Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a significant challenge to public health and the number one cause of disability globally. Reference Liu, He, Yang, Feng, Zhao and Lyu1 Approximately one out of three patients with MDD receiving evidence-based treatment develop treatment-resistant depression (TRD), defined by the lack of substantial improvement following multiple trials of pharmacological and/or psychotherapeutic interventions. Reference Souery, Papakostas and Trivedi2 Ketamine, an anaesthetic agent with non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist properties, has garnered significant attention as an efficacious and rapid-acting intervention for TRD. Reference Sanacora, Frye, McDonald, Mathew, Turner and Schatzberg3 On meta-analysis, up to half of TRD patients respond (>50% improvement) within hours of a single intravenous ketamine dose, Reference McGirr, Berlim, Bond, Fleck, Yatham and Lam4 most commonly 0.5 mg/kg infused over 40 min. While impressive, ketamine’s benefits typically fade within days and intensive efforts to develop effective strategies to sustain response have largely yielded disappointing results. Reference Garel, Drury, Thibault Lévesque, Goyette, Lehmann and Looper5

One promising strategy to prolong and potentially augment ketamine’s benefits is to combine it with psychotherapy. Reference Drozdz, Goel, McGarr, Katz, Ritvo and Mattina6 Psychotherapy is known to produce relatively durable benefits in depression, Reference Karyotaki, Smit, Henningsen, Huibers, Robays and De Beurs7 and ketamine might enhance psychotherapy by several mechanisms: rapidly decreasing symptoms and thus improving treatment engagement, Reference Garel, Drury, Thibault Lévesque, Goyette, Lehmann and Looper5 facilitating learning through increased neuronal plasticity Reference Li, Lee, Liu, Banasr, Dwyer and Iwata8 and potentially producing ‘psychedelic’ experiences akin to the mystical-type and emotional experiences observed in trials of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy. Reference Drozdz, Goel, McGarr, Katz, Ritvo and Mattina6,Reference Greenway, Garel, Jerome and Feduccia9–Reference Johnson, Richards and Griffiths12 Psychedelic ketamine–psychotherapy approaches, which aim to cultivate therapeutic experiences using extra-pharmacological adjuncts such as music and psychological support, are generating growing interest. Reference Drozdz, Goel, McGarr, Katz, Ritvo and Mattina6 However, to our knowledge, no modern randomised clinical trial (RCT) has evaluated a psychedelic ketamine treatment approach for depression or TRD.

We recently reported the primary outcome of the Music for Subanesthetic Infusions of Ketamine (MUSIK) RCT, which found that music can significantly mitigate ketamine’s stimulatory effects on blood pressure in TRD. Reference Greenway, Garel, Dinh-Williams, Beaulieu, Turecki and Rej13 The current study presents the MUSIK trial’s secondary outcomes, that is, the immediate and sustained effects of the trial’s music and non-music ketamine–psychotherapy interventions on symptoms of depression, anxiety and suicidality, as well as group-level and within-person temporal relationships between symptom changes and the subjective ketamine experiences.

Method

Study setting

The MUSIK study was a prospective, two-centre, assessor-blinded RCT with a parallel two-arm design performed in Montreal, Canada, from January 2021 (first patient enrolled on 11 January 2021) to August 2022, approved by the ethics committees of the Douglas Mental Health Institute (#IUSMD-20-28) and the Jewish General Hospital (#MEO-14-2022-2854). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Patients aged 18–75 years old with TRD of at least moderate severity (MADRS ≥ 20) were prospectively enrolled, recruited by solicitation of clinicians and by screening of ongoing referrals at the ketamine services of the two study sites. Inclusion/exclusion criteria (listed in full in ‘sMethod’ in the Supplementary Material) were intentionally permissive to recruit a population of clinically representative TRD patients who are often excluded from clinical trials because of comorbidity and complexity. Reference Lundberg, Cars, Lööv, Söderling, Sundström and Tiihonen14,Reference Fabbri, Hagenaars, John, Williams, Shrine and Moles15

Study design

The full details of the study design are published in Greenway et al (2024). Reference Greenway, Garel, Dinh-Williams, Beaulieu, Turecki and Rej13 Briefly, after completing all screening and baseline procedures, participants were 1:1 randomised to receive either a curated music intervention or matched non-music support (control group) during a course of ketamine. Both groups received six subanaesthetic, 40-min ketamine infusions (0.5mg/kg bodyweight) over a 4-week period: bi-weekly (twice per week) during the initial 2 weeks then weekly for the subsequent 2 weeks. One in-person follow-up visit took place at week 8 (i.e. the 8-week follow-up, 4 weeks following the final ketamine dose).

Extra-pharmacological factors

Treatment environments were carefully curated to be serene, secluded and aesthetically pleasing (Supplementary sFigure 1). They contained the necessary medical equipment, soft lighting and decoration, including plants. Participants received infusions in a comfortable seated or reclined position, in a hospital bed or on a medical recliner. They were provided with one set of blindfolds at the trial outset and encouraged to wear them throughout every treatment.

