Introduction

Although personalisation aspects are evident across welfare sectors, they are most fully realised in disability policy. Elements such as individually tailored support and personal budgets have reshaped services for persons with disabilities and, in doing so, have reoriented provider markets and support services to make them more human-centred. These reforms are being deployed across various states, including those categorised as having different welfare regimes (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990). Second, they have an ambiguous heritage, emerging both from disability rights campaigns and from neo-liberal market reforms, making them hard to categorise using only conventional regimes (e.g., social democratic, liberal, conservative). While personalisation is a natural fit within the liberal welfare regime, integrating into a Mediterranean-social-democratic welfare regime is relatively new and less intuitive (Gal, Reference Gal2010). Understanding this integration’s theoretical and empirical implications is essential to support the development of more effective policy designs. This study focuses on the impact of an Individualised Budgeting (IB) programme employing Gilbert and Terrell’s theoretical analysis framework on personalised disability care market-shaping in a Mediterranean-social-democratic welfare regime case study.

Literature review

Conceptualising personalisation in social care

Countries that are parties to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) must ensure that people with disabilities have equal rights and opportunities in all areas of life. They are required to provide legal, policy, and procedural frameworks tailored to individuals’ unique needs, emphasising personalised support.

The concept of personalisation in social care and disability services is theoretically multifaceted, marked by inherent contradictions and competing interpretations. At its core, personalisation entails designing services around users’ individual needs, rather than compelling them to conform to standardised provisions (Howlett, Reference Howlett2011). Mladenov et al. (Reference Mladenov, Owens and Cribb2015) conceptualised personalisation as a hybrid construct oscillating between marketisation and social justice paradigms. The former frames personalisation in terms of economic efficiency, competition, and consumer choice, while the latter emphasises user empowerment, democratisation of decision-making, and resistance to paternalistic control. Importantly, personalisation is described as an ‘empty signifier’, encompassing divergent meanings such as autonomy, cost-effectiveness, privatisation, and user involvement, thereby serving conflicting political agendas while obscuring deep tensions between neoliberal and emancipatory frameworks. Expanding on this, Pozzoli (Reference Pozzoli2022) identified two coexisting practical approaches: a narrow focus on choosing between existing providers, and a broader model that supports individualised planning and professional guidance to facilitate meaningful choice.

Personalisation is not a fixed policy but a person-centred framework for welfare systems, often implemented through mechanisms like individualised budgets (Needham, Reference Needham2011; Kaehne et al., Reference Kaehne, Beacham and Feather2018). Models like Money Follows the Person (MFP) in the US and Personal Budgeting (PB) in the UK and Australia allow individuals to choose services that align with their unique needs and goals. Decision-making can be done independently or with support, depending on the individual’s circumstances (Leplege et al., Reference Leplege, Gzil, Cammelli, Lefeve, Pachoud and Ville2007; Blanck, Reference Blanck2023).

While IB programmes have been widely recognised for their potential benefits, a critical examination of the evidence reveals both strengths and limitations. Systematic reviews indicate improvements in users’ quality of life, increased satisfaction with services, and enhanced autonomy through greater control over care decisions and daily routines (Micai et al., Reference Micai, Gila, Caruso, Fulceri, Fontecedro, Castelpietra and Scattoni2022; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Blaise, Weber and Suhrcke2022). This sense of self-determination and responsibility is frequently cited as a core advantage of the model (Micai et al., Reference Micai, Gila, Caruso, Fulceri, Fontecedro, Castelpietra and Scattoni2022). Schepers (Reference Schepers2024) argued that personal budgets outperform traditional supply-led approaches, particularly by expanding individuals’ freedom of choice. Additionally, IB programmes have been associated with reductions in unmet needs, especially among individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and with gains in independent living, employment participation, and psychosocial well-being (Micai et al., Reference Micai, Gila, Caruso, Fulceri, Fontecedro, Castelpietra and Scattoni2022; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Blaise, Weber and Suhrcke2022).

However, the largely positive portrayal in literature can obscure critical contextual and structural challenges. Evidence from the UK suggests that the capacity to benefit from IB varies significantly across populations: individuals with physical disabilities appear to leverage these programmes more effectively than those with intellectual disabilities (Williams and Dickinson, Reference Williams and Dickinson2016) or those living with mental health conditions and neurological impairments (Riddell et al., Reference Riddell, Pearson, Jolly, Barnes, Priestley and Mercer2005). Carey et al. (Reference Carey, Malbon, Reeders, Kavanagh and Llewellyn2017) cautioned that such disparities may, in fact, deepen existing inequities between disability groups. Moreover, while some studies highlight positive outcomes related to choice, control, service utilisation, and even cost-effectiveness (Webber et al., Reference Webber, Treacy, Carr, Clark and Parker2014; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Blaise, Weber and Suhrcke2022), others have reported mixed or inconclusive results, with variations depending on age, mental health status, and support infrastructure (Glendinning et al., Reference Glendinning, Challis, Fernández, Jacobs, Jones, Knapp and Wilberforce2008).

These inconsistencies point to broader methodological limitations in the current evidence base, raising questions about the generalisability and reliability of findings – particularly in the mental health sector. Furthermore, successful implementation often hinges on users’ ability to navigate complex administrative systems and access adequate support, which may not be equally available across settings. Taken together, these findings suggest that while IB programmes hold transformative potential, a more nuanced and equity-focused understanding of their practical implications is needed.

IB programmes have also been studied from an economic point of view, i.e., whether they change consumption patterns of services and break government budgets, and whether flexible personal budgets affect the marketised disability-services system (Needham, Reference Needham2011). In addition, research studies from Australia and the UK (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Burn, Hall, Mangan and Needham2023) have indicated that the policy shift to MFP or PB has caused disruptions within the economy of care systems, leading to significant concerns about risks to service quality. One failure noted in the literature concerns the coordination breakdowns in multi-agency complex support needs (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Burn, Hall, Mangan and Needham2023); another involves local ad hoc practices that led to spatial inequality (Hummell et al., Reference Hummell, Borg, Foster, Fisher and Needham2023).

However, access to individual budgets is designed to provide user choice and control and to stimulate competition between providers to drive down costs and improve services. Implementing this approach and transitioning to a mixed public-private market to extend user choice causes inevitable disruptions (Vamstad, Reference Vamstad2015). This course of action also creates complexity for decision-makers and stakeholders and risks to service quality. Given distinct patterns of existing welfare services and market maturity, these risks and opportunities will be experienced differently in different welfare regimes (Toth, Reference Toth2010).

Supply-led theory

In many countries, the policy for creating services in the disability markets continues to be based on the supply-side theory through which resources are directed towards specific markets and products; that is, ‘pushed’ by supply factors and not ‘pulled’ by demand factors. Providers develop diverse, innovative, high-quality services tailored to the profiles of people wanting support (Needham et al., Reference Needham, Hall, Allen, Burn, Mangan and Henwood2018). Supply-led service innovation describes a process in which suppliers leverage knowledge, incentives, and funding to develop new products, processes, and services based on their capabilities and goals without direct confirmation and verification of market needs (Donahue and Nye, Reference Donahue and Nye2004). The demand side for services in the disability markets is manifested in the preferences and consumer behaviour of the end-users. Economists have pointed out that health patients rely on providers to help them articulate their demand for care (Ellis and McGuire, Reference Ellis and McGuire1993). This study examines whether private providers can adapt their services to people with disabilities and whether they have the capabilities to deal with the different needs of people with disabilities during the provision of services.

The Israeli scene as a case study

Shortly after, Espen-Andersen (1990) suggested three models of welfare regimes; some researchers (Ferrera, Reference Ferrera1996; Rhodes, Reference Rhodes and Rhodes1997) identified a fourth regime, the Latin Rim or a Mediterranean welfare regime. More specifically, the three distinctive characteristics of the Mediterranean welfare regime as identified by Ferrera (Reference Ferrera1996) in the mid-1990s, were (a) the dualism, fragmentation, and ineffectiveness of the social protection system which often led to marked gaps between segments of society and high levels of poverty within specific geographical or social sectors; (b) the existence of universal (or near-universal) health provision by the State alongside a flourishing private health market; and (c) the particularistic–clientelist form that the welfare state took in these nations. In addition, several observers have underscored the central role of the family, rather than the State, the market or the workplace, as a provider of welfare in these countries (Moreno, Reference Moreno2002; Naldini, Reference Naldini2004).

The social welfare systems in Israel were modelled closely on the British system during periods of British colonial rule and in its wake (Gal, Reference Gal2010). However, the Israeli welfare regime is defined as a Mediterranean welfare regime by three broad cultural attributes that have a marked impact on welfare state formulation and distinguish it from other welfare regimes: religion, the family, and the persistence of clientelist–particularistic forms of welfare (Gal, Reference Gal2010).

Moreover, the Israeli welfare state is influenced by neoliberalism. Harvey (Reference Harvey2005) defines neoliberalism as a theory of political and economic practices that proposes liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills to best advance human well-being within an institutional framework characterised by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade. The State’s role is to create and preserve an institutional framework appropriate to such practices. Since the rise of neoliberal-ideological thought in the 1980s, there has been a transition in the disability service system to encompass elements such as choice, competition, and integration between public and private social services. These elements play an increasingly significant role in shaping social policy and the delivery of services in Israel (Levi-Faur, Reference Levi-Faur2014; Benish and Mattei, Reference Benish and Mattei2020).

