1 Introduction

In various places around the world, severe forest fires have been observed to give rise to rotating columns of flame. In the most common instances, these are whipped up by local rotating winds, and so their formation is rather like that of a dust devil (or “willy-willy” in Australia). They are often referred to as fire whirls, fire tornadoes or even “firenadoes”. This terminology has been controversial (see McCarthy and Cormier [Reference McCarthy and Cormier17]), since a true tornado is a meteorological event in which a super-cell thunderstorm produces an intense rope-like vortex that descends to the ground, whereas fire whirls are generated at ground level. In any event, most fire whirls do not generate the enormous wind speeds created in tornadoes. It is possible to generate spectacular fire whirls safely in the laboratory, and an engaging example is given by Mészáros [Reference Mészáros18]. Experiments on a laboratory-scale fire vortex have also been carried out by Akhmetov et al. [Reference Akhmetov, Gavrilov and Nikulin3]. They compared measured speeds with some simple estimates and found reasonable agreement. An overview of fire whirls is given in the review article by Tohidi et al. [Reference Tohidi, Gollner and Xiao19].

Nevertheless, there are rare instances in which severe fires can generate rotating wind columns with speeds comparable to those in genuine tornadoes. Forthofer [Reference Forthofer9] gives a compelling and moving description of such an event; this was the Carr fire tornado that occurred in Northern California in July 2018. Forthofer estimated that wind speeds there were equivalent to those occurring in tornadoes of category 3 on the Fujita scale, and generated temperatures of about

![]() $1480^{\circ }$

C. Furthermore, by re-examining some historical fire-related tragedies, he concluded that the Hamburg firestorm in World War II and the 1923 firestorm that engulfed Tokyo after an earthquake may well have been examples of actual fire tornadoes. It is believed that a truly enormous fire can produce smoke and ash clouds several kilometres high; these also contain water vapour, perhaps from burnt vegetation, so that an ice-capped pyrocumulonimbus cloud forms at high altitude. The vorticity in this fire-generated thundercloud is then sufficient to create a tornado. The only fully documented case of such an event in the Southern Hemisphere appears to be the 2003 bushfire that devastated Australia’s capital city, Canberra. This is discussed in detail by Fromm et al. [Reference Fromm, Tupper, Rosenfeld, Servranckx and McRae10], who estimate that the pyrocumulonimbus cloud generated a tornado at category 2 on the Fujita scale. A photo of the event appears to show a funnel cloud, and there was a typical tornado damage track about 20 kilometres in length, accompanied by large black hailstones. The review article by Tomašević et al. [Reference Tomašević, Cheung, Vučetić and Fox-Hughes20] points out that several factors influence the likelihood of severe bushfire formation, but that these features that prevail in South-Eastern Australia (including Tasmania) also exist in the coastal regions of Croatia. A more recent article by Lareau et al. [Reference Lareau, Nauslar, Bentley, Roberts, Emmerson, Brong, Mehle and Wallman15] has analysed three tornadic firestorms in California, and found that, similar to the Canberra case, the data suggests category 2 tornadoes were formed, with pyrocumulonimbus clouds up to 16 kilometres high.

$1480^{\circ }$

C. Furthermore, by re-examining some historical fire-related tragedies, he concluded that the Hamburg firestorm in World War II and the 1923 firestorm that engulfed Tokyo after an earthquake may well have been examples of actual fire tornadoes. It is believed that a truly enormous fire can produce smoke and ash clouds several kilometres high; these also contain water vapour, perhaps from burnt vegetation, so that an ice-capped pyrocumulonimbus cloud forms at high altitude. The vorticity in this fire-generated thundercloud is then sufficient to create a tornado. The only fully documented case of such an event in the Southern Hemisphere appears to be the 2003 bushfire that devastated Australia’s capital city, Canberra. This is discussed in detail by Fromm et al. [Reference Fromm, Tupper, Rosenfeld, Servranckx and McRae10], who estimate that the pyrocumulonimbus cloud generated a tornado at category 2 on the Fujita scale. A photo of the event appears to show a funnel cloud, and there was a typical tornado damage track about 20 kilometres in length, accompanied by large black hailstones. The review article by Tomašević et al. [Reference Tomašević, Cheung, Vučetić and Fox-Hughes20] points out that several factors influence the likelihood of severe bushfire formation, but that these features that prevail in South-Eastern Australia (including Tasmania) also exist in the coastal regions of Croatia. A more recent article by Lareau et al. [Reference Lareau, Nauslar, Bentley, Roberts, Emmerson, Brong, Mehle and Wallman15] has analysed three tornadic firestorms in California, and found that, similar to the Canberra case, the data suggests category 2 tornadoes were formed, with pyrocumulonimbus clouds up to 16 kilometres high.

Mathematical modelling of fire whirls and fire tornadoes is clearly a difficult assignment, and much about these events is still unknown. The recent review article by Ahmad et al. [Reference Ahmad, Akafuah, Forthofer, Fuchihata, Hirasawa, Kuwana, Nakamura, Sekimoto, Saito and Williams2] gives an overview of modern efforts to understand fire whirls through the three-pronged approach of experimentation, theoretical analysis and computational mechanics. They suggest that there may not be a clear differentiation between large fire whirls and fire tornadoes, and that some of the earlier methods for distinguishing between the two may not be scientifically valid.

One of the earlier mathematical models for understanding the physical origins of fire whirls was published by Barcilon and Drazin [Reference Barcilon and Drazin5], who suggested that Rayleigh–Taylor and Kelvin–Helmholtz instabilities combine to produce highly unstable atmospheric flows. They did not explicitly consider the cylindrical shape of the fire whirl, but a slightly earlier article by Byram and Martin [Reference Byram and Martin6] carried out some experimental work, and used approximate momentum equations to estimate the shape of the rotating fire plume. They also suggested that accounting for condensing water vapour within the firenado could be important in modelling its energy and the height of the funnel cloud.

Computational fluid dynamics has been used by Cunningham and Reeder [Reference Cunningham and Reeder7] to model the 2003 fire tornado in Canberra. Their computer code assumed a three-dimensional compressible atmosphere, and evidently included a model of fluid turbulence. In addition, it accounted for atmospheric moisture and cloud formation. They report simulations that generated pyrocumulonimbus clouds and a tornadic vortex. Accounting for water vapour and condensation proved important in their model, which was able to generate conditions similar to those in the 2003 Canberra firenado. Grishin et al. [Reference Grishin, Matvienko and Rudi12] also carried out a computational solution for a fire whirl, and they give the details of their model. They solved the equations of viscous compressible fluid flow in axisymmetric geometry, with a k–

![]() $\epsilon $

model of turbulence. They did not account for the combustion chemistry or the presence of water vapour, and they concluded that the heat exchange between the fire and the air, and the presence of turbulence, were responsible for the formation of a heat tornado. In a later paper, Grishin and Matvienko [Reference Grishin and Matvienko11] used a finite-volume method to solve the axisymmetric, compressible, viscous fluid-flow equations, again with a k–

$\epsilon $

model of turbulence. They did not account for the combustion chemistry or the presence of water vapour, and they concluded that the heat exchange between the fire and the air, and the presence of turbulence, were responsible for the formation of a heat tornado. In a later paper, Grishin and Matvienko [Reference Grishin and Matvienko11] used a finite-volume method to solve the axisymmetric, compressible, viscous fluid-flow equations, again with a k–

![]() $\epsilon $

turbulence model, but now also including combustion chemistry with the species oxygen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and water vapour taken into account in their model. They found that the rotational swirl speed had a strong effect on the height to which the thermal plume rises in the atmosphere.

$\epsilon $

turbulence model, but now also including combustion chemistry with the species oxygen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and water vapour taken into account in their model. They found that the rotational swirl speed had a strong effect on the height to which the thermal plume rises in the atmosphere.

In the present paper, we investigate a model of the fire whirl that has been made to be as simple as possible. Axisymmetric equations for the plume shape are solved, as in the models of Grishin and colleagues [Reference Grishin and Matvienko11, Reference Grishin, Matvienko and Rudi12]. A simple Boussinesq approach to the fluid momentum equations is adopted, so that any possibility of an explicit interface at the edge of the fire plume is avoided. This allows us to obtain a rather complete linearized solution for the problem, apparently for the first time, and it provides valuable information about the flow within the firenado vortex. This is given in full in Section 3. We solve the nonlinear equations using a spectral method, which takes full advantage of the axisymmetric geometry through the use of the first-kind Bessel functions

![]() $J_0$

and

$J_0$

and

![]() $J_1$

as basis functions (see Abramowitz and Stegun [Reference Abramowitz and Stegun1, page 358]). As a result, numerical accuracy is greatly enhanced. The numerical scheme is outlined in Section 4 and some results are presented in Section 5. A surprising result is that large, energetic fires can be responsible for flow reversion within the rotating vortex, in which the tip points downward. This is discussed more fully in Section 6, where it is found that nonlinear convection effects can be responsible for a type of vortex breakdown at large fire amplitude

$J_1$

as basis functions (see Abramowitz and Stegun [Reference Abramowitz and Stegun1, page 358]). As a result, numerical accuracy is greatly enhanced. The numerical scheme is outlined in Section 4 and some results are presented in Section 5. A surprising result is that large, energetic fires can be responsible for flow reversion within the rotating vortex, in which the tip points downward. This is discussed more fully in Section 6, where it is found that nonlinear convection effects can be responsible for a type of vortex breakdown at large fire amplitude

![]() $\epsilon _F$

, through the formation of a stagnation streamsurface within the vortex, which separates a lower rotating cell from an upper counterrotating region. As time progresses, this upper region eventually dominates. Some further comments are given in the concluding Section 7.

$\epsilon _F$

, through the formation of a stagnation streamsurface within the vortex, which separates a lower rotating cell from an upper counterrotating region. As time progresses, this upper region eventually dominates. Some further comments are given in the concluding Section 7.

2 The mathematical model

This simple idealization of a rotating firestorm event assumes that there is some (circular) patch of burning (homogeneous) grassland, of radius a. The ground is taken to be the plane

![]() $z=0$

in a Cartesian coordinate system in which the z-axis points vertically, and the origin is located at the centre of the circular combustion region. The air is modelled here as a weakly compressible fluid of density

$z=0$

in a Cartesian coordinate system in which the z-axis points vertically, and the origin is located at the centre of the circular combustion region. The air is modelled here as a weakly compressible fluid of density

![]() $\rho $

, that is subject to the downward acceleration

$\rho $

, that is subject to the downward acceleration

![]() $-g \mathbf {e_z}$

of gravity.

$-g \mathbf {e_z}$

of gravity.

In reality, the burning process occurring within the disk

![]() $r<a$

of bushland, near ground level, would involve a sequence of combustion reactions, as well as the production of flammable gases, perhaps similar to the processes described by Forbes [Reference Forbes8] in his model of an Australian bushfire. Here, however, all that is ignored, and it is assumed instead that the burning reactions effectively result in an elevated ground-level temperature

$r<a$

of bushland, near ground level, would involve a sequence of combustion reactions, as well as the production of flammable gases, perhaps similar to the processes described by Forbes [Reference Forbes8] in his model of an Australian bushfire. Here, however, all that is ignored, and it is assumed instead that the burning reactions effectively result in an elevated ground-level temperature

in which the ambient temperature is

![]() $T_a$

and the temperature at the centre of the fire is

$T_a$

and the temperature at the centre of the fire is

![]() $T_F$

. The dimensionless shape function

$T_F$

. The dimensionless shape function

![]() $f(r)$

gives the ground-level temperature profile; at the centre

$f(r)$

gives the ground-level temperature profile; at the centre

![]() $r=0$

it follows that

$r=0$

it follows that

![]() $f(0)=1$

, and far away the temperature falls back to ambient, so that

$f(0)=1$

, and far away the temperature falls back to ambient, so that

![]() $f ( \infty ) = 0$

.

$f ( \infty ) = 0$

.

To simplify the model, we now make use of the Boussinesq approximation (see Vallis [Reference Vallis21, Section 2.4]). This essentially postulates a linear variation of the air temperature T with its density

![]() $\rho $

, which can be understood to be the first-order term in a Taylor series of some more complicated function

$\rho $

, which can be understood to be the first-order term in a Taylor series of some more complicated function

![]() $T(\rho )$

about the ambient density

$T(\rho )$

about the ambient density

![]() $\rho _a$

. Boussinesq theory makes the approximation

$\rho _a$

. Boussinesq theory makes the approximation

in which the correction function

![]() $\overline {\rho }$

is small relative to

$\overline {\rho }$

is small relative to

![]() $\rho _a$

. This is related to the temperature by the linearized condition

$\rho _a$

. This is related to the temperature by the linearized condition

A negative sign is present to emphasize the fact that air density decreases with increasing temperature, and the positive constant

![]() $A_T$

is the coefficient of thermal expansion of the air.

