Introduction

Across the globe, civic vitality has seen a sharp decline in recent years. From dwindling trust in others and growing antipathy toward individuals with different backgrounds, to a decrease in voluntary associations and prosocial behaviors such as volunteering and donating, the markers of civic health are in peril (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Klinenberg, Reference Klinenberg2018; Putnam, Reference Putnam2000; Vermeer et al., Reference Vermeer, Scheepers and Grotenhuis2016). Complicating matters, crafting and implementing policies to rejuvenate civic vitality is challenging, as it is often fundamentally voluntary.

School systems have attracted the interest of scholars and policymakers seeking to promote civic engagement, as educational spaces may develop the skills and competencies necessary for engaged citizenship (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Chen and Li2023; Dee, Reference Dee2004; Mohan, Reference Mohan1994). Highlighting the intrinsic connection between education and civic life, Barber wrote:

The literacy required to live in civil society, the competence to participate in democratic communities, the ability to think critically and act deliberately in a pluralistic world, the empathy that permits us to hear and thus accommodate others, all involve skills that must be acquired. (Barber, Reference Barber1994, p. 4)

Some school-based models of community service require students to complete a certain number of service hours before graduation. Such programs aim to foster civic understanding, engagement, and citizenship among all students, “including those least likely to participate voluntarily but most likely to benefit from the experience” (Andersen, Reference Andersen1999, p. 3).

Existing research on the impact of mandatory service or volunteering has yielded mixed results. While some studies demonstrate that mandatory volunteering leads to positive outcomes in future civic engagement like voting and volunteering (Hart et al., Reference Hart, Donnelly, Youniss and Atkins2007; Janoski et al., Reference Janoski, Musick and Wilson1998; Metz & Youniss, Reference Metz and Youniss2005), others suggest that it does not effectively foster civic attributes and engagement (Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Brown, Pancer and Ellis-Hale2007; Kim & Morgül, Reference Kim and Morgül2017). Helms (Reference Helms2013) and Yang (Reference Yang2017) are two recent studies that leveraged natural experiment settings to address this question. Using the cases of Maryland and Ontario, respectively, and employing a difference-in-differences design, both studies reported that mandatory community service did not lead to long-term volunteer participation.

Such inconsistent findings may stem from methodological issues. For example, research that simply compares individuals with or without mandatory community service experience may be subject to selection bias, as schools and districts offering mandatory service programs may also possess other resources to cultivate civic attributes (Putnam, Reference Putnam2015). Furthermore, the estimated effects of mandated service may actually reflect variations in program quality. While some students may participate in well-designed service programs that yield positive and lasting impressions, others may participate in poorly designed ones, which may discourage future volunteerism (Gallant et al., Reference Gallant, Smale and Arai2010; Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Pancer and Brown2014).

Relying on student samples can also be problematic. Many existing studies rely on survey data from current students only, even as such programs are expected to have long-term effects (Hart et al., Reference Hart, Donnelly, Youniss and Atkins2007; Henderson et al., Reference Henderson, Brown, Pancer and Ellis-Hale2007; Metz & Youniss, Reference Metz and Youniss2005). If the policy indeed has long-term effects as intended, these studies may underestimate the long-term impact of mandatory community service. The literature also highlights potential inconsistencies and contradictions when using student samples, thereby posing challenges to external validity, especially when extrapolating outcomes to the general public (Hanel & Vione, Reference Hanel and Vione2016). Finally, participant heterogeneity should be considered when evaluating service requirement policies, as it can have disparate effects on different populations. A national study of mandatory service would likely mitigate many of these methodological limitations.

In 1995, South Korea introduced a mandatory community service exogenously for all middle and high school students. This nationwide service requirement provides a unique context to aid in the causal inference of the effects of mandatory volunteer requirements. Using large-scale, nationally representative survey data on Korean adults affected and unaffected by the policy, this paper explores the impact of mandatory community service on civic engagement in adulthood. By analyzing the impact of this policy, we seek to address the methodological challenges identified in previous studies and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the long-term effects of mandatory community service on adult civic engagement. In so doing, we contribute to the ongoing and unresolved debate on the role of education and school systems in promoting civic engagement.

Theoretical Background

Critics of mandatory service requirements argue that using coercive tactics to elicit civic engagement can be ineffective and even detrimental in the long term. By contrast, proponents argue that it serves as a catalyst for future civic engagement by creating voluntary habits that last over time. Various social psychology theories have been invoked to support both views.

Some opponents of mandatory community service programs base deploy self-perception theory (Bem, Reference Bem1972), positing that people infer their attitudes based on the presence or absence of constraints in a given situation. For example, if one participates in an activity without apparent external constraints, it is reasonable to assume that their behavior is driven by intrinsic interest rather than external motivation. Thus, mandatory community service may undermine students’ intrinsic motivations and may even lead to civic apathy. Research in social psychology suggests that “the presence of external reasons to participate in the activity gives too much justification and results in a discounting of the initial intrinsic drive” (Sobus, Reference Sobus1995, p. 161).

Conversely, other studies on intrinsic motivation have demonstrated that reinforcement effected through external means can contribute positively to acquisition of new behaviors (Bandura & Perloff, Reference Bandura and Perloff1967; Feehan & Enzle, Reference Feehan and Enzle1991). Put differently, if students had no (or low) prior experiences participating in such activities, a school requirement would not deteriorate their pre-held internal motivation. For these students, the mandatory service requirement might provide a novel opportunity that encourages volunteering, “because they are routinely placed in social situations and social relationships where the social skills and dispositions requisite for volunteer work are developed” (Janoski et al., Reference Janoski, Musick and Wilson1998, p. 498). For example, students who are required to take music classes may develop musical skills and will play instruments and attend concerts as adults. Similarly, mandatory community service programs would affect students who are not likely to be exposed to community service elsewhere. This includes children from families lacking sufficient resources to provide civic engagement opportunities; or whose parents do not have the relevant experience and knowledge (Putnam, Reference Putnam2015). This suggests varying impact among different student groups, contingent on their respective levels of volunteer experience. Furthermore, the adverse effects of mandatory community service on young people may be overstated, as “adolescents are accustomed to requirements and regulations, especially in their school environment, and consequently are able to benefit from many required activities (e.g., adolescents learn algebra even though they are required to attend math classes)” (Van Goethem et al., Reference Van Goethem, Van Hoof, Orobio de Castro, Van Aken and Hart2014, 2118).

Meanwhile, deciphering the mosaic of students’ experience and knowledge in civic engagement before encountering required service is more taxing than one would anticipate. Researchers are rarely privy to detailed characteristics concerning individual levels of civic-mindedness; and even when such data are accessible, it tends to be categorized in restrictive, dichotomous or ordinal scales, limiting considerably the options for a rigorous empirical estimation.

An effective alternative for gauging prior experiences and knowledge is considering student’s socioeconomic background. Numerous studies have corroborated that civic engagement and volunteering tendencies are socially stratified, establishing socioeconomic status as one of the most potent predictors of volunteerism (Musick & Willson, Reference Musick and Willson2008; Smith, Reference Smith1994). While various demographic attributes can be linked with civic engagement, higher socioeconomic status is consistently associated with increased civic engagement (Chambré, Reference Chambré2020; Cnaan et al., Reference Cnaan, Handy, Marrese, Choi and Ferris2022; Musick & Willson, Reference Musick and Willson2008; Putnam, Reference Putnam2015; Smith, Reference Smith1994). This provides a solid foundation for researchers to use socioeconomic background as an effective indicator of students’ initial levels of civic engagement.

In summary, varying expectations regarding the outcomes of mandatory community service requirements arise from different psychological theories. Assuming that both theoretical approaches provide valid insights into the psychological implications of the policy, the question becomes an empirical one. As previous psychological studies indicate, mandated requirements can have divergent effects on different groups’ motivation and later participation; these effects depend on individuals’ prior experiences and knowledge. The mandatory aspect may adversely affect those with high initial engagement, while proving advantageous to those who lack it. However, since the target population comprises adolescents who are well-accustomed to mandatory activities, the negative effects may be mild or absent. Aligning with prior literature on civic engagement, we employ socioeconomic status instead of baseline level of civic engagement. For the broader population, if the policy’s benefits outweigh its drawbacks, its implementation was worthwhile.

Hypothesis 1: For the overall population, mandatory community service will increase the likelihood of student civic engagement in adulthood.

Hypothesis 2a: For the lower socioeconomic group, mandatory community service will increase the likelihood of student civic engagement in adulthood.

Hypothesis 2b: For the higher socioeconomic group, mandatory community service will decrease the likelihood of student civic engagement in adulthood.

