Introduction

The Dutch political landscape is notoriously unpredictable and volatile. Yet, 2023 stood out as the most turbulent year in Dutch politics in at least two decades. Within a span of just nine months, the country witnessed both provincial and national elections, each dominated by two distinct issues: agriculture and migration. These elections yielded resounding victories for two different populist parties: the FarmerCitizensMovemen/BoerBurgerBeweging (BBB) won the provincial elections and became the largest party in the upper house of parliament, while the radical right-wing populist Party for Freedom/Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV) secured a landslide victory in the elections for the lower house. These elections also marked the second most successful breakthrough (after the List Pim Fortuyn in 2002) by a newcomer party since the introduction of universal suffrage, with the newly founded social-conservative New Social Contract/Nieuw Sociaal Contract (NSC) winning 20 seats from scratch. Moreover, the year witnessed the collapse of the centre-right cabinet, the resignation of Mark Rutte—who had been the longest-sitting Prime Minister (PM) in Dutch political history—and leadership changes in more than half of the parties represented in parliament. Not since the eventful “long year 2002” (Brants & Van Praag Reference Brants and Van Praag2005) did the Netherlands see such a tumultuous political year.

Election report

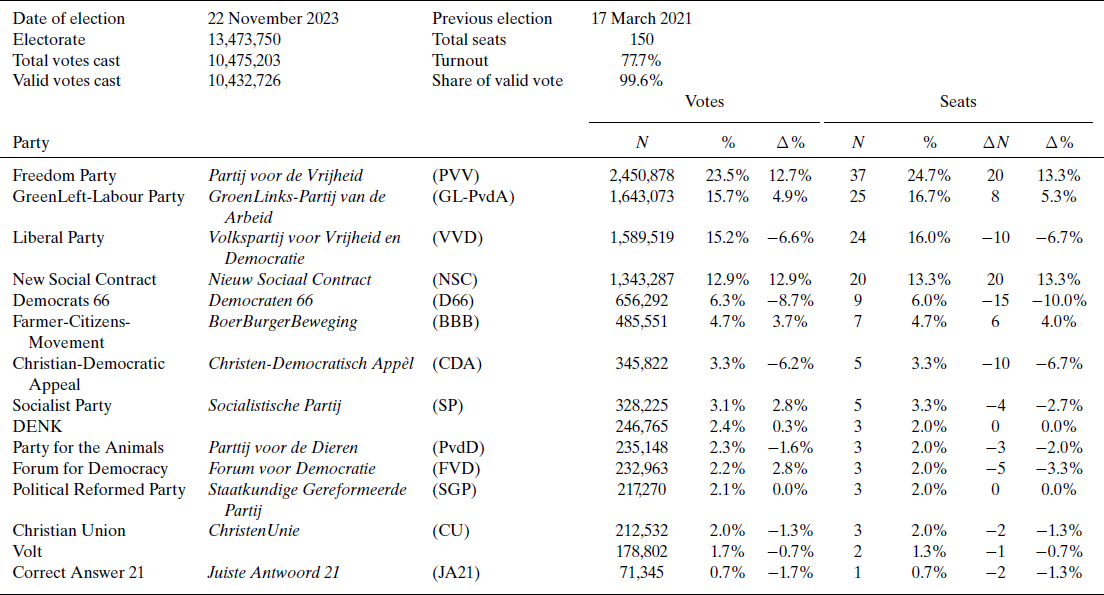

The year 2023 featured two main elections: the provincial council elections, which determine the composition of the upper house (Eerste Kamer der Staten-Generaal or Senate), and the elections to the lower house of parliament (Tweede Kamer or House of Representatives). Both elections were particularly volatile—even by Dutch standards.

Provincial and Senate elections

The provincial elections held on 15 March resulted in major changes: the BBB, which had previously not been represented in the provincial councils, became the largest party across all 12 provinces by capturing one-fifth of the votes. Electoral volatility reached 29 per cent. Voter turnout exceeded that of the previous provincial election, reaching 58 per cent (a two-percentage-point increase).

The campaign was dominated by the division between nature preservation and agricultural interests. Founded in 2019, the BBB effectively asserted “issue ownership” over agricultural interests. Despite initially securing just one seat in the lower house during the 2021 general election, this small agrarian-populist party managed to mobilize widespread dissatisfaction in the run-up to the provincial elections. It did so in three distinct ways. First, the party tapped into discontent surrounding the government's nitrogen policy by speaking out against the proposed agricultural reforms. Second, the BBB mobilized rural grievances by emphasizing the alleged cultural difference between the rural “heartland” and urban elites (see Arter Reference Arter2023). Finally, the party capitalized on general dissatisfaction with the government's handling of various past crises, including the child benefit allowance scandal (Otjes & Voerman Reference Otjes and Voerman2022), the controversy surrounding gas extraction in Groningen, and soaring inflation rates (Otjes & De Jonge Reference Otjes and de Jonge2023).