$A_T$

is the coefficient of thermal expansion of the air.

Cylindrical polar coordinates

![]() $( r, \theta , z )$

will be used in this analysis, since a cylindrical “firenado” will be assumed here, as a further simplification. These are related to the usual Cartesian coordinates

$( r, \theta , z )$

will be used in this analysis, since a cylindrical “firenado” will be assumed here, as a further simplification. These are related to the usual Cartesian coordinates

![]() $( x,y,z )$

by the familiar formulae

$( x,y,z )$

by the familiar formulae

![]() $x = r \cos \theta $

and

$x = r \cos \theta $

and

![]() $y = r\sin \theta $

. In cylindrical coordinates, the velocity vector

$y = r\sin \theta $

. In cylindrical coordinates, the velocity vector

![]() $\mathbf {q}$

of the air is represented in component form as

$\mathbf {q}$

of the air is represented in component form as

In Boussinesq theory, the exact continuity equation expressing the conservation of mass in a compressible gas is further “split” into an incompressible equation

and a remnant transport equation for the density correction term

![]() $\overline {\rho }$

that is convected about in the fluid. Equivalently, in view of the relation (2.3), the temperature obeys an energy-conservation law of the form

$\overline {\rho }$

that is convected about in the fluid. Equivalently, in view of the relation (2.3), the temperature obeys an energy-conservation law of the form

Here, the constant B is a diffusion coefficient for temperature, and h represents the coefficient of Newtonian cooling of the air to the ambient temperature

![]() $T_a$

. Newton’s law of cooling is an approximation that assumes convective heat transfer, in which the coefficient h is constant. Further details are given in a recent e-book by Lienhard and Lienhard [Reference Lienhard and Lienhard16, page 19]. (Here, we do not consider radiation effects, which are modelled using Stefan’s law [Reference Lienhard and Lienhard16, page 71].)

$T_a$

. Newton’s law of cooling is an approximation that assumes convective heat transfer, in which the coefficient h is constant. Further details are given in a recent e-book by Lienhard and Lienhard [Reference Lienhard and Lienhard16, page 19]. (Here, we do not consider radiation effects, which are modelled using Stefan’s law [Reference Lienhard and Lienhard16, page 71].)

Conservation of momentum within the moving air is modelled using the familiar Navier–Stokes equation; however, in the Boussinesq approximation, the exact density term (2.2) is retained only where it multiplies the acceleration g of gravity in the buoyancy term. This results in the Navier–Stokes–Boussinesq equation

in which the function p denotes the pressure in the air. The kinematic viscosity is

![]() $\mu $

, and in the vortex, where the flow is possibly turbulent,

$\mu $

, and in the vortex, where the flow is possibly turbulent,

![]() $\mu $

would represent an effective turbulent viscosity. Boundary layers are ignored here for simplicity, so that the air effectively slips over the ground plane

$\mu $

would represent an effective turbulent viscosity. Boundary layers are ignored here for simplicity, so that the air effectively slips over the ground plane

![]() $z=0$

.

$z=0$

.

Nondimensional coordinates are now introduced, since this reduces the number of free constants in the model, and can assist in elucidating the mathematical structure of closed-form solutions, such as that discussed in Section 3. Lengths are all scaled relative to the notional ground radius a of the circular fire column. Time and speeds are scaled using the quantities

![]() $\sqrt {a/g}$

and

$\sqrt {a/g}$

and

![]() $\sqrt {ag}$

, in which g is the downward acceleration of gravity. The (ambient) temperature

$\sqrt {ag}$

, in which g is the downward acceleration of gravity. The (ambient) temperature

![]() $T_a$

and density

$T_a$

and density

![]() $\rho _a$

far away are used as reference values for temperature and density throughout the atmosphere, so that

$\rho _a$

far away are used as reference values for temperature and density throughout the atmosphere, so that

![]() $a g \rho _a$

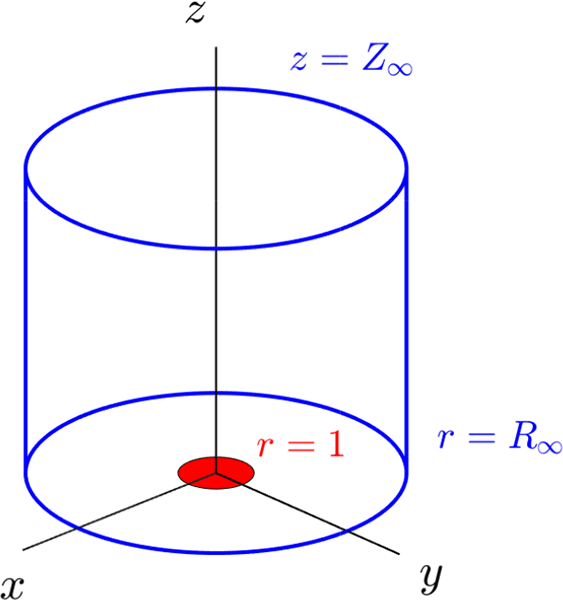

is the natural reference scale for pressure. A sketch of the dimensionless coordinate system is given in Figure 1. In this dimensionless formulation, solutions are thus found to depend upon five nondimensional parameters. These are

$a g \rho _a$

is the natural reference scale for pressure. A sketch of the dimensionless coordinate system is given in Figure 1. In this dimensionless formulation, solutions are thus found to depend upon five nondimensional parameters. These are

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} \alpha &= A_T T_a ,\quad \beta = \frac{B}{\sqrt{a^3 g}} ,\quad \frac{1}{R_e} = \frac{\mu}{\rho_a \sqrt{a^3 g}},\\ \chi_N &= h \sqrt{\frac{a}{g}}, \quad \epsilon_F = \frac{T_F - T_a}{T_a}. \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} \alpha &= A_T T_a ,\quad \beta = \frac{B}{\sqrt{a^3 g}} ,\quad \frac{1}{R_e} = \frac{\mu}{\rho_a \sqrt{a^3 g}},\\ \chi_N &= h \sqrt{\frac{a}{g}}, \quad \epsilon_F = \frac{T_F - T_a}{T_a}. \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

The first parameter

![]() $\alpha $

is the dimensionless thermal-expansion coefficient in the atmosphere, and

$\alpha $

is the dimensionless thermal-expansion coefficient in the atmosphere, and

![]() $\beta $

is the coefficient of thermal diffusion. The Reynolds number

$\beta $

is the coefficient of thermal diffusion. The Reynolds number

![]() $R_e$

is essentially a measure of the inverse viscosity, so that, if

$R_e$

is essentially a measure of the inverse viscosity, so that, if

![]() $R_e$

is small then the fluid is very viscous, whereas the effects of viscosity become negligible as

$R_e$

is small then the fluid is very viscous, whereas the effects of viscosity become negligible as

![]() $R_e \rightarrow \infty $

. The parameter

$R_e \rightarrow \infty $

. The parameter

![]() $\chi _N$

represents the rate of Newtonian cooling of the atmosphere, and

$\chi _N$

represents the rate of Newtonian cooling of the atmosphere, and

![]() $\epsilon _F$

gives the temperature rise within the “firenado” relative to the ambient temperature. There may also be extra parameters associated with the function

$\epsilon _F$

gives the temperature rise within the “firenado” relative to the ambient temperature. There may also be extra parameters associated with the function

![]() $f(r)$

in the boundary condition (2.1) for the temperature at ground level.

$f(r)$

in the boundary condition (2.1) for the temperature at ground level.

Figure 1 Dimensionless coordinate system used for the firenado model. The central disk of radius

![]() $r=1$

represents the location of the swirling fire. In the linearized solution of Section 3 the fluid domain is the entire half-space

$r=1$

represents the location of the swirling fire. In the linearized solution of Section 3 the fluid domain is the entire half-space

![]() $z>0$

, but in the nonlinear spectral solution in Section 4 the computational domain is restricted to

$z>0$

, but in the nonlinear spectral solution in Section 4 the computational domain is restricted to

![]() $0 < r < R_{\infty }$

,

$0 < r < R_{\infty }$

,

![]() $0 < z < Z_{\infty }$

as shown.

$0 < z < Z_{\infty }$

as shown.

In cylindrical polar coordinates and in these dimensionless variables, the incompressibility condition (2.5) takes the form

The relationship (2.3) between the air temperature and the density becomes

The three components of the momentum equation (2.7) in the r- ,

![]() $\theta $

- and z-directions, respectively, are

$\theta $

- and z-directions, respectively, are

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\partial u}{\partial t} + u \frac{\partial u}{\partial r} + w \frac{\partial u}{\partial z} - \frac{v^2}{r} + \frac{\partial p}{\partial r} & = \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ \nabla^2 u - \frac{u}{r^2} \bigg], \nonumber \\ \frac{\partial v}{\partial t} + u \frac{\partial v}{\partial r} + w \frac{\partial v}{\partial z} + \frac{u v}{r} & = \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ \nabla^2 v - \frac{v}{r^2} \bigg], \\ \frac{\partial w}{\partial t} + u \frac{\partial w}{\partial r} + w \frac{\partial w}{\partial z} + \frac{\partial p}{\partial z} & = - ( 1 + \overline{\rho} ) + \frac{1}{R_e} \nabla^2 w. \nonumber \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\partial u}{\partial t} + u \frac{\partial u}{\partial r} + w \frac{\partial u}{\partial z} - \frac{v^2}{r} + \frac{\partial p}{\partial r} & = \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ \nabla^2 u - \frac{u}{r^2} \bigg], \nonumber \\ \frac{\partial v}{\partial t} + u \frac{\partial v}{\partial r} + w \frac{\partial v}{\partial z} + \frac{u v}{r} & = \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ \nabla^2 v - \frac{v}{r^2} \bigg], \\ \frac{\partial w}{\partial t} + u \frac{\partial w}{\partial r} + w \frac{\partial w}{\partial z} + \frac{\partial p}{\partial z} & = - ( 1 + \overline{\rho} ) + \frac{1}{R_e} \nabla^2 w. \nonumber \end{align} $$

Finally, the convective heat equation (2.6) takes the form

In these relations (2.11) and (2.12), the operator

$$ \begin{align} \nabla^2 T = \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial}{\partial r} \bigg( r \frac{\partial T}{\partial r} \bigg) + \frac{\partial^2 T}{\partial z^2}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \nabla^2 T = \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial}{\partial r} \bigg( r \frac{\partial T}{\partial r} \bigg) + \frac{\partial^2 T}{\partial z^2}, \end{align} $$

acting here on a function

![]() $T (r,z,t)$

, is the Laplacian derivative in cylindrical polar coordinates, in the axisymmetric case for which

$T (r,z,t)$

, is the Laplacian derivative in cylindrical polar coordinates, in the axisymmetric case for which

![]() $\partial / \partial \theta \equiv 0$

. As discussed above, the effect of the burning vegetation is modelled here very simply by imposing an effective temperature (2.1) at ground level. In dimensionless coordinates, we generalize the boundary condition (2.1) slightly, by multiplying the perturbation temperature by a smoothly increasing function of time. We choose a relation of the form

$\partial / \partial \theta \equiv 0$

. As discussed above, the effect of the burning vegetation is modelled here very simply by imposing an effective temperature (2.1) at ground level. In dimensionless coordinates, we generalize the boundary condition (2.1) slightly, by multiplying the perturbation temperature by a smoothly increasing function of time. We choose a relation of the form

since this allows a smooth increase in temperature T from the ambient value

![]() $T=1$

at

$T=1$

at

![]() $t=0$

to the final value

$t=0$

to the final value

![]() $T = 1 + \epsilon _F f(r)$

, without the discontinuity indicated in (2.1). This boundary condition (2.14) does, however, involve an additional dimensionless time constant

$T = 1 + \epsilon _F f(r)$

, without the discontinuity indicated in (2.1). This boundary condition (2.14) does, however, involve an additional dimensionless time constant

![]() $\tau _F$

. Notice that a swirling component

$\tau _F$

. Notice that a swirling component

![]() $v (r,z,t)$

of the velocity vector

$v (r,z,t)$

of the velocity vector

![]() $\mathbf {q}$

is still retained in the momentum equations (2.11), even although dependence on the azimuthal coordinate

$\mathbf {q}$

is still retained in the momentum equations (2.11), even although dependence on the azimuthal coordinate

![]() $\theta $

is ignored.

$\theta $

is ignored.

