Introduction

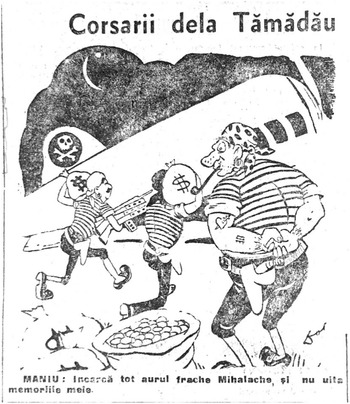

Consider two moments in the early Cold War: Communist takeover of the Romanian state. First, we can look, in the spring of 1945, at an angry eruption in the Romanian cabinet. Nicolae Radescu, the last non-Communist-affiliated prime minister of Romania (until the fall of the Berlin Wall), lambasts the Communist-led National Democratic Front for putting on “an extraordinary spectacle unseen in any other country of the world” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 146/1945 f113).Footnote 1 “In this time,” he fulminates, “I’ve been nothing but a fascist, nazi, pro-fascist and probably tomorrow I’ll become a war criminal” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 146/1945 f113). Not even three years later, this would come to fruition, with the Communists putting their rivals on trial for treason and national betrayal. The second moment is, in fact, a political cartoon (Figure 1) from the lead-up to the trial. In it, the most prominent non-Communist Romanian politician is portrayed, alongside his deputy, as Nazi soldiers threatening the Soviet Union.

Figure 1. Political cartoon after the Tamadau setup of the National Peasants Party. The caption reads: “Romania is a sharp blade pointing against the Soviet Union’ Iuliu Maniu was saying in 1930.”

As a symbolic process, regime change presents particular problems because of an inherent need to not just accrue power (as in the case of state building, e.g., Gorski Reference Gorski2003, Loveman Reference Loveman2005, Reed Reference Reed2019, Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz1999, Torpey Reference Torpey2000) but also delegitimate and diminish that of others, repurposing institutional mechanisms for authority rather than constructing new ones. These two moments, in the flow of events that ultimately established Communist-led Romania as a regularity over the next forty-five years, underscore the temporal and spatial underpinnings of the state, understandings that must be validated in (and into) the present (Abbott Reference Abbott2001, Reference Abbott2016; Glaeser Reference Glaeser2005, Reference Glaeser2011). To justify their regime change, Romanian communists worked to elaborate new historical and contextual understandings of the state, engineering a turning point that effectively established a new version of the Romanian state.

In the first moment, Prime Minister Radescu was therefore reacting furiously to a recasting of the past, one where during World War Two he was a fascist. And this new understanding of the past, which the Communists were working to encode into the present, was being experienced by Radescu as a loss of power: an inscrutable, topsy-turvy future where reactions no longer follow predictably from action (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2011), a tomorrow where he could even “become a war criminal” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 146/1945 f113).

Inherent in these Communist narratives was also a new imaginary of space, which, in fact, underpinned their re-elaboration of the past. If the Soviet Union was friend rather than foe, then past or present action against the USSR could be recast as a betrayal of Romanian national interests. The political cartoon in Figure 1 was published by the Communist mouthpiece newspaper in the run-up to a 1947 show trial that would concretize their takeover of the state, yet it was referencing a statement from 1930, where the anti-Communist leader was envisioning Romania as “a sharp blade pointing against the Soviet Union.”

Taken together, the Romanian regime change at the beginning of the Cold War shows, first, that regime change can be just as symbolic as state building, involving reimagined understandings of time and space. Second, it underscores the importance of a processual approach to the state as a regularity that needs to be validated – but can also be unvalidated (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2011). To the extent that this shift from old to new understandings is difficult to engender – whereby simply failing to validate old understandings is not deemed enough to effectuate regime change – we see that process has sticky, path-dependent qualities. Regime change, particularly in its symbolic aspects, involves not only the breakdown of spatial and temporal understandings of the state but also the concurrent validation of alternatives.

State building and regime change after the cultural turn

Moving away from structural accounts of state formation, which focus on resources and rational actors, more recent research also looks to the “remolding of subjectivities into docile state actors” (Reed Reference Reed2019: 4; see also Gorski Reference Gorski2003; Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz1999; Torpey Reference Torpey2000). Put differently, state building is not only structural but also symbolic. For instance, Loveman (Reference Loveman2005: 1652) argues that more structural accounts “fail to recognize explicitly that the state’s capacity to carry out its ideological, economic, political, and military functions hinges in crucial respects on the exercise of symbolic power.” She thus shows that “[e]ven the most material aspects of modern state formation have a cultural dimension…” (Loveman Reference Loveman2005: 1652), elaborating a model of state building precisely as the accumulation of symbolic power by modern and modernizing states. Whether the state is a result of religion (Gorski Reference Gorski2003) or nationalism (Pincus Reference Pincus, Steinmetz and Ithaca1999), we see it come into being not only structurally but also culturally.

In his work on the early American republic, Reed (Reference Reed2019) builds on Loveman to argue that state formation requires a public performance. He finds that agents looking to build or consolidate a new state do so by making some of their acts public and visible, including acts of violence or negotiations with other elite contenders for power. In other words, performances allow contenders to bootstrap new states into reality, what Reed (Reference Reed2019: 2) calls becoming a “state by demonstration.” Performativity, in this model, acts as a means of solving the agency problems inherent in creating the state, a bet that actors seeing the performance will invest in the state becoming successful, and thus make it successful in reality.

This view of state building as performative also mirrors Pierre Bourdieu’s lesser-known work on the state (see also Gorski Reference Gorski2013; Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz, Medvetz and Sallaz2018; Calhoun Reference Calhoun and Gorski2013). There, he argues that because the state is an “illusion” (Reference Bourdieu2014: 10) and a “legal fiction” (Reference Bourdieu2014: 25), it is inherently performative, and through the performance, it constitutes itself (see also Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu, Steinmetz and Ithaca1999). This view of the state as performance is brought together, by Bourdieu, with the state as the source of symbolic power: even when a performance of state power is ignored or contested, “the symbolic has real effect” (Reference Bourdieu2014: 28). Bourdieu thus emphasized how moments of contestation such as state building are marked by struggles around the monopoly over legitimate symbolic violence, when anyone could take over this monopoly, and by extension the state. He argued that in such moments, an actor must reconcile the group to which they belong with its “official truth” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu2014: 30).

Though less developed, research has also tracked the role of the symbolic when turning to regime change. Charles Tilly engaged with democratization in some of his later works – and remains, indeed, one of the few sociologists to have done so. Tilly (Reference Tilly2003, Reference Tilly2004, Reference Tilly2005), in contrast to most of the literature on democratization, explicitly made space for and theorized democracy across a multidimensional spectrum of outcomes, meaning that democracy was far from the end goal of his models. Tilly followed Moore (Reference Moore1966) in linking struggle and contention to political outcomes, whether democracy or not. But Tilly also denied the possibility of some sort of law-like pattern of regime change. His multifaceted model instead elaborates a view of contention that is more openly cultural and symbolic compared to his earlier, classic work (Emirbayer Reference Emirbayer2010; Zelizer Reference Zelizer2010), looking to how culture is deployed and transformed during – and through – regime change. While still fundamentally social-structural (Brubaker Reference Brubaker2010; Emirbayer Reference Emirbayer2010), this work importantly elaborated political contention as “claim-making performances” (Tilly Reference Tilly2004: 8; see also Tilly Reference Tilly2008). It therefore marks a departure from Moore’s especially structural, Marxian take on revolution: by linking democratization to a strong bourgeoisie, Moore (Reference Moore1966) missed out on the symbolic and discursive elements of regime change, aspects that were important, including during the American civil war, as De Leon (Reference De Leon, Adams, Bingley and Group2008) points out (see also Riley Reference Riley2019).

Since state building and regime change share important similarities in form, the cultural turn’s insights can also be brought to bear on processes of regime change. Both are political transitions; indeed, state building is sometimes conceptualized as a continual process rather than a one-off moment of creation (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz1999). And while state building creates new institutional mechanisms rather than repurposing them, the monopolization of violence nonetheless involves other actors’ loss of autonomous control over legitimate violence.Footnote 2 Taken together, Tilly and colleagues’ work on regime change, read through the prism of research on symbolic state building (Reed Reference Reed2019; Loveman Reference Loveman2005; Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu2014), would suggest that regime change also has important symbolic dimensions.

There is one important difference, however. Regime change is explicitly and necessarily a matter of destroying the old in order to create (and legitimate) the new. New institutional forms of authority are not necessarily being built (e.g., Reed Reference Reed2019), so much as changing hands (Walzer Reference Walzer1992). And while with state building in its cultural turn, we understand how actors accrue legitimacy, we pay less attention to how they may forcibly lose it.Footnote 3 But, of course, this loss of legitimacy whereby authority is assumed by new political actors is a crucial part of regime change (Tilly Reference Tilly2004; Reference Tilly2005). Regime change is thus marked by both the accrual of legitimacy for the actors who eventually take control of the state and a loss of legitimacy for those losing control of the state.Footnote 4

Understandings of time and space, or toward a processual conceptualization of the state

To better conceptualize this shift in the balance of power, I propose that symbolic regime change can be conceptualized with reference to both space and time. This is predicated on a processual conceptualization of the state (Abbott Reference Abbott2001, Reference Abbott2016; Glaeser Reference Glaeser2005). As a regularity that needs to be constantly validated (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2011), a state therefore enacts a particular history, which is encoded into the present. And it does so within a particular space. Neither of these aspects is fixed, however, and therein lies the crux of the argument. History and memory are constructed and reconstructed well after the fact (Alexander Reference Alexander2016; Anderson Reference Anderson2006, Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm, Hobsbawm and Ranger2013, Olick Reference Olick2013, Savelsberg and King Reference Savelsberg and King2011).

Social imaginaries of space are equally mutable. A state, I would argue, needs by definition to populate boundaries (see Abbott Reference Abbott2001: 27 on this idea of boundaries as “site[s] of difference”). Of course, these can be geographic, but they are also symbolic and, in this sense, not strictly tied to geographical contiguity: a state can have points of convergence with friends or allies, as well as protective boundaries against enemies. In turn, either sort of boundary can shift or can be populated differently: lines on a map can and do move, people take borders more or less seriously in their everyday lives, etc. And crucial for the argument here, friends can also become enemies, or vice versa. A state needs to populate boundaries, but the entities or means through which it does so are neither somehow predefined nor fixed. Importantly, this sense of space is not purely ideational: power struggles over the state can and do happen outside of its geographic borders. A state exists and is reproduced transnationally (Go Reference Go2008; Go and Krause Reference Go and Krause2016; Go and Lawson Reference Go and Lawson2017; see also Fourcade Reference Fourcade2006), and this is precisely why the boundaries of the state, even as they are employed in defining the state (e.g., as a geographically limited monopoly over the use of force), are nonetheless highly mutable.Footnote 5

The primary indicator of regime change is a shift in the political actors who have power, which is understood, following Glaeser (Reference Glaeser2011: 51), as “the ability to make reactions follow actions in a predictable way.”Footnote 6 This need not be, by definition, symbolic: regime change could be achieved through guns and tanks rather than speeches and performances. The symbolic aspects of regime change come into play where one or both understandings of the state – space and time, contextual and historical – shift in a meaningful way, as preexisting understandings cease to be validated, while new ones take hold. (In the discussion, I come back to how this formulation modifies existing work on process.) Inasmuch as these understandings shape and are shaped by which actors have political power, this symbolic aspect of regime change can, of course, be coincident with – though not indistinguishable from – regime change understood instrumentally as a change in who is in charge.

And while mechanisms of legitimacy and consent are fundamentally different in autocracies and democracies, they are nonetheless at play in both regime types. Bartel (Reference Bartel2022), for instance, thinks through the end of the Cold War in terms of an increasingly difficult global economic context that led regimes in East and West to break promises of good wages and stable jobs. He argues that the breakdown of the Eastern bloc rested in communist countries’ inability to propagate ideology that could excuse the broken promises, while the West was able to do so through neoliberalism. Importantly, Bartel (Reference Bartel2022) shows how communist governments in Europe spent the 1970s and 80s attempting to keep their promises with both growing desperation and increasing futility (see also Hilmar Reference Hilmar2023). Put differently, while autocracies might have more leeway for politically difficult action, this leeway is far from unlimited. And while their control might seem immense, it is certainly not felt as such by domestic political elites. Indeed, spaces for resistance can emerge in the mundane and everyday; for instance, Serban (Reference Serban2019) shows that in early Communist Romania, law was simultaneously a space for both state power and resistance to the state (see also Şerban Reference Şerban2020). As I therefore show here, symbolic re-validation was felt as necessary to underpin the instrumental regime change in who was in charge.

The regime change that took place in Romania at the beginning of the Cold War thus involved re-elaborations of both space and time: at the same time that social imaginaries of enemies and friends were shifting, so too did history, redefining who was a hero and who was a traitor. In turn, this reversal was both rooted in and had implications for who had power, understood as a temporal, future-oriented phenomenon whereby reactions would predictably follow actions (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2011).

