In December 2017, Carl-Ludwig Thiele, at the time a member of the German central bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) executive board, wrote an article for the online publication of the World Gold Council (WGC) Gold Investor, entitled “Transparency – At Least as Valuable as Gold.”Footnote 1 The article focuses on policy changes and public relations moves undertaken by the Bundesbank in response to fears among the public that German gold was at risk by being stored outside the country or even that it was “not really there.” One such response to these types of public concern was the transfer of 674 tonnes of gold from vaults in London and New York to Frankfurt. He outlines four “steps to increasing transparency”: the disclosure of the amount of gold in the bank’s possession and of the transfer of gold from Paris and New York to Frankfurt, the commissioning of a film to document the transfer, and the publication of “all German gold bars, totalling around 270,000 in number” (Thiele Reference Thiele2017). The year after this article was published, to mark the completion of the gold transfer program, the Bundesbank also produced a striking coffee-table book, Germany’s Gold.

In framing these changes in this way, the article links the gold transfer program to broader trends toward “transparency” within gold markets. These transparency projects have expanded tremendously in the last three decades as a particular iteration of “audit culture” (Power Reference Power1994; Strathern Reference Strathern2000). In this chapter, I consider how transparency and gold are established and maintained as “global values” and how actors differently positioned within gold markets seek to align them, with greater and lesser degrees of success. I trace how this happens in three clusters of transparency projects: certification schemes and voluntary frameworks for mining companies; efforts to use blockchain technologies to increase transparency in the supply chain; and efforts to verify (and perform the verification of) gold’s presence in European central banks, especially the Deutsche Bundesbank. Exploring these specific sites where transparency and gold convene, both supporting and tugging against each other, illuminates a critical moment in gold’s history and also allows us to consider transparency from an angle that, unlike many other discussions, does not only operate “within the limits of the very ideology of the phenomenon under examination” (Ballestero Reference Ballestero2012a: 161). In particular, I view gold and transparency as engaged in competitive processes of value-making (and unmaking).

As part of this volume’s attention to “the comparative establishment of the position of transparency in a broader system [or systems] of value” (see the Introduction), this chapter assesses transparency as a global value in relation to the seemingly more self-evident (perhaps, or perhaps not) global value of gold. This approach must first take account of the dynamic and processual nature of transparency as a value – and, indeed, of value (or, more precisely, value-making) itself. Elsewhere (Ferry Reference Ferry2013) I have argued for seeing value-making as a two-part process, consisting both of “making meaningful difference” and also, critically, of “making difference meaningful.” By this last phrase, I mean the often messy process through which it is established that it is worth distinguishing between two or more given values. One can say that one bar of gold is finer (has a higher percentage of gold) than another, or that one policy for informing the public about central bank holdings is more transparent than another, and that can be taken as an important and relevant comparison. And this comparison can be the subject of contention or consensus.

However, for there to be any point to that comparison, at least some people must recognize that it is worth making distinctions between gold and transparency. The historical, political nature of this aspect of value often escapes notice, and yet it is arguably the site of most politics around value. We can frame the emergence of transparency in the past few decades in these terms, as the relative stabilization of value-making acts such that transparency becomes something for which differences are meaningful – that is, something valuable.

Indeed, this is what efforts at ethical marketing aim to do: to establish some chosen characteristic as worth making distinctions between – organic or shade-grown coffee, Malagasy vanilla, conflict-free diamonds (Bell Reference Bell2017; Osterhoudt Reference Osterhoudt2017; Roseberry Reference Roseberry1996).Footnote 2 Getting people to buy these ethical products is one kind of value-making act (and each successful or uncontested value-making act helps to make the next one more successful), but so are actions such as the establishment of metrics and certification systems, press conferences, or, as in this case, alignment with another value that seems to be secure or uncontested. Hence the headline “transparency – at least as valuable as gold” or the familiar phrase that something is “worth its weight in gold” (even when that something is not a tangible, weighable object, as in the case of transparency). In these phrases, gold is taken as the stable and self-evident form of value. and whatever is being aligned with it is claimed as also (like gold) worth making distinctions between.

But wait. It appears from the title of the Gold Investor article (which is, as you may be able to tell, aimed primarily at investors in gold) that transparency is the thing that needs to be argued for, whose value must be shored up by reference to the self-evident value of gold. But in a broader context, gold as a global value is not as stable as you might think. Thiele is arguing for the value of transparency to the immediate audience of gold investors (who are likely to be among gold’s staunchest allies, one may presume), but on a broader scale the article and the actions it describes can be read as an attempt to shore up gold’s shaky status as a global value by linking it to transparency.

A Brief and Imperfect History of Gold as Global Value

In order to understand what is happening with gold now, we need some sense of how it has been established as valuable, especially in European and Euro-descended contexts.Footnote 3 For centuries, gold has been viewed as a substance with distinctive and impressive material semiotic force (Green Reference Green2007; Maurer Reference Maurer2005; Vilar Reference Vilar and White2011) that is linked to value and sovereignty and thus to market and state (Hart Reference Hart1986). In particular, gold’s close association with money is both a consequence and a driver of its tremendous cultural power over the course of many centuries. During these centuries, gold functioned primarily as a method for large payments and as a reserve currency (with silver and copper much more commonly in circulation), as well as a means of adornment and of the display of power and transcendence (Bernstein Reference Bernstein2012).

While Britain moved to a single gold standard in the early nineteenth century, most other countries operated on either a silver or a bimetallic standard. Only after 1870, because of Britain’s dominance as an industrial and financial power, did most European and American countries, and others outside these zones, move to a gold standard (Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen2019: chapter 2). The gold standard as an international system lasted until 1931 (barring an interruption from World War I to the mid 1920s) (Green Reference Green2007), though not without continual adjustments and coordinated action between countries to maintain its efficacy in times of crisis. The system depended on an “overriding commitment on the part of central banks to external convertibility” (Eichengreen Reference Eichengreen2019: 32) and was ultimately challenged by the rise of fractional reserve banking, since this form of banking depends on a central bank as backstop or “lender of last resort,” leading to a structural tension between external convertibility and domestic financial stability.

Obviously critical to gold’s value, and equally obviously beyond the capacity of this chapter to capture adequately, are gold’s uses as a sign of power, luxury, and transcendence. From the gold halos of saints in Byzantine art, to the crowns on the crowned heads of Europe, to John Donne’s lines in “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning,”

to the gold plates of aristocracies, to the gold toilet on display at the Guggenheim museum (titled America), to the Yellow Brick Road leading to the Emerald City where trickery and illusion reign (Graeber Reference Graeber2011: 53), to the gold-induced madness in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre – we could go on and on – gold signifies a bewildering range of things: power, transcendence, truth, falsity, idolatry, shit, and so on. Many of these meanings come from (or are perceived as coming from) its material qualities of malleability, mass, luster, nobility (non-reactivity), and color. And these ways in which gold acts as a global value endure, even as its value as a reserve currency has been displaced.

Gold’s status as reserve currency came to an end over the course of the twentieth century, first in the 1930s and again in 1971 when Richard Nixon ended the convertibility of gold with the dollar at a rate of $35 per ounce. As we will see below, although much of the world’s gold is still held in central banks (especially in the US, Germany, UK, France, and China), it no longer plays any significant functional role in national economies,Footnote 4 although it may serve to project confidence and security (as Thiele suggests in his article).

In the years following this decoupling of gold and the dollar (and therefore much of the world’s money supply), gold’s price rose precipitously, culminating in the early 1980s at a price of $850 per ounce (London Fix Price).Footnote 5 The price then declined through the 1980s and was driven yet further down when the Bank of England sold off over half its reserves (395 tonnes) (Ash Reference Ash2019). This began to reverse as the prices for commodities in general, and gold in particular, rose in the early 2000s. Gold reached a nominal high of just over $1,900 per ounce in 2011 (when adjusted for inflation, the high at the beginning of 1980 is still the historical high in real terms).Footnote 6 For several years after this, gold’s price wandered in the range of $1,100–$1,300 per ounce, in many cases close to the cost of production. In the summer of 2019, gold rose again above $1,500 and above $1,800 during the Covid pandemic, invasion of Ukraine, and rising inflation. This is in part because of gold’s generally accepted value as a barometer for fears of instability and crisis,Footnote 7 and the fact that its price tends to move independently of other important asset classes such as the US dollar and the stock market (Baur and Lucey Reference Baur and Lucey2010). As of this writing, in September 2024, gold reached a historical (nominal) high at $2,580 per ounce, with the 400-ounce gold bar topping $1 million in August 2024 (Maruf Reference Maruf2024).

Notwithstanding these recent high prices, gold-mining companies since the 2000s have faced a series of ups and downs. The dramatic Bre-X hoax concerning an alleged gold mine in Indonesia brought lots of unwanted publicity to the ill-regulated field of “junior mining” and what one interlocutor described as a “nuclear winter” in mining investment (Tsing Reference Tsing2000). A few years later, high metals prices spurred exploration and production in many brown- and greenfield sites, building on existing or newly exploited facilities, as well as artisanal and small-scale mining in Latin America, Africa, Australia, and Papua New Guinea; these in turn have sparked conflicts both explosive and grinding (Kirsch Reference Kirsch2014; Li Reference Li2015; Luning Reference Luning2012; Rosen Reference Rosen2020). These years have increased public awareness of the links between gold mining and armed conflict, and the severe environmental damage caused by both “informal” small-scale mining and large-scale mining, especially open-pit mining (Verbrugge and Geenen Reference Verbrugge and Geenen2020). Calls for further controls, transparency, and ethical practices in the gold sector have grown more and more insistent.

Gold faces opposition in financial circles as well. Because it is listed as a commodity, many institutional investors (such as pension funds) cannot invest in it. Many financial professionals dislike it as an investment because in its physical form it gives little to no return and in other forms (as mining equities or exchange-traded funds) it can be risky and its price movements complex and difficult to understand. One interlocutor, when asked why many financial advisers don’t like to invest in gold, licked his finger and held it up as if testing the direction of the wind, and said, “It’s too hard to interpret.” Its cultural and affective associations as outdated and fetishized (“idolized” or “worshipped,” as my interlocutors would tend to describe it) and the vocal presence of “gold bugs”Footnote 8 (called by one of my interlocutors “the tinfoil hat crowd,” in reference to the farcical Facebook attempt to pit conservative news commentator and gold bug Glenn Beck against a poodle in a tinfoil hat) make it seem kooky and cranky to some investors, and organizations such as the WCG spend time distinguishing their perspective on gold from these more extreme positions and seeking to burnish gold’s reputation as a sensible, rational investment.

Of course, gold is still recognized widely as a valuable asset and it still commands cultural force the world over. Its price is high and demand for gold in China, India, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East booms; and, as the recent prices attests, it continues to work as a safe-haven asset in times of uncertainty, and to respond to changes in interest rates. Technologies for investing in gold (such as exchange-traded funded and asset tokenization) continue to be invented. Nevertheless, gold’s age as a global currency is over, and its integrity as a stable nexus of value-making practices has been fraying for some time. Moreover, its associations with money laundering and arms trading and the environmental damage caused by mercury use, large-scale open-pit mining, and unregulated small-scale mining have placed the industry on the back foot, causing some actors and institutions to mobilize transparency as a strategy to “clean up” the industry and “burnish” its reputation.

Transparency talk can be found throughout gold extraction, circulation and, investment these days; this chapter centers especially on the invention of technologies to render the supply chain more transparent, the mobilization of blockchain technology (discursive and material) in these technologies, and, drawing on the topic of the Gold Investor article with which I began, efforts by central banks to project simultaneously transparency and security with respect to their gold reserve holdings.

Transparency’s Trajectory

Transparency technologies have been defined by Andrea Ballestero in the introduction to a 2012 Political and Legal Anthropology Review special issue on the topic as “a political and legal device … intended to correct the democratic deficits of existing forms of law, bureaucracy, and even subjectivity” (Reference Ballestero2012a: 160). They aim to infuse institutions with rationality, fairness, and accountability, and are generally contrasted with opacity, secrecy, conspiracy, and corruption.

The story of transparency’s journey to prominence and proliferation as a global value can be told in several different ways: as, for instance, a descendant of glasnost (the term describing movements toward “openness” within Soviet institutions during the Gorbachev period) promoted by NGOs (especially environmental ones) in the former Soviet republics (Zakharchenko Reference Zakharchenko2009). In this context, transparency projects are positioned as part of the movement for “democratization” and against “corruption.” The organization Transparency International, which was founded in 1993, has developed a ranking system to measure governmental corruption, an early use of metrics.

The language of transparency also became enfolded into emerging audit culture in the 1990s (Power Reference Power1994; Shore and Wright Reference Shore and Wright1999; Strathern Reference Strathern2000), both as a normative discourse and as a set of tools and institutions. For instance, in 1999, Shore and Wright, in speaking of the particular iterations of audit culture within British higher education, wrote: “Foremost in the new semantic cluster associated with audit culture are ‘transparency’, ‘accountability’, ‘quality’ and ‘performance’, all of which are said to be encouraged and enhanced by audit” (Reference Shore and Wright1999: 566). In this sense, the language of transparency provides the discursive infrastructure for audit culture in its various iterations. In addition to these semantic uses of the language of transparency, technologies of transparency have emerged in multiple areas. These include systems of certification that attest to the ethical sourcing of commodities; the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative standard, to which national government can sign up to improve transparency surrounding revenues from oil, gas, and mining; and chain of custody protocols and infrastructures – including, as we will see, digital technologies like blockchain. This chapter attends briefly to the ways in which a language of transparency is deployed (as, for instance, by Thiele, in the article discussed above) in order to help establish the gold market as ethical and ethics as a meaningful component of the gold market, and then moves to a discussion of several technologies of transparency in supply chains and in the verification of gold in central bank vaults.

Transparency’s trajectory has brought it to the realms of gold mining, refining, transport, and finance. In recent years, the hidden aspects of gold’s expressions as a global value (its presence and location in vaults, the London Fix Price, the OTC marketFootnote 9 in London, its use in arms dealing and narcotrafficking) have come under increasing scrutiny. Within these contexts, transparency emerges as both the idiom through which those who insist on knowing more about how gold moves through the world operate, and also the procedures and infrastructures by which those who are invested (literally and figuratively) in gold seek to defend themselves. These actors use transparency to combat “political risk,” to broaden markets for gold through “ethical marketing” techniques and pronouncements, and to sidestep governmental regulation; at a broader level, they seek to shore up its status as a global value. The article by Carl-Ludwig Thiele and the “steps to increasing transparency” it describes reflect one example among many of these attempts to use transparency to shore up gold, even as the article also uses gold to ratify transparency. In what follows, I briefly discuss three sites where processes of transparency intersect with gold, paying particular attention to how both are made and unmade as global values through these intersections.Footnote 10

Supply Chains

One such site, with an accompanying set of technologies for creating transparency, is the gold supply chain from mine to refinery to market. These technologies include certification schemes – that is, methods by which consumers can learn the path that gold has taken from the mine, and through which different origins for gold are (putatively) “certified.” Many of these are collected in the OECD’s Due Diligence Guidance (OECD 2016). They can been used to ascertain (ideally) that the gold is “conflict-free” – that is, not sourced in areas that are “identified by the presence of armed conflict, widespread violence, including violence generated by criminal networks, or other risks of serious and widespread harm to people” (OECD 2016: 66) These systems occur at all points in the supply chain, though many are concentrated at the refinery or “choke point” stage, and refineries are now compelled by the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) to follow its “responsible sourcing guidelines” as a condition for inclusion in the Good Delivery List (a list of accredited refineries, previously focused only on questions of gold purity and security).Footnote 11 In the words of Matthieu Bolay:

Through the idioms of transparency and responsibility, such initiatives [guidance frameworks, certification systems, and other technologies for ensuring that gold extraction and circulation follow ethical norms] pretend – although selectively – to render visible and legible the social life of gold and the networks that brought it into being prior to its legitimate and licit status as a commodity or financial asset.

Not surprisingly, gold supply chain certification programs range widely in their restrictiveness and are also frequently criticized either for being too utopian or as corporate “greenwashing.” This is, of course, a localized version of arguments that are common throughout the domains of ethical supply chains, fair trade, corporate social responsibility, and business and finance more generally (Falls Reference Falls2011; Kirsch Reference Kirsch2014; Rajak Reference Rajak2011; Reichman Reference Reichman2011; Tripathy Reference Tripathy2017; West Reference West2010). As in these other cases, there is a fundamental instability at the heart of these endeavors; as soon as a particular certification garners the support of corporations, it tends to alienate many activists, more or less by definition. Put in the terms I have been using in this chapter, the challenge of certification lies in the tension over whether values of transparency (and related concepts of ethics and accountability) and gold (as something produced and promoted by global corporations) are opposed or aligned.

Over the past eight or so years, the position of mining companies and member associations such as the WGC and the LBMA has shifted dramatically toward supporting certification and, at least nominally, greater transparency in general. To a significant but difficult to measure degree, their response has been provoked by the emergence and strengthening of guidance frameworks for responsible gold production such as the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) and Earthworks’ “Golden Rules” (part of its “No Dirty Gold” campaign), which tend to operate outside the industry or, in the case of IRMA, with only a few relatively small mining corporations participating.

Greater attention to responsible mining has been evident through the course of my research, including at the two LBMA conferences I have been able to attend. At the LBMA conference in 2014, there was a post-conference “Responsible Gold Forum” co-sponsored by the LBMA and the Responsible Jewelry Council, which lasted about two hours. Since many attendees were either leaving for the airport or socializing with colleagues, it was only sparsely attended. In one session, presenters were immediately put on the defensive by a member of the audience who complained that the acronyms and jargon of the proposed certification process were too hard to remember.

In 2018, one of the eight sessions and a keynote speech in the main conference were devoted to ethical concerns and transparency. In the panel session, entitled “Gold Bar Integrity Up the Supply Chain,” the deputy director of the NGO Enough Project, which works primarily in Congo, spoke to a robust audience about supply chain transparency to ensure conflict-free precious metals. Later, an executive of the WGC remarked to me that inviting a member of an NGO of this type (i.e., independent of a corporation or member organization) would have been unthinkable a few years before.

Within the industry, reasons given for the benefits of greater transparency are pragmatic as well as ethical, at least once one leaves behind the realms of websites and presentation slides. Van Bockstael argues:

[M]any current initiatives that are being supported by key players in the mining industry are promoting a host of principles dedicated to sustainability, but can also be seen as a way of insulating the “responsible” members of the mining industry from those who, by omission, are less so and who could, in the future, be responsible for the next environmental disaster due to mismanagement, or provide the spark for the next big activist campaign due to links with unsavoury regimes or atrocities.

Here, we can see a strategy of calculated display, not only as an act of compliance and ethical consideration, but also as a shield to protect other, more enclaved and opaque processes that may not be so ethically oriented.

Since these two conferences, the WGC, the member organization for the majority of the world’s medium and large gold-mining companies, has worked to produce information and strategies to bring transparency and related “responsible” practices to the gold market. In 2019, the WGC launched the Responsible Gold Mining Principles (RGMP), a framework of principles and guidance for its member companies with respect to mining and the supply chain.

Terry Heymann, chief financial officer for the WGC, who also oversaw the development of the RGMP, describes the framework in the publication Climate Action as “an overarching framework which sets out clear expectations to investors, consumers and downstream users as to what constitutes responsible gold mining” (Cooper Reference Cooper2020). The RGMP sets out ten principles, divided into “Governance,” “Social,” and “Environmental” (following the now canonical division within ethical/responsible business and finance). Issues related to transparency of supply chains, impact, and revenue are covered primarily in the first three and the tenth principles.

The RGMP comes with several supporting tools, including an “assurance framework” to help with implementation and oversight and a benchmark comparing the RGMP and the framework from the International Council on Mining and Metals (also a member organization, but for metals-mining companies more generally, not only gold-mining companies).

These “frameworks,” “guidances,” and “benchmarks” seek to perform a hortatory function and to set out a common set of standards for what responsible gold mining would look like. These are necessary technologies for building transparency or other forms of ethical practice, but they do not get into the specific details of how these can be met.Footnote 12

The WGC website states that “Conformance to the RGMP is a requirement for membership in the World Gold Council”Footnote 13 and the principles have achieved broad-based support as a metric used by companies to demonstrate their compliance with its goals, and maybe also to work toward greater compliance.

Blockchain

One rapidly emerging area for handling the details has been blockchain technology. The 2018 LBMA conference featured a slew of companies touting blockchain technology in a whole slew of applications, but especially to guarantee a transparent and clean “chain of custody” from mine to refinery. This guarantee is crucial to most precious metal certification schemes, and since refineries often bear the brunt of costs of certification, there is a strong interest in increasing trustworthiness and lowering costs at that stage of the journey (Bolay Reference Bolay2021).

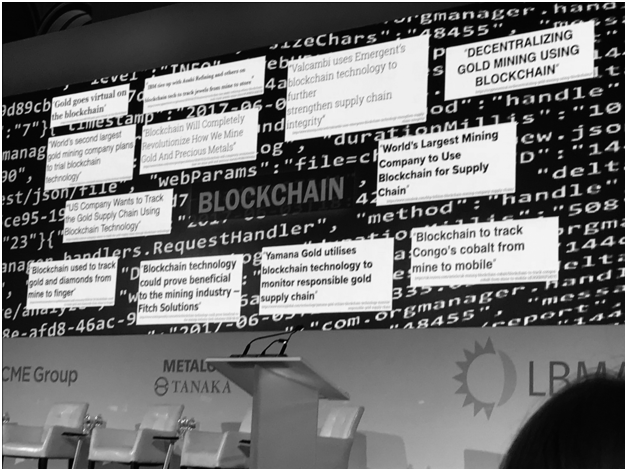

Blockchain technology purports to provide this by means of a digital, distributed ledger that supposedly cannot be hacked. At the 2018 LBMA conference, as I mentioned above, there were numerous vendors advertising blockchain technology, as well as a keynote speaker and panel participant presenting on the possibilities of using the technology for greater transparency. A presentation by Sakhila Mirza, General Counsel for the LBMA, on “Gold Market Integrity” discussed at length the capacity of “technology” to create transparency while also ensuring the continued capacity for discretion in the highly specialized and secretive gold OTC market. Her presentation concluded with a call for proposals on how best to meet the requirements without exposing market participants too much (how to negotiate the divide between secrecy and display). Figure 7.1 is a slide in her presentation demonstrating how much blockchain technology is expected to be part of this solution.

Figure 7.1. A presentation slide from the LBMA meeting, 2018.

In fact, using blockchain technology to bring transparency to the gold supply chain isn’t so easy to do, especially along the lines of the “private” or “proprietary” solutions I saw advertised at LBMA. Filipe Calvão notes this contradiction, saying: “The notion of centralized or permissioned database locations, which is to say, who controls access and dissemination of data, is … at odds with the principles of distributed accountability” (Calvão Reference Calvão2019: 129). One financial technology expert with whom I spoke, who had been invited to the LBMA 2018 conference, confirmed this point, saying:

A lot of what I saw [in the vendor booths] was based on a misguided understanding of what blockchain is. As long as it’s private you are just using an expensive database. You can’t put gold in a blockchain and think you’re putting transparency in the supply chain. You can’t truly put something on the blockchain, you’re just using the system as a pointer.

That is, you can record bars of gold in a database structured by blockchain technology, but there will be points of weakness in the system – who logs it in, how the bar is labeled or identified – so the very reason why you would use blockchain in the first place is lost.

Acknowledging this need for “human appreciations at the entry point” of digitized information on gold into the blockchain, Bolay (Reference Bolay2021: 97) also foregrounds other ways in which the technology creates new kinds of actors, networks, and possibilities, including the simultaneous storage of digitized information concerning gold’s movement through the chain of custody and the process of creating digital slices of gold as a transferable asset, or of the ethical inscriptions linked to it (as, for instance, conflict-free gold) through the process known as “tokenization.” Asset tokenization is a current trend in financial technology or “fintech” that has opened new possibilities for rendering gold as a physical object divisible and liquid through creating a “digital double” (Bolay Reference Bolay2021: 99) on a blockchain.Footnote 14

In an article in the journal Political Geography, Filipe Calvão and Matthew Archer (Reference Calvão and Archer2021) examine the ways in which blockchain technologies have proliferated in mining industries, arguing that these modes of creating, managing, and owning data by digital means are “parallel but … increasingly inextricable from the material extraction of minerals, developed under the banner of blockchain-based due diligence practices, chain of custody certifications, and various transparency mechanisms” (2). Like my interlocutor, they also note that, “in contrast to public blockchains like Bitcoin, these are primarily private blockchains that operate as permission-based centralized ledgers” (3). Not only do these “expensive databases” not provide the transparency and accountability they promise, Calvão and Archer show that they also carve out new channels by which value can be extracted from commodity chains, often in highly opaque and unaccountable ways.

In the past few years, it seems some of the buzz over blockchain as a technology for bringing transparency to gold supply chains has diminished (as we see with other “use cases” for blockchain), partly because the challenges and costs of implementing it at scale have become more evident. A November 2023 article in the environmental journalism magazine Mongabay outlines these challenges and costs in Brazil, noting that “blockchain shouldn’t be viewed as a panacea to an industry rife with social and environmental risks” (Espinosa and Lyons Reference Espinosa and Lyons2023).

Central Bank Vaults

As I have introduced above, transparency projects have also been coalescing around the verified presence of gold in (especially European) central bank vaults. And these, too, show us the process by which vying values of gold and transparency can at times be brought into (uneasy) alignment and at times work to undermine each other. For one thing, a dynamic by which transparency projects are made publicly visible – the ways in which they are performed – happens in all domains where transparency operates but intersects with gold in particular ways. For one thing, gold as a global value manifests, and arguably depends on, an oscillation between display and secrecy, at times flashing out spectacularly and at other times hidden away in vaults, graves, or hoards. This aspect of gold has been noted by several anthropologists, including Maurice Godelier (Reference Godelier1999) in his use of gold to demonstrate the “enigma of the gift,” which he sees as a dialectic between keeping and giving away (see also Weiner Reference Weiner1992), and Gustav Peebles, for whom gold operates as a key example in his re-theorization of “the hoard” as a fundamental principle of banking (Peebles Reference Peebles2014; see also Ferry Reference Ferry2020).

In an article in the journal Cultural Geographies, Erica Schoenberger draws on diverse archaeological and ethnohistorical sources to show how gold’s scarcity has been enhanced at certain moments through artificial restriction of its supply. Among other sites, Schoenberger points particularly to the necropolis of Varna in what is now Bulgaria, which dates to the fifth millennium BCE, in which large quantities of gold were sequestered in what she describes as “self-cancelling supply” (Schoenberger Reference Schoenberger2011: 7). That is, by burying gold, Varna’s chiefs simultaneously demonstrated their power and removed gold from circulation. While Schoenberger’s emphasis falls on the notion of socially constructed scarcity, the material she presents also suggests a counterpoint between display and removal from display. The golden objects associated with royalty are frequently displayed on ceremonial occasions such as coronations and weddings, but are then removed from display by being buried and placed in vaults away from public view. The process of “self-cancelling supply” described by Schoenberger can also be seen as a process of revealing and removing from view.

Schoenberger concludes her discussion by noting how the pattern of sequestering gold by burying it in tombs continues into the twentieth century with the practices of holding gold reserves in central banks. She writes, “From the graves of Varna to the underground vaults of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the history of the social value of gold is in part a history of different ways of creating artificial scarcity” (Schoenberger Reference Schoenberger2011: 19).

For one thing, between 1999 and 2019, many central banks signed a collective agreement restricting how much they could sell, in recognition of the potential to destabilize the gold price by flooding the market (as happened in the late 1990s). The WGC described this predicament and the agreements that have been developed to manage it thus:

Collectively, at the end of 2018, central banks held around 33,200 tonnes of gold, which is approximately one-fifth of all the gold ever mined. Moreover, these holdings are highly concentrated in the advanced economies of Western Europe and North America, a legacy of the days of the gold standard. This means that central banks have immense pricing power in the gold markets.

In recognition of this, major European central banks signed the Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA) in 1999, limiting the amount of gold that signatories can collectively sell in any one year. There have since been three further agreements, in 2004, 2009 and 2014.Footnote 15

This need to restrict the circulation of gold, at least periodically, overlapped with gold’s dual role as object of visual display and invisible hoard (Graeber Reference Graeber1996).

In September 2019, the CBGA was allowed to lapse, so banks no longer participate in this voluntary agreement to limit sales on the grounds that the market in gold had grown and matured since the 1990s and that banks had “no plans to sell.” The rationale that the CBGA is no longer needed is based largely on the idea that central banks continue to hold and buy gold, suggesting that the function of self-canceling supply continues to operate, even after the agreement has ended.Footnote 16

Strikingly, central banks – and central bankers – find themselves in a complicated position with respect to the gold reserves they hold. Because of the shift in gold’s position in the global economy since the end of dollar–gold convertibility in 1971 (as discussed above), the importance of gold as a national asset has inarguably declined, although observers differ by how much. Those who are more attached to the idea that gold has intrinsic value and who mistrust the very concept of “fiat money,” not surprisingly, feel that stewardship of gold reserves remains a critical task for central banks. Others – perhaps including many central bankers – are agnostic about or skeptical of the sound money thesis but recognize gold’s cultural and symbolic force, which make it a telling barometer for global crisis or instability.Footnote 17

Indeed, most central bankers, arguably, see the management of the money supply as a far more important dimension of their job.Footnote 18 As one interlocutor, former chair of a European central bank (though not one with large gold reserves), told me, “When I talk with other [central] bankers, we find gold a bit of a nuisance. We wish we could get rid of it.” Nevertheless, central bankers must, at least nominally, respond to the public pressure to keep the gold they have. In addition, central banker must be extremely careful about any information or publicity connected to their gold holdings. Public statements concerning gold in central banks tend toward “managed transparency,” including carefully timed press releases, public statements, and photographs demonstrating their careful stewardship of the nation’s gold supply.

The Deutsche Bundesbank gives a good example: in the face of (mostly right-wing) pressure to move the gold holdings housed in New York and Paris back to Frankfurt, framed in terms of a lack of transparency and a sense that perhaps the gold “wasn’t really there,” the bank instituted a transfer (called by some outside the bank a “repatriation”), which was completed in late 2017.

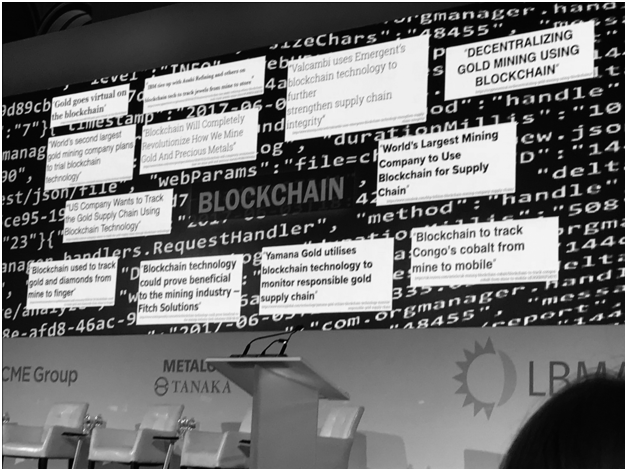

The many interviews, articles, press conferences, and other media artifacts (including the Gold Investor article), and the book and museum exhibition that accompanied its completion, can be seen from several angles: as full-throated celebrations of gold; as demonstrations of the bank’s “increased [though necessarily limited] transparency”; and as protections against the potential liabilities of gold as a kind of anti-value (as Van Bockstael argues above). These public performances of gold’s presence and the transparent actions that allow the gold to “shine forth” draw on powerful ideas about materiality (including qualities like mass and shine) and value as tied to white male and European bodies. Figure 7.2, an image included in an article on the Bundesbank website announcing the completed transfer of Germany’s gold from New York in 2016 (the transfer from London was completed in 2017), brings together a lustrous gold bar and some kind of testing or logging tool (which also looks a bit like a jeweler’s loupe, suggesting that its purpose is to “see” the gold either literally or figuratively) with the date of the bar and the word “Switzerland” (where the most trusted refineries are concentrated). In this image, transparency, accountability, gold, whiteness, and maleness converge in a coordinated act of making value.

Figure 7.2. Gold bars at a press conference, Deutsche Bundesbank, 2017.

Transparency infuses gold with value in each of the three areas I have described, but with different histories and different effects. As I suggested above, the frameworks for responsible and ethical supply chains fall within a broader range of attempts to establish ethical value chains for many different commodities and can be seen as and analyzed in terms of pressures from nongovernmental organizations, activist groups, and consumers concerned with environmental and social justice. Blockchain technologies are mobilized to meet these ends but also participate in other conversations with other concerns, such as freedom from governmental interference and the “transparency” of distributed ledgers, as well as the increased liquidity of digital assets, with the promise of a more “transparent” field for investment in gold. The transparency work done by central bankers is oriented somewhat differently, toward finding new solutions to a perennial problem they face – how to perform gold’s “real” presence in their vaults while also keeping it secure. These varied audiences and aims sometimes align, but not always. By viewing them next to each other, I hope to have highlighted the ways in which transparency and gold converge and vie against each other as global values.

Gold’s fortunes in mining and finance are up in the air these days. In mining, gold faces what companies and investors call “political” or “reputational” risk, narrow profit margins (especially as new technologies of transparency become more necessary), and impatient investors. In finance, actors vie to shore up its place as a globally recognized and trusted asset, or to relegate it firmly to a humbler place, according to its relatively restricted use values in jewelry and technologies, and as one among any number of commodities on which to build derivative contracts (futures, options, etc.). In these stormy seas, languages and techniques of transparency are conscripted to right gold’s ship, and, in doing so, to solidify transparency itself. As in other exercises in imperfect commensuration, gold and transparency both align and grind gears; in doing so, as David Graeber has written, they “bring universes into being” (Reference Graeber2013).

Transparency is a term inseparable from the idiom of sight and vision. The connotation is that being able to see through – to something true, authentic, and real – and being able to see clearly are necessary qualities of transparency, both as applied in this volume and as a sensory experience. It is a commonplace that for human beings the visual dominates all other senses, or at least that humans typically construct “sight-dominated cultures,” although this is not an unvarying characteristic (see Hutmacher Reference Hutmacher2019). Historically speaking, anthropology may be a particularly visually dominated discipline (see Goody Reference Goody2002); this is evident in the universal acclamation for an emphatic seeing-is-believing methodology, “participant observation,” and the manner in which the visual is the central component in the ethnographic trope of arrival. While some anthropologists developing “the anthropology of the senses” claim “to have dethroned vision from the sovereign position it had allegedly held in the intellectual pantheon of the western world” (Ingold Reference Ingold2011: 316), the elaboration of transparency does not contest the domination of the visual for us humans or for the anthropologists in this volume, such as myself. We instead agree to travel down the road with the refined sensibility of seeing, analyzing, and critiquing transparency, as a social fact, and transparently, as our analytic parameter, in the worlds that we contributors have explored. I write about my attempts to see processes by which mining is initiated, the valuation of different minerals, and the manner in which mining and minerals are instrumental to nation-building in my periods of ethnographic observation in Greenland, which have been brief: a month in 2019, a month in 2021, and in between, remote research and communication dictated by the conditions of the pandemic. In this research, climate change, natural resource extraction economies, and nation-building are all on view, so to speak.

I am not sure if, with respect to the topics I engage in this chapter, there is a definitive expression of what “seeing transparently” means for an outsider to Greenland, or what it might mean for an anthropologist. For that reason, I have opted to use the metaphor of different lenses. Lenses offer different visual perspectives from which to look into complex situations. In this article, the lenses focus upon four situations demarcated by: (1) the centuries of Danish colonization and ongoing coloniality; (2) more than four decades of advance toward the establishment of an independent nation in Greenland; (3) the development of gem mining involving both small-scale artisanal miners and resource extraction corporations; and (4) the globalized corporate push to mine rare earth elements that are central to the development of green technologies. In each case, transparency can be related to forms, levels, and mixtures of disclosure and nondisclosure by different interlocutors, which surface (or do not surface) in environmental studies and impact statements, corporate brochures, statements made and policies enacted by governments, and the critiques leveled by environmental organizations and small-scale miners.

I organize this chapter, then, keeping in mind the primacy of the visual as a project of transparency, recalling what we experience when we visit the optometrist and we are asked, as we look through different lenses that are exchanged and inserted into the strange machine in front of which we sit: Is the first lens or the second lens clearer? The third or the fourth? Arranged as elaborations of a sequence of lenses, I ask readers (and myself) which lenses make things clearer, and in what ways. In what follows, it should be clear as well that, notwithstanding the profound role of colonialism and its enduring aftermaths that suffuse each lens of transparency and opacity, the people of Greenland are not victims. They are not intrinsically vulnerable to a marauding modernity that by its very nature must corrode their identity, such that outsiders, like anthropologists or other scholars, can maintain a stance that understands what is going on in Greenland as describable by loaded terms such as “adaptation,” whether that refers to climate change or to the politics of postcolonial transformations (see Nuttall Reference Nuttall2010).

Lens One: Greenland’s Colonial History and Trajectory Toward Independence

In twenty-first-century Greenland, the collective imaginary is dominated by the goal of nationhood via full political independence from the kingdom of Denmark. All of the political parties proclaim that goal, although they propose or assert varying timelines and caveats about how much of a relationship with Denmark might or should be maintained. The great majority of Greenlanders are indigenous Inuit people whose ancestors migrated from the northern reaches of what is now Canada and Alaska after 1200, and who are the successors to a host of other indigenous peoples who have inhabited the land since at least 2500 BCE. Greenland’s lengthy relationship with Denmark is complex: Danes arrived on Greenland’s shores in 1721, in search of the Norse colonies that had been settled by Icelandic farmers at the end of the tenth century. Unbeknownst to the Danes, who were very much motivated to find the Norse descendants to convert them from pre-Reformation Catholicism to Denmark’s state religion of Lutheranism, those colonies had disappeared in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Danes instead converted the indigenous people, who are almost all Lutheran to this day; almost all have Danish surnames, many have some Danish ancestry, and Danish remains a dominant language (Rud Reference Rud2017). In these ways, Greenland is both a Nordic country and a colonized territory attempting to become the independent country of an indigenous people (see Dahl Reference Dahl and Wessendorf2005; Gad Reference Gad2009; Mazza Reference Mazza2015).

Home-rule government in Greenland was established by the Danish state in 1979 and further strengthened by self-rule provisions that the Greenlandic population voted in favor of expanding in 2009. Denmark provides the Greenlandic government with a block grant of a little less than $550 million each year. That might not sound like much in US economic terms, but the total population of Greenland is only a little more than 56,000 people. The home-rule government established Greenland’s nationhood. The official language is Greenlandic, in which the country’s name is Kalaallit Nunaat. Its flag and many other aspects of sovereignty, both substantive and symbolic, have been determined by the home-rule government, which initially controlled everything except foreign relations, defense, currency matters, and the legal system. With self-rule in 2009, the Greenlandic government gained control over the legal system and some aspects of defense, and increasingly Greenland conducts its own foreign policy – with Iceland, Canada, the United States, and, perhaps most importantly, China. Independence, the Danish government has made clear, will mean the end of the block grant, which at the current time the Greenlandic government deploys as it sees fit (Sejersen Reference Sejersen2015). Denmark is willing to phase out the block grant in stages as Greenland’s economy becomes self-sufficient, and has specified how much the block grant will be reduced as Greenland’s economy expands (Nuttall Reference Nuttall2017; Rasmussen and Gjertsen Reference Rasmussen, Gjertsen, Dale, Bay-Larsen and Skorstad2018).

Throughout the history of indigenous peoples in Greenland, food has been produced through strategically honed mixtures of hunting land and sea mammals and fishing numerous species; therefore, unlike most any other emergent national identity and nationalism that I know of (Rud Reference Rud2017), in Greenland the nascent nation-state is entirely divorced from an agrarian or agricultural imaginary.Footnote 1 At the same time, the contribution of local hunting and fishing to the daily diet of most Greenlanders has diminished drastically in relation to the central role of imported foods, and these two activities are very unlikely to ever produce the income needed to diminish Greenland’s dependence on Denmark’s block grant. For the political-economic class that rules the country, for whom, as Nuttall (Reference Nuttall2010) and Sejersen (Reference Sejersen2015) point out, anticipation about the future of Greenland is a subject of continuous debate, the shortest and surest route to self-sufficiency seems to be a resource economy based upon mining and fossil fuel extraction. Moreover, in Greenland, the development of an extractive economy is linked with an effort “to secure a collective safety net, a kind of livability for the future that involves an apparatus for redistribution, even if that is knitted at the expense of local resource practices and environmental integrity” (Hastrup and Lien Reference Hastrup and Lien2020: xv). The fusion between an extractive economy and a welfare state society, which Hastrup and Lien call the “welfare frontiers” of Greenland and other parts of the Nordic countries, also brings together very different regimes of transparency – or a lack of transparency. Prior to 1979, decisions about extraction, and economic development as a whole, were entirely in the hands of the Danish colonial authorities – and, by virtue of their nondisclosure to Greenlanders, they were certainly not transparent (see Rud Reference Rud2017). How much home-rule, self-rule, and the horizon toward full independence have addressed that opacity is explored in what follows.

Lens Two: A National Economy, Resource Extraction, Infrastructure, and the Technical Fix

Mining and large-scale industry are part and parcel of Greenland’s colonial history and nation-building present. Since the nineteenth century, when Denmark closely controlled the economy, and into the twentieth, mining has appeared on Greenland’s conceptual horizon both as a very real manifestation of colonial development and as an illusion or unrealizable dream of great wealth, which in the twenty-first century would be the basis for independence. In the case of the former, the mining of cryolite, a mineral that was essential to the purification of pure aluminum from mineral bauxite all over the world until a substitute was developed, was conducted in southern Greenland from 1854 until the deposit was exhausted in 1987. The essential contribution of Greenland to the industrial production of a key metal resource was therefore anything but an illusion. Yet resource and infrastructure megaprojects in Greenland often do not come to pass (see Nuttall Reference Nuttall2010; Reference Nuttall2012; Reference Nuttall2017; Rasmussen and Gjertsen Reference Rasmussen, Gjertsen, Dale, Bay-Larsen and Skorstad2018), and, as Hastrup and Lien write, “Resource imaginaries, in other words, are not that easily realized, and sometimes are just that: imaginaries” (Reference Hastrup and Lien2020: xii).

Massive resource extraction projects and the worlds of infrastructural construction that accompany them are discussed in technical terms worldwide; these are discourses that are explicitly ideological and political, linked to particular outcomes and visualizations of the future. In recent literature about the phenomenal economic and political power of the Gulf state monarchies, Günel, for example, has described “technical adjustments”:

Abu Dhabi’s renewable energy and clean technology projects, such as Masdar City, have aimed to generate technical adjustments as a means for vaulting ahead to a future where humans will continue to enjoy technological complexity without interrogating existing social, political and economic relations … Technical adjustments, which are intended to maintain existing values while inventing new technology to address climate change and energy scarcity, operate in opposition to environmentalism. The hope is that technical adjustments will allow humans to extend their beliefs and perspectives into the future without requiring them to ask new moral and ethical questions and without developing new virtues.

Kanna (Reference Kanna2011) described similar applications of technical adjustments in what must be called the fantastical development of the city of Dubai, under the rubric of neoliberal globalization, urbanist ideology, and the divas of global architectural design.Footnote 2

Meanwhile, in Greenland, technical adjustments in the form of mega resource extraction and related infrastructure projects are also seen as a fix, but that strategy is not necessarily seen as enabling a wholescale sociopolitical inertia, as Günel suggested is the case in Abu Dhabi. The technical adjustment in Greenland renders independent nationhood possible, and facilitates the ascendance of an elite social class and its worldview and values over others; perhaps one might see the technical adjustment as enabling both something new (i.e., Greenlandic nationhood) and simultaneously the entrenchment of the new elite’s values and ethics, as in the Gulf monarchies. On the subject of an enormous aluminum smelting complex that between 2007 and 2016 was intensively planned and designed to be built by the global hegemon Alcoa in the small town of Maniitsoq on Greenland’s southwestern coast, Sejersen wrote:

The technology complex in question (a smelter, two dams, electric transmission cables, etc.) carries with its large-scale systematic socio-technical nature and enormous potential. The astronomical economic investments that are required, its spatial and temporal consequences, and also the political expectations invested in the project gave it a certain momentum … The technology may thus reinforce a particular system of values and relations.

This project would have doubled Greenland’s CO2 emissions and its energy consumption. As part of the planning process, the Greenlandic government assessed the local hunting and fishing industries and the livelihoods they provide for Greenlandic communities. In that context, leading politicians proposed “re-educating” hunters and fishing people for new occupations associated with the aluminum complex (Sejersen Reference Sejersen2015: 124–125). Even without the intrusion of mega resource extraction and infrastructure projects, fishing and hunting in Greenland are already highly regulated by both national and international regimes that limit what can and cannot be caught and therefore consumed.

The processes of consultation by which the planning of the Maniitsoq aluminum complex was executed were intensely fraught; that is to say, they were far from transparent to the residents of Maniitsoq, and likely to the majority of Greenlanders, a characteristic that applies in the discussion of the development of mining projects more recently (see Nuttall Reference Nuttall2013). Sejerson noted:

In November 2010, the Greenlandic environmental organization, Avataq, accused the Greenlandic government of keeping the public in the dark about the human and environmental impacts of having an aluminum smelter.

That accusation, which hinged on the primacy of the visual, provoked demands from the government for proof, which Avataq in turn provided.

In 2020, an article in Arctic Today, a self-described “Arctic business journal,” declared:

The idea of building a hydroelectric plant for industrial production near Maniitsoq was first broached more than a decade ago. Negotiations dragged on due to a disagreement over who should fund its construction, and, by 2016, the administration admitted that it had given up on striking a deal with Alcoa.

Whether or not the lack of transparency, which here signals the government’s nondisclosure about the effects of aluminum smelting, was the main reason the project did not manifest, the debate around the aluminum smelter nevertheless revealed how technical adjustments figured in the ways Greenland’s government and political elite envisioned nationhood and what the Greenlandic people ought to be doing for work. There is, to be sure, the mirage-like character of large-scale resource extractive projects in the Arctic, which I referred to previously, but there is also the disjuncture between the “relative transparency of bureaucratic practices” (Hastrup and Lien Reference Hastrup and Lien2020: xvii) in Nordic countries such as Greenland, on the one hand, and the calculus of profit-driven, behind-closed-doors corporate decision-making for a company like Alcoa, on the other.

Lens Three: Competing Transparencies in Greenlandic Gem Mining

A ruby and pink sapphire mine, owned by the Norwegian-financed Greenland Ruby company, opened at Aappaluttoq in the southern part of Greenland’s vast Sermersooq municipality in 2017. Greenland’s ruby mine operates to produce gems, but also as a synecdoche: a part of the ongoing debate about mining and transparency, which effectually embodies the larger scenario. I would argue this case in two ways. First, the ruby mine as a new venture in resource extraction settles mining as a technical adjustment that supports the Greenlandic nation-building project. Second, Greenland’s ruby mine offers an opportunity to showcase corporate transparency in the soft light of an Arctic Scandinavian setting, for a gemstone that from Myanmar to Mozambique (Brazeal Reference Brazeal, Calvão, Bolay and Ferry2026) carries the weight of nightmarish human rights catastrophes and ugly environmental degradation.

In their glossy pamphlets and website promotional materials, the Greenland Ruby company declares:

Greenland Ruby gems are mined by adhering to the strict ethical, social, human rights and environmental laws and responsible practices. Transparency and traceability are extremely important aspects of our project. Gems come with a certificate or origin authorized and issued by the Government of Greenland. This certificate assures buyers these stones come from an ethical source.

Moreover, the company claims that “10% of the mine’s material is to stay in Greenland for tourist and local operators.” During my 2019 fieldwork season, I asked shop owners who sold jewelry in Nuuk whether their inventory included Greenlandic rubies, either as loose stones or set in particular pieces. There was only one to be found. In fact, in Greenland Ruby’s promotional materials, which one would expect to present the most favorable picture possible, it is at best quite unclear who has specified or will establish these “strict ethical, social, human rights and environmental law and responsible practices,” or how the company is to be held accountable to those standards. Greenland Ruby’s ideas about transparency are based, I would argue, primarily upon the traceability of the stones and legal frameworks mandating environmental policy, all in the context of an international corporate business framework of profitability. As we will see below, that kind of transparency contrasts sharply with a sector of small-scale, artisanal-type miners and gem polishers, who envision an autonomous and agentive role in bringing the stones from the ground to a marketplace that serves their local, Greenland-based set of interests (Brichet Reference Brichet2020).

The corporate domination of ruby mining in Greenland comes on the heels of fifteen years of contorted events and turnarounds, following the discovery of the deposit at Aappaluttoq by US geologist William Rohtert in 2005, at a time when ruby crystals, apparently quite a few of extremely high quality and potentially great value, could be picked up on or just below the surface. An extended struggle ensued in the pre-2009, pre-self-rule era. On the one hand, local residents claimed the right to gather and sell rubies as well as claiming to have had previous knowledge about them in that region; on the other hand, the first company to propose the mine, the Canadian-owned True North Gems, together with the Danish Bureau of Mines, actively repressed those locals’ gathering activities through a series of arrests and temporary detentions, confiscating many of the finest-quality gems that had already been gathered.Footnote 3 In this battle, so-called historical stones – that is, valuable stones collected before the self-rule government’s establishment of local laws and licensing in 2009 – were considered illegally mined, making current and past sales of such valuable stones mined before that date also illegal. True North Gems went bankrupt in 2016 following the scandals produced by these battles, but it was not long before the Greenland Ruby company was formed, and the same leases and permits were utilized to open the mine in 2017.

At the time Rohtert discovered the Aappaluttoq deposit in 2005, Greenlanders could apply for and receive licenses to take gems out of the country, to trade shows, and to sell them, under the 1999 Mineral Resources Act of Greenland, as administered by the Bureau of Minerals and Petroleum (BMP), which was still under Danish control. A local enthusiast group, the Greenland Stone Club, was regularly issued such export licenses. Ironically, Rohtert was one of the co-founders of True North Gems, the company with which the BMP colluded to restrict Greenlanders’ ability to gather rubies and sell them, which later led to arrests, confiscations, and detentions.

As reported on the Fair Jewellery Action website,Footnote 4 Rohtert was accused and charged with smuggling rubies out of Greenland in 2007, and detained by the police at the request of BMP. Earlier that year, he had been discharged from True North Gems after evaluating a large sample of rubies from Aappaluttoq and assigning them high wholesale values that were previously noted. Rohtert had also convinced True North Gems to fund gem prospecting, cutting, polishing, and jewelry design courses in Greenland, the first of their kind, which have had a ripple effect in the ensuing years as those who were trained in these classes in turn train friends and relatives.Footnote 5 His goal had been to create employment opportunities for Greenlanders, and to make it possible for Greenlanders to sell gems at the highest possible prices. Following his replacement as the project manager for Aappaluttoq, the gemstone cutting and polishing courses were discontinued and locals living near the deposit were informed, in spite of earlier assurances from BMP, that they were no longer allowed to prospect for rubies from either the exploitation or the exploration zones where True North Gems was operating. The rubies in True North Gems’ possession were without explanation re-evaluated as much less valuable, which not coincidentally reduced the projected revenue from the mine and the tax contributions that could be expected to the Greenlandic economy. A resonant ordeal unfolded for Greenlanders Niles Madsen, Christian de Renouard, and Thue Noahsen, among others, all of whom had worked with Rohtert and had extant collections of valuable rubies and had tried to continue their gathering activities. BMP, in collusion with True North Gems, had these individuals banned from such activities and from selling any gemstones in Greenland or abroad.Footnote 6

These events led to an international outcry and very bad press for the Greenlandic mining industry, and then to the founding of an activist group, the 16th August Union, named for the day a helicopter with armed police on board confronted Madsen at the site and banned his presence there. Subsequent and significant political and economic involvement and investment ensued, led by a fair trade organization, Fair Jewellery Action, based in Santa Fe, New Mexico. A petition supporting the local people who had been banned and had had their rubies confiscated collected signatures from almost 5 percent of the Greenlandic population in less than three weeks. In 2009, the Greenland ombudsman reviewed the Madsen case and decided that BMP had acted inappropriately. That same year, Greenlanders voted to endorse self-rule, and the new government began drafting new policies that affect small-scale mining and the sale of gems.

For the rubies of Greenland and the possible benefits of rubies for Greenlanders and Greenland, this is not a story that necessarily ends negatively, at least not so far. Perhaps in the context of gem mining and transparency, there are only comparatively better or worse outcomes rather than outcomes that can be seen as unmitigatedly positive or negative. For example, the current conditions for ruby mining and for ruby miners in both Myanmar and Mozambique (Brazeal Reference Brazeal, Calvão, Bolay and Ferry2026) are by comparison very much more negative. In Greenland, while, as indicated, there are many reasons for skepticism with respect to the large-scale corporate mine run by Greenland Ruby and its pledges to conduct itself according to standards of social and environmental responsibility, small-scale miners such as Ilannguaq Lennert Olsen, whom I interviewed, express a certain degree of optimism that, in Greenland, the mining of gems could be conducted in such a way as to include small-scale miners. A few years ago, Fair Jewellery Action and the 16th August Union drafted a comprehensive report entitled Creating a Prosperous and Inclusive Gem Industry in Greenland (Lowe and Doyle Reference Lowe and Doyle2013), with very specific and concrete policy recommendations that support what Ilannguaq is doing as president of the Nuuk Gemstone Guild (in Greenlandic, the Nuummi Ujaqqer Institute Peqatigiiffiat).

In a 2018 interview with the most widely read Greenlandic daily, Sermitsiaq, conducted by the newspaper’s chief editor Poul Krarup, Ilannguaq noted that post-2009 positive legislation has in fact created a licensing system that facilitates small mining by Greenlanders in the areas where rubies have been found, although these areas exclude the concession zone granted by the Greenlandic government to the Greenland Ruby company (Krarup Reference Krarup2018). From our conversation, I concluded that what is still lacking is the human and technological infrastructure that could make finished products of raw rubies. “We must help each other to invest money in both extracting and polishing many of our different gemstones,” Ilannguaq commented. “We Greenlanders are good with our hands. I believe also that many could easily learn to facet gemstones.” Ilannguaq worries that the laws in Greenland still do not adequately protect small-scale Greenlandic miners, and eventually gem cutters and polishers from foreign investors will attempt to conclude agreements that create exclusive relationships of dependency with and monopoly control over Greenlandic “partners.” One step in the direction that Ilannguaq and his guild support was the government’s Ministry of Raw Materials drafting a “Country of Origin” certificate, for which, one may recall, Greenland Ruby appears to take credit in its promotional materials. Ilannguaq’s organization is dedicated to substantive support for training and education for small-scale miners in the value-added industries of cutting, polishing, and ultimately jewelry design and manufacture. In my own interview with Ilannguaq in 2019, we imagined a situation in which Greenlanders mine rubies, Greenlanders polish and facet rubies, Greenlanders design and create jewelry with their rubies, and the rubies themselves are of such high quality that they are not subjected to the heat treatment that almost all corundum gems receive in Thailand, where the vast majority of stones are sent to be processed. The Greenlandic rubies we imagined would be the most valuable in the world. As Brichet (Reference Brichet2020), writes, such an imaginary is already decades old.

When the process that led to a ruby mine in Greenland began, it very much seemed like the companies involved operated opaquely, making claims about high ethical standards and traceability which were, at best, difficult to substantiate, but which nevertheless made for good public relations. But the development of legible standards in the legal frameworks of Greenland’s self-rule government has advanced, a development that may not be perfect but does demarcate traceability and the conditions of extraction. The changes are complex. By 2021, Greenland Ruby had opened a store in the Nuuk Center, the city’s prestigious shopping emporium, where one could purchase loose stones and also jewelry designed and produced by Greenlander artisanal jewelers. To what extent these developments responded to the experiences and interventions of Ilannguaq, Fair Jewellery Action, and the 16th August Union is not evident. In 2023, Ilannguaq was hired by the government of Greenland’s Ministry of Natural Resources (formerly the BMP), and his intention is to transform the laws regulating small miners.Footnote 7 At the same time, a recent public publication by Greenland Ruby repeats the same obfuscations regarding the history of ruby mining in Greenland and the same unsubstantiated claims about transparency (Henning Reference Henning2023: 48–49). More seriously, the Greenlandic daily Sermitsiaq reported in 2022 that Greenland Ruby was $100 million in debt and had yielded only $10 million in sales since production started at Aappaluttoq.Footnote 8 In 2023, the mine shut down (McLemore Reference McLemore2023), and in 2024, Greenland Ruby put the mine up for sale (Jeffay Reference Jeffay2024).

To repeat Hastrup and Lien’s wry observation, “Resource imaginaries, in other words, are not that easily realized, and sometimes are just that: imaginaries” (Reference Hastrup and Lien2020: xii). At the same time, the role played by Greenlandic miners and their allies like Rohtert from the beginning of the Greenlandic ruby industry to the current moment of uncertainty has interjected a demand for and a version of a kind of transparency that contrasts with that of the corporate entity and creates an unstable dynamism between the two. In the mining of rare earth elements that I discuss next, the confrontation with transparency is more stark and the stakes much higher.

Lens Four: The Opaque Worlds of the REE Economy

Not far from Aappaluttoq, and located in the far south Kujalleq municipality, sharply debated megaprojects center around two deposits of rare earth elements (REEs) that are closely located to one another: Kvanefjeld (in Greenlandic Kuannersuit), next to the town of Narsaq; and the Tanbreez mine Kringlerne, or Killavaat Alannguatin in Greenlandic, which is near the larger town of Qaqortoq.

The global market for REEs is highly constrained by China’s stranglehold over both the mining and the refining of these strategic elements; China produces up to 90 percent of REEs (Gronholt-Pedersen and Onstad Reference Gronholt-Pedersen and Onstad2021). There is certainly a drive, led by the US and the EU, to break or at least evade the Chinese monopoly on these high-value metals. The planned mines at Kvanefjeld and Tanbreez would exploit extensive, very high-quality deposits of REEs, which “the US Geological Survey says are the world’s biggest undeveloped deposits of rare earth metals” (Gronholt-Pedersen and Skydsgaard Reference Gronholt-Pedersen and Skydsgaard2021). Greenland Minerals and Energy (GME), an Australian-registered company, which is developing Kvanefjeld, describes the proposed mine as “a large-scale rare earth project with the potential to become the most significant western world producer of critical rare earths.”Footnote 9 The four largest shareholders in GME are Citicorp, J. P. Morgan Australia, HSBC Australia, and Leshan Shenghe Rare Earth of China, each of which has purchased a stake between 11.3 percent and 14.3 percent. Tanbreez Mining Greenland is owned by an Australian company which is itself a subsidiary of Westrip Holdings Ltd in the UK (Hansen and Johnstone Reference Hansen and Johnstone2019).

The REEs comprise a complex of seventeen distinct elements with widely varying, essential uses in key technological applications. Among them, neodymium, a prime component of the Kvanefjeld deposit, is used to produce the magnets used in wind energy technologies that are central to sustainable energy production globally; neodymium iron boron magnets are the strongest magnets known and a critical component not only in green energy technologies and fuel efficiency, but also in the miniaturization of electronic devices. Gearless wind turbines use approximately 200–300 kilograms of this element, hybrid cars like the Prius use 1 kilogram, and MRI scanning machines require 1–3 tons of neodymium. The Tanbreez deposit’s REE array is comprised mainly of “lanthanum and cerium – relatively plentiful metals used in telescope lenses and auto catalysts to cut emissions. About a fifth would be yttrium, which is in demand for lasers and the superconductors used in quantum computing” (Gronholt-Pedersen and Onstad Reference Gronholt-Pedersen and Onstad2021).

But neodymium and other REEs are not the only elements that would be purified from the Kvanefjeld mine. The deposit at Kvanefjeld contains not an insignificant amount of uranium ore, perhaps 20 percent of the total ore body; once purified, this can be used in power plants or in the production of nuclear weapons. As early as 1955, the Danish Atomic Energy Commission had identified uranium at the Kvanefjeld deposit, and Danish scientists had conducted technical studies relating to extracting uranium at Kvanefjeld; these studies continued for almost thirty years. Work on the Kvanefjeld deposit was abandoned in 1983 after the Danish government established what has been called a “zero tolerance policy” with respect to uranium and other radioactive materials, which affected all three countries in the Danish realm (Denmark, Greenland, and the Faroe Islands). In 2013, following extensive re-study of the Kvanefjeld deposit and already in the era of enormously increased demand for REEs for wind turbines and other uses, the Greenlandic parliament voted to remove the ban on uranium mining, independently and distinctly from the rest of the Danish realm, clearing the way for the exploitation of the Kvanefjeld deposit, which has been debated in Greenland ever since.

Environmental impact studies have been completed which show the project does not create significant issues for the local environment or residents of nearby communities. Extensive radiation studies show the increase in radiation exposure caused by the project is negligible. The level [sic] of dust generated by the project are very low and well below European standards.Footnote 10

Many residents of the immediately adjacent town of Narsaq fear the extensive tailings, both radioactive and toxic rare earth residue, that the mine will produce, as scholars have reported for almost a decade (see Hansen and Johnstone Reference Hansen and Johnstone2019; Nuttall Reference Nuttall2012; Reference Nuttall2013; Reference Nuttall2017). As early as 2013, Nuttall described the GME consultation process and corporate transparency as lacking substantive public participation, decision-making, and involvement in formal regulatory processes, which led to distrust of officially sanctioned assessments of social and environmental impact. In 2019, and as a result of ethnographic interviewing in and around the Narsaq and Qaqortoq communities, Hansen and Johnstone reiterated:

The decision-making processes [with regard to both Kvanefjeld and Tanbreez] were found lacking by our interviewees in many respects, in particular as regards the time taken and the exchange of information … the alarm caused by risk can create an atmosphere of powerlessness and paralysis among citizens. This points to the need for strategic planning and support to communities at the early exploration stages.

In other words, GME’s assertion of transparency with respect to the central concern about radioactive contamination caused by the mining and extraction of uranium ore was highly contested by the adjacent resident communities.

The fact that a uranium mine has even been considered feasible in a part of the Nordic Arctic, in countries where equality, livability, and the benign role of the state seem to be taken for granted, underscores the challenges inherent in what Hastrup and Lien have called the “resource frontiers” of this region: