Introduction

It is increasingly acknowledged that perceptions of procedural and substantive fairness matter for citizens’ evaluations of domestic politics and policies (e.g., Becher & Brouard, Reference Becher and Brouard2022; Frey et al., Reference Frey, Benz and Stutzer2004; Juhl & Hilpert, Reference Juhl and Hilpert2021; Stantcheva, Reference Stantcheva2021). However, we know less about the role of fairness evaluations in polities that stretch beyond the nation state (exceptions include Bechtel et al., Reference Bechtel, Scheve and Van Lieshout2022; Bernauer et al., Reference Bernauer, Mohrenberg and Koubi2020; Hahm et al., Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2020; Tallberg & Zürn, Reference Tallberg and Zürn2019). For instance, the literature on support for European integration and the European Union (EU) distinguishes utilitarian, identity‐related, as well as cue‐taking and benchmarking approaches (Hobolt & de Vries, Reference Hobolt and De Vries2016). But we know less about whether and to what extent normative considerations come into play when citizens evaluate EU integration and EU policies. In this article, we investigate public support for differentiated integration (DI), to better understand how citizens trade off fairness and utility considerations.

DI constitutes a promising test ground for such a purpose. Defined as an ‘incongruence between the European Union's […] territorial extension and its rule validity’ (Holzinger & Schimmelfennig, Reference Holzinger and Schimmelfennig2012, p. 292), DI has been criticized, on the one hand, for inviting member states to ‘cherry‐pick’ integration benefits, thereby undermining the cohesion of the EU. On the other hand, DI has been associated with the exertion of dominance by a core of states over an internal or external EU periphery (Eriksen, Reference Eriksen2018). This latter critique relates to ‘capacity DI’, which excludes those (member) states from cooperation, that are considered unfit or ‘not yet ready’ to participate (Winzen, Reference Winzen2016). At the same time, DI has been appraised for its potential to safeguard national sovereignty and autonomy. In particular ‘sovereignty DI’ (Winzen, Reference Winzen2016), which allows member states to opt out from, in their perspective, all too ‘intrusive’ EU policies, has been considered a democracy‐enhancing tool (cf. e.g., Bellamy et al., Reference Bellamy, Kröger and Lorimer2022).

Echoing the theoretical literature, empirical research on public support for DI has found that citizens care about two dimensions when forming their preferences for DI. First, they consider the consequences of differentiation for the EU polity and its capacity to act; second, they take into account DI's impact on the national autonomy of the member states (Schuessler et al., Reference Schuessler, Heermann, Leuffen, De Blok and De Vries2023). Depending on their general EU support and their attachment to their member state, citizens weigh these two dimensions differently. Moreover, previous research suggests that citizens consider how their home country would be affected when evaluating a DI proposal (Leuffen et al., Reference Leuffen, Schuessler and Gómez Díaz2022).

In this article, we harness the tension between national and European interests experimentally to better understand how citizens trade off sociotropic national utility and fairness considerations. Does public support for differentiation decrease if citizens consider a DI proposal to be dominating, rather than autonomy‐enhancing? And do citizens primarily care about the effects of DI on their own member state, or do they also consider the effects of DI on other member states? If forms of differentiation are opposed even though they do not negatively affect a citizen's member state, we take this as evidence in support of the claim that norms may matter for the evaluation of EU policies.

In terms of theory, we build on the normative literature on DI, and in particular on Lord's (Reference Lord2015; Reference Lord2021) seminal elaboration of the conditions under which DI can be judged as fair or unfair. Lord (Reference Lord2015) proposes to focus on the externalities of DI as a normative ‘standard that can be accepted by those who otherwise disagree about a range of other values that are affected by European integration’ (Lord, Reference Lord2015, p. 796). Given that the reduction of externalities between states represents the very raison d’être of the EU, Lord argues that any form of DI that reduces externalities should be welcomed. In contrast, DI is problematic if it creates new externalities. We also know that citizens in general consider the imposition of negative externalities on others as unfair (Fehr & Gintis, Reference Fehr and Gintis2007). We, therefore, argue that if norms matter in citizens’ assessment of the EU, they should be opposed to DI proposals that produce externalities, irrespective of their own (member state's) exposure to them. By contrast, in a rationalist reading, citizens should not care about negative externalities imposed on others.

Previous public opinion research has simply asked citizens about their support for different forms of DI in the abstract, without specifying how it would affect them or their home country (e.g., De Blok & De Vries, Reference De Blok and De Vries2023; Leuffen et al., Reference Leuffen, Schuessler and Gómez Díaz2022; Moland, Reference Moland2024). To overcome this problem, we conduct a factorial survey experiment in eight EU member states.Footnote 1 Specifically, we assess citizens’ support for DI proposals using a vignette design, in which we vary (I) the externalities of the DI initiative (no/positive/negative externalities) and (II) the affectedness of the survey respondent's home country. Moreover, the vignette includes (III) an attribute capturing procedural fairness; in particular, we inform respondents about whether those member states, which would not participate in a proposed policy, approve or disapprove of the other states moving ahead. In addition, our vignette design controls for (IV) the reasons to opt for differentiated instead of uniform integration (we distinguish a capacity and a sovereignty DI scenario), as well as for (V) different policy areas.

Our findings highlight that citizens, indeed, display strong ‘allergic’ reactions to negative externalities, independent of their own affectedness. In contrast, we do not find an effect for positive externalities. It thus seems that negative externalities in particular are considered to be unfair and a sign of dominance to be avoided in the EU. This finding goes against a rationalist reading according to which negative externalities imposed on others should not be a problem. Thus, negative externalities constitute a clear and unifying red line for differentiation in the EU, nuancing previous evidence in favour of quite high levels of overall support for DI. Against our expectations, we do not find that the approval of member states, which do not participate in a DI proposal, enhances support for such a measure. Apparently, citizens are less responsive to national sensitivities when these hinder the cooperation of a majority of states. The opposition against negative externalities, however, underlines that they value fair cooperation in the EU; even at the price of losing out on short‐term national utility.

This article brings together different, hitherto largely detached strands from the EU literature, namely political theory, integration theory and political sociology; especially normative political theory has remained somewhat detached from the mainstream integration literature (Bellamy & Attucci, Reference Bellamy, Attucci, Wiener and Diez2009). We thus hope that our research can modestly contribute to developing a new research agenda about the role of fairness norms and citizens’ support for the EU, other international organizations and their policies.

The article is structured as follows: Starting from the observation that we still lack knowledge about whether and how norms and fairness perceptions impact citizens’ support of policies beyond the nation state, we introduce DI as a suitable testing ground for exploring the fairness‐integration support nexus in the EU. We then develop our theoretical argument bringing together the literature on public support for European (differentiated) integration and normative‐theoretical accounts of DI. Subsequently, we present our research design and our data. We present our empirical findings in the results section. The discussion and conclusion summarize and critically discuss the results, taking both substantive and methodological caveats into account.

Fairness, dominance and autonomy in the EU

Inspired by a rich literature in social psychology and behavioural economics (e.g., Alesina & Angeletos, Reference Alesina and Angeletos2005; Bowles & Gintis, Reference Bowles and Gintis2000; Falk et al., Reference Falk, Fehr and Fischbacher2008; Fong, Reference Fong2001; Henrich et al., Reference Henrich, Ensminger, Mcelreath, Barr, Barrett, Bolyanatz, Cardenas, Gurven, Gwako, Henrich, Lesorogol, Marlowe, Tracer and Ziker2010; Kahneman et al., Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler1986; Tyler, Reference Tyler2000), political science has increasingly acknowledged and investigated the trade‐off between rational utility maximization and fairness in political decision making (e.g., Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Robinson and Torvik2013; Becher & Brouard, Reference Becher and Brouard2022; Frederiksen, Reference Frederiksen2022; Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Juhl & Hilpert, Reference Juhl and Hilpert2021; Stantcheva, Reference Stantcheva2021). While there is growing evidence that fairness matters in international politics as well (e.g., Bechtel & Scheve, Reference Bechtel and Scheve2013; Efrat & Newman, Reference Efrat and Newman2016; Kertzer & Rathbun, Reference Kertzer and Rathbun2015), we still know little about how fairness impacts public support for international organizations. The EU, in this respect, is not an exception. The EU literature commonly distinguishes utility‐oriented, identity‐related as well as cue‐taking and benchmarking mechanisms to account for public support for European integration (see Hobolt & De Vries, Reference Hobolt and De Vries2016 for a review). In no way disputing the importance of this triad, we contend that norms and fairness considerations may, additionally, contribute to shaping public opinion in the EU.

It is widely acknowledged that the EU today again stands at a crossroads. The Russian attack on Ukraine of February 2022 has laid bare the political and functional pressures for the EU's continued deepening and widening. At the same time, given high levels of politicization, public opinion has been identified as a significant constraint on further integration (De Vries et al., Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Walter2021; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2009). Therefore, there is a continuous need to understand what shapes public support for European integration. In fact, moving beyond the question of whether citizens consider the EU a good or a bad thing, it is important to learn more about what kind of EU the citizens want (cf. Fabbrini, Reference Fabbrini2015). How should the relationship between the centre and the member states, as the constitutive units, and the relationships between the different member states be organized?

It is with respect to these relationships that fairness comes into play. When the EU is considered a community of liberal democratic states (Schimmelfennig, Reference Schimmelfennig2003), conceptualized by some as a ‘demoi‐cracy’ (Cheneval & Schimmelfennig, Reference Cheneval and Schimmelfennig2013; Nicolaïdis, Reference Nicolaïdis2013), domination by the centre of the parts and between the member states should be categorically excluded. Likewise, any domination by individual member states, or a group thereof, of the Union, for example, by violating core community norms or by hindering the EU's action capacity, could be considered a breaching of associative obligations, accepted through membership of the EU. While the role of citizens in evaluating the EU's legitimacy has increasingly been acknowledged in recent years (Hobolt & De Vries, Reference Hobolt and De Vries2016; Malang, Reference Malang2017), we know less about whether fairness considerations matter for citizens’ evaluations of the EU and its policies.

Fairness and public support for European integration

Traditionally, public opinion research has highlighted the role of utilitarian and identity‐related explanations for EU support. Utility‐oriented theories concentrate on egotropic and sociotropic (national or regional) benefits from European integration, the common market and the Euro currency (e.g., Anderson & Reichert, Reference Anderson and Reichert1995; Banducci et al., Reference Banducci, Karp and Loedel2009; Gabel, Reference Gabel1998; Gabel & Palmer, Reference Gabel and Palmer1995; Hobolt & Wratil, Reference Hobolt and Wratil2015).Footnote 2 Identity‐related theories of EU support point to the limits of utilitarian explanations, highlighting instead different levels of attachment to the nation state and dispositions such as cosmopolitanism and altruism (e.g., Bechtel et al., Reference Bechtel, Hainmueller and Margalit2014; Hooghe & Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2005; Kuhn et al., Reference Kuhn, Solaz and Van Elsas2018).

Like identity, fairness norms might moderate utility considerations. For example, recent research on European solidarity and risk‐sharing in times of crisis shows that policy design choices, such as procedures that ensure reciprocal solidarity, influence public support for costly and redistributive EU policies (e.g., Baute & de Ruijter, Reference Baute and De Ruijter2021; Beetsma et al., Reference Beetsma, Burgoon, Nicoli, De Ruijter and Vandenbroucke2022; Bremer et al., Reference Bremer, Kuhn, Meijers and Nicoli2023; see also Bechtel & Scheve, Reference Bechtel and Scheve2013 for the global level). Meanwhile, studies on public preferences over institutional and decision‐making rules (Hahm et al., Reference Hahm, Hilpert and König2020; Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Treib and Schlipphak2023), have largely neglected fairness as an explanatory factor. To account for this shortcoming, in the following, we test how utility and fairness considerations interact in the case of differentiated integration.

The case of differentiated integration

In this article, we use DI as a testing ground to inspect whether citizens take norms and fairness considerations into account when forming their attitudes about the EU, its policies and future integration. DI has been understood as ‘a concept, a process, a system or a theory’ (Leruth & Lord, Reference Leruth and Lord2015), and its study has tremendously increased and matured in recent years (cf. e.g., Leruth et al., Reference Leruth, Gänzle and Trondal2022; Schimmelfennig et al., Reference Schimmelfennig, Leuffen and De Vries2023). DI refers to ‘an incongruence between the European Union's (EU) territorial extension and its rule validity’ (Holzinger & Schimmelfennig, Reference Holzinger and Schimmelfennig2012, p. 292) and is generally understood as an instrument to overcome heterogeneity‐induced gridlock in an EU (Stubb, Reference Stubb2002) composed of, today, 27 highly diverse member states.

At the same time, DI has raised a number of normative concerns. At the more critical end of the normative spectrum, Fossum (Reference Fossum2015) and Eriksen (Reference Eriksen2018; Reference Eriksen2019) have linked differentiation to dominance and a hollowing out of democracy. In particular, these authors are concerned about a lack of democratic oversight – highlighting, for example, the diminished role of the European Parliament in the response to the Eurozone crisis – and the exclusion of countries from decision‐making processes. While the latter argument focuses specifically on external DI (i.e., the selective participation of third countries in EU policies), there is also the worry that member states are arbitrarily excluded from common policies. This critique primarily concerns ‘capacity DI’ (Winzen, Reference Winzen2016), as in this form member states may be excluded from policies against their will. An example for capacity DI, considered to be unfair by some observers, is the ongoing exclusion of Romania and Bulgaria from the Schengen area; for instance, Romania's President Klaus Iohannis once called an Austrian veto against Romania's accession to the Schengen zone ‘inexplicable, regrettable and unjustified’ and ‘profoundly unfair for our country and Romanian citizens’.Footnote 3 Likewise, Ulceluse (Reference Ulceluse2022) described the treatment of Romania and Bulgaria in late 2022 as ‘discriminatory’ and ‘deeply unfair’.

In contrast, Bellamy and Kröger (Reference Bellamy and Kröger2017) and Bellamy et al. (Reference Bellamy, Kröger and Lorimer2022) have acknowledged the empowering potential of DI. Drawing a comparison to the protection of ethnic minorities in nation states, they argue that DI can protect the member states’ autonomy and avoid a tyranny of the majorities (Bellamy et al., Reference Bellamy, Kröger and Lorimer2022, pp. 13–14, 51). DI thus strengthens the EU's ‘republican’ profile (cf. Leuffen, Reference Leuffen and Fromage2024; Pettit, Reference Pettit2012). Opt‐outs, for example, protect national sovereignty from integration steps which lack domestic popular support. The downside of ‘sovereignty DI’ (Winzen, Reference Winzen2016), however, may consist in a weakening of the EU; in particular, if centrifugal forces become too strong (Kölliker, Reference Kölliker2001).

An important normative benchmark has been put forward by Lord (Reference Lord2015, Reference Lord2021), who proposed to focus on the externalities of DI as a normative ‘standard that can be accepted by those who otherwise disagree about a range of other values that are affected by European integration’ (Lord, Reference Lord2015, p. 796). According to this interpretation, DI is desirable if it contributes to the reduction of externalities between member states. Conversely, DI becomes problematic, if it creates new externalities between states. And, indeed, DI can produce both negative, as well as positive externalities (Kölliker, Reference Kölliker2001). In the case of negative externalities, states that do not participate in a DI policy are left worse off. We call this ‘type I dominance’. In the case of positive externalities, the non‐participating states are invited to free‐ride on the achievements of the further integrated group. We call this ‘type II dominance’.

Bellamy et al. (Reference Bellamy, Kröger and Lorimer2022) propose a slightly more conservative position concerning externalities. Echoing the weak Pareto criterion, these authors argue that to be substantively fair, DI should leave no member state worse off (Bellamy et al., Reference Bellamy, Kröger and Lorimer2022, p. 16). Fully in line with Lord (Reference Lord2015; Reference Lord2021), they find that the imposition of negative externalities on member states constitutes a red line for DI. Accordingly, we expect that citizens are less supportive of DI policies, which create negative externalities (H1). However, Bellamy et al. (Reference Bellamy, Kröger and Lorimer2022) are less worried about positive externalities. In contrast, when following Lord (Reference Lord2015)’s free‐riding argument, one can additionally hypothesise that citizens also react negatively to the occurrence of positive externalities (H2).

H1: When DI is linked to negative, rather than to no externalities, citizens are less likely to support a DI initiative.

H2: When DI is linked to positive, rather than to no externalities, citizens are less likely to support a DI initiative.

If we find empirical support for H1 and H2, or at least for the less controversial H1, we will cautiously interpret this as first evidence that citizens, indeed, engage in normative reasoning when asked to evaluate DI. This would bring in fairness to the growing literature on public support for DI (De Blok & De Vries, Reference De Blok and De Vries2023; Leuffen et al., Reference Leuffen, Schuessler and Gómez Díaz2022; Malang & Schraff, Reference Malang and Schraff2023; Moland, Reference Moland2024; Schuessler et al., Reference Schuessler, Heermann, Leuffen, De Blok and De Vries2023; Telle et al., Reference Telle, De Blok, De Vries and Cicchi2022; Vergioglou & Hegewald, Reference Vergioglou and Hegewald2023; Winzen & Schimmelfennig, Reference Winzen and Schimmelfennig2023).

So far, we assumed that citizens take a neutral stance with respect to how they, or – in a sociotropic understanding (cf. Anderson & Reichert, Reference Anderson and Reichert1995; De Vries, Reference De Vries2018) – their home country would be affected by DI. However, in a rationalist reading (Downs, Reference Downs1957; Riker, Reference Riker1980), citizens do not care about externalities, as long as they themselves are not negatively affected by these externalities. For example, recent studies on the role of democratic norms in domestic politics suggest that voters’ partisan and material interests might trump norm‐related concerns (e.g., Acemoglu et al., Reference Acemoglu, Robinson and Torvik2013; Graham & Svolik, Reference Graham and Svolik2020). If DI can bring about winners and losers, citizens might anticipate, whether their country is likely to profit or suffer from a DI proposal. Indeed, previous research has interpreted regional variation in DI support along these lines. For instance, Leuffen et al. (Reference Leuffen, Schuessler and Gómez Díaz2022) linked patterns of support for a ‘multi‐speed Europe’ to the effects of the Eurozone crisis; in particular, citizens in Southern Europe appear to be concerned about being ‘left behind’. Similarly, the persistent exclusion from the Eurozone and the Schengen area seems to have soured public attitudes in Bulgaria and Romania towards both DI, and European integration more generally (Vergioglou & Hegewald, Reference Vergioglou and Hegewald2023; Winzen & Schimmelfennig, Reference Winzen and Schimmelfennig2023).

Extant research could only guess from regional patterns that citizens’ perceptions of their country's affectedness shaped their stance towards different types of DI. In contrast, our experimental setup enables us to explicitly test how perceptions of their home country's affectedness impacts their attitudes. Theoretically, we expect citizens to become more critical towards DI, if they are informed that their state will suffer from DI‐related externalities, either by having to bear negative externality costs (H3), or by suffering from other states’ free‐riding (H4).Footnote 4

H3: Citizens from non‐participating states are less supportive of a DI initiative when it produces negative externalities but are more supportive of the initiative when there are positive externalities.

H4: Citizens from participating member states are less supportive of the initiative when there are positive externalities but are more supportive of a DI initiative when it produces negative externalities.

Bellamy et al. (Reference Bellamy, Kröger and Lorimer2022, p. 16; 47) classify the (external) effects of DI as a matter of substantive fairness. However, the fairness of DI may not only be determined by the effects of DI but also by the process in which DI is agreed upon. According to Bellamy et al. (Reference Bellamy, Kröger and Lorimer2022, p. 16; 46), to be procedurally fair, DI should be agreed in consultation with the non‐participating states. Indeed, the EU's political culture generally puts great emphasis on the respectful appreciation of other member states’ concerns, as highlighted in the Council's culture of consensus (Heisenberg, Reference Heisenberg2005; Lewis, Reference Lewis2005). From the perspective of procedural fairness, citizens’ approval of DI could therefore be affected by whether or not the non‐participating states approved of the others moving forward; assuming that disapproval signals that some actors would consider such a DI measure as inappropriate. Correspondingly, citizens could be more supportive of DI if the non‐participating states do not object to differentiation. H5 therefore expects that if the non‐participants object, public support is likely to decrease.

H5: If the non‐participating minority group objects to DI, citizens’ support thereof is likely to decrease.

Previous research has found that EU support and European identity have a strong influence on citizens’ attitudes towards different forms of DI (De Blok & De Vries, Reference De Blok and De Vries2023; Moland, Reference Moland2024; Schuessler et al., Reference Schuessler, Heermann, Leuffen, De Blok and De Vries2023). In particular, these studies have shown that EU supporters are more supportive of temporary capacity DI, while Eurosceptics are more favourable to permanent sovereignty DI. To explore potential heterogeneous treatment effects, we conduct subgroup analyses for EU supporters and Eurosceptics. However, we see no clear theoretical reason why EU supporters or opponents should respond differently to substantive or procedural fairness concerns. While EU supporters may value norms of fairness in a political community they appreciate, Eurosceptic discourse is itself strongly concerned about member states being dominated either by Brussels or by their fellow member states.

Finally, there is a consensus among normative scholars that there must be no DI in the rule of law, which would undermine the very foundations of the community (Bellamy & Kröger, Reference Bellamy and Kröger2021; Kelemen, Reference Kelemen2019, Reference Kelemen2021). However, as DI in the rule of law is not an option in the DI choice set, we decided to not test for it experimentally. Otherwise, we do not have strong ex ante theoretical reasons for expecting variation in DI support across issue areas. To control for or explore whether DI preferences vary per concerned issue area, we include different policy areas in the vignettes, ranging from a common European refugee relocation scheme (Area of Freedom, Security and Justice) to a common European minimum wage (Social Europe), the creation of joint European military units (Common Foreign and Security Policy) and a common European tax for digital services (budget/own resources/taxation).

Research design

To test whether fairness considerations have an impact on citizens’ support for DI, we have designed a survey experiment integrating core concepts from the (normative) DI literature discussed above. Previous studies have relied on descriptive survey items asking respondents for their opinion on various forms of DI. However, in their daily lives, citizens are hardly confronted with the intricacies of DI and, given the speed with which respondents tend to answer online surveys, we can hardly expect them to ponder the different consequences of specific types of DI. Moreover, one important channel for the formation of political preferences, elite and party cues, are rather unlikely in the case of DI – at least beyond individual events, such as opt‐out referenda (cf. Schraff & Schimmelfennig, Reference Schraff and Schimmelfennig2020) – because parties themselves do not have stable and nuanced DI preferences (Kröger et al., Reference Kröger, Lorimer and Bellamy2021; Telle et al., Reference Telle, De Blok, De Vries and Cicchi2022).

Our approach to better understand how citizens evaluate DI consists of informing citizens in a vignette experiment about the consequences of DI (i.e., its externalities), the affectedness of respondents’ member state, the stances of non‐participating member states, as well as the type of DI (capacity vs. sovereignty) and the policy area in question. By assessing survey respondents’ support for these short, hypothetical DI proposals, we can disentangle how different proposal characteristics affect their preferences. Factorial survey or vignette experiments are well suited for assessing the ‘judgment principles that underlie social norms, attitudes, and definitions’ (Auspurg & Hinz, Reference Auspurg and Hinz2015; Jasso, Reference Jasso2006). By integrating an experimental design in a (public opinion) survey, this approach allows us to test causal hypotheses in a larger sample drawn from the general population, thereby increasing external validity. In this section we first give an overview of the public opinion survey in which we included our factorial experiment. We then present the experimental set‐up, before detailing the estimation strategy.

Data

Our factorial survey experiment was fielded as part of the ‘Comparative Opinions on Differentiated Integration’ survey (CODI), an original cross‐national online survey conducted in eight EU member states (Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands and Poland) in February and March 2021 (see Schuessler et al., Reference Schuessler, Heermann, Leuffen, De Blok and De Vries2023). The selected countries differ by size and by geographical location (East, North, South) and together represent close to two‐thirds of the EU population. In each country, the survey firm Respondi recruited around 1,500 respondents. This yields a total sample size of around 12,000. The survey used quota sampling aiming at representativeness with respect to national marginal distributions of age groups, gender and sub‐national regions. For the analysis of the factorial experiment, we perform model‐specific list‐wise deletion of observations with missing values, resulting in a final sample of 10,813 respondents.

Experimental set‐up

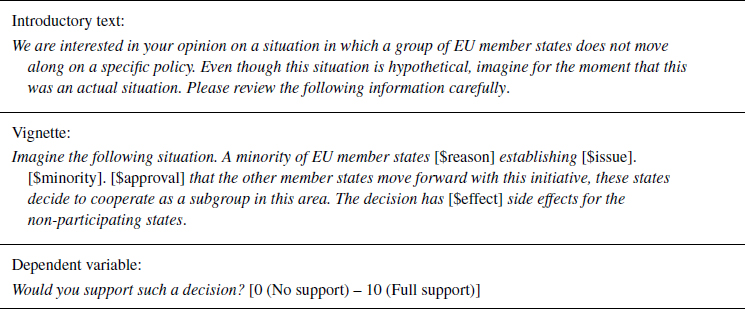

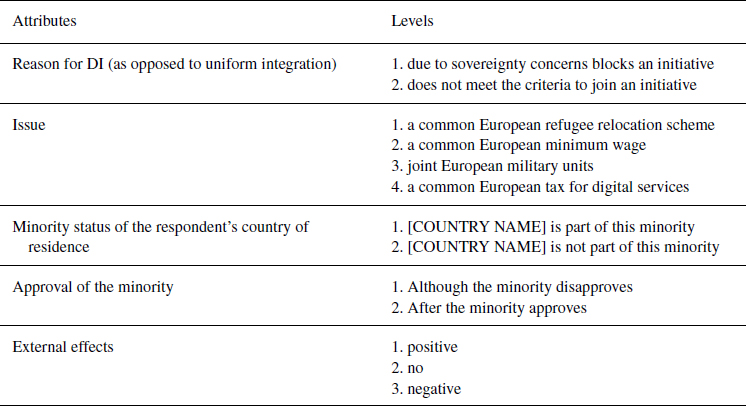

We presented each respondent with one multidimensional description (vignette) of a hypothetical DI initiative. Respondents are then asked whether they would support such an initiative. Support is measured on an 11‐point Likert scale (‘no support at all’ = 0; ‘strongly support’ = 10). The attributes (dimensions) of the vignettes are systematically varied, reflecting variations in the experimental stimuli, and randomly assigned to respondents (see Table 1). All attributes were evenly randomized across countries. The experiment therefore allows us to estimate the causal effects of situational attributes on the average support for a proposed DI initiative. Table 1 shows the vignette as presented to the respondents. Table 2 summarizes the five attributes and levels of the experiment.

Table 1. Experimental set‐up

Table 2. Vignette attributes and levels

The vignette seeks to translate the complex theoretical mechanisms of DI into jargon‐free, easy to understand language. Nevertheless, given that we include five attributes, the vignette might still be cognitively demanding for respondents, especially for those with lower levels of political knowledge. To account for this potential limitation, we conduct two subgroup analyses based on education levels on the one hand, and knowledge about the EU, on the other hand (see Supporting Information appendices A4 & A5).

The first attribute refers to the underlying reason – sovereignty or capacity – to opt for DI instead of uniform integration. Sovereignty DI takes place when a minority of EU member states blocks uniform integration ‘due to sovereignty concerns’. Capacity DI occurs when a minority ‘does not meet the criteria to join’ an integration step. The second attribute captures the policy issue in question: (1) a common European refugee relocation scheme, (2) a common European minimum wage, (3) joint European military units or (4) a common European tax for digital services. These issues have all featured prominently in political debates about future (differentiated) integration. They all concern ‘core state powers’, which are particularly salient for sovereignty concerns, making them likely cases of future DI (Winzen, Reference Winzen2016). The third attribute defines the status of the respondent's country of residence, that is, is the country part of the minority of member states, that would not participate in the DI policy, or would it be part of the majority of further integrating states. The fourth attribute expresses whether the non‐participating minority approves or disapproves of the fact that the other member states intend to integrate without them. Finally, the fifth attribute captures the expected externalities of the differentiated policy. External effects can have either a positive, a negative or no effect on the non‐participating EU member states. We deliberately do not use public goods theory to derive external effects from the different policy issues (cf. Lord, Reference Lord2021). DI externalities can be hard to understand for citizens and may be uncertain at the time DI is initiated. Moreover, politicians can frame DI effects in the political debate. We therefore simply make a statement about the expected effects of the hypothetical DI initiative. A shortcoming of this treatment is that it possibly bundles ‘objective’ information about externalities and (negative) framing effects (cf. Avdagic & Savage, Reference Avdagic and Savage2021; Rozin & Royzman, Reference Rozin and Royzman2001).

Method

To measure the effect of vignette attributes on support for the DI initiatives, we estimate ordinary least square (OLS) regression models including country fixed effects with robust standard errors clustered on the country level. The reference levels are: ‘Reason’ – does not meet the criteria, ‘issue’ – joint European military units, ‘minority’ – is not part of this minority, ‘approval’ – after the minority approves, ‘external effects’ – no. The ‘affectedness’ hypotheses 3 and 4 are tested using interaction effects between the ‘external effects’ attribute and the ‘minority’ attribute.

To test the influence of theoretically interesting respondent‐level characteristics, we perform subgroup analyses. To account for the role of general EU support, we divide the sample into two subgroups ‘EU supporters’ and ‘EU opponents’ based on the survey question ‘Generally speaking, do you think that [respondent's country's] membership of the EU is a good thing or a bad thing?’. EU supporters are those who answer that membership is ‘a good thing’, EU opponents are those who reply that membership is ‘a bad thing’. In the Supporting Information appendix we report additional subgroup analyses, based on an alternative specification of EU integration support (A3), identity (A6), political ideology (left/right self‐placement, A7) and EU region (North/East vs. South, A8).

Results

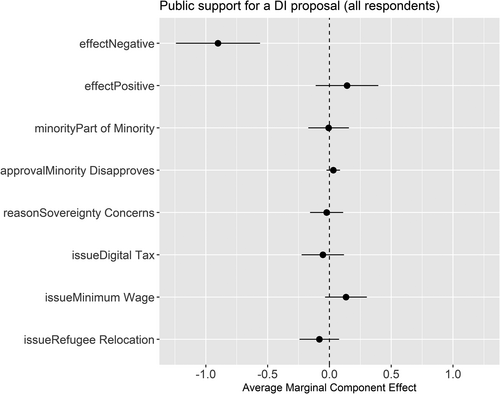

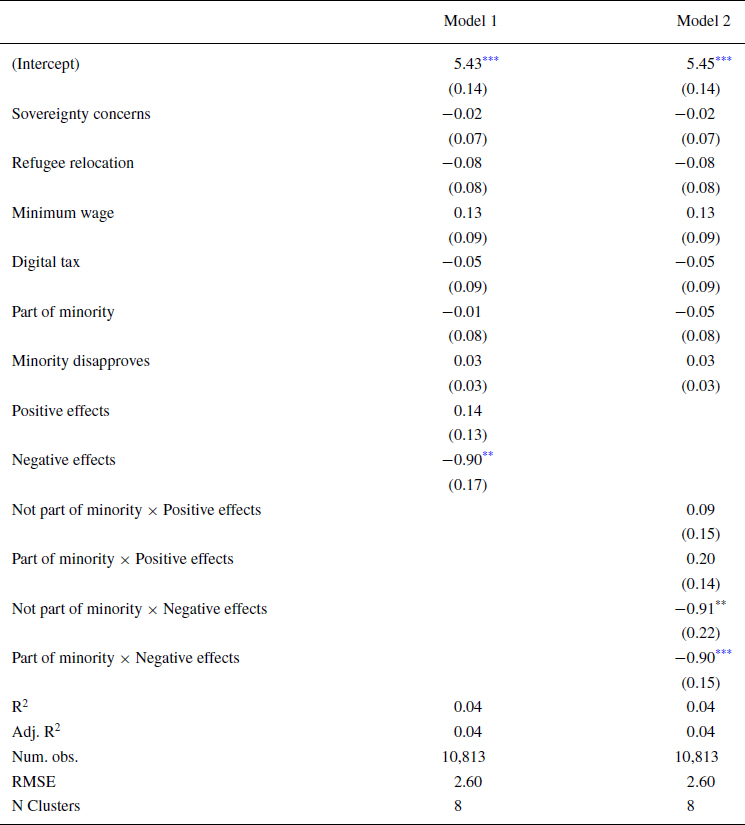

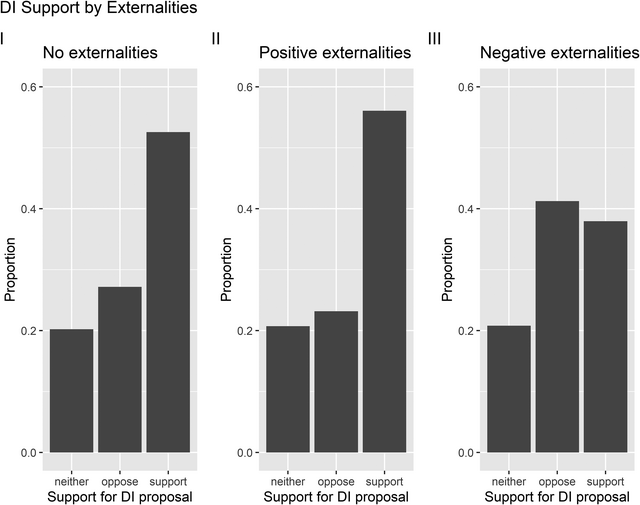

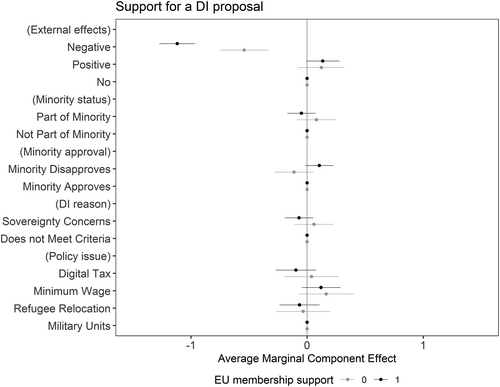

How do our experimental treatments affect public support for DI? Figure 1 shows the average marginal component effects for all respondents (see also Table 3, Model 1).Footnote 5 We find strong support for H1: If DI creates negative externalities for the non‐participating EU member states, this reduces public support significantly. Figure 2 illustrates this effect descriptively: Support for a DI proposal falls from above 50 per cent to below 40 per cent, while opposition to the proposal rises from less than 30 per cent to more than 40 per cent if the proposal entails negative externalities as compared to no externalities. This finding suggests that citizens care about the fairness of DI in the sense that DI should not be to the detriment of the non‐participating minority of member states (‘type I dominance’). In contrast, citizens seem to be less concerned with the problem of free‐riding (‘type II dominance’). The effect for positive externalities is positive but not statistically significant, disconfirming H2. Citizens therefore seem to follow Bellamy et al. (Reference Bellamy, Kröger and Lorimer2022)’s more conservative take of the externality question. Recall that while Lord (Reference Lord2015) problematizes the free‐riding risk, Bellamy et al. (Reference Bellamy, Kröger and Lorimer2022, p. 35) are less concerned about positive externalities, stressing that from a state‐centric perspective DI should be a Pareto improvement for all member states.

Figure 1. Average marginal component effects for all respondents (attribute order follows the order of the hypotheses).

Table 3. Effects of DI characteristics on DI support. Country fixed effects omitted.

* p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

Figure 2. Proportion of respondents supporting (opposing) a DI proposal, disaggregated to externalities treatment (on the 11‐point Likert scale, 1–4 = oppose; 5 = neither/nor, 6–10 = support).

That said, it might also be the case that respondents did not fully understand the free‐riding risks inherent in positive externalities. Admittedly, disentangling free‐riding can be cognitively demanding. By contrast, there was no such mental translation work necessary when it came to evaluating negative externalities. Moreover, as discussed in the research design section, the ‘negative externalities’ treatment might have also worked as a negative framing effect, further pushing respondents to oppose such DI proposals. However, despite the negative effect, we find that almost 40 per cent of respondents support DI proposals, which entail negative externalities (Figure 2). We discuss the methodological caveats in greater detail in the conclusion.

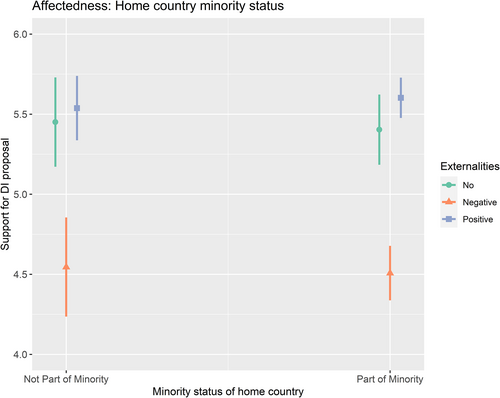

Turning to our affectedness hypotheses, Figure 3 plots the interaction effects between external effects and the DI status of the respondent's country of residence (see also Table 3, Model 2). We find similar patterns for citizens from participating and non‐participating member states. Negative externalities always lead to a drop in support, both when the respondent's home country takes part in the DI policy and when it doesn't. Positive externalities do not have a differentiated impact on public support, irrespective of the affectedness of the respondent's home country. We thus find partial support for H3 but reject H4. In short, citizens care about negative DI externalities for all member states. They are not exclusively focused on their own state's affectedness but care about fairness for all EU members. This refutes a strictly sociotropic reading of public support for DI.

Figure 3. Marginal effects of interactions between DI externalities and the minority status of respondents’ country of residence.

Moving from substantive to procedural fairness, in our experiment it does not seem to matter to citizens whether non‐participating member states approve or disapprove of the other states’ choice to engage in DI, disconfirming H5. Contrary to our expectations, this finding appears to go against the EU's culture of consensus. A possible explanation for this result could be that citizens think that integration‐friendly member states should not be held back by those states that do not want to integrate more or do not yet have the capacity to do so.

Finally, there is no variation in DI support across different policy areas in the overall sample, nor is there a statistically significant difference in public support for sovereignty DI as compared to capacity DI.

As previous research has shown that EU supporters and opponents prefer different types of DI (De Blok & De Vries, Reference De Blok and De Vries2023; Schuessler et al., Reference Schuessler, Heermann, Leuffen, De Blok and De Vries2023), we conduct a subgroup analysis for citizens who support or oppose their country's EU membership (Figure 4). While DI support is higher among EU supporters than among EU opponents (see marginal means plot in Supporting Information Appendix A2), we find very little in terms of heterogeneous treatment effects. Contrary to previous findings, we do not detect a statistically significant difference in support for capacity versus sovereignty DI between these groups. What we do find, however, is that EU supporters react more strongly to negative externalities than EU opponents. While negative externalities reduce DI support in both groups, the effect is significantly stronger for pro‐Europeans. We do not find such a difference for positive externalities. Thus, while both Eurosceptics and EU supporters share a concern about negative externalities, the latter are more strongly repulsed by this type of fairness violation (‘type I dominance’). Moreover, this differential finding strengthens our confidence that the effect of negative externalities can not be solely attributed to a negative framing effect.