Given these crises, the four governing parties had anticipated losing seats in this “midterm” election, with the only uncertainty being the extent of the setback. The Liberal Party/Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD) lost one-fifth of its vote share, compared to 2019, and ended up in third place. The social-liberal Democrats 66/Democraten 66 (D66) saw an equally substantial decrease in support. Despite the fact that D66's centre-left positions on agriculture and migration often clashed with those of the more right-leaning VVD and Christian-Democratic Appeal/Christen-Democratisch Appèl (CDA), the party saw itself forced to accept a continuation of the existing and, by then, unpopular center-right government (Otjes & De Jonge Reference Otjes and de Jonge2023). The CDA had been polling poorly since the summer of 2021, when the popular Member of Parliament (MP) Pieter Omtzigt left the party due to personal clashes. Another reason for the party's loss in support had to do with concessions the once farmer-friendly party made on nitrogen policy to D66. Although the CDA had expressed dissatisfaction with the coalition's nitrogen policy, the party failed to effect policy changes. All this resulted in a dramatic loss in support of 40 per cent, compared to 2019. The Christian-social ChristianUnion/ChristenUnie (CU), which had been remarkably stable in electoral terms over the past two decades, also lost one-quarter of its votes, largely due to the divisive issue of nitrogen, which exposed tensions between its relatively pro-environmental party leadership and its traditional rural base.

The centre-left Labor Party/Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA) and GreenLeft/GroenLinks (GL) cooperated intensively in these elections. Back in the summer of 2022, they had committed to forming a joint group in the Senate after the provincial elections (Otjes & De Jonge Reference Otjes and de Jonge2023). This collaboration aimed to prevent the two parties from being pitted against each other by the government in search for a Senate majority. Both parties experienced minor losses in the provincial elections, compared to 2019: GL lost approximately 14 per cent of its votes, while the PvdA merely lost 2 per cent. The three other left-wing parties showed mixed results: the far-left Socialist Party/Socialistische Partij (SP) lost 30 per cent of its votes, while the deep-green Party for the Animals/Partij voor de Dieren (PvdD) garnered 10 per cent more votes than in 2019. The new pan-European party, Volt, participated in provincial elections for the first time and secured 3 per cent of the overall votes.

On the right end of the political spectrum, Forum for Democracy/Forum voor Democratie (FVD) experienced a devastating blow by losing 80 per cent of its support, compared to 2019. Initially positioned as a Eurosceptic party to the right of the VVD, FVD had emerged as the prominent winner in the 2019 provincial elections (Otjes Reference Otjes2021), but then gradually embraced conspiracy theories and extremist rhetoric. As a result of this, Yes21/JA21, a more moderate faction split from FVD and managed to secure 4 per cent of the votes. Before the start of the campaign, the populist radical right PVV appeared to be in an opportune position due to FVD's collapse to its right and an unpopular government to its left. While the polls leading up to the elections looked favorable for the PVV, the party faced a setback by losing a sixth of its votes, primarily to the BBB.

Amidst a political landscape of significant upheaval, the Political Reformed Party/Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij (SGP) maintained its 2.5 per cent share of the votes. Meanwhile, the pensioners’ party 50PLUS experienced internal dissension and lost 40 per cent of its votes but managed to keep one seat in the Senate. Finally, the Independent Politics Netherlands/Onafhankelijke Politiek Nederland, an alliance of regional parties, received enough votes in provincial councils to maintain its single seat in the Senate.

The provincial councils elect the Senate based on proportional representation.Footnote 1 The formal Senate elections were held on 30 May, during which the government coalition managed to expand its seats from the anticipated 22 to 24 (results in Table 1). This was largely thanks to strategic voting by some provincial councilors of D66 and VVD, who voted for CDA and CU instead of their own party. However, this maneuver would have resulted in the loss of a seat for the SGP; in order to prevent this, a CU councilor voted for the SGP. In an unexpected turn, one provincial councilor from GL in South Holland, who had previously been at odds with her party, voted for Volt instead of her own party. Because of this, GL lost one senator, compared to the anticipated outcome, while Volt gained one. Despite the intricate negotiations and vote trading, the election failed to bolster the stability of the government coalition, which now had to seek support from either GL-PvdA or BBB, which garnered 14 and 16 seats, respectively. The instability within the coalition came to a head on 7 July, which eventually led to the collapse of the cabinet due to disagreements over migration policy.

Table 1. Elections to the upper house of the Parliament (Eerste Kamer der Staten-Generaal) in the Netherlands in 2023

Note: aRan as Independent Senate Group/Onafhankelijke Senaatsfractie (OSF) in 2023.

Source: Kiesraad (2023).

