This may be because individuals who favor disarmament could also see deterrence as a way to reduce growing nuclear risks. This is especially the case if short-term barriers to disarmament appear insurmountable. While we cannot determine the precise mechanism(s) behind dual support for disarmament and proliferation, our results nevertheless show a clear lack of a categorical divide delineating these seemingly incompatible policies.

If one examines past survey-based studies individually, the results may seem disparate. Some studies indicate public support for deterrence and others show public interest in disarmament. Yet when we examine views toward these policies together, we observe support for both around the world. Seen in this light, our dataset helps to show why seemingly contradictory extant results are actually consistent. This is similar to how prominent scholarship characterizes public views on the use of force (Jentleson Reference Jentleson1992).

Such consistency contrasts with the Almond-Lippman consensus of the 1950s, which stated that public opinion on foreign policy was volatile and lacked a coherent structure.Footnote 18 Today, the academic consensus treats public opinion on foreign policy as structured. For example, scholarship has highlighted concerns about “hawkish minorities” that might advocate for nuclear weapon use against multiple adversaries (Dill, Sagan, and Valentino Reference Dill, Sagan and Valentino2022; Haworth, Sagan, and Valentino Reference Haworth, Sagan and Valentino2019). Our results also show potentially powerful “dovish minorities,” as well as a wide set of individuals who appear swayable in either direction. Moreover, we demonstrate the global presence of these coalitions, building upon the narrow set of cases from prior work.

On Nuclear Weapon (Non)Use

Another area of contention in the global nuclear order surrounds nuclear weapon use. Nuclear deterrence is fundamentally premised on the idea that threats to use the bomb may convey strategic benefits. But there are moral reasons why using these arms would be unacceptable, primarily emphasizing their humanitarian impacts. In our data, we find no evidence of categorical decisions about using nuclear arms. Instead, individuals can imagine both rejecting and accepting nuclear weapon use.

In this section, we compare beliefs in the nuclear taboo against preferences regarding using nuclear weapons for extended deterrence. The taboo reflects an ethical belief in the importance of nuclear nonuse. It forms a cornerstone of the global nuclear order and a basis for disarmament advocacy. As Tannenwald (Reference Tannenwald2005, 5) explains, taboo believers should categorically be unwilling to support the use of the bomb: “This taboo is associated with a widespread revulsion toward nuclear weapons and broadly held inhibitions on their use. The opprobrium has come to apply to all nuclear weapons, not just to large bombs or to certain types or uses of nuclear weapons.”

At the outset, we find that public views opposing nuclear weapon use are globally prominent. To measure the strength of the taboo, we asked respondents whether they believe that the use of nuclear weapons can be morally justified. Those who strongly disagree therefore buy into nuclear taboo logic, at least in principle. Respondents who think nuclear arms use can be moral do not demonstrate taboo thinking.

A total of 45% of all respondents strongly disagree that nuclear weapon use can be moral, compared with 8% who strongly agree, 27% who somewhat agree, and 20% who somewhat disagree. This suggests a robust global belief in antinuclear values, pointing to the generalizability of prior studies that have identified a public-level nuclear taboo in some countries.Footnote 19 However, what we find sits below the threshold of a true normative “taboo.” This may be because respondents are willing to accept nuclear weapon use in specific contexts—even if they recognize its moral implications in the abstract. Selective or conditional willingness to use nuclear weapons suggests that the anti-use norm may not be a categorical taboo.

Figure 4 displays our data on whether publics think nuclear weapon use can be morally justified. This figure shows generally high concerns about nuclear morality across the globe and substantial cross-country variation. A majority in every country except India and Nigeria strongly or somewhat disagrees with the idea that nuclear use can be moral. Antinuclear sentiment is most prominent in Slovakia (70%), followed by Italy (62%), Mexico (61%), Germany (61%), Japan (57%), the Czech Republic (57%), Sweden (54%), Turkey (53%), and South Korea (50%). Interestingly, all these countries have US nuclear security guarantees except Mexico.

Figure 4 Global Views toward the Nuclear Taboo

By comparison, strong disagreement with the principle of “moral” nuclear strikes is least prevalent in India (25%), followed by Indonesia (26%), Nigeria (27%), China (28%), Saudi Arabia (31%), Taiwan (35%), France (36%), Egypt (37%), the United States (38%), South Africa (41%), and the United Kingdom (44%). It is unsurprising that only a minority of respondents in nuclear-armed states view nuclear use as deeply immoral. These countries have numerous reasons to promote the legitimacy of their arsenals and deterrence strategies, alongside maintaining some degree of public support for nuclear use. This finding aligns with, and geographically extends, survey research showing that the British, French, and US publics are willing to support nuclear weapon use (Dill, Sagan, and Valentino Reference Dill, Sagan and Valentino2022).

