Introduction

The interpretation of radiocarbon (14C) results and the reliability of the dates obtained from human bone collagen from the Canary Islands is questionable causing disagreement on human settlement hypotheses. Much of the dispute has focused on issues like the validity of dates from long-lived materials such as wood (Alberto-Barroso et al. Reference Alberto-Barroso, Delgado-Darias, Moreno-Benítez and Velasco-Vázquez2019; Velasco-Vázquez et al. Reference Velasco-Vázquez, Alberto-Barroso, Delgado-Darias, Moreno-Benítez, Lécuyer and Richardin2020), lack of stratigraphic context (Morales et al. Reference Morales, Henríquez-Valido and Rodríguez2017), and the Gakushūin laboratory controversy (Blakeslee Reference Blakeslee1994). The two main contesting hypotheses, defined elsewhere as the Mediterraneanist vs. North Africanist (Cuello del Pozo Reference Cuello del Pozo2024), argue different timelines and cultural ascriptions for the first settlers of the Canaries. The Mediterraneanists postulate an initial settlement during the first millennium BC motivated by the Phoenician enterprise (Atoche-Peña and Ramírez-Rodríguez Reference Atoche-Peña and Ramírez-Rodríguez2017; del-Arco-Aguilar 2021). The North Africanist’s views encompass different perspectives with a mainstream arguing for a first settlement dating between the first and third century AD based on 14C dating of human and non-human animal bone collagen (Alberto-Barroso et al. Reference Alberto-Barroso, Delgado-Darias, Moreno-Benítez and Velasco-Vázquez2019; Sánchez et al. Reference Sánchez, Carballo, Padrón, Hernández, Melián, Navarro Mederos, Pérez and Arnay-de-la-Rosa2021; Velasco-Vázquez et al. Reference Velasco-Vázquez, Alberto-Barroso, Delgado-Darias and Moreno-Benítez2021). Researchers have recently applied a new Marine Reservoir Effect (MRE) correction to samples that had undergone chronometric hygiene assessments, reaffirming earlier postulations on colonization events (Santana et al. Reference Santana, Del Pino, Morales, Fregel, Hagenblad, Morquecho, Brito-Mayor, Henríquez, Jiménez and Serrano2024). The results from Santana and colleagues (Reference Santana, Del Pino, Morales, Fregel, Hagenblad, Morquecho, Brito-Mayor, Henríquez, Jiménez and Serrano2024) reinforce the idea of an early Roman presence in the Canary Islands (del-Arco-Aguilar et al. Reference del-Arco-Aguilar, del-Arco-Aguilar, Benito-Mateo and Rosario-Adrián2016) and support that other groups established more permanent settlements across the islands by the 3rd century AD (Velasco-Vázquez et al. Reference Velasco-Vázquez, Alberto-Barroso, Delgado-Darias and Moreno-Benítez2021). Paleogenetics has shown so far that ancient aboriginals of the Canary Islands were a heterogenous population with ancestral influence from not only North Africa but also Europe and that genetic diversity differentiated based on archipelagic regions (Rodríguez-Varela et al. Reference Rodríguez-Varela, Günther, Krzewińska, Storå, Gillingwater, MacCallum, Arsuaga, Dobney, Valdiosera and Jakobsson2017; Fregel et al. Reference Fregel, Ordóñez, Santana-Cabrera, Cabrera, Velasco-Vazquez, Alberto, Moreno, Delgado, Rodriguez and Hernandez2019; Serrano et al. Reference Serrano, Ordóñez, Santana, Sánchez-Cañadillas, Arnay, Rodríguez-Rodríguez, Morales, Velasco-Vázquez, Alberto-Barroso and Delgado-Darias2023). The earliest dated human remains is a tooth from Guayadeque in Gran Canaria Island, dating to 1720 ± 27 BP (Serrano et al. Reference Serrano, Ordóñez, Santana, Sánchez-Cañadillas, Arnay, Rodríguez-Rodríguez, Morales, Velasco-Vázquez, Alberto-Barroso and Delgado-Darias2023).

Lately, attempts have been made to categorize the validity of published radiocarbon chronologies by assessing their reliability using the case of Gran Canaria Island (Pardo-Gordó et al. Reference Pardo-Gordó, Vidal Matutano and Rodríguez Rodríguez2022). Authors classified 297 dates into seven categories and about 60% of the samples fell between the first and second ranges, considered the most reliable results. Of those, 47.13% were human tissue, including bone (Pardo-Gordó et al. Reference Pardo-Gordó, Vidal Matutano and Rodríguez Rodríguez2022). However, we have yet to ascertain the validity of dates from bone based on laboratory methods, calibration, and the proper reporting of parameters. Essential supplementary details concerning bone collagen laboratory processing methods should always accompany 14C results. Consideration must also be given to the marine reservoir effect (MRE) and its influence on 14C ages of ancient bones from islanders and coastal populations whose diet depended on marine resources. Thus, publications of radiocarbon dates should include stable isotope results (δ13C and δ15N ratios) from the collagen being dated. While these practices are now standard in archaeology for reporting 14C data from human bone, there is a noticeable lag in their implementation in the Canary Islands.

