Ceramic smoking pipes are among the most commonly preserved items of material culture on Iroquoian archaeological sites dating from AD 1350 to 1650 in present-day New York, Ontario, and Québec. The consumption of tobacco (primarily Nicotiana rustica [Winter Reference Winter and Joseph2000]) was a widespread practice among Indigenous peoples in the late precolonial and colonial Northeast. Ethnohistoric and archaeological records locate pipe smoking in a wide range of social and political contexts (Ferland Reference Ferland2007; Hall Reference Hall1997; Hayes Reference Hayes1992; Rafferty and Mann Reference Rafferty and Mann2004). Here, we approach smoking pipes as both assemblages of artifacts that reflect the local behavioral contexts in which they were enmeshed and as relational assemblages at the regional scale that speak to the emergent and declining interconnections between and among those people who made, carried, traded, and smoked them.

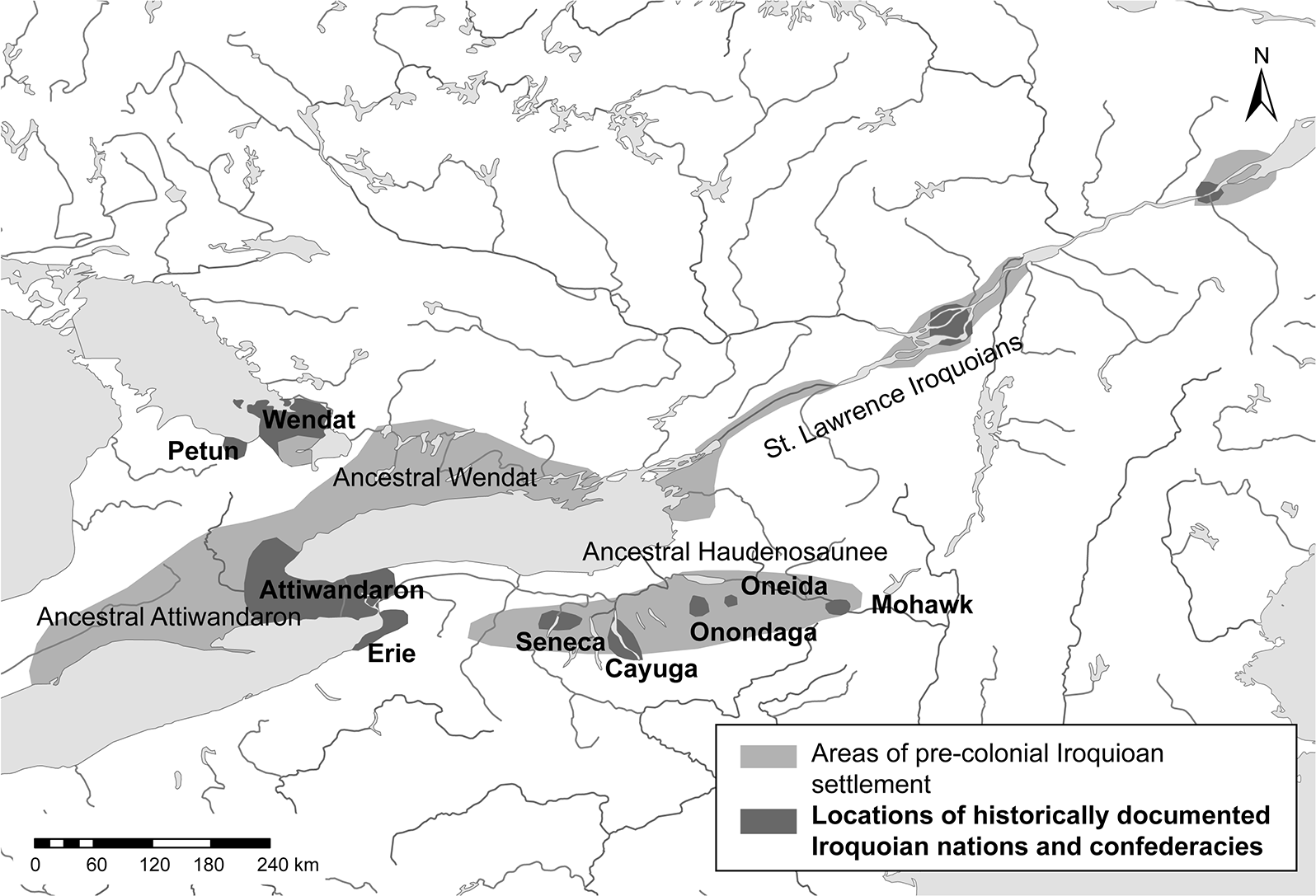

Analysis of patterns in the manufacture and formal qualities of pipes can provide information about patterns of social behavior. We are particularly interested in what formal network analysis of pipe attributes reveals in the context of politogenesis and population movement during the AD 1350–1650 period in southern Ontario. This region was home to the historical Huron-Wendat Confederacy and populations that were ancestral and connected to it (Figure 1). The latter part of this period, circa AD 1500–1650, is of particular interest on account of (1) the coalescence and relocation of communities and nations, (2) increases in violent conflict, and (3) the crystallization of the Huron-Wendat Confederacy as a formalized political institution.

Figure 1. Territories associated with ancestral and historic Northern Iroquoian populations in northeastern North America. Map by Jennifer Birch.

Previous work by the authors has focused on network analyses of Northern Iroquoian pottery collar decoration (Birch and Hart Reference Birch and John P.2018, Reference Birch and John P.2021; Hart Reference Hart2012, Reference Curtis and Birch2020; Hart and Engelbrecht Reference Hart and Engelbrecht2012, Reference Hart, Birch and Gates St-Pierre2017; Hart et al. Reference Hart, Shafie, Birch, Dermarkar and Williamson2016, Reference Hart, Birch and Gates St-Pierre2017, Reference Hart, Birch and Gates St-Pierre2023). The primary contributions of this work rely on a theoretical framework whereby collar decoration is understood to have been a means by which women signaled their social and political affiliations, with decorative motif choices being shared among members of both tightly knit and widespread social and political networks. In the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions, the manufacture and circulation of ceramic pipes have been shown to be more heterogeneous than that of ceramic vessels (Bollwerk Reference Bollwerk, Bollwerk and Tushingham2016; Braun Reference Braun2015; Creese Reference Creese, Bollwerk and Tushingham2016; Smith Reference Smith and Hayes1992). For this reason, it makes good sense to compare network topologies and other measures of network cohesion for assemblages of both artifact categories to capture and compare the sets of relations that each represents.

The primary objective of this study is to reconstruct the social networks in which ceramic pipes were used within the region the Huron-Wendat occupied and to trace changes in those networks over time. The second objective is to compare the structure and modifications of the pipe networks with those of the ceramic vessels produced by the Huron-Wendat and their ancestors. These two categories of objects were used in different contexts, for different tasks, and by people with different social and political identities. Did the signals conveyed by these two forms of material culture—representing different social and material domains in which they were manufactured, used, and deposited—result in similar network topologies? How do changes in the form and structure of those networks map onto (or not) processes such as community coalescence, intergroup conflicts, and the emergence of alliances and political confederations? To address these questions, we use network analyses of similarity matrixes generated from site-level counts of pottery collar decoration and pipe-bowl-form categories. We initiate our analyses by examining the Huron-Wendat region within the context of pan-Iroquoian networks. We then perform formal network analyses exclusively on the Huron-Wendat region, which has the largest smoking pipe dataset. We find that network topologies reflect differing social and material domains within the context of sociopolitical change over the course of three centuries.

Interpretive Models for the Study of Iroquoian Smoking Pipes

Interpretive models applied to smoking pipes have taken a variety of forms in attempts to explain pipe functions or roles in Iroquoian societies. One dominant model has focused on the role of pipes in political and diplomatic activities (e.g., Kuhn Reference Kuhn, James and Pilon2003; Kuhn and Sempowski Reference Kuhn and Sempowski2001; Wonderley and Sempowski Reference Wonderley and Sempowski2019). While it is acknowledged that pipe smoking was both a widespread practice and an inherently individual activity, it was synonymous with political and diplomatic protocols as well as the promotion of the psychological qualities that rendered a person an effective participant in those settings (Hough Reference Hough1861:53, 102, 106; Thwaites Reference Thwaites1896–1901:58:187–189; Wonderley and Sempowski Reference Wonderley and Sempowski2019:98). According to ethnohistoric observers such as the Jesuit priest Paul Le Jeune (Thwaites Reference Thwaites1896–1901:10:219, 15:27), pipe smoking was a mandatory element of council meetings. Among the nineteenth-century Haudenosaunee, to meet and discuss political matters was “to bring our pipes together” (Hough Reference Hough1861:102, 106).

Other frameworks emphasize ritual and shamanistic contexts (e.g., Hall Reference Hall1997; Mathews Reference Mathews1976; von Gernet Reference von Gernet, Alexander and Hayes III1992; von Gernet and Timmins Reference von Gernet, Alexander, Timmins and Hodder1987), including the potency of tobacco as an aid in achieving altered and affective states. Of course, the symbolic and cosmological significance of pipe smoking (e.g., Mann Reference Mann, Rafferty and Mann2004; Rafferty Reference Rafferty, Bollwerk and Tushingham2016; Wonderley Reference Wonderley2005) means that it could also be regarded as an aid to commensal politics. According to seventeenth-century AD Jesuit missionaries: “The Indians never spoke of business nor came to any conclusion without having a pipe in their mouths; they said the smoke went to their brains and gave them enlightenment on their difficulties” (Tooker Reference Tooker1964:50, citing Thwaites Reference Thwaites1896–1901: 10:219, 15:27). Although archaeologists interested in political and ritual functions in Iroquoian societies have utilized analyses of elements and assemblages of smoking pipes to those ends, it has also been recognized that according to ethnohistoric texts, pipe smoking was virtually ubiquitous in both individual and more formal group settings, as well as politicized and mundane contexts (Chapdelaine Reference Chapdelaine, Charles and Hayes1992:39; Tremblay Reference Tremblay2006:67–72; von Gernet Reference von Gernet, Alexander, Goodman, Lovejoy and Sherratt1995:69, 71).

Recent approaches combine political, ritual, and personal meanings attached to these artifacts with relational and ontological approaches, emphasizing that pipes were both vehicles for affective presence and relational identification (Cipolla Reference Cipolla2023; Creese Reference Creese, Bollwerk and Tushingham2016; Watts Reference Watts2020). Creese (Reference Creese, Bollwerk and Tushingham2016:32) argues that smoking pipes are “relational-affective objects that become extensions of the self through persistent intimacies of skilled production, habitual use, and memory work”—they are identified with their users during life and afterward. In exchanges and gifting, it is the identification of a pipe with the giver that affects the pipe’s meaning (Creese Reference Creese, Bollwerk and Tushingham2016:44).

In much archaeological research in the Eastern Woodlands, pipe smoking is interpreted, implicitly or otherwise, as a male activity (Agbe-Davies Reference Agbe-Davies2016:22; Bollwerk Reference Bollwerk, Bollwerk and Tushingham2016:52; Hall Reference Hall1997; Linton Reference Linton1924; von Gernet Reference von Gernet, Alexander, Goodman, Lovejoy and Sherratt1995). Regarding the Wendat specifically, Heidenreich (Reference Heidenreich and Bruce1978:381) writes that “tobacco growing, the manufacture of pipes, and smoking were apparently male activities (Boucher Reference Boucher and Desbarts1881:55).” With the exception of one source on the Delaware, there is no evidence that women smoked pipes in the pre–AD 1650 Eastern Woodlands (von Gernet Reference von Gernet, Alexander, Goodman, Lovejoy and Sherratt1995:69). The French explorer Jacques Cartier described pipe smoking as a male activity among the Iroquoians he met in the St. Lawrence River valley (Biggar Reference Biggar1924:184). Council meetings are also understood as men’s spaces vis-à-vis the dominant interpretive model of pipes being essential to political and diplomatic relations. It is also tempting to contrast the association of smoking with mental clarity and a state of relative peace with the socialization of Iroquoian men for fierceness and prowess on the warpath. However, we must reserve a healthy measure of doubt for the assertion that men were exclusively responsible for either pipe smoking or pipe manufacture in the interpretation of archaeological assemblages. We acknowledge that ethnohistoric observers were men and that they inhabited predominantly male social spaces, which could therefore reflect a gender bias. Jordan (Reference Jordan2014) demonstrated a close association between women’s work groups and evidence for pipe smoking at the early eighteenth-century Seneca Townley-Read site, for example. However, the evidence for pipe smoking as a gendered activity in the precolumbian world is less clear in the archaeological record of earlier centuries. Although pipe smoking is commonly associated with male political activity, ethnohistoric accounts also describe pipe smoking as something that took place in a wide range of settings: during travel by canoe (Thwaites Reference Thwaites1896–1901), in houses (Wrong Reference Wrong1939:88), and during the torture of prisoners (Thwaites Reference Thwaites1896–1901:13:53–55). Smoking pipes are also frequently recovered from a wide range of archaeological contexts, including post molds (Curtis and Birch Reference Curtis and Birch2020), semisubterranean sweat lodges (Braun Reference Braun2015), pit features (Timmins Reference Timmins1997), and midden contexts. For this reason, our preference here is to not associate pipes equivocally with any one domain of social or gendered practice but rather to look at their stylistic similarities as potential sources of information on past relational networks.

Although pipes are present in the Iroquoian archaeological record from the onset of settled village life, increases in the proportion of smoking pipes relative to ceramic vessels began in the fourteenth century AD. Archaeologists have noted increasing diversification of pipe forms and decorative elements in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century AD assemblages, coincident with coalescence of populations into large villages and towns (Creese Reference Creese, Bollwerk and Tushingham2016; Smith Reference Smith and Hayes1992). The formal and stylistic qualities of smoking pipes have been shown in some regions to be distinct from patterns associated with ceramic vessels (e.g., Smith Reference Smith and Hayes1992; Woolfrey et al. Reference Woolfrey, Chitwood and Wagner1976).

Ceramic pipe manufacture appears to have been a more heterogeneous activity than ceramic vessel manufacture. This may be an indication that communities of practice for pipe makers were differently structured, perhaps less conformist or more individualistic than communities of practice found among potters. LA-ICP-MS analysis of smoking pipes and pipe fragments from the sixteenth-century AD Keffer site in southern Ontario showed them to be more chemically diverse than pottery vessels (Creese Reference Creese, Bollwerk and Tushingham2016). Petrographic analysis of smoking pipes from the fourteenth-century AD Holly village in southern Ontario indicated that they were made by larger numbers of individuals of differing skill levels using a wider range of materials, including minerals and materials imbued with cosmological significance (Braun Reference Braun2015).

Pipes were also exchanged over long distances (Drooker Reference Drooker, Rafferty and Mann2004; Kuhn Reference Kuhn1985; Kuhn and Sempowski Reference Kuhn and Sempowski2001), a practice that also undoubtedly contributed to the diversification of pipe assemblages. More portable than pots, pipes may have been traded or exchanged as part of the gift economy or as part of interactions between individuals and representatives of groups engaged in political activities. Given the nature of the dataset being considered in this study, multiple interrelated and socially embedded variables of production, circulation/distribution, and consumption may have been at work in creating the pipe assemblages subject to analysis.

Relations and Assemblages in the Interpretation of Network Models

Our previous Iroquoian network analyses have focused on pottery collar decoration (e.g., Birch and Hart Reference Birch and John P.2018, Reference Birch and John P.2021; Hart Reference Hart2012; Hart and Engelbrecht Reference Hart and Engelbrecht2012; Hart et al. Reference Hart, Shafie, Birch, Dermarkar and Williamson2016, Reference Hart, Birch and Gates St-Pierre2017, Reference Hart, Birch and Gates St-Pierre2023). Collars are several-millimeter-thick bands of clay that encircle the rims of pots extending up to several centimeters below the lips. They provide highly visible platforms onto which were added decorative motifs consisting primarily of incised or stamped lines during the post–AD 1350 period in the Northeast. These designs were drawn from a corpus of socially mediated decorative elements and motifs. Decorated collars had high absolute and contextual visibility (Carr Reference Carr, Carr and Neitzel1995). Following Bowser (Reference Bowser2000; Bowser and Patton Reference Bowser and Patton2004), we have suggested that decorative motifs on collars were a mechanism through which women—the primary manufacturers and users of pots—signaled memberships in social and political networks (Hart and Engelbrecht Reference Hart and Engelbrecht2012).

Although pots were highly visible in longhouse and other domestic contexts, they also were viewed in larger public spaces in the context of food preparation and consumption (e.g., feasts and ceremonials). Conversely, smoking pipes were smaller, more portable, and visible in a wider range of social and political contexts. The forms of Iroquoian pots were fairly standardized, with globular bodies, restricted necks, and generally vertical rims, with or without collars (see, e.g., MacNeish Reference MacNeish1952). It was the decorations on collars that differentiated each pot and constituted signals of the maker’s/user’s sociopolitical networks (Hart and Engelbrecht Reference Hart and Engelbrecht2012; Hart et al. Reference Hart, Shafie, Birch, Dermarkar and Williamson2016). Although the pipe bowls—like pot collars—were frequently decorated with incised, stamped, and/or punctated designs, given the size of the pipe bowl, these designs were less visible at a distance than those on pottery collars. The shape of a bowl itself was more visible than its decoration. A 2.5–5.0 cm tall pipe bowl’s shape was distinguishable in public near contexts at distances of 4–8 m, based on analyses of physical space and human perception (Bowser and Patton Reference Bowser and Patton2004:177 after Hall Reference Hall1966, Reference Hall1972). Details of incised, stamped, and/or punctated decorations were visible at shorter distances, with specific attributes in only intimate (1 m) settings, such as during pipe sharing. Consequently, although bowl decorations may have conveyed information about the pipe owner, their effectiveness at conveying that information was more spatially restricted than the bowl’s form, which could be seen and interpreted at greater distances by more people. Others have noted the significance of Iroquoian bowl form in analyses (e.g., Noble Reference Noble1992:42): “for non-effigy pipes, the bowl form is often more significant than the applied designs.”

As with pottery collars and their decorations, varied bowl forms were not necessary for pipes to serve their immediate function—containing smoldering tobacco leaves or other plant material to deliver smoke to the smoker’s respiratory tract. The fact that there are varied, but limited, pipe-bowl shapes suggests they were drawn from a socially mediated corpus, and that they conveyed information about the smoker, identifying the individual as a participant in a particular social and/or political network. Knowledge and skills related to pipe manufacture and the shared cultural and practical repertoire surrounding “how to make a pipe” were transmitted among communities of practice (Wenger Reference Wenger2008). That a significantly larger mean percentage of pipe bowls is undecorated relative to pottery collars (Table 1), except in the 1550–1650 time span, further suggests that a bowl’s shape was important. In the 1550–1650 time span, effigy pipe percentages increase, whereas plain pipe-bowl percentages decrease relative to earlier times (Figure 2). Given that an effigy may carry more information than geometric or impressionistic designs, a rise in the frequency of effigy pipes may have corresponded to a rise of encoded social signals associated with change(s) in the sociopolitical relations the Huron-Wendats nurtured with their neighbors.

Figure 2. Box plots of plain (white) and effigy (gray) pipe percentages from Huron-Wendat territory.

Table 1. Mean Percentages of Plain Pipe-Bowl and Pottery Collars in Huron-Wendat Territory Assemblages by Time Span.

a Monte Carlo permutation p-value.

Following from these considerations, our approach emphasizes pipes as assemblages of artifacts and assemblages of relations. We understand pipe form as representing both individual behaviors and networks of interaction. Pipes were utilized as a media of “self-definition” (Creese Reference Creese, Bollwerk and Tushingham2016:27) by people (consciously or otherwise) as a means of relating to or identifying with larger social groups (Jones Reference Jones1997; Peeples Reference Peeples2018). Our analytical units in this analysis are pipe assemblages at the site level that might include pipes that were used in or carried to myriad contexts over their use life. Because of this, the concept of an assemblage in terms of a physical aggregation of materials deposited in the archaeological record defines the analytical units being considered (Schiffer Reference Schiffer1976).

Given that they are embedded in ordered sets of person–thing relations, networks based on the attributes of smoking pipes can be understood as forming their own relational assemblages (Knutson Reference Knutson2021; Van Oyen Reference Oyen, Astrid2016). This framework recognizes variability in the entities or practices that might be expressed in network connections (individuals, groups, things, places, etc.) and what those connections represent (the movement of objects, persons, ideas, practices or styles, access, etc.). Archaeologists are familiar with the notion that cultures are always coming into being as the result of the interplay between structure and agency (Giddens Reference Giddens1984). An approach based on networks as assemblages of relations likewise recognizes that networks are also emergent and encode social, spatial, and temporal trajectories in ways that allow us to consider the interconnected agency and relationality of network entities as a historical process (Van Oyen Reference Oyen, Astrid2016:360–361). However, we acknowledge that although network models and visualizations allow us to observe and describe relational phenomena, they do not necessarily explain them (Knutson Reference Knutson2021:798). Consequently, network models must be considered in dialogue with information from the archaeological and historical records, or Indigenous traditional knowledge.

Huron-Wendat Networks

Here, we focus on that portion of present-day southern Ontario that is associated with the Huron-Wendat confederacy in historical seventeenth-century Wendake and the region to the south, on the north shore of Lake Ontario, where ancestors of the historical Huron-Wendat lived (Figure 1). This region provides the largest sample of sites with pipe-form data and site-level chronologies that have been updated though Bayesian analyses of new radiocarbon dates on annual plant products (Birch et al. Reference Birch, Manning, Sanft and Anne Conger2021; Manning et al. Reference Manning, Birch, Conger, Dee, Griggs, Hadden and Hogg2018, Reference Manning, Birch, Anne Conger, Dee, Griggs and Hadden2019). The AD 1350–1650 archaeological record pertaining to village development, coalescence into defensive village aggregates, population movement, and the eventual formation of the Wendat Confederacy is robust and provides a strong backdrop for interpreting changes in pipe networks over time (Birch and Williamson Reference Birch and Williamson2013; Williamson Reference Williamson2014). Although we include the Haudenosaunee and St. Lawrence regions in pan-Iroquoian pipe-bowl network visualizations, the number of sites with pipe-bowl data in these regions is too small at present to warrant the separate analyses that we provide of the Huron-Wendat region. Such analyses will be conducted and presented on later occasions.

Previous analyses have shown that networks based on pottery collar decoration track Huron-Wendat history and reveal patterns not otherwise apparent in standard analyses of settlement and artifactual data (e.g., Birch and Hart Reference Birch and John P.2021; Hart et al. Reference Hart, Shafie, Birch, Dermarkar and Williamson2016). There is a consistent trend in our previous pottery collar network analyses for increased cohesion (connectedness) of the networks of the Huron-Wendat region culminating in a highly cohesive AD 1550–1650 network, when communities coalesced in Wendake and the historically documented Huron-Wendat Confederacy formed (Birch and Hart Reference Birch and John P.2018; Hart et al. Reference Hart, Shafie, Birch, Dermarkar and Williamson2016). This trend resulted from Huron-Wendat women adopting meta-identifier collar designs that signaled the mutual interests of new social configurations in the form of simple diagonal or vertical lines, which helped to integrate families and communities within the Confederacy (Birch and Hart Reference Birch and John P.2018, Reference Birch and John P.2021; Hart et al. Reference Hart, Shafie, Birch, Dermarkar and Williamson2016).

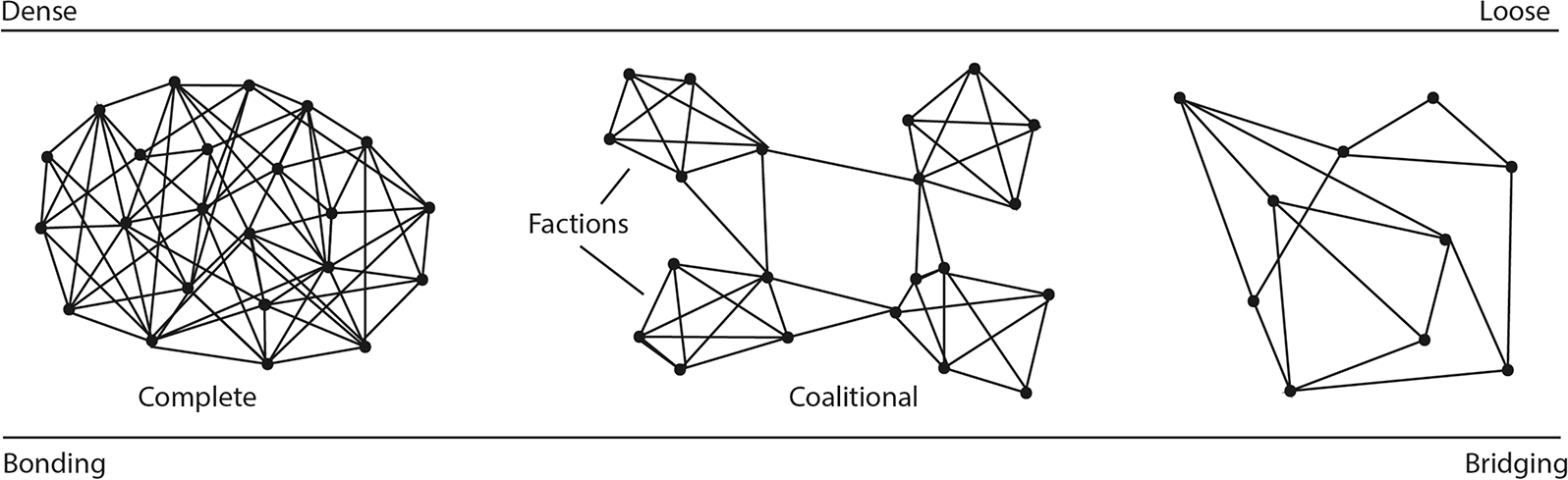

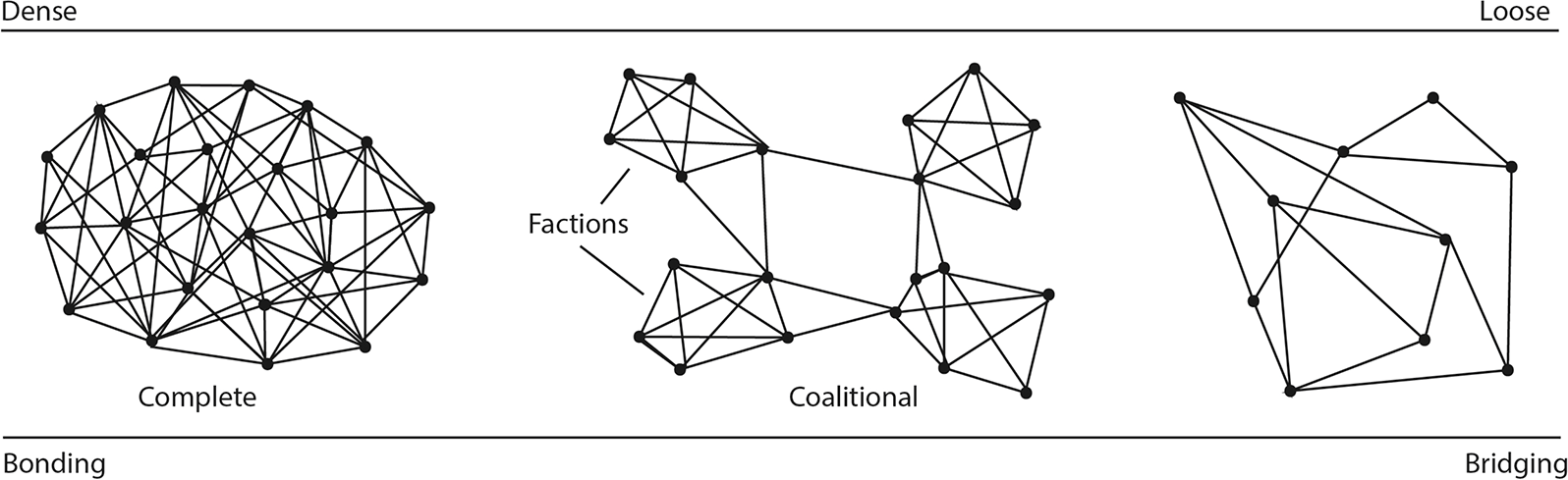

As represented in Figure 3, network topologies occur on a spectrum ranging from looser bridging networks with sparse ties between nodes to denser bonding networks in which there are many ties connecting nodes into a more complete whole. These topologies reflect differing kinds of social capital and relationships between actors—in this case village communities—that confer different kinds of economic and social benefits to network members (Crowe Reference Crowe2007; Pretty and Ward Reference Pretty and Ward2001; Putnam Reference Putnam2000; Ramirez-Sanchez and Pinkerton Reference Ramirez-Sanchez and Pinkerton2009). Dense networks are characterized by bonding ties—strong ties that accrue benefits to inwardly focused organizations reflecting reciprocity and solidarity. Loose networks are characterized by bridging ties—weaker ties that accrue benefits to externally focused individual actors reflecting information and access to external resources. Coalitional networks are hybrids, in which there are densely connected network partitions and factions characterized by bonding ties, with factions connected to other factions through bridging ties.

Figure 3. Typology of network structures (from Birch and Hart Reference Birch and John P.2018:Figure 2, after Crowe Reference Crowe2007:Figure 1; Ramirez-Sanchez and Pinkerton Reference Ramirez-Sanchez and Pinkerton2009:Figure 2).

Our previous analyses of pottery collar networks indicate that Huron-Wendat networks were complete, characterized by strong bonding ties (Birch and Hart Reference Birch and John P.2018). These reflected the power of women within the Huron-Wendat Confederacy—their active roles in forming and maintaining relationships, as well as their social and political importance in their respective communities and nations. They used pottery collar decorations to signal their memberships and facilitate cohesion within their social and political networks. The inward focus of these networks accrued social capital and associated benefits to individual women, their matrifamilies, clans, and communities.

If pipe-bowl forms performed the same symbolic meta-identifying, integrating function, then we would expect networks based on bowl forms to also become more cohesive through time and to be characterized by bonding ties. However, we also acknowledge that the topologies of pipe-bowl forms and collar decorations may differ, reflecting their varied patterns of use, identity, and visibility as reviewed above.

Methods and Materials

Pipe-bowl-form data were compiled from the literature using the standard suite of 15 categories employed in Iroquoian archaeology (e.g., Emerson Reference Emerson1954; Smith Reference Smith, Tummon and Gray1995) plus a sixteenth category for effigy pipes. Counts of pipe forms according to the 16 categories were recorded for each site (Supplemental Table 1). With respect to our previous analyses, we include Petun sites (Garrad Reference Garrad2014) with the Huron-Wendat territory sites. We include sites in Prince Edward County, at the headwaters of the St. Lawrence River in Ontario, with sites located in the St. Lawrence River valley. Pottery collar data (Supplemental Table 2) were extracted from our previously published dataset (e.g., Birch and Hart Reference Birch and John P.2018; Hart et al. Reference Hart, Birch and Gates St-Pierre2023), consisting of counts for each of 29 decorative motif analytical categories (categories 2–30) as adjusted from Engelbrecht (Reference Engelbrecht1971, Reference Engelbrecht and Lynne1996; Hart et al. Reference Hart, Birch and Gates St-Pierre2023). According to our earlier analyses, undecorated collars—Engelbrecht’s analytical category 1—were not included in the analyses. Each site was assigned to a 50-year time span, with the series beginning at AD 1350 and ending at AD 1650, based on recent Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates (e.g., Birch et al. Reference Birch, Manning, Sanft and Anne Conger2021; Manning et al. Reference Manning, Birch, Conger, Dee, Griggs, Hadden and Hogg2018, Reference Manning, Birch, Anne Conger, Dee, Griggs and Hadden2019) or estimates based on artifact-based chronologies.

Because whole pipe bowls that analysts can readily assign to form categories are often scant or absent on any given site, and the number of bowl fragments that can be confidently assigned to form categories is often small, we initially included all sites with at least 10 categorized pipe bowls/bowl fragments. We recognized it is likely the number of forms represented at any given site will increase with larger sample sizes, potentially skewing analytical results. To assess this possibility, the number of forms (richness) on the sites was sorted by number of categorized bowls from smallest to largest. The sorted form counts were then used with the runs test, as implemented in PAST 4.1.1 (Hammer et al. Reference Hammer, Harper and Paul D.2001) to determine if there are patterns (runs) greater or less than the sample mean in the sequence of values that depart from random (e.g., McKenzie et al. Reference McKenzie, Onghena, Hogenraad, Martindale and Mackinnon1999). If the number of forms increased with larger sample sizes, we expected the sequence of values to depart significantly (p ≤ 0.05) from random. If so, the test was repeated by eliminating the lowest number of bowls in the sequence. This procedure was repeated until the p-value was >0.05. Only those sites with pipe-bowl-form counts in the final iteration of the test were included in the subsequent analyses. Because the samples differed for the various analyses, the count threshold varied. Count thresholds are indicated in table captions and/or text as appropriate.

Site-level frequency counts of pipe-bowl-form and pottery-collar-decoration categories were used in PAST to calculate Morisita overlap index matrixes (Morisita Reference Morisita1959). Morisita overlap index values range from 0 (representing no similarity) to 1 (indicating complete similarity). This index is recommended in situations where there is variation in sample size and diversity between cases (e.g., Brughmans and Peeples Reference Brughmans and Peeples2023), having been shown to be largely independent of each (Morisita Reference Morisita1959; Wolda Reference Wolda1981). Following previous analyses, subsamples from the resulting matrixes were extracted for analysis based on 100-year time spans with 50-year overlaps (1350–1450, 1400–1500, 1450–1550, 1500–1600, 1550–1650). This accounted for chronological uncertainty, date estimate ranges for site occupations falling across time-span boundaries, the periodic movements of village populations from old to newly constructed villages, and population circulation among extant villages.

Network visualizations were performed in Visone 2.27.1 (Brandes and Wagner Reference Brandes, Wagner, Jünger and Mutzel2004), with weighted graphs and ties with Morisita index values <0.500 deleted, eliminating the weakest ties in the networks. We used the backbone layout option (Nocaj et al. Reference Nocaj, Ortmann and Brandes2015), an algorithm that untangles networks and identifies with heavier lines those ties with greatest influence on network structure. We performed Louvain community detection analyses in pan-Iroquoian networks as implemented in Visone, with initial clusters set to uniform and edge weight to Morisita overlap index values. This algorithm maximizes network modularity—the division of networks into clusters of nodes (Blondel et al. Reference Blondel, Guillaume, Lambiotte and Lefebvre2008; Grujić and Radivojević Reference Grujić, Radivojević, Brughmans, Barbara, Munson and Peeples2024).

Although visualizations provide qualitative means to compare networks, there are also network statistics, such as those that measure cohesion, which allow quantitative comparisons. Cohesion is a measure of network connectedness: the more connected a network (ties between nodes), the greater its cohesion (Borgatti et al. Reference Borgatti, Everett and Johnson2018). There is no single measure of cohesion. Instead, there is a suite of measures, which taken together, provide a relative assessment of network cohesion between graphs. These include the following:

(1) k-cores index: the subgraph (k) with the greatest number of nodes with a maximum degree ≥k

(2) density: the total number of ties divided by the total number of possible network ties

(3) average degree: the average number of ties between nodes and other nodes in the network

(4) average path length: the average number of edges that are needed to reach a node from another node

(5) compactness: the mean of all reciprocal distances (path lengths) in the graph

(6) diameter: the longest number of edges from one node to another

(7) clustering coefficient: the average number of closed triplets divided by the total number of triplets in each node’s ego network

Greater cohesion is reflected by larger k-core indices, density, average degree, compactness, and clustering coefficient values and lower average path length and diameter values. Cohesion measures were performed in UCINET 6.764 (Borgatti et al. Reference Borgatti, Everett and Freeman2002) on Morisita index matrixes binarized at ≥0.500 (binarization is required for many cohesion measures).

Results

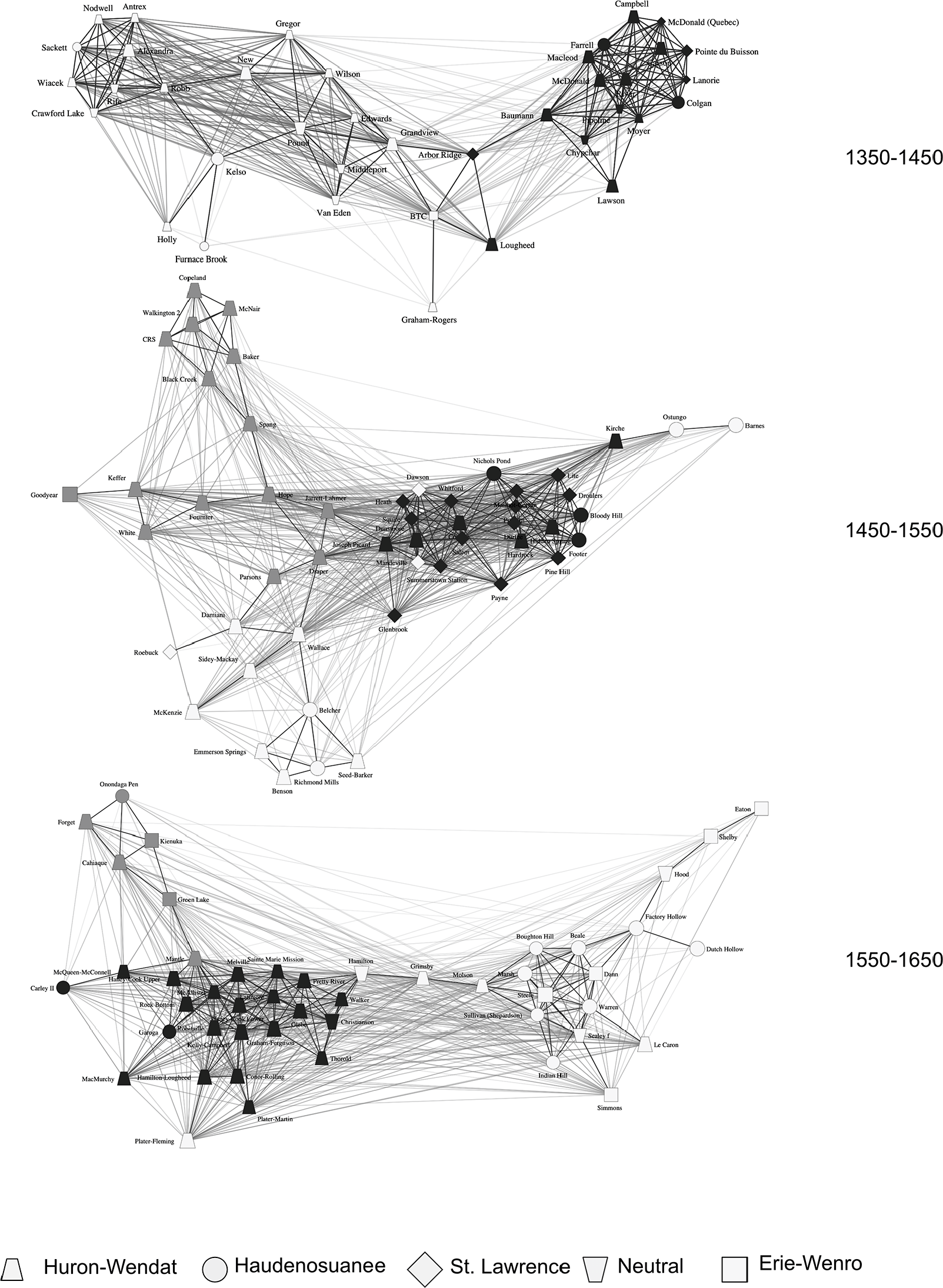

Pan-Iroquoian Networks

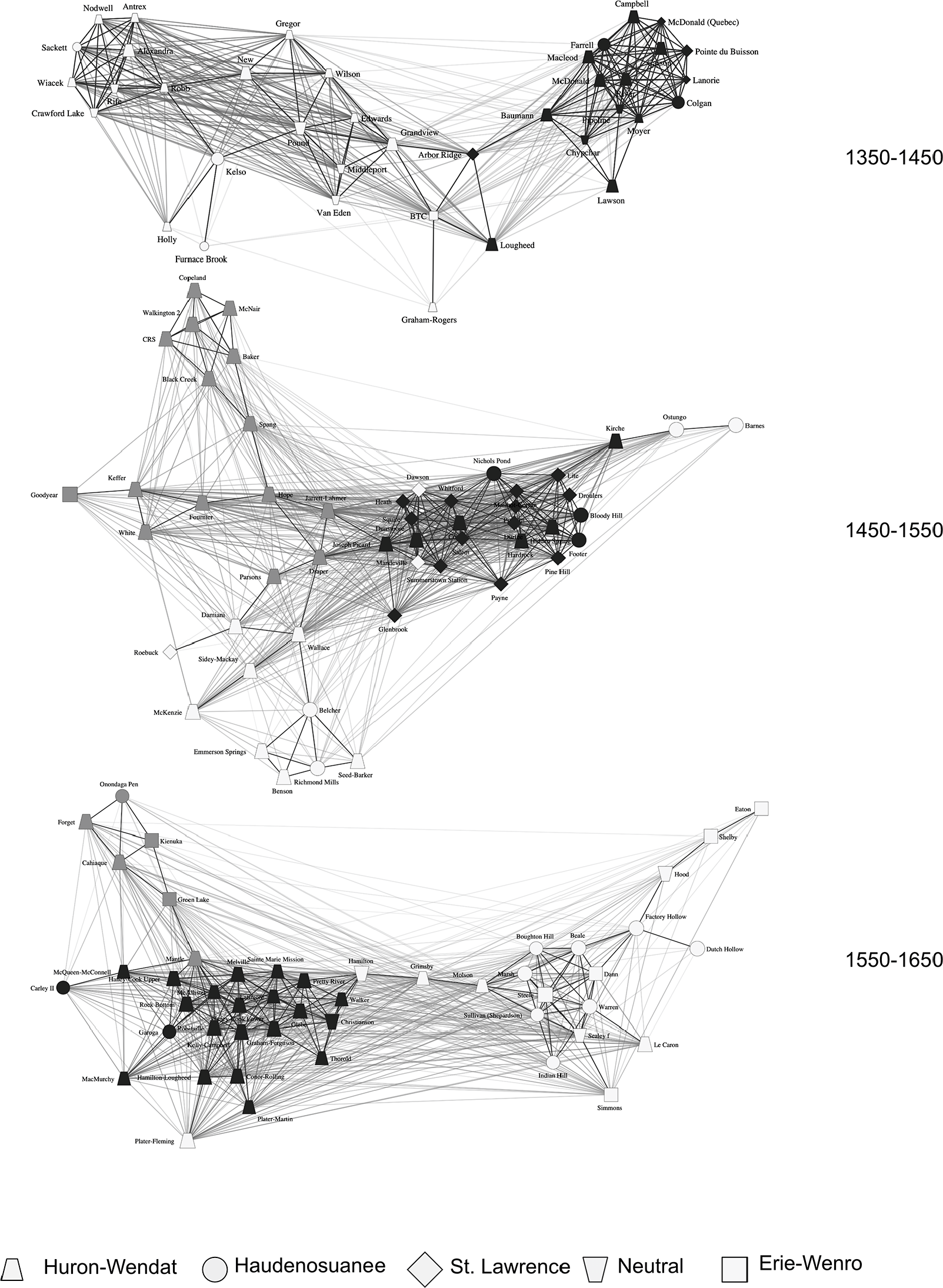

Pan-Iroquoian pipe-bowl-form networks are presented in Figure 4 for three-time spans: AD 1350–1450, 1450–1550, and 1550–1650, including sites with at least 15 categorized pipe bowls (runs test p = 0.060). Gray-scale shading is based on Louvain community detection analyses. The initial two visualizations (1350–1450 and 1450–1550) indicate that pipe-bowl forms do not partition along geographical or ethnic lines. Rather, the Louvain-detected communities contain sites from multiple regions within Northern Iroquoia, although St. Lawrence Iroquoian sites seem to be more connected with Haudenosaunee than Huron-Wendat sites. Two communities were detected in the 1350–1450 network, both of which contain sites from multiple regions. Three communities were detected in the 1450–1550 network, two of which contain sites from multiple regions, whereas the third contains all but two of the sites are from the Huron-Wendat region—which are primarily those located on the north shore of Lake Ontario. The 1550–1650 network more fully discriminates along ethnic and geographical lines, with most Huron-Wendat region sites falling within two detected communities, and most Haudenosaunee region sites falling in a third. The discrimination between Huron-Wendat and Haudenosaunee sites is not perfect, but it does suggest that the consolidation of the Huron-Wendat Confederacy in historical Wendake is at least partially reflected in pipe-bowl forms. This is consistent with pan-Iroquoian networks based on pottery collar decorations (Birch and Hart Reference Birch and John P.2018; Hart et al. Reference Hart, Birch and Gates St-Pierre2023).

Figure 4. Pan-Iroquoian pipe-bowl-form networks with ties having Morisita index values ≥0.50. Node shadings identify the Louvain community detection results.

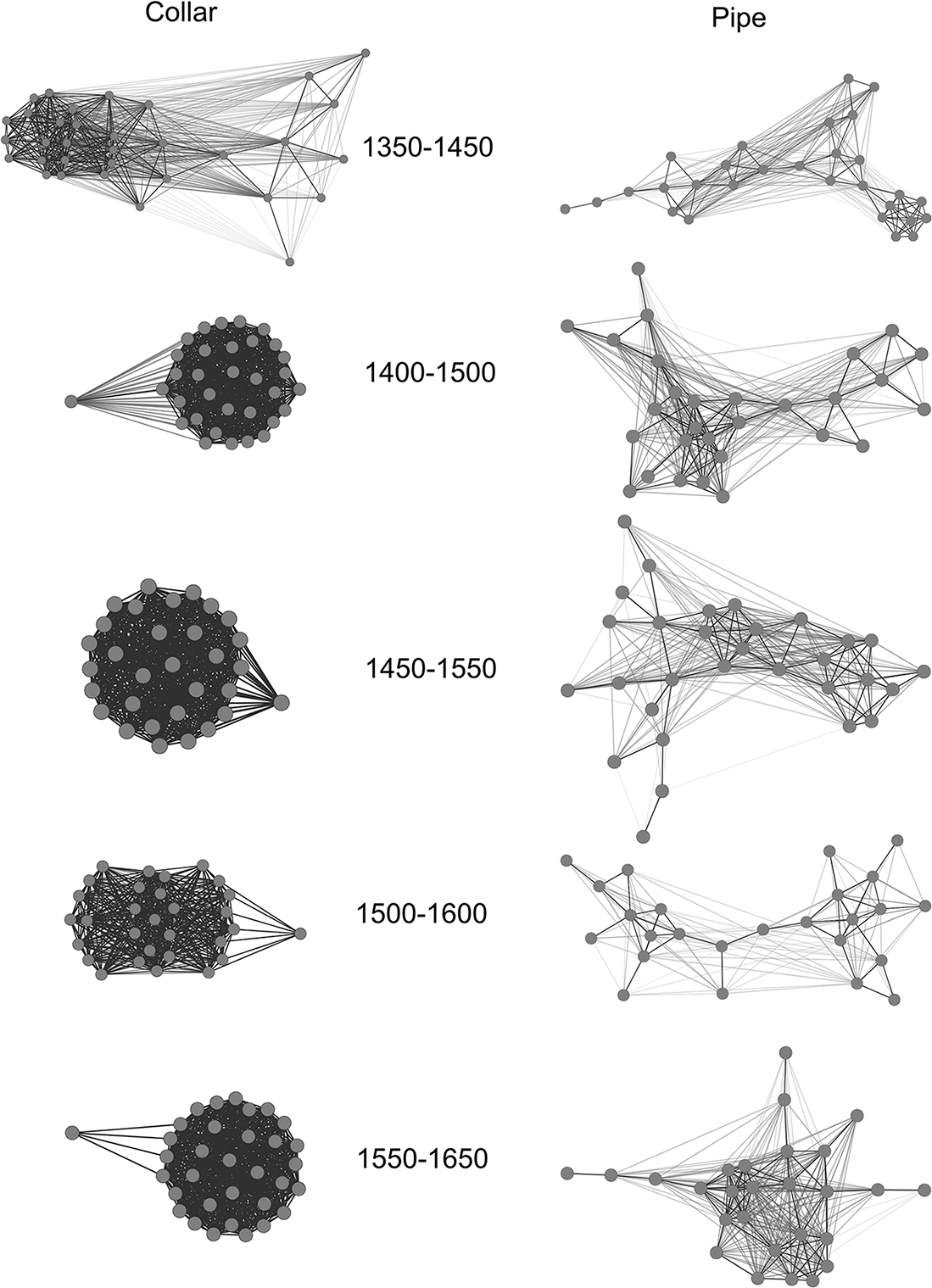

Huron-Wendat Territory Networks

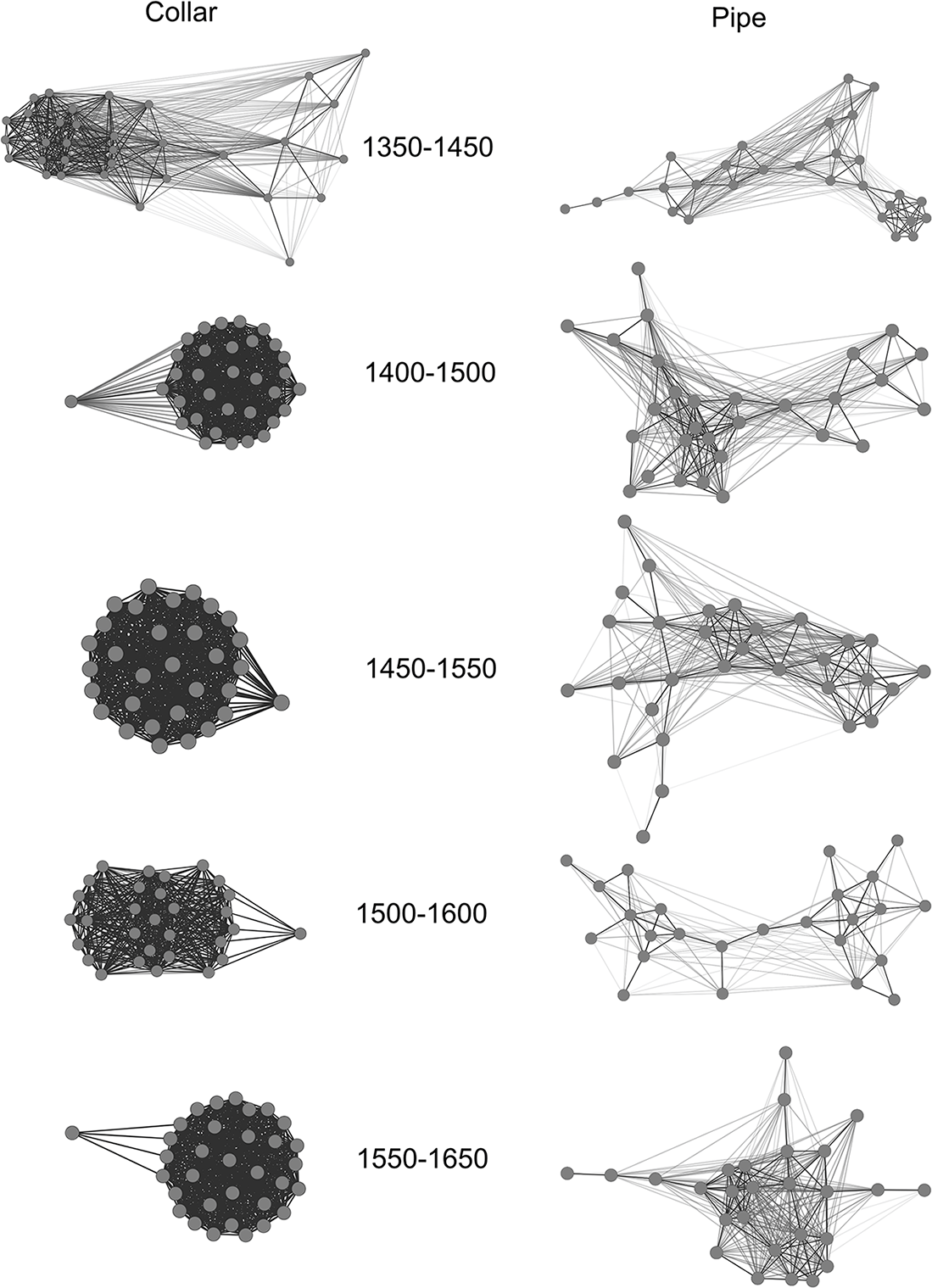

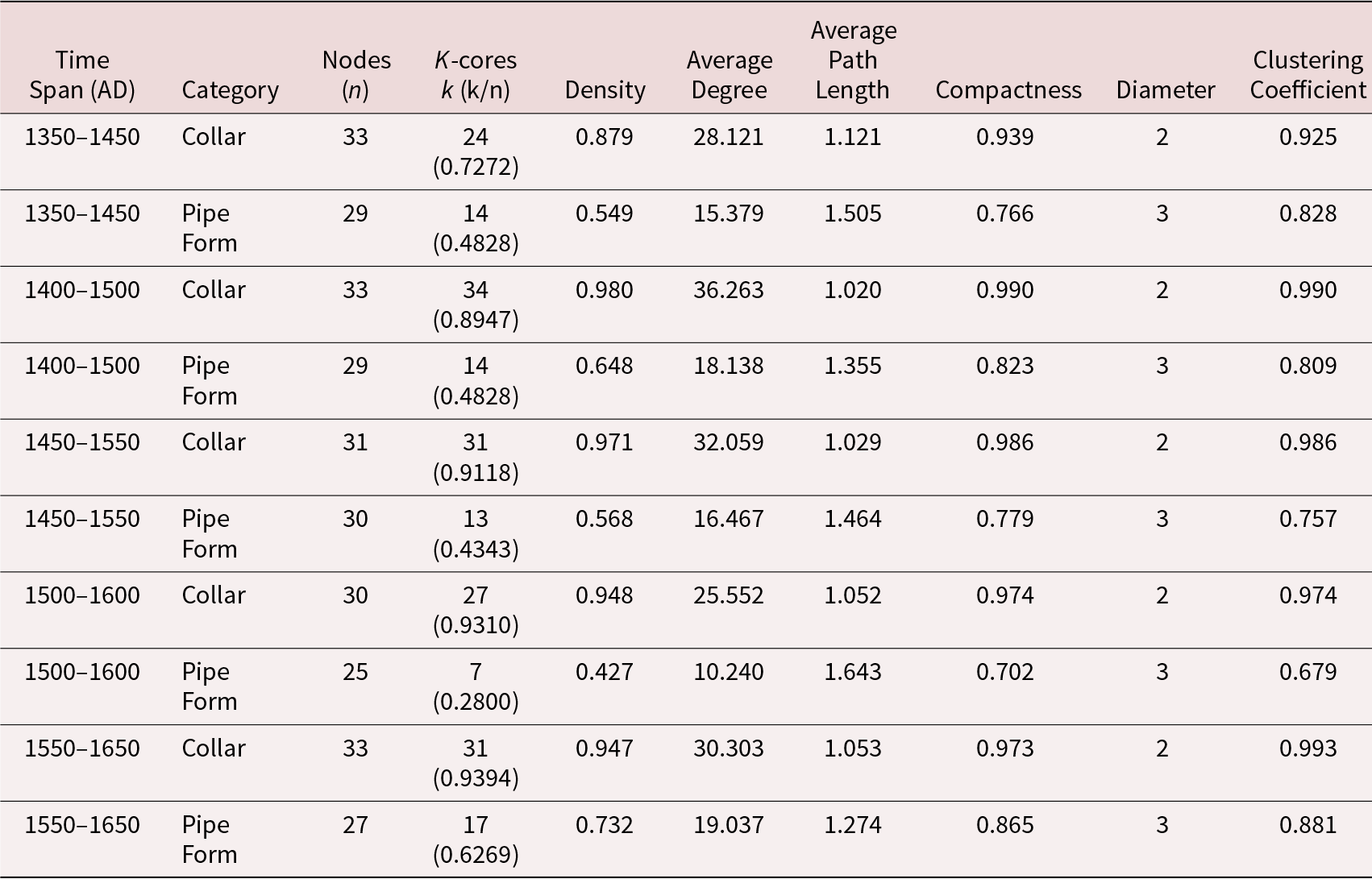

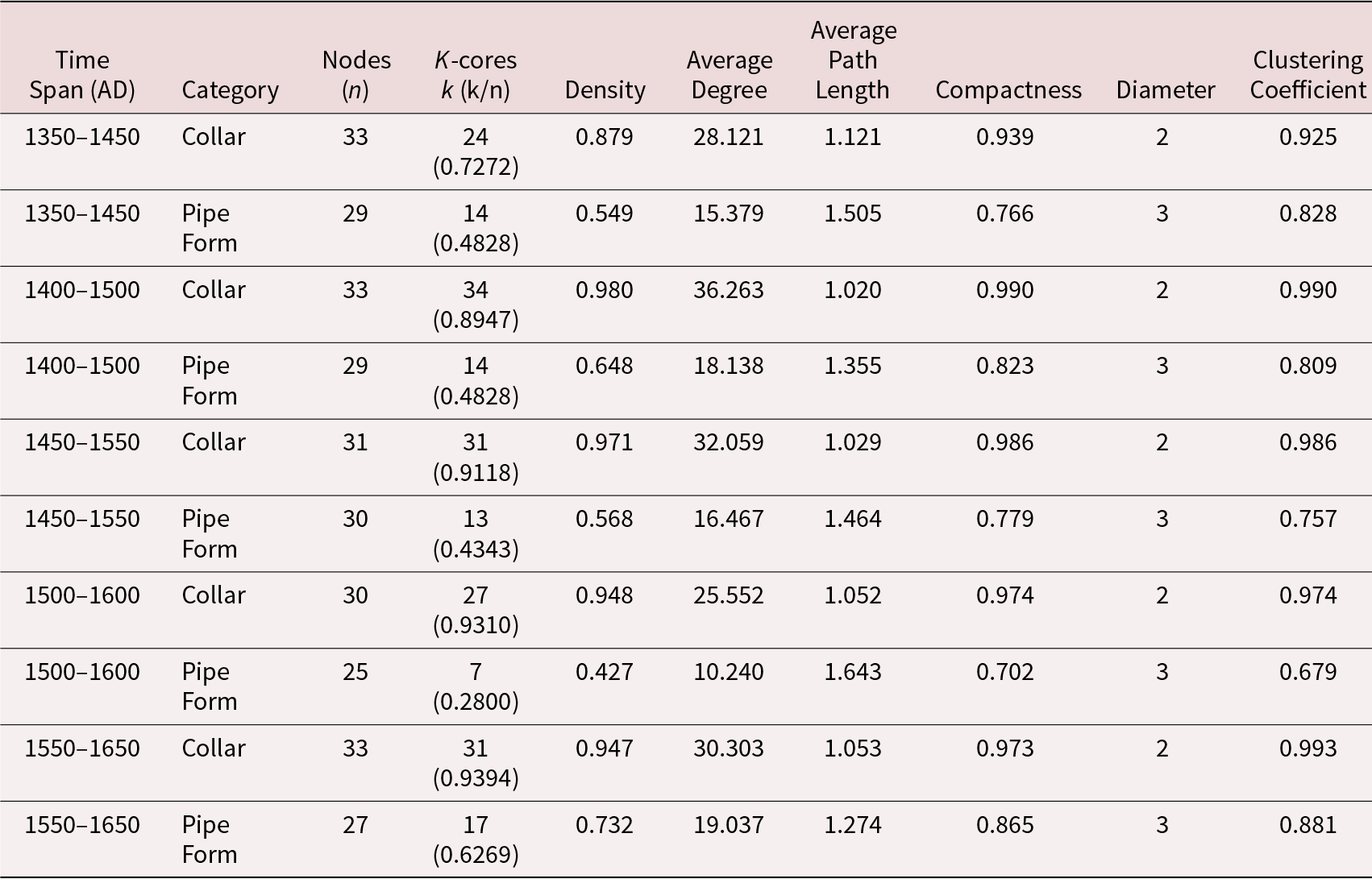

We initially compared networks based on our complete samples of Huron-Wendat territory sites with pottery collar decoration or pipe-bowl-form (accounting for runs test results) data. Each sample included sites that had only data for that artifact category and sites that had data for both. Visualizations of each 100-year time span are presented in Figure 5. Clearly, the collar-decoration networks are more cohesive than are the pipe-bowl-form networks. This is confirmed by the cohesion measures (Table 2). All measures indicate that the collar-decoration networks have greater cohesion than do the pipe-bowl-form networks.

Figure 5. Pottery collar decoration and pipe-form network backbone visualizations by 100-year time span with Morisita index values ≥0.500, including all Huron-Wendat territory sites. See Table 2 for cohesion measures.

Table 2. Network Cohesion Measures for Huron-Wendat Territory Collar-Decoration and Pipe-Form Graphs Binarized at ≥0.50 for Sites with Pipe Counts ≥10 (Runs t-test Monte Carlo p = 0.1440).

To further compare network cohesion, we reran the analyses using only those sites that have both pipe-bowl-form and collar-decoration data (Figure 6; Table 3). Network visualizations clearly demonstrate greater cohesion in the collar decoration than in the pipe-bowl-form networks. Because pairs of networks have the same sample sizes and represent the same sites, all of the measurements are directly comparable. The cohesion measurements are consistent with those from the full samples of sites; collar-decoration networks consistently have greater cohesion than do the pipe-bowl-form networks.

Figure 6. Pottery collar decoration and pipe-form network backbone visualizations by 100-year time span with Morisita index values ≥0.500, including only Huron-Wendat territory sites with pottery and pipe data. See Table 3 for cohesion measures.

Table 3. Network Cohesion Measures Binarized at ≥0.50 for Huron-Wendat Territory Sites with Both Collar-Decoration and Pipe-Form Data with Pipe Counts ≥16 (Runs Test p = 0.15938).

Because the networks for each time span contain the same sites, it would be possible to perform permutation t-tests for those measures that are based on node-level values to determine if the means of the measures are significantly different. However, the measures for most of the collar-decoration networks have no variance; they are complete networks, so t-tests are inappropriate. Therefore, to further assess the differences between the pipe-form and collar-decoration networks, we performed statistical tests for two measures on valued networks (Table 4). The first test compares densities of paired networks with both pipe-form and collar-decoration data in UCINET. This test uses a bootstrap method to compare the densities of two networks with the same nodes, analogous to a traditional paired t-test (Snijders and Borgatti Reference Snijders and Borgatti1999); p-values in this test represent the proportion of absolute differences in the bootstrap routine that are as large as the observed value. In all cases, there is a significant difference between the networks, with collar-decoration networks having greater densities than the pipe-form networks. We also did permutation t-tests in UCINET on node-level degree values for valued networks. The permutation p-values indicate significant differences between the pipe-form and collar-decoration networks, with the collar-decoration networks having larger average (mean) degrees.

Table 4. Permutation t-tests of Network Density and Node-Level Degree by 100-Year Time Span for Valued Graphs of Huron-Wendat Territory Sites with Collar-Decoration and Pipe-Form Data.

a Proportion of absolute differences as large as the observed.

To further explore network configurations, we examined k-cores, cutpoints, and blocks for networks binarized at a Morisita overlap index threshold of 0.80 for that subset of Huron-Wendat territory sites having both pottery and pipe data (Table 5). This enabled us to understand how the network structures affect configurations and social capital. As noted earlier, k-cores represent the number of nodes with a degree ≥k. The k-core index used here is the maximum-sized k-core in a network. Cut points, on the other hand, are nodes that bridge structural holes. Their removal disconnects a network at that point, resulting in two or more blocks (non-separable subgraph). Bonding ties are reflected by high k-core index values, whereas bridging ties are represented by larger numbers of cut points and blocks (Crowe Reference Crowe2007:478). It is already evident from the analysis at a Morisita overlap index threshold of 0.50 that the pottery collar networks have larger k-core indices than do the pipe-bowl-form networks. This is emphasized in the 0.80 threshold networks. In all time spans, the pipe-bowl-form networks had lower k-core indices. These are substantially lower in the last three time spans, with the pipebowl maximum k-cores representing only 12.5% to 20.0% of the nodes in the pottery-collar k-core index. Cutpoints were present in all 0.80 threshold pipe-bowl networks, the removals of which resulted in three to five blocks. No cutpoints were present in the pottery collar networks. These results indicate that unlike the complete pottery-collar networks, the Huron-Wendat pipe-bowl-form networks are coalitional, with bridging ties between factions (subgraphs).

Table 5. K-Core indices, Cutpoints, and Blocks for Pipe-Bowl-Form and Collar-Decoration Networks Binarized at a Morisita Overlap Index Threshold of 0.80 for Sites Having Both Pipe and Pottery Data from Huron-Wendat Territory Sites.

Discussion

The pipe-form networks reveal changes in intercommunity relations before, during, and after processes of coalescence and confederacy formation. In the 1350–1450 period, Louvain community detection analysis revealed three groups, each with members drawn from across the pan-Iroquoian network. One community included predominantly Huron-Wendat and St. Lawrence Iroquoian members—as well as two Haudenosaunee-territory sites in a relatively tightly bonded configuration. These sets of relations may relate to our previous suggestion that St. Lawrence Iroquoian groups (and groups of women, at that) served as “brokers” in the pan-Iroquoian networks (Hart et al. Reference Hart, Birch and Gates St-Pierre2017). Another large Louvain-detected community includes Huron-Wendat and Haudenosaunee-territory communities in a slightly looser network, although also with a tightly bonded cluster of sites consisting of members of both groups. The third—and smallest—Louvain-detected community includes sites belonging to three different ethnic groups, although all are located in western New York and the Niagara Peninsula. This suggests that in the 1350–1450 period, communities of practice and sets of relations among the makers and users of ceramic pipes transcended geographic and ethnic boundaries. At this time, the primary unit of social and political organization would have been the coresidential community (Williamson and Robertson Reference Williamson and Robertson1994), with the crystallization of nations-cum-ethnic groups likely only emerging in the later 1400s–1500s (Birch Reference Birch2015; Hart and Engelbrecht Reference Hart, Engelbrecht, Eric and John2017). Consequently, these networks likely reflect sets of relations at the intracommunity (site) level as opposed to the influence of any larger social-structural units.

In the 1450–1550 period, we expect that the following societal trends influenced pipe-form networks: (1) the onset of heightened hostilities among nascent nations and confederacies and (2) the coalescence of multiple, previously distinct communities into larger defensive aggregates. The Louvain community detection analysis for this interval detects three groups. Two of these communities are composed primarily of ancestral Huron-Wendat sites. One of these includes sites north and south of the west end of Lake Ontario and Niagara Peninsula, suggesting a potential set of network interactions in that subregion. The other group is largely composed of communities on the north shore of Lake Ontario. It is during this period (ca. 1475–1550) that a great amount of evidence for violent conflict in the region is found in the north-shore region—including population aggregation in heavily palisaded villages containing human remains bearing perimortem trauma (Williamson Reference Williamson, Richard and David2007, Reference Williamson, von Bitter and Williamson2023). The two Wendat-dominated subsets of the network graph exhibit a coalitional network structure. It may well be that the networks of relations defined in this graph reflect defensive-cum-political communities during this period of heightened tensions.

In the 1550–1650 networks, a relatively hard break is reflected in the Wendat-dominated and Haudenosaunee-dominated networks. A century of tensions between members of the Wendat and Haudenosaunee confederacies appears to have resulted in two distinct networks, connected by a small number of Attawandaron (Neutral) communities/nodes. It seems clear that processes of coalescence, conflict, and confederacy building significantly influenced network structure. The communities of practice that determined the formal qualities of pipe forms as well as the social signals encoded and transmitted in their use diverged sharply along Wendat and Haudenosaunee lines.

We now consider whether the signals conveyed by ceramic collars and pipe bowls—each representing different social and material domains in terms of how they were manufactured, used, and deposited—resulted in similar or different network topologies, including how the social networks in which they were entangled organized and evolved in similar or different ways. As noted above, only the data from the Huron-Wendat territory networks are sufficiently robust to consider this question.

When we compare the connectivity and topology of ancestral and historic Huron-Wendat territory network structures based on ceramic collar design and pipe form, notable patterns emerge that are representative of the social and spatial worlds in which the makers and users of pots and pipes operated. Networks based on ceramic design sequences are highly connected and bonded, whereas networks based on pipe form are coalitional throughout the 1350–1600 sequence. In the 1550–1650 sequence, the pipe network becomes denser and more bonded than in any of the other graphs, concurrent with the consolidation of the Huron-Wendat confederacy in historic Wendake on the peninsula between Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay in the first decades of the 1600s.

We then have to ask how these relational differences in the form and structure of pot and pipe networks might be interpreted in relation to the archaeological and historical records in terms of patterns related to manufacture, use, and deposition. This includes how changes in the form and structure of those networks do or do not map onto processes such as community coalescence, population movement, intergroup contacts and conflicts, and the emergence of political confederation. In Huron-Wendat society, the manufacture of pots was likely a more communal endeavor than the manufacture of pipes. We have previously suggested (e.g., Hart and Engelbrecht Reference Hart and Engelbrecht2012; Hart et al. Reference Hart, Shafie, Birch, Dermarkar and Williamson2016) that pottery vessels were produced by women in family groups, as was characteristic of Iroquoian female activities (see Engelbrecht Reference Engelbrecht2003; Martelle Reference Martelle2002; Perrelli Reference Perrelli, Laurie and Timothy2009). Conversely, pipe manufacture may have been something men engaged in on a more individual basis, and in more loosely structured communities of practice.

In his analysis of a sample from a large pipe assemblage of the sixteenth-century ancestral Huron-Wendat Keffer village site, Creese (Reference Creese, Bollwerk and Tushingham2016) found that there was greater variation in the physical and chemical attributes of pipes than in pottery. He suggests that “pipe production at Keffer was an open field of practice in which individuals from a cross-section of society made pipes as and when desired . . . . The many pipes at Keffer were most certainly made by many, rather than by the few” (Creese Reference Creese, Bollwerk and Tushingham2016:40). Although Creese’s analysis was confined to a single village, he suggested the following:

A diverse array of clay smoking pipes were implicated in the development of personal routines, bodily habits, dress and adornment, as well as informal and formal modes of affirming friendship, hospitality, and life-giving interdependence. These relationships were probably central to successful village life, and, in turn, help to explain the temporal coincidence of the “adaptive radiation” of Ontario Iroquoian smoking pipes with a period of widespread village nucleation and longhouse growth [Creese Reference Creese, Bollwerk and Tushingham2016:46].

The proliferation of pipe smoking among individuals originating from diverse clans and Nations and the associated cultural protocols around engagement in diplomatic and ceremonial relations requiring a state of “good mind” may have been an aid in commensal politics at both the household and community levels. Although it is tempting to associate pipe assemblages with the community-cum-village-cum-site at which they were deposited, pipes may have also been carried into a wide range of social and geographic contexts. Although Iroquoian men’s social worlds were always more distributed than women’s (Birch and Williamson Reference Birch, Williamson, Birch and Thompson2018:93–97), this would have especially been the case in the post-1550 world, where trade and warfare became a more frequent part of men’s taskscapes. The social networks that men operated in were distributed in multiple ways: (1) as ex-officio members of matrilineal, matrilocal households; and (2) as individuals and groups who operated beyond the “wood’s edge,” where male social power was exercised—as opposed to “the clearing,” the domestic realm where women’s power resided (Hamell Reference Hamell1992). Although men’s social networks may have been formed across a wide range of social, political, and geographic contexts, the pipes in our analysis were ultimately deposited in the archaeological record by residents of (and possibly visitors to) the sites from which assemblages derive.

Although networks based on ceramic collar decoration are remarkably bonded and stable throughout the 1400–1650 sequence, it seems notable that the most visible transformation in pipe-form networks occurs concurrently with the historically documented period in which the four nations of the Wendat Confederacy coalesced physically and politically. Although the origins of the confederacy purportedly lay with an alliance between the original two nations to settle in what became Simcoe County, Ontario, escalating conflict with the Haudenosaunee led ancestral Wendat populations formerly inhabiting the north shore of Lake Ontario and the Trent Valley to form a defensive alliance in the first decades of the 1600s (Birch et al. Reference Birch, Manning, Sanft and Anne Conger2021; Trigger Reference Trigger1976:156–157). Military alliances have enduring impacts on social, political, and economic relations (Kohut Reference Kohut, Hugo and Ruiz2022; Roscoe Reference Roscoe2009). Joint participation in feasts, ceremonials, council meetings, and war parties would have brought men’s activities and signaling communities into closer relational alignment—though this was an alignment that nevertheless remained more coalitional than that produced by Huron-Wendat women’s signaling networks. As in other cases where power is decentralized, widely shared, and embedded in daily social life (Bowser and Patton Reference Bowser and Patton2004), the political dimension of both women’s and men’s activities can be understood as complementary rather than contradictory (see also Alfred [Reference Alfred2009] regarding the importance of opposites and complementarity in Indigenous governance).

Conclusion

We have seen that similarity networks based on pipe-bowl forms in Huron-Wendat territory over a period of 300 years (AD 1350–1650) became more segregated from other regions in Northern Iroquoia. However, when examined separately, the networks were less cohesive than similarity networks based on pottery collar decorations. That Northern Iroquoia was a dynamic region during these three centuries would be an understatement. This is particularly true of the Huron-Wendat territory. These 300 years witnessed a consolidation of population into large, defended villages and towns; increased interregional conflicts; and the movement of Huron-Wendat villagers from the north shore of Lake Ontario and Trent Valley into the historical Wendake area south of Georgian Bay. This created a buffer zone between the Huron-Wendat and Haudenosaunee, and the formation of the Huron-Wendat Confederacy, after which they experienced the regular presence of European explorers and clergy, epidemics, famines, the fur trade, Haudenosaunee aggression, and ultimately, the dispersal of Huron-Wendat peoples to the west, east, and south.

The Huron-Wendat Confederacy was in large part a defensive mechanism, bringing populations and nations together socially, politically, and physically into a federation for mutual aid and defense concentrated in historic Wendake. As the Confederacy formed, Huron-Wendat women increasingly adopted meta-identifier decorative motifs in the form of simple diagonal or vertical lines for their pottery collars (Birch and Hart Reference Birch and John P.2018, Reference Birch and John P.2021). These motifs reflected the bonding ties characteristic of complete networks that connected together families, villages, and nations in new sociopolitical and geographical settings, and reflected women’s power in the new politics of the confederation. Women accumulated and used bonding social capital to maintain the fabric of the new confederation as an inwardly focused network of interactions.

The smoking-pipe-bowl-form similarity networks were quite different. Rather than complete, bonding networks, they consisted of factions, each with internally strong ties, with weaker bridging ties between the factions. But there is strength in weak ties (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1973). These weaker, bridging ties facilitated the spread of information and links to mutual defensive aid across disparate factions, allowing them to draw on defensive assistance (information, military aid, trading partners turned allies) from villages across Wendake and beyond. The bridging social capital maintained an integrated defensive force composed of men from different Huron-Wendat clans, communities, and nations.

We see this, then, as a reflection of the differing nature of social relationships of men and women within the structure of the Confederacy. The first was used by women to fully integrate diverse peoples into a single sociopolitical entity. The second was used primarily by men as a mechanism to affect a dispersed but connected defensive and political strategy in response to external threats that precipitated the movement and consolidation of populations and the formation of the Confederacy. It now remains to be seen if pipe-form and pottery networks differed in the same manner within and between Haudenosaunee and St. Lawrence Iroquoian communities. Detailed data on pipe-bowl decoration is limited at present. However, future efforts expanding these data may allow analyses that complement those presented in this article.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2025.1.

Supplemental Table 1: Pipe Form Counts.

Supplemental Table 2: Pottery Collar Analytical Motif Counts.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in the analyses are available in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Rachel Gruber for her assistance in compiling pipe data. Two anonymous reviewers and William Englebrecht provided helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant funding from any funding agency, or from commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.