The non-nuclear states whose publics exhibit little support for the nuclear taboo may be more surprising. Taiwan, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia may be easiest to explain. Taiwan faces constant threats from nuclear-armed China. Rather than leading to a perception of nuclear weapons as immoral, these threats may have normalized thinking about the bomb. In addition, Taipei relies on US security assurances, and respondents may view nuclear use in their defense as a moral act and perhaps even a necessity for national survival (Sukin and Seo Reference Sukin and Seo2024). Egypt and Saudi Arabia have had leaders who publicly expressed interest in proliferation, and both face regional nuclear threats (Sukin Reference Sukin2015). These facts may shape public receptivity to arguments about nuclear weapons. Indonesia, Nigeria, and South Africa are more difficult to understand. Unlike most states in our sample, all three have ratified the TPNW, and South Africa is the only country to have dismantled an indigenous nuclear arsenal.

These findings showcase disconnects between state positions in the global nuclear order and nuclear morals among the public. We find that publics demonstrating general support for the taboo that motivates nuclear disarmament may also be willing to endorse nuclear use in specific circumstances.

Importantly, these results again suggest that nuclear preferences may not be categorical. That is, belief in the nuclear taboo may not translate into situational opposition to nuclear weapon use. Figure 5 shows the percentage of respondents who say that they would approve of US nuclear use to defend an ally attacked with either nuclear or conventional weapons.Footnote 20 We find that respondents are quite willing to support the use of nuclear weapons, even though baseline views about the immorality of nuclear use are widespread.

Figure 5 Global Approval of US Nuclear Weapon Use

But in all cases, a majority of respondents would support the United States engaging in nuclear retaliation after a nuclear attack on one of its allies. This is true even for nonallies of Washington, although many of these are US partner states that may be concerned about the importance of American credibility for strategic stability. It suggests a strong degree of belief in the legitimacy of extended nuclear deterrence and a willingness to deprioritize or reconceptualize moral considerations in the face of security threats.

Respondents are neither strongly opposed to the first use of nuclear weapons nor their use in retaliation to a nuclear attack. Figure 5 shows that 53% of respondents across the full sample would approve of US nuclear use against a conventional attack on a US ally. This high global willingness to support nuclear strikes in the face of a major security threat—despite persistent antinuclear morals—suggests that publics prioritize what they deem the appropriate way to resolve their immediate security concerns. Even many individuals who, in the abstract, oppose nuclear use for moral reasons situationally support it for strategic reasons. In this sense, individual support for the nuclear taboo may well be a product of self-interest rather than an absolute moral conviction (Allison, Herzog, and Ko Reference Allison, Herzog and Ko2022; Press, Sagan, and Valentino Reference Press, Sagan and Valentino2013; Sagan and Valentino Reference Sagan and Valentino2017). These results suggest that individuals may be willing to relax their moral standards if failing to do so would affect their own security.

Our work provides a valuable wide view of global nuclear use preferences. As Sagan and Valentino (Reference Sagan and Valentino2021, 1094) write, outside the US case, “little is known about nuclear attitudes in other countries. … [M]ore scholars should study domestic political constraints and incentives for both nuclear proliferation and nuclear weapons use in other states.” Our dataset helps to provide a tool for such studies (Sukin, Rodriguez, and Herzog Reference Sukin, Rodriguez and Herzog2025), highlighting important cross-national variation that demonstrates the value of moving beyond a narrow US-centric focus.

Our findings question the prominent scholarly suggestion of a dichotomy between strategic and moral thinking on nuclear weapon use, which creates categorical opposition between deterrence and disarmament. Instead, we find that antinuclear morals and pronuclear strategic concerns are present across geographical boundaries, although with some cross-country variation. Our results show that it is entirely possible—even common—for individuals to simultaneously support nuclear use and believe it is immoral, just as it is common for individuals to both support nuclear proliferation and a nuclear ban. We find that nuclear morality is constrained globally by a persistent belief in nuclear deterrence and the validity of nuclear weapon use to fulfill defense commitments. These findings showcase a tapestry woven of strategic and moral thinking, and deterrence and disarmament preferences. That these considerations are concurrently at play suggests limits to the efficacy of antinuclear morals in shaping states’ behavior. By the same token, there are also limits on the viability of the strategic use of nuclear weapons and the utility of nuclear deterrence postures.

Beyond Artificial Dichotomies

Current scholarship on nuclear politics presents dichotomies that separate nuclear deterrence from nuclear disarmament and strategic from moral thinking. In this reflection essay, we present a novel dataset that lends insight into global preferences on nuclear issues. From these data, we observe complex preferences among global publics. We find both support and opposition to the bomb within the very same publics, and more importantly, the very same individuals. This raises questions about categorical distinctions between moral and strategic reasoning and perceptions of stark incompatibility between deterrence and disarmament policies. Our findings help to explain why some prior surveys have found evidence of publics that will back a breach of the nuclear taboo, while others show that these same publics want to eliminate nuclear weapons. Rather than viewing these findings as erroneous or incompatible, we point to several different mechanisms that could explain how individuals hold such competing views at once.

Future scholarship should further unpack the logics through which these seeming incompatibilities operate. For example, studies could investigate whether individuals hold contrary preferences for themselves versus others. Our dataset allows for deeper investigations, on a state-by-state basis, of nuclear preferences. These data could therefore help to improve and inform scholarship on nuclear possession and use that has often generalized from US behavior (or a small set of additional cases). Furthermore, while some scholarship has examined differences in nuclear attitudes between the public and elites, additional work is needed to understand the degree to which elites demonstrate the preference flexibility we observe in public opinion. Examining the moderating effect of nuclear knowledge and messaging could further illuminate how nuclear opinions are formed. Studies exploring different sets of deterrence and disarmament policies—from nuclear sharing in NATO to arms control with China to conventional deterrence—could elucidate the ramifications of public openness to both moral and strategic approaches to nuclear thinking. Our study may also serve as a baseline for future work assessing changes across time in nuclear attitudes.

This work has important policy implications. Disarmament advocates have long hoped that spreading antinuclear morals would lead to a categorical rejection of nuclear weapons. We find, however, that support for nuclear disarmament can be both strategic and conditional. For example, preferences for proliferation are a warning that crises are possible if institutions like the NPT and TPNW fail to contain growing nuclear risks. Our approach suggests that the durability of antinuclear morals may be tied to the strategic viability of norms-focused pathways for risk reduction. Individuals with strong disarmament views may potentially come to support deterrence if it is the most viable pathway to reducing nuclear dangers for themselves, their loved ones, and their country.

However, even publics in states that rely on (extended) nuclear deterrence express a belief in the taboo and support for the TPNW. Leaders may have to take their publics’ reticence to accept the high moral cost of owning or using nuclear arsenals into account in how they shape and execute policy. At the end of the day, potentially malleable public views in the nuclear domain may open rhetorical space for leaders, politicians, and activists to successfully make the case for various policies that embrace either, or both, deterrence and disarmament thinking.

Data Replication

The replication data for this article can be found in the file df_replication.csv. The replication code, written in R, can be found in the file replication_code.R. All tables and figures can be recreated using this code and dataset.

More information about the dataset can be found in the online appendices. Appendix A contains the English-language questionnaire text for each item that appears in the dataset, along with the variable name and an explanation of the recode values.

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VPJUA8.

Acknowledgments

For their feedback, the authors thank Charli Carpenter, Fiona Cunningham, Alexandre Debs, Janina Dill, Jennifer Erickson, Julie George, Sidra Hamidi, Ruoyu Li, Ryan Pike, Scott Sagan, Livia Schubiger, and Man-Sung Yim. They are also grateful for comments from seminar participants at the KAIST Graduate School of Science and Technology Policy, the Alva Myrdal Centre for Nuclear Disarmament at Uppsala University, George Mason University’s Schar School of Policy and Government, the Project on Managing the Atom at Harvard University’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, and the Yale Nuclear Security Program. The authors appreciate the support and feedback of the Ethics, Law, and Nuclear Deterrence Working Group of the Research Network on Rethinking Nuclear Deterrence, an initiative of the MacArthur Foundation and the Project on Managing the Atom. For assistance with survey translation and localization, the authors thank Fahad Abdulrazzaq, Giles David Arceneaux, Jonathan Baron, Alexander K. Bollfrass, Ludovica Castelli, Debak Das, Hassan Elbahtimy, Eliza Gheorghe, Annabelle Gouttebroze, Kate Hampton, Shubhankar Kashyap, Jiyoung Ko, Emilija Krysen, Dominika Kunertova, Alexander Lanoszka, Karen Lin, Farah Masarweh, Adrian Matak, Ulrika Moller, Sizwe Mpofu-Walsh, Rohan Mukherjee, Toby Nowacki, Olamide Samuel, Maki Sato, Woohyeok Seo, Michal Smetana, Matias Spektor, Yogi Sugiawan, Rahardhika Utama, Sanne Verschuren, and Jiahua Yue. Any errors are the authors’ own. The authors acknowledge funding and support from the London School of Economics and Political Science, the Carnegie Corporation of New York (G-PS-24-61252), the Center for Security Studies at ETH Zurich, the Yale Nuclear Security Program, the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University, Charles University’s University Research Centers (UNCE) program (Grant 24/SSH/18, “Peace Research Center Prague II”), Duke Kunshan University, and the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs.