Introduction

In political theory, Confucianism has emerged as a rival to liberalism and is considered more reflective of East Asian political culture. Confucian political theory has two main camps. Confucian meritocrats seek to limit democracy and its perceived ills,Footnote 1 while Confucian democrats seek to establish some compatibility between Confucianism and democracy or formulate a new hybrid.Footnote 2

Recently, in the academic literature, there is an increasing recognition of the need for Confucian theory to deal with the fact of reasonable pluralism. Since citizens no longer practice classical Confucianism as in ancient China, how might Confucianism be conceived and justified today? This concern has motivated some Confucian theorists to provide a reconstruction of political Confucianism that incorporates some democratic elements. One leading variant is Kim Sungmoon’s pragmatic Confucian democracy,Footnote 3 which embraces democracy in East Asia but sees Confucianism as occupying a special role in justifying the institutional order.

Pragmatic Confucian democracy has been criticized by Li Zhuoyao, who deems it inconsistent to invoke reasonable pluralism but still prioritize Confucianism in accommodating democracy in East Asia: “fully acknowledging reasonable pluralism will cast doubt upon the strategy to prioritize Confucianism over other comprehensive doctrines.”Footnote 4 Since Confucianism is one of many doctrines today, true pluralism must entail liberal neutrality, with a “multivariate” democratic structure.Footnote 5 While both authors disagree on the status of Confucianism, they agree on the value of democracy in East Asian political order.

This article provides a new perspective on this debate by proposing a liberal framework of interjurisdictional competition as an institutional means to deal with the fact of reasonable pluralism in East Asia. This novel option agrees with the need for liberal neutrality but maximizes the scope for competitive experimentation between alternative lifestyles and modes of governance. The institutional manifestation of this position is found not in traditional liberal democracy, but in liberal polycentrism, which accords jurisdictional decentralization to allow for democracy, meritocracy, Confucians, and non-Confucians to simultaneously test out ways of life.

In making this argument, we draw from the epistemic liberal tradition in political theory which stresses the uncentralizability of the ethical knowledge relevant to arbitrating between different cultural identities and the consequent merits of competition as a means of discovery and adaptation. This tradition is best and most recently articulated in Adam TebbleFootnote 6 and includes David Hume, Karl Popper, F. A. Hayek, Michael Polanyi, Chandran Kukathas, and Gerald Gaus. From this perspective, the problem of pluralism is deepened to focus on the epistemic: it is not merely that people in contemporary societies subscribe to diverse doctrines, but that there is no access to a synoptic position from which all the relevant knowledge needed to implement a specific cultural ideal is readily accessible. Just as competitive arrangements are necessary in the economic realm to deal with economic complexity, so competition plays the same role in the cultural realm. Institutional competition is a means for individuals to adapt to ever-changing circumstances in the uncertain cultural landscape and provides what John Gray calls an “enabling device whereby rival and possibly incommensurable conceptions of the good may be implemented and realized without recourse to any collective decision-procedure.”Footnote 7 Accordingly, using terminology from Albert Hirschman, we defend the merits of “exit” as opposed to “voice”Footnote 8 in East Asian governance.

The originality of our contribution is best understood with reference to recent debates between Li and Kim over the implications of pluralism.Footnote 9 Our position overlaps with the former in that it adopts a position of liberal neutrality rather than establishing a special role for Confucianism but is distinct from both in that we extend the challenge of pluralism “all the way down” to the individual. If we take democracy to mean a method of structuring collective choice based on the political equality and participation of the people, then our position is to reduce the scope of this collective choice by expanding the multiplicity of jurisdictions under which communities enjoy self-governance. Such a “libertarian” option is famously espoused in Chandran Kukathas’s “liberal archipelago”Footnote 10 and Gerald Gaus’s “open society.”Footnote 11 This article applies their insights to East Asia, highlighting the value of individual choice in a region which has experienced a history of state paternalism.

Our position may first be contrasted with Kim’s pragmatic Confucian democracy (part of a broader project of public reason). As part of the motivation to enable East Asian citizens to negotiate their newfound democratic status with their traditional Confucian past, a dialogical process of mutual accommodation is necessary for them to eventually embrace democracy on intrinsic, not merely instrumental, grounds. This discursive process is necessary since, according to Kim, the “incongruence between formal democratic political institutions … and ongoing social practices that still define the character of their social life, is a problem.”Footnote 12 Our approach does not necessarily view this as a “problem” to be authoritatively resolved in a public deliberative forum, but rather as a raison d’être for a process of unbounded cultural adaptation. Individuals may come to terms with modernity in divergent ways or reject it by holding onto undemocratic norms. They may legitimately choose not to publicly justify their practices to others and may not even have the linguistic ability to do so anyway, given the often tacit nature of cultural rule-following. Rather than expecting or forging a shared conception of Confucian democratic citizenship, our alternative allows groups to carve out their own small worlds under a liberal polycentric regime.

Traditional democracy requires a higher threshold for successful collective action compared to exit-based arrangements, such as foot-voting within a federal system,Footnote 13 or making choices in the private sector and civil society. Voters need to acquire greater information and possess linguistic resources to exercise effective “voice” and form electoral majorities, amongst others.Footnote 14 The institutional advantage of liberal polycentrism is that it partitions the moral space to allow experiments in living. Not only does this defuse deep disagreement over values, it lowers the threshold for cultural minorities to sustain their way of life in the face of cultural change. Committed Confucians, who may become minorities in the face of cultural change, would have good pragmatic—though not necessarily moral—reasons to support our proposal.

We do not treat pluralism as an intrinsic value to be achieved above all. If some Confucian theorists view pluralism as a moral defect and insist on a hard perfectionist stance, then our argument will fail to convince.Footnote 15 Rather, our argument starts differently: given that people’s cultural identities are ever-evolving, Confucianism, as with any other doctrine, is subject to an open-ended process of cultural adaptation, especially in an increasingly pluralistic world. The question of “what it means to be a Confucian” cannot be assumed to be settled in the first place, and a liberal regime of competitive experimentation is best placed to facilitate an open-ended process of cultural adaptation in contemporary East Asia.

Our article thus recasts the problem of pluralism as a cultural knowledge problem, which is not merely one of managing diverse values, but confronting the deeper challenge of determining what the relevant cultural goods are in the first place—given that knowledge relevant to such questions is not centralizable, but is subject to perspectival diversity, tacit social knowledge, and social complexity. This perspective sees culture as a fluid social construction subject to uncertain evolution, which Li himself alludes to: “what if the progression of society leads to a third possibility where the public character is beyond the Confucian and the Western?”Footnote 16 Our article puts this ongoing social transformation the center of analysis.

The first section, From value pluralism to cultural complexity, explores the epistemic problem in the cultural landscape, which deepens the problem of managing pluralism to one where knowledge of cultural goods is in the first place difficult to centralize. We provide reasons to reject the perfectionist standpoint in favour of liberal neutrality that provides equal liberty to individuals and groups to pursue their values, discover new cultural hybrids, and adapt to ever-changing circumstances. The second section, Cultural adaptation, unbounded, contrasts our position with Kim’s pragmatic Confucian democracy, to highlight the merits of an exit approach to cultural adaptation rather than one of voice. The third section, Epistemic liberalism, competition, and jurisdictional rights, fleshes out our institutional proposal by contrasting liberal polycentrism with democracy.

From value pluralism to cultural complexity: deepening the problem

Theorists concerned about pluralism must in some ways develop their positions in response to empirical facts about the social world and adopt a “nonideal theory” approach. He Baogang advocated an “empirical-based institutional approach to have a primary place in Confucian democracy studies” as without it, an “attractive idea is merely a reflection of wishful thinking.”Footnote 17 It is in this context that Kim develops his pragmatic Confucian democracy and Li responds with his multivariate liberal democracy.

Such an “empirical-based institutional approach” must also deal with the conditions of complexity and uncertainty. Scholars writing in this tradition have advanced the phenomena of “complex adaptive systems” that take shape as a result of non-linear forces of interaction between multiple parts, producing system-level outcomes as these parts adapt to the environment.Footnote 18 Such phenomena exhibit evolutionary change and defy intelligent design, a category which includes culture and the ethical values people hold.Footnote 19 Culture broadly understood comprises the values, customs, traditions that people practice, and which are often not consciously adopted. It is a product of diverse social constructions held by people, and evolve as these constructions are enacted performatively.Footnote 20 A society’s cultural fabric is an emergent byproduct of this evolutionary process of social interaction that is often unknown to the individuals subject to it. Confucianism as a textual tradition and a civic culture, with its associated social rituals, falls under this understanding.

Scholars in the epistemic liberal tradition have stressed the “knowledge problem” and the institutional implications arising from such an attention to complexity. The early emphasis was in the economic realm, where it was emphasized that the knowledge relevant to socio-economic coordination in complex societies is for various reasons uncentralizable and can never be given and accessible in its entirety to a single actor.Footnote 21 Analogously, in the cultural realm, as Tebble observes, the “ethical knowledge relevant to arbitrating between differing and sometimes conflicting identities and conceptions of the good, as well as the specific rules, conventions and practices that constitute then, is never given in its totality in directly accessible form.”Footnote 22 Just as it would be futile to speak of an economic equilibrium point, it is similarly so to ascertain a cultural equilibrium point from which to derive the appropriate rules that authentically reflect a society’s deeply held cultural values. The “cultural knowledge problem” is understood as the sum of three problems: subjective interpretation, social complexity, and tacit social knowledge.

Subjective interpretation of values

Confucians might take certain moral truths to exist objectively, and to be objectively good for all mankind, but an epistemic problem still exists in so far as these principles need to be interpreted. In a world of perspectival diversity, where individuals have different cultural heritages, mental models, and experiences, moral principles that seem self-evident to some may be interpreted differently by others. The existence of perspectival diversity does not imply ethical subjectivism but stems from cognitive differences and the different mental categories used to navigate the complex world.Footnote 23 Perspectival diversity is not just that people disagree on values—how they categorize the problem in the first place is subject to cognitive divergence. Cultural diversity is compounded by cognitive diversity.

Cultural diversity in East Asia is clear. Its history shows rival traditions interacting in complex ways, with some being more prominent in one period than others. To single out Confucianism to characterize East Asia runs the risk of accentuating Confucianism or its variants at the expense of rival traditions which are no less influential. In modern Japan, for example, Shinto rituals and Christian elements are gaining popularity relative to Confucian ones. Religious Japanese readily identify with Shinto and Buddhist traditions instead of Confucianism, suggesting that Confucianism has lost its dominance as the source of social morality.Footnote 24 Buddhism is another influential system of thought that is often overlooked in East Asian discourse. As opposed to classical Confucianism, Buddhism teaches the importance of individual liberty for self-actualization and enlightenment. Buddhism and democracy are “rooted in a common understanding of the equality and potential of every individual.”Footnote 25 The cultural landscape of East Asia is much more diverse than what Confucianists will have us believe, a problem compounded by perspectival diversity.

Even with reference to the same set of classical texts, the need for substantial interpretation means that a common understanding of Confucianism is frustrated. This arises naturally from perspectival diversity, rendering many theoretical conflicts between Confucian scholars unresolved over the years. Even if one subscribes to a set of objective principles, interpretation must be filtered through diverse mental models. Consequently, the attendant social rules, practices, and institutions that are thought to best cohere with these principles are not clearly derivable. The legalist Han Feizi commented about doctrinal schisms, where after the deaths of Confucius and Mencius, “the Confucian school has split into eight factions, and the Mo-ist school into three. Their doctrines and practices are different or even contradictory, and yet each claims to represent the true teaching of Confucius and Mo Tzu.”Footnote 26 Even if, for the sake of argument, Confucianism is held to be an “objective good” by all members of society, and even assuming the unlikely existence of cultural homogeneity, there remains the independent problem of adjudicating between these rival interpretations.

Social complexity

Social phenomena are often multidimensional, and so it is difficult to identify specific levers that may be pulled to shape social outcomes. Therefore, efforts to translate specific cultural values into political life are subject to radical uncertainty. Once again, this is not to imply ethical subjectivism but is to say that, in a world of complexity, the successful translation of principles into outcomes is far from certain. Some sociologists have explored the idea of “family complexity,” where the shape, form, and function of families are highly diverse, arising from unprecedented and recent social trends.Footnote 27 This complexity results in what Judith Seltzer calls the “family uncertainty principle” where social scientists struggle to even define what a family is in a sea of change.Footnote 28

The problem of complexity frustrates the aim of maintaining a specific understanding of the family. The family, just like other social phenomena such as language, has undergone tremendous evolution over the years and exhibits a degree of diversity that is not easily subject to policy control. Admittedly, most modern Confucian scholars are not trying to revive and enforce the family structure in ancient China. But social institutions which are subject to ongoing transformations exhibit a highly fluid quality, rendering it almost impossible to maintain a “Confucian public character” any more than the Académie française can maintain an antiquated purity of the French language.

The family in East Asia has been radically transformed from its formerly patriarchal nature, owing to forces which are non-linear, unforeseen, and which interact in complex ways. That historic China used to preside over a version of the family governed by a rigid hierarchical pattern is well-known.Footnote 29 Patriarchal and patrilineal principles, derived from classic Confucian texts, define the primary social role of the wife. As Susan Greenhalgh notes, “traditional Confucian China and its cultural offshoots, Japan and Korea, evolved some of the most patriarchal family systems that ever existed.”Footnote 30 However, owing to the forces of modernization which open the cultural landscape to unprecedented social forces, such a view has been revised, especially in the past few decades. A big contributing factor was the Second Demographic Transition (SDT) which saw the rise of delayed marriages and decline in fertility rates.Footnote 31 The sharp rise in one-person households from 5 percent in the 1990s to 15 percent in 2010 is a natural consequence of these demographic changes and socio-economic development.Footnote 32 This proliferation of one-person households upset the initial expectations of scholars, who thought that such changes would not take place in traditional societies like China with an entrenched extended family system.Footnote 33

Once society becomes subject to ongoing social transformation, its cultural norms and attendant practices get revised in unforeseen ways that frustrate a “predict and control” model of public policy. The SDT was only one of the disparate factors that shaped Chinese demographics. While it takes self-actualization among adults as the primary motivation behind the decline in marriage and fertility rates, attitudes toward children in marriages in modern China remain relatively conservative. Despite delayed marriages, marriage remained near-universal and relatively early compared to other East Asian countries, demonstrating the persistent primacy of starting a family.Footnote 34 That China did not respond in the same way as other East Asian societies under the same conditions of the SDT suggests that local particularities can refract universal social trends in diverse ways. Local norms, ethnic traditions, religious practices, and migration are all factors that account for family formation preferences across modern China.Footnote 35 As relevant as the SDT is, it alone cannot account for the emergence of new family structures in China. Macro-level institutions, micro-level economic calculus, and cultural explanations are all necessary but insufficient by themselves to explain the changes behind family structures.Footnote 36

Complexity theorists have stressed the dynamic environment in which non-linear interaction effects can give rise to novel cultural hybrids. This is operative in contemporary China, where its traditional practices have confronted the forces of modernization. Ji Yingchun studied the “ongoing, complex, institutional and cultural reconfiguration of Chinese society” and documented how seemingly contradictory forces of tradition and modernity (arising from China’s transition from socialism) interacted to create a “mosaic familism,” a hybrid distinct from the Western family and the traditional patriarchal variant in Confucianism.Footnote 37 Economic transition, according to this perspective, created uncertainties and thus reinforced the family as a site of socio-economic support. On one hand, this reinforces traditional familial ties, but on the other, this new environment sees women taking a greater role in caring for children, thus contributing to a weakening of patriarchal norms and strengthening of matrilineal practices. This is not a straightforward story of women’s empowerment, since women are now expected to take on extra burdens, a sacrifice legitimized by the language of personal choice. Parent–child relationships are also transformed: while traditional Confucian notions of filial piety remain strong, there is now a greater “symbiosis” between parents and children since both are now more financially dependent on each other in an increasingly marketized society. Song Jing and Ji Yingchun have pointed out that a “mix of individualistic values and familism” is now “underlying diverse living arrangements and life plans” in contemporary China.Footnote 38 Overall, the family “is not a unitary actor but contains flexible relationships that are continuously negotiated, maintained, or dissolved, in which men and women seek their individualistic and family-oriented goals and practice their gender role expectations adaptively.”Footnote 39

Clearly, cultural patterns cannot be said to follow a linear trajectory and exhibit much more mutability than is commonly depicted. Arguments aiming to preserve the cultural character of a society do not appreciate the manner in which social institutions like the family arise from a complex social evolutionary process whose details are unknowable in advance.

The tacit dimension

Scholars writing in the epistemic liberal tradition have emphasized how much of the knowledge exercised by humans is tacit, inarticulate, and not amenable to explicit or linguistic expression.Footnote 40 At the same time, many of the social rules and institutions we inherit embody such tacit knowledge and act as navigational guideposts in a complex world where we interact with unknown others.Footnote 41 Crucially, these social rules are culturally transmitted across time through a process of learning and imitation. For our purposes therefore, Confucian principles—to the extent they are held by contemporary individuals—are reflected in the norms, practices, and customs unconsciously inherited, rather than as principles subject to conscious choice. The tacit nature of such norms frustrates attempts to consciously articulate what the cultural character of a society is or ought to be.

Society’s cultural knowledge and its associated rules morph over time as adherents adapt to ever-changing circumstances. This process of evolution and the form that cultural institutions take are the result of human action but not human design, i.e., spontaneous order.Footnote 42 This insight suggests that our contemporary understanding of “Confucianism” is situated within a larger cultural mosaic of which one has no synoptic view. Confucian traditions—what Kim calls “habits of the heart”Footnote 43—are transmitted not by conscious reflection, but unconsciously as one imitates and tacitly reproduces the rituals, customs, and practices that make up the tradition. Social practices are often reproduced by individuals who may be unaware of what they are reproducing. There is no Archimedean point one can reach to determine the cultural character of the society he is a part of. We cannot use our “spectacles to scrutinize [our] own spectacles”.Footnote 44 Any determination of the cultural appropriateness of social institutions—or that a set of institutional arrangements reflect a “Confucian public character” or otherwise—is necessarily partial.

The complex adaptive process that cultural traditions are subject to compounds the complexity of the cultural landscape one is situated in. The seminal work of Gilbert Rozman stresses that “over many centuries the regional tradition (of East Asia) interacted with distinct national traditions and responded to changing societies,” and that “it has combined with imported traditions and has been transformed by modernising societies.”Footnote 45 This interaction process means that Japanese Confucianism, for instance, took on a different character, blending idiosyncratically with Buddhism, Shintoism, and folk practices. On a broader level, across East Asian nations and even within them, a single tradition of “Confucianism” was refracted through national and sub-national lenses, giving way to diverse and ever-changing applications. Recent empirical studies have shown that, although Confucian values in the private sphere have remained popular in East Asia, the level of attachment to values in the political sphere varies wildly between the East Asian states.Footnote 46 Confucian values have often also been intermingling with democratic values.Footnote 47 The complex amalgamations of Confucianism and borrowed traditions create a cultural knowledge problem of ascertaining where it starts and ends. Therefore, as Rozman contends, trying to “isolate Confucian teachings from other influences on social relations faces an obstacle not found when analysing societies in the West and the North,” because in East Asia, “Confucian principles often became part of an eclectic approach to life, not easily dissociated from the other intellectual influences.”Footnote 48

Taking all three aspects together, the problem of the uncentralizability of cultural knowledge in a complex landscape leads us to reject state perfectionism on the basis of a specific cultural goal. To do so reduces the complexity of the cultural tradition in question, whether Confucianism or otherwise, and the fluid mutations they have undergone over time and space. In the context of East Asia, our position therefore generally militates against Confucian perfectionism.

Our argument does not deny that the maintenance of a cultural community is a valued objective. Rather, the error is in seeking to politically establish rules that correspond to a specific cultural tradition, when the knowledge pertaining to cultural matters is precisely what must first be discovered. The same way that the economic knowledge problem frustrates attempts to identify and actualize an economic ideal, the cultural variant of the problem means that one is unable to ground a political order on a specific cultural ideal without doing injustice to the inherent fluidity of culture. To do so would be at best a speculative abridgement of an ever-transforming phenomenon, since this assumes that one can stand above and evaluate the very process of social evolution he is subject to. At worst, it licences state paternalism on the basis that elites claim to know “what Confucianism is” and how society is to be correspondingly engineered. The authoritarian past of East Asia, with the fact that political elites like Lee Kuan Yew have precisely engaged in such cultural engineering, suggests that this is a real concern.

Most Confucian political theorists, to the extent that they adhere to some form of perfectionism, are exposed to this criticism, especially those of a more radical nature such as Jiang Qing and Fan Ruiping.Footnote 49 Perfectionism ought to be questioned given that culture is a fluid social construction subject to uncertain evolution in the cultural landscape. This aspect of social change is exacerbated by the fact that the East Asian cultural landscape today is open to diverse sources of cultural influences that have transformed its value system. This poses a knowledge problem that frustrates any attempt to maintain a political order grounded on a specific cultural ideal. A liberal neutral state, though not necessarily a democratic one, affords equal liberty to individuals and groups to pursue their values, discover new cultural hybrids, and adapt to ever-changing circumstances.

Cultural adaptation, unbounded

While our argument militates against cultural perfectionism by the state, it is imperative to acknowledge the diversity of opinions within Confucian political theory. Kim’s pragmatic Confucian democracy is the leading theory, one that is only moderately perfectionist. His position does somewhat recognize cultural fluidity, given that Confucianism for him is a discursive product of citizens reconciling their newly found democratic status with their traditional past. Confucian cultural norms undergo “horizontal” interaction with non-Confucian alternatives, as well as “vertical” interaction with democracy.Footnote 50 The aim—conceived as a political project to navigate East Asia’s post-authoritarian transition—is to produce Confucian democratic citizens who can come to terms with democratic practices without sacrificing their shared heritage.Footnote 51 Our aim in this section is to contrast his voice-based Confucian democracy with our liberal polycentrism and to argue that citizens’ negotiation with modernity is more richly achieved through an exit paradigm.

An important area of contention between Kim and his liberal critics is the extent to which pluralism is taken seriously. Kim grounds Confucian democracy on pragmatic terms “under the circumstances of modern politics marked by pervasive value pluralism and resulting moral conflicts.”Footnote 52 During the later stage of democratic consolidation, citizens accept democracy intrinsically as they engage in mutual accommodation with their Confucian civic culture.Footnote 53 They do so via Confucian public reason, a moderately perfectionistic normative standard that regulates political practice and which even “prevents the East Asian polities from becoming too Western.”Footnote 54 This move has been criticized by Li,Footnote 55 who argues that citizens may come to terms with democracy in myriad ways, without Confucianism holding a special place.

Our contribution to this debate is to emphasize the epistemic complexity of the modern circumstances of politics. Kim’s initial pragmatic move should lead one to recognize both the existence of pluralism and the dynamics of ongoing social change that East Asia is irreversibly exposed to. It is not only that people are increasingly pluralist, but that their values and cultural identities are exposed to interaction effects that create a sum greater than its parts. The reality of ongoing social change is a nonideal theory constraint that renders state perfectionism unrealistic to maintain the cultural character of any society, let alone to “prevent” East Asia from becoming too Western.

While Kim’s pragmatic Confucian democracy does not aim to reshape society according to unchanging Confucian values, he posits the existence of a “Confucian civic culture,” which “despite its internal evolution, is culturally intelligible” to East Asians.Footnote 56 This forms the basis of Confucian public reason being a regulative ideal. The problem for us is that a “civic culture” is not as “intelligible” and easily delineated as one might expect. Like any complex social phenomenon, it is an emergent byproduct of diverse parties negotiating various public rituals, meanings and practices, a process that occurs without respect to clearly demarcated national boundaries. Civic cultures are not contained in hermetically sealed boundaries within which “internal evolution” occurs, but exist in dynamic interaction with outside forces, heightening the likelihood that social transformation revises it beyond recognition.Footnote 57 From our perspective, a regulative ideal grounded on a distinct culture may be sociologically reductionist. Obviously, all models and theories must engage in some abstraction, but to assume away how cultures undergo dynamic self-transformation is to abstract away a defining feature of modern politics.

At the heart of our position is the charge to take nonideal social conditions seriously in political theory. In an early articulation, Kim seems to appeal to objective moral truths with which to judge the cultural character of society. Anticipating the potential for cultural change, he insisted that his position is not built “merely on the evidence of the current public consensus,” but rather on the “objective good” of “Confucian values such as filial piety, respect for elders, ancestor worship, ritual propriety, harmony within the family, and social harmony,” and thus states’ right to (moderately) perfect citizens.Footnote 58 From an epistemic perspective, grounding political order on such objective cultural goods is to presuppose unrealistically that, as Tebble puts it, “the process of complex cultural adaptation, and the underlying cultural knowledge problem that explains its necessity, have come to an end.”Footnote 59

Kim’s latest position has shifted to emphasize the political need to navigate the region’s post-authoritarian transition, rather than objective values. His Confucian democracy is intended as a “political project rather than a mere abstract philosophical idea,” where he is specifically concerned about how East Asian citizens, as part of their post-authoritarian transition, come to grapple with democracy and reconcile it with their traditional past.Footnote 60 In response to the charge that he is engaging in “ideal theory,” Kim clarifies that it is only “ideal” in this limited political sense.Footnote 61 He places great value on the discursive process (an exercise of voice) through which citizens come to negotiate their traditional past and newly acquired democratic status, and to resolve the “deplorable discrepancy” that may exist between both.Footnote 62 The present authors affirm this to be a praiseworthy objective but it may be more richly achieved through exit rather than voice.

The chief distinction of our approach is that rather than “mutual accommodation” occurring within a centralized political forum, where the discrepancy between the traditional past and modernity is resolved authoritatively, we allow individuals to confront social change in radically divergent ways and carve their own small worlds. Some may withdraw from what they see as the hegemonic status of democracy and reassert their traditional identities, for instance through “clan associations.” Others may reject outright Confucian values and traditions. Towards the first group, Kim proposes civic inducement, and against the second, concedes that some assimilation is inescapable as a basic requirement of citizenship.Footnote 63 Yet even such minimal inducements may be a step too far for those who conscientiously object. As Francis Fukuyama observes, if contemporary events have taught anything, it is that identitarian attachments assert themselves with a vengeance and threaten social peace.Footnote 64

A legitimate question is how relevant our normative theory is to the contemporary East Asian context. While one may insist that our liberal individualism is at odds with East Asian sensibilities, the same may be said of public reason, which stems from a worldview that sees debate, deliberation, and discussion as morally superior in politics. Yet there is no reason to suppose this if, in the first place, knowledge about the good is uncertain. The institutional value of our individualist position, by contrast, is made clear when we consider that East Asians have historically had issues of identity collectively decided and authoritatively imposed on them. Despite the formal democratic transition of some East Asian nations, paternalistic and authoritarian values still linger in their informal norms.Footnote 65 A normative theory that helps East Asia navigate its post-authoritarian transition, a goal we share with Kim, should reasonably give weight to individual choice in a region where it has been sorely absent.

Under our liberal polycentrism, groups need not possess the discursive resources to engage in public reason and can adapt to modernity in accordance with their deeply felt commitments. They speak through their actions in their small worlds. As Kukathas observes, “example can speak—and reason—as eloquently as words.”Footnote 66 Kim’s only consideration of this alternative is when he mentions Michael Oakeshott’s “civil association,” which he deems “fantastical.”Footnote 67 That such an exit-based arrangement is not only viable but desirable is the focus of the next section.

Epistemic liberalism, competition, and jurisdictional rights

Given the conditions of ongoing social transformation and the cultural knowledge problem they generate, the appropriate institutional response is one in which individuals and the cultural groups they form have the liberty to try out their diverse values, under a liberal neutral regime that is non-perfectionist. This is justified not with recourse to any moral principle of “autonomy” or “individual rights” but based on an amoral epistemic recognition of the merits of competitive arrangements as an institutional device to arbitrate different cultural commitments and the rules that follow.

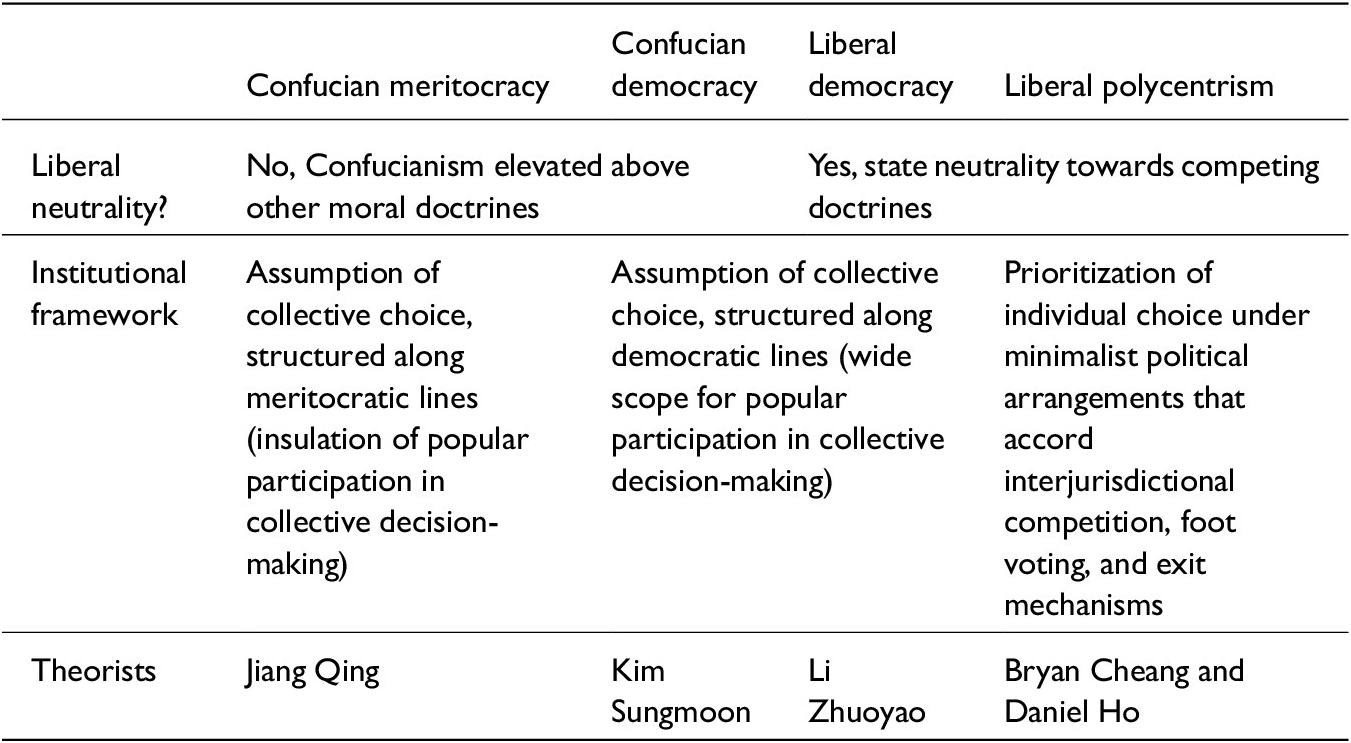

Such a position provides a novel contribution to debates on the institutional implications of pluralism in East Asia, one that breaks the dichotomy between Confucian perfectionism (positions 1 and 2) and liberal democracy (position 3) (see table). The institutional framework we propose, liberal polycentrism, is characterized by jurisdictional competition, a proposal that not only takes the pluralism of values, but also pluralism in governance, seriously.

Liberal polycentrism minimizes the scope of collective decision-making in favor of exit-based political arrangements, where individuals and groups not only pursue their values, but physically enact the cultural rules they favor. Such a framework is liberal in that no specific cultural perspective is prioritized, and polycentric in the sense that individuals are given jurisdictional rights to vote with their feet between multiple alternatives. Typically, such polycentrism is reflected in civil society where people may freely join or leave organizations, in the private marketplace where goods and services are purchased, and in federal systems where individuals move between jurisdictions.Footnote 68 Seen this way, our proposal is concerned not so much with the form of government understood as collective choice, but its scope.

The competitive, exit-based arrangements recommended here are justified on instrumental and epistemic grounds, rather than any adherence to transcendental principles of individual autonomy. In this perspective competition is understood as an institutional procedure of discovery under conditions of uncertainty and one of adaptation to changing circumstances. It is precisely because one cannot centralize knowledge to complex questions that competitive institutions which facilitate discovery are advantageous, analogous to the polycentric competition in science that enables the search for scientific “truth.”Footnote 69 Moreover, cultural groups, when given liberty to act, can better adapt to the ever-changing circumstances in which they find themselves.

In the context of East Asia, polycentric competition provides an institutional framework to better discover answers to complex cultural questions and adapt to new circumstances. One chief value of Confucian political theory is its concern with the cultural alignment of East Asian values and political practices.Footnote 70 It warns that Western practices, if implemented in East Asia, may not authentically reflect local cultural commitments. This important insight must be preserved, but raises the following questions: Which aspects of the Confucian tradition are to be jettisoned, preserved, or revised in light of modernity? What are “Western” and “Eastern” practices in the first place, considering the increasingly hybridized world we live in? Such complexities were highlighted by Gaus, who describes the moral-cultural landscape as a “rugged” one in which it is unclear whether proposed reforms get us close to our ideal or deviate from it since our local approximation of a better society might only be leading us to a local “peak” that, for all we know, might lie further away from our ideal than where we started from.Footnote 71 Consequently, competitive testing between a multiplicity of perspectives helps to better map the institutional terrain and adapt to the evolving cultural landscape.

We do not claim that the cultural knowledge problem precludes the possibility of deliberate attempts at shaping the cultural landscape. Nor do we claim that any such efforts, however modest, are wholly ineffective. Rather, we claim that, owing to the reality of ongoing social transformation and resulting cultural complexity, campaigns of moral suasion should be delegated to lower jurisdictional levels as opposed to the state. Our objection targets the scope and not the mode of governance. Polycentric governance, comprising multiple communities, is quite accommodating of localized forms of cultural influence. A Confucian community may actively engage in education to foster citizens’ moral development while other communities may reject such overt edification. Whether attempts to cultivate particular cultural attitudes succeed on a smaller scale in these communities is of secondary importance. The polycentric approach allows individuals a choice between wildly divergent ways of life and to exit communities that do not align with their values.

Moreover, the emphasis on exit promises to defuse social tensions arising from shallow and deep disagreement. In the present context, shallow disagreements are those over instrumental questions, like “what policies are most effective in preserving filial piety?” Shallow disagreement is reduced because rival claims may be simultaneously tested in multiple decision-centers, compared to a centralized setting. Disagreements might also be rooted in irreconcilable value commitments. With great social heterogeneity in East Asia—what Li considers as “hyperpluralism”Footnote 72—some may fundamentally object to Confucianism. Rather than achieving a convergence toward an overlapping consensus or a shared conception of justice, polycentric governance defuses deep disagreement by partitioning the moral space to allow for experiments in living.Footnote 73 This exit-based approach minimizes the social tensions that will inevitably heighten when opposing visions clash in the fractious political arena.

The example of education is illustrative. Moderate Confucians use various means, short of coercion, to influence cultural adaptation, namely education. But even this seemingly benign proposal begs the question of what values should be propagated. Consider the controversy of whether evolution or creationism is to be taught in public schools. American federalism, being polycentric, helps ameliorate such conflicts. Such zero-sum conflicts are best avoided, considering that, when issues of cultural identity become subject to political decision-making, intergroup conflict is heightened as some extract concessions at others’ expense, and even intragroup conflict is exacerbated as unrepresentative elites claim to speak on behalf of others.Footnote 74 It is thus probably for the better that liberal polycentrism delegates (not forbids) campaigns of moral suasion to lower jurisdictional levels.

Why not democracy?

Our proposal is distinct from traditional liberal democracy and is centred on reorienting the locus of authoritative decision-making away from the state—whatever form it may take—to individuals and the associations they form. Authority over family policy may for instance be devolved to lower jurisdictions or divided over multiple public bodies. Another example is the establishment of new “charter cities” within existing political societies, similar to special economic zones, except in this case these jurisdictions get to experiment even with legal rules.Footnote 75 Such polycentric approaches to governance have historical precedents and are geared toward managing cultural diversity.Footnote 76

Our proposal closely resembles Zhang Xianglong’s advocacy for a “Special District of Confucian Culture” (SDC), an autonomous district protecting the free and independent existence of Confucian lifestyles.Footnote 77 While we are agnostic about people’s personal preferences to live in such isolated communities, the relevance of Zhang’s position is its emphasis on the importance of physically demonstrating (exit), and not just verbally articulating (voice), the viability of alternative lifestyles: whereby this “‘showing’ cannot … be limited to presenting arguments, apologies, or even facts, all of which are subject to interpretations and can be potentially attacked by critics, but instead must demand a real community life that demonstrates how a self-evident and morally glamorous Confucian life-world can actually function.”Footnote 78

The merits of our proposal may be fruitfully contrasted with liberal democracy and political meritocracy on epistemic grounds. Elena Ziliotti criticized the epistemic overconfidence of political meritocrats, and highlighted how it limits the informational inputs needed to make good public decisions. Drawing inspiration from epistemic democrats like David Estlund and Helene Landemore, she makes an epistemic case for Confucian democracy, on the basis that democratic participation contributes to Confucian welfare by harnessing the epistemic diversity of citizens.Footnote 79 However, such a move raises further questions, since democracy itself is subject to its own epistemic problems, including the problem of rational ignorance and elite manipulation.Footnote 80 These problems led Confucian meritocrats to identify Confucian governance as being able to rise above irrational politics.Footnote 81 We agree with Ziliotti’s call for greater epistemic diversity but broaden the range of these knowledge inputs through competitive experimentation.

The challenge we pose to both meritocrats and democrats is the problem of centralization and the epistemic burdens it causes. This problem arises from the singular nature of state-based decision-making, whereby at any given time and regardless of the collective procedure used, only one authoritative decision is implemented, preventing, as Samuel DeCanio points out, “multiple public policies from being simultaneously implemented and compared.”Footnote 82 This problem is heightened in contemporary societies where states, especially in their administrative role, are expected to do too much, raising the specter of expert failure.Footnote 83 The institutional implication, based on a comparative institutional analysis, is to move away from collective choice toward competitive institutional arrangements.

Our position may be contrasted with Li’s “multivariate democracy.” While we share a similar commitment to neutrality, our proposal incorporates greater scope for ethical and institutional change. While Li’s position remains wedded to a Rawlsian “political liberalism” project,Footnote 84 ours works outside it. We reject the need for an “overlapping consensus” characterized by social unity amongst citizens, and question the possibility and desirability of a common standpoint of morality.Footnote 85 If Li’s institutional proposal is “multivariate,” ours may be described as “spatio-temporally variate,” in that institutions and any ethical values that may undergird them experience ongoing transformation. Democratic (or even non-democratic) practices are subject to revision rather than acquiring any permanency in the institutional landscape.

Our emphasis on ongoing social change does not invalidate common rules and norms which enable social cooperation. The international arena is clearly an ordered realm, governed by rules and norms which are the product of emergent interaction rather than any super-state. As Elinor Ostrom demonstrated, these rules and norms are internalized by individuals and groups, a process which over time gives shape to a public realm that then governs them.Footnote 86 Thus any form of stability that arises in liberal polycentrism (and we could expect a certain degree of it) arises as an unintentional byproduct rather than being a feature aimed for in political theory.

A similar proposal is the “liberal archipelago” of Kukathas, a world which allows individuals and groups to freely enter and exit from multiple private communities. This is an account where the emergence of non-monopolistic forms of governance is a real possibility, even though it does not require or explicitly advocate the abolition of the state. In the East Asian context where nation-building efforts are underway to strengthen the state, we do not call for a liberal archipelago. A more suitable alternative is Robert Nozick’s “framework for utopia,”Footnote 87 in which an effective but limited state is accepted as an institutional necessity. Yet we do not ground our case on controversial Kantian ethics, but on an epistemic agnosticism toward values.