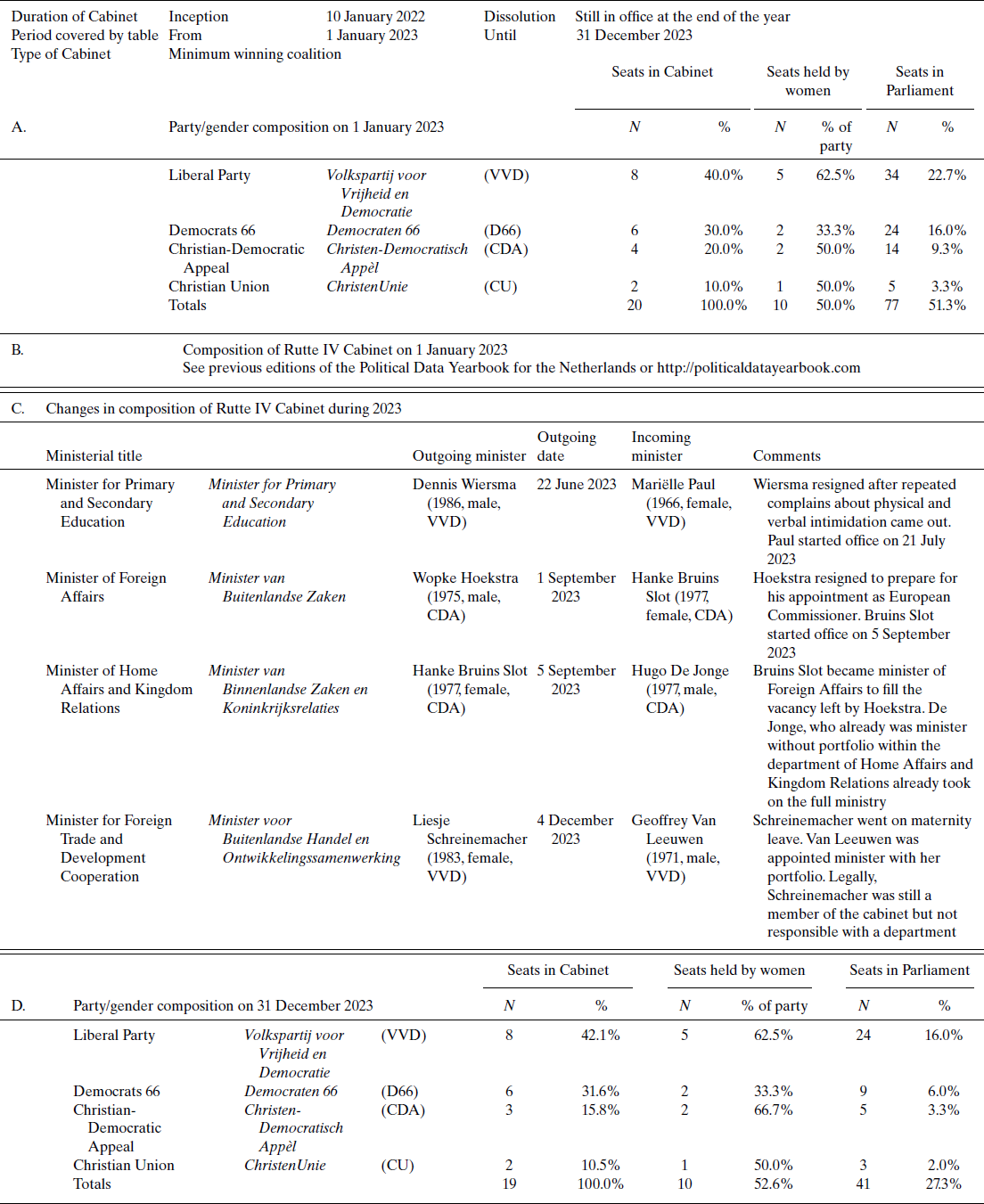

House of Representatives elections

The fall of the cabinet (see Cabinet Report) resulted in early elections, which were held on 22 November. The provincial elections discussed above already provided some insight into the positioning of the major parties at the time: The recently collapsed governing centre-right coalition faced widespread disapproval due to ongoing scandals and the ensuing compromises required to maintain unity between centre-left and right-wing parties. This environment fostered potential for anti-establishment parties, with three contenders vying for these votes: BBB, PVV, and the newly formed NSC. Additionally, the election was characterized by intensive cooperation between GreenLeft and the PvdA (explained below). The results are summarized in Table 2. In terms of seat changes, the election marked the highest volatility (36 per cent) since the first election with proportional representation in 1918.

Table 2. Elections to the lower house of the Parliament (Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal) in the Netherlands in 2023

Note: 1. GreenLeft-Labour Party ran as two separate lists in 2021. 2. Denk means “think” in Dutch and “equal” in Turkish.

Source: Kiesraad (2023).

The ruling VVD set the course of the overall election campaign, which played an important role in determining its outcome. First, after 13 consecutive years as PM, Mark Rutte stepped down and was succeeded by Dilan Yeşilgöz. Second, by forcing a cabinet crisis over migration, the VVD also chose to make migration the dominant issue in the campaign, but since the PVV is seen as “issue owner” on migration, this tactic ultimately proved advantageous for the PVV. Finally, Yeşilgöz announced early on in the campaign that she would be open to governing with the PVV. This marked a clear break with Rutte, who had consistently barred the PVV from coalition involvement since 2012, and made the PVV more appealing to voters, as the prospect of government participation became tangible; in other words, voting for the PVV was no longer just a “protest vote.” Concurrently, this move contributed to legitimizing the PVV by softening its extremist image. The VVD's campaign strategy ultimately helped till the field for the PVV: 15 per cent of VVD voters in 2021 shifted their support to the PVV in 2023, affirming the long-standing notion that voters ultimately prefer the “original” over the “copy” when it comes to issue ownership over migration. The VVD ultimately lost 30 per cent of its votes and, similar to the result in the provincial elections, ended up in third place.

As the recognized “owner” of migration issues, the PVV benefitted from the campaign's focus on migration and the VVD hinting at potential government cooperation. In this respect, the victory was a textbook example of how centre-right parties can contribute to the rise of the radical right (Krause et al. Reference Krause, Cohen and Abou-Chadi2023; Van Spanje & De Graaf Reference Van Spanje and De Graaf2018). The party also benefitted from structural factors, notably widespread political dissatisfaction and the tumultuous coalition negotiations of 2021 (Otjes & Voerman Reference Otjes and Voerman2022). Moreover, a substantive portion of the Dutch electorate supports migration restrictions while aligning more with left-leaning economic policies. This convergence of issues proved advantageous for the PVV, striking what De Lange (Reference De Lange2007) previously referred to as a “new winning formula” for the radical right. The PVV's landslide victory must also be partially attributed to the normalization of far-right discourses, evident both in the media and within centre-right parties over recent decades (De Jonge & Gaufman Reference De Jonge and Gaufman2022). In particular, the PVV capitalized on press coverage that cast Wilders as a milder version of himself, dubbed “Geert Milders.” This portrayal likely made Wilders and the PVV more palatable to a broader audience, contributing to the party's electoral success. Turning to the supply side, the PVV also benefitted from the experience and wit of its leader, Geert Wilders, who flourished during televised debates while his direct competitors fumbled the ball. Consequently, the PVV emerged as the largest party by a considerable margin, doubling its 2021 result and securing 37 seats out of 150. Despite indications of a PVV surge in the last week of the campaign, this overwhelming victory came as a surprise.