During the 40-min ketamine infusions and up to 1 h after, participants were accompanied by a nurse and physician who ensured physiological tolerability and provided psychological support. Details of this support are described in a methods article detailing the Montreal Model of ketamine–psychotherapy. Reference Garel, Drury, Thibault Lévesque, Goyette, Lehmann and Looper5 Importantly, ketamine experiences were framed to participants as not pathological, but rather as potential sources of insight and experiential learning – for example, ‘learning to let go’. Reference Wolff, Evens, Mertens, Koslowski, Betzler and Gründer16 As part of the Montreal Model, all participants were required to have 1 h of weekly concomitant psychotherapy, independent of the trial personnel, throughout the treatment period to provide an external venue for discussion and exploration of treatment experiences. Psychiatric medications were kept constant throughout the treatment period, except that benzodiazepines or z-drugs were stopped gradually before the initial treatment. Reference Garel, Greenway, Dinh-Williams, Thibault-Levesque, Jutras-Aswad and Turecki17

Study intervention: music

In the music group, music was played through headphones as well as speakers in the room beginning at the start of each ketamine infusion and concluding approximately 50–60 min thereafter. Participants were presented with a variety of curated playlists to select from at the beginning of each treatment, developed based on literature guidance and past trials of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Reference Kaelen, Giribaldi, Raine, Evans, Timmerman and Rodriguez18 All playlists, published elsewhere, Reference Greenway, Garel, Dinh-Williams, Beaulieu, Turecki and Rej13 adhered to a consistent format, commencing with soothing compositions, gradually increasing in intensity and complexity after about 10–15 min and concluding with calming music for the final 20 min. At the playlist’s conclusion, participants were engaged in discussion of their ketamine experiences for 30 min. After each treatment, participants were provided with its playlist and encouraged to re-listen to it to revisit and ‘integrate’ their experiences.

Control condition: non-music support

The control condition was designed to match the music group except for the use of music, including the time spent in the presence of clinicians and care provided outside of treatment sessions. In place of music, participants received gentle encouragement to engage in mindfulness practices, such as body-scanning and breath awareness, towards fostering relaxation and cultivating curiosity for the ketamine experience. Participants were free to remain silent throughout the infusions or to discuss their experiences with clinical staff. Outside of treatment visits, participants were encouraged to revisit their experiences through similar mindfulness practices.

Outcome measures

Baseline demographics

As per the protocol, Reference Greenway, Garel, Dinh-Williams, Beaulieu, Turecki and Rej13 all eligible patients underwent a diagnostic interview with a study psychiatrist. Based on this interview, treatment resistance was quantified using the Dutch Measure for quantification of Treatment Resistance in Depression (DM-TRD), a validated composite score based on factors including treatment failures, comorbidity and functional impairment. Reference Peeters, Ruhe, Wichers, Abidi, Kaub and van der Lande19

Clinical outcomes

Outcomes were measured at baseline and at each treatment session during the 4-week treatment phase, as well as at the 8-week follow-up. The primary therapeutic outcome was the clinician-rated Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) at 4 weeks. Reference Galinowski and Lehert20 A trained clinician such as a psychiatrist or a research assistant with at least a master’s degree, blinded to the patient assignment, completed the MADRS at each study visit. Other secondary outcomes included the MADRS at 8 weeks, and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Reference Beck, Steer, Ball and Ranieri21 the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-A, state version) Reference Spielberger22 and the current-moment Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (SSI), Reference Beck, Kovacs and Weissman23 at 4 and 8 weeks. Their details can be found in the study protocol. Reference Greenway, Garel, Dinh-Williams, Beaulieu, Turecki and Rej13

Psychedelic experiences

Experience-related outcomes were quantified immediately following the ketamine infusions by the 30-item Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ) Reference Barrett, Johnson and Griffiths24 and the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory (EBI). Reference Roseman, Haijen, Idialu-Ikato, Kaelen, Watts and Carhart-Harris25 The MEQ assesses acute ‘mystical-type’ experiences through a 6-point Likert-type scale, from 0 (none) to 5 (extreme). Total scores range from 0 to 150, with higher scores indicating greater mystical experiences, and there are four subscales: ‘Mystical’, ‘Positive Mood’, ‘Transcendence of Time and Space’ and ‘Ineffability’. Reference MacLean, Johnson and Griffiths26 The MEQ has been used extensively in modern serotonergic psychedelic clinical trials, demonstrating high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.933) and predictive validity for long-term psychological outcomes. Reference Davis, Barrett, May, Cosimano, Sepeda and Johnson10,Reference Garcia-Romeu, Davis, Erowid, Erowid, Griffiths and Johnson11,Reference Barrett, Johnson and Griffiths24,Reference Bogenschutz, Ross, Bhatt, Baron, Forcehimes and Laska27 The EBI assesses acute emotional experiences by six visual analogue scales (VASs), with scores ranging from 0 (’No, not more than usual’) to 100 (’Yes, entirely or completely’). The six questions are averaged to yield a total score ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater emotional breakthrough experiences. The EBI also shows high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.932) and potential mediator effects for long-term psychological benefits after serotonergic psychedelics. Reference Roseman, Haijen, Idialu-Ikato, Kaelen, Watts and Carhart-Harris25

Safety assessments

Vital signs were monitored at 0, 15, 30 and 40 min during each ketamine infusion. Potential adverse effects during and after ketamine sessions (e.g. headache, nausea and vomiting and neuropsychiatric symptoms) were solicited and recorded as per the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Adverse Events Information at all study visits. Reference Brown, Wood and Wood28

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R version 4.0.2 for Windows (R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; see https://www.R-project.org/) and R Studio version 1.3.1093 for Windows (RStudio, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; see https://rstudio.com/products/rstudio). Changes from baseline to the end of the 4-week intervention and to 8-week follow-up were analysed using Welch’s unpaired and Student’s paired t-tests for the MADRS, BDI, STAI-state and SSI outcomes. Welch’s t-tests were utilised for group differences to account for the unequal variances between the music and non-music groups, Reference Delacre, Lakens and Leys29 and paired t-tests were used to evaluate pre–post changes. The results are presented with and without application of a stringent Bonferroni correction based on 16 comparisons. There were no planned subgroup analyses given the relatively small sample size and repeated measure study design.

To explore psychedelic ketamine experiences as potential mechanisms of change in depressive symptoms, we employed multilevel modelling (MLM) lagged time-varying covariate models with autoregressive residuals using the R package ‘nlme’ version 3.1-162 for Windows (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria; see https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/nlme/). First, in four separate models using treatment number as a fixed effect predictor, we examined whether the number of ketamine infusions predicted the following outcomes: post-treatment changes in depressive symptom scores (MADRS, BDI) or higher scores on psychedelic experience scales (MEQ or EBI). Following guidelines for evaluating causal inference, Reference Kazdin30 we then examined the temporal precedence of psychedelic experiences relative to changes in depression. Autoregressive, cross-lagged models tested whether psychedelic experience scales predicted decreases in depressive symptoms to the subsequent timepoint. In four models, standardised within-person psychedelic experience scores (MEQ or EBI at time t–1) were utilised as predictors of depressive symptoms (MADRS or BDI) at the subsequent timepoint (time t), that is, whether a relatively more mystical or emotional ketamine experience at time t–1 was predictive of relatively greater improvements in clinician-rated or self-report depressive symptoms at the next timepoint, time t. To account for potential influences of depressive symptoms and the number of treatments on a given ketamine experience’s psychedelic qualities, lagged, standardised within-person depression scores (rated immediately before a given dose) and treatment number were included as covariates.

As temporality requires unidirectionality – that is, that a proposed mechanism predicts subsequent changes in outcomes but not the other way around Reference Kazdin and Nock31 – we also conducted similar analyses in reverse. These final four MLM models examined standardised within-person depression variables (MADRS or BDI) as predictors of subsequent psychedelic experiences (MEQ or EBI). Analogous to the previous models, treatment number and lagged within-person standardised experience (time t–1) markers were included as covariates.

To complement the session-by-session MLM analyses and facilitate comparisons to the literature, we conducted linear regressions examining changes in symptoms and both peak and average psychedelic experiences as have been conducted in recent studies with psilocybin. Reference Davis, Barrett, May, Cosimano, Sepeda and Johnson10,Reference Garcia-Romeu, Davis, Erowid, Erowid, Griffiths and Johnson11,Reference Barrett, Johnson and Griffiths24,Reference Bogenschutz, Ross, Bhatt, Baron, Forcehimes and Laska27 These analyses examined relationships between a given participant’s average or maximal EBI or MEQ scores, across treatments 1–6, and their relative changes in clinical outcomes (MADRS, BDI, STAI-A, SSI) from baseline to end of treatment (week 4), as well as at the 8-week follow-up. The model fit was evaluated using the coefficient of determination R 2, adjusted to account for the number of predictors and prevent overfitting to yield somewhat more conservative adjusted R 2 values. Statistical significance was determined by p-value < 0.05.

