Introduction

A core issue in third-sector scholarship is the relationship between governments and third-sector organizations (TSOs), as well as what conditions infringe on and support civil society autonomy (Grønbjerg & Smith, Reference Grønbjerg and Smith2021; Marwell & Brown, Reference Marwell, Brown, Powell and Bromley2020). We examine this relationship in a particular subset of cases where local governments attempt to engage with TSOs in which the power and resource asymmetries are enormous: area-based initiatives (ABIs) for urban regeneration in deprived neighborhoods.

ABIs are implemented in cities where a number of social issues need to be addressed to improve social cohesion and raise living standards in deprived neighborhoods (van Gent Musterd & Ostendorf, Reference van Gent, Musterd and Ostendorf2009). The complexity of the “wicked problems” in these neighborhoods demands a coordinated effort to address issues such as employment, physical improvements and social issues. Furthermore, public authorities recognize that public sector efforts are not sufficient and that local stakeholders such as civil society must be engaged (Agger & Jensen, Reference Agger and Jensen2015; Atkinson, Reference Atkinson2008).

In this regard, community development through an ABI is inherently a process of co-production (Agger & Poulsen, Reference Agger and Poulsen2017), understood in a general sense as “a joint effort of citizens and public sector professionals in the initiation, planning, design and implementation of public services” (Brandsen et al., Reference Brandsen, Steen and Verschuere2018). However, we find few contributions that explicitly study co-production in relation to ABIs (see for example Agger & Jensen, Reference Agger, Jensen and Ibsen2021; Vanleene et al., Reference Vanleene, Voets and Verschuere2018).

Indeed, co-production is one of the more ambitious strategies for citizen participation, as it requires a certain level of horizontal participation. Providing that they have equal footing, public employees and citizens can and should work together to improve the living conditions in a certain area (Vanleene & Vershuere, Reference Vanleene, Verschuere, Brandsen, Steen and Verschuere2018). However, in the areas subject to ABIs, marginalized individuals and groups on the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum dominate—groups that are often the most difficult to include in processes of co-production (Brandsen, Reference Brandsen, Loeffler and Bovaird2021). Co-production in ABIs thus constitutes a subset of co-production where power asymmetries may produce different dynamics than what we find in other contexts.

Given the ambitious goals the public sector typically has for ABIs (Gent et al., Reference van Gent, Musterd and Ostendorf2009) and the weak social structures for engaging with the public sector that exist in the affected areas (Agger & Jensen, Reference Agger and Jensen2015), we ask: if and how can co-production be developed in areas with major power asymmetries?

A key aspect of involving citizens consists of engaging TSOs (formal organizations, organized interests, networks, community groups, or charity organizations) working in such areas. Indeed, such collective forms of co-production may be the most impactful simply because they are likely to influence more people (Brudney & England, Reference Brudney and England1983, p. 62). Moreover, as Ibsen (Reference Ibsen and Ibsen2021a, Reference Ibsen and Ibsen2021b, p 4) notes, in the Scandinavian context, co-production most prominently refers to the relationship between the public sector and voluntary organizations, not the end user. Furthermore, Jensen and Agger (Reference Jensen and Agger2022) argue that collaboration with voluntary organizations is a possible way to gain access to groups hard to reach. Nevertheless, existing research gives limited insight into collaboration between TSOs and authorities within ABIs.

Thus, the public sector approach toward ABIs consists of reaching centrally defined goals for the public sector, while also inviting TSOs to co-produce on equal terms. This approach takes place in areas where the organized civil society is weak, and the public sector has special interests and a willingness to use resources. To examine if and how co-production can take place under these conditions, we apply a qualitative design consisting of document studies and interviews. First, we investigate if and how co-production is used as a strategy in policy documents and in the goals and practices described by public administrators. Second, we examine how representatives of voluntary organizations and the public sector assess the contribution of TSOs to the actual processes and outcomes of ABIs. Norwegian ABIs typically focus on labor market inclusion, improving conditions for youth growing up, both socially and in their education, and community development. It is especially concerning the two latter ambitions that TSOs play a role.

Norway is an ideal context for studying the potential for co-production in ABIs, as the country is characterized by a strong, expansive state that involves itself in many spheres of society. At the same time, the country has a vibrant civil society that commands considerable power both as a partner with and an opponent to the state (Enjolras & Strømsnes, Reference Enjolras, Strømsnes, Enjolras and Strømsnes2018). This aspect of civil society is, however, not prominent in the areas subject to ABIs, but these same areas are also where the state lacks instruments to spur social change. It thus remains to be seen if the powerful state will overrun civil society or engage in co-productive partnership in these areas.

