Introduction

Microbial diversity and function within the deep Earth subsurface remain pivotal in understanding the major biogeochemical activities of our planet. Despite significant research efforts on microbial life that resides beneath the Earth’s surface, the deep biosphere continues to represent one of the “least understood environments till date” (Lopez-Fernandez et al., Reference Lopez-Fernandez, Simone, Wu, Soler, Nilsson, Holmfeldt, Lantz, Bertilsson and Dopson2018; McMahon and Parnell, Reference McMahon and Parnell2014). Although a broad knowledge base on microbial diversity and their patterns of distribution is created through several continental and ocean drilling initiatives covering varied geological settings and ages, a number of fundamental questions on deep life remain poorly resolved. Major questions pertaining to the sustenance of life at greater depths concentrate on two major aspects: (1) who inhabits the deep subterranean environment, and what putative metabolisms support their sustenance in such an aphotic, oligotrophic, multi-extreme habitat, and (2) how do geochemical parameters (i.e. various electron acceptors, electron donors, etc.) influence microbial metabolisms and, thereby, shape the microbial community structure in deep environments (Amils et al., Reference Amils, Escudero, Oggerin, Puente Sánchez, Arce Rodríguez, Fernández Remolar, Rodríguez, García Villadangos, Sanz and Briones2023; Atencio et al., Reference Atencio, Geisler, Rubin-Blum, Bar-Zeev, Adar, Ram and Ronen2023; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Lamminmäki, Alneberg, Andersson, Qian, Xiong, Hettich, Frutschi and Bernier-Latmani2020; Bomberg et al., Reference Bomberg, Lamminmäki and Itävaara2015; Herzig et al., Reference Herzig, Hyötyläinen, Vettese, Law, Vierinen and Bomberg2024; Kadnikov et al., Reference Kadnikov, Mardanov, Beletsky, Karnachuk and Ravin2020; Kieft, Reference Kieft and Hurst2016; Lollar et al., Reference Lollar, Warr, Telling, Osburn and Lollar2019; Momper et al., Reference Momper, Casar and Osburn2023; Osburn et al., Reference Osburn, LaRowe, Momper and Amend2014; Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Bengtsson, Edlund and Eriksson2014; Purkamo et al., Reference Purkamo, Bomberg, Nyyssönen, Kukkonen, Ahonen and Itävaara2015; Simkus et al., Reference Simkus, Slater, Lollar, Wilkie, Kieft, Magnabosco, Lau, Pullin, Hendrickson and Wommack2016)? Deep subterranean habitats are diverse with respect to geochemical parameters and subsequent microbial colonisation; consequently, the answers to the questions are subjected to the habitat specifications (Amils et al., Reference Amils, Escudero, Oggerin, Puente Sánchez, Arce Rodríguez, Fernández Remolar, Rodríguez, García Villadangos, Sanz and Briones2023; Atencio et al., Reference Atencio, Geisler, Rubin-Blum, Bar-Zeev, Adar, Ram and Ronen2023; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Lamminmäki, Alneberg, Andersson, Qian, Xiong, Hettich, Balmer, Frutschi and Sommer2018, Reference Bell, Lamminmäki, Alneberg, Andersson, Qian, Xiong, Hettich, Frutschi and Bernier-Latmani2020; Hernsdorf et al., Reference Hernsdorf, Amano, Miyakawa, Ise, Suzuki, Anantharaman, Probst, Burstein, Thomas and Banfield2017; Ijiri et al., Reference Ijiri, Inagaki, Kubo, Adhikari, Hattori, Hoshino, Imachi, Kawagucci, Morono and Ohtomo2018; Ino et al., Reference Ino, Konno, Kouduka, Hirota, Togo, Fukuda, Komatsu, Tsunogai, Tanabe and Yamamoto2016; Kadnikov et al., Reference Kadnikov, Mardanov, Beletsky, Karnachuk and Ravin2020; Momper et al., Reference Momper, Casar and Osburn2023).

Although different deep biosphere habitats manifest different features, these subterranean environments are typically characterised by oligotrophy, absence of sunlight and photosynthetically derived organic matter, where chemolithoautotrophic organisms are thought to be the primary producers (Pedersen, Reference Pedersen2000). Previous studies suggest that geogenic and/or biogenic hydrogen (H2) facilitates microbial metabolism within these energy-starved subsurface environments (Amils et al., Reference Amils, Escudero, Oggerin, Puente Sánchez, Arce Rodríguez, Fernández Remolar, Rodríguez, García Villadangos, Sanz and Briones2023; Hernsdorf et al., Reference Hernsdorf, Amano, Miyakawa, Ise, Suzuki, Anantharaman, Probst, Burstein, Thomas and Banfield2017; Ijiri et al., Reference Ijiri, Inagaki, Kubo, Adhikari, Hattori, Hoshino, Imachi, Kawagucci, Morono and Ohtomo2018; Nealson et al., Reference Nealson, Inagaki and Takai2005; Nyyssönen et al., Reference Nyyssönen, Hultman, Ahonen, Kukkonen, Paulin, Laine, Itävaara and Auvinen2014; Stevens, Reference Stevens1997; Stevens and McKinley, Reference Stevens and McKinley2000). Under the natural conditions that prevailed in the deep Earth crust, geogenic hydrogen may be produced through serpentinisation, radiolysis of water, degassing of magma-hosted systems, etc. or biologically via fermentation, anaerobic methane oxidation, etc. (Beaver and Neufeld, Reference Beaver and Neufeld2024; Gregory et al., Reference Gregory, Barnett, Field and Milodowski2019; Nealson et al., Reference Nealson, Inagaki and Takai2005). Along with hydrogen metabolism, the interplay of dynamic carbon, nitrogen and sulfur cycles with the involvement of diverse microbial groups make the overall system a complex paradigm (Hernsdorf et al., Reference Hernsdorf, Amano, Miyakawa, Ise, Suzuki, Anantharaman, Probst, Burstein, Thomas and Banfield2017; Momper et al., Reference Momper, Casar and Osburn2023). Complex processes such as autotrophic carbon fixation with hydrogen/sulfur oxidation (as a source of electrons/energy) coupled with nitrate reduction are reported to be one of the putative metabolisms plausible in anoxic deep biosphere (Lau et al., Reference Lau, Kieft, Kuloyo, Linage-Alvarez, Van Heerden, Lindsay, Magnabosco, Wang, Wiggins and Guo2016). Oxidation of methane and other reduced inorganic molecules, such as ammonia and nitrite, and reduction of sulfate or iron (Fe3+) or manganese (Mn4+) as terminal electron acceptors while assimilating carbon via auto/hetero/mixotrophic processes are also frequently observed in these environments (Casar et al., Reference Casar, Momper, Kruger and Osburn2021; Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Dutta Gupta, Gupta, Sarkar, Roy, Mukherjee and Sar2018; Momper et al., Reference Momper, Jungbluth, Lee and Amend2017; Purkamo et al., Reference Purkamo, Bomberg, Nyyssönen, Kukkonen, Ahonen, Kietäväinen and Itävaara2013; Vaccarelli et al., Reference Vaccarelli, Matteucci, Pellegrini, Bellatreccia and Del Gallo2021). Interestingly, heterotrophy, fuelled by the metabolic intermediates or products of chemolithoautotrophic metabolism, is also detected in many such environments (Purkamo et al., Reference Purkamo, Bomberg, Nyyssönen, Kukkonen, Ahonen and Itävaara2015; Sahu et al., Reference Sahu, Kazy, Bose, Mandal, Dutta, Saha, Roy, Dutta Gupta, Mukherjee and Sar2022). Deciphering the biogeochemical processes constituted by the complex networks of metabolic transformation by the resident microbial members of any particular deep subsurface environment is identified as one of the major approaches for understanding the different modes of sustenance of life, such as the energetic edge (Ino et al., Reference Ino, Konno, Kouduka, Hirota, Togo, Fukuda, Komatsu, Tsunogai, Tanabe and Yamamoto2016; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Holmfeldt, Hubalek, Lundin, Åström, Bertilsson and Dopson2016a).

A number of deep biosphere studies are conducted in the subterranean water systems across the continents (Hallbeck and Pedersen, Reference Hallbeck and Pedersen2008; Herzig et al., Reference Herzig, Hyötyläinen, Vettese, Law, Vierinen and Bomberg2024; Itävaara et al., Reference Itävaara, Nyyssönen, Kapanen, Nousiainen, Ahonen and Kukkonen2011; Momper et al., Reference Momper, Jungbluth, Lee and Amend2017; Nyyssönen et al., Reference Nyyssönen, Hultman, Ahonen, Kukkonen, Paulin, Laine, Itävaara and Auvinen2014; Purkamo et al., Reference Purkamo, Bomberg, Kietäväinen, Salavirta, Nyyssönen, Nuppunen-Puputti, Ahonen, Kukkonen and Itävaara2016; Sahl et al., Reference Sahl, Schmidt, Swanner, Mandernack, Templeton, Kieft, Smith, Sanford and Callaghan2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Holmfeldt, Hubalek, Lundin, Åström, Bertilsson and Dopson2016a). One of the first studies that gave an overview of microbial diversity as well as its function from a genomic point of view was conducted in deep crystalline rock environments of the Fennoscandian shield (Nyyssönen et al., Reference Nyyssönen, Hultman, Ahonen, Kukkonen, Paulin, Laine, Itävaara and Auvinen2014). Taxonomically and functionally diverse populations are observed among different deep subsurface horizons of the Fennoscandian shield, which vary in response to the prevailing lithology and hydrochemistry. Subsequent studies within other deep crystalline rock and groundwater environments gave an extensive overview of the microbial processes that govern the terrestrial subsurface environments (Amils et al., Reference Amils, Escudero, Oggerin, Puente Sánchez, Arce Rodríguez, Fernández Remolar, Rodríguez, García Villadangos, Sanz and Briones2023; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Lamminmäki, Alneberg, Andersson, Qian, Xiong, Hettich, Frutschi and Bernier-Latmani2020; Momper et al., Reference Momper, Jungbluth, Lee and Amend2017; Probst et al., Reference Probst, Ladd, Jarett, Geller-Mcgrath, Sieber, Emerson, Anantharaman, Thomas, Malmstrom and Stieglmeier2018; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Holmfeldt, Hubalek, Lundin, Åström, Bertilsson and Dopson2016a). Many of these studies employed genome reconstruction from metagenomes to get better insights into individual genomes of microbes in a microbial community of deep terrestrial subsurface (Atencio et al., Reference Atencio, Geisler, Rubin-Blum, Bar-Zeev, Adar, Ram and Ronen2023; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Lamminmäki, Alneberg, Andersson, Qian, Xiong, Hettich, Balmer, Frutschi and Sommer2018, Reference Bell, Lamminmäki, Alneberg, Andersson, Qian, Xiong, Hettich, Frutschi and Bernier-Latmani2020; Coskun et al., Reference Coskun, Gomez-Saez, Beren, Doğacan, Günay, Elkin, Hoşgörmez, Einsiedl, Eisenreich and Orsi2024; Hernsdorf et al., Reference Hernsdorf, Amano, Miyakawa, Ise, Suzuki, Anantharaman, Probst, Burstein, Thomas and Banfield2017; Kadnikov et al., Reference Kadnikov, Mardanov, Beletsky, Karnachuk and Ravin2020; Momper et al., Reference Momper, Casar and Osburn2023; Thieringer et al., Reference Thieringer, Boyd, Templeton and Spear2023). Although past research has provided important information on microbial communities inhabiting various continental subsurface environments, the progressively hot and seismically active igneous province of deep continental biosphere within Deccan Traps is comparatively underexplored. Albeit limited, studies initiated by our laboratory (Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Dutta Gupta, Gupta, Sarkar, Roy, Mukherjee and Sar2018, Reference Dutta, Peoples, Gupta, Bartlett and Sar2019a,Reference Dutta, Sar, Sarkar, Dutta Gupta, Gupta, Bose, Mukherjee and Royb) have provided some insights into the endolithic microbial life and their genomic potential. Nevertheless, the nature and function of deep biosphere within the aquifers hosted by the Deccan Traps, and comparison of such microbial life to the rock-hosted one remains uncharacterised, unlike other subsurface environments.

The volcanic province of the deep subsurface of the Deccan Traps is considered to be an unusual extreme environment for life with progressive increase in temperature and lithostatic pressure (at a rate of ~15°C/km and ~26 MPa/km, respectively), low organic carbon (<50 mg TOC/kg) and the presence of multiple heavy metals (Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Dutta Gupta, Gupta, Sarkar, Roy, Mukherjee and Sar2018; Goswami et al., Reference Goswami, Akkiraju and Roy2024; Roy and Rao, Reference Roy and Rao2000; Shukla et al., Reference Shukla, Vishnu and Roy2022). In the present study, microorganisms inhabiting the aquifers deep-seated within the one of the largest continental flood basalt, i.e. the Deccan Traps, and their interaction with surrounding rock matrix is investigated through a combination of geochemistry, metataxonomics, and metagenomics followed by genome reconstruction techniques. Aquifer-inhabiting planktonic and rock-inhabiting endolithic microorganisms have been investigated to identify the core microorganisms. The knowledge base developed through this study can be used for gathering further information on global subsurface microbial abundance, diversity, and metabolism.

The Deccan Traps in western India (also known as Deccan Volcanic Province) represent one of the largest continental flood-basalt provinces, with an approximate area of >0.5 million km2 and a total thickness of >2 km near the eruptive centre (Bhaskar Rao et al., Reference Bhaskar Rao, Sreenivas, Vijaya Kumar, Khadke, Kesava Krishna and Babu2017; Schoene et al., Reference Schoene, Samperton, Eddy, Keller, Adatte, Bowring, Khadri and Gertsch2015). The ~65-million-year-old Deccan basalts are underlain directly by granitic basement rocks of Precambrian age (~2700 Ma) with a thin intermediate, weathered zone. Apart from its geological importance, this volcanic province has gained considerable scientific attention owing to the well-known Reservoir Triggered Seismicity within the Koyna Seismogenic Zone (KSZ) (Roy, Reference Roy2017). The KSZ has experienced recurrent seismic activity during the past five and half decades, starting soon after the impoundment of the Shivajisagar (Koyna) water reservoir on the Koyna River in 1962 (Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Purnachandra Rao, Roy, Arora, Tiwari, Patro, Satyanarayana, Shashidhar, Mallika and Akkiraju2015). Geological mapping combined with geophysical and geochemical studies carried out in the past provide crucial information about the subsurface fault-fracture systems in this seismogenic zone (Goswami et al., Reference Goswami, Roy and Akkiraju2019, Reference Goswami, Hazarika and Roy2020, Reference Goswami, Akkiraju and Roy2024). However, the characteristics of microbial life that exist in the deep biosphere of this igneous province remain unexplored, mostly due to difficulty in accessing the deep subsurface samples. Recent scientific drilling (up to several kilometres below the surface) enabled geomicrobiologists to explore deep life hosted by the igneous crust using the rock cores recovered. These studies conducted on the basaltic and granitic rocks provided evidence of bacterial and archaeal life within this extreme realm, including the characterisation of piezophilic bacteria and various chemolithotrophic bacterial populations thriving in the deep biosphere (Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Dutta Gupta, Gupta, Sarkar, Roy, Mukherjee and Sar2018, Reference Dutta, Peoples, Gupta, Bartlett and Sar2019a,Reference Dutta, Sar, Sarkar, Dutta Gupta, Gupta, Bose, Mukherjee and Royb; Mandal et al., Reference Mandal, Bose, Ramesh, Sahu, Saha, Sar and Kazy2022; Saha et al., Reference Saha, Sahu, Sar and Kazy2024; Sahu et al., Reference Sahu, Kazy, Bose, Mandal, Dutta, Saha, Roy, Dutta Gupta, Mukherjee and Sar2022). In comparison with these, microbial life within the deep groundwater of this igneous province remained uncharted until the aquifer samples were available for geomicrobiological analysis post establishment of the deep boreholes. The present study was therefore conducted to investigate the microbial community structure and function of the groundwater systems of Deccan Traps, identify the local geochemical factors that probably control the microbial communities and ascertain if the groundwater system represents a distinct ecological niche as compared to the surface water system of this igneous province. Overall, the study aims to provide a better understanding of the nature and function of deep microbial life as guided by the physicochemical factors of the Deccan Traps.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Water samples were collected from three groundwater sources (bore wells), one natural spring and two surface water sources (Koyna River and Koyna Reservoir) of the Koyna-Warna region (Fig. S1; Table 1). The sites used for water sampling were: (1) the Koyna pilot borehole KFD1 in Gothane, drilled at the centre of a 2 × 2 km seismic cluster in the northcentral part of the Koyna seismogenic zone, near the Donichawadi fault (sample obtained from a depth of 1027 m, referred to as DBW in this manuscript); (2) a tube well adjacent to the borehole KBH-5 in Phansavale, located in the vicinity of a seismic cluster in the southwestern fringes of the Koyna seismogenic zone, adjoining the western face of the Western Ghats escarpment (depth 100 m, referred to as BW in this manuscript); and (3) a groundwater well near Karad, about 40 km to the east of the Koyna seismogenic zone (depth 100 m, referred to as BGRL in this manuscript). For groundwater sampling, water from each of the wells was flushed out via continuous pumping (for 15–30 min) until the dissolved oxygen level reached a steady state (as monitored by a Thermo Orion multi-parameter probe). The spring water (referred to as PBW in this manuscript) was sampled from the water tank which received the slow-flowing water from the spring. For the surface water, multiple subsamples were collected from the Koyna River (referred to as KR in this manuscript) and Koyna Reservoir (referred to as KD in this manuscript). From each site, 2–4 L of water was collected in sterile containers and stored at 4°C for shipment. The samples were stored at 4°C in the laboratory until further analysis.

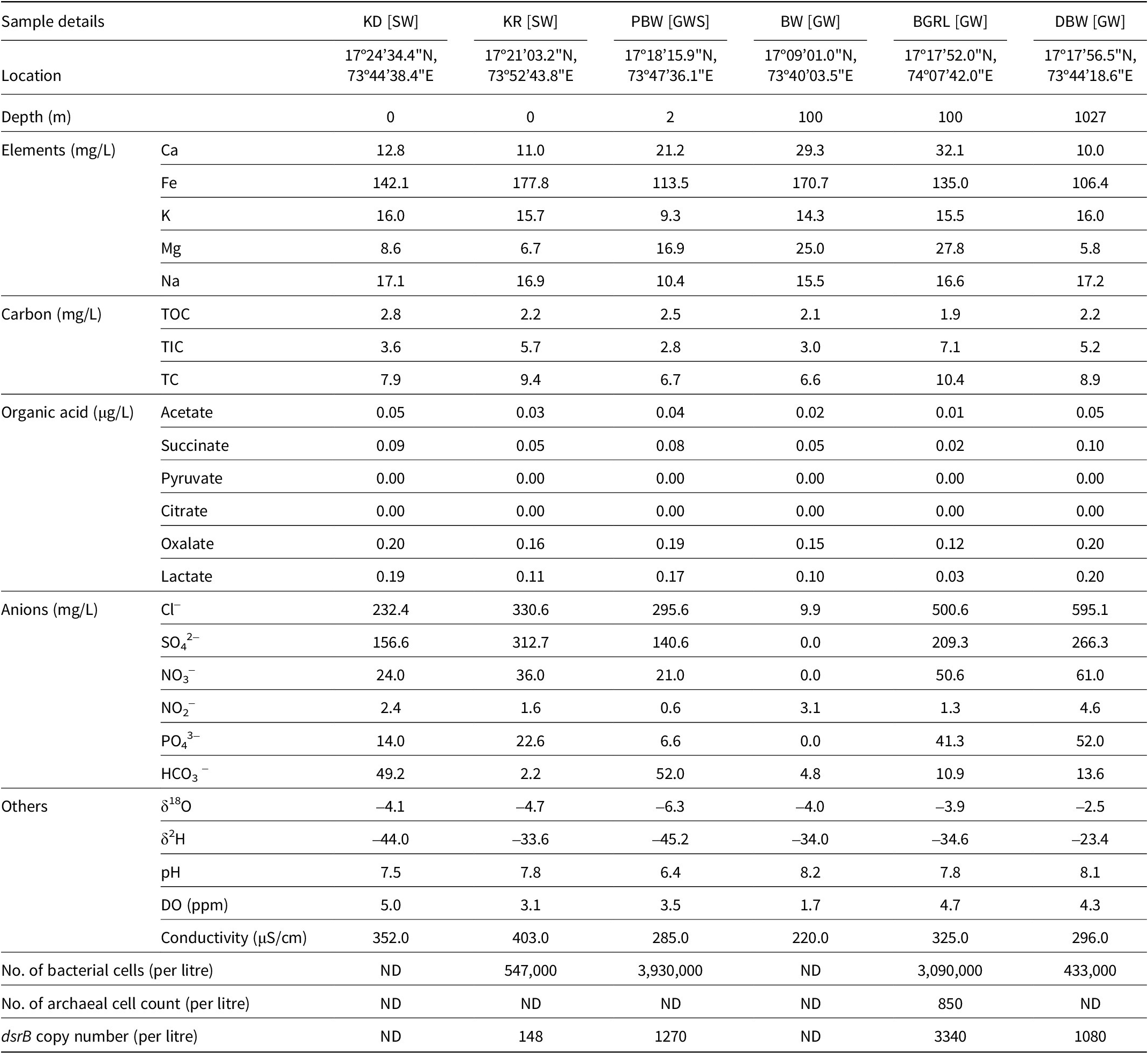

Table 1. Hydrochemical characteristics of the water samples. “ND” denotes “not detected”. GW, groundwater; GWS, groundwater seepage; SW, surface water

Hydrochemical analysis

Measurement of major elements was conducted using Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) (iCAP Q, Thermo Scientific). Cavity ring-down spectroscopy (L2130i Picarro) was used to measure stable isotopes of oxygen (δ18O) and hydrogen (δ2H). Major anions (Cl–, NO2–, SO42–, NO3–, Br– and PO43–) were measured using a Dionex ICS 2100 (Thermo Scientific). Total organic carbon (TOC), total inorganic carbon (TIC), and total carbon (TC) were measured using an OI analytical TOC analyser. The alkalinity of the water samples was measured using U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) method 310.2. Measurement of pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), and conductivity was done using highly sensitive probes (Orion) fitted with an Orion multimeter (Thermoelectron Corporation). For measurements of organic acids, a 20 μL sample was injected into the Ultimate High-Performance Liquid Chromatograph (Dionex® 3000 U-HPLC, Thermo Fisher Scientific). A C18 reverse-phase analytical column was used with a mobile phase of a binary mixture of solvents: (1) water (30%) and (2) acetonitrile (70%). The separation was performed at room temperature, and the flow rate was maintained at 1 mL/min. The compounds were monitored at wavelengths of 254, 265, 286 and 295 nm. The calibration curves consisted of five standard solutions ranging from 0.1 to 50 mg L–1. Chromeleon 6.8 software was used for data acquisition and integration.

Extraction of DNA

For each sample, 1000 mL of water was filtered using a sterile 0.22 μm filter, and total DNA was extracted from the filters using a Metagenomic DNA Isolation kit (Epicentre) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality of the extracted DNA and its concentration were measured using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer, followed by fluorometric quantitation using Qubit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Quantification of the copy number of the structural (bacterial and archaeal specific 16S rRNA gene) and functional (dsrB) genes has been done through quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) following the methods reported by Dutta et al. (Reference Dutta, Dutta Gupta, Gupta, Sarkar, Roy, Mukherjee and Sar2018). Details of the qPCR primers used are provided in Table S1. All the reactions were set in triplicate. Bacterial 16S rRNA gene copy numbers were determined in each sample by comparing the amplification result to a standard dilution series ranging from 102 to 1010 of plasmid DNA containing the 16S rRNA gene of Achromobacter sp. MTCC 12117. Genes encoding archaeal 16S rRNA and dsrB were PCR amplified from the metagenome, cloned into a TA cloning vector, and plasmid DNAs for each gene targets with copy numbers 102 to 1010 were used as standards for quantitation purposes. Quantitative PCR has been performed in Quant Studio 5 with Power SYBR green PCR master-mix (Invitrogen), with a primer concentration of 5 pM. Melting curve analysis was run after each assay to check PCR specificity.

16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing

Following the quality check, extracted DNA were subjected to amplification of the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene using primers 515F/806R (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Berg-Lyons, Caporaso, Walters, Knight and Fierer2011) (Table S2). On purification of the PCR products, further sequencing was done on the Ion S5 platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Refer to Table S2 for a detailed procedure. The sequenced reads were submitted to the short read archive under BioProject ID PRJNA445925.

Amplicon data analysis and contamination removal

Raw data obtained from Ion S5 were analysed through the QIIME 2 amplicon-2024.10 (Bolyen et al., Reference Bolyen, Rideout, Dillon, Bokulich, Abnet, Al-Ghalith, Alexander, Alm, Arumugam and Asnicar2019) bioinformatics pipeline. Default parameters were used with each module, unless specified otherwise. Along with the reads from the samples, a reagent control (SRA Accession: SRR35284829) was also included in the amplicon data analysis. This control sample was created by subjecting nuclease-free water to the same DNA extraction and amplicon sequencing procedure as the samples. All datasets were quality filtered, clustered, denoised and chimera filtered using DADA2 with the parameters “denoise-single --p-trunc-len 270 --p-trim-left 30 --p-pooling-method pseudo --p-min-fold-parent-over-abundance 2” (Callahan et al., Reference Callahan, McMurdie, Rosen, Han, Johnson and Holmes2016). The ASVs obtained were assigned taxonomy using the “feature-classifier classify-sklearn” module with the naive Bayes classifier “GG-2024.09.backbone.v4.nb.sklearn-1.4.2” pre-trained on Greengenes2 2024.09 (which is in turn is based on GTDB r220) (Bokulich et al., Reference Bokulich, Kaehler, Rideout, Dillon, Bolyen, Knight, Huttley and Caporaso2018; McDonald et al., Reference McDonald, Jiang, Balaban, Cantrell, Zhu, Gonzalez, Morton, Nicolaou, Parks and Karst2024; Pedregosa et al., Reference Pedregosa, Varoquaux, Gramfort, Michel, Thirion, Grisel, Blondel, Prettenhofer, Weiss and Dubourg2011). Based on recommendations by Sheik et al. (Reference Sheik, Reese, Twing, Sylvan, Grim, Schrenk, Sogin and Colwell2018) and techniques used by Purkamo et al. (Reference Purkamo, Kietäväinen, Nuppunen-Puputti, Bomberg and Cousins2020), contamination removal was performed by removing all ASVs unassigned to domains and those affiliated to Eukarya, mitochondria, chloroplast, Streptococcaceae, Propionibacteriaceae, Lactobacillaceae, Escherichia-Shigella and Staphylococcaceae. The reagent control was used to run “quality-control” modules with “decontam-identify” and “decontam-remove” parameters (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Proctor, Holmes, Relman and Callahan2018). Finally, singletons (ASVs with a total of only one read across samples) were removed as suspected contaminants, and the retained ASVs were used for determining relative abundance and core ASVs. Diversity parameters were determined by rarifying all samples to 180,000 reads and then using the “diversity alpha” module.

Statistical analysis and phylogenetic tree construction

The relative abundance of core ASVs of the groundwater samples (BGRL, BW, DBW) was determined at the genus level and used to calculate Spearman’s rs correlation with the geochemical characteristics of the respective samples. Euclidean distances between the correlations were used to plot the Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic mean (UPGMA) dendrogram. These statistical analyses were performed with PAST v4.12b (Hammer et al., Reference Hammer, Harper and Ryan2001). Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) based on the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity was conducted for the microbial communities at the family level. Families having greater than 1% average abundance across all the samples were considered for this analysis. The function envfit was used to fit environmental vectors to the ordination plot using the vegan package (Oksanen et al., Reference Oksanen, Simpson, Blanchet, Kindt, Legendre, Minchin, O’Hara, Solymos, Stevens and Szoecs2025) in R. NMDS analysis of microbial community structure was conducted using R and R Studio. Ten of the ASVs with the highest relative abundance (>2% on average) in groundwater samples were subjected to phylogenetic analysis. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) databases were queried with the blastn suite to find the closest matches for these ASVs from extreme environments. The ASVs were grouped by their order and aligned with ClustalX2 (Larkin et al., Reference Larkin, Blackshields, Brown, Chenna, McGettigan, McWilliam, Valentin, Wallace, Wilm and Lopez2007). A neighbour-joining tree was created from the alignment using MEGA 11, with the bootstrap method (n = 1000), Jukes–Cantor substitution model, gamma distribution (G = 1.00) rates among sites and pairwise deletion treatment (Tamura et al., Reference Tamura, Stecher and Kumar2021). The phylogenetic tree was visualised with the ggtree v3.12.0 R package (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Li, Luo, Chen, Tang, Zhan, Dai, Lam, Guan and Yu2022).

Whole metagenome sequencing and analysis

Metagenomes of three water samples (two groundwater samples and one surface water sample) were considered for whole metagenome sequencing. Following metagenomic extraction, DNA was enzymatically digested and size selection was made using the E-Gel electrophoresis system (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific). After size selection, DNA was ligated with Ion Xpress barcode adapters and pooled together for emulsion PCR using the Ion OneTouch™ 2 System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The PCR product was sequenced using the Ion S5 platform. Quality checking of the trimmed paired-end reads was conducted using FastQC (version 0.11.7). Trimmed sequences were assembled using SPAdes assembler (Bankevich et al., Reference Bankevich, Nurk, Antipov, Gurevich, Dvorkin, Kulikov, Lesin, Nikolenko, Pham and Prjibelski2012) using default parameters. Quast 4.3 was used for evaluations of metagenomic assemblies and different assembly statistics (Gurevich et al., Reference Gurevich, Saveliev, Vyahhi and Tesler2013). Best k-mer was selected on the basis of longest contigs and N50 value for different samples and was annotated using the Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) v.6 (Mukherjee et al., Reference Mukherjee, Stamatis, Bertsch, Ovchinnikova, Verezemska, Isbandi, Thomas, Ali, Sharma and Kyrpides2017). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)-based annotation was selected for further analysis. The annotated data are available under IMG GOLD Analysis Project IDs Ga0247434 (PBW), Ga0247435 (DBW), and Ga0247436 (BGRL). Heatmaps were created to compare metagenomic inventories of rock and water samples with respect to carbon, sulfur, and nitrogen cycles using the pheatmap package in R (Kolde and Kolde, Reference Kolde and Kolde2015). The annotated data for rocks were based on the analysis reported by Dutta et al. (Reference Dutta, Dutta Gupta, Gupta, Sarkar, Roy, Mukherjee and Sar2018).

For reconstructing metagenome-assembled genomes, the single-end metagenome sequencing raw reads obtained were reverse complemented in silico with seqtk-v1.4 (r122) (H. Li, Reference Li2016). Read quality filtering, human contamination removal, assembly, binning, bin refinement and reassembly were performed with the MetaWRAP v1.3.2 pipeline and the tools therein using default settings unless specified otherwise (Uritskiy et al., Reference Uritskiy, DiRuggiero and Taylor2018). Filtered reads were concatenated for co-assembly with MEGAHIT v1.2.9 (D. Li et al., Reference Li, Liu, Luo, Sadakane and Lam2015). Binning was performed in single-end, “universal” (bacteria and archaea) mode using MetaBAT 2 v2.12.1, MaxBin 2.0 v2.2.7, and CONCOCT v1.1.0 (Alneberg et al., Reference Alneberg, Bjarnason, De Bruijn, Schirmer, Quick, Ijaz, Lahti, Loman, Andersson and Quince2014; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Li, Kirton, Thomas, Egan, An and Wang2019; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Simmons and Singer2016b). Bin refinement was performed using MetaWRAP’s bin_refinement module with a minimum completion threshold of 50% and maximum contamination of 10%. The resulting bins were used to determine relative abundance in terms of genome copies per million filtered reads using the quant_bins module, and then refined bins were reassembled using identical thresholds. The samples were clustered via the UPGMA (Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic mean) algorithm using the Bray–Curtis similarity index and a bootstrap of 1000, with the help of PAST v4.12b (Bray and Curtis, Reference Bray and Curtis1957; Hammer et al., Reference Hammer, Harper and Ryan2001). Completeness of the bins based on the presence of lineage-specific marker genes was calculated using CheckM v1.0.18, and quality was inferred based on standards delineated by Bowers et al. (Reference Bowers, Kyrpides, Stepanauskas, Harmon-Smith, Doud, Reddy, Schulz, Jarett, Rivers and Eloe-Fadrosh2017; Parks et al., Reference Parks, Imelfort, Skennerton, Hugenholtz and Tyson2015). Taxonomy assignment was performed using GTDB-Tk v2.4.0 (database r220) (Chaumeil et al., Reference Chaumeil, Mussig, Hugenholtz and Parks2020). Functional annotation was performed in metagenome mode using the eggNOG-mapper v2.1.12 with eggNOG DB v5.0.2, employing Prodigal v2.6.3 for gene prediction while searching via MMseqs2 v15.6f452, with default settings (Cantalapiedra et al., Reference Cantalapiedra, Hern̗andez-Plaza, Letunic, Bork and Huerta-Cepas2021; Huerta-Cepas et al., Reference Huerta-Cepas, Szklarczyk, Heller, Hernández-Plaza, Forslund, Cook, Mende, Letunic, Rattei and Jensen2019; Hyatt et al., Reference Hyatt, Chen, LoCascio, Land, Larimer and Hauser2010; Steinegger and Söding, Reference Steinegger and Söding2017). DRAM 1.4.0 was used for functional annotation of Metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), assessment of pathway completeness, and categorising different microbial metabolisms (Shaffer et al., Reference Shaffer, Borton, McGivern, Zayed, La Rosa, Solden, Liu, Narrowe, Rodríguez-Ramos and Bolduc2020).

Results

Hydrochemical characteristics of water samples

The hydrochemical characteristics of the water samples were analysed to ascertain the local physicochemical conditions available to the inhabiting microbial communities (Table 1). Groundwater samples were found to be slightly alkaline in nature (pH 7.8–8.2), having low dissolved oxygen (1.7–4.7 mg L–1) and organic carbon (1.9–2.2 mg L–1). The inorganic carbon content of these samples, however, was relatively higher (3.0–7.1 mg L–1), particularly compared to their surface water counterpart. Diverse concentrations of the anions (Cl– 9.9–595.1 mg L–1, NO2– 0.6–4.6 mg L–1, NO3 – 0–61 mg L–1 and PO43– 0–52 mg L–1) and elements (Ca 10–32.1 mg L–1, Fe 106.4–177.8 mg L–1, Mg 5.8–27.8 mg L–1, K 9.3–16.0 mg L–1 and Na 10.4–17.2 mg L–1) were detected. An overall greater concentration of anions and elements was detected in groundwater samples than in surface water. However, the concentration of Fe was found to be higher in surface water. Among the groundwater samples, DBW showed relatively higher concentrations of Cl–, SO42–, and NO3–. The values of δ18O and δ2H in the samples showed variation but indicated their meteoric origin (Das et al., Reference Das, Debnath, Duttagupta, Sarkar, Agrahari and Mukherjee2020; Hosono et al., Reference Hosono, Yamada, Manga, Wang and Tanimizu2020). The DBW sample showed the lowest values of δ18O and δ2H. Non-metric multidimensional scaling based on the geochemical characteristics of the samples showed distinct patterns of the partitioning of groundwater and surface water samples (Fig. S2). It was highlighted that the groundwater ecosystems of the Deccan Traps were mainly constrained by pH, total organic carbon (TOC), TIC, Mg, Ca, NO3–, Fe and SO42–. Among the organic acids tested, oxalic and lactic acids were detected at relatively higher concentrations (oxalic acid 0.12–0.20 mg L–1 and lactic acid 0.03–0.20 mg L–1), followed by acetic acid (0.01–0.05 mg L–1) and succinic acid (0.02–0.10 mg L–1). Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on major hydrochemical parameters, along with organic acids detected in the samples, also showed the distinctive nature of groundwater compared to its surface water counterpart (Fig. S3).

Quantitative estimation of microbial cells and dissimilatory sulfite reductase gene

Quantitative PCR-based estimation of bacterial 16S rRNA and dsrB genes was possible in all but two samples (KD and BW). The estimated bacterial cell counts, as obtained through qPCR, showed 4.3 × 102–3.9 × 103 cells mL–1 (Table 1) (assuming an average of 4.2 16S rRNA gene copies/genome of bacteria; Stoddard et al., Reference Stoddard, Smith, Hein, Roller and Schmidt2015). The archaeal 16S rRNA gene was detected only in the BGRL, showing a presence of around 8.5 × 102 cells L–1. Gene fragments of the dsrB gene were detected in the same four samples whose bacterial 16S rRNA gene copy number was estimated. Deep subsurface water samples (BGRL and DBW) yielded 1.08 × 103–3.34 × 103 copies L–1, while the surface water sample KR showed a lower abundance of dsrB (1.48 × 102 copies L–1).

16S rRNA gene sequence data and alpha diversity analysis

After quality filtering, totals of 939,455 and 691,998 reads were obtained from the groundwater and surface water samples, respectively. These quality-filtered reads were grouped into 2020 and 1596 ASVs for groundwater and surface water, respectively (Table S3). The average numbers of filtered reads and ASVs obtained per groundwater sample were 313,152 and 705, respectively, while 345,999 reads and 847 ASVs were obtained for surface water samples on average. Among the groundwater samples, the highest number of ASVs was obtained for BGRL (1466 ASVs). Most of the ASVs were affiliated to bacteria (>98.86% for all samples) and a small fraction (<1.14 % for all samples) was affiliated to archaea. The Shannon and the Simpson indices indicated that microbial communities of the groundwater were relatively less diverse and uneven compared to their surface water counterparts. Interestingly, only 16 of 2020 ASVs were shared among the three samples (Table S3). These shared ASVs, representing the core community of the groundwater, covered 4.69–36.95%, with the highest in the sample from the deepest sample (DBW, 1027 mbs).

Microbial community analysis

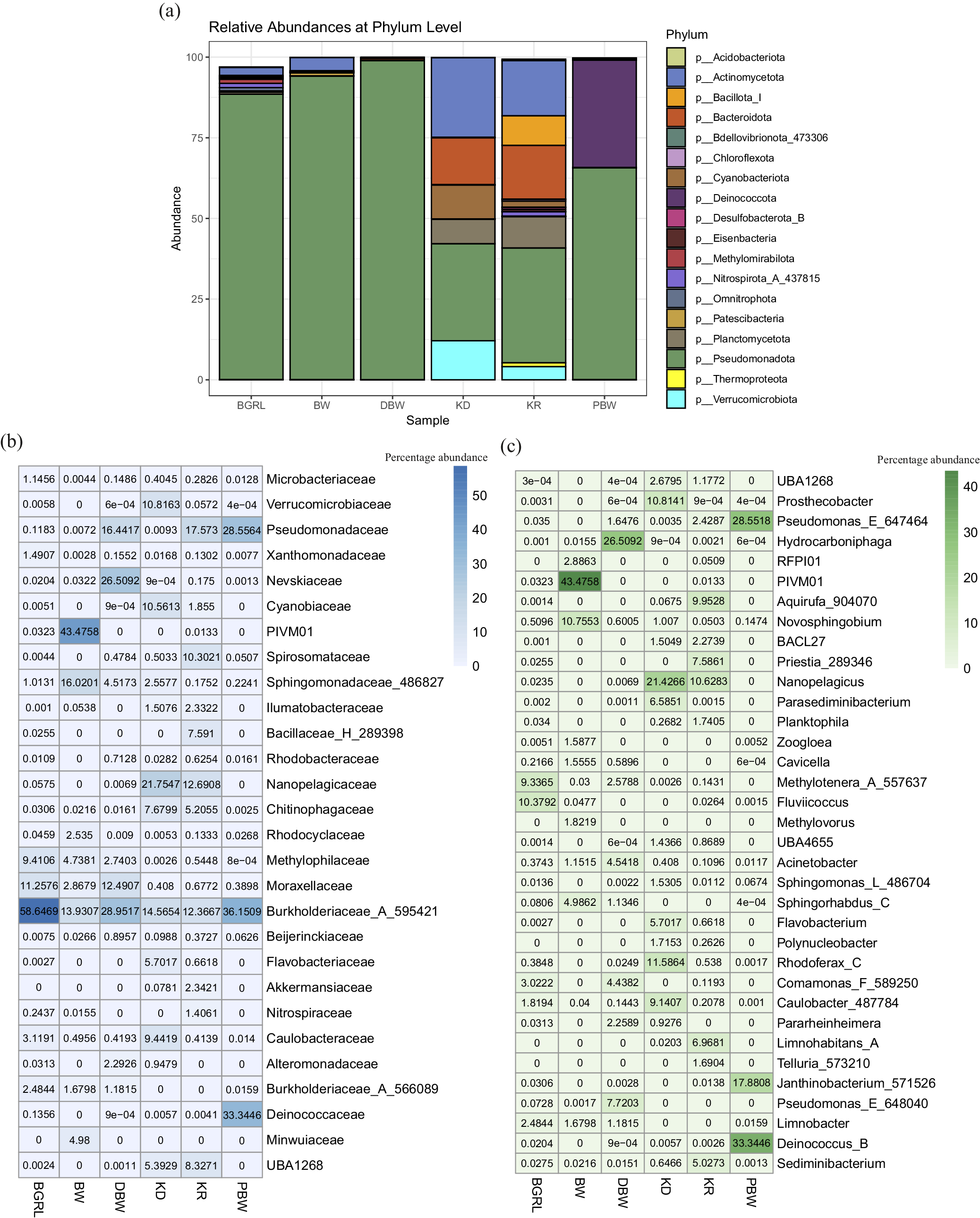

Taxonomic affiliation showed the presence of 61 bacterial and four archaeal phyla. Pseudomonadota was the most abundant phylum across the samples (Fig. 1a). Based on average abundance, Pseudomonadota accounted for 88.41–98.93% of the groundwater communities, whereas in the surface water it covered only 30.08% (KD) and 35.64% (KR). However, spring water (PBW) showed an abundance of Proteobacteria (65.69%) and Deinococcota (33.34%). The rest of the major populations were consisted of Actinomycetota, Deinococcota, Bacteroidota, Planctomycetota, Verrucomicrobiota, and Cyanobacteriota in the bacterial domain and Thermoproteota and Nanoarchaeota in the archaeal domain. On examining KD and KR, it was interesting to note that Actinomycetota, Bacteroidota, Planctomycetota and Verrucomicrobiota corresponded to significantly higher proportions in these surface water samples in addition to Pseudomonadota.

Figure 1. Microbial community composition of the water samples. (a) Relative abundance of major taxa (at Phylum level) present in the microbial communities. (b and c) Heat maps displaying the relative percentage abundance of major microbial families (b) and genera (c).

Among the most abundant families, Burkholderiaceae_A_595421 was detected as the predominant one across the three deep groundwater samples (13.93–58.65%), followed by PIVM01 (in class Gammaproteobacteria, 0–43.46%), Moraxellaceae (2.87–12.49%), and Nevskiaceae (0.02–26.51%) (Fig. 1b, Table S4). Among the other major taxa in groundwater samples, Sphingomonadaceae_486827, Methylophilaceae and Pseudomonadaceae, along with Burkholderiaceae_A_566089, Minwuiaceae and Caulobacteraceae, were detected in fewer groundwater samples. Surface water microbial communities (for samples KD and KR) were dominated by Nanopelagicaceae (12.69–21.75%), Burkholderiaceae_A_595421 (12.37–14.57%), Pseudomonadaceae (0.009–17.57%), UBA1268 (under order Pirellulales, 15.39–8.33%), Chitinophagaceae (5.21–7.68%), and Cyanobiaceae (1.86–10.56%). The spring water community was found to be quite interesting because it was mainly composed of members of only three families, each present in nearly equal proportions (Burkholderiaceae_A_595421 [36.15%], Deinococcaceae [33.34%], Pseudomonadaceae [28.56%]) and together covering 98.05%.

Among the taxa which could be identified at the genera level PIVM01, Hydrocarboniphaga, Methylotenera_A_557637, Novosphingobium, Fluviicoccus, Pseudomonas_E_648040, Comamonas_F_589250, Sphingorhabdus_C (Nevskiaceae), Acinetobacter, and Limnobacter were most prominent in the groundwater. Cavicella, Pararheinheimera, Caulobacter_487784 etc., were the other prominent genera present in these samples. In comparison to the groundwater, the surface water samples showed a characteristic abundance of unclassified Nanopelagicus, Rhodoferax_C, Prosthecobacter, Aquirufa_904070, Caulobacter_487784, Priestia_289346, Limnohabitans_A and Parasediminibacterium. Deinococcus_B, Pseudomonas_E_647464, and Janthinobacterium_571526 members were the major genus (covering 79.77% of the community) represented in the spring water community. Phylogenetic analysis of the predominant ASVs from the major orders showing high sequence identity and resemblance with organisms of similar taxonomic groups reported from deep subsurface, igneous crust or volcanic or other extreme environments corroborated their strong ecological, physiological and metabolic attributes (Fig. S4).

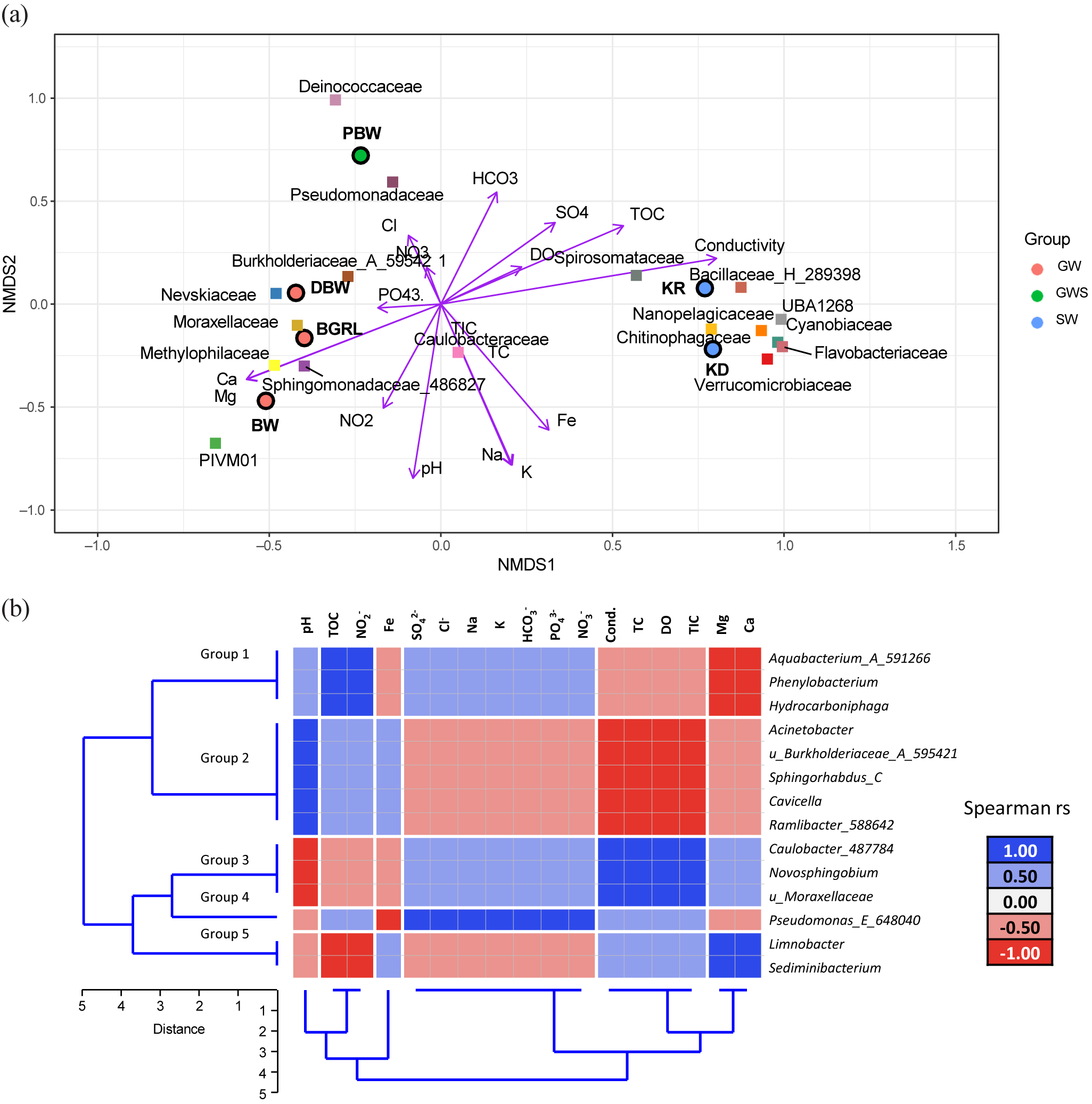

Non-metric multidimensional scaling was used to describe the distribution of different samples according to the relative abundance of microbial taxa in relation to geochemical parameters (Fig. 2a). The figure highlights the geochemical variability among the samples and demonstrates their relative control on the microbial community composition. A set of environmental parameters, especially pH, NO2–, PO43–, Ca, K, and Mg, explained their control in shaping the groundwater community mostly through regulating the abundance of Burkholderiaceae_A_595421, Nevskiaceae, Sphingomonadaceae_486827, PIVM01 (in class Gammaproteobacteria), Methylophiliaceae and Moraxellaceae. Greater TOC, DO, HCO3–, and conductivity segregated the surface water samples and the spring water with major contributions from Spirosomataceae, Verrucomicrobiaceae, Cyanobiaceae, Chitinophagaceae, Flavobacteriaceae, and Bacillaceae_H_289398.

Figure 2. (a) Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot of major microbial families with geochemical parameters (stress: 2.740543 × 10–5). In the NMDS plot, the circles represent samples, the squares represent families and the vector represents geochemical parameters. GW, groundwater; GWS, groundwater seepage; SW, surface water. (b) Heatmap of the Spearman correlations between core amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) with the geochemical parameters. Dendrogram displaying the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA)-based clustering of microbial classes and the geochemical parameters.

Analysis of the core community of the groundwater

Sixteen ASVs of the groundwater community constituted the core microbiome (shared ASVs across three groundwater samples) (Table S6). Identification of these compositional core members was considered to be imperative in terms of providing the foundation for understanding the unique contribution of dominant, rare and common taxonomic groups (Shade and Handelsman, Reference Shade and Handelsman2012). Taxonomic analysis of the shared ASVs showed their affiliation with three classes and eight families. A maximum number of the core ASVs (11 of 16 ASVs) were affiliated with Gammaproteobacteria (major family, Burkholderiaceae, Moraxellaceae), followed by Alphaproteobacteria (four of 16 ASVs, Sphingomonadaceae and Caulobacteraceae) and Bacteroidia (one ASV in the core microbiome, Chitinophagaceae).

The distribution patterns of the core ASVs (at class level) correlated with the geochemical parameters, and they clustered in five groups mainly according to the geochemistry of the water samples (Fig. 2b). Hydrocarboniphaga, Aquabacterium_A_591266 and Phenylobacterium (members of Group 1) were positively correlated with TOC. In contrast, Limnobacter and Sediminibacterium (members of Group 5) were negatively correlated with TOC. Group 2 members (Acinetobacter, uncultured Burkholderiaceae_A_595421, Sphingorhabdus_C, Cavicella and Ramlibacter_588642) were positively correlated with pH, whereas Group 3 (Caulobacter_487784, Novosphingobium and u_Moraxellaceae) members were negatively correlated with pH. Pseudomonas_E_648040 (member of Group 4) was found to be positively correlated with SO42–, Cl–, Na, K, HCO3–, PO43– and NO3–. Members of Group 2 were negatively correlated with conductivity, total carbon, DO and TIC, whereas members of Group 3 were positively correlated with the same environmental variables.

Analysis of metagenome-assembled genomes

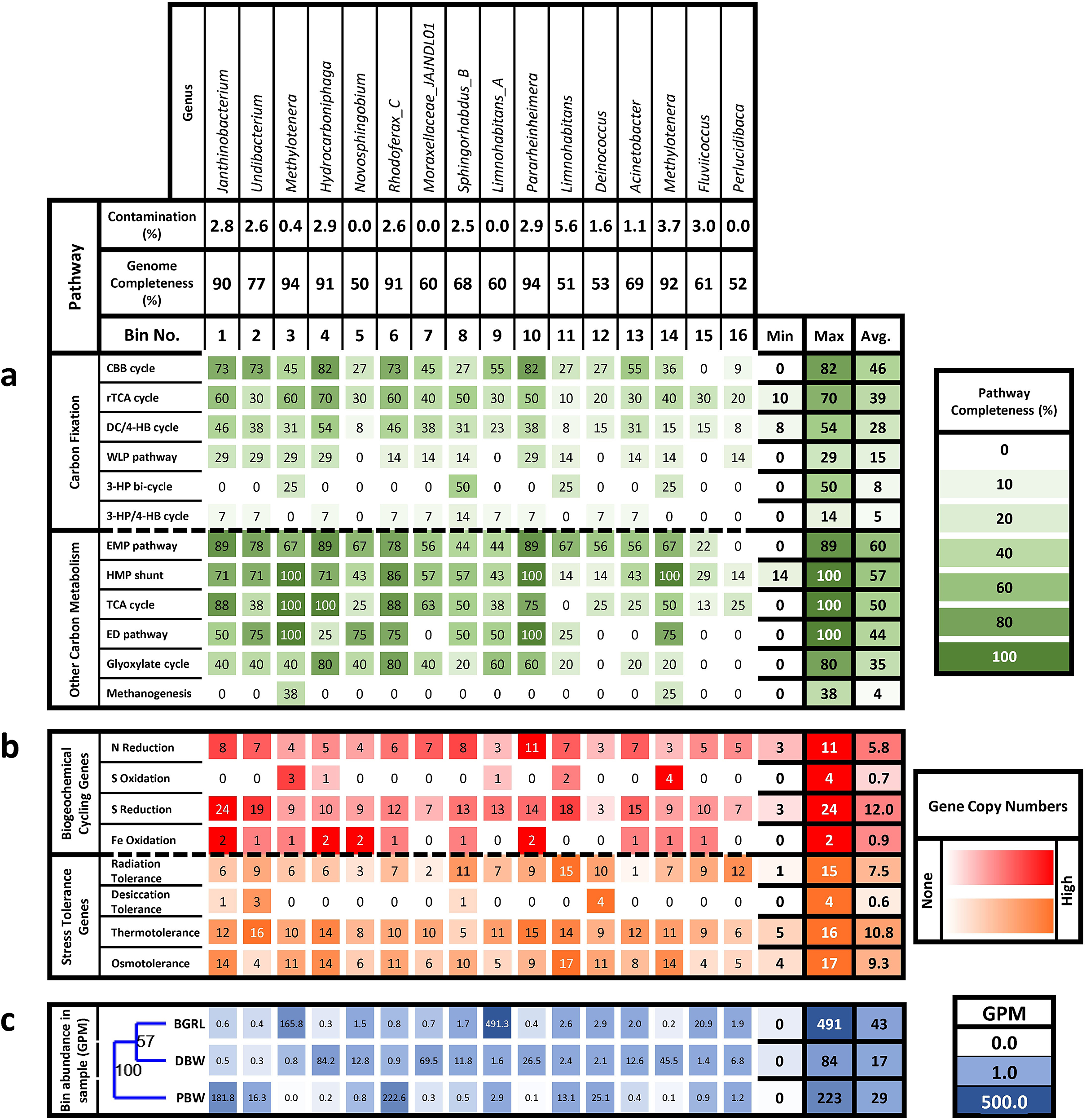

Whole metagenome data from two groundwater samples (BGRL and DBW) and the spring water (PBW) yielded six high-quality (>90% completeness and <5% contamination) and 10 medium-quality (>50% completeness and <10% contamination) bins (Table S7). Quality thresholds suggested by Bowers et al. (Reference Bowers, Kyrpides, Stepanauskas, Harmon-Smith, Doud, Reddy, Schulz, Jarett, Rivers and Eloe-Fadrosh2017) were followed. These genomic bins were used for detailed annotation and analysis (Fig. 3; Table S8). The selected medium and high-quality draft bins showed affiliation to diverse bacterial taxa spanning the families Alteromonadaceae (genus Pararheinheimera), Burkholderiaceae (Rhodoferax, Janthinobacterium, Undibacterium and Limnohabitans), Deinococcaceae (Deinococcus), Methylophilaceae (Methylotenera), Moraxellaceae (Acinetobacter, Fluviicoccus, Perlucidibaca and JAJNDL01), Nevskiaceae (Hydrocarboniphaga), and Sphingomonadaceae (Sphingorhabdus and Novosphingobium). Among these, all but Deinococcus were members of phylum Pseudomonadota (formerly Proteobacteria). Of the Pseudomonadota, 13 bins were of class Gammaproteobacteria and two were of Alphaproteobacteria.

Figure 3. Heatmap of: (a) percentage completeness of carbon metabolism pathways in each bin; (b) abundance of genes involved in biogeochemical cycling and stress tolerance in terms of copies per bin; and (c) bin abundance in each sample expressed as genome copies per million filtered reads (GPM). The samples were clustered via unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) according to bin abundances based on the Bray–Curtis similarity index with a bootstrap of 1000.

Abundances of the bins across the samples were compared and it was found that all bins were present in all the samples, although their abundance varied considerably from <1 to 491 genome copies per million filtered reads, thus suggesting a ubiquity of these members. The most abundant bins in BGRL were 9, 3, 15, 12, and 11, affiliated to the genera Limnohabitans, Methylotenera, Fluviicoccus, Deinococcus, and Limnohabitans, respectively, all of which were present in the other samples in low to moderate abundances. PBW was dominated by bins 6, 1, 12, 2, and 11 (Rhodoferax, Janthinobacterium, Deinococcus, Undibacterium and Limnohabitans, respectively) of which bins 11 and 12 are shared with BGRL. Bins. 4, 7, 14, 10, and 5 (Hydrocarboniphaga, Moraxellaceae genus JAJNDL01, Methylotenera, Pararheinheimera, and Novosphingobium, respectively), were predominant in DBW, all of which showed low abundance in the other two samples. UPGMA clustering of metagenome samples on the basis of bin abundances using the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity showed that both groundwater samples (BGRL and DBW) could be grouped together, while the spring water (PBW) was grouped separately (Fig. 3c).

Metabolic potentials of MAGs

Analyses of the genes related to carbon metabolism provided a broad overview of the genomic potential for carbon fixation and its utilisation via catabolic pathways (Fig. 3; Table S8). Genes encoding inorganic carbon fixation by six pathways were present in the reconstructed genomes. The most complete pathway for carbon fixation was the Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) cycle, followed by the reductive tricarboxylic acid (rTCA or Arnon–Buchanan) cycle, the dicarboxylate–hydroxybutyrate (DC/4–HB) cycle, the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway (WLP), the 3-hydroxypropionate bi-cycle, and the 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle. Among these, genes for the rTCA and DC/4-HB cycle were present in all the bins, although pathway completeness was low. The observed lack of completeness could be due to the limitation of the sequencing technique instead of the actual absence of genes, and it might be possible that at least some members of these microbial communities are capable of lithoautotrophic metabolism. Other carbon metabolism pathways that were detected include the hexose monophosphate shunt (HMP shunt or pentose phosphate pathway), the tricarboxylic acid cycle, and the Entner–Doudoroff pathway, which were complete in some of the bins. Because the presence of complete pathways was seen in bins with greater completeness, it is probable that the absence of genes is due to bin incompleteness. Incomplete genes were detected for the Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas pathway, glyoxylate cycle, and methanogenesis.

The bins were further assessed for the abundance of genes associated with biogeochemical cycles and stress tolerance (Fig. 3; Table S9). Based on the incompleteness of the reconstructed bins and their pathways, the absence of genes was not regarded as evidence of a complete lack of function. Furthermore, the presence of genes was compared in terms of the abundance of gene copies to determine the preponderance of specific metabolic functions. All bins showed the presence of nitrate reduction genes, while oxidative genes were not detected. Specifically, nitrate, nitrite, and nitric oxide reductases were detected. Similarly, sulfur reduction gene copies outweighed oxidative genes. However, iron oxidation genes were detected from most bins. Genes conferring tolerance against radiation, thermal, and osmotic stresses were detected from all bins, but desiccation tolerance genes were not detected from most bins.

Metagenomic comparison among the rock and groundwater systems

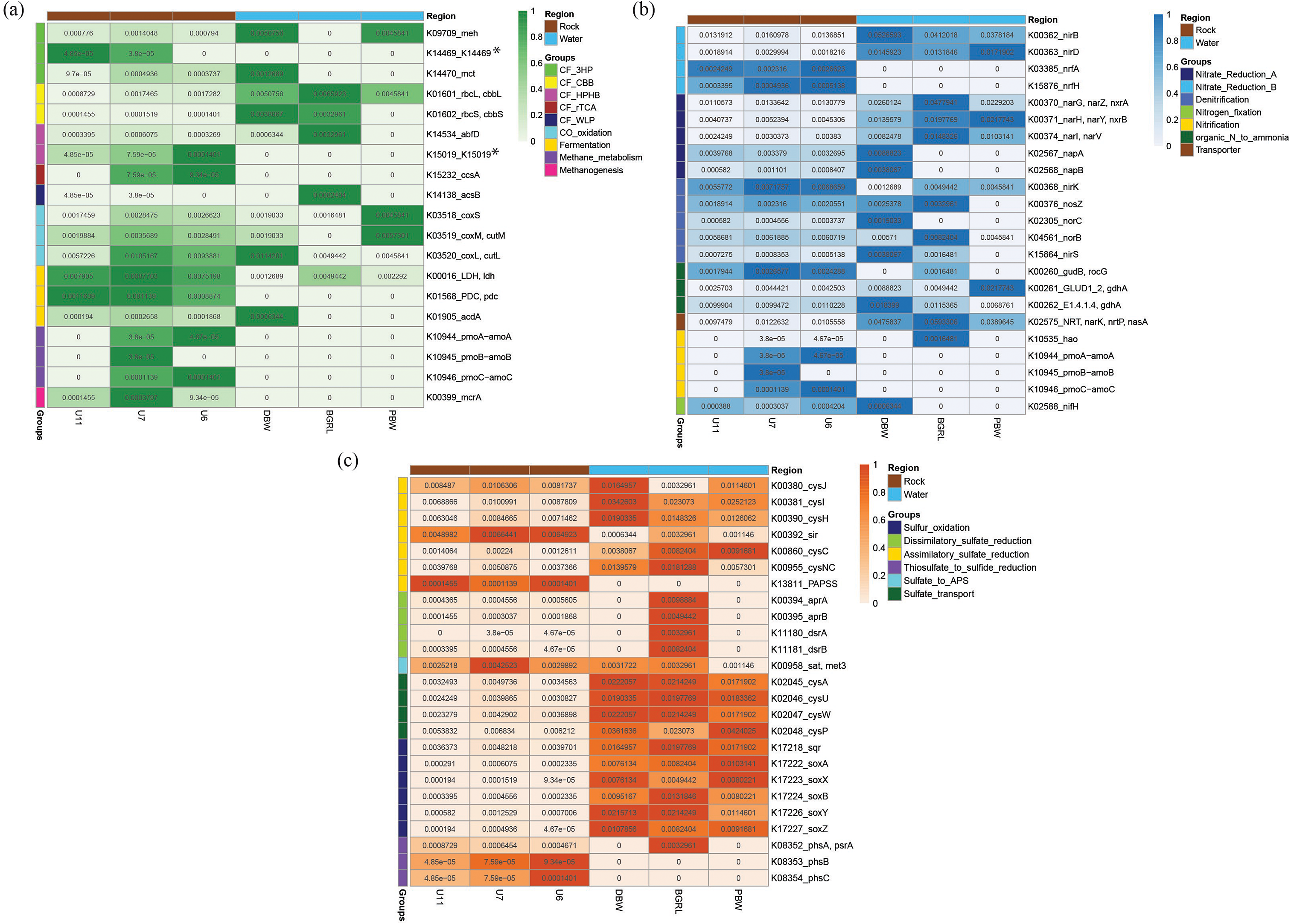

Comparing the metagenomic data sets revealed differences in the predominant carbon and energy metabolism pathways between groundwater and crustal (rock) microbiome (Fig. 4), as previously published (Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Dutta Gupta, Gupta, Sarkar, Roy, Mukherjee and Sar2018). With respect to carbon fixation pathways, CBB was found to be the most abundant pathway across the groundwater system. Genes for WLP (acsB) were found to be the highest in one of the groundwater samples (BGRL) compared to other rocks and water samples. Genes responsible for methylotrophy were not detected in the water samples, whereas genes related to methylotrophy were detected in basalts and transition zone rock samples. Interestingly, genes responsible for methanogenesis (mcrA) were ubiquitous in the rocks and were absent in the groundwater ecosystem.

Figure 4. Heatmap showing occurrences (minimum–maximum scaled based on rows) of genes related to (a) carbon cycle, (b) nitrogen cycle, and (c) sulfur cycle across three rock samples and three water samples. The number represented in each cell of the heatmap denotes the relative percentage occurrences of genes, which is calculated based on the occurrence of a particular gene/total number of genes predicted × 100. The values are rounded to seven decimal points. The colour codes signify a particular gene’s highest and lowest abundance across six samples for comparing rock and water samples. Nitrate_Reduction_A is a group of genes needed for the reduction of nitrate to nitrite, whereas Nitrate_Reduction_B is a group of genes involved in dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium. The CF prefix in the carbon cycle heatmap signifies carbon fixation pathways. CF_3HP, 3-hydroxypropionate bi-cycle; CF_CBB, Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) cycle; CF_HPHB, hydroxypropionate-hydroxybutyrate cycle; CF_rTCA, reverse tricarboxylic acid cycle; CF_WLP, Wood–Ljungdahl pathway. *Gene found in the CF_3HP and CF_HPHB pathways.

With respect to nitrogen and sulfur metabolism, groundwater and rock systems showed stark differences. The gene encoding for nitrogenase (nifH; plays an important role in nitrogen fixation) was ubiquitous in the rocks but only observed in one of the water samples (DBW). However, genes related to the conversion of nitrate to nitrite (both cytoplasmic [nar] and periplasmic [nap] nitrate reductase) were present in higher abundances in the water samples compared to the rocks. Genes involved in sulfate respiration (apr and dsr) were found to be most abundant in one of the groundwater samples (BGRL) compared to other rocks and water samples. Interestingly, genes involved in dissimilatory sulfate reduction were not observed in any other water samples except for BGRL. In the sulfur cycle, major distinctions across water and rock samples were observed with respect to sulfur oxidation and sulfate transport. Genes involved in sulfur oxidation and sulfate transport were higher in water samples than in rock samples.

Discussion

Geochemical characteristics and microbial abundance

Our geomicrobiological investigation demonstrated clearly a strong stratification of microbial community composition and function within the groundwater and surface water systems. Results indicated that different environmental factors, including nutrient sources present in a particular habitat, shaped microbial ecosystems. Deep subsurface aquifers hosted by crystalline igneous crusts are mostly isolated from surface activities and devoid of surface-derived carbon and energy sources (Kieft, Reference Kieft and Hurst2016). The oligotrophic, typically extreme, ecosystems are predominantly driven by chemolithoautotrophy using locally available inorganic electron donors and energy sources. Microorganisms occupying these habitats are found to be endowed with the ability to use the local resources as nutrient substrates (Beaver and Neufeld, Reference Beaver and Neufeld2024; Kazy et al., Reference Kazy, Sahu, Mukhopadhyay, Bose, Mandal, Sar, Pandey and Sharma2021; Kieft, Reference Kieft and Hurst2016; Momper et al., Reference Momper, Casar and Osburn2023).

The geochemical data obtained in this study presented the characteristic features of the igneous rock-hosted groundwater of the Deccan Traps, indicating the possible role of these local factors in impacting the inhabitant microbial communities. Among the major parameters tested, groundwater ecosystems of the Deccan Traps were found to be constrained by pH, TOC, TIC, Mg2+, Ca2+, NO3–, Fe3+, and SO42–. In comparison to various other continental subsurface water (e.g. Fennoscandian Shield, Precambrian bedrock of Witwatersrand basin, etc.) (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Lamminmäki, Alneberg, Andersson, Qian, Xiong, Hettich, Balmer, Frutschi and Sommer2018; Lau et al., Reference Lau, Kieft, Kuloyo, Linage-Alvarez, Van Heerden, Lindsay, Magnabosco, Wang, Wiggins and Guo2016; Magnabosco et al., Reference Magnabosco, Ryan, Lau, Kuloyo, Sherwood Lollar, Kieft, Van HeerDen and Onstott2016; Nyyssönen et al., Reference Nyyssönen, Hultman, Ahonen, Kukkonen, Paulin, Laine, Itävaara and Auvinen2014; Purkamo et al., Reference Purkamo, Bomberg, Kietäväinen, Salavirta, Nyyssönen, Nuppunen-Puputti, Ahonen, Kukkonen and Itävaara2016), groundwater from the Deccan Traps basaltic crust was found to be considerably deprived of organic carbon (3.5–6.4 times less than others), and corroborated well with the TOC level of deep basaltic rocks of the studied region reported earlier (Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Dutta Gupta, Gupta, Sarkar, Roy, Mukherjee and Sar2018). The moderately alkaline nature of the groundwater of the Deccan Traps, along with elevated levels of Ca and Mg, was in line with the abundance of aluminium silicate or carbonate-rich minerals in the host rocks, including Ca/Mg bearing Mg-phyllosilicates, Mg-carbonates, clinopyroxene, calcic plagioclase, etc. (Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Dutta Gupta, Gupta, Sarkar, Roy, Mukherjee and Sar2018). The alkalinity and abundance of Ca and Mg seemed to be more like a characteristic chemical property of igneous crust-hosted deep water, as also reported earlier in multiple studies (Itävaara et al., Reference Itävaara, Nyyssönen, Kapanen, Nousiainen, Ahonen and Kukkonen2011; Kieft et al., Reference Kieft, McCuddy, Onstott, Davidson, Lin, Mislowack, Pratt, Boice, Lollar and Lippmann-Pipke2005; Magnabosco et al., Reference Magnabosco, Ryan, Lau, Kuloyo, Sherwood Lollar, Kieft, Van HeerDen and Onstott2016; Nyyssönen et al., Reference Nyyssönen, Bomberg, Kapanen, Nousiainen, Pitkänen and Itävaara2012; Purkamo et al., Reference Purkamo, Bomberg, Kietäväinen, Salavirta, Nyyssönen, Nuppunen-Puputti, Ahonen, Kukkonen and Itävaara2016). Distinctly higher concentrations of Mg, Ca, NO3–, and PO43– in two groundwater samples (BGRL and DBW) and the spring water (PBW) could be inferred as an outcome of subsurface rock–water interactions and different active biogeochemical processes, sourced by breakdown/weathering of various rock minerals affecting the water chemistry. Low bacterial abundance (up to 104 cells mL–1) of the groundwater compared to other igneous crust-hosted water systems of comparable depths portrayed another characteristic property, which could be linked with the overall thermodynamic and nutritional constraints (including lack of readily metabolisable C and energy sources, reduced level of electron acceptors, etc.) of the igneous crust hosted groundwater (Kieft et al., Reference Kieft, McCuddy, Onstott, Davidson, Lin, Mislowack, Pratt, Boice, Lollar and Lippmann-Pipke2005; Purkamo et al., Reference Purkamo, Bomberg, Nyyssönen, Ahonen, Kukkonen and Itävaara2017; Sahl et al., Reference Sahl, Schmidt, Swanner, Mandernack, Templeton, Kieft, Smith, Sanford and Callaghan2008; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Holmfeldt, Hubalek, Lundin, Åström, Bertilsson and Dopson2016a).

Microbial ecology of the water systems

Microbial communities retrieved from different parts of the water system of the igneous province of the Deccan Traps were characterised as having low microbial abundance, dominated by bacteria with limited species richness and abundance. Microbial communities in the groundwater were less diverse than the microbial communities of the surface water. Among the samples from the deep subsurface, BGRL showed higher abundances of archaeal presence compared to other groundwater samples (more archaeal ASVs corroborate with qPCR-based detection of archaea-specific 16S rRNA reads). In general, the predominance of bacteria over archaea in deep aquifer ecosystems has been reported to be a characteristic phenomenon (Kadnikov et al., Reference Kadnikov, Mardanov, Beletsky, Banks, Pimenov, Frank, Karnachuk and Ravin2018). Nevertheless, a few archaea-based investigations (including the one from the Deccan Traps) indicated their distinct presence and highlighted biogeochemically relevant functions coupling Fe and S oxidation and C metabolism (Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Sar, Sarkar, Dutta Gupta, Gupta, Bose, Mukherjee and Roy2019b; Probst et al., Reference Probst, Ladd, Jarett, Geller-Mcgrath, Sieber, Emerson, Anantharaman, Thomas, Malmstrom and Stieglmeier2018; Purkamo et al., Reference Purkamo, Bomberg, Kietäväinen, Salavirta, Nyyssönen, Nuppunen-Puputti, Ahonen, Kukkonen and Itävaara2016; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Holmfeldt, Hubalek, Lundin, Åström, Bertilsson and Dopson2016a). One of the most interesting findings was the prevalence of 16 ASVs as members of the core populations of this subsurface habitat; however, their total relative abundances varied across different groundwater samples (BGRL 4.69%, BW 12.17%, DBW 36.95%). The presence of a few ASVs as core communities of deep igneous crust ecosystems has been observed previously and identified to be of central importance in deep biosphere community function (Boada et al., Reference Boada, Santos-Clotas, Cabrera-Codony, Martín, Bañeras and Gich2021; Sahu et al., Reference Sahu, Kazy, Bose, Mandal, Dutta, Saha, Roy, Dutta Gupta, Mukherjee and Sar2022; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Herrmann, Kampe, Lehmann, Totsche and Küsel2020).

Our 16S rRNA gene-based community profiling provided an overview of the aquatic microbial ecosystems of the Deccan Traps. The presence of Pseudomonadota as the single most abundant phylum in groundwater samples, with its members known to be capable of performing various important biogeochemical transformations (of C, N, S, etc.), necessary for providing essential metabolic resources to the inhabitant microorganisms, was noticed. The predominance of Pseudomonadota (formerly Proteobacteria) corroborated previous reports on the cosmopolitan distribution of these bacteria in various subsurface water systems (groundwater, fracture-fault water, etc.) of Colorado, the Fennoscandian Shield, and the Witwatersrand basin (Lau et al., Reference Lau, Kieft, Kuloyo, Linage-Alvarez, Van Heerden, Lindsay, Magnabosco, Wang, Wiggins and Guo2016; Nyyssönen et al., Reference Nyyssönen, Hultman, Ahonen, Kukkonen, Paulin, Laine, Itävaara and Auvinen2014; Onstott et al., Reference Onstott, Moser, Pfiffner, Fredrickson, Brockman, Phelps, White, Peacock, Balkwill and Hoover2003; Purkamo et al., Reference Purkamo, Bomberg, Kietäväinen, Salavirta, Nyyssönen, Nuppunen-Puputti, Ahonen, Kukkonen and Itävaara2016; Sahl et al., Reference Sahl, Schmidt, Swanner, Mandernack, Templeton, Kieft, Smith, Sanford and Callaghan2008). The abundance of Pseudomonadota members also highlighted their metabolic versatility and major environmental importance within the deep biosphere ecosystems. Niche-specific distinct community composition across the subsurface environment (compared to their surface counterparts) indicated the role of local geochemical factors. Family-level community data, as well as the core ASV-based correlation analyses, confirmed the patterns of community assemblages and their relationship with geochemical parameters. Higher values of pH, NO2–, NO3–, and PO43– influenced the abundance of Burkholderiaceae_A_595421, Nevskiaceae, Sphingomonadaceae_486827, PIVM01 (in class Gammaproteobacteria), Methylophiliaceae, and Moraxellaceae. The distinct patterns of microbial assemblages in groundwater (with the dominance of Moraxellaceae, Methylophilaceae and Sphingomonadaceae along with Burkholderiaceae and Nevskiaceae) could be inferred as their characteristic lineages with deep aquatic ecosystems, as also evidenced by several investigations on other subterranean water samples (Itävaara et al., Reference Itävaara, Nyyssönen, Kapanen, Nousiainen, Ahonen and Kukkonen2011; Jangir et al., Reference Jangir, Karbelkar, Beedle, Zinke, Wanger, Anderson, Reese, Amend and El-Naggar2019; Nyyssönen et al., Reference Nyyssönen, Hultman, Ahonen, Kukkonen, Paulin, Laine, Itävaara and Auvinen2014; Purkamo et al., Reference Purkamo, Bomberg, Kietäväinen, Salavirta, Nyyssönen, Nuppunen-Puputti, Ahonen, Kukkonen and Itävaara2016). In particular, Moraxellaceae, Burkholderiaceae, etc. could be designated as resident bacterial taxa of the deep biosphere in crystalline groundwater.

Further analysis of the metabolic properties of various taxa detected in the deep subsurface of the Deccan Traps portrayed the broad functional abilities and their biogeochemical significance. One of the unifying themes that emerged was the primary role of the chemolithoautotrophic mode of metabolism, along with nitrate reduction. In line with the observations made by Deja-Sikora et al. (Reference Deja-Sikora, Gołębiewski, Kalwasińska, Krawiec, Kosobucki and Walczak2019), our taxonomic data clearly indicated that inorganic carbon fixation coupled with sulfur/iron oxidation and nitrate reduction constituted the community’s energy-circuit under the prevailing (relatively) nitrate-rich anoxic condition. Other energy metabolism pathways (e.g. H2 or Fe2+ oxidation) could also be involved. Among the predominant bacterial taxa, Acinetobacter and Methylotenera were detected. Oxidation of sulfur compounds and denitrification have been well reported in other major taxa of Moraxellaceae (Acinetobacter) and Methylophilaceae (Methylotenera) (Y. Liu et al., Reference Liu, Song, Jiang, Liu, Xu, Li and Liu2011; Song et al., Reference Song, Choo and Cho2008; Su et al., Reference Su, Shi and Ma2017). Utilisation of C1 compounds (e.g. methane, methanol, formate, etc.), other hydrocarbons (alkanes), and biomineralisation (of carbonates) under oligotrophic settings by these taxa were very relevant as these compounds can be generated in deep igneous systems through geogenic or biogenic synthesis (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Huang, Xie, Zhang, Wei, Li, Ma, Luo and Ding2021; Y. Liu et al., Reference Liu, Song, Jiang, Liu, Xu, Li and Liu2011). The presence of the hydrocarbon degrading capability of subsurface microbial communities is further supported by the presence of Novosphingobium, Hydrocarboniphaga and Sphingorhabdus in the groundwater samples (Jeong et al., Reference Jeong, Jin and Jeon2016; H. Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yao, Yuan, Chen, Wang, Masakorala and Choi2016; Segura et al., Reference Segura, Hernández-Sánchez, Marqués and Molina2017).

In contrast to the prevalence of the chemolithoautotrophic organisms in the deep groundwater, surface water ecosystems could be characterised through heterotrophic bacterial activities. The most abundant taxa therein, namely, Nanopelagicaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, UBA1268 (affiliated to Planctomycetota), Chitinophagaceae, etc., were reported earlier to occupy freshwater and eutrophic reservoirs, water column/streams and wetlands (Aizenberg-Gershtein et al., Reference Aizenberg-Gershtein, Vaizel-Ohayon and Halpern2012; Andrei et al., Reference Andrei, Salcher, Mehrshad, Rychtecký, Znachor and Ghai2019; Hosen et al., Reference Hosen, Febria, Crump and Palmer2017; Neuenschwander et al., Reference Neuenschwander, Ghai, Pernthaler and Salcher2018; Newton and McLellan, Reference Newton and McLellan2015; Serra Moncadas et al., Reference Serra Moncadas, Hofer, Bulzu, Pernthaler and Andrei2024; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang, Anantharaman, Wang, Zhang, Zhang and Xu2025). The presence of cyanobacterial members supported their role in providing photosynthetically fixed carbon that aids the growth of heterotrophic and chemoorganotrophic microbial groups. The spring water (PBW) microbiome displayed the presence of extreme stress-tolerant Deinococcaceae (Deinococcus), which corroborates well with our recent findings on similar organisms in deep granitic crusts underneath the Deccan Traps (Sahu et al., Reference Sahu, Kazy, Bose, Mandal, Dutta, Saha, Roy, Dutta Gupta, Mukherjee and Sar2022).

Core communities have been considered to represent the stable fraction of a community. Identifying these members and their geochemical drivers was considered to be imperative in gaining insights into the foundation (Shade and Handelsman, Reference Shade and Handelsman2012; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Herrmann, Kampe, Lehmann, Totsche and Küsel2020; Sahu et al., Reference Sahu, Kazy, Bose, Mandal, Dutta, Saha, Roy, Dutta Gupta, Mukherjee and Sar2022). Earlier studies of the endolithic microbial communities inhabiting the Archean granitoid basement underneath the Deccan Traps identified the presence of microbial communities whose abundances varied with the prevailing lithology and geochemistry (Sahu et al., Reference Sahu, Kazy, Bose, Mandal, Dutta, Saha, Roy, Dutta Gupta, Mukherjee and Sar2022). The variability of the abundances of core ASVs across various deep groundwater samples further indicated niche partitioning of the subsurface water system. Correlation analysis of these core ASVs with groundwater hydrochemistry alluded to the presence of both autotrophy and heterotrophy in the groundwater environment. In an oligotrophic deep subsurface environment, chemoautotrophic CO2 fixation, with energy derived through oxidation of inorganic substrate coupled with NO3 reduction, might be a plausible metabolic route to drive in the deep biosphere (Lau et al., 2017). The products of autotrophy could be utilised by different heterotrophs in the community. The presence of autotrophy could be further validated by the fact that major taxonomic members of the groundwater samples have manifested similar metabolisms in previous reports. Iron or sulfur oxidation coupled with nitrate reduction-driven autotrophic carbon fixation has been reported in deep groundwater settings (Lau et al., Reference Lau, Kieft, Kuloyo, Linage-Alvarez, Van Heerden, Lindsay, Magnabosco, Wang, Wiggins and Guo2016; Lopez-Fernandez et al., Reference Lopez-Fernandez, Simone, Wu, Soler, Nilsson, Holmfeldt, Lantz, Bertilsson and Dopson2018).

Comparison of metagenomic bins and assessing the biogeochemical potential

A comparison of bin abundances across the metagenome samples revealed that groundwater communities were significantly different from spring water communities. This difference could be attributed to the distinct physicochemical conditions that prevailed in these two habitats. Because most bins were present in all the samples, inter-mixing of groundwater and spring water would be highly probable, allowing the presence of a few common microbial species. Nevertheless, the observed differences in the abundance of individual bins probably arose because each sample forms a microenvironment that allows the selection of a particular section of the total community.

On comparing the taxonomic lineages of the bins from metagenome data with 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing results, members of Pseudomonadota (formerly phylum Proteobacteria) remained the most prominent phylum, with representatives of classes Gammaproteobacteria and Alphaproteobacteria. Similarly, metagenome data also corroborated the status of Deinococcota (formerly phylum Deinococcus-Thermus) as the next most abundant phylum. The overall genome copies per million filtered reads were highest for BGRL, followed by PBW and DBW. This trend did not match what was seen in amplicon data, but the differences could be explained in light of practical limitations of sequencing technique rather than actual absence. Major families of groundwater samples as detected from whole metagenome analysis (Burkholderiaceae, Moraxellaceae, Methylophilaceae, Nevskiaceae, Sphingomonadaceae) were detected from amplicon analysis as well. On the other hand, preponderant surface water families (Nanopelagicaceae, Chitinophagaceae, Verrucomicrobioaceae, Flavobacteriaceae) were not represented in the genomes reconstructed from metagenome analysis. The taxonomy of reconstructed genomes thus corroborated the 16S rRNA gene amplicon-based analysis. Burkholderiaceae and Alteromonadaceae were low or sparse in amplicon data but had metagenomic bins affiliated to them, highlighting the superiority of whole metagenome-based community analysis. At a lower taxonomic level, metagenome data retained multiple genera (i.e. Limnohabitans, Perlucidibaca, Acinetobacter, Hydrocarboniphaga, Methylotenera) also detected in 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing, thus confirming their presence in the groundwater and spring water. Major taxa detected as core community members of the groundwater microbiome were represented by the reconstructed genomes as well, further validating our observations of the subsurface aquifer microbial communities.

Functional annotation of reconstructed genomes demonstrated a prevalence of chemoautotrophic CO2 fixation pathways. The presence of chemoautotrophy is to be expected, considering the aphotic subsurface ecosystems of the deep biosphere have a minimal supply of photosynthetically produced organic carbon. The low organic carbon status of the igneous crust-hosted aquifers necessitates chemoautotrophy as the only metabolic route for primary production in subterrestrial food webs (Overholt et al., Reference Overholt, Trumbore, Xu, Bornemann, Probst, Krüger, Herrmann, Thamdrup, Bristow and Taubert2022; Templeton and Caro, Reference Templeton and Caro2023). The specific pathways that are employed for carbon fixation vary across habitats, but CBB and rTCA cycles are frequently reported from groundwater studies, alongside WLP (Atencio et al., Reference Atencio, Geisler, Rubin-Blum, Bar-Zeev, Adar, Ram and Ronen2023; Y. Li et al., Reference Li, Zhu, Niu, Zhang, Wang, Zhang, Zou and Zhou2024; Momper et al., Reference Momper, Jungbluth, Lee and Amend2017; Overholt et al., Reference Overholt, Trumbore, Xu, Bornemann, Probst, Krüger, Herrmann, Thamdrup, Bristow and Taubert2022; Probst et al., Reference Probst, Ladd, Jarett, Geller-Mcgrath, Sieber, Emerson, Anantharaman, Thomas, Malmstrom and Stieglmeier2018; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Holmfeldt, Hubalek, Lundin, Åström, Bertilsson and Dopson2016a). Pathways involved in fermentation were found to be complete and abundant. Notably, it has been reported previously that CO2 fixation pathways like the CBB cycle can be used by mixotrophic bacteria in conjunction with sugar fermentation pathways to utilise the CO2 liberated, which minimises loss of organic carbon. Recent studies have shown that organic carbon-lean deep terrestrial subsurface microbial communities have a predominance of multiple heterotrophic (glycolysis, respiratory and fermentation) pathways (along with chemolithoautotrophy) responsible for facilitating oxidation of locally available small and complex (even recalcitrant) organic compounds of both autochthonous and allochthonous types (Atencio et al., Reference Atencio, Geisler, Rubin-Blum, Bar-Zeev, Adar, Ram and Ronen2023; Coskun et al., Reference Coskun, Gomez-Saez, Beren, Doğacan, Günay, Elkin, Hoşgörmez, Einsiedl, Eisenreich and Orsi2024; Ijiri et al., Reference Ijiri, Inagaki, Kubo, Adhikari, Hattori, Hoshino, Imachi, Kawagucci, Morono and Ohtomo2018; Momper et al., Reference Momper, Casar and Osburn2023; Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Dempo, Nakayama, Nakamura, Bamba, Fukusaki and Fukui2015; Valentin-Alvarado et al., Reference Valentin-Alvarado, Fakra, Probst, Giska, Jaffe, Oltrogge, West-Roberts, Rowland, Manga and Savage2024). Our previous studies on oligotrophic, deep (up to 3000 mbs) crystalline igneous rock-hosted microbial communities within and below the Deccan Traps also showed the presence of both chemoautotrophic and heterotrophic pathways, including acetate metabolising and other fermentative metabolisms (Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Dutta Gupta, Gupta, Sarkar, Roy, Mukherjee and Sar2018; Mandal et al., Reference Mandal, Bose, Ramesh, Sahu, Saha, Sar and Kazy2022; Sahu et al., Reference Sahu, Kazy, Bose, Mandal, Dutta, Saha, Roy, Dutta Gupta, Mukherjee and Sar2022). Based on these reports and results obtained in the present study, we infer that deep aquifer microbiomes of the Deccan Traps are capable of an overall mixotrophic mode of metabolism, allowing complete cycling of carbon within this subterranean ecosystem through autotrophic as well as heterotrophic pathways.

The exploration of genes associated with redox reactions of inorganic compounds was able to support only a few of the metabolic functions expected from the assessment of the microbial community, as inferred from amplicon sequence analysis, but this may just be due to inadequate metagenome sampling depth. In spite of this limitation, the presence of a near-complete reductive half of the nitrogen cycle, represented by nitrite reductase, nitrate reductase, and nitric oxide reductase, was metagenomically confirmed. The information gathered from metagenome analysis can be regarded as a preliminary overview of the preferred choice of electron acceptors and donors for these microbial communities, implicating sulfate and oxides of nitrogen as potential electron acceptors. Such prevalence of nitrate and sulfate reducers and iron oxidisers has been reported from other studies of groundwater microbial communities as well, suggesting that these bacteria are key players in subterranean mineral mobilisation and geochemical cycling (Atencio et al., Reference Atencio, Geisler, Rubin-Blum, Bar-Zeev, Adar, Ram and Ronen2023; Y. Li et al., Reference Li, Zhu, Niu, Zhang, Wang, Zhang, Zou and Zhou2024; Momper et al., Reference Momper, Jungbluth, Lee and Amend2017; Overholt et al., Reference Overholt, Trumbore, Xu, Bornemann, Probst, Krüger, Herrmann, Thamdrup, Bristow and Taubert2022; Probst et al., Reference Probst, Ladd, Jarett, Geller-Mcgrath, Sieber, Emerson, Anantharaman, Thomas, Malmstrom and Stieglmeier2018; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Holmfeldt, Hubalek, Lundin, Åström, Bertilsson and Dopson2016a). Because amplicon and metagenome-based studies only allow predictions of such functions, in vitro validation of microbial capacity to carry out the various biogeochemical reactions would be the conclusive proof that can be sought in future studies into the microbial diversity of this region. In addition, the depth of sequencing might also impact the detection of certain genes that are not abundant in the samples.

When stress tolerance genes were investigated, a paucity of desiccation tolerance genes was observed. This may be because the microflora was adapted for growth in water and not frequently exposed to water scarcity, or due to sequence incompleteness. However, the presence of radiation tolerance genes could confer desiccation stress resistance because radiation tolerance genes tend to be associated with desiccation stress resistance as well (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Liu, Zhang and Li2024). Thermotolerance genes detected may arise from deeper groundwater samples as temperature increases with greater depths (Bregnard et al., Reference Bregnard, Leins, Cailleau, Vieth-Hillebrand, Eichinger, Ianotta, Hoffmann, Uhde, Bindschedler and Regenspurg2023). Osmotolerance could be relevant to near-surface and deep subsurface microorganisms as a sudden influx of meteoric water or dissolution of rock minerals can cause sharp and/or localised changes in osmotic pressure (Or et al., Reference Or, Smets, Wraith, Dechesne and Friedman2007; Sokol et al., Reference Sokol, Slessarev, Marschmann, Nicolas, Blazewicz, Brodie, Firestone, Foley, Hestrin and Hungate2022).

Although differences in microbial communities and their functions were observed across subsurface rock (Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Dutta Gupta, Gupta, Sarkar, Roy, Mukherjee and Sar2018) and water systems in the Deccan Traps, their foundations were very similar. These similarities in the bioenergetics of the system were probably due to the result of an exchange of resident microflora taking place during rock–water interactions and the prevalence of similar conditions in the subsurface igneous province. Such interactions were regarded as a major driver of nutrient cycling in the oligotrophic deep biosphere. Rocks provide the mineral solutes that are solubilised in water to serve as nutrients and energy sources for the geochemically active microorganisms inhabiting these niches (Meyer-Dombard and Malas, Reference Meyer-Dombard and Malas2022). The overall data represent preferential recruitment of major metabolism across the aquatic and crustal provinces of the Deccan Traps.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1180/gbi.2025.10004.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES), Government of India, under Project ID:MoES/P.O.(Seismo)/1(181)/2013 dated 7 April 2014; and project ID:MoES/P.O.(Seismo)/1(288)/2016 dated 16 March 2017) for which we are grateful to the Secretary, MoES. We would like to extend our gratitude and special thanks to Dr Sukanta Roy for his immense help and support for field sampling and for guiding us throughout this study. We thank the Director and all the participants and investigators from CSIR-National Geophysical Research Institute, Hyderabad, engaged in the KBH-5 scientific drilling operations in the Koyna-Warna region of the Deccan Traps. We are grateful to Harsh Gupta (National Geophysical Research Institute) and Shailesh Nayak (MoES) for unstinted support. Special thanks to Dr Arun Gupta (MoES) and his office for their consistent administrative support. We thank Ajoy Roy, Balaram Mohapatra, and Surajit Misra for their help and discussion during the field trip. The next-generation sequencing facility created at PS’s laboratory was funded by the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur Challenge Grant (IIT/SRIC/BT/ODM/2015-16/141). AD and SDG gratefully acknowledge the fellowship provided by IIT Kharagpur. SM gratefully acknowledges the fellowship provided by MoES, Government of India. RPS and DM gratefully acknowledge the financial assistance provided by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Government of India. AG thanks the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India for providing a fellowship under the Department of Biotechnology-Junior Research Fellowship category. HB gratefully acknowledges the fellowship provided by the Science and Engineering Board, Department of Science and Technology Government of India. This work used the high-performance computing facility, Param Shakti, of IIT Kharagpur established under National Supercomputing Mission, Government of India, and supported by Centre for Development of Advanced Computing, Pune, India.

Data availability

The raw 16S rRNA gene sequencing data are available in the NCBI SRA database under BioProject ID PRJNA445925 (for water samples) and SRA Accession: SRR35284829 (for reagent control). Whole metagenome raw data and MAG sequences are available under NCBI BioProject ID PRJNA1341937. MAG sequences are also available under ENA Study Accession ID PRJEB100823. The annotated data for the whole metagenome is available at IMG GOLD under Analysis Project ID Ga0247434, Ga0247435 and Ga0247436.

Author contributions