Societal change is argued to provoke resistance or counter-reactions, often described as cultural backlash, with consequences for the rise of far-right parties (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019). For instance, perceptions of immigration and ethnic minorities as threats to individuals’ or societies’ material well-being and values have arguably triggered such counter-reactions (Jackson Reference Jackson1993; Stephan and Stephan Reference Stephan and Stephan2013). Similarly, feminist mobilizations have historically faced resistance and backlash (Blais and Dupuis-Déri Reference Blais and Dupuis-Déri2012; Chafetz and Dworkin Reference Chafetz and Dworkin1987). Yet, feminism and gender-related societal change have only recently been considered as triggers of cultural backlash and influential for far-right voting. Counter-reactions to societal change, such as the one produced by immigration, are often framed and explained in terms of threat perceptions (Schneider Reference Schneider2008; Stephan et al. Reference Stephan, Renfro, Esses, Stephan and Martin2005; Zárate et al. Reference Zárate, Garcia, Garza and Hitlan2004). Despite the potential of threat theory for understanding resistance to feminism, and despite the important implications of feminism threat perceptions for far-right voting and liberal democratic policymaking, individuals’ perceptions of feminism as a threat have not been conceptualized, measured, or explained.

To better understand resistance to feminism, in this article, we build on integrated threat theory to conceptualize and measure perceptions of feminism as a threat, and to empirically study the correlates of such threat perceptions. We focus on the case of Spain, which has recently seen important feminist mobilizations and changes in legislation, as well as a relatively strong and visible counter-reaction. In this context of strong politicization of feminism and rapid social and legislative change, we expect to find relatively pronounced perceptions of feminism as threatening, possibly explained by different factors across different population groups.

To measure perceptions of feminism as a threat, we use a novel survey measure operationalizing threat perceptions related to feminism, included in the POLAT Dataset in five consecutive waves between 2020 and 2024 (Pannico et al. Reference Pannico, Carolina, Enrique, Guillem and Eva2025). This dataset includes longitudinal data of a representative sample of the Spanish population with measures of perceptions of threat associated with different issues, including feminism. The survey battery captures whether respondents feel that feminism can harm their own or their country’s economic situation or values in the future, thereby capturing material and symbolic, as well as egotropic and sociotropic threat dimensions.

We deductively analyze factors explaining perceptions of feminism as a threat, including gender, material vulnerability, psychological predispositions to feel threatened, and political attitudes. Surprisingly, we find that women feel similarly, if not more, threatened by feminism compared to men. Using regression analysis we also find that, besides material vulnerability and political orientations, psychological predispositions are important predictors of perceptions of feminism as a threat, with significant correlations across perceived threats, even if they are of a different nature (such as climate change and feminism), e.g., people who feel threatened by climate change are also more likely to feel threatened by feminism.

Using a latent profile analysis (LPA) that identifies latent population subgroups with different combinations of psychological predispositions, political attitudes, and threat perceptions, we observe that women are overrepresented among progressives with low feminism threat perceptions, but also among the anxious profile, which shows high threat perceptions (including for feminism) without a politically distinctive profile. Conversely, men are overrepresented among the unfearful center-right profile (low threat perceptions and center-right political attitudes) and conservatives (relatively high feminism threat perceptions and right-wing political attitudes). Importantly, men’s perceptions of feminism as threatening are associated with far-right support, while women’s perceptions of feminism as threatening are not associated with a particular political profile.

Our findings have important implications for research on threat perceptions of social change beyond feminism. We argue that threat perceptions related to social change cannot necessarily be equated with socially conservative attitudes. Our paper shows that threat perceptions seem to be motivated by different factors, of which some have a political or ideological nature, and others relate to psychological predispositions to feel threatened. These factors motivating threat perceptions tend to be gendered and associated with different kinds of political orientations. We thus highlight the importance of considering both political attitudes and psychological predispositions of threat vulnerability when explaining threat perceptions of social change, be it in the form of feminism or other kinds of social change. This has implications for the feminist movement, which must overcome not only ideological but also anxiety-related challenges. This also has implications for research on other perceived social threats, as our findings suggest that perceptions of threat seem to be able to travel from one threat object to another.

The paper proceeds as follows. First, we review key literature on social threat perceptions. Next, we apply intergroup threat theory to the case of feminism. We then proceed to conceptualize feminism as a threat, and hypothesize about what explains perceptions of feminism as threatening. Thereafter, we present the case of Spain, our data, and methods, followed by the results of our analysis. The paper ends with a discussion of the implications of our findings.

The Nature and Relevance of Threat Perceptions

Integrated threat theory aims to understand the role of fear in prejudice within intergroup relations (Stephan and Stephan Reference Stephan and Stephan2000). It aims to explain how and under what conditions immigrants, ethnic minorities, or different groups are perceived as threats, and the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral consequences of such threat perceptions. Herein, threat perceptions are considered a key explanatory factor of prejudice. As explanations of threat perceptions, this literature emphasizes inter-group characteristics: inter-group relations (history of conflict, cultural differences, relative power), their cultural characteristics (such as collectivist vs. individualist values), situational factors (such as the presence of inter-group contact), or individual characteristics of ingroup members (attitudes such as identification with the ingroup, social dominance orientations, or authoritarianism) (Stephan, Renfro, and Davis Reference Stephan, Renfro and Davis2008).

Curiously, much of this work does not define the terms “threat” or “threat perception.” As an exception to this pattern, Stephan and Renfro (Reference Stephan and Lausanne Renfro2002) consider threat perceptions as “cognitive appraisals” that arise from “the anticipation of negative outcomes” deriving from “intergroup interactions.” Further, these authors develop one of the most important conceptual contributions of this theoretical approach: a typology of threats. Integrated threat theory distinguishes four types of threats, depending on whether they are perceived to affect the material or symbolic well-being of individuals or groups. Material threats (sometimes called realistic threats) concern the very existence of the individual or the ingroup, its well-being, territory, resources, or power (Jackson Reference Jackson1993; Zárate et al. Reference Zárate, Garcia, Garza and Hitlan2004). Symbolic threats regard belief systems, values, identities, or worldviews of the individual or ingroup that the outgroup is perceived to peril (Albada, Hansen, and Otten Reference Albada, Hansen and Otten2021; Schmuck and Matthes Reference Schmuck and Matthes2017; Stephan, Renfro, and Davis Reference Stephan, Renfro and Davis2008; Stephan et al. Reference Stephan, Renfro, Esses, Stephan and Martin2005). Both for the conceptualization and categorization of threats, and for the analysis of their potential explanations, integrated threat theory assumes intergroup relations between a clear outgroup, perceived as the source of the threat, and an ingroup, perceived as threatened.

Applying Integrated Threat Theory to Feminism

Different from immigration, the goals of feminism cannot as easily be projected onto an outgroup, because men and women do not as clearly form an ingroup/outgroup relationship. Women and men share their households and everyday lives in the private realm and increasingly in the public sphere, they are closely related through family ties and frequently enter romantic relationships. Women cannot credibly be framed as a “new” population group or “strangers,” their population share is relatively constant, and they are not significantly different from men in cultural terms. Hence, women cannot be conceptualized as an outgroup in the way that immigrants or ethnic minorities often are.

While the outgroup of reference may not be as clear, we argue that feminism can still be considered a threat within the framework of integrated threat theory. The threatened element is, in this case, the material and symbolic patriarchal order. Feminists aim for fundamental social change on various institutional, social, and personal levels, with potentially far-reaching consequences for both men and women in the public and private spheres. Even in contexts where gender equality is a socially valued principle, feminism can generate uneasiness and even hostility (Scharff Reference Scharff2016), and in contexts where gender issues are highly salient, counter-reactions to feminist mobilizations have been shown to affect attitudes and political behavior (Anduiza and Rico Reference Anduiza and Rico2024; Off Reference Off2023). Hence, the importance of understanding what makes feminism a threat to some.

First, feminism can be considered a material threat. Corroborating the literature about material threat perceptions, studies show that men perceive women’s empowerment as threatening in the context of labor market competition (Alexander et al. Reference Alexander, Charron and Off2025; Kim and Kweon Reference Kim and Kweon2022; Mansell et al. Reference Mansell, Harell, Thomas and Gosselin2022; Off et al. Reference Off, Charron and Alexander2022). Similarly, Off (Reference Off2024) shows that radical right voters employ zero-sum arguments when justifying their opposition to both immigration and feminism: the gains of immigrants or women are perceived as coming at the expense of natives or men. This is consistent with previous work on understandings of gender relations as a zero-sum game (Ayanian et al. Reference Ayanian, Uluğ, Helena and Zick2024; Ruthig et al. Reference Ruthig, Kehn, Gamblin, Vanderzanden and Jones2017).

