Introduction

Cancer is a major health issue in Germany, with an estimated more than 600,000 new cancer cases in 2022, making it one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality (Ferlay et al. Reference Ferlay, Ervik and Lam2024). One-third of all new cancer cases and deaths are solid tumors, such as breast, colorectal, and lung cancers, which are also among the top causes of cancer-related mortality in Germany (Ferlay et al. Reference Ferlay, Ervik and Lam2024). Cancer care involves a complex process that extends beyond the hospital walls and into patients’ homes. Caregiving is crucial to cancer patients and their families (Sun et al. Reference Sun, Raz and Kim2019). Family caregivers (FCs), defined here as relatives, friends, or partners who provide unpaid support to cancer patients, play a central role in cancer care (Lambert et al. Reference Lambert, Levesque, Girgis and Koczwara2016). FCs facilitate access to treatment, coordinate communication among healthcare providers, help patients understand and cope with medical information, and navigate the complexities of the healthcare system. FCs of advanced cancer patients encounter significant physical, emotional, social, and financial challenges that impact their overall well-being while tackling caregiving tasks, which leads to a dual burden (Goerling et al. Reference Goerling, Bergelt and Müller2020; Harrison et al. Reference Harrison, Raman and Walpola2021; Kent et al. Reference Kent, Rowland and Northouse2016; Lambert et al. Reference Lambert, Levesque, Girgis and Koczwara2016; Sherman Reference Sherman2019; Stenberg et al. Reference Stenberg, Ruland and Miaskowski2010; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Raz and Kim2019). Previous studies revealed common unmet needs among FCs in physical, psychological, and informational domains, including a frequent need for psychological support to address anxiety regarding disease recurrence or progression, as well as disease, treatment, and care-related information, making a dyadic approach to advanced cancer care essential (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Chiou and Yu2016; Crotty et al. Reference Crotty, Asan and Holt2020; Ferrell and Kravitz Reference Ferrell and Kravitz2017; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Carver and Ting2020; Ream et al. Reference Ream, Pedersen and Oakley2013; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Molassiotis and Chung2018; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Lee and Kuparasundram2021). This approach focuses on the shared assessment and management of illness by patients and caregivers (Lyons and Lee Reference Lyons and Lee2018). Advanced cancer patients’ psychological distress has been shown to significantly increase caregivers’ burden, disrupting family dynamics and daily life (Caruso et al. Reference Caruso, Nanni and Riba2017; Johansen et al. Reference Johansen, Cvancarova and Ruland2018; Li et al. Reference Li, Lin and Xu2018; Rhondali et al. Reference Rhondali, Chirac and Laurent2015).

Despite the importance of routine screening for caregivers’ needs, it is not yet established in Germany (Oechsle Reference Oechsle2019; Oechsle et al. Reference Oechsle, Theißen and Heckel2021). While some studies have focused on FCs in specialized palliative care inpatient units (Ullrich et al. Reference Ullrich, Marx and Bergelt2021), little is known about caregivers' challenges, needs, and support systems in outpatient cancer settings.

The primary objective of this study is to address this gap by adopting a dyadic approach to explore the experiences and needs of FCs of advanced cancer patients in outpatient settings in Germany. The study also seeks to identify suitable options for routine needs assessments and potential strategies for referring caregivers to appropriate support services, such as psychological counseling, social support networks, and informational resources. By including oncologists’ perspectives, it evaluates professional views on integrating FCs, identifies potential barriers, and explores ways to enhance needs assessments and caregiver support, ultimately improving care quality for both patients and caregivers.

Methods

Theoretical background

This qualitative study is grounded in the Theory of Dyadic Illness Management, which views illness management as an interdependent process between the patient and caregiver (Lyons and Lee Reference Lyons and Lee2018). This theory aligns with the study’s objectives of promoting regular, dyad-focused needs assessments that consider both the practical and emotional needs of FCs in outpatient cancer care, alongside those of the patient. By including oncologists’ perspectives, the study addresses the contextual factors outlined in the theory, examining available support and systemic barriers to caregiver integration. The framework seeks potential strategies to enhance caregiver support and improve overall dyadic care quality.

Study design

This study used a qualitative design. The COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) checklist was utilized for reporting (Tong et al. Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007).

Participants and recruitment

Participants were selected through collaboration with medical staff at the outpatient clinic at Charité Comprehensive Cancer Centre, using purposive sampling to achieve theoretical saturation (Hennink and Kaiser Reference Hennink and Kaiser2022). Physicians identified eligible patients and caregivers and provided them with detailed study information. Written informed consent was obtained from those interested in participating. Inclusion criteria for the patients comprised: (1) ≥18 years old; (2) being diagnosed with Stage IV solid tumor; (3) undergoing cancer treatment; (4) having a FC; and (5) speaking German. Eligibility criteria for the family caregivers included: (1) being identified by the patient as a primary caregiver providing unpaid care and support; (2) ≥18 years old; and (3) speaking German. The oncologists included in the study were those directly involved in the treatment of the participating patients and were working at the outpatient clinic, purposefully selected to represent clinical experiences relevant to the study’s objectives.

Data collection

The study included a needs evaluation survey adapted from the NCCN Distress Thermometer (DT) (Mehnert et al. Reference Mehnert, Müller and Lehmann2006). It covered various areas identified in prior caregiving research, such as the evaluation of emotional, social, financial, and informational needs of FCs, dyadic dynamics, and congruence. Participants, including patients and FCs, completed the survey before their regular consultation with the physician. This was done as a pilot to make their needs visible in the clinical routine. The survey informed the semi-structured interviews post-consultation, aiming to understand participants’ needs, identify gaps and challenges, and discuss additional support modalities vital to caregivers but not initially covered. A detailed description of the study’s tools can be found in the Appendix.

Qualitative interviews were conducted face-to-face in the outpatient clinic between January and September 2023 by the first author (P.Z.), a female PhD candidate in health services and communication research with previous experience and training in qualitative methods. The interviewer had no prior relationship with any of the participants, ensuring a neutral and professional interaction. The first 3 interviews served as pilots, and the interview guide was adjusted according to the experiences. The semi-structured interview guide used in this study is included in the Appendix. Most interviews involved patients and caregivers together, although exceptions were made if caregivers preferred separate sessions or if the patient’s health condition required individual interviews. The dyadic format fostered direct dialog between patients and caregivers, creating an interactive environment reflective of real-life experiences (Froschauer and Lueger Reference Froschauer and Lueger2020). The interviews with the physicians were conducted separately. Basic sociodemographic data (age, gender, and the relationship between caregiver and patient) were collected through brief surveys, while medical information (e.g., diagnosis and treatment status) was obtained from patient records.

Data analysis

This sociodemographic and medical data were analyzed using basic descriptive statistics in IBM SPSS Statistics 27. The interviews were conducted in German, recorded, transcribed, and translated into English by a bilingual researcher. Reflexive thematic analysis, following Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006), was performed using the six stages of data familiarization, inductive coding, initial theme generation, theme refinement, theme definition and naming, and reporting the findings (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2006). MAXQDA Analytics Pro 24 was used to organize codes into sub-themes and themes. The first author (P.Z.) conducted an open code of the transcripts, which were then grouped into larger categories to generate central themes. The authors (P.Z., U.G., S.G., C.K.) reviewed and refined these themes to ensure accuracy and depth. Participant confidentiality was maintained using pseudonyms and by anonymizing personal information. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Charité University of Medicine Berlin, Germany (EA4/185/22).

Results

Population

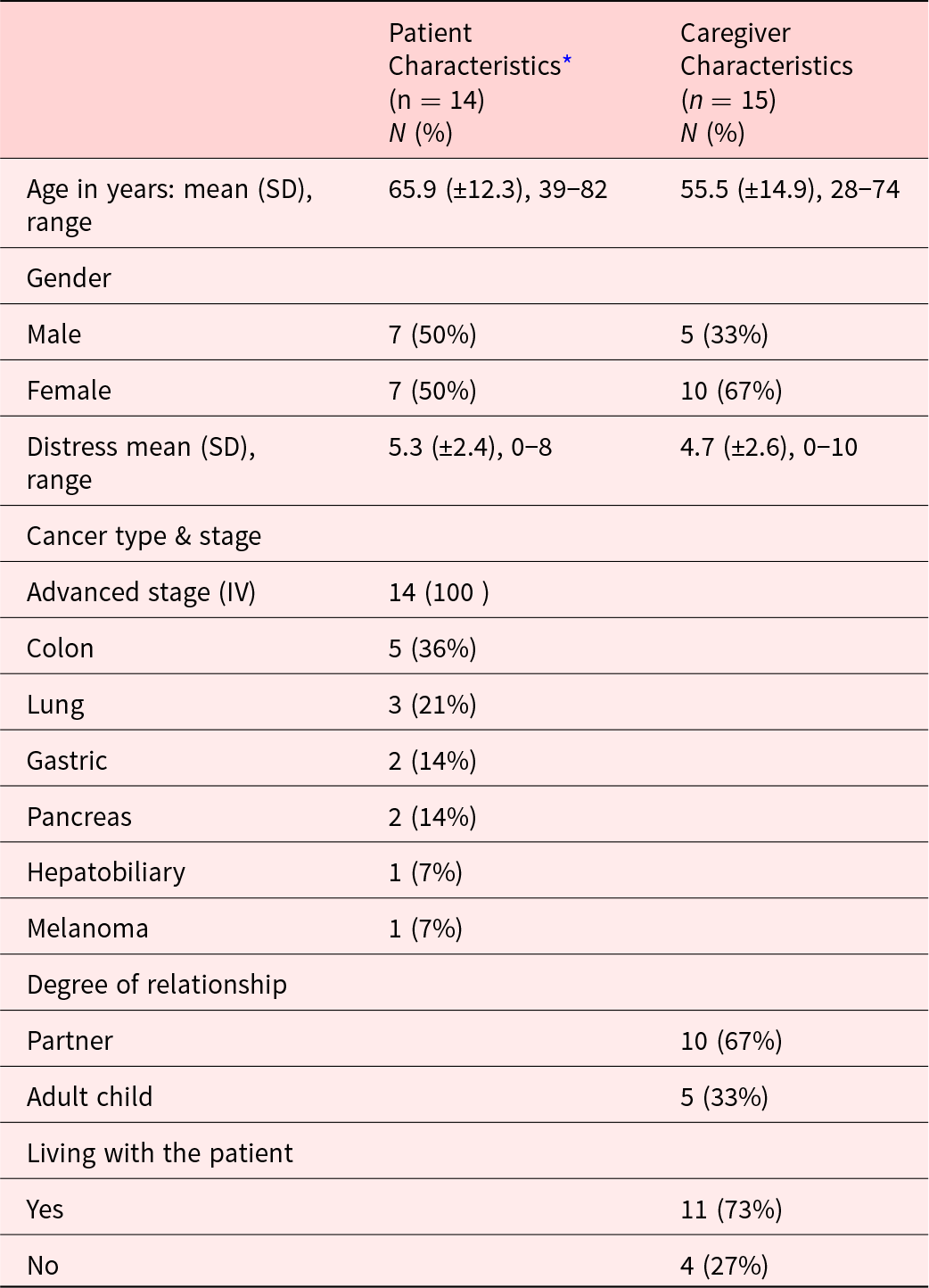

Fifteen interviews were conducted with 15 dyad couples, including 14 patients and 15 caregivers, with one patient having two primary caregivers (a son and daughter) at the outpatient clinic. While 11 interviews were conducted with the patient and caregiver together, four interviews were held solely with caregivers due to the patients’ health conditions or the caregivers’ requests. A summary of participant characteristics is presented in Table 1. Individual interviews were also conducted with 3 oncologists. The average length of the interviews was 25 minutes (SD = 7, range: 16–44 minutes).

Table 1. Patient and caregiver characteristics

* Note: Due to rounding, the numbers do not always add up to 100%.

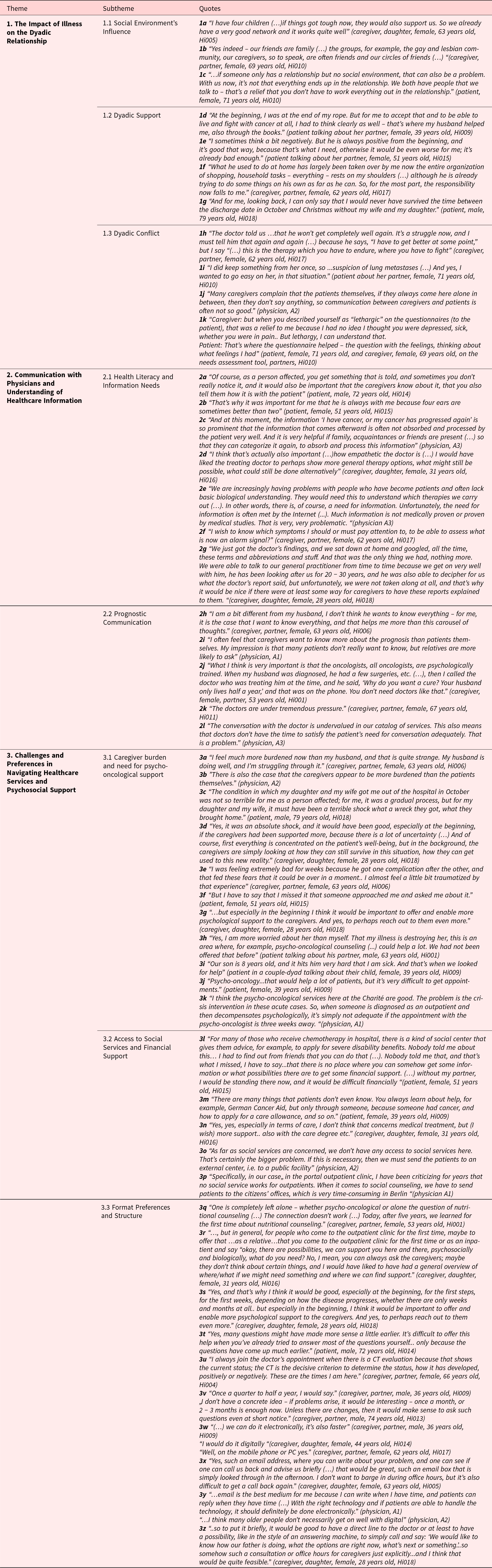

Three main themes emerged in the analysis and are presented together with subthemes and supporting quotes in Table 2 (1a–3z). The results are discussed by theme in the following section.

Table 2. Emergent themes and subthemes

Theme 1: The impact of illness on the dyadic relationship

This theme focuses on the complex interactions between cancer patients and their caregivers, considering mutual support and potential conflicts within their relationships.

Social environment’s influence

The study found that the patient-caregiver relationship was shaped by social factors impacting their well-being. Both groups emphasized the importance of external support networks in managing illness, especially for individuals in the LGBTQ + community, who often relied on chosen families and friends. Such supportive networks were found to be essential for strengthening the dyadic bond by reducing stress and enhancing resilience (1a–c).

Dyadic support

Dyadic support within patient–caregiver relationships was shown to be important. This included practical support, such as managing household tasks, coordinating medical appointments, handling medication, and understanding health information. Some FCs demonstrated coping strategies involving hope and optimism, which were expressed through emotional encouragement offered to the patient (1d–g).

Dyadic conflicts

Conflicts were also present in patient-caregiver dyads. Differences in perception of the illness could lead to mismatched expectations. For example, a patient’s optimistic outlook sometimes clashes with a caregiver’s more cautious perspective, causing frustration and emotional tension (1h). Patients sometimes chose to withhold information to shield their caregivers from stress, but this can undermine the trust that is essential for a strong relationship, as noted by caregivers and observed by physicians (1i–j). Addressing the emotional needs of both patients and caregivers was found to resolve conflicts. One patient–caregiver dyad reported that emotional assessments improved their communication and understanding, with the caregiver being reassured when the patient identified as “lethargic” in a survey, after initially assuming depression or pain in the patient (1k). Such examples underscore the value of regular reflexive assessments for both individuals.

Theme 2: Communication with physicians and understanding of healthcare information

Effective communication among physicians, patients, and caregivers is vital yet challenging. This theme emphasizes caregivers’ role in helping patients process medical information and highlights the importance of health literacy, addressing caregivers’ needs, and adapting prognostic communication strategies.

Health literacy and information needs

Understanding the disease situation and the treatment is an essential part of physician–patient–caregiver communication. The news of cancer or its progression can be overwhelming. Study participants and physicians highlighted the support given by FCs during interactions with doctors, helping to remember and process medical information (2a–c). Physicians addressed health literacy issues in caregivers and patients – particularly in using the internet as a knowledge source – as a challenge in shared decision-making (2e).

To better support their loved ones, FCs expressed a significant need for improved informational guidance, especially regarding medical reports, as highlighted by a caregiver who voiced the need for more disease-related information to better care for her husband (2f).

Prognostic communication

The study revealed that patients and their FCs might have different information needs, which presents challenges in discussing prognosis. FCs typically wanted detailed information to prepare for all outcomes, while patients preferred less detail, as perceived by the oncologists (2h–i). FCs tended to adopt a problem-solving approach, actively seeking information and communicating with healthcare professionals to address uncertainties. They mentioned that satisfying interactions with physicians involve empathy and thorough discussions of treatment options (2d, 2j). However, time constraints on doctors were highlighted as a significant barrier to effective communication, as noted by patients and physicians (2k–l).

Theme 3: Challenges and preferences in navigating healthcare services and psychosocial support

Caregiver burden, as a distinct theme at the individual level, is directly linked to the need for psychosocial support services at a structural level.

FCs face significant challenges when it comes to their needs and accessing healthcare services. While various services are available, there are gaps in the system that must be addressed.

Caregiver burden and the need for psycho-oncological support

FCs often feel more distressed than the patients, as noticed by both the patients and doctors, frequently prioritizing the patient’s needs over their own well-being (3a–c). Receiving a cancer diagnosis is especially shocking for most FCs, leading to feelings of helplessness, anxiety about the illness's progression, uncertainty regarding the prognosis, and concerns about changes in their own lives (3d–e). They expressed a need for more proactive psychological and social support to be offered earlier in the treatment process (3f–g).

Service integration issues were noted as some patients and caregivers were unaware of available psycho-oncological services, especially in outpatient care (3h). Younger couples with small children face unique challenges when one parent is diagnosed with cancer, as they must balance childcare responsibilities with caregiving (3i). Discussing the illness with their children can also be difficult, and long waiting times for psychological support further complicate these issues, leaving families without timely assistance during critical moments (3j). Oncologists identified this as a structural problem, recognizing the need for early assessments and immediate support following a diagnosis (3k).

Access to social services and financial support

The study revealed a clear need for better access to information regarding social benefits, financial aid, and other social services (3l–n). Participants emphasized the importance of proactive outreach and comprehensive lists of available resources. Physicians recognized the lack of social services in outpatient settings as a significant structural issue (3o–p).

Format preferences and structure

FCs stressed the need for better communication and support in the care process and emphasized challenges in accessing help due to structural barriers, indicating the need to address gaps in the system (3q–r). Early needs assessments were preferred by FCs, along with the implementation of a referral system for supportive services (3s–t). They suggested regular evaluations every 3–6 months or during significant treatment milestones, such as staging procedures or in cases of problem occurrences (3u–v). Most participants appreciated email communication for its flexibility, and FCs favored proactive support and digital tools (3w–x). While physicians found digital communication effective, they noted that paper-based options might still be necessary for older patients (3y). Improvement suggestions included establishing direct communication lines, voicemail options, and designated office hours for caregiver consultations (3z).

Discussion

This study explores the experiences and needs of FCs in advanced cancer care within German outpatient settings, identifying key themes: (1) The Impact of Illness on the Dyadic Relationship; (2) Communication with Physicians and Understanding of Healthcare Information; (3) Challenges and Preferences in Navigating Healthcare Services and Psychosocial Support. A unique aspect of the study is its inclusion of doctors’ preferences and the obstacles faced in providing psychosocial support, aiming to improve communication and collaboration among patients, caregivers, and oncologists. The research highlights the necessity for tailored support strategies and better resource awareness for FCs in this context.

While previous studies primarily focused on caregivers, this project integrates both patient and caregiver perspectives into a unified needs assessment framework. This approach highlights dyadic incongruence, such as differing views on the disease, emphasizing the interdependent nature of their needs. Unlike one-sided assessments, this method offers a more comprehensive view of support needs in palliative care. Findings suggest that regular joint assessments can address mismatched expectations and unmet needs, enhancing mutual understanding and care quality. Advance care planning is essential for aligning patient and caregiver expectations and reducing uncertainty about future needs. Early systematic integration of palliative care and structured conversations should be integrated into cancer care trajectories and can enhance care quality, lessen uncertainty, reduce caregiver burden, and ensure alignment with the patient’s values and preferences (El-Jawahri et al. Reference El-Jawahri, Waterman and Enguidanos2024; Hoerger and Cullen Reference Hoerger and Cullen2017; Pini et al. Reference Pini, Bekker and Bennett2022). While a recent German study examined doctors’ perceptions of involving caregivers in elderly care decision-making (Heidenreich et al. Reference Heidenreich, Elsner and Wörler2023), little is known about oncologists’ preferences for evaluating and addressing FC’ needs in routine care. A distinctive aspect of this study is its inclusion of physicians’ preferences and barriers in implementing psychosocial support structures. Given the specific outpatient setting, the study suggests effective caregiver integration strategies that accommodate the preferences of all three parties, ultimately providing tailored recommendations for enhancing the caregiving experience.

The current findings align with the existing literature, adding evidence to the previous studies. The project highlights significant emotional and informational challenges faced by FCs, corroborating prior research on their high caregiving burden and unmet needs (Bevans and Sternberg Reference Bevans and Sternberg2012; Girgis et al. Reference Girgis, Lambert and Johnson2013; Semere et al. Reference Semere, Althouse and White2020). It underscores the critical role of the social environment in providing practical and emotional support (Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Zhang and Wang2022). The social environment influences not only the well-being of patients and caregivers individually but also shapes the dynamics of their dyadic relationship. Positive social support can enhance dyadic coping by promoting shared understanding and reducing conflict, while a lack of support can negatively contribute to tension within the dyad.

The study emphasizes the significance of healthcare providers promoting transparent communication between patients and caregivers to improve their mutual understanding and disease management. It recommends tailoring communication to meet the specific needs of patients and caregivers, including effectively managing the complicated dynamics of sharing prognosis information. The study confirms prior research indicating misunderstandings about prognosis among cancer patients and their caregivers and highlights the importance of considering discordant prognostic information preferences within the patient-caregiver relationship in advanced cancer care (Applebaum et al. Reference Applebaum, Buda and Kryza-Lacombe2018; Gray et al. Reference Gray, Forst and Nipp2021; van der Velden et al. Reference van der Velden, Smets and Hagedoorn2023). The findings support the previous conclusions that caregivers and patients can have different prognostic awareness (Applebaum et al. Reference Applebaum, Gebert and Behrens2023; Diamond et al. Reference Diamond, Prigerson and Correa2017).

Furthermore, empathetic communication and support for disease understanding and prognostic awareness were vital aspects of the interaction between physicians, patients, and caregivers. This finding confirms the results of a previous study that highlighted the importance of such support throughout the cancer trajectory (Preisler et al. Reference Preisler, Heuse and Riemer2018). Additionally, the current study confirms earlier findings on substantial unmet information needs of caregivers concerning treatment, side effects, and symptom management (Cochrane et al. Reference Cochrane, Gallagher and Dunne2021). Beyond discussing treatment options and results, however, it is crucial for physicians to address end-of-life issues, explore patients’ values and preferences, and integrate palliative care early in the cancer care continuum to support quality of life. This holistic communication is essential to ensure that care aligns with the goals and desires of both patients and FCs.

The study introduces a dyadic approach to assess the needs of patients and caregivers within a shared framework, either together or separately, based on contextual considerations, and incorporates these elements into the established distress evaluation framework (Mehnert et al. Reference Mehnert, Müller and Lehmann2006). Linking the Theory of Dyadic Illness Management to the study’s results clarifies the shared coping strategies of cancer patients and caregivers, emphasizing the role of social networks and practical support in building resilience. The findings highlight “dyadic support,” where caregivers assist with medical appointments and household tasks, underscoring the importance of practical assistance. Emotional coping, such as caregivers fostering hope, shows how shared positivity helps through challenges. However, optimism can have a dual role – both supportive and possibly hindering shared decision-making through overestimation of benefits – which was not explicitly addressed in the interviews and warrants further exploration in future research. Conflicts from differing illness perceptions underscore the importance of enhancing communication and anticipation. This can be accomplished through advance care planning programs, which foster understanding between patients and caregivers.

Integrating caregivers’ assessment needs into routine care in German cancer outpatient settings aims to increase their visibility. While patients and caregivers welcomed needs assessments, timing is crucial, with a preference for early needs evaluation and immediate psychological support after diagnosis. The study revealed challenges regarding the integration of psychological services. Structural barriers, such as long waiting times and insufficient social services integration, must be addressed to improve care quality in outpatient settings. FCs preferred personalized and accessible support, including digital formats, indicating a demand for innovative solutions. These results are consistent with prior research highlighting the potential of new technologies in supporting caregivers across various disease contexts, such as dementia caregiving (Gris et al. Reference Gris, D’Amen and Lamura2023). While innovative tools provide valuable support, they must be viewed as supplements to, not replacements for, human-centered approaches that address caregivers’ needs. This study’s strengths lie in its comprehensive coverage of a wide range of experiences across different types of advanced solid tumors and age groups, including younger cancer patients and FCs who might face different challenges than older groups (Justin et al. Reference Justin, Lamore and Dorard2021). Additionally, incorporating the perspectives of physicians enriches the study. Qualitative methodology provides insights into participants’ experiences, and including LGBTQ + members added diversity to the study. This group often faces unique challenges, such as increased life stress and limited family support (Power et al. Reference Power, Ussher and Perz2022). The experiences of the LGBTQ + dyad in our study suggest a potential need for further research to explore the specific needs and resources of this population in more detail.

Limitations and future directions

This project has several limitations. Conducted at a single center with a qualitative approach, its findings have limited transferability. Most interviews included both patients and FCs, but some included only FCs, which may affect the results. Dyadic interviews might have restrained FCs from sharing sensitive emotions, and the limited sociodemographic data hinders our understanding of diverse caregiving contexts. Future research should include a broader range of sociodemographic variables. The study focused on German-speaking FCs of stage IV cancer patients, excluding earlier stages and non-German speakers, which limits transferability. It also concentrated on FCs of advanced cancer patients undergoing active treatment, who may perceive prognosis differently than those caring for patients receiving only palliative care. This distinction is crucial for interpretation. Future research should involve FCs from all disease stages for a broader range of supportive and palliative care experiences and consider diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Many patients and FCs reported their previous experiences retrospectively, potentially introducing bias. This highlights the need for future research to capture more immediate and unbiased insights into their initial needs.

This study focuses on the German healthcare system but may also have implications for outpatient care in other countries, as FCs of cancer patients often face similar challenges. However, cultural and systemic differences are important to consider. Future research should examine how caregiver needs are addressed in various cultural and healthcare settings to develop effective, context-sensitive interventions. Cross-cultural studies can aid in developing targeted interventions and policies, especially in resource-limited regions.

Conclusion

The findings of this study have significant practical implications for healthcare practice and policy. Healthcare systems should adopt a caregiver-inclusive approach that guarantees early inclusion of palliative care, provides easy access to information, proactive psychosocial support from the start of the cancer journey, and tailored communication with healthcare providers.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951525100242.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients, caregivers, and physicians for sharing their experiences.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest

There are no conflicts of interest.