Introduction

The rise of the internet has fundamentally transformed the way that we connect and form communities (Castells, Reference Castells2010). Online communities, defined as "social aggregations that emerge from the Net when enough people carry on those public discussions long enough, with sufficient human feeling, to form webs of personal relationships in cyberspace" (Rheingold, Reference Rheingold1993, p. 5), have become a ubiquitous feature of the digital age. Research has shown that these virtual spaces can have a profound impact on individuals and society (Wellman & Gulia, Reference Wellman, Gulia, Smith and Kollock1999). Online communities offer a platform for people to explore their interests, seek support, engage in meaningful discussions on a wide range of topics, and seek help without fear of judgment or stigma (Bargh et al., Reference Bargh, McKenna and Fitzsimons2002; Gershoff & Mukherjee, Reference Gershoff, Mukherjee, Norton, Rucker and Lamberton2015; Preece, Reference Preece2000). From niche hobbies to global social movements, these digital gathering places have the potential to shape our perspectives, inspire personal growth, and even drive societal change (Castells, Reference Castells2015).

As the world becomes increasingly interconnected, the significance of online communities cannot be overstated. They provide valuable social support and a sense of belonging. For many vulnerable groups, online communities offer easier access to information, advice, and resources that may be difficult to obtain otherwise. This is particularly important for those with mobility issues, limited local support, or those in remote areas. Research has been conducted on online communities for people with chronic conditions (Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Booth, Moore and Mathers2022), mental illness (Naslund et al., Reference Naslund, Aschbrenner, Marsch and Bartels2016), and poverty (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Campbell-Grossman, Keating-Lefler, Carraher, Gehle and Heusinkvelt2009). These studies show that online communities provide crucial support, information, and connections for vulnerable populations, helping to improve their overall well-being and quality of life.

Research has also shown that a sense of community can be established in a virtual space despite physical distance (Mirbahaeddin & Chreim, Reference Mirbahaeddin and Chreim2024). Virtual peer support platforms have shown the ability to engage diverse populations, including men (who are typically less likely to seek mental health support) and underrepresented groups who report higher rates of loneliness (Bravata et al., 2023). Research on online forums for single mothers reveals that members rely on these groups for emotional support, parenting knowledge, work-life balance, companionship, and self-esteem (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Campbell-Grossman, Keating-Lefler, Carraher, Gehle and Heusinkvelt2009), aligning with motivations for social participation (Taylor & Conger, Reference Taylor and Conger2017). This present study brings a different perspective to the ongoing discourse by examining online interactions among single mothers through a symbolic interactionism approach.

Our study suggests that researchers have overlooked a key attribute of online interactions: their necessity for reaching beneficiaries of nonprofit organizations. As a result, this study demonstrates that online interaction is essential for connecting with certain marginalized groups in society. Using insights from Blumer’s symbolic interactionism, this study highlights the significance of online interactions within a peer group for participants. Furthermore, our study draws attention to the need for nonprofit organizations to incorporate online communities into their outreaches.

Although studies have shown how single mothers use the internet, little is known about the effectiveness of online peer support groups on their well-being. Many studies on online support groups focus on people with underlying conditions and diseases (Strand et al., Reference Strand, Eng and Gammon2020; Wright, Reference Wright2016). However, this study aims to contribute to knowledge on the mechanism of effective peer support for vulnerable populations, like single mothers, and the significance of such interactions for individual participants. We believe that understanding effective virtual peer support usage for vulnerable populations will further help nonprofits that focus on this segment of society easily fulfill their mission.

In 2018, Japan's national average for single-parent households was 2.84%, with Okinawa reporting the highest rate at 6.16%, equating to one in every 16 households (e-Stats Japan, 2018). Despite the challenges faced by single-parent households in Japan, their numbers are growing, with over 1.23 million single-mother households reported in April 2021 (JMHLW, 2021). Of employed single mothers in Japan, 44.2% work full-time and 43.8% are part-time workers with unstable incomes (JMHLW, 2021). Despite their employment, the poverty rate among single-parent households in Japan is alarming, ranking 9th highest among OECD countries. Approximately 56% of these households live in poverty, largely due to the unique characteristics of Japan's enterprise wage system (Kota, Reference Kota2023; OECD, 2023).

Single mothers in Japan face numerous economic and social challenges, including insufficient public assistance, employment barriers, social stigma, health issues, and the intergenerational transmission of poverty (Shirahase & Raymo, Reference Shirahase and Raymo2014). Cultural stigma surrounding single motherhood leads to feelings of embarrassment and shame, causing some women to conceal their status from friends, family, and the community (Chisa, Reference Chisa2008; Wright, Reference Wright2016). Th is "culture of shame" is rooted in traditional gender norms that deem single motherhood deviant. Additionally, single mothers in Japan encounter bureaucratic hurdles, judgment from government officials, and a lack of support (Washington Post, 2017).

The homogeneity of Japanese society exacerbates these challenges, as those who deviate from traditional family norms often conceal their situations to avoid judgment (Chisa, Reference Chisa2008). Single mothers navigate numerous obstacles, striving to overcome stigma and achieve financial stability while raising their families. This study argues that participation in online support groups specifically designed for single mothers can help mitigate their struggles and improve their experiences. Therefore, this study examines the significance of virtual peer support participation for vulnerable populations, like single mothers.

Literature Review

The rapid proliferation of online platforms has transformed the landscape of peer support, enabling individuals to connect and share experiences in virtual communities. This literature review aims to explore three main foci, namely: online peer support groups, social participation among peer groups, and nonprofit organizations online outreaches. Examining the theoretical underpinnings and empirical findings related to online support groups, this section seeks to provide a comprehensive understanding of how these virtual spaces promote belonging, influence behavior, and offer a vital source of support for vulnerable populations.

Online Peer Support Groups

Darby (2018) defined peer support groups as involving people who share a common experience or challenge. These groups have increasingly migrated online in recent years. Online peer support groups refer to virtual communities or platforms where individuals facing similar challenges, issues, or experiences come together to offer mutual support, share information, and exchange emotional or practical assistance (Strand et al., Reference Strand, Eng and Gammon2020).

Typically, online peer support groups exist on social media platforms, forums, or dedicated websites, allowing members to connect and communicate on the internet (Kapoor et al., Reference Kapoor, Tamilmani, Rana, Patil, Dwivedi and Nerur2018). They offer a space where individuals can find understanding and empathy from others who share similar circumstances, thereby creating a sense of belonging and social connectedness despite physical distance (Leamy et al., Reference Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams and Slade2011). Online support groups also have the potential to influence individuals' attitudes, behaviors, and coping mechanisms, as well as their perceptions of society and its institutions (Garcia-Alexander et al., Reference Garcia-Alexander, Woo and Carlson2017).

A systematic review of people with chronic conditions carried out by Thompson et al. (Reference Thompson, Booth, Moore and Mathers2022) highlighted the importance of consistency and clarity in how peers are defined. They noted that improved quality of life and self-efficacy were the two most reported benefits of peer support among people with chronic conditions. On the other hand, they stressed that a clear definition would greatly impact the research outcome. Therefore, this study is designed to explore a well-defined peer group that operates online. Accordingly, a peer group in this study is a social group that a person belongs to and is likely influenced by in terms of their values, beliefs, and behaviors.

Existing literature reveals that online support groups have the potential to influence individuals’ behaviors but do not capture how the change is experienced. More importantly, there is a need to highlight what these changes mean for participants in online support groups and how they capture their experiences. So, I brought in Blumer’s theory of symbolic interactionism to review online peer support groups.

Social Participation Among Peer Groups

Émile Durkheim, a pioneer in the field of sociology, believed that social participation was essential for a healthy society and helped prevent anomie, a state of normlessness or confusion (Korgen & White, Reference Korgen and White2014), and peer support groups are seen as a specific form of social participation. This understanding of social participation has led researchers from a range of fields, including psychology, education, and sociology, to investigate the complicated and varied topic of social participation among peer groups. Although there is no concession on how to define social participation, its definition ranges from the total number of contacts a person has (Guillen et al., Reference Guillen, Coromina and Saris2011) to involvement in social groups and activities (Aroogh & Shahboulaghi, Reference Aroogh and Shahboulaghi2020).

Taylor and Conger (Reference Taylor and Conger2017) highlighted increased social support, emotional well-being, and improved coping mechanisms as some of the potential benefits of social participation in online peer support groups. Interestingly, Eysenbach et al. (Reference Eysenbach, Powell, Englesakis, Rizo and Stern2004) carried out a multivariate study and found no clear evidence to support positive health outcomes among participants in online support groups. Seeing how online social networking has become a prominent form of communication in many people's lives (Naslund et al., Reference Naslund, Aschbrenner, Marsch and Bartels2016) and how online peer support groups provide many opportunities for both individual participants and nonprofit organizations that use online platforms to achieve their goals, it is necessary to investigate its potential for vulnerable populations.

NPO Outreach via Online Platforms

Nonprofits are not left out when it comes to leveraging online platforms for their outreach. In fact, online communities have been noted to provide social support, information, and comfort to individuals who experience social marginalization (Braithwaite et al., Reference Braithwaite, Waldron and Finn1999). Consequently, nonprofits that play a crucial role in giving voice to marginalized and underrepresented communities could expand their reach by maximizing their usage of online platforms. This is especially pertinent since online platforms have emerged as dynamic spaces where individuals can connect regardless of temporal and geographical constraints (Preece, Reference Preece2001).

Virtual peer support groups offer a space where individuals can find understanding and empathy from others who share similar circumstances, enhancing a sense of belonging and social connectedness despite physical distance (Leamy et al., Reference Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams and Slade2011). To reach their target beneficiaries, nonprofit organizations are increasingly recognizing the potential of utilizing online communities to extend their outreach to target beneficiaries (Lee & Shon, Reference Lee and Shon2023; Smith, Reference Smith2018). Yet, one major area nonprofits struggle with is a lack of research on how they can better integrate online platforms and tools directly into delivering their core programs and services.

Indeed, virtual spaces on social media can provide both voice and community to marginalized groups who either cannot or choose not to operate through traditional means (Smith, Reference Smith2018). However, little scholarly attention has been given to participants in these communities and how they process their experiences. Therefore, this study seeks to investigate what the motivations and experiences of participants are for joining and engaging with online support groups facilitated by nonprofit organizations. As well as explore how social interactions and community building occur within these online support group spaces, and what meanings do members attach to these interactions?

Exploring social participation among members of online peer support groups facilitated by a nonprofit organization will contribute to the existing body of knowledge. Our approach will explore the nature of single mothers’ online support groups, examine the social interactions that take place among members, and identify the meanings attached to those interactions. Furthermore, the findings of this research might give struggling nonprofits a clue on how to better integrate online platforms for delivering their core services.

Theoretical Framework

This study examines the transformation process that occurs when participants in an online peer group interact and the impact of those changes on various aspects of their lives, including communication, self-identity, employment, and relationships. To achieve this, participant observation of group members in their virtual environment was conducted, followed by interviews based on their participation. The interview data were then interpreted using a symbolic interactionism approach.

In his theory of collective behavior, Blumer (Reference Blumer1971, p. 70) distinguished between symbolic interaction in routine social life and circular reaction in collective behavior. Circular reaction refers to a form of reciprocal stimulation in which an individual's response reproduces the stimulation received from another individual, and this response, when reflected in the original individual, reinforces the initial stimulation. This process involves individuals mirroring each other's emotional states and intensifying these emotions. Members of a peer group are often influenced by the actions of their peers, especially if their circumstances are similar. Thus, this pertinent question arises: Can the transformations that take place among members of a peer support group be understood and explained in the light of Blumer’s collective behavior?

This study is grounded in the theoretical frameworks of symbolic interactionism and collective behavior. As articulated by Blumer (Reference Blumer1969a, Reference Blumer1969b), symbolic interactionism emphasizes the empirical nature of human group life and behavior, acknowledging the significance of meanings in social interactions. Three fundamental principles emerge from this theory.

The first premise is that human beings act toward things on the basis of the meanings that the things have for them. Such things include everything that the human being may note in his world—physical objects, such as trees or chairs; other human beings, such as a mother or a store clerk; categories of human beings, such as friends or enemies; institutions, such as a school or a government; guiding ideals, such as individual independence or honesty; activities of others, such as their commands or requests; and such situations as an individual encounters in his daily life. The second premise is that the meaning of such things is derived from, or arises out of, the social interaction that one has with one's fellows. The third premise is that these meanings are handled in, and modified through, an interpretative process used by the person in dealing with the things he encounters. (Blumer, Reference Blumer1969a, Reference Blumer1969b, p. 2)

Firstly, individuals’ actions toward objects are influenced by the meanings those objects hold for them. Let’s term this principle “shared meaning". Secondly, the meanings attached to objects are shaped through social interactions with others; we call this “meaningful interaction". Lastly, these meanings undergo a process of interpretation and modification as individuals engage with the objects they encounter; this principle can be termed “interpretation and modification". Essentially, for Blumer, social life is seen as an ongoing process of defining and redefining situations rather than following fixed patterns.

Human groups or societies are fundamentally characterized by actions and should be understood from that perspective. In essence, human societies comprise individuals actively engaging in various actions. These active human engagements are not restricted to physical face-to-face actions; they extend to online actions. Blumer's perspective emphasizes the active role of individuals in creating social reality through their interactions and interpretations, viewing society as fluid and constantly negotiated rather than a fixed structure. Therefore, symbolic interactionism perspective was adopted for this research to explore and explain how meanings are negotiated in online social interactions among peers.

Case

A particular illustration of how nonprofits have been utilizing online communities for their mission is found in the operations of the Single Mothers’ Sisterhood (SMS), a nonprofit organization based in Japan. The SMS is a nonprofit organization that provides opportunities for single mothers across regions to encourage themselves by interacting with each other. Established in the spring of 2020, when COVID-19 was raging, this group has undertaken various initiatives to support single mothers who confront an array of challenges spanning social, personal, financial, and other dimensions (SMS, 2023).

SMS was selected for this study because it ran an active online support community for a well-defined group of people—single mothers. This criterion is crucial because it bridges one of the gaps identified in the literature on peer group research. In addition, researching ways in which single mothers are navigating the complexities of living in Japan will put a spotlight on the changes taking place. Consequently, exploring the dynamics of SMS will further help our understanding of virtual peer support and highlight the experiences of vulnerable populations like single mothers in Japanese society.

The single mothers’ sisterhood (SMS) provides support for single mothers in Japan. It was formed to recognize the pressing need to improve the emotional well-being and overall health of single mothers. What sets this organization apart is its exclusive online presence. Within a relatively short time, the group has successfully attracted hundreds of women from various parts of the country. In fact, the Sisterhood began in the spring of 2020 as a virtual space for single mothers to receive self-care training. Within 9 months, 176 lectures were held, with a total of 1216 participants. The community, which started as a limited-time trial during the COVID-19 pandemic, has continued after encountering a higher-than-expected need among the single mothers' community in Japan. Consequently, the organization has continued to receive support from various quarters.

Those who participate in the group’s courses come from a variety of backgrounds, including widowed, unmarried, and divorced single mothers. The self-care training sessions are held online five times a week. In addition to self-care, the sisterhood also supports single mothers by organizing digital skill bootcamps and group reflection sessions. For the purpose of this paper, seven members of the group were interviewed for about an hour each. As the main interviewer, my limited Japanese language proficiency necessitated an interpreter. All the interview sessions were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed based on the principles of content analysis.

Method

Data collection for this study commenced with participation in SMS' Facebook group chat with the author as a participant observer. Following this, the author volunteered as an intern during the preparation phase for the 2022 Mother's Day Campaign. Weekly online meetings were held for approximately 3 months, creating a strong rapport with participants prior to interview sessions. Shared experiences of motherhood facilitated relatability with participants' daily challenges in parenting, self-care, and time management. Despite being geographically dispersed across Japan, participants’ experiences appeared strikingly similar.

This study utilizes semi-structured interviews, the primary method for collecting data in qualitative research. The interviews adopted for this study were designed similarly to what Patton (Reference Patton2014) described as an informal conversational interview. With the interviews pre-scheduled, each participant was asked the same set of questions, supplemented with appropriate follow-up questions as needed. In recruiting participants, a purposive sampling approach was employed, selecting individuals based on predetermined criteria. These criteria include prior experience as a single parent, active participation in an online community, and a willingness to participate in the study. Consequently, all the interviewees were Japanese nationals and single mothers at the time of the interview, which took place between October 2022 and October 2023. Five of the participants had two children, while two had one each. To accommodate their schedule, the interviews were held online. The use of interviews enabled us to gain a comprehensive and profound understanding of the participants’ experiences. This approach allows them to express their thoughts and emotions in a more nuanced and personal manner, thereby providing us with a wealth of valuable insights.

The interview questions were formulated as open-ended to capture the participants’ unbiased answers. After which, the interview data were analyzed in accordance with the grounded theory framework that Strauss and Corbin (Reference Corbin and Strauss2015) developed. This systematic content analysis approach involves analyzing and interpreting messages and meanings contained in texts by identifying and coding recurring keywords and themes in the data and examining their relationships to each other. The themes that emerge from the data are then used to answer the research questions and build a comprehensive understanding of social identity among Japanese single mothers. The goal of using content analysis for this study is to identify patterns, themes, or biases in the content and draw inferences about the attitudes, opinions, or beliefs of the participants.

The results of this study will contribute to the field of social identity theory by adding to the limited existing research on single motherhood and its impact on social identity. Specifically, the study will provide insight into the experiences of Japanese single mothers, adding a cultural and societal context to the larger body of research on single motherhood and social identity. Additionally, the study will contribute to our understanding of the challenges faced by single mothers in constructing a positive self-concept, particularly in the context of a culture that values traditional family structures.

Analysis

To analyze the interview data, Strauss and Corbin’s (Reference Corbin and Strauss2015) systematic approach was employed. They developed a systematic approach for analyzing qualitative interview data through grounded theory methodology. Three main coding techniques are used in their approach: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. Their systematic techniques were adopted for this research because they provide a structured way to build theory from qualitative data while still allowing flexibility.

Open coding is the initial step of breaking down the data into smaller parts to identify concepts and categories. The researcher goes through the transcripts line-by-line, assigning codes that capture the meaning or essence of each segment of text. These codes can be descriptive, representing the basic topics being discussed, or more conceptual, identifying processes, actions, or meanings expressed by participants.

To do axial coding, the codes generated during open coding are reassembled and linked together based on their properties and dimensions. The aim is to identify relationships between categories and subcategories. Strauss and Corbin proposed using a ‘coding paradigm' involving conditions, context, actions/interactions, and consequences to systematically relate categories to their subcategories.

Selective coding is the final stage, where the core category that represents the central phenomenon is identified. The researcher then systematically relates all other categories to the core category, validating the relationships and filling in any gaps. The result is a theoretical model or narrative that explains the process or phenomenon being studied.

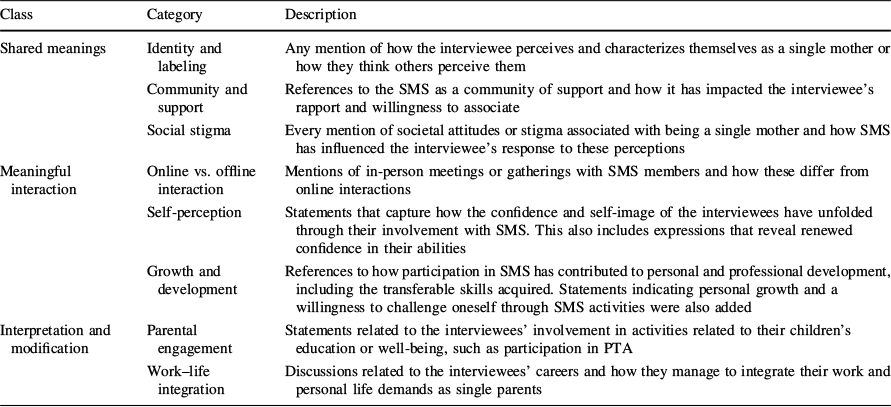

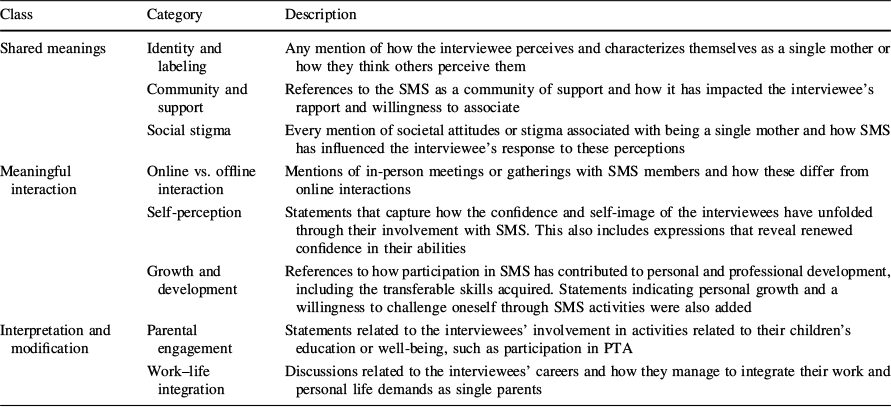

As earlier stated, this research adopted the aforementioned approach to analyze the interview data collected. After reading over the transcripts of the interviews, common and recurrent themes were found and given open codes. The following is a list of the final core categories that emerged from the axial coding analysis of the first round of open coding, along with a description of each (Table 1).

Table 1 Table showing an interactionist analysis of the interview data

Class |

Category |

Description |

|---|---|---|

Shared meanings |

Identity and labeling |

Any mention of how the interviewee perceives and characterizes themselves as a single mother or how they think others perceive them |

Community and support |

References to the SMS as a community of support and how it has impacted the interviewee's rapport and willingness to associate |

|

Social stigma |

Every mention of societal attitudes or stigma associated with being a single mother and how SMS has influenced the interviewee's response to these perceptions |

|

Meaningful interaction |

Online vs. offline interaction |

Mentions of in-person meetings or gatherings with SMS members and how these differ from online interactions |

Self-perception |

Statements that capture how the confidence and self-image of the interviewees have unfolded through their involvement with SMS. This also includes expressions that reveal renewed confidence in their abilities |

|

Growth and development |

References to how participation in SMS has contributed to personal and professional development, including the transferable skills acquired. Statements indicating personal growth and a willingness to challenge oneself through SMS activities were also added |

|

Interpretation and modification |

Parental engagement |

Statements related to the interviewees’ involvement in activities related to their children’s education or well-being, such as participation in PTA |

Work–life integration |

Discussions related to the interviewees’ careers and how they manage to integrate their work and personal life demands as single parents |

Blumer’s idea of symbolic interactionism sheds important light on how members of the SMS community's identity and behavior are influenced by social interaction. Using this paradigm to analyze the interview transcript data, the final codes were grouped under the three main principles that are fundamental to symbolic interactionism.

Shared Meanings: This classification refers to the collective understanding and interpretation of symbols, labels, and identities of each of the participants held within the single mothers’ sisterhood (SMS) community. It captures the common meanings that participants attribute to the experience of being a single mother. This shared meaning formed the basis for a shared identity that emerged through repeated interactions. The following categories came out of the interview data and seem to be evidence of how shared meanings manifest in the community.

Identity and Labeling

Blumer's theory underscores that individuals continually shape their meaning and identity through active participation in social activities. Within the context of the SMS campaigns and initiatives, participants vividly exemplify this concept. They not only engage but also share their transformative experiences with fellow participants. Through interaction with similar individuals, the single mothers were able to give up their old identities for a new one. Here are quotes from the interviews that reflect what the participants thought before participating in SMS activities:

I never saw myself as one of them because I wasn’t sure.

I didn’t have any confidence and I did not have a good image of single parents. And so, at that point, I was thinking, ‘Forget about my life; I just need to nurture these children myself.’

Before I became a single mother, I wasn’t really interested in thinking about women going on with their lives confidently. I didn’t think that feminists were cool. But I started to learn that sometimes, just because one is a woman, things don’t go smoothly. Sometimes, women must sacrifice themselves. And I feel like, since becoming a single mother, I have started to be more sensitive about these issues.

This newfound empowerment is palpable in their enhanced self-confidence and readiness to challenge societal norms. Participants’ statements, as evidenced by those above, highlight how social interaction within the SMS community acts as a catalyst for positive behavioral changes, marking a profound shift from self-doubt to self-assurance.

In an environment like SMS that enables dynamic identity formation, the narratives of participants mirror the fluid nature of identity construction. Their accounts clearly illustrate how interactions within SMS foster personal growth and empowerment, acting as a vehicle for self-discovery and identity reconstruction. Statements like “…since becoming a single mother, I have started to be more sensitive about these issues” serve as poignant evidence of the ever-evolving nature of identity within this supportive community.

Community and Support

The community's support and shared experiences transformed their self-concept. They started to view themselves as strong, capable, and resilient single mothers, challenging the negative symbols society often attaches to their identity. This collective identity served as a source of strength and empowerment, challenging preconceived notions about single motherhood. It became a significant aspect of their self-concept, as evident in statements like, “Being a single mom doesn’t matter. We can contribute our quota to society.”

By participating in the Single Mother’s Sisterhood community, I think that my hurdle toward failure has really lowered and that was when I felt like I was able to take the first steps. And that was probably because I saw a lot of other single mothers who were not afraid to take the first steps. They gave me a lot of courage.

It was 4 years ago when I divorced, and the kids at that time were much smaller. It was my decision, but I felt sorry for raising them in a single-parent home. And I also had to move my housing, so I was thinking very negatively and feeling sorry for what was happening. I had the tendency to think negatively about everything that was happening. I felt like I was sort of tipped down and was blaming myself and things were going down and down. But with the SMS, I met people who were in a similar circumstance. Through talking with mentors and interacting with them, I felt like they were pushing my back and so now I’m thinking more positively.

Social Stigma

According to Blumer, individuals derive meaning from interactions through a process of symbolic communication. In the context of SMS, social interactions are rich in symbolic meaning. Within the SMS community, it seems that social interaction fosters the formation of a collective identity among single mothers. Participants shared their experiences of how they initially felt stigmatized or isolated due to their single-mother status. However, through interactions with fellow members, they found a shared identity that transcended societal stereotypes. Individually, they began to reinterpret the symbols associated with single motherhood.

Before, I would not have made it public that I am a single mother. There was something that restrained me in my mind. Now, I don’t say it to everyone but in conversing with some people, I can talk about the circumstances that I’m in. So, I guess I’m opening my mind to some people. I think the few months of participating in SMS have helped me to think positively.

Meaningful Interaction: This classification involves the exchange of symbols, gestures, and narratives that hold significance for the participants. It emphasizes the dynamic process of communication within the SMS community, where individuals actively engage in dialogs that contribute to shared meanings and understanding. One prominent example of the meaningful interaction that takes place within SMS happens during group reflection sessions. Participants who actively attended these sessions emphasized the significance of the interpersonal engagements that occurred in shaping their individual perspectives and shared meanings. In fact, the reflection sessions appear to serve as an agency for creating a new sense of social reality for these individuals.

The following categories are also classified as agencies of meaningful interaction:

Online/Offline Interaction

Online and offline encounters both contribute to identity formation, according to Mead's theory. SMS primarily operates in an online space, but it occasionally organizes offline gatherings. Participants' reflections on these gatherings highlighted the unique dynamics of face-to-face interaction. They described a sense of familiarity and camaraderie when meeting fellow SMS members offline, even though they had initially connected through virtual channels. This finding underscores Mead's idea that identity evolves through both online and offline interactions, with each medium contributing distinct dimensions to one's self-concept (1934: 140).

It also highlights the role of context in shaping the depth and quality of social interaction, with implications for identity and behavioral outcomes. The experiences of these people appear to be in line with Blumer’s acknowledgement that the context in which interaction occurs is critical to understanding its impact. Statements such as the one below are examples.

In both cases, it wasn’t emotional to meet offline. It was just like meeting online… It didn’t feel like we were meeting for the first time.

Although meeting them offline felt like a continuation of our online meeting, I do want to see them again offline and I wonder why.

Worthy of note is the awkward feeling that some participants experienced when they eventually met other participants for the first time in person after exchanging personal, intimate information in their virtual meeting. The good thing, however, is that the awkwardness is quickly replaced by the shared understanding and support they all experienced.

Self-Perception

The interview data suggest that the influence of SMS extends beyond the boundaries of the community. Participants discussed how their experiences within SMS empowered them to challenge societal perceptions of single motherhood in their external environments. This influence on their behavior aligns with Mead's concept of the "generalized other," wherein individuals incorporate the perspectives and expectations of society (Mead, Reference Mead1934). SMS interactions reshape participants' behavior and enable them to advocate for themselves and other single mothers in a broader society.

What differentiates the category tagged “identity and labeling” from “self-perception” is that the former captures both the participants’ self-identification and societal labeling before participating in SMS activities, while the latter captures the transformed self-identity and image that occurred during their interaction in SMS. Here are quotes from the interviews that capture how the participants self-image evolved through associating with SMS:

Before I started to know the people from the Single Mothers Sisterhood, I used to feel ashamed being a single mom. I tried not to tell people if it was not necessary. I didn’t really hide but I wasn’t open about it because I was ashamed of being a single mom. I didn’t feel comfortable being a single mom.

In response to the question, “Has anything changed in the way you see yourself since joining the Single Mother’s Sisterhood community?” Here’s what some of the participants said:

Yes! Being a single mom doesn’t matter. We can contribute our quota to society. I felt like being a single mom didn’t stop me from doing anything. I felt something strong growing within me. It’s a big change!

And now that I feel like I have to do it because there are many single moms in society, I feel like I have to show those people that single moms can do things like that. I told myself that for me to join the Parent Teachers Association (PTA), it was to show the community that single moms can do it. I think it’s important.

In my book club, there are a lot of members who are taking up positions in their PTA groups as well. They say that they want to show others that even single parents can do this.

Their accounts clearly illustrate how interactions within SMS foster personal growth and empowerment, acting as a vehicle for self-discovery and identity reconstruction. Statements like “I felt something strong growing within me” serve as poignant evidence of the ever-evolving nature of identity within this supportive community. Beyond the evolving self-image, we also notice the desire to change the narrative of what single mothers can or cannot do in society. This is hinted at in the interviewee’s response regarding her role in her child’s PTA committee.

Growth and Development

Before participating in the money literacy sessions, my kids and I didn’t really think about money. At the session, we learned the importance of thinking about money. Now, my kids and I are very aware of money.

Interpretation and Modification: This class encompasses the dynamic process of interpreting shared meanings and modifying them based on evolving experiences and interactions. It acknowledges that meanings are not fixed but subjected to reinterpretation and adaptation as individuals engage with the SMS community. Participants interpret and adapt shared meanings based on new insights, changing life circumstances, and evolving perspectives, reflecting the fluid nature of symbolic interactionism.

Work–Life Integration

Some of the participants reported that they are better able to cope with the demands of work and their personal lives because of the tips they picked up while interacting with fellow single mothers within the SMS community. An example is seen in the individual who incorporated stretches into her daily routine because someone else in the group had talked about how it helped them relax. This instance and many more like it emphasize the fluid nature of perspectives.

I work full time and still run my home lessons. It’s been crazy but I felt like I should be a part of the campaign. So, I decided to join the second campaign. I found out that every time I work on a goal with people from SMS, I gain something. I wouldn’t say it’s a sacrifice but an investment.

This quote from one of the interviewees also highlights the significance of interaction with peers in facilitating a shift in perspectives, even if the circumstances were as challenging as single motherhood.

Parental Engagement

Single mothers’ participation in their children’s school or neighborhood activities can be quite tough for many reasons. Societal stigma and time restrictions are two of the common reasons that emerged from this research. Yet by interacting with fellow single mothers, forming a confident identity, developing new skills, and changing perspectives, they were ready to interact with fellow parents in a larger society. The interviewees, who were previously not actively involved in their children’s Parents Teachers Association (PTA), reported feeling challenged and motivated by those who were.

Statements like “In my book club, there are a lot of members who are taking up positions in their PTA groups as well. They say that they want to show others that even single parents can do this.” and “I told myself that for me to do PTA and to show the community that single moms can do it, I think it’s important” are direct expressions of how participation in SMS influenced its members.

Raymo et al. (Reference Raymo, Park, Iwasawa and Zhou2014) highlight that single mothers in Japan spend significantly less time with their children compared to married mothers, often due to long work hours and work-related stress. This suggests challenges in balancing work and parenting responsibilities. Participation in the SMS online activities seems to be quite helpful for some participants in balancing their work and parental responsibilities and they are happy about the changes.

Conclusion and Discussion: Implications of Findings for Literature

One of the key contributions of this study is the examination of social participation from a symbolic interactionism perspective. Adopting a symbolic interactionism perspective has helped to investigate single mothers’ participation in a nonprofit organization’s online peer support group in view of their individual emotions, identities, perceptions, and commitment. Moving beyond conventional analysis of online communities, this study introduces a nuanced understanding of the dynamics at play within the single mother sisterhood peer support group. It adds a layer of understanding about how symbols and identities intersect in an online space, especially within a community formed around a shared experience.

While most studies on mothers' online group participation identify support, information exchange, accessibility, and self-disclosure as potential benefits (Yamashita et al., Reference Yamashita, Isumi and Fujiwara2022), this study's findings are more distinct and transformational. Japanese single mothers' struggles extend beyond parenting doubts to include shame, poverty, poor self-identity, and isolation. The identity transformation resulting from interactions with fellow single mothers is a major highlight of this study. All the participants initially held negative self-perceptions and identities as single mothers prior to joining the SMS community; however, continued interactions with fellow single mothers led to a transformation in their perception and identity. By contrast, research on married mothers’ identity transformation tends to focus more on the transition to motherhood in general (matrescence) rather than overcoming stigma (Shirahase & Raymo Reference Shirahase and Raymo2014; Yamashita et al., Reference Yamashita, Isumi and Fujiwara2022).

For married mothers, while changes in identity are noted, they are often framed more in terms of adjusting to new roles rather than fundamentally reshaping self-perception (Yamashita et al., Reference Yamashita, Isumi and Fujiwara2022). The findings of this study suggest a more direct link between identity change and behavioral changes for the single mothers interviewed.

Studies on married mothers' online groups tend to focus more on benefits like reduced depression or increased marital satisfaction without explicitly linking these to identity transformation (Pai, Reference Pai2023). The identity transformation for single mothers is contextualized within broader struggles such as handling shame, poverty, poor self-identity, and isolation. Whereas, for married mothers, identity changes are often discussed in the context of general parenting challenges rather than these additional socioeconomic and emotional factors (Gattoni, Reference Gattoni2013).

This study of a Japanese nonprofit organization's online peer support group for single mothers provides valuable insights into an under-researched population. Motivations for joining the group include curiosity, a Listserv subscription, free membership, and following the organization on social media, expanding on findings by Hudson et al. (Reference Hudson, Campbell-Grossman, Keating-Lefler, Carraher, Gehle and Heusinkvelt2009). Notably, all interviewed participants initially held negative self-perceptions as single mothers. However, interactions within the online community led to transformed perceptions and identities, aligning with existing literature (Hällgren & Björk, Reference Hällgren and Björk2022; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Kumar and Hu2021).

Studying virtual communities facilitated by nonprofit organizations demonstrates how they can enhance their advocacy role through online peer support groups. This research shows that nonprofits can challenge stereotypes and misconceptions by amplifying personal narratives. By humanizing complex social issues and promoting empathy among the public and decision-makers, nonprofits can effectively drive desired social change.

The implications of these research findings for the literature are substantial, adding depth and nuance to our understanding of online communities and social interactions. By providing real-world insights into the dynamic processes of shared meaning, meaningful interactions, and interpretation within an online community, this study contributes to the field of symbolic interactionism. This understanding enriches the theoretical foundation of symbolic interactionism, demonstrating its applicability in contemporary digital spaces. Nonprofit organizations need to acknowledge the potential of online peer support groups, not only as virtual spaces but as catalysts for personal growth and collective empowerment.

Since this study focused on the single mothers sisterhood’s community, the findings may not hold for all online communities. All the individuals interviewed for this research were actively engaged in the SMS community, and this could have introduced potential self-selection bias. Future research could employ a more diverse participant recruitment strategy to ensure a broader representation of perspectives.

Furthermore, this research focused on experiences within the Japanese cultural context. Future studies might explore cross-cultural variations in shared meanings and interactions within online communities to uncover potential cultural influences. In addition, future research may investigate the nature of support that single mothers who participate in an online support group receive. Also, highlighting the factors or group features that predispose an online peer support group as one where members can receive an opportunity for personal development is a good direction to consider. Studies examining a larger dataset would also be expected to give more insight.

Acknowledgements

The remarkable assistance of my supervisor, Aya Okada,Ph.D., was indispensable to the completion of this study and its supporting research. From my first idea to the final draft of this paper, her passion, expertise, and meticulous attention to detail have inspired me and kept me on task. Throughout this research, I am thankful to Prof. Tokugawa Naohito, head of the Social Structure and Change Laboratory, for sharing his pearls of wisdom with me. The queries and remarks from my Tohoku University NPO study group colleagues were also beneficial in enhancing my data analysis. I am really grateful that Mako Yoshioka and the women of the Single Mothers Sisterhood allowed me to interview them.

Funding

The author’s research was funded by the Tohoku University Pioneering Doctoral Fellowship (Pioneering Research Support Project).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

I declare that there were no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.