1. Introduction

Interdisciplinary understanding is an important foundation for producing robust scientific advice for policymakers and government officials on complex issues, such as climate change (Bammer et al., Reference Bammer, O'Rourke, O'Connell, Neuhauser, Midgley, Klein, Grigg, Gadlin, Elsum, Bursztyn, Fulton, Pohl, Smithson, Vilsmaier, Bergmann, Jaeger, Merkx, Vienni Baptista, Burgman and Richardson2020; Gluckman et al., Reference Gluckman, Bardsley and Kaiser2021). However, navigating the immense and rapidly expanding body of climate change literature, and identifying the most important developments is increasingly difficult, due to the sheer volume of yearly scholarly publications, and the diversity of topics and disciplinary perspectives (Callaghan et al., Reference Callaghan, Minx and Forster2020; Minx et al., Reference Minx, Callaghan, Lamb, Garard and Edenhofer2017). In this paper, we identify key recent advances across diverse research areas on climate change, spanning natural and social sciences. We refer to these as ‘new insights’, selected on the grounds of their scientific evidence-base, novelty, and policy relevance, and anchored on the most recent peer-reviewed literature (Bustamante et al., Reference Bustamante, Roy, Ospina, Achakulwisut, Aggarwal, Bastos, Broadgate, Canadell, Carr, Chen, Cleugh, Ebi, Edwards, Farbotko, Fernández-Martínez, Frölicher, Fuss, Geden, Gruber and Zscheischler2023; Schaeffer et al., Reference Schaeffer, Schipper, Ospina, Mirazo, Alencar, Anvari, Artaxo, Biresselioglu, Blome, Boeckmann, Brink, Broadgate, Bustamante, Cai, Canadell, Cardinale, Chidichimo, Ditlevsen, Eicker and Ziervogel2025). This year, the synthesis is built on the collective effort of 75 researchers, based on input from more than 150 experts across the world. This paper has a dual purpose. First, it offers entry-points to enhance cross- and inter-disciplinary understanding among climate change researchers with very different domains of expertise. Second, it grounds the scientific messages highlighted in an annual science-policy report titled ‘10 New Insights in Climate Science,’ which is shared with all the Party delegations to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Before presenting this year's 10 insights, the Introduction offers a concise account of the state of the climate system and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2024, key outcomes of the 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29), and expectations leading into the COP30. We expand briefly on the rationale behind the 10 New Insights in Climate Science initiative, and explain how it is intended to contribute to more scientifically informed discussions at COP30 and beyond.

1.1. State of the climate system and GHG emissions

Key climate indicators continue to exhibit trends inconsistent with stabilising the climate system. In the first months of 2025, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) confirmed that 2024 was the warmest year on record, with an average temperature of 1.55°C (± 0.13°C) above pre-industrial levels (C3S, 2025a; WMO, 2025). While this does not signify a breach of the 1.5°C long-term warming limit of the Paris Agreement, it is a stark sign of how close we are to that. The year 2024 also brought record-breaking ocean-heat content and sea-level rise, exceptional glacier mass loss, and Antarctic sea ice reached its second-lowest extent on record (C3S, 2025a; WMO, 2025). The rise of global temperature has intensified extreme weather events, including heatwaves, droughts, wildfires, storms, and floods, potentially having caused tens or even hundreds of thousands of human deaths and displaced millions (Otto et al., Reference Otto, Giguere, Clarke, Barnes, Zachariah, Merz, Philip, Kew, Pinto and Vahlberg2024). And yet, despite the impacts already felt and the impending risks, anthropogenic GHG emissions further increased throughout 2023 and 2024 (Forster et al., Reference Forster, Smith, Walsh, Lamb, Lamboll, Cassou, Hauser, Hausfather, Lee, Palmer, von Schuckmann, Slangen, Szopa, Trewin, Yun, Gillett, Jenkins, Matthews, Raghavan and Zhai2025; Friedlingstein et al., Reference Friedlingstein, O'Sullivan, Jones, Andrew, Hauck, Landschützer, Le Quéré, Li, Luijkx, Olsen, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Schwingshackl, Sitch, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Alin and Zeng2025). As a direct result of this, atmospheric concentrations of GHGs continue their steady rise (C3S, 2025a; NOAA-GML, 2025).

At present, global mitigation action remains insufficient to achieve climate goals. Full implementation of the current nationally determined contributions (NDCs) would only reduce global emissions by 5.9% (3.2–8.6) by 2030, relative to 2019 levels (UNFCCC, 2024), and lead to warming of 2.6°C (1.9–3.6) by the end of the century (UNEP, 2024). In contrast, keeping the planet below 2°C warming (relative to the pre-industrial average) following a least-cost pathway requires a 28% reduction in global emissions (or 42% for 1.5°C) by 2030 (UNEP, 2024). These figures underscore the importance of rapidly “closing the gaps” on ambition and implementation in the new NDCs, submitted as part of the third cycle of commitments in order to achieve the 2035 targets.

Unfortunately, the third cycle of NDC submissions is progressing slowly. By the February 2025 deadline originally set by the UNFCCC, only 16 of 195 Parties had submitted the required updated NDCs. Among these 16, only a few major economies, such as the United Kingdom, Brazil, and the United Arab Emirates, submitted updates. The United States submitted its NDC in December 2024, but its withdrawal from the Paris Agreement will take legal effect at the end of January 2026. The UNFCCC extended the deadline to September 2025, which is the cutoff date for inclusion in the UNFCCC's annual NDC synthesis report, the official assessment of global progress toward the Paris Agreement goals to be presented at COP30 in Belém, Brazil (UNDP, 2025). As of September 19, only 37 Parties had submitted the updated NDCs, while major emitters, including China, India, the European Union, and Russia had not (Climate Watch, 2025; UNFCCC, 2025a). This lack of momentum is one of the biggest challenges at the moment for climate diplomacy.

1.2. From Baku to belém

Key outcomes from COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, include the adoption of the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) on climate finance, and an agreement on the framework for international carbon markets (Article 6 of the Paris Agreement) (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2025; Kessler & Vallejo, Reference Kessler and Vallejo2024; Waskow et al., Reference Waskow, Larsen, Robinson, Alayza, Boehm, Srouji, Chakrabarty, Swaby, Warszawski, Garcia, Carter, Cogswell, Gerholdt, Molesworth, Yaakov, Nilsson, McCoshan, Elliott, Null and Layke2024) (see Note S7 for a brief explanation of terms related to the UNFCCC process). However, the climate finance goal of $300 billion annually by 2035 is widely regarded as insufficient given the identified needs (Bhattacharya et al., Reference Bhattacharya, Songwe, Soubeyran and Stern2024). The Baku–Belém Roadmap to realise the $1.3 trillion aspirational goal is the main process to address the shortcomings, but it faces some highly contentious and unfinished items for operationalisation, including the sources (public-provided vs. private-mobilised funding), kind (grant- vs. loan-based), allocation (Adaptation and Loss & Damage), and accountability (standards for tracking and reporting) (Alayza & Larsen, Reference Alayza and Larsen2025). Progress on the Mitigation agenda at COP29 was minimal. At COP30, the expectation is to resolve issues regarding the “ambition cycle” structure, the role of the Mitigation Work Programme (MWP) going forward, and the implementation of the Global Stocktake (GST) outcome on transitioning away from fossil fuels. Aspects of the Paris Agreement rulebook still pending include carbon markets (e.g., technical guidance to prevent double-counting and the verification of removal projects), adaptation (e.g., inclusion of indicators on ‘means of implementation’), and just transition (e.g., global framework). But with almost all negotiations for the Paris Agreement finally completed, and scientific evidence showing there is no time to be wasted if the goals are to be reached, the focus is now firmly on effective implementation.

1.3. The ‘10 new insights in climate science’

Despite challenges, recent findings suggest that in most countries, people continue to trust scientists and support their increased engagement in public discourse and policymaking (Cologna et al., Reference Cologna, Mede, Berger, Besley, Brick, Joubert, Maibach, Mihelj, Oreskes, Schäfer, van der Linden, Abdul Aziz, Abdulsalam, Shamsi, Aczel, Adinugroho, Alabrese, Aldoh, Alfano and Zwaan2025). Science has a critical role in informing policymaking and governance, including the implementation of climate commitments at international, national, and sub-national levels. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the cornerstone of the science–policy interface on climate change. IPCC Assessment Reports reflect and, to a large extent, produce the scientific consensus. However, given their comprehensiveness and procedural demands, these assessment reports have a multi-year production cycle. The cut-off dates for inclusion of literature in the most recent Assessment Report (AR6) were in 2020 and 2021; hence, research published after 2021 will only be reflected in the reports of the next IPCC cycle (AR7), the first of which is expected to be published in 2028. Therefore, complementary synthesis and communication efforts are needed to share the emerging scientific advances more rapidly.

The 10 New Insights in Climate Science initiative responds to this need by curating and synthesising key messages across diverse fields of climate change research based on the latest peer-reviewed literature, on a yearly basis. It offers a thematically broad selection of scientific messages, in a format that is accessible to non-experts. The ultimate purpose is to support the timely uptake of new scientific evidence in policy processes and international governance spaces.

A ‘new insight’ refers to a recent advance in climate change research, based on new evidence or analysis that significantly updates existing understanding of climate processes, impacts, or possible solutions. An insight can also highlight an emerging area of research or a novel concept that is gaining attention and is seen as an important future direction for the field.

For a more detailed account of the positioning of this initiative in the broader science–policy landscape for climate change, in particular its complementary character to the IPCC reports, see Schaeffer et al. (Reference Schaeffer, Schipper, Ospina, Mirazo, Alencar, Anvari, Artaxo, Biresselioglu, Blome, Boeckmann, Brink, Broadgate, Bustamante, Cai, Canadell, Cardinale, Chidichimo, Ditlevsen, Eicker and Ziervogel2025).

1.4. Method

Every cycle of the 10 New Insights in Climate Science incorporates lessons from the previous year, resulting in a progressively more robust process for the selection and development of insights. The process (SM1) described further builds directly on the one described by Bustamante et al. (Reference Bustamante, Roy, Ospina, Achakulwisut, Aggarwal, Bastos, Broadgate, Canadell, Carr, Chen, Cleugh, Ebi, Edwards, Farbotko, Fernández-Martínez, Frölicher, Fuss, Geden, Gruber and Zscheischler2023). In January, an open call for expert input was distributed as an online questionnaire (SM2), primarily making use of the partners' institutional networks with global reach. The main question that respondents answer is ‘What key recent advance in climate change research do you think should be highlighted for policymakers?’ Respondents are also asked to provide references to recent peer-reviewed publications (i.e., 2024 or 2025) that support their suggested key research advance.

The call for expert input was open between 9 January and 5 February 2025 (4.5 weeks) and received responses from 154 individuals (SM3), totaling 179 suggestions. The suggestions or ‘entries’ collected were screened by at least two team members based on predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria (SM4). When necessary, project coordinators conducted one additional round of screening to come to a final decision. This year, 56 entries met the inclusion criteria. After merging the closely related entries, the list was reduced to 44 themes and coded using a thematic framework based on all previous ‘10 New Insights’ editions. This list was complemented with a literature scan (SM5) of impactful papers in climate change research published in the same period (2024 and the first months of 2025), which yielded 27 additional themes. The final list of 71 themes (SM6) was then evaluated in a three-stage process by our editorial board, consisting of 23 leading international climate change researchers from various disciplines. First, the 71 themes were categorised into four broad categories: (i) the Earth system, (ii) Impacts, (iii) Actions, and (iv) Barriers. The editorial board members then individually prioritised 4–20 themes (1–5 per category) that they considered most relevant overall. Second, building on the outcomes of the individual prioritisation of themes, the editorial board members gathered virtually for an initial 90-minute workshop to deliberate and collectively prioritise the themes, leading to a preliminary set of candidate insights. At a second workshop, the final set of insights was approved. For more details on the process, see Bustamante et al. (Reference Bustamante, Roy, Ospina, Achakulwisut, Aggarwal, Bastos, Broadgate, Canadell, Carr, Chen, Cleugh, Ebi, Edwards, Farbotko, Fernández-Martínez, Frölicher, Fuss, Geden, Gruber and Zscheischler2023) and Schaeffer et al. (Reference Schaeffer, Schipper, Ospina, Mirazo, Alencar, Anvari, Artaxo, Biresselioglu, Blome, Boeckmann, Brink, Broadgate, Bustamante, Cai, Canadell, Cardinale, Chidichimo, Ditlevsen, Eicker and Ziervogel2025).

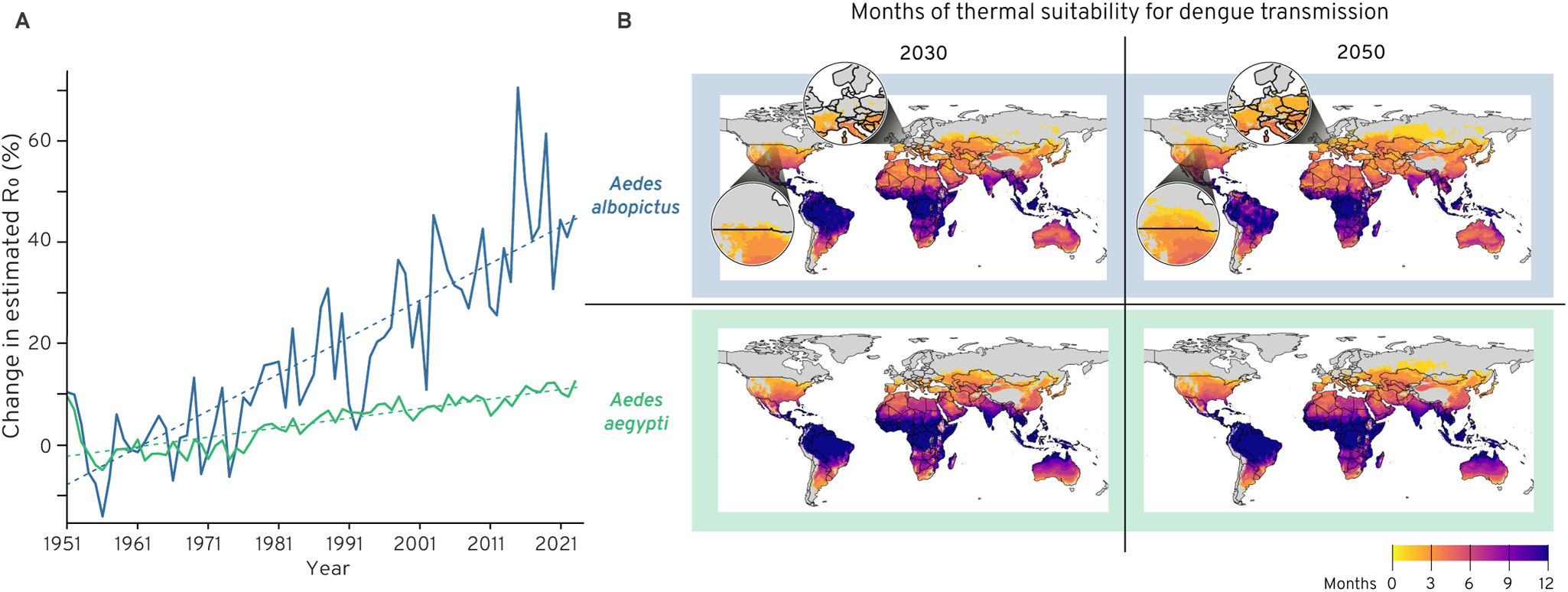

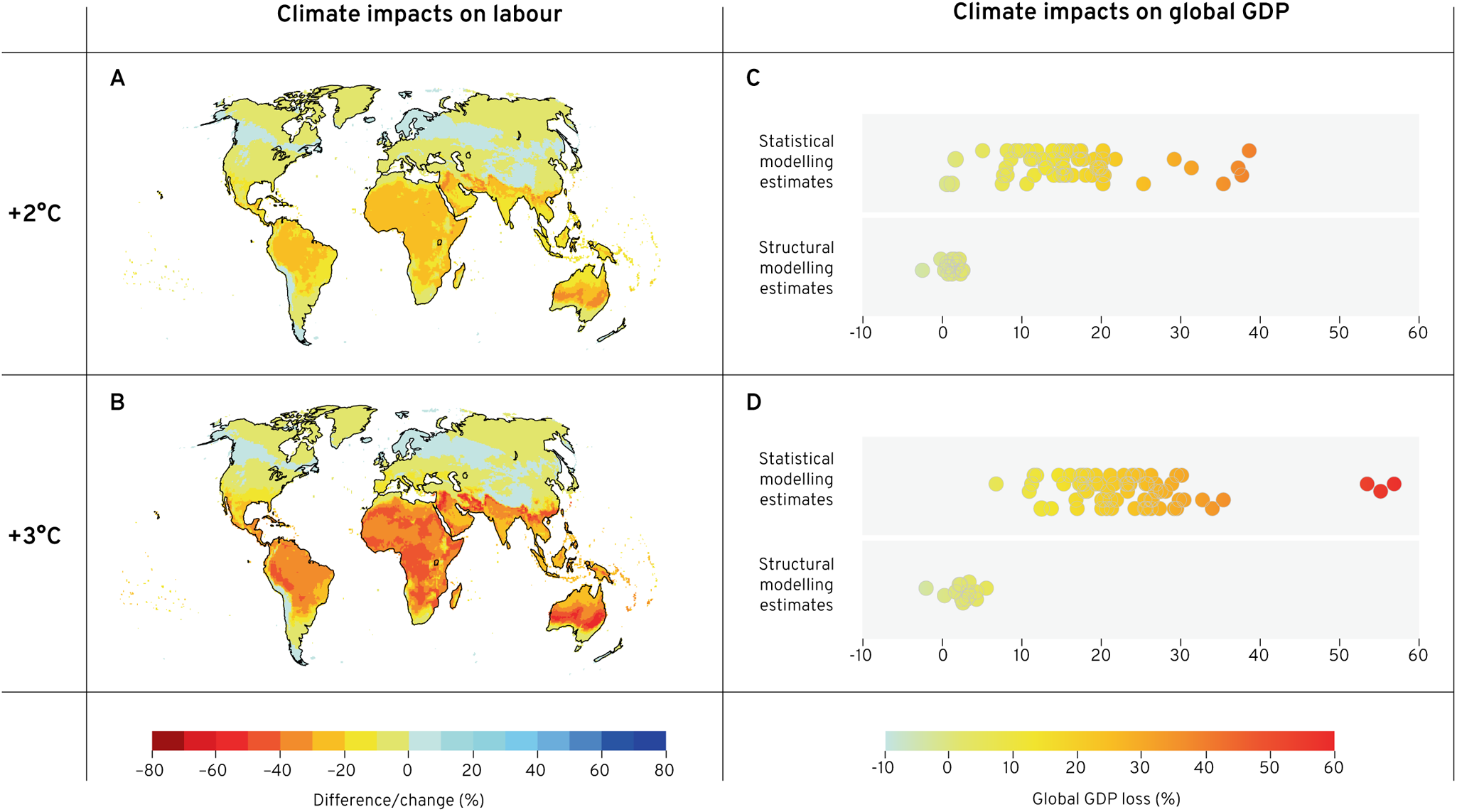

2. Results

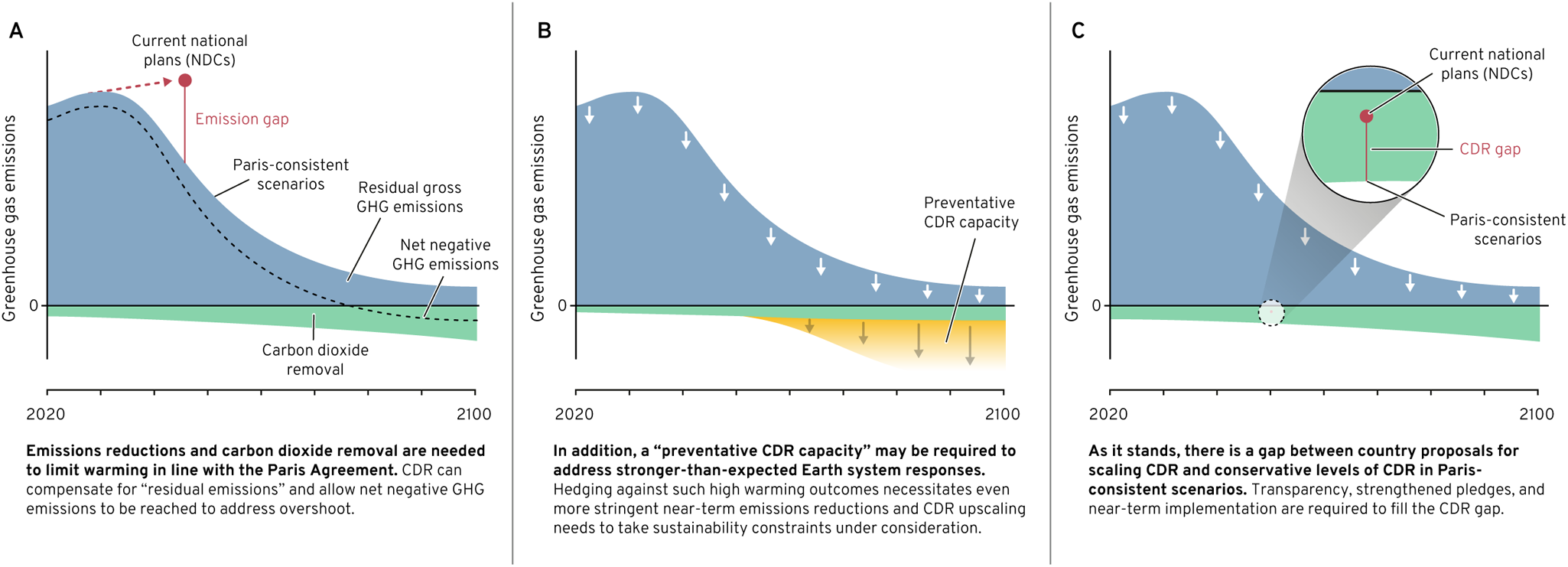

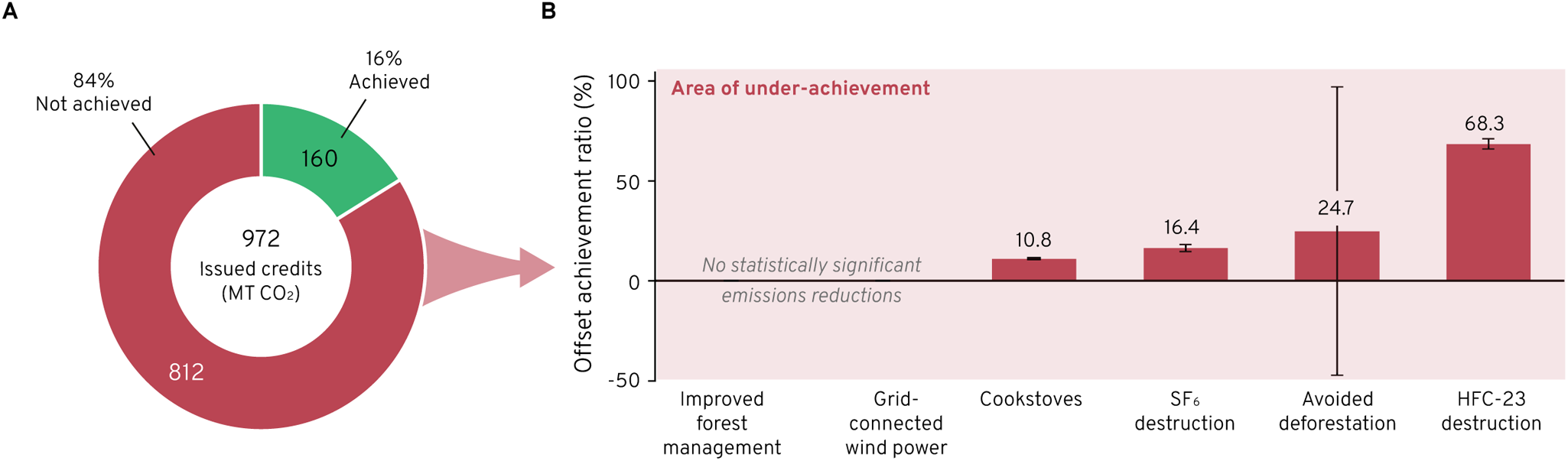

The 10 new insights featured this year begin with an explanation of the geophysical processes and remaining uncertainties behind the record-warm years of 2023/2024 (Insight 1), with an additional examination of the acceleration of warming in the oceans and impacts on marine heatwaves (Insight 2). We then highlight the latest evidence of strain on land carbon sinks, highlighting recent changes on the Northern Hemisphere sinks (Insight 3). Continuing on biosphere–climate interactions, we also synthesise new evidence on the direct effect of biodiversity loss on climate change (Insight 4). The next three insights focus on three distinct types of climate impacts: groundwater depletion (Insight 5), global incidence of dengue (Insight 6), and labour productivity and income loss (Insight 7). The final three insights focus on distinct and complementary approaches and instruments to mitigation, their potential, and limitations. Starting with strategic considerations for scaling CDR in the context of overshoot (Insight 8), carbon credit markets and associated integrity challenges (Insight 9), and the lessons on effective policy mixes for emissions reductions (Insight 10). After this ‘Results’ section, the insights are summarised into clusters of messages, and with links to discussions happening ahead of and in preparation for COP30.

Insight 1. Explaining the record warm years 2023/2024 – evidence, uncertainty, and remaining questions

Since 2023, global surface temperatures have shattered previous records, more likely than not surpassing 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels in 2024 and remaining elevated into 2025 (Forster et al., Reference Forster, Smith, Walsh, Lamb, Lamboll, Cassou, Hauser, Hausfather, Lee, Palmer, von Schuckmann, Slangen, Szopa, Trewin, Yun, Gillett, Jenkins, Matthews, Raghavan and Zhai2025; WMO, 2025). While the shift from La Niña to El Niño was expected to warm the planet, the intensity, global extent, and persistence of the heat were unprecedented (Min, Reference Min2024).