After the fall of the cabinet, plans about a left-wing cooperation (which had intensified in the run-up to the 2023 provincial elections) gained momentum. GL and PvdA decided to run with a joint list, a joint manifesto, and a common lead candidate. This was the most intense form of progressive cooperation since the 1970s. The joint manifesto focused on both the need to take far-reaching measures to mitigate the climate crisis while also highlighting the necessity to invest in and reform the public sector. The new alliance selected Frans Timmermans as the lead candidate, a seasoned leader with extensive experience, including nine years as vice-president of the European Commission focusing on the Green New Deal and the Rule of Law, along with prior roles as Foreign Affairs Minister and an 11-year tenure as an MP in the Dutch Parliament. Given his national and international expertise, the aim was for Timmermans to potentially succeed Mark Rutte as PM. However, critics voiced concerns about Timmermans having lost touch with the Dutch voters after nearly a decade in Brussels. With 25 seats, nearly 50 per cent more than the parties had individually garnered in 2021, the joint list became the second-largest party. Overall, however, the joint campaign fell short of expectations. Timmermans, instead of emphasizing his eco-social agenda, was perceived as overly preoccupied with forming the next government.

The election also saw the breakthrough of a new party, NSC, led by former CDA MP Pieter Omtzigt, which won 20 seats—the second-best result of a newcomer party since the introduction of universal suffrage, yet fewer than anticipated based on pre-election polling. NSC was founded on 19 August, just three months before the elections. Just like the CDA, NSC is rooted in Christian-democratic principles, emphasizing the significance of community over both the state and the market. NSC focused on three core issues: reforming the governing culture to prevent future scandals, exemplified by the childcare benefit scandal, which Omtzigt helped uncover; addressing the pressing concerns of the cost-of-living crisis by advocating targeted spending on poverty reduction; and advocating for stricter immigration policies, notably by proposing a maximum net migrant level of 50,000 individuals per year. The NSC list comprised former CDA and VVD MPs, along with individuals who had been involved in or affected by significant scandals, including victims of the childcare scandal and civil servants who had tried to prevent it. Omtzigt was widely respected and trusted, notably for his dedication to uncovering the childcare benefit scandal, which he prioritized over political considerations, party ties, or personal ambitions. However, his lack of charisma, decisiveness, and communicative clarity became apparent in the final weeks of the campaign, causing the party to underperform. Crucially, Omtzigt was ambiguous on whether or not he would be willing to become PM in case his party were to win the election; it was only a few days before the elections that he reluctantly succumbed to pressure and stated that he would consider the position, albeit only within a “cabinet of experts.”

For the left-leaning parties, broadly defined, the elections were a bloodbath. Smaller left-wing parties were already apprehensive about losing voters due to strategic ballots for Timmermans. However, the harsh reality exceeded their concerns: Collectively, progressive and left-leaning parties (GL-PvdA, D66, SP, PvdD, CU, Volt, BIJ1) lost 18 seats, leaving them with a mere 50 out of 150 seats in Parliament. D66, which had come in second in the 2021 elections, lost two-thirds of its votes. Notably, more people who had voted for D66 in 2021 opted for the GL-PvdA this time around. The Socialist Party lost half of its votes. For its social-conservative working-class electorate, the NSC appeared to offer a more credible social profile, while the PVV was seen as a viable alternative on migration. The Party for the Animals lost almost half of its votes due to internal conflicts (see below). The pan-European party Volt lost one-third of their votes, in particular to GL-PvdA. The Christian-social CU also experienced a significant loss of seats for the first time in over 12 years, similar to the results in the provincial elections. The only smaller left-wing party to gain votes was DENK, which represents bicultural citizens.

Smaller parties on the right (from the centre-right to the far-right) also faced significant challenges, primarily due to competition from the PVV and NSC. Taken together, CDA, BBB, SGP, FVD, and JA21 had held 30 seats in 2021 but were left with 19 in 2023. The agrarian-populist Farmer-Citizen-Movement, which had achieved a significant victory in the provincial elections in the spring, received less than 5 per cent of the vote. Several factors contributed to the decline of the BBB. First, the entry of NSC into the political race, which also tapped into dissatisfaction among voters, put the BBB in a difficult position. Second, unlike the provincial elections, the general elections focused on migration (as opposed to agriculture). Moreover, the selection of Mona Keijzer, a former CDA junior minister, as the BBB's candidate for PM did not bolster support for the party. The BBB underperformed, compared to the provincial elections just months earlier.

With significant competition emerging on the right from parties like NSC, PVV, and BBB, the CDA experienced a substantial loss of support, with two-thirds of its votes diminishing. In fact, more individuals who voted for the CDA in 2021 shifted their allegiance to NSC in 2023 than remained loyal to the CDA.