Our study thus contributes to the literature on the relationship between governments and third-sector organizations in general and specifically on co-production and third-sector organizations within ABIs. Our findings are particularly relevant for understanding the role of power in co-production and how different sources of resources may empower the state and TSOs differently.

Co-production or TSOs as Public Sector Instruments

As ABIs are developed to address complex collective action problems, demanding efforts from a variety of actors, they constitute what Ostrom (Reference Ostrom and Salih2009) labels polycentric governance, involving different centers of decision-making and authority. This means that the government cannot always alone impose its authorities on policies, nor can it muster sufficient resources to solve the problems. Conversely, authorities can often engage with community actors such as TSOs at a horizontal level, enabling deliberation, joint decision-making and activity. However, such constellations may be vulnerable to domination or capture by powerful interests (Carlisle & Gruby, Reference Carlisle and Gruby2019), such as the state that can thus undermine the polycentric approach to problem solving.

Co-production is an approach to collective problem solving through polycentric governance in ABIs. The definition of co-production is contested, as different authors include different actors, different policy phases and different activities in the concept (Nabatchi et al., Reference Nabatchi, Sancino and Sicilia2017). Our interest is in co-production between formal organizations and the public sector through municipal agencies and ABIs. We are interested in both the planning phase and the implementation of services, and we have an inclusive approach to activities that contribute to community development in a broad sense. This entails that sports activities, care services for the elderly and the development of housing strategies are all activities that are relevant for our understanding of co-production in ABIs.

In the context of our study, the issue of power in co-production relationships is central. In the literature, one can find co-production defined exclusively as an equal relationship between the actors or as one where inherent power imbalances between actors prevail (Bovaird & Loeffler, Reference Bovaird and Loeffler2012). While truly equal relationships are difficult to achieve in the sphere of public administration, there is a relevant distinction between a co-productive relationship and TSOs becoming mere instruments to reach public sector goals (Alford, Reference Alford2009, p. 22; Ewert & Evers, Reference Ewert and Evers2014). We therefore argue for a distinction between co-production of ABIs as a public management strategy (see e.g., Strokosch & Osborne, Reference Strokosch, Osborne, Loeffler and Bovaird2021) and the co-production of actual ABI processes and outcomes. This issue is particularly evident in ABIs, in which power and resource asymmetry between government and TSOs is very much present (Tõnurist & Surva, Reference Tõnurist and Surva2017, pp. 241).

While the state possesses, for example, professional staff, infrastructure and funding, the TSOs also potentially have relevant resources in the form of local embeddedness, access to minority groups and trust from the residents in the area. Access to scarce resources is one potential source of power in the relationship between TSOs and AIBs. The different TSOs may, however, engage with the public sector in different ways. For instance, Jensen and Agger (Reference Jensen and Agger2022) explain how different forms of voluntarism have different functions in ABIs. Social voluntarism, which is directed toward people outside the organization, e.g., charity organizations helping vulnerable citizens, can provide access to the disadvantaged and anchor initiatives in a way that secures that initiatives continue after the ABI. Civic voluntarism encompasses interest-based activities for the organizations´ members and can promote participation and voluntary work, empowerment and the anchoring of initiatives. In assessing the co-production in ABIs, one must therefore consider the variation between different forms of TSOs.

To assess whether co-production is dominated and/or captured by the state or if horizontal, shared governance is achieved in the context of ABIs, we can examine the role of managerial ability and coordination, financial and other resources, and autonomy. As we explain below, these aspects are particularly relevant in a context with an uneven distribution of power. Managerial ability is needed as the involved parties enter the co-production with different rationales for participation and policy agendas (Filipe et al., Reference Filipe, Renedo and Marston2017). Particularly in ABIs, where TSOs often lack organizational expertise and personnel both for internal coordination and external engagement, it is crucial how the organization manages to be a partner for the public sector. Developing administrative structures, processes and—importantly—coordination of the interaction between public agencies and voluntary organizations is therefore important (Sorrentino et al., Reference Sorrentino, Sicilia and Howlett2018). This can also involve coordination among voluntary organizations, as a certain organizational capacity is needed for them to engage with the state on an equal footing.

Financial and other resources are central in the literature on resource dependency. Dating back to Pfeifer and Salancik (Reference Pfeifer and Salancik1978), the main argument put forward is that as TSO dependence on public funding or other resources increases, the more influence the public sector can exercise in its relationship with the TSO. At the same time, Marwell and Brown (Reference Marwell, Brown, Powell and Bromley2020, p. 246) argue that in certain situations, the distribution of resources may be turned upside down, as TSOs have resources unavailable to the state. This may be particularly relevant for ABIs, as these are established precisely because the ordinary operations of the public sector are deemed insufficient. As the government is increasingly dealing with social problems that are not possible to solve by traditional hierarchical regulation and control, new tools are sought, and TSOs are increasingly seen as a part of the toolbox.

