Introduction

According to a remarkable story in the Babylonian Talmud (b. Qidd. 81a–b), a figure named Pelimo regularly recited the formula “An arrow in Satan’s eye!”Footnote 1 This caught the attention of none other than Satan himself, who, in response, disguises himself as a pauper and takes advantage of Pelimo’s generosity to enter his house. After wreaking havoc, Satan reveals himself and admonishes Pelimo about his daily recitation. Pelimo asks Satan how else to repel him, and Satan advises Pelimo to recite a version of Zech 3:2, “The Merciful rebuke Satan!”

The sensational nature of the story—a direct confrontation between a man and Satan—has inspired subsequent adaptations and retellings, including in early twentieth-century Hebrew literature and modern American cinema.Footnote 2 It has likewise elicited many scholarly interpretations. Typically, these approach the story as a foundational moral tale, regarding the figures and their dialogue as fundamentally “metaphorical” and intended to convey a broader didactic message about human behavior.Footnote 3 Satan is “symbolic” of what a culture deems its opposite.Footnote 4 Different explanations have been offered for the story’s didactic message, ranging from a critique of Pelimo’s personal hubris or his lackluster hospitality. To others, the moral of the story is that “Satan” —figurative of one’s internal desires —is simply unconquerable without God’s help.Footnote 5 In short, “Satan” in the story is either a divine figure exacting punishment for misdeeds, or a personification of Pelimo’s “inner demons.”Footnote 6 The formula recited by Pelimo and the alternative offered by Satan are not in themselves meaningful, but somehow emblematic of the larger underlying values contested in the story.Footnote 7 Pelimo’s daily recitation and Satan’s alternative of Zech 3:2 represent the character development that Pelimo supposedly undergoes from the opening to the conclusion of the story.

According to these interpretations, the story contemplates the virtues and characteristics of humankind; it is therefore not, we are told, “enslaved” to its “historical or sociological context.”Footnote 8 The assumed self-contained and transcendent quality of this story is a lingering product of an approach deriving from New Criticism according to which each rabbinic story “supplies all the information necessary for its interpretation.”Footnote 9 These stories, instead, were intended to provide lasting instruction.

An emphasis on the enduring didactic quality of rabbinic stories forecloses possible historicist and contextual interpretations. Yet over the past few decades, an ever-growing body of scholarly literature has demonstrated the advantages of examining Babylonian rabbinic stories against the backdrop of their broader social and cultural milieux, in which they are deeply embedded.Footnote 10 Attention to the historical context makes legible not only crucial details, motifs, and realia mentioned in and presupposed by rabbinic stories, but also situates their instructive purpose, agenda, and tendenz in salient concerns of the time. These works recast the rabbis not as expositors of timeless values, but as subjects informed by and intervening in their own particular historical moment.

A more recent subset of research has demonstrated that Babylonian rabbinic texts share a common late antique Babylonian cosmology replete with a complex and highly delineated angelology and demonology controllable through various apotropaic and prophylactic practices.Footnote 11 That is, Babylonian rabbinic texts are conversant with the contemporary and geographically proximate beliefs and practices conventionally grouped under the problematic modern category of “magic.”Footnote 12 These studies therefore trouble older binaries that distinguished between the “popular masses,” who were supposedly mired in superstitions of the unlearned, and the scholastic elite represented by the rabbis, who rejected them.Footnote 13 Instead, these studies show that the rabbis were active participants in a larger world of discourses about controlling their enchanted cosmos, sublimating and “rabbinizing” earlier practices and even preexisting textual units to better accord with rabbinic ideas and ideals.Footnote 14 Key to these conceptual developments have been the ongoing publication and study of the Aramaic Incantation Bowls, ceramic bowls adorned with varying incantations in three dialects of Eastern Aramaic, but mainly in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic.Footnote 15 The bowls were discovered in the very regions in which the Babylonian rabbis dwelled, and divulge various direct relationships with both rabbinic literature and individual rabbis.Footnote 16

Through a study of the story of Pelimo, this article explores how rabbinic stories and discussions not only assumed knowledge of common apotropaic practices, but also served as vehicles through which rabbis adjudicated between these practices and determined which were licit and illicit, effective and ineffective. Rather than attesting a situation in which rabbinic piety involved the rejection or renunciation of popular practices, the story exemplifies how the rabbis at times selected between already widely available options, using narrative as a tool of persuasion. In turn, a comparison of the story of Pelimo with other late Babylonian rabbinic texts suggests a broader chronological development within Babylonian rabbinic thought about apotropaic practices, and demonstrates the benefits of attending to the composition history of the Talmud in the study of so-called magical and medical practices.

The Story of Pelimo

The story of Pelimo appears within a collection of interrelated stories.Footnote 17 It is preceded by two others in which Satan disguises himself as a woman to tempt and expose the hypocrisy of rabbis who scoffed at sinners, and appears just before a story about a rabbi who would regularly perform proskynesis and recite, “The Merciful One, save me from the evil inclination,” but is then tempted by his wife after she disguises herself.Footnote 18 The various stories in the collection have different associative links, including supernatural beings, disguise, and daily recitations. Our focus, however, will be on the story of Pelimo itself, which reads as follows:Footnote 19

פלימו הוה רגיל לומר גירא בעינא דשטנא

יומא חד מעלי יומא דכיפורי הוה

אידמי ל’ כעניא אתא קרא אבבא

אפיקו ל’ ריפתא

אמ’ יומא כי האידנא כולי עלמא אגואי ואנא אבראי

עיילו קריבו ריפתא קמיה

אמ’ יומא כי האידנא כולי עלמ’ אתכא ואנא לחודאי

אתיוה אותבוה אתכא

הוה מלי נפשיה שחינא וכיבי והוה קא עביד מילי דמאיסותא

אמ’ ל’ תיב שפיר

הבו ליה כסא אכמר שדא ביה

נחרו שקא ומית

שמע דהוו קאמרי פלימו קטל גברא

ערק טשא בבית הכסא אזל נפל קמיה

חזייה דהוה מצטער גלי ליה נפשיה א”ל ומאי טע’ אמרת הכי

ואלא היכי כו נימא

א”ל אימ’ רחמ’ יגער יי בך השטן

Pelimo would regularly say, “An arrow in Satan’s eye!”

One day, it was the eve of the Day of Atonement.

He [Satan] disguised himself as a poor man, came, and cried out at [Pelimo’s] door.

They brought out bread to him [Satan].

[Satan] said: “On a day like this, when everyone is within, and I am outside!?”

They brought himFootnote 20 in and served him bread.

[Satan] said to him: “On a day like this, when everyone sits at the table, and I am sitting alone!?”

They led him and sat him at the table.

He covered himself with boils and sores, and he was behaving repulsively.

[Pelimo] said to [Satan]: “Sit properly!”

They gave him a cup. He turned and spat into it.

They scolded [him], he [Satan] sunk and died.

He [Pelimo] heard that people were saying, “Pelimo killed a man!”

[Pelimo] ran and hid himself in a privy. [Satan followed him and]Footnote 21 he [Pelimo] fell before him.

When [Satan] saw that [Pelimo] was suffering, he revealed himself and said to him: “Why did you say this [‘An arrow in Satan’s eye’]?”

[Pelimo replied:] “And what then should we say [to keep you away]?

He [Satan] said to him: “Say ‘the Merciful One, may the Lord rebuke you Satan’ (version of Zech 3:2).”

The story raises several interpretive questions. Why does Pelimo regularly recite “An arrow in Satan’s eye”? Indeed, Pelimo’s recitation structures the entire narrative, as it initiates the story and its replacement by a different formula concludes it. Why does Satan take umbrage at this invocation and react the way he does? Why does Satan instead recommend the recitation of Zech 3:2, and what makes it preferable to Pelimo’s recitation?

“An Arrow in Satan’s Eye”

Pelimo’s invocation is found in two other pericopae in the Babylonian Talmud. One appears in the context of several anecdotes about rabbis who extol early marriage as a means of achieving purity of thought and deed. There, Rav ḥisda (c. early fourth century) declares:Footnote 22

[ב]הא עדיפנא מחבראי דנסיבני בשיתסר,[ואי]נסיבנא בארבסר, הוה אמינא ל’ לסטן גיר’ בעיניה

In this I am superior to my colleagues that I married at sixteen, and had I married at fourteen, I would have said to Satan, “An arrow in his eye!”

Rav ḥisda argues that his early marriage set him apart from his colleagues; however, had he married even earlier, he claims, he would have been able to declare to Satan, “An arrow in his eye!” This statement is often understood euphemistically, suggesting that his conduct would have been so pure that it would have been tantamount to fending off Satan with an arrow. However, considering the Pelimo story, it is clear that “An arrow in Satan’s eye” is not an expression but an invocation that was recited by individuals. Rav ḥisda is therefore saying one of two things. He may be saying that he would only have been qualified to make such a bold invocation had he married earlier and thereby been pure of thought and deed. The implication would be that the invocation is accompanied by some risk and should only be deployed by the especially righteous. Alternatively, Rav ḥisda is saying that marriage at fourteen is as effective a means of repelling Satan as reciting “An arrow in Satan’s eye.” Through this comparison, Rav ḥisda praises both the ability of early marriage to remove temptation and the invocation as a particularly potent means of repulsing Satan.

The formula appears again in a discussion concerning the two commandments that include a requirement to wave a ritual item on a festival: the offering of loaves of bread and lamb on Shavuot, and the four species on Sukkot.Footnote 23 A Mishnah in MenaḤot (5:6) details how the bread and lamb offerings brought on Shavuot are to be waved: back and forth and up and down. This is based on the seemingly redundant verbs of Exod 29:27 concerning the offering, which is both “waved” and “heaved up.” In the Talmudic pericope, Rabbi YoḤanan explains that this act of waving in four directions is intended to recognize that God is the ruler over heaven, earth, and the four winds, i.e., above, below, and all around.

The Babylonian Talmud continues with the comment that “in the West,” they teach that the reason the priest waves this offering in two sets of directions is to restrain wicked spirits (רוחות) and wicked shadows (טללים), common terms for malevolent forces that harm humans. Another Palestinian rabbi derives from this that even non-essential parts of commandments, such as waving, prevent calamities (מעכבין את הפורענות). The ritual act therefore wards off malevolent forces which reside in all directions.

At this point, the Babylonian rabbi Rava declares: “So too with regards to lulav,” meaning that like the sacrificial offerings, lulav, too, is a ritual act involving waiving that effectively repels malevolent forces.Footnote 24 Rava’s determination is followed by a brief anecdote about another Babylonian rabbi who used the lulav to repulse not just any demons, but Satan:Footnote 25

רב אחא בר יעקב ממטי ליה ומייתי ליה ואמ’ האי גירא בעינא דשטנא.

R. AḤa b. Jacob waved it [the lulav] to and fro, saying, “This is an arrowFootnote 26 in Satan’s eye.”

Even as Rav AḤa’s practice is clearly relevant to the larger discussion about the ability of ritual acts to ward off malevolent forces, his practice departs from it in two significant ways: he does not wave the lulav in four directions, but apparently only to and fro, and he accompanies this act with the utterance, “This is an arrow in Satan’s eye.” These two departures are interrelated; it appears that Rav AḤa is waving the lulav forward and backwards to mime the act of piercing Satan’s eye, meaning that the lulav is here functioning as the arrow attacking Satan’s eye, as the demonstrative pronoun in his invocation makes clear.Footnote 27

Intriguingly, this brief anecdote is followed by a short anonymous editorial interpolation that censures Rav AḤa’s practice:

.ולאו מילתא היא משום דאתי לאיגרויי ביה

This is not appropriate, because it will incite him [Satan] against him.

The anonymous comment condemns Rav AḤa’s action because it is likely to incite Satan against the performer, the opposite of the outcome that Rav AḤa intends.Footnote 28 The brief gloss shows a disagreement among the rabbis; Rav AḤa believed in the utility of the utterance, whereas the later gloss considers it dangerous. This same apprehension might also be found in Rav ḥisda’s statement that if he were married at fourteen, he would be qualified to say “An arrow in Satan’s eye”; only those entirely free from temptation could recite the formula without fear of inciting Satan against them. Rav ḥisda recognizes the apparent efficacy of this utterance, but also that only some are qualified to recite it.

For its part, the story of Pelimo narrativizes the tension between Rav AḤa’s practice and the critical anonymous gloss. Pelimo, like Rav AḤa and Rav ḥisda, believes in the efficacy of this utterance, yet by reciting it, Pelimo incites Satan against him, just as the anonymous gloss warned in the case of Rav AḤa. Yet whereas in the case of Rav AḤa, the anonymous gloss represents a secondary editorial interpolation, a later condemnation of an act Rav AḤa deemed appropriate, the story of Pelimo appears crafted from the outset to question the wisdom of reciting “An arrow in Satan’s eye.” This suggests a chronological development, between earlier Amoraim, like Rav AḤa and Rav ḥisda, who employed some version of this formula, and the anonymous gloss and the story of Pelimo, which were composed to combat it.

“An Arrow in Satan’s Eye” and the Much Suffering Eye

The fact that the same formula appears in three different Talmudic pericopes suggests that it enjoyed some degree of popularity. But the basis for this formula remains unclear, as does the reason it came to be rejected by the composer(s) of the story of Pelimo and the editorial gloss of the story of Rav AḤa. As a few scholars have noted, this utterance is an apotropaic formula of some sort, similar in nature to other non-scriptural apotropaic formulae found within rabbinic literature and in Christian and Muslim sources in the first millennium.Footnote 29

Yet the particular expression of a sharp object piercing a demonic eye is more directly reminiscent of an extremely popular and pervasive apotropaic image found across the Mediterranean in late antiquity: the so-called much suffering eye. The image—found on mosaics, marble plaques, and pendant amulets—depicts an eye attacked by various forms of sharp objects and aggressive animals, the former of which includes tridents, swords, spears, and daggers or arrows, and the latter includes scorpions, lions, snakes, and various birds and horned creatures. Spatially, the sharp inanimate objects typically strike from above, whereas the animals mainly strike from below. Like other late Hellenistic and Roman amuletic and apotropaic images, the depicted action serves by means of analogy to threaten the eye and thereby rebuff it.Footnote 30

Mosaic in the House of the Evil Eye, Antioch; Second Century (Wiki Commons)

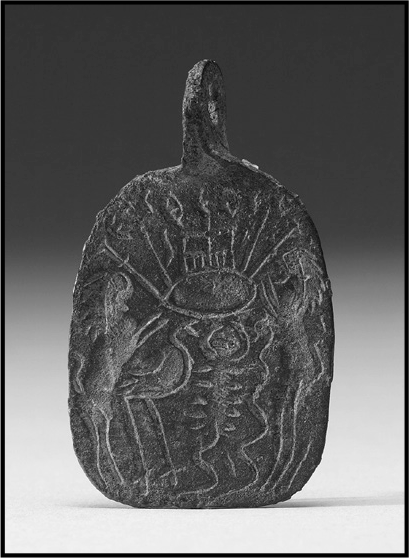

Pendant Amulet; Walters Art Museum 54.2653 (Wiki Commons)

Significantly, the image of the much suffering eye appears on a ceiling tile in the synagogue in Dura Europos in upper Mesopotamia, the only ancient synagogue discovered proximate to the regions in which Babylonian rabbis lived.Footnote 31 There, the eye in the image is attacked by a beetle from below, by two snakes on the side, and by three identical objects from above, each labeled with a letter from the Greek name of Yahweh, Iaô.

The much suffering eye served to repulse a range of different malevolent forces, whose identities regularly bled together, from particular demons, to the evil eye, to the demonic more generally.Footnote 32 The amalgamation of these possibilities is seen from the Testament of Solomon (18:39), which describes the apotropaic use of the image.Footnote 33 There, a demon named Rhyx Phtheneoth declares: “I cast the evil eye on every man. But the much suffering eye (ὃ πολυπαϑὴς ὀφϑαλμὸς), when inscribed, thwarts me.” To this text, the much suffering eye is a recognized amuletic motif which thwarts a particular demon, but that demon is responsible for deploying the evil eye against humanity. The evil eye may similarly have been conceived as simply one minion or manifestation of Satan himself.Footnote 34 Indeed, some late antique and later incantations depict the evil eye as an independent demon, an anthropomorphized figure with an eye for a body that is stabbed by the holy rider.Footnote 35

The formula “An arrow in Satan’s eye” is therefore likely an oral iteration of a common apotropaic image intended to symbolically attack the eye of the demonic force in order to deter it.Footnote 36 Indeed, this background explains why the formula in the Talmud targets the single eye of Satan rather than both of his eyes. The existence of oral iterations of an apotropaic image is not unique to this circumstance; we find it, for instance, in the case of Greek incantations.Footnote 37 However, whereas in those cases the oral iteration likely precedes the image, here it seems likelier that the oral iteration is an adaptation of the image.Footnote 38

The Babylonian Talmud may not be the only late antique Babylonian text to reflect a textual or oral iteration of the much suffering eye. The Shafta ḏ-pishra ḏ-ainia or the Scroll of the Exorcism of the Eyes, a Mandaic collection of incantations against the evil eye(s), includes a striking, even more comprehensive, verbal description of the much suffering eye.Footnote 39 Though the text only survives in modern copies, the work contains several near identical parallels with the Aramaic Incantation Bowls, suggesting that its recipes, or some versions thereof, largely date to late antiquity.Footnote 40 One formula reads:Footnote 41 “Tremble and be scared off, Evil Eye and Dimmed, from the body of N. son of N.! May the snake bite you and the scorpion sting you and the centipede sting you and the gander peck you and the sword cut you. . . .” This incantation almost perfectly reproduces the image of the much suffering eye. Indeed, every single attacking object described here appears on the much suffering eye mosaic in Antioch, and the individual elements are found in other iterations of the image. Another recipe in this Mandaic work similarly threatens the evil eye with various harms, including a snake, scorpion, crab, falcon, crane/goose, and kite.Footnote 42 These Mandaic incantations are further proof that the much suffering eye was rendered into words by others in late antique Babylonia.Footnote 43

However, as opposed to the two Mandaic incantations, the version used by the rabbis selects only one sharp object to use against the eye: the arrow. The significance of this may lie in the fact that in many manifestations of the much suffering eye, the sharp objects attacking the eye from above are wielded by a deity. In particular, in several iterations of the motif, a trident is rammed into the eye from above by Poseidon himself, as depicted in the marble plaque from the collection of Woburn Abbey. The trident also appears without Poseidon, such as in the Mosaic in the House of the Evil Eye in Antioch, but one might suggest that Poseidon’s presence is here implied. Over the course of late antiquity, the trident, and in time, three distinct smaller sharp objects which derive from the three spikes of the trident, continue to appear above the eye in pendant amulets, without Poseidon grasping it. However, these are now accompanied by formulae naming the deity, such as Ἰἁω Σαβαὠθ Μιχαἠλ βοἡθι (Iao Sabaoth, Michael, help), or more basically, Eἷς Θεός (the “One God”).Footnote 44 Fascinatingly, the ceiling tile in Dura Europos seems to have a simplified version of this motif.Footnote 45 Instead of a trident from above, it too has three spikes, and each is accompanied by one letter from God’s name in Greek, Iaô. These amulets and images therefore make explicit that it is a divine actor threatening the eye with violence.Footnote 46

The development of the motif may explain the tension in the Talmud between the use of the formula by earlier Amoraim and its rejection by later Talmudic editors and composers. I suggest that originally the oral utterance of “An arrow in Satan’s eye” was formed not simply by picking a single weapon at random from the motif of the much suffering eye, but by selecting the sharp object thrust by a deity. The formula, in its origins, may have intended that it was God wielding the arrow to attack Satan, and the implied divine authority behind the invocation was clear to the rabbis who recited it.Footnote 47 In time, however, the implied presence of the deity, and the association with the image of the much suffering eye, may have been lost.Footnote 48 As a stand-alone utterance, it troubled later editors and composers, to whom it seemed audaciously to pit the reciter as the wielder of the arrow against Satan himself.

Satan’s Resistance and Misbehavior

As a story about the (in)effectiveness of a particular apotropaic utterance to repulse Satan, Satan’s behavior throughout his encounter with Pelimo is consistent with what we would expect based on the prevalent demonology in late antique Babylonia.

First and foremost, in seeking entry into Pelimo’s house, Satan attempts to accomplish precisely what incantations sought to prevent: the entrance of malevolent forces into the home of the client.Footnote 49 Indeed, for this reason, incantation bowls and other apotropaic incantations and objects were most commonly placed at the threshold of a house or individual rooms therein.Footnote 50 A regular class of demons listed in the bowls among those seeking entry is the “satans” (סטני).Footnote 51

The means by which Satan in the story enters the home takes advantage of real social practices evidenced by several Babylonian rabbinic sources and incantation bowls.Footnote 52 Satan approaches Pelimo’s home on the eve of the Day of Atonement disguised as a pauper and asks for sustenance. Charity in the form of food, liquid, and other needs regularly occurred at the entrance or doorway of homes in Babylonia, as depicted in rabbinic stories of highly charitable individuals.Footnote 53 Festivals in particular were occasions for charity of this kind, and it was especially meritorious to eat before the Day of Atonement and provide for others to do the same.Footnote 54 It is likely not by chance that Satan arrives on the eve of the Day of Atonement, as elsewhere in the Babylonian Talmud it is identified as the one day a year when Satan does not have permission to “accuse.”Footnote 55 Perhaps the setting is meant to heighten the sense of the ineffectiveness of the invocation “An arrow in Satan’s eye,” which incites Satan even on the one day a year when he was supposedly powerless.

That Satan is asking for something as basic as food and liquid is consistent with the idea found in both the Babylonian Talmud and the incantation bowls that demonic forces had corporeal qualities, among them the consumption of food.Footnote 56 Indeed, several bowl incantations feature a particular formula that, paradoxically, fends off malevolent forces from one’s home precisely by inviting them to enter and consume food and liquid, but solely on the condition of peaceful entry, requiring them otherwise to leave altogether.Footnote 57 This background underscores the extent to which Pelimo’s original utterance failed: Satan accepts Pelimo’s charity but uses it to infiltrate his home. Predictably, once in the house, Satan wreaks havoc, by flouting social conventions and eventually jeopardizing the head of the household, Pelimo.Footnote 58 Meaningfully, the language used to describe how Satan’s body “was covered with boils and sores” has a verbatim parallel to another story in the Talmud, which also appears in a context related to “magic.”Footnote 59 There, a rabbi utters some form of incantation to generate “boils and sores” on his body in order to repel a woman seeking to seduce him, whereas here it is Satan who generates the boils and sores to repel the members of Pelimo’s household.

Upon being accused of killing the pauper, Pelimo flees to a privy where he is directly confronted by Satan. The privy was a common site of malevolent forces in antiquity.Footnote 60 Both Jewish and non-Jewish sources thematize the dangers represented by the concentration of malevolent forces in bathrooms. Within rabbinic literature, the concern for the demonic in bathrooms is particularly pronounced in Babylonian sources.Footnote 61 The Babylonian Talmud offers multiple blessings for entering and exiting the toilet, some of which parallel those found on Aramaic incantation bowls.Footnote 62 Pelimo therefore encounters Satan in two places where one would expect to find him based on the demonology prevalent at the time: the home and the privy.

Indeed, the demonological context of the story can be seen by examining a clear rabbinic literary parallel, both in terms of content and language.Footnote 63 In another Babylonian rabbinic story, the Angel of Death is prevented from ending Rabbi Ḥiyya’s life because he never ceases studying Torah. To distract him, the Angel of Death appears as a pauper (אידמי ליה כעניא) and knocks on his door to ask for bread (אתא טריף אבבא, אמר ליה: אפיק לי ריפתא). When bread is brought to him (אפיקו ליה), the Angel of Death asks why R. Ḥiyya is not honoring him, presumably by personally greeting him. When R. Ḥiyya opens the door the Angel of Death reveals himself (גלי ליה) to him and immediately takes his life by means of his instrument, the fiery rod.

Despite their obvious similarities, the stories depart precisely in terms of the character traits and objectives associated with the Angel of Death and Satan respectively. The Angel of Death is not provoked in any way, he is simply doing his job and seeking to take R. Ḥiyya’s life at the appropriate time. By contrast, Satan is provoked by Pelimo’s utterance, and responds accordingly. The Angel of Death seeks to distract R. Ḥiyya from his learning in order to end his life, and so begs for him to greet him at the entrance. Satan wishes to enter the house itself, where he wreaks havoc. The Angel of Death’s encounter with R. Ḥiyya ends immediately upon his death, whereas Satan does not kill or even physically harm Pelimo as much as harass him, even relocating to the privy, a site of demonic habitation. Both stories end with the “reveal” of the supernatural figure behind the disguise.

The composer of the story of Pelimo therefore employed a shared literary template of an encounter between a human and supernatural being, but in so doing highlighted crucial differences between them. A story about the successful repulsing of one supernatural being (the Angel of Death) by means of a speech act (Torah study) is transformed into a story about inciting another supernatural being (Satan) through provocative speech (“An arrow in Satan’s eye”), and ends precisely by instructing Pelimo—and the story’s audience—about how to successfully thwart Satan in the future.

Zechariah 3:2

At the story’s conclusion, Satan recommends that Pelimo recite a version of Zech 3:2, which in one set of manuscripts is rendered entirely in an Aramaic paraphrase—“May the Merciful One rebuke Satan”—while in the other is a hybrid of Aramaic (“O Merciful One,” רחמנא) and the Hebrew of the verse.Footnote 64 Why does Satan recommend this formula in particular?

Zechariah 3:2 appears in the context of Zechariah’s vision of Joshua the High Priest, a crucial if elliptical figure in the return of Jews from the Babylonian exile. In the vision, Joshua stands before the “angel of the Lord,” while Satan stands to Joshua’s right and accuses him.Footnote 65 At this point God intervenes:

ויאמר יהוה אל השטן יגער יהוה בך השטן ויגער יהוה בך הבחר בירושלם הלוא זה אוד מצל.מאש

The Lord said to Satan, “The Lord rebuke you, Satan! The Lord, who has chosen Jerusalem, rebuke you! Is this one not a burning stick snatched from the fire?”

In the verse, God himself “rebukes” Satan.Footnote 66 The verb for “rebuke” (גער) appears elsewhere in the Bible in similar interpersonal contexts: Jacob rebukes Joseph for his dream (Gen 37:10), a letter rebukes Jeremiah (Jer 29:27), God rebukes the sea, restoring order to chaos (2 Sam 22:16; Nah 1:4; Ps 18:16; Job 26:11–13), and God’s rebuke is likened to fire (Isa 66:15). While the verbal root is conventionally translated as rebuke, as I have rendered it throughout, the semantic range can be more accurately described as denoting an effective speech act, and in the case of God’s usage, as “the deity’s effective power against his enemies via the use of speech.”Footnote 67

This expanded semantic range explains a second related sense of the same root in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Ugaritic apotropaic texts: to exorcise or combat malevolent forces.Footnote 68 According to the most recent edition, this usage is already found in the Ketef Hinnom Amulets, Hebrew incantations dating from the seventh to sixth centuries BCE.Footnote 69 The reconstructed text of Amulet B now includes the line “May h[e]/sh[e] be blessed by Yahweh, the warrior [or: helper] and the rebuker (הגער) of [E]vil.”Footnote 70 This usage is found as well in several of the Dead Sea Scrolls.Footnote 71 The root continues to be highly productive in late antique Jewish amulets in both Palestine and Babylonia.Footnote 72 The verb is similarly used in the New Testament, where ἐπιτιμάν describes Jesus’ exorcistic activities, the same root used to translate גער in the LXX.Footnote 73

Given the semantic range of this root, Zech 3:2 came to be understood not only as God “rebuking” Satan similar to Jacob rebuking Joseph, but as God exorcising or dismissing Satan himself. Invoking the verse came to reenact God’s rebuke of Satan.Footnote 74 The verse therefore appears on a couple of late antique Jewish amulets.Footnote 75 Strikingly, in a passage in Jude 9, in what seems to be an allusion to a now lost Second Temple text describing an exchange between the angel Michael and Satan, Michael chooses not to “accuse Satan of blasphemy” (κρίσιν ἐπενεγκεῖν βλασφημίας), but instead recites Zech 3:2 to rebuke Satan.Footnote 76 As in the story of Pelimo, here Michael prefers Zech 3:2 over a different utterance against Satan. The appeal of this verse as an utterance in amulets and in Jude 9 is clear: like the analogical operation behind the much suffering eye, here God’s own action in the past is invoked to apply in the present.Footnote 77

Though this verse appears on only a few western late antique Jewish amulets, it is one of the most cited verses in the incantation bowls, featured on roughly twenty-five of those published to date.Footnote 78 The verse’s appearance on the bowls is itself telling. In most cases, it appears at the very end of the incantation, often following a natural concluding point, such as the affirmation, “Amen Amen Selah.”Footnote 79 This suggests that scribes saw it as a potent additional invocation, or even as a means of applying God’s rebuke of Satan to the entirety of the preceding incantation.Footnote 80 Indeed, a set of parallel incantations provide a window into this scribal operation, as one scribe saw fit to add the verse to the end.Footnote 81 To be sure, verses are often cited at the end of bowl incantations, but the frequency of Zech 3:2 in this position is noteworthy.Footnote 82

While Zech 3:2 often appears alone at the end of incantations, it is also integrated alongside other scriptural citations in this position.Footnote 83 When these passages are compared, one can surmise that what made them particularly attractive as apotropaic formulae was that all were likely understood to reflect God’s sovereignty and power over other forces in the cosmos. In two bowls, Zech 3:2 appears alongside Deut 6:4 and Ps 91:1. The former is of course the verse from the Shema which declares that God is “one” or “alone,” implying his supremacy over all other divine forces, while Ps 91:1 is the opening of a Psalm in which the protagonist is under God’s shadow, and God serves as his “refuge and fortress” against various forces, including pestilence, terror of the night, arrows, plague, and more. Similarly, in two cases Zech 3:2 appears alongside Num 9:23 (in one case also with Deut 6:4), another popular verse in the bowls. Though in its original context this verse is about the Israelites’ journeying and camping at God’s command, in the context of the incantation bowls the verse appears to imply that all forces—including the angelic and demonic— are ultimately commanded by God Himself.Footnote 84 Other verses—Num 12:13, Ps 121:7, and Is 51:14— refer to God’s ability to heal, to protect, and to loosen those bent down by “the oppressor” (המציק), or in Ps 55:9, man fleeing from “the stormy wind,” all easily applicable to the context of repelling demons.Footnote 85

The shared practice behind the use of Zech 3:2 in the bowls and in the story of Pelimo is further on display in the fact that, in the story, Satan does not recommend the recitation of Zech 3:2 in Hebrew, but in an (at least partially) Aramaic paraphrase.Footnote 86 The use of an Aramaic paraphrase is itself reflective of the practice in some bowl incantations to cite Aramaic translations of biblical verses, sometimes without any clear relationship to the surviving formal literary Targumim.Footnote 87

The story of Pelimo is in fact not the only Babylonian rabbinic text to embrace the recitation of Zech 3:2. In another passage (b. Ber. 51a), Rabbi Joshua b. Levi lists three pieces of advice given to him by the Angel of Death regarding situations to avoid, in order to escape inadvertently bringing harm upon oneself. The Angel of Death’s final piece of advice is to avoid standing before women when they return from visiting the dead. The Angel of Death explains that in this scenario, “I go leaping before them with my sword in hand, and I have permission to harm.” This Hebrew saying is followed by an anonymous Aramaic gloss which undoubtedly postdates the original statement attributed to Joshua b. Levi. It asks, “And if one happens upon [these women], what is the remedy?” That is, the gloss seeks a solution if the initial attempt to avoid complications was unsuccessful. It offers a series of possibilities, which include turning aside four cubits, crossing the river, taking another path, and hiding behind a wall. The gloss continues, “And if he cannot do any of these things, let him turn his face away and say, “The Lord said to Satan, ‘The Lord rebuke you, Satan,’ until they have passed.” Here a late Babylonian rabbinic gloss again presents Zech 3:2 as an effective apotropaic remedy even after other solutions are unavailable.Footnote 88 This source shares a thematic relationship with the story of Pelimo, in that both the Angel of Death and Satan offer advice on how to successfully keep them away and avoid harm at their hands.Footnote 89

The story of Pelimo therefore rejects one apotropaic formula popular in late antique Babylonia in favor of another.Footnote 90 Far from departing from or critiquing popular practices, here the rabbis select between them, using Satan himself as their mouthpiece. Indeed, the story offers a rationale for the popularity of Zech 3:2 in the incantation bowls and apparently in the eyes of the later Talmudic editors responsible for b. Ber. 51a. On a basic level, the story reflects a preference for scriptural citations over other invocations with no basis in scripture. The story however likely goes even further, suggesting that Zech 3:2 corrects for the problems with “an arrow in Satan’s eye”; where the latter pits the reciter directly against Satan, thereby endangering himself, the former invokes God as the prototypical rebuker of Satan. The story therefore expresses the importance of the authority behind invocations, a concern we find in other rabbinic texts and a familiar trajectory in the development of ancient incantations more generally.Footnote 91 Moreover, judging by the story, scriptural texts were not selected willy-nilly, as a general act of “piety,” but rather for their applicability to the circumstances.Footnote 92 This is borne out from an examination of the scriptural citations used in the incantation bowls; though bowl scribes display some flexibility in terms of the scriptural passages they invoked, the most commonly cited texts were those in which God’s activity could be applied to the context of the incantations themselves. Not only do the rabbis not stand apart from common practice, but they offer a rationale for it, through the particular medium of the rabbinic story.

Apotropaic Use of Scripture and the Later Babylonian Rabbis

As we have seen, the story of Pelimo offers a similar critique of “an arrow in Satan’s eye” as that of the anonymous gloss to the story of Rav AḤa, and it recommends the recitation of Zech 3:2 as does the anonymous gloss in b. Ber. 51a. Coupled with its use of a literary template and features found in other stories in the Talmud (e.g., b. Moʿed Qaṭ. 28a), this suggests that the story originated in the period of the Talmud’s redaction, generally dated to the sixth century, precisely the period of the incantation bowls’ production.Footnote 93 Together, the correspondences between the story and these various editorial additions in the Talmud indicate a growing interest among the Talmud’s later editors in delimiting the use of scripture in prophylactic contexts.

This pattern is visible throughout the Babylonian Talmud. For instance, in one place, the anonymous editors distinguish between licit and illicit uses of biblical verses.Footnote 94 They reconcile an apparent contradiction between an anecdote about a rabbi who, on the one hand, recited verses before bed and, on the other, stated that one may not recite verses to heal oneself, by distinguishing between reciting verses to heal, which is proscribed, and reciting verses for protection, which is permissible.Footnote 95 In this same pericope, the anonymous editors further qualify the famous early Tannaitic statement by Rabbi Akiva that “one who whispers over a wound” (הלוחש על המכה) the verse Exod 15:26 (“Every illness that I placed upon Egypt I will not place upon you, for I am the Lord, your Healer”) has no share in the world to come.Footnote 96 The anonymous editors cite the opinion of a R. YoḤanan b. Beroka that Rabbi Akiva’s opinion only applies if one spits on the wound while reciting the passage, because one may not recite the name of God over spit. While R. YoḤanan’s cryptic limiting statement is cited elsewhere in the Talmud without elaboration (b. Sanh. 101a), seemingly only commenting on the permissibility of the recitation of Exod 15:26, the anonymous editors craftily deploy his opinion here to undermine a major Tannaitic precedent and dismiss any possible objection to the use of scripture for prophylactic purposes more generally.Footnote 97

In another case, in the so-called “Talmudic Dreambook,” the anonymous editors again update an earlier discussion to include the prophylactic recitation of verses. In the pericope, a chain of rabbis state that if one has an ominous dream, they should “go and have it interpreted before three [people].”Footnote 98 The anonymous editors interject that this opinion contradicts that of Rav ḥisda who said that an uninterpreted dream was like an unread letter, either meaning that it had no force until interpreted or that its meaning could only be known upon interpretation.Footnote 99 The anonymous editors, again switching to Aramaic instead of the Hebrew of the original dictum, clarify that one should “spin [the dream] positively before three.”Footnote 100 They continue to detail the procedure:

He should go and sit before three [some mss: who love him] and say to them “I had a good dream.”

And they should respond to him seven times “it was good, and may it be good, and may the good Merciful One make it good, and from heaven may it be decreed upon himFootnote 101 that it be good, and may it be good, and good may it be.”

And they should say to him three [verses with the word] “overturn” (הפך), and three with “redeem” (פדה) and three with “peace” (שלום) concerning saving, and three concerning peace: [continues to cite the following verses for overturn: Ps 30:12, Jer 31:12, Deut 23:6; for redeem: Ps 55:19, Isa 35:10, I Sam. 14:45; for peace: Isa. 57:19, I Chr. 12:19, I Sam. 25:6].Footnote 102

The anonymous editors introduce an entirely new ritual to counteract a bad dream, one which includes recharacterizing the nature of the dream, repetitive formulae, and the use of biblical verses with words that directly address the concern posed by a bad dream.

Like the prescription to recite Zech 3:2 in b. Ber. 51a, the anonymous editors elsewhere also prescribe verses in specific contexts, in each case using the same introductory formula: “what is its remedy” (מאי תקנתיה). In b. PesaḤ. 111a, if a man encounters a woman returning from purifying herself after her menstrual period, whichever of them has intercourse first is taken by the “spirit of harlotry.” The anonymous editors ask “what is its remedy” (מאי תקנתיה), and prescribe the recitation of Ps 107:40, according to some manuscripts, or the very similar Job 12:21, according to others. The passage includes other anonymous glosses that ask “what is its remedy” (מאי תקנתיה) before offering solutions.Footnote 103 A few lines earlier, it says that men should avoid having a menstruating woman walk between them. The editors ask “what is its remedy” (מאי תקנתיה), and answer that they should recite a verse that begins and ends with God/אל, which commentators suggest refers to Num 23:22–23. Curiously, just before this, the Talmud presents a Tannaitic statement about never passing between or being passed between by a dog, palm tree, or woman, and according to some, also a pig and snake. The Talmud once again asks if one does indeed pass them, “what is its remedy” (מאי תקנתיה). Yet here, the remedy is attributed to Rav Papa, who says that one should recite a verse that begins and ends with God (אל), just as the ensuing anonymous comment suggests. An alternative view attributed to “others” however apparently suggests that one should instead say a verse that begins with no (לא) and ends with “to him” (לו), which likely refers to Num 23:19. It is possible that the opinion attributed to Rav Papa was in fact stated by the anonymous editors and only received an attribution at a later date, but even if the attribution to Rav Papa is original, it is noteworthy that the proposed remedy of the recitation of particular verses are mainly made by the anonymous editors.

In each of these cases, the anonymous editors express an interest in prescribing the use of scripture for protection and stipulating its proper use in incantatory contexts. To be sure, there are several medico-magical statements in the Babylonian Talmud attributed to earlier sages that prescribe the recitation of scripture, and in other cases the anonymous editors recommend invocations other than scripture.Footnote 104 But the preponderance of apotropaic uses of scripture is in later anonymous editorial comments. The chronological stratification suggests some change or at least intensification of rabbinic attitudes and ideas about incantations and the place of scripture within them.Footnote 105 Indeed, rather than take for granted that scripture would always be welcome in apotropaic contexts, the greater prevalence of apotropaic uses of scripture in the later layers of the Talmud contrasts markedly with the near absence of any practical recipes with scripture in some early medieval handbooks like Sefer HaRazim and Ḥarba DeMoshe.Footnote 106

This chronological shift in rabbinic notions of incantations allows us to recognize historical developments even within the rabbinic corpus. Further work must similarly move not only beyond older monolithic characterizations of a single “rabbinic” attitude towards “magic,” but also beyond flattened portraits that collapse all of rabbinic literature into a messy stew of diverse and conflicting opinions.Footnote 107 While acknowledging rabbinic diversity, methods like literary source criticism of the Babylonian Talmud enable scholars to identify developments and changing trends among the rabbis that map onto place and time.Footnote 108

Conclusion

The story of Pelimo exemplifies the benefits of historicist approaches that situate rabbinic stories in their ambient social and cultural milieu. The story is predicated on a rich set of common notions about the behavior of demons and the use of particular apotropaic formulae current in late antique Babylonia. It not only assumes knowledge of this context, but directly participates and intervenes in it by contrasting two different apotropaic formulae, using Satan as a mouthpiece in favor of one over the other. The rabbinic story thereby creatively articulates the rationale behind why at least some Jews, as evidenced especially by the incantation bowls, and by several other late Babylonian rabbinic passages, preferred to invoke scripture. Rather than stand apart from prevalent assumptions and practices among Babylonian Jews, the rabbis rejected some common practices while endorsing and amplifying others. In turn, the story of Pelimo is part of a nexus of late Babylonian rabbinic texts that express a growing interest in the use of scripture in apotropaic contexts. This development among the Talmud’s editors calls on scholars to not only problematize older binaries between rabbis and non-rabbis, elite and non-elite, but to attend to developments within rabbinic literature and among the rabbis in their conceptions of magic and medicine.