People routinely draw on personal experiences to form broad generalizations. One especially good or bad lunch at a fast-food restaurant may yield a lifetime of loyalty or disloyalty to the entire chain. A single too hot, too rainy, too crowded beach vacation may literally send us heading for the hills the next time we have a week off. Similar processes operate in the political arena. People communicate with their elected representatives, and these connections influence how favorably the officials are perceived (Cain et al. Reference Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina1987). Visiting the DMV or the local Social Security office can yield jarring new insights about American bureaucracy. In the criminal justice system, people’s personal experiences with police and courts strongly shape their perceptions of those actors, magnifying racial disparities in judgments about the system’s fairness and competence (Peffley and Hurwitz Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2010).

Generalization of any form is a risky enterprise. Decades-long research agendas on heuristic processing in psychology and political science show that reducing our information set to a few cases or criteria can gain us much-needed efficiency but also can lure us into forming suboptimal judgments (e.g., Tversky and Kahneman Reference Tversky and Kahneman1974; Kuklinski and Hurley Reference Kuklinski and Hurley1994; Lau and Redlawsk Reference Lau and Redlawsk2001; Mondak Reference Mondak1994). Perhaps if we had given the beach another try in October—when it is not too hot, too rainy, or too crowded—we would have found it to be idyllic. Unfortunately, the information (and relaxation) benefit of that potential future sandy stroll would be forever lost if we allowed our first negative beach experience to hold too much sway on how we choose our future vacation destinations.

The insights derived from personal experiences may be critical to how citizens form judgments about governmental actors and policies. Thus, accounting for personal experience may be essential for how we conceptualize citizen competence (Cramer and Toff Reference Cramer and Toff2017). We build on this perspective via attention to a second-order experience-based inferential process. The question is whether people’s personal interactions with public officials influence not only how favorably they perceive those actors but also how favorably they view other proximate (or not so proximate) actors. For instance, suppose a person met a U.S. Senator and emerged from the encounter with heightened confidence in that official. That would be a direct experiential effect. A second-order effect would occur if the individual then extrapolated from that meeting to update her assessment of an entirely different public official such as the state’s governor, the county’s comptroller, or the city’s mayor. Where such an influence exists, we deem it an experiential spillover effect.

If experiential spillover occurs, this may be cause for concern. First, at the individual level, evaluating one actor partly based on another actor’s behaviors potentially stretches heuristic processing beyond the point where it can guide the formation of reasonable judgments. Spillover might signal that people sometimes base political evaluations on thinly pertinent or even outright irrelevant evidence. Hence, one reason to explore experiential spillover is because doing so may generate new insights about the psychology of political decision making, and, more specifically, about a new facet of heuristic processing.

Second, at the institutional level, spillover would mean that some public sentiment toward certain public officials is partly beyond those officials’ realms of control. The implications cut both ways depending on whether spillover functions to share credit or blame. If it is primarily the former, political actors would benefit from a halo effect. If it is the latter, an institution may be placed in an untenable situation, with its public standing eroded due to someone else’s behaviors. Alternatively, spillover could bring mixed effects, producing a positive downstream influence on individuals who had good experiences and a negative influence on people with bad experiences. The result could be heightened love-them-or-hate-them polarization. These views of spillover hinge, of course, on the assumption that spillover of the form we have described even occurs. If it does, it may constitute an underappreciated antecedent of public opinion.

We focus on possible experiential spillover between police and courts in part because this project was motivated by our conversations with state judges. They expressed concern, informed by their own observations, that many Americans perceive police and courts as collaborators within the criminal justice system rather than as independent actors. The judges worried that people’s negative personal experiences with the police may lead them to evaluate judges and courts more critically, creating an external threat to judicial legitimacy. Although we explore experiential spillover from a broader perspective than the judges suggested, one of our goals is to determine whether empirical support can be found for the judges’ anecdotal observation that people’s interactions with police officers influence their appraisals of judicial actors.

In the next section, we develop a theory regarding the nature and impact of experiential spillover effects. The framework speaks to the conditions under which these effects most likely operate and to their probable implications. We then explain why mass attitudes regarding two actors in the criminal justice system, police and courts, present viable opportunities for the application of our theory. Subsequent sections report the design and execution of separate tests. Study One is a relatively brief exercise centered on analysis of 2012 survey data. Study Two offers a more expansive investigation focusing on data from a 2024 survey. Both studies generate insights regarding the occurrence, form, and scope of spillover effects.

The logic of experiential spillover

Under our conceptualization, experiential spillover takes place when people’s interactions with public officials or institutions influence how favorably they evaluate other officials or institutions. For such effects to warrant study, we must develop a case for why such spillover may occur, in what circumstances, and with what likely effects. We draw on research in psychology, including political psychology, to make this case, along with research on public opinion that has explored related forms of spillover.

Classic psychological research on heuristics helps us to understand how, why, and when spillover may happen. In work that will be familiar to many readers, Tversky and Kahneman (Reference Tversky and Kahneman1974) argue that in conditions of uncertainty, people often work their way through evaluative tasks by connecting an object under consideration to something they know well. With the representativeness heuristic, for instance, people may categorize a target by comparing it with their preexisting prototype. This is the process embodied in the saying “if it looks like a duck, walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, it’s a duck.” The availability heuristic is similar, except the comparison is made to concrete cases rather than to prototypes, as in “I doubt he’s a good singer. He looks exactly like Bob Dylan.”

Tversky and Kahneman’s research shows how heuristics may operate, but subsequent developments such as Petty and Cacioppo’s Elaboration Likelihood Model (Reference Petty and Cacioppo1986) and Chaiken’s Heuristic-Systematic Model (Reference Chaiken, Zanna, Olson and Herman1987) more fully address the why and the when. The answer, in brief, is that people often need to simplify judgmental processes when they lack the motivation and/or ability to engage the question at hand on a deeper and more deliberative level. Because of the efficiency it brings, heuristic processing potentially makes sense as a way to simplify an evaluative task that is otherwise too daunting.

Research on heuristics in political science is voluminous, and nearly always centered on connections between two sets of attitudes. We see this in early work on how people make sense of policies (e.g., Sniderman et al. Reference Sniderman, Hagen, Tetlock and Brady1986) and in subsequent research exploring the use, value, and effects of elite and party cues in heuristic processing (e.g., Arceneaux Reference Arceneaux2008; Broockman and Butler Reference Broockman and Butler2017; Fortunato and Stevenson Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2019; Fortunato et al. Reference Fortunato, Lin, Stevenson and Tromborg2021; Kam Reference Kam2005; Nicholson Reference Nicholson2012). Our approach has much in common with such studies, but we deviate in two respects. First, rather than revisiting processes in which individuals link attitudes to attitudes, we consider connections between experiences and attitudes. Second, whereas much of the past political science research has invoked an intra-actor approach (e.g., processes in which a person who believes a president or party generally has offered policy stances in line with the person’s values infers that similar consonance will exist on a new issue), we study inter-actor inferences—whether people’s experiences with one political actor shape their attitudes toward other actors.

The utility of heuristics has been debated within both psychology and political science. While Tversky and Kahneman emphasized judgmental errors, Sherman and Corty (Reference Sherman, Corty, Wyer and Srull1984) countered that errors are rare, and Wilson and Schooler (Reference Wilson and Schooler1991) showed that increased deliberation does not necessarily improve judgmental outcomes relative to those formed via heuristic processing. Likewise, political scientists alternately have highlighted the uneven utility of heuristic processing (e.g., Kuklinski and Hurley Reference Kuklinski and Hurley1994; Lau and Redlawsk Reference Lau and Redlawsk2001) or explained how such processing can bring valuable efficiency to low-information judgments (e.g., Fortunato and Stevenson Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2019; Fortunato et al. Reference Fortunato, Lin, Stevenson and Tromborg2021; Mondak Reference Mondak1993a, Reference Mondak1993b; Popkin Reference Popkin1991). A similar tension exists with experiential spillover. From the citizen’s perspective, experiential spillover may offer a means to make sense of political actors that otherwise would be difficult for many people to assess. Conversely, for the actors being evaluated—actors such as the judges who communicated their concerns to us—experiential spillover might be derisively characterized as a process in which people are comparing apples and ostriches.

We are not the first authors to invoke the concept of spillover in public opinion, nor the first to conceptualize spillover in terms of heuristic processing. A few studies have described the emergence of racial spillover effects on policy assessments during the Obama era (Benegal Reference Benegal2018; Tesler Reference Tesler2012, Reference Tesler2015, Reference Tesler2016). Using observational and experimental approaches, Tesler shows that Barack Obama’s election activated racial resentment among Americans who balked at the elevation of a person of color to the presidency. Consequently, when Obama publicized his policy stances, his association with those policies functioned as a negative cue, leading to heightened racial polarization of policy attitudes on matters such as health care (Tesler Reference Tesler2012) and climate change (Benegal Reference Benegal2018).

We see such cases of attitudinal spillover as aligning with broader research on how source cues operate. Individuals who view a source favorably or unfavorably draw on that predisposition to form or modify judgments about downstream targets—in these instances, policies—with which the source is associated. The key insights from the Tesler and Benegal studies pertain to how the predispositions toward the sources were formed and the distance between that basis and the policy under consideration (i.e., the strained reasoning needed to connect feelings of racial resentment to opinions about policy domains such as health care and climate change).

Other studies have explored dynamics closer to our conceptualization of spillover. Research on the antecedents of variation in congressional approval provides one example. Models of congressional approval often include presidential approval as a predictor. The motivating logic holds that, even though Congress and the presidency are billed as coequals in national politics, the president maintains such a preeminent position “that citizens’ perspectives on the president may profoundly inform and shape their evaluations of other institutions” (Patterson and Caldeira Reference Patterson and Caldeira1990, 31). Durr et al. (Reference Durr, Gilmour and Wolbrecht1997, 186) describe this link in terms consistent with spillover, writing “we anticipate that the public standing enjoyed (or endured) by the president will ‘rub off’ on Congress.” More recently, Zilis (Reference Zilis2021; see also Bartels and Kramon Reference Bartels and Kramon2022) demonstrates a similar linkage between the president and the Supreme Court, with the president’s ideology used to support inferences regarding the Court’s ideological orientation.

Although the focus of most research has been attitudinal rather than experiential, we envision heuristic processing operating similarly when cues emerge from personal interactions with public officials. We expect that personal experiences will function as information inputs that guide assessments of other actors. Two factors motivate a focus on police and courts. First, as a growing body of research (e.g., Anoll and Engelhardt Reference Anoll and Engelhardt2023; Peffley and Hurwitz Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2010; Weaver et al. Reference Weaver, Prowse and Piston2019) demonstrates, people’s direct experiences with actors in the criminal justice system affect their broader evaluations of that system. Second, because police officers and court officials are central players in the same sphere, experiential spillover is plausible despite their status as independent actors.

Heuristic processing offers the strongest basis for inference when the targets are related and exhibit positive interdependence. Coattail voting provides an example. Presidential candidates and their co-partisans running for Congress all seek elected office and the policy agendas they advocate are intertwined. Thus, the targets are related and interdependent. Similarly, connecting presidential approval to congressional approval is more sensible under unified rather than divided government because Congress is more likely to follow a president’s lead under unified government and more apt to emphasize its independence under divided government. Relative to these examples, experiential spillover linking police and courts arguably rests on shakier foundations. The actors are related in the sense that both operate within the criminal justice system, but they operate independently.

Experiential spillover between police and courts may occur in both directions. For example, for individuals who encounter the police frequently and courts seldomly, experiences with the police may shape assessments of courts. Conversely, for those individuals who interact regularly with courts but rarely with police, spillover may run in the opposite direction, with perceptions of the police influenced by personal experiences in court. Thus, we see it as important, within the bounds of what our data permit, that we test both causal paths.

Although experiential spillover between police and courts can operate in both directions, we expect that police experiences influencing court evaluations will be the more prevalent pathway. Three aspects of heuristic processing underlie this expectation. Heuristic processing should be most likely when 1) a judgment is required in a low-information context, meaning that the decision maker has need to turn to external cues for guidance; 2) an external cue provides an accessible information input; and 3) the external cue has plausible relevance to the present judgmental task.

Each of these factors favors police experiences shaping views of courts over court experiences shaping views of the police. First, most people have occasional encounters with police officers, but fewer regularly interact with court officials. In our 2024 survey, 74.0 percent of respondents reported recent interactions with the police, but only 38.3 percent with court officials. Hence, evaluating courts is a low-information endeavor for over two times more people than evaluating the police. Second, the police experiential cue is more accessible than the court cue. In our 2024 data, 62.9 percent of respondents with no personal court experiences had recent interactions with the police, but only 11.9 percent of respondents with no police encounters had personal engagement with court officials. Third, the police cue is of greater plausible relevance than is the court cue. Even if an encounter with the police does not lead to a court experience, nearly all police encounters—reporting a crime or an accident, witnessing a crime or an accident, being stopped for a traffic violation, and being stopped as part of a criminal investigation—have that potential. This creates opportunities for people to develop perceptual links between police and courts, notwithstanding those actors’ independence. Conversely, when court appearances are not preceded by encounters with the police, they often are for civil matters such as a divorce, a small claims suit, or jury duty in a civil case.Footnote 1 These offer tenuous information inputs to invoke when assessing the police.

Incorporating the logic outlined here, we test three expectations in two studies below; additional expectations specific to the second study will be detailed later.Footnote 2 First, people’s positive and negative experiences with the police will influence how positively or negatively they evaluate courts and court officials. This is our central spillover hypothesis. Second, the reverse effect—that experiences with courts and court officials will influence evaluations of police—will be substantively weaker than the police-to-court effect and/or statistically insignificant. As explained above, when court experiences precede evaluations of the police, it will be difficult for individuals to see judgments of the two actors as related. The possibility of substantively notable but statistically insignificant effects also acknowledges the empirical reality that few people have court interactions without police interactions. Third, we expect that police-to-court spillover will be strongest for individuals who have had personal experiences with police but have not had personal experiences with courts. For these individuals, evaluating courts is a low-information task in the sense that personal observations cannot be brought to bear on the judgment, and personal encounters with the police offer accessible grounds for engaging in heuristic processing to compensate for that relative dearth of court-specific information.Footnote 3

We test these expectations in two studies. This two-part approach enables not only immediate replication but also the opportunity to address important measurement considerations and possible risks of spuriousness.

Study One

Our initial study revisits data examined in Mondak et al. (Reference Mondak, Hurwitz, Peffley and Testa2017). In that article, the question was whether personal and vicarious experiences with police and courts affected people’s evaluations of those actors. Data came from a survey fielded in the state of Washington in 2012. Strong direct experiential effects were found, but tests exploring possible spillover between police and courts were not reported. Instead, only police experiences were considered as possible influences on respondents’ assessments of the police and only court experiences were used as predictors of court evaluations. These data provide us with the opportunity for an initial test of our experiential spillover thesis.

Data and method

The 2012 Justice in Washington State Survey (Mondak et al. Reference Mondak, Hurwitz, Peffley and Testa2017) is an internet survey administered by YouGov. There are 1,524 respondents, including oversamples (average N = 304) of African Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos.Footnote 4 The survey included multiple questions about respondents’ experiences with and perceptions of police and courts, along with several experimental vignettes regarding other aspects of the criminal justice system.

Our dependent variables mirror those in Mondak et al.’s Table 3. Police Evaluations averages a respondent’s answers to two questions, both using six-point scales, that asked how often the police treat people with respect and make fair, impartial decisions (mean = 2.40; s.d. = 1.08). Court Evaluations follows the same structure, but with questions pertaining to courts (mean = 2.64; s.d. = 1.07). Whereas Mondak et al. focused on whether people’s personal and vicarious experiences with each actor affected how favorably that actor was perceived, we are interested in whether personal experience with one of the actors influences perceptions of the other actor.

The central independent variables also draw on two pairs of questions, this time using five-point scales. Respondents were asked how many times they had been treated disrespectfully and unfairly by the police, with each form of treatment measured on a 0 (never) to 4 (seven or more times) scale. No time frame was specified for these encounters; in Study Two, we ask respondents to focus on interactions that took place within the past five years. Note that the Washington survey recorded only bad experiences; we measure both bad and good experiences in Study Two. Police Experience is formed by averaging a respondent’s answers to the “treated disrespectfully” and “treated unfairly” items, producing a 0 to 4 scale (mean = 0.65; s.d. = 0.89). Court Experience incorporates data from the parallel items regarding disrespectful and unfair treatment in court (mean = 0.25; s.d. = 0.63). We include both experience variables as predictors for both dependent variables, along with many of the same covariates as Mondak et al. (Reference Mondak, Hurwitz, Peffley and Testa2017): age, gender, education, three indicators to account for race and ethnicity, partisanship, and an indicator for respondents who did not express a partisan preference. Descriptive statistics for all variables are reported in the Appendix.

Expectations

With the caveat that the 2012 data only enable us to identify respondents’ self-reported bad experiences with police and courts, we are able to test all three expectations detailed above: 1) that respondents’ experiences with the police will shape their assessments of courts; 2) the possible reverse effect in which experiences with courts influence views of the police, while conceivable, should be substantively weaker and/or statistically insignificant as compared with the police-to-court effect; and 3) the impact of police experiences on court evaluations should be greatest for respondents who did not report personal experience with courts.

Results

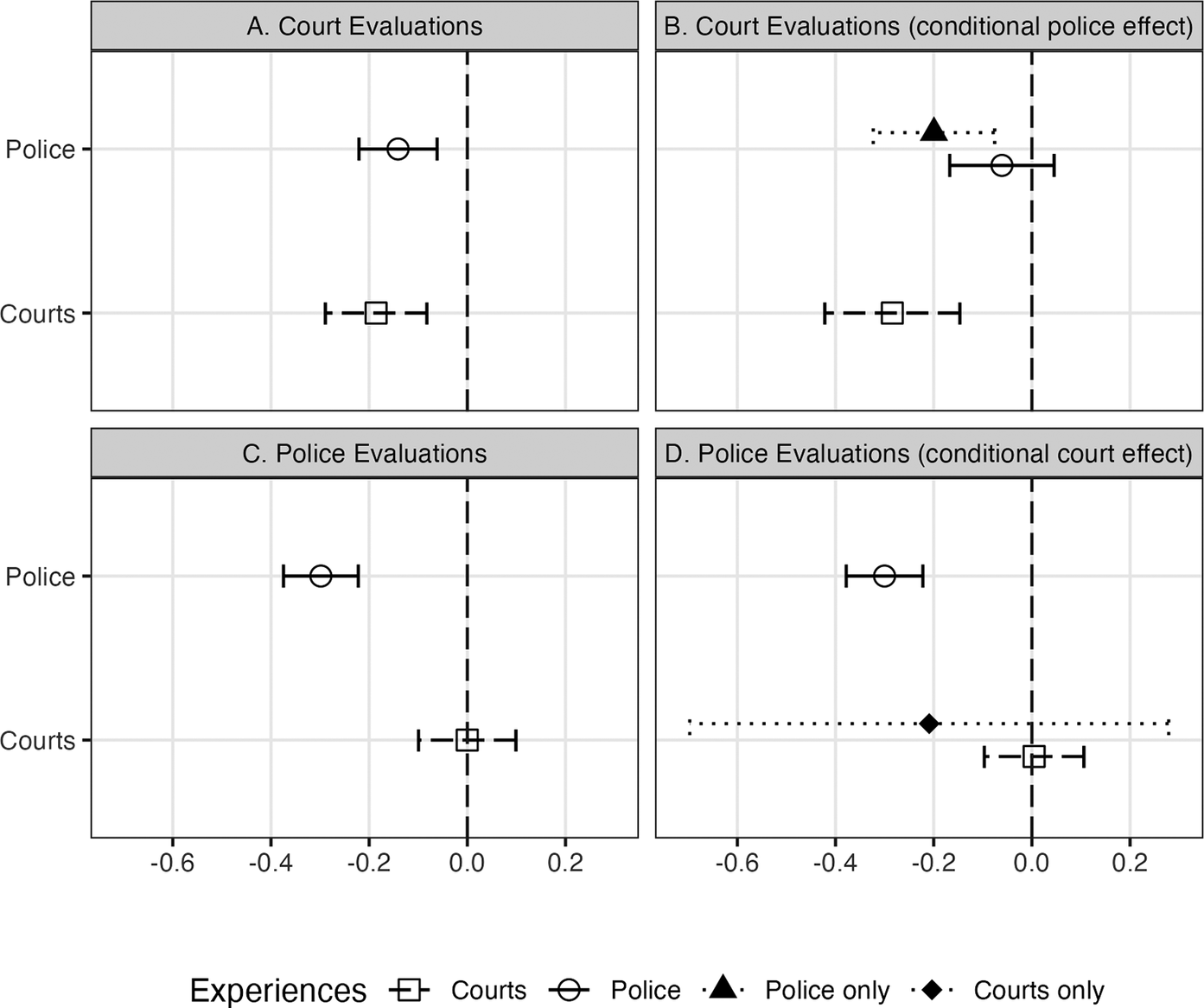

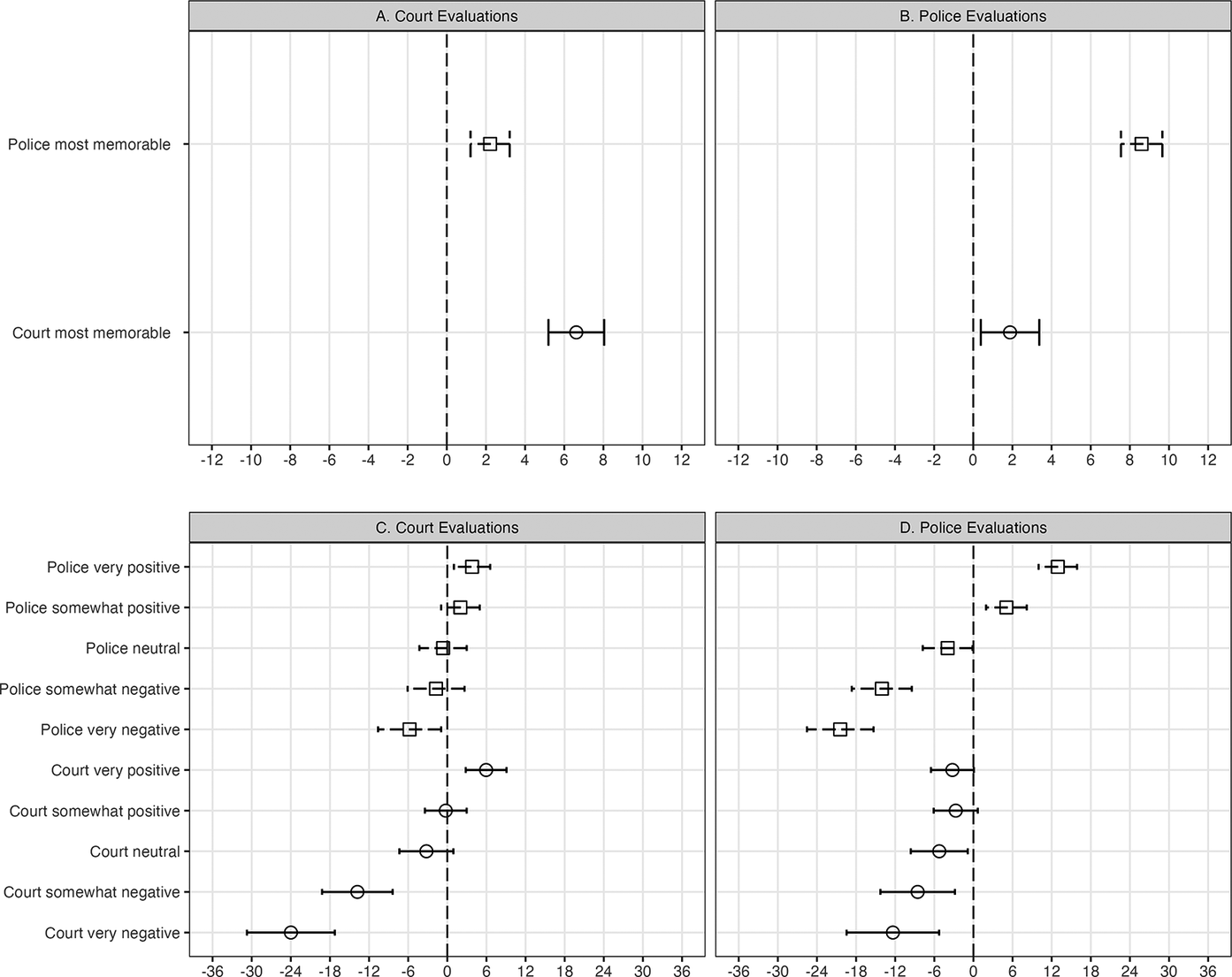

Coefficient plots derived from four WLS regression models are reported in Figure 1; tables with full results of all models are included in the Appendix. Panels A and B include police-to-court estimates that speak to our core spillover thesis (Panel A) and our secondary expectation that the influence of police experiences on court evaluations will be greatest for individuals who reported no personal interactions with court officials (Panel B). Panels C and D display results for parallel tests exploring the possible impact of court experiences on evaluations of the police.

Figure 1. Tests for Spillover Effects of Court and Police Perceptions, 2012.

Note: The panels display point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the effects of police and court experiences on evaluations of police and courts. These are weighted least squares models using data from the 2012 Justice in Washington State Survey. The full model specification is shown in Table 13 of the Appendix. Panel headings denote the dependent variables (evaluations of courts and police) and labels on the horizontal axis refer to respondents’ personal experiences with police and courts. In Panel B and Panel D, spillover effects are differentiated for respondents who did and did not have personal experience with the target of the evaluation; for example, the top estimate in Panel B shows the effect of experience with the police on evaluations of courts for respondents who did not have personal experience with courts, and the estimate immediately below is the police-to-court effect for respondents who did have personal court experience.

Results in Panel A corroborate our central spillover hypothesis. The negative effect for police experiences (the top estimate in Panel A) indicates that negative interactions with the police lead respondents to downgrade their assessments of courts. The effect is substantively strong and statistically significant (p < .001). The –0.14 coefficient suggests that, on average, a person who reported highly negative experiences with the police would rate courts more than a half-point lower than would a person with no negative police experiences. The magnitude of this effect is three-fourths that of the influence of respondents’ personal experiences in court on their evaluations of courts and judges (b = –0.19).

Panel C reveals an absence of spillover from court experiences to police evaluations (b = 0.00). This comports with expectations. Moreover, the zero effect (as opposed to a statistically insignificant negative effect) is consistent with the possibility that respondents with court experiences failed to perceive a link between those experiences and the police. Panel C also shows that people’s interactions with the police sharply shaped their assessments of the police (b = –0.30), with a substantive impact nearly 60 percent greater than that for the court-to-court effect displayed in Panel A.

Estimates in Panel B and D align well with our third expectation. In Panel B, police experiences produce modest (–0.06) and statistically insignificant effects on court evaluations among respondents who have had personal interactions in court, but more substantial effects for respondents without court experience (–0.20). This supports the interpretation of experiential spillover as an example of heuristic processing because police experiences appear to matter the most when respondents need help in completing the judgmental task at hand. In Panel D, the court-to-police estimate for respondents who have had only court prior experiences (–0.21) is nearly identical to the police-to-court effect, although the court-to-police estimate is statistically unreliable because this group includes fewer than two percent of the study’s respondents.

Discussion

Results from Study One provide initial support for our thesis. People’s experiences with the police shape how favorably they evaluate courts, and this effect is strongest among individuals who lack personal experience with courts. Experiential spillover exists, and its properties are consistent with the logic of heuristic processing in that police experiences appear to be something of a fallback basis for evaluating courts, a criterion that is invoked primarily when individuals lack a personal basis to evaluate courts directly.

Although the Study One results are provocative, they are not dispositive. First, the data are from 2012, warranting an attempt to replicate the findings with more recent data. Second, while we have no reason to believe that Washington is atypical, a retest with a national sample may be informative. Third, the Washington study may tell only part of the experiential spillover story. The survey asked respondents solely about bad experiences, but many people have good experiences with police and courts. Accounting for the full range of experiences would enable a more comprehensive exploration of spillover. Lastly, some robustness tests seem sensible. The Washington survey measured experiences with modified count items, an approach that weights all experiences equally. This may be appropriate, but it should not necessarily be presupposed. Thus, in Study Two, we explore the utility of an alternate measure. Likewise, with the Washington survey, it is difficult to rule out response effects and psychological dispositions as possible causes of spuriousness. It may be that response tendencies consistently drive some people to assign low marks—in the present case, to relay more negative experiences and to issue lower ratings to police and courts—while other respondents do the opposite. Similarly, high levels of negative affect may underlie both why some respondents report a preponderance of negative experiences and why they assign courts and police low ratings. Our second study includes measures that enable us to test whether core results persist when efforts are made to account for such possible causes of spuriousness.

Study Two

We conducted a second study to enable further examination of possible experiential spillover. Our goals were to facilitate replication of Study One while incorporating design features for more rigorous and multifaceted tests of whether and how spillover operates.

Data and methods

The second study utilizes data we gathered via an online survey fielded in April 2024. The survey has a nationally representative sample of 1,500. Data acquisition was administered by YouGov. We designed items pertaining to police and courts with two objectives in mind. First, we developed questions that would enable us to replicate Study One. For this, we required items addressing respondents’ negative experiences with police and courts along with items measuring evaluations of those actors. Second, we sought to move beyond that initial measurement strategy in several manners: running tests with data from a national sample, incorporating data on negative affect levels and related response effects to diminish the chance that findings are the spurious products of unmeasured psychological factors, measuring both positive and negative experiences, and examining an alternate experiential measure.

To maximize comparability between actors, we used standard 0 to 100 feeling thermometers to provide data for our dependent measures. The feeling thermometer items, which were in the sixth section of the survey, directed respondents to rate “police in your community” and “judges and court officials in your community.” The same battery included nine other feeling thermometer prompts, including four national actors: Donald Trump, Joe Biden, Democrats in Congress, and Republicans in Congress.

Questions measuring respondents’ police and court experiences were asked in the survey’s second section.Footnote 5 We used three questions to measure police experiences and three to measure court experiences. Respondents were randomly assigned to be asked the police or court questions first. For both sets of questions, we began with a prompt that signaled the general types of experiences we had in mind. The prompt included some interactions that most often would be seen as positive and others that usually would be perceived as neutral or negative. For the police question, for instance, the prompt read:

Some people interact with local police on a regular basis while other people do so only occasionally. These interactions can occur for many reasons, such as when police officers help us after an accident or a crime has occurred, when they interview us because we have witnessed an accident or a crime, or when they suspect us of having committed a traffic violation or some other unlawful action.

Following this prompt, respondents were asked how many times in the past five years they had had positive experiences, defined as including “instances in which (a police officer/judges or court officials) treated you politely, treated you fairly, (was/were) helpful to you, or performed effectively.” The seven-point scales offered options ranging from zero to six or more times (police mean = 1.85, s.d. = 1.91; court mean = 0.74, s.d. = 1.35). The next item used an identical format to ask about negative experiences (police mean = 0.70, s.d. = 1.36; court mean = 0.39, s.d. = 1.02). Lastly, all respondents who reported at least one experience were asked to think about their single most memorable encounter and rate it on a five-point scale that ranged from very negative (–2) to very positive (2) (police mean = 0.61, s.d. = 1.12; court mean = 0.31, s.d. = 0.83). These “most memorable” items provide an alternate measurement strategy with which we can explore the possibility that the most salient incidents exert the greatest influence on downstream evaluations.

The survey’s opening section included four seven-point self-assessment items. Two measured negative affect, enabling us to form a scale used below as a hedge against possible spuriousness. The items are “I like to look on the bright side of things” (reverse coded) and “my friends say I am a negative person.” The two items are correlated at a level of r = 0.39, and the scale formed by averaging the two items has a mean of 5.53 (s.d. = 2.80). If respondents’ chronic levels of negativity lead them to dwell on prior negative encounters with police and courts and also to award lower evaluative ratings as a matter of course, then omission of negative affect could result in artifactual exaggeration of the link between experiences and evaluations. Our feeling thermometer battery offers a second approach to this same issue. Respondents who, across parties, consistently award high or low ratings when assessing national political actors may be exhibiting a trans-situational response tendency. A respondent’s mean rating for the four partisan national-level actors—Donald Trump, Joe Biden, Democrats in Congress, and Republicans in Congress—should be party-neutral. Hence, a four-item scale using those ratings enables us to account for spuriousness caused by response effects (mean = 45.44, s.d. = 16.57).

Expectations

Our first three expectations mirror those from Study One: negative experiences with the police will correspond with unfavorable evaluations of courts, negative experiences with courts will be weakly related or unrelated to evaluations of the police, and police-to-court effects will be strongest for respondents with no negative court experiences. Apart from moving from a state sample to a national sample, slightly modifying the experiential count variables, and using feeling thermometers as dependent measures, our first tests match closely those in Study One.

We also explore several new matters. First, we expect negative affect to relate to our dependent variables, a circumstance that might lead to spurious effects for our experiential variables if measures of negative affect are not included as covariates. Hence, we will contrast models with and without affect and response set measures—our two-item negative affect scale and a four-item feeling thermometer measure of each respondent’s mean rating for four national political figures—to determine if the core experiential effects recorded when these variables are omitted partly reflect a spurious link. If, as we expect, some people characteristically tend to assign relatively high or low ratings across evaluative contexts, then moving from the omission to the inclusion of these variables should reduce effect sizes for the experiential measures. In the extreme, if adding these variables results in a substantial or even complete erosion of spillover effects, then the theory we have proposed would be undercut.

Our second new expectation proposes a doubling of the initial hypotheses. Due to the construction of the 2012 Justice in Washington State Survey, we could only explore the possible effects of negative experiences. We hypothesize that similar spillover also occurs due to positive interactions: people’s good experiences with the police are expected to influence assessments of courts, and positive court experiences are expected to yield similar but weaker influence on evaluations of the police. Because we hypothesize spillover effects for both positive and negative encounters, a follow-up question is whether we should expect those to be of comparable magnitude. In tests of vicarious effects—the possible impact of a friend’s or acquaintance’s good or bad experiences on the respondent’s judgments—evidence of a negativity bias was found (Mondak et al. Reference Mondak, Hurwitz, Peffley and Testa2017). Bad experiences mattered more than good ones. Given that finding together with the general prevalence of a negativity bias in evaluative contexts (e.g., Baumeister et al. Reference Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer and Vohs2001; Canache et al. Reference Canache, Mondak, Seligson and Tuggle2022; Skowronski and Carlston Reference Skowronski and Carlston1989), negative experiential effects should be substantively stronger than positive ones.

Lastly, we include an alternate measure of experience for exploratory purposes. Our core measures mirror the count approach used by Mondak et al. (Reference Mondak, Hurwitz, Peffley and Testa2017). That method engages the possibility that multiple experiences produce a cumulative impact on respondents’ evaluations. The alternate measure focuses on each respondent’s most memorable encounter. Our intuition is that not all experiences are equal. For instance, a person who was issued a warning from one police officer for rolling through a stop sign and was pulled from a burning car by another officer would probably not weight those experiences equally.

Results

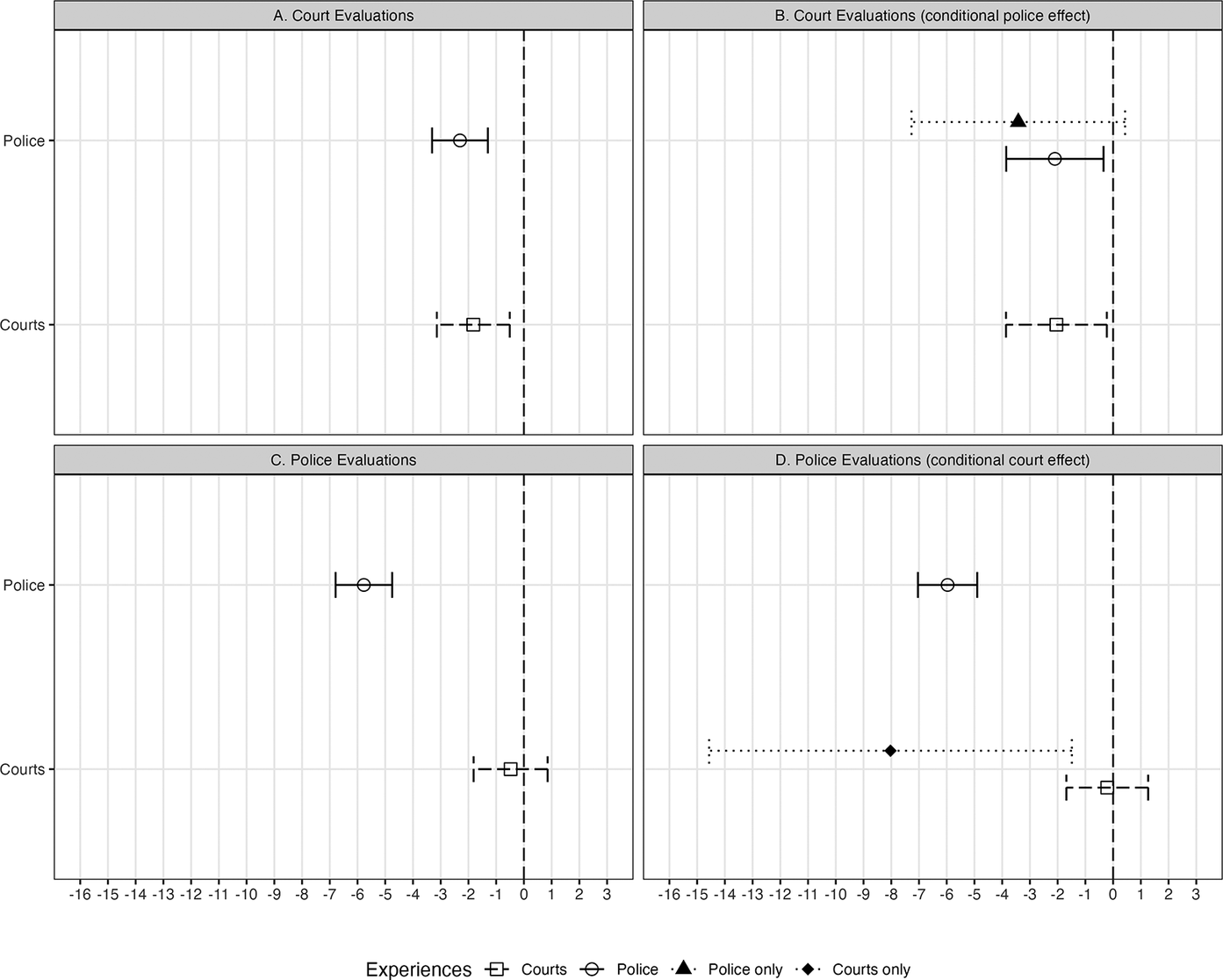

Analyses begin with an attempt to replicate results from Study One. There, we saw that people’s negative experiences with police influenced their evaluations of courts, but there was little evidence that experiences with courts exerted comparable impact on evaluations of police. We revisit this pattern in two steps, with relevant coefficient plots shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Tests for Spillover Effects of Court and Police Perceptions, 2024.

Note: The panels display point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the effects of police and court experiences on evaluations of police and courts. These are OLS models using data from a 2024 YouGov survey. The full model specifications are shown in Tables 15 and 16 of the Appendix. Panel headings denote the dependent variables (evaluations of courts and police) and labels on the horizontal axis refer to respondents’ personal experiences with police and courts. In Panel B and Panel D, spillover effects are differentiated for respondents who did and did not have personal experience with the target of the evaluation.

Figure 2 includes findings from four models comparable to those examined in Figure 1. Results for court evaluations are displayed in Panels A and B and results for police evaluations are shown in Panels C and D. For each dependent variable, the panel on the left tests for overall experiential effects while the panel on the right splits the spillover variable on the basis of whether the respondent reported experience with the target institution.

Estimates for police-to-court effects in Panel A provide support for our central spillover thesis. As in Study One, negative police experiences correspond with statistically significant decreases in feeling thermometer ratings of local courts. A second similarity with Study One is seen in Panel C, where the court coefficient is statistically insignificant and has a value near zero. Figure 2 does not offer clear support for our third expectation, which is that police-to-court spillover will be most pronounced for respondents who lack court experience. In Panel B, police-to-court spillover is slightly stronger among respondents with no prior court experience, but the gap is substantively minimal and statistically insignificant. Conversely, the court-to-police spillover effect (Panel D) exceeds conventional levels of statistical significance only for individuals who had negative encounters exclusively with courts. As in Study One, there are very few such individuals in the study (fewer than 4 percent of respondents in the 2024 sample), yielding estimates with very wide confidence intervals. With that caveat noted, the same pattern was observed in Figure 1, suggesting that there perhaps is something unique about decision-making processes among those rare individuals who have had negative experiences in court while never engaging with the police.

Because our studies use cross-sectional data, we have noted that the possibility must be entertained that what we have identified as spillover effects instead constitute a spurious connection. The most plausible source of spuriousness is negative affect. People who exhibit chronic negativity and/or systematically answer survey questions by choosing more negative rather than positive response options may have overstated the severity of their negative police experiences while also issuing low ratings to courts. We explore this with our 2024 data by rerunning Figure 2’s models with measures of negative affectivity and national feeling thermometer averages added as covariates. The results are shown in Figure 3.

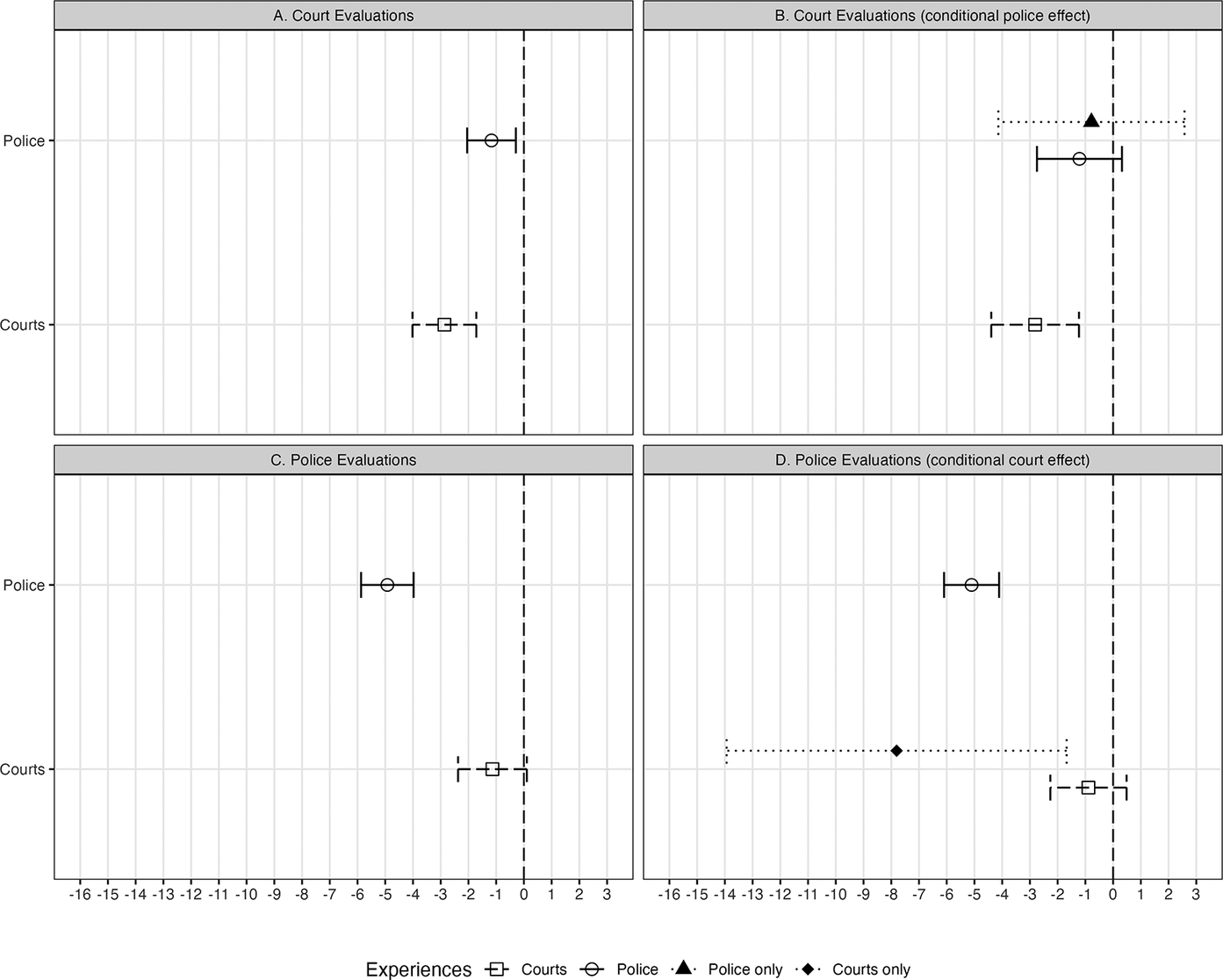

Figure 3. Possible Spuriousness in Tests of Spillover Effects of Court and Police Perceptions, 2024.

Note: Models are identical to those in Figure 2 except that negative affectivity and the respondent’s average feeling thermometer rating of four national political targets have been added as covariates. The panels display point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the effects of police and court experiences on evaluations of police and courts. These are OLS models using data from a 2024 YouGov survey. The full model specifications are shown in Tables 17 and 18 of the Appendix. Panel headings denote the dependent variables (evaluations of courts and police) and labels on the horizontal axis refer to respondents’ personal experiences with police and courts. In Panel B and Panel D, spillover effects are differentiated for respondents who did and did not have personal experience with the target of the evaluation.

In Panel A, police-to-court spillover remains significant (p < .01), but the –1.17 coefficient is barely half as large as the –2.31 estimate in Panel A of Figure 2. Conversely, court-to-police spillover strengthens with addition of the new covariates, rising from an insignificant –0.48 in Panel C of Figure 2 to a marginally significant (p < .08) –1.13 in Panel C of Figure 3.

Substantively, the two spillover effects are nearly identical. Hence, inclusion of the covariates leaves support for our central spillover thesis intact, but we no longer have definitive ground to claim that the police-to-court effect is stronger than the court-to-police effect. The police effect reaches a higher level of statistical significance because many more people have personal interactions with the police than with courts, but the effect sizes are indistinguishable. Lastly, the estimates in Panel D once again indicate that court-to-police spillover is most impactful among the few respondents who have had personal interactions only with courts.

The coefficient estimates for negative affectivity and respondents’ average feeling thermometer ratings of national political figures (see Tables 17 and 18 in the Appendix) are noteworthy for their magnitude. All eight coefficient estimates are statistically significant at the p < .001 level, and they are substantively large. We see this as strong evidence that it is important to account for survey respondents’ characteristic response patterns so that we can minimize the risk of spuriousness.

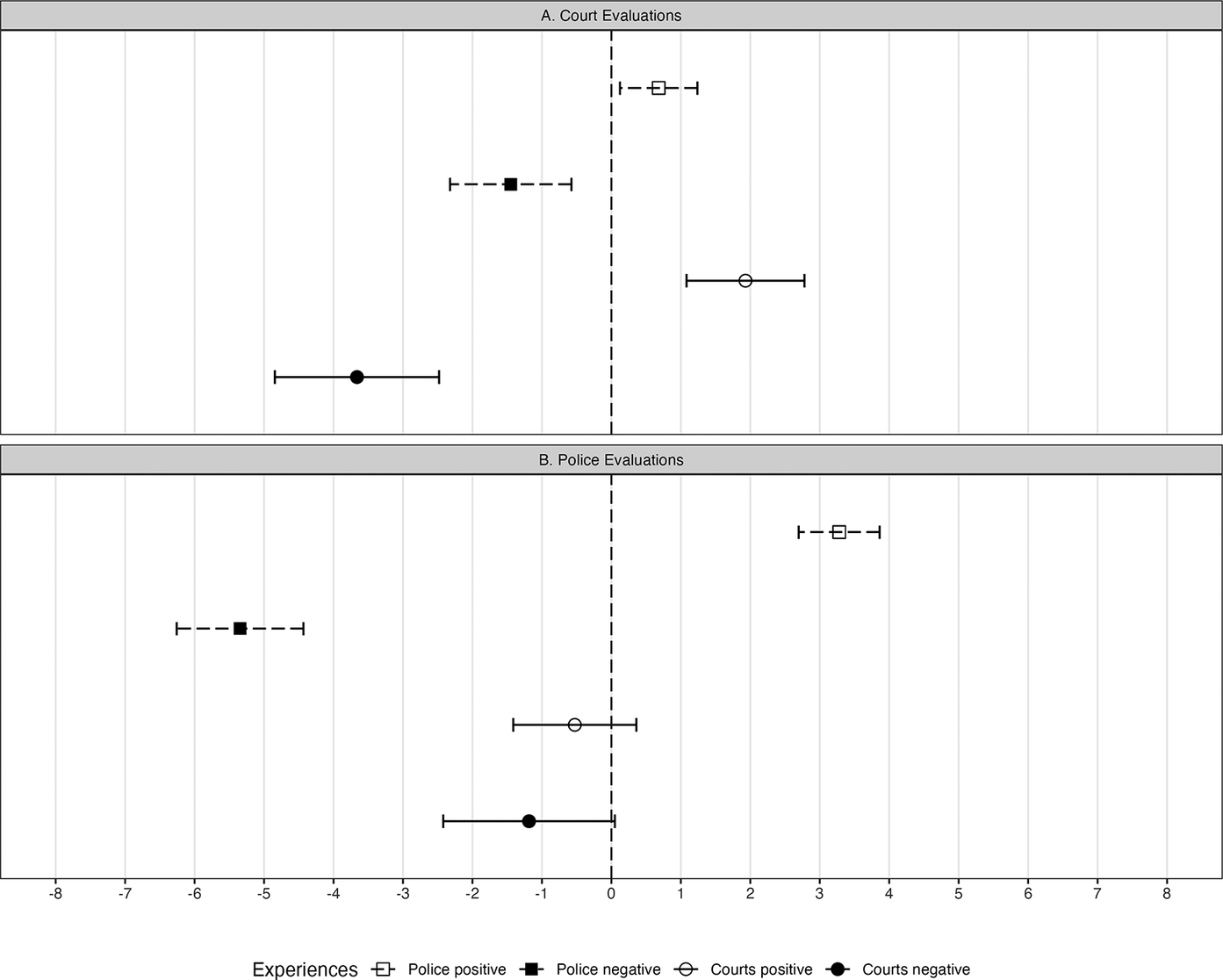

Given the impact of the new covariates, these are retained in our final two tests. The first considers whether our exclusive focus to this point on respondents’ negative experiences with police and courts may miss a key aspect of experiential spillover. People routinely have positive experiences in court and when interacting with police officers. We noted above that the negativity bias may mean that bad experiences are more impactful than good ones, but it does not follow that positive experiences will be irrelevant. The 2012 Washington survey did not measure positive encounters, but our 2024 survey did, and respondents reported roughly twice as many positive interactions with police and courts as negative ones (see Appendix Table 3). Thus, we estimated new versions of the models in Panel A and Panel C of Figure 3, this time including measures of both positive and negative encounters. The results are displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Tests for Spillover Effects of Positive and Negative Experiences.

Note: Models are identical to those in Panel A and Panel C of Figure 3, except positive experiences have been added as independent variables. The panels display point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the effects of police and court experiences on evaluations. The models are OLS using data from the 2024 YouGov survey. The full model specifications are shown in Table 19 of the Appendix.

In Panel A of Figure 4, the police-to-court and court-to-court effects align with expectations in that positive and negative experiences both shape evaluations of courts, but negative experiences produce substantively stronger effects than do positive ones. Coefficients for police effects are –1.45 for negative police experiences and 0.68 for positive encounters. For court experiences, the corresponding effects are –3.66 and 1.93. These results corroborate our intuition that we should account for the possible impact of both positive and negative experiences, but the findings also match expectations founded on a wealth of past research establishing that a negativity bias operates in many judgmental processes. Results in Panel B are mostly but not entirely consistent with those in Panel A. The key difference is that positive court experiences do not influence assessments of the police, with the relevant coefficient being both statistically insignificant and incorrectly signed. As in Figure 3, negative court experiences modestly affect feelings toward the police (b = –1.19, p < .06). The police-to-police effects match expectations, with strong, statistically significant impact seen for all experiences, but with negative effects (b = –5.35) being substantially more pronounced than positive ones (b = 3.28).Footnote 6

Thus far, we have measured respondents’ experiences with count variables. As an alternative, respondents on the 2024 survey were asked to contemplate their most memorable police and court experiences, and to rate those on five-point scales ranging from very positive (2) to very negative (–2). We tested two strategies for incorporating these measures in our models. In the first, we simply include the two scales, Memorable Court Experience (mean = 0.31, s.d. = 0.83) and Memorable Police Experience (mean = 0.61, s.d. = 1.12). Respondents with no experiences are coded as 0, and separate indicator variables, No Court Experience and No Police Experience, differentiate between respondents who had neutral experiences and those with no experiences. This specification has the benefit of parsimony, but it prevents capture of a possible negativity bias. Thus, the second specification includes ten indicator variables representing the five ratings of memorable court and police experiences.

Coefficient plots for these alternate specifications of personal experience are reported in Figure 5. Panel A shows experiential spillover from police experiences to court evaluations. Panel B depicts only slightly weaker spillover from court experiences to police evaluations (the spillover coefficients are 2.21 and 1.88 in Panels A and B, respectively). Figure 5’s bottom two panels report effects for each level of experience, from very positive to very negative. Sensibly, the largest impacts are associated with very good and very bad experiences. Within each of the four groups of effects (the influence of court experiences on court evaluations, the influence of police experiences on court evaluations, and so on), very negative experiences yielded the strongest substantive impact, providing further evidence of a negativity bias. The effects of court and police experiences deviate from one another in one noteworthy manner. Positive police experiences lead individuals to rate both courts and the police more favorably as compared to respondents with no police experiences. Conversely, only very positive court experiences appear to lead respondents to upgrade their assessments of courts. Moreover, all court experiences, including positive ones, correspond with modest to sharp decreases in warmth toward the police. Put differently, good police behavior creates a halo effect that benefits courts, but good court experiences seemingly do not lead to a similar halo effect that benefits the police.

Figure 5. Spillover Effects by Most Memorable Experiences with Police and Courts.

Note: The panels display point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the effect of a respondent’s most memorable police and court experiences on evaluations. The models are OLS using data from the 2024 YouGov survey. The full model specifications are shown in Tables 20 and 21 of the Appendix.

Discussion

Collectively, results from Study Two corroborate multiple aspects of findings in Study One while illuminating several additional matters. We have seen that experiential spillover is not limited to the state of Washington; the magnitude of possible spillover effects may be overstated if covariates are not included to guard against likely sources of spuriousness; spillover can emanate from both positive and negative experiences; substantively stronger effects emerge from negative rather than positive encounters, indicating a negativity bias; and corroboration of core findings may be possible with use of alternate measures such as ones that focus on the valence of respondents’ most memorable experiences.

Our central spillover hypothesis has amassed consistent support. The evidence is clear that experiences with the police influence people’s appraisals of courts. Our second expectation was that police-to-court spillover would be more impactful than court-to-police effects. Consistent with this, only police-to-court spillover was detected for positive experiences. However, police-to-court and court-to-police spillover effects were found to be of virtually identical magnitude for negative experiences. Lastly, in Study Two court-to-police spillover is most prominent among the few individuals who had had interactions only with courts, but that same pattern was not observed for police-to-court spillover.

Conclusion

In this study, we have proposed that people’s personal experiences with public officials may bring rippling effects that travel a considerable distance from those initial personal interactions. Our approach has integrated insights from two research traditions. First, drawing guidance from research on heuristic processing, we have argued that people will gain judgmental efficiency by connecting that which they know well to that which is more novel or unfamiliar. Second, informed by research on people’s views of the criminal justice system, we have focused on the pivotal role of personal experience as a determinant of downstream attitudes. Merging these perspectives led us to posit that in some instances public opinion may reflect the occurrence of experiential spillover effects, a class of influences mostly unrecognized in previous scholarship. Analyses from two studies corroborate that such spillover occurs, its core elements are largely consistent with the logic of heuristic processing, and its observable effects exhibit considerable substantive strength.

Our most consistent findings indicate that people’s personal encounters with one set of public officials, local police officers, strongly shape how favorably they assess a different set of public officials, judges and other local court personnel. This is the precise effect posited to us by state judges who worried that declining judicial legitimacy was accelerating because people who were having negative experiences with the police were responding by downgrading their assessments of courts. Seen in this context, state and local courts will likely not welcome this study’s findings. Judges who see themselves as striving to maintain independence and neutrality presumably would be frustrated that citizens’ evaluations of local judicial actors hinge partly on whether people have had positive or negative interactions with local police—circumstances over which judges have no control. As analysts, we see similar cause for concern.

Three issues suggested by our analyses warrant particular attention. First, as often occurs in research on attitude formation, our findings speak only indirectly to the full inferential process that connects information inputs (in the present case, personal experiences) to outputs (judgments regarding local police and courts). Categorization is central to heuristic processing. In the current case, one possibility is that respondents formed vertical, or hierarchical, linkages. This would imply that respondents conceive of police and courts as subcategories beneath an umbrella grouping such as “local government employees” or “the criminal justice system.” In this scenario, police experiences would travel upward vertically to shape individuals’ views of the superordinate category, and then back down to other subcategories such as local courts. Although our data do not facilitate full testing of this structure, two complementary strategies could be applied in future research. Mediation analysis could be used to explore whether one or more superordinate categories mediate the effects of experiential spillover. Likewise, mixed method approaches that include open-ended items would facilitate inspection of how survey respondents explain their reasoning, potentially offering direct evidence of the presence or absence of hierarchically structured thought processes (for an example focused on survey respondents’ issue rationales, see Hibbing et al., Reference Hibbing, Mettler, Mondak and Raynalforthcoming).

Second, although it seems implausible that experiential spillover will be of identical magnitude for all individuals, we made only minimal progress in identifying sources of individual-level variation. It may be that we were right to conceive of spillover in terms of heuristic processing, but failed to pinpoint the key factors that demarcate for which individuals or in which circumstances spillover will be most prominent. Alternately, it could be that, much like with source credibility effects (e.g., Mondak Reference Mondak1990; Petty and Cacioppo Reference Petty and Cacioppo1984; Petty et al. Reference Petty, Cacioppo and Schumann1983), personal experiences with public officials fulfill a heuristic function for some individuals while serving as evidence that is carefully processed and applied by others.

Third, as with many understudied phenomena, questions of measurement require additional consideration. We are confident in concluding that both positive and negative experiences should be represented in research on experiential spillover. However, our count-based and “most memorable” measurement approaches performed similarly, indicating that follow-up work may be needed to determine whether one of these or some other method will best facilitate discovery of further insights about this component of opinion formation.

Most fundamentally, this study’s results demonstrate that people readily call to mind personal encounters with government officials, and the most positive and negative of those encounters exert clear effects on respondents’ broader evaluations. Viewed in the context of the nameless, faceless character of many public agencies, it perhaps should be unsurprising that interactions with actual government officials are so impactful (Canache et al. Reference Canache, Cawvey, Hayes and Mondak2019; Cramer and Toff Reference Cramer and Toff2017). These findings add a new element to our understanding of the bases of public opinion. Many accounts of public opinion posit a top-down structure anchored by attitudes toward major national actors such as the president, Congress, and the Democratic and Republican parties. Current findings reveal a complementary bottom-up dynamic, one in which broader judgments gain shape partly as a function of politics on the street. The collective force of these micro-level effects remains to be determined. If encounters with police officers shape judgments about other actors in the criminal justice system, then might people’s views of government and their corresponding perceptions of efficacy and trust also be influenced by brief but memorable exchanges with school board members, party canvassers, civil service employees, and local elected officials? Identification of further such experiential spillover may add a key facet to our understanding of how and how well citizens utilize the information available to them to monitor and assess the political sphere.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/jlc.2026.10013.

Acknowledgments

Data for Study One were gathered under our supervision with the support of the Washington State Supreme Court Minority and Justice Commission, and the State of Washington Administrative Office of the Courts–Washington State Center for Court Research. We thank all involved in this project, and especially Carl McCurley, for their contributions. Data for Study Two were gathered with financial support from the James M. Benson Fund at the University of Illinois. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful and constructive suggestions.