Following Enjolras and Trætteberg (Reference Enjolras, Trætteberg and Ibsen2021), we contend that a certain level of autonomy of action is a prerequisite for co-production. If the relationship becomes too hierarchical, one actor may be in a position to order the other, at which point we may speak of public sector contracting or orchestration. This means that even if the state depends on TSO resources such as trust from residents or access to minority groups, this does not necessarily empower the TSO all that much. If TSOs are to be more than public sector policy instruments, they need to have autonomy to set their own, independent goals. One way to evaluate the autonomy of action in co-production is to identify which actors initiate the co-produced efforts. If TSOs take this role, it is an indication of their autonomy of action (see Stougaard, Reference Stougaard2021; Pestoff, Reference Pestoff2012).

While interrelated, managerial ability and coordination, financial and other resources, and autonomy do not have a fixed relationship. For example, a high score on TSO autonomy does not necessarily predict a certain score on managerial ability. This reflects the complexity of co-productive relationships. Rather, this should be understood as three dimensions along which we can examine the co-production in ABIs. Together with the issue of co-production being a governance strategy or a description of actual processes and outcome, they thus constitute a set of four continuous dimensions we can use to assess whether the relationship between the public sector and TSOs in ABIs is a matter of co-production or if it is a matter of the public sector using TSOs as a subordinate policy instrument.

Area-Based Interventions in Norway

A 2018 survey study among public sector professionals in Norwegian municipalities found that voluntary–municipal collaborative relations in Norway are extensive, especially within the fields that are relevant for collaboration with government actors in ABIs (Eimhjellen, Reference Eimhjellen and Ibsen2021). While these findings provide a useful overview of the municipal–TSO relationship at the general level, we are not aware of any studies from the Norwegian context that have examined this relationship in areas subject to ABIs, despite this relationship being a major emphasis for state and local authorities. Indeed, according to Agger and Jensen (Reference Agger, Jensen and Ibsen2021, p. 294), co-production within urban regeneration has hardly been studied.