Figure 4. Heterogeneous treatment effects for EU supporters and EU opponents (EU membership is a good thing = 1, EU membership is a bad thing = 0).

Conclusion

The question whether the ‘opprobrium attached to unfairness imposes constraints on profit seeking’ (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2012, p. 306), has been asked before, and it is usually confirmed. In this article, we explore whether fairness considerations also matter for citizens’ evaluations of EU policies. In particular, we test experimentally, under what conditions European citizens support or oppose DI. Our analysis identifies a clear red line for differentiation. Public support for a DI proposal strongly decreases when it entails negative externalities for the non‐participating member states. Importantly, this result holds irrespective of the affectedness of respondents’ home country. In other words, there is no ‘affectedness bias’ when it comes to DI externalities. In our setting, fairness concerns therefore seem to prevail over a sociotropic utility‐maximizing perspective.

This finding has implications for the use of DI to circumvent the veto power of individual member states. While we find that the disapproval of the non‐participating member states does not by itself reduce public support for a DI initiative, the externality structure of DI sets a limit to what citizens consider to be ‘fair differentiation’. By contrast, we find no statistically significant effect for positive externalities. From a normative point of view, positive external effects might arguably be somewhat less problematic compared to negative externalities (Bellamy et al., Reference Bellamy, Kröger and Lorimer2022). However, they are not unproblematic given the risk of free‐riding behaviour by DI outsiders (Lord, Reference Lord2015, Reference Lord2021). A caveat of our study is that we did not directly confront survey respondents with the risk of free‐riding but only with the presence or absence of positive external effects. Respondents might not have linked positive externalities to free‐riding behaviour. It would thus be premature to conclude that citizens do not care about free‐riding among EU member states. Future research should make the free‐riding risk and its implications clearer.

While our assessment relies on experimental results, it cannot be excluded that our research design may have led to biases amongst the survey respondents. In particular, we cannot disentangle whether the effect of negative externalities is due to the information per se or (also in part) due to negative framing effects (cf. Amsalem & Zoizner, Reference Amsalem and Zoizner2022). In particular, given that survey respondents typically react more strongly to negative as compared to positive frames (e.g., Avdagic & Savage, Reference Avdagic and Savage2021; Rozin & Royzman, Reference Rozin and Royzman2001), our respondents, too, might have adversely responded to the term ‘negative side effects’. At the same time, we feel confident that the strength of opposition to ‘negative externalities’ detected by our experiments cannot simply be reduced to rhetorical pitfalls. Moreover, we find that EU supporters react even more negatively to this treatment as compared to Eurosceptics. This heterogeneous treatment effect suggests that a potential negative framing effect does not override all political attitudes. In other words, citizens with different political preferences evaluate negative externalities differently. Finally, the fact that proposed integration in highly salient issues like refugee relocation and minimum wages did not move opinions, suggests that it is something about externalities as such that triggered respondents. When designing the experiments, we had to walk a tightrope between translating complex theories into vignettes that can intuitively be grasped by ‘normal’ citizens, without however, sacrificing the complexities inherent in DI. While we aimed at avoiding jargon as much as possible, we still may have lost some respondents by confronting them with too many details or technicalities.

The consideration of externalities is crucial for the normative evaluation of DI and of its consequences for the cohesion and legitimacy of the EU (Bellamy et al., Reference Bellamy, Kröger and Lorimer2022; Lord, Reference Lord2015). While our experiment provides a first indication that negative externalities influence citizens’ support for DI, future research should consider the methodological concerns discussed above. In particular, future studies should operationalize positive and negative externalities in ways that are neither too cognitively demanding nor create negative framing effects that evoke impulsive responses.

DI has been and continues to be a mechanism to reconcile a deepening and widening of European integration. As international crises create geopolitical and functionalist pressures for both, it is important to understand how citizens evaluate DI. This article is the first to experimentally investigate public support for DI. Moreover, it combines public opinion research with the normative literature on DI in an innovative fashion. By empirically investigating how citizens apply the ‘externality standard’ proposed by Lord (Reference Lord2015), it provides valuable empirical insights for the on‐going normative and theoretical debates about DI and European integration more generally.

DI is an ideal testing ground to investigate how citizens trade off utility and fairness concerns in international cooperation. The article thus speaks to a broader debate on utility versus fairness and (democratic) norms. By studying public attitudes towards externalities in a specific international setting, it cautiously shows that citizens seem to take fairness seriously in international agreements and are not only concerned with national self‐interest. While our experimental design zoomed in on a specific case of international cooperation in the context of the EU, our findings may inform future research into the determinants of public support for international institutions, more generally.

Acknowledgements

We thank the three anonymous reviewers and the editor for their valuable comments which helped us to significantly improve the article. Earlier versions of this article have been presented at the EU3D Workshop at the Jean Monnet House in Bazoches‐sur‐Guyonne in April 2022, the EUSA Conference 2022 in Miami, the ECPR SGEU Conference 2022 in Rome, the WPSA Conference 2023 in San Francisco and the DVPW Sektionstagung IB 2023 in Friedrichshafen. We are grateful to all discussants and participants, in particular, to John Erik Fossum and Christopher Lord, for their comments and support. The data collection was conducted together with Lisanne De Blok and Catherine De Vries, and our research was generously supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement 822419.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Online Appendix