Results

Demographics

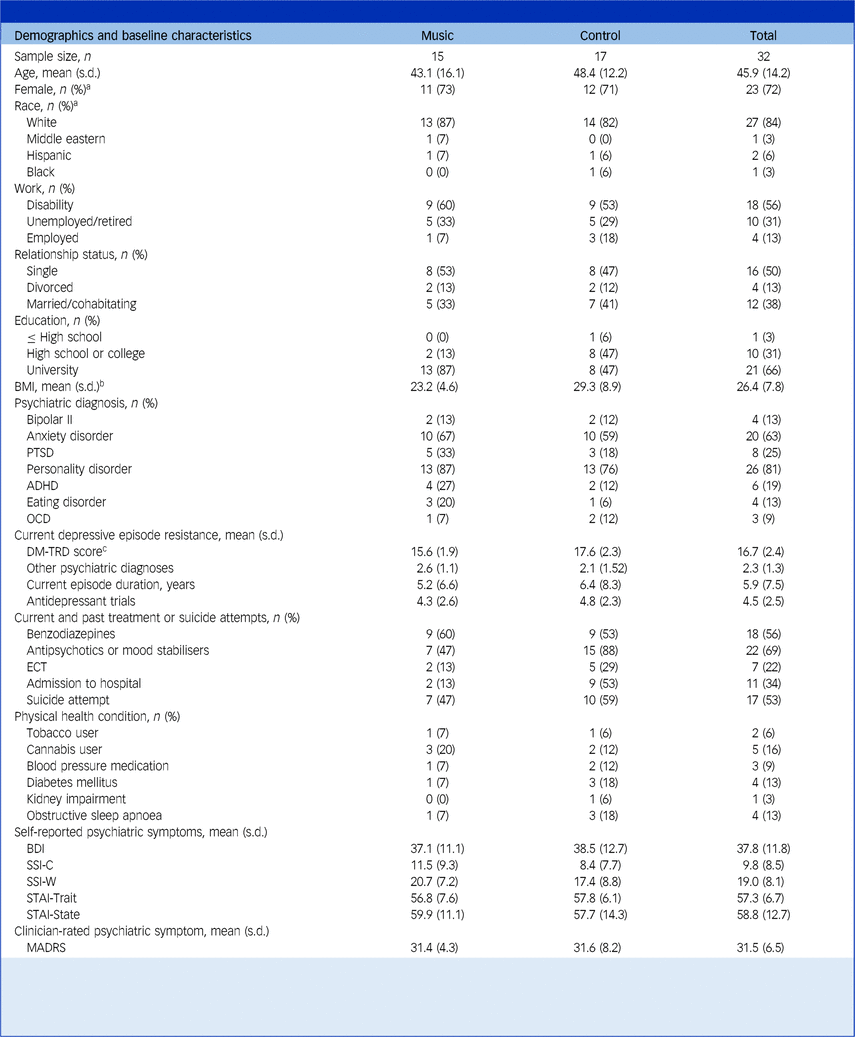

A consort diagram summarising recruitment of participants, treatment exposure and retention is published in Greenway et al. Reference Greenway, Garel, Dinh-Williams, Beaulieu, Turecki and Rej13 Briefly, of the 40 participants with TRD assessed during the recruitment period, 32 met inclusion criteria for ketamine and were approached for study enrolment. All agreed to participate and were randomised. A total of 181 ketamine infusions were administered of a planned 194 (94%). Twenty-eight (88%) participants completed all visits per protocol; 23 (72%) participants were women, the mean (s.d.) age was 45.9 (14.2) years, with mean (s.d.) depressive score on the MADRS of 31.5 (6.5) and on the BDI of 37.8 (11.8). Mean (s.d.) scores on the DM-TRD were 16.7 (2.36); mean (s.d.) number of psychiatric diagnoses was 3.3 (1.3), with 26 (81%) participants having a personality disorder, 25 (78%) participants experiencing significant suicidality (SSI > 2) and seven (22%) having received electroconvulsive therapy during their current depressive episode. Participants’ demographics and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1, which did not differ significantly between treatment groups at baseline.

Table 1 Demographics and baseline characteristics organised by groups and for the total sample

BMI, body mass index; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; DM-TRD, Dutch Measure for quantification of Treatment Resistance in Depression; ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; BDI, Beck Depressive Inventory; SSI-C, Scale for Suicide Ideation Current; SSI-W, Scale for Suicide Ideation Worst; STAI, State Trait Anxiety Inventory; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

a. Self-reported.

b. Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared.

c. DM-TRD is a reliable and valid multidimensional measure for quantification of the severity of a treatment-resistant depressive episode, based on multiple clinical variables.

Inter-group comparisons

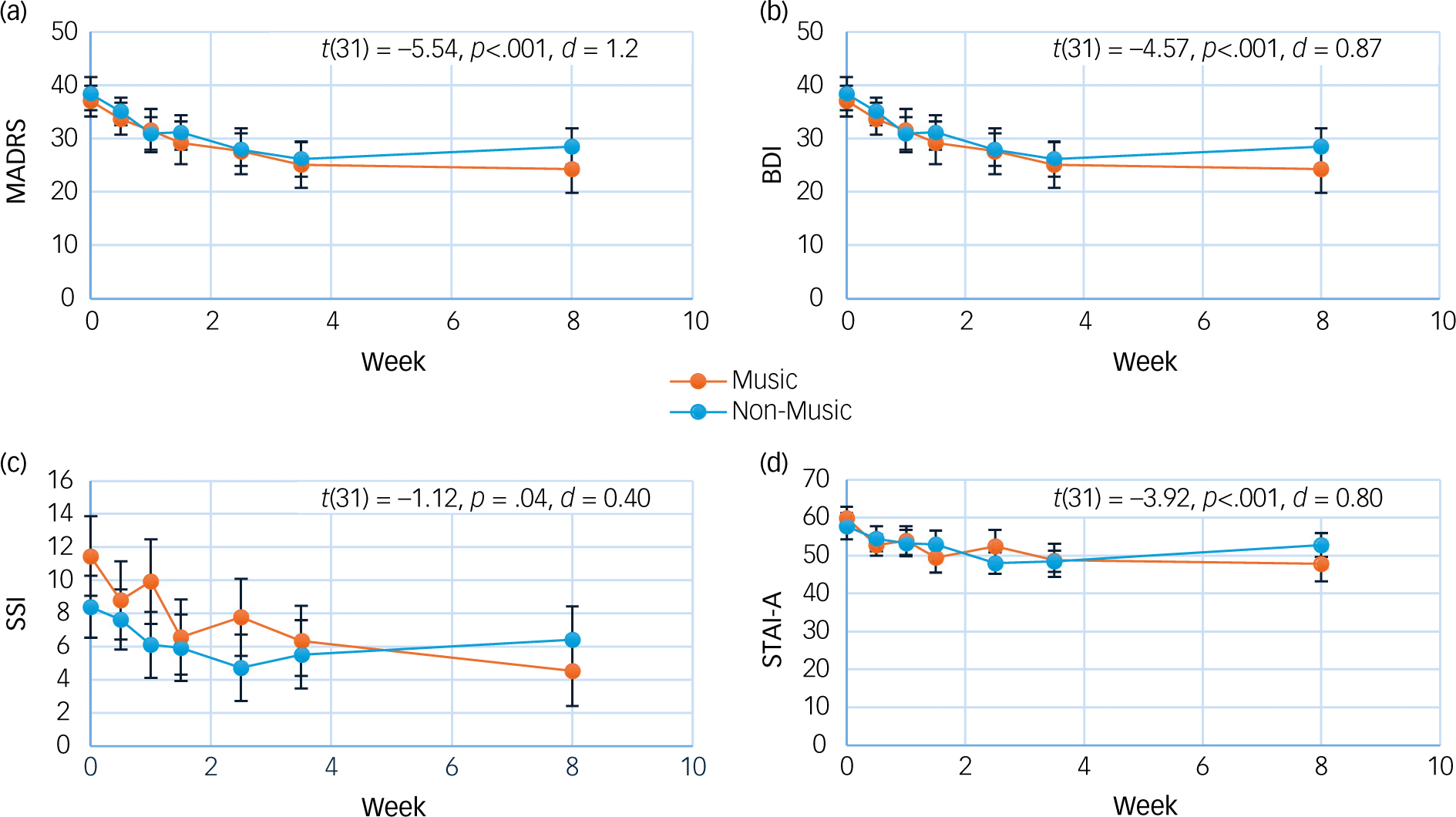

A two-tailed, unpaired t-test revealed that changes in clinician-rated depression scores of the MADRS did not differ between music versus non-music groups at 4 weeks (t(29) = −1.44, p = 0.16), before or after correcting for multiple comparisons (see ‘sResults’ in the Supplementary Material). Similarly, self-rated depression scores (BDI) did not significantly differ between conditions at 4 weeks (t(21) = −0.23, p = 0.82) (Fig. 1). There were also no significant group differences in depression scores at 8 weeks, nor at either 4 weeks or 8 weeks for anxiety or suicidality as measured by the STAI-A and SSI, respectively (see sResults for further statistical test results).

