Introduction

Maintaining the trust of the citizenry is crucial for politicians if they are to retain legitimacy, yet there is ample evidence to suggest that political leaders are very often believed by those they represent to behave unethically. There is also an extensive political theory literature that has elaborated normative frameworks for evaluating ethical standards among elected representatives – frameworks that are in many cases reflected in institutional codes of conduct and other practical instruments employed to regulate the behaviour of politicians. However, neither strain of research has succeeded in demonstrating adequately how members of the public actually go about forming their evaluations of elected leaders and whether their judgments reflect the norms established by political theory. This article seeks to fill this gap by drawing on recent developments in political psychology to examine how people respond to informational cues when evaluating the ethical conduct of those who represent them and the role of attentiveness to politics in shaping such responses.

In considering the normative frameworks that are likely to shape citizens' evaluations of political ethics, we focus on values that are deeply embedded in contemporary developed democracies as well as the normative political theory subtending such values. Our analysis thus serves to provide both empirical elucidation of ethical judgment and evidence of the relevance of normative theory conceptions of political ethics to such judgment. We argue that those who are most attentive to politics and public affairs are likely to respond to informational cues reflecting nuanced ethical norms, whereas those less well versed in politics will likely use simpler rules of thumb. Specifically, we propose a multidimensional conceptualisation of ethical judgments in politics based on three norms about the holding of public office that are expected to structure citizens' responses to information: the nuanced norms of (i) avoiding conflicts of interest and (ii) delivering outcomes that maximise the public benefit; and the simple norm of (iii) conformity with the law or institutional rules. We assess the impact of each normative frame on the basis of data from an experimental survey question fielded in Great Britain. In so doing, we examine the extent to which political attentiveness affects citizens' propensity to respond to each of the three normative frames when expressing opinions about political conduct.

The next section provides a theoretical and practical grounding for our analysis. We then introduce the data and the methodological approach employed in the empirical analysis before presenting our empirical results. The final section discusses these results and concludes.

Judging politics and politicians

Existing attitudinal research into citizens' judgments about political ethics and perceptions of corruption has shed light on questions of what, who, where and how much. In practice, most studies in the existing corruption perceptions literature tend to fall into one of two categories: the first involves judgments about the propriety or corruptness of given acts and what citizens regard as acceptable or unacceptable behaviour; the second is concerned with judgments about the prevalence of misconduct or corruption in a given institution, system, region or nation. We know that people's overall views of elected politicians are generally negative (though many citizens are favourably disposed toward individual politicians), and there is evidence as to the forms of misconduct citizens find most worrisome (e.g., Atkinson & Bierling Reference Atkinson and Bierling2005; Dolan et al. Reference Dolan, McKeown and Carlson1988; Jackson & Smith Reference Jackson and Smith1996; Johnston Reference Johnston1986, Reference Johnston1991; Mancuso et al. Reference Mancuso1998; McCann & Redlawsk Reference McCann and Redlawsk2006; Peters & Welch Reference Peters and Welch1978) and how people react to politicians' justifications of their actions (Chanley et al., Reference Chanley1994; Gonzales et al., Reference Gonzales1995). We also have some idea of which types of people are most likely to be critical of political elites, and which groups are generally more tolerant of ethically dubious behaviour (e.g., Allen & Birch Reference Allen and Birch2011, Reference Allen and Birch2012; Blais et al. Reference Blais2005; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Camp and Coleman2004; Gonzales et al., Reference Gonzales1995; Johnston Reference Johnston1986; Redlawsk & McCann Reference Redlawsk and McCann2005; Steenbergen & Ellis, Reference Steenbergen, Ellis and Redlawsk2006). Footnote 10 There has been relative neglect, however, of the question of how ethical evaluations of politicians are formed. This article addresses this ‘how’ question – understood in terms of the normative frameworks that inform ethical judgment – by drawing on recent research in political psychology. The political psychology perspective has not often been used in the study of corruption perceptions, Footnote 11 and we believe it sheds important new light on judgment formation that will be of relevance to normative theorists and to policy makers, as well as to students of public opinion.

In many cases, evaluations of politicians' conduct are better understood as political judgments rather than moral judgments per se. Yet, insofar as it is possible to distinguish clearly between them, we are interested in the latter and particularly in judgments about the rights and wrongs of conduct. Political theorists and those charged with regulating institutional political conduct, such as parliamentary ethics officers and committees, have elaborated understandings of political ethics in terms of norms that pertain to the role of elected office holders (e.g., Alexandra Reference Alexandra and Primoratz2007: 89; Hampshire Reference Hampshire1978: 48–52; Philp Reference Philp2007: 152–163; Thompson Reference Thompson1987: 96–122; Reference Thompson1995: 11–25). These norms almost always rest on a distinction between ‘the public’ and ‘the private’, according to which the actions of public officials are distinguished from those of individuals in their private lives or in the private sector by virtue of the fact that they are chosen to act in the public interest.

The key feature that marks out the performance of a public or political role, as opposed to a private role, is that it involves a public trust. Breaches of this public trust are often seen by theorists and regulators as among the most significant forms of political wrongdoing. And since such breaches commonly result from conflicts of interest between the actors' public duty and their personal or partisan interests, the avoidance of conflicts of interest is usually a central preoccupation of theorists' and regulators' conceptualisations of political ethics (Committee on Standards in Public Life 1995: 19–45; Thompson Reference Thompson1995: 49–76).

At the same time, there is reason to believe that most ordinary citizens have little appreciation of theoretical and elite conceptualisations such as these. Though theories about political conduct may make their way into the educational curriculum via classes in civics (or ‘citizenship education’ as it is called in the United Kingdom), relatively nuanced normative ideas are unlikely to figure prominently in the day‐to‐day judgments of those who take little interest in public affairs. Most people can be expected to take shortcuts of one sort or another in forming their ethical evaluations of political leaders.

Research in political psychology can help to shed light on the kinds of shortcuts that citizens might employ. In line with recent trends in moral psychology, we expect that most people will devote little effort to making ethical judgments about politicians, and that they will thus use less‐demanding forms of ‘low information’ or ‘peripheral processing’ to make most evaluations (Kuklinski & Quirk Reference Kuklinski, Quirk, Lupia, McCubbins and Popkin2000; Lieberman et al. Reference Lieberman, Schneider and Oschner2003; Sears, Reference Sears and Kuklinski2001; cf. Marcus et al. Reference Marcus, Neuman and Mackuen2000). Models of motivated reasoning further suggest that most people's judgments most of the time are determined by their initial intuitive responses, and that these intuitions are themselves a reflection of prevailing group norms and/or are shaped by prior reasoned persuasion (Cassino & Lodge Reference Cassino, Lodge and Neuman2007; Haidt Reference Haidt2001, Reference Haidt2012; Lodge & Taber Reference Lodge, Taber, Lupia, McCubbins and Popkin2000, Reference Lodge and Taber2013; Taber et al. Reference Taber, Lodge, Glather and Kuklinski2001; Wagner et al. Reference Wagner, Tarlov and Vivyan2014). Such group norms and beliefs can serve as frames, which simplify judgment making by giving ‘meaning to key features of some topic or problem’ (Lau & Schlesinger Reference Lau and Schlesinger2005: 80; emphasis in original). The literature on cognitive bias further suggests that citizens can be expected to react strongly to the substantive outcome of an action, and that loss‐aversion will induce them to evaluate especially negatively actions whose outcomes result in a diminution of benefit (Arceneaux Reference Arceneaux2012; Kahneman & Tversky Reference Kahneman and Tversky2000; Tversky & Kahneman Reference Tversky, Kahneman, Kahneman and Tversky2000).

The framing effects of elite discourse (Gamson & Modigliani Reference Gamson and Modigliani1989; Nelson & Kinder Reference Nelson and Kinder1996; Tversky & Kahneman Reference Tversky, Kahneman, Kahneman and Tversky2000; Zaller Reference Zaller1992) are thus particularly relevant to our conceptualisation of how people judge politicians' conduct, since such judgments are unlikely to be the product of belief change – that is, the acquisition of new positive or negative information about an attitude object that was not formerly part of an individual's belief structure and which causes a change in opinion. Rather, ethical judgments will in most cases be instant responses to the information presented, the details of which will activate ‘information already at the recipients’ disposal, stored in long‐term memory' (Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Oxley and Clawson1997: 225).

We are interested in identifying those normative cues to which the public is likely to respond when judging political acts and situations from an ethical point of view. Each cue will thus reflect a different understanding of what is proper behaviour for public officials. In seeking to develop hypotheses, we first recognise that the norms against which behaviour in public life is judged will reflect, at least in part, distinct democratic cultural traditions. Given that the data on which we draw are from Great Britain and pertain to Members of Parliament, we identify three sets of culturally embedded norms that are likely to be especially relevant in understanding the propriety (or otherwise) of their conduct. Footnote 12 We do not claim that these are the only norms that are likely to frame citizens' ethical judgments; but they do represent particularly important ideas that structure expectations of elite conduct. Despite being drawn from British parliamentary practice, we also expect that, with minor cultural variations, these norms are also relevant in most other established democracies.

The first norm reflects a central preoccupation of most theorists and ethics regulators, and understands ethical conduct as the avoidance of conflicts of interest between an office holder's public duties and his or her private interests (Allen Reference Allen2008; Mancuso Reference Mancuso1995; Thompson Reference Thompson1995). In the British context, Members of Parliament have long been expected to represent their constituencies, individual constituents and wider interests, as well to act upon their own judgment. Yet it is well established that they should not profit from their position or influence parliamentary proceedings for personal, private gain (Allen Reference Allen2011; Judge Reference Judge1999; Williams Reference Williams1985). As the current Code of Conduct for MPs states very clearly: ‘Members shall base their conduct on a consideration of the public interest, avoid conflict between personal interest and the public interest and resolve any conflict between the two, at once, and in favour of the public interest’ (House of Commons 2012: 3). The conflict‐of‐interest avoidance norm takes us closest to the classic definition of political corruption as ‘abuse of public office for private gain’. It is also the norm that is most specific to the evaluation of political ethics. The role of public service norms and related understandings of what is proper behaviour for public officials has been found to be prominent in various previous empirical studies of ethical reasoning (Dolan et al. Reference Dolan, McKeown and Carlson1988; Alvarez & Brehm Reference Alvarez and Brehm2002; Redlawsk & McCann Reference Redlawsk and McCann2005). In some cases there has been found to be a political‐cultural element to such evaluations, which may vary from one cultural context to another (Frohlich & Oppenheimer Reference Frohlich, Oppenheimer, Lupia, McCubbins and Popkin2000).

The second norm construes political ethics and conduct in act‐utilitarian terms, specifically in terms of substantive outcomes and the maximisation of public benefit. An obvious feature of public office is that those in positions of authority are expected to deliver tangible benefits to those they serve. The importance of such considerations has been clearly demonstrated in MPs' own under understandings of political ethics (Allen Reference Allen2008; Mancuso Reference Mancuso1995), while the current Code of Conduct makes clear that MP ‘have a general duty to act in the interests of the nation as a whole; and a special duty to their constituents’ (House of Commons 2012: 5). Accordingly, if individuals can see clear positive benefits from certain behaviour or a specific act, conflicts of interest and breaches of the law, especially relatively minor conflicts and breaches, might be considered ethically tolerable if those who benefit are the socially marginalised. Conversely, if individuals perceive clear negative outcomes, ethical evaluations of dubious conduct may be more damning. These kinds of act‐utility considerations may be tempered further by individuals' beliefs and values about social justice – for example, a preference for the disadvantaged to receive additional benefits as a matter of priority. Previous attitudinal research into political ethics has certainly found evidence that distributional considerations matter for some individuals. Popular ethical evaluations of certain acts can be shaped by the payoffs involved, by the identity and number of other individuals affected, by the consequences for those affected by the act and by the respondent's perception of the wider context (Chibnall & Saunders Reference Chibnall and Saunders1977; Johnston Reference Johnston1986, Reference Johnston1991; Dolan et al. Reference Dolan, McKeown and Carlson1988; Frohlich & Oppenheimer Reference Frohlich, Oppenheimer, Lupia, McCubbins and Popkin2000). Meanwhile, the literature on loss‐aversion cited above also supports the notion that judgments may be affected by perceptions of outcomes.

The third norm reflects the much simpler criterion of legality. For many people, perhaps the most obvious way of understanding political ethics and especially misconduct may be in rule‐utilitarian terms – in other words, as conformity with existing laws or institutional rules. Conduct that is in breach of either is ‘wrong’; conduct that conforms to both is ‘right’ (Thompson Reference Thompson1995: 22–23). On this basis, we can hypothesise that many, if not all, individuals will judge behaviour at least in part in terms of its legality or its accordance with existing rules. This legalistic approach can in some sense be seen as minimalist, as those who employ it are relieved of the task of exercising their own independent ethical judgment; in order to evaluate a situation, they merely need to ascertain whether or not it is permitted under existing rules, regulations or laws. This approach is also potentially complicated by the fact that, in some jurisdictions, holders of certain political offices enjoy immunity from civil or criminal proceedings. In Italy and Germany, for example, constitutional provisions protect members of the national parliaments in this way, and a substantive vote is usually required by the legislature to lift this protection. In Britain, however, MPs enjoy no such immunity. As the current Code of Conduct makes clear, ‘Members have a duty to uphold the law’ (House of Commons 2012: 3). MPs, like other office holders, are always expected to adhere to the law, and we can anticipate that they are judged accordingly.

Our specific goal in this analysis is to examine the impact of political attentiveness on ethical judgments. We anticipate, first, that individuals who are attentive to and informed about public affairs are more likely to be able to apply the more nuanced norms to concrete political situations. This expectation chimes with evidence from neuropsychology that individuals' ability to generalise from everyday experience to specific political evaluations depends on attention to and knowledge of politics (Lieberman et al. Reference Lieberman, Schneider and Oschner2003; Schreiber Reference Schreiber and Neuman2007). This is because when many mental acts are practiced repeatedly, they become habitual and require less conscious attention to accomplish. Thus for those who frequently read about politics, discuss politics with friends and pay attention to political information, the norms common to political discourse become familiar, and their application to concrete situations becomes automatic (Lieberman et al. Reference Lieberman, Schneider and Oschner2003; Schreiber Reference Schreiber and Neuman2007). Working with survey data, Alvarez and Brehm also find that respondents who are better informed about politics find it easier to apply abstract values consistently to concrete situations, as ‘information makes values and predispositions relevant for beliefs about public policy issues’ (Alvarez & Brehm Reference Alvarez and Brehm2002: 50; emphasis in the original; cf. Chanley et al. Reference Chanley1994; Zaller Reference Zaller1992).

Accordingly, we hypothesise that the politically attentive are more likely than the inattentive to draw on norms pertaining to the distinctive duties of holding public office when making ethical judgments, and that they will be more sensitive to information about potential conflicts of interest, which is the primary focus of institutional ethics regulation in Britain. This is because those who absorb large amounts of political information on a regular basis are familiar with elite normative frameworks relevant to political life and apply these with relative ease to the political situations they encounter. For the same reason, we can also predict that responses to informational cues relating to the substantive outcome of politicians' behaviour will be more common among the politically attentive, as the above‐cited evidence indicates that application of such a norm to concrete situations will be easier for the attentive as well.

Second, there is reason to believe that for most respondents, including the non‐attentive, considerations of legality will have particular resonance. The rule that legal acts are acceptable and illegal acts are unacceptable has many of the characteristics of a heuristic or cognitive shortcut of the type generally employed in peripheral processing (Popkin Reference Popkin1991; Sniderman et al. Reference Sniderman, Brody and Tetlock1991). If this is the case, then we might expect to see the non‐attentive respond more readily to informational cues that tap legal norms than they would to cues tapping either of the other two norms.

A final prediction we can make is that, as Zaller (Reference Zaller1992) and Alvarez and Brehm (Reference Alvarez and Brehm2002) note, political sophisticates are more consistent in the responses they give to pollsters. Following this reasoning, we can anticipate that the politically attentive may be somewhat more adept at applying all three norms consistently to concrete political situations.

Experimental design and data

The role of norms in framing individuals' ethical judgments is examined here through the analysis of experimental data incorporated into a 2009 survey in the United Kingdom. Footnote 13 Embedded in the survey was a 2×2×2 factorial vignette designed to operationalise the three norms we predict to be associated with judgments of the behaviour of political elites.

Survey experiments based on vignettes combine the internal validity inherent in experiments with the external validity of sample surveys (Gibson Reference Gibson2008; Sniderman & Grob Reference Sniderman and Grob1996). They are particularly useful for the analysis of social judgments, which is the context in which the technique was originally developed by sociologists (Rossi & Anderson Reference Rossi, Anderson, Rossi and Nock1982). Moreover, this technique has been used in previous research to analyse framing effects (Kinder & Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1990; Sniderman & Grob Reference Sniderman and Grob1996). The vignette‐based experiment is therefore an ideal tool to analyse how informational cues condition evaluations of political elites and thus which normative frameworks respondents draw on when making their judgments.

The experimental vignette employed in this analysis took nine versions, one of which was a control treatment describing the following scenario involving a fictitious politician Susan Barnes: ‘MP Susan Barnes helps a firm whose headquarters is in her constituency.’ The eight other versions of the vignette were treatments reflecting permutations of the three norms set out above. Each of these was embodied in two versions of a piece of qualifying information that served as a cue. In one version, Barnes acts in a manner consonant with the established norm in question – avoiding conflicts of interest (the conflict‐of‐interest norm), acting in accordance with the law (the legality norm) and delivering a tangible benefit for constituents (the public‐benefit norm) – and in the other version she violates the norm in question. Footnote 14

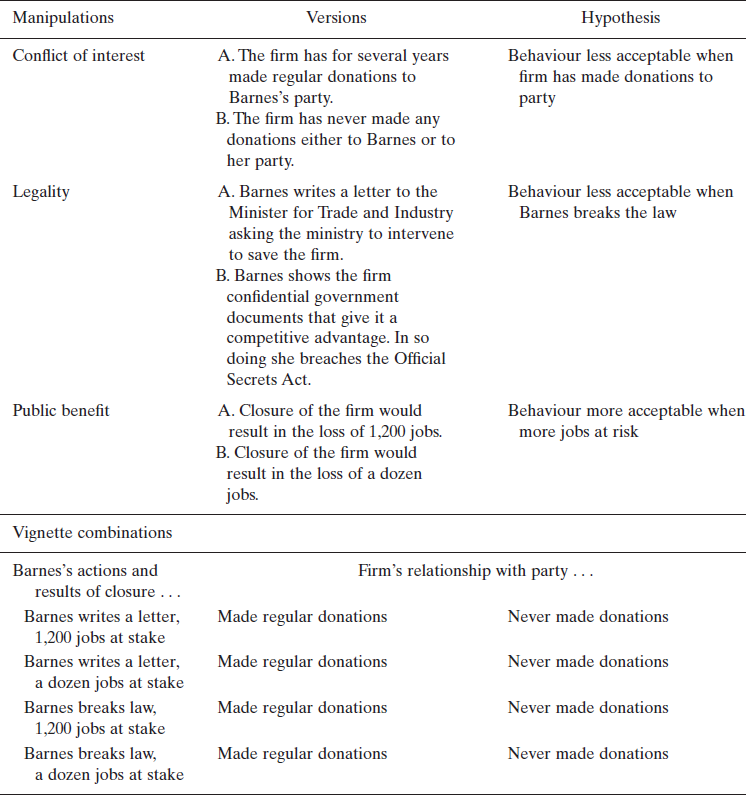

The conflict‐of‐interest statements were crafted so that one version of the vignette (version A in Table 1) reflects the absence of any obvious conflict of interest: ‘The firm has never made any donations either to Barnes or to her party’, whereas the other (version B) implied conflict of interest: ‘The firm has for several years made regular donations to Barnes's party.’

Table 1. Structure of vignette experimental manipulations (MP Susan Barnes helps a firm whose headquarters is in her constituency …)

The law‐conformity statements were designed so that one version (A) describes conventional representative behaviour by British MPs, which suggests that the action in question conforms to rules to which politicians are subject: ‘Barnes writes a letter to the Minister for Trade and Industry asking the ministry to intervene to save the firm.’ The other version (B) signals clear law‐breaking: ‘Barnes shows the firm confidential government documents that give it a competitive advantage. In so doing she breaches the Official Secrets Act.’

The first version (A) of the public‐benefit statement described an outcome that suggested the action taken might potentially be justified on the basis of its social consequences: ‘Closure of the firm would result in the loss of 1,200 jobs.’ The second version (B) suggested that the action would result in minimal social benefit: ‘Closure of the firm would result in the loss of a dozen jobs.’

The details of each version of the vignette are summarized in Table 1. Footnote 15 Each respondent was randomly assigned to receive one of the nine versions of the vignette.

Respondents were then asked to judge Barnes's behaviour by means of the following question:

Please indicate your opinion about Barnes's help for the firm using this 0 to 10 scale.

