Introduction

In 1981, Cajsa Lund, then working as an assistant at the Stockholm Music Museum’s National Inventory, proposed a typology for sound-producing archaeological objects. The classification ranged from objects recognisably designed to produce sound to those that likely served that purpose and items with a dual function that included sound production, such as a necklace of shells. These latter categories included objects where sound was incidental and others of unknown function that had the potential to produce sound (Lund Reference Lund1981). This typology clearly established that there was a whole world of sonorous objects that went beyond musical instruments. This article focuses on one such object: the shell trumpet (also known as seashell horn, triton trumpet and conch-shell). Made from the seashell of a gastropod with its apex removed, the trumpet can be used as a cone-shaped aerophone by lip-vibration. Accounts of shell trumpets used in signalling, ritual, military and musical contexts are found worldwide (e.g. Montagu Reference Montagu1981: 273) but the geographical distribution is influenced by the natural habitats of the gastropods, which thrive in warm waters (Schultz et al. Reference Schultz, Wessely, Dullinger and Albano2024).

In Europe, shell trumpets are known since the Magdalenian period (15 000–10 000 BC) (Fritz et al. Reference Fritz2021), but the number of finds increases substantially in the Neolithic (6000–2800 BC) in areas as far north as Germany and Hungary, highlighting their role in Neolithic exchange networks (Skeates Reference Skeates1991: 20; Montagu Reference Montagu2018: 40). Yet, finds are more frequent close to the Mediterranean, on its eastern shores (Aström & Reese Reference Aström and Reese1990; Reese Reference Reese1990) and in Italy (Skeates Reference Skeates1991: 25; Cortese et al. Reference Cortese, del Lucchese and Garibaldi2004; Di Nocera & Marano Reference Di Nocera, Marano, DeAngeli, Both, Hagel, Holmes, Jiménez Pasalodos and Lund2018: 44), France (Clodoré & Leclerc Reference Clodoré and Leclerc2002: 52) and Spain (Sáez & Gutiérrez Reference Sáez, Gutiérrez, Jiménez Pasalodos, Till and Howell2013; Jiménez Pasalodos Reference Jiménez Pasalodos2019). Twelve shell trumpets were found across a relatively small area in the north-east of the Iberian Peninsula, in present-day Catalonia. This article examines the contexts of these 12 shell trumpets and discusses their possible functionality, either for signalling or musical expression. To do so, their acoustic properties are analysed, focusing on sound pressure level, harmonic series, pitch and the possible role of the holes found in some of them.