In what follows, I elaborate on this further, drawing on archival research using documents held both at the Romanian National Archives (cited in the text in Romanian, as “Arhivele Nationale”) and at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), as well as newspapers from the era, both Romanian and from abroad (more details on the specific documents that were used are available in the “Methodological Appendix” under Supplementary material).

Drawing on these sources, I elaborate different rhetorical and institutional aspects of the broad-based process to un- and re-validate the Romanian state. Put differently, a multiplicity of reinforcing understandings is involved in validating the state (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2011). This multiplicity would therefore need to be re-elaborated and re-calibrated – by necessity in fits and starts – toward the unvalidation of the pre-Communist Romanian state.

Relying on documents from the Romanian National Archives, I show how this played out in meetings of both the Romanian Communist Party and its allies, as well as in Cabinet debates. The Romanian National Archives also include propaganda materials that were deployed by the Communists and their political allies at this time. I then shift focus to a 1946 election won through massive electoral fraud: I show how Scanteia, the Communist newspaper mouthpiece, framed these events, and contrast this to internal Cabinet debates that took place around this time. Finally, the story moves on to the show trial that culminated in Communist control over the Romanian state. Institutional details of how this played out come from both the Romanian National Archives and USHMM archives, while propaganda and commentary on the trials come from newspapers in Romania and abroad.

Post-World War Two regime change in Romania: The structural Communist advantage

Romania entered World War II relatively late, almost a year after the start of hostilities, on the side of the Axis powers. This was, more than anything else, a product of geography. Whether it was an Axis attack on Russia or Soviet troops heading to Western Europe, either option meant an overrun Romania. Earlier that year, the country had lost two regions to Soviet control, and was also forced by the Axis powers to cede a part of Transylvania to Hungary. Thus, with the Nazi attack on the USSR in the planning stages, the newly installed Romanian leader, Ion Antonescu, committed Romania to the Axis on November 23, 1940. Romania became a core staging ground for the Nazi attack on the Soviet Union, contributing both troops and, crucially, petrol, to the German attack.

Defeats on the Eastern Front soon changed the Romanian stance on the war. The Battle of Stalingrad, in particular, wiped out half of Romanian forces and led to a deepening economic crisis in the country. Despite attempts at an armistice with the Allies, Antonescu remained committed to the Axis. He was thus removed from power on August 23r, 1944, in a coup organized by the Romanian king (previously, under Antonescu, a titular figurehead with little power) alongside a coalition of Romanian political parties. These parties, calling themselves the National Democratic Block, placed a military, technocrat government in power, appointing General (and Deputy Chief of the General Staff) Constantin Sanatescu as prime minister. The new government removed Romania from the Axis and switched sides to the Allies.

This article focuses on this transition process that began on August 23, 1944, culminating in communist control over Romania. This, of course, was part of a wider communist takeover of Eastern Europe, one notable for setting off the Cold War, and entrenching autocratic regimes that would rule the Eastern Bloc until 1989. In 1944, however, the Berlin Wall was almost 20 years away from being built, and Communist control of Eastern Europe was just beginning. It was therefore a moment where the future still felt open (Sendroiu Reference Sendroiu2022).

There were four parties involved in the National Democratic Block that took over on August 23, 1944: the Romanian Socialist Party, the Romanian Communist Party (or in the Romanian acronym, the PCR), the National Peasants Party (PNT), and the National Liberal Party (PNL). Of these parties, the first two had, previous to the coup, been relatively unknown political actors. In particular, the Romanian Communist Party had fewer than 1,000 members in 1944, many of them not ethnic RomaniansFootnote 7 (Boia Reference Bartel2016). It had been declared illegal in 1924, three years after being founded, meaning adherents were either imprisoned or took refuge in the USSR. But growing Soviet dominance would soon change the Communists’ outlook.

The leaders of the latter two parties forming the government, Peasants and Liberals, had run the country in a relatively unbroken line since 1875, and so prior to the war, the political force and popularity rested with them. It was, in fact, a Liberal government that declared the Communists illegal in 1924.Footnote 8 When General Antonescu came to power in 1940, these two parties – commonly known as the historic or traditional parties – were declared illegal. But during and after the coup which removed Antonescu from power, these two parties were generally seen as the future political leaders of the country, and indeed had the most popular support. Nonetheless, new geopolitical considerations – the Red Army’s advance westward – meant they had to bring the Communists into the National Democratic Block, because the Soviets would only negotiate a possible armistice with Communist Party leaders. And so began a period of precipitous, Soviet-backed Communist ascendance.

In late February 1945, the last government dominated by the historic parties, and led by General Nicolae Radescu, was removed from power. This removal had little to do with growing popular support for the Communists.Footnote 9 Instead, the catalyst for the fall of the government was Andrey Vyshinsky, the Soviet deputy foreign minister, traveling to Bucharest and demanding that the king remove Radescu from power, appointing Communist sympathizer Petru Groza to the post (Groza had so far, in the last two short-lived governments, been deputy prime minister). Vishinsky threatened a Soviet takeover of the country if his order was not followed (Frunza Reference Frunza1990; Cioroianu Reference Cioroianu2005). And given this threat of blunt force, with the Soviet army spread throughout the country, and appropriating Romanian military and industrial goods (ships, factories, etc.), the king acquiesced to the Soviet demand.

The removal of the historic parties from governance thus happened largely for structural reasons, brought about by Soviet dominance in Romania. A model of regime change that assumes structural shifts – raw power – to suffice for regime change would assume this, the removal of the historic parties from governance as a result of the Soviets’ preponderant military might, to have been the end of the matter.

But the Communists themselves do not appear to have judged this as enough. They thus allowed – indeed, facilitated – elections in the summer of 1946 where the historic parties were allowed to compete, and which the Communists won through widespread electoral fraud (Giurescu Reference Giurescu2007). And then the elections, a first act in winning the symbolic fight over the country, were also not deemed enough, perhaps because, in truth, they gave far from a clear mandate to the Communists. They were also accompanied by increased attacks on the PCR’s primacy and legitimacy outside of Romania’s borders, including because of the widespread electoral fraud (I return to this in a later section). One year later, to address this threat, the PCR coordinated a setup of their rivals, who were then put on trial. It is this series of events that I describe in what follows, beginning with the emerging narratives of the PCR’s rivals as traitors and fascists.

Emergent narratives of betrayal

The coup in Romania happened at the end of August 1944 and, as previously mentioned, the coalition government that came to power soon after was dominated by the historic parties, the Liberals and the Peasants, at the expense of the Socialists and the Communists. For instance, Peasants’ Party leader Iuliu Maniu had initially been asked to take over as prime minister, and while he refused, the general who was eventually named prime minister deferred to Maniu – and to a lesser extent, Liberal leader Constantin I. C. Bratianu – on all major decisions, acting more as a convener of the cabinet rather than its head. The leftist parties were unhappy with this disparity, and emboldened by growing Soviet presence and influence in the country, they created the National Democratic Front (in Romanian, Frontul National Democratic or FND). It is in, and through, the Front that the Communists and their allies initially elaborated a view of the historic parties as traitors and fascists, with this new understanding of the past making its way to cabinet and the press, and eventually to trial.

While, in what follows, I describe the narratives elaborated by the Communists of their rivals, it is worth pausing to note that these individuals were neither fascists nor war criminals. Recall, in particular, that Antonescu declared the historic parties illegal. While their members were – unlike the Communists – neither imprisoned nor exiled, they were not part of the wartime regime. Moreover, ideologically, neither the Peasants nor the Liberals could be conceived as fascist, with both parties long committed to democratic rule (though with limited suffrage, the Liberals more so than the Peasants). Finally, both parties enjoyed widespread popular support.

This did not prevent the Front from denouncing them as fascists and traitors. This began in subtle form with the Front’s official platform, from October 1944. The third priority advocated by the FND, after a fight “side-by-side with the Red Army” for the complete defeat of Germany and an “honest friendship and strong collaboration with our great neighbor, the Soviet Union” (Arhivele Nationale CC al PCR 49 8/1944), was a “fight for the complete destruction of fascism in Romania, as well as the punishment of all traitors and those guilty of war against the Soviet Union, England, and America” (Arhivele Nationale Frontul National Democrat 2869 8/1944). Notably, the fourteen-page platform does not mention any of the wartime leaders. It does, however, warn that a politics of opposition to the Soviet Union – a politics, we should note, akin to that of the historic parties – is counter to the interests of Romania. From the start, then, threat was intertwined with foreign affairs, with a new imaginary of the international.

While part of coalition governments, the FND itself, including FND cabinet ministers, would also hold internal meetings to discuss policy positions and strategies, and goings-on in cabinet. It is here that we see a turn, by late 1944, to painting opposition to the Front as fascism. For example, in one such instance, a prominent Communist reported that the head of the Peasants Party had convinced the prime minister to not publicize a general meeting of the unions. The Front decided to put the matter to cabinet, and when one minister worried that the prime minister might oppose their desire to publicize, the response was, “[v]ery well, then we know the Prime Minister supports the fascists” (Arhivele Nationale Frontul National Democrat 2869 10/1944 f14).

At the same time, the members of the Front were well aware that the historic parties had broad appeal: at their next meeting, one Front minister reminded his colleagues that they “cannot underestimate the fact that the bourgeois parties still have mass influence” including in factories that have typically been a source of left-wing support (Arhivele Nationale CC al PCR 49 11/1944 f3). But they nonetheless pronounced their faith that eighty to ninety percent of Liberal and Peasants Party adherents could be convinced to abandon “the Maniu myth” (naming here the leader of the Peasants) and join the Front (Arhivele Nationale CC al PCR 49 11/1944 f7). In particular, the way forward to “surely bring them down” from the positions they had won was, according to prominent Communist (and cabinet minister) Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, to “clarify public opinion on today’s problems, showing those guilty of today’s difficulties [are those] involved in past governance and direct and indirect saboteurs” (Arhivele Nationale CC al PCR 49 11/1944 f12). Gheorghiu-Dej, however, did not at the time specify the form to be taken by this public “clarification” of the historic parties’ past faults. But this need for “clarification” would come up again, and become more urgent, as we will see in the next section.

Slowly, the accusations began to concretize. Some weeks later, the first Front meeting of 1945 brought additional details to the charge sheet against the historic parties, a charge sheet also notable for its very existence: here we see the intimation that what the historic parties had done was illegal. When discussing ongoing proceedings to create a law defining who was a war criminal, Front politicians complained that both the Liberals and the Peasants were delaying agreement on the law, and attempting to “soften the definition.” This led to the following exchange:

Comrade Vasile Luca: Why don’t the National-Peasants shut up? Can’t we show that Maniu [NB: Peasants’ leader] approved of the war … that Mihalache [NB: Peasants’ deputy leader] was always friends with Antonescu…? … And Bratianu [NB: Liberal leader] … We can say not 1938, but 1918, because their entire politics went in this direction. What politics did they conduct? Did they even reestablish relations with the Soviet Union?

Petru Groza [NB: deputy Prime Minister]: In the moment when we [Groza’s small, left-wing party] were establishing a pact with the Communists, they were making a non-aggression pact with the [fascist] legionnaires.

Comrade Vasile Luca: So they shouldn’t get stuck in the little things because they’ll burn their own hand. And the time will come when they’ll be implicated…

(Arhivele Nationale Frontul National Democrat 2869 14/1945 f19)

The definition of war crimes, in other words, was open to a wider interpretation beyond individuals actively involved in the war, part of a reinterpretation of the past that went back to 1918 rather than 1938. And this reinterpretation was also transnational or spatial in scope: echoing the Front’s initial focus on foreign affairs, we see here that action against the Soviet Union was quickly coming to be seen not just as counter to Romania’s interests but also as legally indictable.

These understandings – and particularly an expansion of who counts as fascist in relation to how domestic behaviors would be perceived externally – also made their way to the press, with FND propaganda from 1945 making stronger and stronger claims. One pamphlet warns readers that

Today’s government has within it REACTIONARIES, who are backed up by MANIU and his cabal, and that’s why our Allies DON’T trust them! THESE REACTIONARIES ARE AGAINST DEMOCRATIZING THE COUNTRY AND AGAINST THE ROMANIAN PEOPLE! (Arhivele Nationale Frontul National Democrat 2869 53/1945, emphases and formatting in the original).

And when the FND organized anti-government protests which turned violent, the Front (which, it should be noted, was still part of the government) put out a communique characterizing events as follows: “[e]xecutioner Radescu [NB: the Prime Minister], with the direct support of [Peasants leader] Iuliu Maniu and of all those who back legionnairism and fascism in our country, wanted to spill blood throughout the country…” (Arhivele Nationale Frontul National Democrat 2869 53/1945). The communique ends with a simple exhortation: “Death to the fascists!” (Arhivele Nationale Frontul National Democrat 2869 53/1945).

The cabinet, which still included representatives of the Liberal and Peasants’ Parties, took up the Communist propaganda. Prominent Communist Gheorghiu-Dej, recently returned from Moscow, reported at a cabinet meeting on January 18, 1945 that the “government doesn’t enjoy sufficient trust in Moscow,” specifically calling out a New Year’s speech given by Peasants leader Iuliu Maniu which “intervened” like a “bomb” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 143/1945 f9). Peasants politicians serving in cabinet replied that the speech was an attack on the Romanian Communist Party, not on the USSR. The conversation continues as follows:

Popp [Peasant Party minister]: The accusations of fascism and hitlerism are daily. How could anyone, in good faith, bring this sort of accusations to Mr Maniu, when we all collaborate here?

Gheorghiu-Dej [FND/Communist minister]: Why do you ask me? I’m showing you what I found in Russia.

Popp: … I don’t know if we can stay in good relations amongst us if the communist press attacks Mr Maniu daily, who is the personification of our party and with whom we are in complete solidarity.

Groza [FND minister]: A reciprocal compromise.

Lecutia [Peasants Party minister]: With Mr Maniu, we compromise ourselves happily. With him, we also compromised ourselves under Antonescu. We even stayed in work camps.

Gheorghiu-Dej: I’m just telling you what was written in Isvestia [NB: Soviet communist newspaper]. It is not a personal opinion [of mine] (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 143/1945 f13)

The exchange is notable for its belligerence, which precluded meaningful collaboration in cabinet, and for Gheorghiu-Dej’s disavowal of the accusations. Despite the publicity campaign against their rivals, the FND was inconsistent in making its accusations. Importantly, the exchange also highlights the transnational scope of the struggle between the Front and their rivals, whereby political attacks on Romania’s Communists were conflated with attacks on the Soviet Union, with Maniu’s speech felt like a “bomb” in the USSR (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 143/1945 f13). And even Gheorgiu-Dej’s equivocation was transnational, with his attribution of the “accusations of fascism and hitlerism” to the Soviets’ newspaper rather than to the Romanian Communists (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 143/1945 f13).

Yet, for all their inconsistency, the attacks did not end, with the Communists continuing to elaborate a new temporal understanding of Romania. In Prime Minister Radescu’s remarks, which were referenced in the introduction, we see that accusations of fascism had become widespread enough that he was both scornful and exasperated:

All of my wishes [for conciliation with the Front] have been to no avail; instead, the agitations have gotten worse and have reached a maximum point in the past week, creating an extraordinary spectacle unseen in any other country of the world, because ministers who are part of the government, either in the press or personally, should insult the entire government, their colleagues from other parties or even the president of the Council [i.e., the Prime Minister]. It’s something that you’ve been doing permanently for the past ten days. In this time I’ve been nothing but a fascist, nazi, pro-fascist and probably tomorrow I’ll become a war criminal.

You speak of quiet in the country and wish that we do not arrive at disaster. But who provokes the disaster? You and your partisans. Show me an act on my part – or I have the courage to say, even on the part of the other two political parties that make up our government – show me an act that has as a consequence pushing the country toward disaster. (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 146/1945 f113).

This, however, was Radescu’s last cabinet meeting as prime minister. Under Soviet pressure, he was soon removed from the position. And he and his allies were eventually put on trial precisely for treasonously creating the country’s disaster. In particular, the Communists and their rivals were attacking each other with view to what was happening outside Romania, and this would carry over to elections, and eventually to trials.

From the 1946 elections to the Tamadau setup

After Radescu’s removal from power, the new government that was installed was ostensibly not communist but a coalition similar in composition to the other post-coup governments. A Communist did not replace Radescu; instead, a Front politician named Petru Groza became prime minister. Of course, even the Front’s own propaganda materials belie the claim to a broadly representative coalition. In one such poster, we see photos of the new cabinet members against the backdrop of a factory cooperative.

It was this Groza government that prosecuted wartime leader Ion Antonescu and other members of his administration for creating “the country’s disaster” in what they called “the trial of the great treason” (USHMM 2012.56 | RG-25.091M)Footnote 10 (I will return to this in the next section). They were found guilty of all charges and executed. Notably, in these trials, the scope of what counted as treasonous expanded well beyond the Holocaust in Romania to include aggression against the Soviet Union (see also Muraru Reference Muraru2010).

This same Groza government also decided to hold elections in the summer of 1946, engaging with Soviet backing in widespread electoral fraud (Giurescu Reference Giurescu2007). While Scanteia (III 685: 1)Footnote 11, the Communist Party newspaper, celebrated the “Romanian people’s vote for democracy,” the results were far from democratic, with modern counts suggesting that the Liberal and Peasants Parties had more than enough votes to form a majority in parliament (Giurescu Reference Giurescu2007).

Two days after the elections, the new cabinet held a meeting notable for how little those present made mention of the elections.Footnote 12 Instead, they discussed a problem they were facing in the post-war peace negotiations happening in Paris. This, in the words of the newly re-elected prime minister, was the “attitude of some citizens of [Romania] … which they have assumed abroad, and which makes clear that they no longer care for this country … [and who] beyond the borders of this country develop, especially in Paris, in competition with the Delegation of the Romanian Government, a subversive and evil activity” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 9/1946 f82).

The other ministers had questions about these “delinquents” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 9/1946 f83). Asked if other countries also experienced such challenges, one member of the delegation answered with an unequivocal “no!” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 9/1946 f84). Gheorgiu-Dej, a prominent Communist who had traveled to Paris, picked up the story: “[h]aving arrived in Paris … we learned that there is a so-called resistance group, who apparently put forward a memorandum regarding Romania’s rights before the Peace Conference, justifying that they represent four-fifths of the population” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 9/1946 f84). The results of the election – or rather of the widespread electoral fraud that had begun since the campaign period – quickly made it to Paris. But Gheorgiu-Dej reassured his colleagues that “[b]esides the influence they could have given these relationships, [the resistance group] could have no damaging influence on the activities of our delegation” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 9/1946 f84-5).

It should be noted, however, that the West was indeed reacting against the fraudulent 1946 elections. The US and the UK complained formally in June and October of 1946, with Groza rejecting both complaints on grounds that they violated Romanian sovereignty and, moreover, that Russia had not complained about the elections. (Indeed, Moscow hailed the election as a “victory for Romanian democracy,” arguing that the result “showed the unanimous approval of the foreign policy of Premier Petru Groza’s government” (Cumberland Evening Times 1946). This had numerous reverberations within Romania. The US military mission was picketed in November. And the Communists censored a speech given at Paris by UK Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, omitting one crucial sentence: “[m]ay I say here that it is our desire that the Rumanian people, in accordance with Moscow’s decision, should be free and unfettered to effect a government representative of their true national aspirations, and that Rumania should come back to take her true place in the company of the United Nations” (New York Times 1946).

At the post-election cabinet meeting, Gheorghiu-Dej therefore highlighted the “importance of their political action abroad which constitutes defamation against the Romanian State and our regime …” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 9/1946 f85). And the “defamation” elaborated by the “delinquents” was all the more important for having domestic sponsors. Gheorghiu-Dej thus informed his colleagues that “[t]his resistance group, according to our information, has links to certain domestic elements.” As a result, he continued, “we find before us organized and coordinated action and so our State organs will eventually need to take care of this situation …” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 9/1946 f85).

The prominent communist, who would go on to be the first Communist leader of Romania, proposed two elements to addressing the “situation.” The first involved legality, “bring[ing] up this question before the Council of Ministers so as to advise upon penal measures that can be taken against these criminal elements” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 9/1946 f83). The second element to the solution echoed his desire, seen as far back as meetings of the Front from 1944, to “clarify public opinion.” Thus, the second important element to dealing with the threat abroad was, for Gheorghiu-Dej, “to also inform our public opinion upon their actions, and show that they have damaged the Romanian State both politically and morally” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 9/1946 f87).

After heated discussions denouncing the “delinquents,” the prime minister spoke at length to thank the members of the delegation. Their success was especially evident, he argued, because they managed to “diminish the atmosphere around us which was artificially created by a group of people who represent the resistance abroad” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 9/1946 f103). And so he closed by insisting: “[W]e must ask ourselves: who does [resistance member] Mr. Gafencu represent in Paris? Why must we hide?!” The answer was provided by another Communist minister: “[h]e represents Badacin” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 9/1946 f103). Badacin, as would have been clear to all present, was the location of the family home of Peasants leader Iuliu Maniu.

The cabinet eventually followed through with Gheorghiu-Dej’s two-pronged plan. A year later, the government offered the Peasants’ leadership the opportunity to leave the country. But in what came to be known as the setup of Tamadau, they arrived at the airport in Tamadau and were arrested.

‘Traitors’ on trial: a performance with transnational scope

Tamadau had, from the start, a transnational scope. What was indictable was precisely contact with foreign agents, or at least the wrong sort of foreign agents. In the cabinet meeting where their removal of parliamentary immunity was discussed, the internal affairs minister informed his colleagues that those attempting to leave the country “were planning to accomplish the decisions and directives of the leadership of the National Peasants Party, beginning with Iuliu Maniu, surrounding actions meant to diminish national sovereignty, damage the peace, and start civil war” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 7/1947 f108). Moreover, such “anti-national” actions fit with “the political line always followed by the National Peasants Party and intensified after [the coup on] August 23 1944” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 7/1947 f108). And the interior affairs minister’s speech continued at length, noting that during the 1946 election, the Peasants had attempted to “bewitch the population with propaganda of a fascist, racial hatred and anti-Soviet type…” (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 7/1947 f109). After the election, meanwhile, the minister focused not on the PNT’s supposed involvement in the Paris peace negotiations, but rather argued that the Peasants leadership “directly and through its agents abroad … with the support of reactionary foreign circles, intervened with the goal of stopping the provision of grains …” for a Romanian population facing widespread food shortages (Arhivele Nationale PCM 2336 7/1947 f109). Through Tamadau, we thus begin to see the PNT’s actions abroad made concrete, and elaborated as damaging not only to the regime but to Romania as a whole. We see, in other words, a further validation of Romania understood spatially as under threat from the West, and closely befriended by the USSR.

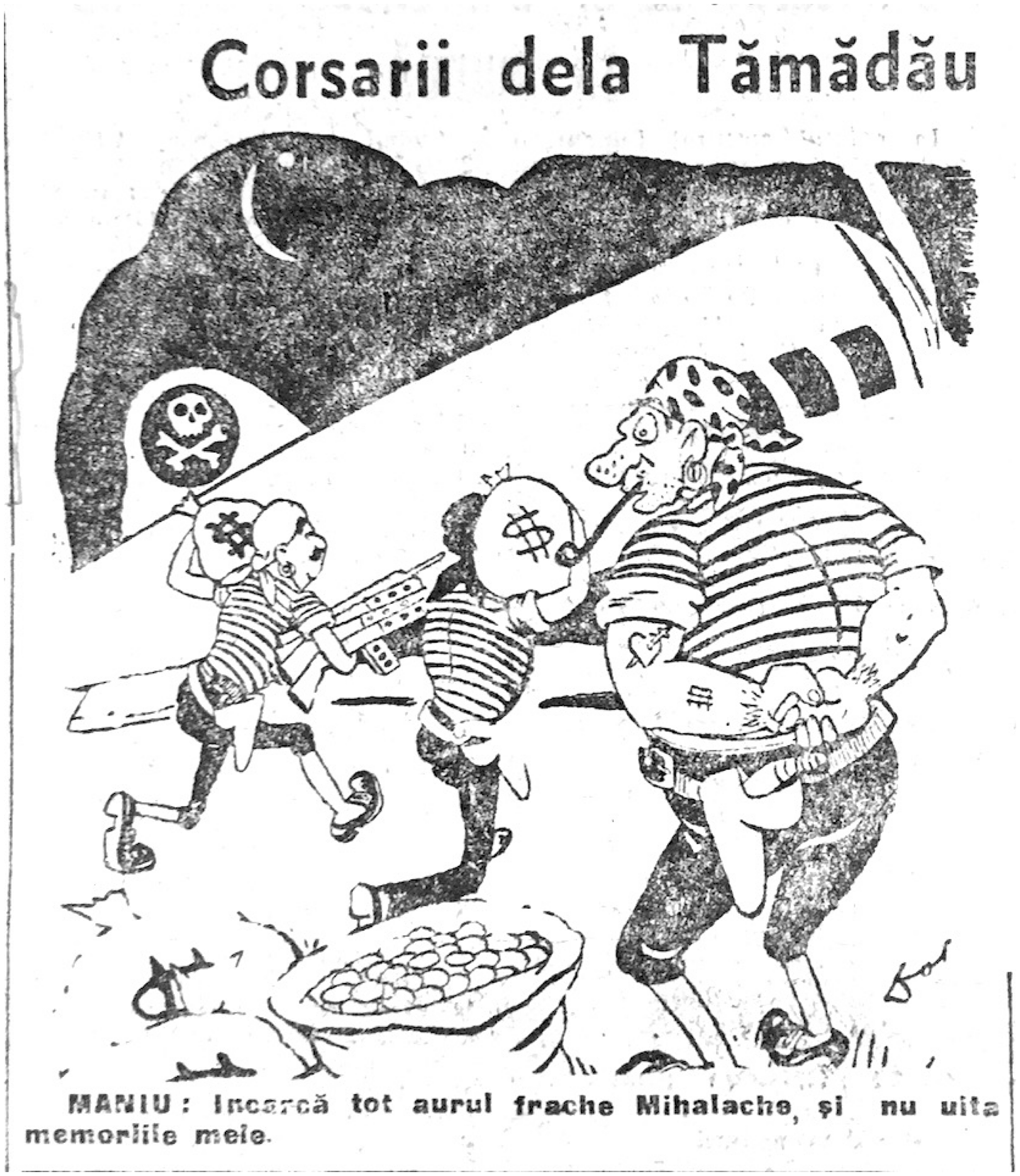

The Tamadau affair was broadly publicized in Romanian media, especially in Scanteia, the PCR’s official newspaper and, at the time, a main source of news in the country. Tamadau was therefore front-page news in Scanteia, a photo of those attempting to flee below an unequivocal headline: “Sold to the foreigners, they wanted to head abroad” (Scanteia III 872: 1). Tamadau was also reproduced in political cartoons. In one, we can see pirates attempting to fly away with looted treasure (Figure 2). Even to a predominantly internal audience, Tamadau was thus shown as a transnational matter, of “attempting to sell the country” abroad (Scanteia III 873: 1).

Figure 2. Political cartoon with the heading “The Pirates of Tamadau.” The caption reads: “MANIU: Load all the gold, brother Mihalache [NB: Peasants deputy leader], and don’t forget my memoirs.”

Particularly damaging, as in the past, was collaborating with “bad” external actors, and the threatening of “good” external actors. Through Tamadau and what followed, we thus see narratives of fascism came to fruition, together with a continued accusation of actively fighting against and undermining the Soviet Union, both of which also lent themselves to painting the communists’ opponents with the same brush as Romania’s World War Two leaders, who had been tried for these very crimes. We see both these narratives in the political cartoon of Maniu from the lead-up to the trial, also discussed in the introduction (Figure 1), where he and his deputy are depicted as Nazi soldiers threatening the USSR.

A few months after Tamadau, the PNT leaders were put on trial, but not for illegally attempting to leave the country, which only carried a sentence of three to six months. Instead, on October 29, 1947, PNT leaders were indicted as “guilty of plotting against the State and treason” (USHMM 2012.56 | RG-25.091M). Eight Peasants leaders were arrested, including Maniu, and tried in a group trial.

They were put on trial for the PNT’s entire political activity – well beyond the supposed scope of the trial itself – but aligned with the politically motivated need to validate a new understanding of Romanian history. The prosecution thus argued that after the August 23 coup, Maniu backed and sustained all of the country’s “fascists and reactionaries” alongside “traitors” and “agents of imperialism” (USHMM 2012.56 | RG-25.091M). And this continued, and intensified in transnational scope, after being removed from government in March 1945: “Maniu’s party … transforming into an organized conspiracy of spies and plotters who with direct support from imperial circles of some foreign states — were preparing the forceful overthrow of the democratic regime of Romania” (USHMM 2012.56 | RG-25.091M). And the betrayal was broader, and longstanding: “The traitorous and criminal action of accused Maniu … is simply a crowning moment of national betrayal that characterizes the entire political activity of the National-Peasant Party” (USHMM 2012.56 | RG-25.091M).

The regime also closely controlled the media during the trial. In addition to reproducing many of the trial proceedings, Scanteia also published extensive color commentary, one focused both domestically and internationally. On the first day of the trial, readers were told that “[w]ithout hearing a word, no murmur, you can still feel how the room is boiling with indignation. The sober and detailed indictment of the prosecution … sets off a huge anxiety in the audience.” What makes this anxiety particularly evident for Scanteia? “Even some foreign correspondents are troubled” (Scanteia III 962: 1). Indeed, the government kept close track of the foreign correspondents, including who was in the country and the addresses where each journalist resided (Arhivele Nationale PCM 3039).

They were also particularly preoccupied with responding to international news. For instance, the day before the trial, front-page news was an attempt to link Maniu to wartime leader Antonescu, describing meetings between the two as “a conspiracy to support the war” against the Allies (Scanteia III 960: 1). The article seems to be a response to Western news reporting on Maniu: “he Anglo-American business interests’ press, after they saw the collapse of the ‘Western fiction’ of Iuliu Maniu and his acolytes’ popularity, seeks to console its readers with the idea that Maniu was nonetheless a resistance [fighter]” (Scanteia III 960: 1). The article thus seeks to “disabuse” the Western press of these notions, by showing that rather than resistance to fascism during the war, Maniu was “resisting against the people and the country” (Scanteia III 960: 5).

But domestic support of the proceedings also mattered. During the trial, Scanteia detailed how “[h]undreds of thousands of workers, peasants, and soldiers ask for an exemplary punishment for the Maniu traitors” (e.g., Scanteia III 967: 7). The newspaper reported on such demands extensively, and even published letters and telegrams to this effect.

And the “muscovite telenovela,” as the trial was described later (Ungureanu Reference Ungureanu2010), came to its predetermined end by sentencing all accused to many years of hard labor. The seventy-five-year-old Maniu, for instance, was sentenced on nine counts to a total of 104 years in prison, including forced labor for life on two occasions. But Scanteia took the opportunity to have the last word: on the day of sentencing, the headline on the first page, below the details of each person’s sentence, and right next to a report of the country’s agricultural prowess, insists that Maniu’s was “[n]ot a political trial but a trial of betrayal and of espionage.”

Discussion: Unvalidation as a project, toward a sticky, path-dependent processualism

A different way to think through the empirical puzzle at the core of this article is: Why bother? In processual terms, the puzzle is the following: having already consolidated control over the state apparatus, the Communists were gradually cutting off any means through which their opponents could validate their competing claim to the state. So why bother going further, beyond this gradual tapering off of validation, to actively delegitimate the historic parties, and concurrently elaborate new understandings of the state? The answer, I would argue, rests in the extent to which old understandings of the state are sticky or path-dependent. In such a case, a failure to validate old understandings is necessary, but not always sufficient.

In making this claim, my intent is not to return to a static understanding of institutionsFootnote 13 that reifies (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2011: 54) or can only theorize institutional change with reference to exogenous shocks (Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010). And indeed, the processual account of the state elaborated above, made up of shifting understandings of both time and space, builds on the view that “there is nothing automatic … about institutional arrangements” (Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney and Thelen2010: 8). The Romanian communists actively re-elaborated the state in space and time, deploying new understandings of Romania’s history and its international affairs.

Yet the extent to which they went to delegitimate their rivals – between removing them from political life, to stealing elections, to organizing a setup and show trial – suggests that there can be considerable stickiness or drag to old understandings. Indeed, Glaeser (Reference Glaeser2011: 23) acknowledges this as well: “[a]lthough events may suggest a restructuring of understandings in progress, these suggestions do not necessarily crowd out existing understandings. Instead, the process of transformation is typically more gradual; neither are older understandings given up straight away, nor are newer differentiations and integrations transpiring from events accepted instantaneously.” And in his account of political epistemics, this is particularly the case for institutions, which cannot be shifted at will and require the participation of others. Politics, in this account, is at least in part a matter of altering institutions. However, I would argue that this does not always imply that “understandings need to be continuously validated” (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2011: 53, emphasis added). The Romanian communists were fighting against sticky understandings that required real effort to shift.

Unvalidation, in this case, is a deliberate political project – rather than, as in the fall of East Germany, “a disenchantment with old understandings” (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2011: 199). My point, then, is that focusing on continuous validation shifts our attention away from the stickiness of institutions (a stickiness which, indeed, is likely why we tend to reify institutions in the first place). This stickiness applies with reference to both time and space. Thus, Olick (Reference Olick1999; Reference Olick2005) builds on presentist conceptualizations of memory to show that memory is path-dependent, built iteratively through dialogic connections between present and past. Along similar lines, the symbolic and physical boundaries of a state will also be difficult to shift, especially when these are experienced kinesthetically (i.e., border checkpoints, lines on maps, visas and passports, etc).

Indeed, a sticky or path-dependent processualism can already be found in the sociology of understanding (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2011): the seeming stability of institutions rests on the path dependence emerging from feedback loops among different sorts of validations (or the inherent conservatism of each type of validationFootnote 14). By elaborating this sticky version of process, I am simply drawing attention to the instances when this path dependence can be difficult to shift. Validation, in this sense, can be fast or slow, easy or difficult – and it happens in fits and starts. Otherwise, our conceptualizations of deliberate structural change would render it much easier than it is in fact.

Conclusion

Looking at the Romanian transition to communism at the beginning of the Cold War, I elaborate an idea of the state as a regularity that needs to be validated in space and time. In its symbolic respects, regime change, I argue, rests not only in old understandings ceasing to be validated – but also deliberately unvalidated as part of political projects to accrue power. Therefore, while process thinking has been powerfully used to elaborate the end of the Cold War (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2011), here I suggest an idea of process as occasionally sticky or path-dependent, such that a lack of validation is not always enough to shift old understandings.

In the Discussion, I asked “Why bother?” Why would the Romanian communists invest energy in delegitimizing other understandings of the Romanian state when they could just wait out a gradual tapering off of their opponents’ ability to validate their competing claim to the state? The answer I provide there is at the conceptual core of the article – namely, that both spatial and temporal understandings of the state are sticky. This holds even when taking into account the autocratic politics of Communist Romania (an answer, in this iteration, to why would autocracies bother). Gramsci (Reference Gramsci2012: 207) argued that a group must already exercise hegemony or “leadership” before attempting to take power. This was not the case in Romania after World War Two, and so this is what the Communists, I have argued, attempted to achieve after the fact. In a way, the authoritarian state apparatus installed once they took power makes it difficult to trace whether they eventually managed to create a hegemonic regime, one that combines force and consent. Yet it is not useful to reify the differences between autocracy and democracy across the sides of the Iron Curtain – as indeed contemporaneous actors did in the West (Bartel Reference Bartel2022). Throughout the Eastern Bloc, regimes were invested in consent: this consent, of course, looked different from that recognizable in the West, but the important point is that they were invested. Put differently, sticky or path-dependent understandings of the state are threatening only to the extent that a political movement is at least somewhat invested in consent. The Romanian communists were therefore seeking to remove rival claims to state power, a process at once structural and cultural. Here, as elsewhere, regime change saw political discourses and performances that sought “not only to be in the right, but also to demolish the basis of [an] opponent’s social and intellectual existence” (Mannheim Reference Mannheim2013: 33–34).Footnote 15

The framework elaborated here has several implications for a sociology of the Cold War. First, I join other research in advocating taking the temporally embedded actor’s view of a situation (e.g., Mische Reference Mische2009; Sendroiu Reference Sendroiu2022) – such that the Cold War as we have come to know it was not experienced as a foregone conclusion when it began. Second and relatedly, the idea of process I elaborate here suggests a view of structural transformation as neither easy nor impossible. That structural transformations puncture the everyday seems the most dramatic lesson of the Cold War: we have seen it end in spectacular fashion. But neither its emergence, its many forms, nor its end happened without tremendous friction among political projects seeking to displace old understandings. Indeed, what is tricky about the Cold War is that it rests mid-range between the effervescence of a relatively bounded historic event (e.g., Sewell Reference Sewell and McDonald1996) and the long-term intractability of deep structures such as capitalism (which has shifted but not broken down; see Chiapello and Boltanski Reference Chiapello and Boltanski2018). The third contribution of this article to a sociology of the Cold War, therefore, rests in elaborating a lumpy, processual take on the reproduction and change of social regularities, one that can better account for the ebbs and flows of the Cold War – including into the present.

Therefore, what this article offers to the broader special issue is a potential mechanism through which we can conceptualize or even trace the incomplete structuring conceptualized in the introduction. If the “medium durée,” “structuring without resolving into structure” proposed in the introduction does indeed characterize both the Cold War (and many other moments of social life), then the way it would function is precisely through the sticky, processual lag I describe here. Some understandings, well and frequently validated, could substantially shape possibilities for meaningful action – while others will be less effective and more open to reinterpretation. The tension at the core of the Cold War was that it allowed space for considerable creativity (as Plys or Steinmetz show in this issue with reference to post-colonial politics) while it was at the same time a lodestar for action (as Clemens or Reed show in this issue with reference to the United States). Even in Romania, deep into the Eastern Bloc, we see this at play: Cold War dynamics needed to be (re)interpreted to the national context, a sleight-of-hand that also involved delegitimating other, older understandings of the Romanian state.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2025.10097

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Shyon Baumann, Ronit Dinovitzer, Ivan Ermakoff, Liora Israël, Kenneth Sebastian Leon, Ron Levi, Sida Liu, Mark Massoud, Kristin Plys, Isaac Ariail Reed, and Mitchell Stevens for their comments. Many thanks also to the fellow special issue authors, as well as to the anonymous reviewers. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at meetings of the Law and Society Association and the Social Science History Association, and benefitted greatly from comments received there.