Methods

Institutional Background

In 1995, the Korean government decided to include mandatory volunteering requirements for all middle and high school students as part of a national educational reform initiated by President Kim Youngsam. The following year, the Korean Ministry of Education implemented a guideline stating that students should complete 20 hours of community service annually. Substantial institutional resources were allocated in response to President Kim’s strong push for the reform. The Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism established Korean Centers for Adolescent Volunteering in every province to coordinate the student volunteer experience, contributing to the development and provision of systematic programs at the national level. Additionally, with support from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, the Korean Association of Social Welfare prepared a country-wide network for administrative data and program development. Despite a lack of adolescent volunteerism prior to the reform, the novel policy intervention was implemented in a relatively short period due to this strong initiative driven by the then president. Within a year, each Korean middle and upper school implemented the new policy.

Due to the requirement for students to present proof of their community service to schools, activities predominantly assumed a formal volunteering nature. This necessity directed students toward entities capable of providing such verification, including non-profit organizations, community welfare centers, hospitals, and nursing homes (Kim, Reference Kim1997). Although comprehensive national statistics on youth participation in volunteer and community service activities during this period in Korea are scarce, Kim and Jeong (Reference Kim and Jeong2000) indicate that approximately 87.1% of adolescents (including those not attending school) were involved in such activities by 2000. Considering the youth volunteer participation rate was reported as low as 13.6% before the policy's implementation (Kim, Reference Kim2004), this policy evidently played a significant role in enhancing mandatory volunteerism among the youth. The issues of policy fidelity and compliance will be examined further later in the discussion section.

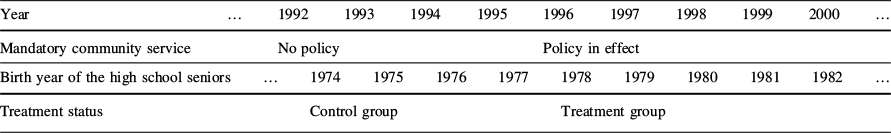

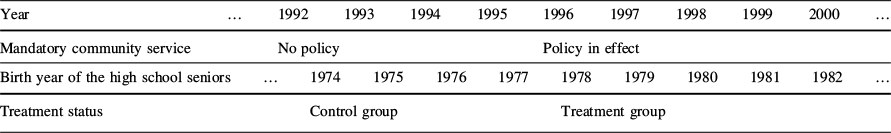

Overall, the case of South Korea represents a unique and advantageous historical context that can address the analytical challenges of estimating the effects of mandatory community service. The mandatory service policy has been effective in Korean middle and high schools since 1996. Thus, it applied to individuals born after 1977 as shown in Table 1. Students born in 1978, who were in their third year in high schools in 1996, were likely the first class required to fulfill the service requirement.

Table 1 Mandatory community service in Korea

Year |

… |

1992 |

1993 |

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000 |

… |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mandatory community service |

No policy |

Policy in effect |

|||||||||

Birth year of the high school seniors |

… |

1974 |

1975 |

1976 |

1977 |

1978 |

1979 |

1980 |

1981 |

1982 |

… |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Treatment status |

Control group |

Treatment group |

|||||||||

The dramatic change and availability of large-scale public data provide favorable conditions for estimating effects of the mandatory community service program and address the four methodological issues listed earlier. First, selection bias was a concern with existing research. Meyer and colleagues (Reference Meyer, Neumayr and Rameder2019) showed that student participants in university-based service programs differed significantly from non-participants, indicating the existence of strong self-selection. In Korea, the mandatory community service was a nationwide policy intervention exogenously implemented, independent of individual student characteristics or choices. In other words, since the policy applied to all students, individuals had no opportunity for self-selecting their behaviors, significantly reducing the risk of selection bias. In addition, regional variance in resources for civic engagement and the heterogeneity of family backgrounds cannot affect an individual’s probability of being included in the treatment group as all of Korea schools were affected by the new policy. Second, issues arising from the variability in community service programs across different schools were less concerning. Our study evaluated the outcomes before and after implementation, encompassing students from schools offering programs of varying quality. Additionally, due to the expedited deployment of the policy, the nascent stages of community service programs predominantly adhered to the government agency’s guidelines, resulting in limited variations across schools. Third, using Korean Social Survey data allows us to observe the adult outcomes of the policy, whereas existing literature examines prosocial behaviors while students are still in schools or universities. Finally, we can use individual characteristics in the data to investigate the heterogeneity of the policy’s effects for different subpopulations.

Data and Sample

The Korean Social Survey is a nationally representative survey conducted by the national agency of Statistics Korea every year. Among the ten social areas investigated, five areas are asked biannually. For statistical analysis, we use 2019 Korean Social Survey data, as the data were not impacted by the distress of COVID-19. Responses were collected by trained interviewers between May 15 and May 30, 2019. The sampling frame followed that of the Korean Census and two-stage cluster sampling was utilized, considering factors such as administrative district, age, education, and household number. Individuals who were age 13 or over from 18,576 sample households were targeted and 36,310 individuals responded in total. The interviewers asked respondents whether they had participated in volunteering (formal or informal) or donation (cash or in-kind) in the past year (May 15, 2018–May 14, 2019) respectively.

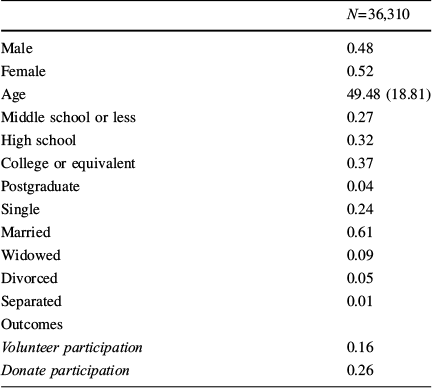

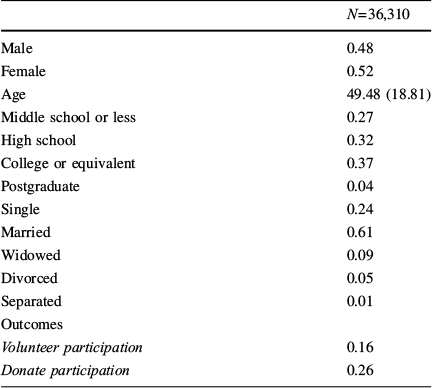

In Table 2, we show a demographic breakdown of participant characteristics.Footnote 1 Approximately 52% of participants were female, with an average age of 49. Educational attainment varied among respondents; roughly a quarter (27%) completed middle school or a lower level of education, while over 40% achieved a college degree or higher. Notably, the volunteer participation rate was 16.1%, continuing a consistent decline from 19.9% in 2013, 18.2% in 2015, and 17.8% in 2017, as observed in previous iterations of the same survey. This trend reflects the broader decline in civic health observed in many Western countries.Footnote 2

Table 2 Demographic characteristics and educational attainment of the sample

N = 36,310 |

|

|---|---|

Male |

0.48 |

Female |

0.52 |

Age |

49.48 (18.81) |

Middle school or less |

0.27 |

High school |

0.32 |

College or equivalent |

0.37 |

Postgraduate |

0.04 |

Single |

0.24 |

Married |

0.61 |

Widowed |

0.09 |

Divorced |

0.05 |

Separated |

0.01 |

Outcomes |

|

Volunteer participation |

0.16 |

Donate participation |

0.26 |

A quarter of respondents engaged in some form of donation. Cash donations were the predominant method, with about 24% of respondents indicating they had contributed monetarily. By contrast, a considerably smaller fraction, approximately 4%, reported having made in-kind donations. These data suggest a discernible preference for financial contributions over material donations among survey participants.

Empirical Strategy

We employ a sharp regression-discontinuity (RD) design, using birth years as a running variable. RD design allows us to learn about causal effects in settings where those above a known cutoff are identified as a treated group, while the rest are identified as a control group. As Abadie and Cattaneo (Reference Abadie and Cattaneo2018, p. 492) noted, the “key idea underlying any RD design is that units near the cutoff are comparable”; hence, we can estimate the local average treatment effect of the policy. Because nationwide mandatory service requirement in Korea was effective for those born in 1977, the birth year of 1978 will be our cutoff. Based on the statistical framework developed by Calonico et al. (Reference Calonico, Cattaneo and Titiunik2014) and Calonico et al. (Reference Calonico, Cattaneo and Farrell2020) which suggest nonparametric approach based on continuity assumption in practicing RD analysis, we implement the following equation:

where

![]() represents the outcomes of interest of person

represents the outcomes of interest of person

![]() ,

,

![]() is the birth year (the running variable),

is the birth year (the running variable),

![]() is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the birth year of an individual is 1978 or greater (

is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the birth year of an individual is 1978 or greater (

![]() ) and 0 otherwise (

) and 0 otherwise (

![]() ), and

), and

![]() is a region fixed effects of 17 provinces in Korea. We apply triangular weighting kernel and use mean square error (MSE) optimal bandwidth which is symmetric around the cutoff. Heteroskedasticity robust nearest neighbor standard errors are used. In analyzing the binary outcomes of whether respondents participated in volunteering and donation, we adopt linear probability model to estimate how the policy affected the probability of participation.

is a region fixed effects of 17 provinces in Korea. We apply triangular weighting kernel and use mean square error (MSE) optimal bandwidth which is symmetric around the cutoff. Heteroskedasticity robust nearest neighbor standard errors are used. In analyzing the binary outcomes of whether respondents participated in volunteering and donation, we adopt linear probability model to estimate how the policy affected the probability of participation.

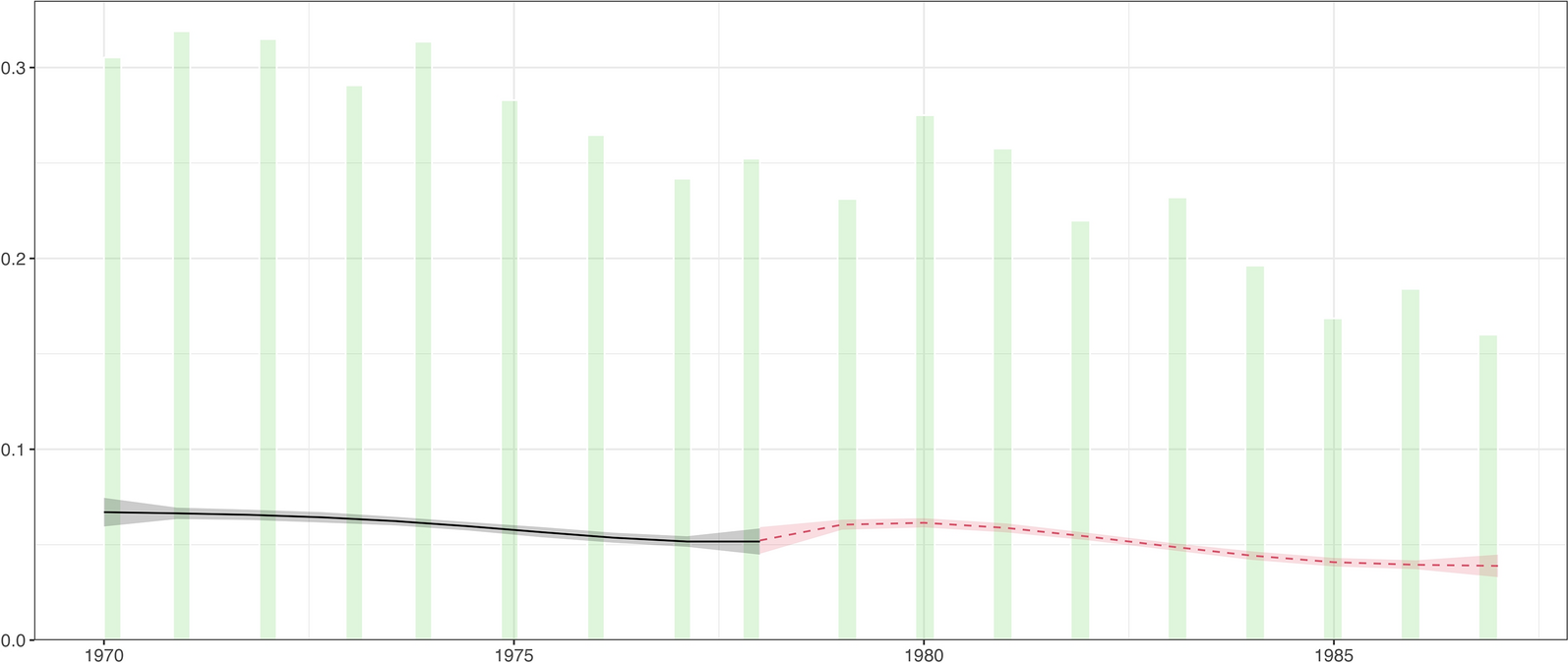

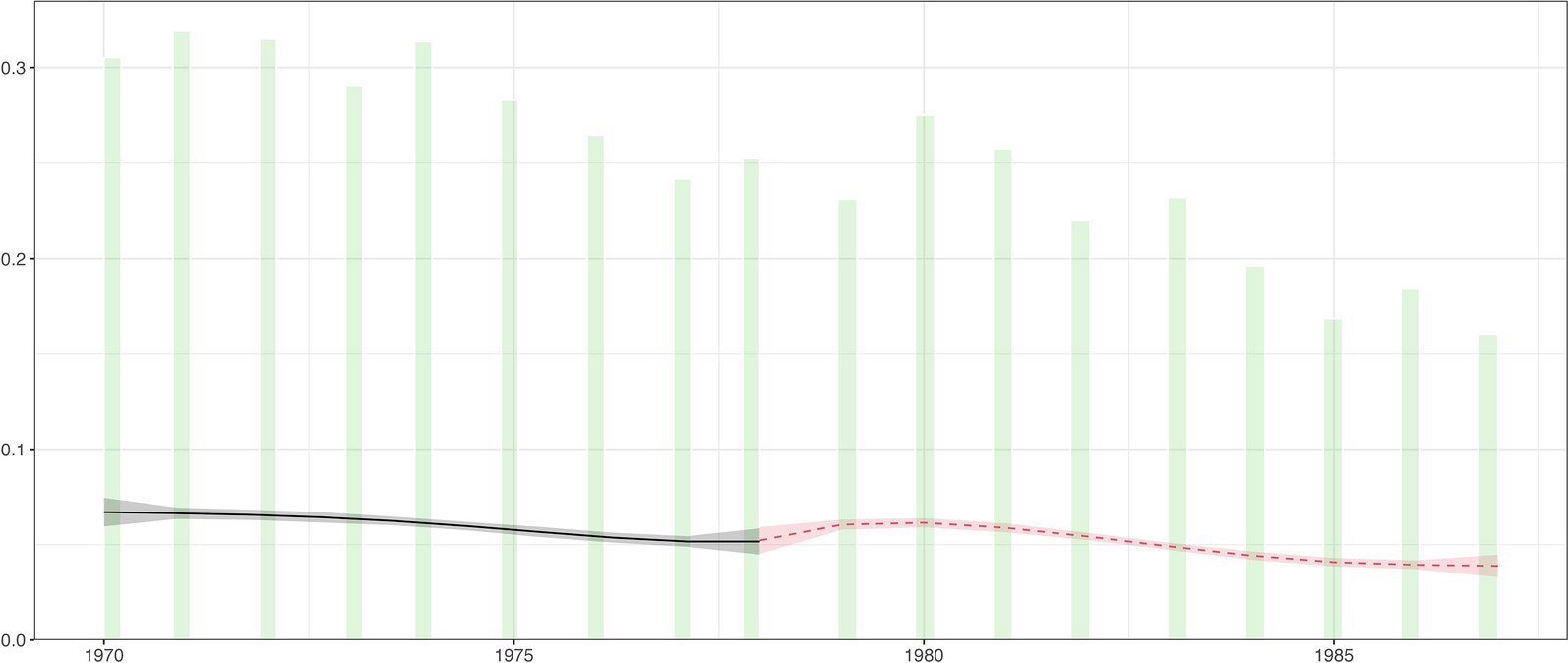

In line with other literature employing the RD design (Burlig & Preonas, Reference Burlig and Preonas2016), a central assumption in our analysis is that individuals cannot systematically manipulate their scores or values around the cutoff. If those near the cutoff could influence their scores, thereby affecting their treatment status, the RD estimate—represented by the difference between the two linear regression lines on either side of the cutoff—would not denote the causal effect of the treatment. However, given that those close to the cutoff had already commenced schooling by the time the mandatory community service policy was introduced, and our running variable is birth year, such manipulation is unlikely to threaten our analysis. This is further illustrated in Fig. 1, where we plot the estimated density in order to check the validity of the RD design. The proximity of the density estimates for both the control and treatment groups around the cutoff point (= 1978) further attests to this. For a more formal statistical substantiation, we performed a test on the null hypothesis that our running variable remains unmanipulated (i.e., continuous) around the cutoff as suggested in Cattaneo et al. (Reference Cattaneo, Jansson and Ma2020). The test could not reject the null hypothesis (p-val = 0.15), underscoring the validity of the continuity assumption in our study.

Fig. 1 Density plot for RD analysis. Note: The solid line depicts the local quartic polynomial density estimate for the control group (those born in 1977 or earlier), while the dotted line does so for the treatment group (those born in 1978 or later). The shaded areas illustrate the robust bias-corrected 95% confidence interval (Cattaneo et al., Reference Cattaneo, Jansson and Ma2020). Bars represent histogram estimates

Finally, as discussed earlier, it is imperative to scrutinize the heterogeneity present within the various subgroups affected by the service requirement. A nuanced approach necessitates the evaluation of baseline characteristics prior to policy enactment, thereby facilitating a more accurate assessment of its effects across differing socioeconomic strata. However, due to the absence of data pertaining to individual characteristics from the time respondents were in middle or high school, this study utilizes their current socioeconomic statuses as a proxy for initial conditions. It is critical to acknowledge that this approach may introduce certain limitations in capturing the precise variations in the initial socioeconomic variables. We aim to delineate the disparate impacts of the policy, emphasizing the potential variations in effects among individuals hailing from higher and lower socioeconomic backgrounds. As education is one of the most frequently used indicators of socioeconomic status (Galobardes et al., Reference Galobardes, Shaw, Lawlor, Lynch and Smith2006), we categorize the lower socioeconomic group as individuals who have achieved a high school diploma or less; whereas the higher socioeconomic group encompasses individuals who have attained a college degree or higher. We additionally conducted the same density discontinuity tests for the two subgroups and found that the continuity assumption holds for the subgroups as well (See Supplementary Fig. 1).

Results

Aggregate Effect for the Total Sample

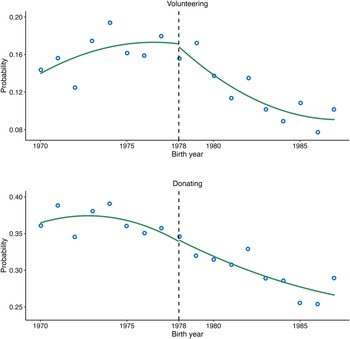

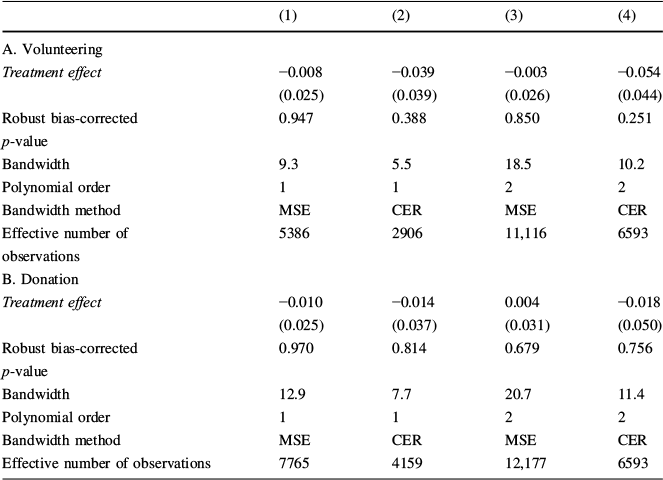

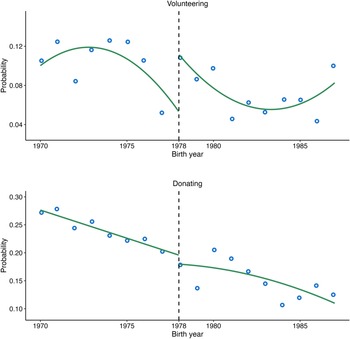

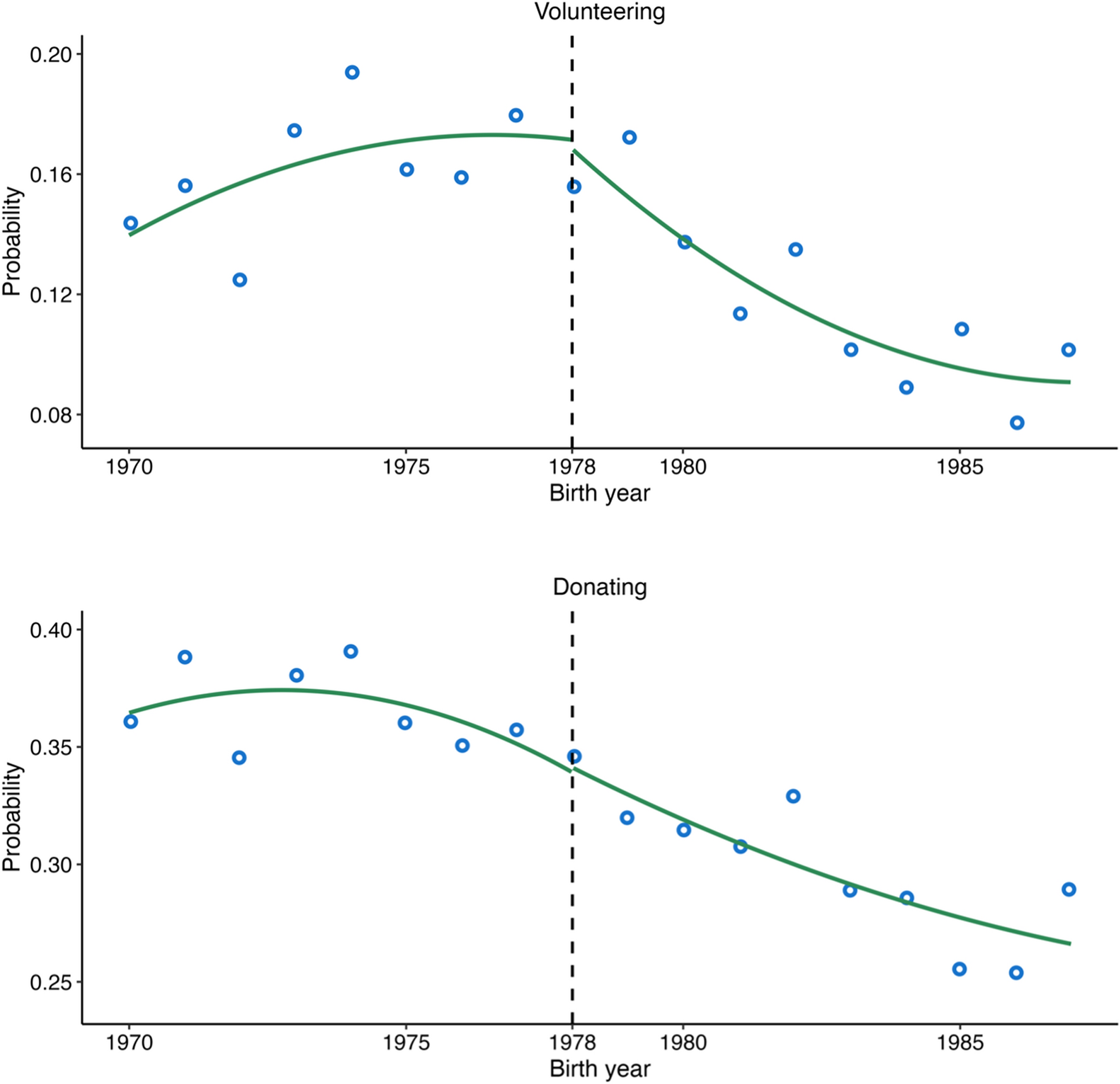

We first examined whether the mandatory community service requirement influenced the volunteering and donating behaviors across our entire sample, without accounting for the heterogeneity of the policy effect. One advantage of the RD framework is its ability to be both visually illustrated and formally estimated. In Fig. 2, we visually demonstrate the potential discontinuity by contrasting the behaviors of individuals affected by the policy against those who were not. This is achieved by fitting a quadratic polynomial line to each side of the cutoff point. The y axes in the two graphs each represent the likelihood of participation in volunteering and donation, respectively, for each birth cohort.

Fig. 2 RD plot for the total sample. Note: Quadratic polynomial line is fitted and uniform kernel function is used to weight observations. The sample size is 10,393

Given that using all raw data points can often clutter the visualization, even when the effect size is large, we employ a binned approach to better represent the distribution. For weighting, a uniform kernel is applied (Cattaneo et al., Reference Cattaneo, Idrobo and Titiunik2019). With respect to both volunteering and donation, findings reveal no evident discontinuity in RD plots for the entire sample. In other words, no sign of policy effect is observed from the RD plots.

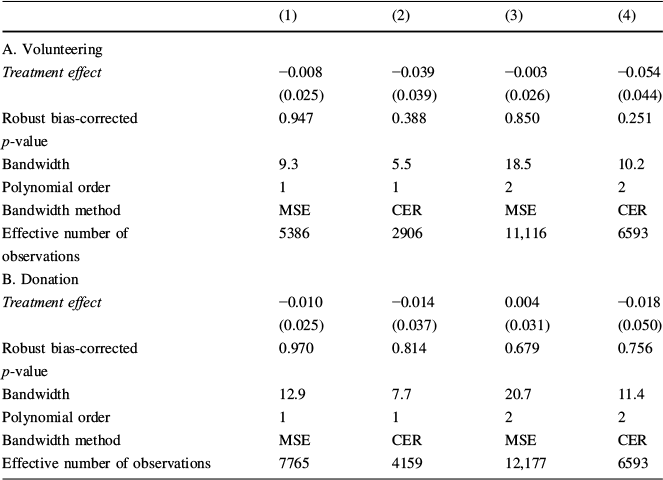

As shown in Table 3, results from the local non-parametric regression analysis align with our inferences drawn from the visual data. In columns 1 and 2, the polynomial order is set to 1; it is set to 2 in columns 3 and 4. Given the importance of selecting an appropriate bandwidth in the nonparametric RD design, we utilize the bandwidth that optimizes the mean square error (MSE), a choice known to be optimal for point estimation purposes (Cattaneo et al., Reference Cattaneo, Idrobo and Titiunik2019). Yet, recognizing that different bandwidth choices might yield varying outcomes, we also opted for another bandwidth minimizing an approximation to the coverage error rate (CER), as indicated by Calonico et al. (Reference Calonico, Cattaneo and Farrell2020).

Table 3 Impact on the total sample

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

A. Volunteering |

||||

Treatment effect |

−0.008 |

−0.039 |

−0.003 |

−0.054 |

(0.025) |

(0.039) |

(0.026) |

(0.044) |

|

Robust bias-corrected p-value |

0.947 |

0.388 |

0.850 |

0.251 |

Bandwidth |

9.3 |

5.5 |

18.5 |

10.2 |

Polynomial order |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

Bandwidth method |

MSE |

CER |

MSE |

CER |

Effective number of observations |

5386 |

2906 |

11,116 |

6593 |

B. Donation |

||||

Treatment effect |

−0.010 |

−0.014 |

0.004 |

−0.018 |

(0.025) |

(0.037) |

(0.031) |

(0.050) |

|

Robust bias-corrected p-value |

0.970 |

0.814 |

0.679 |

0.756 |

Bandwidth |

12.9 |

7.7 |

20.7 |

11.4 |

Polynomial order |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

Bandwidth method |

MSE |

CER |

MSE |

CER |

Effective number of observations |

7765 |

4159 |

12,177 |

6593 |

A triangular kernel function is applied across all estimations. For columns 1 and 3, the bandwidth is optimized for mean square error, while in columns 2 and 4, it minimizes an approximation to the coverage error of the confidence interval. Columns 1 and 2 utilize linear polynomial approximation, whereas columns 3 and 4 employ quadratic polynomial approximation. The standard errors are estimated using 3 nearest-neighbors. For statistical inference, we apply bias correction to reduce coverage error, and rescale confidence intervals using a larger standard error than conventionally used (Cattaneo et al., Reference Cattaneo, Idrobo and Titiunik2019). Standard error in parentheses. *p < 0.1 **p < 0.05 ***p < 0.01

Our most preferred specification is displayed in Column 1. The formal estimation also indicates that there is no substantive evidence to suggest that the mandatory community service had any significant impact on volunteering and donation behaviors in adulthood for the entire sample.

Results for the Lower Socioeconomic Group

As previously noted, the implications of mandatory community service requirements can vary for students based on prior knowledge and experiences participating in such activities, which can be represented by their socioeconomic background. While the policy did not demonstrate a significant effect on the general sample, we examined whether it influenced different subgroups unevenly when segmented by socioeconomic status. We classified the lower socioeconomic group as those with a final educational attainment of high school or below, and the upper socioeconomic group as those with a final educational attainment of college or above.

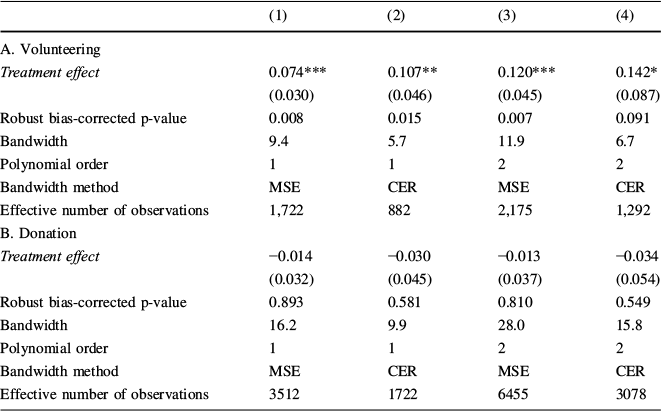

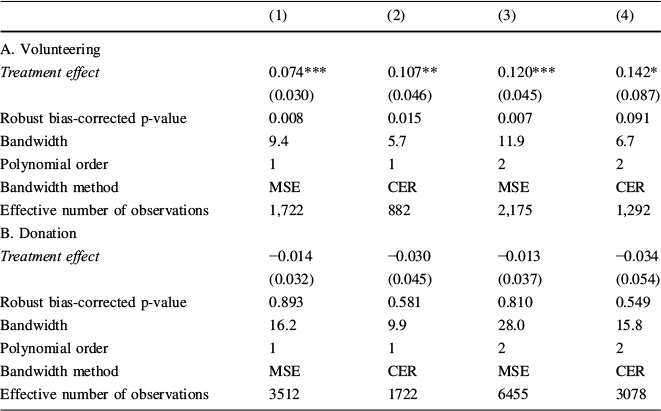

Figure 3 presents RD graphs depicting volunteering and donation trends for the lower socioeconomic group. Although the vertical disparity between the two fitted lines for donations is subtle, the gap between the fitted lines representing the volunteering likelihood for continuous cohorts is markedly apparent. Specifically, the line to the right of the cutoff illustrates a higher volunteering probability at the cutoff point. This distinct leap suggests that mandatory community service had a profoundly positive influence on the treated group.

Fig. 3 RD plots for the lower socioeconomic group. Note: Quadratic polynomial line is fitted and uniform kernel function is used to weight observations. The sample size is 3592

Table 4 conveys the statistical findings on the policy’s impact on the lower socioeconomic group. Concerning volunteering, there’s compelling evidence that mandatory community service had a favorable outcome. As detailed in column 3, the RD estimate reveals a 12% points treatment effect, statistically significant at the 1 percent level. Our preferred estimate in column 1 indicates a treatment effect of 7.4% points, which is 81.3% increase from the expected value of the control group at the cutoff point. By contrast, for donation, the policy’s effect seems negligible, as all four specifications failed to refute the null hypothesis.

Table 4 Impact on the lower socioeconomic group

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

A. Volunteering |

||||

Treatment effect |

0.074*** |

0.107** |

0.120*** |

0.142* |

(0.030) |

(0.046) |

(0.045) |

(0.087) |

|

Robust bias-corrected p-value |

0.008 |

0.015 |

0.007 |

0.091 |

Bandwidth |

9.4 |

5.7 |

11.9 |

6.7 |

Polynomial order |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

Bandwidth method |

MSE |

CER |

MSE |

CER |

Effective number of observations |

1,722 |

882 |

2,175 |

1,292 |

B. Donation |

||||

Treatment effect |

−0.014 |

−0.030 |

−0.013 |

−0.034 |

(0.032) |

(0.045) |

(0.037) |

(0.054) |

|

Robust bias-corrected p-value |

0.893 |

0.581 |

0.810 |

0.549 |

Bandwidth |

16.2 |

9.9 |

28.0 |

15.8 |

Polynomial order |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

Bandwidth method |

MSE |

CER |

MSE |

CER |

Effective number of observations |

3512 |

1722 |

6455 |

3078 |

A triangular kernel function is applied across all estimations. For columns 1 and 3, the bandwidth is optimized for mean square error, while in columns 2 and 4, it minimizes an approximation to the coverage error of the confidence interval. Columns 1 and 2 utilize linear polynomial approximation, whereas columns 3 and 4 employ quadratic polynomial approximation. The standard errors are estimated using 3 nearest-neighbors. For statistical inference, we apply bias correction to reduce coverage error, and rescale confidence intervals using a larger standard error than conventionally used (Cattaneo et al., Reference Cattaneo, Idrobo and Titiunik2019). Standard error in parentheses. *p < 0.1 **p < 0.05 ***p < 0.01

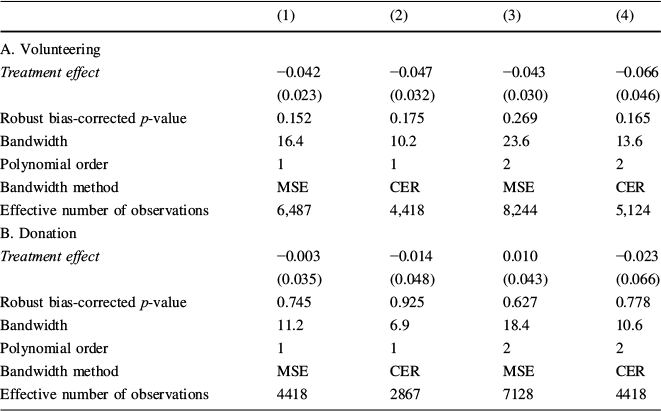

Results for the Higher Socioeconomic Group

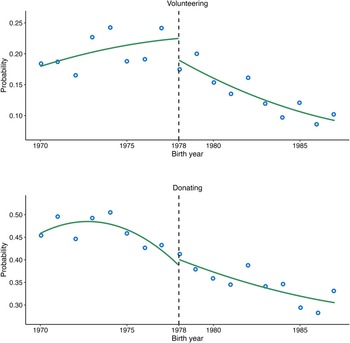

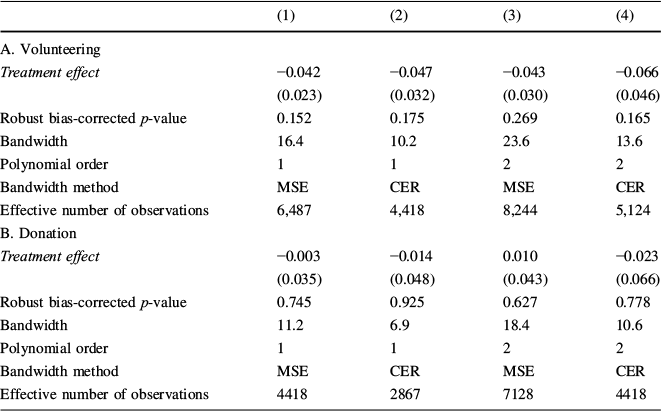

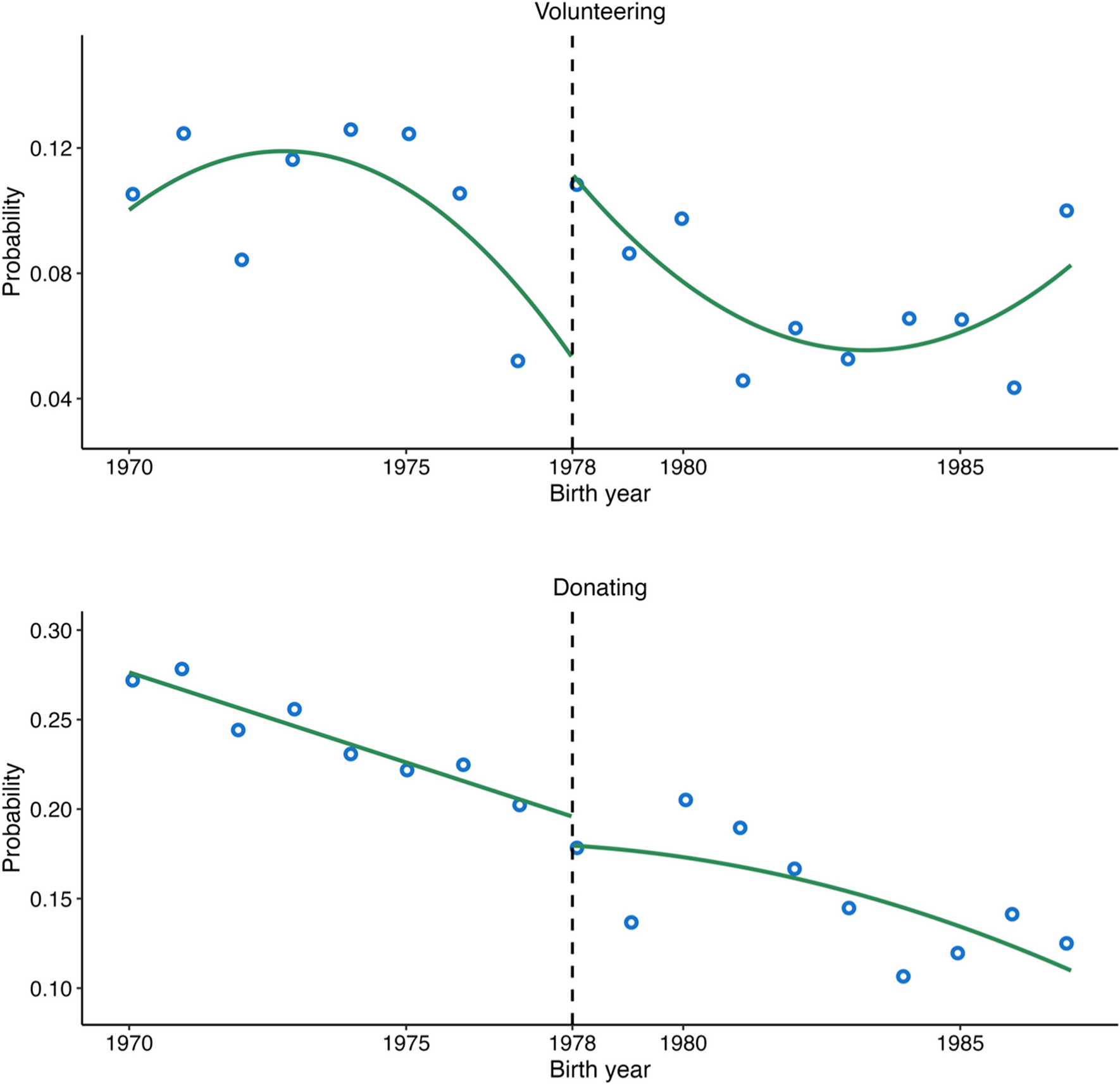

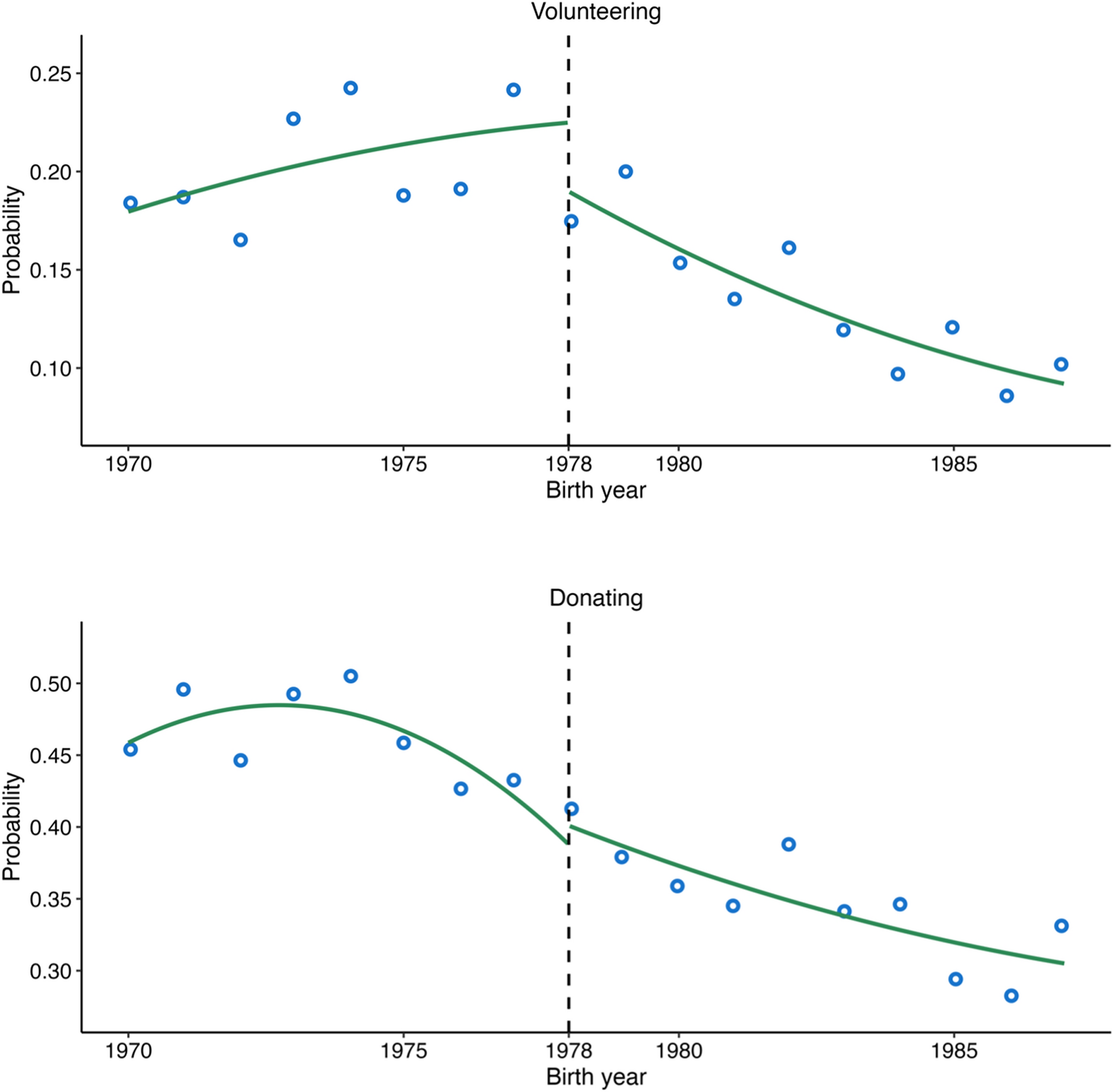

The analysis conducted on the lower socioeconomic group was similarly executed for the higher socioeconomic group. The RD graph at the top of Fig. 4 represents the volunteering probability of the higher socioeconomic group. The graph visualizes a noticeable decline at the cutoff. This contrasts with the trend observed for the lower socioeconomic group’s volunteering graph. The donation graph for the higher socioeconomic group mirrors the trends depicted in Fig. 3 for the lower socioeconomic group. Such contrasting patterns in volunteering across these subgroups align with our hypothesis that the policy may yield divergent outcomes for different populations.

Fig. 4 RD plot for the higher socioeconomic group. Note: Quadratic polynomial line is fitted and uniform kernel function is used to weight observations. The sample size is 6801

However, the results presented in Table 5 do not furnish statistical evidence to suggest that the mandatory community service policy adversely affected the higher socioeconomic group. Despite the discontinuity observed in the RD graphs, formal estimation indicates insufficient evidence to claim that the mandatory requirement led to a crowding-out effect on the civic engagement of the higher socioeconomic group. In other words, the mandatory community service requirement seems to have had no significant impact on the higher socioeconomic group in terms of both volunteering and donation.

Table 5 Impact on the higher socioeconomic group

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

A. Volunteering |

||||

Treatment effect |

−0.042 |

−0.047 |

−0.043 |

−0.066 |

(0.023) |

(0.032) |

(0.030) |

(0.046) |

|

Robust bias-corrected p-value |

0.152 |

0.175 |

0.269 |

0.165 |

Bandwidth |

16.4 |

10.2 |

23.6 |

13.6 |

Polynomial order |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

Bandwidth method |

MSE |

CER |

MSE |

CER |

Effective number of observations |

6,487 |

4,418 |

8,244 |

5,124 |

B. Donation |

||||

Treatment effect |

−0.003 |

−0.014 |

0.010 |

−0.023 |

(0.035) |

(0.048) |

(0.043) |

(0.066) |

|

Robust bias-corrected p-value |

0.745 |

0.925 |

0.627 |

0.778 |

Bandwidth |

11.2 |

6.9 |

18.4 |

10.6 |

Polynomial order |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

Bandwidth method |

MSE |

CER |

MSE |

CER |

Effective number of observations |

4418 |

2867 |

7128 |

4418 |

A triangular kernel function is applied across all estimations. For columns 1 and 3, the bandwidth is optimized for mean square error, while in columns 2 and 4, it minimizes an approximation to the coverage error of the confidence interval. Columns 1 and 2 utilize linear polynomial approximation, whereas columns 3 and 4 employ quadratic polynomial approximation. The standard errors are estimated using 3 nearest-neighbors. For statistical inference, we apply bias correction to reduce coverage error, and rescale confidence intervals using a larger standard error than conventionally used (Cattaneo et al., Reference Cattaneo, Idrobo and Titiunik2019). Standard error in parentheses. *p < 0.1 **p < 0.05 ***p < 0.01

Falsification Test on the Effect of the Policy

While the RD design is widely recognized for its ability to address causal questions, its validity and reliability remain contingent upon statistical assumptions and analytical decisions made during the study. To this end, we have illustrated the density plots and conducted statistical tests to affirm the validity of our continuity-based RD framework in the given context. Our main results remained consistent with the selection of different polynomial orders and bandwidths as shown in Tables 3, 4, and 5.

We conduct additional sensitivity tests with further variations in model specifications. In Supplementary Tables 2, 3, and 4, we employ models analogous to the one illustrated in column 1 of Tables 3, 4, and 5, with different choices in kernel function and bandwidth selection. The outcomes derived from these alternative specifications remain consistent with our primary results. Including personal characteristics such as gender, marital status, employment status, and household income did not affect the results as well, as demonstrated in Supplementary Table 5.

To further ensure the robustness of our findings, we bolster our analysis with a standard falsification test commonly used in RD studies: the placebo test. The rationale behind this test is simple. By conducting the same analysis using different, arbitrary cutoff points, we can evaluate the continuity of the regression functions at locations other than the actual cutoff value. This not only helps verify the integrity of our chosen model but also supports our claim that the observed treatment effect is not merely a coincidental outcome arising from timing nuances. As the mandatory community service showed significant effect only for the volunteering of the lower socioeconomic group, we confine our placebo test to this specific outcome.

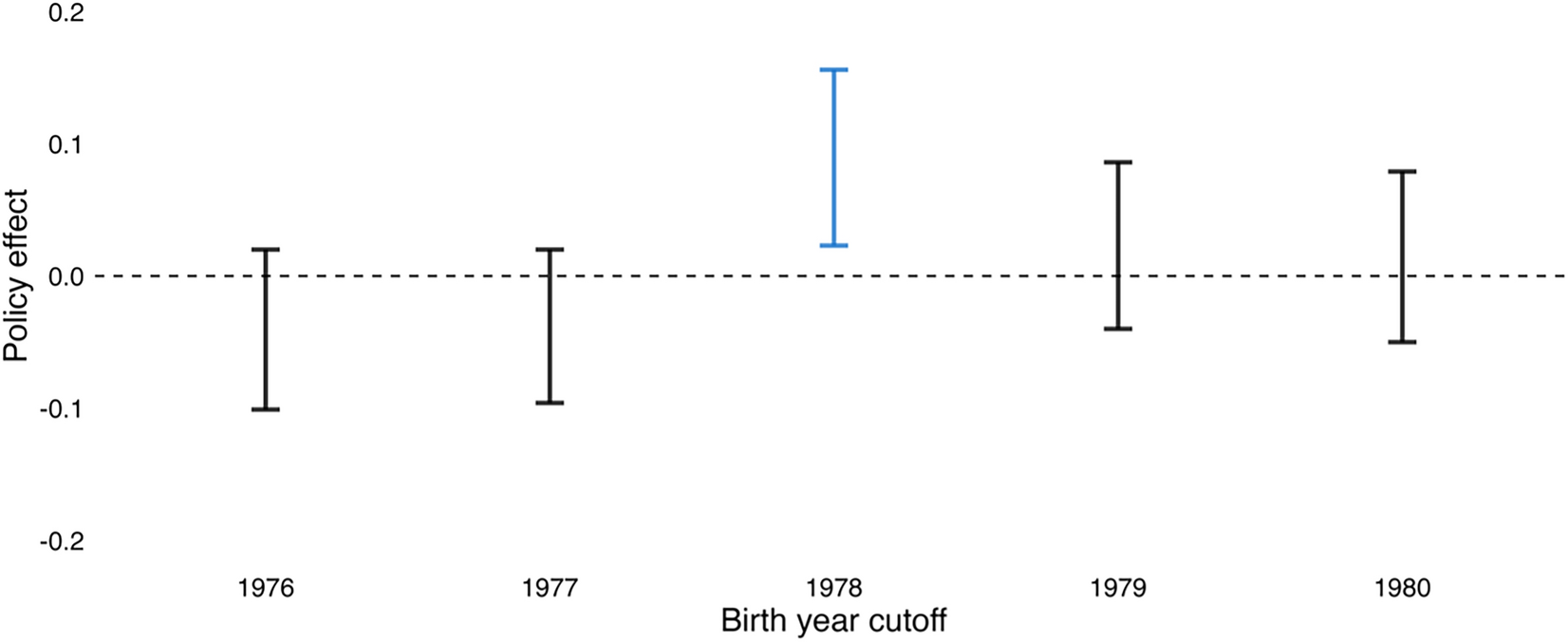

We re-executed the statistical analysis, designating cutoff points for the cohort birth years 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979, and 1980. Given that the true cutoff point is 1978, a pronounced discontinuity—attributed to the treatment effect—should solely manifest for 1978. Conversely, the other years, serving as placebo cutoffs, should not display any significant treatment effects. This is visualized in Fig. 5, wherein we delineate the 95% confidence intervals of the quintet of coefficients. Singularly, the confidence interval associated with the true cutoff year refrains from including zero, underscoring its significance. By contrast, the intervals derived from placebo cutoffs include zero, indicating an absence of a significant effect.

Fig. 5 Coefficient plot for the placebo test. Note: Error bars depict the 95% confidence intervals. The coefficient corresponding to 1978 signifies the actual treatment effect. In contrast, the coefficients for other years are derived from using arbitrary cutoff points (i.e., placebo cutoffs) in the regression-discontinuity analysis

The results from the placebo test are especially crucial as they allow us to eliminate the possibility that our findings are influenced by spurious correlations due to time trends or other societal shifts. For example, considering that participation in civic engagement is strongly linked with higher education attainment, one might speculate whether the rapid expansion of college enrollment in South Korea during the mid to late 1990s could have confounded our results. Additionally, societal shocks like the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis might have also played a role in affecting the social lives of individuals. Nonetheless, the outcomes presented in Fig. 5 suggest that the policy effect we identified is not driven by these confounding factors. If educational expansion or other social shocks were influential, we would expect to observe significant results for the years 1997 or 1998 (or the birth years of 1979 or 1980), which is not the case in our analysis.

Discussion and Conclusion

Despite a chorus of voices warning about the ebbing vitality of civic engagement worldwide, the path to restoration has remained shrouded in uncertainty. Among a scant set of potential remedies, school community service programs stand out as beacons of hope. Schools are not merely institutions of learning, but crucibles where new possibilities are forged, and social virtues nurtured. Advocates of this idea contend that by requiring community service for graduation, the transformative benefits of these programs could be extended to a wider population. However, the paradox of mandating what should be a voluntary act of civic engagement has presented a dilemma. The urgent need for empirical evidence on the effects of such policies is apparent. Yet, empirical studies have encountered critical methodological challenges, preventing consensus about the effects of mandatory community service. The case of South Korea provides a unique and valuable context for this inquiry, as the country implemented a mandatory community service policy nationwide in a short span of time. This swift implementation created a natural experimental setting for analysis. Leveraging this opportunity, we employed a quasi-experimental approach via a non-parametric regression-discontinuity design to examine the causal effect of the policy.

Our analysis began by considering the entire sample, examining the impact of mandatory community service on the likelihood of volunteering and donation behavior during adulthood. In this broad evaluation, we found no evidence of a significant policy effect on these behaviors. Subsequently, we divided our sample into subgroups based on socioeconomic status. For the lower socioeconomic group, the data showed that mandatory community service had a positive influence on volunteering behavior. Specifically, our preferred estimate indicated a 7.4% increase in the probability of volunteering during adulthood, which is an 81.3% increase from the predicted value of the control group at the cutoff. No significant effect was observed for donations among the same group. By contrast, when considering the higher socioeconomic group, a decline in volunteering probability was visible at the cutoff point in the RD graph. Nonetheless, our formal statistical estimation could not corroborate the existence of a significant impact of the policy on either volunteering or donation behaviors. Our placebo tests further strengthened our findings by confirming that the significant treatment effect for volunteering in the lower socioeconomic group was not simply an incidental occurrence due to timing discrepancies or other confounders. A pronounced discontinuity—attributable to the policy—was only observed for the true cutoff year of 1978, which validates the robustness of our conclusions.

For those from the lower socioeconomic group, mandatory community service positively influenced volunteering behaviors in adulthood. This indicates that the policy could be an effective instrument in encouraging civic engagement among individuals who might lack the opportunities and resources to participate in such activities otherwise. This suggests that mandatory community service can serve as a platform to promote engagement among those who might otherwise be excluded or overlooked—a perspective echoed in existing literature (Andersen, Reference Andersen1999; Metz & Youniss, Reference Metz and Youniss2005). In contrast, the higher socioeconomic group, with presumably higher initial baseline level of civic engagement, showed no significant policy effects on volunteering and donation behaviors. One might expect that mandatory community service could have a negative effect, undermining intrinsic motivation to volunteer or donate in future. However, we observed no such adverse effect even on the higher socioeconomic group.

We posit that this absence of a negative impact is likely due to the fact that the policy affects adolescents, a demographic for whom mandatory participation is a regular aspect of formal education. In essence, the formal educational curriculum already includes certain levels of obligatory participation, which makes mandatory community service less disruptive or unpalatable to the students involved.Footnote 3 It is also possible that school students of higher socioeconomic level are exposed at home high to the merit and commitment to volunteering and donating and their behaviors are set at that age. Lower socioeconomic students may have not socialized to volunteer and as such the mandatory community service is a novel experience that alter their future behavior. This topic warrants further scholarly inquiry, as it holds the potential to unravel the nuances of our central question.

We also acknowledge limitations of our study. First, although the case of South Korea provided greatly desirable setting in addressing the causality in this matter, the generalizability of our results should be taken with care. The conditions under which the policy was implemented can differ from other countries. For instance, the Korean policy received strong presidential support and was implemented nationwide in a short period of time. At the time, civic engagement was not as common and mature as it is now. Furthermore, results from an RD design might not be readily generalizable to a broader population that falls far from the cutoff point.

It also bears emphasizing that we employed a proxy for the socioeconomic indicator, using an adult socioeconomic variable rather than a childhood variable. Our assumption is that socioeconomic status remains relatively stable throughout an individual's life. While this approach may seem like a strong assumption, Laurison and Friedman (Reference Laurison and Friedman2024) suggests that initial socioeconomic status often establishes enduring boundaries into adulthood. Moreover, it is possible that adult socioeconomic status can serve as a more comprehensive measure, reflecting not only childhood socioeconomic conditions but also family culture, peer groups, and personal environments. Even with access to childhood socioeconomic information, its ability to accurately represent the "baseline" of students' civic engagement experiences could still be questioned. In this view, adult socioeconomic status is a product of multiple factors, making it an effective proxy for our study.

As is the case in every research examining the impact of a policy, a critical aspect to consider is the fidelity of policy implementation and the degree of student compliance with the requirements. Despite the policy's mandatory designation, as institutionalized by educational reform, expecting universal adherence may be overly optimistic. For instance, Kim and Jeong (Reference Kim and Jeong2000) provide examples where students could not or did not follow the policy due to reasons such as difficulty finding appropriate volunteer opportunities or schools not fully adhering to government guidelines. Nevertheless, the relevance of our findings remains solid in the face of these practical challenges in implementation. The strong initiative led by the then president, who wielded centralized power, coupled with the effective nationwide coordination among relevant government agencies, facilitated the swift integration of this policy into educational frameworks across the country. Furthermore, the high stakes of college admissions competition in South Korea at the time meant that not fulfilling the community service requirements should lead to significant disadvantages in the high school or college admission process, compelling students to participate. This incentive was sufficient to not only encourage individual compliance but also eventually led some schools to develop extracurricular programs, enabling students to complete part of the required hours on campus (Park & Kim, Reference Park and Kim2017). As a result, while adolescent volunteer participation was approximately 13.6% prior to the policy, it soared to 87% by 2000 (Kim, Reference Kim2004; Kim & Jeong, Reference Kim and Jeong2000).Footnote 4

More importantly, the possibility that a non-trivial number of students may have not adhered to this mandate and our reliance on a sharp RD design suggest that our findings represent conservative estimates, delineating the minimum impact of the policy. Should compliance have been higher, a more substantial positive effect of the policy could be anticipated. The lack of a discernible impact on the higher socioeconomic group might stem from their lower actual completion rates of the mandatory community service, possibly because they had more resources to navigate around the requirements while dedicating more time to exam preparation.

Future research should explore ways to amplify and sustain the positive effects of mandatory community service over the long term. Studies that enhance external validity and examine the impact of these policies on other indicators of civic vitality—such as voting, trust, and participation in voluntary associations—would further enrich the literature on this topic. Such research could illuminate the broader implications of these policies and their potential to foster genuine civic engagement across diverse populations. Finally, that delicate line between empowering students to embrace civic responsibility and simply pressing them into service deserves a deeper, more careful look.

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Pennsylvania's School of Social Policy and Practice Summer Research Fellowship, the James Joo-Jin Kim Center for Korean Studies Graduate Fellowship, and the Institute of Education Sciences under PR/Award #3505B200035.