The unexpected level of global warmth (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2024) coincided with an elevated Earth Energy Imbalance (EEI) (Forster et al., Reference Forster, Smith, Walsh, Lamb, Lamboll, Cassou, Hauser, Hausfather, Lee, Palmer, von Schuckmann, Slangen, Szopa, Trewin, Yun, Gillett, Jenkins, Matthews, Raghavan and Zhai2025; Mauritsen et al., Reference Mauritsen, Tsushima, Meyssignac, Loeb, Hakuba, Pilewskie, Cole, Suzuki, Ackerman, Allan, Andrews, Bender, Bloch-Johnson, Bodas-Salcedo, Brookshaw, Ceppi, Clerbaux, Dessler, Donohoe and Zelinka2025). EEI is the difference between energy input from absorbed sunlight (shortwave radiation) and output in the form of infrared (longwave) radiation to space, such that an elevated positive EEI results in a greater heating rate and so an acceleration of global warming (Forster et al., Reference Forster, Storelvmo, Armour, Collins, Dufresne, Frame, Lunt, Mauritsen, Palmer, Watanabe, Wild, Zhang, Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pirani, Connors, Péan, Berger, Caud, Chen, Goldfarb, Gomis, Huang, Leitzell, Lonnoy, Matthews, Maycock, Waterfield, Yelekçi, Yu and Zhou2021; Minière et al., Reference Minière, von Schuckmann, Sallée and Vogt2023). Observed increases in EEI since 2000 and peaking in 2023 have been dominated by reducing reflection of sunlight from the planet as a whole (reduced planetary albedo) that was associated with diminished coverage of ice and less reflective clouds over the oceans (Allan & Merchant, Reference Allan and Merchant2025; Goessling et al., Reference Goessling, Rackow and Jung2025; Loeb, Ham, et al., Reference Loeb, Ham, Allan, Thorsen, Meyssignac, Kato, Johnson and Lyman2024; Tselioudis et al., Reference Tselioudis, Rossow, Bender, Oreopoulos and Remillard2024, Reference Tselioudis, Remillard, Jakob and Rossow2025). The role of feedbacks to warming (involving ice, cloud, and water vapour), declining aerosol particulate pollution, internal ocean variability and other factors in driving the planetary darkening remain debated (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Kharecha, Sato, Tselioudis, Kelly, Bauer, Ruedy, Jeong, Jin, Rignot, Velicogna, Schoeberl, von Schuckmann, Amponsem, Cao, Keskinen, Li and Pokela2025; Hodnebrog et al., Reference Hodnebrog, Myhre, Jouan, Andrews, Forster, Jia, Loeb, Olivié, Paynter, Quaas, Raghuraman and Schulz2024; Raghuraman et al., Reference Raghuraman, Paynter, Ramaswamy, Menzel and Huang2023). Here, we assess recent evidence on how unusual the level of warmth in 2023/2024 was in the context of climate variability, the role of the elevated EEI in explaining this warmth and what factors explain the elevated EEI, which has implications for the rate of climate change over the coming decades.

Accounting for the long-term warming caused by GHG increases, the margin by which the annual average ocean warmth April 2023 to March 2024 broke the previous annual record was found to occur only once in about 500 years or longer (Terhaar et al., Reference Terhaar, Burger, Vogt, Frölicher and Stocker2025), and the September 2023 margin just once in about 2000 years (Rantanen & Laaksonen, Reference Rantanen and Laaksonen2024) when considering variability based on observations and simulations. A large jump in global temperatures was made more likely by the transition from a prolonged La Niña phase to an El Niño, a situation that applied in 2023/2024 but also 1976/1977 (Raghuraman et al., Reference Raghuraman, Soden, Clement, Vecchi, Menemenlis and Yang2024). However, while a clear consensus is still missing, the recent temperature surge is only marginally reconcilable with the long-term warming trend combined with internal variability, particularly given that the 2023/2024 El Niño was not as strong as previous ones (Cattiaux et al., Reference Cattiaux, Ribes and Cariou2024; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Miyamoto, Zhang, Kosaka, Liang and Lutsko2025). This emphasises a need to investigate other contributing factors and to scrutinise changes in Earth's energy budget.

The substantial warming from 2022 to 2023 is physically determined by how much heat was absorbed by Earth's surface layers.The EEI reached 1.9 Wm−2 during mid-2022 to mid-2023, more than double the 2006–2020 average (Allan & Merchant, Reference Allan and Merchant2025; Kuhlbrodt et al., Reference Kuhlbrodt, Swaminathan, Ceppi and Wilder2024; von Schuckmann et al., Reference von Schuckmann, Minière, Gues, Cuesta-Valero, Kirchengast, Adusumilli, Straneo, Ablain, Allan, Barker, Beltrami, Blazquez, Boyer, Cheng, Church, Desbruyeres, Dolman, Domingues, García-García and Zemp2023) and at the upper level of what is expected from detailed modelling (Hodnebrog et al., Reference Hodnebrog, Myhre, Jouan, Andrews, Forster, Jia, Loeb, Olivié, Paynter, Quaas, Raghuraman and Schulz2024). Only around 15–20% of this increased EEI contributed to heating of the atmosphere and land, and to a lesser extent melting of ice (Allan & Merchant, Reference Allan and Merchant2025; Minobe et al., Reference Minobe, Behrens, Findell, Loeb, Meyssignac and Sutton2025). The remainder increased ocean heating (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Abraham, Trenberth, Boyer, Mann, Zhu, Wang, Yu, Locarnini, Fasullo, Zheng, Li, Zhang, Wan, Chen, Wang, Feng, Song, Liu and Lu2024). The magnitude of sea surface warming can only be reconciled with this ocean heating if concentrated in shallower upper-most ocean layers (England et al., Reference England, Li, Huguenin, Kiss, Sen Gupta, Holmes and Rahmstorf2025; Guinaldo et al., Reference Guinaldo, Cassou, Sallée and Liné2025; Li, Huang, et al., Reference Li, Huang, Liu, Ding, He and Xie2024) or through redistribution of heat from the subsurface 100–300 m ocean layer to the upper 100 m layer during the transition to El Niño in 2023, which added to the greater heating from above due to a larger EEI (Allan & Merchant, Reference Allan and Merchant2025; Min, Reference Min2024; Minobe et al., Reference Minobe, Behrens, Findell, Loeb, Meyssignac and Sutton2025) (see Insight 2). Research confirms that EEI increases since 2000 are dominated by greater absorption of sunlight, and associated primarily with reduced reflectivity over cloudy regions of the ocean (Allan & Merchant, Reference Allan and Merchant2025; Goessling et al., Reference Goessling, Rackow and Jung2025; Loeb, Ham, et al., Reference Loeb, Ham, Allan, Thorsen, Meyssignac, Kato, Johnson and Lyman2024).

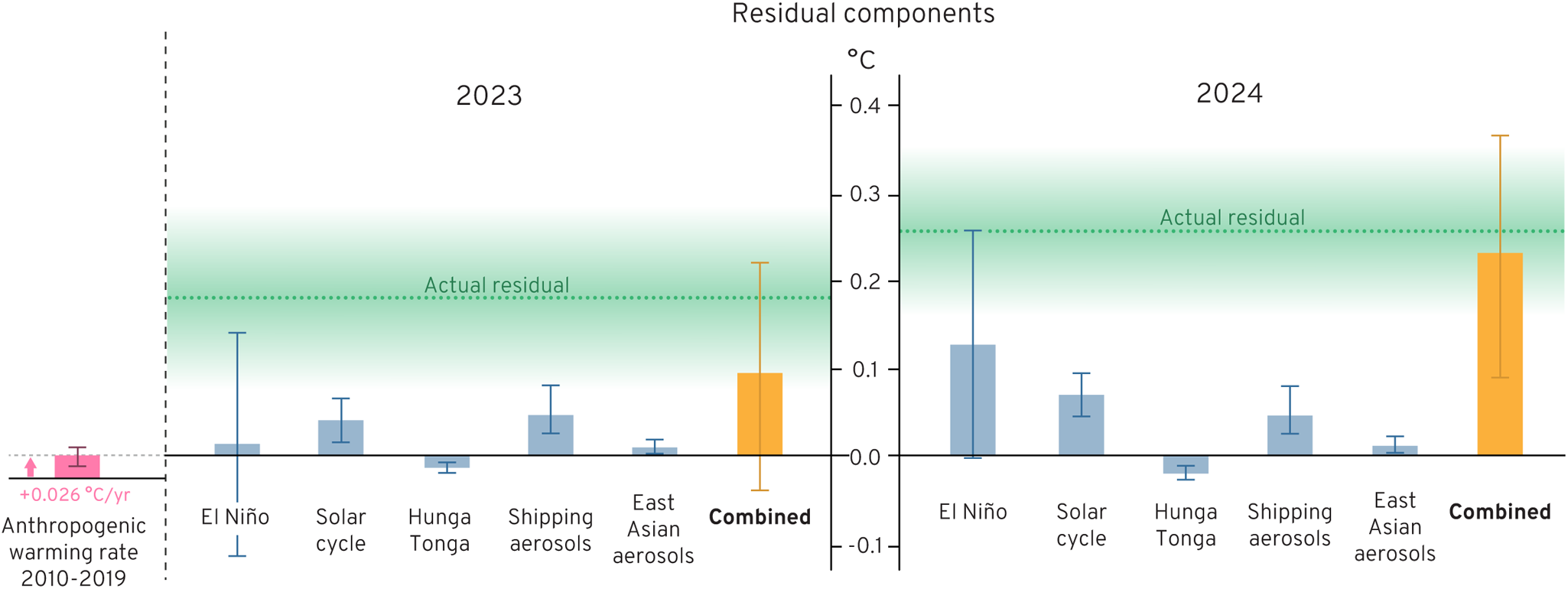

Figure 1 shows factors contributing to extra warming in 2023 and 2024, additional to the average annual rise caused mainly by rising greenhouse gases. A moderate additional heating from the 11-year solar cycle, which was slightly stronger and earlier than expected (P. M. Forster et al., Reference Forster, Smith, Walsh, Lamb, Lamboll, Cassou, Hauser, Hausfather, Lee, Palmer, von Schuckmann, Slangen, Szopa, Trewin, Yun, Gillett, Jenkins, Matthews, Raghavan and Zhai2025), contributed extra warming (Goessling et al., Reference Goessling, Rackow and Jung2025; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Kharecha, Sato, Tselioudis, Kelly, Bauer, Ruedy, Jeong, Jin, Rignot, Velicogna, Schoeberl, von Schuckmann, Amponsem, Cao, Keskinen, Li and Pokela2025; Merchant et al., Reference Merchant, Allan and Embury2025). The effect of the Hunga Tonga undersea volcanic eruption that peaked in early 2022 is now considered small since warming from water vapour injected into the normally dry stratosphere was offset by cooling from greater reflection of sunlight by sulfate aerosol particles also emitted (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Mittal, Fauria, Bennartz and Kok2025; Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Smith, Allen and Grainger2023; Schoeberl et al., Reference Schoeberl, Wang, Taha, Zawada, Ueyama and Dessler2024; Stenchikov et al., Reference Stenchikov, Ukhov and Osipov2025; Stocker et al., Reference Stocker, Steiner, Ladstädter, Foelsche and Randel2024) (Figure 1). Effects from other volcanoes and wildfire (Yu et al., Reference Yu, Portmann, Peng, Liu, Zhu, Asher, Bai, Lu, Bian, Mills, Schmidt, Rosenlof and Toon2023), or reduced Sahara dust in June 2023 (Francis et al., Reference Francis, Fonseca, Nelli and Yarragunta2024) are also considered small at the global scale. A larger influence on the elevated EEI and associated warming is expected from reductions in sulfate aerosol pollution originating from different sources (Figure 1), primarily through the subsequent influence on clouds, which can explain a considerable part of the increase in EEI in 2001–2019 (Hodnebrog et al., Reference Hodnebrog, Myhre, Jouan, Andrews, Forster, Jia, Loeb, Olivié, Paynter, Quaas, Raghuraman and Schulz2024).

Figure 1. Estimates of contributing factors to the anomalous global mean temperatures in 2023 and 2024 (residual components), adding to the annual warming effect from increasing radiative forcing dominated by rising greenhouse gases (left-side pink bar: 0.026 [0.02–0.04]°C/yr, as assessed by Forster et al., Reference Forster, Smith, Walsh, Lamb, Lamboll, Hall, Hauser, Ribes, Rosen, Gillett, Palmer, Rogelj, von Schuckmann, Trewin, Allen, Andrew, Betts, Borger, Boyer and Zhai2024 for 2010–2019). The actual residual for each year (green dashed line) is the difference between the annual global mean temperature in 2023 and 2024, and a 20-year trend (LOESS smoothed, with green fading area hinting at the uncertainties). Individual residual components (vertical bars) indicate the specific contributions for each of the 2 years (uncertainty bars nominally represent the 95% confidence level). The residual data displayed are from WMO (2025), see Figure 12 therein and associated discussion for details (cf. Forster et al. (Reference Forster, Smith, Walsh, Lamb, Lamboll, Cassou, Hauser, Hausfather, Lee, Palmer, von Schuckmann, Slangen, Szopa, Trewin, Yun, Gillett, Jenkins, Matthews, Raghavan and Zhai2025) made a similar analysis). It is important to note that the data shown are only indicative and represent preliminary estimates. References discussed in the main text provide more information on each component; these references are, however, not necessarily the same as used by WMO (2025) for deriving the temperature contributions.

First, regulations implemented in 2020 reduced sulfur emissions from international shipping by ∼80% and the resulting reduction in sulfate aerosol particles led to a heating effect due to less sunlight being reflected, particularly through aerosol effects on clouds (Forster et al., Reference Forster, Smith, Walsh, Lamb, Lamboll, Hall, Hauser, Ribes, Rosen, Gillett, Palmer, Rogelj, von Schuckmann, Trewin, Allen, Andrew, Betts, Borger, Boyer and Zhai2024; Gettelman et al., Reference Gettelman, Christensen, Diamond, Gryspeerdt, Manshausen, Stier, Watson-Parris, Yang, Yoshioka and Yuan2024; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Kharecha, Sato, Tselioudis, Kelly, Bauer, Ruedy, Jeong, Jin, Rignot, Velicogna, Schoeberl, von Schuckmann, Amponsem, Cao, Keskinen, Li and Pokela2025; Jordan & Henry, Reference Jordan and Henry2024; Quaglia & Visioni, Reference Quaglia and Visioni2024; Skeie et al., Reference Skeie, Byrom, Hodnebrog, Jouan and Myhre2024; Yoshioka et al., Reference Yoshioka, Grosvenor, Booth, Morice and Carslaw2024; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Song, Oreopoulos, Wood, Bian, Breen, Chin, Yu, Barahona, Meyer and Platnick2024; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Chen, Gryspeerdt, Yamaguchi and Feingold2025). There is a potentially large regional temperature change induced by the sulfur cap, especially over the mid-latitude oceans in the Northern Hemisphere (Gettelman et al., Reference Gettelman, Christensen, Diamond, Gryspeerdt, Manshausen, Stier, Watson-Parris, Yang, Yoshioka and Yuan2024). The sulfur cap is mostly estimated to have a moderate effect on global surface warming based on a variety of methods (Gettelman et al., Reference Gettelman, Christensen, Diamond, Gryspeerdt, Manshausen, Stier, Watson-Parris, Yang, Yoshioka and Yuan2024; Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Kharecha, Sato, Tselioudis, Kelly, Bauer, Ruedy, Jeong, Jin, Rignot, Velicogna, Schoeberl, von Schuckmann, Amponsem, Cao, Keskinen, Li and Pokela2025; Jordan & Henry, Reference Jordan and Henry2024; Quaglia & Visioni, Reference Quaglia and Visioni2024; Watson-Parris et al., Reference Watson-Parris, Wilcox, Stjern, Allen, Persad, Bollasina, Ekman, Iles, Joshi, Lund, McCoy, Westervelt, Williams and Samset2025; Yoshioka et al., Reference Yoshioka, Grosvenor, Booth, Morice and Carslaw2024; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Song, Oreopoulos, Wood, Bian, Breen, Chin, Yu, Barahona, Meyer and Platnick2024) (Figure 1).

Second, there was a pronounced decline in land-based anthropogenic aerosol emissions in recent decades (Insight 2 in Schaeffer et al., Reference Schaeffer, Schipper, Ospina, Mirazo, Alencar, Anvari, Artaxo, Biresselioglu, Blome, Boeckmann, Brink, Broadgate, Bustamante, Cai, Canadell, Cardinale, Chidichimo, Ditlevsen, Eicker and Ziervogel2025). Rapid aerosol emission reductions over East Asia since their peak in the early 2000s have significantly contributed to global warming during 2010–2023 (Samset et al., Reference Samset, Wilcox, Allen, Stjern, Lund, Ahmadi, Ekman, Elling, Fraser-Leach, Griffiths, Keeble, Koshiro, Kushner, Lewinschal, Makkonen, Merikanto, Nabat, Narazenko, O'Donnell and Westervelt2025), and to record high sea surface temperatures in the Northeast Pacific in 2010–2020 that were potentially amplified by cloud feedback responses to the warming (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zheng, Cai, Han, Xie, Kang, Geng, Liu, Wang, Wu, Xiang and Zhou2024). While extra absorbed sunlight associated with declining East Asian aerosol is physically linked with the long-term warming trend, their contribution to the level of global warmth in 2023/2024 is less obvious (Figure 1). More recently, however, the reduction of aerosol emissions in areas where pollution has already been somewhat mitigated, such as East Asia, or over the still moderately pristine open ocean, is thought to have a larger effect on reducing the reflectiveness of clouds than previously believed (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Kharecha, Sato, Tselioudis, Kelly, Bauer, Ruedy, Jeong, Jin, Rignot, Velicogna, Schoeberl, von Schuckmann, Amponsem, Cao, Keskinen, Li and Pokela2025; H. Jia & Quaas, Reference Jia and Quaas2023).

Several uncertainties remain when it comes to the causes and implications of the record heat since 2023. Aerosol–cloud interactions and cloud feedbacks display a large diversity across model simulations (Forster et al., Reference Forster, Storelvmo, Armour, Collins, Dufresne, Frame, Lunt, Mauritsen, Palmer, Watanabe, Wild, Zhang, Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pirani, Connors, Péan, Berger, Caud, Chen, Goldfarb, Gomis, Huang, Leitzell, Lonnoy, Matthews, Maycock, Waterfield, Yelekçi, Yu and Zhou2021; Zelinka et al., Reference Zelinka, Smith, Qin and Taylor2023), and the inability of coarse-resolution global models to adequately represent ship tracks adds to the uncertainty in estimates of climate impacts of the sulfur cap (Gettelman et al., Reference Gettelman, Christensen, Diamond, Gryspeerdt, Manshausen, Stier, Watson-Parris, Yang, Yoshioka and Yuan2024). A more robust quantification of the cloud feedback, including how circulation-induced shrinking of cloud zones contributes (Tselioudis et al., Reference Tselioudis, Remillard, Jakob and Rossow2025), can inform to what extent global warming is accelerating by these effects. EEI observations from Clouds and the Earth's Radiant Energy System (CERES) since 2000 are essential for modelling initiatives proposed to disentangle forcings and feedbacks and to improve models (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Andrews, Bauer, Durack, Loeb, Ramaswamy, Arnold, Bosilovich, Cole, Horowitz, Johnson, Lyman, Medeiros, Michibata, Olonscheck, Paynter, Raghuraman, Schulz, Takasuka and Ziehn2023) yet are at risk due to aging satellites (Loeb, Doelling, et al., Reference Loeb, Doelling, Kato, Su, Mlynczak and Wilkins2024; Mauritsen et al., Reference Mauritsen, Tsushima, Meyssignac, Loeb, Hakuba, Pilewskie, Cole, Suzuki, Ackerman, Allan, Andrews, Bender, Bloch-Johnson, Bodas-Salcedo, Brookshaw, Ceppi, Clerbaux, Dessler, Donohoe and Zelinka2025).

In summary, new insights add to evidence that a combination of cloud feedback responses to global warming and reduced reflection of sunlight by clouds in response to declining aerosol emissions have plausibly contributed to the long-term increase in the absorption of sunlight by the planet since 2000. The exact relative importance of these drivers or the additional role of internal ocean variability in contributing to Earth's growing energy imbalance have not been established, yet are essential for reducing the range in climate sensitivity estimates (Goessling et al., Reference Goessling, Rackow and Jung2025) with low climate sensitivity models recently found being unable to reproduce observed EEI trends (Myhre et al., Reference Myhre, Hodnebrog, Loeb and Forster2025). Combined with rising GHG levels, this extra planetary heating and a redistribution of heat in the upper ocean associated with a transition from an extended La Niña to El Niño in 2023 were instrumental in explaining the record global warmth in 2023/2024. Current levels of global temperature are consistent with a continued acceleration of global warming (Samset et al., Reference Samset, Zhou, Fuglestvedt, Lund, Marotzke and Zelinka2023) and suggest that surpassing the 1.5oC threshold above pre-industrial conditions is practically inevitable (Bevacqua et al., Reference Bevacqua, Schleussner and Zscheischler2025; Insight 1 in Bustamante et al., Reference Bustamante, Roy, Ospina, Achakulwisut, Aggarwal, Bastos, Broadgate, Canadell, Carr, Chen, Cleugh, Ebi, Edwards, Farbotko, Fernández-Martínez, Frölicher, Fuss, Geden, Gruber and Zscheischler2023; Cannon, Reference Cannon2025) yet highlights the importance of massive cuts in GHG emissions are for limiting further warming and associated impacts on societies and ecosystems.

Insight 2. Sea surface warming is accelerating and marine heatwaves are intensifying

The global average temperature of the ocean surface serves as a key indicator of climate change. Record-breaking levels of global mean sea surface temperature were recorded in April 2023 and monthly records were then continuously set for over a year until June 2024 (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Abraham, Trenberth, Reagan, Zhang, Storto, Von Schuckmann, Pan, Zhu, Mann, Zhu, Wang, Yu, Locarnini, Fasullo, Huang, Graham, Yin, Gouretski and Gues2025; Terhaar et al., Reference Terhaar, Burger, Vogt, Frölicher and Stocker2025). As the largest sink for Earth's accumulating heat, the ocean sets the pace for global warming, and, as new analysis outlined below shows (Merchant et al., Reference Merchant, Allan and Embury2025), that pace is accelerating. That is, the warming trend underneath internal and solar variability has been faster over the last 10–15 years compared to previous decades. Impacts on ocean life have been widespread, often severe and in some cases likely irreversible (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Sen Gupta, Burrows, Filbee-Dexter, Hobday, Holbrook, Malan, Moore, Oliver, Thomsen, Wernberg, Zhao and Smale2025).

The global mean sea surface temperature for 2024 was 0.6°C warmer than a baseline of 1981 to 2019 (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Abraham, Trenberth, Reagan, Zhang, Storto, Von Schuckmann, Pan, Zhu, Mann, Zhu, Wang, Yu, Locarnini, Fasullo, Huang, Graham, Yin, Gouretski and Gues2025), slightly warmer than for 2023, and about 0.9°C warmer than preindustrial (C3S, 2025b). Temperatures exceeded the previous records set in 2015–2016 by 0.25°C on average between April 2023 and March 2024 (Terhaar et al., Reference Terhaar, Burger, Vogt, Frölicher and Stocker2025). Given a long-term warming trend, it is not unexpected that El Niño years break records, but the magnitude of exceedance is large given that the El Niño of 2023–2024 was not particularly intense. The probability of the observed exceptional global exceedance assuming a steady linear warming trend has been shown to be low (about 1 in 500 years (Terhaar et al., Reference Terhaar, Burger, Vogt, Frölicher and Stocker2025)). Driven by the Earth's energy accumulation over the past decade (see Insight 1), acceleration of the underlying warming trend is physically plausible and is now statistically detectable (Merchant et al., Reference Merchant, Allan and Embury2025). Acceleration of global mean sea surface temperature is consistent with accelerations in the storage of heat in the ocean (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Abraham, Trenberth, Reagan, Zhang, Storto, Von Schuckmann, Pan, Zhu, Mann, Zhu, Wang, Yu, Locarnini, Fasullo, Huang, Graham, Yin, Gouretski and Gues2025; von Schuckmann et al., Reference von Schuckmann, Minière, Gues, Cuesta-Valero, Kirchengast, Adusumilli, Straneo, Ablain, Allan, Barker, Beltrami, Blazquez, Boyer, Cheng, Church, Desbruyeres, Dolman, Domingues, García-García and Zemp2023) and contributes to accelerating sea level rise, both of which are well-established.

The rise in global ocean temperature is accompanied by an increasing incidence of marine heatwaves (MHWs), which last days to months (Cael et al., Reference Cael, Burger, Henson, Britten and Frolicher2024). Based on a fixed baseline (K. E. Smith et al., Reference Smith, Sen Gupta, Burrows, Filbee-Dexter, Hobday, Holbrook, Malan, Moore, Oliver, Thomsen, Wernberg, Zhao and Smale2025) for MHW detection (Box 1), the persistence of MHWs has increased by about one week over the past four decades (Capotondi et al., Reference Capotondi, Rodrigues, Gupta, Benthuysen, Deser, Froelicher, Lovenduski, Amaya, Le Grix, Xu, Hermes, Holbrook, Martinez-Villalobos, Masina, Roxy, Schaeffer, Schlegel, Smith and Wang2024; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Song, Choi, Cho and Marshall2025). MHW intensity has increased across 65% of the global ocean during 2000–2016 compared to 1982–1998, and over this period, annual number of MHW days has risen by 54% (Oliver et al., Reference Oliver, Donat, Burrows, Moore, Smale, Alexander, Benthuysen, Feng, Sen Gupta, Hobday, Holbrook, Perkins-Kirkpatrick, Scannell, Straub and Wernberg2018). An exceptionally extreme, near-basin-scale marine heatwave was experienced in the North Atlantic in 2023 (England et al., Reference England, Li, Huguenin, Kiss, Sen Gupta, Holmes and Rahmstorf2025). These changes are in part driven by weakening interaction between the upper and the deeper ocean, as the upper waters warm faster and become relatively more buoyant (England et al., Reference England, Li, Huguenin, Kiss, Sen Gupta, Holmes and Rahmstorf2025). Climate models consistently project further increases in both the frequency and intensity of MHWs under continued global warming (Cael et al., Reference Cael, Burger, Henson, Britten and Frolicher2024; Deser et al., Reference Deser, Phillips, Alexander, Amaya, Capotondi, Jacox and Scott2024; Frölicher et al., Reference Frölicher, Fischer and Gruber2018).

Box 1. Definition of Marine Heatwaves

Marine heatwaves (MHWs) are periods of abnormally high sea surface temperatures that persist for days to months or even longer and can extend across thousands of square-kilometers. MHWs are commonly defined as sea water temperatures exceeding the 90th percentile relative to a baseline climatology for at least five consecutive days (Hobday et al. Reference Hobday, Alexander, Perkins, Smale, Straub, Oliver, Benthuysen, Burrows, Donat, Feng, Holbrook, Moore, Scannell, Sen Gupta and Wernberg2016). These events can occur at the surface or subsurface and have wide-ranging ecological, biogeochemical, and socioeconomic impacts (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Sen Gupta, Burrows, Filbee-Dexter, Hobday, Holbrook, Malan, Moore, Oliver, Thomsen, Wernberg, Zhao and Smale2025).

MHWs are not purely a surface phenomenon, but also occur in the sub-surface where the majority of fish live and diurnally migrate (Sun et al., Reference Sun, Li, Jing, Hu and Zhang2023). Heatwaves in the sub-surface layer can be more intense than their surface counterparts, and most do not co-occur with surface heatwaves (He et al., Reference He, Zhan, Feng, Gong, Cai and Zhan2024; Köhn et al., Reference Köhn, Vogt, Muennich and Gruber2024). Sub-surface MHWs are often caused by ocean eddies and are intensifying more rapidly (0.1–1°C per decade) than the rise in mean state temperature (around 0.1°C per decade) under global warming (Guo et al., Reference Guo, Gao, Zhang, Cai, Chen, Leung, Zscheischler, Thompson, Davis, Qu, Gao and Wu2024; Köhn et al., Reference Köhn, Vogt, Muennich and Gruber2024). Despite growing recognition of the ecological importance of subsurface MHWs, the scarcity of observations presents a challenge to gaining a full understanding of their dynamics and impacts (Le Grix et al., Reference Le Grix, Burger and Frölicher2025; S. Li & Hu, Reference Li and Hu2024).

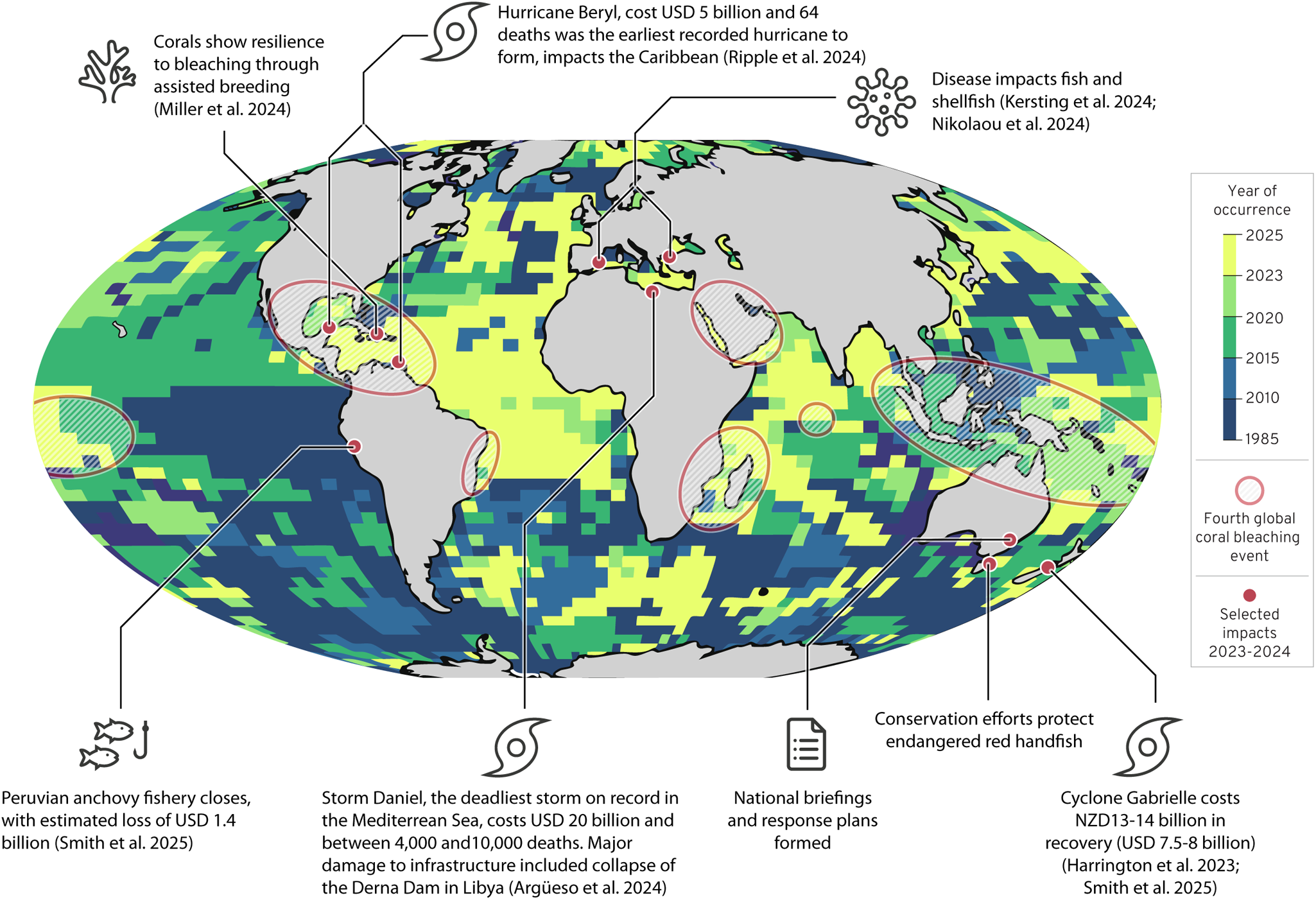

Oceanic warming is of concern on land and in the oceans themselves. The weather and seasons experienced by human populations are strongly determined by the warmth of the ocean (Armour et al., Reference Armour, Proistosescu, Dong, Hahn, Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, Pauling, Jnglin Wills, Andrews, Stuecker, Po-Chedley, Mitevski, Forster and Gregory2024; Samset et al., Reference Samset, Lund, Fuglestvedt and Wilcox2024). Exceptional sea surface temperatures tend to strengthen European heatwaves (Berthou et al., Reference Berthou, Renshaw, Smyth, Tinker, Grist, Wihsgott, Jones, Inall, Nolan, Berx, Arnold, Blunn, Castillo, Cotterill, Daly, Dow, Gómez, Fraser-Leonhardt, Hirschi and Worsfold2024) and to increase the likelihood for Atlantic, Caribbean and Pacific hurricanes to intensify (Choi et al., Reference Choi, Park, Kim and Lee2024; Radfar, Moftakhari, et al., Reference Radfar, Moftakhari and Moradkhani2024). Several studies linked MHWs and extreme weather events like hurricanes, cyclones, flooding, and atmospheric heatwaves (Berthou et al., Reference Berthou, Renshaw, Smyth, Tinker, Grist, Wihsgott, Jones, Inall, Nolan, Berx, Arnold, Blunn, Castillo, Cotterill, Daly, Dow, Gómez, Fraser-Leonhardt, Hirschi and Worsfold2024; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Park, Kim and Lee2024; Radfar, Foroumandi, et al., Reference Radfar, Foroumandi, Moftakhari, Moradkhani, Foltz and Gupta2024; Ripple et al., Reference Ripple, Wolf, Gregg, Rockstroem, Mann, Oreskes, Lenton, Rahmstorf, Newsome, Xu, Svenning, Pereira, Law and Crowther2024). Higher economic costs of MHWs were evident, including US$7.5–8.5 billion recovery costs from Cyclone Gabrielle, fuelled by a MHW; US$1.4 billion loss from the closure of the Peruvian anchovy fishery following a species range shift (Figure 2); and ongoing closures or reduced quotas in North American fisheries following MHWs (Harrington et al., Reference Harrington, Dean, Awatere, Rosier, Queen, Gibson, Barnes, Zachariah, Philip, Kew, Koren, Pinto, Grieco, Vahlberg, Snigh, Heinrich, Thalheimer, Li, Stone and Otto2023; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Sen Gupta, Burrows, Filbee-Dexter, Hobday, Holbrook, Malan, Moore, Oliver, Thomsen, Wernberg, Zhao and Smale2025). A warmer ocean surface also reduces the uptake of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere: Li, Burger, et al. (Reference Li, Burger, Raible and Frölicher2024) estimate a global net reduction of 8% during MHWs over 1990–2019, reducing nature's mitigation of human carbon emissions.

Figure 2. The impacts of the exceptional marine heatwaves in 2023–2024 and the period of occurrence of the warmest sea surface temperature (relative to the seasonal normal) in the satellite record since 1985. Dataset: ESA Climate Change Initiative Sea Surface Temperature v3 (Embury et al., Reference Embury, Merchant, Good, Rayner, Høyer, Atkinson, Block, Alerskans, Pearson, Worsfold, McCarroll and Donlon2024). ‘Year of occurrence’ refers to the year of warmest sea surface temperature (relative to the seasonal average) in the satellite record since 1985.

Across 2023 and 2024, various impacts of MHWs were reported (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Sen Gupta, Burrows, Filbee-Dexter, Hobday, Holbrook, Malan, Moore, Oliver, Thomsen, Wernberg, Zhao and Smale2025). New research shows MHW-associated declines in foundation species like macroalgae, seagrass and corals in many coastal ecosystems globally (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Aubin, Burrows, Filbee-Dexter, Hobday, Holbrook, King, Moore, Gupta, Thomsen, Wernberg, Wilson and Smale2024), highlighted in Figure 2. In 2024, the fourth global coral bleaching event (i.e., a stress response whereby the symbiotic zooxanthellae which give corals their colour are lost due to thermal stress) was declared (Reimer et al., Reference Reimer, Peixoto, Davies, Traylor-Knowles, Short, Cabral-Tena, Burt, Pessoa, Banaszak, Winters, Moore, Schoepf, Kaullysing, Calderon-Aguilera, Wörheide, Harding, Munbodhe, Mayfield, Ainsworth and Voolstra2024). In the tropical Atlantic, where corals are considered more resilient to bleaching, massive bleaching events have occurred in response to increases in frequency and intensity of MHWs over the last two decades (Rodrigues, Neto, et al., Reference Rodrigues, Neto, Vieira and Longo2025). In the Mediterranean, MHWs worsened outbreaks of disease, causing mortality events in fish and shellfish (Kersting et al., Reference Kersting, García-Quintanilla, Quintano, Estensoro and Ortega-Villaizan2024; Nikolaou et al., Reference Nikolaou, Papadimitriou, Kiourani and Katsanevakis2024), and satellite observations identified shifts in the size and biomass of phytoplankton linked to MHWs in eastern boundary upwelling systems, in the western Baltic Sea and South Atlantic (Cahill et al., Reference Cahill, Chrysagi, Vortmeyer-Kley and Graewe2024; Rodrigues, Artana, et al., Reference Rodrigues, Artana, Neto, Frolicher, Keenlyside, Hobday, Burger, Bernardo and Araujo2025; Zhan et al., Reference Zhan, Feng, Zhang, Shen, Zhan and He2024).

The responses of marine species can be variable and often depend on where within a species' geographic range the MHW occurs, complicating efforts to predict and interpret biological impacts (Fredston et al., Reference Fredston, Cheung, Frolicher, Kitchel, Maureaud, Thorson, Auber, Merigot, Palacios-Abrantes, Palomares, Pecuchet, Shackell and Pinsky2023; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Aubin, Burrows, Filbee-Dexter, Hobday, Holbrook, King, Moore, Gupta, Thomsen, Wernberg, Wilson and Smale2024). Trophic models indicate that at the community scale, MHWs significantly reduce biomass across all consumer levels, with higher trophic levels most affected (Guibourd de Luzinais et al., Reference Guibourd de Luzinais, Gascuel, Reygondeau and Cheung2024), altering ecosystem structure and function (Gomes et al., Reference Gomes, Ruzicka, Crozier, Huff, Brodeur and Stewart2024). Some ‘wins’ were reported, with corals bred for heat tolerance demonstrating resistance to bleaching (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Mendoza Quiroz, Lachs, Banaszak, Chamberland, Guest, Gutting, Latijnhouwers, Sellares-Blasco, Virdis, Villalpando and Petersen2024), and conservation efforts showed some potential for preserving endangered species (Hobday et al., Reference Hobday, Spillman, Allnutt, Coleman, Bailleul, Blamey, Brodie, Chandrapavan, Hartog, Maynard, Mundy, Plaganyi, Seaborn, Smith and Stuart-Smith2024).

Widespread impacts driven by MHWs are occurring more often and more intensely than previously reported (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Aubin, Burrows, Filbee-Dexter, Hobday, Holbrook, King, Moore, Gupta, Thomsen, Wernberg, Wilson and Smale2024). Sharing of successful intervention strategies may reduce or delay impacts to some industries and ecosystem services supported by the oceans (Hobday et al., Reference Hobday, Burrows, Filbee-Dexter, Holbrook, Sen Gupta, Smale, Smith, Thomsen and Wernberg2023; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Sen Gupta, Burrows, Filbee-Dexter, Hobday, Holbrook, Malan, Moore, Oliver, Thomsen, Wernberg, Zhao and Smale2025). Ultimately, mitigating future ecological, economic and societal losses will depend on rapid measures to reduce GHG emissions and limit ocean warming (Frölicher et al., Reference Frölicher, Fischer and Gruber2018; Hoegh-Guldberg et al., Reference Hoegh-Guldberg, Skirving, Dove, Spady, Norrie, Geiger, Liu, De La Cour and Manzello2023; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Burrows, Hobday, King, Moore, Sen Gupta, Thomsen, Wernberg and Smale2023).

Insight 3. Permafrost and boreal forests show signs of strain, raising concerns about the global land carbon sink

While the fraction of anthropogenic GHG emissions absorbed by the global natural land carbon sink – whose magnitude partly determines Earth's contribution to offsetting anthropogenic emissions — has remained stable at around 30% (Friedlingstein et al., Reference Friedlingstein, O'Sullivan, Jones, Andrew, Hauck, Landschützer, Le Quéré, Li, Luijkx, Olsen, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Schwingshackl, Sitch, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Alin and Zeng2025) on decadal time scales, signs of strain are emerging. In addition to the well-known long-term carbon loss from tropical systems due to deforestation and forest degradation (Gatti et al., Reference Gatti, Basso, Miller, Gloor, Gatti Domingues, Cassol, Tejada, Aragão, Nobre, Peters, Marani, Arai, Sanches, Corrêa, Anderson, Von Randow, Correia, Crispim and Neves2021, Carle et al., Reference Carle, Bauman, Evans, Coughlin, Binks, Ford, Bradford, Nicotra, Murphy and Meir2025), carbon stored in boreal forest and permafrost ecosystems also shows signs of strain. However, these signals are often driven by noisy disturbances linked to changing climatic and land-use stresses — disturbances whose long term effects on the carbon sink are still not fully understood. For example in 2023 significantly less carbon was absorbed by land ecosystems compared to the previous year, driven predominantly by drought and warming-related losses from tropical ecosystems and fire-related losses in boreal forests (Ke et al., Reference Ke, Ciais, Sitch, Li, Bastos, Liu, Xu, Gui, Bian, Goll, Xi, Li, O'Sullivan, de Souza, Friedlingstein and Chevallier2024). The decline adds to concerns that increasing trends in the drivers of carbon sink loss – including wildfires, droughts, heatwaves, and permafrost thaw – are weakening the natural land carbon sink and threaten to overwhelm possible growth gains from higher CO2 concentration in the near future. If the land sink weakens, a larger fraction of human emissions will remain in the atmosphere, meaning lower cumulative GHG emissions would lead to higher warming than previously estimated (Burton et al., Reference Burton, Kelley, Burke, Mathison, Jones, Betts, Robertson, Teixeira, Cardoso and Anderson2024). Here we will look at the evidence of short and long-term changes in the global natural carbon sink on land, with a focus on emerging vulnerability in northern, extratropical land ecosystems.

The Global Carbon Project estimate of the natural land carbon sink (excluding emissions from land use and land-use change) in 2023 was 2.3 ± 1 GtC/yr, well below the 2022 La Niña-induced strong sink of 3.9 ± 1 GtC/yr, or the 2014–2023 average of 3.2 ± 0.9 GtC/yr (Friedlingstein et al., Reference Friedlingstein, O'Sullivan, Jones, Andrew, Hauck, Landschützer, Le Quéré, Li, Luijkx, Olsen, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Schwingshackl, Sitch, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Alin and Zeng2025). This decline occurred in a year with strong El Niño conditions and record-breaking high temperatures – the global average was 1.48°C above pre-industrial levels – and reflects a strong negative response of terrestrial ecosystems to extreme events (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Liu, Bowman, Pascolini-Campbell, Chatterjee, Pandey, Miyazaki, van der Werf, Wunch, Wennberg, Roehl and Sinha2024; Ke et al., Reference Ke, Ciais, Sitch, Li, Bastos, Liu, Xu, Gui, Bian, Goll, Xi, Li, O'Sullivan, de Souza, Friedlingstein and Chevallier2024). However, comparing changes in the land carbon sink across studies is difficult due to variations in model ensembles, assumptions, and included processes. For example, the notably lower land carbon sink value reported by Ke et al. (Reference Ke, Ciais, Sitch, Li, Bastos, Liu, Xu, Gui, Bian, Goll, Xi, Li, O'Sullivan, de Souza, Friedlingstein and Chevallier2024) partly results from including land-use emissions of about 1 ± 0.7 GtC/yr in 2023, which lowered the overall mean land carbon sink compared to Friedlingstein et al. (Reference Friedlingstein, O'Sullivan, Jones, Andrew, Hauck, Landschützer, Le Quéré, Li, Luijkx, Olsen, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Schwingshackl, Sitch, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Alin and Zeng2025), alongside differences in vegetation model ensembles. After accounting for land-use emissions and uncertainty ranges, the two studies' results roughly align.

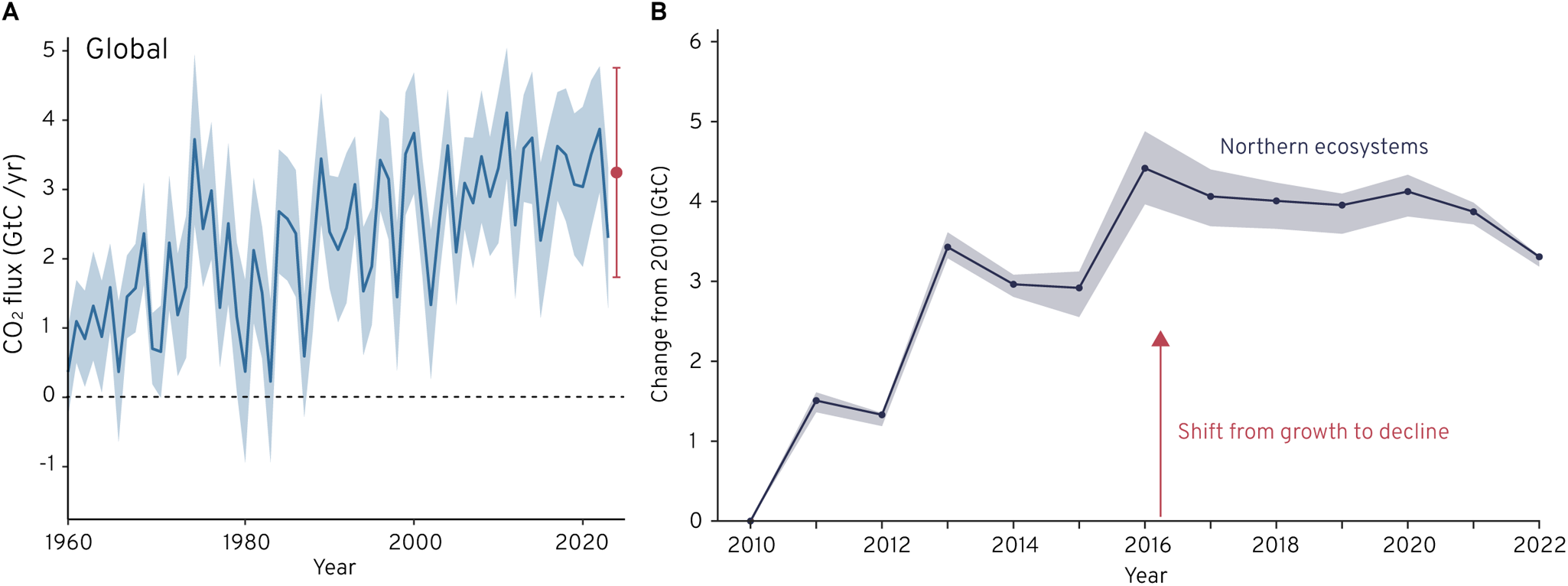

Interannual variability in the land carbon sink is expected, with large drops in the land carbon sink having occurred in the past (Figure 3A), usually in conjunction with El Niño years, followed by a recovery. Indeed, the global natural land sink rebounded somewhat in early 2024 (Friedlingstein et al., Reference Friedlingstein, O'Sullivan, Jones, Andrew, Hauck, Landschützer, Le Quéré, Li, Luijkx, Olsen, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Schwingshackl, Sitch, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Alin and Zeng2025; Ke et al., Reference Ke, Ciais, Sitch, Li, Bastos, Liu, Xu, Gui, Bian, Goll, Xi, Li, O'Sullivan, de Souza, Friedlingstein and Chevallier2024). Whether a long-term decline is underway may depend on whether the record warmth and widespread extremes of 2023–24 reflect typical variability layered on long-term warming, or mark a deeper shift in the climate system (the confluence of factors, in addition to rising atmospheric GHG concentrations, leading to the anomalous warmth in 2023–24 are discussed in Insight 1).

Figure 3. Temporal evolution of the global land carbon sink and associated uncertainties from 1960 to 2023 and recent changes in live biomass in northern ecosystems. (A) Global CO2 flux (GtC/yr) is shown. Positive values indicate an increase in the land carbon sink. The dark line represents the annual mean net fluxes, with the shaded area denoting ± 1 standard deviation uncertainty. The red dot shows the projected land carbon sink for 2024 with associated uncertainty. Data are from the Global Carbon Budget 2024 (Friedlingstein et al., Reference Friedlingstein, O'Sullivan, Jones, Andrew, Hauck, Landschützer, Le Quéré, Li, Luijkx, Olsen, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Schwingshackl, Sitch, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Alin and Zeng2025). (B) Annual variations in live biomass carbon stocks, expressed as the difference from 2010 values in northern ecosystems. Data available from X. Li et al. (Reference Li, Ciais, Fensholt, Chave, Sitch, Canadell, Brandt, Fan, Xiao, Tao, Wang, Albergel, Yang, Frappart, Wang, Bastos, Maisongrande, Qin, Xing and Wigneron2025).

In 2023, above average amounts of carbon were released to the atmosphere from multiple terrestrial biomes, but with different drivers and underlying temporal dynamics. The largest carbon release came from tropical ecosystems, which declined by 58% (from 2.8 GtC/yr to 1.2 GtC/yr) between 2022 and 2023 (Friedlingstein et al., Reference Friedlingstein, O'Sullivan, Jones, Andrew, Hauck, Landschützer, Le Quéré, Li, Luijkx, Olsen, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Schwingshackl, Sitch, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Alin and Zeng2025). This decline was driven primarily by El-Nino-influenced warming and drying, leading to reduced vegetation productivity in water-limited Sahel and southern Africa (Botía et al., Reference Botía, Dias-Junior, Komiya, van der Woude, Terristi, de Kok, Koren, van Asperen, Jones, D'Oliveira, Weber, Marques-Filho, Toro, Araújo, Lavric, Walter, Li, Wigneron, Stocker and Bastos2025; Gui et al., Reference Gui, Wang, Jin, Wang, Deng, Li, Tian, Wang, Chen, Wang and Piao2024), as well as reduced vegetation carbon uptake in the Amazon region (Botía et al., Reference Botía, Dias-Junior, Komiya, van der Woude, Terristi, de Kok, Koren, van Asperen, Jones, D'Oliveira, Weber, Marques-Filho, Toro, Araújo, Lavric, Walter, Li, Wigneron, Stocker and Bastos2025). The estimate of the tropical land carbon sink may be affected by misrepresentation of phosphorus limitation in many vegetation models, which would imply that the true decline was even larger (O'Sullivan et al., Reference O'Sullivan, Sitch, Friedlingstein, Luijkx, Peters, Rosan, Arneth, Arora, Chandra, Chevallier, Ciais, Falk, Feng, Gasser, Houghton, Jain, Kato, Kennedy, Knauer and Zaehle2024).

Providing equivalent estimates for northern extra-tropical ecosystems is particularly challenging for 2023 because of the dominant influence of extreme wildfire emissions (Jones, Kelley, et al. Reference Jones, Kelley, Burton, Di Giuseppe, Barbosa, Brambleby, Hartley, Lombardi, Mataveli, McNorton, Spuler, Wessel, Abatzoglou, Anderson, Andela, Archibald, Armenteras, Burke, Carmenta and Xanthopoulos2024; Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Liu, Bowman, Pascolini-Campbell, Chatterjee, Pandey, Miyazaki, van der Werf, Wunch, Wennberg, Roehl and Sinha2024). Current vegetation models used to produce the estimates, systematically underrepresent such intense high-latitude fire seasons, (Hantson et al., Reference Hantson, Arneth, Harrison, Kelley, Prentice, Rabin, Archibald, Mouillot, Arnold, Artaxo, Bachelet, Ciais, Forrest, Friedlingstein, Hickler, Kaplan, Kloster, Knorr, Lasslop and Yue2016; Hantson, Kelley, et al., Reference Hantson, Kelley, Arneth, Harrison, Archibald, Bachelet, Forrest, Hickler, Lasslop, Li, Mangeon, Melton, Nieradzik, Rabin, Prentice, Sheehan, Sitch, Teckentrup, Voulgarakis and Yue2020) meaning that model-based estimates would have failed to capture the unusually large carbon release from the 2023 Canadian fires. These models have also been shown to systematically underestimate the northern land carbon sink by ∼1 GtC (O'Sullivan et al., Reference O'Sullivan, Sitch, Friedlingstein, Luijkx, Peters, Rosan, Arneth, Arora, Chandra, Chevallier, Ciais, Falk, Feng, Gasser, Houghton, Jain, Kato, Kennedy, Knauer and Zaehle2024), not least due to misrepresentation of regrowth rates after fire. Nonetheless, observational evidence points to significant release of carbon from wildfires in the Canadian boreal forests in 2023 (0.65 ± 0.08 GtC) (Byrne et al., Reference Byrne, Liu, Bowman, Pascolini-Campbell, Chatterjee, Pandey, Miyazaki, van der Werf, Wunch, Wennberg, Roehl and Sinha2024; Friedlingstein et al., Reference Friedlingstein, O'Sullivan, Jones, Andrew, Hauck, Landschützer, Le Quéré, Li, Luijkx, Olsen, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Schwingshackl, Sitch, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Alin and Zeng2025), which contributed to record-breaking fire emissions in boreal forests globally in 2023 (Jones, Kelley, et al., 2024). These disturbance-driven fluxes, which have also emerged during recent Arctic fire seasons, make it difficult to constrain northern land-sink behaviour during years with exceptional high-latitude fire activity.

Although it is difficult to quantify the net northern extra-tropical land carbon sink in any single year, long-term assessments and evidence from individual disturbance processes suggest the land carbon sink in northern extra-tropical ecosystems – long considered more resilient to climate change than tropical forests – is showing signs of weakening. Although still a net carbon sink, recent studies using both empirical and model-based approaches indicate a longer-term flattening off or even decline over the past few decades (Friedlingstein et al., Reference Friedlingstein, O'Sullivan, Jones, Andrew, Hauck, Landschützer, Le Quéré, Li, Luijkx, Olsen, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Schwingshackl, Sitch, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Alin and Zeng2025; Ke et al., Reference Ke, Ciais, Sitch, Li, Bastos, Liu, Xu, Gui, Bian, Goll, Xi, Li, O'Sullivan, de Souza, Friedlingstein and Chevallier2024; Virkkala et al., Reference Virkkala, Rogers, Watts, Arndt, Potter, Wargowsky, Schuur, See, Mauritz, Boike, Bret-Harte, Burke, Burrell, Chae, Chatterjee, Chevallier, Christensen, Commane, Dolman and Natali2025). In the most recent decade, increasing drought-related tree mortality, insect outbreaks and wildfires have driven a shift from growth to decline in live carbon biomass (X. Li et al., Reference Li, Ciais, Fensholt, Chave, Sitch, Canadell, Brandt, Fan, Xiao, Tao, Wang, Albergel, Yang, Frappart, Wang, Bastos, Maisongrande, Qin, Xing and Wigneron2025) (a significant component of the land carbon sink; see Figure 3B) in northern extra-tropical land ecosystems, even without considering changes that occurred in 2023. This trend shift may be a sign of accelerating carbon transfer from vegetation to the atmosphere (X. Li et al., Reference Li, Ciais, Fensholt, Chave, Sitch, Canadell, Brandt, Fan, Xiao, Tao, Wang, Albergel, Yang, Frappart, Wang, Bastos, Maisongrande, Qin, Xing and Wigneron2025) and an indication of growing instability in northern extra-tropical land ecosystems (Romanou et al., Reference Romanou, Hegerl, Seneviratne, Abis, Bastos, Conversi, Landolfi, Kim, Lerner, Mekus, Otto-Bliesner, Pausata, Pinto and Suarez-Guiterrez2024).

Carbon uptake in boreal forests – one key biome within northern extra-topical land ecosystems – has declined significantly in recent decades due to fires, as well as insect outbreaks, drought and abnormal heat-induced mortality (Ramage et al., Reference Ramage, Kuhn, Virkkala, Voigt, Marushchak, Bastos, Biasi, Canadell, Ciais, López-Blanco, Natali, Olefeldt, Potter, Poulter, Rogers, Schuur, Treat, Turetsky, Watts and Hugelius2024; Virkkala et al., Reference Virkkala, Rogers, Watts, Arndt, Potter, Wargowsky, Schuur, See, Mauritz, Boike, Bret-Harte, Burke, Burrell, Chae, Chatterjee, Chevallier, Christensen, Commane, Dolman and Natali2025; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Veraverbeke, Andela, Doerr, Kolden, Mataveli, Pettinari, Le Quéré, Rosan, Van Der Werf, Van Wees and Abatzoglou2024). When additionally including emissions from land-use change and management, average annual carbon uptake in boreal forests – including in live biomass, soils, dead wood and litter – decreased by 36% between the decade 2010 and 2019 and the previous two decades (Pan et al., Reference Pan, Birdsey, Phillips, Houghton, Fang, Kauppi, Keith, Kurz, Ito, Lewis, Nabuurs, Shvidenko, Hashimoto, Lerink, Schepaschenko, Castanho and Murdiyarso2024). At the global level, this large loss was compensated by increases in carbon sinks in tropical regrowth and temperate forests, keeping the global forest carbon sink stable on average (Pan et al., Reference Pan, Birdsey, Phillips, Houghton, Fang, Kauppi, Keith, Kurz, Ito, Lewis, Nabuurs, Shvidenko, Hashimoto, Lerink, Schepaschenko, Castanho and Murdiyarso2024).

Thirty percent of the Arctic-boreal zone as a whole, which covers both the boreal biome and the treeless tundra, has become a net source of CO2. Furthermore, evidence suggests that the Tundra biome alone is no longer a net CO2 sink (Ramage et al., Reference Ramage, Kuhn, Virkkala, Voigt, Marushchak, Bastos, Biasi, Canadell, Ciais, López-Blanco, Natali, Olefeldt, Potter, Poulter, Rogers, Schuur, Treat, Turetsky, Watts and Hugelius2024; Virkkala et al., Reference Virkkala, Rogers, Watts, Arndt, Potter, Wargowsky, Schuur, See, Mauritz, Boike, Bret-Harte, Burke, Burrell, Chae, Chatterjee, Chevallier, Christensen, Commane, Dolman and Natali2025). Whether or not these regions have become a net carbon sink would require a full GHG inventory (including CO₂, CH4, and N₂O), which is not currently available. However, for the northern permafrost region, which covers ca. 65% of the Arctic-boreal zone, a full GHG inventory allows for calculation of the land carbon sink. Characterised by perennially frozen soils and home to Earth's largest soil carbon pool, its carbon uptake capacity is undergoing profound, warming-induced changes. Having acted as a carbon sink for decades, the most recent budgets identify the northern permafrost region as a net carbon source of 0.14 Gt C/yr (−0.51, 0.83; 95% confidence interval) over short decadal time scales (2000-2020) (Hugelius et al., Reference Hugelius, Ramage, Burke, Chatterjee, Smallman, Aalto, Bastos, Biasi, Canadell, Chandra, Chevallier, Ciais, Chang, Feng, Jones, Kleinen, Kuhn, Lauerwald, Liu and Zheng2024; Ramage et al., Reference Ramage, Kuhn, Virkkala, Voigt, Marushchak, Bastos, Biasi, Canadell, Ciais, López-Blanco, Natali, Olefeldt, Potter, Poulter, Rogers, Schuur, Treat, Turetsky, Watts and Hugelius2024). This shift is partly due to emissions from inland waters, fires, and abrupt permafrost thaw (Ramage et al., Reference Ramage, Kuhn, Virkkala, Voigt, Marushchak, Bastos, Biasi, Canadell, Ciais, López-Blanco, Natali, Olefeldt, Potter, Poulter, Rogers, Schuur, Treat, Turetsky, Watts and Hugelius2024; Virkkala et al., Reference Virkkala, Rogers, Watts, Arndt, Potter, Wargowsky, Schuur, See, Mauritz, Boike, Bret-Harte, Burke, Burrell, Chae, Chatterjee, Chevallier, Christensen, Commane, Dolman and Natali2025).

Understanding the long-term fate of the land carbon sink, in particular in northern extra-tropical ecosystems, remains a challenge. Much depends on the impact of extreme events on the land carbon sink in general. While additional emissions from wildfires – not least in the boreal region (Corning et al. Reference Corning, Krasovskiy, Kiparisov, San Pedro, Viana and Kraxner2024) – are expected to reach up to 5% of the remaining carbon budget for 2°C (Burton et al., Reference Burton, Kelley, Burke, Mathison, Jones, Betts, Robertson, Teixeira, Cardoso and Anderson2024), aerosol emissions from fires may indeed reduce future warming (Blanchard-Wrigglesworth et al., Reference Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, DeRepentigny and Frierson2025). Furthermore, the amount of carbon remaining in the atmosphere or reabsorbed by the land surface after events like fires and droughts depends on the pace and extent of recovery, which remain uncertain (Hamilton et al., Reference Hamilton, Kasoar, Bergas-Massó, Dalmonech, Hantson, Lasslop, Voulgarakis and Wells2024; Martínez-García et al., Reference Martínez-García, Nilsson, Laudon, Lundmark, Fransson, Wallerman and Peichl2024; O'Sullivan et al., Reference O'Sullivan, Sitch, Friedlingstein, Luijkx, Peters, Rosan, Arneth, Arora, Chandra, Chevallier, Ciais, Falk, Feng, Gasser, Houghton, Jain, Kato, Kennedy, Knauer and Zaehle2024).

Because of, and not despite these uncertainties, as global temperatures continue to rise, the capacity of land ecosystems to buffer climate change cannot be taken for granted. Strengthening this understanding is not just a scientific priority – it provides a critical foundation for credible climate policy.

Insight 4. Climate change and biodiversity loss reinforce one another

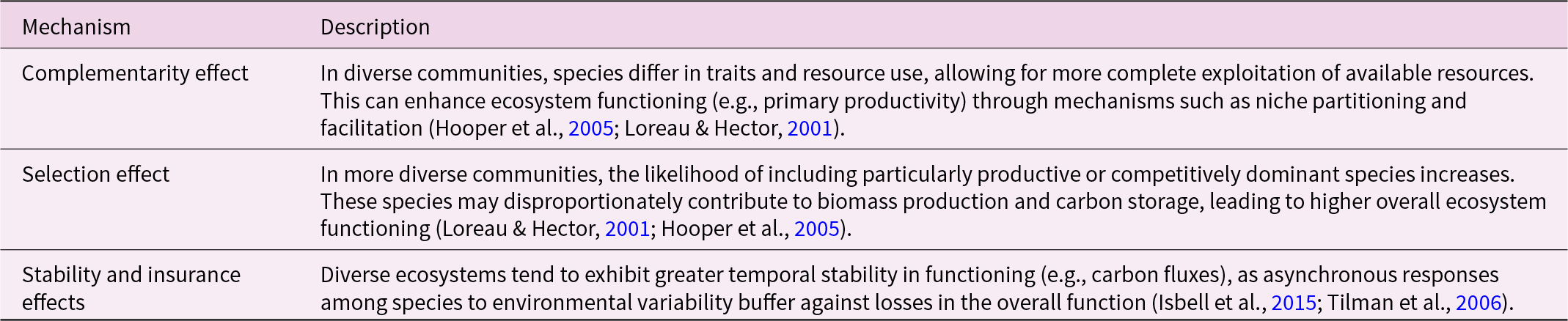

Climate change and biodiversity loss are two of the most pressing and interlinked environmental challenges that humanity is facing (Pfenning-Butterworth et al., Reference Pfenning-Butterworth, Buckley, Drake, Farner, Farrell, Gehman, Mordecai, Stephens, Gittleman and Davies2024; Pörtner et al., Reference Pörtner, Scholes, Arneth, Barnes, Burrows, Diamond, Duarte, Kiessling, Leadley, Managi, McElwee, Midgley, Ngo, Obura, Pascual, Sankaran, Shin and Val2023). Multiple studies have demonstrated the potential impact of climate change on biodiversity from local to global scales, with 3–6 million (or more) animal and plant species threatened, even under intermediate climate change scenarios (Wiens & Zelinka, Reference Wiens and Zelinka2024). However, increasing evidence suggests that a loss of biodiversity also impacts climate change, thereby contributing to a destabilising feedback directly impacting global climate stability. Experimental and observational studies have consistently found that higher plant diversity on lands can increase ecosystem functioning, including carbon storage, and these effects grow stronger over time (see Table 1 for mechanisms; (O'Connor et al., Reference O'Connor, Gonzalez, Byrnes, Cardinale, Duffy, Gamfeldt, Griffin, Hooper, Hungate, Paquette, Thompson, Dee and Dolan2017; S. S. Wang et al., Reference Wang, Isbell, Deng, Hong, Dee, Thompson and Loreau2021)).

Table 1. Mechanisms behind the biodiversity-carbon storage relationship

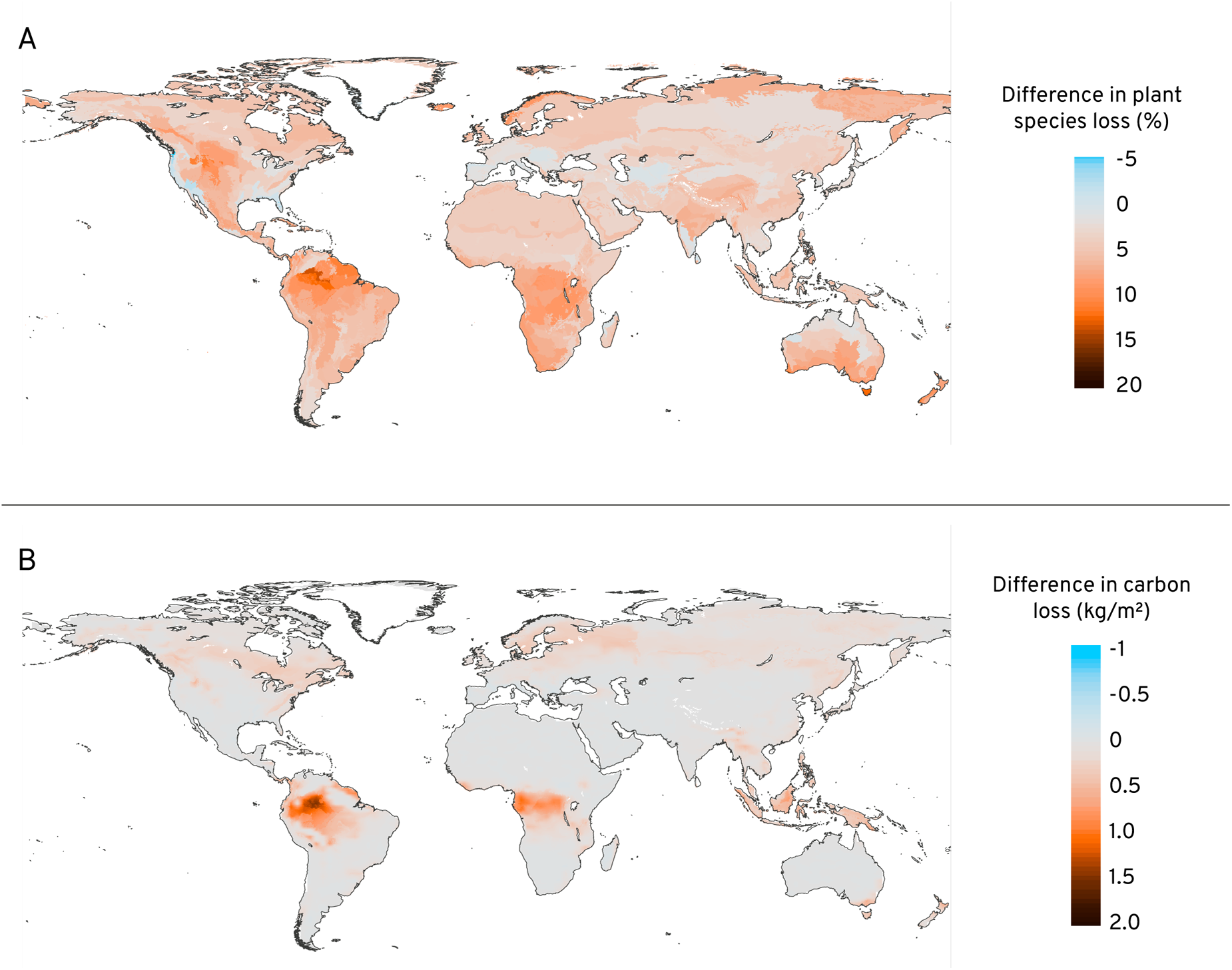

Because higher plant diversity leads to greater biomass within a place over time, loss of plant diversity from climate and land-use change can lead to biomass stock loss, and therefore carbon emissions (Lange et al., Reference Lange, Eisenhauer, Sierra, Bessler, Engels, Griffiths, Mellado-Vázquez, Malik, Roy, Scheu, Steinbeiss, Thomson, Trumbore and Gleixner2015; Mori et al., Reference Mori, Dee, Gonzalez, Ohashi, Cowles, Wright, Loreau, Hautier, Newbold, Reich, Matsui, Takeuchi, Okada, Seidl and Isbell2021). Weiskopf et al. (Reference Weiskopf, Isbell, Arce-Plata, Di Marco, Harfoot, Johnson, Lerman, Miller, Morelli, Mori, Weng and Ferrier2024) found that projected global plant species loss could lead to the emission of 7-145 PgC in the coming decades (Figure 4). Although the uncertainty range is large, the high-end estimates constitute a substantial portion of the remaining carbon budget before warming exceeds 1.5 or 2°C (Canadell et al., Reference Canadell, Monteiro, Costa, Cotrim da Cunha, Cox, Eliseev, Henson, Ishii, Jaccard, Koven, Lohila, Patra, Piao, Rogelj, Syampungani, Zaehle, Zickfe, Masson-Delmotte, Zhai, Pirani, Connors, Péan, Berger, Caud, Chen, Goldfarb, Gomis, Huang, Leitzell, Lonnoy, Matthews, Maycock, Waterfield, Yelekçi, Yu and Zhou2023). Similarly, Mori et al. (Reference Mori, Dee, Gonzalez, Ohashi, Cowles, Wright, Loreau, Hautier, Newbold, Reich, Matsui, Takeuchi, Okada, Seidl and Isbell2021) found that conserving tree diversity through climate change mitigation could correspond to 2–3 Gt C per year in reduced emissions.

Figure 4. Additional plant diversity loss and resulting carbon loss, under a very high emissions scenario. Long-term loss of vascular plant species richness due to climate change and land use change, projected by 2050 (A), expressed as additional percentage loss under a high emissions scenario (RCP8.5) relative to a low emissions scenario (RCP2.6). Reductions in vegetation carbon within the remaining habitat, attributable to plant biodiversity loss (B), expressed as additional carbon loss [kg/m2] under high emissions scenario (RCP8.5) relative to a low emissions scenario (RCP2.6). Adapted from Weiskopf et al. (Reference Weiskopf, Isbell, Arce-Plata, Di Marco, Harfoot, Johnson, Lerman, Miller, Morelli, Mori, Weng and Ferrier2024).

Although the role of plant diversity on ecosystem functioning is well established, the strength of the relationship can vary across biomes and environmental conditions. Large-scale analyses, for example, have shown stronger biodiversity-productivity relationships in less productive ecosystems (García-Palacios et al., Reference García-Palacios, Gross, Gaitán and Maestre2018; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Crowther, Picard, Wiser, Zhou, Alberti, Schulze, McGuire, Bozzato, Pretzsch, De-miguel, Paquette, Hérault, Scherer-Lorenzen, Barrett, Glick, Hengeveld, Nabuurs, Pfautsch and Reich2016; Paquette & Messier, Reference Paquette and Messier2011). Similarly, Spohn et al. (Reference Spohn, Bagchi, Biederman, Borer, Bråthen, Bugalho, Caldeira, Catford, Collins, Eisenhauer, Hagenah, Haider, Hautier, Knops, Koerner, Laanisto, Lekberg, Martina, Martinson and Yahdjian2023) found that the effects of plant diversity on soil organic carbon storage were stronger at drier sites. To reduce uncertainties regarding carbon release associated with biodiversity loss, further research across distinct biomes is needed to clarify the ecological mechanisms underlying variations in the biodiversity–carbon storage relationship along environmental gradients and differences in species and plant functional composition.

As an example, while tree diversity can enhance carbon sequestration and carbon retention in agroforestry systems (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Chen, Bork, Carlyle and Chang2020), it remains less clear if increasing plant diversity within cropland agroecosystems can have a similar effect. A recent study that evaluated a large field trial that manipulated plant diversity by combining undersown species with a cereal crop (i.e., barley) showed that increasing plant diversity within agroecosystems can also increase the carbon retention potential in soils (Domeignoz-Horta et al., Reference Domeignoz-Horta, Cappelli, Shrestha, Gerin, Lohila, Heinonsalo, Nelson, Kahmen, Duan, Sebag, Verrecchia and Laine2024), without compromising productivity. This confirms previous studies suggesting that manipulating plant diversity can enhance plant productivity and positively influence the associations between microorganisms, increasing microbial growth efficiency, which is considered a driver of soil carbon storage (Lange et al., Reference Lange, Eisenhauer, Sierra, Bessler, Engels, Griffiths, Mellado-Vázquez, Malik, Roy, Scheu, Steinbeiss, Thomson, Trumbore and Gleixner2015; Tao et al., Reference Tao, Huang, Hungate, Manzoni, Frey, Schmidt, Reichstein, Carvalhais, Ciais, Jiang, Lehmann, Wang, Houlton, Ahrens, Mishra, Hugelius, Hocking, Lu, Shi and Luo2023).

While uncertainties exist, plant–animal interactions and ecosystem functions, for instance, through trophic chains, can potentially alter vegetation structure and plant species composition, which in turn can affect above and belowground biomass (Back et al., Reference Back, Pérez-Postigo, Geitner and Arneth2025; Bello et al., Reference Bello, Crowther, Ramos, Morán-López, Pizo and Dent2024; Brodie et al., Reference Brodie, Bello, Emer, Galetti, Luskin, Osuri, Peres, Stoll, Villar and López2025; Török et al., Reference Török, Bullock, Jiménez-Alfaro and Sonkoly2020). For example, simulation studies show that elephants in African forests increase aboveground biomass by promoting high wood-density trees and dispersing seeds of large trees (Berzaghi et al., Reference Berzaghi, Bretagnolle, Durand-Bessart and Blake2023, Reference Berzaghi, Longo, Ciais, Blake, Bretagnolle, Vieira, Scaranello, Scarascia-Mugnozza and Doughty2019), whereas in African savannas, remote sensing and ground experiments indicate that reduced herbivores resulted in higher biomass (Back et al., Reference Back, Pérez-Postigo, Geitner and Arneth2025). In tropical systems, defaunation could reduce carbon storage up to 26%, primarily driven by population declines in animal-dispersed tree species (Brodie et al., Reference Brodie, Bello, Emer, Galetti, Luskin, Osuri, Peres, Stoll, Villar and López2025). In the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, a study quantified that frugivores can potentially enhance carbon recovery in fragmented forest landscapes when at least 40% forest cover remains (Bello et al., Reference Bello, Crowther, Ramos, Morán-López, Pizo and Dent2024). Climate change may disproportionately affect specialised guilds, such as frugivores, especially in the tropics (Mendoza & Araújo, Reference Mendoza and Araújo2025). Independent of these species interactions, evidence demonstrating the role of terrestrial animals as contributors to climate solutions is limited and remains contested (Duvall et al., Reference Duvall, le Roux, Pearson, Roman, Malhi and Abraham2024).

Animals can also impact carbon storage in the oceans. For example, due to their large size, whales can sequester carbon as biomass, which then sinks to the ocean floor after death, promoting carbon sequestration (Durfort et al., Reference Durfort, Mariani, Tulloch, Savoca, Troussellier and Mouillot2022; Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Savoca, Costa, Lomas, Molina, Pershing, Smith, Villaseñor-Derbez, Wing and Roman2024). The recovery of baleen whale populations and their nutrient recycling services could enhance productivity and help restore ecosystem functions lost during 20th-century whaling (Savoca et al., Reference Savoca, Czapanskiy, Kahane-Rapport, Gough, Fahlbusch, Bierlich, Segre, Di Clemente, Penry, Wiley, Calambokidis, Nowacek, Johnston, Pyenson, Friedlaender, Hazen and Goldbogen2021). However, the carbon benefits associated with this recovery are increasingly threatened by climate change (Durfort et al., Reference Durfort, Mariani, Tulloch, Savoca, Troussellier and Mouillot2022; Tulloch et al., Reference Tulloch, Plagányi, Brown, Richardson and Matear2019).

While knowledge gaps remain, multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches to understand the social, ecological, and physical processes involving biodiversity loss and climate change through carbon uptake, release and protection are critical in assessing the entire destabilising feedback mechanisms. Because of such feedback, meeting the targets of the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework can directly contribute to countries' Nationally Determined Contributions under the UNFCCC by reducing biodiversity-loss-driven carbon debt. Recognising and acting upon the interdependence between biodiversity conservation and restoration and effective climate mitigation would improve our ability to meet the climate and biodiversity policy targets. Despite the importance of biodiversity to store carbon, many existing natural climate-solution initiatives focus on ecosystem extent and cover, such as forested areas, rather than quality and composition (Mori, Reference Mori2020; Seddon et al., Reference Seddon, Turner, Berry, Chausson and Girardin2019), which could lower effectiveness as carbon sinks. Likewise, many conservation efforts focus on species, often charismatic ones, rather than maintaining species interactions and their role for ecosystem function (Tobias et al., Reference Tobias, Bullock, Dicks, Forester and Razgour2025). Maintaining and restoring diverse ecosystems while considering Indigenous and traditional knowledge and livelihoods can be effective actions towards achieving sustainability in the face of multiple global crises (Levis et al., Reference Levis, Flores, Campos-Silva, Peroni, Staal, Padgurschi, Dorshow, Moraes, Schmidt, Kuikuro, Kuikuro, Wauja, Kuikuro, Kuikuro, Fausto, Franchetto, Watling, Lima, Heckenberger and Clement2024; Razanatsoa et al., Reference Razanatsoa, Andriantsaralaza, Holmes, Rakotonarivo, Ratsifandrihamanana, Randriamiharisoa, Ravaloharimanitra, Ramahefamanana, Tahirinirainy and Raharimampionona2021) and therefore contributing to both biodiversity and climate agreements. Considering Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities can allow for location-specific and biome-specific analyses to inform local policies and contribute to global goals.

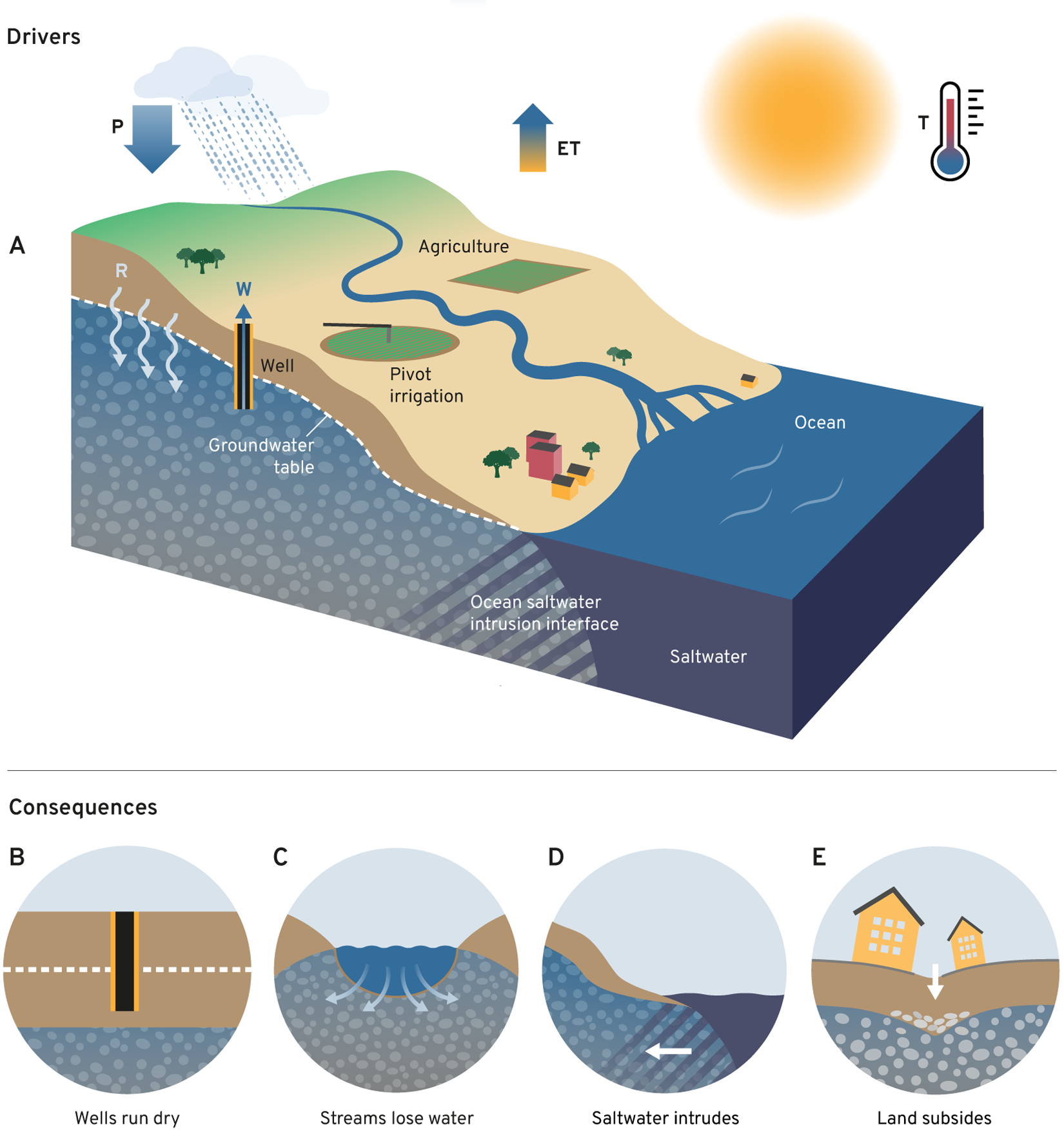

Insight 5. Accelerating depletion of groundwater

Groundwater is the second-largest freshwater resource after the polar caps and vital for almost half of the world's population. It anchors water and food security for millions of people, particularly in places with erratic rainfall patterns. Most of the pumped groundwater is used for irrigation, and the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization estimates a 30% increase in irrigated agriculture, especially in developing countries, in the coming decades. With the prediction of drier summers and less evenly distributed rainfall in many areas across the world, our reliance on groundwater as a stable resource will become even more important (UNESCO, 2022).