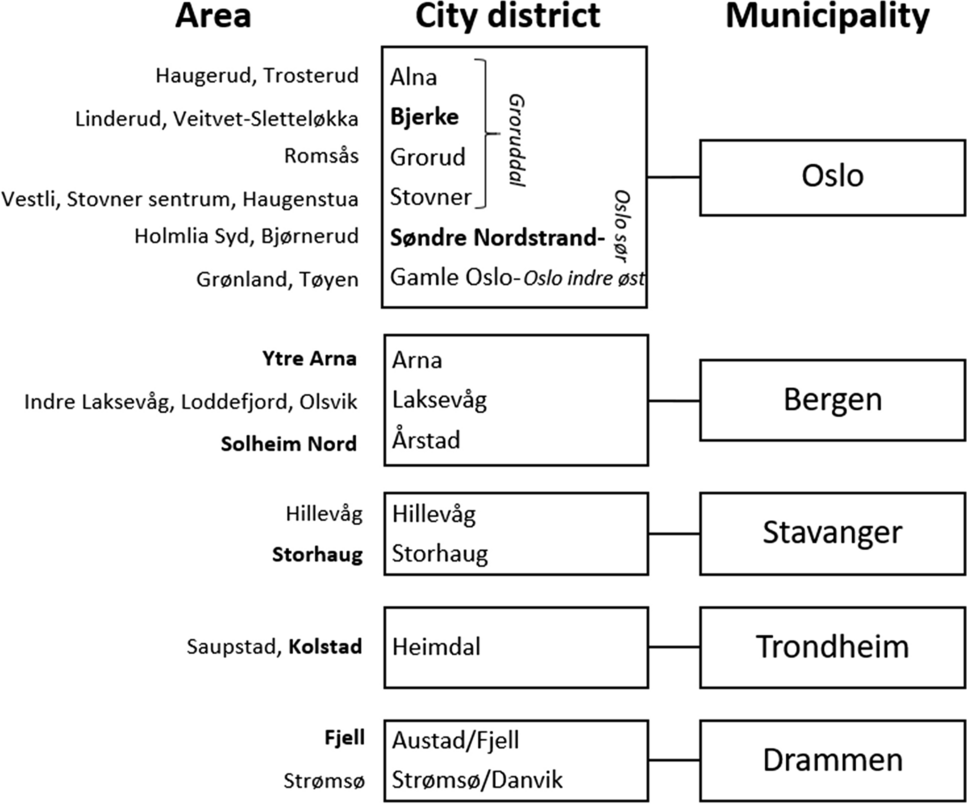

Compared internationally, ABIs as specific strategies for urban regeneration have a rather short history in Norway, starting in the area of Grorud in Oslo in 2007 and later implemented as strategies in other cities with socioeconomically deprived areas. Oslo has had several programs for city renewal since the 1970s but no large and long-term initiative such as an ABI until recent years. Figure 1 offers an overview of ABIs in Norway, with the ones included in our study marked in bold. Although several Norwegian ABIs have been evaluated (e.g., Rambøll, Reference Rambøll2020; Ruud & Vestby, Reference Ruud and Vestby2018), the literature provides limited knowledge regarding how the voluntary sector is involved, what strategies governments apply, and how voluntary actors consider their role in these ABIs.

Fig. 1 Overview of ABIs in Norway

Methods and Data

We conducted a qualitative comparative case study of seven ABIs in all five Norwegian cities that have such efforts. Therefore, we covered all municipalities that have ABIs in Norway. We pursued a qualitative strategy partly because information about the actors that constitute the universe of relevant TSOs does not exist, making quantitative strategies difficult, and partly because we wanted thick descriptions and reflections about the relationship between TSOs and the public sector.

We pursued a threefold strategy. First, we conducted a thorough review of all documents concerning ABIs. This includes research papers, municipal strategy documents, and internal and external evaluations. From the public documents, we assessed how the public sector formally sees its relationship to TSOs within the framework of ABIs. Second, we interviewed representatives from the public sector working in ABIs. This gave us insight into how the public sector engaged with TSOs in practical terms. Third, we interviewed representatives from the TSOs. A central aspect of our analysis was to triangulate insights from these three sources.

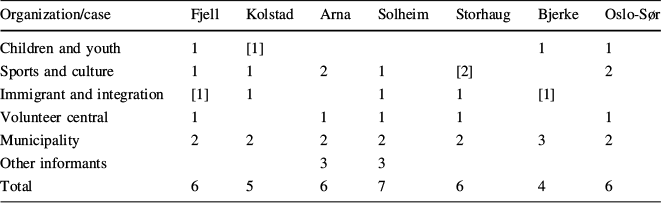

To secure input from the range of different types of TSOs, we aimed to identify and interview representatives of voluntary organizations within sports and culture, children and youth, and immigration and integration. We selected based on policy fields because we expected the relationship between the public sector and TSOs to vary according to policy fields (Stone & Sandfort, Reference Stone and Sandfort2009). Furthermore, in the Norwegian context, policy fields tend to correlate with the type of organization. For example, in culture and sports, we find many formal, well-established organizations, while in integration, we see more informal community groups. In some cases, however, it proved difficult to identify organizations in all three categories. We then identified alternative organizations or arenas that could partly function as substitutes for the missing organizations. As an example, in ABIs, some sports clubs take on a wide responsibility for their community, including hosting youth clubs. When an organization exclusively devoted to youth and children was missing, we asked sports clubs and volunteer centers about these aspects of their operation. Table 1 gives an overview of interviewees per ABI and policy area. The category “other informants” refers to active individuals in the communities that have engaged with ABIs and to local community development incubators established in the concerned municipalities.

Table 1 Overview of informants

Organization/case |

Fjell |

Kolstad |

Arna |

Solheim |

Storhaug |

Bjerke |

Oslo-Sør |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Children and youth |

1 |

[1] |

1 |

1 |

|||

Sports and culture |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

[2] |

2 |

|

Immigrant and integration |

[1] |

1 |

1 |

1 |

[1] |

||

Volunteer central |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

||

Municipality |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

Other informants |

3 |

3 |

|||||

Total |

6 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

6 |

4 |

6 |

[brackets] indicate interviews conducted with an organization that does not fully fit the category

In total, we conducted 15 interviews with public employees and 25 interviews with representatives from TSOs. The public sector interviewees are typically employed by the municipalities to work specifically with the ABIs, and we approached those working with the civil society development component of the efforts. The representatives of voluntary organizations were leaders at different levels or people involved in activities connected to ABIs.

We conducted semi-structured interviews with 4–7 persons in each ABI. The interviews were conducted during the COVID pandemic, which made digital interviews an obvious choice, although we also carried out a few face-to-face interviews. Informants received an overview of possible questions in advance. The interviews were conducted by either one or two researchers and typically lasted approximately 1 h. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. One of the researchers coded the interviews with theme codes in NVivo, securing consistency in coding. The relevant codes for this article centered on “form of TSO involvement in the ABI” to capture autonomy to act, “communication and coordination by the ABI staff” and “collaboration/competition among TSO” to cover managerial ability and coordination, and “dependencies on ABI” and “strategies for TSO contribution” to cover resources. Additionally, we inductively developed codes such as “facilitators for co-production” and “inhibitors for co-production”.

Findings

Following the theoretical discussion above, we start by (1) examining policy documents and interview material to assess whether co-production is perceived as a governance strategy. Thereafter, the interviews were analyzed with respect to three main dimensions: (2) managerial ability and coordination, (3) resources, and (4) autonomy to act. Additionally, we discuss (5) the differences between different types of TSOs. We do point out some discrepancies between the cases when these are relevant for the conclusions, but overall, it is striking the extent to which the same pattern manifests across the different ABIs on the core dimensions for our research question. This implies that there are general institutional features that explain the patterns and suggests that we have robust conclusions.

Co-production as a Governance Strategy?

The concept of co-production is not used much in policy documents, whereas terms such as collaboration or partnerships occur extensively. This is somewhat surprising, as other studies have shown that Norwegian municipalities ideologically embrace transnational movements that try to incorporate civil society in solving public sector tasks (Guribye, Reference Guribye2018) and that co-production is one such strategy that has achieved national backing (Torfing et al., Reference Torfing, Sørensen and Breimo2022). However, this is not necessarily an expression of co-production being irrelevant as an empirical phenomenon; instead, it may be that the municipalities are not familiar with the particular concept.

TSOs are emphasized as important actors in all seven ABIs. All five municipalities have their own voluntary policy that in all cases emphasizes the independence and autonomy of the voluntary sector and how the municipality should provide support on the voluntary sector’s terms. The fact that authorities present TSOs as important actors in all seven ABIs we studied can be interpreted as, to some extent, TSOs being instrumentalized by authorities to reach ABI goals. One example from an annual report in Oslo is how the involvement of civil society is said to be crucial if activities established during the ABI are to continue after the ABI, when extra resources are no longer available (Oslo kommune, 2020). This is similar to what Jensen and Agger (Reference Jensen and Agger2022) refer to as anchoring.

However, this can also be interpreted as the public sector aligning their interests with those of civil society and that public documents thus present TSOs more as partners than instruments, although the role ascribed to TSOs varies across ABIs. For example, according to government documents concerning the ABI in Trondheim that were published in its initial phase, the lack of a collaboration forum for voluntary and public actors has resulted in overlapping, competing activities. Thus, “there is a need for more collaboration and coordination without a character of overruling or control” (Trondheim kommune, 2013, p. 16). Furthermore, a handbook published by Oslo municipality describes the involvement of TSOs in ABIs as crucial for ensuring that municipal resources are devoted to actual needs and wishes and to promote “community empowerment” (Oslo kommune, 2016, p. 28). Indeed, the view that co-production is beneficial for community development was widely held in the public sector staff in all municipalities.

Practically all the interviewed representatives of the public sector share this respect for TSO autonomy that we identified in the documents. Of course, it is possible that the public sector staff gave these answers because they are familiar with the official public policies and want to align themselves with this viewpoint. However, the fact that this response is uniform across all 12 interviewees suggests that this is not the case. Furthermore, the interviews with TSO representatives largely corroborate this view. We find this somewhat surprising. That is, public sector staff are hired to create social change in these deprived areas. Co-production with TSOs is one of the instruments available to achieve such change; therefore, public sector staff have strong incentives to try to steer TSOs in a desired direction. However, as the evidence shows that the staff do not do so, this suggests that a strong culture of TSO autonomy exists. Overall, we find that TSOs are considered co-production partners to a higher degree than the limited role Jensen and Agger (Reference Jensen and Agger2022: 301) find in Denmark.

Managerial Ability and Coordination

One general feature that representatives from TSOs emphasized is the challenge of coordination, both between TSOs and in relation to the public sector. A solution that several TSOs embraced is to have a dedicated paid coordination position in the municipality. As a representative of a TSO noted, “It’s not the facilities that matter the most; it’s the persons.” This role would require solving tasks outside the role of the traditional bureaucrat, working on the terms of the volunteers, meaning outside regular day-time working hours, since the relevant volunteer activities often take place in the evenings.

The volunteers support public sector coordinators to arrange meetings on a regular basis with the involved TSOs and the public to “anchor” the activities of the ABI in the community and to facilitate information flow regarding the possibilities for activities that the ABIs represent.

In the same vein, the interviewed public sector employees explained how the TSOs rely on the public sector regarding training, development of competences, and coordination. In many instances, the employees described the functioning of coordinators who facilitate meeting points for different TSOs, as there are TSOs with relatively weak institutional structures and abilities to meet others. The parts of the ABIs that concern the physical infrastructure have in some places resulted in community houses where TSOs can hold meetings and recruit new members. In these cases, ABI has served the interests of TSOs without necessarily demanding any form of activities as a prerequisite.

Overall, it is a shared perspective among interviewees from the TSOs and the public sector that coordination of activity is an important role of the public sector in the ABI. They coordinate cooperation among TSOs and facilitate interaction between TSOs and the public sector. The need for such coordination varies according to the different TSOs. While some have considerable management capacity within their organization and see public sector coordination as an added value they do not depend on, other organizations also need help with their internal coordination.

Resources

The general perception of the public employees interviewed is that there is a clear interdependence between the TSOs and the public sector. In addition to some TSOs needing help with coordination, a central part of the relationship is financial. ABIs allow access to financial funding and support for organizations and for concrete organizational projects. This includes direct access to funding through the ABI, as well as access to other sources of funding elsewhere in the public bureaucracy. For many TSOs, this is a primary motivation to engage with the ABIs, something this representative of a voluntary organization illustrates:

I thought that here we must try to […] profit from the fact that we have got the municipality in via the ABI and that way it must bring in some money. Because money is alpha and omega, if you want to achieve something, you have to have it.

On their side, the TSOs also offer three unique resources. The first is the matter of access to parts of the population. That is, public employees find it difficult to access and engage with people living in the area. This is due to both socioeconomic conditions and to the citizens in the areas being immigrants who may have more trust in a TSO than in the public sector.

An indirect way for the public sector to reach these citizens is for TSOs that receive funding to include more citizens (e.g., by subsidizing membership fees that allow low-income families to participate or subsidizing costs for instructors to enable TSOs to organize activities for children where it has proved difficult to recruit parents as volunteers, as is the norm in other parts of the country). In such instances, the TSOs may be instruments to achieve public goals of increased participation, yet without experiencing this as a threat to their independence and autonomy. The TSOs’ view on dependence or interdependence in this setting is rather similar to that of public administrators, where both actors work together on “an equal footing” (Vanleene & Vershuere, Reference Vanleene, Verschuere, Brandsen, Steen and Verschuere2018).

The second unique resource of the TSOs is knowledge about the local community. The public sector—and indeed the national and political level—is dominated by higher educated middle-class individuals from the majority population. These employees may therefore lack knowledge about “what is going on in the areas.” In the words of a public employee:

It is especially important to have volunteers, as they know what is going on in an area. That you get the bigger picture: that is, with different challenges and possibilities in an area. We may very well have an understanding or expectation, or we may think and have opinions, and then when you talk with people and the local community you get a much more nuanced picture and maybe you are surprised and have new thoughts or suggestions that one had not thought of before. That happens often in my opinion. I consider participation to be of great importance.

Third, TSOs can mobilize resources needed to achieve social change (Jensen & Agger, Reference Jensen and Agger2022). The part of the ABIs that concern social development and social capital consist of just a couple of employees in each ABI. These employees thus recognize that to spur development and social change, they depend on civil society structures. TSOs are therefore instrumental in mobilizing latent resources and anchoring the efforts of the ABI in the local community.

Overall, there are clearly mutual dependencies between the TSOs and the public sector within ABIs. The interdependence does not, however, apply to all relationships. While the public sector depends on certain TSOs to engage with citizens, these are often different from the TSOs most apt at mobilizing resources. Likewise, while some TSOs are fully dependent on support from the public sector, others see this merely as a pleasant bonus they do not depend on.

Autonomy to Act

Which actors initiate the co-produced activities is an indicator of the power relationships and dependency structures. There was a certain tendency in the data that the organizations perceived the ABIs as the active initiators for collaboration, who suggested projects and brought relevant actors together, invited participation in concrete projects, and invited dialog about problems and challenges to be solved. Some organizations pointed out that the ABIs had informed them of their own plans and invited them into their own projects, which was clearly more than inviting a dialog on defining the problems to be solved and developing projects together. Organizations also highlighted that ABIs had raised concerns about challenges in specific areas in an attempt to create shared perspectives on local challenges. At the same time, several TSO interviewees pointed out that the initiatives for collaboration on and initiation of projects came from government actors and voluntary organizations alike. These interviewees perceived ABIs as important supporters for the organizations, reinforcing and securing continuity in their activities and projects.

We see some differences between the municipalities. For instance, in one municipality, civil society actors played a more central role in designing the content. For example, when voluntary organizations and residents were invited to apply for funding from a grant scheme (Ruud & Vestby, Reference Ruud and Vestby2018, pp. 5–6), the district council consisting of volunteers distributed resources rather than letting a project administration manage the ABI funding stream. This ABI thus ascribes a particularly strong role to TSOs and constitutes another example of how TSOs have autonomy to pursue their own interest in interactions with the ABIs.

Differences Between Different Types of TSOs

From the interview material, we may distinguish between three categories of TSOs: (1) volunteer centers; (2) established TSOs; and (3) newly founded TSOs. Volunteer centers can be owned by the municipality or a group of TSOs, but have in all cases paid staff financed by the public sector. Established TSOs have an institutional foundation that has enabled them to exist over time. These actors typically have a substantial number of volunteers, sometimes a paid administrator and normally a functioning democratic structure. Newly funded TSOs are typically small, sometimes informally organized and often dependent on public sector support. The different types of organizations were somewhat divergent in their views on their own roles and functions in the ABIs.

The volunteer centers, although operated by voluntary actors, can be seen as hybrid organizations (Billis, Reference Billis2010), positioned somewhere between the voluntary sector and the public sector. The interviewees from the volunteer centers expressed a particular ownership and proximity to the particular local challenges to be solved through the ABIs. Having a paid position (through a public grant), they saw themselves as having a particular responsibility and viewed the ABIs as valuable support for meeting the challenges in the area. The ABI was useful for them, bringing in new ideas, securing the completion of projects, and creating networks of relevant actors. An interviewee described the collaboration with the municipality as very productive and involving shared responsibilities, while in another city, a volunteer center representative was not satisfied with how the ABI included the voluntary and citizen perspective in the ABI, with too much of a top-down management strategy. The representative viewed the volunteer center as a central link between the citizens in the area and the governance system. These hybrid actors thus have a varied set of experiences in how the co-production works.

Among the established organizations, all interviewees described sports clubs as dominant actors with many members, a sound economy, and a record of accomplishment over time. Indeed, in some of the areas, the sports clubs were the only organizations with institutional ability to act independently. In other places, there were also other organizations (e.g., the Red Cross) that belonged to this group of established organizations. These organizations viewed the ABIs as important financial sources and collaborating partners for maintaining activity and establishing new activity for local citizens. While these associations embraced the partnership with the ABIs, they expressed some discontent when the ABI made financial priorities that did not benefit their particular organization.

While the public sector employees felt that larger TSOs have untapped potential, TSOs are often not interested in expanding their activities in a new direction in some form of mission drift. The representatives from the AIBs have a dual approach to how desirable this is, as this representative exemplifies:

We focus on sports teams and their role as local community actors. There are many people [in the sport clubs] who are good at seeing the responsibility that they have. However, we constantly clarify that it is they who must define the needs and implement the measures.

Indeed, some organizational representatives mentioned that collaboration with ABIs had opened their eyes to the societal role and social responsibility that the associations had; in some cases, the organizational representatives had even expanded the repertoire of activities in the organizations accordingly (but not against the will of the organizations).

Newly founded organizations complemented the roles played by volunteer centers and the established organizations, at least in the view of public sector officials. To engage with organizations that explicitly work for the social change sought in the ABIs, the public sector tries to co-produce with newer initiatives that do not have the same institutional footing as the more established organizations. In collaboration with ABIs, several new voluntary initiatives and organizations have been established. For these types of initiatives, the ABIs have been central initiators and supporters of activity. Here, ABIs have provided competence and guidance in the establishment and operation of organizations. In some cases, the ABIs have initiated and used such organizations to establish contact with and gain information from certain subgroups, such as minority youths. The organizations have been used to reach out to and communicate with such groups to attain information on their needs and challenges in the neighborhood. Although these groups are often included in decision-making processes, the authorities make the main decisions, while the organizations function as a voice for different subgroups and their needs and perspectives.

Interviewed employees in all municipalities described the role of individual volunteers, both inside and outside of TSOs, as crucial. This sometimes invites questions about the relevance of the smaller TSOs, since in some cases and for practical purposes, they are driven by the efforts of single individuals. At the same time, some public employees worry that these core volunteers may get an undue influence over the public sector–civil society co-production, as much attention is directed toward their interests.

Additionally, in public employees’ relationships with larger organizations, the issue of representativity appears. Leaders in TSOs are generally more educated and possess more resources than many of the citizens in the areas of concern. By directing much of their attention to the interests of these TSOs, the public sector thus risks not having enough resources for citizens with fewer resources.

Concluding Discussion

We asked if and how co-production can take place in ABIs with major power asymmetries. While co-production was generally not prominent in the policy documents, the interviews showed a wide diversity in the extent to which the public sector staff thought of co-production as their strategy for engaging with TSOs. However, we could not find any relationship between the propensity to see co-production as a strategy and the actual practices we observed.

Our interview data from the public sector side show a surprisingly conscious approach to the role of TSOs. When the public sector officials are torn between respecting TSO autonomy or pushing for their own form of social change, they uniformly claim to be on the side of TSO autonomy. The reviewed documents underline the importance of civil society autonomy and that the interaction between the public sector and civil society should not infringe on the goals and means defined by the TSOs themselves.

Interestingly, the representatives from TSOs do not show the same level of consciousness regarding these overarching issues. Rather, they are concerned with the practical operation of their organizations. However, the representatives mostly reflect the positive attitude toward the co-producing efforts, and we can conclude that the public sector and TSOs share a positive view of how they co-produce benefits for the population.

ABIs are characterized more by an uneven distribution of resources than by asymmetries in power. Both the TSO and the public sector have resources that the other party needs, creating a sense of mutual interdependence. The municipality is dependent on TSOs to gain access to areas, identify needs, and mobilize residents, thereby creating long-lasting collaboration structures. As one interviewee put it, “the public sector simply cannot ask people to volunteer; then we will “get a regular scolding.” At the same time, some TSOs need public coordination and financial support to carry out activities. Thus, the relationship is best described as interdependence between the TSOs and the public sector, whereby both parties find each other useful and practical.

We analyzed our data along three dimensions: managerial ability and coordination, autonomy to act, and resources. It seems that it is the latter dimension that plays the biggest part in determining the relationship between TSOs and the public sector. When needed, the public sector helps TSOs achieve managerial ability to coordinate and autonomy to act, and their greatest incentive to do so is the potential resources of these TSOs. It is thus resources that mostly mediate the power balances between TSOs and the staff in ABIs.

Representativity is a pervasive issue in ABIs that is challenging to handle in the co-production process. We found a consistent pattern regarding two main relationships between the public sector and TSOs.

First, leaders stemming from the majority ethnicity in the Norwegian population typically dominate the established TSOs. These organizations exist independently of ABIs and have influence in the area based on their share size. Even if they are not dependent on the public sector to carry out their activities, they seek access to public resources such as money and potential members in schools through ABIs. The public sector engages with these organizations, as they are the largest and most influential organizations in the area. At the same time, these organizations are often not the agents for social change that the public sector prefers to engage with within the frameworks of the ABIs. Thus, their dominant position also makes the ABIs cement the social structure in the area, as the citizens with most resources are also the ones benefiting most from the ABIs.

Second, this issue of representativeness is well known for the public sector and something they seek to remedy. Therefore, we also found TSOs dominated by representatives of a minority ethnicity and typically engaging in youth work or various integration efforts. These newly founded TSOs are sometimes established in close collaboration with the ABI staff and will often depend on ABI support. A core aim of ABIs is to engage with the parts of the population that these organizations stem from and that the state is otherwise unable to reach. Often, these organizations will consist of a single volunteer or a few volunteers. Consequently, these few volunteers are given a central position through co-production with the ABI because they are assumed to represent wider minority interest, even if the democratic structures that normally justify this kind of representation do not exist.

Faced with this situation, the public sector interviewees felt it is their task to influence the organizations to widen their perspectives and function more as engines for broad social development, rather than mere sports clubs or help groups for the weakest citizens. Despite the employees repeatedly stressing the autonomy of TSOs, they have no reflection about mission drift or how public sector economic incentives may drive changes in TSOs. The newly founded TSOs are most malleable. As they may have been founded by the ABI or in close cooperation with the employees, their interests and values are thus better aligned. Accordingly, TSOs’ role as civil society actors is less relevant than the service they may provide to their members and external target groups.

Our findings are based on qualitative data from one context, the Norwegian context. Statistical generalization to other contexts is accordingly not possible. However, we do expect the relationship between different sources of resources to be relevant in co-production in deprived areas in large cities in other Western countries. For example, Van Eijk and colleagues’ (Reference Van Eijk, Van der Vlegel-Brouwer and Bussemaker2023) study of deprived neighborhoods in the Hague, the Netherlands, corroborates some of our findings, such as the autonomy of action of citizen initiatives, the importance of trust, and the possible role of key community members as boundary spanners. Additionally, in Denmark, Jensen and Agger (Reference Jensen and Agger2022) see potential for using TSOs to engage with vulnerable citizens. We therefore believe our article makes an important contribution to understanding the dynamics that enable co-production between TSOs and the public sector in areas subject to ABIs. Going forward, we call on reach on the issue of how power differences influences TSO-public sector co-production in more contexts. Additionally, much of the existing research on this topic is based on qualitative sources, and more quantitative approaches are therefore needed.

Funding

Centre for Research on Civil Society and Voluntary Sector

Data Availability

The data are not publicly available due to ethical, legal, or other concerns.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

This study has been approved by the Data Protection Services of the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research.