Introduction

Volunteering in general enjoys wide political support, the year 2001 was declared International Year of Volunteers by the UN, and the 10th anniversary was named as the European Year of Volunteering by the EU. In line with its growing popularity, international volunteering has, though, an increased responsibility in the success of humanitarian missions. However, fashionable international volunteering has become, it is still a very under-researched discipline (Lough et al., Reference Lough, McBride and Sherraden2009). According to Tian and McConachy (Reference Tian and McConachy2021), most research represents positivist paradigm attitude reflecting mainly on the positive sides and benefits, and the difficulties and risks of volunteering are not always revealed.

In Hungary, similarly to other Central and East European countries, international volunteering has a history of barely more than 20 years and is only lightly embodied in public recognition. Although many studies examined the domestic volunteering from different perspectives, no similar research is available in Hungary about international volunteering.

The main objectives of this paper are to examine that how the significant roles, effects, and benefits of international volunteering, as outlined in the literature, are present in the awareness of the Hungarian public, and also to reveal the experiences of returned Hungarian volunteers including their reflections on their readiness/preparation prior to the voluntary mission, and also on the challenges and difficulties they met. The authors assume that international volunteering has all the important functions and benefits in Hungary, but that its practice falls short of its potential and is much less visible than its global significance and importance. Because of this shortcoming, it is misunderstood and misjudged by the public.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Definitions

International volunteering is generally defined as a form of work without financial remuneration, initiated by the volunteer through an act of free will, and undertaken in a foreign country for the benefit of other people or community (Harkin, Reference Harkin2008). This is the historical or functional interpretation of volunteering focusing on the philanthropic or altruistic approach to help the poor and underdeveloped countries (Baillie Smith & Laurie, Reference Baillie Smith and Laurie2011).

In recent decades, however, international volunteering has become “a complex phenomenon that spans a wide variety of activities” which requires a multidimensional approach to understand its roles, benefits, and impacts (Hustinx et al., Reference Hustinx, Cnaan and Handy2010). Devereux (Reference Devereux2008, p.2) explains international volunteering as a form of international cooperation “that does bring benefits (and costs) to individual volunteers at the same time as providing the space for an exchange of technical skills, knowledge and experience in developing communities.” The European Parliament understands international volunteering in a wider context and emphasis its role in social capital and its contribution to building civic society and solidarity among all participants (Harkin, Reference Harkin2008). According to Talarski (Reference Talarski2014), international volunteering improves intercultural understanding and fosters global citizenships and peace.

The complex interpretation of international volunteering includes, therefore, the personal side of the volunteers (their motivation to volunteer and how they personally change afterward), the experiences and challenges of the actual voluntary work (intercultural inclusion and difficulties), and the effects and consequences of volunteering (local development and global citizenship) to the recipient countries/communities as well as to the donor societies (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Reid, Toncar, Fawcet and Anderson2006; Wilde et al., Reference Wilde, Bentall, Blum and Bourn2017).

Volunteers’ Motivation and Self-Development

At the beginning of international volunteering, the main motivations of volunteers were primary the willingness to help poor countries and communities (Baillie Smith & Laurie, Reference Baillie Smith and Laurie2011; Lough, Reference Lough2015), the religious-driven participation, or the motivation following family or social traditions (Wilson, Reference Wilson2000). Today, their motivation background has become much more individual and includes many personal objectives, such as wishing to travel, learning languages, self-development, obtaining cultural or professional experiences, etc. (Hustinx & Lammertyn, Reference Hustinx and Lammertyn2003; Wuthnow, Reference Wuthnow1991).

After evaluating 22 earlier published empirical research, Lough (Reference Lough2008, p. 7) stated that in line with their original motivations, international volunteering has four different types of effect imposed on the person and identity of volunteers: change in their attitude and worldview, improvement of personal skills and competencies (communications, problem-solving, intercultural understanding, etc.), building up carrier skills and opportunities, and strengthening their civic commitment in the future. Other international studies made in Canada, Finland, and New Zealand also confirmed that their returned volunteers experienced development in their personal and interpersonal skills, intercultural communication, community thinking, and civic attitude (Government of Canada, 2002; McKivison, Reference McKivison2018; McLachlan, Reference McLachlan2018). About 53% of former British volunteers said that their international volunteering experiences were advantageous in their later carrier (Brook et al., Reference Brook, Missingham, Hocking and Fifer2007), while 67–90% of volunteers became active in community volunteering upon returning home (Alexander, Reference Alexander2012; Kelly & Case, Reference Kelly and Case2008). In general, 80% of former British volunteers agreed that their skills and competency development could not have been achieved without being international volunteers (Cook & Jackson, Reference Cook and Jackson2006). A German study added that persons doing any type of volunteering are happier with their lives than their peers without volunteering involvement (Meier & Stutzer, Reference Meier and Stutzer2004).

Benefits for the Donor Societies

Many research emphasize that the amount of the widened interpersonal and labor skills, changed attitude and personal identity of returned volunteers significantly contribute to the social development of donor countries, making it one of the most important roles of international volunteering (Baillie Smith & Laurie, Reference Baillie Smith and Laurie2011; Wilde et al., Reference Wilde, Bentall, Blum and Bourn2017; Wu, Reference Wu2011). Wuthnow (Reference Wuthnow1991) researched that returned volunteers care more about social problems, feel important to challenge them, and, in general, create vision of a better society. According to an American study, 80% of the returned volunteers said that they would take active part in domestic volunteering, and their civic commitment was 25% higher than that of the non-volunteers (Wu, Reference Wu2011). The Norwegian government purposefully support international volunteering because it believes that returned volunteers would strongly contribute to global citizenship and social activism, and both are important goals for Norway (Culture Ministry of Norway, 2014).

Role in Global Development

Despite the positive effects imposed on the participants and the donor societies alike, the main objective of international volunteering is to give hand to communities and countries in need (Perold et al., Reference Perold, Graham, Mavungu, Cronin, Muchemwa and Lough2013). This pro-social activity (de Groot & Steg, Reference de Groot and Steg2008) takes form through the personal activity of volunteers who help with the execution of humanitarian and international development programs with skill and knowledge transfer, educational support, and enthusiastic physical manpower (Devereux, Reference Devereux2008; Molnár, Reference Molnár2021).

Most of the international volunteering programs support the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN (United Nations, 2015; Lough, Reference Lough2015) either directly or under the umbrella of transnational bodies, such as the EU, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (furtherly referred to as OECD), or the UN. The geographic proportion of international volunteers is in close correlation with the ratio of international development aids (OECD.org, 2022) allocated to developing countries and continents (McCarthy & Macleod, Reference McCarthy and Macleod2019; OECD.Stat, 2021). The same connection can be experienced between the areas of voluntary programs and financially supported sectors. Appr. 44% of official development assistance (furtherly referred to as ODA) is turned to health care, education, and social development projects worldwide, while 30–49% of all international volunteer programs work in the same sectors. Similar correlation applies to the economy and agriculture modernization, and as well as other humanitarian areas (McCarthy & Macleod, Reference McCarthy and Macleod2019; OECD.org, 2019; OECD.Stat, 2021; Lough, Reference Lough2012). International volunteering plays, therefore, significant and unquestionable role in global development. As Burns et al. (Reference Burns, Reid, Toncar, Fawcet and Anderson2006, p.81) said, “without volunteers, many development programmes would cease to exist.”

The economic value of international volunteering is hard to state, but an American research projected it between USD 2.3 and 2.9 billion annually based on the US volunteers’ overseas activity only (Lough et al., Reference Lough, McBride and Sherraden2009). As the annal number of international volunteers is estimated between 1 and 1.6 million globally (Lough, Reference Lough2012; Yea et al., Reference Yea, Sin and Griffiths2018), the overall volunteering value may amount to a much higher figure.

Hungarian Situation

International volunteering has been consciously organized in Hungary since the early 2000s. Previously, the country had no history or experience of overseas volunteering. Then, in 2003, the first Hungarian NGO exclusively dedicated to international volunteering was established, in 2005, volunteering was regulated by law, and since 2012, there has been a government-level National Volunteer Strategy. In 2017, the Hungary Helps program started its operations, which coordinates and finances Hungary's international humanitarian and development activities with the involvement of international volunteers. Hungarian volunteers have access to the largest European and international volunteering programs and to the humanitarian and development projects of a growing number of Hungarian NGOs, working mainly in sub-Saharan Africa.

The motivationFootnote 1 and demographic characteristics of Hungarian volunteers (25.5 years old, 70–30% female and 90–95% university graduates) are similar to international statistics. The gap is in the underfunding of the sector, the low number of volunteers (it ranges from barely 500 to 700 per year),Footnote 2 as well as its minimal visibility/awareness in the public (Molnár, Reference Molnár2022).

Challenges and Difficulties of Volunteering

The result of the voluntary programs depends significantly on bridging the intercultural differences between the volunteers and the recipient communities (Lough, Reference Lough2013). Ensuring the needed cultural immersion requires a long adaptation process to overcome the cultural shock that most foreign volunteers inevitable meet (Lysgaard, Reference Lysgaard1955). The adaptation depends on their cultural tolerance and competencies, but it can be improved by intercultural training and education prior to the program as well as local communications support (Vinickytė et al., Reference Vinickytė, Bendaravičienė and Vveinhardt2020).

Several studies examined the existence of orientalism (simplified and stereotypical colonialist discourse) that still effects both parties in international volunteering. Some of them confirmed it (Bruce, Reference Bruce2018; Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2018), but other research confuted its presence (Pastran, Reference Pastran2014). Although it is dominantly not a conscious behavior of the volunteers, members of the local communities still can feel it otherwise.

International volunteering has many critical discourses (Schech & Mundkur, Reference Schech and Mundkur2017; Yea et al., Reference Yea, Sin and Griffiths2018) dealing with the threats imposed on the volunteers or the host communities. Some of the biggest risks of volunteering (or humanitarianism in general) are when the aid objectives are set exclusively in the donor countries, local partners are not involved in planning, and the programs are culturally inappropriately prepared and executed. All of them result in preserving power imbalances and will not cause real development (Perold et al., Reference Perold, Graham, Mavungu, Cronin, Muchemwa and Lough2013).

International volunteers should be aware of their intercultural responsibility and be able to manage the challenges; otherwise, they will become personally frustrated, disappointed, and loose commitment, while recipient communities will be dissatisfied with the programs and will easily resist further cooperation (Brown, Reference Brown2018; Jackson & Adarlo, Reference Jackson and Adarlo2014).

As introduced above, international volunteering is a thorough social activity that plays an important role in global development and has significant effects and benefits imposed on not just the recipient communities but on the volunteers and the donor countries as well. That inspired this research to reveal its awareness and perception in the Hungarian population and collect the experiences and difficulties of returned Hungarian volunteers.

We broke the examined areas into four research questions:

-

RQ1. How Hungarian respondents think about the effects of international volunteering?

-

RQ2. What homogeneous groups of respondents can be identified based on their attitude to international volunteering? What characterizes these respondent segments.

-

RQ3. Those who were already international volunteers, what difficulties did they face, and what benefits did they experience from their activities in terms of the recipient community and their own personal development.

-

RQ4. Can significant differences be identified between volunteers' experiences based on volunteering and volunteer characteristics?

Our research assumption was that since international volunteering in Hungary has no historical tradition, with a past of less than 20 years, and the number of volunteers is very low (500–700 per year), Hungarian society knows very little about international volunteering and is not aware of its impact or benefits. There can be several misconceptions and misbelieves in people’s perception.

Hungarian volunteers who go abroad are not fully aware of the benefits and difficulties they can expect. Our research aimed to identify and explore this problem.

Research Methodology

Data Collection

Quantitative online survey was conducted with convenience sampling. To achieve the biggest possible response rate and reach all major target segments, combined sampling frames were used. Countrywide general channels were used to reach ordinary non-volunteer citizens; the Google form was shared on various social media platforms, including closed and open interest groups specialized in topics related to domestic or international volunteering. It was circulating in universities to collect opinions of students. Many volunteer-sending organizations agreed to send the questionnaire to their members or posted it to their mailing lists. The questionnaire was available between July 6 and October 29 in 2022. During this period, 344 responses were collected. Out of them, 73 respondents were international volunteer, and 203 did earlier non-compulsory domestic volunteering activity.

Measurement

For the operationalization, the researchers decided to use self-formulated statements based on the processing of the theoretical background and best suited to their research goals, instead of a validated model. The questionnaire includes the examination of three sub-topics.

The first part examined how respondents relate to volunteering, and how they think about the role of volunteering. To explore this, researchers formulated positive and negative statements about the possible effects of volunteering (measured on a 6-point Likert scale), and statements that sought to explore respondents' attitude toward international volunteering (measured on a 5-point Likert scale).

The second part of questionnaire focused on those respondents who were not international volunteers, to gain insight into what they know and how they think about international volunteering.

The third part of the questionnaire focused on respondents who earlier took part in international volunteering, to reveal what difficulties they faced and what positive experiences they gained from their volunteering activities. To explore this, the researchers formulated statements regarding the possible difficulties, and the possible development areas of the host community and the volunteer responses were measured on 6-point Likert scale, where 1 represents the most negative and 6 the most positive response.

The respondents' demographic characteristics were asked at the end of the second and third sections of the questionnaire, separately collecting the data of those who had not yet participated in an international volunteer program and those who had.

Data Analysis

SPSS 28.0 was used to data analysis. In addition to the descriptive statistics (frequency, mean, and standard deviation), the association between the nominal variables was examined with the Chi-square test, and the variables measured on the Likert scale with the analysis of variance.

To form homogeneous groups (segments) among the respondents of the entire sample based on their attitude toward international volunteering, K-means cluster analysis was performed. K-means clustering is the division of the dataset into non-overlapping subsets (GeeksforGeeks, 2020). The algorithm uses a pre-specified number of clusters (which may be based on a theory or hypothesis, a statistical estimation, or through trial-and-error) and sorts each data point into the cluster with the nearest mean value (Lund & Ma, Reference Lund and Ma2023). Before cluster analysis, factor analysis was conducted to reduce the distorting effect of close correlation among the formulated statement variables. The purpose of factor analysis is to identify latent variables that explain the correlation pattern within a set of measured variables, and to identify a few factors that explain the variance observed in a much larger number of manifest variables (data reduction) (IBM Documentation Help, 2021).

The answers measured on a nominal scale by our respondents who have not yet participated in international volunteering were analyzed with frequency distribution and Chi-square tests.

Based on the Likert scale answers of our respondents already participating in international volunteering, we tried to identify the areas that appeared as problems or advantages during volunteer work using factor analysis. The relationship between the demographic characteristics of the respondents who previously participated in international volunteering and the statement components was examined using variance analysis.

Sample Composition

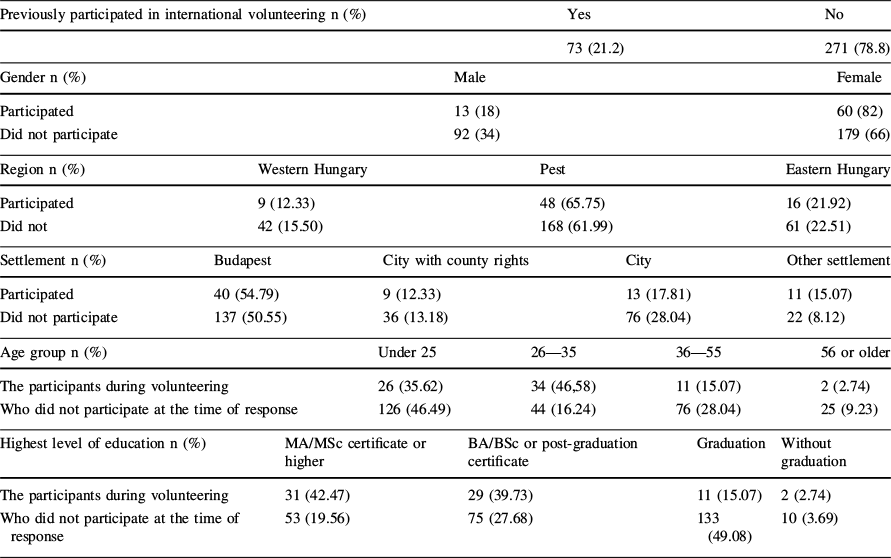

Table 1 shows the demographic distribution of the sample according to the examined characteristics.

Table 1 Demographic distribution of the sample.

|

Previously participated in international volunteering n (%) |

Yes |

No |

|---|---|---|

|

73 (21.2) |

271 (78.8) |

|

Gender n (%) |

Male |

Female |

|---|---|---|

|

Participated |

13 (18) |

60 (82) |

|

Did not participate |

92 (34) |

179 (66) |

|

Region n (%) |

Western Hungary |

Pest |

Eastern Hungary |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Participated |

9 (12.33) |

48 (65.75) |

16 (21.92) |

|

Did not |

42 (15.50) |

168 (61.99) |

61 (22.51) |

|

Settlement n (%) |

Budapest |

City with county rights |

City |

Other settlement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Participated |

40 (54.79) |

9 (12.33) |

13 (17.81) |

11 (15.07) |

|

Did not participate |

137 (50.55) |

36 (13.18) |

76 (28.04) |

22 (8.12) |

|

Age group n (%) |

Under 25 |

26—35 |

36—55 |

56 or older |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The participants during volunteering |

26 (35.62) |

34 (46,58) |

11 (15.07) |

2 (2.74) |

|

Who did not participate at the time of response |

126 (46.49) |

44 (16.24) |

76 (28.04) |

25 (9.23) |

|

Highest level of education n (%) |

MA/MSc certificate or higher |

BA/BSc or post-graduation certificate |

Graduation |

Without graduation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The participants during volunteering |

31 (42.47) |

29 (39.73) |

11 (15.07) |

2 (2.74) |

|

Who did not participate at the time of response |

53 (19.56) |

75 (27.68) |

133 (49.08) |

10 (3.69) |

Results and Discussion

Respondents Attitude Toward the International Volunteering (RQ1)

Respondents were asked to indicate on a 6-point Likert scale how important they think the listed effects are (1—"very insignificant" and 6—the "very significant"). The first column of Fig. 1 shows the groups of effects of international volunteering. These are the positive effects on participating volunteers, on Hungarian employers/companies, on the Hungarian nation/society and internationally, and some possible negative effects. The second column shows the statements by impact groups. The bars show the mean value of importance according to the opinion of the respondents.

Fig. 1 The listed effects of international volunteering and their average importance based on the opinion of the respondents.* Standard deviations were similar for all items (ranging from 0.904 to 1.339)

The respondents considered the effects on the volunteer's personal development to be the most significant (range of means is between 5.37 and 4.58), but the mean of the significance of the other positive effects also reached a value of around 4, which indicates that the respondents considered these as well significant. The assessment of possible negative effects reached a significance of 3.18 or lower for all statements, which means that the listed problems are not perceived as significant by the respondents.

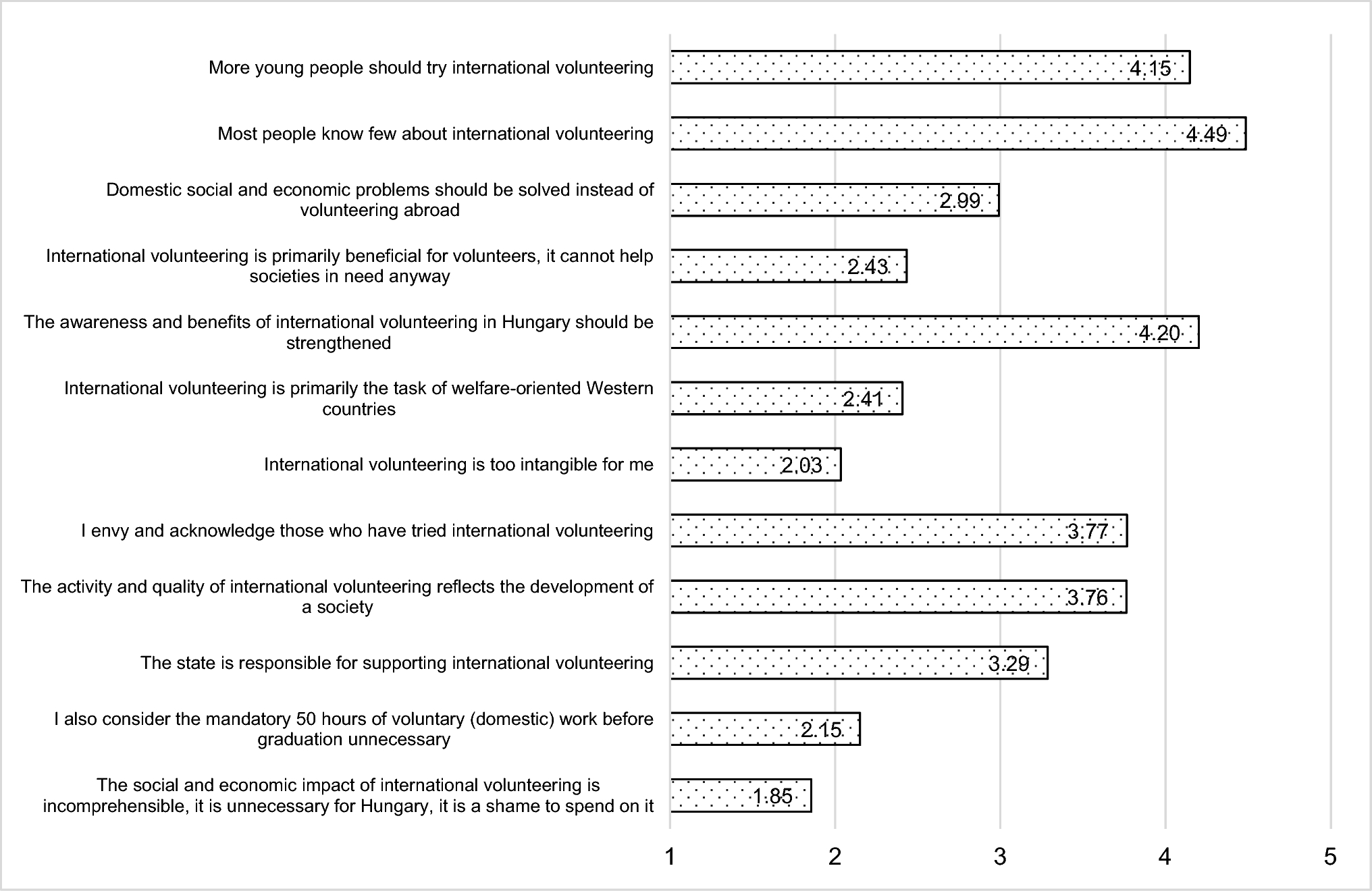

To gain a deeper understanding of respondents' attitudes, additional statements were formulated to examine how respondents evaluate international volunteering, to which they gave answers on a 5-point Likert scale (1 means "totally disagree", while 5 means "strongly agree"). Figure 2 shows that majority of respondents agreed that most people know few about international volunteering (4.49), its awareness and benefits should be strengthened in Hungary (4.20), and more young people should try it (4.15). In accordance with this, the respondents did not agree (1.85) that it is unnecessary and shame to spend on international volunteering.

Fig. 2 The statements about international volunteering and the mean values of agreement of respondents.* Standard deviations were similar for all items (ranging from 0.712 to 1.127)

One of the objectives of this study was to identify homogeneous groups among the respondents based on their attitudes toward international volunteering. To reduce the distorting effect of the correlation among the variables, factor analyses were performed. Since we used variables measured on even- and odd-numbered scales, we performed separate factor analysis on the variables of the effects and the variables of perceptions of international volunteering.

Factors of Effect and Perception Statements (RQ2)

Before the factor analyses, we examined the suitability of the sample for factor analysis both for the variables related to the effects and for the variables related to the perception of international volunteering. Based on the results of KMO measure of sampling adequacy (it was 0.880 and 0.796, respectively) and Bartlett’s sphericity test (both were sig. 0.000), our sample is appropriate for the factor analysis.

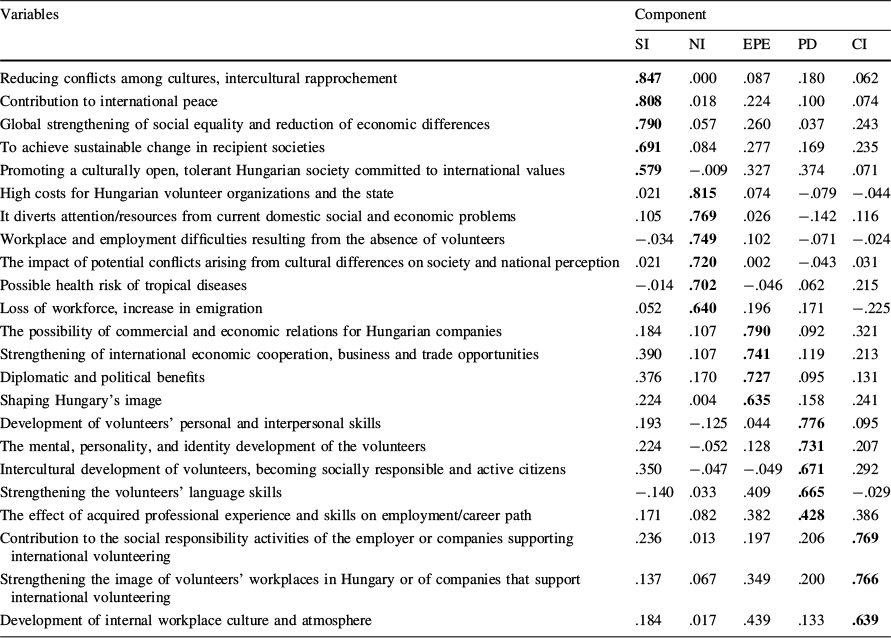

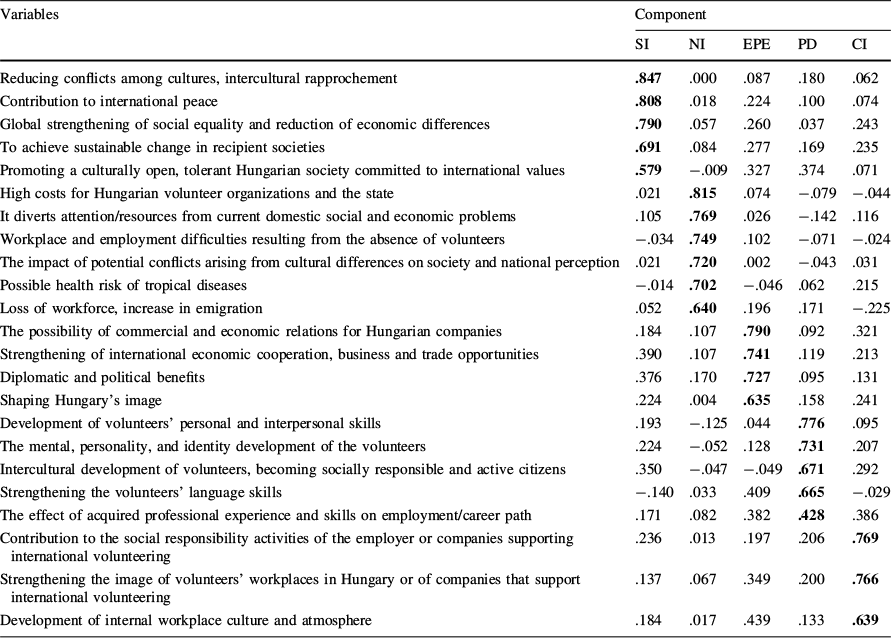

The 23 variables examining the significance of the impact of international volunteering were combined into five components by factor analysis, while retaining 65.425% of the explanatory power of the variables. Table 2 contains the five components and the variables on which they are based.

Table 2 Rotated component matrix of effect variables.

|

Variables |

Component |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SI |

NI |

EPE |

PD |

CI |

|

|

Reducing conflicts among cultures, intercultural rapprochement |

.847 |

.000 |

.087 |

.180 |

.062 |

|

Contribution to international peace |

.808 |

.018 |

.224 |

.100 |

.074 |

|

Global strengthening of social equality and reduction of economic differences |

.790 |

.057 |

.260 |

.037 |

.243 |

|

To achieve sustainable change in recipient societies |

.691 |

.084 |

.277 |

.169 |

.235 |

|

Promoting a culturally open, tolerant Hungarian society committed to international values |

.579 |

−.009 |

.327 |

.374 |

.071 |

|

High costs for Hungarian volunteer organizations and the state |

.021 |

.815 |

.074 |

−.079 |

−.044 |

|

It diverts attention/resources from current domestic social and economic problems |

.105 |

.769 |

.026 |

−.142 |

.116 |

|

Workplace and employment difficulties resulting from the absence of volunteers |

−.034 |

.749 |

.102 |

−.071 |

−.024 |

|

The impact of potential conflicts arising from cultural differences on society and national perception |

.021 |

.720 |

.002 |

−.043 |

.031 |

|

Possible health risk of tropical diseases |

−.014 |

.702 |

−.046 |

.062 |

.215 |

|

Loss of workforce, increase in emigration |

.052 |

.640 |

.196 |

.171 |

−.225 |

|

The possibility of commercial and economic relations for Hungarian companies |

.184 |

.107 |

.790 |

.092 |

.321 |

|

Strengthening of international economic cooperation, business and trade opportunities |

.390 |

.107 |

.741 |

.119 |

.213 |

|

Diplomatic and political benefits |

.376 |

.170 |

.727 |

.095 |

.131 |

|

Shaping Hungary's image |

.224 |

.004 |

.635 |

.158 |

.241 |

|

Development of volunteers' personal and interpersonal skills |

.193 |

−.125 |

.044 |

.776 |

.095 |

|

The mental, personality, and identity development of the volunteers |

.224 |

−.052 |

.128 |

.731 |

.207 |

|

Intercultural development of volunteers, becoming socially responsible and active citizens |

.350 |

−.047 |

−.049 |

.671 |

.292 |

|

Strengthening the volunteers' language skills |

−.140 |

.033 |

.409 |

.665 |

−.029 |

|

The effect of acquired professional experience and skills on employment/career path |

.171 |

.082 |

.382 |

.428 |

.386 |

|

Contribution to the social responsibility activities of the employer or companies supporting international volunteering |

.236 |

.013 |

.197 |

.206 |

.769 |

|

Strengthening the image of volunteers' workplaces in Hungary or of companies that support international volunteering |

.137 |

.067 |

.349 |

.200 |

.766 |

|

Development of internal workplace culture and atmosphere |

.184 |

.017 |

.439 |

.133 |

.639 |

The bold numbers indicate which component the variables (items) load most strongly on

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization

SI, Social impact; NI, Negative impact; EPE, Economic and political effects; PD, Personal development; and CI, Corporate impact

Rotation converged in seven iterations

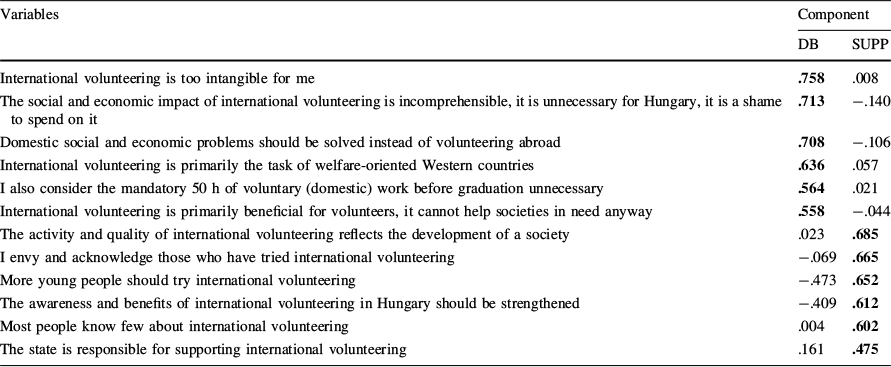

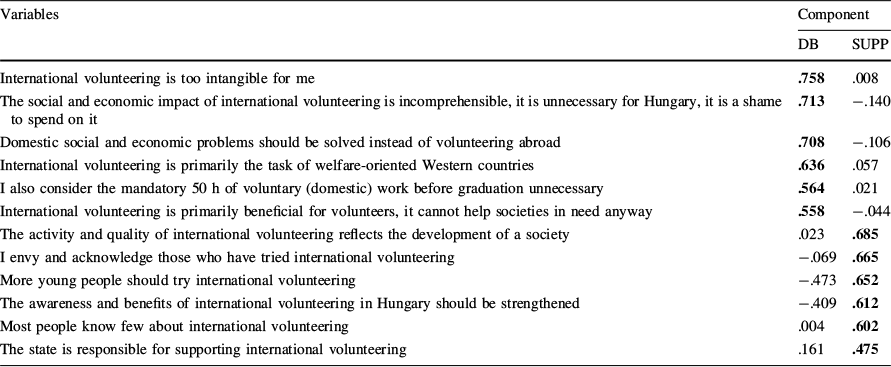

The factor analysis combined the 12 variables related to the perception of international volunteering into two components, with 44.825% of the explanatory power retained. Both components are based on six variables each, which reflect doubts about international volunteering on the one hand, and a positive perception of it on the other hand (as shown in Table 3).

Table 3 Rotated component matrix of variables relate to the perceptions of international volunteering.

|

Variables |

Component |

|

|---|---|---|

|

DB |

SUPP |

|

|

International volunteering is too intangible for me |

.758 |

.008 |

|

The social and economic impact of international volunteering is incomprehensible, it is unnecessary for Hungary, it is a shame to spend on it |

.713 |

−.140 |

|

Domestic social and economic problems should be solved instead of volunteering abroad |

.708 |

−.106 |

|

International volunteering is primarily the task of welfare-oriented Western countries |

.636 |

.057 |

|

I also consider the mandatory 50 h of voluntary (domestic) work before graduation unnecessary |

.564 |

.021 |

|

International volunteering is primarily beneficial for volunteers, it cannot help societies in need anyway |

.558 |

−.044 |

|

The activity and quality of international volunteering reflects the development of a society |

.023 |

.685 |

|

I envy and acknowledge those who have tried international volunteering |

−.069 |

.665 |

|

More young people should try international volunteering |

−.473 |

.652 |

|

The awareness and benefits of international volunteering in Hungary should be strengthened |

−.409 |

.612 |

|

Most people know few about international volunteering |

.004 |

.602 |

|

The state is responsible for supporting international volunteering |

.161 |

.475 |

The bold numbers indicate which component the variables (items) load most strongly on

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization

DB, Doubts and SUPP, Supports

Rotation converged in three iterations

Segments of Respondents Based on their Attitudes Toward International Volunteering

Based on the factors identified in the previous factor analyses, the 344 respondents were classified by K-means cluster analysis from 2-cluster to 6-cluster solution.

The distribution of sample among the clusters is relative balanced in each of these solutions. From these cluster solutions, only the 4-cluster classifications showed significant (< 0.001 sig. level) in each factor; therefore, this cluster solution was examined further. The case numbers of these segments were 44, 69, 140, and 90 respondents, respectively. The boxplot of the factor center deviations of the 4 clusters is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 The boxplot of international volunteering evaluation factors for the four clusters.

Based on the factor centers deviation, the members of the 1st cluster considered the effects of international volunteering to be less significant in the field of international, economic and political, as well as personal development, and in its corporate effects compare to effects evaluation of other segments. In line with this, doubt is higher, and support deviates downward from the factor center. This segment was called the “Negatives.”

Members of the 2nd cluster support international volunteering, and value the importance of international influences the most, but consider its role in personal development to be much less important compared to other clusters. This segment is the “Believers international development impact.”

The 3rd cluster deviates from the factor center of the sample upwards in all positive impact factors and support factor, while downwards in the case of negative effects and doubt factor. They are the “Optimists.”

Although the members of the 4th cluster evaluated the factors of the effects of international volunteering similarly to the sample average in the different areas, they deviate upwards from the sample in terms of negative effects and the doubt factor, therefore, they became the “Doubters.”

The opinions of the members of the clusters showed a significant difference not only for the individual factors, but also for the individual variables at a confidence level higher than 99%.

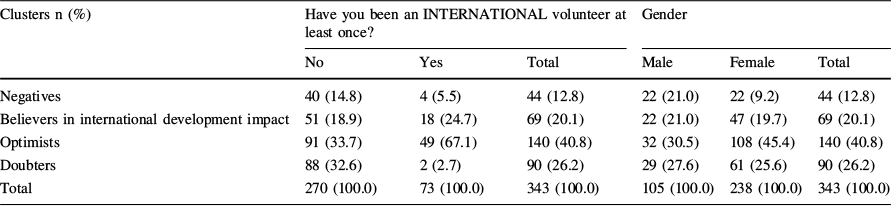

The composition of the segments was examined based on previous participation in international volunteering and gender (Table 3). The composition of the clusters showed a significant difference at the < 0.001 confidence level in both aspects. More than 2/3 of those who have already been international volunteers belong to the optimistic segment, and almost 1/5 belonged to the segment of believers in international development. This distribution is encouraging because more than 90% of those who have their own experience with the effects of international volunteering perceive it positively. Those who have not yet been international volunteers are both included in the Optimists and Doubters segments in a ratio of one-third.

About one-third of those who have not yet been international volunteers are in the Optimists segment and a similar proportion in the Doubters segment. Their proportion in the segment of Negatives is more than twice the proportion of previous volunteers.

Examining the gender distribution of the clusters, 65% of the female respondents are members of the Optimists and Believers in international development impact segments, which show a more positive attitude compared to the two other clusters, while just over half of the men belong to the two positive segments (Table 4).

Table 4 The distribution of gender and those who previously participated in international volunteering and those who did not participate among the clusters.

|

Clusters n (%) |

Have you been an INTERNATIONAL volunteer at least once? |

Gender |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No |

Yes |

Total |

Male |

Female |

Total |

|

|

Negatives |

40 (14.8) |

4 (5.5) |

44 (12.8) |

22 (21.0) |

22 (9.2) |

44 (12.8) |

|

Believers in international development impact |

51 (18.9) |

18 (24.7) |

69 (20.1) |

22 (21.0) |

47 (19.7) |

69 (20.1) |

|

Optimists |

91 (33.7) |

49 (67.1) |

140 (40.8) |

32 (30.5) |

108 (45.4) |

140 (40.8) |

|

Doubters |

88 (32.6) |

2 (2.7) |

90 (26.2) |

29 (27.6) |

61 (25.6) |

90 (26.2) |

|

Total |

270 (100.0) |

73 (100.0) |

343 (100.0) |

105 (100.0) |

238 (100.0) |

343 (100.0) |

Previous volunteer activity and the gender distribution among the clusters match each other, as the proportion of women among former volunteers is 82%, while among those who have not yet volunteered it is only 66% (see earlier in Table 1).

Examining the Experiences of Former International Volunteers (RQ3 and RQ4)

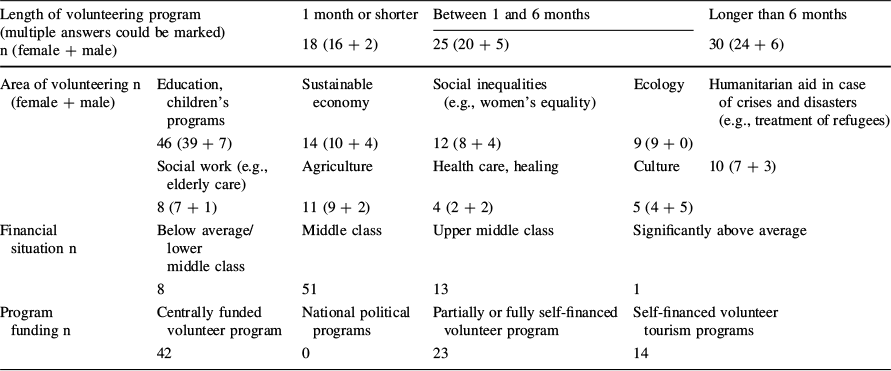

In the next phase of the research, the motivations and experiences of those who have already participated in an international volunteer program will be examined. Table 5 provides further details on the sample composition shown in Table 1.

Table 5 Additional information to composition of subsample of former international volunteers.

|

Length of volunteering program (multiple answers could be marked) n (female + male) |

1 month or shorter |

Between 1 and 6 months |

Longer than 6 months |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

18 (16 + 2) |

25 (20 + 5) |

30 (24 + 6) |

|||

|

Area of volunteering n (female + male) |

Education, children's programs |

Sustainable economy |

Social inequalities (e.g., women's equality) |

Ecology |

Humanitarian aid in case of crises and disasters (e.g., treatment of refugees) |

|

46 (39 + 7) |

14 (10 + 4) |

12 (8 + 4) |

9 (9 + 0) |

||

|

Social work (e.g., elderly care) |

Agriculture |

Health care, healing |

Culture |

10 (7 + 3) |

|

|

8 (7 + 1) |

11 (9 + 2) |

4 (2 + 2) |

5 (4 + 5) |

||

|

Financial situation n |

Below average/lower middle class |

Middle class |

Upper middle class |

Significantly above average |

|

|

8 |

51 |

13 |

1 |

||

|

Program funding n |

Centrally funded volunteer program |

National political programs |

Partially or fully self-financed volunteer program |

Self-financed volunteer tourism programs |

|

|

42 |

0 |

23 |

14 |

||

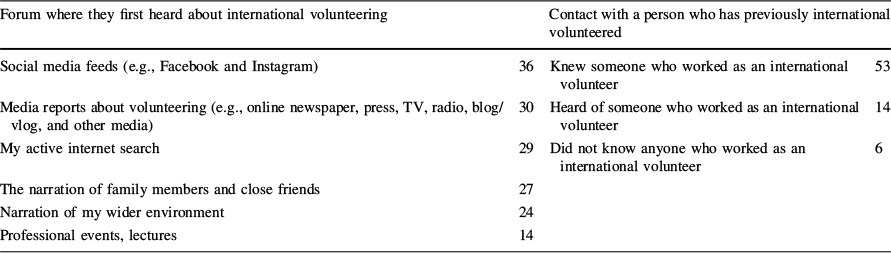

Table 6 shows how the 73 respondents—who had already participated in international volunteering—first met these programs in descending order of marking frequency (multiple answers could be marked). It is not possible to draw far-reaching conclusions based on the 73 respondents; however, the result provides information on which information sources can be the most frequently targeted in this topic. The social media feeds, media news is in the top 2 places in terms of frequency, and important fact that the majority of these respondents (53 of 73) had an acquaintance with first-hand experience (in family or in wider acquaintances).

Table 6 Frequency of information sources related to international volunteering.

|

Forum where they first heard about international volunteering |

Contact with a person who has previously international volunteered |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Social media feeds (e.g., Facebook and Instagram) |

36 |

Knew someone who worked as an international volunteer |

53 |

|

Media reports about volunteering (e.g., online newspaper, press, TV, radio, blog/vlog, and other media) |

30 |

Heard of someone who worked as an international volunteer |

14 |

|

My active internet search |

29 |

Did not know anyone who worked as an international volunteer |

6 |

|

The narration of family members and close friends |

27 |

||

|

Narration of my wider environment |

24 |

||

|

Professional events, lectures |

14 |

||

The main motivations of respondents for applying for international volunteering (with multiple response) in descending frequency were the “Desire for adventure, opportunity to travel” (55); “Helping purpose” (54); “Cultural curiosity” (54); and the “Personal development” (48).

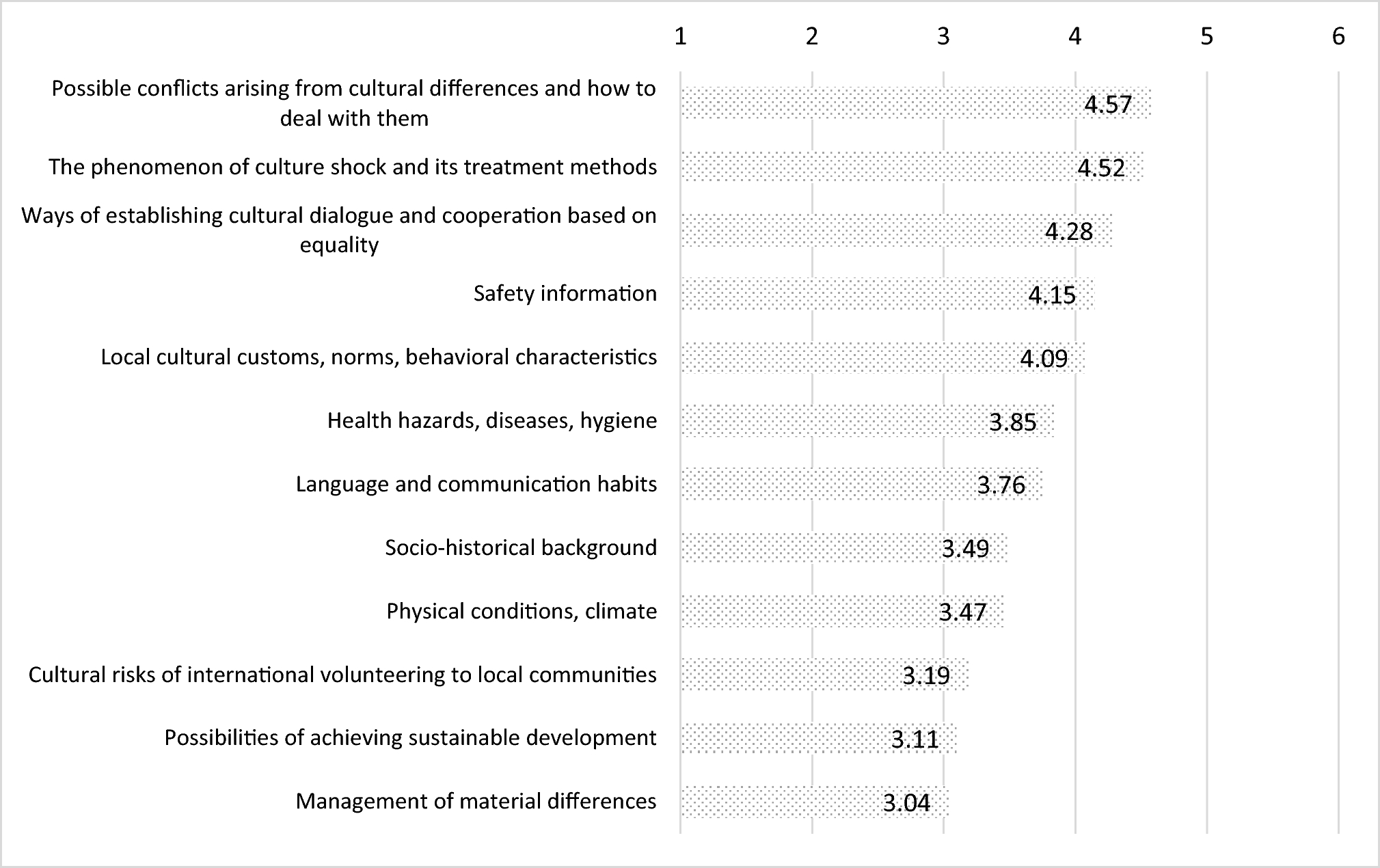

Forty-three from the 73 international volunteers participated in preparation before the departure. They evaluated the usefulness of certain content elements of the preparation on a 6-point Likert scale. Figure 4 shows the mean values of usefulness of the preparation elements in descending order. How can they deal with conflicts arising cultural differences, treat cultural shock, and establish cultural dialog, the safety information and the description of local norms and behavior were the elements considered somewhat useful by respondents.

Fig. 4 Usefulness of content elements of the preparation.* Standard deviations were similar for all items (ranging from 1.378 to 1.650)

Former volunteers were asked about the severity of the difficulties they encountered during volunteering. The importance of the problems could be indicated on a 6-point Likert scale (1—did not appear as a difficulty at all and 6—was a very serious problem for me). Each of the listed problems received an average value of less than 3 (except for language skills, which had an average value of 3.14), which means that none of the listed problems significantly hampered the respondents' voluntary activities.

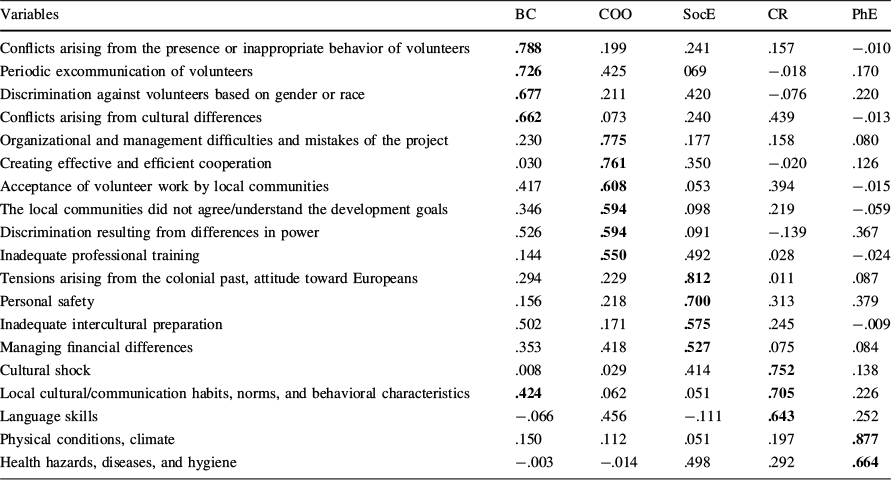

Factor analysis was performed to identify problem groups within the listed problem statements. KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.818, and Bartlett’s sphericity test showed 0.000 significance level, which means the sample appropriateness for the factor analysis. The 19 variables were grouped into five components by factor analysis (Table 7), preserving 71.721% of the explanatory power of the variables.

Table 7 Rotated component matrix with factors of difficulties arising during volunteering.

|

Variables |

BC |

COO |

SocE |

CR |

PhE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Conflicts arising from the presence or inappropriate behavior of volunteers |

.788 |

.199 |

.241 |

.157 |

−.010 |

|

Periodic excommunication of volunteers |

.726 |

.425 |

069 |

−.018 |

.170 |

|

Discrimination against volunteers based on gender or race |

.677 |

.211 |

.420 |

−.076 |

.220 |

|

Conflicts arising from cultural differences |

.662 |

.073 |

.240 |

.439 |

−.013 |

|

Organizational and management difficulties and mistakes of the project |

.230 |

.775 |

.177 |

.158 |

.080 |

|

Creating effective and efficient cooperation |

.030 |

.761 |

.350 |

−.020 |

.126 |

|

Acceptance of volunteer work by local communities |

.417 |

.608 |

.053 |

.394 |

−.015 |

|

The local communities did not agree/understand the development goals |

.346 |

.594 |

.098 |

.219 |

−.059 |

|

Discrimination resulting from differences in power |

.526 |

.594 |

.091 |

−.139 |

.367 |

|

Inadequate professional training |

.144 |

.550 |

.492 |

.028 |

−.024 |

|

Tensions arising from the colonial past, attitude toward Europeans |

.294 |

.229 |

.812 |

.011 |

.087 |

|

Personal safety |

.156 |

.218 |

.700 |

.313 |

.379 |

|

Inadequate intercultural preparation |

.502 |

.171 |

.575 |

.245 |

−.009 |

|

Managing financial differences |

.353 |

.418 |

.527 |

.075 |

.084 |

|

Cultural shock |

.008 |

.029 |

.414 |

.752 |

.138 |

|

Local cultural/communication habits, norms, and behavioral characteristics |

.424 |

.062 |

.051 |

.705 |

.226 |

|

Language skills |

−.066 |

.456 |

−.111 |

.643 |

.252 |

|

Physical conditions, climate |

.150 |

.112 |

.051 |

.197 |

.877 |

|

Health hazards, diseases, and hygiene |

−.003 |

−.014 |

.498 |

.292 |

.664 |

The bold numbers indicate which component the variables (items) load most strongly on

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization

Rotation converged in 11 iterations

BC, Behavioral conflicts; COO, Cooperation; SocE, Socio-economic; CR, Culture in recipient country; and PhE, Physical environment

Conflicts arising from different cultures also appeared in two factors (factors 1 and 4). The 1st factor sits on four variables, among which the “Conflicts arising from cultural differences” shows close relation with the 4th factor also, while the 4th factor sits on three variables, among which the “Local cultural / communication habits, norms, behavioral characteristics” also shows close relationship with the 1st factor. Considering these, the 1st factor rather connects to the behavioral conflicts, while 4th factor, the differences of the recipient culture is more weighted. Cooperation difficulties appeared in the 2nd factor (sits on six variables), socio-economic differences in the 3rd factor (sits on four variables), and difficulties arising from environmental factors in the 5th factor (sits on two variables).

