Non-technical Summary

The late Miocene Kastellios Hill section on Crete is well known for the occurrence of marine and terrestrial fossils (mammals). Authors have disagreed on its exact age, but with increasing mammal finds in other parts of Europe during the past decades, the age of the Kastellios Hill section can now be estimated more precisely. Our comparison of the murid rodents from Kastellios Hill with time-equivalent southern and central European associations has resulted in a partly revised list of murid species at Kastellios Hill consisting of the dominant Progonomys mixtus n. sp., the less common Cricetulodon cf. C. hartenbergeri and P. cathalai, and the rare P. hispanicus and cf. Hansdebruijnia neutra. On the basis of this revised composition and the magnetostratigraphic polarity pattern of the section, the Kastellios Hill mammal sites are now dated at 9.3–9.1 Ma. In addition, the genus Hansdebruijnia is narrowed down to two species in an ancestor–descendant relationship: the ancestral type species H. neutra, restricted to southeastern Europe and Anatolia, and its descendant species and new combination H. magna, which includes “Occitanomys alcala”’ and “O. debruijni” and that colonized both southeastern and southwestern Europe.

Introduction

For more than 50 years, the section of Kastellios Hill (South Heraklion Basin, central Crete, Greece; Fig. 1) has played an important role in the calibration of Miocene European continental Stages to the Geological Time Scale (GTS) because of the alternation of strata with mammalian remains and strata with planktonic foraminifers (de Bruijn et al., Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971; de Bruijn and Zachariasse, Reference de Bruijn and Zachariasse1979; Steininger et al., Reference Steininger, Bernor, Fahlbusch, Lindsay, Fahlbusch and Mein1990, Reference Steininger, Berggren, Kent, Bernor, Sen, Agustí, Bernor, Fahlbusch and Mittmann1996).

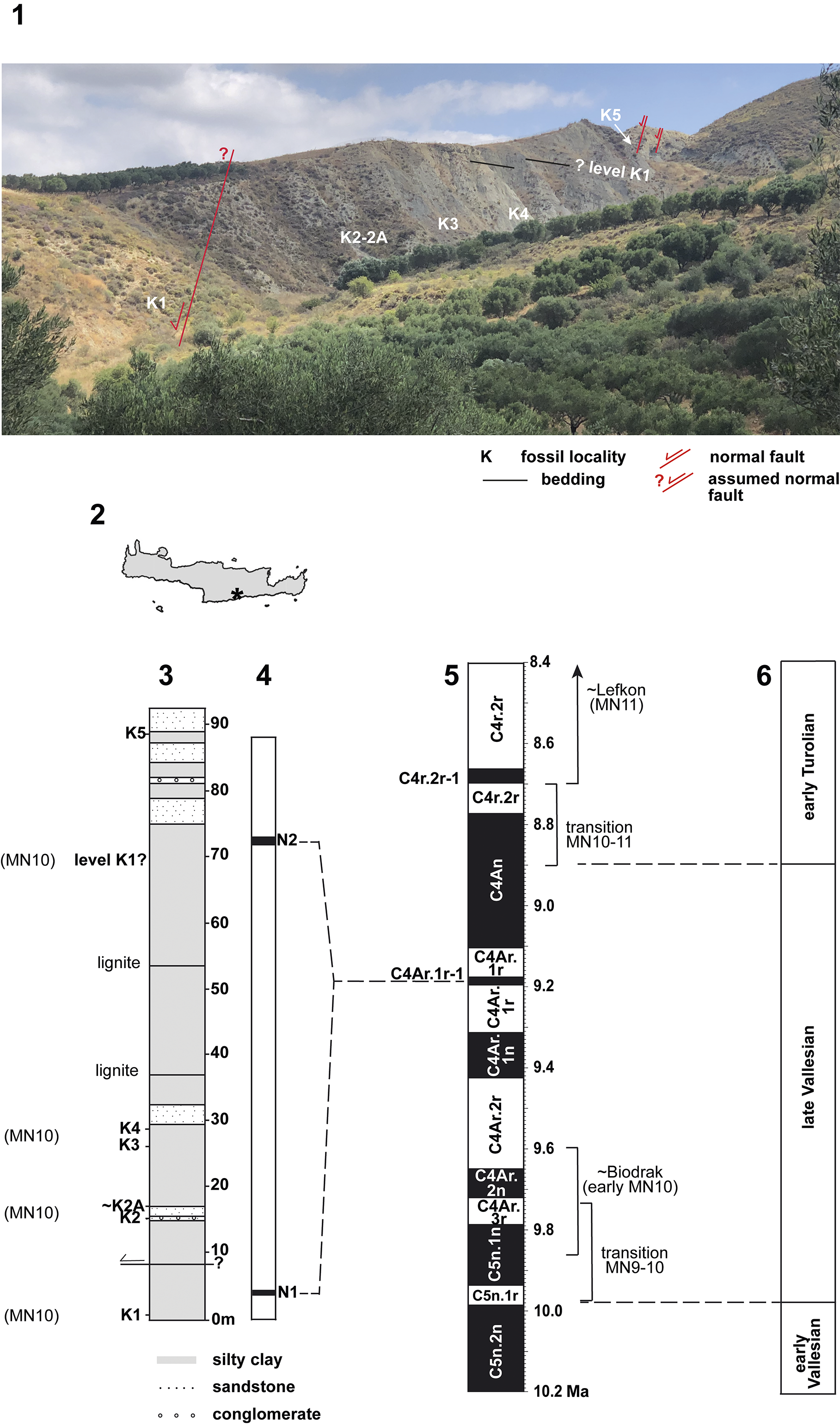

Figure 1. Kastellios Hill section. (1) 2022 photograph with fossil locations and observed (top) and assumed (base) faults. (2) Location of section on the island of Crete (Greece). (3) Lithological column with fossil localities and MN assignments. (4) Polarity intervals N1 and N2 (after Sen et al., Reference Sen, Valet and Ioakim1986) and preferred correlation to the GPTS (assuming N1 = N2). (5) GPTS with relevant mammal biochronological information; reversal ages after Raffi et al. (Reference Raffi, Wade, Pälike, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020). (6) European continental mammal Stages/Ages with ages after Hilgen et al. (Reference Hilgen, Lourens, van Dam, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012) and van Dam et al. (Reference van Dam, Krijgsman, Abels, Álvarez-Sierra, García-Paredes, López-Guerrero, Peláez-Campomanes and Ventra2014).

Despite the presence of mammals, planktonic foraminifers, and magnetic polarity data, the section is still no better dated than to the nearest 0.5 Myr. The reasons for this are partly biostratigraphic (uncertain correlations to mammal faunas elsewhere; low resolution of marine planktonic foraminiferal zones) and partly magnetostratigraphic (polarity pattern is difficult to calibrate to the Geomagnetic Polarity Time Scale [GPTS]). The most recent calibration to either Chron C4Ar.2r or Chron C4Ar.1r is based on the original rodent fauna list, dominantly reversed magnetic polarities (Sen et al., Reference Sen, Valet and Ioakim1986; Duermeijer et al., Reference Duermeijer, Krijgsman, Langereis and ten Veen1998), and a numerical age of 9.6 Ma for the top of the underlying marine Skinias Formation (Zachariasse et al., Reference Zachariasse, van Hinsbergen and Fortuin2011), providing a maximum age range of 9.65–9.11 Ma (ages for base C4Ar.2r and top C4Ar.1r; Raffi et al., Reference Raffi, Wade, Pälike, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020). The strata with mammals would thus belong to the late Vallesian of the European Neogene continental chronological scale (10.0–8.9 Ma; Fig. 1), which correlates to the middle Tortonian of the GTS.

The progress made in late Miocene European small mammal systematics and biochronology over the past decades provides an opportunity to re-evaluate the age of the Kastellios Hill section and the taxonomy of the published small mammal species. Especially, a new series of calibrations of Spanish Vallesian and Turolian sections rich in rodent species to the GTS (Garcés et al., Reference Garcés, Agustí, Cabrera and Parés1996; Krijgsman et al., Reference Krijgsman, Garcés, Langereis, Daams, van Dam, van der Meulen, Agustí and Cabrera1996; van Dam et al., Reference van Dam, Alcalá, Alonzo Zarza, Calvo, Garcés and Krijgsman2001, Reference van Dam, Krijgsman, Abels, Álvarez-Sierra, García-Paredes, López-Guerrero, Peláez-Campomanes and Ventra2014, Reference van Dam, Mein, Garcés, van Balen, Furió and Alcalá2023a; Abdul Aziz et al., Reference Abdul Aziz, van Dam, Hilgen and Krijgsman2004; Casanovas-Vilar et al., Reference Casanovas-Vilar, Garcés, van Dam, García-Paredes, Robles and Alba2016) allows for a better comparison between the Kastellios Hill rodents and the well-dated, time-equivalent Spanish ones.

Historical overview

In 1967, W.J.Z. was the first to describe and sample the section. The finding of a Hipparion s.l. molar on that occasion initiated a first study on the mammalian fossils (de Bruijn et al., Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971). These authors concluded that the upper Vallesian (MN10) of the European continental chronostratigraphic scale correlates to the lower Tortonian Stage of the GTS. The rodent species identified in that study (levels K1 and K3; Fig. 1) include the murines Progonomys cf. P. woelferi Bachmayer and Wilson, Reference Bachmayer and Wilson1970 (the dominant form) and Progonomys cathalai Schaub, Reference Schaub1938, the cricetine Cricetulodon cf. C. sabadellensis Hartenberger, Reference Hartenberger1965, and the sciurid Csakvaromys bredai (Schlosser, Reference Schlosser1884). The inferred age range was based on Murinae: whereas the smaller-sized Progonomys cathalai pointed to a late Vallesian age as defined in Spain (e.g., van de Weerd, Reference van de Weerd1976), the larger-sized Progonomys cf. P. woelferi indicated an early Turolian age given its presence in the Austrian site Kohfidisch (MN11; Daxner-Höck and Höck, Reference Daxner-Höck and Höck2015).

Because the paper on Kohfidisch (Bachmayer and Wilson, Reference Bachmayer and Wilson1970) was in the process of publishing, de Bruijn et al. (Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971) were unable to directly compare their fauna with that of Kohfidisch and considered the specific determination of the larger murine preliminary (“it may well appear that the Kastellios specimens are specifically different, hence the ‘confer’ determination”; de Bruijn et al., Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971, p. 11). Furthermore, the presence of the cricetine Cricetulodon, with an evolutionary stage fitting that of both C. sabadellensis and C. hartenbergeri Freudenthal, Reference Freudenthal1967, was taken as indicative for the Vallesian as based on the Spanish record.