Fig. 1 Mean depression ((a) Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), (b) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)), suicidality ((c) Scale for Suicide Ideation (SSI)) and anxiety ((d) State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-A)) scores by group. T-test results represent changes across time, both groups combined. Error bars are standard errors; p-values are uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

Change across time, both groups combined

Two-tailed, paired t-tests demonstrated large reductions in depressive symptoms from baseline to 4 weeks: average MADRS scores decreased from 31.5 to 19.7 (t(31) = −5.54, p < 0.001, d = 1.2). Similarly large decreases at end of treatment were observed on the BDI (t(31) = −4.57, p < 0.001, d = 0.87) and for anxiety as measured by the STAI-A (t(31) = −3.92, p < 0.001, d = 0.8). Moderate reductions in suicidality as measured by the SSI were also observed (t(31) = −2.12, p = 0.04, d = 0.4). At 8 weeks, these effects were maintained: large reductions in depressive symptoms were observed for the MADRS (t(28) = −5.20, p < 0.001, d = 1.2) and the BDI (t(31) = −4.72, p < 0.001, d = 0.97), as well as for anxiety (t(31) = −2.46, p = 0.02, d = 0.8) and suicidality (t(31) = −2.37, p = 0.02, d = 0.5) (Fig. 1). All pre–post results remained significant after Bonferroni corrections, with the exception of improvements in suicidality at both 4 and 8 weeks, as well as anxiety at 8 weeks (Supplementary sTable 1).

Psychedelic experiences as mechanisms of change

Descriptive statistics

Mean (s.d.) MEQ and EBI scores for the 181 infusions were 66.6 (35.3) and 35.7 (18.4), respectively, and peak (maximal scores for a given participant) were 88.7 (40.5) and 60.0 (23.8), respectively. As illustrated in Supplementary sFigure 2, MEQ and EBI scores were similar between groups. Across the six treatments, MEQ scores remained relatively constant whereas EBI scores significantly increased with subsequent treatment, as reflected in the MLM models below.

Test of temporality

In autoregressive MLM models, the number of ketamine treatments predicted larger decreases in depressive symptoms for both the MADRS (β = −2.49, p < 0.001) and the BDI (β = −2.13, p < 0.001), indicating that additional ketamine sessions were related to further clinician-rated and self-report antidepressant effects. Additional ketamine sessions were also significantly associated with increasing EBI scores (β = 3.17, p < 0.001) but not changes in MEQ scores (β = 1.65, p = 0.15).

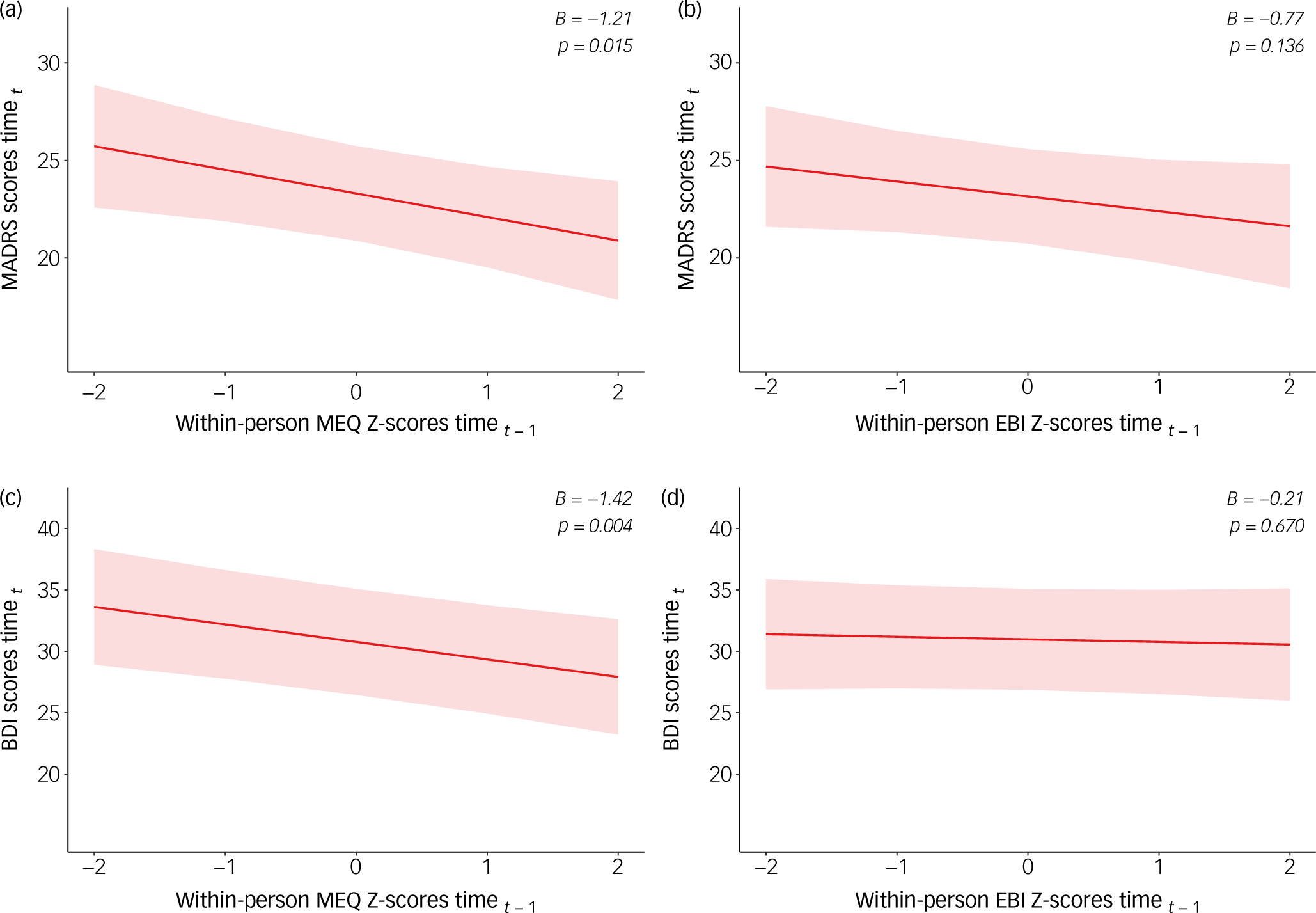

The cross-lagged MLM models examining session-by-session associations between psychedelic experience scales and subsequent changes in depression revealed significant associations for the MEQ and for the EBI when treatment number was not included as a covariate. When controlling for the number of treatments, the associations between the EBI and both depression scales were no longer significant (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2). In contrast, MEQ scores at time t–1 were significantly associated with subsequent decreases in both MADRS (β = −1.21, p = 0.015) and BDI (β = −1.42, p = 0.004) scores at time t, even controlling for accumulating antidepressant effects of treatment.

Fig. 2 Multilevel cross-lagged models of within-person standardised psychedelic experiences and depressive symptoms. MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MEQ, Mystical Experience Questionnaire; EBI, Emotional Breakthrough Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory.

The reverse relationship was not observed for the MEQ: within-person depression scores at time t–1 were not significantly associated with subsequent MEQ scores at time t, for either the MADRS (p = 0.72) or BDI (p = 0.43) (Supplementary Figure 3). In contrast, depression scores at time t–1 were significantly associated with EBI scores at the subsequent time t for the MADRS (β = −3.75, p = 0.019), with a similar trend for the BDI (β = −2.05, p = 0.185) (Supplementary sFigure 3).

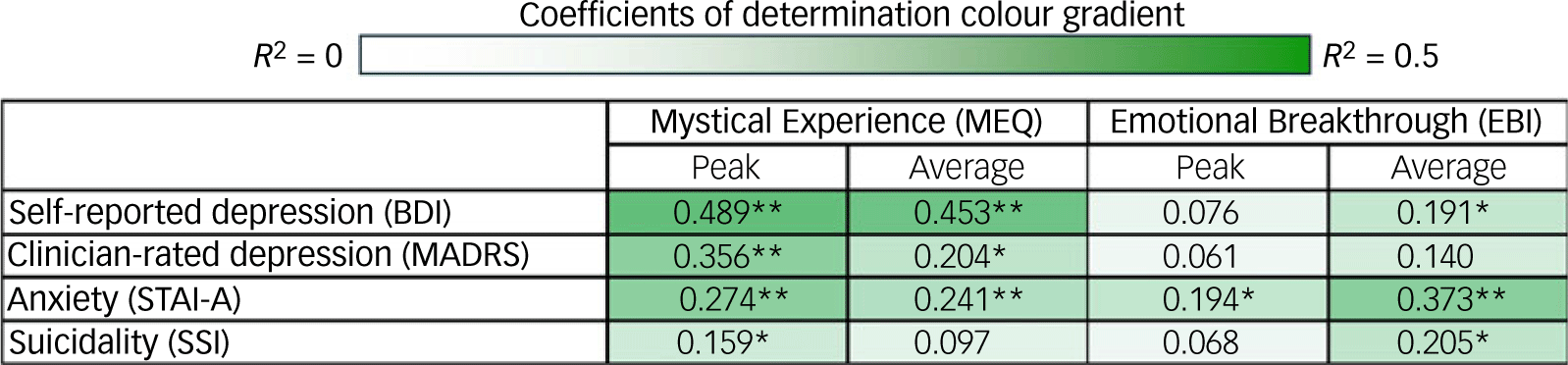

Peak and average experiences

Peak MEQ scores were strongly correlated with relative changes in MADRS (adjusted R 2 = 0.356, p < 0.001) and BDI (adjusted R 2 = 0.489, p < 0.001) scores from baseline to week 4. Regression β coefficients for the MADRS (β = −0.142, 95% CI −0.221, −0.063) and BDI (β = −0.210, 95% CI −0.298, −2.10) indicated that higher peak MEQ scores were associated with greater antidepressant effects. Similarly, average MEQ scores were significantly associated with improved depressive symptoms, for both the MADRS (adjusted R 2 = 0.204, p = 0.02; β = −0.124, 95% CI −0.224, −0.023) and the BDI (adjusted R 2 = 0.452, p < 0.001; β = −0.232, 95% CI −0.337, −0.127).

Peak EBI scores were not associated with greater improvements in depression from baseline to week 4, as measured by the MADRS (adjusted R 2 = 0.061, p = 0.21) or the BDI (adjusted R 2 = 0.076, p = 0.16). Average EBI scores and depression improvements approached significance for the MADRS (adjusted R 2 = 0.140, p = 0.05; β = −0.196, 95% CI −0.966, 0.004) and reached significance for the BDI (adjusted R 2 = 0.191, p = 0.02; β = −0.288, 95% CI −0.533, −0.044).

As summarised in Fig. 3 and presented in the Supplementary Material (sTable 2), both peak and average MEQ scores were significantly associated with improvements in anxiety, whereas only peak MEQ scores were significantly associated with improvements in suicidality. Peak EBI scores were only associated with improvements in anxiety, whereas average EBI scores were associated with improvements in both anxiety and suicidality.

Fig. 3 Correlational matrix of average and peak (maximal scores for a given participant) Mystical Experience Questionnaire and Emotional Breakthrough Inventory scores with symptom changes from baseline to week 4. BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; MADRS, Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; STAI-A, State Trait Anxiety Inventory; SSI, Scale for Suicide Ideation. Values are coefficients of determination (R 2; Supplementary sTable 2). Heatmap represents lowest (near white) to highest (dark green) R 2 values *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Similar analyses were conducted using the 8-week follow-up outcomes (Supplementary sTable 3). These analyses yielded an overall similar pattern of consistently negative relationships, although several relationships that were significant (p < 0.05) at the 4-week timepoint were not at the 8-week follow-up (average MEQ and MADRS and state anxiety scores; peak MEQ and SSI scores), and vice versa (average EBI and trait anxiety scores; peak EBI and BDI scores). At both 4 and 8 weeks, all relationships between peak and average MEQ or EBI scores and symptomatic changes were negative, that is, higher experience ratings correlated, at least numerically, with improvements in symptoms.

Safety and attrition

No serious adverse events were recorded during the study. One participant in the non-music group dropped out after four treatments because of intolerability of the psychoactive effects of ketamine and another in the non-music group discontinued after four treatments because of the worsening of their mental state. Two other participants in the music group presented to the emergency room for increased suicidal ideation during the course of treatment; one resumed treatment per protocol and one was excluded from further infusions for violation of the study requirement of not driving within 24 h of ketamine infusions. Neither were admitted to hospital. The most common adverse effects were transient anxiety, fatigue and nausea. Adverse events are detailed in Supplementary sTable 4 and sTable 5.

Discussion

This article presents the therapeutic and experiential outcomes of the MUSIK trial, which administered 181 ketamine infusions to 32 participants with severely refractory depression, randomised to a music or a matched non-music form of the Montreal Model of ketamine–psychotherapy. To our knowledge, this study represents the first RCT evaluating a psychedelic ketamine model for depression.

The music and non-music groups did not differ significantly on the primary therapeutic outcome (MADRS). Although music improved ketamine’s haemodynamic tolerability, as per the trial’s primary outcome, Reference Greenway, Garel, Dinh-Williams, Beaulieu, Turecki and Rej13 both groups experienced similar therapeutic effects overall. Medium-large improvements (i.e. effect sizes ranging from 0.4 to 1.2) from baseline to weeks 4 and 8 were observed for depression, anxiety and suicidality, with the caveat that improvements in suicidality did not survive a stringent multiple comparison correction, nor did anxiety improvements at 8-week follow-up. These results support the potential efficacy of the Montreal Model of ketamine–psychotherapy, Reference Garel, Drury, Thibault Lévesque, Goyette, Lehmann and Looper5 with and without music, in a population characterised by a rare level of comorbidity, active suicidality and treatment resistance.

A notable finding is that the substantial reductions in depressive symptoms observed at 4 weeks (mean MADRS decrease of 11.8 points; d = 1.2, p < 0.001) were fully maintained at 8-week follow-up (mean MADRS decrease of 11.7 points; d = 1.2, p < 0.001). Likewise for self-reported depression, suicidality and anxiety, the benefits at the treatment’s end were maintained to 8-week follow-up. These findings contrast with the typical transience of ketamine’s antidepressant effects in TRD, which generally fade significantly within days of the last infusion. Reference Dean, Hurducas, Hawton, Spyridi, Cowen and Hollingsworth32,Reference Anand, Mathew, Sanacora, Murrough, Goes and Altinay33 The durability of the benefits in the MUSIK trial may well reflect the Montreal Model’s non-pharmacological components, including concomitant psychotherapy and/or the psychedelic-like treatment contexts intended to facilitate psychologically beneficial ketamine experiences.

Indeed, emotional breakthrough experiences and especially mystical-like experiences were associated with clinical benefits across multiple converging analyses. Scores on the MEQ and EBI scales were of a comparable magnitude to those observed in trials of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy, Reference Roseman, Haijen, Idialu-Ikato, Kaelen, Watts and Carhart-Harris25,Reference Griffiths, Johnson, Carducci, Umbricht, Richards and Richards34–Reference Johnson, Garcia-Romeu, Cosimano and Griffiths36 despite the significant pharmacological differences between ketamine and psilocybin. Whole-group linear regressions found consistently positive associations between symptomatic improvements and scores on the EBI and especially the MEQ, many of which reached statistical significance. Peak MEQ scores accounted for 40–70% of the variance in symptomatic changes from baseline to week 4 for depression (p < 0.001), anxiety (p < 0.001) and suicidality (p = 0.039).

In addition, the study’s six treatment timepoints permitted session-by-session analyses of potential mechanistic relationships between mystical or emotional psychedelic experiences and antidepressant effects, that is, time-lagged MLM analyses of a given treatment’s within-person standardised MEQ or EBI scores and subsequent improvements in depression, and vice versa. In these models, the EBI was positively associated with subsequent improvements in depression but only when neglecting the confounding effects of treatment number. Indeed, EBI scores significantly increased over the treatment process and were associated with improving MADRS scores bidirectionally, arguing against a causal relationship between emotional breakthrough experiences and antidepressant effects in this study.

In contrast, we found consistent mechanistic support for antidepressant effects of mystical experiences across all analyses. Cross-lagged MLM models demonstrated a unidirectional, within-person relationship between higher-than-usual MEQ scores and larger subsequent decreases in depressive symptoms by the next session, even controlling for accumulating treatment effects (p = 0.004–0.015). Greater improvements in depression did not lead to more mystical-like ketamine experiences.

These findings add new support for the potential benefits of treatment-induced mystical experiences, extending the simpler correlational analyses across the one or two timepoints of modern psilocybin studies. Reference Davis, Barrett, May, Cosimano, Sepeda and Johnson10,Reference Garcia-Romeu, Davis, Erowid, Erowid, Griffiths and Johnson11,Reference Barrett, Johnson and Griffiths24,Reference Bogenschutz, Ross, Bhatt, Baron, Forcehimes and Laska27,Reference Barrett and Griffiths37 They also add to the body of literature examining how ketamine experiences influence its psychiatric benefits. Ketamine is known as a dissociative anaesthetic and most psychiatric studies characterise its psychoactive effects with the Clinician Administered Dissociation States Scale (CADSS). Reference Bremner, Krystal, Putnam, Southwick, Marmar and Charney38 Ketamine-induced dissociative effects, as measured by the CADSS, are not consistently associated with antidepressant effects. Reference Ballard and Zarate39 In contrast, a recent study assessing feelings of ‘awe’ during ketamine treatments found evidence for a mediating relationship between antidepressant effects and awe, but not dissociation. Reference Aepfelbacher, Panny and Price40 Alongside the current study, these findings highlight the complexity of ketamine’s subjective effects and important therapeutic ramifications of how they are conceptualised. The more predictive lenses of awe and mysticism differ from dissociation in that they have more positive connotations and have both been linked to well-being outside of drug studies. Reference Barrett and Griffiths37,Reference Keltner and Haidt41

Beyond questions of conceptualisation and measurement, ketamine’s perceptual effects may also differ significantly between studies depending on their extra-pharmacological contexts. MUSIK trial participants were randomised to receive music or matched non-music psychological support, but all received their ketamine treatments in a highly supportive context intended to facilitate therapeutic experiences. As per the concept of ‘set and setting’, a central tenet of psychedelic therapy, Reference Garel, Thibault Lévesque, Sandra, Lessard-Wajcer, Solomonova and Lifshitz42 the psychedelic-like ketamine experiences observed frequently in both arms of this study may reflect complex interactions between drug actions and contextual factors, rather than being a product of either alone. Similar degrees of mystical or emotional experiences may not be observed when ketamine is administered in less supportive contexts.

Limitations

Despite the promising findings, some important limitations should be acknowledged. The trial was powered to test the hypothesis that music can blunt ketamine-induced increases in systolic blood pressure. Reference Greenway, Garel, Dinh-Williams, Beaulieu, Turecki and Rej13 Greater sample sizes may be needed to better characterise the differential effects of music compared to matched, non-music forms of support on symptoms of depression, anxiety and suicidality. In addition, despite the blinding of MADRS assessors, the study’s open label design is a possible source of bias. Also, the multifaceted nature of the Montreal Model precludes isolation of the specific therapeutic effects of its various components and contextual elements.

Implications

The relatively sustained therapeutic benefits observed in the MUSIK trial, and the evidence for a mechanistic role of psychedelic-like ketamine experiences, have significant potential implications. They suggest that the psychiatric benefits of relatively standard course of six subanaesthetic intravenous infusions of ketamine for depression may be prolonged by psychedelic-like treatment contexts and/or concomitant psychotherapy.

Our results suggest that ketamine warrants serious consideration as a putative psychedelic, even at the relatively low dosages commonly employed in psychiatric studies, and can be potentially employed in highly severe TRD populations. The MUSIK trial found that music improved ketamine’s haemodynamic tolerability but not its therapeutic effects, Reference Greenway, Garel, Dinh-Williams, Beaulieu, Turecki and Rej13 compared to a matched form of support. Although music is an almost universal component of psychedelic therapies, Reference Kaelen, Giribaldi, Raine, Evans, Timmerman and Rodriguez18 non-music forms of support may thus offer comparable or distinct psychiatric benefits in psychedelic therapies. In the context of rapidly evolving clinical, societal and ethical landscapes, our results call for further research to better characterise how non-pharmacological factors shape drug experiences and how they may potentially be leveraged to optimise the effects of ketamine and other psychedelic interventions in depression.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2025.102

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, K.T.G. The data are not publicly available so as to protect the privacy of research participants.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Nathalie Goyette, RN, for providing excellent care to the participants of this study and to the Jewish General Hospital pharmacy for their support.

Author contributions

K.T.G., N.G. and S.R.-D. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. K.T.G. and N.G. (co–first authors) contributed equally to this manuscript. Concept and design: K.T.G., N.G., S.R., S.R.-D. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: K.T.G., N.G., L.-A.L.D.-W., S.R., S.R.-D. Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: K.T.G., N.G., L.-A.L.D.-W., S.R. Obtained funding: K.T.G., N.G., S.R., S.R.-D. Administrative, technical or material support: K.T.G., N.G., L.-A.L.D.-W., G.T., V.D.-B., J.T.L., S.d.l.S., K.L., S.R.-D. Supervision: K.T.G., S.R., S.R.-D.

Funding

This study was funded by the Réseau québécois sur le suicide, les troubles de l’humeur et les troubles associés (RQSHA). The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of interest

D.E. reported acting as a paid scientific advisor for Aya Biosciences, Lophora Aps, Clerkenwell Health, Mindstate Design Lab. M.K. is the founder of and a shareholder in Wavepaths, a company that studies and develops methods and tools for implementing music in therapeutic setting. S.R. reported receiving a clinician-scientist salary award from Fonds de Recherche Sante Quebec, grants from Mitacs (funding an MSc student) and is a shareholder of Aifred Health. S.R.-D. reported grants from Réseau québécois sur le suicide, les troubles de l’humeur et les troubles associés (RQSHA) during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.