Reliable radiocarbon ages are predefined by the researcher’s close understanding of 14C measurements, the scrutinizing of site formation processes, sample identification, and the level of chemical purity of materials such as bone, ivory, teeth, antler, wood, and charcoal (Weiner Reference Weiner2010). Furthermore, to assess the accuracy of radiocarbon dates we must have an informed knowledge of laboratory sample pretreatment protocols (Devièse et al. Reference Devièse, Comeskey, McCullagh, Bronk Ramsey and Higham2018a). Currently, researchers are reassessing chronologies globally to better characterize the temporal span of major human migrations such as the peopling of the Americas (Becerra et al. Reference Becerra, Waters, Stafford, Anzick, Comeskey, Deviese and Higham2018; Waters et al. Reference Waters, Amorosi and Stafford2017) or anatomically modern human dispersals into eastern Asia (Li et al. Reference Li, Bae, Ramsey, Chen and Gao2018). These reexaminations re-date previously dated archaeological sites using the latest sample purification laboratory methods.

To properly choose the appropriate laboratory purification steps and provide reliable collagen 14C dates, researchers must make a clear distinction between contamination and degradation. Degradation refers to the breakage and loss of peptides in amino acid bonds resulting more commonly in arid areas (van Klinken Reference van Klinken1999). To diagnose collagen percent loss the simplest method is to compute the collagen yield, a cut-off point of 1% may be used to alert the suitability of the sample for analysis (van Klinken Reference van Klinken1999). Contamination or the interaction of the collagen molecule with exogenous substances such as humates (Stafford et al. Reference Stafford, Brendel and Duhamel1988; van Klinken Reference van Klinken1999) and preservatives from museum curation precludes the measuring of correct 14C signatures from endogenous collagen. Van Klinken (Reference van Klinken1999) suggests that evaluation of bone collagen quality is not a failsafe but it can be explored via 1) analyzing chemical indicators including amino acid composition, collagen yield, infra-red spectra, and chemical analyses (Ambrose Reference Ambrose1990); 2) obtaining elemental data with N and C content from extracted collagen such as the atomic C:N ratio (DeNiro Reference DeNiro1985; Schwarcz and Nahal Reference Schwarcz and Nahal2021); and/or 3) collecting δ13C and δ15N results as they provide a direct comparison with expected isotope ratios for the species from the study area (Schoeninger et al. Reference Schoeninger, DeNiro and Tauber1983).

To remove the effects of bone degradation and/or contamination researchers have developed a variety of chemical pretreatment protocols that purify the collagen molecule. The suitability of using bone to precisely date an archaeological site has popularized its use (Waters et al. Reference Waters, Stafford and Carlson2020) and the complexity of properly processing this material has prompted multiple methodologies to emerge, thereby increasing inter-laboratory accuracy errors (van Klinken Reference van Klinken1999). Standard procedures include the demineralization and acid/base/acid (ABA) treatments to remove bulk contaminants from processes such as diagenesis; yet these steps can leave molecular traces from the soil and/or degraded peptides (Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Higham, Bowles and Hedges2004). Also, gelatinization (Law and Hedges Reference Law and Hedges1989) and subsequent ultrafiltration (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Nelson, Vogel and Southon1988) will further concentrate and isolate the larger molecules of collagen more likely to belong to the endogenous collagen fraction. However, questions have arisen whether ultrafiltration is the problem or the solution (Fülöp et al. Reference Fülöp, Heinze, John and Rethemeyer2013; Hüls et al. Reference Hüls, Grootes and Nadeau2007, Reference Hüls, Grootes and Nadeau2009). Other purification methods include XAD resins (types 1, 2, and 4), specifically XAD-2, to promote the separation of protein hydrolysates from fulvic acids (humates) via reverse-phase chromatography (Stafford et al. Reference Stafford, Brendel and Duhamel1988). Also, preparative High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (prep-HPLC) is capable of isolating distinct amino acids such as hydroxyproline, the targeted amino acid for compound-specific radiocarbon dating (Devièse et al. Reference Devièse, Comeskey, McCullagh, Bronk Ramsey and Higham2018a; Reference Devièse, Stafford, Waters, Wathen, Comeskey, Becerra-Valdivia and Higham2018b; Gillespie et al. Reference Gillespie, Hedges and Wand1984). The choice of methodology appears to be laboratory-based and perhaps even influenced by geographical affiliation. For instance, XAD-2 purification, developed by Stafford et al. (Reference Stafford, Brendel and Duhamel1988) in North America, is rarely employed in European AMS facilities, where ultrafiltration—first standardized by the Oxford Radiocarbon Analysis Unit (ORAU)—is more common (Herrando-Pérez Reference Herrando-Pérez2021). In this communication, we focus on the process of ultrafiltration and researchers’ discussions on the advantages and disadvantages of using this method on archaeological bone.

The process of ultrafiltration came up as a modification of the Longin (Reference Longin1971) method. Brown and colleagues (Reference Brown, Nelson, Vogel and Southon1988) proposed applying a lower temperature during gelatinization to minimize the degradation of protein fragments, thereby preserving larger endogenous peptides. The idea was to separate the intact and heavier collagen molecules from smaller contaminants, as larger fragments are more likely to be derived from the original collagen structure. They identified 58°C at a pH of 3 is the optimal condition for denaturation, allowing effective gelatinization while minimizing the loss of larger collagen molecules. Following this process, the gelatinized product undergoes ultrafiltration to yield >30kDa collagen, which is considered more reliable for dating (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Nelson, Vogel and Southon1988). In 2000, the method was adopted routinely at ORAU and soon modified after realizing some known-age bone samples were older than expected. The ultrafilters have a highly soluble glycerol-coated surface with traces of carbon that can contaminate the sample under measurement and thus, this coating must be removed before its use in laboratory processing methods (Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Higham, Bowles and Hedges2004). The source of carbon can differ by a set of filters and may introduce either young or fossil carbon to the sample (Brock et al. Reference Brock, Bronk Ramsey and Higham2007; Hüls et al. Reference Hüls, Grootes and Nadeau2009). To effectively control for this source of contamination, Bronk Ramsey and colleagues (Reference Bronk Ramsey, Higham, Bowles and Hedges2004) have implemented an ultrasonicating step and three additional centrifuge rinses along with the two protocolary rinses suggested by the manufacturer.

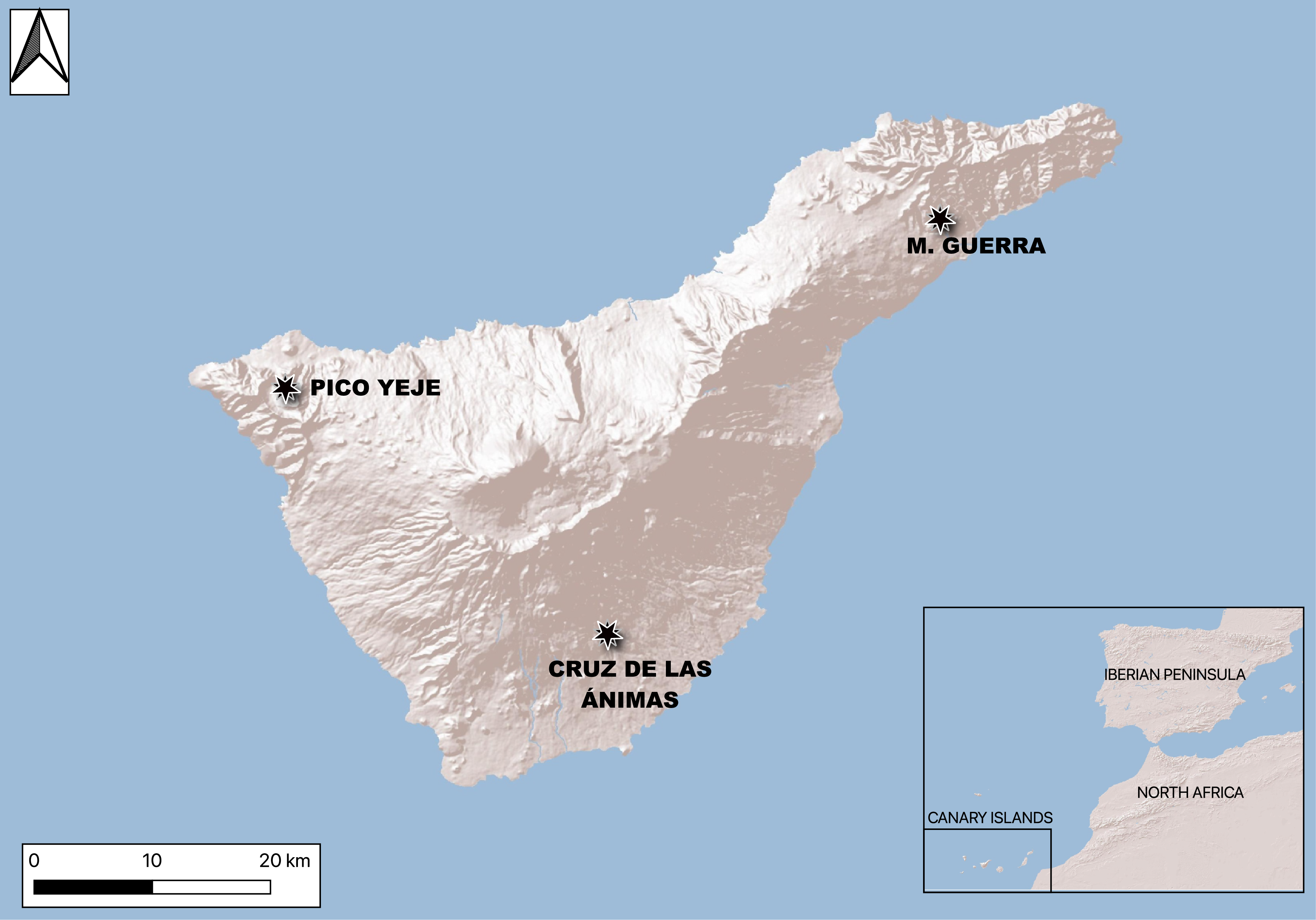

Since this is the first time ultrafiltration is being done on skeletal material from ancient natives of Tenerife Island (known as Guanches), we assess the effectiveness of the method on bone samples expected to date from around 1500 to 500 BP. Also, we introduce a new set of human 14C dates for Tenerife. Eight archaeological Guanche bones (Figure 1) were subsampled, ultrafiltered (>30kDa), radiocarbon-dated, and compared to non-ultrafiltered collagen from the same individuals. Ultrafiltration’s utility has been contested due to the significant increase in laboratory preparation time and costs, particularly for contexts that are less than 5730 BP, where this step might be unnecessary (Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Higham, Bowles and Hedges2004). Purification of relatively younger collagen via ultrafiltration could skew results towards older ages compared to basic cleaning methods. This outcome has been linked to insufficient cleaning of ultrafilters, which has subsequently skewed the results of known-age samples toward older ages (Bronk Ramsey et al. Reference Bronk Ramsey, Higham, Bowles and Hedges2004). Therefore, we kickstart a conversation on appropriate laboratory protocols for radiocarbon dating Canarian archaeological bone.

Figure 1 Location of the Canary Islands. Individuals analyzed in this study were recovered from settlements in Tenerife.

Materials and methods

Materials

Eight archaeological human bones were processed following simple acid/base/acid and gelatinization (AG) methods for radiocarbon dating, followed by ultrafiltration (UF) for additional dating of the same samples. The individuals came from specific sites of comingled nature from Tenerife Island and were originally stored at Museo de Naturaleza y Arqueología, Tenerife (MUNA). Four of the samples were from skeletal remains from Montaña de Guerra, three from Pico Yeje, and one from Cruz de las Ánimas. As assessed visually, the preservation of the bones appeared in good condition, with no significant signs of surface erosion, cracking, or flaking, exhibiting a dense and well-preserved matrix.

The site of Montaña de Guerra in the municipality of La Laguna is about 250 meters above sea level (masl) within a ravine. Individuals belonged to two funerary caves—the typical burial pattern on this island—and were associated with nearby habitational caves. The burials contained beads, an opal, woven vegetation fibers, and zooarchaeological remains from fish, ovicaprids, pigs, and dogs (Mederos et al. Reference Mederos, Escribano and Valencia2020).

The rock art station of Pico Yeje in Buenavista del Norte at ∼900 m a.s.l. has engraved motifs showing ellipsoidal and fish-like figures. Nearby an associated funerary cave was found and its entrance contains rock incised channels and bowls. Researchers have interpreted the site as a place of solar cult resembling other ritual sites in Gran Canaria (Tejera Gaspar Reference Tejera Gaspar1988), an astronomical station (Belmonte et al. Reference Belmonte, Springer Bunk and Perera Betancort1998), or a place where the cult of Phoenician solar-moon deities Ball Hammon-Tanit was exercised (del Arco Aguilar et al. Reference del Arco Aguilar, González-Antón, Candelaria, del Arco-Aguilar, González, Benito, Balbín-Behrmann and Bueno-Ramírez2009).

At the Cruz de las Ánimas ravine in El Rosario there is a rather large funerary cave at about 500 masl with associated habitational caves nearby. A total of 26 individuals were found along with items such as tubular and circular beads, bone awls, ceramic fragments, and floral remains including canary pine wood (Pinus canariensis), heather (Erica canariensis), and spurge (Euphorbia canariensis) (Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Tejera and Lorenzo1973; del Arco Aguilar Reference del Arco Aguilar1976).

Methods

The processing of bone was executed by one of us (PCdP) at the Radiocarbon and Isotope Preparation Laboratory at Texas A&M University following protocols published by Beaumont et al. (Reference Beaumont, Beverly, Southon and Taylor2010). The collagen was extracted using the modified Longin (Reference Longin1971) method (Brown et al. Reference Brown, Nelson, Vogel and Southon1988), for which full chunks of about 1 g was extracted. The surface of the bone was mechanically abraded, followed by sequential 30-min soaking in methanol, acetone, and dichloromethane solutions to remove possible adherents and lipids. Subsequently, the bone underwent two washes with Milli-QTM water (MQ-H2O) and was left to dry overnight. Surface-cleaned bone underwent demineralization by repeated soaking in 0.1M hydrochloric acid (HCl) at room temperature. To remove humates, an alkali wash was performed using 0.1M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) at room temperature for approximately 15–30 min until reaching a pH <6 in the solution. Although a subsequent HCl wash is commonly included to eliminate potential contamination from atmospheric CO2 absorbed during the base step, this was not performed here, as the protocol followed did not include it and the relatively recent age of the bones was not expected to be significantly affected. Pseudomorphs were gelatinized by soaking in 0.01M HCl on a hot plate at 59°C overnight. The solubilized gelatin was transferred to pre-weighed centrifuge tubes and lyophilized for two days. The freeze-dried gelatin of AG sample material was weighted to obtain collagen percent yield.

Approximately 15 mg of freeze-dried gelatin was subsampled into Sartorius Vivaspin® ultrafilters with polyethersulfone (PES) membranes and a molecular threshold of >30 kDa. To avoid potential contamination from glycerol, the filters were cleaned according to a protocol previously used at the Penn State AMS 14C laboratory (PSU AMS). This method intentionally omitted sonication, as there were concerns that it could damage the filter adhesive, which might introduce contamination during the sample purification process (pers. comm. B. Culleton 2024). Hence, ultrafilters were cleaned by leaving the lower part of the ultrafilter soaking overnight in MQ-H2O and filling the upper section with 0.01M of HCl. After discarding the liquids, the upper part was rinsed, refilled with MQ-H2O, centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min, and the MQ-H2O was discarded. These two steps were repeated three times. The upper part of the tubes was then left to soak in MQ-H2O overnight to assess the membrane leak rate. The ultrafilters were kept wet to avoid the drying out of the membrane.

The freeze-dried gelatin was rehydrated with MQ-H2O and transferred into centrifuge tubes then spun. Approximately 15 mL of gelatin solution was carefully pipetted into pre-cleaned ultrafilters using fine-tip pipets (Samco #233) to minimize the inclusion of particulates. The samples were then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 min. Following the initial filtration, the remaining liquid above the membrane was refilled with MQ-H2O and the samples were centrifuged again under the same conditions. This wash step was repeated twice to ensure removal of contaminants. By repeatedly centrifuging, any remaining solids get trapped as a solid pellet in the dead-stop pocket of the ultrafilter during the centrifugation process. The UF gelatin was carefully pipetted out avoiding solids and transferred to pre-weighted centrifuge tubes to then undergo a second round of lyophilization. Once dried, the material was weighted to determine collagen percent yield. For accelerator mass spectrometry analysis, approximately 1 to 2.5 mg of purified collagen was subsampled with approximately 60 mg of Copper (II) Oxide (CuO) and a silver (Ag) wire pellet to trap sulfur and chlorine compounds. These were packed into baked quartz tubes and sealed under vacuum to be then combusted in a muffle furnace for 3 hr at 900°C.

At PSU AMS, resulting CO2 samples were processed as in Davis et al. (Reference Davis, Culleton, Rosencrance and Jazwa2023) and are described as follows. The CO2 was cryogenically purified and transformed into graphite using the Bosch reaction with an iron powder catalyst with a C:Fe ratio of 1.4 and then baked at 550°C for 3 hr (Vogel et al. Reference Vogel, Southon, Nelson and Brown1984). Concurrently, any reaction water was removed using magnesium perchlorate [Mg(ClO4)2] desiccant (Santos et al. Reference Santos, Southon, Druffel-Rodriguez, Griffin and Mazon2004). Graphite samples were pressed into targets in aluminum (Al) boats and loaded on a target wheel for AMS analysis. Radiocarbon measurements were conducted using a modified NEC 500kV 1.5SDH-1 compact AMS at PSU AMS. Measured 14C ratios were normalized to Oxalic Acid II (OX-II) standards. Both F 14C values and conventional 14C ages were adjusted for fractionation effects during graphitization and measurement, utilizing δ13C values measured by the AMS. Corrections followed the conventions outlined by Stuiver and Polach (Reference Stuiver and Polach1977) and (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Baillie, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Bertrand, Blackwell, Buck, Burr and Cutler2004). To check for modern contamination, the Pleistocene Latton Mammoth background was used from Marine Isotope Stage 7 (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Maddy, Buckingham, Coope, Field, Keen, Pike, Roe, Scaife and Scott2006). The Holocene Certain Site bison kill #2 was used to control for dead carbon contamination with a known age of 1840 ± 20 BP (Bement and Buehler Reference Bement and Buehler1994). The backgrounds underwent the ultrafiltration step to ensure the proper execution of filter cleaning protocols.

Stable Isotope Values

To obtain stable isotope results, about 2.5 mg of AG dried gelatin was sent to the Stable Isotope Geoscience Facility (SIGF) at Texas A&M University, where samples were combusted into N2 and CO2 gasses to be measured in a Thermo Scientific DeltaplusXP isotope ratio mass spectrometer with Carlo Erba NA 1500 Elemental Analyzer. SIGF reports ± 1σ instrumental uncertainty of ± 0.2‰ for both δ15N and δ13C for normal-sized (700 mV to 20000 mV m28 and m44 measurement sample intensity) samples. Data was anchored to the Air (δ15N) and VPDB (δ13C) isotope scales via two-point calibration with USGS 40 and USGS 41a.

Statistical Applications

To evaluate the consistency of results between laboratory procedures we compare AG and UF radiocarbon ages using a contemporaneity test presented originally by Ward and Wilson (Reference Ward and Wilson1978), in which authors assessed the similarity of radiocarbon dates from different stratigraphic layers within a site. When comparing results obtained from the same samples that have undergone different laboratory processes, we are evaluating whether the 14C age determinations obtained from different samples are consistent with each other or if there are significant differences. Hence, we calculated a test statistic, T, which follows a chi-square distribution under the null hypothesis (H0) that compared ages are statistically equal. We then calculated the exact binomial test to compare the observed distribution of events with the theoretical distribution. The software used was R (version 4.3.1) and specifically the biom.test function available in the base package.

Results and discussion

All individual samples fall within the acceptable range ensuring the reliability of subsequent dating (van Klinken Reference van Klinken1999). The theoretical atomic C:N value at 3.243, established by Schwarcz and Nahal (Reference Schwarcz and Nahal2021), is in the middle of the generally adopted range of 2.9–3.6 (DeNiro Reference DeNiro1985). The average C/N ratio in our sample’s set is 3.26 and closely mirrors this theoretical value with individual samples falling within the established range of 2.9 to 3.5 (Table 1). The stable isotope values of δ13C and δ15N are consistent with those typically reported for ancient Guanches, with δ13C ranging from approximately –20.5‰ to –17.1‰ and δ15N ranging from 8.6‰ and 13.9‰ (Arnay-de-la-Rosa et al. Reference Arnay-de-la-Rosa, González-Reimers, Yanes, Velasco-Vázquez, Romanek and Noakes2010, Reference Arnay-de-la-Rosa, González-Reimers, Yanes, Romanek, Noakes and Galindo2011; Tieszen et al. Reference Tieszen, Matzner and Busemna1995).

Table 1. A comparison of uncalibrated radiocarbon dates from human bone collagen that underwent acid/base/acid gelatinization (AG) compared to dates from ultrafiltered >30kDa gelatin (UF) for the following archaeological cemeteries in Tenerife Island: Montaña de Guerra (BS-G-#), Pico Yeje (PYR#), and Cruz de las Ánimas (16/#)

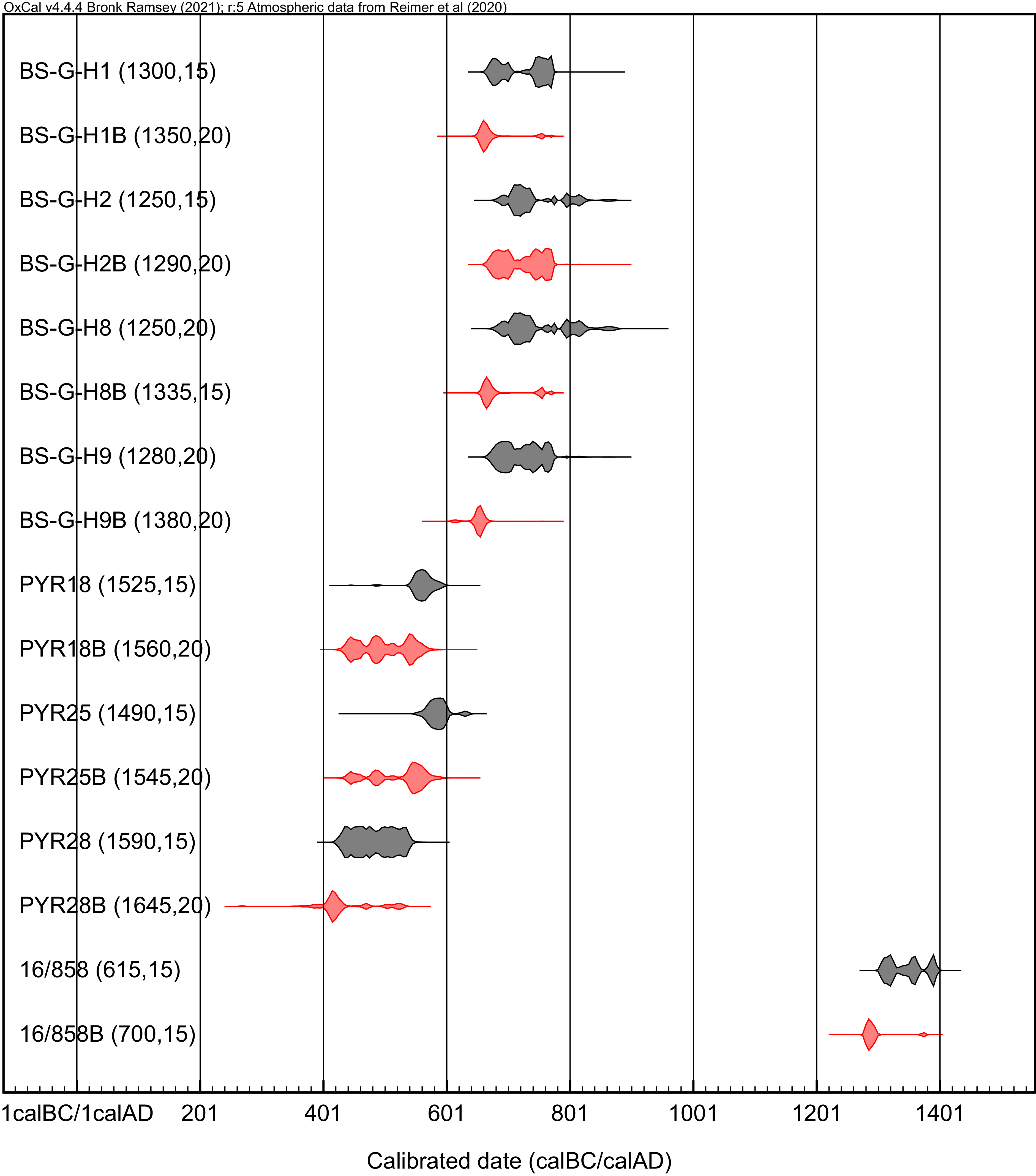

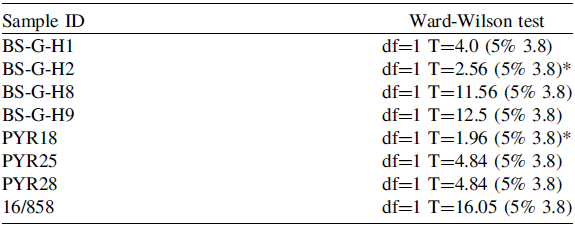

With a first observation of individual radiocarbon ages (Table 1), we observe that all the dates to which UF has been applied show older values than AG samples (the difference is <100 years between procedures; Figure 2). However, the first issue to be analyzed is whether these differences, between pairs of samples, are statistically equal. For this purpose, the chi-square test has been carried out to compare the radiocarbon results from ultrafiltered and non-ultrapure samples (Table 2) using the OxCal calibration software function R_Combine (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2021).

Figure 2 Summary of results obtained following different methods. Samples identified with B and red color refer to radiocarbon dates ultrafiltrated.

Table 2. Results of the Ward-Wilson test (Ward and Wilson Reference Ward and Wilson1978). Sample ID corresponds to the site identification: Montaña de Guerra (BS-G-#), Pico Yeje (PYR#), and Cruz de las Ánimas (16/#). *Indicates which radiocarbon dates are strictly contemporaneous.

The results show a significant difference between the samples analyzed, indicating that the ultrafiltered samples are statistically older than the non-ultrafiltered ones (Table 2). Additionally, the Ward-Wilson test results support the existence of a bias, indicating non-contemporaneity between the radiocarbon sample pairs (p = 0.96).

Based on the results, we wonder which sample cleaning is more optimal. Researchers have pointed towards certain disadvantages to the ultrafiltration method such as collagen yield decrease, uncertain glycerin contamination from tubes’ membranes, and overall increased risk of introducing contaminants by adding extra steps (Fülöp et al. Reference Fülöp, Heinze, John and Rethemeyer2013). In our study, the average decrease in collagen yield from bone starting weight to ultrafiltration is approximately 95%, showing a significant loss of sample material after the gelatin has been purified. After UF, the Latton Mammoth (sample ID 11645) and the bison from Certain Site #2 (11646) yielded expected dates of 11645: 44140 BP ± 230 and 11646: 1875 BP ± 20. This shows that UF cleaning protocols were properly executed and suggests that UF collagen 14C results are plausibly more accurate. The choice of performing ultrafiltration or not is aleatory with multiple studies providing different results (Minami et al. Reference Minami, Yamazaki, Omori and Nakamura2013). Hüls et al. (Reference Hüls, Grootes and Nadeau2007) cautioned that despite efforts to clean filters, their study revealed contamination in the <30kDa fraction, while the >30kDa fraction remained largely clean. In a later experiment, also Hüls et al. (Reference Hüls, Grootes and Nadeau2009) compared two differently manufactured ultrafilters and the effectiveness of cleaning procedures to successfully remove the glycerin coating. Further inspection via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) confirmed the still presence of a layer indicating manufacturer remnants. In another study comparing the effects of executing ultrafiltration versus solely ABA treatment, Fülöp and colleagues (Reference Fülöp, Heinze, John and Rethemeyer2013) found that purification failed to yield discernibly distinct ages compared to samples treated with ABA alone. Similarly, Minami and colleagues (Reference Minami, Yamazaki, Omori and Nakamura2013) concluded that for well-preserved samples, unfiltered gelatin yielded 14C ages and isotopic values consistent with filtered gelatin and consensus values. Thus, suggesting non-UF gelatin may produce sufficiently reliable dates. The ongoing debate “whether ultrafiltration is a boon or bane for the reliable dating of bones” (Hüls et al. Reference Hüls, Grootes and Nadeau2009:624) remains a topic of contention in archaeology.

For this paper, we explored chronometric discrepancies upon the application of different collagen pretreatment methods to the same sample. Based on our findings and the observations made in the works mentioned above, we propose that ultrafiltration may be advisable in the context of the Canary Islands. However, at this stage, we lack sufficient complementary data to conclusively determine its necessity. Several questions should be considered, some of which are outlined here. First, does the variation in radiocarbon results significantly alter the current historical understanding of the Canary Islands? In this study, we observed that UF dates fluctuate by less than 100 years compared to non-UF radiocarbon samples. Second, is the risk of added contamination worth it? Ultrafiltration requires extra effort and resources, increasing the risk of material loss or potential contamination due to additional handling. Third, do the samples originate from regions affected by geologically recent eruptive activity? In volcanic contexts, samples collected near volcanic cones associated with past eruptions have been shown to exhibit 14C alterations, often yielding older-than-expected dates (Holdaway et al. Reference Holdaway, Duffy and Kennedy2018). If a bone sample was buried in an area with volcanic activity, UF could potentially help eliminate contamination from old carbon traces. However, in this study, the bone samples analyzed do not come from eruptive cones within the Pico Viejo-Teide complex and are therefore unlikely to be affected by such contamination. It is important to note that our case study is based on samples from the midland regions (medianías) of Tenerife. Future comparisons with samples from other contexts such as coastal and highland settlements as well as from more arid islands like Fuerteventura and Lanzarote will be essential to evaluate the broader applicability of these results. Expanding this research across different biogeographical zones will help refine our understanding of ultrafiltration’s impact on radiocarbon dating in the Canary Islands.

Conclusions

Given that ultrafiltration filters require rigorous cleaning to avoid contamination, laboratories specializing in bone preparation for radiocarbon dating must adopt protocols that rigorously evaluate the effectiveness of membrane cleaning procedures through routine assessments of aliquots from ultrafiltration tubes. Implementing such protocols is crucial to uphold the accuracy and reliability of radiocarbon dating results.

In the current literature, there is no established consensus on the universal recipe to pretreat bone remains for 14C analysis, simply because not every buried bone undergoes equal taphonomic processes. Our findings suggest that ultrafiltration on ancient Canary aboriginal bone is removing contaminants. Thus, UF-dated samples are likely more accurate; however, given the potential risks of contamination and sample loss associated with further purification, this process may not always be essential in our region of interest, particularly for well-preserved material. We suggest that ultrafiltration would be most beneficial for samples belonging to the earliest settlements and possibly for those materials buried in regions affected by volcanic activity. Also, we recognize that future work should consider including the second HCl wash after the alkali step, particularly to ensure removal of any potential carbonate contamination in more sensitive or older samples. Essentially, further validation is necessary through additional dating of contexts with independent chronological markers, such as imported ceramic production sequences, historical records and notarial documents. Cross-referencing radiocarbon results with colonial-era contexts and alternative dating sources will be critical in assessing the reliability of ultrafiltration in this region. The definition of the most appropriate protocol for the pretreatment of the sample will make it possible in the future to obtain more accurate, feasible, and viable chronologies for different historical-archaeological processes, including the indigenous and colonial settlement of the Canary Islands.

Acknowledgments

The analysis of these radiocarbon dates was made possible through funding from the National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant in Archaeology (Proposal #2132396). We gratefully acknowledge the support of Dr. Heather Thakar, Director of the Radiocarbon and Isotope Preparation Laboratory at the Department of Anthropology, Texas A&M University. Also, much appreciation goes to Dr. Brendan Culleton for his invaluable training and mentoring. Additionally, we thank Dr. Maggie Davis for providing her knowledge throughout the methods and John Southon for his insightful comments throughout the review process. SPG is a beneficiary of Ramón y Cajal program (RYC2021-033700-I) funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13013/501100011033 and by the European Union Next Generation EU/PRTR and he acknowledges the funding from the Universidad de La Laguna and the Spanish Ministry of Universities. Finally, we are also thankful for the revisions provided by anonymous reviewers as their suggestions have strengthened the quality of this publication.