In addition to the rodents, de Bruijn et al. (Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971) described several large mammals from Kastellios Hill levels K2 and K5 and from the eastern slope of the hill (“K east” as named by Koufos, Reference Koufos2006) (Fig. 1). These included the equid Hipparion sp., a tragulid possibly representing Dorcabune anthracotheroides Pilgrim, Reference Pilgrim1910, a suid that could belong to either Taucanamo or Yunnanochoerus, a cervid resembling (cf.) Procapreolus pentelici (Dames, Reference Dames1883), an unidentified bovid, and an unidentified mustelid (updates by van der Made, Reference van der Made and Reese1996; see also Koufos, Reference Koufos2006). According to de Bruijn et al. (Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971), the size and morphology of the Hipparion teeth suggest a Vallesian age, although the authors acknowledge that the difference between forms before and just after the early Turolian radiation of Hipparion is difficult to establish with certainty on the basis of teeth only. A relatively large facet for the trapezium on the second metacarpal of Hipparion (K2) would suggest a somewhat older, Vallesian age. However, the presence of cervids is especially compatible with a post-Vallesian age (van der Made, Reference van der Made and Reese1996).

On the basis of the planktonic foraminiferal species Neogloboquadrina acostaensis (Blow, Reference Blow1959) and Globorotalia gigantea Blow, Reference Blow1959 and the evolutionary stage of the benthic foraminifer species Uvigerina selliana Meulenkamp, 1969, de Bruijn et al. (Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971) correlated sample K4 (Fig. 1) to the lower Tortonian and more specifically to the lower part of planktonic foraminiferal biozone N16 (Blow, Reference Blow, Bronnimann and Renz1969). This correlation was later confirmed by the results of pollen analysis, allowing a correlation to the lower part of the Eastern Mediterranean Kizilhisar pollen zone, whose age was considered early Tortonian (Benda et al., Reference Benda, Meulenkamp and Zachariasse1974; Benda and Meulenkamp, Reference Benda and Meulenkamp1990; Steininger et al., Reference Steininger, Berggren, Kent, Bernor, Sen, Agustí, Bernor, Fahlbusch and Mittmann1996).

Various modifications to the faunal list of de Bruijn et al. (Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971) were subsequently suggested. For example, while discussing new murines from the area near Thessaloniki (northern Greece), de Bonis and Melentis (Reference de Bonis and Melentis1975) favored an assignment of the large-sized murine to “Valerimys” (now Huerzelerimys) vireti (Schaub, Reference Schaub1938) instead of Progonomys woelferi. Unfortunately, no descriptive details were given to back up this claim. If the large murine indeed would be represented by H. vireti (Schaub, Reference Schaub1938), the levels with this species would belong to the lower Turolian (MN11; see van Dam et al., Reference van Dam, Mein, Garcés, van Balen, Furió and Alcalá2023a).

In a second work on Kastellios Hill, de Bruijn and Zachariasse (Reference de Bruijn and Zachariasse1979) presented the results of a larger, second sample taken at level K1 and a new level positioned just above K2 (K2A as indicated in the Utrecht collection; Fig. 1). This significantly increased the collection of K1, yielding more molars of the large-sized murine, several new cricetine teeth, and one tooth from the previously unrecorded glirid Muscardinus cf. M. hispanicus de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1966. Finally, van der Made (Reference van der Made and Reese1996) described two previously unpublished insectivore teeth from K1 as Schizogalerix sinapenesis Sen, Reference Sen1990, but these teeth were later attributed to S. macedonica Doukas in Doukas et al., Reference Doukas, van den Hoek Ostende, Theocharopulos and Reumer1995 or S. zapfei (Bachmayer and Wilson, Reference Bachmayer and Wilson1970)/S. attica (Rümke, Reference Rümke1976) (see: Furió et al., Reference Furió, van Dam and Kaya2014).

On the basis of a direct comparison with material from Kohfidisch (Bachmayer and Wilson, Reference Bachmayer and Wilson1970), de Bruijn and Zachariasse (Reference de Bruijn and Zachariasse1979) retained their assignment of the dominant murine to P. woelferi, while dropping the cf. designation. The fact that this species entered the area (in K1 and K3) before the smaller-sized and morphologically more primitive P. cathalai (in K2 and K3) was not regarded as problematic. De Bruijn and Zachariasse (Reference de Bruijn and Zachariasse1979) placed K1 in the lower Vallesian (MN9) despite the fact that P. cathalai is characteristic for the upper Vallesian in Spain. At the same time, these authors were more cautious about the cricetine species and refrained from its generic assignment to either Cricetulodon or “Kowalskia” (= Neocricetodon). Furthermore, de Bruijn and Zachariasse (Reference de Bruijn and Zachariasse1979) re-interpretated part of the planktonic foraminiferal fauna and noted the joint presence of N. acostaensis (with a coiling ratio of 60–65 % to the right), Globorotaloides falconarae Giannelli and Salvatorini, Reference Giannelli and Salvatorini1976, and Globorotalia ventriosa Ogniben, Reference Ogniben1958, providing a stronger basis for the assignment of the association from K4 to the lower part of Tortonian biozone N16.

A new perspective was added by Sen et al. (Reference Sen, Valet and Ioakim1986), who took paleomagnetic samples from the section. The authors found dominant reversed polarities interrupted by two very short (<2 m) normal intervals (N1 and N2; Fig. 1). They correlated the section to Chron C5r (12.05–11.06 Ma), an interpretation later adopted by Steininger et al. (Reference Steininger, Bernor, Fahlbusch, Lindsay, Fahlbusch and Mein1990) and Sen (Reference Sen1990). Meanwhile, however, the Eurasian distribution of Progonomys woelferi was better known, and the species was now regarded as characteristic for the late Vallesian (MN10; Mein et al. Reference Mein, Martín Suárez and Agustí1993, see also de Bruijn et al., Reference de Bruijn, Daams, Daxner-Höck, Fahlbusch, Ginsburg, Mein and Morales1992) and not for the early Vallesian (MN9) as previously assumed. This new insight implied that the lower level K1 should also be placed in the upper Vallesian (MN10).

New magnetostratigraphic studies in Spain and Anatolia (Kappelman et al., Reference Kappelman, Sen, Fortelius, Duncan, Alpagut, Bernor, Fahlbusch and Mittmann1996; Krijgsman et al., Reference Krijgsman, Garcés, Langereis, Daams, van Dam, van der Meulen, Agustí and Cabrera1996) confirmed that upper Vallesian (MN10) sediments post-date Chron C5n (11.06–9.79 Ma), whereas the lower Vallesian (MN9) roughly coincides with that chron. With the rodent fauna assumed to be late Vallesian (MN10), Steininger et al. (Reference Steininger, Berggren, Kent, Bernor, Sen, Agustí, Bernor, Fahlbusch and Mittmann1996, p. 35) interpreted the dominantly reversed magnetostratigraphic polarity data (Sen, Reference Sen1990) as belonging to C4Ar and correlated K1 to C4Ar.2r (9.65–9.43 Ma), K2 to the base of C4Ar.1r (~9.3 Ma), and K5 to C4An (9.11–8.77 Ma) (ages according to Raffi et al., Reference Raffi, Wade, Pälike, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2020; Fig. 1). Aguilar et al. (Reference Aguilar, Berggren, Aubry, Clauzon, Benammi and Michaux2004), however, supported the original correlation to Chron C5r (12.05–11.06 Ma), assuming a very early presence of Progonomys in Europe, while suggesting a substantial reworking of foraminifers in large parts of the Kastellios Hill section. In their revision of the central Cretan stratigraphy and chronology, Zachariasse et al. (Reference Zachariasse, van Hinsbergen and Fortuin2011) concluded that the low numbers of open marine benthic and planktonic foraminifers are reworked from the underlying marine Skinias Formation (see the detailed report on the Kastellios Hill section in appendix 1, location 8 in Zachariasse et al., Reference Zachariasse, van Hinsbergen and Fortuin2011). The authors further concluded that the section correlates either with Chron C4Ar.2r or with C4Ar.1r on the basis of the dominant reversed magnetic polarity data (Sen et al., Reference Sen, Valet and Ioakim1986; Duermeijer et al., Reference Duermeijer, Krijgsman, Langereis and ten Veen1998) and an age estimate for the top of the underlying marine Skinias Formation of ~9.6 Ma. Their preference for C4Ar.1r was based on an alleged age of 9.6–9.3 Ma for the older mammal fauna of Plakias.

The small mammal fauna of Plakias (located ~80 km to the west of Kastellios Hill) was resampled and redescribed by de Bruijn et al. (Reference de Bruijn, Doukas, van den Hoek Ostende and Zachariasse2012). Because of the absence in Plakias of murines (Progonomys), and the presence of Glirulus (Paraglirulus) werenfelsi (Engesser, Reference Engesser1972), Eumyarion leemanni (Hartenberger, Reference Hartenberger1965), and two primitive-looking cricetines (Cricetulodon cretensis de Bruijn and Meulenkamp, Reference de Bruijn and Meulenkamp1972 and Cricetinae sp.), de Bruijn et al. (Reference de Bruijn, Doukas, van den Hoek Ostende and Zachariasse2012) correlated Plakias to “lower” MN9. However, given what we now know on the persistence of G. werenfelsi and E. leemani into MN10 (e.g., Casanovas-Vilar et al., Reference Casanovas-Vilar, Garcés, van Dam, García-Paredes, Robles and Alba2016) and given the scarcity of southeastern European upper MN9 and MN10 localities (with cricetines) to compare with, the age of the locality cannot in fact be further specified than MN9. This unit has a maximum age of 11.2 Ma and a minimum age of either 10.0 Ma (when defined by the common occurrence of the immigrant Progonomys; van Dam et al., Reference van Dam, Krijgsman, Abels, Álvarez-Sierra, García-Paredes, López-Guerrero, Peláez-Campomanes and Ventra2014) or 9.8 Ma (when defined by the reference locality Can Llobateres; Casanovas-Vilar et al., Reference Casanovas-Vilar, Garcés, van Dam, García-Paredes, Robles and Alba2016; for the two types of MN definition, see Hilgen et al., Reference Hilgen, Lourens, van Dam, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012). The much younger alternative age of approximately 9.6 Ma for Plakias (de Bruijn et al., Reference de Bruijn, Doukas, van den Hoek Ostende and Zachariasse2012) can therefore be discarded. However, a maximum age of 10.4–10.3 Ma for the Plakias fauna (and therefore also for Kastellios Hill) is suggested by the phyllite–quartzite debris in the unit from which the Plakias small mammals have been collected because exhumation of these low-grade metamorphic rocks did not occur on Crete before that time (Zachariasse et al., Reference Zachariasse, van Hinsbergen and Fortuin2011).

In his recently published overview of Greek large mammal sites, Koufos (Reference Koufos2024) again relied on the old magnetostratigraphic interpretation of Sen et al. (Reference Sen, Valet and Ioakim1986) and placed the Kastellios Hill very low in the GTS (Chron C5r; 12.05–11.06 Ma). We expect that our new study will convince paleontologists and stratigraphers of a significantly younger age of the Kastellios Hill mammals.

Materials and methods

The material from Kasteliana 1, 2A, and 3 (K1, K2A, and K3) is stored in the Department of Earth Sciences at Utrecht University, the Netherlands. Dental terminology in Cricetinae after Mein and Freudenthal (Reference Mein and Freudenthal1971) and in Murinae after van de Weerd (Reference van de Weerd1976). Measuring methods after van de Weerd (Reference van de Weerd1976).

Repository and institutional abbreviation

ESUU, Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

Systematic paleontology

Family Muridae Illiger, Reference Illiger1811

Subfamily Cricetinae Fischer, Reference Fischer1817

Cricetulodon Hartenberger, Reference Hartenberger1965

Type species

Cricetulodon sabadellensis Hartenberger, Reference Hartenberger1965 from Can Llobateres (Spain).

Cricetulodon cf. C. hartenbergeri Freudenthal, Reference Freudenthal1967

Figure 2. Representative specimens of Muridae from Kastellios Hill: (1–4) Cricetulodon cf. C. hartenbergeri; (5, 6, 8, 9) Progonomys cathalai; (7, 10–15) Progonomys mixtus n. sp, figures after de Bruijn et al. (Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971, pls. 2, 3). (1) Right m1, KA1–101; (2) right m3, KA1–116; (3) left M2, KA1–121; (4) right M3, KA1–126; (5) left m1, KA3–71; (6) left M2, KA3–51; (7) left M1, KA1–51 (holotype); (8) left M3, KA3–61; (9) left m2, KA3–81; (10) right m2, KA1–21; (11) right m1, KA1–11; (12) left m3, KA1–41; (13) left m2, KA1–11; (14) right M2, KA1–71; (15) left M3, K1–92.

Holotype

m1 (PEC 585) from Pedregueras 2C, Biozone I (lower Vallesian), Calatayud-Montalbán Basin, Spain (Freudenthal, Reference Freudenthal1967, pl. 1, fig. 14).

Material

M2, KA1–121, 122; M3, KA1–126; m1, KA1–101, 102; m2, KA1–105, 106; m3, KA1–111.

Description

Our descriptions of the K1 material extend on those of de Bruijn et al. (Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971) and de Bruijn and Zachariasse (Reference de Bruijn and Zachariasse1979). We focus on specific morphological details that are relevant for the comparison with other, time-equivalent Cricetulodon and Neocricetodon populations.

M2

Short mesolophs (Fig. 2.3). Protolophule double. Anterior metalophule lacking, but weak or strong posterior metalophule present. Three-rooted.

M3

Length and width similar (Fig. 2.4). Posterior border relatively straight. Double protolophule present. Mesoloph absent. Long metaloph branching off from anterior metalophule and running toward a position between paracone and metacone.

m1

One specimen is complete (Fig. 2.1); the other lacks the anterior cusps and has a smaller width (1.09 versus 1.20 mm). Well-formed anterolophulids absent (as observed by de Bruijn et al., Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971); a very incipient (widely separated) and low-placed double anterolophulid can nevertheless be recognized. At least one lingual anterolophulid can be observed in the broken specimen. Posterior metalophulid and posterior hypolophulid lacking. Anterior hypolophulid very short and placed relatively posteriorly (buccally of entoconid), creating a relatively short posterosinusid. Both specimens have a long mesolophid, reaching the lingual border (Fig. 2.1) or reaching a length two-thirds of the maximum (second specimen). Because of the long mesolophid, the mesosinusid has a relatively acute angle and is running parallel to the mesolophid. The posterolophid is connected to the entoconid along the lingual border.

m2

Second lower molars are represented by one complete specimen and one broken specimen that lacks the anterolingual part (including part of the mesolophid). The anterior hypolophulid is placed as in m1, resulting in a short posterosinusid. The complete specimen has a short mesolophid that runs down to the base of the metaconid.

m3

The third lower molar is triangular and has a simple structure (Fig. 2.2). Onset of mesolophid present and posterior protolophulid lacking.

Dimensions

See Table 1 and Appendix 1.

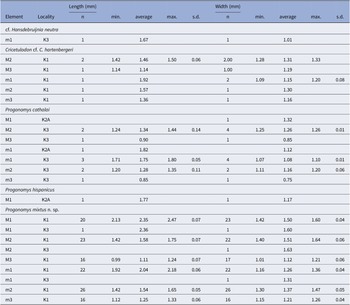

Table 1. Molar dimensions for the murid species of Kastellios Hill. n = number of measurable specimens; min.= minimum dimension; max. = maximum dimension; s.d. = standard deviation

Remarks

The K1 cricetine clearly belongs to the Cricetulodon–Neocricetodon group. Specific assignment is not straightforward, however, because the material is scarce (with M1 lacking altogether) and morphological overlap between species is considerable. Even the separation between the two genera is problematic, with some authors preferring synonymy (e.g., Daxner-Höck et al., Reference Daxner-Höck, Fahlbusch, Kordos, Wu, Bernor, Fahlbusch and Mittmann1996). In their study of Spanish and French cricetines, Freudenthal et al. (Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martín Suárez1998) retain the two genera although their analysis yields very few discriminatory characters, of which the dominance of the lingual (Cricetulodon) versus buccal (Neocricetodon) anterolophulid in m1 is thought to be the most diagnostic. Recently, Sinitsa and Delinschi (Reference Sinitsa and Delinschi2016) reviewed the genus Neocricetodon and presented a phylogenetic analysis suggesting that Cricetulodon and Neocricetodon are sister groups that are derived from an advanced Democricetodon form.

Here we refrain from discussing cricetine systematics at the generic level and focus on species-level characteristics. To this aim, we compared the Kastellios Hill species with Cricetulodon cretensis from the older Cretan site Plakias (PL; MN9, 10.4–10.0 Ma; de Bruijn et al., Reference de Bruijn, Doukas, van den Hoek Ostende and Zachariasse2012), with five Spanish cricetine type populations represented in the ESUU collection, and with two French and two Moldavian populations as described in the literature. The comparative material thus consists of Cricetulodon hartenbergeri from Pedregueras 2C (PED2C; MN9, 10.4 Ma; Freudenthal, Reference Freudenthal1967, age after van Dam et al., Reference van Dam, Krijgsman, Abels, Álvarez-Sierra, García-Paredes, López-Guerrero, Peláez-Campomanes and Ventra2014), Cricetulodon sabadellensis from Can Llobateres 1 (CL1; MN9, 9.76 Ma; Hartenberger, Reference Hartenberger1965; age after Casanovas-Vilar et al., Reference Casanovas-Vilar, Garcés, van Dam, García-Paredes, Robles and Alba2016), Neocricetodon occidentalis (Aguilar, Reference Aguilar1982) from Crevillente 2 and Tortajada A (CR2, TOA; MN11, both ~8.2 Ma; de Bruijn et al., Reference de Bruijn, Mein, Montenat and van de Weerd1975; van de Weerd, Reference van de Weerd1976; Freudenthal et al., Reference Freudenthal, Lacomba and Martín Suárez1991; ages after van Dam et al., Reference van Dam, Mein, Garcés, van Balen, Furió and Alcalá2023a), Cricetulodon bugesiensis Freudenthal, Mein, and Martín Suárez, Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martín Suárez1998 from Soblay (SOBL; late MN10), Neocricetodon ambarrensis Freudenthal, Mein, and Martín Suárez, Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martín Suárez1998 from Ambérieu 2C (AMB2C; early MN11; Freudenthal et al., Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martín Suárez1998; chronological placement by Mein, Reference Mein, Agustí, Rook and Andrews1999), and N. moldavicus (Lungu, Reference Lungu1981) from Calfa and Buzhor 1 (CAL, BUJ1; MN10, Sinitsa and Delinschi, Reference Sinitsa and Delinschi2016).

M2

The two specimens from K1 (1.42 × 1.28, 1.50 × 1.33 mm) are longer than the single M2 from PL (1.33 × 1.24 mm; Fig. 3.3). In addition (as already noted by de Bruijn et al., Reference de Bruijn, Doukas, van den Hoek Ostende and Zachariasse2012), the latter specimen has its posterior protolophule directly connected to the anterior arm of the hypocone rather than the posterior arm of the protocone (see also de Bruijn and Meulenkamp, Reference de Bruijn and Meulenkamp1972, pl. 1, fig. 5). Furthermore, the Plakias specimen has no mesoloph or metaloph. Both populations share the absence of the anterior metalophule.

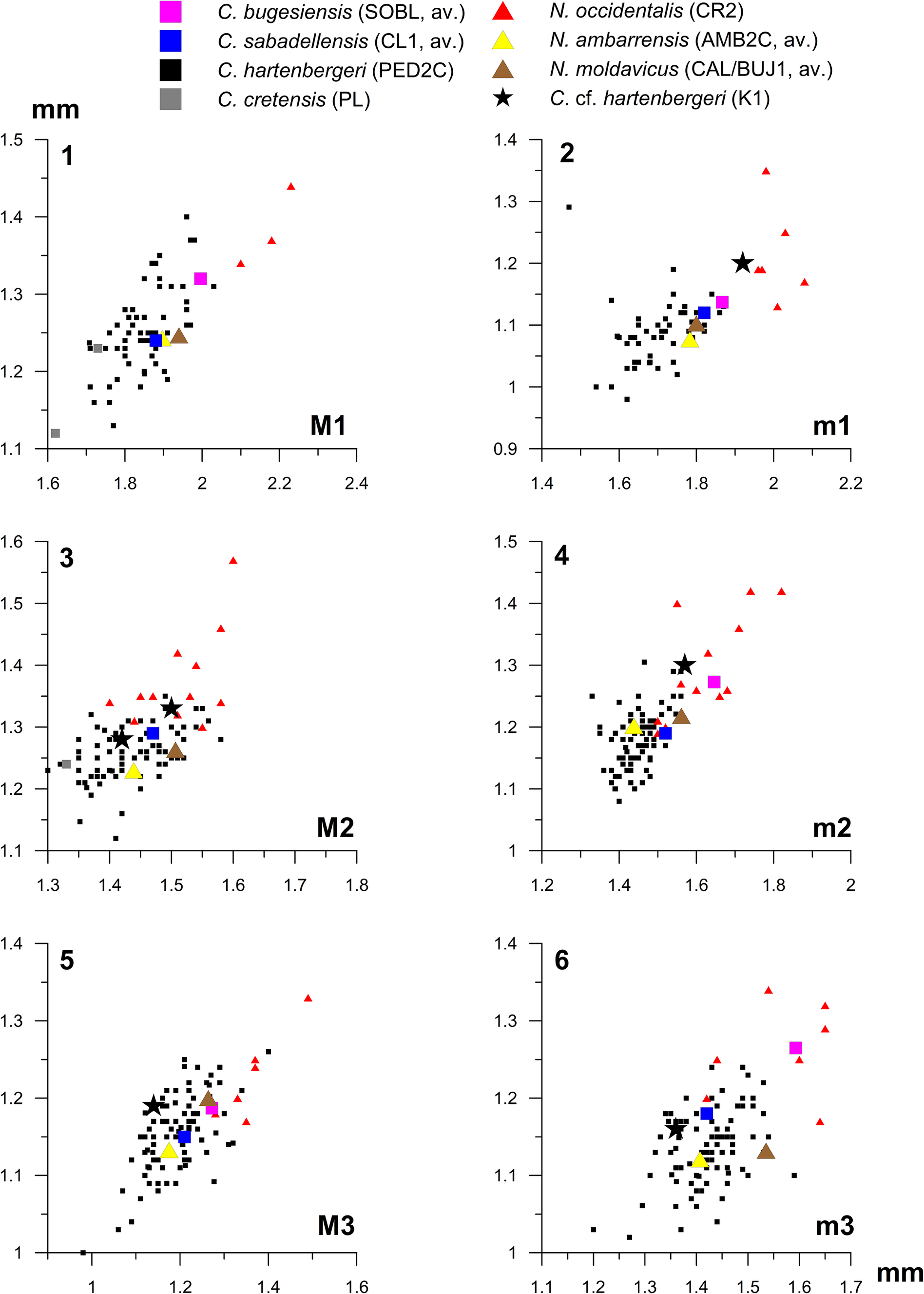

Figure 3. Length–width diagrams for studied Cricetulodon and Neocricetodon species. AMB2C = Ambérieu 2C; CL1 = Can Llobateres 1; CR2 = Crevillente 2; K1 = Kastellios Hill (K1); PED2C = Pedregueras 2C; PL = Plakias; SOBL = Soblay; CAL/BUJ1 = Calfa/Bujor 1; av. = average value. (1) Upper first molar; (2) lower first molar; (3) upper second molar; (4) lower second molar; (5) upper third molar; (6) lower third molar.

The M2 from K1 (Fig. 2.3) share the short mesoloph with the Spanish specimens from CL1, whereas the mesoloph in PED2C is somewhat longer. The mesoloph has a variable length in SOBL, AMB2C and CAL/BUJ1 and may even be absent in the former two sites. Mesolophs are long and may or may not reach the buccal border in the younger Spanish site CR2.

The double protolophule is shared with M2 from PED2C, CL1, and CAL/BUJ1, although the anterior one is relatively weak in the Spanish populations and may be very low in CL1. The anterior metalophule is absent in K1, PED2C, and CL1. The posterior metalophule, which is either weak or strong in K1, is mostly present in PED2C and always present in CL1. A highly variable configuration of metalophules in the M2 characterizes SOBL, where both anterior and posterior metalophule may be present or absent. By contrast, the anterior metalophule is always present in AMB2C and the posterior metalophule either present or absent. Protolophules and metalophules are double in CR2, although the anterior metalophule is missing in a minority of specimens. A larger width/length ratio separates the CR2 population from the other populations (Fig. 3.3).

Sinitsa and Delinschi (Reference Sinitsa and Delinschi2016) considered the presence of four roots in the M2 a diagnostic character for Neocricetodon. The possession of four roots in early representatives such as N. ambarrensis and N. moldavicus distinguishes these species from the M2 in K1, which has three roots.

M3

The specimen from K1 is broad posteriorly with tooth length and width approximately similar (Fig. 2.4). Comparable shapes occur in PED2C and CL1, although these populations also contain posteriorly asymmetric (pointed, i.e., posterolingually reduced) specimens. These asymmetric specimens form the dominant morphotype in the other studied populations as well.

The double protolophule in the K1 specimen is shared with other populations, although in a minority of specimens from CL1 it is rather low. As mentioned, a long metaloph branches off from the anterior metalophule in K1 and runs toward a position between paracone and metacone. A similar branching structure is common in the M3 from CL1 (that sometimes contain a small onset of a mesoloph as well) and also characterizes part of the specimens of N. moldavicus (Sinitsa and Delinschi, Reference Sinitsa and Delinschi2016, fig. 3). In PED2C, a single ridge representing the mesoloph or anterior metalophule is curved and runs toward the (reduced) metacone. The anterior metalophule is always present in SOBL, but the metaloph may be missing. Branching metalophule–mesoloph structures also occur in AMB2C although the mesoloph may be independent or absent as well (Freudenthal et al., Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martín Suárez1998). Branching may or may not occur in the specimens of CR2, which, like the specimens from PED2C and CL1, are pointed posterolingually.

The absence of a mesoloph in M3 is shared with many other sites, although in the Spanish populations also short (PED2C) and even long (CL1) mesolophs occur. The M3 from CR2 have complete mesolophs that mostly connect to the metacone.

m1

Size of the m1 from K1 fits the upper part of the distribution of PED2C and CL1, is somewhat larger than in SOBL, AMB2C, and CAL/BUJ1, and fits the lower part of the distribution of CR2 (Fig. 3.2).

The morphology of the anterolophulid(s), hypolophulid(s), mesolophid, and posterolophid–entoconid connection varies considerably between the studied populations. The anterolophulid is lingually positioned on the single specimen from K1 that contains this ridge. It is also dominantly lingual in PED2C and CL1. In SOBL and CAL/BUJ1 it is often double, whereas in AMB2C there is no preference for either a lingual or buccal anterolophulid (but few specimens are present). The anterolophulid is double or dominantly buccal in CR2 and double in the single specimen from TOA. The anterior hypolophulid is very short in K1 and placed buccally of the entoconid, creating a relatively short posterosinusid (Fig. 2.1). This feature is shared with many m1 from CL1 but less with the m1 from PED2C. The anterior hypolophulid is placed relatively anterolingually in CR2 and CAL/BUJ1, resulting in a crescent-shaped posterosinusid.

Whereas the mesolophid is long in K1 (Fig. 2.1), it is highly variable and sometimes absent in PED2C and very short in CL1 (resulting in a curved instead of acute mesosinusid angle). It is absent in half of the specimens from SOBL and variable when present. It is also variable in AMB2C and CAL/BUJ1. By contrast, mesolophids in CR2 are complete and end with a small lingual cuspule (mesostylid). The m1 from TOA of the same species (N. occidentalis) lacks the mesolophid, but a mesostylid is present. The posterolophid is connected to the entoconid along the lingual border in K1 and PED2C (where it is high). It is mostly, but not always, connected to the entoconid in CL1. As judged from images in Freudenthal et al. (Reference Freudenthal, Mein and Martín Suárez1998) and Sinitsa and Delinschi (Reference Sinitsa and Delinschi2016), the posterolophid is not very high at the connection with the entoconid in SOBL, AMB2C, and CAL/BUJ1. In CR2, the posterolophid is not connected to the entoconid, whereas it is connected by a low ridge in TOA.

m2

The anterior hypolophulid in the two K1 specimens is placed relatively posteriorly with respect to the entoconid as in m1, resulting in a short posterosinusid. This configuration is not so different from that in CL1, PED2C, and AMB2C, but differs from that in SOBL, CR2, and CAL/BUJ1, where the anterior hypolophulid is placed more anteriorly. The single complete m2 from K1 has a short mesolophid running down to the base of the paraconid, a configuration that also occasionally occurs in CR2. The mesolophid is absent or very short in PED2C, whereas it is absent in almost all specimens from CL1 and SOBL, evidencing the relative reduction of the mesolophid in m2 with respect to m1. In CR2, the average length of the mesolophid is shorter in m2 than in m1 as well, with a long mesolophid occurring in less than half of the specimens. Most mesolophids in the CAL/BUJ1 m2 are long or of medium length.

m3

Size and morphology of the m3 are similar to those in PED2C and CL1, although the latter two populations also contain less-reduced (posteriorly broader) specimens. The m3 from CR2 and SOBL are clearly larger in both the length and width dimensions, whereas the m3 from CAL/BUJ1 are larger in the length direction only (Fig. 3.6). The presence of an onset of a mesolophid in the K1 specimen (Fig. 2.2) compares well to the absence or short length of the mesolophid in PED2C and CL1, although longer mesolophids may occur in CL1. Mesolophids are mostly absent in SOBL but long in AMB2C, CAL/BUJ1, and CR2. Whereas the mesolophid is connected to the entoconid in CAL/BUJ1, it is connected to the metaconid in CR2.

Summary

Average tooth size of the Kastellios Hill cricetine is larger than that of C. cretensis, smaller than that of N. occidentalis, and roughly similar to that of C. hartenbergeri, C. sabadellensis, C. bugesiensis, N. ambarrensis, and N. moldavicus (Fig. 3). Although the M2 is the only overlapping element for the two Cretan localities, both size and morphological differences (absence of mesoloph/metaloph and aberrant protoconule–hypocone arm connection in PL) are large enough to separate the populations systematically.

The two m1 from K1 share the more posterior and buccal placement of the anterior hypolophulid, the occurrence of a lingual anterolophulid, and the presence of a posterolophid–entoconid connection with the m1 from the MN9–10 populations PED2C (Cricetulodon hartenbergeri), CL1 (C. sabadellensis), and AMB2C (Neocricetodon ambarrensis) and not with the younger (MN11) m1 from CR2 and TOA (N. occidentalis). A long mesolophid distinguishes the K1 population from the supposedly older population of C. sabadellensis from CL1 (latest MN9), in which average mesolophid length is shorter than in the still older C. hartenbergeri population from PED2C. Any conclusions on similarities of mesolophid morphology with N. ambarrensis and N. moldavicus are difficult to draw because of the strong variability in this character and the small sample size of K1. Mesolophids become long (again) in the m1 of younger (MN11) populations of N. occidentalis such as CR2 and TOA, which differ from the K1 population in many other features as well.

The m2 from K1 share the posterior placement of the anterior hypolophulid with C. hartenbergeri, C. sabadellensis, and Neocricetodon ambarrensis. Size and overall morphology of the m3 are shared with C. hartenbergeri, C. sabadellensis, and N. moldavicus, although N. moldavicus seems slightly more gracile (Fig. 3.4). In contrast to the configuration in the m3 from K1, mesolophids are long in N. ambarrensis and N. moldavicus and medium to long in N. occidentalis. The M2 from AMB2C differ from the M2 in K1 by the presence of an anterior metalophule. Total or dominant absence of a mesoloph in M3 is shared with all populations except CAL/BUJ1, where a short mesoloph may be present, and with CR2.

The K1 population mostly resembles C. hartenbergeri, C. sabadellensis, and N. ambarrensis. Here we favor a tentative (cf.) assignment C. hartenbergeri because none of the five elements (M2, M3, m1, m2, m3) shows a marked difference from the population from PED2C, whereas the m1 of C. sabadellensis from CL1 have a short mesoloph and the m3 of N. ambarrensis from AMB2C have mostly long mesolophids and its M2 have an anterior metalophule and four roots. Whereas de Bruijn et al. (Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971) favored the designation Cricetulodon cf. C. sabadellensis, they did not explicitly exclude C. hartenbergeri. Regardless of the species name, a cf. designation for the K1 population is appropriate because of the small sample size.

Subfamily Murinae Illiger, Reference Illiger1811

Progonomys Schaub, Reference Schaub1938

Type species

Progonomys cathalai. From Montredon (France).

Progonomys hispanicus Michaux, Reference Michaux1971

van Dam (Reference van Dam1997), figure 3.9

Reference de Bruijn and Zachariasse1979 Progonomys cathalai; de Bruijn and Zachariasse, p. 221, fig. 3.

Reference Mein, Martín Suárez and Agustí1993 ‘Progonomys cathalai’; Mein et al., p. 25, fig. 2d.

Reference van Dam1997 Progonomys hispanicus; van Dam, p. 53, fig. 3.9.

Holotype

M1 (MBB-885) from Masía del Barbo 2B, Alfambra formation, Biozone J2 (upper Vallesian), Teruel Basin, Spain (Michaux, Reference Michaux1971, pl. 3, fig. 7).

Material

One left M1, KA2A–45.

Description

See van Dam (Reference van Dam1997, p. 53).

Remarks

The single M1 specimen (1.77 × 1.17 mm, Table 1) was assigned to Progonomys hispanicus by van Dam (Reference van Dam1997) after a comparison of the specimen with the P. hispanicus and P. cathalai type material. Here we confirm this allocation after an additional comparison with P. debruijni (locality 182A; Jacobs, Reference Jacobs1978). With a mean length of 1.66 (variation 1.55–1.82 mm, n = 22) and a mean width of 1.02 (0.88–1.12 mm, n = 22), P. debruijni is smaller (width of KA2A–45 exceeds the maximum value in locality 182A). In addition, the M1 of P. debruijni are characterized by a more elongated (ridge-like) t1.

The dimensions of KA2A–45 are comparable to those of the Progonomys hispanicus type level Masía del Barbo 2B (MBB, Zone J2, 9.7 Ma, average dimensions 1.77 × 1.13 mm) and the stratigraphically lower level Masía del Barbo 2A (MBA; Zone J1; 9.8 Ma; 1.78 × 1.12 mm), and even more similar to those of the higher placed (Zone J3) localities La Roma 2 (R2, 9.4 Ma, 1.77 × 1.18 mm) and Peralejos C (PERC, J3, 9.05 Ma, 1.72 × 1.16 mm) (zones after van Dam et al., Reference van Dam, Alcalá, Alonzo Zarza, Calvo, Garcés and Krijgsman2001). Morphologically, however, the Spanish J3 populations are advanced with respect to KA2A–45, with M1 often showing a t6–t9 connection and a t1 bis.

Progonomys cathalai Schaub, Reference Schaub1938

Figure 2.5, 2.6, 2.8, 2.9

Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971 Progonomys cathalai; de Bruijn et al., p. 7, pl. 3, figs. 2, 5, 13, 14.

Reference de Bruijn and Zachariasse1979 Progonomys cathalai; de Bruijn and Zachariasse, p. 221, fig. 1.

Holotype

M1 dex. (Montredon 584), upper Vallesian of Montredon, Hérault, France (Schaub, Reference Schaub1938, pl. 1, fig. 8).

Material

M1, KA2A–46; M2, KA3–51, 52, 56, 57; M3, KA3–61; m1, KA2A–79; m1, KA3–71–73, 76–78; m2, KA3–25, 81; m3, KA3–91.

Descriptions

See de Bruijn et al. (Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971). One M1 (KA2A-46) was not described and measured previously. This left M1 is strongly worn off with small parts broken off anteriorly and posteriorly. Its width (W = 1.32 mm) falls within the range of P. cathalai from the type locality Montredon and Masía del Barbo 2B (both with maximum 1.35 mm, n = 33 and 20, respectively; Aguilar, Reference Aguilar1982; van Dam, Reference van Dam1997) but not within the range of P. mixtus n. sp. from K1 (minimum 1.42 mm; Table 1). A right m1 (KA2A–79; 1.82 × 1.12 mm), which was found during the second collection campaign (de Bruijn and Zachariasse, Reference de Bruijn and Zachariasse1979), was also not described previously. This specimen, which lacks part of the buccal anteroconid, differs from the m1 from K3 in the presence of a tma. As this feature is variable in the species (van Dam, Reference van Dam1997), there is no reason to regard the specimen as belonging to a different species.

Dimensions

See Table 1 and Appendix 1.

Remarks

The size of the K2A/3 specimens is indistinguishable from that of the oldest Progonomys cathalai populations from the late Vallesian of central Spain (Zone J2, Teruel Basin; sites Peralejos A, Masía del Barbo 2B, Masía de la Roma 11, La Gloria 14b; van Dam, Reference van Dam1997). For example, the mean length and width in K2A/3 (L × W: 1.77 × 1.10 mm, n = 4) are virtually equal to those in the best-represented Spanish localities (Masía del Barbo 2B and Masía de la Roma 11, 1.77 × 1.08 and 1.78 × 1.08 mm, respectively).

Unfortunately, sample size is too low to draw conclusions on differences in the presence of a tma, which is present on the m1 from K2A (n = 1) but absent on the ones from K3 (n = 3; Fig. 2.5). In the French type locality of Montredon, this cusp is “never well developed” (van de Weerd, Reference van de Weerd1976) or sometimes present as a small cusp (Michaux, Reference Michaux1971). In Spain, it is present in most specimens in the Teruel Basin (53% in MBB and 67% in ROM11; van Dam, Reference van Dam1997). Accepting an ancestor–descendant relationship between Progonomys cathalai and Parapodemus gaudryi (van Dam, Reference van Dam1997), the possession of a tma can be viewed as a derived character, given the standard presence of this cusp in the latter species from the younger Greek locality Pikermi (Chomateri, middle Turolian; de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976). Some caution is warranted, however, as Spanish MN11 specimens of P. gaudryi have a less distinct tma that may even be lacking (van Dam, Reference van Dam1997). Low sample size in K2A/3 also prohibits us from concluding that the percentage of connected anteriorly cusp pairs (50%, 3/6 specimens) is significantly different from the 10–15% observed in the Teruel Basin (van Dam, Reference van Dam1997).

Progonomys mixtus new species

Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971 Progonomys cf. P. woelferi; de Bruijn et al., p. 10, pl. 3, figs. 3–11.

Reference de Bruijn and Zachariasse1979 Progonomys woelferi; de Bruijn and Zachariasse, p. 220, figs. 4–14.

Type specimens

Holotype, left M1, KA1–51 (Fig. 2.7). Paratypes, m1, KA1–11, 172–190, 196–198, 201; m2, KA1–21–22, 31–33, 202–208, 211–223; m3, KA1–41, 231–245; M1, KA1–52, 101–125; M2, KA1–71–74, 131–150; M3, KA1–91–93, 151–168, 171. Type locality, Kasteliana 1 (K1), Kasteliana formation, South Heraklion Basin, Crete (Zachariasse et al., Reference Zachariasse, van Hinsbergen and Fortuin2011). Coordinates: 35º2’44’ N, 25º15’17’ E. Age: 9.3–9.2 Ma.

Material

K1, see: Type specimen section; M1, KA3–11; M2, KA3–14; m1, KA3–21.

Diagnosis

Large-sized Progonomys with a well-developed t4–t8 connection but lacking a t6–t9 connection in M1-2. Spurs present on t1 and t3 in the majority of M1, and occasionally on t1 in M2 as well. Anterocentral cusp on m1 small or absent.

Differential diagnosis

Larger than Progonomys debruijni, P. hispanicus, P. cathalai, and P. woelferi. Morphologically, P. mixtus n. sp. differs from P. cathalai and P. woelferi in the total absence of a t6–t9 connection in M1 and its rare presence in M2, and the common development of spurs on t1 and t3 in M1 and to a lesser degree on t1 in M2. In addition, P. mixtus n. sp. differs from P. cathalai in its stronger t4–t8 connection, and from P. woelferi in its more anteriorly directed t9 in M1. In contrast to P. mixtus n. sp., t6 and t9 are well connected in the smaller-sized Huerzelerimys minor Mein, Martín Suárez, and Agustí, Reference Mein, Martín Suárez and Agustí1993 and similarly sized H. vireti. In addition, spurs on t1 and t3 are only occasionally developed in M1 of H. vireti.

Occurrence

Progonomys mixtus n. sp. is restricted to localities K1, K2A, and K3 in the Kastellios Hill section.

Description

The new descriptions that follow extend on the descriptions in de Bruijn et al. (Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971) and de Bruijn and Zachariasse (Reference de Bruijn and Zachariasse1979). Among other details, they include frequency distributions of spurs on t1 and t3 in M1–2 and of the tma and longitudinal spur in m1.

M1

Cusps rounded. Central cusps t2, t4, and t8 well developed. Chevrons t1–t2–t3 and t4–t5–t6 curved (Fig. 2.7); t1 and t4 placed backward, but not so far as in Occitanomys; t1 bis absent. Spur on t1 often present (63%) and connected to t5. Spur on t3 almost always present (92%) but not necessarily connected to t5; t6–t9 connection absent, although some specimens have a tiny and very low ridge (not scored as a true connection); t9 anteriorly directed; t4–t8 connection always present and shaped as a medium-high ridge, of which the lowest point is close to t4 (as best observed in relatively unworn specimens); t12 small and running downward buccally to the base of t9.

M2

Cusp shape, t4–t5–t6 chevron shape, t4–t8 connection and t12 as in M1 (Fig. 2.14). Spurs on t1 less frequently than in M1 (19%). Spur on t3 absent; t6–t9 connection occasionally present (2/24, i.e., 8%).

M3

Posterior outline rounded. Cusps robust; t1 large and isolated; t3 very small and sometimes ridge-like (Fig. 2.12). In some specimens, the t8 contain a small posterolingual bulge that is homologous with t9.

m1

A small tma is present in 48% of the specimens. (When shaped as a tiny ridge, the structure is not counted.) Connection between anterior cusp pairs present in most specimens (82%). Longitudinal spur absent. Thin and semi-continuous buccal ridge includes a well-developed c1 and, in most specimens, three small, anteriorly placed cusps. Elongated terminal heel placed relatively central (Fig. 2.11).

m2

Anterobuccal cusp usually isolated but sometimes connected to the next, posteriorly placed buccal cuspule (which is attached to the protoconid) by a low ridge (Fig. 2.13). This cuspule and/or a second small cuspule is placed anteriorly to the c1, which is small (Fig. 2.10) and sometimes only present as a ridge (Fig. 2.13). Longitudinal spur absent. Large oval-shaped terminal heel centrally placed.

m3

Anterobuccal cusp ridge-shaped and connected to the base of protoconid in most specimens; c1 variably present (Fig. 2.12). Posterior chevron short and positioned buccally.

Additional description

The level Kasteliana 3 (K3) yielded three more specimens of P. mixtus n. sp.

M1

The single specimen from K3 (L = 2.36 mm, W = 1.60 mm) is heavily worn and has its anterobuccal part damaged. Outline shape corresponding to that of the M1 from K1, but otherwise no systematically useful details of the crown pattern can be discerned.

M2

The single M2 from K3 is damaged posteriorly but otherwise well preserved. Its width (1.63 mm) is second in magnitude across all Kasteliana M2 (n = 20). With t6–t9 separated and t4–t8 connected, the dental pattern remains within the variation of K1. Its shape appears somewhat more anteroposteriorly compressed than that of the K1 specimens.

m1

A corroded posterior part of an m1 from K3 lacks the longitudinal spur.

Etymology

The species name refers to the mixture of primitive and advanced characters in the molar morphology.

Dimensions

See Table 1 and Appendix 1.

Remarks

The lack of a t6–t9 connection in the M1–2 from K1 is a primitive feature in Progonomys that characterizes ancestral populations (e.g., type material of P. cathalai from Montredon; Michaux, Reference Michaux1971). The presence of an anterocentral cusp in about half of the m1 in K1 is a feature that is shared with P. cathalai populations from Spain (van Dam, Reference van Dam1997) but not with the slightly more primitive type material from Montredon, where this cusp is largely absent or very small when present (Michaux, Reference Michaux1971; van de Weerd, Reference van de Weerd1976). In other features, such as overall size, a strong t4–t8 connection, and the development of spurs on t1 and t3, the K1 species is advanced with respect to P. cathalai. Size is larger than that of P. woelferi, the largest Progonomys known thus far. The size difference is especially evident in the upper molars (mean lengths of M1 are 2.35 mm in K1 and 2.19 mm in Kohfidisch; mean lengths of m1 are 2.04 and 1.96 mm; Kohfidisch data after Wöger, Reference Wöger2011).

The large-sized murine from K1 has some resemblance to Huerzelerimys vireti from southwestern Europe. A comparison with the H. vireti populations of Teruel Basin in Spain shows that even larger specimens do occur there (e.g., van Dam, Reference van Dam1997, pl. 2, fig. 10); however, minimum size is approximately the same in the two areas. Differences between Progonomys mixtus n. sp. and Huerzelerimys minor–vireti mostly apply to the upper molars. Both the Greek and Spanish M1–2 have posterior spurs on t1 and t3, although the percentages in M1 are much lower in H. vireti. For example, 10% and 5% of the population of H. vireti from Los Aguanaces 3 have spurs on t1 and t3, respectively, whereas these amount to 63% and 92% in K1. For M2, proportions are low in both sites (5% for both t1 and t3 in Los Aguanaces 3, and 19% and 0% for t1 and t3 in K1, respectively). The possession of these spurs is a relatively advanced feature in the late Miocene evolution of murines (van de Weerd, Reference van de Weerd1976; Adrover, Reference Adrover1986).

More importantly, the t6–t9 connection is absent in the M1 from K1, whereas it is present in 80% of the H. vireti M1 from the Teruel Basin (van Dam, Reference van Dam1997). In the smaller-sized H. minor (assumed to be ancestral to H. vireti; Mein et al., Reference Mein, Martín Suárez and Agustí1993), t6 and t9 are always connected, although sometimes at a low level (in 20% of the M1 of the type population Ambérieu 2C, France). However, the nature of the t4–t8 connection is more similar; it is always present in K1, whereas it is present in 70–80% of the H. vireti populations from the Teruel Basin (van Dam, Reference van Dam1997).

De Bruijn et al. (Reference de Bruijn, Sondaar and Zachariasse1971) and de Bruijn and Zachariasse (Reference de Bruijn and Zachariasse1979) assigned the KA1 population to Progonomys woelferi and not to “Valerimys” (= Huerzelerimys) vireti because of the “absence of a t6–t9 connection” and the “poorly developed accessory cusps in m1 and m2.” Here we retain the assignment to Progonomys but depart from the attribution to P. woelferi. On the basis of the study of Wöger (Reference Wöger2011), who revisited the Progonomys woelferi material from the type locality Kohfidisch, we were able to make a more detailed comparison with the Kastellios Hill material. Besides a larger size, the t6–t9 connection is absent in all specimens from K1, whereas it is absent in 53%, moderately developed in 28%, and strong in 19% of the M1 from Kohfidisch (Wöger, Reference Wöger2011). A key feature is the position of t9, which is anteriorly directed in K1, whereas t9 is “transverse to slightly proverse vs. t8” in Kohfidisch (Wöger, Reference Wöger2011, p. 36). This latter configuration resembles that of P. hispanicus versus the one in P. cathalai, in which the t9 is placed more forward (van Dam, Reference van Dam1997, fig. 3.8). Similarities include the t4–t8 connection, which is always present in K1 and almost always present in Kohfidisch (96%), and the occurrence of posterior spurs on the t1 and t3 in M1, although these are more sparsely present in Kohfidisch (1% on t1 and 26% on t3 in Kohfidisch, versus 63% and 92% in K1, respectively).

Mein et al. (Reference Mein, Martín Suárez and Agustí1993) adopted the assignment by de Bruijn and Zachariasse (Reference de Bruijn and Zachariasse1979) of the K1 material to Progonomys woelferi and considered P. woelferi and H. vireti to belong to two different lineages, a view that is also held here. Supposedly, P. cathalai gave rise to the latest Vallesian Huerzelerimys minor in western Europe, which, in turn, gave rise to the early Turolian H. vireti, which finally evolved into the middle Turolian H. turoliensis (van de Weerd, Reference van de Weerd1976; Adrover, Reference Adrover1986; Mein et al., Reference Mein, Martín Suárez and Agustí1993; van Dam, Reference van Dam1997). A comparable evolutionary development took place in Greece, where P. cathalai could have evolved to P. mixtus n. sp. In contrast to the west, plesiomorphic traits such as the t6–t9 separation were preserved in the east, and more advanced traits such as a strong t4–t8 connection and the presence of spurs were accentuated. Alternatively, P. mixtus n. sp. could have evolved from “Sinapodemus ibrahimi” as originally described from 9.4–9.3 Myr-old sediments in Central Anatolia (Sen, Reference Sen, Kappelman, Sen and Bernor2003; latest synonymization: Progonomys manolo López-Antoñanzas et al., Reference López-Antoñanzas, Renaud, Peláez-Campomanes, Azar, Kachacha and Knoll2019). Like P. mixtus, this smaller-sized species (average length M1 = 1.87 mm) has a well-developed t4–t8 connection, no t6–t9 connection in M1–2, and no anterior cusp in m1.

Despite the presence of several advanced characters such as the large size and the presence of spurs on t1 and t3 in M1–2, the population of K1 fits the diagnosis of Progonomys (Mein et al., Reference Mein, Martín Suárez and Agustí1993). This diagnosis includes the possession of plesiomorphic characters such as the lack of a t6–t9 connection in M1–2 and the absence or small size of the tma in m1. However, the combination of plesiomorphic and more advanced characters necessitates the definition of a new species.

Hansdebruijnia Storch and Dahlmann, Reference Storch and Dahlmann1995

Type species

Occitanomys? neutrum de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976. From Pikermi (Chomateri), Greece.

Other species

H. magna (Sen, Reference Sen1977).

Original diagnosis

The m1 with distinct tma. M1 and M2 with t12. M1 usually without or with poorly developed t1 bis. Stephanodonty poorly developed; a medial ridge on m1 is lacking or weak and short; t1–t5 and t3–t5 connections on M1 are usually lacking and if present, weak and low. Small-sized (Storch and Dahlmann, Reference Storch and Dahlmann1995)

Emended diagnosis

Small-sized murine; t4–t8 connection in M1–2 poorly developed; t6 and t9 connected; t1 in M1 posteriorly placed. Evolutionary trends include size increase and increase of the width/length ratio from approximately 0.65 to 0.71 in M1 and from 0.60 to 0.66 in m1. Morphological tendency in M1–2 to develop a t1 bis, to develop a connection between t1 and t5, to develop a spur on t3 that may reach t5, and to lose t12. Tendencies in m1 include the loss of the tma and longitudinal spur and the development toward rounded borders and a strong buccal ridge with large c1.

Differential diagnosis

Hansdebruijnia differs from Occitanomys in its size, which remains small even during its more advanced stage (H. magna is small with respect to O. brailloni Michaux, Reference Michaux1969). Morphologically, Hansdebruijnia differs from Occitanomys mostly in its lower molars, with all but the most advanced populations at least partly containing m1 with a tma, and all but the most ancestral populations containing m1 with a rounded outline (rather than containing straight or undulating borders as in Occitanomys), and with an anterior part that is wide. Whereas Hansdebruijnia shows a reduction in the formation of the longitudinal spur during evolution, this element is reinforced in Occitanomys (Michaux, Reference Michaux1969; van de Weerd, Reference van de Weerd1976; Adrover, Reference Adrover1986). Upper molars in primitive Hansdebruijnia, for example, H. neutra (de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976) from the type population Pikermi, differ from those in Occitanomys by a smaller width/length ratio and absence of a t1 bis. Upper molars in advanced Hansdebruijnia (H. magna) differ from those in advanced Occitanomys (O. adroveri Hordijk and de Bruijn, Reference Hordijk and de Bruijn2009, O. brailloni) by their smaller size. Castillomys differs from Hansdebruijnia by the better development of longitudinal connections in the lower molars. Castillomys gracilis and C. crusafonti Michaux, Reference Michaux1969 differ from the (time-equivalent) Hansdebruijnia magna by their smaller size.

Remarks

Storch and Ni (Reference Storch and Ni2002) changed the rank of Hansdebruijnia from subgenus (of Occitanomys) to genus, a step that we agree with. In our view, Hansdebruijnia, Occitanomys, and Castillomys represent distinct monophyletic units that start small-sized and evolve distinct morphological trends, with secondary convergence taking place as well (especially in the upper molars). In contrast to Hansdebruijnia, we regard Occitanomys as a strictly southwestern European clade consisting of the lineage O. sondaari–adroveri–brailloni (Spain, France) and its larger-sized, Pliocene offshoot O. montheleni–ellenbergeri (restricted to France; Aguilar et al., Reference Aguilar, Calvet and Michaux1986). In our opinion, eastern populations previously assigned to Occitanomys (e.g., O. adroveri Thaler, Reference Thaler1966 in Hordijk and de Bruijn, Reference Hordijk and de Bruijn2009) should be transferred to Hansdebruijnia. Whereas Occitanomys developed out of Progonomys hispanicus (van de Weerd, Reference van de Weerd1976; van Dam, Reference van Dam1997), Hansdebruijnia probably shares ancestral roots with Parapodemus lugdunensis Schaub, Reference Schaub1938. The origin of Castillomys, supposedly a southwestern European genus as well (Martín-Suárez and Mein, Reference Martín Suárez and Mein1991; Hordijk and de Bruijn, Reference Hordijk and de Bruijn2009), is least known. Its sudden appearance as a very small-sized species in the early Pliocene of southwestern Europe, with both Hansdebruijnia and especially Occitanomys already having evolved toward a larger size, most probably represents an immigration event of which the source area cannot be pinpointed yet.

Excluded from Hansdebruijnia are H. pusilla, H. perpusilla Storch and Ni, Reference Storch and Ni2002, and H. erksinae Ünay, de Bruijn, and Suata-Alpaslan, Reference Ünay, de Bruijn and Suata-Alpaslan2006. “H.” pusilla Schaub, Reference Schaub1938 from MN13-equivalent sites in China (Inner Mongolia) was initially excluded from Hansdebruijnia by Storch and Dahlmann (Reference Storch and Dahlmann1995) but later included by Storch and Ni (Reference Storch and Ni2002). Here we finally exclude the species because its molars are shorter, more brachyodont, and contain smaller and more rounded cusps than H. neutra. Other differences involve the t1 bis, which is typically missing in the M1–2 of “H.” pusilla and the common presence of a t4–t8 connection. In the lower m1–2 of the Chinese species, a prominent longitudinal connection between protoconid/metaconid and hypoconid/entoconid, which is lacking in Hansdebruijnia, is often present. This curved structure connects the hypoconid to the base of the metaconid via the base of the entoconid (Storch, Reference Storch1987).

We also exclude the older (MN11-equivalent) “H.” perpusilla from the same region. Molars of this very small-sized species, of which the scarce type material consists of four specimens and a few fragments (Storch and Ni, Reference Storch and Ni2002), are already relatively broad despite their old age. Moreover, the only complete lower molar (m2) has an outline that is more squared than that of H. neutra, containing a stronger buccal ridge with more prominent c1 (Storch and Ni, Reference Storch and Ni2002, fig. 2.4). “H.” pusilla and “H.” perpusilla probably belong to an East Asian species pool that developed separately from Hansdebruijnia.

“Hansdebruijnia” erksinae from Çorakyerler (Anatolia, MN11/12, most probably MN11; Ünay et al., Reference Ünay, de Bruijn and Suata-Alpaslan2006; Kaya et al., Reference Kaya, Kaymakçi, Bibi, Eronen, Pehlevan, Erkman, Langereis and Fortelius2016) is also excluded from the genus; it lacks the characteristic tma that characterizes the m1 of the contemporary H. neutra. Morphology and size of the upper molars of the species from Çorakyerler are reminiscent of those of Progonomys cathalai, the main difference being a fully grown t6–t9 connection.

Hansdebruijnia neutra (de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976)

Holotype

M1 dex. (PK4–262) from Pikermi (Chomateri), middle Turolian, MN12 (de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976, pl. 4, fig. 10).

Original diagnosis

A small Occitanomys-like murid of about the same size as Occitanomys sondaari van de Weerd, Reference van de Weerd1976. The t4 and t8 of M1 are not connected by a ridge; t1 bis is absent in M1 and M2. The anterocentral cusp of m1 is small and lower than the paired anteroconid cusp (de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976).

Emended diagnosis

Small-sized, relatively brachyodont murine; m1 with occlusal borders that are slightly rounded, with anterocentral cusp, with well-developed buccal ridge, and occasionally with longitudinal spur; t4 and t8 not connected but t6–t9 connected in M1 and mostly connected in M2. M1 with well-developed t12. Evolutionary tendency to form a t1 bis; t1 posteriorly rounded. Minority of M1 with posterior spurs on t1 and/or t3, with spur formation on t3 more frequent than on t1. M2 without spur on t3, but sometimes with spur on t1. Three roots in M2.

Remarks

The original diagnosis by de Bruijn (Reference de Bruijn1976) has been modified to reflect younger, more evolved populations, such as Maramena (Storch and Dahlmann, Reference Storch and Dahlmann1995) and to emphasize the differences from Hansdebruijnia magna.

cf. Hansdebruijnia neutra (de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976)

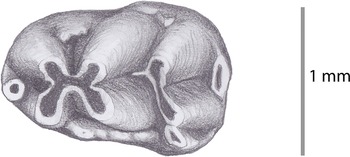

Figure 4. m1 (KA3–74) of cf. Hansdebruijnia neutra from Kastellios Hill.

Material

m1, KA3–74.

Description

A thus-far undescribed murine m1 (KA3–74, 1.67 × 1.01 mm; Fig. 4) is buccolingually symmetric. A distinct and rounded tma is present. Anterolingual cusp, anterobuccal cusp, protoconid, and metaconid form a cross. A small longitudinal spur connects the entoconid with the base of the protoconid. The terminal heel is elongated. The c1 is distinct with three small cusps positioned anteriorly to it. An accessory ridge-like protuberance closes the anteroconid–metaconid valley at its lingual side, and two more protuberances are placed on the down-sloping end of the metaconid–entoconid valley.

Dimensions

See Table 1 and Appendix 1.

Remarks

The specimen has similarities with Hansdebruijnia neutra as well as with Parapodemus lugdunensis. A longitudinal spur is absent in the latter species and, although largely absent in the type locality Pikermi (MN12, de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976), is present in Hansdebruijnia cf. H. neutra from Kalithies (Rhodes, MN12?, de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976, pl. 3, fig. 12; KL-151) and in the H. neutra population from Maramena (MN13–14 transition; Storch and Dahlmann, Reference Storch and Dahlmann1995). The K3 specimen mostly resembles the single m1 from Kalithies, which has a symmetrical shape buccolingually and a broad anterior part that contains a (rolled-off) tma. The Pikermi m1, however (de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976, pl. 4, e.g., fig. 9), have a more asymmetric shape, a smaller c1, and a less well-developed buccal ridge.

Despite the absence of a t4–t8 connection, the M1 from Kalithies (de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976, pl. 3, fig. 13; KL-151) has a slender, Parapodemus-like shape (as also noted by de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976 in his text) with a well-developed t12. Similarity to this latter genus is also evidenced by the m1, which contain a tma and a distinct buccal ridge. Because also the shapes of M2 and m2 of Kalithies are relatively symmetric and slender (de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976, pl. 3, figs. 11, 14; KL-144, 153), we have the opinion that the specimens from Kalithies and the specimen from K3 could represent an ancestral stage in Hansdebruijnia that is still close to Parapodemus lugdunensis. The latter species is pan-European and is also known from the somewhat younger Greek locality Lefkon (de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1989), which has an early Turolian (MN11) age (~8.9–7.7 Ma, van Dam et al., Reference van Dam, Mein, Garcés, van Balen, Furió and Alcalá2023a; see Fig. 1 and the following). The age of Kalithies is not entirely certain; an MN12 age would be consistent with the presence of a gerbil species that probably corresponds to Pseudomeriones pythagorasi Black, Krishtalka, and Solounias, Reference Black, Krishtalka and Solounias1980 as also found in MN12 sites on Samos (Black et al., Reference Black, Krishtalka and Solounias1980; Vassiliadou and Sylvestrou, Reference Vasileiadou and Sylvestrou2009) and a species of Neocricetodon that is very similar to Neocricetodon aff. N. lavocati (Hugueney and Mein, Reference Hugueney and Mein1965) from Pikermi (MN12; de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976). An older age cannot be excluded, however.

Because we are dealing with a single specimen and because it appears to be more ancestral than the type material, caution must be exercised in assigning the m1 from K3 unambiguously to Hansdebruijnia neutra. A “cf. genus–species” designation seems therefore appropriate.

Hansdebruijnia magna (Sen, Reference Sen1977)

Reference Sen1977 Occitanomys magnus; Sen, pl. 1, figs. 1–14, pl. 2, figs. 1–3.

Reference Adrover, Mein and Moissenet1988 Occitanomys alcalai; Adrover et al., p. 100, figs. 1, 1–7.

Reference Hordijk and de Bruijn2009 Occitanomys debruijni (Hordijk and de Bruijn); de Bruijn et al., Reference de Bruijn, Dawson and Mein1970, pl. 2, figs. 1–3, 5, 6.

Reference Hordijk and de Bruijn2009 Occitanomys adroveri; Hordijk and de Bruijn, p. 81, pl. 5, figs. 1–6.

Holotype

M1 dex. (ACA-824) from Çalta, late Ruscinian, MN15 (Sen, Reference Sen1977, pl. 1, fig. 1).

Original diagnosis

M1 with t1 and t3 posteriorly placed with respect to t2 and connected to the garland (“couronne”) by posterior spurs; posterior cingulum reduced, well-developed stephanodonty; in contrast to C. crusafonti (C. = Castillomys), m1 lacks a tma, contains a strong buccal cingulum, and has a very small longitudinal ridge. Size larger than that of C. crusafonti (Sen, Reference Sen1977; translated from French).

Emended diagnosis

Small-sized, slightly hypsodont murine with relatively wide molars. Anteriorly broad m1 with rounded borders and a well-developed buccal ridge with strong c1. It may contain a longitudinal spur. Evolutionary trend toward loss of longitudinal spur in m1–2 and anterocentral cusp in m1; t1 bis almost always present, t6 and t9 strongly connected, t4 and t8 not or weakly connected, and t12 strongly reduced in M1–2; t1 in M1 triangular and connected to t5, and t3 in M1 mostly containing a posterior spur that may be connected to t5; t1 in M2 mostly with spur that connects to t5 but t3 without spur. Evolutionary trend toward the formation of four roots in M2.

Remarks

Differences between “Occitanomys magnus,” “O. alcalai,” and “O. debruijni” are too small to retain these species as separate taxa. Previously, García-Alix et al. (Reference García-Alix, Minwer-Barakat, Martín-Suárez and Freudenthal2008) considered Centralomys benericetti De Giuli, Reference De Giuli1989 to be a junior synonym of “O. alcalai” Adrover et al., Reference Adrover, Mein and Moissenet1988. We believe that the counterargument of Colombero and Pavia (Reference Colombero and Pavia2013) that “From the morphological point of view, O. alcalai differs from C. benericettii in the absence of t3–t5 connections in the upper molars even if the t1 can be connected to the t5” as observed in site Brisighella 25 (Italy, 58%) is not sufficiently substantiated in the type locality (Brisighella 1, few specimens present) and nearby locality Moncuco Torinese (Colombero and Pavia, Reference Colombero and Pavia2013). The fact that the longitudinal spur and anterior cusp in the m1 of the Italian populations are better developed than in the younger (MN14) population Peralejos E (the type population of O. alcalai; Adrover et al., Reference Adrover, Mein and Moissenet1988) merely illustrates the fact that the latter population forms the final stage in a gradual evolution with older (MN13) Spanish Hansdebruijnia populations still partially showing these features (Adrover et al., Reference Adrover, Mein and Moissenet1993; Minwer-Barakat et al., Reference Minwer-Barakat, García-Alix, Agustí, Martín-Suárez and Freudenthal2009; van Dam et al., Reference van Dam, Mein, Garcés, van Balen, Furió and Alcalá2023a).

To examine evolutionary trends in the H. neutra–magna lineage, a direct comparison between key populations was performed on the basis of material from the ESUU collection. This material included H. neutra from Pikermi (PK, Greece, MN12; de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976) and Maramena (MA, Greece, MN13–14 transition; Storch and Dahlmann, Reference Storch and Dahlmann1995), Hansdebruijni (“Occitanomys”) magna from Çalta (CA, Anatolia, MN15; Sen, Reference Sen1977), H. magna (“O. debruijni”) from Maritsa (MR, Rhodes, MN14; de Bruijn et al., Reference de Bruijn, Dawson and Mein1970; Sen and de Bruijn, Reference Sen and de Bruijn1977), and H. magna (“O. alcalai”) from Las Casiones (KS, Spain, MN13; van Dam et al., Reference van Dam, Alcalá, Alonzo Zarza, Calvo, Garcés and Krijgsman2001, Reference van Dam, Mein, Garcés, van Balen, Furió and Alcalá2023a) and the figures and descriptions of the latter form from its type population Peralejos E (PERE; Adrover et al., Reference Adrover, Mein and Moissenet1988).

The population from MA in Greece contains many specimens that are very similar to those of time-equivalent populations from Spain. These similarities include small size, compact molar shape, posteriorly placed t1, development of t1 bis, and spurs on t1 and t3 in M1. In the m1, similarities include a rounded occlusal circumference (without straight or concave borders) and a well-developed buccal ridge. In some characters, the H. neutra population from MA is even more similar to the time-equivalent H. magna in Spain than to H. neutra from PK in Greece. For example, the ratio of average width to average length in M1 is 0.65 in PK, whereas it is 0.71 in both MA and KS. Similarly, a t1 bis is absent in PK, whereas it is present in 60% of the M1 in MA, 97% in KS, and 100% in PERE (as well as in Italian MN13 populations; Colombero and Pavia, Reference Colombero and Pavia2013).

Nevertheless, the population from MA shares more characters with the older type population of H. neutra from PK than with the time-equivalent populations from Spain and Italy. In the M1, differences with the latter areas apply mainly to the t1–t1 bis–t2 connections, the t1 and t3 spurs, and the t12. In some extreme KS specimens, t1 bis is completely isolated from t1, a configuration also observed in MR (de Bruijn et al., Reference de Bruijn, Dawson and Mein1970), whereas in less extreme specimens the t1–t1 bis connection is low. In part of the specimens from KS, the t1 bis is formed as a down-sloping ridge rather than as a cusp. Whereas three out of four M1 from PK have their t1 touching t5 and their t3 containing a posterior spur (which in one specimen reaches t5), the proportions with posterior spurs on t1 or t3 are low in MA, where a connection to t5 occurs in 20% of the specimens (Storch and Dahlmann, Reference Storch and Dahlmann1995). However, the proportion with a spur on t1 is very high in KS (94%), and this spur is always connected to t5. The proportion with a spur on t3 is lower (34%), and it is only rarely connected to t5 (as in MA). The difference in the t1–t5 connection between the M1 in the Greek and Spanish populations is reflected in the shape of the t1: because of the t1–t5 connection, t1 has a triangular shape in KS and PERE (with a straight, anteroposteriorly running buccal face) whereas it tends to be rounded posteriorly in MA. A final difference concerns the t12, which is shaped as a distinct, posteriorly directed protuberance in PK and MA, whereas it is fully integrated in the posterior ridge that connects t8 to t9 in KS and PERE (Adrover et al., Reference Adrover, Mein and Moissenet1988, fig. 1).

In M2, the t1 consists of one complete cusp in PK but is twinned in ~10% of the MA specimens. By contrast, it is twinned in 64% of the M2 from KS and in all M2 from PERE. The t12 in M2 is reduced in all four populations, although a small cusp-like t12 may be present in MA (Storch and Dahlmann, Reference Storch and Dahlmann1995, pl. 2, fig. 37).

The number of roots in M2 (three or four) has been proposed as a useful criterion to distinguish “Centralomys benericettii” (from Brisighella 1, Italy; e.g., Martín-Suárez and Mein, Reference Martín Suárez and Mein1991; here included in Hansdebruijnia magna) from Occitanomys and Castillomys. This criterion could not be fully maintained after the study of more Italian material (García-Alix et al., Reference García-Alix, Minwer-Barakat, Martín-Suárez and Freudenthal2008; Colombero and Pavia, Reference Colombero and Pavia2013). In Hansdebruijnia the appearance of a fourth root appears to be a rather variable character. Although younger (Pliocene) H. magna populations such as PERE (in 20%) and CA (all specimens) developed a fourth root, older (latest Miocene) populations of the same species, such as KS, as well as more advanced H. neutra populations, such as MA, still have three roots.

The width/length ratio of the m1 increases from 0.60 in PK and MA to 0.63 in KS and 0.64 in PERE. Whereas the longitudinal spur in H. neutra from PK and MA is still poorly developed, it is present in 55% of the specimens of H. magna from KS. By contrast, a longitudinal spur was observed by Adrover et al. (Reference Adrover, Mein and Moissenet1988) in only one out of seven specimens in the still younger type population PERE (MN14). The gradual disappearance of the longitudinal spur during the early Pliocene after a late Miocene increase is also evidenced by the population from MR (MN14), where a connection between the two posterior cusp pairs is present in only 2 of 11 specimens in the ESUU collection. Whereas the anterior cusp is distinct in both Greek H. neutra populations PK (MN12) and MA (MN13–14), H. magna m1 from KS (MN13) shows a tiny cusp in only 25% of the specimens (van Dam et al., Reference van Dam, Mein, Garcés, van Balen, Furió and Alcalá2023a). The percentage is similar in Brisighella 25 (19%, also MN13; Martín-Suárez and Mein, Reference Martín Suárez and Mein1991). The tma is absent in still younger populations such as PERE, MR (MN14), and CA (MN15). A morphological trend toward the reduction of accessory elements in the lower molars is therefore evident. This is not true for the c1, however, which remains an important cuspule in Pliocene H. magna, although it is relatively low in MR.

Here we thus propose the existence of the evolutionary lineage cf. H. neutra–H. neutra–H. magna. A migration of H. magna from the eastern to western Mediterranean region at the MN12–13 transition explains its sudden presence in Spain and underlines the importance of long-distance migration in contributing to turnover events in European rodents (van Dam et al., Reference van Dam, Mein, Garcés, van Balen, Furió and Alcalá2023b). Whereas Hansdebruijnia is already relatively advanced in early MN13 in newly colonized areas in Spain (H. magna), it remains more conservative in its source area Greece (H. neutra).

The following trends can be noted for the H. neutra–H. magna lineage:

-

• Size increase in the upper molars with M1 length increasing from ~1.7–1.8 mm in H. neutra to 1.9 mm in H. magna in MN13 (Las Casiones) and 1.95 mm in MN14–15 (Peralejos E, Çalta)

-

• Slower size increase in the lower molars; in Spain m1 length increases from ~1.6 mm to ~1.7 mm, whereas in Anatolia it increases to ~1.8 mm

-

• An increase in the width/length ratio from approximately 0.65 to 0.71 in M1 and 0.60 to 0.66 in m1

-

• An increase in hypsodonty accompanied by an elevation of ridges

-

• A development from absence or moderate development of t1 bis to standard presence in M1–2

-

• A trend from standard presence of the tma in m1 in the Greek sites to presence of a tiny cusp (e.g., in 25% of the specimens in Las Casiones) to total absence (Peralejos E, Maritsa, Çalta)

-

• A late Miocene trend toward an increase of the frequency of the longitudinal spur, which is reversed during the Pliocene, resulting in its total loss

-

• From presence of a strong t12 in M1 and M2 to a smaller t12 in M1 and a final loss of t12 in M2 (in Peralejos E)

-

• An increase from three to four roots in M2

Discussion

Based on Greek mainland data, the age of the Kastellios Hill small mammal fauna is bracketed between that of Biodrak (Athens area; de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1976) and Lefkon (Strimon Basin; de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1989) (Fig. 1.5). The early MN10 locality Biodrak shares various elements with upper Vallesian (MN10) localities in Spain, such as the presence of the MN10 indicator Progonomys hispanicus, the upper MN9 indicator Ramys multicrestatus, and the eomyid Eomyops, which is restricted to uppermost MN9 in the Teruel Basin, central Spain, but extends its presence to MN10 in the Vallès–Penedès Basin (García Moreno and López Martínez, Reference García-Moreno and López Martínez1986; van Dam et al., Reference van Dam, Alcalá, Alonzo Zarza, Calvo, Garcés and Krijgsman2001, Reference van Dam, Krijgsman, Abels, Álvarez-Sierra, García-Paredes, López-Guerrero, Peláez-Campomanes and Ventra2014; Casanovas-Vilar et al., Reference Casanovas-Vilar, Garcés, van Dam, García-Paredes, Robles and Alba2016). The locality Lefkon, however, contains characteristic MN11 elements, such as Parapodemus cf. P. lugdunensis, Neocricetodon (with long mesolophs/mesolophids; de Bruijn, Reference de Bruijn1989) and Crusafontina cf. C. kormosi (van Dam, Reference van Dam2004). Accepting a straightforward biostratigraphic correlation to Spain, the presence of Neocricetodon with long mesolophs/mesolophids would point to a maximum age for Lefkon of 8.7 Ma (van Dam et al., Reference van Dam, Mein, Garcés, van Balen, Furió and Alcalá2023a; Fig. 1).