Second, symbolically, feminism as a collective struggle can threaten liberal values of independence and individualism, and perceptions of women’s ability to individually handle their matters (Dyer and Hurd Reference Dyer and Hurd2018). Moreover, feminism can be seen as a rejection of femininity, men and masculinity, nuclear families, and heterosexual relations, hence putting into question some core symbolic elements of our societies (Ogletree et al. Reference Ogletree, Diaz and Padilla2019) that both women and men often tend to endorse.

It is noteworthy, however, that counter-reactions to feminism are not always present. Some studies find no reaction against women’s rising descriptive representation in political decision-making bodies, which may be considered a symbolic rather than material threat, given that most men are not political decision-makers themselves (Breyer Reference Breyer2024; Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019; Coffé et al. Reference Coffé, Saha and Weeks2024; Fernández and Valiente Reference Fernández and Valiente2021; Kao et al. Reference Kao, Lust, Shalaby and Weiss2023). There is thus mixed evidence on whether feminism or advances in gender equality are perceived as symbolic threats, which calls for a deeper understanding of what is behind these perceptions.

Conceptualizing Feminism as a Threat

Feminism as a threat can be operationalized using different strategies. First, one may use objective indicators such as the strength of the feminist movement in a certain area or country, or the presence of feminism in the media. Similar strategies are used in studies on other kinds of potential threats using contextual indicators such as crime rates, unemployment, immigration, or terrorist attacks. This approach, however, has two limitations. First, it takes for granted the threatening character of contextual factors, which may be clearer in some cases (e.g., war) than in others (e.g., gender quotas). Second, it neglects the fact that objective external conditions may be differently perceived by different people.

A second option is to measure perceptions of feminism as a threat by measuring attitudes toward feminism. Attitudinal measures have been used to analyze other threats, including perceptions of global status threats (Mutz Reference Mutz2018), globalization threats (Teney et al. Reference Teney, Lacewell and De Wilde2014), climate change threats (Singh and Swanson Reference Singh and Swanson2017), and immigration-related threats (Scheepers et al. Reference Scheepers, Gijsberts and Coenders2002; Stephan and Renfro Reference Stephan and Lausanne Renfro2002). More closely related to feminism, gender-related threats have been approximated by measuring perceptions about men and women (Stephan et al. Reference Stephan, Stephan, Demitrakis, Yamada and Clason2000). Several studies investigate attitudes toward gender quotas or parity in political decision-making bodies (Breyer Reference Breyer2024; Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019; Coffé et al. Reference Coffé, Saha and Weeks2024; Kao et al. Reference Kao, Lust, Shalaby and Weiss2023; Muriaas and Peters Reference Muriaas and Peters2024). Yet, these studies do not explicitly mention threats related to feminism, complicating the distinction between attitudes and threat perceptions. As Giani (Reference Giani2021) shows, negative attitudes and threat perceptions do not necessarily go hand in hand and should thus be distinguished.

In addition, one problem with the above-presented alternatives to proxy threat perceptions is that perceiving something as threatening does not only require a negative perception of it but also a perception that it can bear significant consequences for the respondent or society in general. One can always perceive something in negative terms, but also as irrelevant or unlikely to affect oneself or one’s ingroup. Thus, holding negative attitudes toward an object differs from considering this object a threat. This corroborates Anduiza and Ares’s (Reference Anduiza and Ares2023) finding that threat perceptions differ significantly from issue positions regarding climate change, feminism, and pandemics.

Building on the above literature and considerations, we conceptualize threat perceptions as cognitive appraisals that involve both a negative perception of the object (in our case, feminism) and a sense of vulnerability to the object. In other words, subjects should perceive that the object is “harmful” for their material/symbolic/individual/collective interests, but also that the object is “able” to produce this harm over individuals or their communities. This is similar to the approaches taken by other scholars regarding other sources of threat (Kachanoff et al. Reference Kachanoff, Bigman, Kapsaskis and Gray2020). Our threat definition implies that people’s perceptions of feminism as a threat can derives from different factors, tapping into both the components of negativity and vulnerability that are part of our threat definition. One set of explanations relates to anti-feminist, conservative, or postfeminist political attitudes. Another important source of threats may lie in nonpolitical predispositions, namely people’s feelings of vulnerability facing something the consequences of which they do not fully grasp or control.

Explaining Threat Perceptions of Feminism

To what extent perceptions of feminism as a threat are conditioned by material or social vulnerability, by psychological predispositions (emotions of anxiety and fear, or a threat-oriented mindset), or by political and ideological orientations, is an important question with implications for how to interpret the phenomenon. If material or social vulnerability affects perceptions of feminism as a threat, then these may be considered in light of material threat hypotheses commonly used to explain anti-immigration attitudes. If motivations are mainly political, perceptions of feminism as a threat can be considered another layer of gender-related political attitudes, similar to sexism or feminist identity, correlating with progressive political values. Finally, if nonpolitical psychological factors play a significant role, feminists will have to deal with resistance that stems not only from political opponents but also from psychological predispositions and the uncertainty induced by different challenges to contemporary societies.

Feminism challenges the privileges and dominance that men have traditionally enjoyed, be it in politics, the labor market, or the household. It aims to decrease women’s dependence on men and, thereby, men’s power over women, both structurally and individually. Men may thus perceive feminism as threatening to their status in various spheres of their lives, including their professional and private lives. In its most extreme versions, feminism is perceived as men-hating and this perception is more prevalent among men (Ogletree et al. Reference Ogletree, Diaz and Padilla2019). Empirically, women are more likely to hold gender egalitarian values (Shorrocks Reference Shorrocks2018), often explained by women’s self-interest and exposure to gender discrimination (Bolzendahl and Myers Reference Bolzendahl and Myers2004; Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2009). Women are also more likely to identify as feminists (Huddy et al. Reference Huddy, Neely and Lafay2000; Ipsos 2019). For all these considerations, there is a strong expectation that men are generally more likely than women to perceive feminism as a threat.

H1: Men are more likely to feel threatened by feminism.

However, in terms of psychological predispositions, the literature on threat perceptions shows that women generally feel more threatened by various factors (Ethier and Deaux Reference Ethier and Deaux1990; Goodwin et al. Reference Goodwin, Willson and Stanley2005; Valentova and Alieva Reference Valentova and Alieva2014a). Past research has also shown that some women may dislike and even feel threatened by feminism, considering it victimizes women and thereby deprives them of their individual agency (Christiansen and Høyer Reference Christiansen and Høyer2015). They may also see feminism as antithetical to their preferred idea of womanhood as motherhood, caring, and nurturing, and harmful to traditional families and their status as housewives (Leidig Reference Leidig2023; Stotzer and Nelson Reference Stotzer and Nelson2025). Some women may reject goals typically associated with the feminist movement in the name of feminism itself, for example, by claiming that legalizing abortion goes against women’s best interests and killing an unborn goes against feminist principles (McClain Reference McClain1994). These phenomena have often been researched as relatively niche phenomena, e.g., in online forums of women opposing feminism (Christiansen and Høyer Reference Christiansen and Høyer2015), among social media influencers considering themselves as “tradwives” (Leidig Reference Leidig2023; Stotzer and Nelson Reference Stotzer and Nelson2025), or in associations such as “Feminists for Life” (McClain Reference McClain1994). We therefore do not expect them to strongly affect women’s average perceptions of feminism as threatening in a population, particularly in contexts where feminism has enjoyed relatively high levels of visibility and support.

Building on integrated threat theory, a second explanatory factor for threat perceptions is related to material vulnerability. We know from previous work that individuals facing competition for resources are more likely to feel threatened by various issues (Mansell et al. Reference Mansell, Harell, Thomas and Gosselin2022; McLaren and Johnson Reference McLaren and Johnson2007; Scheepers et al. Reference Scheepers, Gijsberts and Coenders2002), including by women’s rights and gender quotas (Kim and Kweon Reference Kim and Kweon2022; Off et al. Reference Off, Charron and Alexander2022). Low socioeconomic status (in terms of income, education, and employment conditions) is expected to make people feel more threatened. However, we should also consider vulnerability in a broader sense, comprising not only economic deprivation but also a social dimension including health protection, participation in leisure activities, and access to the support of social networks (Sass et al. Reference Sass, Moulin and Guéguen2006). We expect that individuals, and particularly men, with lower socioeconomic status, who face material and social vulnerability, are more likely to perceive feminism as a threat.

H2a: People with low socioeconomic status and high material and social vulnerability are more likely to perceive feminism as a threat.

H2b: These effects are stronger for men.

Third, perceptions of feminism as a threat may also be related to how people generally perceive the challenges posed by their contexts. Individuals vary in the extent to which stress induced by the environment is processed as a threat or as a challenge (Crum et al. Reference Crum, Akinola, Martin and Fath2017). Likewise, individuals’ mindsets may vary in the extent to which they perceive any given outgroup as a threat. Hence, one could expect that people who generally feel higher levels of anxiety are more likely to feel threatened by feminism. One could also expect some spillover effects across different potential sources of threat. For example, previous work has found such spillover from COVID-19 threat perceptions to immigration threat perceptions (Duque et al. Reference Duque, De Coninck and Montero-Zamora2024). We argue that a perception of a threatening condition (e.g., climate change or immigration) could exacerbate perceptions of threat regarding other issues (e.g., feminism), despite the fact that different threat perceptions tend to be associated with different ideological camps. In other words, even people who perceive threats that are usually associated with left-wing ideology (e.g., climate change threat perceptions; Gregersen et al. Reference Gregersen, Doran, Böhm, Tvinnereim and Poortinga2020) may become more likely to perceive threats associated with right-wing ideology (e.g., immigration or feminism threat perceptions), simply because of a spillover effect between different threat perceptions.

H3: People who feel anxious or threatened by other phenomena are more likely to also feel threatened by feminism.

Finally, feminism is a concept heavily loaded with political connotations that people identify with left-wing or progressive politics (Elder et al. Reference Elder, Greene and Lizotte2021; McCabe Reference McCabe2005). Gender equality values can also be strongly influenced by ideology (Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Yudkin, Juan-Torres and Dixon2019). Hence, we expect political attitudes to play an important role in considering feminism as a threat. These attitudes may be related to religious identities, preferences for certain values such as order over freedom, ideological orientations, or partisanship. We expect people who are Catholic, prefer order over freedom and hold more conservative positions to be more likely to perceive feminism as a threat. Religiosity is associated with benevolent sexism (Glick et al. Reference Glick, Lameiras and Castro2002) and with more conservative attitudes toward feminism, especially among older generations (Fitzpatrick Bettencourt et al. Reference Fitzpatrick Bettencourt, Vacha-Haase and Byrne2011). At the elite level, the Catholic Church is also a powerful anti-feminist actor (Lavizzari and Prearo Reference Lavizzari and Prearo2019; Paternotte and Kuhar Reference Paternotte and Kuhar2018). Feminism is typically considered progressive/liberal/left-wing, and hence, more likely to be perceived as a threat for those who hold conservative views. In addition, political conservatism has been generally connected to enhanced threat perceptions (Jost et al. Reference Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski and Sulloway2003), even if this association may depend on the type of threat and the context (Brandt et al. Reference Brandt, Turner-Zwinkels and Karapirinler2021). This leads us to our final hypothesis.

H4: People holding religious (Catholic), right-wing, and conservative values are more likely to feel threatened by feminism.

Case, Data, and Methods

Case

We analyze perceptions of feminism as threatening the context of Spain, a case characterized by several relevant features for our concerns. Spain is a country in which public opinion on feminism and gender equality is relatively positive, compared to similar countries (YouGov 2023). As in many other places, feminism has also become increasingly salient in recent years (Rozado Reference Rozado2023). Spain has shown particularly high levels of feminist mobilization. Following the global wave of feminist protests that shook the world regarding sexual harassment and violence against women, Spain witnessed women’s marches and strikes of historical proportions in 2018, spurred by a case of gang rape that generated a wave of outrage (Beatly Reference Beatly2019) that continued in 2019 (Anduiza and Monza Reference Anduiza, Monza, Eduardo and Luisa Elena2025).

These feminist mobilizations have been followed by significant changes in legislation within a relatively short time period between 2020 and 2024. This has included a bill introducing equal parental leave for fathers and mothers of 16 nontransferable weeks (Marinova and León Reference Marinova and León2025), a law enlarging sexual and reproductive rights (including access to abortion in public hospitals without imposed “reflection” periods, menstrual and pregnancy interruption leaves, and affective-sexual education in all education stages), and several pieces of legislation that extended the equality law of 2007. It has also included two more controversial bills led by the Podemos-led Equality Minister Irene Montero, the “Ley Trans” (translates to: “Trans Law”) and the “Ley del solo sí es sí” (translates to: “Only Yes Means Yes Law”). The former was introduced to prevent the discrimination of trans people and among other measures removed any requirements for changes in registered sex. The latter was the legislative consequence of 2018 mobilizations against sexual violence; although it included many aspects (notably covering all victims of sexual violence and not only parters or ex-partners as the 2004 law), public attention mostly focused on the criminal dimension. Because the law removed the distinction between sexual abuse and sexual assault, it had the unintended consequence of reducing the penalties of over 900 sexual offenders, causing important public opinion concern that pushed for subsequent legislative changes (García Sánchez Reference García Sánchez2023).

The case that contextualizes our analysis is, therefore, one in which feminist mobilization has been intense and initially supported by public opinion, followed by a period of very intense policymaking. Contrary to what happened in the early 2000s, when gender equality legislation was less salient but considered as a valence issue supported by all parties in Parliament, in the 2020s, the context has been one of surging visibility, clear connection of the feminist agenda with a specific political party (the left-wing Podemos), heightened polarization, and increasing levels of modern sexism associated with the rise of the far-right (Anduiza and Rico Reference Anduiza and Rico2024; Coffé et al. Reference Coffé, Fraile, Alexander, Fortin-Rittberger and Banducci2023).

This suggests that this feminist momentum could be perceived as a threat by some, generating a counter-reaction. Anti-feminist discourse has increased with the presence of the far-right party Vox, which has pictured feminists as “violent” and “communists and radicals” (Alonso and Espinosa-Fajardo Reference Alonso and Espinosa-Fajardo2021; Bernardez-Rodal et al. Reference Bernardez-Rodal, Rey and Franco2020). In light of these developments, Cabezas (Reference Cabezas2022) argues that “the feminist protest cycle has turned feminism into one of the main vectors of politicization in Spain” (p. 320), wherein the far-right takes an important role in opposing feminism. Considering these rapidly rising and highly salient feminist mobilizations and anti-feminist responses, Spain constitutes an interesting case for the analysis of people’s perceptions of feminism as threatening. While our findings are specific to the Spanish context, we suggest that they may travel to other contexts with a history of relatively conservative gender norms, salient and strong feminist mobilizations, rapid feminist social and legislative changes, and strong and visible anti-feminist countermovements.

Data

We rely on data from the POLAT Dataset (Pannico et al. Reference Pannico, Carolina, Enrique, Guillem and Eva2025), an online panel study conducted yearly on a sample with quotas based on sex, age, education, region, and municipality size to ensure a balanced representation of the Spanish adult population aged between 18 and 61 years (see Appendix 1 for more information on the survey). The analysis focuses on the five waves fielded between 2020 and 2024, for which the battery on perceptions of feminism as a threat is available. Refreshment samples were added to the panel at certain points to address the challenges to representativeness and sample size resulting from panel attrition. Table A1 provides an overview of the number of respondents and the sample composition in each of the waves used in the paper and a description of the main features of the panel.

Our dependent variable is a novel measure capturing perceptions of feminism as a threat. As argued earlier, we define threats as perceptions of potential future harm, similar to previous works on other types of threats (e.g., Canetti-Nisim, Ariely, and Halperin Reference Canetti-Nisim, Ariely and Halperin2008; Kachanoff et al. Reference Kachanoff, Bigman, Kapsaskis and Gray2020). By implying a potential harm inflicted by feminism, we aim to distinguish this threat measure from indicators capturing attitudes or affect. To perceive feminism as threatening, respondents must not just disagree with or dislike feminism, but they must also perceive that it could harm them. To capture the different symbolic/material and individual/collective dimensions of threats, we use the following battery:

To what extent do you think that in the future feminism will harm…

a) Your work or economic prospects

b) The work or economic prospects of your country

c) Your way of life and values

d) The way of life and values of your country

1: A lot/ 2: Somewhat/ 3: Little/ 4: Not at all

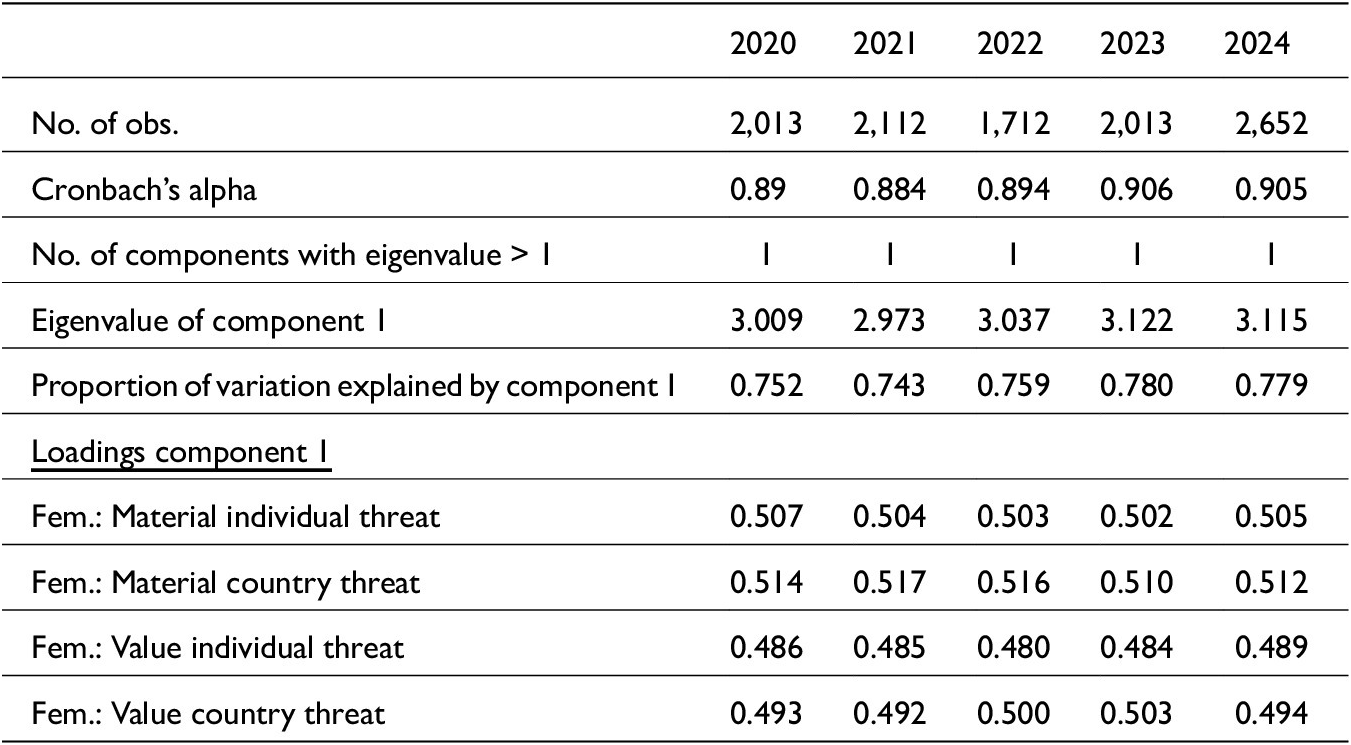

While, in theory, respondents may respond differently to the different items, we find that all tap into one single dimension of threat perceptions. Thus, while such threat perceptions may still be related to material or symbolic predictors, the perception of feminism as threatening is not limited to either material or symbolic, or either individual or collective concerns. Rather, all four dimensions behave similarly. Table 1 shows a principal component analysis (run separately by survey wave to account for the panel structure) confirming that all four feminist threat items load on one component, with the first eigenvalue representing between 74% and 78% of the variance in these items, depending on the survey wave. The first component reveals high correlations with all four items, ranging between 0.48 and 0.517. This means that, while we cannot rule out that the four dimensions of threats (individual and collective, material and symbolic) exist in relation to feminism, people do not seem to make such a distinction when answering the items of this question. When they feel threatened, they tend to feel threatened on all dimensions.

Table 1. Cronbach’s alpha and PCA results: Feminist threat perception indicators

Unrotated principal components on standardized variables.

We therefore use an additive index of feminist threat perceptions in our analyses. The feminism threat index is based on the four items and rescaled to range from 0 to 1, where higher values equal stronger perceptions of feminism as threatening. The four items’ Cronbach’s alpha equals around 0.9 in all survey waves (see Table 1), confirming the internal consistency of the four items. The index correlates as expected with other variables capturing political attitudes toward feminism (see Appendix 2 for pairwise correlations). For instance, it is negatively related to self-identification with feminism (r = -0.247, p-value < 0.00) and positively related to modern sexist attitudes (Swim et al. Reference Swim, Aikin, Hall and Hunter1995; r = 0.294, p-value < 0.00). Our measure of perceptions of feminism as threatening thus behaves as expected in relation to political attitudes and shows convergent as well as construct validity.

One of our main independent variables is gender (0 = man, 1 = woman). To capture material vulnerability, we use education (0 = compulsory, 1 = secondary, 2 = college), household income (on a 0-10 scale, rescaled to a 0-1 scale, where 0 equals “300€ or less” and 1 equals “6,000€ or more”), and a dummy variable for unemployment. We also include a battery of 10 items based on the EPICES score to measure social and socioeconomic vulnerability (Sass et al. Reference Sass, Moulin and Guéguen2006; Reference Sass, Belin, Chatain, Moulin, Debout and Duband2009).Footnote 1 The items include having, in the past 12 months, visited a social worker or assistant, not practiced sports, not gone to theaters, or not gone on holidays, not seen any relative in the past 6 months, not having private medical insurance, not owning or expecting to own a house in the near future, having serious economic difficulties, and not having anyone close to turn to in case of economic or logistic difficulties. The scale is recoded such that 0 equals low social and socioeconomic vulnerability and 1 equals high vulnerability.

To capture psychological predispositions to feel threatened of an emotional nature, we approximate respondents’ general anxiety levels. The survey includes a question on respondents’ perception of the current most important problem in the country. This is followed by a battery of questions capturing, on a 5-point scale from “none” to “a lot,” to what extent the indicated problem evokes in the respondents: anxiety, annoyance, fear, sadness, and anger. We take respondents’ answers on how much anxiety and fear they feel about the indicated most important problem of the country and combine both items into one measure of anxiety, which we recode to range from 0 to 1, where 1 equals higher levels of anxiety.

Further, we approximate respondents’ more general psychological predisposition to feel threatened by indicators of threat perceptions regarding climate change and immigration (only the 2023 and 2024 waves include the immigration threat indicator), as a proxy for whether respondents feel threatened by issues other than feminism. We use the same survey question battery as we use to capture respondents’ threat perceptions of feminism, asking to what extent respondents think that climate change and immigration will harm different aspects of their lives in the future (ego vs. sociotropic, material vs. symbolic). In addition to the four above-listed response items, the battery on climate change includes a fifth item asking about the perceived threat of climate change to respondents’ health. All have been recoded so that 0 indicates low and 1 high perceptions of threat.

To capture political and cultural attitudes, we include whether the respondent is Catholic/religious (1) versus a nonbeliever (0),Footnote 2 respondents’ preference for freedom vs. traditional values (a 0-10 scale recoded to 0-1), and self-reported left-right ideology (a 0-10 scale recoded to 0-1). People are also asked about the probability that they would vote for different parties on a 0-10 scale. This variable is recoded to range from 0 to 1 for each of the main parties (the social democratic PSOE, the center-right PP, the left-wing to far-left party Podemos and electoral platforms IU and Sumar, and the far-right Vox).

To better understand the ideological profiles of people with different perceptions of feminism as a threat, in parts of the analyses, we use the modern sexism scale (based on the original battery by Swim et al. Reference Swim, Aikin, Hall and Hunter1995, plus one item used by Anduiza and Rico Reference Anduiza and Rico2024), ranging from 0 to 1. We also include an 11-point scale (reversed) measure of feminist identity that ranges from 0 (completely feminist) to 1 (not at all feminist).

Finally, we include a range of demographic variables as controls. These include age (recoded such that 1 = 18-29; 2 = 30-39; 3 = 40-49; 4 = 50+), urban (0) or rural (1) residence in a range of 5 categories, region, whether respondents live with a partner and/or have children (see Appendix for details on these variables’ measurement and coding, and for summary statistics).

Methods

We start by looking descriptively at gender gaps in threat perceptions between men and women to test H1. We then consider the effects of different predictors of feminist threat perceptions derived from the theory stated above to test H2a, H2b, H3, and H4. Given the nature of our dependent variable, the feminism threat index, we apply linear regression analyses.

Next, to better understand the profiles of different people who feel threatened by feminism, we run LPA. Similar to latent class analysis (Lanza et al. Reference Lanza, Flaherty and Collins2003), LPA identifies latent subpopulations within a population sample based on a specified set of variables in the model. Unlike latent class analysis, which analyzes subpopulation classes based on categorical variables, LPA allows for analyzing continuous variables (Sinha et al. Reference Sinha, Calfee and Delucchi2021). As the variables of our interest are continuous, we apply LPA. In our LPA, we include indicators of political values and psychological predispositions to feel threatened. These include liberal values (freedom vs. order), left-right ideology, feminist self-identification (reversed), modern sexism, threat perceptions of climate change and immigration, as well as anxiety. We constrain the LPA to the 2024 survey wave, which allows us to include the immigration threat variable, which is particularly relevant to analyzing people’s perceptions of social threats beyond feminism, while including as many observations as possible.

We estimate four profiles. While the model-selection statistics, including Schwarz’s Bayesian (BIC) and the Akaike (AIC) information criteria, indicate that higher numbers of estimated profiles would yield even more accurate results, they would also result in the inclusion of small profiles (around 5% of the sample) that differ little from other profiles. Therefore, we constrain our analysis to four profiles. To better understand the characteristics of the four estimated latent subpopulation profiles, we estimate their relationship with five covariates of our interest: gender, income, education, the probability of voting for different parties, and political interest.

Results

We organize the results in three sections. First, we descriptively present our measure of feminist threat perceptions. Second, we investigate its covariates to test our hypotheses, using linear regression analyses. Third, we use exploratory LPA to investigate the unexpected finding that women feel similarly or even more threatened by feminism than men.

Is Feminism Perceived as a Threat?

Figure 1 shows the distributions of the four threat indicators that we use to compute the feminist threat index (material vs. value threat to the individual vs. the country). As Figure 1 shows, the majority of respondents feel rather little threatened by feminism in any of the four measured ways. The mean value for all four indicators ranges between 1.89 and 2.21 on a 1–4 scale, where 1 equals “not at all threatened” and 4 equals “very threatened” (see Tables A2–A3 in the Appendix for summary statistics). While three of the four threat indicators are similarly distributed (half of the sample perceives rather low levels of threat), one indicator stands out: respondents perceive feminism as less threatening to their own values (egotropic symbolic threat), compared to the country’s values or their own and the country’s material situation.

Figure 1. Box plots of the feminist threat indicators.

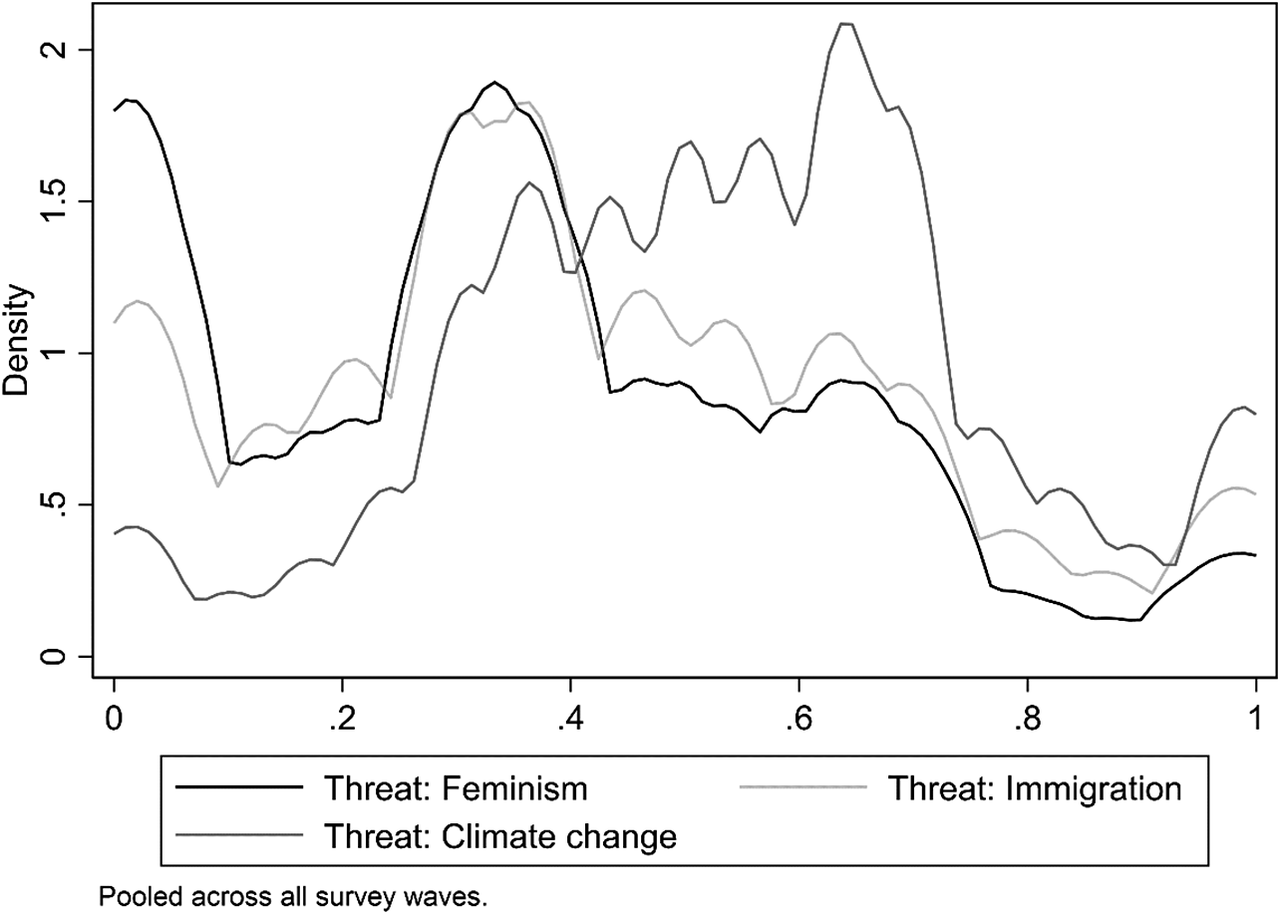

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the feminist threat perceptions index, comprising all four survey items measuring the different types of feminist threat perceptions. Further, the figure shows the distributions of other available indicators of threat perceptions, namely threat perceptions of immigration and climate change. Immigration and feminist threat perceptions are similarly distributed (with feminist threat perceptions slightly more skewed toward lower values), pointing to possible parallels in social threat perceptions of different kinds. Threat perceptions of climate change follow a different distribution, with more people feeling threatened on average.

Figure 2. Feminist threat perceptions and other threat perceptions.

Who Feels Threatened by Feminism?

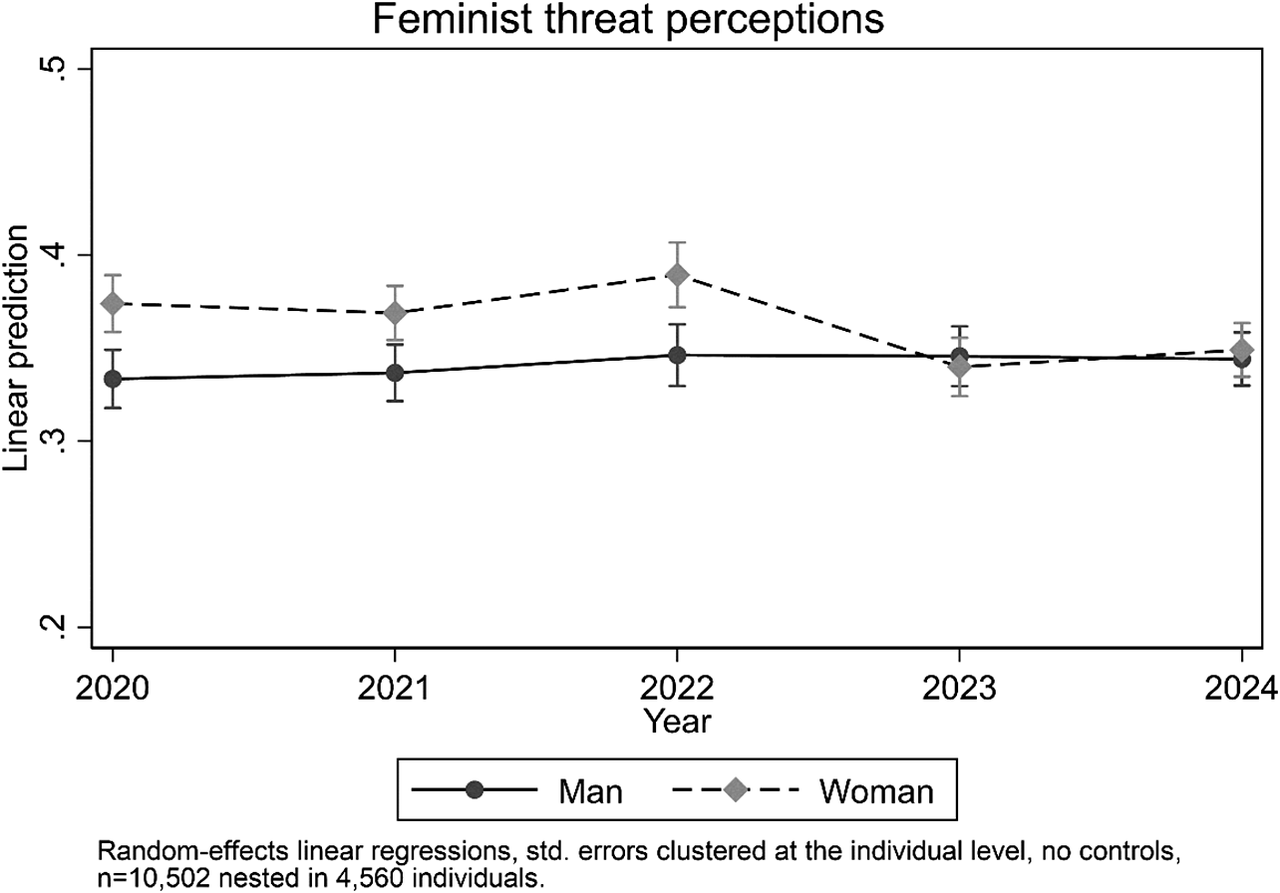

Figure 3 shows men’s and women’s feminist threat perceptions calculated via bivariate random-effects linear regressions. The level of feminist threat perceptions is relatively stable across the five investigated survey waves from 2020 to 2024. Further, men’s and women’s distributions of feminist threat perceptions are largely similar, and seem to become even more similar at the end of the investigated time period (see Table A5 for t-tests results by gender and wave, and Figure A2 for the distribution of the index by gender across waves). In contrast to our expectation that men feel more threatened by feminism (H1), the results illustrate that women tend to perceive feminism as similarly threatening as men, and even slightly more at the beginning of the analyzed period. In 2023 and 2024, there is no gender gap in feminist threat perception. Across all survey waves, descriptive bivariate analyses thus refute our expectation of men’s higher threat perceptions (H1). We will return to this puzzle later in our analyses.

Figure 3. Gender gaps in feminist threat perceptions across survey waves.

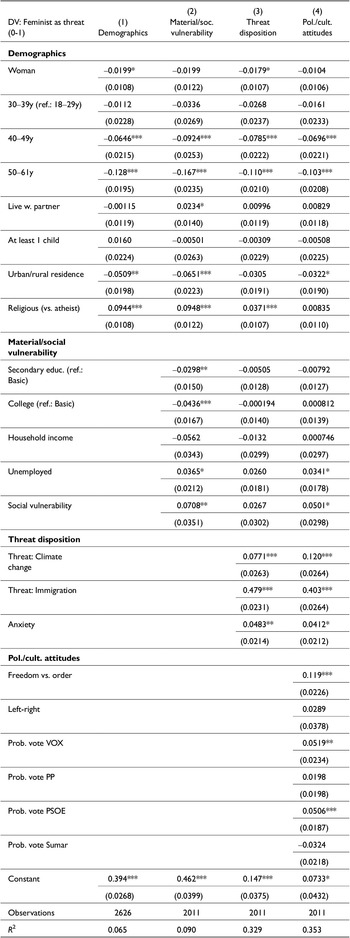

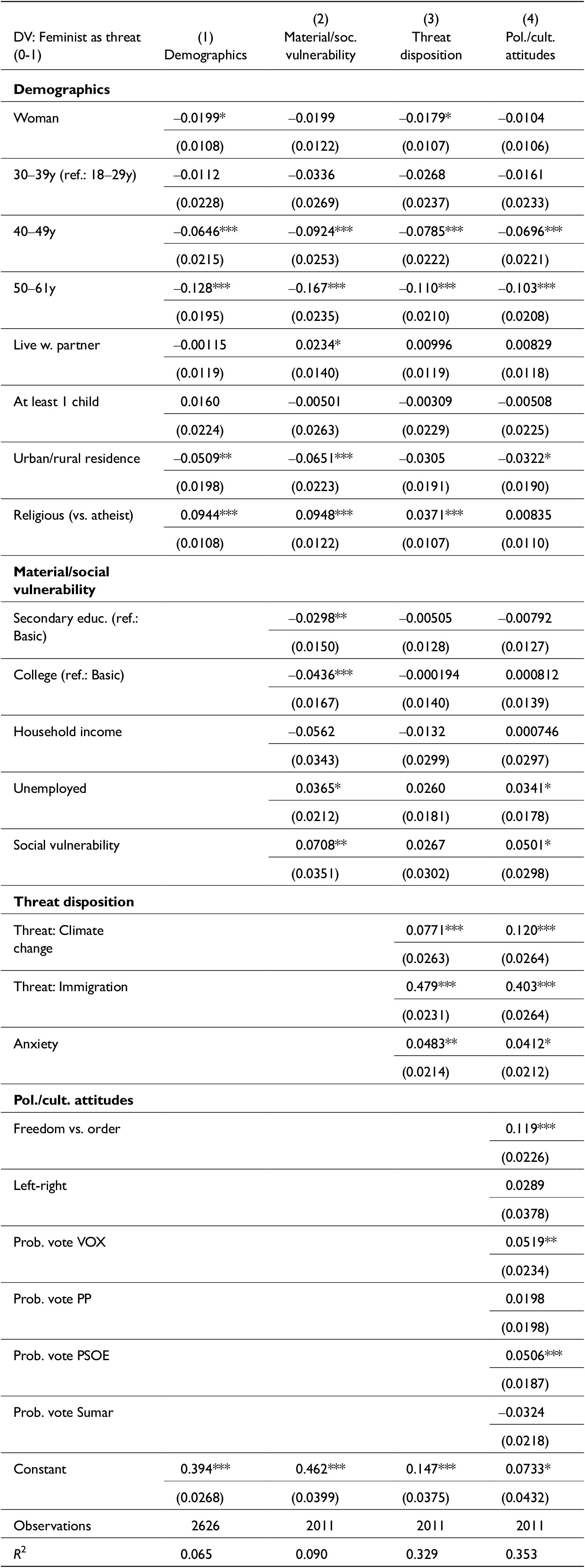

We proceed with multivariate analyses to better understand the predictors of feminist threat perceptions and test our remaining hypotheses. Table 2 and Figure 4 show the results of multivariate Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analyses of feminist threat perceptions on a range of relevant theorized independent variables (see Appendix Tables A6–A9 for full regression models for survey waves 2020–2023).

Table 2. Multivariate regression analyses, 2024

Figure 4. Multivariate regression analyses (Models 2 and 4, Table 2), 2024.

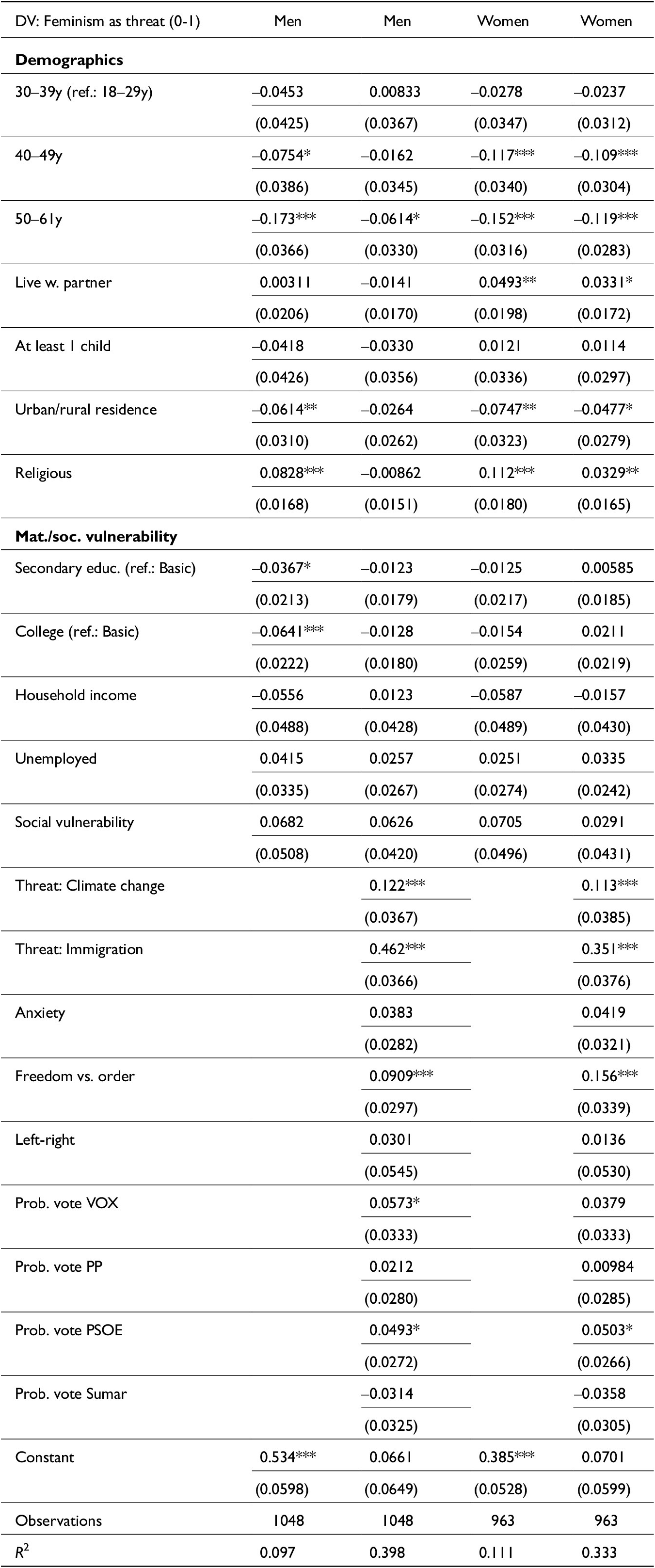

Regarding the effects of socioeconomic status and material and social vulnerability, we find partial support for our H2. Higher education is related to lower perceptions of threat, while social vulnerability is related to higher threat perceptions (see Model 2 in Table 2). As visualized in Figure 4, the effect sizes are however relatively small. Considering a 95% significance level, we fail to find significant effects for income and unemployment. Across survey waves, these effects slightly differ (see Appendix Tables A6–A9). The only material/social vulnerability indicator that is consistently related to feminist threat perceptions across survey waves is higher education. Table 3 further shows that these effects mostly do not differ by gender, as suggested by H2b. The only gender difference lies in the finding that highly educated men are less likely to perceive feminism as threatening, while education is not related to women’s perceptions of feminism as threatening.

Table 3. Regression analyses by gender, 2024

Standard errors in parentheses; * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01; controlling for region.

Our results confirm H3 regarding psychological predispositions toward threat perceptions in general. Anxiety feelings evoked by the problem that respondents perceive as most important for the country are positively and significantly related to feminist threat perceptions. These effects remain significant even after introducing additional attitudinal controls (p-value <0.05, see Model 4 in Table 2). Feeling threatened by immigration is positively related to feminist threat perceptions and constitutes the strongest predictor of feminist threat perceptions. This effect remains strong and significant even when taking into account that both perceptions of feminism and immigration as threats correlate with left-right ideology (see Model 4 in Table 2).Footnote 3 Interestingly, even perceptions of climate change as a threat, which tend to be associated with left-wing ideology, have a positive effect on perceptions of feminism as a threat. This finding suggests that threat perceptions regarding different objects may be related and there may be contagion processes. As a person feels more threatened by another phenomenon, she is more likely to feel threatened by feminism as well, pointing to a general rise in threat sensitivity and spillover effects between different types of threats. This is the case even though climate change and feminism threat perceptions are usually associated with opposite ideological profiles.

Cultural and political attitudes predict feminist threat perceptions, as suggested in H4 (see Model 4 in Table 2). As expected, people who prioritize traditional order over individual freedom and have a high probability of voting for the far-right party Vox feel more threatened by feminism. Interestingly, left-right ideology is significantly related to perceptions of feminism as threatening in survey waves 2020–2023 but not in 2024 (see Table A6–A9 in Appendix). Further, a higher probability to vote for the social democratic party PSOE is related to higher threat perceptions of feminism in 2024 but not in previous survey waves.

Possibly, the declining importance of left-right orientations is the result of a complex process of political competition within the political left, by which partisanship has become more relevant. As we mentioned when presenting the case of Spain, the years of our analysis included important policy changes regarding gender equality. The bills that generated significant levels of controversy not only with the right but also within the left (“Ley Trans,” “Ley de Solo sí es sí”), were clearly linked to the radical left party Podemos and in particular to their Minister for Equality, Irene Montero. As a result, “feminism” could be increasingly perceived as associated with the far-left party Podemos, and not with the social democratic party PSOE, even if this party has a long history of gender equality policymaking (Bustelo Reference Bustelo2016). While at the beginning of the period of analysis, perceptions of feminism as a threat are basically conditioned by having right-wing orientations, by 2024, after these two laws have been approved, being a likely PSOE voter is associated with higher perceptions of feminism as a threat.

Finally, as indicated by the R-squared values (Table 2), threat perception indicators related to climate change and immigration, and people’s anxiety associated with the problem that they consider most important, contribute most to explaining people’s perceptions of feminism as threatening. Between Model 2 and Model 3 (Table 2), adding these threat disposition indicators increases the R-squared value from 0.09 to 0.33. In comparison, material/social vulnerability indicators and political/cultural attitudes contribute rather little to explaining perceptions of feminism as threatening.

The Ambivalent Relationship Between Gender and Perceptions of Feminism as a Threat

As we show above, our analysis points to an unexpected lack of a gender gap. If anything, women have been, on average, more likely to perceive feminism as a threat, and in more recent waves, they have become just as likely as men to do so. To tackle this puzzle, we run an LPA on several attitudes relevant to understanding attitudes toward feminism, as well as available indicators approximating a general predisposition to feel threatened. In addition, we include measures of modern sexism and feminist self-identification. While including them in our regression models would have likely resulted in overspecification, adding them to the LPA helps us understand the different latent profiles of population subgroups. We restrict the analysis to survey wave 2024 to include the indicator of immigration threat perceptions and as many observations as possible.

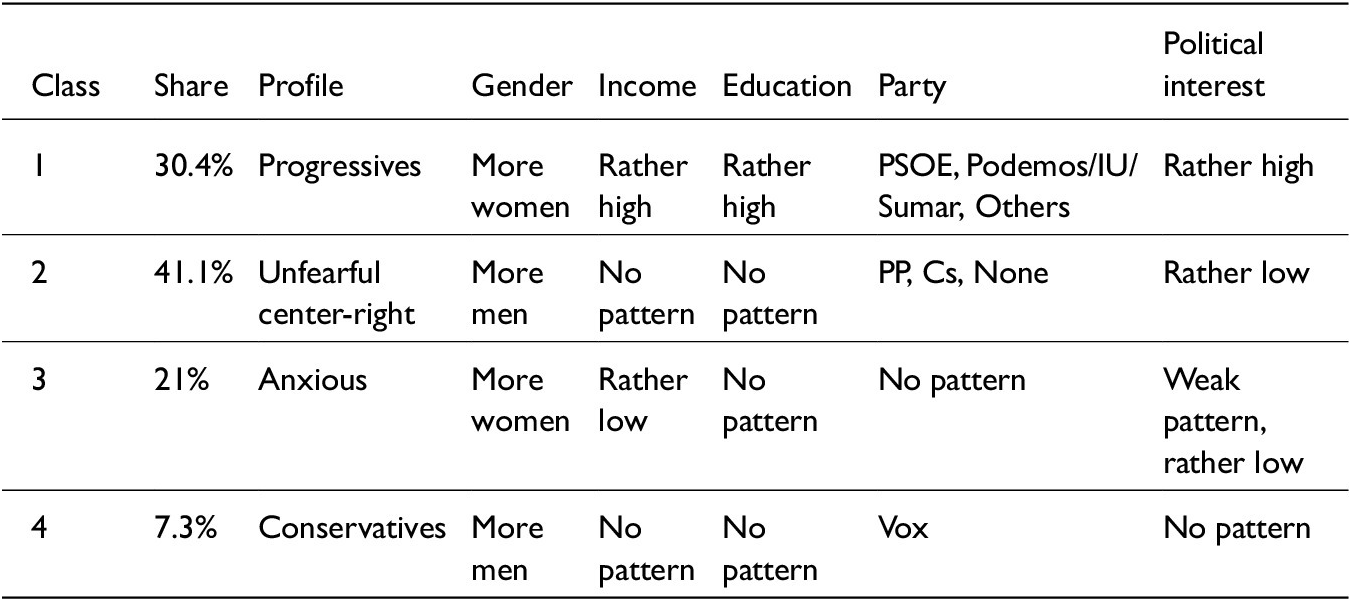

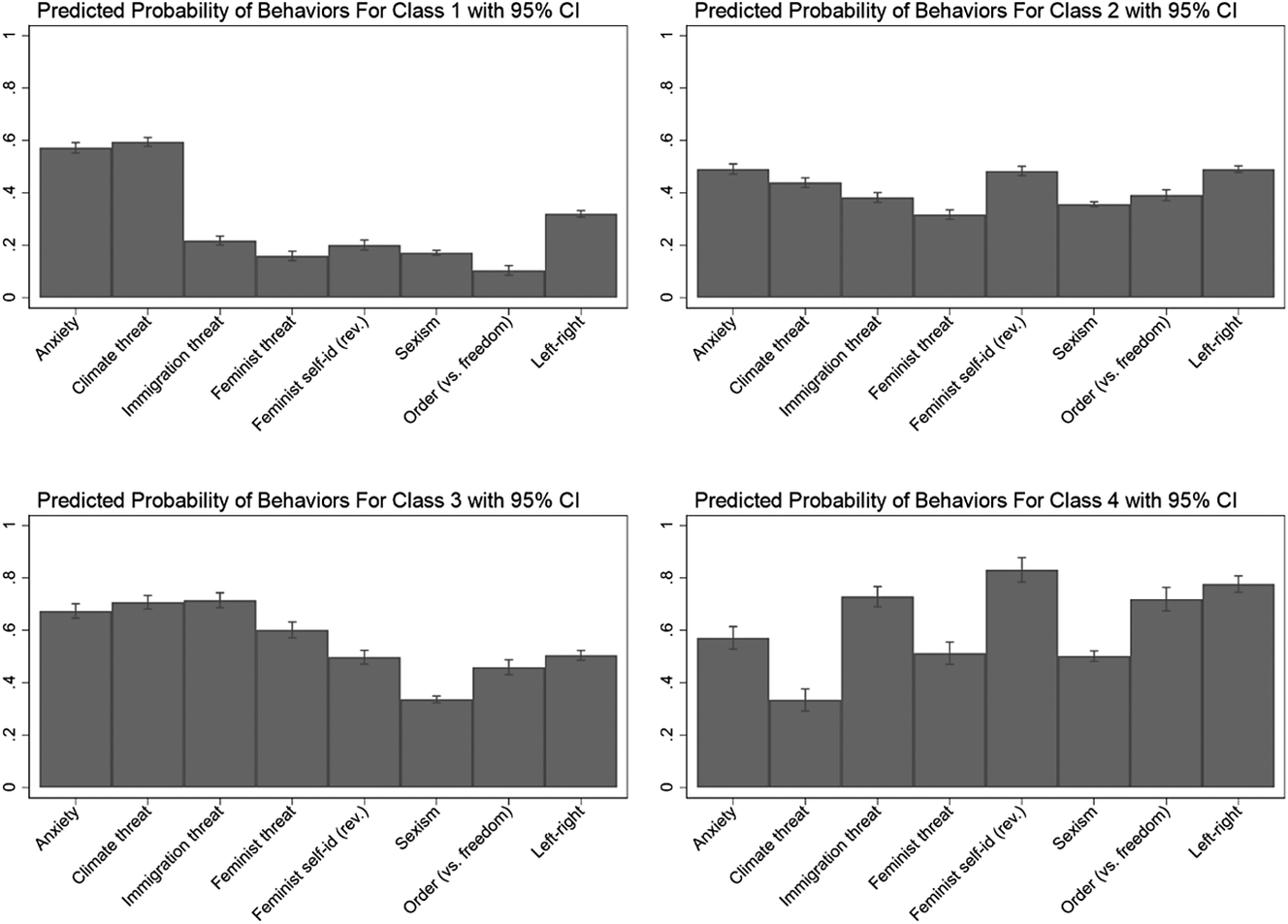

The LPA suggests four profiles, which we label as follows: the progressives (30% of the sample), the unfearful center (41%), the anxious (21%), and the conservatives (7%, see Table 4 for a summary of the profiles and Figure 5 and Figure A3 in the Appendix for more information). Progressives (profile 1) have relatively high levels of anxiety and feel threatened by climate change, but perceive neither immigration nor feminism as threatening, have higher levels of feminist identity, and hold progressive left-leaning attitudes on all included political or cultural attitudes indicators. This group is women-dominated, relatively highly educated, with a rather high income and political interest, and sympathizes with the political left.

Table 4. Summary of latent profiles

Figure 5. Predicted probabilities of selected indicators by class, 2024.

In contrast, the unfearful center-right (profile 2, the largest profile) feels less anxious and less threatened by climate change but more threatened by immigration and feminism than the progressives. However, especially compared to the third and fourth profiles, the unfearful conservatives have low threat perceptions. On political and cultural attitudes, this group can be considered ideologically center. It is men-dominated and includes people from all income groups and education levels with rather low levels of political interest. This class sympathizes with center and center-right parties and also includes many people who do not sympathize with any party.

Profile 3, the anxious, has comparatively high anxiety and threat levels on all threat indicators. These are those who feel most threatened by feminism. On political and cultural attitudes, this group takes center positions. The anxious are predominantly women and people with low income and relatively low political interest. They comprise people from all education levels and partisan affiliations.

Finally, the conservatives constitute the smallest profile. They have anxiety levels that are comparable to progressives’, and feel least threatened by climate change, compared to the other profiles. However, they feel relatively strongly threatened by immigration and a bit less so by feminism. On political and cultural indicators, conservatives are the least feminist, most sexist, most in favor of a traditional order, and most right-wing. It is therefore not surprising that they are also most sympathetic to the far-right party Vox. This group is men-dominated and comprises people from all levels of income, education, and political interest.

Overall, the LPA suggests that men and women feel threatened by feminism for different reasons. Men are overrepresented among the conservatives and the unfearful center-right. As such, their threat perception of feminism is either low (unfearful center-right) or it is associated with conservative ideology. Women in turn are overrepresented among the progressive and the anxious profiles. When their perception of feminism as a threat is high, this is associated with high anxiety and other threat perceptions, but not with strong political orientations. The LPA thus highlights two sets of factors associated with perceptions of feminism as a threat: a general predisposition to feel threatened, and conservative ideology. While the former is more common among women with no particular party affiliation, the latter is more prevalent among men and related to far-right party sympathy. The similar average levels of perceptions of feminism as a threat shown by men and women are in fact due to different configurations of attitudes, and are likely to have different consequences for political behavior.

Conclusion

This article constitutes a first attempt to conceptualize, measure, and analyze the correlates of perceptions of feminism as a threat. We define threat perceptions as an appraisal of future harm, and employ a specific measure tapping into material and symbolic elements of both individual and collective threat perceptions. We apply integrated threat theory to understand how perceptions of feminism as a threat relate to socioeconomic characteristics, psychological predispositions, and cultural and political orientations. While our findings are limited to the case of contemporary Spain, future work should assess whether our insights can travel to other contexts with similar characteristics in terms of rapid feminist social change, strong feminist movements, and associated counter-reactions.

Analyzing 2020–2024 survey data from Spain, we find that feminist threat perceptions are best explained by a general predisposition to feel anxious or threatened by different issues. Political and cultural orientations also have significant effects, which seem to change over time, likely depending on the contingent particularities of the process of politicization of feminism. Perceptions of feminism as a threat may be more or less connected to left-wing orientations, and more or less intensely related to specific political parties, even within the left. This is not set in stone and may change over time, with consequences for those who are likely to perceive feminism as a threat. In contrast, the consequences of material or social vulnerability are limited and more volatile, with the exception of higher education.

Surprisingly, we find that women and men feel similarly threatened by feminism. Further inductive analysis shows that men’s high levels of feminism threat perceptions are better explained by conservative political and cultural attitudes, and associated with far-right party sympathy. In contrast, women’s perceptions of feminism as a threat are better explained by their generally higher threat perceptions regarding all investigated threat sources and higher levels of anxiety, and are not associated with a particular party affiliation. While men and women have similar perceptions of feminism as a threat, these seem to be related to different configurations of political orientations.

These findings contribute to our understanding of threat perceptions by showing that these should not be equated with (negative) attitudes toward potentially threatening objects. Threat perceptions involve a more nuanced concept in which both negative attitudes and a sense of potential harm associated with the threat object are intertwined. Hence, when investigating social threat perceptions, future research should distinguish between political and cultural attitudes, on the one hand, and a psychological predisposition to feel threatened, on the other. Both factors are relevant to understanding threat perceptions and they may affect population groups differently.

In particular, threat perceptions seem to be gendered even if there is no apparent overall gender gap. This speaks to research on gender differences in the general perception of future uncertainty (Lagattuta Reference Lagattuta2007) or immigration-related threats (Valentova and Alieva Reference Valentova and Alieva2014b), but is also challenged by research findings that women do not feel more threatened by security threats than men (Stevens et al. Reference Stevens, Bulmer, Banducci and Vaughan-Williams2021). Future research may further investigate gendered threat perceptions across different threat sources as well as across different contexts.

There are two important implications of these findings for understanding resistance to feminism in practice. First, we find potential spillover effects of threat perceptions across different threat objects, particularly if these are ideologically connected (such as feminism and migration as threats), but even if they are not (such as feminism and climate change). Further research should explore these dynamics of threat contagion.

The second implication speaks to the challenges that feminism faces as a political project that aims to achieve gender equality. Rapid social change may not only provoke negative attitudes but also increase threat perceptions among population groups with general psychological predispositions to feel threatened, which our data suggests are women-dominated. While opposition to feminism is often portrayed in terms of ideological struggles, perceptions of threat associated with feminism may originate in a different place closer to general predispositions to anxiety. These are not expected to decline in the near future, but should be listened to if the aspiration is to advance social support for feminism as a political agenda. In times of rising anti-feminism in democracies across the world, to increase public support for feminism, it may be important to address the concerns of people who generally feel threatened by social change but may not hold particularly socially conservative attitudes.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X26100592.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for invaluable comments from the editor and three anonymous reviewers, as well as participants of the 2023 workshop on “Gender Dynamics in Politics, the Workplace and Society” at Lund University, the 2023 “Jornada de Comportament Polític i Opinió Pública” Conference at the University of Barcelona, and panels at EPSA 2023, APSA 2024, and ECPG 2024.

Funding declaration

Support for this study was provided by the Agencia Española de Investigación [Grants CSO2017-83086-R and PID2024-155487OB-I00] and by the ICREA Foundation.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.