Introduction

Rumen microbial fermentation from cattle has been identified as a major source of anthropogenic methane emissions and has received increasing attention from a concerned public and ruminant nutritionists alike. Digestive fermentation from cattle is responsible for approximately 27 % of anthropogenic methane emissions (US Environmental Protection Agency, 2022). Methane not only poses an environmental challenge but represents an energetic loss of approximately 2 to 12 % of gross energy intake (Subepang et al., Reference Subepang, Suzuki, Phonbumrung and Sommart2018). For these reasons, there have been continued efforts to identify and develop dietary feed additives, such as synthetic compounds, marine algae and botanical extracts, to mitigate methane emissions from ruminant animals. One of the primary challenges with reducing methane emissions from ruminants is that methanogenesis represents one of the major hydrogen sinks necessary to regenerate reducing equivalents and allowing fermentation to continue (Ungerfeld, Reference Ungerfeld2020). Most anti-methanogenic feed additives work by inhibiting rate-limiting steps of methanogenesis and/or diverting metabolic hydrogen to alternative hydrogen sinks, typically propionate production, making propionate concentration and acetate:propionate ratios appropriate markers of shifts in microbial hydrogen metabolism. Currently, the major compounds that have shown promise for methane reduction include 3-nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP), a synthetic feed additive that inhibits the terminal reaction of microbial methanogenesis, and Asparagopsis taxiformis, a marine algal species known for containing halogenated compounds. The concentration and potential bioactivity of these compounds are known to vary based on length of administration time, yielding potentially inconsistent impacts on methane emissions in practice (Vijn et al., Reference Vijn, Compart, Dutta, Foukis, Hess, Hristov, Kalscheur, Kebreab, Nuzhdin, Price, Sun, Tricarico, Turzillo, Weisbjerg, Yarish and Kurt2020). For example, while 3-NOP is known to reduce enteric methane emissions by as much as 25–35 % (Yu et al., Reference Yu, Beauchemin and Dong2021), its efficacy is significantly reduced after approximately 40 weeks of feeding (Van Gastelen et al., Reference Van Gastelen, Burgers, Dijkstra, De Mol, Muizelaar, Walker and Bannink2024). Similarly, long-term feeding of A. taxoformis has been reported to reduce its efficacy over time, potentially due to development of antimicrobial resistance to bromoform (Indugu et al., Reference Indugu, Narayan, Stefenoni, Hennessy, Vecchiarelli, Bender, Shah, Dai, Garapati, Yarish, Welchez, Räisänen, Wasson, Lage, Melgar, Hristov and Pitta2024). Another consequence of feeding anti-methanogenic feed additives, especially A. taxoformis, is their adverse impacts on fibre digestibility via activity against sensitive fibrolytic bacteria (Hristov et al., Reference Hristov, Melgar, Wasson and Arndt2022). Due to the limitations of 3-NOP and for marine algae, further exploration of other additives with potential to reduce methane emissions is warranted.

Possible alternative compounds for reducing methane emissions include plant secondary metabolites (PSM), which are found in various botanical extracts. Botanical extracts have mixed effects on methane production when fed to cattle (Hristov et al., Reference Hristov, Melgar, Wasson and Arndt2022); however, some varieties are known to be potent methane inhibitors. Kolling et al. (Reference Kolling, Stivanin, Gabbi, Machado, Ferreira, Campos, Tomich, Cunha, Dill, Pereira and Fischer2018) reported a 13.9 % decrease in in vivo methane production per unit of digested dry matter (DM) when feeding a combination of dried oregano plant extract and green tea essential oils. Notably, this reduction occurred without the concomitant reduction in neutral detergent fibre (NDF) digestibility that commonly occurs when feeding other anti-methanogenic feed additives (Hristov et al., Reference Hristov, Melgar, Wasson and Arndt2022). Reductions in methane emissions via botanicals of the magnitude reported by Kolling et al. (Reference Kolling, Stivanin, Gabbi, Machado, Ferreira, Campos, Tomich, Cunha, Dill, Pereira and Fischer2018) are greater than what is commonly reported for more conventional feed additives such as monensin, which typically only reduce methane emissions by ∼5 to 6 % (Marumo et al., Reference Marumo, LaPierre and Van Amburgh2023; Odongo et al., Reference Odongo, Bagg, Vessie, Dick, Or-Rashid, Hook, Gray, Kebreab, France and McBride2007). While the PSM profile of the botanicals used in Kolling et al. (Reference Kolling, Stivanin, Gabbi, Machado, Ferreira, Campos, Tomich, Cunha, Dill, Pereira and Fischer2018) were not described, the essential oil fraction of botanicals are known to be variable. Nurzyńska-Wierdak and Walasek-Janusz (Reference Nurzyńska-Wierdak and Walasek-Janusz2025) reviewed chemical composition data of oregano essential oil from various countries across Europe and the Middle East and reported notable concentrations of the terpenes alpha-pinene, sabinene and beta-caryophyllene. Green tea species are known to be enriched in polyphenols, such as gallic acid and other flavonoids (Afzal et al., Reference Afzal, Safer and Menon2015). Citrus extracts have also been shown to reduce methane intensity from dairy cattle (Khurana et al., Reference Khurana, Brand, Tapio and Bayat2023), which are known to be enriched with apigenin, quercetin, alpha-humulene and nerolidol (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Xu, Gao, Zhang, Yao, Wang, Feng and Wang2023; Martinidou et al., Reference Martinidou, Michailidis, Ziogas, Masuero, Angeli, Moysiadis, Martens, Ganopoulos, Molassiotis and Sarrou2024; Parastar et al., Reference Parastar, Jalali-Heravi, Sereshti and Mani-Varnosfaderani2012). While much of the focus of previous research has centred on botanical extracts from herbal plants, many potentially antimicrobial plant secondary metabolites are abundant in cover crops and perennial grasses and legumes grown in the North America (Clemensen et al., Reference Clemensen, Villalba, Rottinghaus, Lee, Provenza and Reeve2020). The identification of active compounds responsible for strong reductions in methane production could serve to provide new insights into such compounds as feed additives for dairy cattle.

Previous methane mitigation research involving plants has primarily focused on evaluation of whole plant extracts or isolated compounds or chemical fractions such as tannins, saponins and essential oils (Hook et al., Reference Hook, Wright and McBride2010). The impact of pure PSM on rumen fermentation and methanogenesis have not been investigated to the same extent as other plant compounds. Secondary metabolites produced by plants allow for a selective advantage over competitors in response to abiotic and biotic stresses (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Wen, Ruan, Zhao, Wei and Wang2018). In some cases, these compounds can be produced in response to microbial stimuli, suggesting antimicrobial functions. The antimicrobial activity of PSM against common human microbial pathogens has been more extensively characterised in the search for antibiotic drug alternatives (Lelario et al., Reference Lelario, Scrano, De Franchi, Bonomo, Salzano, Milan, Labella and Bufo2018). Given overlap in potential mechanisms, the antimicrobial effects of PSM could be transferable to ruminant microbes and may serve as potentially novel methane-reducing compounds. While previous studies have evaluated methane production when feeding whole plant extracts containing secondary metabolites (Busquet et al., Reference Busquet, Calsamiglia, Ferret and Kamel2006; Oh et al., Reference Oh, Wall, Bravo and Hristov2017), the supplementation of purified compounds is less extensively characterised. Moreover, studying isolated compounds allows us to better understand the specific mechanisms by which these extracts reduce methane emissions. Therefore, the objective of the current study is to evaluate 30 pure secondary plant compounds with known antimicrobial activity for their effects on rumen methane production, NDF digestibility and volatile fatty acid (VFA) profile in vitro. We hypothesise that the addition of these compounds to mixed rumen microbial cultures will reduce methane production without having adverse effects on digestibility.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals and diet

Two cannulated multiparous, mid-lactation Holstein cows from the University of Minnesota Dairy Cattle Teaching and Research Center were used as rumen inoculum donors for this experiment. The University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved use of all animals in the experiment (Protocol #: 2102-38821A). Donor cows were 187 ± 8 days in milk with an average milk yield of 29.6 kg/d and an average dry matter intake of 26.3 kg/d. Donor cows were fed the same basal total mixed ration (TMR) formulated to meet or exceed the requirements of a lactating dairy cow according to NASEM (2021) throughout the experiment (Table 1). The same TMR fed to the donor cows was dried at 55 ℃ for 48 h and ground through a Wiley No. 4 laboratory mill (Thomas Co., Philadelphia, PA) fit with a 1 mm screen to be used as substrate for in vitro fermentation.

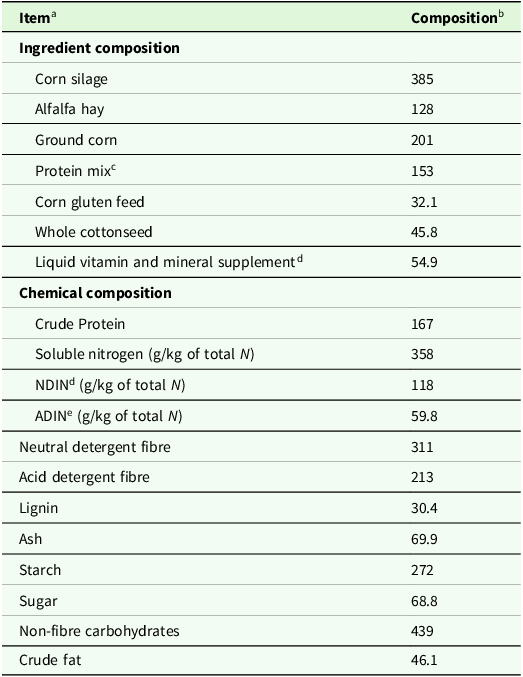

Table 1. Ingredient and chemical composition of basal diet fed to rumen fluid donor cows and used as substrate in batch culture fermentations

a Composition as g/kg of diet dry matter (DM) unless otherwise noted.

b Protein mix composition (DM basis): canola meal, 28 %; soybean meal, 22 %; treated soybean meal, 15 %; distillers dried grains, 13 %; ground corn grain, 5 %; calcium carbonate, 5 %; bloodmeal, 3.5 %; sodium bicarbonate, 3.5 %; potassium carbonate, 3 %; trace minerals, 2 %.

c Supplement composition (DM basis): Ca, 49 g/kg; P, 11.7 g/kg; NaCl 101 g/kg; K, 34 g/kg; Mg, 7.2 g/kg; S, 5.5 g/kg; Mn, 1237 mg/kg; Cu, 382 mg/kg; Se, 8.6 mg/kg; Zn, 1813 mg/kg; Vitamin A, 171 IU/kg; Vitamin D, 34 IU/kg; Vitamin E, 706 IU/kg.

d Neutral detergent insoluble nitrogen.

e Acid detergent insoluble nitrogen.

Pure compound selection and preparations

The compounds evaluated in the current experiment were selected due to their baseline presence in healthy cover crops conducive for forage production in the Great Lakes region of the United States. Briefly, 20 cover crop varieties with known beneficial agronomic and agroecological properties were selected and a literature search for their naturally occurring signature or general PSM in low concentrations during healthy plant conditions was conducted, generating a list of hundreds of PSM. From here, PSM were chosen for evaluation based on commercial availability from chemical suppliers, diversity in chemical structure and previous literature regarding general antimicrobial activity. Analytical-grade pure compounds were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or Indofine (Hillsborough, NJ) and stored according to supplier’s recommendations until time of inoculation. Twenty-five mg of each pure compound was dissolved in 2 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to ensure even solubility and distribution of compounds in flasks. Previous studies (Bonifacino et al., Reference Bonifacino, Rodríguez, Pérez-Ruchel, Repetto, Cerecetto, Cajarville and González2019; O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Myers, Maplesden and Vander Noot1970) have utilised DMSO as a solvent for other feed additives evaluated using batch culture techniques due to its lack of an impact on fermentation. The concentration of 25 mg per g of feed was selected to be in accordance with previous in vitro gas experiments evaluating the effects of similar purified plant-derived extractions (Bhatta et al., Reference Bhatta, Uyeno, Tajima, Takenaka, Yabumoto, Nonaka, Enishi and Kurihara2009; Lila et al., Reference Lila, Mohammed, Kanda, Kamada and Itabashi2003; Tabacco et al., Reference Tabacco, Borreani, Crovetto, Galassi, Colombo and Cavallarin2006).

Experimental design

One gram of the dried, ground TMR was added to a 250 mL inoculation flask with 20 mL of rumen fluid, 80 mL McDougall’s buffer (McDougall, Reference McDougall1948), and 2 mL of DMSO containing 25 mg of dissolved pure compound for all PSM treatments. Rumen fluid was collected from 2 donor cows (∼1 L/cow) into prewarmed thermoses and transported back to the laboratory within 20 min of initial harvest. Contents from both cows were combined in equal parts, mixed and strained through 4 layers of cheesecloth under CO2 to achieve anaerobic conditions prior to addition to flasks. Flasks were placed in a forced air-dry orbital shaking incubator (Max Q 6000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 48 h at 39 °C and swirled continuously at 65 RPM.

The experiment was performed over 8 experimental incubation runs. Each experimental run consisted of two replicates of a blank containing only the rumen fluid-buffer mixture, two control (CTRL) flasks containing 100 ml of rumen fluid-buffer mixture, 2 ml of DMSO and 1 g of feed, and duplicate flasks of eight of the 30 selected PSM, randomly assigned to run. Monensin was included in two randomly selected runs to serve as a positive control as this compound is known to consistently reduce in vitro methane production (Sarmikasoglou et al., Reference Sarmikasoglou, Sumadong, Roesch, Halima, Arriola, Yuting, Jeong, Vyas, Hikita and Watanabe2024). Experimental runs were randomised and duplicated so that each compound appeared in 2 separate experimental runs totalling 4 flasks per compound, with a different combination of compounds evaluated in each run.

Gas production and composition

Inoculation flasks were fitted with ANKOM RF gas pressure analysers (ANKOM Technology, Macedon, NY) to record cumulative gas pressure for 48 h. Total gas production was calculated from gas pressure using the Ideal Gas Law:

PV = nRT, where:

P = pressure in kilopascals,

V = headspace volume in litres,

n = moles of gas produced,

R = gas constant; 8.314 L/kPa/mol

and T = temperature in Kelvin

A 10 mL subsample of headspace gas produced from fermentation flasks was collected from the exhaust port of the gas pressure analyser after 48 h of incubation using a syringe and stored in pre-evacuated gas chromatography (GC) vials (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) prior to analysis of methane concentration using a GC with a flame ionised detector (Agilent 8890, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

VFA concentration and nutrient digestibility

Following 48 h of incubation, the remaining fluid and undigested TMR were placed in 50 mL conical tubes and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min to separate solid and liquid fractions as described by Salfer et al. (Reference Salfer, Fessenden and Stern2020). A 5 mL subsample of the supernatant was collected and frozen at −20 ℃ for analysis of VFA using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy at the Minnesota NMR Center according to Beckonert et al. (Reference Beckonert, Keun, Ebbels, Bundy, Holmes, Lindon and Nicholson2007). Undigested TMR and post-fermentation residues were lyophilised at −50 °C and <133 × 10−3 mBar (FreeZone 18L model # 7755010, Labconco, Kansas City, MO) for the determination of dry matter digestibility. Neutral detergent fibre concentration of lyophilised undigested TMR and residue was determined using an ANKOM A200 fibre analyser with F57 bags (ANKOM Technology, Macedon, NY).

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed as a linear mixed model in R ver. 4.4.3 (https://www.r-project.org/) using the lme4() package that included the fixed effect of treatment, and random effect of experimental run, and responses from the average of the two blank flasks containing only rumen fluid and buffer within each run were included in the model as a covariate. Normality of residuals and homogeneity of variance were assessed visually using normal quantile-quantile plots and plots of residuals versus fitted values. Preplanned pairwise contrasts comparing each treatment to CTRL were performed using Dunnett’s many-to-one adjustment using the contrast() function of the emmeans package of R. Significance was declared as P ≤ 0.05 and tendencies were declared as 0.05 < P ≤ 0.10.

Results

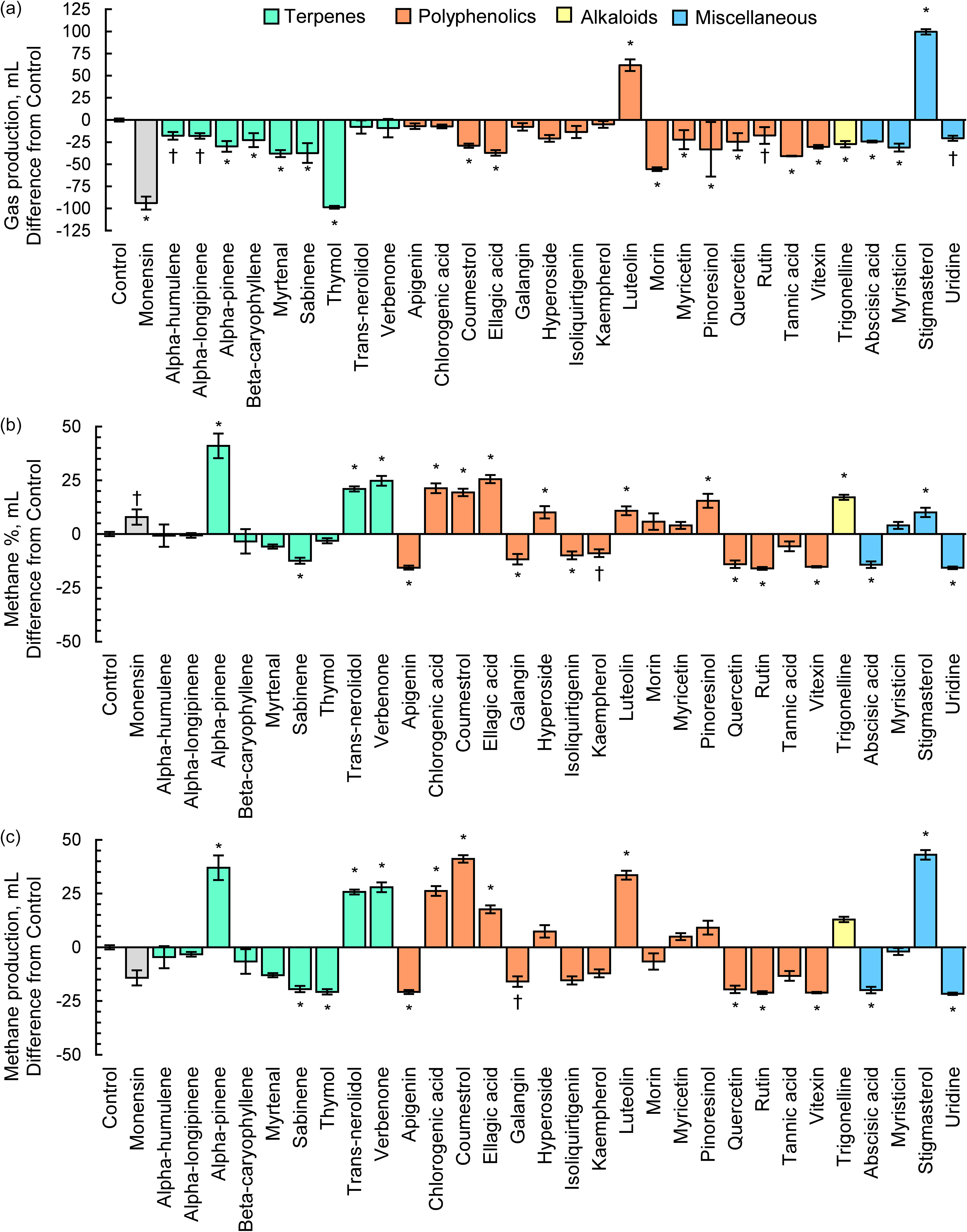

Total gas production

Total gas production for CTRL was 133.4 ± 1.79 mL (mean ± SEM; Figure 1a). Our positive control monensin had a gas production 39.5 ± 7.46. Relative to CTRL, 16 PSM reduced total gas production, and 4 tended to reduce gas production. Terpenes that reduced gas production included thymol (74.0 % decrease; P < 0.01), myrtenal (28.6 %; P < 0.01), sabinene (28.0 %; P < 0.01), alpha-pinene (22.3 %; P < 0.01) and beta-caryophyllene (17.1 %; P < 0.01), with a tendency for reduction by alpha-longipinene (13.5 %; P = 0.07), and alpha-humulene (13.3 %; P = 0.08). The polyphenolics morin (41.7 % decrease; P < 0.01), tannic acid (30.6 %; P < 0.01), ellagic acid (27.9 %; P < 0.01), pinoresinol (24.9 %; P < 0.01), vitexin (22.7 %; P < 0.01); coumestrol (21.7 %; P < 0.01), quercetin (18.5 %; P = 0.04) and myricetin (16.7 %; P = 0.04) reduced gas production, while it tended to be reduced by hyperoside (15.6 %; P = 0.07) and rutin (13.1 %; P = 0.08). The alkaloid trigonelline also reduced gas production by 20.5 % (P < 0.01), as did the plant hormone abscisic acid (18.3 %; P = 0.05) and the allylbenzene myristicin (23.5 %; P < 0.01). Uridine, which is a nucleoside, tended to reduce gas production by 15.4 % (P = 0.07). Increased gas production occurred when cultures were treated with the phytosterol stigmasterol (74.6 % increase; P < 0.01) and the polyphenol luteolin (46.1 %; P < 0.01).

Figure 1. The effects of pure plant secondary metabolites (25 mg compound/g substrate dry matter) on (a) total in vitro gas production, (b) headspace methane concentration and (c) in vitro methane production during 48 h of batch culture rumen fermentation. Data is presented as the difference in LSM between control batch cultures containing substrate but no plant secondary metabolite and each compound, with SEM bars. Treatments that differed (P ≤ 0.05) or tended to differ (0.05 < P < 0.10) from the control according to a Dunnett’s test are denoted with an * or †, respectively.

Headspace methane concentration

Average methane concentration for CTRL was 19.6 ± 1.00 % (Figure 1b). The terpene Sabinine reduced methane concentration by 63.3 % to 7.2 % of total gas (P < 0.01) Furthermore, the polyphenolics rutin (81.5 % decrease), apigenin (79.6 %), vitexin (77.8 %), quercetin (71.6 %) galangin (59.8 %) and isoliquirtigenin (50.7 %) all reduced methane concentration (P ≤ 0.03), while kaempherol tended to reduce it by 45.4 % (P = 0.10). Uridine and abscisic acid and increased methane concentration by 80.0 and 72.9 %, respectively (P < 0.01). Seven compounds increased (P ≤ 0.01) methane concentration including alpha-pinene (67.7 % decrease), ellagic acid (56.7 %) verbenone (55.9 %), chlorogenic acid (52.1 %), trans-nerolidol (51.7 %). coumestrol (49.7 %), trigonelline (46.6 %) pinoresinol (44.2 %), luteolin (35.5 %), hyperoside (34.9 %) and stigmasterol (34.0 %).

Methane production

Average methane production for the control was 25.2 ± 1.36 mL (Figure 1c). Seventeen PSM (abscisic acid, alpha-humulene, alpha-longipinene, apigenin, beta-caryophyllene, galangin, isoliquirtigenin, kaempherol, morin, myrtenal, quercetin, rutin, sabinene, tannic acid, thymol, uridine and vitexin) and monensin numerically reduced methane production by 10 % or more. However, only eight of these treatments were significant (P ≤ 0.01) including uridine (84.0 % decrease), rutin (81.8 %), vitexin (81.7 %), apigenin (80.6 %), thymol (80.5 %), abscisic acid (77.4 %) quercetin (76.1 %) and sabinene (75.4 %). Galangin also tended (P = 0.07) to reduce methane production by 60.9 %. Eight PSM treatments increased methane production (P ≤ 0.02), including stigmasterol (62.4 %), coumestrol (61.3 %), alpha-pinene (58.8 %), luteolin (56.3 %), verbenone (51.8 %), chlorogenic acid (50.2 %), trans-nerolidol (49.7 %) and ellagic acid (40.3 %).

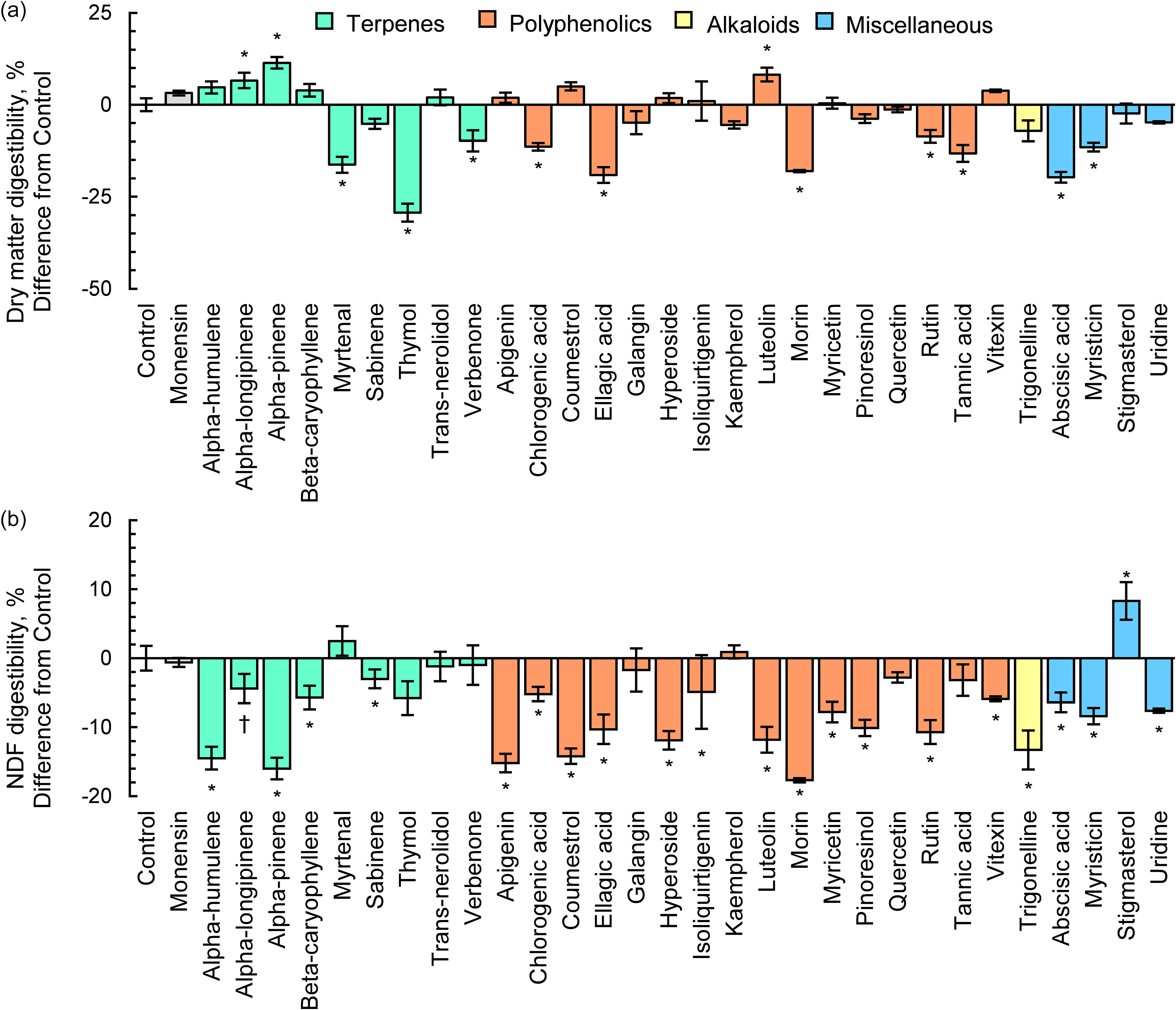

DM digestibility

Average DM digestibility (DMD) for CTRL was 52.3 ± 2.45 % (Figure 2a). Ten PSM including thymol (56 % decrease) abscisic acid (37.7 %), ellagic acid (36.5 %), morin (34.4 %), myrtenal (31.2 %), tannic acid (25.2 %), myristicin (22.0 %), chlorogenic acid (21.8 %), verbenone (18.7 %) and rutin (16.4 %) reduced (P ≤ 0.01) DMD. Alpha-pinene. luteolin and alpha-longipinene and increased DMD by 17.9. 13.6. and 11.2 %, respectively (P ≤ 0.04).

Figure 2. The effects of pure plant secondary metabolites (25 mg compound/g substrate dry matter) on in vitro (a) dry matter and (b) neutral detergent fibre (NDF) digestibility following 48 h of batch culture rumen fermentation. Data is presented as the difference in responses from control batch cultures containing substrate but no plant secondary metabolite. Treatments that differed (P ≤ 0.05) or tended to differ (0.05 < P < 0.10) from the control according to a Dunnett’s test are denoted with an *or †, respectively.

NDF digestibility

Neutral detergent fibre digestibility (NDFD) averaged 51.3 ± 0.40 % for CTRL (Figure 2b). Twenty of 30 PSM reduced NDFD. The terpenes alpha-pinene (31.2 % decrease), alpha-humulene (28.3 %), thymol (11.3 %) and beta-caryophyllene (11.1 %) decreased NDFD (P < 0.01), with alpha-longipinene exhibiting a tendency for decrease (8.6 %; P = 0.07). The polyphenolics including morin (34.5 %), apigenin (29.6 %), coumestrol (27.7 %), hyperoside (23.2 %). luteolin (23.0 %), rutin (20.9 %), ellagic acid (20.1 %), pinoresinol (19.7 %), myricetin (15.2 %), vitexin (11.5 %), chlorogenic acid (10.1 %) and isoliquirtigen (9.6 %) also reduced NDFD (P < 0.03) compared to control. Moreover, NDFD was reduced 25.9 % by trigonelline, 16.4 % by myristicin, 14.8 % by uridine and 12.5 % by absiscic acid. Stigmasterol was the only PSM treatment to increase NDFD and did so by 16.2 % (P < 0.01).

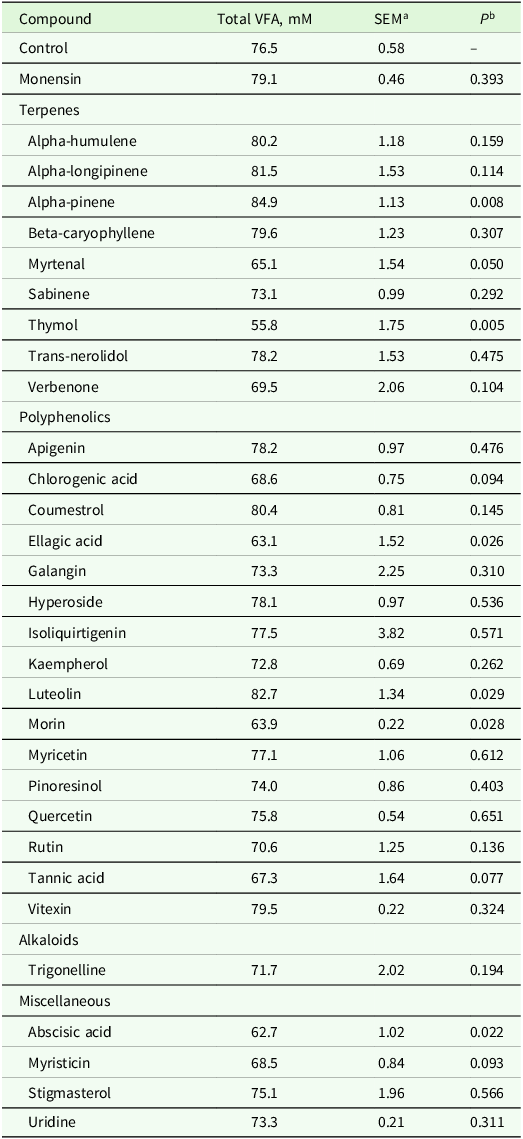

Volatile fatty acids

Volatile fatty acid concentrations averaged 76.5 ± 0.58 mM for CTRL (Table 2). Total VFA concentrations were increased 10.9 % by the terpene alpha-pinene (P = 0.01) and reduced 14.9 and 27.0 % by myrtenal and thymol, respectively (P < 0.05). The polyphenolic luteolin increased VFA concentration 8.1 % (P = 0.03), while VFA concentration was reduced 17.5 % by ellagic acid (P = 0.03) and 16.5 % by morin (P = 0.03). Moreover, tannic acid, chlorogenic acid and verbenone tended to decrease VFA concentration by 12.0 %, 10.3 % and 9.2 %, respectively. Furthermore, abscisic acid reduced VFA concentration by 18.0 % (P = 0.02), and myristicin tended to reduce VFA concentration by 10.5 % (P = 0.09).

Table 2. The effects of pure plant secondary metabolites (25 mg compound/g substrate dry matter) on total volatile fatty acid (VFA) concentration following 48 h of batch culture rumen fermentation

a SEM=Standard error of the mean (n = 4/treatment).

b P-value of the Dunnett’s test comparing each compound to a control containing rumen fluid, buffer and feed substrate.

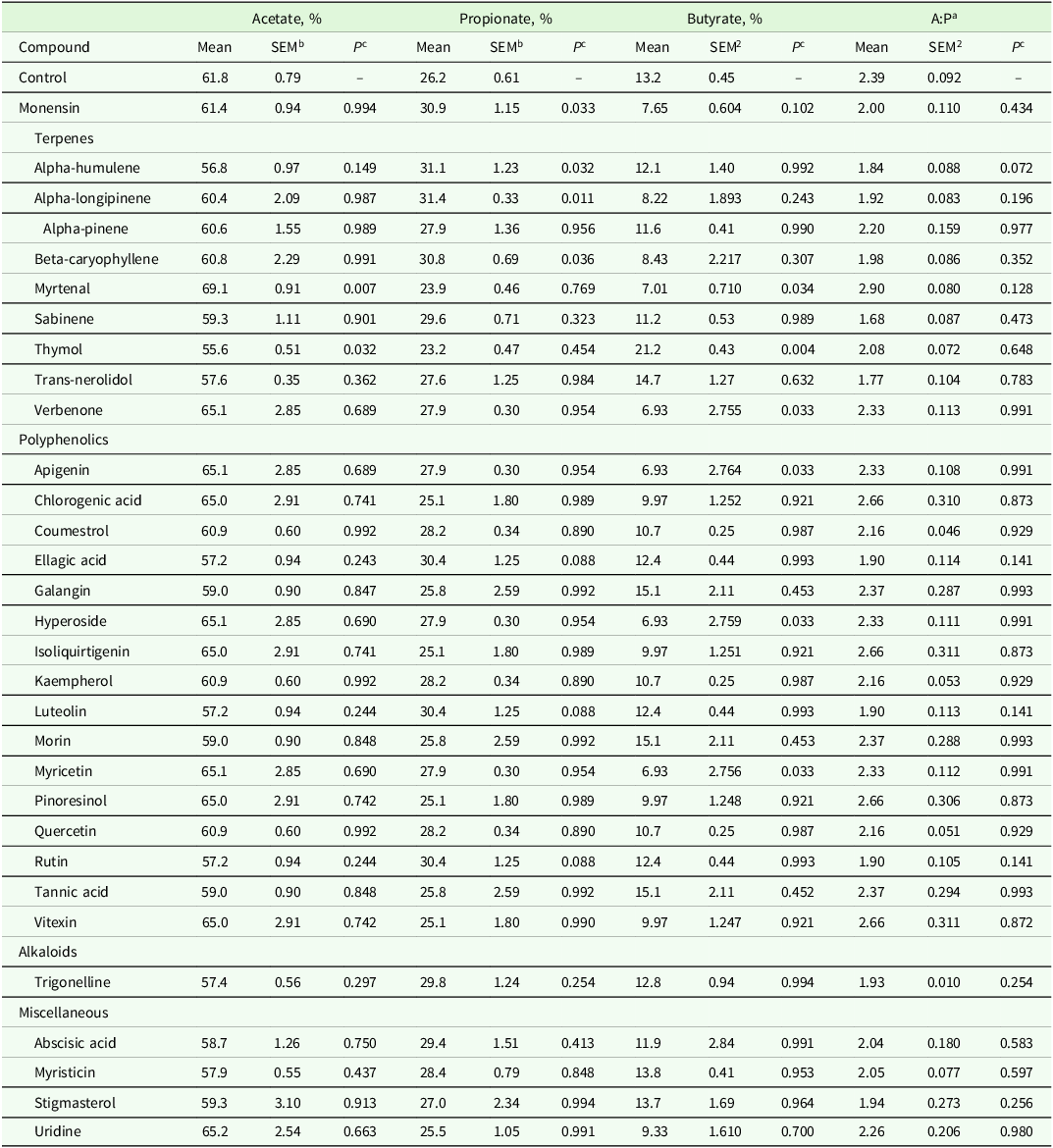

Molar proportions of acetate, propionate and butyrate for CTRL were 61.8 ± 0.79, 26.2 ± 0.61 % and 13.2 ± 0.45 %, respectively (Table 3). Thymol reduced (P = 0.03) the proportion of acetate in the fermentation fluid by 10.0 %, while myrtenal increased (P < 0.01) molar proportion of acetate by 11.8 %. No PSM treatments reduced propionate molar proportion after 48 h of fermentation, however propionate concentration was increased (P ≤ 0.03) 19.8 % by alpha-longipinene, 18.7 % by alpha-humulene, 17.9 % by monensin and 17.6 % by beta-caryophyllene. Rutin, lutoeolin and ellagic acid tended (P ≤ 0.10) to increase molar proportion of propionate by 16 %. Furthermore, apigenin (47.5 % decrease), verbenone (47.5 %). Myricetin (47.5 %) and myrtenal (46.9 %) reduced (P = 0.03) butyrate concentration, whereas thymol increased (P < 0.03) butyrate concentration by 60.6 %. Monensin tended (P = 0.10) to reduce butyrate concentration by 42.0 %. The average ratio of acetate:propionate (A:P) for CTRL was 2.39 ± 0.086. Alpha-humulene tended to decrease A:P by 23 %, but no other PSM altered A:P.

Table 3. The effects of pure plant secondary metabolites (25 mg compound/g substrate dry matter) on molar proportions of volatile fatty acids following 48 h of batch culture rumen fermentation

a Acetate:propionate ratio.

b SEM=Standard error of the mean (n = 4/treatment)

c P-value of the Dunnett’s test comparing each compound to a control containing rumen fluid, buffer and feed substrate.

Discussion

The current study aimed to evaluate the impact of 30 pure PSM on methane production using in vitro techniques and understand their associated changes in rumen fermentation and nutrient digestibility. The PSM treatments in the current study were selected because they exist at basal concentrations in various cover crops grown in the Great Lakes region (Burkin and Kononenko, Reference Burkin and Kononenko2022; Carlsen and Fomsgaard, Reference Carlsen and Fomsgaard2008; Clemensen et al., Reference Clemensen, Provenza, Lee, Gardner, Rottinghaus and Villalba2017; Kpoviessi et al., Reference Kpoviessi, Agbahoungba, Agoyi, Nuwamanya, Assogbadjo, Chougourou and Adoukonou-Sagbadja2021; Siddiqui et al., Reference Siddiqui, Saleha and Nayak2025). Previous experiments have primarily focused on signature compounds in high concentrations in certain plant varieties (i.e. thymol in Mentha species) as these compounds can be fed in greater concentrations via plant extracts. However, this approach fails to appreciate the potential anti-methanogenic activity of compounds in lower concentrations that could be fed to dairy cattle as feed additives. Due to the novelty of these compounds as potential methane-reducing agents, previous research on these compounds’ effects on rumen fermentation is limited. Therefore, literature regarding general antimicrobial activity and chemical structure of various classes of PSM will be discussed as potential modes of action to aid in the explanation of methane production results. Plant secondary metabolites can be broadly categorised based on chemical structure into four main categories: terpenoids, polyphenols, alkaloids and sulphur-containing compounds, and each of these different categories have their own potential mechanisms of action (Guerriero et al., Reference Guerriero, Berni, Muñoz-Sanchez, Apone, Abdel-Salam, Qahtan, Alatar, Cantini, Cai and Hausman2018).

Terpenes

Terpenoids are a class of plant compounds that are biosynthesised by forming covalent bonds between 5-carbon isoprene subunits and altering functional groups, yielding a great diversity of compounds (Ninkuu et al., Reference Ninkuu, Zhang, Yan, Fu, Yang and Zeng2021). The antimicrobial activity of terpenoids is related to their chemical structure and properties, which includes number and position of acidic hydroxyl groups (Guimarães et al., Reference Guimarães, Meireles, Lemos, Guimarães, Endringer, Fronza and Scherer2019), presence of stereochemically strained ring structures (Mabou and Yossa, Reference Mabou and Yossa2021) and capacity for intermolecular hydrogen bonding (Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, Wyllie, Markham and Leach1999). Terpenes are known to have multiple modes of action against ruminal microbes, such as cellular membrane disruption and enzyme inhibition (Kholif and Olafadehan, Reference Kholif and Olafadehan2021). In the current study, the antimicrobial activity of the terpenes, such as thymol and sabinene, was realised as a substantial 77.3 % average reduction in methane production. While we are unaware of previous literature regarding these results with respect to sabinene’s impacts specifically on rumen microbes, previous pure culture studies have demonstrated antimicrobial activity against gram-positive bacterial species Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus mutans (Ghazal et al., Reference Ghazal, Schelz, Vidács, Szemerédi, Veres, Spengler and Hohmann2022; Park et al., Reference Park, Kim, Kim and You2019). We suspect the compound’s unique chemical structure was an important factor resulting in reductions in total gas production and methane concentration. Sabinene is the only PSM treatment evaluated that contains a strained three-membered ring. Due to steric hindrance, strained ring structures are highly reactive to nucleophilic functional groups present on microbial membranes or present on residues within the cytosol of microbes (Sadyrbekov et al., Reference Sadyrbekov, Saliev, Gatilov, Kulakov, Seidakhmetova, Seilkhanov and Askarova2018). Compounds with strained ring structures can exhibit an array of antimicrobial activity depending on the site of the reaction with microbes, such as destabilising cell membranes or deactivating proteins in the microbial cytosol (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Cheng, Shi, Gao, Huang and Du2024). The impacts of sabinene on methane production were twofold, as sabinene simultaneously reduced total gas production and methane concentration. Sabinene reduced total gas production by 28.0 % while reducing methane concentration by 61.9 %, suggesting that the presence of cyclopropane functional groups could be an important factor driving anti-methanogenic activity of PSM. The reduction in methane concentration for sabinene could be partially explained by the numerical 29.7 % reduction in acetate:propionate ratio, suggesting hydrogen was spared from reduced methanogenesis were diverted towards propionate synthesis (Ungerfeld, Reference Ungerfeld2020). Sabninene’s reduction in methane emissions occurred without altering dry matter digestibility and with only a slight reduction in NDF digestibility that did not differ from monensin and is unlikely to be biologically significant. Future experiments focused on elucidating the specific anti-microbial effects of sabinene within the rumen, as well as its long-term efficacy are warranted as it reduced methane production significantly without adverse consequences on digestibility of NDF and DM.

Contrary to the more specific mode of action of sabinene, the reduction in methane production due to thymol supplementation is likely associated with its broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity (Evans and Martin, Reference Evans and Martin2000). Within our study, the substantial suppression of DMD and VFA concentrations by thymol is consistent with this indiscriminate inhibition of microbial growth. Therefore, despite causing a substantial reduction in methane production, its efficacy as an antimicrobial feed additive for ruminants is limited due to its negative effects on nutrient digestibility. The results of our study are consistent with those reported by Pirondini et al. (Reference Pirondini, Colombini, Malagutti, Rapetti, Galassi, Zanchi and Crovetto2015), who observed similar magnitudes of reduction in total gas production, methane production and DMD.

Interestingly, the terpenes trans-nerolidol, alpha-pinene and verbenone substantially increased methane production by 104.4, 149.2 and 108 %, respectively. These increases in methane production were driven by a significant increase methane concentration of headspace gas and not by increases in total gas production. These results suggest that both compounds selectively shift metabolism to promote methanogenesis. While it is unclear how these specific terpenes increased methane concentration and production, terpenes are known to increase diversity of methanogens which is associated with increased methane production (Ohene-Adjei et al., Reference Ohene-Adjei, Chaves, McAllister, Benchaar, Teather and Forster2008; Patra and Saxena, Reference Patra and Saxena2010). Greater diversity of methanogens could yield greater headspace methane concentration through a greater array of substrate reduction pathways that yield methane. Interestingly, alpha-pinene increased dry matter digestibility and total VFA concentrations while simultaneously reducing NDF digestibility by 30 %. These results suggest that alpha-pinene may specifically inhibit the growth or activity or cellulolytic bacteria, while promoting the growth of non-cellulolytic bacteria. While, to our knowledge, there has been no specific characterisation on the effects of alpha-pinene on cellulolytic bacterial growth, Soni et al. (Reference Soni, Sharma and Jasuja2016) demonstrated that dosing Bacillus subtilis, a species with cellulolytic activity within the rumen, is inhibited by oil extracts of Myristica fragrans (nutmeg), which is highly enriched in alpha-pinene. Plants are capable of interconverting verbenone and alpha-pinene due to their structural similarities (Limberger et al., Reference Limberger, Aleixo, Fett-Neto and Henriques2007), which suggests they may have a similar mode of action for increasing methane concentration and methane production for verbenone as alpha-pinene. However, while alpha-pinene increased DM digestibility and decreased NDF digestibility, verbenone decreased DM digestibility with no effects on NDF digestibility. We speculate that modes of action for these compounds could either be through acting as growth factors for microbes associated with methanogenesis or having specific activity inhibiting microbes associated with pathways that hinder methanogenesis. Notably, none of these three terpenes altered VFA profile, suggesting that alterations in methane metabolism are not related to changes in major changes in VFA metabolism.

Polyphenols

Polyphenolic compounds are characterised by the presence of multiple aromatic rings with bound hydroxyl groups and include flavones, flavonols, flavanals, flavanones and their respective isomers (Panche et al., Reference Panche, Diwan and Chandra2016). These polyphenolic classes have various functions in vegetative plants, but primarily serve as antioxidants due to the diverse yet stable aromatic structures (Foyer and Shigeoka, Reference Foyer and Shigeoka2011). The aromaticity of polyphenolics is a contributing factor to the number and distribution of hydroxyl and methoxy functional group bonding sites, which are associated with antimicrobial activity (Górniak et al., Reference Górniak, Bartoszewski and Króliczewski2019). The polyphenolic flavonoids evaluated in the current study had variable impacts on methane production, ranging from an 81.3 % reduction to a 165.5 % increase in methane production. This array of responses is representative of the vast structural diversity of polyphenolic compounds.

The polyphenols rutin, vitexin, apigenin and quercetin reduced methane production by an average of 79.5 %. Of these, rutin and apigenin did so without reducing total gas production. Quercetin and rutin are nearly structurally identical, with rutin having the same base structure of quercetin, but with a L-Rhamose and D-glucose attached to the C3 hydroxyl group of its middle aromatic ring (and as such is also named quercetin-3-O-rutinoside). The sugar moieties of rutin have been shown to be fermented by rumen microbes, leaving an identical biochemical structure to quercetin (Aldian et al., Reference Aldian, Harisa, Tomita, Tian, Takashima, Iwasawa and Yayota2025). Therefore, it is unsurprising that both compounds led to similar effects on methane production. Nørskov et al. (Reference Nørskov, Battelli, Curtasu, Olijhoek, Chassé and Nielsen2023) also reported that quercetin supplementation to batch culture was more potent in reducing total gas production as means for reducing methane production compared to rutin. They suggested the presence of the sugar moiety in rutin dilutes this effect by contributing mass but not antimicrobial functionality. We observed that quercetin did not reduce DM or fibre digestibility, while both were reduced by rutin. These results suggest that the impacts of rutin on digestibility were likely due to fermentation of their sugar moieties, which potentially increased acid production within batch cultures and subsequently reduced fibre digestion. Nonetheless, quercetin in particular shows promise as a potentially novel anti-methanogenic feed additive. Neither quercetin nor rutin impacted VFA concentrations within our study. These results are similar to research in human faecal batch cultures, where both compounds failed to alter short-chain fatty acid profiles (Mansoorian et al., Reference Mansoorian, Combet, Alkhaldy, Garcia and Edwards2019). The failure to alter VFA profiles suggests that quercetin may impart its anti-methanogenic effects through diverting hydrogen to an alternate hydrogen sink such as sulphate or nitrate reduction. Future research exploring these alternate mechanisms is warranted.

The flavones apigenin and vitexin are also structurally similar to each other, but vitexin contains a sugar moiety at the C8 position, whereas apigenin contains a lone hydrogen at this position. While both compounds reduced total gas concentration, methane concentration and methane production, the mechanism of action appears to be different based on VFA profile. While vitexin supplementation increased molar proportions of propionate, which would be consistent with a canonical shift in hydrogen flows from methanogenesis to propionate synthesis, apigenin had no impacts on VFA profile. To our knowledge, there is no previous literature focused on impacts of purified apigenin and vitexin in rumen cultures. However, Oskoueian et al. (Reference Oskoueian, Abdullah and Oskoueian2013) reported reduced in vitro methane production for flavone, which is structurally similar to apigenin and vitexin. Dry matter digestibility was reduced by vitexin, but not apigenin. Interestingly, like rutin, vitexin contains sugar moieties and may reduce digestibility due to fermentation acid production rather than antimicrobial activity of the compound itself. While apigenin did not reduce DM digestibility, it reduced NDF digestibility, making them unlikely candidates for future exploration as reasonable methane-reducing feed additives for dairy cattle. Practically speaking, neither apigenin nor vitexin likely warrant further in vivo investigation at the concentration included in the current study due to their negative impacts on nutrient digestibility.

Ellagic acid and chlorogenic acid both reduced total gas production but increased methane concentration, resulting in an increase in methane yield. The lower gas production observed for both of these compounds was consistent with the substantial reduction in DM and NDF digestibility. Our results for ellagic contrast with Manoni et al. (Reference Manoni, Gschwend, Amelchanka, Terranova, Pinotti, Widmer, Silacci and Tretola2024), who reported a 12.5 % reduction in methane production when supplementing 24 h batch culture with rumen fluid from Brown Swiss cattle with pure ellagic acid at 7.5 % of diet DM. Ellagic acid is a hydrolysable tannin derivative that can be converted to other compounds called urolithins during anaerobic fermentation (Espín et al., Reference Espín, Larrosa, García-Conesa and Tomás-Barberán2013). The relative production of different urolithins has been shown to be microbiome-dependent in humans (Tomás-Barberán et al., Reference Tomás-Barberán, García-Villalba, González-Sarrías, Selma and Espín2014). Discrepancies between these two studies may result from differences in microbial population due to length of inoculation, rumen fluid donor breed and PSM dosage, which may shift the abundances of urolithins and affect antimicrobial activity. Chlorogenic acid is formed in plants when from esterification of caffeic acid and quinic acid (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Zhen, Li, Wang and Wang2013). While we are unfamiliar with previous literature characterising the impacts of chlorogenic acid on methane production, Jin et al. (Reference Jin, You, Tan, Liu, Zhang, Liu, Wan and Wei2021) reported an increase in in vitro methane production when caffeic acid was supplemented to batch culture. Chlorogenic acid is known to be rapidly hydrolysed to caffeic acid and quinic acid in rumen fluid (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kuppusamy, Jung, Kim and Choi2021). Therefore, it is likely quinic acid, and potentially caffeic acid were responsible for the observed increase in methane production.

Luteolin, a flavone, increased methane production by increasing total gas production, which agrees with the 15.7 % increase in DMD associated with luteolin supplementation. Experiments evaluating pure luteolin on rumen fermentation are scarce. However, Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Kim, Eom, Choi, Jo, Chu, Lee, Seo, Kim and Lee2021) reported that olive leaves are naturally enriched with luteolin and increase both total gas and methane production when used as a feed additive in batch culture. The isoflavinoid coumestrol reduced total gas production and NDF digestibility, but increased methane concentration and yield. Interestingly, VFA concentrations were also increased by luteolin despite the decrease in NDF digestibility. Coumestrol is known to have strong antioxidant properties towards reactive oxygen species (ROS) due to the presence of its multiple hydroxyl groups and aromatic rings (Montero et al., Reference Montero, Arriagada, Günther, Bollo, Mura, Berríos and Morales2019). Genome sequencing has revealed that ruminal methanogens are known to contain only a small number of ROS-neutralizing genes (Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Shriker, Gold, Durman, Zarecki, Ruppin and Mizrahi2017), making them specifically susceptible to the cytotoxic effects of ROS. There is a possibility that coumestrol alleviated ROS-related stress due to its scavenging properties, which could have increased methanogenic activity.

Alkaloids

Alkaloids are a broad classification of organic compounds that contain a heterocyclic ring with a nitrogen atom (Adamski et al., Reference Adamski, Blythe, Milella and Bufo2020). In the current study, the alkaloid trigonelline, which has demonstrated a wide variety of general antimicrobial mechanisms, including disrupting quorum sensing pathways and reducing biofilm formation, was tested (Kar et al., Reference Kar, Mukherjee, Barik and Hossain2024). Trigonelline reduced total gas production, increased methane concentration and ultimately increased total methane production. These results are unfavourable for rumen fermentation as an ideal feed additive would reduce methane production by selectively inhibiting methanogens to reduce methane concentration while having neutral or positive impact on total gas production, given that greater gas production is associated with greater rate of fibre digestion. Indeed, trigonelline reduced fibre digestibility by 26 %. While previous literature lacks information on the specific mode of action of trigonelline in rumen microbes, its biofilm-disrupting properties may inhibit the ability for adherence of cellulolytic bacteria to adhere to fibre particles and facilitate lysis, which is a crucial process in fibre digestion (McAllister et al., Reference McAllister, Bae, Jones and Cheng1994). Overall, trigonelline shows minimal potential as an anti-microbial feed additive for ruminants.

Miscellaneous

While some PSM have direct activity against microbial pathogens, other compounds serve within the vegetative plant’s immune system indirectly by serving as signalling molecules, acting as precursor molecules to be converted into other compounds and reinforcing the plant’s cell walls (Piasecka et al., Reference Piasecka, Jedrzejczak‐Rey and Bednarek2015). Uridine is a compound enriched in plants during episodes of stress that can be rapidly converted to other PSM (Jung et al., Reference Jung, Flörchinger, Kunz, Traub, Wartenberg, Jeblick, Neuhaus and Möhlmann2009). Uridine itself contains strong antimicrobial activity upon hydrolysis of its sugar moiety (Kawsar et al., Reference Kawsar, Islam, Jesmin, Manchur, Hasan and Rajia2018). Uridine was numerically the strongest inhibitor of methane production in the current study, due to substantially reducing methane concentration. We speculate that this may be due to specific activity against methanogens of bioactive derivatives of uridine containing a high ratio of O:C upon hydrolysis of the bound sugar unit. We are not familiar with previous studies evaluating uridine or its derivatives on methane production to corroborate the findings of the current study. While its effects on methane production are promising, the potential use of uridine as a feed additive is limited due to the significant reduction in NDF digestibility. Future research regarding this PSM as a feed additive to reduce methane production should include evaluation of lower dosage levels to potentially mitigate negative impacts on fibrolytic microbes.

Abscisic acid is a hormone that aids in the initiation of transcription of genes related to the production of cytokines during pathogenic stresses to the vegetative plant (Hirayama and Shinozaki, Reference Hirayama and Shinozaki2007). Interestingly, abscisic acid is also produced not only by plants, but also by bacteria and fungi, suggesting potential intra-kingdom signalling (Lievens et al., Reference Lievens, Pollier, Goossens, Beyaert and Staal2017). Abscisic acid was a potent inhibitor of methane production by reducing both methane concentration and total gas production, while also greatly reducing total VFA concentration. The direct antimicrobial mode of action for abscisic acid on microorganisms is not well-characterized, and future work is needed to elucidate its mechanism and impact on the rumen microbial community. However, despite the significant reduction in methane concentration associated with abscisic acid, further characterization of the compound’s impacts on fermentation are likely not warranted due to its inhibition of DM and NDF digestibility and VFA synthesis.

Stigmasterol is a phytosterol with broad antimicrobial activity against both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria (Bakrim et al., Reference Bakrim, Benkhaira, Bourais, Benali, Lee, El Omari, Sheikh, Goh, Ming and Bouyahya2022). Of all PSM treatments, stigmasterol resulted in the greatest methane production due to increases in both total gas production and methane concentration. Moreover, the increased gas production and increased NDF digestibility observed with stigmasterol inclusion suggested it enhances microbial activity within the rumen. The increase in total gas production of the current study is in accordance with Xi et al. (Reference Xi, Jin, Lin and Han2014), who supplemented batch culture with a stigmasterol-rich blend of phytosterols. The group also reported an increase in microbial cell protein yield and suggested this was a function of reduced bacterial predation by protozoa, which would have contributed to greater total gas production for phytosterol supplementation Xi et al. (2014). Phytosterols naturally occur in many forage crops and can be induced by stress and pathogen presence. Given their dramatic effects on fermentation in rumen culture, there may be benefits of testing their concentrations within feeds during routine analysis.

Conclusions

The current study served to preliminarily screen novel PSM for impacts on methane production, which varied greatly depending on both compound class and structure. While many PSM reduced methane production, most of them did so by reducing total gas production and nutrient digestibility, which limits their potential applicability. Plant secondary metabolites likely overwhelm the ecology of the rumen, especially regarding fibrolytic microbes, when in concentrations comparable to that of feed additives. Future research should evaluate PSM with strong anti-methanogenic potential at lower dosages to potentially alleviate the negative impacts of said PSM on nutrient digestibility and fermentation. Sabinene and uridine successfully reduced methane production without compromising nutrient digestibility, suggesting viability for these compounds as potent methane inhibitors. The current study tested the effects of all compounds at a single dose, and future dose-response studies are critical to understanding the optimal inclusion rate of these compounds within ruminant diets. Moreover, experiments using continuous culture fermentation systems and in vivo experiments are crucial to understanding whether the efficacy of these compounds are maintained over long-term exposures.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859626100537

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr. Todd Rappe and the Minnesota NMR centre for technical assistance with the analysis of VFAs in our samples. We would also like to thank the staff at the University of Minnesota Dairy Teaching and Research Center for the husbandry of the donor cattle used in the current study.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: JDS, DJH and IJS; Methodology: JDS, DJH and IJS; Formal analysis: JDS and IJS; Investigation: JDS; Validation: JDS, DJH and IJS; Resources: DJH and IJS; Writing- original draft: JDS; Writing-reviewing & editing: JDS, DJH and IJS; Visualisation: JDS and IJS; Supervision: DJH and IJS; Project administration: DJH and IJS; Funding acquisition: DJH and IJS.

Funding statement

Research was supported by Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station (MAES) Project No. MIN-16-131 (Accession no. 1027137; PI IJS); USDA-ARS project 062-21500-001-000D with partial graduate student support provided by the state of Minnesota via the MnDRIVE Global Food Ventures fellowship (JDS).

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. All experiments complied with the current laws of the United States, the country in which they were performed.

Ethical standards

All animal procedures were approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol ID: 2502-42790A).