Archaeological context of the shell trumpets found in Catalonia

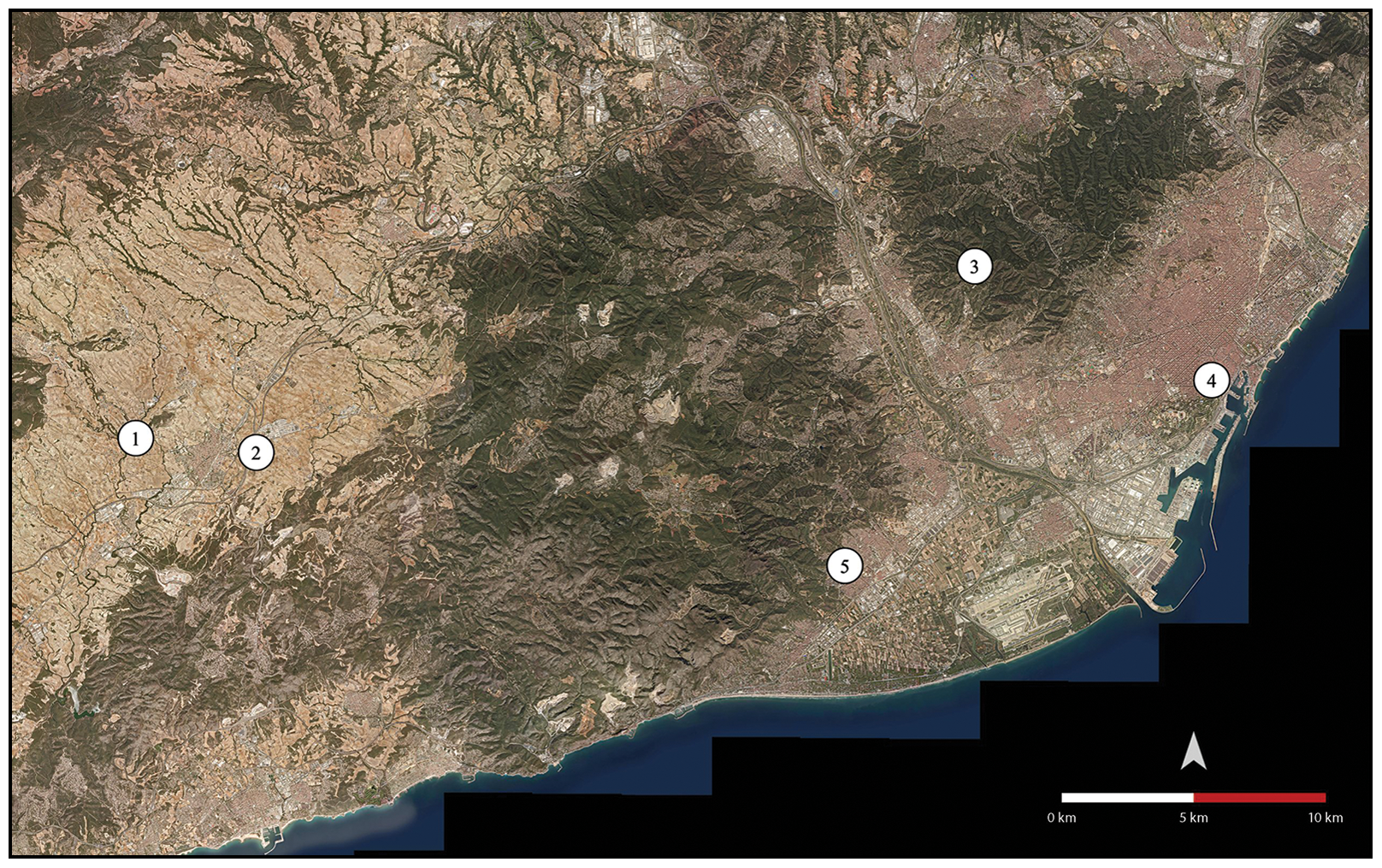

All 12 shell trumpets are associated with Neolithic contexts and are from the most commonly found gastropod from the genus Charonia in the Mediterranean, Charonia lampas (pink lady) (Borg Reference Borg2013: 186). Now on the verge of extinction, the natural habitat of this species lies below 5m in the Mediterranean (Di Nocera & Marano Reference Di Nocera, Marano, DeAngeli, Both, Hagel, Holmes, Jiménez Pasalodos and Lund2018: 44; Sáez, Reference Sáez, Gutiérrez, DeAngeli, Both, Hagel, Holmes, Jiménez Pasalodos and Lund2018: 72). Intentional removal of the apex of each shell suggests that all were used to produce sound. Most display biological marks (such as vermiculations from polychaetes, annelid traces, sponge holes and carnivorous molluscs) on the exterior and, to a lesser extent, on the interior surface. This suggests that the specimens were likely collected postmortem (Bosch et al. Reference Bosch, Estrada and Juan-Muns1999: 181), not for consumption, but rather with the intention of using them as sound-producing instruments. The find locations are concentrated in the lower course of the Llobregat River and the pre-coastal depression of the Penedès region (Figure 1). This river facilitated intense exchange among the inhabitants of these areas and even with more northern regions. Such interactions likely account for the notable cultural uniformity observed in the Penedès during the Neolithic (Granados Reference Granados1981: 146; Oms et al. Reference Oms, Esteve, Mestres, Martín and Martins2014: 43; Edo et al. Reference Edo, Gómez, Mestres, Martínez, Molist and Oms2022).

Figure 1. Map showing the sites where Neolithic shell trumpets have been found in Catalonia: 1) Mas d’en Boixos; 2) Cal Pere Pastor; 3) Cova de l’Or; 4) Espalter 1; 5) Mines de Can Tintorer (figure by authors).

Identified as ‘horns’ in the literature (see below), the 12 Neolithic shell trumpets date to a span of 1500 years, with a concentration between the late fifth and early fourth millennia BC. Five are associated with Postcardial Neolithic (4690–3800 BC) contexts, the last phase of the Early Neolithic (Morell-Rovira et al. Reference Morell-Rovira2023), found at Mas d’en Boixos (n = 3), Cal Pere Pastor (1) and Cova de l’Or (1) (although the latter specimen lacks stratigraphic context, so its cultural attribution here remains tentative). The remaining specimens, one discovered at Espalter and six in the mines of Can Tintorer, were found in contexts associated with the Pit Grave Culture (‘Sepulcres de Fosa’) of the Middle Neolithic (4250–3150 BC) (Morell-Rovira et al. Reference Morell-Rovira2023). These 12 shell trumpets are the earliest known in Catalonia. Following the Neolithic, shell trumpets do not reappear until the Iron Age, three millennia later (Matamoros et al. Reference Matamoros, Ruiz, Garcia and Moreno2011).

Mas d’en Boixos is an open-air pit settlement situated on a slight elevation in the heart of the Penedès pre-coastal depression. During the Postcardial Neolithic phase at this site around 100 pits were dug out and variously filled with earth, stones and the remains from domestic activities, which accumulated naturally and through indiscriminate dumping when the site was in use. Individual and collective burial pits were also identified, a practice that became more prominent during the Middle Neolithic (Farré et al. Reference Farré, Mestres, Senabre and Feliu2002: 115–21; Vidal Reference Vidal2005; Pedro Reference Pedro2012: 24–25; Bouso et al. Reference Bouso, Gibaja, Mozota Holgueras, Subirà, Martín Cólliga, Roig Buxó and Masclans2019). Two shell trumpets (one of which, 332-1-3, is nearly complete) were found in waste pits (Vidal Reference Vidal2005; Pedro Reference Pedro2012: 24–25), while a third, better-preserved shell trumpet (355-1-55) was found in structure 355, a pit containing the remains of five closely contemporaneous primary inhumations, predominantly of male adults (Vidal Reference Vidal2005; Oliva Reference Oliva2015: 430).

The shell trumpet from Cal Pere Pastor was discovered in 2010 during salvage excavations at the Eix Diagonal (C-15, C-57) road intersection. A total of 21 negative structures—pits, basins, deposits and burials—dating to different periods were excavated, most belonging to the Postcardial and Middle Neolithic (Segura et al. Reference Segura, Esqué, Medina and Espejo2010: 103). Charonia shells fragments were recovered from pits 14, 17, 19 and 20, all dated to the Postcardial Neolithic. The only complete example was unearthed in pit 17, alongside faunal remains and ceramics. The site report identifies it as a musical instrument due to the removal of its apex (Segura et al. Reference Segura, Esqué, Medina and Espejo2010: 107).

Cova de l’Or is a cave on the western slope of the Santa Creu d’Olorda massif, within the Collserola mountain range. The site has a chronological sequence spanning from the Early Neolithic to the Late Bronze Age (c. 1250–750 BC). Although the lack of distinct stratigraphy prevents a precise chronocultural attribution, ceramic typology indicates a predominance of sherds from the Epicardial to Middle Neolithic transition (c. 4700–3500 BC) (Granados Reference Granados1981: 155). One well-preserved shell trumpet was found at the site. Although its exact chronology is uncertain, its association with other materials suggests that it likely belongs to the Postcardial Neolithic. Fragments of human skull were also found at the site, although both their chronology and any possible relationship with other artefacts remain unclear (Granados Reference Granados1981: 155; Montaner Reference Montaner2013: 40).

Excavations at Espalter 1 unearthed a broad stratigraphic sequence from the Neolithic to the contemporary period. The earliest phase identified at the site dates from the period between the Postcardial and the Middle Neolithic. One shell trumpet was recovered from the fill of a 1.2m-deep, elliptical-shaped pit (4.3 × 2.1m), probably initially used as a storage pit but later repurposed as a refuse pit. Associated materials included numerous worked lithic artefacts made of flint and jasper, and abundant ash and charcoal (Nadal & Castillo Reference Nadal and Castillo2010: 9).

The final six conch shells were recovered from the Neolithic mines of Can Tintorer, Gavà, an archaeological site near the Mediterranean Sea, on the right bank of the mouth of the Llobregat River. While older mining complexes are known, these mines stand out as one of the most remarkable examples of prehistoric mining in the Western Mediterranean (Camprubí et al. Reference Camprubí2003). With a chronological range between 4050 and 3650 BC (Morell-Rovira et al. Reference Morell-Rovira2023: 12), the Can Tintorer mines were exploited for the extraction of variscite, a mineral used in the manufacture of personal ornaments that played a key role in the exchange networks of the time (Borrell & Bosch Reference Borrell and Bosch2012). Tunnels deemed unsuitable for further use were reused for burial purposes or refilled with waste from newly excavated tunnels, a practice that resulted in the exceptional preservation of a diverse and abundant collection of archaeological material (Morell-Rovira et al. Reference Morell-Rovira2023: 13). Of the six conch shells recovered from the Gavà mines, one was found in each of mines 2, 5 and 6, another from the collapsed space between mines 5 and 11, and two more from mine 16. All were found in mine fills of abandoned galleries. Radiocarbon dating associated with the shells indicates a chronology between 4000 and 3800 BC, coinciding with the peak of mining activity at the site in the Middle Neolithic (Borrell et al. Reference Borrell, Bosch and Majó2015: 75; Morell-Rovira et al. Reference Morell-Rovira2023: 13).

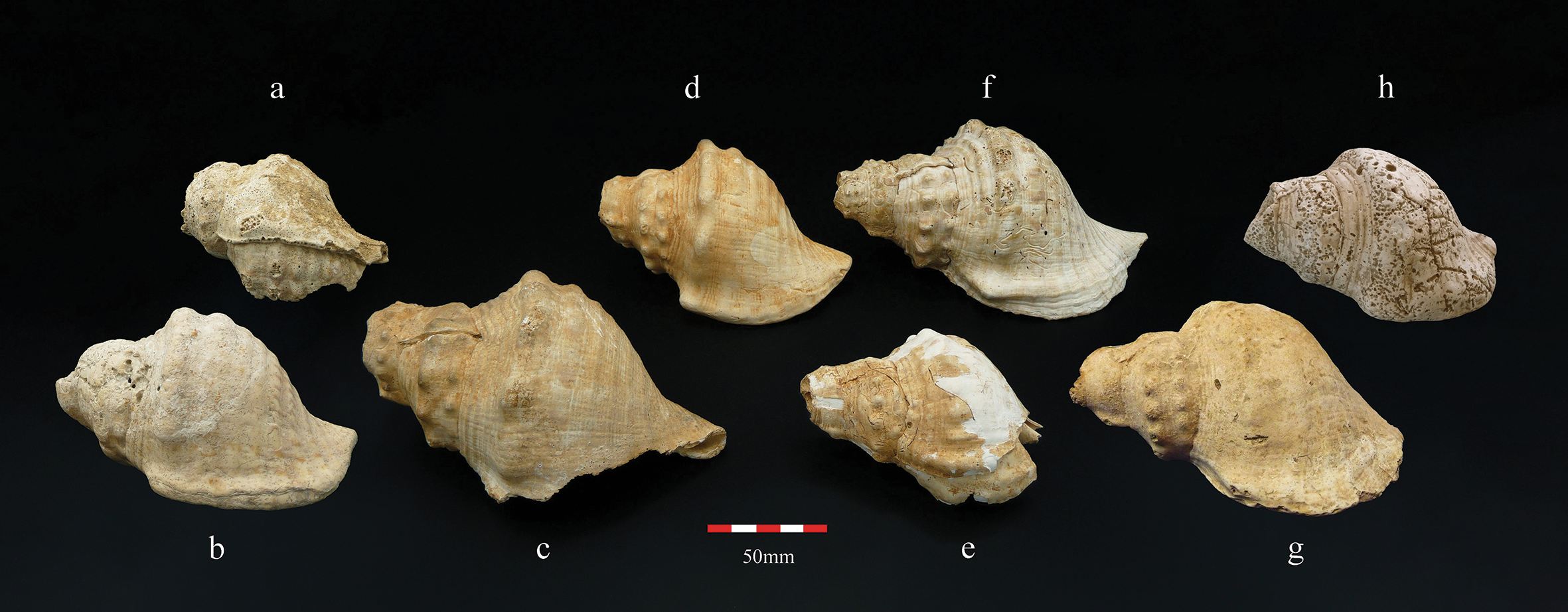

Of the 12 shell trumpets, only eight still have the capacity to emit sound (Figure 2); the remaining four have fractures that prevent their use as aerophones. Although the majority have been described as sound instruments, none have previously been studied in detail or acoustically tested.

Figure 2. Photographs of Neolithic shell trumpets from Catalonia that still produce sound today: Mas d’en Boixos 332-1-3 (a) and 355-1-51 (b); Mines de Can Tintorer 384-62 (c), 4003-1 (d), 5-212 (e) and 408-24 (f); Cova de l’Or CO221.9 (g); Cal Pere Pastor E17-UE3038 (h) (figure by authors).

Methods

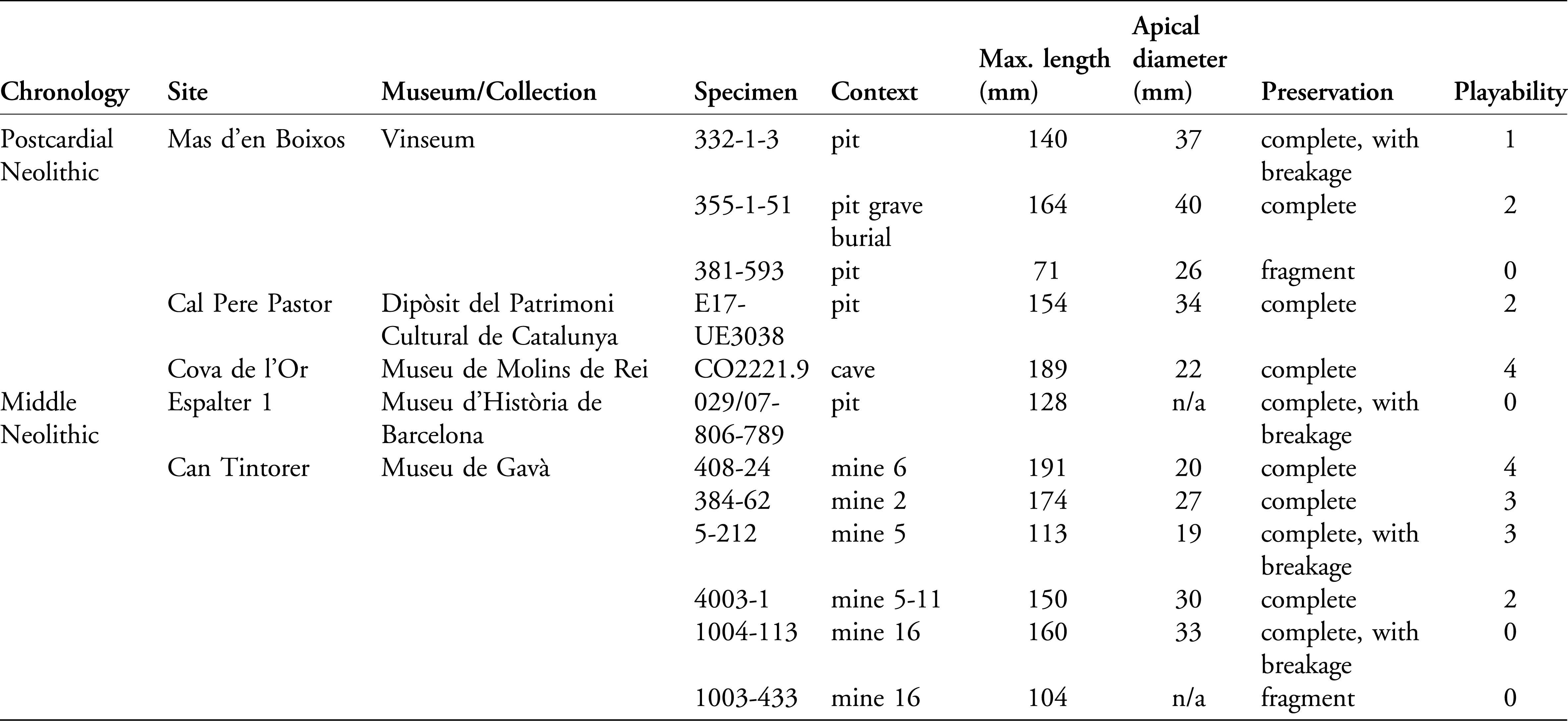

After compiling available data on the Neolithic shell trumpets discovered in Catalonia (Table 1), our study focused on characterising the sound qualities of each artefact. Our method followed previous studies, based on specimens found in other parts of the world (Cook et al. Reference Cook2010; Herrera et al. Reference Herrera, Espitia, García, Morris, Stöckli and Howell2014; Fritz et al. Reference Fritz2021). We had the extraordinary opportunity to carefully play the original instruments under the strict supervision of museum curators. All acoustic tests followed established conservation protocols, with appropriate precautions to avoid any damage to the shells.

Table 1. Summary of basic data on the Neolithic shell trumpets found in Catalonia.

For an explanation of ‘playability’, see Methods.

Two types of sound analyses—qualitative and quantitative—were conducted. The first involved free improvisations to explore each instrument’s sound resources, possible interpretative techniques—including different embouchure adjustments and pitch changing techniques—and the performer’s impressions of their qualities and playability. For this latter parameter, a rating scale from 0 to 4 was established to index the results (inspired by Cook et al. Reference Cook2010): 0) impossible to produce sound; 1) irregular sound, the instrument barely resonates or the emission is constantly interrupted; 2) one stable note, but requiring effort; 3) one regular and stable note, produced with relative ease; 4) two or more regular and stable notes, produced with relative ease. For results of this test, see the last column of Table 1.

For the quantitative analysis, only the eight playable shell trumpets—those with a playability index between 1 and 4—were selected (Tables 1 & 2). The quantitative acoustic tests were conducted in a controlled environment—spaces with low reverberation and minimal sound reflection effects, such as floating echoes. The instruments were played by one of the authors, archaeologist, musicologist and professional trumpet player Miquel López-Garcia, whose expertise allowed for consistent embouchure and technique application (refer to online supplementary material (OSM)). For the recordings, a CESVA SC202 Class 2 sound-level meter and a Zoom H4n portable recorder were used.

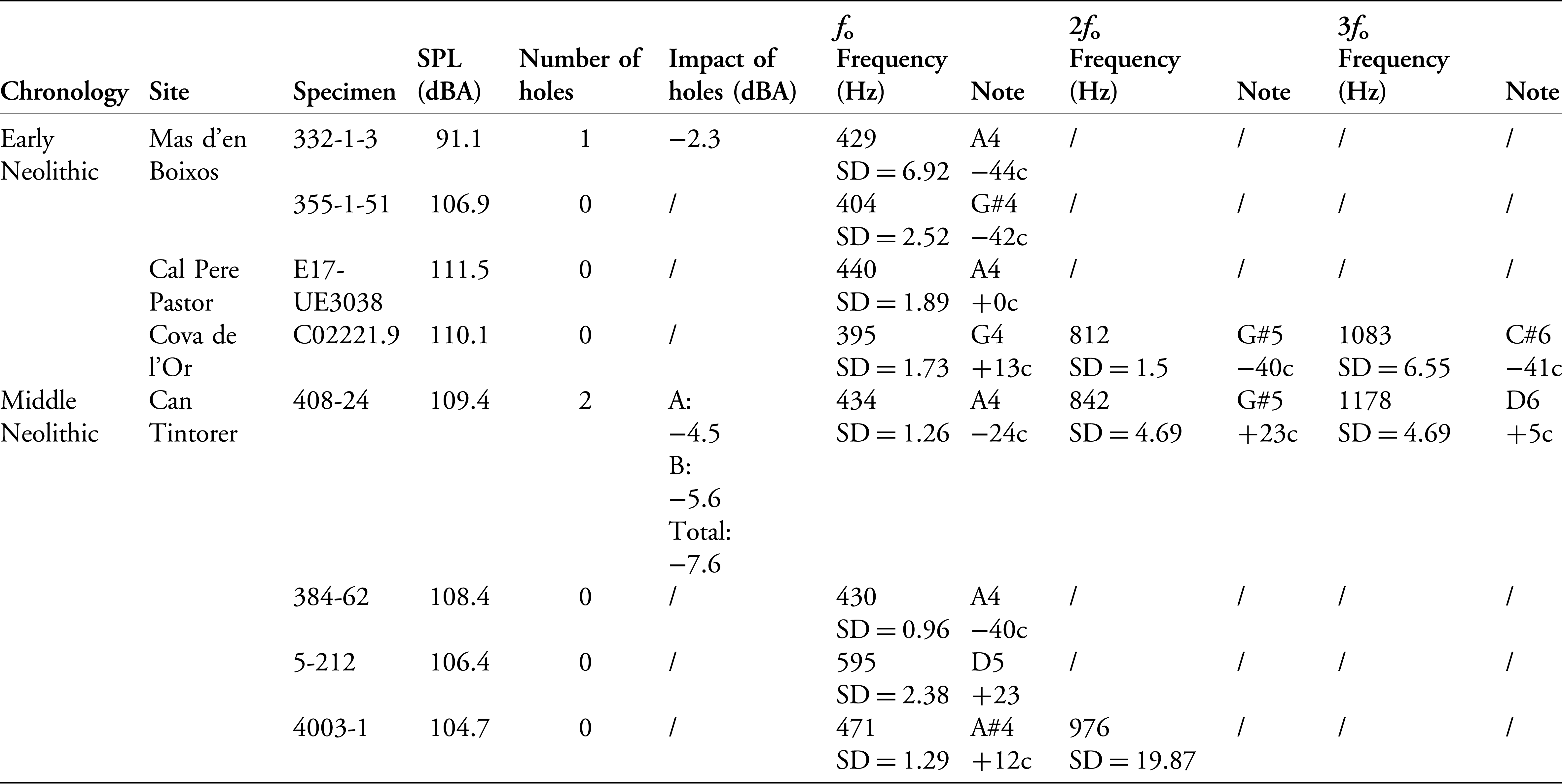

Table 2. Results of the sound analysis of the shell trumpets.

The sound pressure level (SPL) is measured in A-weighted decibels (dBA); SD: standard deviation; f o: fundamental frequency.

In the quantitative test, both recorders were positioned one metre from the sound source. Before and after each session, the sound-level meter was calibrated using a REED SC-05 calibrator. The sound-level meter measured the sound pressure levels (SPL) in A-weighted decibels (dBA), which apply a frequency weighting to approximate the sensitivity of human hearing—emphasising mid-range frequencies and attenuating very low and very high ones—for each note produced. To ensure data reliability, all measurements were conducted with background-noise levels below 40dBA, and each note was played three times using lip vibration, aiming to achieve the instrument’s maximum reverberation capacity. The performer determined when the state of maximum reverberation and tonal stability was reached based on haptic and auditory perception, a criterion validated in previous studies (Cook et al. Reference Cook2010: 4). If this state was not achieved, the recording was repeated.

After recording, sound-level meter data were extracted in database format and analysed, while the recorder’s audio files permitted the study of the instruments’ pitch and harmonic series. Spectral analyses were conducted using the free software Sonic Visualiser with the libxtract Vamp plugins. By selectively sampling 50-millisecond audio fragments, we also calculated the standard pitch variation. This sampling was performed only in the central part of each note, after stabilisation following the attack (the initial phase of the sound, where it rises from silence to its peak amplitude) and before the decay. We also assessed the impact of the holes found in some conch shells by playing the instrument with and without the holes covered. Using these data, we evaluate the adequacy of the shell trumpets’ acoustic behaviour for signalling and musical expression.

Testing shell trumpets for signalling

Were the shell trumpets of Neolithic Catalonia capable of producing a high sound intensity that could have made them effective as signalling devices over long distances? We address this question by looking at sound pressure levels and assessing the impact of holes in shell trumpets on sound efficacy.

Sound pressure level

Seven of the eight playable shell trumpets reach sound levels that peak above 100dBA at 1m from the source, reaching up to 111.5dBA in the loudest case (Table 2). The exception is specimen 332-1-3 from Mas d’en Boixos that reaches just 91.1dBA. The reason for this suboptimal performance is the large, sharp and irregular apical opening (36mm), which, although it allows sound to be produced, prevents proper lip positioning.

Assessing the impact of holes on sound efficacy

Two of the eight shells have distinctive holes. These holes, in the last turn of the conch shell, have been variously argued to be natural in origin (Bosch et al. Reference Bosch, Estrada and Juan-Muns1999: 80) or deliberate perforations for the purpose of suspension, presumably from a rope or belt (Oliva Reference Oliva2015: 220–21). During our acoustic tests, we evaluated whether the perforations affected the sound level and, if so, whether the holes could function as tone holes.

The results displayed in Table 2 show that the holes lead to a loss of loudness and sound quality. However, their impact is not uniform, varying by location. In general, the closer the hole is to the main aperture or mouth of the shell trumpet, the less acoustic disturbance is produced.

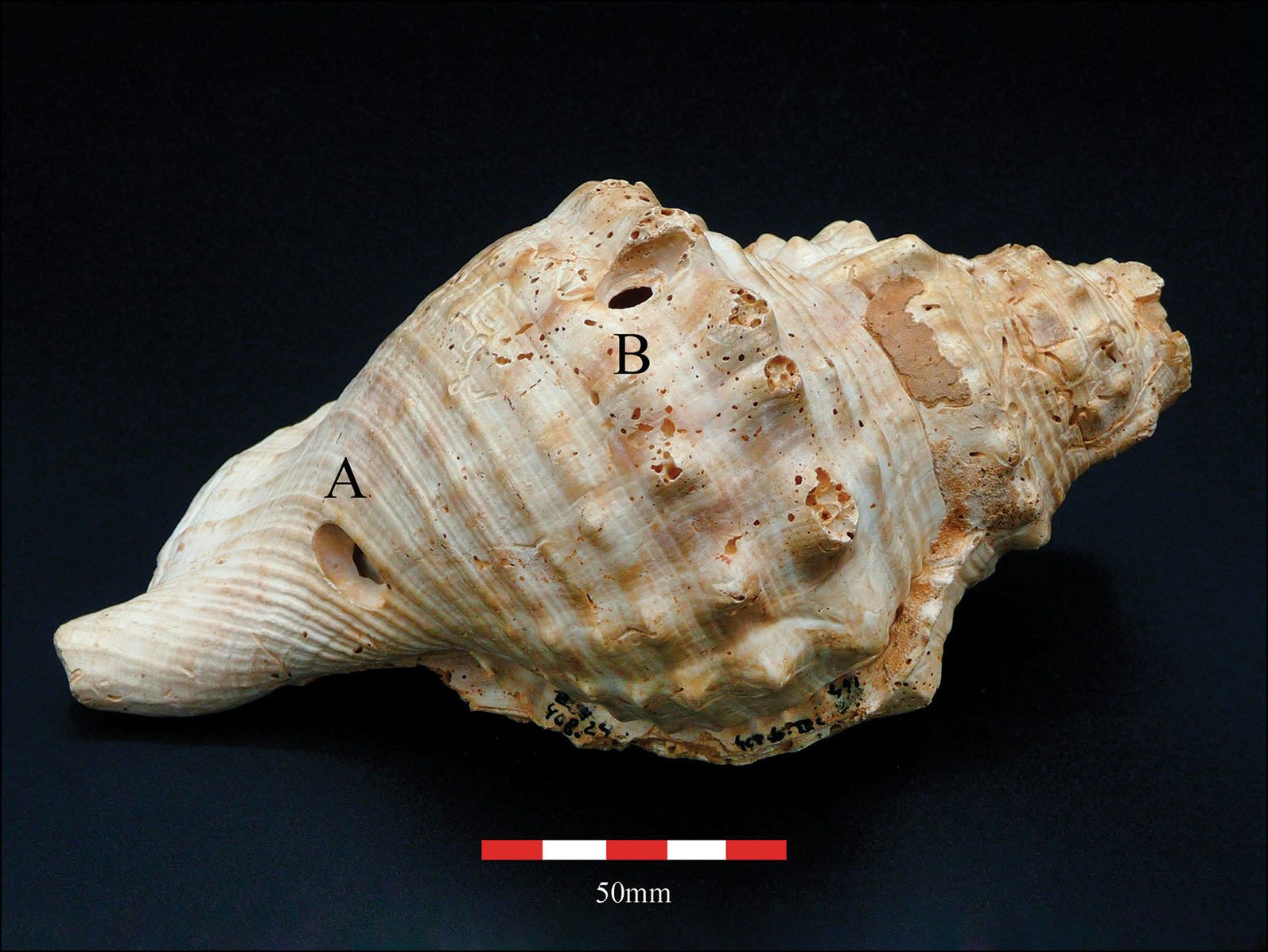

Artefact 408-24 from Gavà has two holes; the distal hole (A) reduced the sound pressure by 4.5dBA and the central hole (B) by 5.6dBA, with a cumulative loss of 7.6dBA (Figure 3). This substantial loss of sound quality strongly suggests that the holes were not made intentionally, thereby reinforcing the hypothesis that these holes have a natural origin (Bosch et al. Reference Bosch, Estrada and Juan-Muns1999: 80). The intensity of sound in the other Neolithic shell trumpet with a hole, 332-1-3 from Mas d’en Boixos, is hardly affected by the opening of the hole. This may result from the extreme difficulty and irregularity of sound emission in this instrument and the positioning of the perforation at one end of the third turn, with minimal interference in the canal. From an acoustic perspective, this location aligns with a strategy of minimal sound disturbance, which, in turn, could suggest an intentional perforation, though a natural origin cannot be ruled out.

Figure 3. Shell trumpet 408-24, from Can Tintorer, with the location of the holes A and B (figure by authors).

Testing shell trumpets for musical expression

Beyond their use for signalling over long distances, could the Neolithic shell trumpets found in Catalonia also have served as musical instruments? Together with information about sound pressure level, our analysis of musicality focuses on harmonic series and pitch, both of which are directly linked to musical capabilities. We also revisit the potential impact of holes here, this time examining their influence on the pitch produced.

Harmonic series

Each conch shell has a fundamental frequency (f o ), which is the lowest natural frequency at which it vibrates when producing sound. The notes with the best quality and greatest intensity correspond to this fundamental frequency. In shell trumpets, f o is determined by the length of the tube, with harmonics occurring at integer multiples (2f o, 3f o, 4f o, etc.) (Kolar Reference Kolar2020: 55). An experienced player can produce several of these overtones by modulating air pressure, generating different intervals. This harmonic series is determined by the morphology of the shell trumpets, following Archimede’s spiral law (Rath & Naik Reference Rath and Naik2009; Fritz et al. Reference Fritz2021).

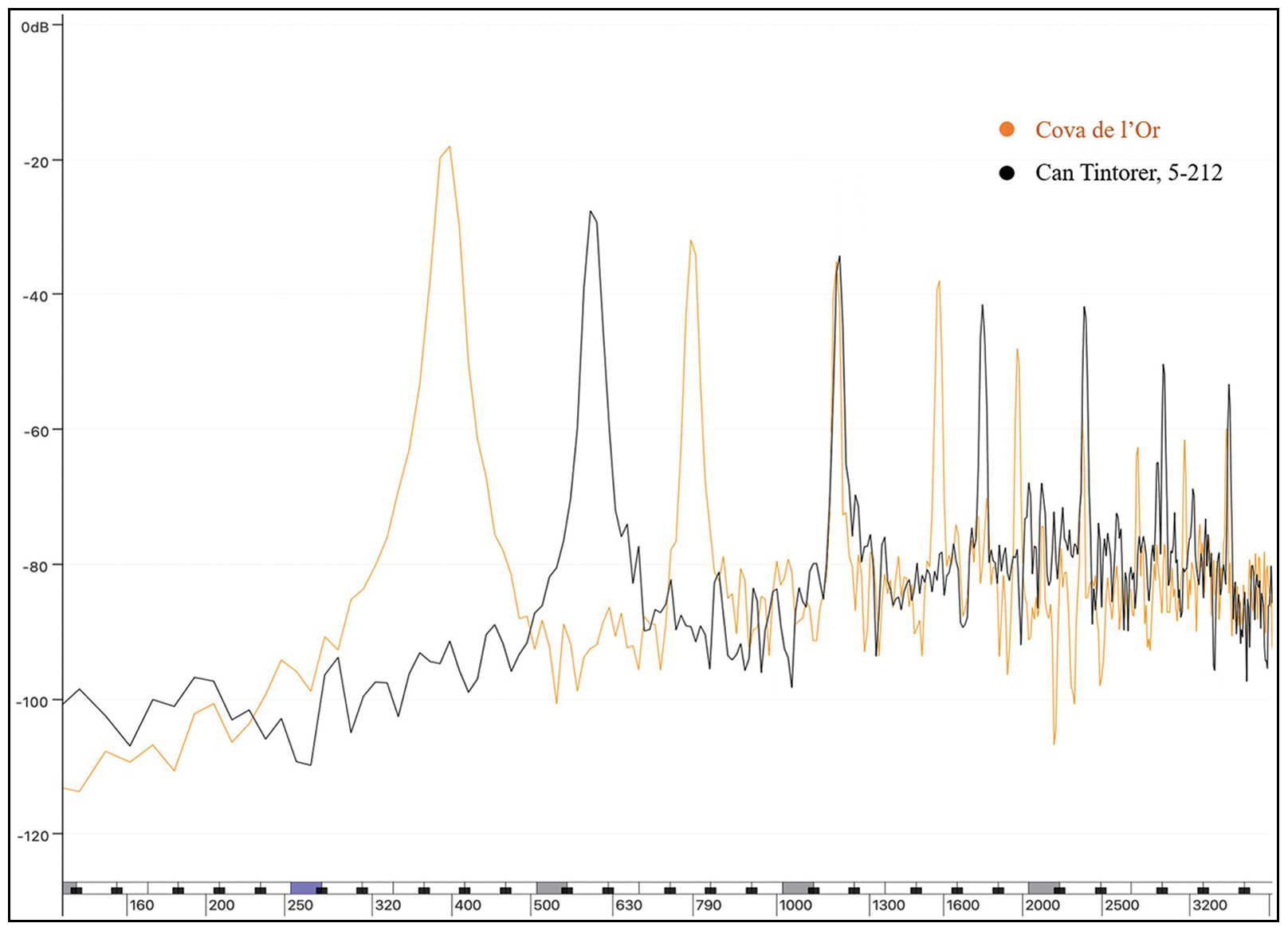

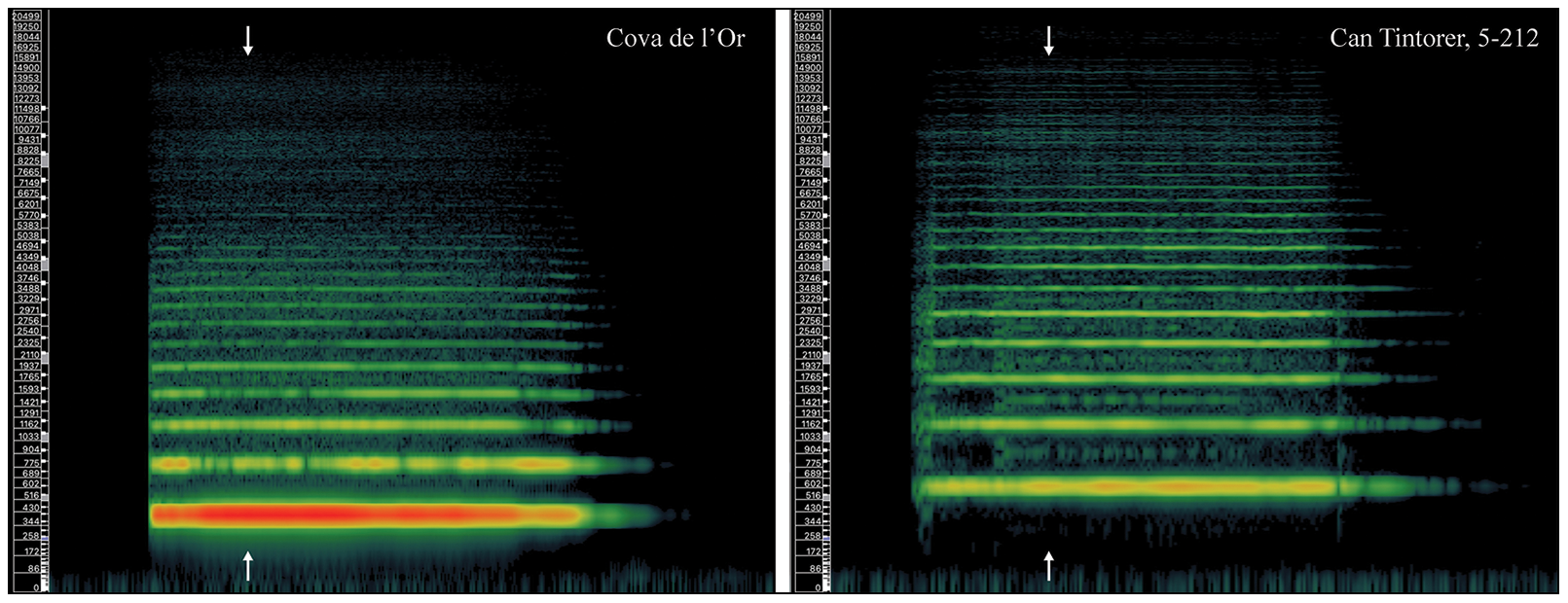

Spectral analyses of the sounds produced by each shell trumpet (Figures 4 & 5) confirm the expected harmonic series, though slight deviations occur due to irregularities in the conical structure of the instruments, such as perforations or interior concretions, as well as factors introduced by the performer, particularly when exerting greater effort to produce higher harmonics. These acoustic effects confirm that the internal acoustic channel’s function originally corresponded to that of a regular conical tube, with most observed alterations likely resulting from post-depositional processes.

Figure 4. Spectrum of the fundamental frequency (f0) of the shell trumpets from Cova de l’Or (CO221.9; orange) and Can Tintorer (5-212) (black) (figure by authors).

Figure 5. Spectrograms of the fundamental frequency (f0) of the shell trumpets from Cova de l’Or (CO221.9) and Can Tintorer (5-212) (figure by authors).

In our tests, up to three distinct pitches of good quality were achieved from shells C02221.9 and 408-24 (Table 2): the fundamental, the octave and the octave-plus-fifth. However, as one moves up the harmonic series, there is a progressive loss of energy and increased tonal instability, reflected in a higher standard deviation of pitch. Furthermore, playing techniques such as hand-stopping (which creates an effect similar to bore elongation; Kolar et al. Reference Kolar, Fritz and Tosello2022: 56) and bending (modifying the pitch through small adjustments in lip tension and position) reduce both the stability and intensity of the sound.

In contrast, the production of quality pitches beyond the fundamental was almost impossible on shells with larger apical openings. Analysis of the eight shells therefore reveals that the size of the apical opening substantially influences pitch quality and stability. Shells with larger apical openings (>30mm) are limited in the production of pitches beyond the fundamental, while those with smaller openings (around 20mm) enhance tonal stability and facilitate the generation of overtones. The results indicate that the right diameter and regularity of the apical opening are crucial for obtaining functional instruments and producing good-quality notes (Figure 6). While instruments with larger openings can achieve high intensity, they are harder to play and result in unstable notes with higher frequency variation.

Figure 6. Details of the apical cut from the shell trumpets 355-1-51 from Mas d’en Boixos (left) and 408-24 from Gavà Mines (right) (figure by authors).

Pitch

Seven of the shell trumpets have a fundamental frequency between 395 and 471Hz (∼G4–A#4), the exception being specimen 5-212 from Gavà (595Hz, ≈D5) (Table 2). The second harmonics, produced with good quality in three cases, were close to an octave above the fundamental, though with slight deviations from the expected values based on conical tube theory: 842Hz instead of 868, 812Hz instead of 790, and 976Hz instead of 942. The third harmonics were only produced by two shells (C02221.9 and 408-24) and were lower than expected: 1178Hz instead of 1302 and 1083Hz instead of 1185. Overall, these Neolithic shells exhibit substantially higher pitches than those documented in South American (Cook et al. Reference Cook2010: 7; Herrera et al. Reference Herrera, Espitia, García, Morris, Stöckli and Howell2014: 156), Asian (Rath & Naik Reference Rath and Naik2009: 526) and European (Fritz et al. Reference Fritz2021) specimens, though this difference does not affect their performance.

Assessing the impact of holes on musicality

The holes in shell 408-24 from Gavà and 332-1-3 from Mas d’en Boixos do not appear to have functioned as tone holes—that is, they were never intended to change pitch—since opening or closing them did not result in any perceivable tonal variation. This outcome is as expected, because there is little ethnographic evidence supporting such a use (Cook et al. Reference Cook2010: 14).

Discussion

Based on the results obtained from the acoustic testing of the eight playable shell trumpets from Neolithic Catalonia, we argue that the primary acoustic characteristic of these instruments—their most notable and likely most functional feature—is their high sound intensity, which aligns with their interpretation as signalling instruments. In this context, techniques such as bending or hand-stopping, which involve a loss of energy, may aid expression but would likely hinder the effectiveness of signalling over long distances. A similar issue applies to overtones: producing them requires more effort and technical skill, and the resulting sound tends to be weaker in terms of intensity.

Shell trumpets may have enabled long-distance communication due to their high sound pressure levels, surpassing any other known prehistoric tool in acoustic power. This capability enabled controlled sound transmission beyond visual range, and perhaps over several kilometres (Matamoros et al. Reference Matamoros, Ruiz, Garcia and Moreno2011; van Dyke et al. Reference van Dyke, Primeau, Throgmorton and Witt2024). The Neolithic use of shell trumpets in Catalonia appears to concentrate in a small region that is believed to have had a high population density (Esteve et al. Reference Esteve, Martín, Oms, López and Jornet2012). The sites of Mas d’en Boixos and Cal Pere Pastor, located less than 5km apart in the fertile Penedès depression, exemplify this pattern. Their proximity raises the possibility that shell trumpets served as communication tools, either between different communities inhabiting the region or between these settlements and individuals working in the surrounding agricultural landscape. A comparable scenario might be proposed for the Barcelona plain, in connection with the specimen from Espalter, as well as for mountainous areas, particularly regarding the example from Cova de l’Or. The shell trumpets from the Gavà mines, in turn, may have fulfilled multiple functions, including signalling within the mining galleries. If so, shell trumpets could be considered an archaeological indicator for the existence of complex activities, involving the co-ordination of people over long distances and in areas with an interrupted line-of-sight.

In addition to a primary function as signalling devices, our acoustic studies reveal that shell trumpets also possessed significant expressive potential. The best-preserved specimens can produce up to three stable notes. From these notes, it is possible to modulate pitch and produce melodies through techniques like bending or hand stopping, allowing tonal variations of up to a descending major third. These instruments further exhibit a remarkable responsiveness to dynamic variation and articulation. Consequently, an experienced player could not only produce signals but also develop complex, rich and expressive sound discourses.

Experimentation also suggests that shell trumpets could have been played using alternative techniques. For instance, a more relaxed lip vibration could generate lower frequencies (below the fundamental), producing a rougher timbre and reduced sound intensity, but still holding expressive potential. Another possibility is their use as amplifiers or distorters of the human voice—a function explored in other contexts (e.g. Cortese et al. Reference Cortese, del Lucchese and Garibaldi2004; Jiménez Pasalodos Reference Jiménez Pasalodos2019)—though with limited and barely audible results in the case of the Catalan shells.

As a final point, study of the Neolithic shell trumpets in Catalonia, as with other archaeological instruments, raises the challenge of distinguishing between sound characteristics shaped by intentional design and those dictated by available raw materials. A key example of this debate is the tonal pattern of the shell trumpets. Since the fundamental frequency is determined by the shell’s length, this raises questions about whether specimens were deliberately selected based on this characteristic or if their tuning was a coincidental result. Conch shells with fundamental frequencies between 395 and 471Hz have lengths of 140–191mm. Reductions in length due to apex cutting are estimated at 15–25 per cent, not accounting for damage to the peristome and siphonal canal. Thus, prior to these modifications, their sizes would have ranged from 180–260mm, which is typical for Charonia lampas. While larger specimens exist, the relationship between acoustic performance and size suggests that medium-sized specimens may have been the most suitable for use as signalling instruments, offering a balance between sound power and portability. It is therefore plausible that a selection process took place, favouring medium-sized shells.

Conclusions

At least 12 largely complete shell trumpets have been documented from five Neolithic sites in Catalonia. Of these, eight can still be made to produce sound, enabling an acoustic study of the sound characteristics of these north-east Iberian instruments. The production of high sound intensity may indicate a primary function in signalling over long distances, though expressive qualities also hint at broader musical applications. A tendency towards fundamental frequencies between 400 and 470Hz, substantially higher than those documented in other areas of the world, also suggests a possible selectivity in the size of shells collected for use. From an archaeoacoustic perspective, our data reinforce the hypothesis that these shells played a key role in long-distance communication and, consequently, in the structuring of the prehistoric soundscape. In their ability to extend the range of human activity, these shell trumpets were more than just sound tools; they had agency in shaping the spatial, economic and social dynamics of Neolithic communities.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the museum curators who facilitated access to the shell trumpets. We are especially grateful to Zorana Đorđević and Lidia Álvarez-Morales for their advice, and to Josep Maria Solias and Juana M. Huélamo for their practical assistance in the study of the specimen from Cova de l’Or.

Funding statement

This research work was undertaken by the Artsoundscapes project funded by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (2018–2025) (grant agreement no. 787842, Principal Investigator: ICREA Research Professor Margarita Díaz-Andreu).

Data availability

The original data presented in the study are openly available in CORA. Repositori de Dades de Recerca, Universitat de Barcelona (https://doi.org/10.34810/data2242).

Online supplementary material (OSM)

To access supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10220 and select the supplementary materials tab.

Author Contributions: CRediT categories

Miquel López-Garcia: Conceptualization-Equal, Formal analysis-Lead, Investigation-Equal, Methodology-Equal, Visualization-Lead, Writing - original draft-Lead, Writing - review & editing-Equal. Margarita Díaz-Andreu: Conceptualization-Equal, Formal analysis-Supporting, Funding acquisition-Lead, Investigation-Equal, Methodology-Equal, Project administration-Lead, Supervision-Lead, Writing - review & editing-Equal.