3 A linearized solution

In this section, an approximate theory is derived, in which the temperature inside the “firenado” is assumed not to be very much greater than the ambient temperature. This means that the parameter

![]() $\epsilon _F$

in (2.8) is small. Consequently, we express the solution variables in perturbation expansions about the ambient conditions, and postulate

$\epsilon _F$

in (2.8) is small. Consequently, we express the solution variables in perturbation expansions about the ambient conditions, and postulate

$$ \begin{align} T(r,z,t) & = 1 + \epsilon_F T^L (r,z,t) + \mathcal{O} ( \epsilon_F^2 ), \nonumber \\ u(r,z,t) & = \quad\quad \epsilon_F U^L (r,z,t) + \mathcal{O} ( \epsilon_F^2 ), \nonumber \\ v(r,z,t) & = \quad\quad \epsilon_F V^L (r,z,t) + \mathcal{O} ( \epsilon_F^2 ), \\ w(r,z,t) & = \quad\quad \epsilon_F W^L (r,z,t) + \mathcal{O} ( \epsilon_F^2 ), \nonumber \\ \overline{\rho}(r,z,t) & = \quad\quad \epsilon_F \rho^L (r,z,t) + \mathcal{O} ( \epsilon_F^2 ), \nonumber \\ p(r,z,t) & = - z + \epsilon_F p^L (r,z,t) + \mathcal{O} (\epsilon_F^2). \nonumber \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} T(r,z,t) & = 1 + \epsilon_F T^L (r,z,t) + \mathcal{O} ( \epsilon_F^2 ), \nonumber \\ u(r,z,t) & = \quad\quad \epsilon_F U^L (r,z,t) + \mathcal{O} ( \epsilon_F^2 ), \nonumber \\ v(r,z,t) & = \quad\quad \epsilon_F V^L (r,z,t) + \mathcal{O} ( \epsilon_F^2 ), \\ w(r,z,t) & = \quad\quad \epsilon_F W^L (r,z,t) + \mathcal{O} ( \epsilon_F^2 ), \nonumber \\ \overline{\rho}(r,z,t) & = \quad\quad \epsilon_F \rho^L (r,z,t) + \mathcal{O} ( \epsilon_F^2 ), \nonumber \\ p(r,z,t) & = - z + \epsilon_F p^L (r,z,t) + \mathcal{O} (\epsilon_F^2). \nonumber \end{align} $$

These forms of the solution variables are substituted into the governing equations (2.9)–(2.12), and terms are retained to the first order in the small parameter

![]() $\epsilon _F$

. This gives rise to a linear set of partial differential equations for the approximate solution variables

$\epsilon _F$

. This gives rise to a linear set of partial differential equations for the approximate solution variables

![]() $T^L$

and so on.

$T^L$

and so on.

The linearized approximation to the continuity equation (2.9) is readily seen to be

$$ \begin{align} \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial}{\partial r} ( r U^L ) + \frac{\partial W^L}{\partial z} = 0, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial}{\partial r} ( r U^L ) + \frac{\partial W^L}{\partial z} = 0, \end{align} $$

and the Boussinesq equation of state (2.10) becomes simply

in the linear approximation. At the first order in

![]() $\epsilon _F$

the three components of the momentum equation (2.11) reduce to

$\epsilon _F$

the three components of the momentum equation (2.11) reduce to

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\partial U^L}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial p^L}{\partial r} & = \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ \nabla^2 U^L - \frac{U^L}{r^2} \bigg], \nonumber \\ \frac{\partial V^L}{\partial t} & = \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ \nabla^2 V^L - \frac{V^L}{r^2} \bigg], \\ \frac{\partial W^L}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial p^L}{\partial z} & = - \rho^L + \frac{1}{R_e} \nabla^2 W^L, \nonumber \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\partial U^L}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial p^L}{\partial r} & = \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ \nabla^2 U^L - \frac{U^L}{r^2} \bigg], \nonumber \\ \frac{\partial V^L}{\partial t} & = \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ \nabla^2 V^L - \frac{V^L}{r^2} \bigg], \\ \frac{\partial W^L}{\partial t} + \frac{\partial p^L}{\partial z} & = - \rho^L + \frac{1}{R_e} \nabla^2 W^L, \nonumber \end{align} $$

in which

![]() $\nabla ^2$

is the scalar operator given in (2.13). The linearized form of the energy equation (2.12) is

$\nabla ^2$

is the scalar operator given in (2.13). The linearized form of the energy equation (2.12) is

In this linearized approximation, the heat law (3.5) decouples from the rest of the equations in the system, and so can be solved separately, subject to the boundary condition

These equations can be solved using Hankel and Laplace transforms [Reference Abramowitz and Stegun1] over the semi-infinite domain

![]() $0 < r < \infty $

,

$0 < r < \infty $

,

![]() $0 < z < \infty $

, but the result is sufficiently complicated as to be somewhat unenlightening. Consequently, we choose instead to solve over the approximate computational region

$0 < z < \infty $

, but the result is sufficiently complicated as to be somewhat unenlightening. Consequently, we choose instead to solve over the approximate computational region

![]() $0 < r < R_{\infty }$

,

$0 < r < R_{\infty }$

,

![]() $0 < z < Z_{\infty }$

illustrated in Figure 1. The appropriate additional boundary conditions in this case are

$0 < z < Z_{\infty }$

illustrated in Figure 1. The appropriate additional boundary conditions in this case are

![]() $T^L = 0$

on

$T^L = 0$

on

![]() $r = R_{\infty }$

and

$r = R_{\infty }$

and

![]() $T^L = 0$

on

$T^L = 0$

on

![]() $z = Z_{\infty }$

.

$z = Z_{\infty }$

.

After a little trial and error, it becomes evident that a pragmatic form for the linearized temperature function

![]() $T^L$

is

$T^L$

is

$$ \begin{align} T^L (r,z,t) & = \cos \bigg( \frac{\pi z}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} A_{m,0}(t) J_0 ( p_m r )\nonumber \\ & \quad + \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} A_{m,n}(t) J_0 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} T^L (r,z,t) & = \cos \bigg( \frac{\pi z}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} A_{m,0}(t) J_0 ( p_m r )\nonumber \\ & \quad + \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} A_{m,n}(t) J_0 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg), \end{align} $$

in which the eigenvalues

![]() $p_m$

are given by

$p_m$

are given by

The function

![]() $J_0 (z)$

is the zeroth-order Bessel function of the first kind, and

$J_0 (z)$

is the zeroth-order Bessel function of the first kind, and

![]() $j_{0,m}$

,

$j_{0,m}$

,

![]() $m = 1, 2, 3, \ldots ,$

are its zeros (see Abramowitz and Stegun [Reference Abramowitz and Stegun1, Ch. 9]), so that

$m = 1, 2, 3, \ldots ,$

are its zeros (see Abramowitz and Stegun [Reference Abramowitz and Stegun1, Ch. 9]), so that

![]() ${J_0 ( j_{0,m} ) = 0}$

. This satisfies the condition

${J_0 ( j_{0,m} ) = 0}$

. This satisfies the condition

![]() $T^L = 0$

on the artificial computational boundaries shown in Figure 1. The bottom boundary condition (3.6) on

$T^L = 0$

on the artificial computational boundaries shown in Figure 1. The bottom boundary condition (3.6) on

![]() $z=0$

, combined with the form (3.7) of the solution, gives rise to the requirement

$z=0$

, combined with the form (3.7) of the solution, gives rise to the requirement

$$ \begin{align*} f(r) \bigg[ 1 - \exp \bigg( - \frac{t}{\tau_F} \bigg) \bigg] = \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} A_{m,0}(t) J_0 ( p_m r ). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} f(r) \bigg[ 1 - \exp \bigg( - \frac{t}{\tau_F} \bigg) \bigg] = \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} A_{m,0}(t) J_0 ( p_m r ). \end{align*} $$

This condition is multiplied by basis functions

![]() $r J_0 ( p_k r )$

,

$r J_0 ( p_k r )$

,

![]() $k = 1,2, 3, \ldots ,$

and integrated over the domain

$k = 1,2, 3, \ldots ,$

and integrated over the domain

![]() $0< r < R_{\infty }$

. The orthogonality of the Bessel functions then gives the coefficients for

$0< r < R_{\infty }$

. The orthogonality of the Bessel functions then gives the coefficients for

![]() $n=0$

in the form

$n=0$

in the form

$$ \begin{align} A_{k,0}(t) = \frac{1}{\Lambda_k} \bigg[ 1 - \exp \bigg( - \frac{t}{\tau_F} \bigg) \bigg] \int_0^{R_{\infty}} r f(r) J_0 ( p_k r ) \, \textit{d} r, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} A_{k,0}(t) = \frac{1}{\Lambda_k} \bigg[ 1 - \exp \bigg( - \frac{t}{\tau_F} \bigg) \bigg] \int_0^{R_{\infty}} r f(r) J_0 ( p_k r ) \, \textit{d} r, \end{align} $$

in which we have defined constants

Here,

![]() $J_1$

is the first-kind Bessel function of order

$J_1$

is the first-kind Bessel function of order

![]() $1$

.

$1$

.

The form (3.7) is next substituted into the linearized energy equation (3.5), to determine the remaining coefficient functions

![]() $A_{m,n}(t)$

. This gives

$A_{m,n}(t)$

. This gives

$$ \begin{align*} \cos &\bigg( \frac{\pi z}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \frac{\textit{d} A_{m,0}(t)}{\textit{d} t} J_0 ( p_m r ) + \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{\textit{d} A_{m,n}(t)}{\textit{d} t} J_0 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \nonumber \\ & = - \cos \bigg( \frac{\pi z}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} A_{m,0}(t) \Gamma_m J_0 ( p_m r ) - \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} A_{m,n}(t) \Delta_{m,n} J_0 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \nonumber \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \cos &\bigg( \frac{\pi z}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \frac{\textit{d} A_{m,0}(t)}{\textit{d} t} J_0 ( p_m r ) + \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{\textit{d} A_{m,n}(t)}{\textit{d} t} J_0 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \nonumber \\ & = - \cos \bigg( \frac{\pi z}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} A_{m,0}(t) \Gamma_m J_0 ( p_m r ) - \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} A_{m,n}(t) \Delta_{m,n} J_0 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \nonumber \end{align*} $$

This equation is multiplied by

![]() $r J_0 ( p_k r ) \sin ( \ell \pi z / Z_{\infty } )$

,

$r J_0 ( p_k r ) \sin ( \ell \pi z / Z_{\infty } )$

,

![]() $k = 1,2, \ldots ,$

and integrated over the computational domain

$k = 1,2, \ldots ,$

and integrated over the computational domain

![]() $0 < r < R_{\infty }$

,

$0 < r < R_{\infty }$

,

![]() $0 < z < Z_{\infty }$

. After some algebra, this results in the infinite system of ordinary differential equations

$0 < z < Z_{\infty }$

. After some algebra, this results in the infinite system of ordinary differential equations

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\textit{d} A_{k,\ell}(t)}{\textit{d} t} + \Delta_{k,\ell} A_{k,\ell}(t) & = - \frac{8\ell}{\pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )} \bigg[\frac{\textit{d} A_{k,0}(t)}{\textit{d} t} + \Gamma_{k} A_{k,0}(t) \bigg],\nonumber \\ & \quad k = 1, 2, \ldots, \quad \ell = 1, 2, \ldots. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\textit{d} A_{k,\ell}(t)}{\textit{d} t} + \Delta_{k,\ell} A_{k,\ell}(t) & = - \frac{8\ell}{\pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )} \bigg[\frac{\textit{d} A_{k,0}(t)}{\textit{d} t} + \Gamma_{k} A_{k,0}(t) \bigg],\nonumber \\ & \quad k = 1, 2, \ldots, \quad \ell = 1, 2, \ldots. \end{align} $$

In obtaining these equations, the following integral was used:

$$ \begin{align} \int_0^{Z_{\infty}} \cos \bigg( \frac{\pi z}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \sin \bigg( \frac{\ell \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \, \textit{d} z = \frac{4 \ell Z_{\infty}}{\pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \int_0^{Z_{\infty}} \cos \bigg( \frac{\pi z}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \sin \bigg( \frac{\ell \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \, \textit{d} z = \frac{4 \ell Z_{\infty}}{\pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )}. \end{align} $$

In these expressions, we have defined additional constants

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} \Gamma_{k} & = \beta \bigg[ p_k^2 + \bigg(\frac{\pi}{2 Z_{\infty}}\bigg)^2 \bigg] + \chi_N , \\ \Delta_{k,\ell} & = \beta \bigg[ p_k^2 + \bigg(\frac{\ell \pi}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg)^2 \bigg] + \chi_N. \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} \Gamma_{k} & = \beta \bigg[ p_k^2 + \bigg(\frac{\pi}{2 Z_{\infty}}\bigg)^2 \bigg] + \chi_N , \\ \Delta_{k,\ell} & = \beta \bigg[ p_k^2 + \bigg(\frac{\ell \pi}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg)^2 \bigg] + \chi_N. \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

The zeroth-order coefficients

![]() $A_{k,0}(t)$

are known exactly from (3.9), so that the terms on the right of (3.11) can be evaluated. The initial condition

$A_{k,0}(t)$

are known exactly from (3.9), so that the terms on the right of (3.11) can be evaluated. The initial condition

![]() $T^L = 0$

when

$T^L = 0$

when

![]() $t=0$

then means that each differential equation in (3.11) is solved subject to

$t=0$

then means that each differential equation in (3.11) is solved subject to

![]() $A_{k,\ell }(0) = 0$

. The result is

$A_{k,\ell }(0) = 0$

. The result is

$$ \begin{align} A_{k,\ell}(t) & = \mathcal{C}_{k,\ell}^A \bigg\{\frac{\Gamma_k}{\Delta_{k,l}} [ \exp ( - \Delta_{k,\ell} t ) - 1 ] \nonumber \\ & \quad + \frac{ ( 1 - \tau_F \Gamma_k )}{( \tau_F \Delta_{k,\ell} - 1 )} [ \exp ( - \Delta_{k,\ell} t ) - \exp ( - t / \tau_F ) ] \bigg\}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} A_{k,\ell}(t) & = \mathcal{C}_{k,\ell}^A \bigg\{\frac{\Gamma_k}{\Delta_{k,l}} [ \exp ( - \Delta_{k,\ell} t ) - 1 ] \nonumber \\ & \quad + \frac{ ( 1 - \tau_F \Gamma_k )}{( \tau_F \Delta_{k,\ell} - 1 )} [ \exp ( - \Delta_{k,\ell} t ) - \exp ( - t / \tau_F ) ] \bigg\}, \end{align} $$

where we have defined

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{C}_{k,\ell}^A = \frac{8 \ell}{\Lambda_k \pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )} \int_0^{R_{\infty}} r f(r) J_0 ( p_k r ) \, \textit{d} r, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{C}_{k,\ell}^A = \frac{8 \ell}{\Lambda_k \pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )} \int_0^{R_{\infty}} r f(r) J_0 ( p_k r ) \, \textit{d} r, \end{align} $$

and the constants defined in (3.10) and (3.13) have also been utilized. Thus the complete solution for the temperature perturbation function

![]() $T^L$

in the linearized approximation is given by (3.7) with (3.9) and (3.14). The density perturbation function

$T^L$

in the linearized approximation is given by (3.7) with (3.9) and (3.14). The density perturbation function

![]() $\rho ^L$

is then found at once from (3.3).

$\rho ^L$

is then found at once from (3.3).

The linearized swirl component

![]() $V_L$

of velocity satisfies the azimuthal component of the momentum equation in (3.4). This must be solved subject to specifying the azimuthal velocity at ground level, and following the formulation developed in (3.6), we give the function

$V_L$

of velocity satisfies the azimuthal component of the momentum equation in (3.4). This must be solved subject to specifying the azimuthal velocity at ground level, and following the formulation developed in (3.6), we give the function

It is appropriate again to allow the swirl velocity component to have a similar type of structure to that used for the temperature perturbation function

![]() $T^L$

in (3.7), and so here we choose

$T^L$

in (3.7), and so here we choose

$$ \begin{align} V^L (r,z,t) & = \cos \bigg( \frac{\pi z}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} B_{m,0}(t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \nonumber \\ & \quad + \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} B_{m,n}(t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} V^L (r,z,t) & = \cos \bigg( \frac{\pi z}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} B_{m,0}(t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \nonumber \\ & \quad + \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} B_{m,n}(t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg), \end{align} $$

with constants

![]() $p_m$

given in (3.8), as before. Notice, however, that the first-order Bessel function

$p_m$

given in (3.8), as before. Notice, however, that the first-order Bessel function

![]() $J_1$

is used in (3.17) since we require

$J_1$

is used in (3.17) since we require

![]() $V^L = 0$

on the z-axis

$V^L = 0$

on the z-axis

![]() $r=0$

.

$r=0$

.

Applying the ground-level boundary condition (3.16) leads at once to the equation

$$ \begin{align*} h(r) \bigg[ 1 - \exp \bigg( - \frac{t}{\tau_F} \bigg) \bigg] = \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} B_{m,0}(t) J_1 ( p_m r ). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} h(r) \bigg[ 1 - \exp \bigg( - \frac{t}{\tau_F} \bigg) \bigg] = \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} B_{m,0}(t) J_1 ( p_m r ). \end{align*} $$

This is then multiplied by basis functions

![]() $r J_1 ( p_k r )$

,

$r J_1 ( p_k r )$

,

![]() $k = 1,2, 3, \ldots ,$

and integrated over the domain

$k = 1,2, 3, \ldots ,$

and integrated over the domain

![]() $0< r < R_{\infty }$

, following the same development as in (3.9) above. The first-order Bessel functions

$0< r < R_{\infty }$

, following the same development as in (3.9) above. The first-order Bessel functions

![]() $J_1$

satisfy the same orthogonality conditions, and so the coefficients for the rotational speed at zeroth order

$J_1$

satisfy the same orthogonality conditions, and so the coefficients for the rotational speed at zeroth order

![]() $n=0$

are similarly found to be

$n=0$

are similarly found to be

$$ \begin{align} B_{k,0}(t) = \frac{1}{\Lambda_k} \bigg[ 1 - \exp \bigg( - \frac{t}{\tau_F} \bigg) \bigg] \int_0^{R_{\infty}} r h(r) J_1 ( p_k r ) \, \textit{d} r. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} B_{k,0}(t) = \frac{1}{\Lambda_k} \bigg[ 1 - \exp \bigg( - \frac{t}{\tau_F} \bigg) \bigg] \int_0^{R_{\infty}} r h(r) J_1 ( p_k r ) \, \textit{d} r. \end{align} $$

The constants

![]() $\Lambda _k$

are those defined in (3.10).

$\Lambda _k$

are those defined in (3.10).

The remaining coefficients in the form (3.17) are found by substituting this expression into the linearized azimuthal component of the momentum equation (3.4). This is then multiplied by

![]() $r J_1 ( p_k r ) \sin ( \ell \pi z / Z_{\infty } )$

,

$r J_1 ( p_k r ) \sin ( \ell \pi z / Z_{\infty } )$

,

![]() $k = 1,2, \ldots ,$

and integrated over the computational domain

$k = 1,2, \ldots ,$

and integrated over the computational domain

![]() $0 < r < R_{\infty }$

,

$0 < r < R_{\infty }$

,

![]() $0 < z < Z_{\infty }$

. The calculations are similar to those leading to the differential equations (3.11), and a significant amount of algebra gives rise to the system

$0 < z < Z_{\infty }$

. The calculations are similar to those leading to the differential equations (3.11), and a significant amount of algebra gives rise to the system

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\textit{d} B_{k,\ell}(t)}{\textit{d} t} + \delta_{k,\ell} B_{k,\ell}(t) & = - \frac{8\ell}{\pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )} \bigg[\frac{\textit{d} B_{k,0}(t)}{\textit{d} t} + \gamma_{k} B_{k,0}(t) \bigg], \nonumber \\ & \quad k = 1, 2, \ldots, \quad \ell = 1, 2, \ldots, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\textit{d} B_{k,\ell}(t)}{\textit{d} t} + \delta_{k,\ell} B_{k,\ell}(t) & = - \frac{8\ell}{\pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )} \bigg[\frac{\textit{d} B_{k,0}(t)}{\textit{d} t} + \gamma_{k} B_{k,0}(t) \bigg], \nonumber \\ & \quad k = 1, 2, \ldots, \quad \ell = 1, 2, \ldots, \end{align} $$

in which we have defined further auxiliary constants

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned}\gamma_{k} & = \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ p_k^2 + \bigg( \frac{\pi}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg)^2 \bigg], \\ \delta_{k,\ell} & = \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ p_k^2 + \bigg( \frac{\ell \pi}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg)^2 \bigg]. \end{aligned}\end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned}\gamma_{k} & = \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ p_k^2 + \bigg( \frac{\pi}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg)^2 \bigg], \\ \delta_{k,\ell} & = \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ p_k^2 + \bigg( \frac{\ell \pi}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg)^2 \bigg]. \end{aligned}\end{align} $$

Here, we have again made use of the integral (3.12). The differential equations in (3.19) are solved subject to the initial conditions

![]() $B_{k,\ell } (0) = 0$

to give

$B_{k,\ell } (0) = 0$

to give

$$ \begin{align} B_{k,\ell}(t) & = \mathcal{C}_{k,\ell}^B \bigg\{ \frac{\gamma_k}{\delta_{k,l}} [ \exp ( - \delta_{k,\ell} t ) - 1 ] \nonumber \\ &\quad + \frac{ ( 1 - \tau_F \gamma_k )}{( \tau_F \delta_{k,\ell} - 1 )} [ \exp ( - \delta_{k,\ell} t ) - \exp ( - t / \tau_F ) ] \bigg\}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} B_{k,\ell}(t) & = \mathcal{C}_{k,\ell}^B \bigg\{ \frac{\gamma_k}{\delta_{k,l}} [ \exp ( - \delta_{k,\ell} t ) - 1 ] \nonumber \\ &\quad + \frac{ ( 1 - \tau_F \gamma_k )}{( \tau_F \delta_{k,\ell} - 1 )} [ \exp ( - \delta_{k,\ell} t ) - \exp ( - t / \tau_F ) ] \bigg\}. \end{align} $$

In this expression, we have defined

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{C}_{k,\ell}^B = \frac{8 \ell}{\Lambda_k \pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )} \int_0^{R_{\infty}} r h(r) J_1 ( p_k r ) \, \textit{d} r, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{C}_{k,\ell}^B = \frac{8 \ell}{\Lambda_k \pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )} \int_0^{R_{\infty}} r h(r) J_1 ( p_k r ) \, \textit{d} r, \end{align} $$

and the constants

![]() $\gamma _k$

and

$\gamma _k$

and

![]() $\delta _{k,\ell }$

are as defined in (3.20).

$\delta _{k,\ell }$

are as defined in (3.20).

Finally, it is required to calculate linearized velocity components

![]() $U^L$

and

$U^L$

and

![]() $W^L$

in the radial and vertical directions so as to satisfy the (linearized) incompressibility condition (3.2). We do this by making use of an axisymmetric streamfunction

$W^L$

in the radial and vertical directions so as to satisfy the (linearized) incompressibility condition (3.2). We do this by making use of an axisymmetric streamfunction

![]() $\Psi ^L (r,z,t)$

. The linearized velocity vector is expressed as

$\Psi ^L (r,z,t)$

. The linearized velocity vector is expressed as

![]() $\mathbf {q}^L = \mathrm {curl} ( \Psi ^L \mathbf {e}_{\boldsymbol {\theta }} ) + V^L \mathbf {e}_{\boldsymbol {\theta }}$

so that (3.2) is satisfied identically by means of the relations

$\mathbf {q}^L = \mathrm {curl} ( \Psi ^L \mathbf {e}_{\boldsymbol {\theta }} ) + V^L \mathbf {e}_{\boldsymbol {\theta }}$

so that (3.2) is satisfied identically by means of the relations

$$ \begin{align} U^L (r,z,t) = - \frac{\partial \Psi^L}{\partial z}, \quad W^L (r,z,t) = \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial}{\partial r} ( r \Psi^L ). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} U^L (r,z,t) = - \frac{\partial \Psi^L}{\partial z}, \quad W^L (r,z,t) = \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial}{\partial r} ( r \Psi^L ). \end{align} $$

For simplicity, we choose to ignore the narrow boundary layer near the ground, and so allow horizontal slip at the plane

![]() $z=0$

. Nevertheless, there is no vertical velocity component there, so that the boundary condition

$z=0$

. Nevertheless, there is no vertical velocity component there, so that the boundary condition

![]() $W^L (r,0,t) = 0$

applies. In addition, no radial outflow can occur on the z-axis

$W^L (r,0,t) = 0$

applies. In addition, no radial outflow can occur on the z-axis

![]() $r=0$

, giving rise to a further boundary condition

$r=0$

, giving rise to a further boundary condition

![]() $U^L (0,z,t) = 0$

. These facts indicate that the appropriate form for the linearized streamfunction is therefore

$U^L (0,z,t) = 0$

. These facts indicate that the appropriate form for the linearized streamfunction is therefore

$$ \begin{align} \Psi^L (r,z,t) = \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} S_{m,n} (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \Psi^L (r,z,t) = \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} S_{m,n} (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \end{align} $$

It follows from (3.23) that the two velocity components in the r- and z-directions are

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} U^L (r,z,t) & = - \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \bigg( \frac{n \pi}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg) S_{m,n} (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \cos \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg),\\ W^L (r,z,t) & = \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} p_m S_{m,n} (t) J_0 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} U^L (r,z,t) & = - \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \bigg( \frac{n \pi}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg) S_{m,n} (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \cos \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg),\\ W^L (r,z,t) & = \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} p_m S_{m,n} (t) J_0 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

The coefficients

![]() $S_{m,n} (t)$

in the form (3.24) are found from the first and third components of the momentum equation, in the system (3.4). We define a linearized vorticity function

$S_{m,n} (t)$

in the form (3.24) are found from the first and third components of the momentum equation, in the system (3.4). We define a linearized vorticity function

$$ \begin{align} \Omega^L (r,z,t) = \frac{\partial U^L}{\partial z} - \frac{\partial W^L}{\partial r} , \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \Omega^L (r,z,t) = \frac{\partial U^L}{\partial z} - \frac{\partial W^L}{\partial r} , \end{align} $$

and observe that it satisfies the vorticity equation

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\partial \Omega^L}{\partial t} = \frac{\partial \rho^L}{\partial r} + \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ \nabla^2 \Omega^L - \frac{\Omega^L}{r^2} \bigg]. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\partial \Omega^L}{\partial t} = \frac{\partial \rho^L}{\partial r} + \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ \nabla^2 \Omega^L - \frac{\Omega^L}{r^2} \bigg]. \end{align} $$

It follows from (3.25) and (3.26) that the linearized vorticity function can be represented spectrally as

$$ \begin{align} \Omega^L (r,z,t) = \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \bigg[ p_m^2 + \bigg( \frac{n\pi}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg)^2 \bigg] S_{m,n} (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \Omega^L (r,z,t) = \sum_{m=1}^{\infty} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \bigg[ p_m^2 + \bigg( \frac{n\pi}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg)^2 \bigg] S_{m,n} (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \end{align} $$

The density function

![]() $\rho ^L$

in the vorticity equation (3.27) is eliminated in favour of the temperature perturbation

$\rho ^L$

in the vorticity equation (3.27) is eliminated in favour of the temperature perturbation

![]() $T^L$

using the relation (3.3), and the series (3.7), (3.28) are then incorporated into (3.27). Fourier analysis is performed as above, making use of the orthogonality properties of both the Bessel and the trigonometric functions and expression (3.12). This results in the system of ordinary differential equations

$T^L$

using the relation (3.3), and the series (3.7), (3.28) are then incorporated into (3.27). Fourier analysis is performed as above, making use of the orthogonality properties of both the Bessel and the trigonometric functions and expression (3.12). This results in the system of ordinary differential equations

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\textit{d} S_{k,\ell}(t)}{\textit{d} t} + \delta_{k,\ell} S_{k,\ell}(t) & = \frac{\alpha p_k}{[ p_k^2 + ( \ell\pi / Z_{\infty} )^2 ]} \bigg[ \frac{8\ell}{\pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )} A_{k,0} (t) + A_{k,\ell} (t) \bigg], \nonumber \\ & \quad k = 1, 2, \ldots, \quad \ell = 1, 2, \ldots. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\textit{d} S_{k,\ell}(t)}{\textit{d} t} + \delta_{k,\ell} S_{k,\ell}(t) & = \frac{\alpha p_k}{[ p_k^2 + ( \ell\pi / Z_{\infty} )^2 ]} \bigg[ \frac{8\ell}{\pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )} A_{k,0} (t) + A_{k,\ell} (t) \bigg], \nonumber \\ & \quad k = 1, 2, \ldots, \quad \ell = 1, 2, \ldots. \end{align} $$

The expressions (3.9) and (3.14) for the coefficients

![]() $A_{k,0}$

and

$A_{k,0}$

and

![]() $A_{k,\ell }$

are used in the right-hand sides of the differential equations (3.29), so that they can be solved in closed form. Since the flow starts from rest, the appropriate initial conditions are

$A_{k,\ell }$

are used in the right-hand sides of the differential equations (3.29), so that they can be solved in closed form. Since the flow starts from rest, the appropriate initial conditions are

![]() $S_{k,\ell } (0) = 0$

, and after some algebra we obtain

$S_{k,\ell } (0) = 0$

, and after some algebra we obtain

$$ \begin{align} S_{k,\ell}(t) & = \mathcal{C}_{k,\ell}^S \bigg\{ \frac{1}{\delta_{k,l} \Delta_{k,\ell}} [ 1 - \exp ( - \delta_{k,\ell} t ) ] \nonumber \\ & \quad + \frac{\tau_F^2} {( \tau_F \delta_{k,\ell} - 1 ) ( \tau_F \Delta_{k,\ell} - 1 )} [ \exp ( - \delta_{k,\ell} t ) - \exp ( - t / \tau_F ) ] \nonumber \\ & \quad + \frac{1}{\Delta_{k,\ell} ( \delta_{k,\ell} - \Delta_{k,\ell} ) ( \tau_F \Delta_{k,\ell} - 1 )} [ \exp ( - \Delta_{k,\ell} t ) - \exp ( - \delta_{k,\ell} t )] \bigg\}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} S_{k,\ell}(t) & = \mathcal{C}_{k,\ell}^S \bigg\{ \frac{1}{\delta_{k,l} \Delta_{k,\ell}} [ 1 - \exp ( - \delta_{k,\ell} t ) ] \nonumber \\ & \quad + \frac{\tau_F^2} {( \tau_F \delta_{k,\ell} - 1 ) ( \tau_F \Delta_{k,\ell} - 1 )} [ \exp ( - \delta_{k,\ell} t ) - \exp ( - t / \tau_F ) ] \nonumber \\ & \quad + \frac{1}{\Delta_{k,\ell} ( \delta_{k,\ell} - \Delta_{k,\ell} ) ( \tau_F \Delta_{k,\ell} - 1 )} [ \exp ( - \Delta_{k,\ell} t ) - \exp ( - \delta_{k,\ell} t )] \bigg\}. \end{align} $$

Here we have defined further constants

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{C}_{k,\ell}^S = \frac{\alpha p_k ( \Delta_{k,\ell} - \Gamma_k ) \mathcal{C}_{k,\ell}^A } { [ p_k^2 + ( \ell \pi / Z_{\infty} )^2 ]}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{C}_{k,\ell}^S = \frac{\alpha p_k ( \Delta_{k,\ell} - \Gamma_k ) \mathcal{C}_{k,\ell}^A } { [ p_k^2 + ( \ell \pi / Z_{\infty} )^2 ]}. \end{align} $$

In this formula, the constant

![]() $\alpha $

is the coefficient of thermal expansion in (2.10) and (3.3), and the quantities

$\alpha $

is the coefficient of thermal expansion in (2.10) and (3.3), and the quantities

![]() $\mathcal {C}_{k,\ell }^A$

have been defined above in (3.15).

$\mathcal {C}_{k,\ell }^A$

have been defined above in (3.15).

The complete linearized solution is therefore described by the series representations (3.7), (3.17) and (3.24), with velocity components

![]() $U^L$

and

$U^L$

and

![]() $W^L$

calculated from the series (3.25) and time-dependent Fourier coefficients found from expressions (3.9), (3.14) and (3.18), (3.21), (3.30). This solution requires that the temperature and the swirl component of the wind velocity vector should be given at ground level, and this, in turn, requires that choices be made for the two radial functions

$W^L$

calculated from the series (3.25) and time-dependent Fourier coefficients found from expressions (3.9), (3.14) and (3.18), (3.21), (3.30). This solution requires that the temperature and the swirl component of the wind velocity vector should be given at ground level, and this, in turn, requires that choices be made for the two radial functions

![]() $f(r)$

and

$f(r)$

and

![]() $h(r)$

in expressions (3.6) and (3.16).

$h(r)$

in expressions (3.6) and (3.16).

To fix ideas and enable the presentation of numerical results, we now make a choice for the ground-level temperature and swirl speed. The forms assumed for the temperature

![]() $T^L ( r,0,t )$

and speed

$T^L ( r,0,t )$

and speed

![]() $V^L ( r,0,t )$

are given in (3.6) and (3.16), and these involve shape functions

$V^L ( r,0,t )$

are given in (3.6) and (3.16), and these involve shape functions

![]() $f(r)$

and

$f(r)$

and

![]() $h(r)$

, respectively. For the ground-level temperature we choose

$h(r)$

, respectively. For the ground-level temperature we choose

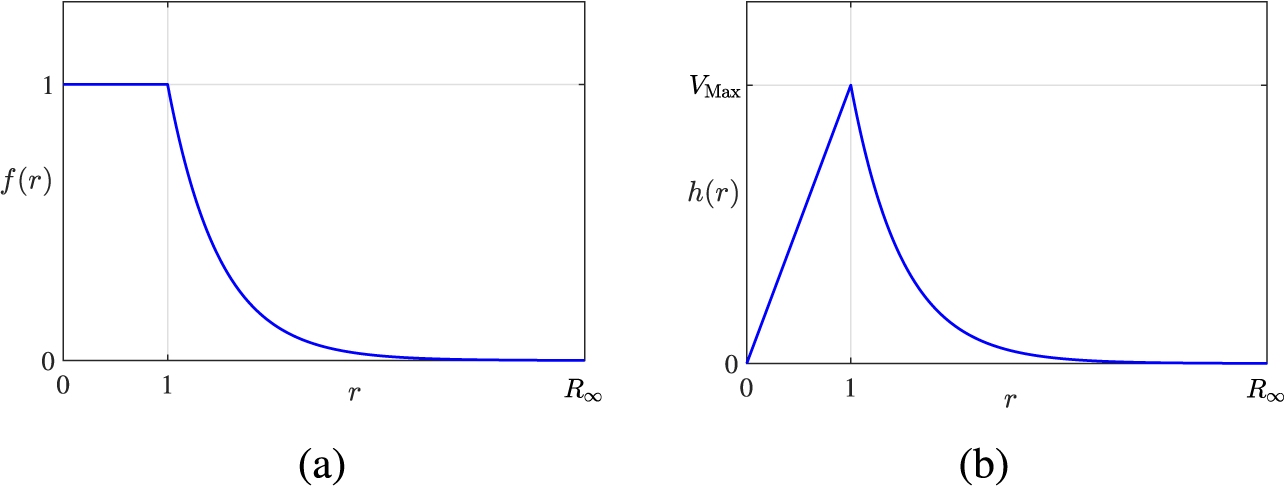

$$ \begin{align} f(r) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } 0<r<1, \\ \exp [ -\lambda (r-1) ] & \text{if } r>1, \end{cases} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} f(r) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } 0<r<1, \\ \exp [ -\lambda (r-1) ] & \text{if } r>1, \end{cases} \end{align} $$

and for the wind speed,

$$ \begin{align} h(r) = \begin{cases} V_{\mathrm\max} r& \text{if } 0<r<1, \\ V_{\mathrm\max} \exp [ -\lambda (r-1) ] & \text{if } r>1. \end{cases} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} h(r) = \begin{cases} V_{\mathrm\max} r& \text{if } 0<r<1, \\ V_{\mathrm\max} \exp [ -\lambda (r-1) ] & \text{if } r>1. \end{cases} \end{align} $$

These two functions are illustrated in Figure 2. The temperature perturbation function

![]() $f(r)$

is shown in (a), and consists of a constant temperature region inside the disk occupied by the “firenado”,

$f(r)$

is shown in (a), and consists of a constant temperature region inside the disk occupied by the “firenado”,

![]() $r < 1$

, and a region of exponential decay over the annulus

$r < 1$

, and a region of exponential decay over the annulus

![]() $r>1$

. Recall that, due to the linearization process (3.1), the ground-level temperature after a very long time is therefore

$r>1$

. Recall that, due to the linearization process (3.1), the ground-level temperature after a very long time is therefore

![]() $T(r,0,t) = 1 + \epsilon _F f(r)$

so that, far from the fire, the temperature returns to its ambient value

$T(r,0,t) = 1 + \epsilon _F f(r)$

so that, far from the fire, the temperature returns to its ambient value

![]() $T = 1$

at the ground. Figure 2(b) shows the shape function

$T = 1$

at the ground. Figure 2(b) shows the shape function

![]() $h(r)$

that defines the azimuthal wind velocity component

$h(r)$

that defines the azimuthal wind velocity component

![]() $v(r,0,t) = \epsilon _F h(r)$

at ground level after a long time. It is zero on the axis

$v(r,0,t) = \epsilon _F h(r)$

at ground level after a long time. It is zero on the axis

![]() $r=0$

of the firenado and rises linearly to some maximum value

$r=0$

of the firenado and rises linearly to some maximum value

![]() $V_{\mathrm {max}}$

at the radius

$V_{\mathrm {max}}$

at the radius

![]() $r=1$

of the fire, before falling exponentially to zero at very large distance r.

$r=1$

of the fire, before falling exponentially to zero at very large distance r.

These choices (3.32) and (3.33) for the functions

![]() $f(r)$

and

$f(r)$

and

![]() $h(r)$

are used to calculate the two sets of constants

$h(r)$

are used to calculate the two sets of constants

![]() $\mathcal {C}_{k,\ell }^A$

and

$\mathcal {C}_{k,\ell }^A$

and

![]() $\mathcal {C}_{k,\ell }^B$

in the quantities (3.15) and (3.22). The integrals in these expressions cannot be calculated in closed form, and so are evaluated numerically to very high accuracy, using the Gaussian quadrature routine lgwt.m written by von Winckel [Reference von Winckel22]. This then enables the calculation of the constants

$\mathcal {C}_{k,\ell }^B$

in the quantities (3.15) and (3.22). The integrals in these expressions cannot be calculated in closed form, and so are evaluated numerically to very high accuracy, using the Gaussian quadrature routine lgwt.m written by von Winckel [Reference von Winckel22]. This then enables the calculation of the constants

![]() $\mathcal {C}_{k,\ell }^S$

in (3.31). The coefficients

$\mathcal {C}_{k,\ell }^S$

in (3.31). The coefficients

![]() $A_{k,\ell } (t)$

,

$A_{k,\ell } (t)$

,

![]() $B_{k,\ell } (t)$

and

$B_{k,\ell } (t)$

and

![]() $S_{k,\ell } (t)$

are then evaluated and the linearized solutions calculated from their series expressions (3.7), (3.17) and (3.24), (3.25), (3.28).

$S_{k,\ell } (t)$

are then evaluated and the linearized solutions calculated from their series expressions (3.7), (3.17) and (3.24), (3.25), (3.28).

4 The nonlinear solution

The nonlinear model, described by equations (2.9)–(2.12), is in general too difficult to solve in closed form, and numerical methods are needed instead. To do this, we have adopted a semi-analytical technique in which the unknown solution functions are represented in Fourier series form, with unknown time-dependent Fourier coefficients that are to be determined numerically. This has the advantage that derivatives or integrals of these functions can essentially be found in closed form. As for the linearized approximate solution in Section 3, we seek axisymmetric solutions only, so as to keep computer runtimes within reasonable bounds.

Our spectral representation of the nonlinear solution variables is strongly guided by the linearized solution from Section 3. The incompressibility condition (2.9) is again satisfied identically by making use of a streamfunction

![]() $\Psi (r,z,t)$

from which the radial and vertical components u and w of the velocity vector

$\Psi (r,z,t)$

from which the radial and vertical components u and w of the velocity vector

![]() $\mathbf {q}$

can be calculated according to the relations

$\mathbf {q}$

can be calculated according to the relations

As with the linearized solution, the boundary conditions are that there is no vertical velocity component at the ground, so that

![]() $w = 0$

on

$w = 0$

on

![]() $z=0$

, and symmetry requires

$z=0$

, and symmetry requires

![]() $u=0$

on

$u=0$

on

![]() $r=0$

. Therefore the streamfunction can be represented approximately by the series

$r=0$

. Therefore the streamfunction can be represented approximately by the series

$$ \begin{align} \Psi (r,z,t) = \sum_{m=1}^M \sum_{n=1}^N S_{m,n}^N (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \Psi (r,z,t) = \sum_{m=1}^M \sum_{n=1}^N S_{m,n}^N (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \end{align} $$

This expression is essentially the same as the linearized representation (3.24) except that the series are terminated at finite Fourier modes M and N for computational reasons. The nonlinear coefficients

![]() $S_{m,n}^N (t)$

are also written with superscript N as a reminder that these values will in general be different from their linearized counterparts in (3.24). The two velocity components in (4.1) then take the spectral forms

$S_{m,n}^N (t)$

are also written with superscript N as a reminder that these values will in general be different from their linearized counterparts in (3.24). The two velocity components in (4.1) then take the spectral forms

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} u (r,z,t) & = - \sum_{m=1}^M \sum_{n=1}^N \bigg( \frac{n \pi}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg) S_{m,n}^N (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \cos \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg), \\ w (r,z,t) & = \sum_{m=1}^M \sum_{n=1}^N p_m S_{m,n}^N (t) J_0 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \begin{aligned} u (r,z,t) & = - \sum_{m=1}^M \sum_{n=1}^N \bigg( \frac{n \pi}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg) S_{m,n}^N (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \cos \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg), \\ w (r,z,t) & = \sum_{m=1}^M \sum_{n=1}^N p_m S_{m,n}^N (t) J_0 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \end{aligned} \end{align} $$

The constants

![]() $p_m$

are given in (3.8) and involve the zeros of the

$p_m$

are given in (3.8) and involve the zeros of the

![]() $J_0$

Bessel function. Following the linearized form (3.7), the choice of representation of the full nonlinear temperature is

$J_0$

Bessel function. Following the linearized form (3.7), the choice of representation of the full nonlinear temperature is

$$ \begin{align} T (r,z,t) & = 1 + \cos \bigg( \frac{\pi z}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \sum_{m=1}^M A_{m,0}^N (t) J_0 ( p_m r ) \nonumber \\ & \quad + \sum_{m=1}^M \sum_{n=1}^N A_{m,n}^N (t) J_0 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} T (r,z,t) & = 1 + \cos \bigg( \frac{\pi z}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \sum_{m=1}^M A_{m,0}^N (t) J_0 ( p_m r ) \nonumber \\ & \quad + \sum_{m=1}^M \sum_{n=1}^N A_{m,n}^N (t) J_0 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg), \end{align} $$

and the form for the fully nonlinear swirl velocity component is

$$ \begin{align} v (r,z,t) & = \cos \bigg( \frac{\pi z}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \sum_{m=1}^M B_{m,0}^N (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \nonumber \\ & \quad + \sum_{m=1}^M \sum_{n=1}^N B_{m,n}^N (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} v (r,z,t) & = \cos \bigg( \frac{\pi z}{2 Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \sum_{m=1}^M B_{m,0}^N (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \nonumber \\ & \quad + \sum_{m=1}^M \sum_{n=1}^N B_{m,n}^N (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \end{align} $$

The task is now to compute the sets of Fourier coefficients

![]() $A_{m,n}^N (t)$

,

$A_{m,n}^N (t)$

,

![]() $B_{m,n}^N (t)$

and

$B_{m,n}^N (t)$

and

![]() $S_{m,n}^N (t)$

for this nonlinear, axisymmetric problem.

$S_{m,n}^N (t)$

for this nonlinear, axisymmetric problem.

These forms (4.3)–(4.5) are now substituted into the nonlinear axisymmetric governing equations (2.11) and (2.12) and subject to Fourier analysis, using the orthogonality of both the trigonometric functions and the Bessel functions, in these representations. The boundary condition (2.14) at the ground

![]() $z=0$

leads to the requirement that

$z=0$

leads to the requirement that

$$ \begin{align} A_{k,0}^N (t) = \frac{\epsilon_F}{\Lambda_k} \bigg[ 1 - \exp \bigg( - \frac{t}{\tau_F} \bigg) \bigg] \int_0^{R_{\infty}} r f(r) J_0 ( p_k r) \, \textit{d} r, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} A_{k,0}^N (t) = \frac{\epsilon_F}{\Lambda_k} \bigg[ 1 - \exp \bigg( - \frac{t}{\tau_F} \bigg) \bigg] \int_0^{R_{\infty}} r f(r) J_0 ( p_k r) \, \textit{d} r, \end{align} $$

which is effectively the same as the linearized result (3.9), as expected. The constants

![]() $\Lambda _k$

are as defined previously in (3.10). Fourier analysis applied to the energy equation (2.12) gives rise to the system of ordinary differential equations

$\Lambda _k$

are as defined previously in (3.10). Fourier analysis applied to the energy equation (2.12) gives rise to the system of ordinary differential equations

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\textit{d} A_{k,\ell}^N (t)}{\textit{d} t} & = - \Delta_{k,\ell} A_{k,\ell}^N (t)\nonumber \\ &\quad - \frac{2}{Z_{\infty} \Lambda_k} \int_0^{Z_{\infty}} \int_0^{R_{\infty}} r \bigg(u \frac{\partial T}{\partial r} + w \frac{\partial T}{\partial z} \bigg) J_0 ( p_k r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{\ell \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \, \textit{d} r \, \textit{d} z \nonumber \\ & \quad - \frac{8\ell}{\pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )} \bigg[\frac{\textit{d} A_{k,0}^N (t)}{\textit{d} t} + \Gamma_k A_{k,0}^N (t) \bigg], \nonumber \\ & \qquad \quad k = 1, 2, \ldots , M, \quad \ell = 1, 2, \ldots , N. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\textit{d} A_{k,\ell}^N (t)}{\textit{d} t} & = - \Delta_{k,\ell} A_{k,\ell}^N (t)\nonumber \\ &\quad - \frac{2}{Z_{\infty} \Lambda_k} \int_0^{Z_{\infty}} \int_0^{R_{\infty}} r \bigg(u \frac{\partial T}{\partial r} + w \frac{\partial T}{\partial z} \bigg) J_0 ( p_k r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{\ell \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \, \textit{d} r \, \textit{d} z \nonumber \\ & \quad - \frac{8\ell}{\pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )} \bigg[\frac{\textit{d} A_{k,0}^N (t)}{\textit{d} t} + \Gamma_k A_{k,0}^N (t) \bigg], \nonumber \\ & \qquad \quad k = 1, 2, \ldots , M, \quad \ell = 1, 2, \ldots , N. \end{align} $$

This is the nonlinear equivalent of the linearized system in (3.11), and consists of

![]() $MN$

ordinary differential equations for the nonlinear coefficients

$MN$

ordinary differential equations for the nonlinear coefficients

![]() $A_{m,n}^N (t)$

. Here, the constants

$A_{m,n}^N (t)$

. Here, the constants

![]() $\Gamma _k$

and

$\Gamma _k$

and

![]() $\Delta _{k,\ell }$

are the same as those defined in (3.13). The terms on the right-hand side of these equations (4.7) are known from (4.6).

$\Delta _{k,\ell }$

are the same as those defined in (3.13). The terms on the right-hand side of these equations (4.7) are known from (4.6).

Fourier analysis is similarly applied to the

![]() $\theta $

-component of the momentum equation in (2.11). To begin, a boundary condition for the swirl velocity component v is specified on

$\theta $

-component of the momentum equation in (2.11). To begin, a boundary condition for the swirl velocity component v is specified on

![]() $z=0$

(since slip is allowed on this effective ground plane, modelling the effect of flow through the burning canopy of the bushland). The nonlinear equivalent of the linearized condition (3.16) is

$z=0$

(since slip is allowed on this effective ground plane, modelling the effect of flow through the burning canopy of the bushland). The nonlinear equivalent of the linearized condition (3.16) is

and so it follows from (4.5) that

$$ \begin{align} B_{k,0}^N (t) = \frac{\epsilon_F}{\Lambda_k} \bigg[ 1 - \exp \bigg( - \frac{t}{\tau_F} \bigg) \bigg] \int_0^{R_{\infty}} r h(r) J_1 ( p_k r ) \, \textit{d} r. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} B_{k,0}^N (t) = \frac{\epsilon_F}{\Lambda_k} \bigg[ 1 - \exp \bigg( - \frac{t}{\tau_F} \bigg) \bigg] \int_0^{R_{\infty}} r h(r) J_1 ( p_k r ) \, \textit{d} r. \end{align} $$

The azimuthal component of the momentum equation then gives

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\textit{d} B_{k,\ell}^N (t)}{\textit{d} t} & = - \delta_{k,\ell} B_{k,\ell}^N (t) \nonumber \\ & \quad - \frac{2}{Z_{\infty} \Lambda_k} \int_0^{Z_{\infty}} \int_0^{R_{\infty}} \bigg(ru \frac{\partial v}{\partial r} + rw \frac{\partial v}{\partial z} + uv \bigg)J_1 ( p_k r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{\ell \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \, \textit{d} r \, \textit{d} z \nonumber \\ & \quad - \frac{8\ell}{\pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )} \bigg[\frac{\textit{d} B_{k,0}^N (t)}{\textit{d} t} + \gamma_k B_{k,0}^N (t) \bigg]. \nonumber \\ & \qquad \quad k = 1, 2, \ldots , M, \quad \ell = 1, 2, \ldots , N. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\textit{d} B_{k,\ell}^N (t)}{\textit{d} t} & = - \delta_{k,\ell} B_{k,\ell}^N (t) \nonumber \\ & \quad - \frac{2}{Z_{\infty} \Lambda_k} \int_0^{Z_{\infty}} \int_0^{R_{\infty}} \bigg(ru \frac{\partial v}{\partial r} + rw \frac{\partial v}{\partial z} + uv \bigg)J_1 ( p_k r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{\ell \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg) \, \textit{d} r \, \textit{d} z \nonumber \\ & \quad - \frac{8\ell}{\pi ( 2\ell - 1 ) ( 2\ell + 1 )} \bigg[\frac{\textit{d} B_{k,0}^N (t)}{\textit{d} t} + \gamma_k B_{k,0}^N (t) \bigg]. \nonumber \\ & \qquad \quad k = 1, 2, \ldots , M, \quad \ell = 1, 2, \ldots , N. \end{align} $$

The linearized approximation to this equation is (3.19) in Section 3, and the constants

![]() $\gamma _k$

and

$\gamma _k$

and

![]() $\delta _{k,\ell }$

are given in (3.20). The right-hand sides of (4.9) can be evaluated in closed form, since the coefficients

$\delta _{k,\ell }$

are given in (3.20). The right-hand sides of (4.9) can be evaluated in closed form, since the coefficients

![]() $B_{k,0}^N (t)$

are known from (4.8).

$B_{k,0}^N (t)$

are known from (4.8).

It remains to find a system of equations whereby the coefficients

![]() $S_{m,n}^N (t)$

may be determined. For the linearized solution, this was achieved by defining a linearized vorticity (3.26) and observing that it satisfied the linearized vorticity equation (3.27). A similar approach is also available for the fully nonlinear problem. We create the vorticity function

$S_{m,n}^N (t)$

may be determined. For the linearized solution, this was achieved by defining a linearized vorticity (3.26) and observing that it satisfied the linearized vorticity equation (3.27). A similar approach is also available for the fully nonlinear problem. We create the vorticity function

It follows from (4.3) that the vorticity can be represented spectrally as

$$ \begin{align} \omega (r,z,t) = \sum_{m=1}^M \sum_{n=1}^N \bigg[ p_m^2 + \bigg( \frac{n\pi}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg)^2 \bigg] S_{m,n}^N (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \omega (r,z,t) = \sum_{m=1}^M \sum_{n=1}^N \bigg[ p_m^2 + \bigg( \frac{n\pi}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg)^2 \bigg] S_{m,n}^N (t) J_1 ( p_m r ) \sin \bigg( \frac{n \pi z}{Z_{\infty}} \bigg). \end{align} $$

By taking the vector curl of the momentum equation (2.11), the pressure p is eliminated, leaving the nonlinear vorticity equation

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\partial \omega}{\partial t} + u \frac{\partial \omega}{\partial r} + w \frac{\partial \omega}{\partial z} - \frac{u \omega}{r} - \frac{2v}{r} \frac{\partial v}{\partial z} = - \alpha \frac{\partial T}{\partial r} + \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial}{\partial r} \bigg( r \frac{\partial \omega}{\partial r} \bigg) + \frac{\partial^2 \omega}{\partial z^2} - \frac{\omega}{r^2} \bigg]. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \frac{\partial \omega}{\partial t} + u \frac{\partial \omega}{\partial r} + w \frac{\partial \omega}{\partial z} - \frac{u \omega}{r} - \frac{2v}{r} \frac{\partial v}{\partial z} = - \alpha \frac{\partial T}{\partial r} + \frac{1}{R_e} \bigg[ \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial}{\partial r} \bigg( r \frac{\partial \omega}{\partial r} \bigg) + \frac{\partial^2 \omega}{\partial z^2} - \frac{\omega}{r^2} \bigg]. \end{align} $$

In this expression, we have eliminated density in favour of temperature, using the equation of state (2.10).

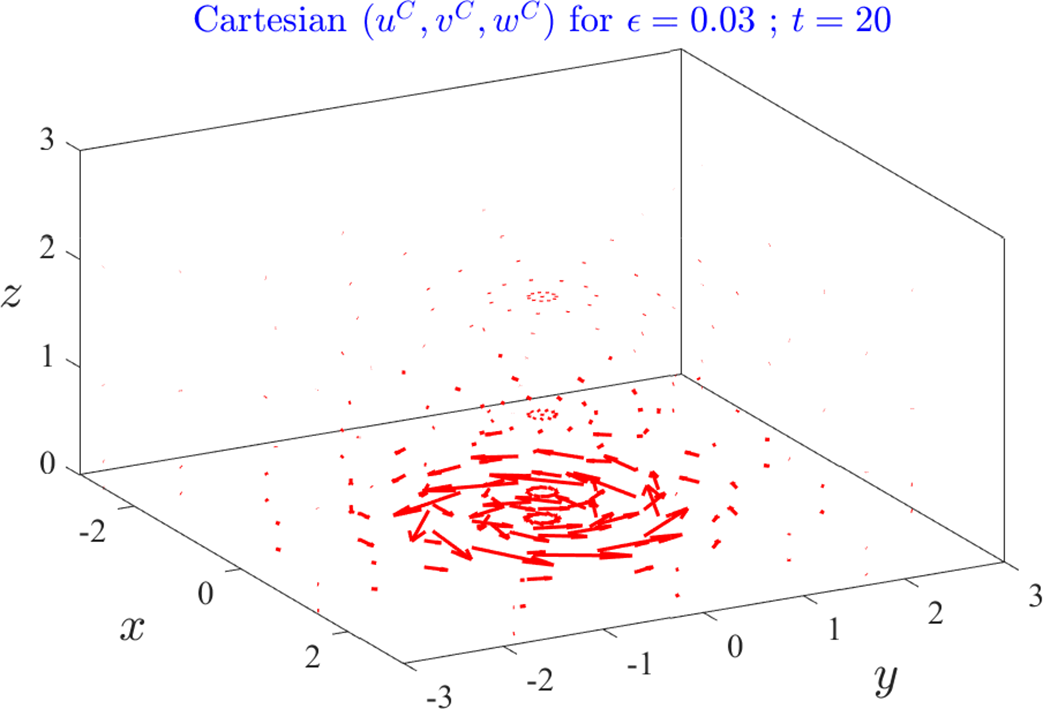

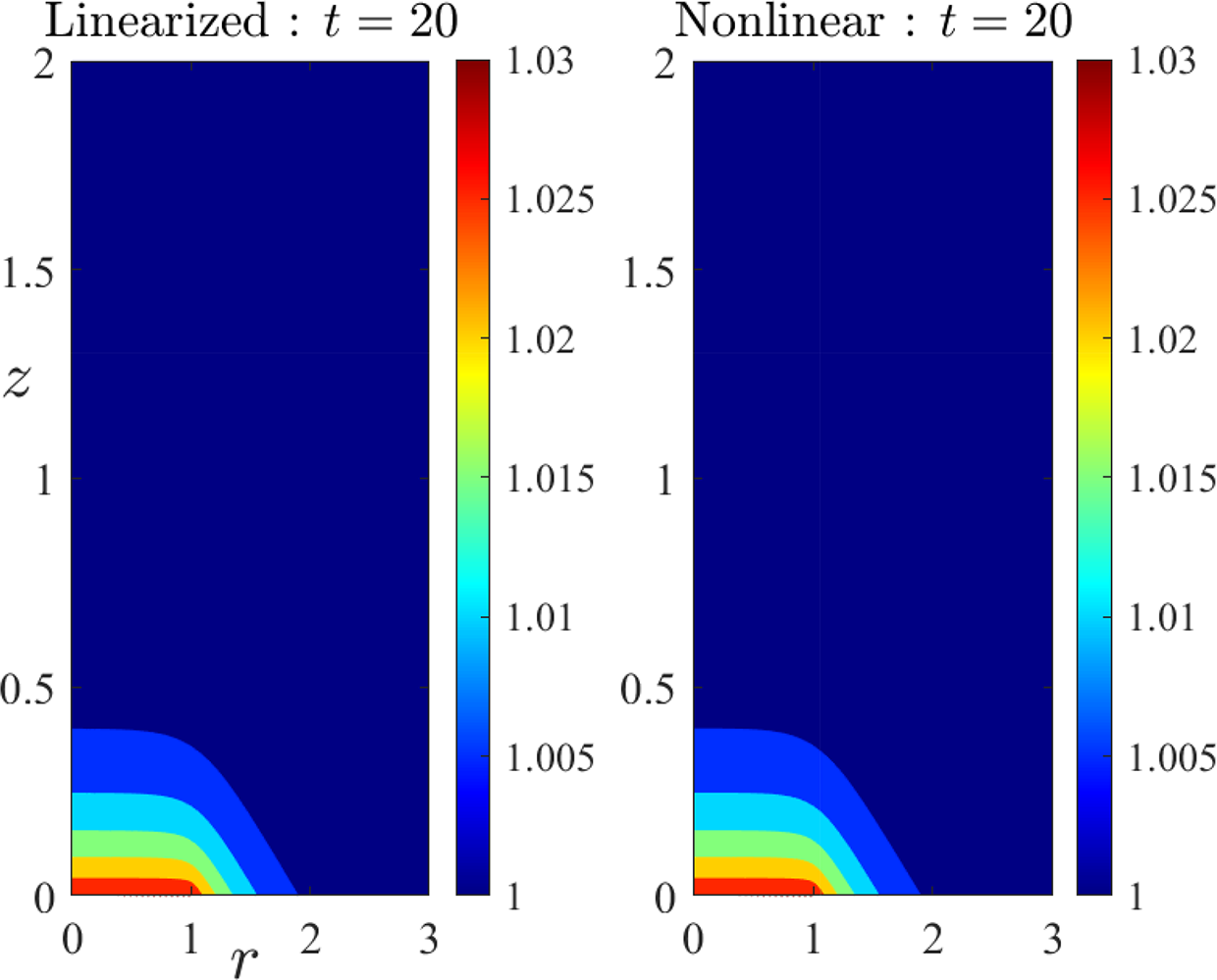

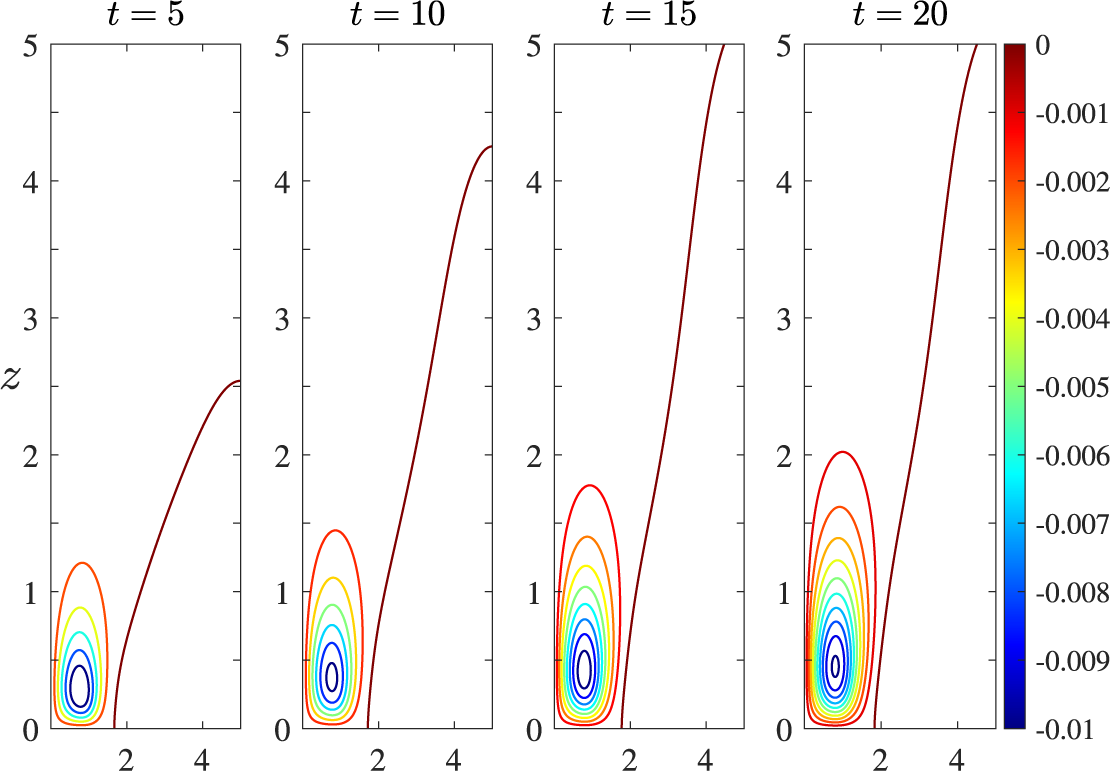

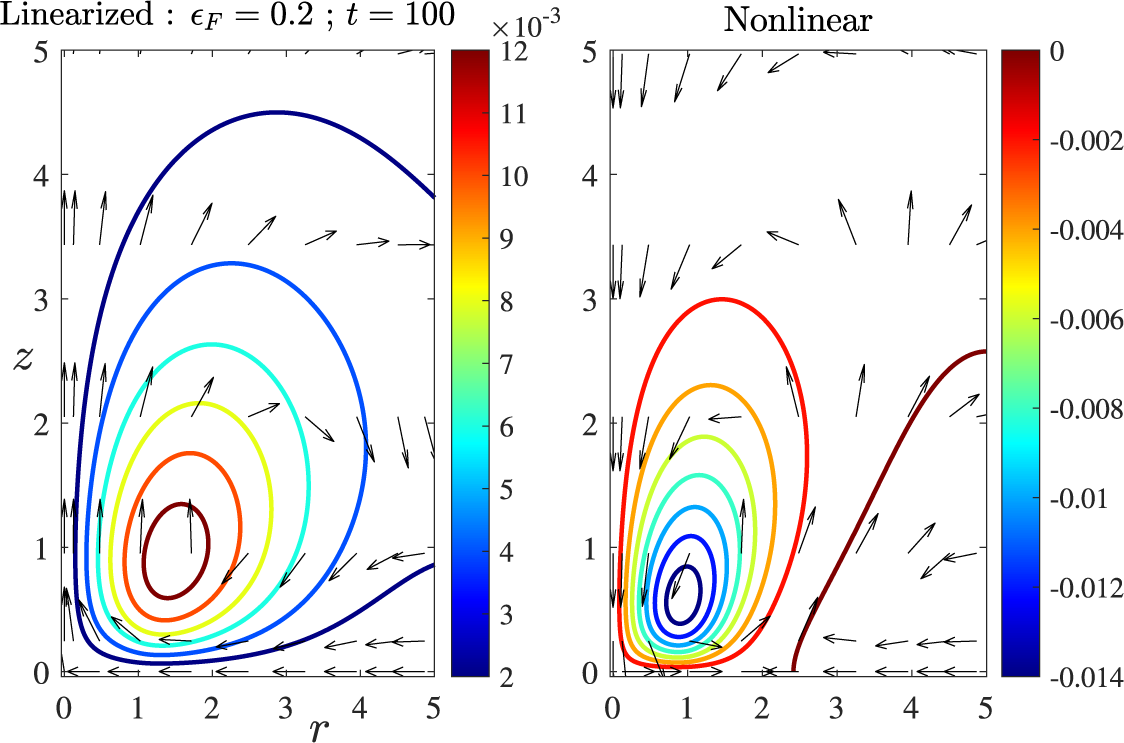

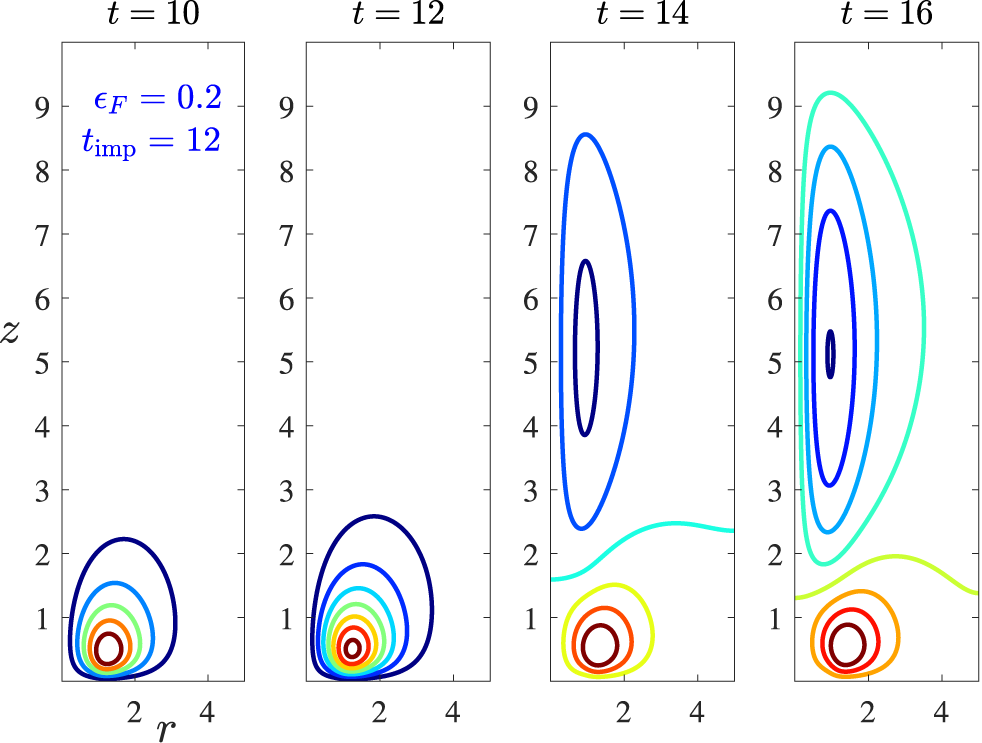

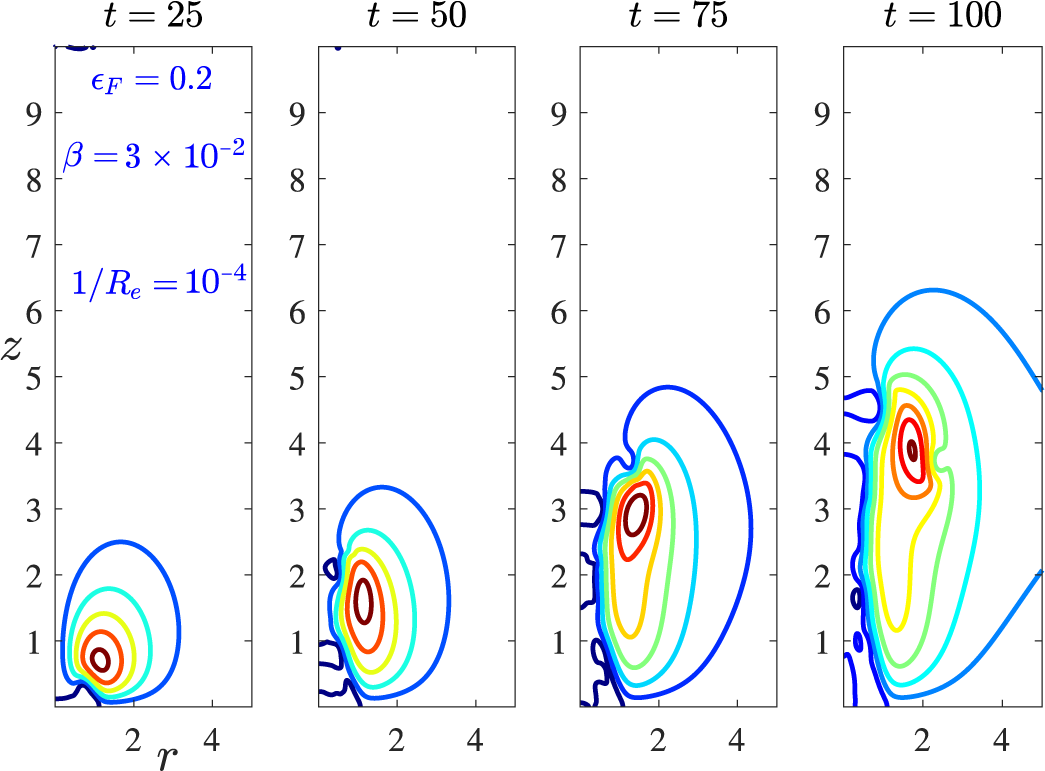

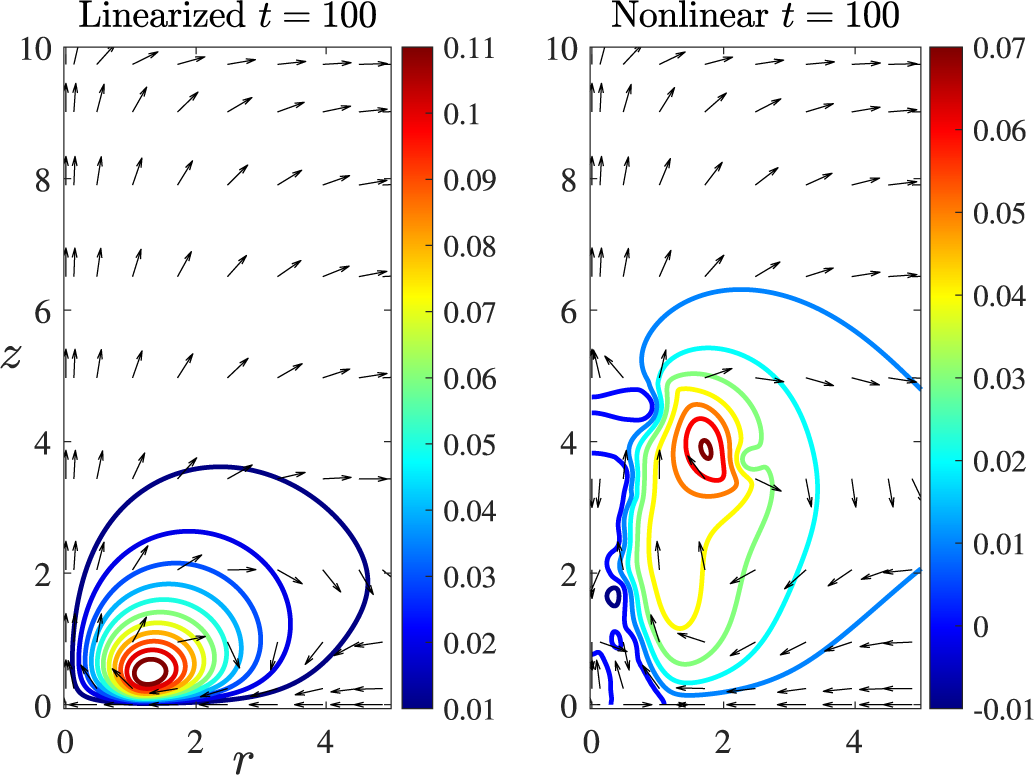

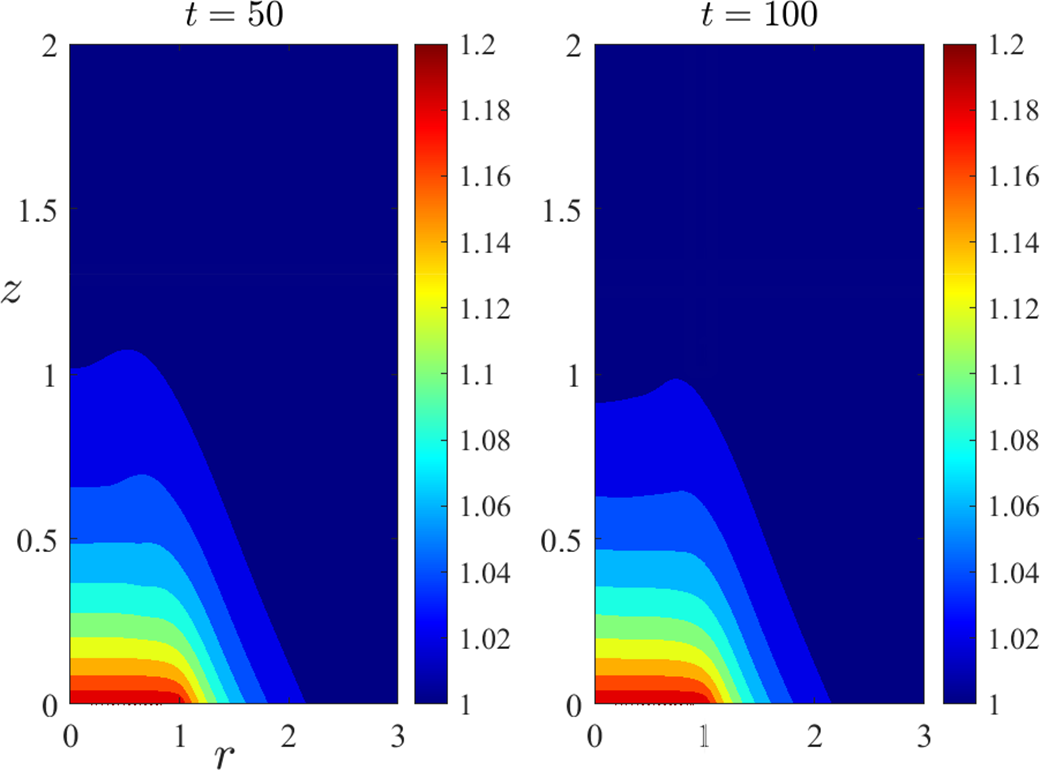

The spectral series (4.10) is now incorporated into the nonlinear vorticity equation (4.11) and Fourier analysis is carried out. After some algebra, this leads to the system of differential equations