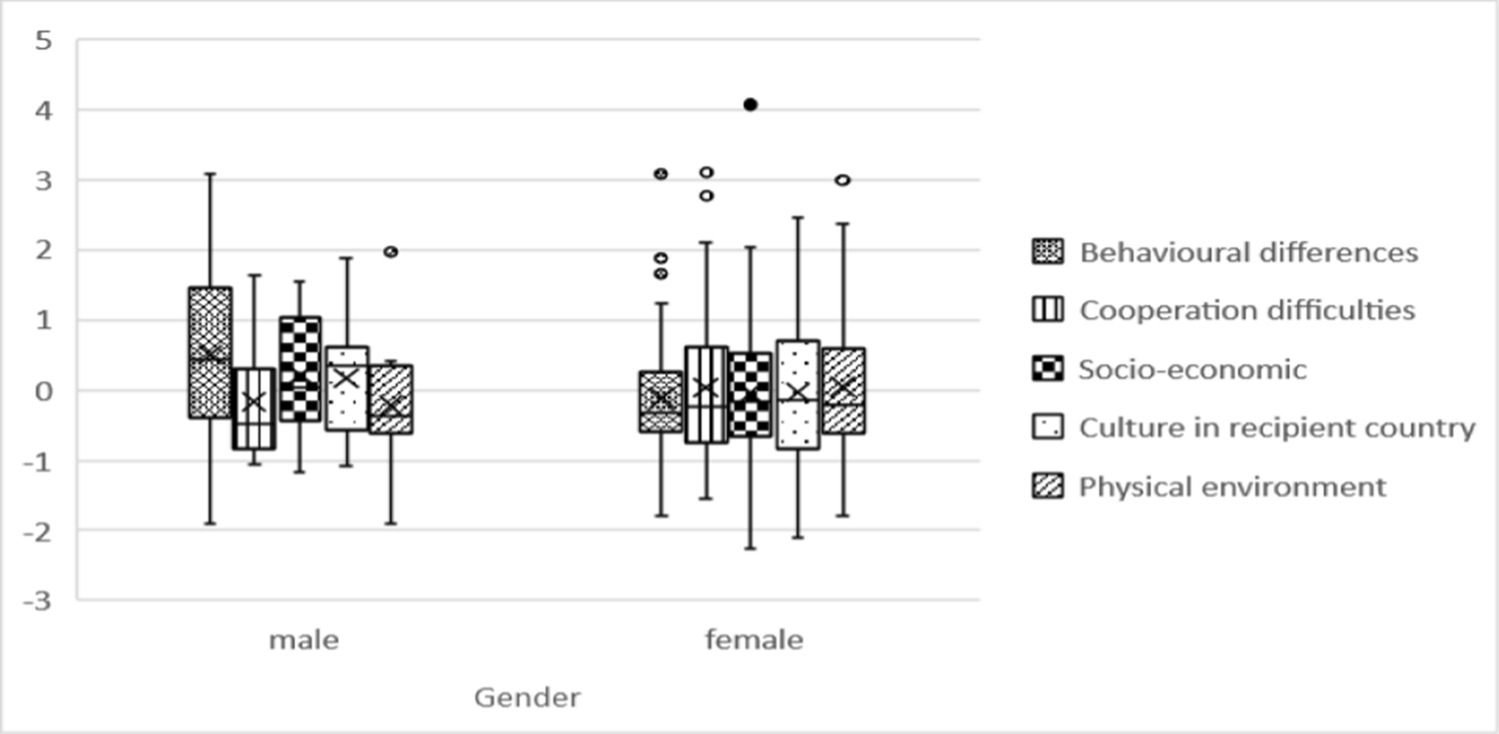

The difference in the perception of the problem factors based on the time spent out as a volunteer, the age and education level at the time of volunteering, and the respondent's gender and financial situation was examined using variance analysis. Of these characteristics of the respondents, only gender showed a significant difference in the perception of difficulty factors, especially in case of the variables belong to the 1st (behavioral conflicts) factor. Although this was not really a problem for the male volunteers either, the women encountered it even less during their volunteering (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Boxplot of problem factors by gender.

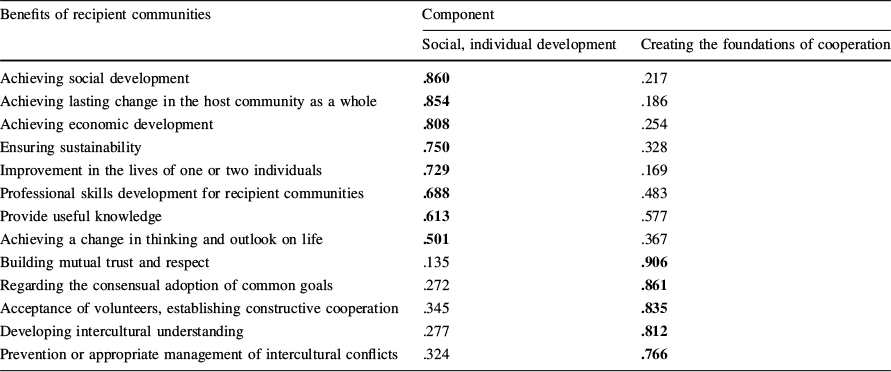

The benefits associated with volunteering were also measured using a 6-point Likert scale, both in terms of the recipient community and the personal development of the volunteer. To identify groups of benefits within the listed statements, factor analysis was used for both the host community and the volunteer's personal development. KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.862 and 0.846 (in the recipient community and in their personal development, respectively), and Bartlett’s sphericity test showed 0.000 significance level (in both cases), which means the sample appropriateness for the factor analysis. Thirteen variables related to the benefits of recipient community were grouped into two components, the 18 variables related to the personal developments of volunteers were grouped into four components by factor analysis, preserving 70.773% and 74.241% of the explanatory power of the original variables, respectively.

The results achieved in the recipient community were divided into two components. The 1st component sits on eight variables which connect to the society of the recipient community and the individual development of its members. The 2nd component sits on five variables, which relate to the foundation of cooperation (Table 8).

Table 8 Rotated component matrix of variables related to the volunteering benefits of recipient community.

|

Benefits of recipient communities |

Component |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Social, individual development |

Creating the foundations of cooperation |

|

|

Achieving social development |

.860 |

.217 |

|

Achieving lasting change in the host community as a whole |

.854 |

.186 |

|

Achieving economic development |

.808 |

.254 |

|

Ensuring sustainability |

.750 |

.328 |

|

Improvement in the lives of one or two individuals |

.729 |

.169 |

|

Professional skills development for recipient communities |

.688 |

.483 |

|

Provide useful knowledge |

.613 |

.577 |

|

Achieving a change in thinking and outlook on life |

.501 |

.367 |

|

Building mutual trust and respect |

.135 |

.906 |

|

Regarding the consensual adoption of common goals |

.272 |

.861 |

|

Acceptance of volunteers, establishing constructive cooperation |

.345 |

.835 |

|

Developing intercultural understanding |

.277 |

.812 |

|

Prevention or appropriate management of intercultural conflicts |

.324 |

.766 |

The bold numbers indicate which component the variables (items) load most strongly on

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization

Rotation converged in three iterations

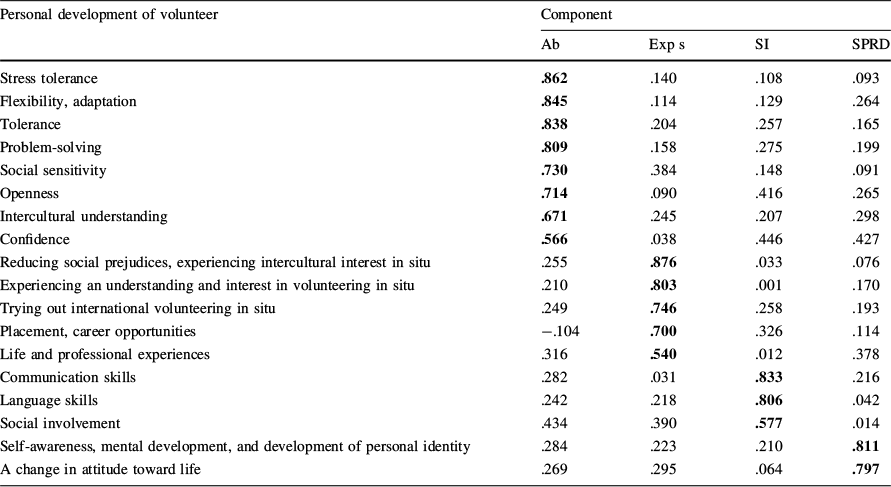

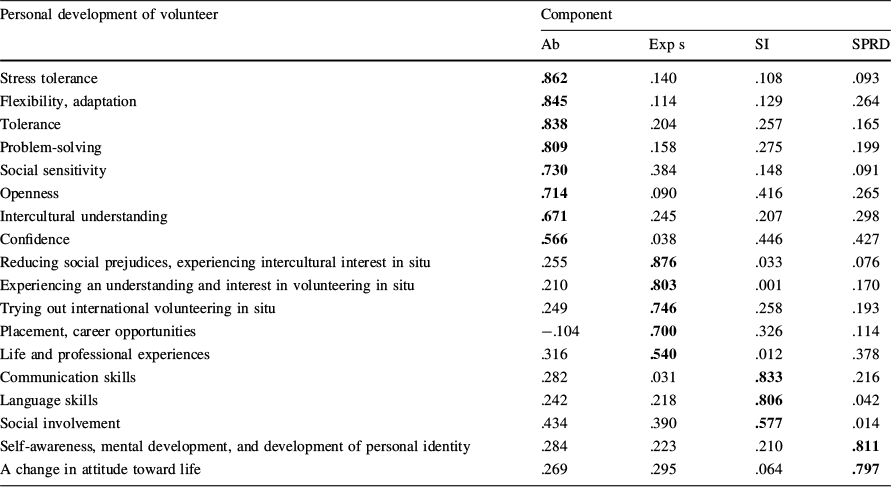

The variables related to the volunteers' personal development could be classified into four groups by factor analysis. The 1st component sits on eight variables relate to the personal abilities, the 2nd sits on five variables connect to the experiences, the 3rd component sits on three variables which connect to skills and involvement, and the 4th component with two variables include the spiritual development of volunteers (Table 9).

Table 9 Rotated component matrix of variables related to the personal development of volunteers.

|

Personal development of volunteer |

Component |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ab |

Exp s |

SI |

SPRD |

|

|

Stress tolerance |

.862 |

.140 |

.108 |

.093 |

|

Flexibility, adaptation |

.845 |

.114 |

.129 |

.264 |

|

Tolerance |

.838 |

.204 |

.257 |

.165 |

|

Problem-solving |

.809 |

.158 |

.275 |

.199 |

|

Social sensitivity |

.730 |

.384 |

.148 |

.091 |

|

Openness |

.714 |

.090 |

.416 |

.265 |

|

Intercultural understanding |

.671 |

.245 |

.207 |

.298 |

|

Confidence |

.566 |

.038 |

.446 |

.427 |

|

Reducing social prejudices, experiencing intercultural interest in situ |

.255 |

.876 |

.033 |

.076 |

|

Experiencing an understanding and interest in volunteering in situ |

.210 |

.803 |

.001 |

.170 |

|

Trying out international volunteering in situ |

.249 |

.746 |

.258 |

.193 |

|

Placement, career opportunities |

−.104 |

.700 |

.326 |

.114 |

|

Life and professional experiences |

.316 |

.540 |

.012 |

.378 |

|

Communication skills |

.282 |

.031 |

.833 |

.216 |

|

Language skills |

.242 |

.218 |

.806 |

.042 |

|

Social involvement |

.434 |

.390 |

.577 |

.014 |

|

Self-awareness, mental development, and development of personal identity |

.284 |

.223 |

.210 |

.811 |

|

A change in attitude toward life |

.269 |

.295 |

.064 |

.797 |

The bold numbers indicate which component the variables (items) load most strongly on

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization

Ab, Abilities; Exp, Experiences; SI, Skills and involvement; and SPRD, Spiritual development

Rotation converged in six iterations

To evaluate differences in the perception of the benefit factors (in recipient communities and in personal development of volunteers) based on the time spent out as a volunteer, the age and education level at the time of volunteering, the respondent's gender, and financial situation were examined using variance analysis. The analysis of variance did not find any significant differences in the assessment of the factors among the respondent groups, which were determined on the basis of volunteering and volunteers' characteristics.

Conclusions

Regarding RQ1 and RQ2, one of the most significant results of the research was that majority of the Hungarian public does not know international volunteering. Factor analysis revealed differences in the opinion of respondents’ segments according to previous domestic volunteering experience, university degree, and gender. More than 30% (32,2%) of former domestic volunteers knew international volunteering compared to that of 16,6% of the population without domestic volunteering experience. The differences were less but people with university degree, and females were aware of it in higher ratio. This equals the demographic profile of a typical international volunteer being female in 60–70% and with university degree in 75–9%.Footnote 3

Despite the relative low level of information, every segment agreed that both the awareness and the benefits of international volunteering should be strengthened, and young Hungarians should be encouraged to try overseas volunteering.

The results proved the statements of international literature about the strong and causal correlation between domestic and international volunteering (Baillie Smith & Laurie, Reference Baillie Smith and Laurie2011; Wu, Reference Wu2011). In this study, respondents with domestic volunteering experience were more informed, had more positive and supportive opinion, and were more willing to try international volunteering compared to the rest of the population with no similar past.

As to the effects of international volunteering, respondents (regardless of the examined segments and demographic background) considered the benefits on the skills and identity of the volunteers as the most significant. It is also in harmony with the results of international research as introduced in the literature review (Brown, Reference Brown2018; Lough, Reference Lough2008; Wuthnow, Reference Wuthnow1995). Negative effects received the lowest scores that support that literature observation that empirical studies examine largely the positive benefits of international volunteering and remain oblivious to the difficulties and drawbacks (Tian & McConachy, Reference Tian and McConachy2021).

As to the experiences of returned international volunteers (RQ3 and RQ4), their structure of motivation bore strong similarity to those of other cases of research. The Hungarian respondents named desire for adventure/travel, willingness to help, cultural curiosity, and the personal development as their main motives. It supports the motivation theory of Hustinx and Lammertyn (Reference Hustinx and Lammertyn2003) that says that besides altruism the personal motivations of the participants are equally important. Hungarian volunteers’ motivational background is very similar to international patterns.

Critical theories of volunteerism (Schech & Mundkur, Reference Schech and Mundkur2017) warn that when volunteers do not get proper intercultural preparation than they can risk the success of the whole humanitarian mission. Nearly 60% of the respondents participated in preparation training prior to volunteering, and regarding the training’s usefulness, the highest satisfaction rate was given to intercultural sensitization and conflict-management topics. In general, Hungarian respondents did not report any significant problems or difficulties during volunteering. It can be the positive consequence of the proper preparation training and conscious attitude, or—in line with the positivist theory of Tian and McConachy, (Reference Tian and McConachy2021)—they just did not want to mention any negative sides.

The research adds value to international volunteer research in several areas. As discussed earlier, international volunteering is a significantly under-researched area (Lough et al., Reference Lough, McBride and Sherraden2009). Therefore, the knowledge and awareness of Hungarian society about international volunteering and the experiences of returning volunteers not only contribute to the global research environment, but also provide particularly useful insights for understanding the situation in Central and Eastern European countries without a volunteering history.

One of the assumptions of the research has been confirmed, i.e., that the Hungarian social environment is not aware/knows little about international volunteering. However, their perceptions of volunteering were surprisingly accurate, both in terms of its roles and benefits. The findings of both the wider public and the returned volunteers were typically in line with those of other international research.

The research also confirmed the correlation between domestic and international volunteering, which, given Hungary's strong emphasis on strengthening domestic volunteering, is encouraging for the expected increase in international volunteering activity and, in a broader context, humanitarian development that provides the framework for volunteering. At a geopolitical level, this suggests that Central and Eastern European countries will shift from recipient status to aid donor status in the future.

This study presents many benefits of international volunteering for Hungary (or any other donor country). Due to the relatively low number of volunteers and lack of knowledge in the public, these potential advantages are yet to be used. Policy-makers should, therefore, increase its awareness and make international volunteering popular in the whole society. More efforts should be added to link international volunteering with domestic volunteering that already has an established awareness and reputation.

One of the limitations of this study was the sampling method. Non-probability (convenience) sampling was used; therefore, this research can consider as a pilot study with non-generalizable results. Nationwide representative research would still add to the reliability of the results. It would also be worthwhile to expand the research to other Central and East European countries as well, to see in a comparative way how respondents (former volunteers and those who have not tried it before) from different societies/cultures feel about the role of international volunteering, and how those who have volunteered evaluate the difficulties and benefits of their volunteer activities.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Budapest University of Economics and Business.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

We wish to confirm that there are no competing interests, there has been no financial or non-financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication.