Since modernity, every project of genuine human emancipation has aimed at preventing the human from being treated as an object … [If] the human also begins to … see to it that objects and other animate and inanimate entities are also endowed with the same rights as humans, what does this signal in terms of the future of the political as such?

Achille MbembeFootnote 1

As told by important early figures, the emergence of nonhuman personhood in the early 1970s was the result of circumstances so contingent that it appears to have been almost accidental.Footnote 2 Legal scholar Christopher Stone, whose 1972 article “Should Trees Have Standing?” launched worldwide debate on the rights of nature, recounts the impetus for his argument as a desperate attempt to galvanize bored students in the closing minutes of his property law class: “‘So,’ I wondered aloud, reading their glazing skepticisms, ‘what would a radically different law-driven consciousness look like? … One in which Nature had rights.’”Footnote 3 The article was an attempt to answer this question, “tossed off in the heat of lecture.”Footnote 4 Philosopher Peter Singer, whose classic call for “Animal Liberation” in 1973 inspired countless animal rights activists, credits his philosophy to a chance lunch with a vegetarian friend during graduate school.Footnote 5 This one meal led him to realize that “by eating animals I was participating in a systematic form of oppression of other species by my own species.”Footnote 6 A movement for the radical reconsideration of animals’ moral status was thus born (or, at least, so it seems).

These fortuitous events, Stone and Singer implied, allowed them to see what should have been obvious all along. Complementing the accounts of sudden epiphany, their substantive arguments employed the narrative of a “natural” extension of rights and equality from marginalized humans to nonhumans.Footnote 7 The writers drew on a narrative of liberal progress to contend that in the past, people of color, women, queer people, and other humans deviating from the white, heterosexual, male citizen had one by one gained personhood—moral and legal recognition in their own right.Footnote 8 Now, it was animals’ and nature’s turn. This almost deterministic justification to extend the moral and legal sphere to nonhumans dominated the writings of Singer’s and Stone’s peers in early advocacy against anthropocentrism. The progress of history, they asserted, would inevitably come to recognize animals and nature as persons.

Scholars have replicated such rhetoric of inexorable historical progression in the secondary literature. In a particularly striking example, one influential environmental historian argued that the emergence of nonhuman rights was the “logical extrapolation of powerful liberal traditions as old as the republic.”Footnote 9 Rather than take such narratives for granted, this article shows how a reliance on teleological progress as historical explanation has obscured both the political and the historical specificity of nonhuman personhood, an idea that activists have increasingly employed as legal strategy in recent years.Footnote 10 Singer, Stone, and other thinkers sought to reject liberalism’s anthropocentrism in the early 1970s, an especially dynamic time in the politics of humanism—a historical context missed by scholars of animals and the environment because they have tended to analyze animal and environmental advocacy separately or to otherwise emphasize their intellectual differences and antagonisms.Footnote 11 Conversely, scholars of humanist politics have overlooked the implications of new assertions of humanism for animals and nature, who posed a distinct conceptual challenge to liberal politics.Footnote 12

In fact, it was the humanist politics of 1960s civil rights and liberation movements that allowed Singer and Stone to place animals and nature in a narrative of progress to reject liberalism’s anthropocentrism from within.Footnote 13 Stone leveraged courts as sites where social norms around gender and race had been remade during the civil rights movement to more broadly challenge law’s privileging of the human individual.Footnote 14 He published “Should Trees Have Standing?” to intervene in the impending Supreme Court case of Sierra Club v. Morton, arguing that nature should have legal standing to sue for its own preservation. Courts, which traditionally enforced the duties and obligations of the liberal human individual, could also institute more expansive ways of considering who, or what, could be a person. Singer also condemned the privileged position of humans by positioning systemic discrimination based on a species criterion as an obstacle to equality that would fall, as had race, gender, and sex in 1960s civil rights and liberation movements.Footnote 15 He mobilized Bentham’s utilitarian calculation between pain and pleasure toward anti-anthropocentric ends by asserting that equal moral consideration of animals required rejecting practices that needlessly increased their suffering, such as animal experimentation and factory farming.

But by drawing on courts and identity politics to extend 1960s liberal progress to nonhumans, Singer and Stone obscured the radical humanism undergirding these narratives of progress. Oppressed minorities had asserted that race, gender, and sex posed no barrier to the exercise of political agency inherent in humanity—and thus could not bar any humans from personhood. Yet unlike the humans who had claimed personhood through political acts such as voting, civil disobedience, litigation, or violent resistance, nonhumans could not make political claims.Footnote 16 In Singer’s words, animals were incapable “of protesting against their exploitation by votes, demonstrations, or bombs.”Footnote 17 The same could be said of nature. In contrast to exploited humans who had the creative agency—however constrained—to change their conditions, nonhumans were voiceless victims incapable of themselves taking such actions. At a fundamental level, anti-anthropocentric thinkers’ call to expand legal and moral personhood to animals and nature unable to make political claims necessitated a reworking of the very idea of political agency. What would a politics for and in the name of nonhumans look like?

Singer and Stone were confronted by this particular challenge that nonhumans posed to liberal politics as the radical humanism of the 1960s gave way to the incipient human rights movement and a humanitarian ethos of the 1970s. As human rights activists foregrounded the torture of dissidents, and humanitarians highlighted Third World famines to call attention to a humanity defined by suffering, the writers contended that animals and even nature suffered as humans do.Footnote 18 Relying on an emergent humanist concern with suffering, they formulated nonhuman personhood as a problem of empathetic identification: humans’ and nonhumans’ shared ability to suffer allowed humans to see how animals and nature were like them and therefore deserving of personhood. Caught between 1960s challenges to liberal humanism and 1970s humanist preoccupation with suffering, the anti-anthropocentric thinkers replaced a “common humanity” with “shared suffering” as the basis for personhood.Footnote 19

Writers attempting to reject anthropocentrism from within the liberal tradition therefore turned to shared suffering to dissolve the distinction between humans and nonhumans; in asserting human empathy for nonhuman suffering as the basis for their personhood, however, they reinscribed a more fundamental distinction between those able and those unable to make political claims. In situating the emergence of nonhuman personhood within the context of shifting humanist politics in the early 1970s, I thus show how advocates put forth an anti-anthropocentric humanism that preserved the conceptual limitations of liberal politics for voiceless victims within their rejection of anthropocentrism. In what follows, I focus on Singer’s and Stone’s texts but analyze them alongside a range of contemporaneous works, including legal scholar Laurence Tribe’s “Ways Not to Think about Plastic Trees” (1974) and philosopher Tom Regan’s “The Moral Basis of Vegetarianism” (1975).Footnote 20 Published in a span of four years, they were often discussed together by contemporaries and encapsulate major arguments in early support for nonhuman personhood.Footnote 21 I first detail the 1960s humanist developments that, on the one hand, challenged the boundary of humanity and, on the other, sought to incorporate difference within humanity: not only civil rights and liberation movements, but abortion debates, technological advances like genetic manipulation, and environmental concerns also provided the conditions for writers to reject anthropocentrism. I then demonstrate how they turned to an incipient 1970s humanist attention to suffering to work through the conceptual problem of animals and nature as victims unable to make political claims. Lastly, I discuss how this turn to suffering reworked the relationship between existing persons and those not yet recognized as such, dissolving some distinctions while sustaining others. This refiguration had conceptual and political implications not only for suffering nonhumans, but for suffering humans as well.

Making successive persons

At a 1971 conference, moral and legal philosopher Joel Feinberg mapped out an array of entities on the spectrum between “rocks and normal human beings” to which rights could arguably be ascribed. Animals, plants, dead humans, species, human “vegetables,” fetuses, and unborn generations constituted the “bewildering borderline” cases populating the blurred zone between full rights-bearing subjects and, to him, obviously rightless inanimate objects.Footnote 22 If to have a right means to have a claim to something against someone, then the beings with rights are those who have, or can have, interests. Individual animals, with conative urges that shape their interests, have rights, as do fetuses and unborn generations, whose future interests can be represented by proxies in the present.

Feinberg was not pondering the rights of these cases in abstraction. The conference at which he presented was dedicated to Philosophy and the Environmental Crisis. In the 1960s, technological advances like genetic manipulation as well as environmental concerns such as overpopulation had applied pressure to the boundedness of the “human”: humans were malleable and constituted in relation to the environment.Footnote 23 Responding to such worries, Feinberg was one of the first scholars within the tradition of analytical moral and legal philosophy to question the autonomous human individual as the assumed subject of moral systems. What about the brain-dead, kept at the edge of life by medical technologies? Or the unborn who would suffer the consequences of environmental degradation?Footnote 24 In the same period, the rights of fetuses also became a high-stakes question as courts across the United States grappled with the legality of abortion.Footnote 25 Commentators, recognizing the state’s investment in securing potential life, negotiated trade-offs between fetal rights and women’s rights.Footnote 26 Feinberg brought the challenges posed by technological advances, environmentalism, and abortion politics in the 1960s into philosophy. He focused attention on former and future humans—fetuses, unborn generations, and the dead—to muddy the boundaries of the “human” in moral and legal thought.

In surveying whether various entities have interests, Feinberg contested assumptions associating rights solely with autonomous human individuals. But he conducted his investigation through an understanding of interest based on that of the liberal human individual—in other words, anthropocentrism was not yet being challenged. For instance, he argued that species did not have rights because it could not have wants like an individual could: “Individual elephants can have interests, but the species elephant cannot.”Footnote 27 He conceded that one could consider species as a collection of individuals analogous to corporate entities such as states and business corporations, which had been ascribed legal personality since medieval times.Footnote 28 But those corporate entities had “human beings” acting on their behalf according to a charter or constitution that defined their interests, while species did not. By emphasizing the human basis of corporations, Feinberg was drawing on a long tradition of legal scholarship that analyzed how incorporating human persons into a collective allowed the perpetuation of interests.Footnote 29 Corporations were nonhuman persons, but they incorporated human persons in order to persist through time.Footnote 30 For him, species thus had no rights because they were not represented by “definite flesh and blood persons … individual persons, acting in their ‘official capacities.’”Footnote 31 While Feinberg blurred the edges of liberalism’s autonomous human individual, he stopped short of challenging its privileged position in morality and law.

If developments in technology, environmentalism, and abortion had led Feinberg to question the status of the human individual, less than two years later, in 1973, Singer drew on another 1960s movement—activism for liberation and civil rights—to reject anthropocentrism altogether. “Animal Liberation,” published in the New York Review of Books in 1973 and elaborated in articles and a book in subsequent years, opened by placing animals after a succession of oppressed humans: “We are familiar with Black Liberation, Gay Liberation, and a variety of other movements. With Women’s Liberation some thought we had come to the end of the road.”Footnote 32 But women would not be the last to be liberated. Next, Singer declared, were animals. Indeed, the “tyranny of human over nonhuman animals,” he wrote in the first line of his expanded book, was comparable to the “centuries of tyranny by white humans over black humans.”Footnote 33 Singer framed the struggle against exploitation of animals as a continuation of 1960s movements that had contested the purported universality of the liberal human individual, and even occasionally employed rights language as a “concession to popular moral rhetoric” despite rejecting a rights framework.Footnote 34 Black people, gay people, and women had fought to expand liberal humanism to oppressed minorities. Singer presented animals as akin to these groups of humans who had one by one gained moral and legal recognition. As historical progress had made them into persons, it would do the same for animals.

Singer bolstered his historical determinism by presenting “species” as yet another category through which systemic oppression was perpetuated. Having written his Oxford thesis on civil disobedience, Singer was attuned to how political developments—the Nuremberg trials, nuclear disarmament, the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War—had revealed to the public that states abused their power against vulnerable beings on the basis of race or war aims. These revelations of entrenched subjugation had fundamentally challenged long-standing moral precepts, like the obligation to obey state power.Footnote 35 The late 1960s and early 1970s in the United States, he opined, seemed particularly “turbulent,” even if there was not much more political violence than was usual in the past 150 years. Citizens were practicing civil disobedience for relatively minor issues, not just major ones like war.Footnote 36 People now knew that race, gender, and sex structured one’s relationship to power; Singer sought to add “species” to their understanding of oppression. Working from utilitarian premises where the ability to suffer was the sole criterion for whether a being’s interests matter, Singer contended that because animals could feel pain, their interests and those of humans had to be considered equally in moral calculations.Footnote 37 He embraced the term “speciesism”—a direct parallel of racism—to denounce the anthropocentrism of prevailing moral and legal systems.Footnote 38 Drawing on 1960s movements’ humanist challenge to incorporate difference into humanity, he placed animals within a history of subjugation to argue that equal moral consideration of animals would dispel the anthropocentrism of society’s “idea that nonhumans are utilities, means to our ends.”Footnote 39 Liberal morality needed to extend beyond humanity.

Writing at almost exactly the same time as Singer, Stone also put nature into progressive narratives of ever-expanding rights and equality. He intervened in the Supreme Court case of Sierra Club v. Morton by arguing for the legal personhood of “natural objects”—trees, forests, rivers, and other environmental entities. While the case hinged on whether the Sierra Club had standing to sue the Secretary of Interior for allowing the development of Mineral King Valley, Stone contended that the club’s standing was irrelevant because the valley itself was the legal person who would suffer damages should development proceed. He foregrounded prior recognition of oppressed humans’ personhood to make the case for nonhumans. For much of the past, the child had been seen as “less than a person: an object, a thing,” but children had now been made “persons,” as had been done with “prisoners, aliens, women (especially of the married variety), the insane, Blacks, foetuses, and Indians.”Footnote 40 Before each of these “rightless thing[s]” had received rights, their legal personhood had been inconceivable, as was now the case for nature.Footnote 41 Considered historically, law simply constructed persons based on the needs of the time; if it had once adjusted to recognize the personhood of humans excluded from law—such as slaves and medieval Jews—it could do the same for nature.

This provocation was more than just a call for personhood for natural objects. Stone was denouncing law in general for presuming the individual human being as its ontological unit. His background had long sensitized him to the shortcomings of anthropocentric law for dealing with corporations, medieval legal scholars’ way of “work[ing] out the most elaborate conceits and fallacies to serve as anthropomorphic flesh” for church and state.Footnote 42 Though corporations were a legal fiction, they tended to be “treated indiscriminately like any other person” “once they have met certain formal requirements of ‘birth’ (incorporation).”Footnote 43 Law’s extrapolation of human individuality to corporations, he later argued, was what made the latter so difficult to reform. Corporations did not have sacrosanct minds like individual humans; instead of treating them as such, reforms should intervene at the level of information transmission within corporations and between corporations and the public sector.Footnote 44 Information theory and systems theory clearly informed his critique of human individuality, as did psychoanalysis, existentialism, and spiritualism.Footnote 45 He was drawn to philosopher Norman Brown, who cited Sándor Ferenczi’s and Melanie Klein’s theories that every person introjects and projects onto other persons to argue that every person was actually “many persons; a multitude made into one person; a corporate body; incorporated, a corporation.”Footnote 46 The bounded liberal human individual as such did not exist: “It is more and more the individual human being … that is the legal fiction.”Footnote 47 Personhood of natural objects was as plausible as that of corporations or even humans. Stone used nonhuman personhood to demand a fundamental rethinking of the anthropocentric presuppositions of liberal law more broadly.

Championing a narrative of liberal progress by extrapolating rights and liberation movements’ humanist expansion of personhood onto animals and nature, Stone’s and Singer’s attempts to dismantle the anthropocentrism of liberal law and morality were extremely influential. By the late 1970s, hundreds of articles every year were being published on animal and environmental ethics, and several suits had been filed on behalf of natural objects.Footnote 48 Justice William Douglas, in his dissent to the Court’s 5–4 ruling in Sierra Club v. Morton, cited Stone’s article to argue that “[c]ontemporary public concern for protecting nature’s ecological equilibrium should lead to the conferral of standing upon environmental objects to sue for their own preservation … This suit would therefore be more properly labeled as Mineral King [Valley] v. Morton.”Footnote 49 Commentators seized upon his remarks, often with ridicule. Yet in so doing, they amplified them beyond the legal realm and introduced the concept of personhood into broader debates about humans’ relationship with the environment.Footnote 50 And though Singer eschewed the framework of rights, his call for animal liberation, by many accounts, sparked the modern animal rights movement.Footnote 51

The two operated in different philosophical traditions within liberal thought. But myriad 1960s developments—abortion politics, environmentalism, and technological advancements that blurred the boundaries of the autonomous human individual, as well as the humanist challenge posed by rights and liberation movements—opened up a conceptual space for both writers to place nonhumans into a historical narrative of liberal progress. Their attempt to repudiate the anthropocentrism of liberalism from within inspired other influential writers of varied backgrounds to do the same. Tom Regan, the most famous animal ethicist after Singer, wrote against Singer’s utilitarianism to argue for a rights-based approach to animal ethics in 1975.Footnote 52 Like Singer, however, he rejected human exceptionalism and the two collaborated to contend that humans had no special moral status.Footnote 53 And constitutional scholar Lawrence Tribe, who in 1974 published a foundational article condemning the anthropocentrism of quantitative cost–benefit approaches to environmental law, was informed by research and practice in federal technology policy.Footnote 54 As late as 1971 he had taken an “openly anthropocentric perspective” in assessing technology’s effects on society and the environment.Footnote 55 But just a year later, he cited Stone to assert the importance of considering possible “non-anthropocentric foundations” of law, and his 1974 article referenced Stone to reject the “homocentric logic of self-interest” in positivist, utilitarian, and justice-based law.Footnote 56 Drawing on Max Horkheimer, he contended that the anthropocentrism undergirding contemporary moral and legal systems was inextricable from an instrumentalism implicit in humanism. Thinkers from Aquinas to “moral theorists in the tradition of contemporary liberal individualism,” of which John Rawls was representative, all relied on instrumental rationality, with devastating consequences for nature.Footnote 57 Law could institute values: rejecting the “homocentrism” of environmental policy would move society away from privileging ends over means. Tribe melded anti-anthropocentrism with a mid-century skepticism of instrumentalism. Not just “homocentric” law, but also the liberalism that sustained it, needed to be rethought.

Singer, Stone, Regan, and Tribe, writing almost simultaneously, sought to unravel liberalism’s anthropocentrism from within. In the 1960s, movements campaigning around overpopulation, environmentalism, abortion, and technological manipulation of humans had blurred the edges of the autonomous human individual at the center of liberal law and morality. In the following years, the writers drew on other activism in the 1960s—rights and liberation movements—to analogize nonhumans to a succession of oppressed humans demanding personhood. In doing so, they attempted to decenter humanity altogether. The widespread uptake of their ideas recapitulated Singer’s and Stone’s narrative of progress that masked the specific 1960s developments that made possible their arguments for nonhuman personhood. It also appeared to affirm that previous critiques of liberal humanism could be effortlessly expanded beyond humanity to make nonhumans into persons: humanity would fall as a pertinent moral and legal category, as had the categories of race, gender, and sex. Liberalism, it seemed, could be reworked to make animals and nature into persons.

A person suffers

Such rhetoric of the inevitable unfolding of history had itself a long history in political movements.Footnote 58 Singer, Stone, and other early anti-anthropocentric thinkers adopted this narrative to extend the 1960s expansion of rights and equality to animals and nature. Their straightforward extrapolation from humans to nonhumans, however, obscured the specificity of animals and nature as political beings. The people of color, gay people, and women who had come before nonhumans in the writers’ accounts asserted their personhood through political acts: they provided testimonies of the injustices they had faced, resisted oppression through violence, refused to obey discriminatory laws, and voted for policies they believed represented their interests. Animals and nature could not exercise politics in these ways. They could not, that is, themselves make political claims.

This fundamental problem of what political agency meant for personhood was formulated in Stone’s text as a problem of legal representation. Stone argued that courts could appoint “guardians” to speak for nature as they did for “corporations … states, estates, infants, incompetents, municipalities or universities.”Footnote 59 The guardian would institute legal actions at the “behest” of the natural object, the court would account for “injur[ies]” to the natural object, and relief would run to its “benefit.”Footnote 60 In short, the guardian would represent the natural object to allow it to participate in legal processes as a person.Footnote 61 Stone thus transposed the question of political agency onto the question of communication between the guardian and the nonhuman person. Communication presented no real issue for nature: it was easier for a guardian to discern that a yellowing patch of land required water than for the Attorney General to judge what “the United States” as a person wanted.Footnote 62

Stone depicted guardianship as a legal mechanism that could give nonhumans access to law. But this maneuver hinted at a far more profound problem: how could liberal politics account for voiceless victims unable to make political claims themselves? The very idea of political agency would have to be rethought. Stone’s turn to guardianship displaced this challenge onto a question of communication between the nonhuman victim and the human guardian. It did not fundamentally address how nonhumans remained unable to exercise political agency under guardianship; if mechanisms of political claim-making could not be changed to accommodate nonhumans, then it was the relationship between personhood and political agency that had to be transformed. Personhood had to be rethought because political agency, in fact, could not be.

Writers elided this specific political conundrum raised by nonhuman personhood through their determinist narrative of expanding rights and equality. But the demands made by voiceless victims on liberal politics were grasped precisely at this time by those concerned with another “borderline” person: the fetus. As Stone noted in passing, when “Should Trees Have Standing?” was going to press, a lawyer had petitioned the New York Supreme Court to appoint him legal guardian for an unrelated fetus scheduled for abortion so that he could bring a class action lawsuit on behalf of all such fetuses in New York City’s eighteen municipal hospitals.Footnote 63 Fetuses’ inability to make political claims necessitated a guardian to speak for them. Their vulnerability to other’s political acts made the mother—in Stone’s words, the “traditionally recognized guardian”—into a problem for law to circumvent.Footnote 64 In 1973 the Supreme Court ruled in Roe v. Wade that a fetus is not a person under the Fourteenth Amendment. But in an influential comment criticizing the court’s reasoning, legal scholar John Ely argued that while in recent years the court had sought to protect vulnerable minorities, disproving fetal personhood did not solve the problem of political powerlessness: “Compared with men, very few women sit in our legislatures … But no fetuses [do].”Footnote 65 Roe did not address the question of what political agency meant for those unable to participate actively in politics. Despite their depiction of nonhuman personhood as an inevitable next step after human personhood, the writers trying to unravel the anthropocentrism at the heart of liberalism were also faced with this challenge. How could liberalism become non-anthropocentric when the very structures and mechanisms of its politics were open only to human actors?

Stone, Singer, Tribe, and Regan, through different philosophical and legal routes, converged on one answer: the recognition of animals’ and nature’s suffering.Footnote 66 If nonhumans could not access liberal politics, a non-anthropocentric conception of personhood would need to be undergirded by what nonhumans did have access to. Leaving unaddressed the problem of political agency, they repeatedly asserted that nonhumans deserved moral and legal recognition because of their ability to suffer. And they reduced this ability to the passive capacity to feel physical pain, slipping interchangeably between the two.Footnote 67 Singer, of course, worked within utilitarianism, where the capacity to suffer was the sole requisite for considering a being’s interests. Because animals feel pain as humans do, they deserve equal moral consideration.Footnote 68 Regan also made pain an important component of his argument. Animals, like humans, have the right to be spared undeserving pain, since there are no discernible criteria separating humans from animals that would accord that right to the former but not the latter. In particular, there was no reason to believe that animals do not feel pain, “especially in view of the close physiological resemblances that often exist between them and us.”Footnote 69 Both writers marshaled extensive scientific and philosophical evidence of animals’ physical ability to experience pain to justify the moral recognition of animals.

Even Stone and Tribe, writing more about the environment than about animals, highlighted nonhumans’ ability to suffer. In asserting that natural objects were persons in their own right, Stone emphasized that they themselves could be injured—irrespective of the humans potentially using them. “[T]he death of eagles and inedible crabs, the suffering of sea lions, the loss from the face of the earth of species of commercially valueless birds, the disappearance of a wilderness area,” were injuries to nature itself, distinct from damages to humans. And this suffering had a physical basis: who is to say that plants could not feel pain? Stone cited “experiments on plant sensitivity” and philosophy of mind to contend that it was hard to “dismiss the idea of ‘lower’ life having consciousness and feeling pain,” especially since pain was difficult to evaluate even with other humans.Footnote 70 Humans cannot even readily determine whether other humans are actually experiencing pain. How different was it to acknowledge pain in plants as well?Footnote 71 Law, in fact, could apply similar reasoning in both cases. Decision makers had increasingly taken human pain and suffering into account when calculating damages and could do the same for environmental losses: they could conceivably “factor in costs such as the pain and suffering of animals and other sentient natural objects.”Footnote 72 As humans could no better comprehend the pain of other humans than they could that of natural objects, suffering itself could be thought of as a legal fiction. By recognizing that nonhumans experience pain, courts could make humans see that animals, trees, and perhaps even lakes suffer in their own ways, even if their suffering is incomprehensible to humans. The legal acknowledgment that nonhumans could suffer was enough.

Tribe was particularly invested in the social effects of technologies that “modif[ied] what it means to be human”: electro-chemical behavior alteration and genetic manipulation operated on humans directly and threatened their selfhood.Footnote 73 His turn against anthropocentrism was thus accompanied by the recognition that the environment—like humans with technologies—had interests that could be irreversibly threatened. Nonhumans’ interests could be seen, for instance, in their ability to feel pain. The close resemblance between human and animal pain made it easier for humans to recognize animals’ intrinsic interests: “Torturing a dog evokes a strong sympathetic response; dismembering a frog produces a less acute but still unambiguous image of pain; even pulling the wings off a fly may cause a sympathetic twinge; but who would flinch at exterminating a colony of protozoa?”Footnote 74 Yet recognizing the interests of protozoa was not a lost cause. Every form of life, including protozoa and even plants, shares fundamental needs with humans: water, oxygen, nutrition. With this commonality, humans could understand what it means for trees, for instance, to suffer from lack of water, especially as they produce electrical and chemical signals that are “functionally analogous to pain.”Footnote 75 Like the other writers, Tribe denounced anthropocentrism by highlighting nonhumans’ ability to suffer while narrowing it to the passive experience of pain.

Advocates turned to nonhuman pain as justification for the rejection of anthropocentrism precisely at a time when what it meant to be human was increasingly linked to suffering. With 1960s rights and liberation movements, political action demonstrated and enacted one’s personhood. But as these collective forms of humanist politics, particularly anticolonialism and socialism, went into crisis in the late 1960s, the human person came to be associated less with political agency than with suffering wrought by state oppression—an association that the nascent human rights movement was bringing to public attention in the early 1970s.Footnote 76 Singer detailed in the two most influential chapters of Animal Liberation how establishments such as scientific laboratories and factory farms normalized systemic torture of innocent animals, akin to state violence against humans.Footnote 77 Similarities between powerful institutions’ perpetuation of human and nonhuman suffering were hard to miss: animal rights activists protesting in the wake of Singer’s pronouncements drew on contemporary human rights tropes of suffering, comparing laboratory animals to the Latin American “disappeared” and the tortured dissidents in Amnesty International campaigns.Footnote 78 Thus, as human rights activists started to shift conceptions of oppressed humans from acting to suffering persons, thinkers circumvented the problem of political agency for voiceless victims by highlighting nonhumans’ ability to suffer—an ability they shared with humans. While keeping political agency under liberalism unchanged, they refigured personhood by drawing on shifts in humanist politics. If 1960s movements had destabilized the autonomy and universalism of the liberal human person to allow writers to reject anthropocentrism, the emerging human rights movement in the early 1970s enabled them to reconstitute this person in a non-anthropocentric way through concern with suffering.

Empathy moves history

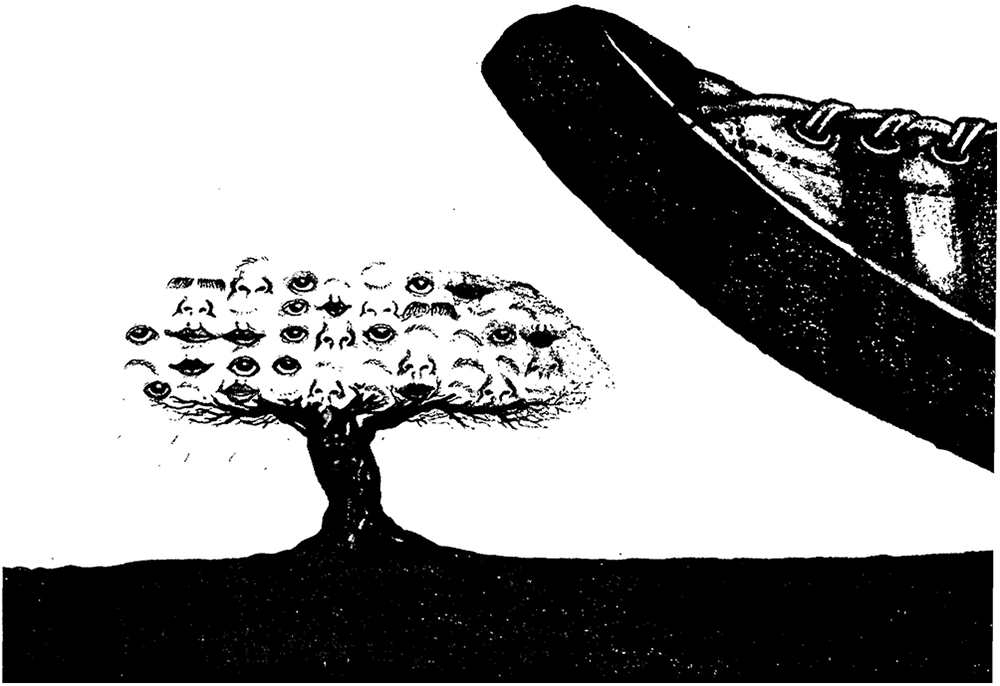

Thinkers’ evocation of suffering not only provided a non-anthropocentric basis for personhood but also reworked the relationship between existing persons and those not yet recognized as persons. For the rejection of anthropocentrism from within liberalism required personhood to be ratified by those whose moral and legal status was already secure. Faced with nonhumans who could not assert their own personhood, thinkers formulated this need for intersubjective recognition into a problem of empathetic identification. Humans would make animals and nature into persons by empathizing with their suffering. As Tribe wrote, an appreciation of nonhuman pain establishes “the bases for empathy” for humans to understand the needs of other life forms.Footnote 79 For instance, the terminology of the recently passed Federal Laboratory Animal Welfare Act (1970) “anthropomorphiz[ed]” animal interests to “subliminally [reinforce] our sympathy for the plight of mistreated animals by evoking images of human suffering.”Footnote 80 By recognizing a shared ability to suffer, humans could see themselves in animals and nature and therefore acknowledge them as persons too (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Nonhuman personhood required humans to see themselves in nonhumans. Christopher D. Stone, “Trees Grow Tall but They Don’t Have Standing,” Barrister 2 (1975), 58–63, 68–70, at 61.

This evocation of empathy underscored that suffering cut across anthropocentric distinctions between humans and nonhumans to unite them. In 1972, Singer had published an influential article on famines in Bengal, which argued that geographical distance was morally irrelevant. People in affluent countries were morally obligated to relieve far-away suffering by donating to hunger relief.Footnote 81 With animals, he additionally rejected the relevance of the species boundary—across past and present—to argue that suffering could not be restricted to humans, whether it be hunger or physical pain. And Stone, drawing on the suffering caused by the Vietnam War, contended that it had led humans to understand that they were connected to beings unlike themselves: the tremendous popularity of the antiwar slogan “War is not healthy for children and other living things” exemplified people’s awareness that nonhumans could suffer too.Footnote 82 Since the eighteenth century, humanitarians had used suffering to rouse pity for the poor, the wounded, the tortured, and the enslaved; the recognition of their suffering exemplified the liberal ideal of being able to project oneself onto others while maintaining one’s status as a disinterested observer.Footnote 83 But the writers’ call for empathetic identification with nonhumans unable to make political claims sought to dissolve the distinction between oneself and others on the basis of shared suffering. Anti-anthropocentric thinkers thus made suffering into a synecdoche of the human, using it to establish a “common humanity” with which humans could identify without evoking humanity as such.

This assertion of empathetic identification across the boundary of humanity foregrounded a reciprocal relationship between existing persons and those not yet recognized as such. Protection of animals and nature had served to solidify anthropocentric hierarchies since the nineteenth century. Animal protectionists used the alleviation of animal suffering as a marker of their humanity against “dumb brutes”; conservationists protected big game and wild habitats to affirm their hold over nature and their “civilization” over others they saw as exploiting it.Footnote 84 The acknowledgment that nonhumans were worthy of personhood because they were like humans replaced this hierarchical differentiation with a relationship founded on mutuality. Recognition of shared suffering not only made persons of animals and nature but also made new moral selves of human persons. As Tribe put it, “new possibilities for respect and new grounds for community elevate both master and slave simultaneously … the oppressor is among the first to be liberated when he lifts the yoke.”Footnote 85 Singer argued that liberating animals would also liberate humans, proving “our capacity for genuine altruism.”Footnote 86 Humans’ empathetic identification with nonhumans both elevated the status of the oppressed and increased the moral sensitivity of oppressors. The anti-anthropocentric evocation of suffering thus underscored how perpetrators and victims were mutually implicated in a relationship of exploitation; humans’ inability to recognize nonhuman suffering limited their moral capacity to empathize with those with which they shared a common bond.

Anti-anthropocentric writers’ emphasis on the mutual implication between victims and perpetrators came after the belated acknowledgment of Holocaust memory in the 1960s, when contestation over the moral and legal culpability of civilians, bureaucrats, and other victims of Nazi violence in the genocide of European Jewry began to challenge clear distinctions between victims, bystanders, and perpetrators of mass violence. Whole populations—not just state and individual actors—became implicated in the perpetuation of suffering.Footnote 87 As this delayed recognition made the Holocaust increasingly paradigmatic of genocide, writers began drawing on it to make analogies between forms of violence. According to Singer, the ignorance of meat-eating consumers was like “the attitudes of ‘decent Germans’ to the death camps.”Footnote 88 In both cases, those with relatively privileged access to politics perpetuated violence against helpless victims even without intending to. And recognition of one’s implication also implied that one had responsibility to end it; vegetarianism, he asserted, was akin to the boycott of the South African apartheid regime.Footnote 89 Regan, even more provocatively, analogized anthropocentric humans to perpetrators of genocide by citing a novel that declared that “the ruthlessness, the insensitivity, the … smugness with which man inflicts untold pain and deprivation on his fellow animals” resembles “the Nazi in his treatment of the Jew.”Footnote 90 In analogizing between the perpetuation of violence, they also analogized between victims of violence across drastically different contexts. Singer repeatedly compared animal suffering to slave suffering.Footnote 91 And the comparison between the Holocaust and treatment of nonhumans implied that animals were like Jews in suffering from overwhelming systemic violence, replicating anti-Semitic tropes denigrating Jews as less than human. In highlighting suffering as that which is shared between vulnerable victims across time, space, and the boundary of humanity, writers thus abstracted suffering to underscore its ubiquity rather than its specificity. They melded nonhumans’ ability to feel pain with humans’ experiences of slavery, genocide, apartheid, and war. Suffering, wrenched from its historical contexts, transcended humanity.

Within this framework of mass violence that implicated the oppressors with the oppressed, empathy for the suffering of animals and nature thus sought to provoke the moral development of a humanity that perpetuated suffering. Advocates’ apparent emphasis on reciprocity between oppressors and the oppressed was actually one-sided. Nonhuman victims, excluded from making political claims, never changed. Humans were the ones who had to identify with themselves in nonhumans to enlarge their empathy. Writers’ extension of personhood across the boundary of humanity in fact indexed the growing morality of existing human persons. Stone, for instance, opened his article by citing Darwin’s Descent of Man, which had demonstrated that “the history of man’s moral development has been a continual extension in the objects of his ‘social instincts and sympathies.’” The “very narrow circle” around man that defined his moral consideration grew wider over time.Footnote 92 Singer later argued against a sociobiological understanding of altruism to assert that moral progress—defined by the “expanding circle” of beings under moral concern—was not biologically determined but spurred by reason. The rational development of morality evolved with the expansion of the “circle of altruism.”Footnote 93 And while Stone and Singer used the widening of circles to illustrate the continuous growth of morality, Tribe reached to spirals to counter the insidious effects of instrumental privileging of ends over means. Society’s understanding of change, incorporating the interactions between means and ends, was itself dynamic and served as an evolving framework that might be thought of as “a multidimensional spiral” along which society moves.Footnote 94 “[T]he human capacity for empathy and identification is not static,” he argued; the very process of “recognizing rights” in beings similar to humans and “with whom we can already empathize could well pave the way for still further extensions as we move upward along the spiral of moral evolution.”Footnote 95 Human morality appeared able to expand indefinitely with the recognition of more and more beings as like humans.

The thinkers’ anti-anthropocentric reworking of the recognition of common humanity into the recognition of shared suffering thus introduced a disjuncture between the sphere of moral and legal concern—that is, of persons, both human and nonhuman—and the sphere of political action, retained on the part of humans. Liberal politics was premised on people’s ability claim personhood, whether through votes, civil disobedience, or court challenges. But by turning to suffering to circumvent liberalism’s problem of political agency for voiceless victims, writers kept political agency within the boundary of humanity while extending personhood past that boundary, with suffering as its new basis. The anti-anthropocentrism of suffering personhood thus preserved within it the humanism of liberal politics. Within this anti-anthropocentric humanism, personhood—untethered from humanity—could extend indefinitely as humans’ moral circles expanded and moral spirals evolved. Humans’ empathy therefore bridged the new chasm that opened up in the early 1970s between the sphere of personhood, defined by suffering, and the sphere of humanity, able to exercise politics. By turning to an incipient 1970s humanism of suffering to place nonhuman personhood into the 1960s humanist challenge of expanding rights and equality, writers constructed empathy as the nexus between existing and future persons, an anthropocentric past and a non-anthropocentric future.

Anti-anthropocentric humanism therefore inverted the relationship between politics and suffering that had characterized older anthropocentric humanism. Oppressed humans excluded from political power had drawn on a common capacity to make political claims to obtain recognition from humans supposedly unimplicated in their suffering. Political action united a humanity divided by suffering. Now, personhood was undergirded by shared suffering while recognition was bestowed by empathetic humans with access to politics. Suffering united a personhood divided by political agency. Pressing against the constraints of liberalism from within, writers rejected the anthropocentrism of liberal personhood but reinscribed the humanism of liberal politics. By maintaining the limitations of the 1960s political agency on which their narratives drew, their elaboration of empathy for voiceless victims in the 1970s cleaved the human who could act politically from the person who could passively suffer. Anti-anthropocentric humanism thus extended and reinforced the very anthropocentrism that advocates sought to negate. Their determinist history obscured the contradiction that preserved, at its center, liberalism’s need to maintain a humanism in its enactment of politics. Thinkers thus dissolved the distinction between humans and nonhumans but reinscribed a more fundamental distinction between those able and those unable to make political claims—a distinction sustained through empathetic identification.

