Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic dominated Finnish politics in 2020, a year which had no elections. The newly established Prime Minister Marin I government was successful in Covid-19 policy. Borders were closed and the regional closure of Uusimaa dominated politics in March and April. Over the year, the key debate on Covid-19 concerned face masks which were initially not recommended by the government, as no necessary supplies were available, while from August recommendations for mask-wearing were issued for the second wave. The opposition also criticized the government for not reopening the economy and for taking loans, debate intensifying particularly in the autumn before the second wave. During the pandemic, legislative processes were minimal and focused on Covid-19 control. Key legislation was passed on education reform.

Cabinet report

The year started with a climate meeting organized by the Marin I government in February 2020, but this faded in the face of the pandemic. The focus shifted to the pandemic from 27 February. Out of the 264 government Bills to Parliament, 86 regarded Covid-19 control. The policy adapted became one of ‘test, track, isolate, and treat to manage and control the pandemic’ (Häyry, Reference Häyry2021: 46). The ministerial presence across the government led by the Social Democratic Party's/Sosialidemokraattinen puolue (SDP) Sanna Marin was remarkably strong in the government press information sessions in the first wave in spring 2020, while in the second wave in the autumn 2020, the issue was delegated to one minister, Krista Kiuru (SDP), with strategic appearances by the Prime Minister (Koljonen and Palonen, Reference Koljonen and Palonen2021).

The leadership change in Centre Party/Keskusta (KESK) had an effect on the Cabinet's composition. Related to a scandal on her use of ministerial funds for public relations training (Palonen Reference Palonen2020), Katri Kulmuni resigned on 9 June, but continued as a chairperson for the party. Matti Vanhanen was asked to be Minister of Finance, and he acted as Deputy Prime Minister (9 June–10 September) before the election of a new chair for KESK. Annika Saarikko, Minister of Science and Culture, who had returned from maternity leave in August, was elected as the new chairperson for KESK on 5 September. Saarikko became Deputy Prime Minister, but continued as Minister of Science and Culture. The chairperson of the Left Alliance/Vasemmistoliitto (VAS), Li Andersson, left for maternity leave in December; Jussi Saramo was a replacement Minister of Education.

In addition, the Green League/Vihreä Liitto (VIHR) Minister of Foreign Affairs, Pekka Haavisto, was under debate: the Constitutional Law Committee held that Haavisto had broken his official government duty when he had moved a state employee to other duties because they disagreed with the government on matters regarding the repatriation of Finnish people from the al-Hol camp, but the threshold for prosecution of a minister was not reached (Palonen, Reference Palonen2020).

Parliament report

Parliament assessed the liability of the government twice in an interpellation by each of the main opposition parties: the Finns Party/Perussuomalaiset (PS; officially the Finns Party) parliamentary group leader Ville Tavio issued a question on 11 March about the government's refugee policy and Greece's temporary stand of not taking refugees. The chair of the National Coalition/Kokoomus (KOK), Petteri Orpo, issued a liability question on the abandonment of economic and employment targets on 18 September 2020 when the government's Covid-19 policies were criticized.

After the consensual period in spring 2020, when little was politicized due to the management of the pandemic, the questions of employment and recovery started to regenerate the government opposition debate and also cause stress between the governmental parties. The European Union's (EU) recovery package was heavily politicized in summer 2020 when Sanna Marin returned triumphant from the negotiations and declared she had made a good deal for Finland and held fast to the mandate the Grand Committee had set her. Generally increased borrowing, particularly the EU loan-taking, increased expenses and the pandemic's effects on the economy were criticized.

Covid-19 legislation passed by the government included a State of Emergency law for three months, school closures and the regional closure of Uusimaa, all unanimously supported in Parliament. Further issues included legislation on the distribution of medication and equipment for the health services, and restaurant closures from 4 April, reopened in the summer.

Measures for a renewed regional healthcare reform were revealed on 5 June by the Marin government. They were issued by the social and health sector ministers in a proposal on 9 October, and criticized on 14 December by the opposition parties, who saw funding as a key problem.

The composition changes were minimal. When Matti Vanhanen became a minister, Anu Vehviläinen took over as Speaker of Eduskunta. In terms of issues of the radical right, Ano Turtiainen (PS) was expelled from the party group for a racist tweet mocking George Floyd as well as for his regular commentary along the same lines. With Turtiainen in his own group, the two opposition parties PS and KOK became of equal strength.

A case on al-Hol refugee camp against Minister Pekka Haavisto (VIHR) led to no charges, but resulted in discussions in December on the independence and politics of the Constitutional Law Committee. Haavisto won Parliament's confidence on 15 December. However, the Greens’ interaction with other committee members was leaked and criticized in the social media by KESK, their usual rivals in government (Kervinen, Reference Kervinen2020).

The opposition criticized the government for Covid-19 communication, masks, and measures of recovery and continued restrictions. Parliament also voted on its confidence in the minister responsible for Covid-19 policy, and particularly facemasks, Krista Kiuru (SDP) on 14 October. The confusion between not recommending masks in spring and recommending them from August was behind the distrust that was used to politicize the issue and raise government–opposition confrontation. Kiuru retained Parliament's confidence and continued to lead the pandemic response (Hakahuhta, Reference Hakahuhta2020).

In summer 2020, the EU rescue package was discussed in Finland. Parliament and its Grand Committee fixed the Finnish cautionary stand on the issue. The government had reservations and the opposition parties would have been even more critical.

Legislation in preparation included social healthcare reform and terrorism legislation reform. Citizen initiatives to the Eduskunta addressed aviation tax, the privatization of water services, energy laws, issues on protected wildlife, legalizing cannabis use, abortion law, gender neutral ID numbering, and demands for a referendum on the EU rescue package.

Political party report

The year was one of relative stability. No new parties were registered in 2020. In the millennial female-led government (Palonen, Reference Palonen2020), Sanna Marin who became Prime Minister for the SDP in December 2019 became party chair only at the party convention in August. The second largest government party, KESK, renewed its leadership as Annika Saarikko was elected to the leadership on 5 September, following Katri Kulmuni, who had been misusing ministerial funding for personal public relations. The support rates for KESK were plummeting; they seemed not to be able to recover from the period in power under Prime Minister Sipilä 2015–19, and they prepared for local elections in 2021. Saarikko, with young children and just out of maternity leave, described herself as ‘a leader with feet in the rain puddles of the everyday life’ (Toivonen, Reference Toivonen2020). Saarikko from Turku, one of the second cities of Finland, but with roots in small towns, was famed for her capacity to speak to both the back country and those aspiring to live there – an increasing amount of Finnish city-dwellers under the pandemic conditions. Although the Left Alliance leader Li Andersson was on maternity leave, and deputy party leader Jussi Saramo covered her as Minister of Education, she retained her party leadership duties.

The biggest challenges were faced by PS who cut their ties to their youth organization and set up a new one. The quarrel started with deputy chair of the youth organization, Toni Jalonen, calling himself fascist. A new youth organization was established on 4 March. As the youth organization refused to oust their leader, it was denied state funding and declared bankruptcy. The questions of the radical right and fascist edge of the party had long been an issue for PS. The ousting of Ano Turtiainen from the parliamentary party group for racist comments showed this.

Institutional change report

The State of Emergency declared from 16 March to 15 June enabled the government to implement (parts of) the Emergency Powers Act that made possible restrictions that contradict the Constitution. The issues of its legality and process were discussed. Overall, Covid-19 control and restrictions were confronted with the Constitution and fundamental rights in Finnish political debates.

The persistent topic in Finnish politics and policy-making for two decades that also led to the previous governments’ downfall before the 2019 general elections, social welfare and healthcare reform, proceeded in the planning stage, with proposals for major changes to the regional level, for example, taxation. The decision of increasing compulsory education was raised from the first nine grades to 18 years old, but securing cost-free education would make the municipalities responsible for second tier or education and provision of schoolbooks, other supplies, and equipment, which previously were charged to students. Reversing previous governments’ restrictions by providing that every child has a right to have fulltime early childhood education regardless of their parents’ employment or residence (paperless and refugee children) situation further contributed to the educational investments.

Issues in national politics

In terms of Covid-19 debates, recovery was discussed throughout the year. The first recommendations including that for distance working and avoiding travel were issued on 12 March. A State of emergency was declared on 16 March, for first time since the oil crisis (1973–74) and the second time after the Second World War. The Emergency Powers Act concerned all levels of schooling with provisions for under 10-year-olds, the administrative sectors of social welfare and healthcare, working life, and restrictions on movement. The regional closure of Uusimaa capital region from 28 March to 15 April (initially legislated until 19 April) was used as a central tool for Covid-19 control in the first wave, but also debated from the perspective of civil liberties. The rationale of having police with the help of the military guard roads in and out of Uusimaa in the 30 border crossings was intended to keep the population in the capital region, including higher Covid-19 cases, out of their summer cottages and other Easter travels to less populated areas with weaker the health services. The closure was lifted and schools were reopened in late April. The State of Emergency was repealed on 15 June, when the first wave was over. During the summer, travel restrictions were discussed and lifted on 7 July for some countries and restored on 19 August.

Discussion about the second wave continued in early September, and while the second wave was seen as comparatively small, the situation was seen as getting worse in October. The government's initial failure to provide protective equipment led to discussions about face masks. The government ordered an independent study on the usefulness of face masks, which concluded that existing studies do not provide conclusive evidence of the protection of masks for those who wear them. The recommendation on face masks was only issued on 13 August and updated on 25 September. The government issued reasons for their reluctance on face masks on 14 October. Tighter restrictions were issued again at the turn of November–December, when on 26 November Prime Minister Marin called for people to avoid physical contact. In early December, attention was on vaccinations promised to everyone who wanted them.

Besides Covid-19, there were a range of issues related to climate, education and demography. The government raised its employment target from 60,000 now jobs to 80,000, and its aim is that Finland is carbon neutral by 2035. Free compulsory education was raised to 18 years, and a fulltime right to early childhood education was brought back. The ‘pension pipeline’ (eläkeputki) for early retirement would be discontinued starting in 2023.

The pandemic revealed problems in the rights of seasonal migrant workers, particularly in agriculture. It also revealed challenges in agriculture, families’ situations in the pandemic conditions and material inequality. The pandemic lockdown was restricted to the three-week border closure of Uusimaa, but also international travel was halted rapidly, and the state-owned aviation company Finnair and Helsinki airport were subsidised, being a key site for Asian travel. The establishment of testing and quarantine conditions for border crossing was delayed. Within the EU, Finnish policies of border closures were criticized. In a country located between the liberal approach countries of Sweden and Russia in Covid-19 control, the government decided to control the virus, and closing borders was a key to this process. This affected particularly the usual travel to Sweden at the land border of the north, in the Åland Islands and elsewhere in Finland where regular travel to Sweden for work and recreation was an issue. In the South Karelian region in the Eastern border to Russia, the usual traffic was halted. The Estonian border enabled travel for employment, and particularly the construction sites that were dependent on labour and were not closed for a lockdown, as Estonia had low levels of Covid-19. Positive attention abroad was gained from the low rates of Covid-19 and the government's press conference to school children organized on 24 April. In fact, the government addressed, in cooperation with non-governmental organizations, also the elderly in a similar press conference.

The role of the millennials in leadership gained attention in Finland and abroad. Simultaneously, in national debates concerns were voiced about youth: their survival, violent behaviour and mental health were discussed during the year with and without a connection to the pandemic. A road-block demonstration on climate was organized by the Elokapina movement in October, and they were pepper sprayed by the police, generating discussions on police action, activists and climate issues during the initial stages of the second wave of Covid-19 pandemic in Finland.

Table 1. Cabinet composition of Marin I in Finland in 2020

Source: Finnish Government website, 2020.

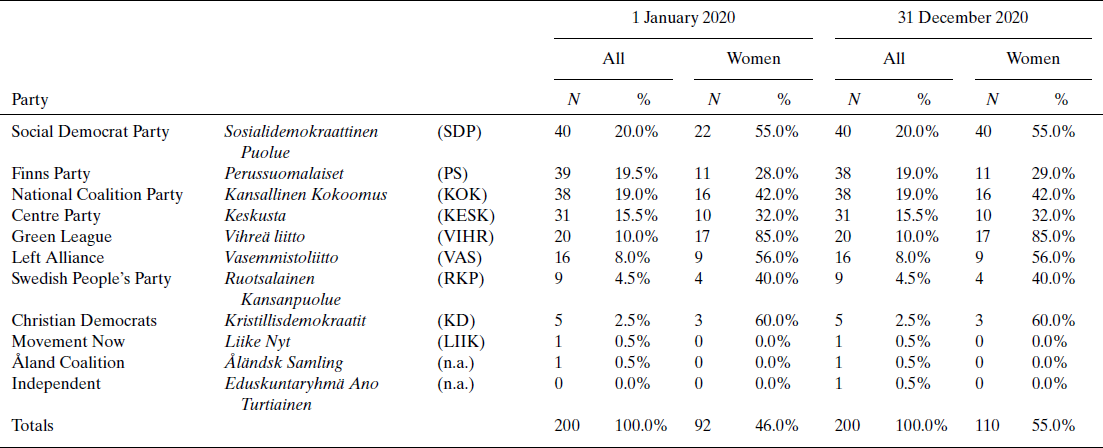

Table 2. Party and gender composition of Parliament (Eduskunta) in Finland in 2020

Source: Finnish Government website, 2020.

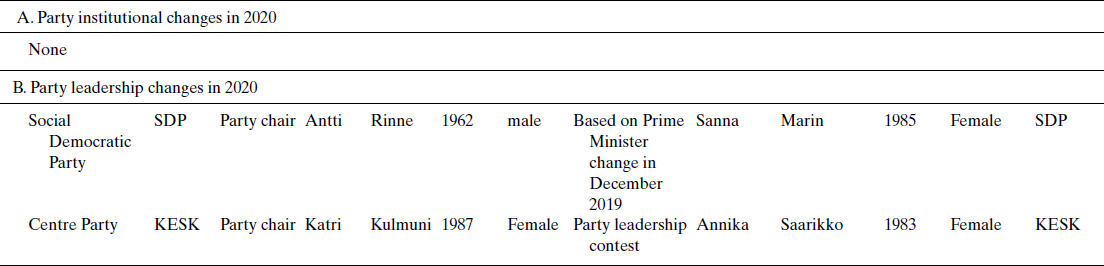

Table 3. Changes in political parties in Finland in 2020

Note: Marin had replaced Rinne as Prime Minister already in December 2019, as government partners (particularly the KESK) had distrusted Rinne, and as planned in the following party congress she was also named party leader.

2. Kulmuni's use of ministerial funds for public relations training was contested in 2019, which resulted in her later replacement as minister, and party leader at the next party congress. Saarikko was a sovereign candidate.