Introduction

Smith’s bush squirrel (Paraxerus cepapi) is a partially arboreal diurnal tree squirrel endemic to Sub-Saharan Africa (Kingdon, Reference Kingdon1997; Pappas and Thorington, Reference Pappas, Thorington and Happold2013; Monadjem et al. Reference Monadjem, Taylor, Denys and Cotterhill2015). Currently, ten subspecies are recognized, of which P. cepapi is distributed throughout the north and north-eastern regions of South Africa as well as regions in Namibia, southern Botswana and Zimbabwe (Thorington and Hoffmann, Reference Thorington, Hoffmann, Wilson and Reeder2005; Thorington et al. Reference Thorington, Koprowski, Steele and Whatton2012). The squirrel is typically observed in woodland habitats consisting of mopane, Colophospermum mopane, and Vachellia (previously known as Acacia) trees, as the old, hollowed branches of these trees act as ideal breeding and nesting areas (Linzey and Kesner, Reference Linzey and Kesner1997a; Skinner and Chimimba, Reference Skinner and Chimimba2005). Within these habitat types, P. cepapi can occur in large numbers, and a localized study in mopane woodland reported that they can constitute more than 80% of the regional small mammal biomass (Linzey and Kesner, Reference Linzey and Kesner1997b).

This uniquely social tree squirrel lives in family groups of five individuals on average (Viljoen, Reference Viljoen1977a). The family group not only shares the nest but also partakes in allo- and autogrooming, group foraging and territory protection (Viljoen, Reference Viljoen1977a; Skinner and Chimimba, Reference Skinner and Chimimba2005). Depending on food availability and season, its diet consists of various fruits, seeds, flowers and insects foraged from the ground and trees (Viljoen, Reference Viljoen1977b; De Graaf, Reference De Graaf1981; Skinner and Chimimba, Reference Skinner and Chimimba2005; Thorington et al. Reference Thorington, Koprowski, Steele and Whatton2012). Ground foraging generally occurs in areas where tall and dense vegetation is absent (Viljoen, Reference Viljoen1977b). Nests in tree cavities are lined with leaves and grass, which are frequently removed and replaced (Thorington et al. Reference Thorington, Koprowski, Steele and Whatton2012). P. cepapi can be considered opportunistic due to its successful adaptation to anthropogenic habitats. For example, the squirrel is often observed near human settlements and often damages the roofs and electrical wiring of houses (Banotai et al. Reference Banotai, Mazzamuto and Koprowski2023). Behavioural characteristics such as their social structure, diet, nest type and use of various habitats can influence the degree of exposure to a variety of parasites (Hillegass et al. Reference Hillegass, Waterman and Roth2008; Lucatelli et al. Reference Lucatelli, Mariano-Neto and Japyassú2020).

Current literature on the parasites associated with P. cepapi is limited to parasite-host monographs (Ledger, Reference Ledger1980; Durden and Musser, Reference Durden and Musser1994; Segerman, Reference Segerman1995; Horak et al. Reference Horak, Heyne, Williams, Gallivan, Spickett, Bezuidenhout and Estrada-Pena2018) and a single study conducted on P. c. cepapi in South Africa in 1973/74 (Viljoen, Reference Viljoen1977c). These literature sources are often limited in their sample size and span small geographic areas, and they also lack quantitative data on all associated ecto- and helminth parasites. According to the literature, P. cepapi acts as a host for 13 parasite species (one nematode, one mesostigmatic mite, one unidentified trombiculid mite, one unidentified hypopi of sarcoptiform mites, two fleas, four lice and three ticks) (Viljoen, Reference Viljoen1977b, Reference Viljoen1977c; Ledger, Reference Ledger1980; Hugot, Reference Hugot1981; Durden and Musser, Reference Durden and Musser1994; Segerman, Reference Segerman1995; Horak et al. Reference Horak, Heyne, Williams, Gallivan, Spickett, Bezuidenhout and Estrada-Pena2018). However, given the squirrel’s geographic range and opportunistic nature, it is predicted that this parasite diversity is underestimated. Further, little is known about potential factors that can drive parasite infestations in the squirrel. It is possible that parasite infestations can be related to one or more host-related factors such as age, sex and reproductive state (Morand and Poulin, Reference Morand and Poulin2002; Morand et al. Reference Morand, Bouamer, Hugot, Morand, Krasnov and Poulin2006; Kamiya et al. Reference Kamiya, O’Dwyer, Nakagawa and Poulin2014), and this is also in need of further investigation.

In order to address the lack of information on the parasite diversity associated with P. cepapi, and more specifically the subspecies P. c. cepapi, squirrels were opportunistically sampled at multiple localities across their distribution in the Savanna biome of South Africa and all macroparasites were recorded. The aim of the study was to provide quantitative data on the ecto- and helminth parasite diversity that is associated with P. cepapi in South Africa and to explore potential host factors that can affect parasite infestations.

Materials and methods

Study area and sample collection

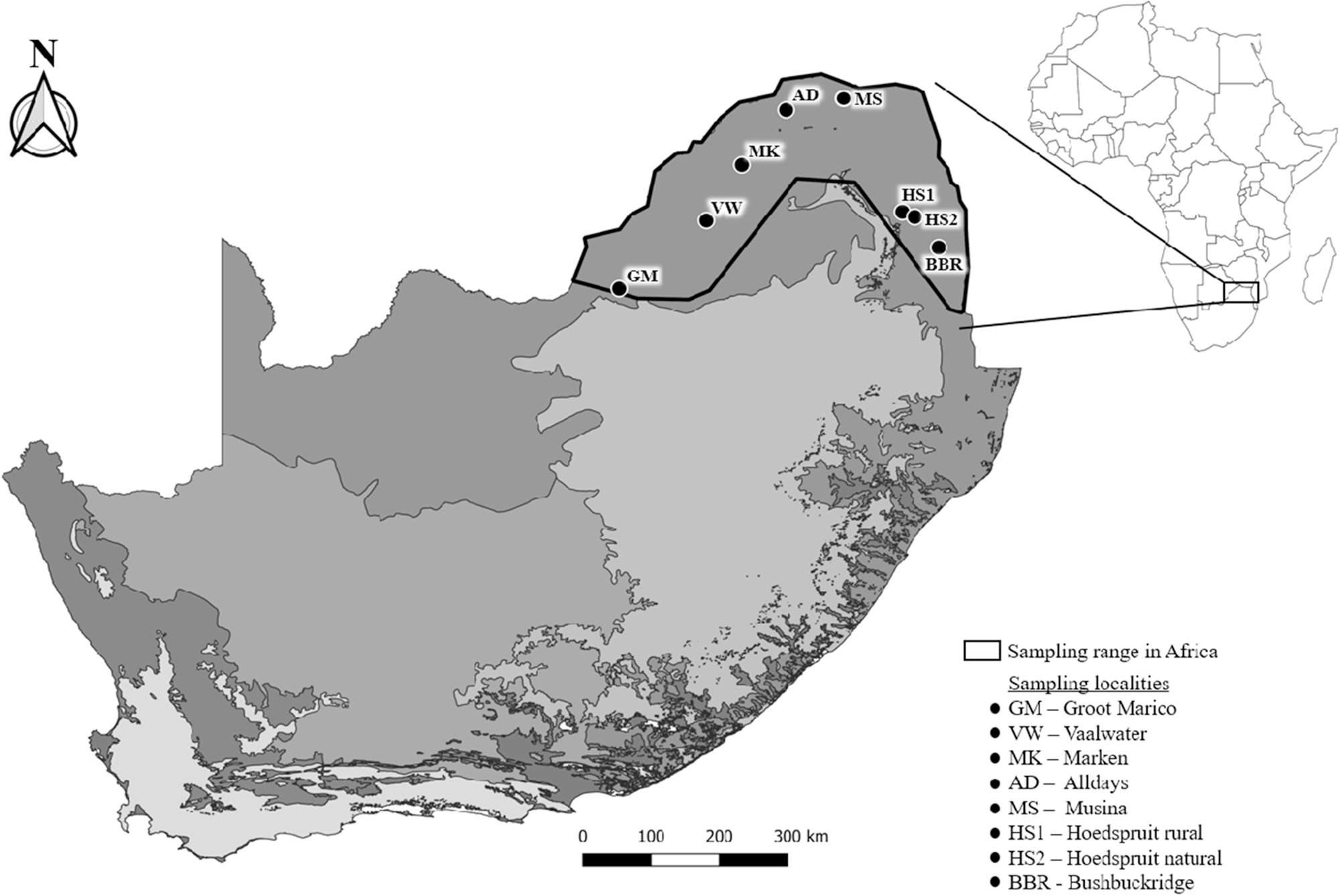

A total of 94 P. cepapi individuals were opportunistically collected (road kills, culling and traps) from eight localities in the Savanna woodlands of Limpopo, Mpumalanga and the North-West provinces of South Africa during 2020 to 2024 (Table 1; Figure 1). The localities included reserves, farms, and rural areas. Samples were collected throughout the year. Locality information and collection date were obtained for each sample. Collected individuals were individually frozen in labelled plastic bags at −20°C.

Figure 1. Localities (N = 8) where Paraxerus cepapi were obtained in the Savanna biome (2020–2024). Black outline represents the distribution range of the squirrel in South Africa. Locality codes correspond to Table 1. The various biomes of South Africa are indicated by the different shades of grey and obtained from openAFRICA (2015).

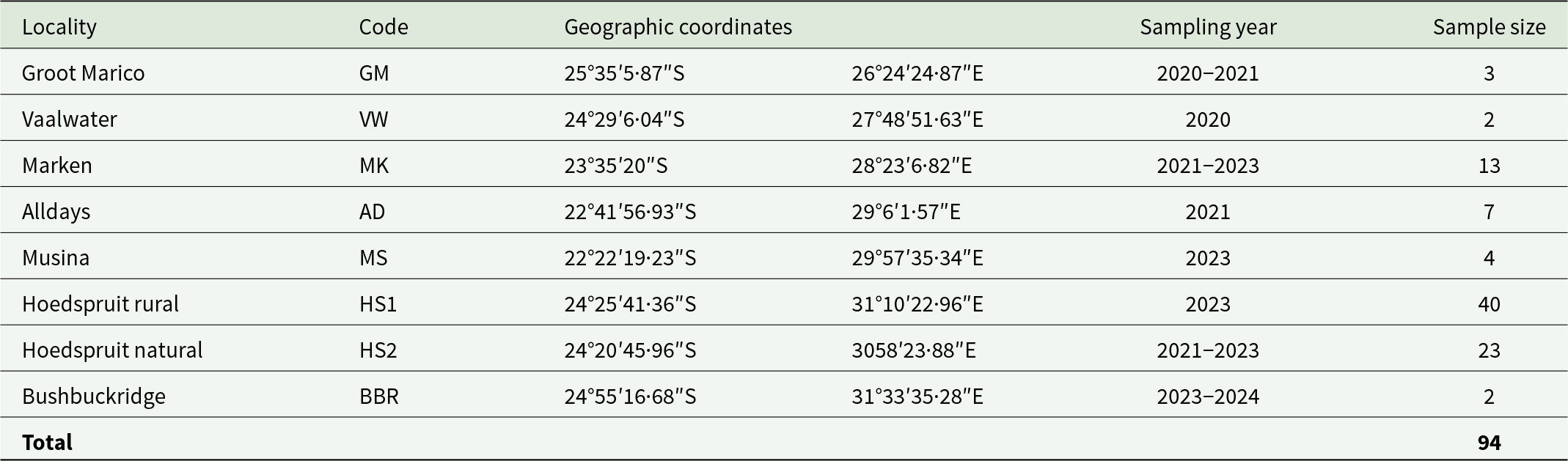

Table 1. Sampling localities (n = 8), together with codes and geographic coordinates, sampling year and number of Paraxerus cepapi collected from the Savanna biome of South Africa during 2020–2024

Host examination and parasite removal

Prior to parasite removal, squirrel carcasses were thawed and systematically examined for all ectoparasites using fine-point forceps and a Leica MZ75 stereomicroscope. All ectoparasites (lice, ticks, fleas and mesostigmatic mites), apart from chiggers (trombiculid mites), were removed, counted and preserved in tubes filled with 100% ethanol. For the chiggers, only a subsample of chiggers was collected, and the parasitope (preferred attachment site on the host) was recorded. All the chiggers that were collected per parasitope were placed in the same sample tube. In addition, the distribution of individual louse species across three body regions (head, dorsal or ventral) of the host body was recorded for a subsample (n = 28) of the hosts. All the lice that were collected per parasitope were placed in the same sample tube.

After the removal of ectoparasites, the squirrels were dissected to remove the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). All helminths were removed from the stomach, small intestine, caecum and large intestine by placing each organ in a petri dish and examining the contents and organ wall using fine-point forceps and a stereomicroscope. All helminths were stored in 100% ethanol. The parasitope of the individual helminth species was recorded.

Information pertaining to the host, such as sex, weight, total length, hind foot length and reproductive stage, was recorded, with the exception of road kills, as their condition did not allow for such information to be collected. For males, the reproductive stage was classified as scrotal or non-scrotal depending on the visibility of the testicles on the exterior of the squirrel. For females, the reproductive stage was classified as perforated or non-perforated vagina, as well as pregnant or non-pregnant for perforated females. Pregnancy was determined during dissection.

Parasite processing and identification

The different parasite groups were prepared for identification as follows. The lice were separated into morphospecies, after which a subsample (two males and two females per locality) of each morphospecies was cleared in lactic acid and mounted in polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) on microscope slides. A second subsample of each morphospecies was kept for molecular analysis, not reported herein. The immature life stages of lice remained undifferentiated and were reported as nymphs, and counts were presented per species. A subsample of chiggers and the mesostigmatic mite were slide-mounted in PVA, while the ticks and fleas remained unmounted in 100% ethanol. In the case of nematodes, a subsample (ten males and ten females per locality) was temporarily mounted in lactophenol, and another subsample (two females per locality) was kept for molecular identification not reported herein. Cestodes remained unmounted in 100% ethanol.

Ectoparasites and nematodes were identified to genus level or, where possible, to species level using various taxonomic reference keys. Identification of lice was done following Cummings (Reference Cummings1912), Ferris (Reference Ferris1919) and Werneck (Reference Werneck1947). Tick identification followed Hoogstraal and El Kammah (Reference Hoogstraal and El Kammah1974), Walker et al. (Reference Walker, Keirans and Horak2000), Apanaskevich et al. (Reference Apanaskevich, Horak and Camicas2007) and Horak et al. (Reference Horak, Heyne, Williams, Gallivan, Spickett, Bezuidenhout and Estrada-Pena2018), while the two female fleas were identified to genus level following Segerman (Reference Segerman1995). Various taxonomic references (e.g., Till, Reference Till1963; Herrin and Tipton, Reference Herrin and Tipton1976) were used, and expert taxonomists (Eddie Ueckermann, North-West University, South Africa and Wayne Knee, Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, Canada) assisted with the identification of the single female mesostigmatic mite specimen. Chigger identification followed Stekolnikov (Reference Stekolnikov2018) together with various taxonomic literature on African chiggers reviewed therein and Stekolnikov and Matthee (Stekolnikov and Matthee Reference Stekolnikov and Matthee2019, Reference Stekolnikov and Matthee2022). Nematodes, and particularly members of the genus Syphatineria, previously Syphacia, were identified according to Sandground (Reference Sandground1933), Hugot (Reference Hugot1981); Anderson et al. (Reference Anderson, Chabaud and Willmott2009), and Gibbons (Reference Gibbons2010). The species diagnosis of the recorded Strongyloides species was done based on parasitic females that were morphologically and morphometrically compared to four Strongyloides species – of which three species (S. fuelleborni, S. ratti and S. stercoralis) have previously been recorded in Africa (Pampiglione and Ricciardi, Reference Pampiglione and Ricciardi1972; Genta, Reference Genta1989; Julius et al. Reference Julius, Schwan and Chimimba2017) and one species (S. robustus) occurs in tree squirrels in North America and Europe (Bavay, Reference Bavay1877; Linstow, Reference Linstow1905; Sandground, Reference Sandground1925; Little, Reference Little1966; Speare, Reference Speare1986; Bartlett, Reference Bartlett1995). The two cestode individuals remained unidentified.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics of the parasites were performed following Bush et al. (Reference Bush, Lafferty, Lotz and Shostak1997). For each taxonomic group, as well as for each identified species within the group, the mean abundance was calculated as the sum of individuals in the taxonomic group and/or species divided by the total number of hosts that were examined, regardless of parasite presence. Prevalence was calculated as the sum of hosts, per taxonomic group and/or species within the group, that had one or more parasite individuals present, divided by the total number of examined hosts.

The relationship between parasite infestation and host factors (body size – total body length as proxy, sex, reproductive state and the interaction between sex and reproductive state) was assessed for the most prevalent and abundant parasite taxa (lice and nematodes). Total counts per parasite taxon were calculated for each host individual. Lice count data were modified (log + 1 transformed) prior to analyses to reduce variation and overdispersion in the data. Generalized linear mixed-effect models (GLMM) were constructed for lice counts following a Poisson distribution (Zuur et al. Reference Zuur, Ieno, Walker, Saveliev and Smith2009) with the vegan package (Oksanen et al. Reference Oksanen, Kindt, Legendre, O’Hara, Simpson, Solymos, Stevens and Wagner2007) in R (R Core Team, 2023) using year, site and month as random factors (exploratory analysis based on AIC suggested a stronger support for the Poisson distribution compared to a negative binomial distribution). This was followed by model selection using the drop1 function (which drops every non-significant variable, i.e., does not influence the final model). For the nematode count, the data were log + 1 transformed, and thereafter a generalized linear model (GLM) with a Poisson distribution was used (the random factors were not included due to zero variance). The removal of an extreme outlier (a squirrel with 1062 nematodes) reduced the AIC from 344·9 to 339·7. The drop1 function was again used for model selection.

Results

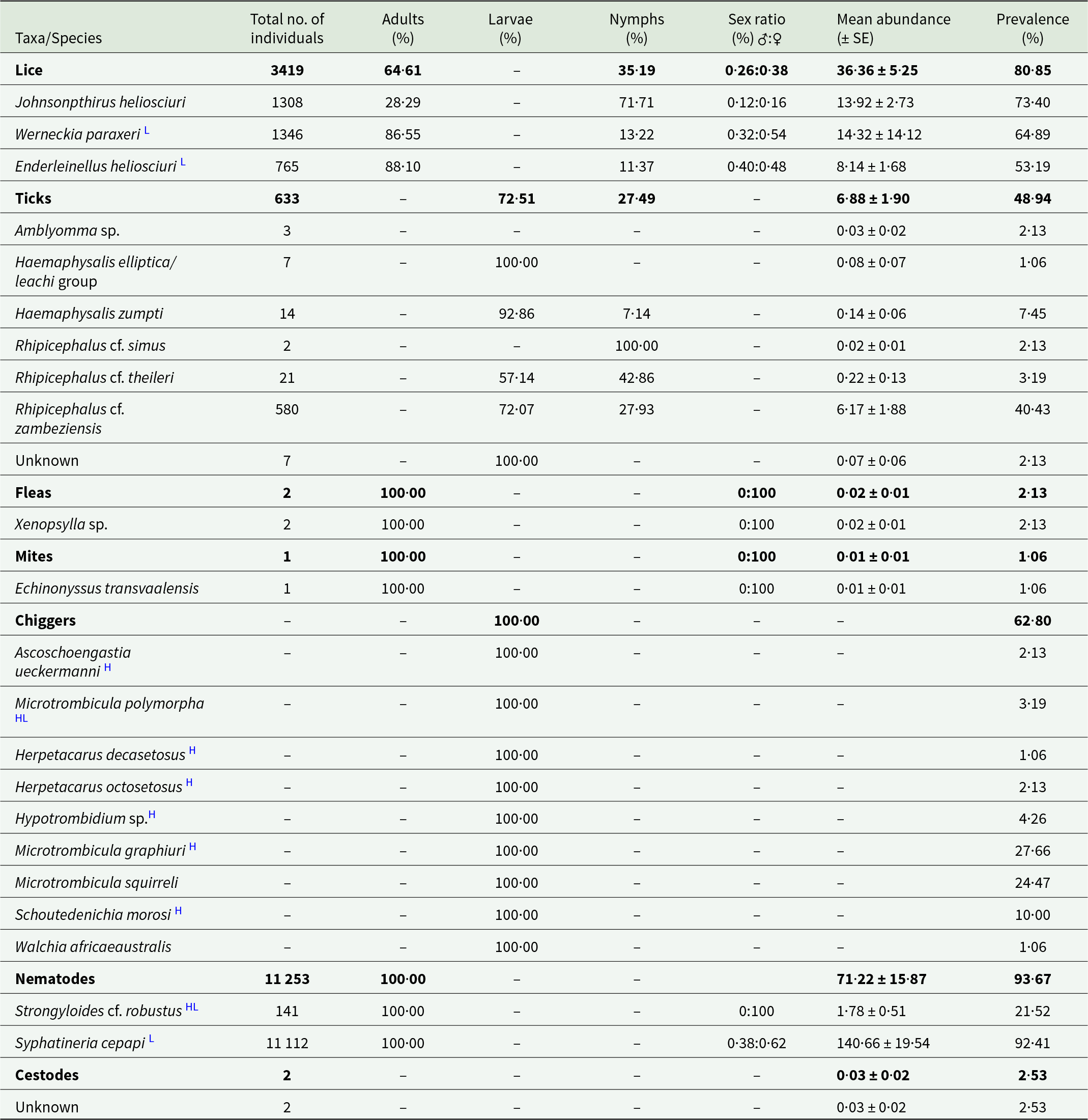

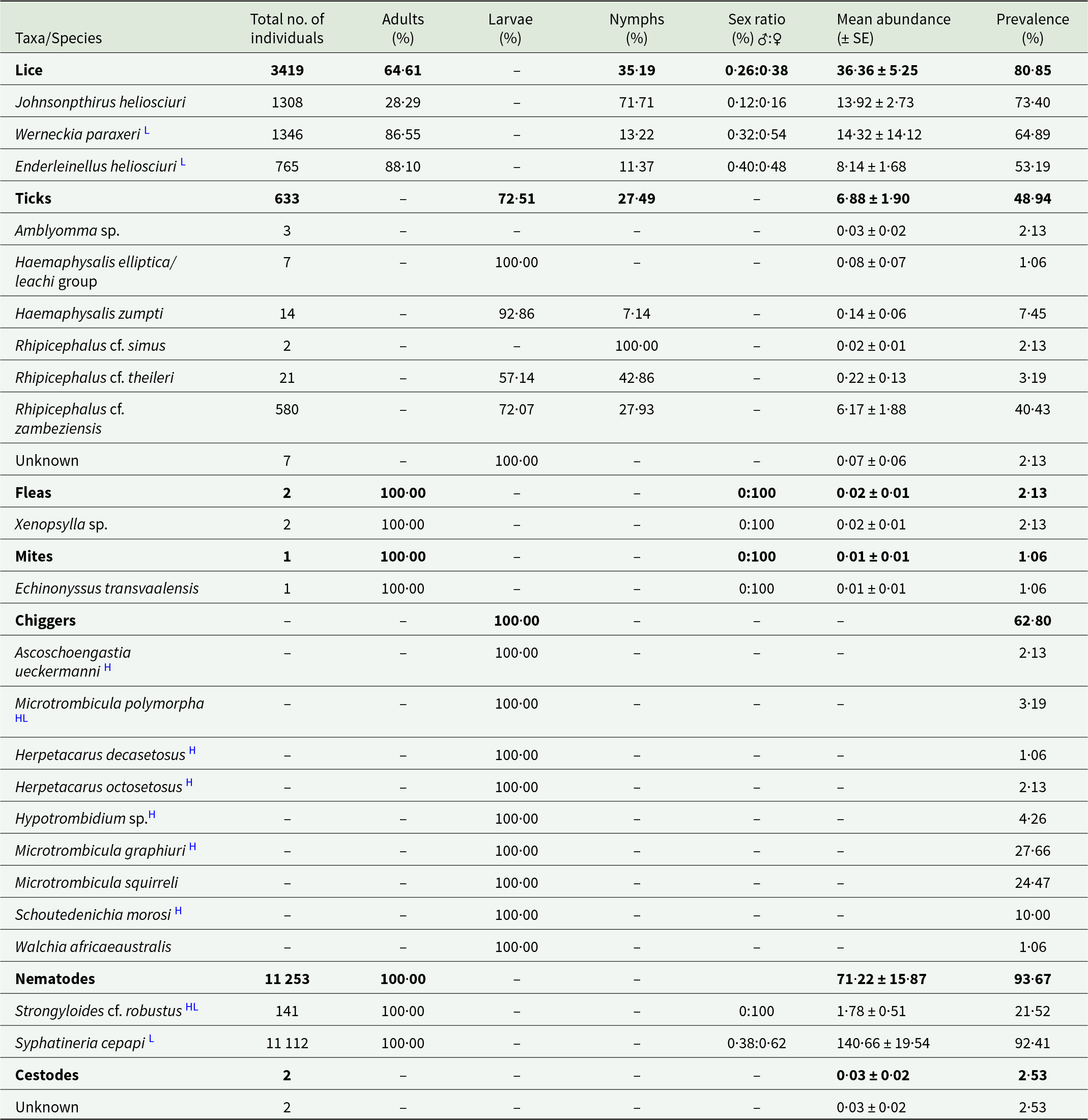

In total, 21 parasite species and one tick species group were identified, of which 19 species were ectoparasites and two were nematodes (Table 2; Supplementary Table 1). Three louse species (Johnsonpthirus heliosciuri, Werneckia paraxeri and Enderleinellus heliosciuri) were recorded (Table 2). J. heliosciuri was the most prevalent (73·40%), followed by W. paraxeri (64·89%) and E. heliosciuri (53·19%). However, of the three species, W. paraxeri was the most abundant (14·32 ± 14·12) (Table 2). All three louse species co-occurred at five of the eight localities, and J. heliosciuri was recorded at seven of the eight localities (Supplementary Table 2). Adult lice were more prevalent than the nymph life stage for W. paraxeri and E. heliosciuri, while the opposite was recorded for J. heliosciuri (Table 2). Adult females appear to be more prevalent compared to males in all three louse species (Table 2). From the parasitope records (head, dorsal and ventral), J. heliosciuri was the most common in the dorsal region, while E. heliosciuri was more common in the head region, and W. paraxeri was equally common in all three parasitopes (Table 3).

Table 2. Infestation parameters of ecto- and helminth parasites recorded on Paraxerus cepapi (n = 94) in the Savanna biome, South Africa (2020–2024)

H New host record.

L New locality record.

HL New host and locality record.

Table 3. Prevalence (%) of louse species per parasitope on Paraxerus cepapi (n = 28) obtained from five localities in the Savanna biome, South Africa (2021; 2023–2024)

Five tick species and one species group were recorded (Table 2). Rhipicephalus cf. zambeziensis was the most prevalent (40·43%), followed by Haemaphysalis zumpti (7·45%) and Rhipicephalus cf. theileri (3·19%) (Table 2). Furthermore, larvae were more common (72·51%) compared to nymphs (27·49%), and no adult life stages were recorded (Table 2). Seven unidentified individuals (due to damage to mouth parts) were recorded at Musina (Supplementary Table 2).

Two flea individuals (both females) from the genus Xenopsylla and one adult female mite, Echinonyssus transvaalensis, were recorded (Table 2).

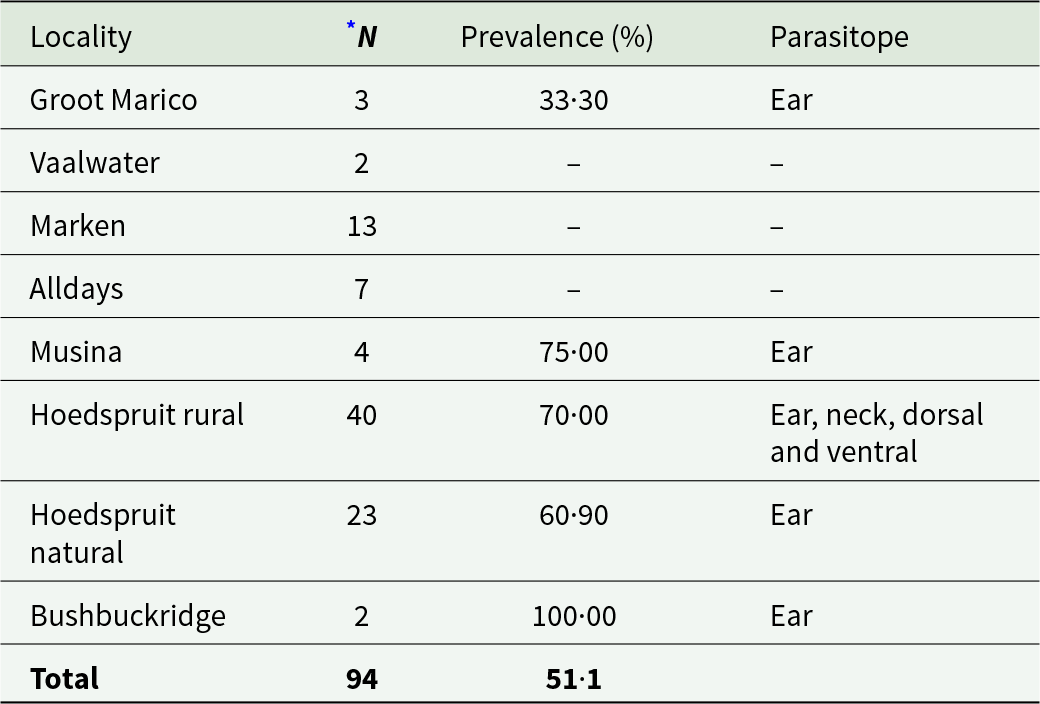

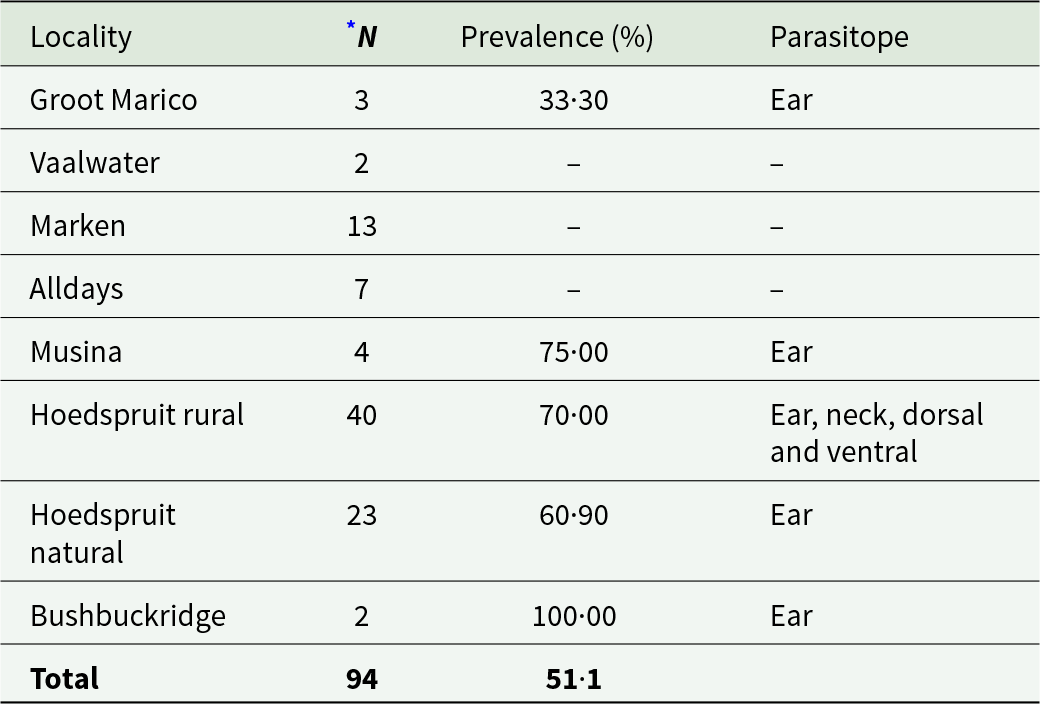

Chiggers were present on 62·80% of the squirrels (Table 2) and were recorded at five of the eight localities (Table 4). Microtrombicula graphiuri was the most prevalent species (27·66%), followed by Microtrombicula squirreli (24·47%) (Table 2). Microtrombicula squirreli occurred at four of the eight localities (Supplementary Table 2). Nine chigger species were recorded at Hoedspruit rural (Supplementary Table 2). Chiggers mainly occurred in the ear of the hosts (Table 4).

Table 4. Prevalence (%) and parasitope preference of chiggers on Paraxerus cepapi (n = 94) per sampling locality in the Savanna biome, South Africa (2020–2024)

* N = total number of host individuals per locality.

Syphatineria cepapi was the most prevalent (92·41%) and widespread nematode (occurred at 7 localities) and was predominantly found in the caecum (70·87%) (Table 2; Supplementary Table 2). Based on the morphological and morphometric assessment, S. cf. robustus was the most plausible taxonomic identification. Strongyloides cf. robustus occurred in 21·52% of the squirrels (in the small intestine) and was only recorded at the 2 Hoedspruit localities (Table 2; Supplementary Table 2). Only adult females were recorded (Table 2). The two unidentified cestodes were recorded at different localities and different parasitopes in the gastrointestinal tract (stomach and small intestine).

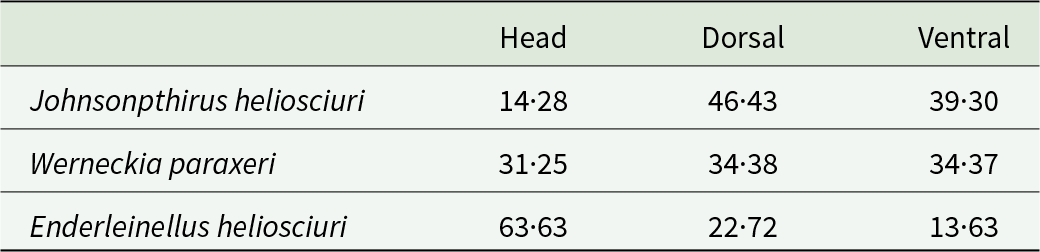

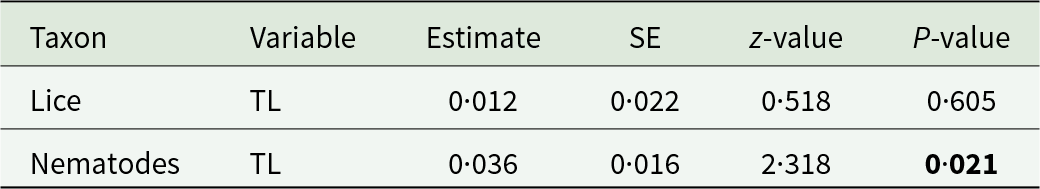

Assessment of the relationship between louse and nematode abundance, respectively, and host factors revealed no significant relationship between the number of louse individuals and any of the host factors. However, the number of nematode individuals was significantly related only to host total length (host size), with larger individuals harbouring more nematodes (Table 5).

Table 5. Summary of the final selected generalized linear mixed-effect model (lice) and generalized linear model (nematodes) with a Poisson distribution on the effect of host total length (TL) on the louse and nematode abundance on Paraxerus cepapi (n = 94) in the Savanna biome, South Africa (2020–2024). Bold text indicates significant responses

Discussion

P. cepapi, and more specifically P. c. cepapi, in South Africa hosts a relatively large diversity of parasite taxa, of which lice were the most prevalent ectoparasite group and nematodes the most prevalent helminth group. The sucking louse, J. heliosciuri is a recognized louse species of P. cepapi and other tree and bush squirrels in Africa (Funisciurus and Paraxerus) (Ferris, Reference Ferris1919; Viljoen, Reference Viljoen1977c; Durden and Musser, Reference Durden and Musser1994). The louse was originally described from the red squirrel, Paraxerus palliatus, in Kenya (Cummings, Reference Cummings1912) and later recorded from several other Paraxerus species distributed across Africa, including Namibia (Johnson, Reference Johnson1960) and South Africa (Durden and Musser, Reference Durden and Musser1994). The species’ occurrence on African squirrels is characteristic of members of the genus Johnsonpthirus (Kim and Adler, Reference Kim and Adler1982; Durden and Musser, Reference Durden and Musser1994). It is important to note that recent genetic studies have indicated cryptic speciation among conspecific lice occurring on different rodent species (du Toit et al. Reference du Toit, van Vuuren, Matthee and Matthee2013; Bothma et al. Reference Bothma, Matthee and Matthee2019), and more in-depth comparative research is required to fully understand the taxonomy of J. heliosciuri on P. cepapi (Martinu et al. Reference Martinu, Sychra, Literak, Capek, Gustafsson and Stefka2015).

The present study recorded two additional louse species, W. paraxeri and E. heliosciuri, that belong to the family Enderleinellidae and are exclusive parasites of Sciuridae (Ferris, Reference Ferris1919; Kim, Reference Kim, Morand, Krasnov and Poulin2006). These lice taxa were not previously recorded by Viljoen (Reference Viljoen1977c), but W. paraxeri was previously recorded from P. cepapi in Namibia, while E. heliosciuri was recorded from P. cepapi at an unknown locality (Johnson, Reference Johnson1960; Durden and Musser, Reference Durden and Musser1994). Thus far, the distribution of E. heliosciuri includes Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Liberia, Tanzania and Uganda (Durden and Musser, Reference Durden and Musser1994). The present study is the first record of W. paraxeri and E. heliosciuri on P. cepapi in South Africa and thereby documents the most southern locality for the two louse species in Africa. It is interesting to note that the body size of J. heliosciuri is almost double the size (adult males measure 1·24 mm and adult females 1·74 mm) of W. paraxeri (0·55 and 0·68 mm, respectively) and E. heliosciuri (0·59 and 0·8 mm, respectively). Further, in the present study, W. paraxeri and E. heliosciuri were attached to the base of the hair shaft at the skin. The absence of the two louse species in the study by Viljoen (Reference Viljoen1977c) might be due to several reasons. In the present study, the squirrels were systematically examined under a stereomicroscope, while in the previous study, squirrels were most likely brushed (although no information regarding parasite removal is given). It is also possible that the lice were absent at the three sampling localities studied by Viljoen, (Reference Viljoen1977c).

The presence of two or three louse species is not uncommon for tree squirrels (Kim, Reference Kim, Morand, Krasnov and Poulin2006; Durden et al. Reference Durden, Beati, Greiman and Abramov2024). For example, Pung et al. (Reference Pung, Durden, Patrick, Conyers and Mitchell2000) recorded three louse species on the southern flying tree squirrel (Glaucomys volans) in the USA, while Romeo et al. (Reference Romeo, Pisanu, Ferrari, Basset, Tillon, Wauters, Martinoli, Saino and Chapuis2013) recorded two louse species on the Eurasian red tree squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) in Italy and France. In both instances, the lice species belonged to different families. The three louse species in the present study were all relatively common (each occurred on more than 50% of the squirrels and co-occurred at least five localities). However, it is evident that two of the three louse species preferred distinct body regions. This, together with the fact that the two smaller species occur at the hair base where they grasp under the hairs (Durden et al. Reference Durden, Beati, Greiman and Abramov2024), while J. heliosciuri was usually found further along the hair shaft away from the skin, which may facilitate the co-occurrence of multiple louse species on a single host. This pattern aligns with the concept of spatial niche partitioning (Chase and Leibold, Reference Chase and Leibold2012) and has been recorded in other parasite-host systems (Barnard et al. Reference Barnard, Krasnov, Goff and Matthee2015; Fernández-González et al. Reference Fernández-González, Pérez-Rodríguez, de la Hera, Proctor and Perez-Tris2015; Stefan et al. Reference Stefan, Gómez-Díaz, Elguero, Proctor, McCoy and Gonzalez-Solis2015).

Rhipicephalus cf. zambeziensis was the most common and widespread tick species on P. cepapi. Rhipicephalus zambeziensis was previously recorded on P. cepapi in South Africa (Horak et al. Reference Horak, Heyne, Williams, Gallivan, Spickett, Bezuidenhout and Estrada-Pena2018). Similarly, the presence of R. simus, R. theileri and H. zumpti on P. cepapi is supported by Viljoen (Reference Viljoen1977c) and Horak et al. (Reference Horak, Heyne, Williams, Gallivan, Spickett, Bezuidenhout and Estrada-Pena2018). In the present study, only tick larvae and nymphs were recorded on P. cepapi. These life stages have fewer discerning morphological features and are thus more difficult to identify to species level (Walker et al. Reference Walker, Keirans and Horak2000). This is especially relevant for African species in the genus Rhipicephalus. To obtain conclusive evidence on the taxonomic status of the tick species, future studies should focus on a more comprehensive sampling of the ticks throughout their range in South Africa and Africa and should also include broad-scale molecular characterization of all the species known to be part of species complexes. Nonetheless, Hoogstraal and El Kammah (Reference Hoogstraal and El Kammah1974) noted that both adult and immature life stages of H. zumpti can occur on sciurid species and especially squirrels within the genus Paraxerus. In this study, however, adult H. zumpti were absent

Fleas and mites were less common on P. cepapi. The presence of Xenopsylla fleas on P. cepapi is in agreement with previous studies that recorded X. brasiliensis (Haeselbarth et al. Reference Haeselbarth, Segerman, Zumpt and Zumpt1966; Viljoen, Reference Viljoen1977c) and X. zumpti (Haeselbarth et al. Reference Haeselbarth, Segerman, Zumpt and Zumpt1966) on P. cepapi in South Africa. The presence of E. transvaalensis (Hirstionyssinae) is in agreement with the study by Viljoen (Reference Viljoen1977c). At the time of the latter study, the particular mite was classified in the genus Hirstionyssus and referred to as Hirstionyssus transvaalensis. Fleas and mesostigmatic mites are both nest parasites with most life stages occurring in the host’s nest (Lehane, Reference Lehane2005; Dowling, Reference Dowling, Morand, Krasnov and Poulin2006). As such, the diversity and abundance of fleas and mites are often related to the microclimatic conditions in the nest (Moreno et al. Reference Moreno, Merino, Lobato, Ruiz-De-Castaneda, Martinez-De La Puente, Del Cerro and Rivero-De Aguilar2009). P. cepapi is known for frequently cleaning nest holes by removing and replacing the nesting material (Thorington et al. Reference Thorington, Koprowski, Steele and Whatton2012), and this behaviour may create unfavourable conditions for fleas and mites (Bush and Clayton, Reference Bush and Clayton2018). Other contributing factors include auto- and allogrooming between conspecifics, a frequent practice for P. cepapi (Viljoen, Reference Viljoen1977a; Hawlena et al. Reference Hawlena, Bashary, Abramsky and Krasnov2007; Moreno et al. Reference Moreno, Cantarero, López-Arrabé, Rodriguez-Garcia, Gonzalez-Braojos, Ruiz-De-Castaneda and Redondo2013), and the incorporation of aromatic plants as nest material. Although there is no evidence yet as to the specific type of plant materials P. cepapi uses, besides leaves and grass, studies of other host-parasite systems (e.g. passerine birds such as the European Starling and its parasite load) have shown that the use of aromatic plants as part of the nesting material can act as a natural parasite repellent (Clark and Mason, Reference Clark and Mason1985; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Ye, Huo, Moller, Liang and Feeney2020). Furthermore, the opportunistic sampling approach that was used in the study most probably biased the flea abundances. Fleas are known to abandon dead hosts as soon as the host’s body temperature begins to decrease (Russell, Reference Russell1913; Westrom and Yescott, Reference Westrom and Yescott1975). Any delay in placing a dead animal in a sample collection bag will allow fleas to leave the host and will bias the flea count. It is recommended that future studies adopt a standardized sampling approach that includes equal sample sizes per locality, a live-trapping approach and total ectoparasite counts.

Chiggers were the most speciose group of parasites on P. cepapi. Similar to previous rodent-chigger studies in South Africa (Fagir et al. Reference Fagir, Ueckermann, Horak, Bennett and Lutermann2014; Stevens et al. Reference Stevens, Stekolnikov, Ueckermann, Horak and Matthee2022; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Krasnov, Horak, Ueckermann and Matthee2023), the ear was the preferred attachment site in the present study. Viljoen (Reference Viljoen1977c) previously identified chiggers on P. cepapi to genus level as a species similar to Schoengastia. Besides this record, there were no other chigger records associated with P. cepapi up to the present time, as well as very few species records associated with squirrels belonging to the genus Paraxerus in general. According to Vercammen-Grandjean (Reference Vercammen-Grandjean1958a, Reference Vercammen-Grandjean1958b, Reference Vercammen-Grandjean1965), four species (Mictrotrombicula becquaerti, Mictrotrombicula paraxeri, Schoengastia katangae and Schoutedenichia paraxeri) were previously recorded on the subspecies P. c. quotus, while Schoutedenichia lumsdeni was described from a host identified as a Paraxerus species from the Kruger National Park, South Africa. One new species, Walchia africaeaustralis, was recently described based on the material presented in Stekolnikov et al. (Reference Stekolnikov, Barnard, Raubenheimer, Little, Singo, Kipling and Matthee2025). As such, the present study provides new host records for eight of the nine recorded chigger species. Six of these species (Ascoschoengastia ueckermanni, Herpetacarus decasetosus, Herpetacarus octosetosus, Microtrombicula graphiuri, Microtrombicula squirreli and Schoutedenichia morosi) were previously recorded on rodents in South Africa (Stekolnikov and Matthee, Reference Stekolnikov and Matthee2019; Matthee et al. Reference Matthee, Stekolnikov, Van der Mescht, Froeschke and Morand2020; Stevens et al. Reference Stevens, Stekolnikov, Ueckermann, Horak and Matthee2022) and may therefore represent the chigger fauna characteristic of this region. Microtrombicula polymorpha is herein recorded in South Africa for the first time. This species was previously reported from two localities in DR Congo on three species of birds (Vercammen-Grandjean, Reference Vercammen-Grandjean1965). Identification of Hypotrombidium sp. to the species level requires a revision of this genus in South Africa.

In the present study, S. cepapi was a very common and widespread nematode species of P. cepapi. This nematode was primarily recorded in the caecum, followed by the large intestine. Viljoen (Reference Viljoen1977b) recorded a different Syphatineria species, Syphacia paraxeri (at that stage still in the genus Syphacia), on P. cepapi at five localities in South Africa. However, it is possible that the identification of the Syphatineria specimens in Viljoen’s study was incorrect, given that, firstly, oxyurid pinworms are host specific, meaning they only occur in one (type) host (Sorci et al. Reference Sorci, Morand and Hugot1997), and the ‘type host’ for S. paraxeri is P. palliatus (Sandground, Reference Sandground1933). Secondly, subsequent to Viljoen’s study (Reference Viljoen1977b), Hugot (Reference Hugot1981) described S. cepapi from specimens obtained from one locality (Pretoria) in South Africa. The present study, therefore, provides new locality records for S. cepapi in South Africa. Transmission between hosts occurs directly through ingestion of eggs during grooming or coprophagy (Anderson, Reference Anderson1988, Reference Anderson2000). The relatively high prevalence of S. cepapi in P. cepapi is not unexpected given that the squirrel lives in small family groups that frequently partake in allogrooming (Viljoen Reference Viljoen1977a).

The morphological characteristics of the Strongyloides species recorded in P. cepapi are not in agreement with any of the known Strongyloides species that have been documented for Africa (S. fuelleborni and S. stercoralis) and even South Africa (S. ratti) (Schär et al. Reference Schär, Trostdorf, Giardina, Khieu, Muth, Marti, Vounatsou and Odermatt2013; Viney and Lok, Reference Viney and Lok2015; Julius et al. Reference Julius, Schwan and Chimimba2017). Species–specific differences were observed in the length of several morphological features, such as the tail length and oesophagus length (Speare, Reference Speare1986). Further, the twisting ovary and intestine that are present in S. cf robustus is absent in S. stercoralis and S. ratti (Little, Reference Little1966). Apart from the differences in measurements, the above-mentioned Strongyloides species exhibit different host preferences compared to S. cf robustus. For example, S. fuelleborni primarily occurs in African primates with the possibility of infecting humans (Linstow, Reference Linstow1905), while S. stercoralis occurs in humans (Genta, Reference Genta1989) and S. ratti in rats (Sandground, Reference Sandground1925). It is interesting to note that most of the morphological characteristics of S. cf. robustus are, on average, shorter but closer to S. robustus sensu stricto from tree squirrels in the USA (Speare, Reference Speare1986; Bartlett, Reference Bartlett1995). However, the inclusion of molecular characterization, with more comprehensive taxonomic and geographic sampling of Strongyloides, is required to obtain a more robust species diagnosis.

The presence of only female S. cf. robustus nematodes is characteristic of the genus and supported by Bartlett (Reference Bartlett1995) and Viney and Lok (Reference Viney and Lok2015). The lower prevalence of S. cf. robustus compared to S. cepapi in P. cepapi is not uncommon, as a similar pattern was recorded in previous studies on rodents in South Africa (Julius et al. Reference Julius, Schwan and Chimimba2017) and elsewhere (Pung et al. Reference Pung, Durden, Patrick, Conyers and Mitchell2000). The pattern might be due to life history differences, such as the transmission mode, between the two genera. In the case of Strongyloides, hosts become infected when the eggs found in the host faeces develop into infective L3 filariform stages via sexual and/or asexual development and penetrate the host skin when the host comes into contact with the faecal matter (Viney and Lok, Reference Viney and Lok2015). This is in contrast to the life cycle of pinworms as mentioned above (Anderson, Reference Anderson2000).

Several of the identified parasites are of medical concern due to their zoonotic potential. For instance, Xenopsylla fleas are recognized vectors of Yersinia pestis, which is the causative agent of bubonic plague (Bitam et al. Reference Bitam, Dittmar, Parola, Whitting and Raoult2010). The immature stages of ticks belonging to the genera Rhipicephalus and Amblyomma have been implicated in the transmission of Rickettsia africae, the causative agent of African tick bite fever in humans (Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Beati, Mason, Matthewman, Roux and Raoult1996; Ledger et al. Reference Ledger, Innocent, Lukhele, Dorleans and Wisely2022). Additionally, several species in the genus Strongyloides have zoonotic potential, for example, S. stercoralis can infect humans and dogs and is the causative agent of strongyloidiasis (Jaleta et al. Reference Jaleta, Zhou, Bemm, Schär, Khieu, Muth, Odermatt, Lok and Streit2017), and S. fuelleborni kellyi is associated with swollen belly syndrome in humans (Bradbury, Reference Bradbury2021).

The significant positive relationship between host body size and nematode infestation is consistent with the concepts that larger-bodied individuals are often older and, as such, have had more exposure time to parasites and provide more internal space for nematodes (Morand and Poulin, Reference Morand and Poulin2002; Kamiya et al. Reference Kamiya, O’Dwyer, Nakagawa and Poulin2014; De Leo et al. Reference De Leo, Dobson and Gatto2016). This pattern has been observed in several rodent species, including the four-striped mouse (Rhabdomys pumilio) in the Western Cape Province, South Africa (Froeschke et al. Reference Froeschke, van der Mescht, McGeoch and Matthee2013), the wood mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus) in southern England (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Morley and Behnke2023), and in three rodent species (A. sylvaticus, Apodemus flavicollis and Myodes glareolus) in Serbia (Miljevic et al. Reference Miljevic, Cabrilo, Bundinski, Rajicic, Bajic, Bjelic-Cabrilo and Blagojevic2022). Many monoxenous nematodes, and particularly pinworms (Oxyuridae) and threadworms (Strongylidae), have free-living life stages that infect hosts through ingestion during feeding and or allo- and autogrooming (Anderson, Reference Anderson1988, Reference Anderson2000; Morand et al. Reference Morand, Bouamer, Hugot, Morand, Krasnov and Poulin2006). As such, larger individuals, who forage more and have lived longer, are more likely to encounter and ingest infective life stages (Morand and Poulin, Reference Morand and Poulin2002). Interestingly, nematode abundance was not significantly related to host sex, reproductive state, or their interaction. This is consistent with other studies that noted that sex-based and reproductive state differences in parasite load are not universally observed and can vary depending on host species, parasite taxon and ecological context (Zuk and Stoehr, Reference Zuk, Stoehr, Klein and Roberts2009; Duneau and Ebert, Reference Duneau and Ebert2012; Kiffner et al. Reference Kiffner, Stanko, Morand, Khokhlova, Shenbrot, Laudisoit, Leirs, Hawlena and Krasnov2013; Lo and Shaner, Reference Lo and Shaner2015; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Morley and Behnke2023). The absence of a significant relationship between louse abundance and any of the host factors may be due to several reasons. Firstly, the methods used to kill the squirrels (culling and road kills) damaged portions of the host body, which may have influenced the louse counts, especially given the small size of two of the louse species. In addition, lice are transmitted through direct body contact, such as young suckling from their mothers and grooming between family members. This behaviour may influence significant relationships with host body size, sex and reproductive state. Similar to what was mentioned above, host body size, sex and reproductive state differences for lice infestations are not universal and depend, among others, on the host species, the age structure and season (Froeschke et al. Reference Froeschke, van der Mescht, McGeoch and Matthee2013; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Krasnov, Horak, Ueckermann and Matthee2023; Little et al. Reference Little, Matthee, Ueckermann, Horak, Hui and Matthee2024)

The current study provides an update on the relatively rich ecto- and helminth parasite diversity associated with P. cepapi in South Africa. In addition, novel findings include new locality and/or country records for six of the recorded parasite species, and P. cepapi is a new host record for nine parasite species, and moreover, provides the first quantitative parasite data for P. cepapi in South Africa. Lastly, the study provides additional support for the role of host body size in shaping nematode infestations.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182025101261.

Data availability statement

All generated data for this study are included in this article. Additional data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all the farmers and landowners, and in particular Jan-Phillip Small, Reed van Zyl, Johan Jordaan, Sean du Toit and Giel Horn, who provided samples for this study. Fletcher Vincent assisted with the examination of the gastrointestinal tracts. Prof. Eddie Ueckermann and Dr Wayne Knee assisted with the mite identification. Statistical support was provided by Alyssa Little.

Author contributions

IR conducted the laboratory work, analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft chapters of the manuscript. CAM assisted with sample collection and edited earlier drafts of the manuscript. AAS identified the chiggers and contributed towards the writeup. JW and LS assisted with sample collection, provided logistical support and editorial comments. SM conceived the study, secured funding, assisted with sample collection and provided editorial comments.

Financial support

IR received personal funding from the Department of Conservation Ecology and Entomology (Stellenbosch University). Identification of chiggers was performed in the frame of the project ‘Fauna and taxonomy of chigger mites of Africa’ supported by the Russian Science Foundation (23-24-00065, to AAS).

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The project was approved by Stellenbosch University Animal Ethics (ACU-2021-21609). All necessary permits were obtained for Mpumalanga province (MPB. 5698), Limpopo province (ZA/LP/116034) and North-West province (NW 42843/08/2022) and a Section 20 [12/11/1/7/5/2057(HP)] from the Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development.