Introduction

One night at a bar named Zugaikotsu’s, I explained to an Englishman who sometimes drops by that I had been participating in the bar’s regular haiku poetry group gathering. This group meets periodically to rank and discuss submitted poems. After listening, he asked, “Do you think you can teach anyone to be a poet?” I glanced around, thinking of how much the group had taught me, and replied, “Yes.” He bluntly responded, “I don’t. You either have it or you don’t.” His stance reflects the normative Western perception of artistic creativity and hints at a mainstream understanding of what creative practice entails; a lonely, canon-defying genius with innate skills creating art in isolation. Whether or not such geniuses exist, this folk theory of them persists. Yet many scholars have shown that authorship is rarely singular (Becker Reference Becker2008; Paulson Reference Paulson2001), and improvisational skills are often taught (Wilf Reference Wilf2010, Reference Wilf2012, Reference Wilf2014). Haiku groups, which are usually hierarchical social gatherings where 5/7/5 haiku are composed and evaluated by a sensei, differ from the myth of the lonely genius practice and ideology. Instead, this form of poetry-writing is simultaneously a collective and an individual practice, where the judgement of peers, especially elders, is crucial for developing one’s poetic skills. This article examines one venue where the collective judgment of works is key—a gathering of haiku poets. What role do these gatherings play in the creation of haiku?

Zugaikotsu’s haiku group, decidedly unorthodox because of the venue and the consumption of alcohol, is a site of relational creativity in part because of its format as a game with a democratic scoring system. This not only provides a forum for people to try out their poems but also allows them to sharpen their sense of what makes a good haiku—in other words, they can practice criticism. The format and schedule also provide a venue for everyone to practice and compose on a common theme. The form and use of kigo (seasonal words) are set by convention; the theme makes the act of composing poems collaborative from the beginning. This bar also presents a forum of encouragement, which can give people a reason to compose when they might not otherwise. This and other Jimbocho haiku gatherings that include alcohol are criticized by many as being subversive. I argue that situating haiku composition in a lighthearted forum nevertheless allows for productive improvement as a poet, achieved in part through collaboration.

This ethnographic study of a haiku gathering started with a personal introduction. One evening, the owner of a pub introduced me to Shinpindo, the owner of a nearby bar, Zugaikotsu’s. When I gave Shinpindo my business card, she complimented the illustration on the back, which I drew, and later, she asked me to design a menu for the bar. From then on, I started to frequent her place. Glancing in from the street, it was clear that it was the kind of place with jōren (regular, sometimes daily) clientele, who look up in unison to see who is at the door, and I had not been comfortable going without an introduction. Inside, cane lampshades, walls of a heavy “California knockdown stucco” covered in the patina of years of cigarette smoke, and a green laminate countertop give the bar a retro atmosphere. Behind the bar is a whiteboard with upcoming events, among them, an announcement for the upcoming haiku-kai—the haiku group—the deadline for submission and date, and the next theme (kendai). Anyone can submit a poem, and the new owner, Shinpindo, encouraged me to give it a try.

A trade district specializing in old books and publishing during the day, in the evening Jimbocho turns into a place of intellectual cross-pollination, in restaurants and bars. The bar has a constitutive group of regulars who gather once every two months to evaluate each other’s poems on a given theme. Among the jōren, many people have written, translated, or edited a book, and some participate in writing and discussing poetry in its traditional forms, particularly haiku and renku. Not only does haiku belong to a poetic tradition going back hundreds of years, but groups devoted to it also cultivate a mode of collective production that dates back at least through the Tokugawa period, if we include its predecessor haikai. While some groups publish the poems their members produce, most do not. Meeting to compose poems is an undertaking with other goals.

On a haiku night, participants, most regulars, gather to read aloud poems that have been submitted in advance. After a poem is read aloud, the score and author are revealed, and it is discussed, critiqued, and joked about. As the gathering unfolds, the high-scoring poem is revealed as well as the lowest-scoring haiku. Atypically, this group drinks during the gathering, leading to a raucous and entertaining evening. Here, I ask: Why is one of the world’s shortest poetic genres a site of relational creativity, and how do poetry groups enable relational creativity? Furthermore, why turn critique into a game? How can scoring become a forum for relational creativity?

Methods and conventions

Anthropology, with its emphasis on participation observation, is an ideal method for studying poetry in social contexts. The observations and communications analyzed here were collected over 24 months of ethnographic fieldwork in the Jimbocho area of Tokyo using participant observation and interviews with poetry group participants. This ethnographic fieldwork, which touches on the question of authorship, raises questions about how to refer to informants in this essay. The names of venues and individuals have been anonymized using pseudonyms, based on their haiku pen names (haigo).

This fieldwork is based on participant observation at Zugaikotsu’s from 2020 to 2023, during which period I spent time there, participating in the haiku and renku groups, composing poems, and conducting informal interviews. I also collected oral histories from founding figures of the group, such as Aruki and Shinpindo, as well as from several regular customers. I participated in the bi-monthly camping and fishing trips with poetry group members. These trips also became the basis of a shared repertoire of poetic images, such as octopus fishing, campfires, and harvesting biwa fruit. These outings organized by the bar were both an opportunity to return to nature and a chance to form collective memories. In addition to participant observation, I collected and analyzed poems composed in these settings. In critique during the haiku gathering, I found that banter and jokes were intertwined with criticism and suggestions; I tried to capture both.

Writing poetry involves playing with words, and Japanese uses four scripts—kanji, hiranaga, katakana, and romaji—creating scriptic flexibility. Writers may use any for effect in a composition. They may also use furigana or rubi, the superscript used to give the pronunciation of kanji, to specify a reading for particular characters to conform to the 5/7/5 syllable pattern. A good example of this scriptic flexibility is the name of the bar itself. On the signboard outside Zugaikotsu’s, the bar name is written in romaji, but in haiku and social media messages, it is often written in either hiragana or katakana as Zugaikotsu. As an anthropologist, I take these emic conventions seriously, as they are an important part of expression and identity. In principle, I follow Hepburn romanization, except in cases where particular spellings reflect emic understandings or when they are used to make a poem conform to the 5/7/5 pattern. I adopt the romaji spelling of the bar’s name in my analysis but use Zugaikotsu when transcribing haiku, where the long “o” matters to poetic structure in terms of counting syllables. Similarly, I follow the romanization of Jimbōchō, using an “m” instead of an “n,” which is preferred by neighborhood associations.

This project developed from participation and collaboration with informants who already understood my research project on Jimbocho’s old bookstores. It is fair to say that they helped me formulate this inquiry from the field up. They participated directly in my note-taking, often practicing a form of tutelage. In terms of fieldnotes, I rarely recorded the haiku gathering, though when I did, I obtained the verbal consent of everyone present in the bar; I also obtained verbal consent regarding notetaking. Regarding recordings, I quickly realized that there were too many people participating, resulting in low audio quality. Instead, I took notes on the gathering’s haiku sheet, aiming to record the flow of the meeting. The haiku group usually has up to 30 participants, and gatherings are informal with no strict hierarchy. When I asked about recording the data to use as part of my research, everyone agreed, but most were perplexed that I would want to write about such an unserious group.

A significant portion of my insights come from being taught; members kindly shared expertise with me, as well as explicating each other’s critiques. Before beginning this fieldwork, I had little familiarity with haiku, and I did not intend to start composing it. The form is deceptively simple, but after a few attempts in Japanese language classes in college, I gave up out of frustration. Members of the group were quick to offer friendly feedback. Even as an outsider and a beginner, I was invited to score the poems of people far more capable than myself. This raises a set of questions about how competition is negotiated and integrated into communal creative practices.

Haiku as genre and collaborative creativity

Simple on its face, haiku is a genre of poetry composed of three lines of five, seven, and five syllables—it is one of the most recognizable genres of poetry in the world. However, its simplicity belies a complex and contested history, much of which is concerned with its status as an art form. Pinning down exactly when haiku became haiku is difficult, but it owes much of its current form and conventions to Shiki Masaoka, who aimed to establish it as a form of literature with a single author. Since then, there has been an ongoing debate over whether or not it is literature. Tuck argues that critics, including Shiki and others in his orbit, guided haiku away from “commoner literature” to be understood as literature proper, and framed the form within discourses of educational attainment and gender (Tuck Reference Tuck2018: 119). Still, many argue that haiku is a democratic form because nearly anyone can compose them. Some, such as Kuwahara Takeo, argue this bars it from the status of art (cited in Tuck Reference Tuck2018: 117).

How poetry is made is deeply rooted in social and cultural contexts. Contrary to the assumptions of the Englishman quoted in my introduction, Japanese poetry has been rooted in collaborative social practice for centuries. Shiki extracted the opening 5/7/5 hokku couplet from renga and renamed it haiku (the word has a much longer history). Shirane points out that there was a significant Western influence in Shiki’s efforts to render haiku into a form of literature with a single author, whereas before it had been seen as deeply embedded in social settings (Shirane Reference Shirane2019: 462), emerging from its role as hokku, the opening couplet, in connected verse settings (haikai or renga). Renga, linked poetry composed in a repeating 5/7/5/7/7 pattern, was composed with two or more people vying to “cap” or answer a couplet. Over time, the opening 5/7/5 couplet, hokku, took on increasing importance; the renga master Basho is today remembered as a haiku poet because his hokku fit the rules established by Shiki for haiku in the modern period.

What makes a poet is similarly a subject of ideology, history, and cultural perception. Creativity is often seen as solitary, innate, and rebellious—a belief exemplified by the Englishman’s comments. Haiku’s history is frequently framed around figures such as Basho, Buson, Issa, and Shiki, who are seen as revolutionary poets who broke rules and transformed the genre (Stryk Reference Stryk1994). However, while haiku is often celebrated for its modernity and for shattering conventions, it has also become deeply codified. Elements such as kigo (season words) and kiriji (cutting words) serve to standardize the form, distinguishing, for example, haiku from senryu by the presence of kigo. This duality—haiku as both innovative and highly structured—highlights a paradox at the heart of the genre; it is both a site of creative freedom and a form bound by tradition and strict conventions.

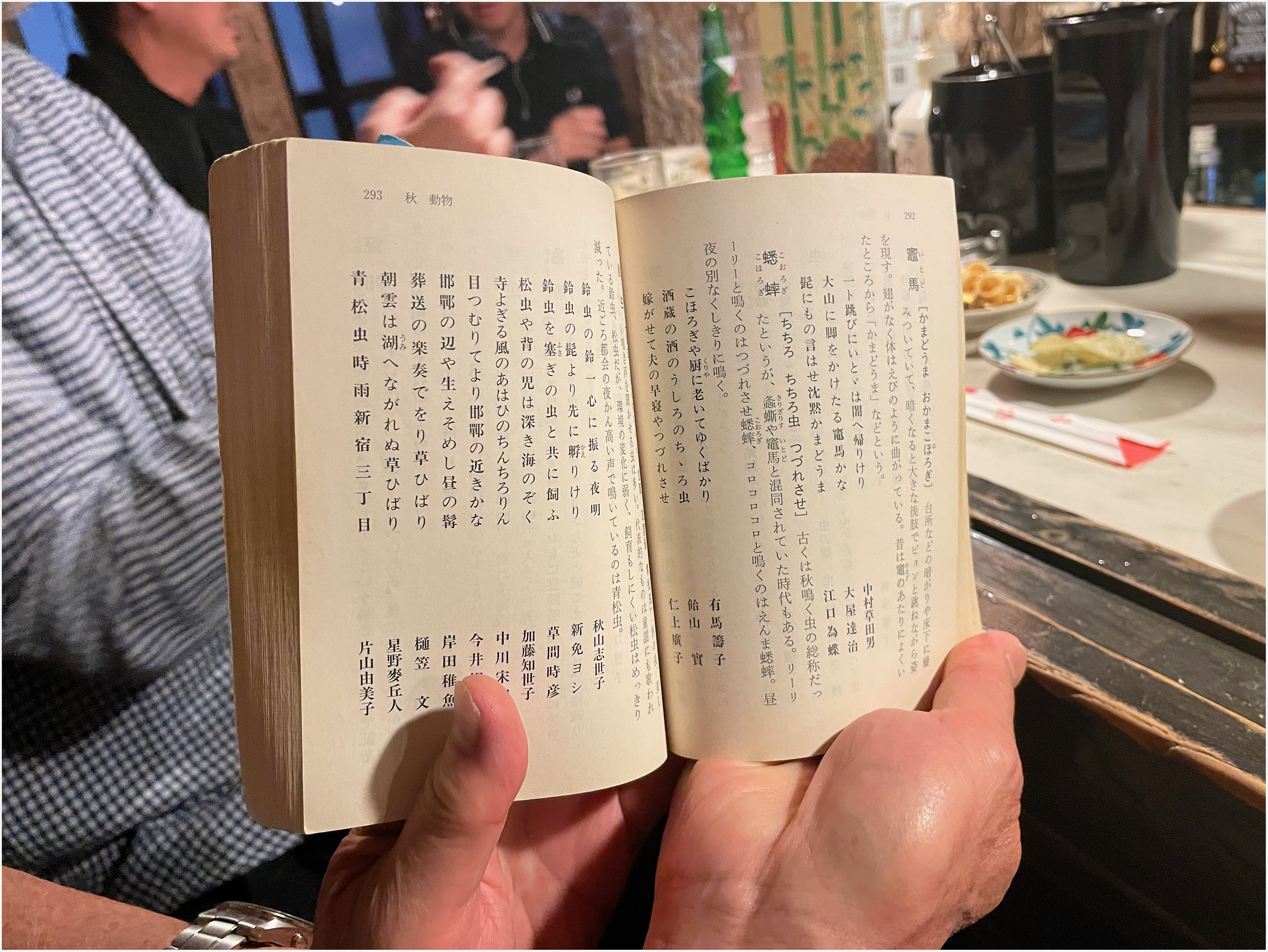

Like any poetry, haiku is embedded in a social context that shapes its interpretation, but perhaps uniquely so because of its brevity. Haruo Shirane argues that the brevity of the form is possible because it relies on the reader to enter into a dialog with the poem, unfolding its meanings (Reference Shirane2019: 462). He argues that as a convention, kigo act as a kind of anchor, connecting the poem to a “historical and social moment” (Reference Shirane2019: 461) and linking to a “highly encoded” understanding of the seasons (Reference Shirane2019: 463). Because the form is so highly encoded, there are a plethora of books available to haiku poets, especially saijiki, reference books of kigo and anthologies, forming a densely intertextual landscape. In the Western sense, a book of poetry words seems like the antithesis of creativity—a stifling set of conventions; however, in practice, books can be sources of inspiration. This is important not only in composition but also for interpretation; reading and appreciation depend on an understanding of those encoded conventions.

Haiku are often presented as crystalized works, especially those that reflect a “haiku moment” (Yasuda Reference Yasuda2011), with a single author, but the skill to produce them is often honed through years of participation in groups or by working with a mentor. However, fitting everyday language into the 5/7/5 syllable form is no easy task. Shirane observes, “the haiku poet does not have to be highly talented to put together a seven syllable seasonal word plus ten more syllables, but creating quality haiku is extremely difficult” (Shirane Reference Shirane2019: 462). Whether conceived of as poetry or wordplay, haiku often necessitates the existence of a community through which knowledge is transmitted from generation to generation. Shirane writes, “The difference between the amateur (every person as poet) and the professional is bridged in Japan by haiku communities and haiku teachers; most haiku poets (amateurs) belong to a local haiku group, each with a master teacher, who corrects and revises the haiku and makes sure that the rules (such as the use of seasonal words and cutting) are followed properly. The haiku master is a teacher and a judge, selecting the best ones and showing how each haiku can be improved” (Reference Shirane2019: 465). A good illustration of this can be found in the popular TV show Purebato (Pressure Battle), which stages a haiku competition between idols. Contestants are given a theme and asked to compose a poem, which is then shown and discussed. They are ranked by a judge, Itsuki Natsui, who wears a kimono and improves the contestants’ poems on a whiteboard using a red marker. Occasionally, Itsuki beams a smile and says “No corrections” (shūsei nashi). The losing poem is dramatically dropped into a shredder in the last moments of the TV show. Despite the theatrics, this reflects the normative practice of a teacher showing how to improve a poem. It also shows different assumptions about haiku as creative works. The expectations are that anyone can make a haiku, but it can probably be improved. Through this, we see that, unlike the ideology of the work of a genius, there is a sense that haiku is a form that can be improved through the input of others.

Haiku, and haikai before it, is a poetic form that cuts across and blurs distinctions of social class. Shirane argues that what he calls haikai imagination “emerged from the intersection between the new, popular, largely urban, commoner- and samurai-based cultures…” and “the residual classical traditions which haikai and other popular genres parodied, transformed, and translated into contemporary language and forms” (Reference Shirane1998: 2). Furthermore, he identifies a “sharp dualism” between the different cultural past of aristocrats and commoners, which created “the constant interaction of a vertical axis, based on the perceived notion of a cultural past… With a horizontal axis, based on contemporary urban commoner life and a new social order” (Reference Shirane1998: 5). Shirane’s formulation is important because it shows a socially located imaginary that forms a reservoir or repertoire of practice and images. Furthermore, this cutting across social boundaries is still a feature of haiku culture. People frequently tell me that in the Edo period, haiku were written by working-class people who had little time, resulting in the abbreviated form. This is possibly true though they probably would not have used the term haiku. Perhaps this folk theory tells us more about the people who repeat it today—they tend to be members of the professional or working classes. The haiku group in which I conducted participant observation for this article included people from several professions. These amateur poetry enthusiasts ranged from freeters (freelance workers) to busy media professionals, and from publishers to retirees.

There is a contradiction at the heart of haiku—there is a heritage of collective composition but also a Western influence in the form of the idea of a single author. Not only have and do groups play an important role in poetry gatherings in Japan, but scoring also plays a significant role. One of the most pivotal figures in the history of haiku was Shiki Masaoka, who is remembered for elevating haiku by lifting this 5/7/5 form above banality (tsunami-cho) using realism. Okazaki writes that Shiki’s method was to render the object in an “objective” and “concrete expression” inflected with “modern intellectuality” (Okazaki, Reference Okazaki1955: 423). While he is remembered as the reformist who extracted hokku from renga, where it was part of a chain of verses, and situated it within a framework of individual authorship, he also held poetry gatherings in his Negishi residence where the poems were scored, using a method called gosen (互選), literally “peer selection.” The first meeting Shiki held in January of Meiji 26 (1893) started with 10 topics based on the New Year, and over the second and third gatherings, there were 12 further themes. The poem that ranked top took first place, but the subsequent ranking was decided by tallying the previous three meetings’ points. Shiki made a chart for each meeting, showing the points awarded and who awarded whom, tracing a trend. Wada argues that this was a rational way of scoring (Reference Wada and Masaoka1977: 842). Perhaps in keeping with Shiki’s interest in authorship, this way of scoring seems weighted to evaluate the skills of the poet, rather than the merits of the poem.

Collective poetry-writing practices defy easy distinctions between oral and written and traditional and modern, and from milk cartons to bus advertisements, haiku is featured in daily life in Japan. We know from Yemen (Caton Reference Caton1990) and Egypt (Abu-Lughod Reference Abu-Lughod1986), especially in the case of oral poetry distributed on cassette tapes (Miller Reference Miller2002), that the composition of poetry often defies categorization of author and audience, but surprisingly this phenomenon is not the object of significant anthropological study in Japan. Studies of haiku often note the importance of poetry groups, but provide little detail. Furthermore, the social worlds of Japanese poetry are worth studying because these groups are exceptionally common, and it is possible to analyze through their processes of community-making, intergenerational cultural exchange, and social reproduction. And yet these are not only sites of communality and collaborative creativity but also of competition to produce an excellent poem. Frequently they are scored or ranked. Haiku competitions are common, such as “haiku sumo” (kuzumō) and ku-awase (Tuck Reference Tuck2018: 130), with a long history. Now, there are many places to submit a poem, ranging from Itōen’s Oi Ocha Shinhaiku Taishō to the Utakai Hajime held by the Imperial Household Agency each New Year’s Day. Studies of Japanese literature and social history have detailed the networks of haikai and renga networks (Tuck Reference Tuck2018), underscoring the political and social meanings of these groups. This research builds upon these works to sketch a groundwork for ethnographic approaches to haiku as a creative practice in a changing milieu.

The community I found in Jimbocho, populated by publishers, booksellers, advertisers, and office workers, is an ideal place to begin an ethnography of this form of creative culture in Japan. Decidedly informal, this community takes itself seriously, even though they appear to object to this very same seriousness. “We are just playing,” or “You should go see a real haiku group,” they explain. Yet, play can also be a mode of building skills. With the history of haiku in mind, I try to take seriously this form of play and explore how relational creativity unfolds in this setting.

Poetry in practice: contextualizing haiku production

Ideologies of creativity are inescapable. As Wilf writes, “Recurrent…ideologies conceptualize creativity as the solitary, ex nihilo creation of products of self-evident and universal value—most emblematically in the field of art—by highly exceptionally and gifted individuals” (Wilf Reference Wilf2014: 398). He argues that these ideologies obfuscate three dimensions of creativity that ethnographic analysis can elucidate: first, that of “creative processes as communicative, interactional, and improvisational events…,” second, “the role of socialization, apprenticeship, and pedagogy/learning in the making of creative individuals,” and third, “the processes by which certain objects and individuals are recognized, constructed, and authenticated as bearers and exemplars of creativity and thus acquire their value” (Reference Wilf2014: 398). The form of creative practice analyzed below relates to all of these aspects, but the process of scoring relates directly to this third aspect of recognition.

In some sense, groups such as the one I study can be seen as a type of what Bourdieu called “cultural intermediaries,” figures from the petite bourgeoisie that shape the tastes and consumption patterns of others (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1984: 325–326). In particular, this group shares what he describes as the “…conspicuous refusal of the heavy didactic and gray, impersonal, tedious pedantry, which are the counterpart or external sign of institutional competence…” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1984: 326). Much of their efforts as a group take the form of critique and commentary, offering feedback on how to improve or pointing out what does not work in the composition. This group also relies on certain aspects of institutionalized haiku, such as utilizing saijiki (seasonal almanacs). As Coates has shown, such cultural intermediaries not only broker the consumption of cultural products but also shade into production (Coates Reference Coates, Ari and Wong2021). In this group, they both mediate and produce.

Despite Shiki’s intervention, which elevated haiku to its modern form, breaking and remaking the canon, adding Western-inspired realism, and adapting it to the fast-changing times of the steam engine, global trade, the printing press, and mass culture, it has retained a tendency to be composed in groups. Haiku is a genre that has changed with the times, but how does one learn to compose a good one? Why turn composition into a competition? This ethnographic account begins to sketch how, even before the labor-intensive step of circulation, poets in Japan often rely on collaborative labor, often overseen by a sensei (teacher) and or senpai (elders), to hone skills and refine poems. This stands in contrast to the contemporary understanding of poetry in the West, which commonly reflects the ideology of a solitary genius (Wilf Reference Wilf2010, Reference Wilf2012, Reference Wilf2014) but also reflects a rules-are-meant-to-be-broken stance—the understanding that it is one’s sense and voice, not form, rules, or the feedback of others, that make a poem a poem. My question is: how do my informants navigate the contradictions between modern reality and traditional art form and the individualistic drive for creation and collective critique and make poetry writing both personal and collective, traditional yet contemporary? Furthermore, this group is profoundly shaped by feedback and scoring. How does this scoring system contribute to haiku practice?

Jimbocho nightlife as setting for creative practice

Jimbocho is known as the largest used book town in the world, and it is also home to numerous publishers and book-related businesses. The people who spend their time in Jimbocho’s nightlife are overwhelmingly employed in media-related industries—publishers, TV producers, advertisers, manga editors, and booksellers. At the end of the year, one publisher hands out calendars branded with his music magazine. There are a few semi-regulars with more working-class jobs, such as a shoe salesperson and a call center employee. However, most of the regulars deal with the written word in their daily working lives—yearbooks, TV program scenarios, edited volumes, and essays. The haiku writing group is also a place where ideas come to fruition, texts are suggested and solicited, and all kinds of professional information circulates. For example, one evening, a young woman beginning a career in advertising asked for the advice of a mid-career advertiser after the haiku activities had ended. This mixing of work and leisure was not out of character; professional identity is an important aspect of social standing, even though the haiku writing group is marked as a place devoted to relaxation. This is not a place that tries to be important. Shinpindo and others waved their hands to indicate “no” when I asked if this was a bundan bā—a literary bar—and one outsider joked that they were pseudo-intellectuals at best.

Zugaikotsu’s bar

Anyone can come to Zugaikotsu’s, but new customers are rare. Almost everyone has a connection to the bar or has received some sort of verbal invitation before entering. At one gathering, someone asked me how I was introduced; when I explained a chain of introductions, he seemed to relax and accept my presence. Such introductions are not required but are preferred. One evening, someone who had evidently come to pick up women was politely discouraged from coming back, and he never returned. On rare occasions, unwanted customers were bounced, especially those who had a reputation for not paying their bills. However, newcomers joining the haiku group were warmly welcomed, and one younger woman even brought her parents. The bar is also a space for gifts and obligations, where things are frequently exchanged. People bring souvenirs not only for the owner but also for other customers to enjoy, a common characteristic of a bar with a steady group of regular customers.

Many of these regular customers who participate in or organize the haiku group had some extant relationship to the Jimbocho area or literature more broadly. For example, Shinpindo works in one of the bookstores during the day, inputting books onto the web store and working the register. She became a regular of Zugaikotsu’s when it was run by Aruki, the second owner and her immediate predecessor. When he decided to retire, she took over the business. Asked why, she remarked that she had fallen in love with Jimbocho. Between her day job and work at the bar, she spends most of her time in the neighborhood, which, for her, is not only a place of work but also socialization. The only place she seems happier is on a fishing boat. She is the linchpin of the community, doing a phenomenal amount of work to run the bar and keep the community spinning; in addition to the haiku night, there are bi-monthly camping trips, and there are frequent fishing trips on Tokyo Bay. For the media workers and bookstore owners who gather here, this seems to be the orienting community of their lives, an important third space (Oldenburg Reference Oldenburg1999).

It is not uncommon for groups to self-publish magazines about their activities. The haiku night has been held for over 15 years, from the first meeting on May 25, 2007. Iwashi, who works part-time at Zugaikotsus, remarked that the first submissions were not good (hidokatta), such as “Zugaikotsu, ashita wa oremo, Zugaikotsu.” “Zugaikotsu, tomorrow I too will go, Zugaikotsu.” This poem was by Kōchiyama Sōshun (a pen name based on a 1936 drama directed by Yamanaka Sadao), and the composition could be described as low effort. The first kadai (theme) was sake, perhaps obvious for a bar but which could also be interpreted as Baisho-inspired; however, the selection may also have generated more low-effort contributions from writers who were more sake-enthusiasts than poetry-enthusiasts. Iwashi is a retiree from the publishing industry, so she has been around the neighborhood and the bar for decades and has the professional experience to assess the quality of submissions to the haiku night. Yet informality remains an important element of the haiku group. Even newcomers and foreigners, such as me, are welcome to submit a haiku, and there is an element of playfulness and performativity to the process.

The haiku group: creativity and constraint in practice

For each meeting of the haiku group, a topic is chosen in advance. Participants have roughly 2 months to compose their submissions. Haiku are submitted in advance to an email account, and Shinpindo compiles them into one A3-sized piece of paper. This paper is distributed on the group meeting day when people arrive at the bar. Usually, there are 13 haiku to a row, without author names. Most people use pennames (haigo) for haiku, which are used to identify authorship and are revealed only in the final version of the month’s submissions, distributed after scoring. The paper is titled with the name of the group, Zugaikotsu haiku kai, the iteration of the meeting (for example, “89th”), the date, and the subject (kendai). Over 15 years, the haiku group has been held about 95 times, once every 2 months or so.

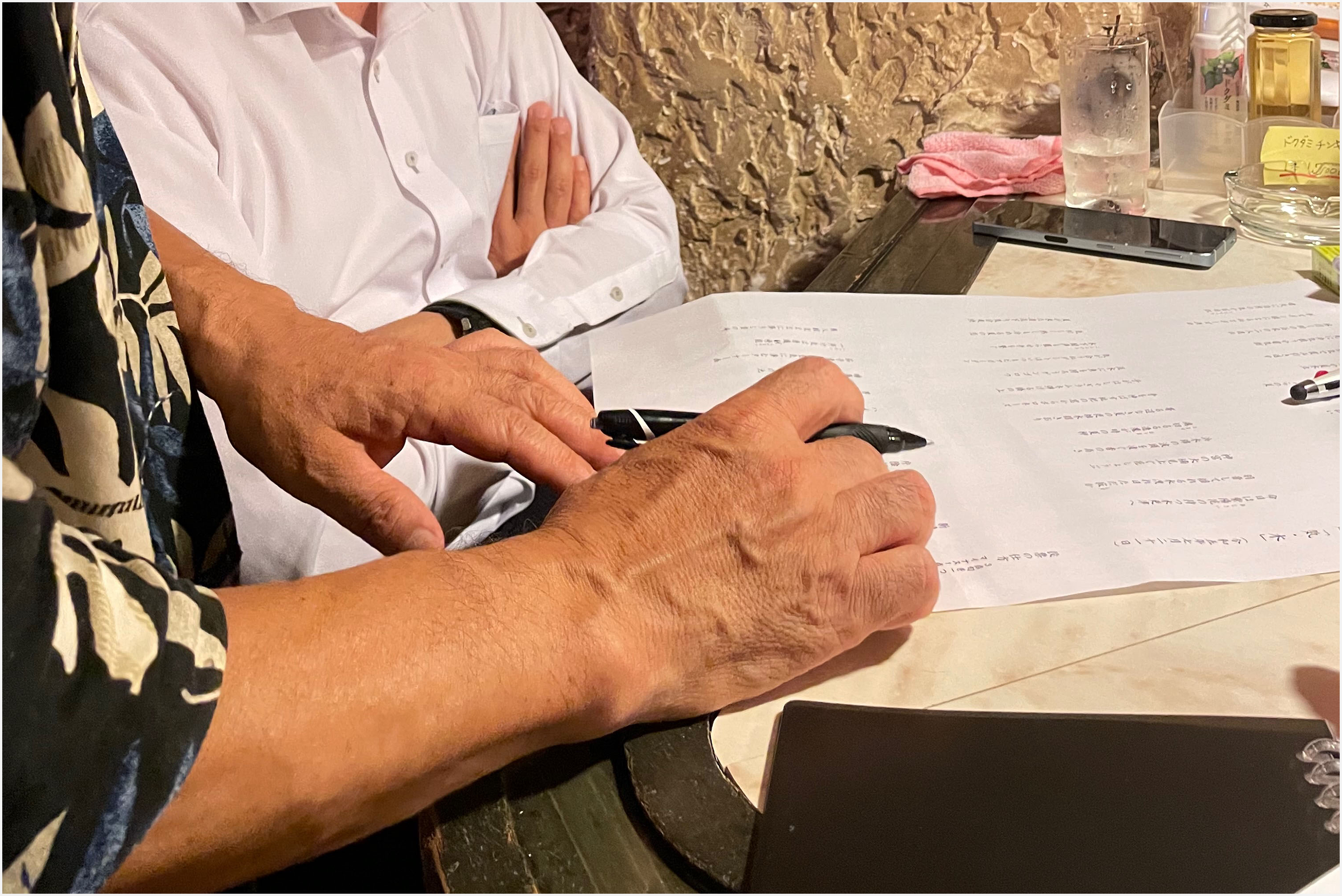

The rules are given in fine print on the edge of the haiku sheet: “Give three points to one poem, two points to two poems, and one point each to three poems. Also, do not forget to give one poem a minus point.” The lowest-scoring poem is given the “minus award.” As the meeting starts, people slowly file in, take a page of poems, and find a seat. Smokers light their cigarettes, and everyone starts with a bottle of beer, which they pour out into a tiny glass. Conversation is at a minimum as everyone distributes their points, marking their sheet. Once marked, the patron hands their sheet off to the person who is tallying the points—usually Aruki. Once all the marks have been tallied, he writes the total points on a master sheet. He then passes a version with the tally but without the poets’ names, to the person reading them out (yomiage). He writes the author’s haigo and the final tally on the master sheet and copies it at a nearby convenience store. These copies are distributed to everyone at the end.

Who is to serve as yomiage that evening is decided by one of the oldest jōren, who is a natural leader and often the master of ceremonies. One by one, three or four old hands read off a row of poems. There is a rough script for how poems should be read out. The yomiage reads a poem twice in the same cadence. At the end, they say “hai” or “itadakimashita,” indicating the poem has been received. Then, they reveal how many points the poem scored. Sometimes, they offer some commentary. Finally, they politely ask who wrote it (“Donata donata deshō ka?”). The poet then speaks up to claim it. People stay seated. Commentary and banter follow. Usually, from the beginning of one poem to the reading of the next, three to five minutes pass—some poems spark extended commentary. When poems are well received, group members may chime in, “I gave you three points” or “I also gave one.” If the poet is out of town, Shinpindo reveals the name of the author. This style of conducting a haiku group, with authors’ names hidden, is called nanori. This is usually a raucous affair as multiple people chime in to comment, praise, and joke. The next kendai is decided at the end of the haiku-kai. It is a process of negotiation between finding a topic that fits with the season and a Chinese character with multiple readings. The topic should not be too constraining nor too open-ended.

Scoring points: high- and low-scoring poems

Despite the common image of the solitary poet discussed above, all poetry is relational to some degree because it draws on shared words, conventions, and images. Haiku gatherings, such as the one at Zugaikotsu’s, bring this relational quality to the forefront because they ground the form explicitly in a social context. Here, haiku are not only composed within a cultural and seasonal framework but also have an audience of friends and acquaintances in mind. This forum also enables about five minutes of feedback or lighthearted commentary about each poem, providing feedback on individual poems, including ideas for how the poem could be improved or rearranged. On top of that, criticism and critique also allow people to practice and hone their abilities. Because critique takes place in a conversational forum, it is easier for beginners to comment. This process of collective critique allows participants to practice and refine their own creative discernment, which is an important but often overlooked aspect of artistic growth.

The 89th meeting of the haiku group was held on November 19, 2021. The theme for that evening was the character for rice. In Japanese, many kanji have multiple readings, which lends them to wordplay. This character is read (voiced) kome (mostly as the noun for rice), bei (often as a prefix, as in Beikoku, America), or yone (mostly as a place name), but it is also an ateji or improvised kanji meaning meter. In addition, in this group, if the character is a radical (component stroke) for another character, that character is also permissible; in this sense, the kendai is both literal and flexible. The word raisu (rice) was also permissible. That night, there were 44 haiku submitted. The paper arranged them in three rows of 15, 15, and 14. Reading through them and bantering took about 2 hours, not including the time for scoring.

One of the third-ranked poems was by Nekotei, which garnered nine points from four people:

冬の朝米とぐ音に二度寝決め

Fuyu no asa/ kome togu oto ni/ nidonekime

“Winter morning/ the sound of rice being washed/ deciding to sleep again”

This poem, which shares the kigo with the winning poem, seemed nostalgic and formal, evoking a time past when someone’s mother was washing rice, when the poet had the option of rolling over and going back to sleep. The ending phrase, nidonekime, stacks kanji in a way that is unlikely to be used in spoken Japanese. Contrary to my interpretation, someone chimed that this was somewhat erotic, “eroppoi,” implying that rather than drifting back to sleep, a couple might have gone back to bed for other reasons. This form of banter and critique also allows participants to compare interpretations.

The other third-ranked poem was by Harumi, which garnered nine points from five different people:

米つぶも大きく見えるお食い初め

Kome tsubu mo/ ōkikumieru/ okuizome

Even the grains of rice/ look large/ starting to chow down

This poem, written by a young woman who is a newcomer to the group, evokes a hungry person focusing on their food as they raise it to their mouth. It is playful and lighthearted. Compared with the other third-ranking poem, it is much closer to spoken Japanese and avoids using the kanji for grain (tsubu). There may be many reasons for this; the kanji for tsubu contains the radical for rice, and the author may have wanted to avoid doubling the kendai—doing so is usually frowned upon.

The second-ranking poem by Mugen garnered 10 points. Four people voted for it, meaning that he racked up several two- or three-point votes.

鴨の陣たなびく波紋二米メートル

Kamo no jin/ tanabiku hamon/ ni mētoru

A phalanx of ducks/ trailing a pattern/ two meters

Mugen often aims to incorporate unusual usages or meanings of the kendai. This poem uses the kanji as an ateji for meter. This poem is rather solemn and seems to reflect the late autumn, yet many remarked that it was a more modern haiku because of its use of an ateji.

Most high-ranking poems score a couple of two- or three-point votes, but sometimes there are exceptions. The winning poem, by Shinpindo, was awarded 13 points. The list of who voted for it was omitted from the tally sheet because it racked up several one-point votes from various people, and there was not enough space to list them all. Unlike Mugen’s poem, which four people gave two- or three-point votes to, Shinpindo won because she racked up numerous one-point votes. In a sense, the evaluation is completely different from Mugen’s; it might be said that he was evaluated highly for something unique by a few people, while Shinpindo’s poem resonated with many people.

薄粥に光溢れる冬の朝

Usugayu ni/ hikariafurreru/ fuyuno asa

Brimming over with light/ thin congee/ winter morning

Compared with the last poem, this one is much more conventional. Congee is both a form of rice, and the Chinese character contains the radical in the middle. This poem garnered many points in part because it is about a comfort food; the image is also readily understood. It is worth noting that Nekotei’s poem has the same kigo, fuyunoasa, winter’s morning, at the beginning rather than the end of the poem. Frequently, I have been advised to swap the first five and last five syllables to see if that makes a better poem. Often, people suggest ways of tinkering.

I submitted the following poem:

米国や紅葉の香り鹿の尻尾

Beikokuya/ koyo no kaori/ shika no shippo

America!/ Smell of autumn leaves/ deer’s white tail

This was written following a customer’s advice; ya, the cutting word, is used to set the scene. I chose the kigo, kōyō, autumn leaves, first. Then, I drew inspiration from sight on a recent visit to my hometown—a whitetail deer. This poem scored zero points. Among other reasons, I had ineptly included two kigo, which breaks a haiku rule; deer are also an autumn kigo. There were other problems. Someone suggested that I replace kōyō with ochiba, fallen leaves. To be sure, fallen leaves are more likely to have fragrance than leaves turning autumn colors still on the tree, kōyō. “Well,” someone remarked, “she was trying to sing of the American fall.”

Sometimes, poets give concrete suggestions, such as changing words or the word order. In addition, it seems essential to strike an emotional or nostalgic chord with the listeners’ own experiences and memories to score points. Not only should poems be structured well, but they should take up a topic that can resonate with many people, not just the author. After another low-ranking poem, someone joked, “This did not echo with our hearts, Miwazaru.” This kind of advice does not help improve that poem in terms of concrete suggestions, but it does hint at what does not work when efforts fall short.

Because of the brevity of haiku, context is often thin or nonexistent. A common critique of a poem is that it is too dependent on context, which also points to cases where the haiku failed to connect to the shared repertoire of the audience. An example of this is a poem that was composed about remembering the thick flavor of steamed mackerel. It scored only one point. When the poet’s name was revealed, someone said, “Knowing that, probably he was writing about his late wife’s steamed mackerel,” someone mused with compassion. “Seems only the poet would get that one,” another replied. This was a case where the composition was solid, but not exceptional, but it gained something when the larger social context was revealed. Without the individual’s name and the context, it lost something. Conversely, one member of this group was dying of cancer during this fieldwork; his poems were tight compositions that frequently scored in the top three. They were somber or celebrated small pleasures of being alive; they were all the more heartrending when his name was revealed. One old hand who often reads out the points almost always says “nanto ichii” (somehow, this one achieved first rank), before asking who wrote it. Authorship is on display—part of the game would be lost without knowing who composed what.

Poems judged unskillful or unoriginal scored low and generated joking but also helpful commentary from the listeners and authors alike. Responding to criticism, some joked, “I managed to put the character [of the kendai] in twice!” Generally, doing so would be frowned upon. Some critics focus on the mundane, “This was rather obvious,” or the vulgar, “I don’t want to read stuff like this.” The lowest-ranking poem, which scored negative two, was by Kawadori-san, who seems to enjoy being the butt of the joke. He used the owner’s name in the poem; no one responded well because it was too on the nose. “This isn’t haiku,” the owner complained. It is possible to make 5/7/5 combinations that are too close to being everyday language, falling short of becoming haiku. Another poorly scoring poem was critiqued for using ya at the end: “It doesn’t go there.” As a cutting word, ya should cut in two, not cut off.

At the end, the person reading out the poems and scores remarked, “Gokuro-sama deshita” (thanks for your efforts) and “Benkyo ninarimashita” (I learned much from this), suggesting that even bad poems critically received are perceived to contribute something to the group atmosphere and the individual members’ enskillment. While this game is understood as fun, it provides a forum for relational creativity on several levels. Through scoring others’ poems, participants can practice their critical skills and have the opportunity to evaluate work that has not been published. They are also able to hear criticism of others, allowing for the comparison of different interpretations. Of course, a poet may improve or try different things, but it also provides a space to practice criticism; learning what works and what does not is a basis for one’s practice.

Critique and creativity

I asked participants many times, why are the poems scored? The answer was always the same: “Because it is fun.” What is the fun of ranking things? Selecting the best poems is a key feature of haiku culture, especially if they are intended for publication. Good poems are often selected by a teacher, as is the case in the popular TV show Purebato. However, in this case, the participants do the work of scoring. Here, the act of ranking is a form of play rooted in discernment, and while it is taken as a game, it is a serious one. To score the haiku, one must have a sense of what a good haiku is and is not. This is especially important as one must have a sense of what makes a “good” haiku before cracking jokes or risk embarrassment. The selection process is also a building block of the play. Reading carefully and forming an opinion or critique becomes the building block for banter. A knowledge of the personalities involved is also important. The structure of revealing the score creates a stage in front of everyone for sharing memories and impressions. In particular, those who award a minus point are frequently called on to explain their reasons. At the beginning of the group, the winner used to receive a bottle of alcohol, but now no prize is given. The overall winner typically beams with pride; the winner of the minus award may bask in the attention, but they may also be dismayed. This is a much less hierarchical and more playful model than the one led by a sensei. Scoring flips the script; instead of an instructor choosing which poems are the best, everyone has a vote, even people who have not contributed a poem, and everyone is free to comment. Since everyone participates in scoring, it also means that several people must see the value in a composition, not just a sensei.

In interviews, no one had a clear answer as to why the haiku group scores poems or why they use the nanori method. I asked one old hand, Ken’ichi (whose name is based on kendo, his primary hobby), who has attended every meeting. He said that the scoring system is a way to check what is haiku and what is not, which suggests that adherence to the form is not the only thing that decides whether or not something is a haiku. This group allows compositions that are crass or lacking sense. He gave the example of erotic poems, which some would not dignify as haiku. Hinganai—unrefined things—are accepted but tend not to win. Purists might say that this category of poems might better be called senryu, which shares the 5/7/5 form but deals with human foibles and follies. Ken’ichi’s comment sheds light on one pragmatic function of the group and the game; it allows participants to try out what is haiku or not, allowing them to test their composition against the judgement of multiple others. This emphasis on testing what is and is not haiku is a key facet of the group’s collaborative creativity.

Fun is the explaination for much of the haiku gathering’s rules and processes.. Ken’ichi said that awarding points was a half-joking matter; some people use simple criteria such as, “This doesn’t fit my interests.” For example, there is a running joke about Hiace minivans. These minivans are often used by booksellers when they purchase libraries from customers. It is easy to compose a five-syllable phrase around this brand name, for instance, “haiesu” and the kiriji “ya.” Someone always votes against these compositions because she dislikes minivans in general. There is always a haiku about Hiace, but it is usually written by a different person each time; the poets in on the joke always congratulate the poet who did it this time. This kind of practice of passing around a word that must be incorporated each time is also a kind of remixing or imposing another constraint. Scoring, Ken’ichi said, is not always a process of thinking deeply, it is just a question of what you like. He explained that he had never given a minus point, thinking it was discourteous. However, he said it was fun to watch others give minus points and to hear their reasons for doing so.

While each point carries the same numerical weight, they are not all the same. On the final sheet, the name (haigo) of the point awarder is given. While this may serve the purpose of transparency or fairness, it also means that the poet can understand who evaluated them and how. For instance, some first-ranked poems win by accumulating many one-point votes, meaning the poem achieved a broad but perhaps shallow appeal. Some first-ranked poems accumulate several three-point votes. In these situations, the name of the awarder conveys information about the awarder that cannot be conveyed in numbers. People will say things such as, “one point from you is worth 10.” This may reflect the strengths of friendships in the group, but I would argue that it also carries the mark of the evaluator, the sense of discernment. There is a social structure here that encourages creativity, teaching bit by bit how to compose a better poem. Put another way, this shows a process of creativity where consumption and reception are closely imbricated in the same system and revealed through the framework of scoring. Therefore, what seems to be an irreverent game is in fact a forum for trying out haiku. Simple on its face, the form is difficult to master—these kinds of gatherings provide a structure, grounded in the expertise of the participants, to write and see what works.

From the perspective of relational creativity, this gathering with its scoring system provides a forum for trying out haiku, trying to rank, and trying to improve. As Ken’ichi said, people want to aim for the best—to try. In this sense, the gathering becomes a place to try poems in multiple senses of the word. Participants can try to take the top spot, they can try to take the minus award (which some people do), and they can try out whether a composition is haiku or not. If we see the competition as a game, there are many ways to play and win. What one might try out as a poem to take the top spot would (probably) not get the minus award. Making a composition that others would recognize as bad also takes knowledge. If one was trying to take the minus award, one might employ puns or dad jokes (dajare). Trying can take the form of confirming what compositions fit in terms of content and form. Yet trying in the second sense, either for first or last place, is also an aim that hones skills. Paradoxically, while this is a game with a top scorer and a low scorer, it is also an open-ended forum for people to practice and improve, underpinned by relational creativity.

The first time I participated, my poem was about fishing near Kanazawa Hakkei on stormy seas and looking with pride at my tiny catch. Shinpindo, some booksellers, and I had gone fishing. I caught a tiny red fish that no one could name. The man who read aloud the row my poem was in remarked with disdain, “This poem lacks a kigo.” When I claimed it, he gazed over the rims of his glasses at me and said sternly, “Please, someone explain kigo to her.” Someone turned to me and said, “Have you heard of Shiki Masaoka? Well, he liked making up rules, and he made up kigo.” This explanation is not entirely correct. Kigo, terms that indicate the season, far predate Shiki’s consolidation of the haiku form. Some are straightforward, such as flowers, weather phenomena, or foods. Others are more oblique, such as the act of hanging a blanket on the balcony, which could conceivably happen anytime during the year, but signals winter. The man who read my poem aloud has the reputation of being the kigo keisatsu (“the kigo police”). Any poem that fits the 5/7/5 pattern is accepted for the group, even if it lacks a kigo, but it is unlikely to score highly without conforming to the rules of seasonality. The proper use of kigo is frequently the subject of critique, suggestions, and banter. While the rule is not written, kigo must reflect the season during which the group meeting is held; for example, one would not use a winter kigo during a summer meeting. This means that everyone must compose within the same seasonal framework.

Despite adherence to or deviation from formality, people often score points for reasons unrelated to the rules, often grounded in the sociality of the group. On my second attempt, I submitted the following poem:

白塩を砂のわき立ち金の貝

Shiroshio o/ tsuno no waki tachi/ kin no kai

White salt onto/ bubbles in the sand/ a golden clam stands up

Shinpindo frequently organizes fishing trips, and we had been clam-digging. I was fascinated with the method of coaxing the clams out of the sand; by pouring salt on a place where bubbles well up from the sand, the sodium tricks the clam into thinking the tide has come back in, and they pop out of the sand. It scored well because people assumed Shinpindo had written it.

Instead, Shinpindo wrote:

太刀魚よ空飛べ銀の風となり

Tachiuo yo/ sora tobe gin no/ kaze to nari

A swordfish!/ flying towards the sky/ becoming silver wind

We had recently been fishing, and a glistening, silver fish had jumped into the boat. She changed the fish species to fit the season; the one we saw was not tachiou. Since Shinpindo is beloved by her customers and everyone knows she loves fishing, fish-themed poems tend to do well, whether or not they contain a kigo. In this haiku, tachiuo is the kigo. In many cases, poems that reflect a shared repertoire of images are well received by the group. Often, participants have a sense of who wrote what, and they award points to friends. Hiding the names of the poets and revealing them later reduces this, but people often have a sense of the author’s voice. It is therefore not only the merits of the poem but also the social context of the group that can lead to points, suggesting that relations are as heavily weighted as creativity in assessing the work.

Approaches to composition: help and advice as relational creativity

For several months, I could not score a single point, which led me to ask for help. How to write a haiku that would gain even a point? A regular customer at the bookstore where I worked gave me a standard set of advice. First, use ya as a kireji (cutting word), and let this first phrase do the heavy lifting to set a scene. Second, start composing from the kigo rather than trying to incorporate it later. This customer writes haiku in English, and he said this formula would produce decent haiku. I thought this sounded doable.

I showed my notes from that conversation to Aruki, who covered them with his hand. “Don’t follow this advice! You cannot make anything interesting with this!” He suggested that instead, I focus on trying to capture a moment. From memory, he quoted, “Yuruyakani/ kite hito to au/ hotaru no ya: Loosely/ wearing, meeting a person and/ evening of fireflies” by Katsura Nobuko (1914–2004). He described this as a poem about a woman tying on a yukata (summer kimono) loosely and heading out for a romantic rendezvous. Fireflies are associated with romantic love and are a kigo for summer. The poem does not explicitly mention wearing a yukata, but it is implied. He mimed the collar of a yukata: “You can tie it loosely around the neck.” He mimed the loose neck of the yukata and a hand sliding inside; he said it conveyed both the summer heat and the expectations of a love affair. “Capture a moment,” he said.

One non-haiku night, Mugen and I were seated next to each other. I asked his advice on how to compose haiku. He took out a book of photographs by Domon Ken (1909–1990) and said, “Haiku are like a montage, kind of like photographs.” He had brought the book specifically hoping to run into me to illustrate his approach to haiku. He had me find a photograph that interested me and compose a haiku on the spot. In moments such as these, when people compose together, they extend a hand and count syllables on their fingers: flexing thumb, index, middle, ring finger, and pinkie to count five, unflexing pinkie and ring finger for seven, and opening their hands to start counting five again. Looking at details of Domon’s pictures, which often feature children and Tokyo street scenes, counting out syllables on our left hands, we worked out several verses.

The varying advice that I received reflects several approaches to composing haiku. The first focused on a standard—clear advice on using kigo and kiriji which most people could replicate—excellent for a beginner. However, the advice of the patrons of the bar focused on capturing a moment or drawing inspiration from other poems or photographs; their advice was calibrated to making haiku that could win points. These varied approaches highlight different relational dynamics within the haiku community. The bookstore customer’s advice would get anyone over the starting line, while the two patrons focused more on crafting poems that could perform well in the bar’s competition; one focused on inspiration, while another focused on practice. Enabling participation and honing skills for success are both important facets of participation in such groups.

Everyone seems to carry around a repertoire of haiku in their head that they particularly like, refer to, and draw on to compose their own. Knowing the effects that others have been able to achieve can be a source of inspiration or ideas for how to tinker. Citing past works is also a form of creativity, exploring how to echo without imitating. Unlike normative Western poetry readings in this group, one does not read one’s own poem. The exception to this is when the yomiage happens to read their own poem; however, this is unintentional, and no one vies to be the yomiage for their own poem. Therefore, most people can hear their poem read aloud by another person, who may or not “get it.” While there have been some defections, and not everyone attends every meeting, the group is remarkably consistent. During my participant observation, no one quit. This suggests that simply turning up to the haiku group is something that participants feel some benefit from, and the insistence on the importance of the presence, evaluation, and inspiration provided by others seems to suggest that that benefit is relational. In these ways, this ethnography of a self-described unusual haiku group offers a portrait of creativity that draws on experience and self-cultivation but also creativity honed through the social practice of a game and composing together.

Conclusion: why compose haiku in groups?

Returning to the question posed at the beginning of this essay, because the haiku group is framed as a lighthearted gathering that is merely a game, participants can negotiate tradition and a changing form together. Since the gathering is conducted as a game, which everyone involved contrasts with a “real haiku gathering,” an open space of easily given and easily received critique is created. Critique, which can be intimidating and a source of stress, is reframed as joking and fun. The rules of the game also mean the outcome is uncertain, all but barring a teacher’s pet or a favored circle from dominating.

Tim Ingold, drawing on Wiseman, Bergson, and Whitehead, argues for a reevaluation of creativity, moving away from what he calls the mythology of the “figure of the artist as a creative genius” that has flourished since the Renaissance (Reference Ingold2021: 25) to instead see creativity and creation together, “to invent…is not to create a world but actively to participate from inside the world’s ceaseless creation of itself—and since we belong to the world, of ourselves as well. It is once again to reunite creator and created in one act” (Reference Ingold2021: 27–28). This understanding centers a living, practicing, growing person rather than an ideal type. Furthermore, rather than privileging the finished work and appraising its originality, it focuses on the process in the context of life. Coupling this definition with the idea of relational creativity, we can see how these poems are deeply tied to the social setting. And the social setting has, to extend Ingold’s metaphor, taken on a life of its own.

If we view the haiku group not as a one-night event but as a process unfolding over 2 months, a different view of creativity comes into focus. Participants think about the kendai, which involves both wordplay and manipulating the image, and they collect haiku images that fit the genre and the season. On their own, they may make several attempts to work out a haiku that is sufficient to submit. Somehow, readers in this group can identify when a haiku is overworked—poems should have a quality of coming together effortlessly. In the meantime, they may hang out in the bar on a normal night, and the conversation might turn to haiku. However, poets draft their poems alone.

Haiku is particularly dependent on interpretation, as Shirane argues. Interpretation becomes apparent in the scoring of the competition, which I argue is an important site of relational creativity (Coates and Coates, this issue). Scoring the poem opens it up to the interpretation of many people, rather than just one, and it visualizes the appraisal of others. It distributes the work of interpretation among many people and the tally points to the wide appeal of the poem. Even the minus award is socially recognizable. Poets learn what works and what does not through a fun evening of jokes, accumulating points, and listening to criticism. Paradoxically, the stakes are lower because this group is scored as if a game and conducted with levity. This gives it the atmosphere that anyone can join—an invitation into a space of comradery. No one is an expert, and everyone is trying together. While people can and do study and write haiku independently, this game format cannot be done alone. The game format provides a structure for this group to practice a form of relational creativity.

As Wilf suggested, the ethnographic study of creativity can yield new understandings, especially on the process through which creative products are recognized as such. This analysis has centered on how this group serves as a forum for trying, both trying out haiku to see how others evaluate them and second, through trying in the sense of achieving personal poetic aims, realized through a form of play. The group is a site where participants can practice creativity together, both over several months and during the event. Indeed, without such social spaces of creativity for poetic composition, something fundamentally important would be lost.

To extend Shirane’s idea of haikai imaginary, we might speak of a haiku imaginary enacted within relational creativity; rules and conventions are a key part of this imaginary, but it is animated by the living, changing sense of other poets. What is key in this venue is the trying of poems against the sensibilities of other practitioners. Recall Shiki’s poetry gatherings mentioned above. One key difference between Shiki’s group and Zugaikotsu’s is that it focuses on scoring the poem, rather than scoring the contributions of the poet. This gives a slightly different focus, though both are examples of relational creativity. This difference in the structure of the gathering lends a slightly different focus on enskillment. Zugaikotsu’s method puts a focus on individual compositions and how they could be improved, rather than on evaluating the skill of the individual poet. In contrast, we might say that Shiki’s structure had a focus on enskillment. While Shiki’s gatherings evaluated the contributions of the poet, Zugaikotsu’s focus on scoring the poem itself shifts the emphasis toward the improvement of individual compositions rather than the poet’s overall skill. This suggests a contrast between a focus on versification in Zugaikotsu’s gatherings and a focus on individual authorship in Shiki’s, though both are examples of relational creativity.

This haiku gathering, I argue, is a place and setting that challenges stereotypes of what is often called traditional Japanese artistic and creative practice as rigid and hierarchical. Haiku involves a nuanced canon, which is not easily mastered. Through this game, poets care for the canon and the practice of haiku, and in the process, transmit it. It is a social space that plays an integral role in shaping poetic practice. By making the practice of haiku into a lighthearted game to liven up a bar, paradoxically, the haiku group creates a space where more people can compose haiku. While Jimbocho is in many ways hierarchical, governed by rules and manners among a group of professional rivals, such as publishers or bookstore owners, in many other ways, it provides a space where people can meet as equals—or potential equals—stepping outside of professional hierarchies into a space of creativity, learning, and play.

Figure 1: Consulting a saijiki at the bar, photograph by author.

Figure 2: Last minute corrections to the list of poems, photograph by author.

Financial support

This research was supported by the Japan Foundation, The Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies, and the anthropology department at Harvard University.

Competing interests

The author declares no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Funding

The author gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Japan Foundation, the Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard University, and the Department of Anthropology at Harvard University.

Author Biography

Susan Paige Taylor received a PhD in Anthropology from Harvard University. Her research interests include the anthropology of Japan, urban, media, and economic anthropology, book history, digital archives, and human-animal relationships, particularly insects. Her dissertation, “The City of Texts: Affective Work and the Ethics of Care in Booktown Jimbōchō, Tokyo,” is an ethnographic study of the used bookstore neighborhood of Jimbōchō, Tokyo.