Currently, about 80 per cent of social services in Israel are outsourced by the Ministry of Welfare and Social Affairs. Most service providers to this ministry are veterans in the field, and they garner about 96 per cent of the total payments for outsourced services. Competition among service providers in the field of personal social services is limited. Israel has been undergoing a steady process of privatising services that were once governmental, including welfare services (Madhala-Brik and Gal, Reference Madhala-Brik and Gal2016). The government tenders carry out the outsourcing process, inviting agencies to compete for a contract to perform an action or operate a service for a predetermined period. The choice of providers relies on defined criteria, and the State is responsible for assuring the proper operation of the privatised service through a regulatory system (Lahat and Tal, Reference Lahat and Tal2011). The assumptions underlying the outsourcing of social services are that this system allows greater flexibility and effectiveness of operation, and that competition between different specialised service providers will improve the service to citizens. The competition between the providers takes place at the tender stage, and in most cases, there is no competition between the providers over the service recipients. Recipients are generally referred to service providers by the ministry or the local authority and often have little choice over which provider to use (Madhala-Brik and Gal, Reference Madhala-Brik and Gal2016).

The State of Israel ratified the CRPD in 2012. However, there are still disparities between the vision of the CRPD and the situation of Israeli citizens with disabilities in all areas of life. The Welfare Bill for People with Disabilities - 2022 and its implementation process determines the right of every person eligible, according to CRPD principles, to receive social and care services tailored to their needs within the framework of the support level regulated by the law and the financial limitations. The law also states that the Ministry of Welfare and Social Affairs can operate an ‘Individualised Budgeting’ (IB) programme with the agreement of the State’s Department of the Treasury.

The government began a pilot of the IB programme in 2020, one that was developed by JDC-IL (a key NGO). The programme is intended for people with disabilities recognised by the Disability Administration at the Ministry of Welfare and Social Affairs and for those with disabilities at the Community Mental Health Rehabilitation System of the Ministry of Health.

In Israel, the Ministry of Social Welfare and Social Affairs takes responsibility for providing care and support for individuals with disabilities, including those with sensory, mobility, developmental, and other types of disabilities. Individuals with mental disabilities fall under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Health; this includes those with mental health conditions that may require specialised healthcare services, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation.

The literature usually distinguishes among four case management models: the generalist model, assertive community treatment/intensive case management, the clinical/rehabilitation model, and strengths-based case management (Vanderplasschen et al., Reference Vanderplasschen, Wolf, Rapp and Broekaert2007). The IB case management in Israel adopted the generalist model.

The country is divided into local and regional authorities and councils whose social workers and rehabilitation social workers refer eligible persons to an IB coordinator operated by two external operating bodies (Rimon-Greenshpun et al., Reference Rimon-Greenshpun, Bachar and Barlev2020). The IB-coordinator co-designs with the eligible person to determine the types of support that will address their unique needs, what is important to them, and what will help them achieve their personal goals (Leplege et al., Reference Leplege, Gzil, Cammelli, Lefeve, Pachoud and Ville2007).

Depending on disability diagnosis and level of functioning, they co-design a care plan using supported decision-making (SDM) assistance from the IB-coordinator (Blanck, Reference Blanck2023). The services are targeted to three areas of life: education, leisure and life skills, and employment. To achieve goals in each life field, the participant can consume public services, private services regulated by the State, and private services that the State does not regulate. About 150 eligible persons with disabilities have already participated in the pilot programme.

The application of the IB programme to the Mediterranean welfare regime has not been previously explored. This innovative study can elucidate the inherent tensions and barriers unique to this type of welfare regime. This article examines how a personalisation mechanism changes the service delivery system for people with disabilities in the community, focusing on a supply-side perspective in a Mediterranean welfare regime context. The study analyses the fit of the mechanism vis-a-vis the service system employing Gilbert and Terrell’s theoretical analysis framework. Understanding this integration’s theoretical and empirical implications is essential to support the development of more effective policy design.

The theoretical model

The intricate nature of welfare service systems introduces challenges the literature has previously addressed including fragmentation, discontinuity, accountability, and accessibility failures (Gilbert and Terrell, Reference Gilbert and Terrell2002).

Fragmentation is the allocation of authority and responsibility for the provision of services to more than a single government ministry and, hence, also to several suppliers and sub-suppliers. Sometimes, services from tangential fields will be under the authority of several government ministries, and the service recipient must exercise their right with each of the ministries separately. Failures resulting from fragmentation may result from organisational failures or disconnections between organisations, such as different locations, different service delivery hours, duplication of services, and the like (Grone and Garcia-Barbero, 2001; Vondeling, Reference Vondeling2004).

Discontinuity refers to a disruption in the seamless provision of services, indicating deficiencies in the flow or a transition of individuals interrupting the service supply network. This disruption manifests as gaps between a person’s needs and the benefits they are entitled to, often characterised by a lack of effective communication channels in the various services meant to assist the service recipient. The existing literature has established that discontinuity has detrimental effects on service quality and treatment outcomes, potentially resulting in the inefficient use of service resources in mental health cases (Berghofer et al., Reference Berghofer, Schmidl, Rudas, Steiner and Schmitz2002), home support care (Sharman et al., Reference Sharman, McLaren, Cohen and Ostry2008), and municipal stroke rehabilitation (Aadal et al., Reference Aadal, Pallesen, Arntzen and Moe2018).

Accountability failures are related to the ineffectiveness of resource allocation and its use. Accountability also reflects the extent to which service designers and providers respond to the pleas of the service recipients (Innes, Reference Innes2015).

Failure to access one’s right to a social welfare service is usually the result of not knowing that the service exists or that one is eligible to receive it (White et al., 2015), geographic barriers of a long journey or lack of means of transportation (Provenzano, Reference Provenzano2024), as well as time barriers since people from low socioeconomic strata who are required to work many hours sometimes find it challenging to find time to consume services (Griffiths, Reference Griffiths2003).

In response to those four system failures, Gilbert and Terrell (Reference Gilbert and Terrell2002) established three principles for a more competent welfare service system:

Reducing fragmentation and interruptions in service sequences by increasing coordination, opening different communication channels, creating new options for laying claim to the service (even without a diagnosis, for example), closing duplicate services, etc.

Reducing accessibility barriers by creating new ways to enter the service.

Reducing carelessness in control and supervision processes by creating mechanisms for feedback from the service recipient.

Suitable criteria for a welfare services system

Gilbert and Terrell’s framework for welfare policy analysis includes six suitable criteria for a welfare services system:

Integrated service system – Coordinating all parts of the system, creating computerised management and supervision systems, and strategic work with data such as segmenting recipients’ profiles and their needs (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Rosen and Rumbold2011).

Service integration – Coordinating all services holistically to meet the recipients’ needs. Several strategies may satisfy this criterion, such as utilising a PB coordinator or case manager or establishing multi-disciplinary committees to discuss a personal care programme (Delnoij et al., Reference Delnoij, Klazinga and Glasgow2002).

Systematic function distribution – For a continuous and diverse supply of services. This category also includes cultural adaptation of the service to a variety of communities (Atun et al., Reference Atun, de Jongh, Secci, Ohiri and Adeyi2010).

Professionalism – An individual’s adherence to a set of standards, code of conduct, or collection of qualities that characterise accepted practice within a particular area of activity.

Accessibility – The ability for recipients to enter, approach, communicate with, or use an agency’s services, including but not limited to access to bilingual staff, minority-specific programming, staffing patterns that reflect community demographics, and adequate operation hours.

Accountability – Accepting responsibility for honest and ethical conduct toward others. In the corporate world, a company’s accountability extends to its shareholders, employees, and the community in which it operates. In a broader sense, accountability implies a willingness to be judged on performance.

Study objective

The current study aimed to investigate the alterations introduced to the service delivery system for people with disabilities within the community from a supply-side perspective, following the implementation of an IB programme using Gilbert and Terrell’s theoretical analysis framework. The main research questions accompanying this study were:

What is the nature of the welfare service system that is emerging in the context of the Mediterranean social-democratic welfare regime?

Is the service system efficient and effective, or are there failures in the system?

Methods

Study design

To address the research questions, a qualitative approach was developed that focuses on suppliers’ voices and experiences, aiming to reveal their priorities and aspirations regarding service provision via the IB programme. It does not presume to present objective or absolute scientific truth; instead, it examines the question of meaning within a concrete context (Rom and Benjamin, Reference Rom and Benjamin2011).

We employed a multi-criteria policy analysis method (Lonsdale and Enyedi, Reference Lonsdale and Enyedi2019), utilising Gilbert and Terrell’s framework for welfare policy analysis (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Chon and Kim2023). To examine the nature of the service delivery system, we examined whether the chosen six criteria: integrated service system, service integration, systematic function distribution, professionalism, accessibility, and accountability, are present in the emerging service delivery system.

Using qualitative and systematic techniques, we can comprehensively compare the emerging welfare system and the traditional system, mainly focusing on the absence of personalisation policies in the latter system. Two supplier groups were created for comparison: a first group of suppliers working with the IB programme and a second group referred to throughout the report as ‘universal suppliers’ who do not currently work with the programme. Since the programme implemented specific municipal authorities, the universal suppliers were taken from other geographical areas. The first group contained eight suppliers, and the second group contained six universal suppliers.

Participant’s characteristics

We interviewed eight suppliers who worked with the programme and six universal suppliers. Of the suppliers (group A), all worked with both NGOs that operate the programme; three were home-economic advisors, three were fitness trainers or yoga teachers, one was a gel-polish instructor, and one was a cooking teacher.

Two of the suppliers had formal education in the field of care or welfare beyond their profession as a supplier in the programme.

Five of the suppliers described previous experience working with people with disabilities. Three described the IB programme participants as their first customers who introduced themselves as people with disabilities.

The universal suppliers (group B) included a director of programmes for people with disabilities in a large NGO, a business consultant, a college director for sports trainers, a therapeutic yoga teacher, a college director for professional employment, and a music school director.

Two of the universal suppliers group reported having formal education in the field of care or welfare.

Five in this group described previous experience working with people with disabilities. They also reported that they already supply their services to people with disabilities.

Ethics and procedures

The institutional review board of Tel Hai College and the Research Division of the Israel Ministry of Welfare and Social Affairs approved the study.

Participants were provided with essential details about the study. The voluntary nature of participation was strongly emphasised, as was their right to decline or withdraw at any point without facing any consequences. Assurances were given that every effort would be made to safeguard their anonymity and confidentiality. All participants willingly agreed to take part in the study and signed informed consent forms.

Interview guide for participants

An interview guide with in-depth questions was composed for each group. For example, we asked the group of suppliers who worked with the programme (a) How did you become a supplier in the IB programme? (b) What challenges did you experience when starting work with the programme participants? What helped you and the participants face these challenges? (c) Are you in contact with the participant’s case manager? Or with his/her family members?

The group of universal suppliers received an explanation about the concept of the IB care programme and were asked questions regarding this mechanism and the potential to cooperate with a programme of this type. For example, (a) Would you consider joining as a supplier in such a programme? (b) If you were required to meet certain conditions (for example, a regulated price) and register in a supplier database, would you do so? (c) What was required to prepare for the reception of people with disabilities into the services? And so on.

Procedure

Between January and March 2023, fourteen interviews were conducted, all face-to-face using Zoom software, in the presence of the two researchers. Both researchers also conducted the data analysis. The first author of this article is from the field of public policy and administration, and the second author is a social worker who has worked with adults with disabilities and their families. We maintain that combining our perspectives increases the range and depth of the information we gathered on suppliers of community services for people with disabilities.

Data analysis

All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analysed thematically (Thornberg and Charmaz, Reference Thornberg and Charmaz2014). The interviewees were asked open questions that were sometimes expanded according to the conversation’s development.

Data analysis began with the first author reading all the qualitative data to immerse herself in the experience of the participants and to get a sense of the entire phenomenon. Next, the first author read each response to the survey once again, taking notes on her first impressions, thoughts, and initial analyses, sorting units of meaning into the six criteria when possible, and then developing new criteria for each unit of meaning identified. A peer debriefer, the second author, audited the process by reviewing the research methodology, the coding process, and the proposed additions to the criteria. As mentioned, we used the six criteria detailed in Gilbert and Terrell’s (2002) policy analysis framework for good welfare service delivery to analyse the system’s fit. Since we use thematic techniques, all six criteria are referred to in the results section, but new criteria are also raised from the analysis.

After extracting the meanings from the text and analysing each criterion in the model, the level of compatibility between a criterion and its activation in the system when a personalisation mechanism is in place was discussed. Each criterion could be a full-, partial-, or non-fit to the system.

Results

The nature of the service system

The nature of the emerging welfare service system is based mainly on a mixed market of public services, private services that are regulated, and private services that are not regulated. The main disruption in this mix of services stems from the non-regulated private services. Adding the personalisation process to the framework of the services offered by the State would create more regulation. Currently, the number of unregulated suppliers participating in the IB programme is small, and all of them are small businesses. Therefore, these changes are contained, for now.

The IB programme is implemented by JDC-Israel, which is a major NGO organisation that can support other organisations in service delivery and ease the bureaucracy process. The JDC has chosen two operational bodies that allocate IB Care Planning services in different regions of the country, organising budget infrastructure and flow to the suppliers. In one case, JDC also made an agreement with an additional operator that specialises in home economy to supply all services in this domain. Therefore, we can identify public, private, and non-profit actors of varying size and activity areas in the system.

Most universal suppliers already provide services to people with disabilities who approach them spontaneously. That is, people with disabilities manage to independently integrate to a certain extent into various service organisations and suppliers in the community who promote inclusion and have already made the necessary adjustments. What emerges even more strongly is that universal suppliers, in most cases, discover that they provide a service to a person with a disability only after they enter the activity. They adapt the service to the consumer’s needs dynamically and without training. In some cases, when we asked service suppliers if they provide services to people with disabilities, they replied that they did not, or that they did not know of any such users. Only later in the interview did they remember providing services to people with disabilities, thus revealing that sometimes the issue of disability was not a barrier for them.

We identified two significant gaps in this market. The first one revolves around a shortage of qualified universal suppliers catering to individuals with disabilities in the community, indicating a limited awareness of people with disabilities and their functioning, and limited resources for this purpose. The second gap pertains to services designed for the non-disabled population, such as driving courses, professional training, and music classes, which are not tailored to accommodate individuals with disabilities. IB coordinators encounter challenges in finding suitable universal suppliers for these specific areas.

Entrance channels to the service system

Various avenues exist for suppliers to become part of the programme. Referrals may come directly from participants or through an IB coordinator. Two IB suppliers shared instances where participants initially approached them independently, unrelated to the IB programme, seeking individual classes through the IB programme after facing challenges with group activities. Additionally, two suppliers had previous connections with the IB coordinator from earlier pilot initiatives. Another provider joined the programme based on a recommendation to the IB coordinator by a third party. All IB suppliers highlighted a brief joining process involving the presentation of professional certificates and the submission of supplier documents via email.

Considerations and form of service delivery

Most IB suppliers mentioned that they collaborate individually with IB programme participants, tailoring their services to accommodate each individual’s abilities. However, there is no description of services provided in a group setting that are specifically adapted to participants with disabilities.

Suppliers noted that the key to delivering the service lies in adjusting the pace, altering the sequence of class components, and closely monitoring participants’ reactions throughout the process. They also consider the participants’ ability to accept changes and actively invest in emotional support and nurturing patience.

A fitness trainer expressed the necessity for pre-assessing a participant’s comfort level with touch and evaluating whether they pose a risk to themselves or others. This understanding helps determine whether to include the participant in group activities. The trainer also emphasised the significance of addressing constancy and dropout issues, particularly among individuals with mental disabilities.

“You have to start every workout with a conversation about the condition of the trainee. People with mental disabilities will not come to training alone and if they can cancel, they will do so all the time. I do not allow cancellation and ask them to come even when it is difficult.”

It is pertinent to acknowledge that some IB suppliers anticipate a likelihood that participants will not independently engage in leisure pursuits, necessitating external motivation. Individuals on the autistic spectrum encounter considerable difficulties in social contexts, compounded by issues of perceived vulnerability. In specific instances, parental guardians may opt to accompany their children with disabilities to a class or refrain from sending them altogether due to concerns related to insufficient protective measures in place.

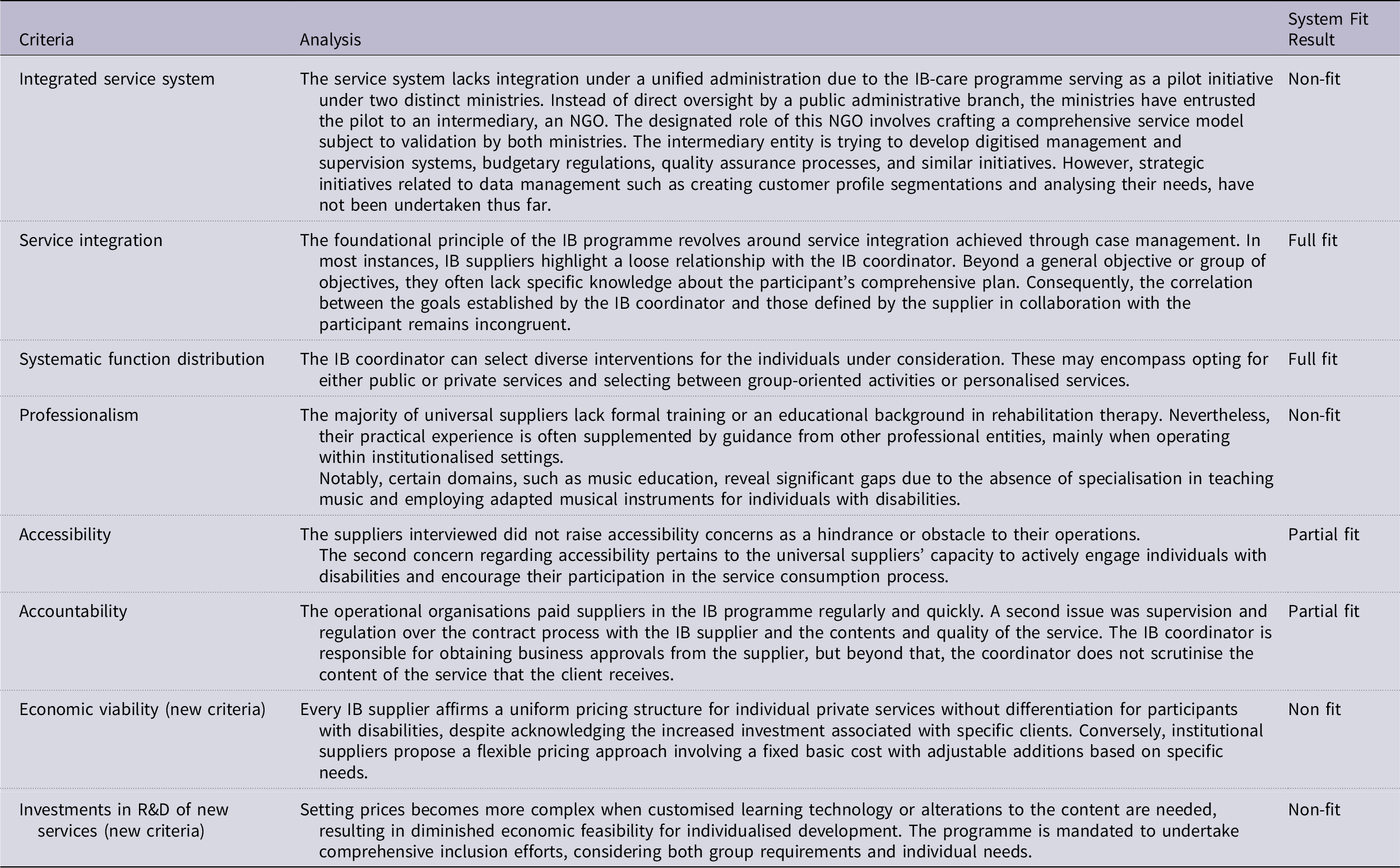

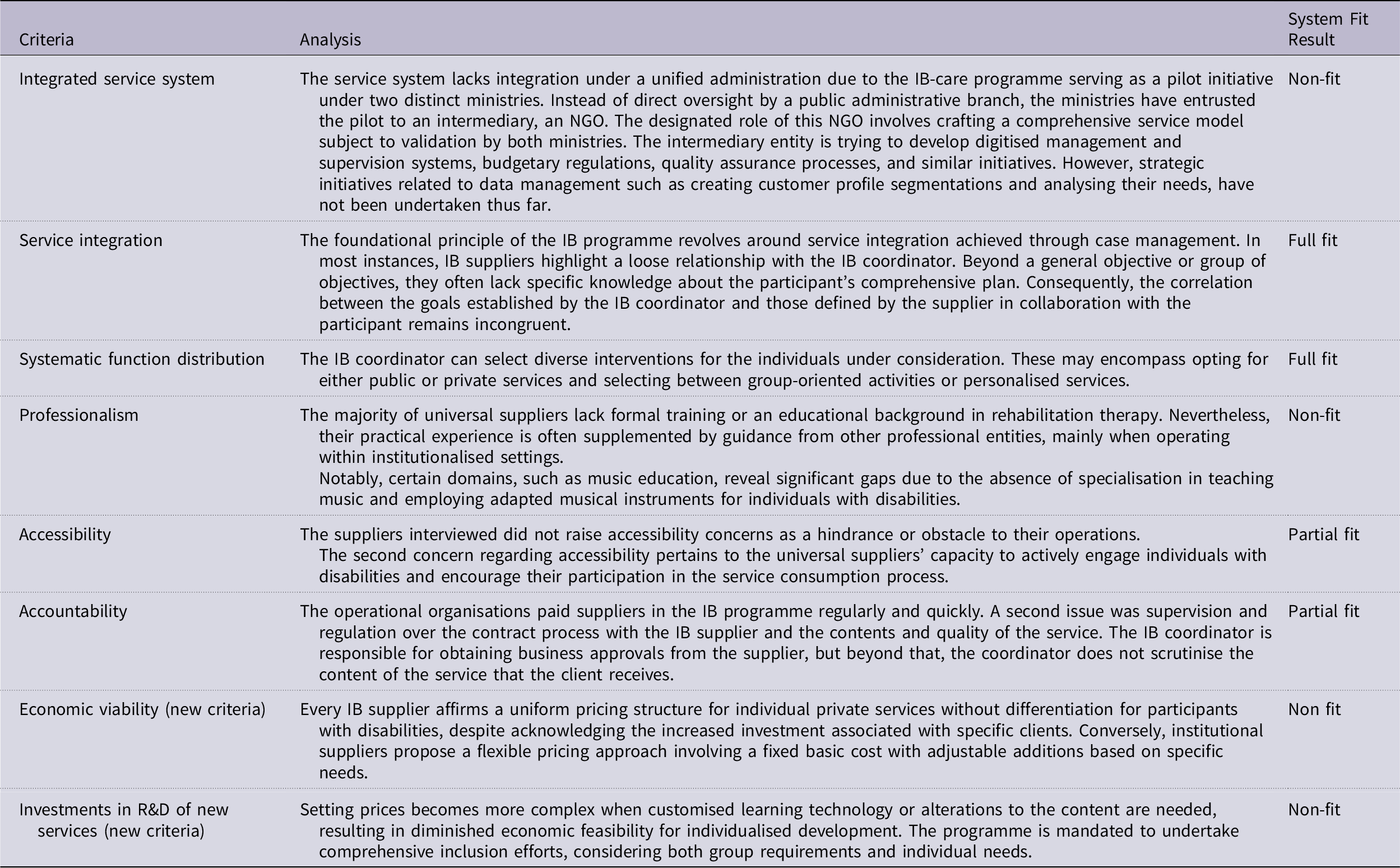

The analysis of the service systemʼs fit is presented in Table 1:

Table 1. Analysis of the service system’s fit

Following the examination of the six primary categories in the model, two additional categories emerged: economic viability and investment in research and development (R&D) for new services. The former refers to the assessment of whether the anticipated profit or return from an investment is substantial enough to rationalise and warrant the initial financial commitment. It involves a thorough evaluation of the expected financial gains to gauge whether they are not only favourable but also robust and justifiable in relation to the resources and capital invested in the venture. The latter, investment in R&D for new services, involves engaging in creative and systematic endeavours to expand the existing knowledge base and discover innovative applications for that knowledge. A proactive and strategic approach is necessary for generating new insights, technologies, or methodologies with the goal of enhancing and diversifying the range of services offered. Essentially, this is a deliberate investment in the exploration and creation of novel solutions, methodologies, or products to stay ahead in a dynamic market and meet evolving needs.

Discussion and conclusion

The IB programme is currently in its preliminary stage and has yet to significantly impact the care economy or the service framework for individuals with disabilities in Israel. Commencing with small private suppliers, the IB programme currently holds a modest market share, and the transformation is occurring gradually rather than dramatically. The nature of the welfare service system that is emerging still follows the predominant mode of service delivery in which the institutionalised NGOs or private entities are accustomed to negotiating with Ministry representatives regarding service input and quality. The mediator, an NGO, is capable of being responsive in its flexibility and availability to small suppliers. However, the majority of institutionalised NGOs, not yet engaged with the IB programme, primarily provide group activities and cannot offer individualised, customised services. Still, the demand for integration is expected to rise when institutional actors join the programme as suppliers, owing to their distinct work methodologies and pricing approaches.

We evaluated the fit of the emerging service delivery system according to eight criteria. Due to the differences among the criteria, we created a scale of three levels: full fit, partial fit, and no fit. The criteria that did not fit a good service delivery system represented system failures. The criteria of service integration and systematic function distribution exhibited a full fit with the effective implementation of a delivery system within the IB programme. The accessibility criterion and accountability criterion demonstrated a partial fit, indicating a need for increased investment in regulation and quality control measures.

Four criteria deviated from constituting a fit with an effective service delivery system, particularly concerning potential system failures. Firstly, the criterion of an integrated service system was compromised when the State opted for an intermediary, an NGO, instead of establishing a public managerial body for integration. This disparity has the potential to influence the strategic decision-making process and regulatory aspects, and to contribute to fragmentation within the system. The second criterion pertains to professionalism, which is deemed unfit for a robust delivery system, as it poses a risk to service quality. Two criteria are new to the model but were firmly rooted in the findings. The economic feasibility of personalised and individualised services for larger private suppliers has not been thoroughly examined. This factor significantly influences pricing, a consideration to which the smaller suppliers did not react. The second criterion is investment in new services’ R&D. The IB programme did not consider this aspect, but the State should recognise this market failure to invest in technological service innovations.

This case study demonstrates the introduction of a personalisation mechanism into a Mediterranean welfare regime characterised by fragmentation and privatisation. Those two processes raised concerns about the quality of services for people with disabilities, and the State deepened its regulatory tools through tenders to establish threshold conditions for quality. It is impossible to enforce the State’s role as a regulator when services are purchased in the private market. Still, the fragmentation failure stayed in place.

Several observers have underscored the central role of familialism (Moreno, Reference Moreno2002; Naldini, Reference Naldini2004) and solidarity as core values in the Mediterranean welfare regime. Introducing personalisation into this regime disrupts the balance among the individual, family, State, and civil society. In this pilot, the government used civil society agencies to introduce personalisation and act as an intermediary between the individual and the market. Even though civil society does not have any regulatory authority on the market, in this case, civil society’s role and weight grow in this relationship.

Moreover, tensions remain between an individual’s desires and those of his family and community. These tensions are an expression of the introduction of individualism into traditional societies (Negri and Saraceno, Reference Negri, Saraceno and Andreotti2018). The IB coordinators ask the participants to find the services they want to purchase in the community. This request grants the individual’s family a significant part in determining the basket of services that will be provided, as they apply the social and religious norms acceptable to them. Therefore, personalisation in the Mediterranean welfare regime allows incubation for individual autonomy but does not break the social and cultural boundaries of the communities.

We conclude that the State should consider addressing the partially fit and non-fit criteria for a good service delivery system when adopting the IB programme.

While there is no State integrator body, a system mediator is probably necessary to deal with the failures raised here.

Research limitations and future research

This study comprised a limited number of suppliers due to the current small scale of the IB programme. Consequently, the findings should be regarded as preliminary, and further research is warranted. Two key aspects are suggested for future investigation: firstly, exploring the involvement of major private suppliers in the IB programme, given their distinct methodologies, and secondly, examining the market dynamics when the IB programme attains a substantial market share. It is also recommended that future investigation will hold participants and social worker perspectives on the supply side of the welfare service system.

Author Contributions: CRediT Taxonomy

Tali-Noy Hindi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Ayelet Gur: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Financial support

The article benefits from the support provided by the JDC-Unlimited non-profit organisation.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.