Introduction

The traditional progression of clinical evidence starts with pre-clinical studies, which focus on questions such as “could an intervention based on this mechanism work?” and “is there a biological or theoretical plausibility to this intervention?” to phase 1 clinical trials, which focus on whether an intervention is safe, to efficacy and effectiveness trials, which seek to answer “does this intervention work?” Reference Brown, Curran and Palinkas1,Reference Deenik, Czosnek and Teasdale2 Implementation science investigations focus on a different set of questions—how can we ensure that this intervention is delivered effectively in typical care settings? When can this intervention be delivered? In what contexts can this intervention be intergrated? Reference Brown, Curran and Palinkas1–Reference Pinnock, Barwick and Carpenter4 These implementation science questions are fundamental aspects of the day-to-day practice of Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) and Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS).

In contrast to implementation, which focuses on improving uptake of evidence-based practices and on evaluating how, when, and under what conditions these practices can be delivered effectively to improve care, the goal of de-implementation is to promote discontinuation, removal, reduction, or replacement of harmful, ineffective, obsolete, or low-value clinical practices. Reference Norton and Chambers5 While the ultimate intent of implementation and de-implementation science are the same—to improve clinical outcomes—de-implementation science attempts to achieve these goals by promoting practice change in the direction of doing less with a specific intervention, rather than doing more.

Although there is substantial overlap in the factors that determine implementation and de-implementation success, and in some sense the two concepts and the theories and strategies that underpin their programmatic success are different sides of the same coin, there are some features specific to de-implementation that differentiate it and must be taken into consideration when planning and designing the discontinuation or reduced use of an established practice or program. Perhaps most importantly, de-implementation efforts often (but not always) occur after successful implementation has been established and the practice is well integrated, and sometimes quite deeply engrained, into systems and processes. Clinician concerns about medical liability loom much larger over de-implementation than implementation, and care must be taken to ensure that these concerns are addressed in the practice change plan or the de-implementation strategy is unlikely to be successful. Reference Augustsson, Ingvarsson and Nilsen6 Another obstacle to deimplementation efforts is the pervasive action bias in medicine and public health to “do something—” even if the evidence basis for that “something” is limited, or even suggests lack of effectiveness in real-world settings. Reference Halpern, Truog and Miller7 In considering de-implementation initiatives, it is important to remember that human beings generally prefer acts of commission to acts of omission. Reference Halpern, Truog and Miller7 Watchful waiting is inherently hard and antithetical to the culture of medicine and public health (and other, non-health-related industries, as well) and creates challenges specific to de-implementation efforts that are less salient to implementation initiatives. Additional concerns that drive ongoing use of low-value care include concerns about patient wishes and perspectives about their care and discomfort with uncertainty. Reference Eva, van Dulmen, Westert, Hooft, Heus and Kool8

In IPC and particularly AMS, programmatic goals often aim to achieve clinical benefit through practice change in the direction of doing less. Practically, this may include changing practice to reduce the number of tests ordered, encouraging shorter and more narrow courses of antimicrobials, or discontinuation of practices that are no longer considered contextually appropriate, such as adapting masking policies in different settings and as internal and external contexts evolve. Because promoting practice change in the direction of doing less is a critical aspect of day-to-day operations in IPC and AMS, the goals of this Society for Healthcare Epidemiology Research Committee White Paper are to provide a roadmap and framework for leveraging principles of implementation and de-implementation science in day-to-day practice. A companion paper focuses on some practical case studies and examples, including how principles of de-implementation science can be leveraged to promote discontinuation of practices that are ineffective, no longer effective, or usage needs to be reduced. Reference Norton and Chambers5,Reference Branch-Elliman, Dassum and Stroever9

Implementation and de-implementation outcomes

In clinical trials, outcomes used to assess impact, typically at the level of an individual, include efficacy and real-world effectiveness. Aligned with the focus on a different set of questions about interventions and programs (How does this work? When does this work? Why does this work), implementation science has defined a different collection of outcomes to support rigorous evaluations of these questions (Is this feasible? Is this intervention acceptable to those who are being asked to perform it? What are the costs to get this system up and running?). Reference Deenik, Czosnek and Teasdale2,Reference Proctor, Silmere and Raghavan10 These implementation outcomes, which are important for assessing both implementation and de-implementation, are critical determinants of public health policy impact. Even the best intervention will have no impact if no one uses it. Reference Proctor, Silmere and Raghavan10,Reference Branch-Elliman, Elwy and Chambers11

In a very real sense, rather than two distinct entities, de-implementation is a counterpart to, implementation, albeit with a different distribution and weighting of barriers and challenges. A difference between implementation and de-implementation is that implementation initiatives traditionally focus on the early elements of a program or intervention life cycle (Figure 1). Inherently, because the goal of de-implementation is to stop or reduce something that is already being done, de-implementation often focuses far more on the later phases (e.g., sustainment), although there are some cases where early application of de-implementation science principles may be helpful upfront to prevent widespread uptake and dissemination of an ineffective, wasteful or harmful practice. Eventhough most de-implementation efforts focus on engrained practices, early application of principles of de-implementation science- before a practice is deeply engrained in systems- may be easier and more effective than targeting well-established practices.

Figure 1. The implementation and de-implementation life cycle.

Implementation outcomes

Understanding implementation outcomes is crucial for evaluating the success of interventions and policies. Proctor et al define eight foundational implementation outcomes. Reference Proctor, Silmere and Raghavan10 These include the early implementation outcomes of acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, and feasibility; mid-term implementation outcomes of fidelity, penetration, and costs; and the late implementation outcome of sustainability. Conceptually, success in later implementation outcomes is predicated on successful achievement of the earlier implementation outcomes. These outcomes along the causal pathway provide a comprehensive framework for assessing the implementation process, Reference Branch-Elliman, Elwy and Chambers11 helping researchers and practitioners identify barriers and facilitators to successful de-implementation in IPC. Table 1 presents implementation outcomes and along with some specific examples from AMS and IPC.

Table 1. Implementation and de-implementation outcomes and examples in infection prevention and control and antimicrobial stewardship

Acceptability is defined as the perception among interested parties that the intervention is agreeable or satisfactory and aligned with their individual or institutional goals. Adoption is the initial decision or action to recommend the intervention; in other words, the decision to endorse a particular policy. Appropriateness denotes the perceived fit or relevance of the intervention in a particular setting or for a specific target audience; in implementation science, it is distinct but related to acceptability. Feasibility is the extent to which an intervention can be successfully carried out within a given setting or context.

After the decision has been made to adopt a program or intervention, and it has been found to be feasible, acceptable, and appropriate, the next step is to achieve real-world uptake. The mid-term implementation outcomes focus on the degree to which the program or intervention is successfully applied and spread within an institution or organization. Fidelity measures the degree to which an intervention or program is delivered as originally intended by the developers. Fidelity can be viewed as a measure of program or intervention adherence or “quality.” This is imperfectly analogous to the “dose” of the intervention—if a complex, multifaceted intervention is implemented, how many of those different elements is the individual or program “exposed” to? Penetration refers to reach -- how far and how wide the intervention or program travels within a given health system. Is the recommended practice taken up by one clinic? Five? How far does the intervention or program spread throughout the organization? Adopted interventions or programs that achieve high levels of fidelity and those that reach the highest number of people or units are those that are expected to have the most substantial impact on clinical care and public health outcomes.

Costs refer to the financial, resource, and personnel impacts of a program or intervention and include the costs of the implementation effort. Lastly, the late-stage outcome of Sustainability refers to the characteristics of the intervention that support its long-term use within care settings. Sustainment , then, is the outcome of whether the intervention is still being delivered long after the intervention was first implemented. Aligning these concepts with clinical trials and traditional clinical evaluations, sustainment in essence means “longitudinal maintenance of an exposure” whereas sustainability is “durability of the outcome improvements over time,” regardless of how much the program or intervention may have been adopted or changed. Sustainability of clinical benefit is an important goal; however, sustainment is not necessarily always useful or productive. Sustainment of practices that are no longer effective due to temporal changes, innovations that render the intervention no longer necessary or effective, or pathogen evolution do not yield benefit—and therefore should be discontinued, or de-implemented, in favor of other, effective interventions and programs.

De-implementation outcomes

Prusaczyk and colleagues adapted implementation outcomes to reflect tools for measuring de-implementation efforts and their success. Reference Prusaczyk, Swindle and Curran12 These outcomes include shifting the focus to the process of de-implemention or stopping a practice (e.g., feasibility of stopping vs. feasibility of starting) and are generally the inverse of implementation outcome definitions (e.g., instead of feasibility, infeasibility). The authors additionally argue for strong consideration of important determinants of successful de-implementation. Reference Prusaczyk, Swindle and Curran12 These de-implementation-specific determinants include the potential effect of a practice’s cultural or historical significance and patient, consumer, or community reactions to something that may be perceived as being “taken away.” Medical liability concerns and action bias are both relatively stronger barriers to change in de-implementation initiatives than implementation and are additional barriers and determinants to success that need particularly strong consideration in de-implementation initiatives. Reference Augustsson, Ingvarsson and Nilsen6,Reference Branch-Elliman, Gupta and Rani Elwy13–Reference Thorpe, Sirota, Juanchich and Orbell15 Patient preferences and uncertainty are also important factors that hinder de-implementation efforts that need to be considered, particularly when there is the perception that a de-implementation effort may have relatively large impacts on human lives. Reference Eva, van Dulmen, Westert, Hooft, Heus and Kool8,Reference Mukherjee and Reji16,Reference Kemel and Paraschiv17 In addition, Prusaczk et al suggest defining the degree of de-implementation (e.g., complete or partial) and measuring outcomes related to reducing or stopping the specific practice as well as the de-implementation process itself. Adapted definitions for de-implementation, along with some practical examples, are included alongside the implementation outcome definitions in Table 1.

By systematically evaluating these implementation and de-implementation-focused outcomes, interested parties can better understand the causal pathway from intervention to impact, identify potential barriers and facilitators to change, and map those barriers and facilitators to implementation and de-implementation outcomes. It is important to note that these outcomes may be influenced by various factors at different levels, including individual, organizational, and systemic levels, Reference Norton and Chambers5 and can be measured using a range of qualitative and quantitative methods (Figure 2).

Figure 2. De-implementation determinants and process.

Implementation and de-implementation outcomes: Critical determinants of intervention success and health impact

Implementation and de-implementation outcomes have a progressive and temporal relationship, such that early implementation outcomes are determinants of the mid-term outcomes, which in turn influence long-term sustainability and ultimately policy or program impact. Note that de-implementing one thing often means implementing something else such that the two are linked and often need to be considered in concert. For example, in AMS, a variety of tools and interventions are often implemented with the goal of de-implementing inappropriate or unnecessary antimicrobial use. For example, in implementing a new antimicrobial order set with automatic stop times to reduce duration of unnecessary treatment, early outcomes like feasibility (Does the IT-infrastructure exist to support the change? Are there IT-resources available to make the change?) and acceptability (Are providers willing to administer shorter courses of therapy? Will the order set take more time and interrupt workflows?) can influence mid-term outcomes such as fidelity to the intervention (Is the order set used as designed? Are all elements of a bundle ordered or are just a few selected?) and penetration (How many services are using the order set?). Sustainability of the practice change (Degree to which providers reduce unnecessary antimicrobial use) is the ultimate measure of the effectiveness of the intervention (which involved implementing tools to de-implement an unwanted practice), ultimately determining potential positive impacts, such as reduced inpatient stays, reduced antimicrobial-associated adverse events, reduced costs, and reduced antimicrobial resistance.

Implementation frameworks

Many implementation and de-implementation science studies are guided by a large variety of different theories, models, and frameworks.Reference Nilsen 18 In brief, these theoretical approaches fall into three major categories, which are each designed to answer different types of questions. Process models, which “describe and/or guide the process of translating research into practice,” provide the “how to” of implementation and de-implementation.Reference Nilsen 18 Determinant frameworks, which “understand or explain what influences implementation outcomes,” answer questions about the “why and how” implementation and de-implementation works or does not work (and provides insights into which implementation strategies might be helpful for supporting efforts).Reference Nilsen 18 Evaluation frameworks, which are designed to support assessments of the implementation itself, answer the questions “did it work, how well did it work, and why did it work?Reference Nilsen 18 ” A detailed discussion of the theoretical underpinning of implementation and de-implementation science is beyond the scope of this paper. Nilsen’s manuscript, “Making sense of implementation theories, models, and frameworks” provides a detailed view, Reference Nilsen18 and Livorsi et al provide examples and applications specific to AMS and IPC. Reference Livorsi, Drainoni and Reisinger19 The University of Washington Implementation Science Resource Hub also has a useful walkthrough of how to select an implementation science theory or framework to support clinical, operational, and research projects. 20 Livorsi et al include a detailed overview of commonly used frameworks, their potential application to AMS and IPC, and provide guidance on how they can be applied. Reference Livorsi, Drainoni and Reisinger19

Although originally developed to support implementation (“do more”) activities, determinants of implementation often overlap with those of de-implementation (“do less”), and most of these implementation models and frameworks can also be applied to support de-implementation activities with some adaptation. Reference Augustsson, Ingvarsson and Nilsen6 Knowledge-to-Action (KTA) is an example of a process model. Reference Moore21 The KTA model is designed to support both implementation and de-implementation. This process model starts with identification of a gap, followed by adaptation to local context, and assessments of barriers and facilitators to practice change. After these barriers and facilitators are identified, they are mapped to implementation strategies to support practice change. KTA has been used in a variety of settings and contexts, including nursing education and public health interventions, and is amenable for supporting IPC and AMS implementation and de-implementation projects. Reference Livorsi, Drainoni and Reisinger19,Reference White, Daya and Karel22,Reference Field, Booth, Ilott and Gerrish23 The Proctor et al Implementation Outcomes described in the previous section is an example of a determinant framework. Reference Proctor, Silmere and Raghavan10 Additional examples of commonly used determinant frameworks include the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) Reference Damschroder, Aron, Keith, Kirsh, Alexander and Lowery24–Reference Ward, Matheny and Rubenstein29 and the integrated-Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (i-PARIHS) Framework, Reference Harvey and Kitson30 both of which have been applied in IPC and AMS, including to support de-implementation initiatives. Reference Ward, Matheny and Rubenstein29,Reference Branch-Elliman, Lamkin and Shin31 The Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) Framework is a popular version of an evaluation framework, 32 and a variety of tools and toolkits are available to support its application, including an interactive implementation planning tool and checklists. 33

De-implementation frameworks

Although reducing low-value care is a common theme throughout healthcare, and in IPC and AMS in particular, there are limited de-implementation-specific tools and frameworks. De-implementation specific frameworks are less frequently utilized and have a paucity of standardization. Reference Walsh-Bailey, Tsai and Tabak34 A scoping review by Walsh-Bailey et al in 2021 found 23 studies published between 1990 and 2020 in medical or public health literature that detailed frameworks and methods for de-implementation. Reference Walsh-Bailey, Tsai and Tabak34 Nilsen et al reviewed literature between 2013 and 2018 for de-implementation studies aimed at low-value medical care. Reference Nilsen, Ingvarsson, Hasson, von Thiele Schwarz and Augustsson35 Their scoping review found 10 studies that developed or assessed models of de-implementation, five of which re-purposed frameworks of implementation science for de-implementation. Similar to Walsh-Bailey et al, Nilsen and colleagues determined that de-implementation interventions often lack a systematic mechanism for determining de-implementation initiative effectiveness. Reference Walsh-Bailey, Tsai and Tabak34,Reference Nilsen, Ingvarsson, Hasson, von Thiele Schwarz and Augustsson35

Theory and evidence-informed de-implementation

Although de-implementation-specific frameworks are far outnumbered by those that focus on implementation, consistent themes and tools to support successful discontinuation of low-value care have emerged. A major bias in medical culture is the persistent “action bias.” Reference Halpern, Truog and Miller7,Reference Thorpe, Sirota, Juanchich and Orbell15 “Watchful waiting” or the message that “no effective interventions are available” is often not palatable to patients, providers, or the public. This strong bias in favor of errors of commission rather than omission suggests a path forward. Rather than simply aiming for removal of an ineffective practice, the removal can be paired with replacement of the ineffective practice with an alternative (ideally, higher value) intervention. Removal-and-replacement are common underpinnings of de-implementation initiatives. For example, rather than recommending discontinuation of “the culture of culturing,” the practice of ordering a urine culture before surgery in asymptomatic patients can be replaced with a different task, such as “the ABCs of ASB,” which is an educational checklist to promote best practices for management. 36,Reference Gupta and Trautner37 Preliminary findings suggest that this removal-and-replacement strategy (e.g., don’t give antibiotics, do this instead) was associated with a 50% reduction in guideline-discordant antimicrobial use for asymptomatic bacteriuria. Reference Gupta and Trautner37

A parallel and connected theory for supporting de-implementation activities is the behavioral science-based process of learning and unlearning. In this theoretical model, implementation is a one-step process (“learning”) whereas unlearning is a two-step process (learning not to do one thing and learning to do something else instead). It is important to note that under this behavioral model, implementation is always simpler and more straightforward than de-implementation.

In 2017, Helfrich et al proposed extending this theoretical model to support de-implementation in clinical care, hypothesizing that depending upon the specific context or problem, unlearning can be either paired or not paired with an alternative intervention. Reference Helfrich, Rose and Hartmann38 In other words, replacement with an alternative strategy is not needed for all deimplementation efforts. For example, if there is substantial cultural or thought-leader resistance to contact precautions as a standard measure to prevent MRSA, or if the evidence-basis for the practice is questioned, Reference Diekema, Nori, Stevens, Smith, Coffey and Morgan39 de-implementation may occur without offering providers an alternative intervention. However, if providers have strong belief in the effectiveness of contact precautions for protecting themselves or their patients, simple discontinuation of the contact precautions requirement is likely to be ineffective for changing engrained practice. Replacing the contact precautions intervention with other prevention strategies (e.g., learning to do something else more effective), such as education of all healthcare workers and patients, decolonization programs, or improving hand hygiene may be necessary to support unlearning of the ineffective program or intervention. In an ongoing Hybrid III implementation/effectiveness study, Reference Curran, Bauer, Mittman, Pyne and Stetler40 Branch-Elliman et al applied the learning/unlearning theory to design a bundled and multifaceted strategy to promote de-implementation of ineffective post-procedural antimicrobial use; results from this multi-center, mixed methods study are expected to be available in 2025 (NCT05020418). Reference Branch-Elliman, Lamkin and Shin31,Reference Branch-Elliman41 This study is expected to provide some insights about how learning and unlearning theory can be leveraged to support de-implementation activities and advance the science underpinning AMS practice.

The dynamic sustainability framework: De-implementation as an inherent aspect of long-term sustainability and the program and policy lifecycle

A major challenge in infectious diseases, IPC, and AMS is the need for constant adaptation of policies and treatments to adjust to continual change. Unlike many other fields of medical practice, which focus on the host only, infectious diseases management and prevention inherently must accommodate the host-pathogen interaction and pathogen characteristics. As humans develop strategies to combat and treat pathogens, pathogens evolve in response to evade these advancements. For example, reports of antimicrobial resistance occur nearly simultaneous with the introduction of new antibiotics—microbes are inherently nimbler than humans and adapt and evolve much more quickly. And, while we may never be able to keep up with or surpass this ongoing evolution, as a field, we must adapt our plans and interventions to address it.

The constant change and tension between host and pathogen means that IPC and AST programs need a mechanism for ongoing evaluation. Adapting plans inherently means implementing some interventions and de-implementing others. Because fear can be a major driver in IPC responses, particularly for new and emerging threats, an upfront plan for de-escalation, or de-implementation is critical. As noted above, and described in Kahneman’s Prospect theory, humans “regard the status quo as a reference point” and do not like having things taken away from them. Reference Kahneman and Tversky42 Loss aversion is well established in a variety of settings, including medical decision making. Reference Neumann and Böckenholt43,Reference Blumenthal-Barby and Krieger44 Upfront warnings to those impacted that change in the direction of doing less is anticipated with a clearly stated plan including goals and milestones delineating when interventions will be discontinued may mitigate this resistance somewhat, but de-implementation efforts often inherently face strong headwinds.

The constant tension between pathogen evolution and the human response calls for a particularly strong focus on dynamic policy effectiveness in infectious disease, IPC, and AMS, and a need to recognize that plans developed in one setting or context may need to be rapidly changed, or even in some cases completely discarded, as the situation on the ground changes. The Dynamic Sustainability Framework (DSF) is a theoretical and determinant implementation science framework originally introduced by Chambers et al in 2013. Reference Chambers, Feero and Khoury45 As highlighted in the title, the DSF focuses on the issue of sustainability, or maintenance of program effectiveness in the long-term in settings that are expected to change over time. Key concepts highlighted in the DSF include a need to focus on context and a need to adapt programs to ensure maximal effectiveness in different settings and at different times. Aligned with these ideas, the DSF presents programs as puzzle pieces that need to fit into a larger whole—different facilities and different programs will have different puzzle shapes and sizes and correspondingly need different solutions to meet their needs (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The dynamic sustainability framework (adapted from Chambers et al, 2013). Intv = Intervention. Demonstration of need to adapt interventions to fit different settings and contexts. In the setting of ongoing and constant change, ongoing adaptation of the intervention to fit these changes is necessary to maintain ongoing effectiveness and clinical impact.

Specific topics addressed in the DSF include the concept of program drift, or the propensity for program impact to fall off over time as delivery of the program changes, and voltage drop, or the well-described phenomenon of decreasing impact as interventions move from pre-clinical testing to efficacy to effectiveness trials and finally to wider dissemination and implementation. The DSF suggests that program drift and voltage drop can be mitigated through ongoing adaptation and planning to address changes and specific contextual factors. As the interventions themselves, the scientific context and the organizational and the broader healthcare ecosystem evolve over time, adopting the DSF allows the implementers to monitor these changes and adapt continually to ensure achievability of desired outcomes and minimize unintended consequences. Change is inherent to the healthcare system (and the host-pathogen interaction) and achieving maximal benefit requires embracing change and incorporating it into planning. Put another way change—including change in the direction of program discontinuation or de-implementation- is an integral aspect of the sustainability of public health and IPC programs, and a feature of the Learning Health System model. Reference Chambers, Feero and Khoury45,Reference Helfrich46 Rather than a distinct process, de-implementation is an aspect of sustainability.

Implementation strategies: The “interventions” in implementation science

Put simply, “implementation strategies” are the “interventions” of implementation science. More technically, implementation strategies are defined as “methods or techniques that facilitate adoption and sustainment of interventions.” Reference Powell, Fernandez and Williams47 According to Proctor et al, they “constitute the ‘how to’ component of changing healthcare practice.” Reference Proctor, Powell and McMillen48 Implementation and de-implementation use the overlapping implementation strategies to achieve practice change.

A multitude of implementation strategies are available for use. In an effort to standardize definitions and categorize strategies, the Expert Recommendations for Implementation Change (ERIC) Study utilized an expert panel to categorize 73 discrete implementation strategies. Reference Powell, Waltz and Chinman49 Using concept mapping, the ERIC Study grouped each strategy into 9 discrete thematic domains and ranked each strategy’s importance and relative feasibility. Reference Goodrich, Miake-Lye, Braganza, Wawrin and Kilbourne50 There is also a user-friendly, publicly available tool for mapping ERIC implementation strategies to CFIR constructs that can be helpful for identifying useful implementation strategies to support practice change. Reference Waltz, Powell, Fernández, Abadie and Damschroder51–54 Depending upon the specific goal of the implementation or de-implementation, Leeman et al’s five-class approach (dissemination strategies, implementation process strategies, integration strategies, capacity building strategies, and scale-up strategies) is another useful framework for identifying the most promising implementation strategies for a given implementation question. Reference Leeman, Birken, Powell, Rohweder and Shea55

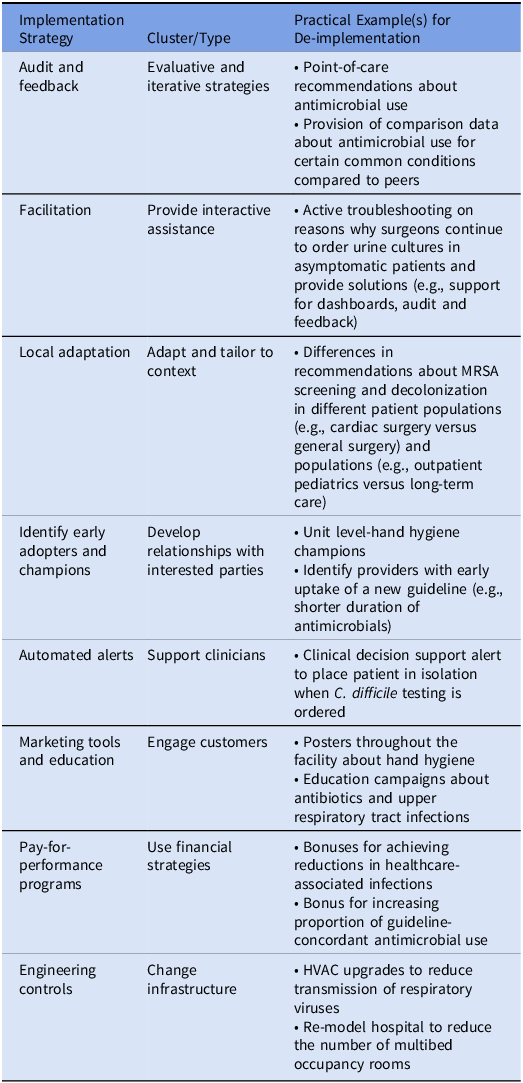

The specifics of the best strategies to achieve the implementation or de-implementation goal will depend upon the program in question. Commonly employed individual implementation and de-implementation strategies within AMS and IPC include provider education, accountable justification, prospective audit and feedback, use of commitment posters, clinical decision support tools, and use of computerized order sets (Table 2). Facilitation and identification of champions are also commonly used to support positive change. For de-implementation specifically, Kien et al found that change infrastructure and workflows, adaptation and tailoring of tools to support the specific context, and forging relationships with interested parties are particularly useful strategies to promote discontinuation of practices that are no longer supported. Reference Kien, Daxenbichler and Titscher56 Anecdotally, we have also found that health communications and public messaging with notification of the public prior to a major de-implementation effort—so that the “baseline” is reset and people are prepared—are also important strategies for promoting change in the direction of doing less. More research is needed to determine how health communications can be optimized to support de-implementation efforts and initiatives.

Table 2. Examples of implementation strategies and practical applications in infection prevention and control and antimicrobial stewardship

Audit and feedback, an implementation (and de-implementation) strategy commonly employed in IPC and AMS, has a varied track record of success for de-implementation of low-value care. Whittington et al highlight that in settings where providers are unaware an intervention is low-value, simple audit and feedback may be sufficient to promote change and reduce unnecessary use. Reference Whittington, Ho and Helfrich57 However, if a provider is already aware an intervention is low-value, additional strategies and interventions are likely to be needed to achieve positive change. If there is an alternative option and a provider is motivated to change, then suggestive audit and feedback can be employed (e.g., give symptomatic relief of lower urinary tract symptoms with phenazopyridine (Pyridium) instead of prescribing ineffective antibiotics). If there is no motivation to change, audit and feedback is unlikely to have a sustained positive impact, although evaluative-type interventions can be attempted. Where concerns about medical liability are a driver of ineffective practices, providing audit and feedback with benchmarking to other providers and demonstrating that the practice is not, in fact, the de-facto standard of care may also be beneficial. Of important note when leveraging audit and feedback as a strategy in AMS efforts: providers are generally motivated to optimize care for the patient in front of them. Discussions about risk of future antimicrobial resistance in future patients who they may never see or care for tend to be ineffective for promoting de-implementation because those impacts have no bearing on the outcome of the patient under their care. Instead, a focus on how an ineffective intervention is negatively impacting the outcome of that individual presently under their care is more likely to be convincing and lead to practice change. Benefits and downsides of different strategies in clinical care applications are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Examples of implementation strategies, determinants of success, and limitations for de-implementation

Implementation and de-implementation strategy bundles: More is (usually) better?

As modeled in the Hierarchy of Intervention Effectiveness, 58 each intervention type has an inherent value in its ability to effectively change behavior, but may achieve greater success when “bundled” with other implementation strategies designed to support and enhance selected interventions. For example, educational interventions often yield low return on investment when employed in isolation. However, when educational campaigns are combined with other strategies, such as audit and feedback, clinical decision support tools, and order sets, practice change is more likely to occur.

Work on a national program to improve rates of hepatitis C treatment demonstrated a positive correlation between the number of implementation strategies included in the bundle at the facility-level and the probability of treatment. Reference Yakovchenko, Lamorte and Chinman52 Although not specifically evaluated in this study, more complex interventions and interventions that are more deeply engrained in medical culture are likely to require more complex and comprehensive bundles to support de-implementation. Reference Norton and Chambers5 Thus, careful consideration of the feasibility and acceptability of the program or intervention proposed for de-implementation is critical for aligning the complexity of the bundled de-implementation plan with the specific low-value practice targeted for discontinuation.

Designing the de-implementation strategy bundle

De-implementation does not always need to be challenging or complicated—practices that are unpopular or not deeply entwined in clinical care pathways may not require a comprehensive de-implementation plan grounded in principles of implementation science and with complex, multifaceted strategies. In fact, de-implementation efforts may be most successful when they are integrated early in the implementation life cycle, before factors that support sustainment are engrained in systems and before a practice becomes regarded as the de-facto status quo and there is the perception that something is being “taken away.” For example, it is easier to stop a practice before a new order set is programed and integrated into the healthcare system—fewer strategies and less comprehensive approaches are needed. Moving the needle on interventions and programs with deep investment is much more challenging and requires substantive effort and planning—and re-evaluation and de-implementation should be considered and integrated upfront as part of a planned program life cycle. Bundled implementation strategies and removal-and-replacement may be particularly effective tools when there is resistance to change in the direction of doing less.

If a more complex de-implementation bundle or plan is needed, several methods exist to assist providers in selecting and/or developing implementation strategies. Reference Powell, Beidas and Lewis59 Formative evaluation includes a pre-intervention determination of site-specific needs, barriers, and facilitators through stakeholder interviewers and in-person observations, followed by development of interventions based on analysis of the collected data by a multidisciplinary team. Implementation mapping provides a structured process to enhance adoption and sustainability of a practice change through a five-step standardized process. Reference Calderwood and Anderson60 First, determinants (e.g., barriers and facilitators) of implementation or de-implementation are identified. Then, the determinants are placed into a matrix (Step 2) and mapped to potential strategies to leverage facilitators or overcome barriers (Step 3). During the fourth step, materials needed to enact the strategies identified during the mapping process (e.g., educational materials are created if knowledge is a barrier). The final step is to monitor and evaluate progress. Other methods for selection of implementation strategies include concept mapping, or first creating a visual depiction of the problem and then identifying and ranking potential strategies to address the problem in terms of key characteristics (e.g., importance and feasibility), group model building, which involves engaging stakeholders to map complex systems and causal loops to identify potential areas for improvement, and conjoint analysis, which involves allowing stakeholders or participants to select the path that they view as highest value. Reference Waltz, Powell, Fernández, Abadie and Damschroder51,Reference Powell, Beidas and Lewis59 In their work on selecting and tailoring implementation strategies, Powell et al detail the pros and cons of each of these different approaches to developing the bundle of strategies. Reference Powell, Beidas and Lewis59 Notably, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research-Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (CFIR-ERIC) assesses contextual determinants across 19 frameworks and can be used to match strategies with identified barriers through an online tool. 54 Using local context to identify barriers and map strategies is an essential step to increase the likelihood of success when de-implementing a practice or process.

Published literature suggests that there is no current single approach that is most effective, as varying de-implementation and implementation strategies may be selected by researchers for each barrier type, however, some general themes have emerged. In their evaluation of barriers and facilitators to de-implementation of low-value interventions, Verkerk et al found that important facilitators of change in the direction of discontinuation included support among the clinician community, knowledge of harms of the intervention, and a consensus that “more is not always better.” Reference Eva, van Dulmen, Westert, Hooft, Heus and Kool8 Uncertainty and concern about undermining the patient’s wishes were important barriers. Aligned with these barriers and facilitators, effective strategies included repeated education (to improve knowledge of harms, improve consensus, and reduce uncertainty), informational feedback interventions (reassurance that harm was not occurring), patient information (to reduce concerns about not meeting patient needs or desires), and organizational challenges were effective strategies for supporting long-term de-implementation efforts. Reference Eva, van Dulmen, Westert, Hooft, Heus and Kool8

The intervention life cycle: From implementation to de-implementation

In implementation, various tools and processes are created to support uptake of the intervention. For example, to support appropriate provision of surgical prophylaxis, a facility may program order sets into the electronic health record (EHR), create and disseminate educational and marketing materials with institutional protocols, and provide audit and feedback to providers about their compliance with the intervention, either in isolation or in comparison to their colleagues. However, when aiming to de-implement an intervention to reduce the duration of post-operative antimicrobials from up to 48 hours after skin closure to immediately after skin closure (in other words, to de-implement old surgical site infection prevention guidelines and replace them with the new ones), Reference Calderwood and Anderson60,Reference Rosenberger, Politano and Sawyer61 all of these tools and processes need to be identified and updated or fully reversed. Identification of existing systematic processes designed to support the intervention being de-implemented and reversing all of them is critical for successful de-implementation.

Simultaneously, these updates also need to be accompanied by a major educational campaign to inform end-users at all levels of the healthcare system not only about the change but the safety of the change (e.g., it is insufficient to merely target surgeons—anesthesiologists, nurses, trainees, and others are also involved in the provision of post-operative services). If education and buy-in are not broad, the de-implementation may be unsuccessful due to ongoing pressure on prescribers from other members of the healthcare team. For example, during qualitative interviews to identify factors associated with prolonged post-procedural prophylaxis following cardiac device implantations, a major theme that emerged was that electrophysiologists who opted to stop antimicrobials early were consistently paged by nursing staff and reminded to write the order prior to patient discharge. Reference Branch-Elliman, Gupta and Rani Elwy13 Prescribers quickly learned that writing the antibiotic prescription was less time-consuming than not writing it and reverted back to the long-engrained but guideline-discordant practice. Recognizing all the stakeholders and drivers contributing to the process is critical for designing an effective de-implementation program and appropriately matching identifying factors supporting continuation of the ineffective practices. Reference Branch-Elliman, Lamkin and Shin31,Reference Branch-Elliman62

Conclusions

IPC and AMS are inherently dynamic. Removal and discontinuation of ineffective practices is an inherent aspect of day-to-day practice—as pathogens change, advancements are made, new evidence emerges and challenges arise, we need to adapt to meet an ever-changing landscape. Implementation science principles can be leveraged to inform the design and practice of clinical programs to improve bedside care—even when less is more.

The aim of programs in IPC, AMS, medicine, and public health is to achieve and sustain optimal health outcomes. How the optimal outcome is achieved can change—and should be the target of both implementation and de-implementation efforts. Viewed through the lens of implementation science, de-implementation can be seen as a critical element for supporting sustainability of improvements through ongoing program evolution and adaptation. Health systems may benefit by viewing interventions as having a defined life cycle, including an upfront plan for ongoing review of utility and effectiveness, with clear standards and processes for discontinuation once an intervention or policy has outlasted its purpose of improving health outcomes.

Financial support

This study was unfunded. WBE is supported by VA HSR IIR 20-076 and VA HSR IIR 20-101.

Competing interests

None.