A great deal of collective action problems may be resolved in polycentric fashion. This is a theory of public administration that accepts the existence of an overarching set of rules and norms, but identifies possibilities for overlapping multiple decision-centers, including state and non-state bodies, to operate competitively and thus learn from each other.Footnote 88 The relevant academic literature shows that challenging governance dilemmas, even the most acute one of global climate change, may be addressed in such terms.Footnote 89 The precise extent and manner in which such nested and overlapping structures are arranged cannot be stated definitively in complex conditions of uncertainty. Just as the “ideal” market structure is unknown in advance of competitive discovery, so the “ideal” level and manner of polycentricity is subject to change as societies adapt to new conditions.

Why would Confucians favour polycentrism?

The chief attraction of our model to Confucians is that it allows cultural minorities the jurisdictional space to physically realize their values, rather than to negotiate in democratic space. There are high barriers to entry in democratic participation, including the need to win electoral majorities, collectively organize, and mobilize support. This threshold is minimized if groups are given the space to realize their own values without permission from the majority. Thus, as compared to liberal democracy which prizes traditional civil liberties, our proposal emphasizes freedom of action. Such institutional provisions enable groups to create what Gaus calls “small social worlds in which a perspective … can be instituted without negotiation with others, and to a large extent without taking other perspectives into account.”Footnote 90 Granted, democracy can also serve as a forum for values to be transmitted, and for the goals of inclusion to be achieved. But democracy typically prizes linguistic forms of knowledge transmission (debate, political rhetoric, campaigns, etc.) and is comparatively inferior in dealing with the tacit dimension, given that the values and rules we adopt are often not subject to explicit, conscious, or linguistic articulation.Footnote 91 Polycentric governance allows individuals and groups to physically realize their own cultural values in separate domains, without having to rhetorically convince others of their position or engage in any “public reason” whatsoever.

Given that many East Asians today live very cosmopolitan lifestyles, Confucianism may be jettisoned in liberal polycentrism. This possibility in no way uniquely cuts against our proposal. The better question is that, given this possibility, under which institutional framework might committed Confucians best sustain their lifestyles? Insisting on a perfectionist state is unrealistic, for reasons explained above. Under traditional democracy, Confucians will struggle to meet the majoritarian threshold. It is precisely because there is a very real chance of being marginalized in a pluralistic world that we propose polycentric governance as an institutional protection for committed Confucians to enact their preferences rather than having to negotiate the travails of democratic participation. Ironically, it is within our liberal framework that controversial forms of non-liberal governance such as Jiang Qing’s “Way of Humane Authority”Footnote 92 are given the greatest opportunities to be showcased.

Therefore, in liberal polycentrism, there might arise highly isolated Confucian communities (like Zhang’s SDC) run by elders. If citizens already follow very liberal lifestyles, such communities will attract few followers, catering to the few wishing to escape worldly pleasures, no different from isolated Buddhist monasteries already existing. Whether such places will be so closed to the point that those born there see no reason to leave will vary. Currently there will likely be some minimal interface with the outside world given the existence of the cosmopolitan backdrop, with each community deciding on their own terms the proper mix of integration-isolation they prefer.Footnote 93 Given that Confucian communities have historically been largely peaceful, we are cautiously sanguine about their harmonious coexistence in the liberal order.

In a competitive cultural landscape, Confucianism, like any other doctrine, may be at risk of being dissolved. While Confucians may fear this possibility, cultural liberty is not only efficacious in allowing for experimentation between different cultural traditions, but instrumental in generating the knowledge about what is of cultural importance in the first place. Therefore, even though cultural liberty might lead to the dissolution of a specific cultural tradition, it is precisely this sort of a discovery procedure which enabled cultures over history to develop creative ways of remaining relevant in an ever-changing social landscape. Ironically, it is the perfectionist position, by truncating the process within which identities are discovered and developed, that does not do justice to the richness of cultural traditions.

Conclusion

This article advances a new perspective in response to the challenge of pluralism in East Asia. One disagreement is about whether Confucianism should occupy a special place in political society, illustrated by Kim’s moderately perfectionistic Confucian democracy and Li’s insistence on liberal neutrality. On the other hand, scholars who accept a Confucian framework debate the merits of meritocracy or democracy. We stake out a new position by drawing from the tradition of epistemic liberalism. We argue that liberal neutrality is the appropriate response to value pluralism but are agnostic about the ideal mode of collective choice which is to be minimized in favour of allowing various values and rules to compete. It is an anti-perfectionist stance with liberal neutrality, but not one necessarily wedded to democracy. Our proposal transcends both Confucianism perfectionism and liberal democracy.

Liberal neutrality is justified not only because of the facts of pluralism, but because the knowledge of cultural questions is not given and directly accessible, rendering reductionistic attempts to articulate a cultural ideal and maintain the cultural character of a society. To place a specific cultural identity—in this case Confucianism—on a pedestal is to beg the very question that the cultural knowledge problem seeks to solve, which is that identity is constantly being renegotiated and transformed in a world where we interact with others whose circumstances we are unaware of. Ongoing social change subjects any culture to dynamic self-transformation to the point of it being unrecognizable, making it reductionistic to hold it up as a regulative ideal. Moreover, efforts to “prevent the East Asian polities from becoming too Western”Footnote 94 could legitimize state paternalism, antithetical to the very aim of enabling the region to escape the shadow of its authoritarian past.

We have explained why democracy is not necessarily the appropriate response to the cultural knowledge problem that ongoing social transformation creates and have made the case for polycentric governance. Such an exit-based framework is epistemically advantageous compared to both centralized meritocracy and democracy in that it allows individuals and groups not to only defuse the tensions that pluralism poses, but also engage in an open-ended process of adaptation over questions of cultural goods and the requisite modes of governance. Not only is Confucianism deprivileged, even democracy is not accorded special consideration as a form of governance in a world of ongoing social transformation.

Acknowledgements

The lead author Bryan Cheang thanks Paul Lewis, Sam DeCanio, Adam Tebble, Kevin Vallier, and Julian Müller for their constructive comments, as well as those from the anonymous referees. We also thank the Governing Deep Differences project at the Center for Governance and Markets at University of Pittsburgh for support and presentation opportunities.