Meanwhile, the far-right FVD lost more than half of its seats under pressure from the PVV, while its more moderate splinter, JA21 lost two-thirds of its votes due to internal conflicts. Despite significant changes in the political landscape, the conservative protestant SGP maintained its three seats in the lower house, thereby providing a semblance of stability amidst the upheaval.

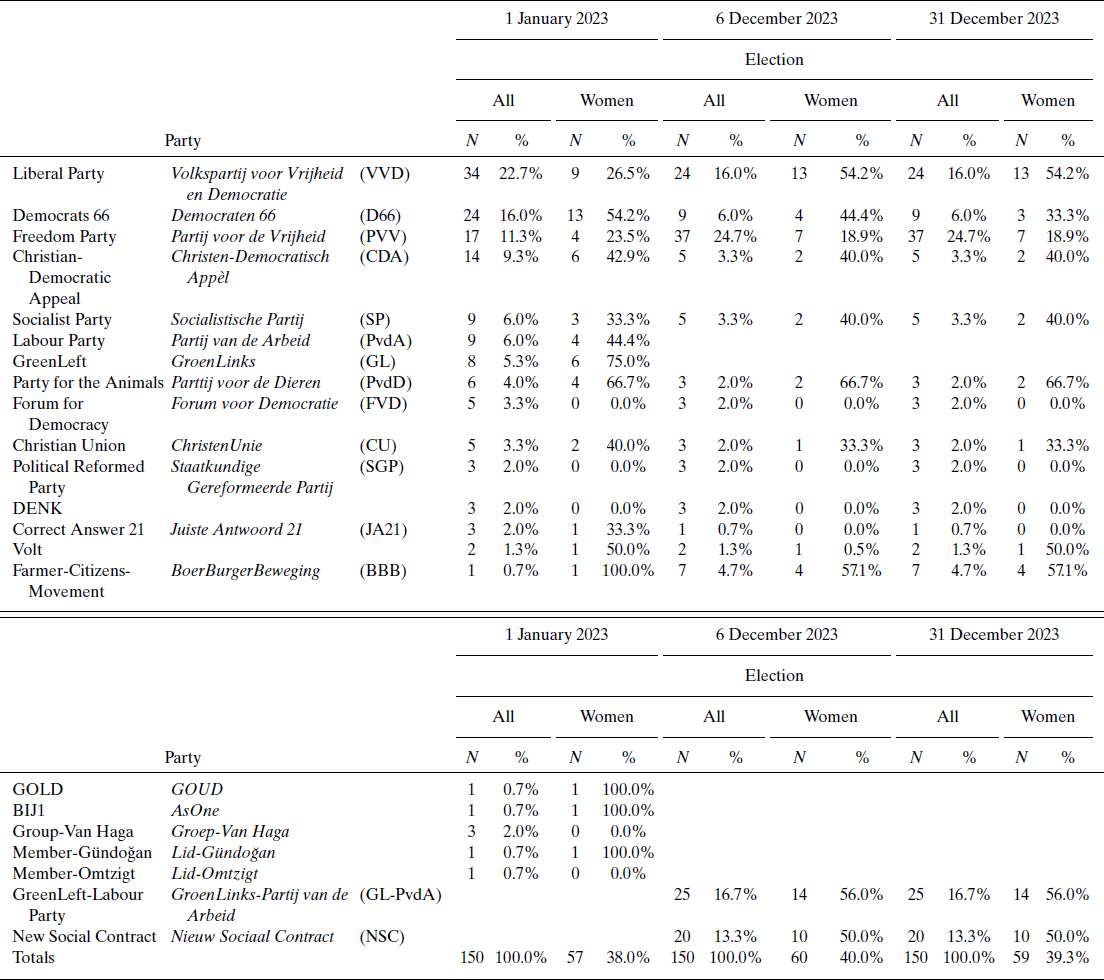

Cabinet report

Rutte IV Cabinet

In 2023, the Rutte IV Cabinet collapsed and experienced a considerable number of changes (summarized in Table 3), which is quite unusual for a caretaker government.

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Rutte IV in the Netherlands in 2023

Note: The Cabinet never had a majority in the Senate. It became a minority coalition government after the 2023 lower house elections.

Source: Parliamentary Documentation Centre (PDC).

On 22 June, Dennis Wiersma (VVD) resigned from his position as Minister for Primary and Secondary Education following numerous complaints about physical and verbal intimidation that became public. The tipping points came when reports surfaced about his behavior toward organizers of an education conference, which took place after he had publicly apologized for previous incidents. Wiersma's resignation occurred amidst a broader spotlight on transgressive behavior in Dutch politics and society, which had also resulted in several political resignations in 2022 (Otjes & De Jonge Reference Otjes and de Jonge2023). On 23 July, he was succeeded by Mariëlle Paul, the education spokesperson for the VVD. This marked the first time in Dutch political history that the Cabinet had more female members than male members.

On 7 July, the Dutch Cabinet fell over migration policy disagreements. In previous years, VVD-led governments had initiated budget cuts for housing asylum seekers, which resulted in serious and persistent accommodation shortages. To address these shortages, the cabinet proposed a migration bill that would allow the central government to force municipalities to house asylum seekers. Yet, internal divisions within the VVD over this bill prompted its parliamentary party group (PPG) to ask for a broader package to curb immigration in exchange for supporting the allocation bill. The negotiations involved a comprehensive agreement aimed at restricting migration to the Netherlands (including labor migration, family reunification, asylum and study migration). The most contentious issue was asylum policy: the VVD, with the support of the CDA, demanded tougher measures, while D66 was opposed, and the CU pinned down a number of red lines that the party was not willing to cross. One of these red lines pertained to imposing limits on family reunification. On 5 July, when the Cabinet delegation was close to a deal, PM Rutte insisted on additional restrictions on family reunification. When the CU refused to accept, the cabinet collapsed.

While serving as a caretaker cabinet, Rutte IV experienced significant turnover: because Frans Timmermans had become the candidate for the GL-PvdA joint list, he had to leave the European Commission. On 1 September, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Wopke Hoekstra (CDA), left the cabinet to assume the role of the next European Commissioner for Climate Action. Hanke Bruins Slot (CDA), who was the Minister of Home Affairs and Kingdom Relations, succeeded Hoekstra, while her portfolio was merged with that of Hugo de Jonge (CDA), who already served as the Minister for Housing and Spatial Planning within the Ministry for Home Affairs and Kingdom Relations. This further shifted the gender balance in the Cabinet to 11 women and eight men. Karien van Gennip, the Minister for Social Affairs and Employment, became the CDA's vice-PM.

On 29 October, Eric van der Burg (VVD), the State Secretary for Justice and Safety temporarily stepped down due to illness. In an unusual move, he was replaced by someone from another department, namely, Christophe van der Maat (VVD), who also kept his position as State Secretary for Defence. Van der Burg returned on 24 November.

Then, on 1 December, Gunay Uslu (D66), the State Secretary for Education, Culture and Science, resigned to return to her family's business. On 5 December, she was succeeded by Steven van Weyenberg (D66), who had previously served as State Secretary of Infrastructure and Waterworks between 2021 and 2022.

Finally, on 4 December, Liesje Schreinemacher (VVD), the Minister for Development Cooperation and Foreign Trade, went on maternity leave. In another unusual move, she was replaced by Geoffrey van Leeuwen, a high-ranking civil servant in the Ministry of General Affairs but also a member of the VVD.

The formation of a new cabinet

Just before the election, on 18 October, the lower house adopted a motion regarding the government formation process. It established some ground rules concerning the appointment of a scout by the (outgoing) Speaker of the lower house before the new house is installed. According to these rules, the largest party would have the right to propose a candidate; however, this should be someone with sufficient distance from daily politics and broad support among party leaders.

On Friday 25 November, the PVV nominated Gom van Strien, one of the party's senators, as a scout. However, the next day, the NRC newspaper broke the news that Van Strien was facing prosecution for embezzlement from Utrecht University. On 27 November, he stepped down, and on 28 November, Ronald Plasterk, a former PvdA minister and columnist in the right-wing De Telegraaf newspaper was appointed as the new scout. Plasterk had previously expressed support for a coalition consisting of PVV, VVD, NSC and BBB after the elections.

On 13 December, Parliament convened to discuss coalition formation and appoint Ronald Plasterk as the informateur to lead talks between PVV, VVD, NSC, and BBB. Together, these parties held 88 out of 150 seats. However, one main hurdle was that Omtzigt had explicitly spoken out against cooperation with the PVV before the elections, arguing that many of its anti-Islam proposals were unconstitutional and in violation of the rule of law. On election night, Geert Wilders announced that he would be willing to set aside some of the more unconstitutional demands of his manifesto and instead prioritize issues such as curbing migration, addressing the cost-of-living crisis, and investing in healthcare. In light of the concerns voiced by Omtzigt, however, the ensuing coalition talks led by Plasterk would initially focus on ensuring alignment with the Constitution, protecting civil rights, and upholding the rule of law.

Another issue that emerged was the nature of the cabinet. The VVD has already signaled its preference to serve as a supporting party in a minority government, while the NSC had expressed an interest in an “extra-parliamentary” government, as a way to force a more distant relation between parliament and the cabinet. In such a construction, the formateur would select ministers who have some distance from daily politics and task them with drafting a government program. This differs from the traditional approach, where the PPGs of the coalition parties commit themselves to a coalition agreement.

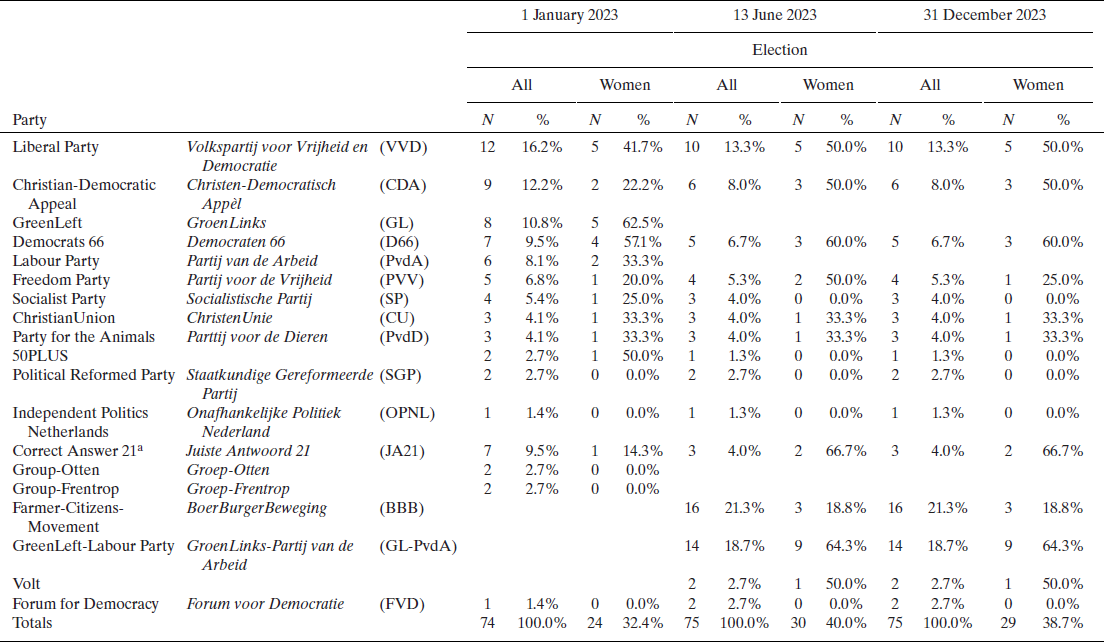

Parliament report

Tables 4 and 5 summarize the composition of the lower and upper house. On 19 February, the Parliamentary Inquiry Committee on the Groningen Gas Extraction presented its final report. The report acknowledged that the Dutch government owed a debt of honor toward the people in this province of Groningen who had been affected by man-made earthquakes due to gas extraction.

Table 4. Party and gender composition of the lower house of the Parliament (Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal) in the Netherlands in 2023

Note: The parliamentary party group (PPG) of the Party for the Animals includes Ines Kostić, the first non-binary MP.

Sources: Kiesraad (2023); PDC (2023).

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the upper house of the Parliament (Eerste Kamer der Staten-Generaal) in the Netherlands in 2023

Note: aFormally Group-Nanninga until 12 June 2023.

Sources: Kiesraad (2023); PDC (2023).

On 27 July, the lower house opted to postpone the Parliamentary Inquiry on COVID-19; only a parliamentary minority supported the idea of having one of their MPs participate in the process. The coalition parties CDA, D66, and CU, which had been involved in the preliminary research process, preferred to await the findings of the Research Council for Safety before proceeding with the inquiry.

On 2 August, Olaf Ephraim left the PPG of the Interest of the Netherlands/Belang van Nederland (BVNL) to continue as an independent MP. He did so because he had not been included on the candidate list of BVNL for the upcoming elections. Member Ephraim became the 20th PPG in the Dutch Parliament, which set a new historical record. However, on 26 October, the day before the start of parliamentary recess, GL and PvdA merged to form a joint PPG, which reduced the number of PPGs back to 19.

On 6 September, the public hearings of the Parliamentary Inquiry Committee on Fraud Policy and Service Provision started. This committee was a successor of the parliamentary interrogation committee that had caused the resignation of the Rutte-III Cabinet.

On 14 December, the newly elected lower house elected Martin Bosma as the new Speaker. Bosma had extensive experience in parliamentary affairs, having served as a long-standing member of the presidium of the house. He had chaired numerous sessions of parliament, including acting as Speaker pro tempore after elections. Despite two previous attempts to become speaker, Bosma had never been elected before; as a member of the radical right-wing populist PVV PPG, he had made numerous false statements, propagated the “great replacement” conspiracy theory, and proposed legislation that was deemed unconstitutional by the Council of State.

Political party report

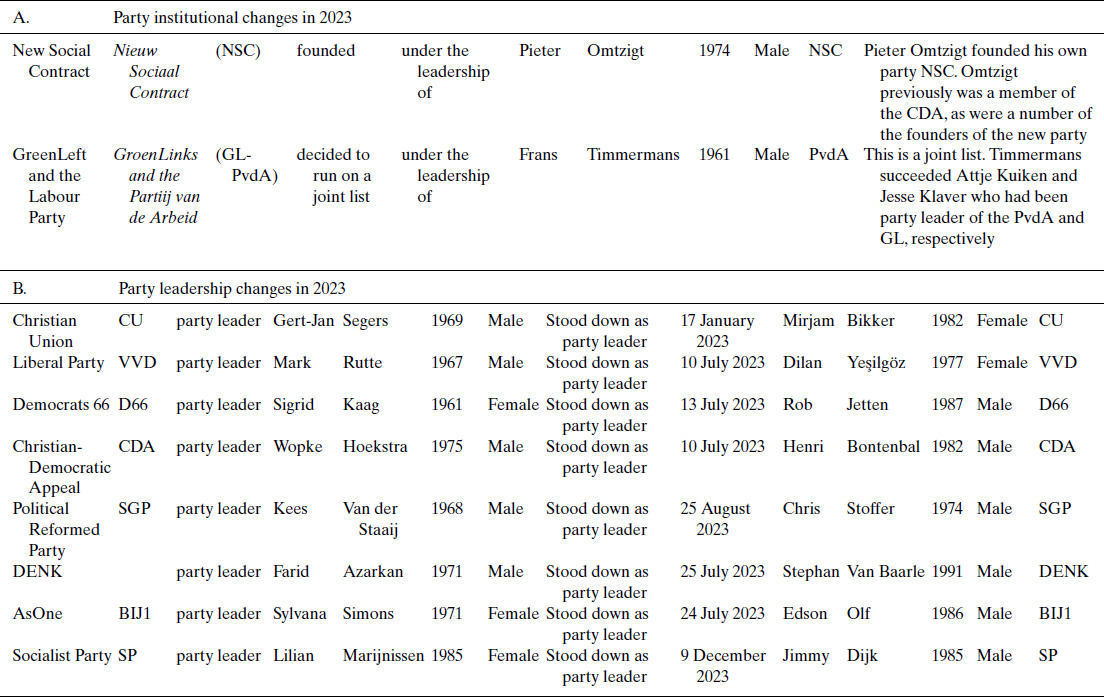

More than half of the parties in Parliament experienced a change in leadership in 2023 (summarized in Table 6). On 25 January, Gert Jan Segers, the leader of the CU stepped down. He was succeeded by Mirjam Bikker, making her the first female leader of the party. Segers made this decision well ahead of the next election to provide his successor with the necessary time and space to establish her leadership.

Table 6. Changes in political parties in the Netherlands in 2023

Source: PDC (2023).

In the week following the fall of the Rutte-IV Cabinet, the leaders of three of the four coalition parties—PM Mark Rutte (VVD), Vice-PM and Finance Minister Sigrid Kaag (D66) and Vice-PM and Foreign Minister Wopke Hoekstra (CDA)—all announced that they would not seek reelection. Other ministers also announced their intention to leave politics after the next election, including the third Vice-PM and Minister of Poverty Policy, Participation and Pensions, Carola Schouten (CU).

In the meantime, the PvdA and GL held separate internal referendums about a joint list for the upcoming elections. On 17 July, the two parties announced the results in a common meeting: 92 per cent of the GL members voted in favor, while 88 per cent of the PvdA members expressed their support. In both referendums, the turnout exceeded 50 per cent. As mentioned earlier, the decision to form a joint list marked the most intensive form of progressive cooperation in the Netherlands in decades. The boards of both parties endorsed Frans Timmermans as the lead candidate for the combined list, which was supported by 92 per cent of the members of both parties in a joint referendum.

On 19 August, Pieter Omzigt launched his new party NSC (see Election Report). Over the course of the summer, many parties saw changes in leadership:

-

• On 13 July, the sitting Minister of Justice and Safety, Dilan Yeşilgöz, was selected by the party board of the VVD as lead candidate.

-

• On 12 August, Rob Jetten, the sitting Minister of Climate Policy and Energy, was elected by the members of D66 with an overwhelming 93 per cent of the votes.

-

• On 14 August, Henri Bontenbal, an MP with only two years of experience, was selected as leader of the CDA by the party board. He also assumed leadership of the party's PPG.

-

• On 28 August, Chris Stoffer, a sitting MP, was chosen by the party board to succeed Kees van der Staaij as the leader of the SGP. Van der Staaij had been an MP since 1998, which made him the longest-serving MP in the Dutch Parliament from 2017 until 2023. Stoffer also took over as leader of the party's PPG.

-

• On 10 September, Stephan van Baarle, who had been MP for only two years, was chosen by the DENK party board to succeed Farid Azarkan. He also assumed leadership of the party's PPG.

-

• On 16 September, Edson Olf, the party vice-chair of BIJ1, was selected by the party's board to succeed Sylvana Simons, who had announced her resignation in July following a period of internal dissension.

In this period of change, the Party for the Animals stood out as one of the few parties that did not change its leader. However, a few weeks before the party congress, the board announced that they would not nominate Ouwehand as leader due to integrity violations. Despite this move, Ouwehand persisted with her candidature, which ultimately caused the board to step down and Ouwehand being selected by the party congress.

On 1 September, the BBB presented its candidates for the elections. Among them were Mona Keijzer, a former junior Minister of Economic Affairs and Climate, who would also become the party's candidate for PM. Additionally, sitting MPs from other far-right parties, including Nicki Pouw-Verweij (JA21), Derk Jan Eppink (JA21), and Lilian Helder (PVV), left their respective parties to join the BBB PPG.

On 9 December, just days after the installation of the new house, Lilian Marijnissen, the leader of the SP, announced that she would step down following the defeat of her party. She had been the leader since 2017, but under her leadership, her party lost votes in every election. On 13 December, she was succeeded by Jimmy Dijk, who had been MP for two years.

Institutional change report

On 14 February, the lower house adopted a constitutional revision in its first reading to introduce a corrective referendum by popular initiative. This amendment was introduced immediately after the previous revision had been rejected in the second reading the year before (Otjes & De Jonge Reference Otjes and de Jonge2023). On 3 October, the amendment passed through the upper house with two-thirds majority.

Issues in national politics

The cabinet faced two major challenges during this period: migration (which is discussed in the Cabinet Report), and nitrogen policy. Nitrogen had been an unresolved and persistently controversial issue in Dutch politics since 2019. The Netherlands has a substantial livestock sector, generating considerable nitrogen pollution that directly affects the quality of the natural environment. To comply with EU environmental regulations, the government had to reduce nitrogen emissions. This matter was a major issue in the 2023 provincial elections. In these provincial elections, the CDA, which had traditionally championed farmers’ interests but lost a considerable number of votes to the BBB, announced its intention to renegotiate the paragraph in the coalition agreement on nitrogen. Of particular concern was the deadline for halving nitrogen pollution by 2030. The announcement of the CDA was aimed at future renegotiation; the party had hoped that after the provincial coalition agreements had been reached and once a comprehensive agricultural agreement was reached with farmers’ organizations, the food industry, nature organizations, and provinces, the cabinet would be confronted by a fait accompli. However, on 21 June, negotiations regarding a comprehensive agricultural agreement failed, placing the responsibility back on the cabinet to address the nitrogen issue.

While issues such as the cost of living as well as the wars in Ukraine and Gaza were certainly discussed in the political arena, they remained secondary at best.