Anti-anthropocentric writers’ attempts to extend critiques of liberalism from the humanist categories of race, gender, and sex to the category of humanity thus reveal the insufficiencies of “expansion” as a narrative for understanding social and political change. When personhood, the very category of critique, is reconstituted to incorporate voiceless victims, the political claim-making previously demonstrative of personhood can no longer be straightforwardly extrapolated. Anti-anthropocentric humanism pried political agency from personhood while relying on their very inextricability to inform a narrative of liberal progress. Thus, while scholars have argued that the 1970s was a period in which suffering was depoliticized in favor of a moral humanitarianism that preserved the political and economic structures perpetuating suffering, they have missed how this shift was consequential for nonhuman politics, therefore also overlooking how the turn to suffering provides new ways of sustaining distinctions between the politically powerful and the vulnerable.

In fact, by instantiating this division between those able and those unable to exercise politics, anti-anthropocentric humanism reinforced such differences within humanity as well. In 1976, proclaiming that society was finally reconsidering its anthropocentrism, Singer and Regan wrote that the US Department of Defense received more letters of protest in 1973 when details of the air force’s proposal to test poisonous gases on two hundred beagles became public than after the bombing of North Vietnam.Footnote 96 Celebrating society’s recognition of nonhuman suffering, they here pitted beagles against civilians. But the comparison perhaps serves less to highlight the quantitative difference between the suffering of the two than to reveal how anti-anthropocentric humanism’s reliance on an abstraction of suffering elides the political agency previously demonstrative of personhood. Nonhuman personhood was constituted through a given conception of humanity defined by suffering—but what does it mean to suffer?Footnote 97 Nonhumans suffered, anti-anthropocentric writers argued, because they could experience physical pain. Postcolonial humans suffered, however, not only because they could feel pain, but also because they remained entangled in a long history of resistance against state actors who deemed them expendable. In turning to suffering to dissolve the division between humans and nonhumans, Singer and Regan reasserted the distinction between empathetic humans able to make political claims and persons unable to, nonhuman and human. By foregrounding the passivity of suffering victims—who required letters of protest on their behalf—they thus elided historical and political distinctions between them. Singer and Regan’s anti-anthropocentric perspective therefore highlights how an emphasis on suffering constitutively effaces political agency even for humans: by understanding the Vietnamese as suffering persons, the writers could not see them as political humans.

Singer and Regan’s abstraction of specific forms of suffering suggests that by establishing personhood—whether human or nonhuman—through empathy with suffering, anti-anthropocentric humanism not only erased the political agency of victims but also elided the historicity of political action. Here, history was not forged by oppressed groups who sought to change their conditions through political acts; rather, it was driven by the growing empathy of the humans whose access to politics was most secure.Footnote 98 In fact, if one traced the moral growth of the empathetic human back through the “spiral of moral evolution” or to the center of the expanding “circle of altruism,” it was the original human person—the white, heterosexual, adult male citizen—who implicitly lay at the center of writers’ accounts of historical change. Stone at times explicitly coded the subject of his text as such. “[O]ur empathy” is being enlarged, he wrote:

We are not only developing the scientific capacity, but we are cultivating the personal capacities within us to recognize more and more the ways in which nature—like the woman, the Black, the Indian and the Alien—is like us (and we will also become more able realistically to define, confront, live with and admire the ways in which we are all different).Footnote 99

“Us” was the original rather than all existing persons.Footnote 100 Always endowed with the power to make political claims, he had made the woman, the Black, the Indian, and the Alien into persons by recognizing the ways he was similar to them.Footnote 101 It was he who made history, cultivating empathy to recognize and create subsequent persons.

Writers’ narratives of personhood naturally extending from humans to nonhumans thus concealed more than the empirical historical conditions of humanist politics in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Their determinist argument obscured how decentering humanity from moral and legal systems concomitantly entailed a reinforcement of the distinction between those able and those unable to make political claims, thus replacing the history forged through political action with the increasing empathy of humans whose political agency is most secure. Perhaps, then, it is worth asking whether this empathy can be better elicited when appeals to suffering suppress, ignore, or supplant political agency in history—for humans, too. It also raises the question whether the active resistance of the oppressed in fact makes humans with political agency less able to empathize with their suffering. With an anti-anthropocentric conception of personhood constituted by passivity in both politics and history, the problem has become one of what specific forms of suffering the humans with political agency can more easily empathize with. Given the increasing invocation of ubiquitous suffering—human and nonhuman—in the face of worsening environmental catastrophes in our present, as well as the disproportionate concentration of suffering among the black, indigenous, and global South communities with precarious access to political claim-making, this question is more urgent than ever.

Acknowledgments

For their help in the preparation of this article, many thanks to Charles Argon, Edward Baring, Angela N. H. Creager, Carolyn J. Dean, Haris Durrani, Stefanos Geroulanos, Hendrik Hartog, Daniel Heller-Roazen, Gabriel Levine, Gabriel Medina, Natasha Wheatley, and Nasser Zakariya. For organizing forums at which earlier drafts of this article were presented, thanks also to Natasha Wheatley and Kim Lane Scheppele, to Bhavani Raman and Daniel Scharfstein, and to Maksymilian Del Mar and Michael Lobban. I am also grateful to the editors and anonymous readers for their generous suggestions.