The wording of this question was designed to elicit what might be termed an ‘everyday’ ethical response to the action in question. A higher score on this question reflects as straightforwardly as possible the perception of normative unacceptability or disapprobation. Many previous studies that have asked respondents to judge the propriety of politicians' actions and certain types of conduct have used questions that explicitly refer to ‘corruption’ (Allen Reference Allen2008; Atkinson & Mancuso Reference Atkinson and Mancuso1985; Jackson & Smith Reference Jackson and Smith1996; Johnston Reference Johnston1986). Corruption is a morally loaded concept, however, which means different things to different people. Since levels of political attentiveness may well affect how the term is understood, we avoid it in the present study. Footnote 16

Results

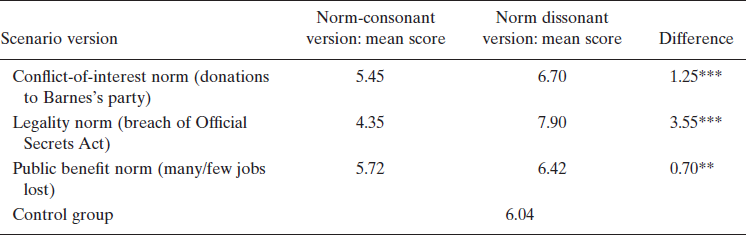

The mean normative approbation scores for each version of the vignette are displayed in Table 2. Footnote 17 The figures in this table demonstrate that all three of the manipulations had the expected effect. Respondents who received ‘negative’ versions of the vignette were more likely to judge the actions of Barnes to have been unacceptable, and the differences in means are in all cases significant at the 0.01 level or higher.

Table 2. Effects of vignette manipulations on corruption perceptions

Notes: Cell entries are mean responses for treatment groups. Higher scores indicate respondents found vignette less acceptable. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

The results suggest that all three of the norms – avoiding conflicts of interest, abiding by the law and delivering a public benefit – play a role in shaping ethical evaluations of politicians' conduct. Interestingly, even those respondents given the ‘positive’ versions of the vignettes had fairly jaundiced views of the behaviour of the fictional Barnes, indicating that people are generally inclined to judge critically situations with even a whiff of ethical dubiety. Those harsh judgments are clearly exacerbated, however, by cues which tend to confirm the notion that the MP had behaved wrongly. Most important from our perspective is the fact that respondents' views appear to respond systematically to the norms embodied in the manipulations.

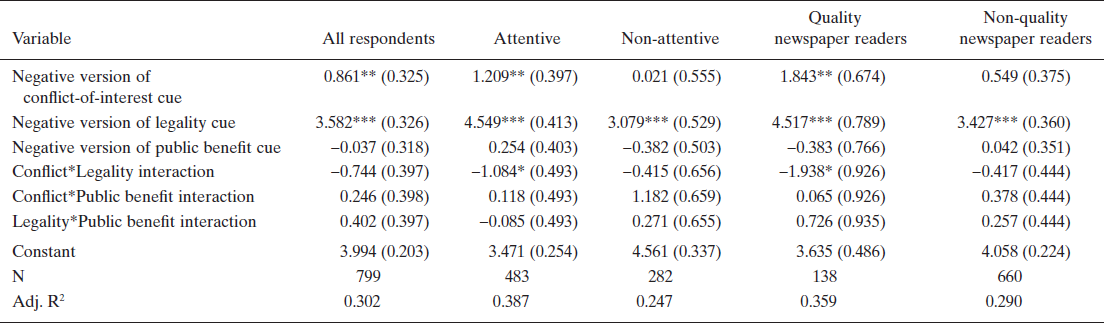

The impact of the manipulations can be probed in greater depth through multivariate analysis, which takes acceptability perceptions as a dependent variable (see Table 3). Respondents were coded as to whether they received a ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ version of each vignette, and these codings were used to create independent variables. Specifically, the ‘negative’ versions of each manipulation were entered into an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model, together with the interactions between them (as is conventional in analyses of factorial vignettes). The basic model is presented in the second column of Table 3.

Table 3. Variation in judgments of acceptability/unacceptability: Ordinary least squares regressions

Note: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; standard errors in parentheses.

The regression results refine the understanding gained through bivariate analysis above; the conflict‐of‐interest and legality manipulations have statistically significant impacts on judgments of political behaviour, with the substantive‐outcome manipulation having no perceptible influence. Tellingly, the legality manipulation has by far the largest coefficient and is most strongly significant. This suggests that when an act is framed in terms of law‐breaking, this sends a very strong signal to members of the public that it is unacceptable, regardless of the other contextual information with which they are presented. The impact of the informational cue based on conflict‐of‐interest norms is also significant, but of considerably lesser magnitude and lower significance. The non‐significance of the public‐benefit variable is somewhat puzzling given the strong tradition of constituency service in Britain; this could potentially be due to the peculiarities of vignette design (the difference between the loss of 1,200 and 12 jobs might not have had sufficient resonance for most people), or it could be that the substantive outcomes of politicians' behaviour are genuinely not as relevant to people as is conformity to procedural norms, as suggested by some literature on legitimacy (Major & Schmader Reference Major, Schmader, Jost and Major2001; Tyler Reference Tyler, Jost and Major2001).

A caveat is in order here, however. The nature of vignette‐based survey experiments is such that it is not possible to compare directly across manipulations and thus compare the impacts of the different norms they are designed to operationalise. The wording of vignettes is by definition highly idiosyncratic, such that it is virtually impossible to design manipulations with precisely equivalent impacts. Further research employing a different research design would be necessary to probe the weakness of the public‐benefit frame in comparison to the framing effects of the legality and conflict‐of‐interest norms. The research design employed here does allow us to compare the impact of each norm across subcategories of respondent, however, and it is to this that we now turn.

As noted above, we are primarily interested in investigating the impact of political attentiveness on how culturally embedded norms impact on moral judgments. Political attentiveness was operationalised for this purpose by means of a variable designating attentiveness to ‘what is going on in government and public affairs’, which we expect to be associated with a greater propensity to understand impropriety in terms of conflict‐of‐interest and public‐benefit norms. To test this and the other hypotheses outlined above, the sample was divided into highly attentive and less attentive groups, Footnote 18 and the regression was run on the two sub‐groups. The third and fourth columns of Table 3 present these models.

The main effects in this model show that when judging the acceptability of Barnes's behaviour, the minority of the sample (approximately a third of the total) who claimed to be highly attentive to public affairs responded to cues related to legality as well as those designed to reflect the presence or absence of a conflict of interest, as expected by our understanding of the role of political attentiveness in conditioning ethical judgments. In contrast, the non‐attentive responded to legal norms alone. This finding suggests that, as expected, normative concerns about conflicts of interest have resonance mainly for that portion of the public which is highly attuned to politics. Considerations about legality or rule‐compliance, by contrast, would appear to serve as a convenient rule of thumb that enables even the non‐attentive to judge a situation. The results for the public‐benefit norm were again not significant for either group.

Analysis of the interaction term in this model enables us further to refine our understanding of the relative importance of the different norms. The negatively signed coefficient on the interaction between conflict of interest and legality demonstrates that when an action is illegal, the impact of conflict‐of‐interest considerations is virtually obliterated. In other words, legality ‘trumps’ conflict of interest, suggesting a hierarchical ordering of norms in the minds of the attentive: the most important consideration is whether or not an action is legal, and only when it is legal (or there is no indication that it is not legal) does the conflict‐of‐interest norm come into play. Footnote 19

In order to probe the data further, we also segmented them according to actual (as opposed to reported) attentiveness. For this purpose we chose an indicator of newspaper readership, from which we constructed a dummy variable designating readership of what are commonly referred to in Britain as ‘quality’ newspapers (see online supplementary material for details). These are newspapers that are held to adhere to relatively high journalistic standards and to report news stories in depth (Kuhn Reference Kuhn2007). We assume that most people derive most of their knowledge of political elites from news sources. The specific sources into which they tap can thus be expected to be one of the main determinants of their degree of awareness of the details of political life. In addition, newspaper consumption is far more likely to reflect a conscious choice than the consumption of broadcast news, which may well depend on fortuitous factors.

Given the considerable diversity in news coverage among newspapers, it stands to reason that those who read ‘quality’ newspapers should have a more nuanced appreciation of elite‐level ethical norms, including preoccupations with conflicts of interest, than those who derive their information from other sources. And this is precisely what we find. The fifth column in Table 3 reports a model based on readers of ‘quality’ papers alone. Though this is a small sample – representing approximately 17 per cent of the total – we nevertheless obtain strongly significant results on our core variables of interest. The impact of the legality manipulation remains the strongest of the three informational cues, but we see that the conflict‐of‐interest cue is also of considerable magnitude and significance in this model. The public‐benefit cue remains non‐significant. As in the model of self‐identified ‘attentive’ respondents, the significant negative coefficient on the interaction terms between conflict of interest and legality suggests that the presence of a conflict of interest only becomes a relevant consideration for respondents when legality is not at stake. The final column of this table contains a model based on those respondents who did not report reading ‘quality’ newspapers. As can be readily ascertained, the conflict‐of‐interest cue is far from being significant in this model.

These findings suggest that the information to which people are exposed plays an important role in conditioning their attitudes toward the actions of politicians. Though the legality of an action appears to have universal resonance, conformity to norms specific to the public role of politicians conditions reactions only among the small minority of the population that is highly attentive to politics and consumes quality newspapers. And even among the attentive this norm only kicks in when legality is not at stake. That norms commonly deployed in elite discourse should be an important consideration for such a small sector of the population poses serious questions for the assumptions subtending a range of theoretical and practical approaches that have been taken to the question of political ethics.

Discussion and conclusion

Our findings indicate that people are critical of politicians, but they are not blindly critical. When judging behaviour they respond to contextual information in ways that are consistent with norms embodied in political culture, and they respond largely in the ways we would expect on the basis of common understandings of political ethics. However, most do not respond in the ways prescribed by theoretical accounts of public ethics. In particular, concerns with avoiding conflicts of interest may under certain circumstances shape the evaluations of those who are attentive to politics, but simple considerations of legality appear to weigh more heavily for the less attentive. And even among the attentive, legality ‘trumps’ the more nuanced conflict‐of‐interest norm.

These findings have significant implications for both theoretical and practical approaches to political ethics, which have largely ignored research in political psychology. Normative accounts of political ethics and the institutional regulation of political ethics are conducted largely on the basis of role‐specific understandings of proper behaviour by those in public life. Politicians have a public trust, which means that they are bound to put the public good above their own private interests and to avoid conflict‐of‐interest situations where possible in the execution of their public duties. This sort of argument appears to have very little resonance with large section of the general public, however, when responding to information about political conduct. Our findings suggest that the way in which elites understand and deal with ethical matters pertaining to politics is at some remove from the way in which the majority of the public approaches these issues. This gap could go some way toward explaining why the solutions proposed by elites to declining trust in politicians are very often unsuccessful.

These findings are also relevant for the debate as to whether rules or culture are better means of ensuring high ethical standards among politicians (Atkinson & Mancuso Reference Atkinson and Mancuso1985; Committee on Standards in Public Life 1995; Flinders Reference Flinders2012; Riddell Reference Riddell2011). Our results suggest that statutory regulation is a more robust means of keeping politicians on the perceived straight‐and‐narrow than non‐binding codes of conduct or general principles of appropriate behaviour. If most people employ the evaluative short‐cut of rule‐compliance as a means of judging politicians, then it follows that relevant norms need to be embodied in rules, and these rules need to be enforced.

The results of this article are of particular relevance to Britain, which is the empirical focus of the analysis. Given the nature of contemporary media coverage of British politicians' real and alleged indiscretions, it is not surprising that so many sections of the British public take a generally dim view of their politicians' integrity (Allen & Birch Reference Allen and Birch2011; Birch & Allen Reference Birch and Allen2010). Widespread ethics reforms such as those undertaken in Britain at several points since the 1990s have done little to improve confidence in elected politicians. There is even some evidence to suggest that recent increases in transparency may actually have fuelled suspicion rather than alleviating it (Newell Reference Newell2008). The analysis presented here sheds light on why this might have been the case, as it identifies a worrying gap between elite and mass understandings of political ethics. This finding suggests that greater emphasis could profitably be placed on role‐specific political norms in citizenship education and other educational initiatives designed to instill democratic values in young people.

The results will also be of interest to political psychologists in that virtually all of the political psychology research on which we draw in developing our theoretical expectations has been carried out in the United States on American subjects. It will be of value to political psychologists to see that their findings hold also in the United Kingdom, despite the cultural differences between the two settings.

Finally, this article has shown that survey experiments provide a fruitful means of probing patterns of ethical judgments of politicians. Further research could usefully explore the stability of such evaluations over time, and their sensitivity to other types of contextual cues.

Acknowledgements

This article was made possible by support from the Economic and Social Research Council (grant number RES‐000‐22‐3459) and British Academy (grant number SG‐52322). We are also grateful for the comments and advice of the participants at the various conferences and seminars at which earlier versions of the article were presented, including those organised by the American Political Science Association, the Political Studies Association and the European Consortium for Political Research General Conference. In addition, we thank Raymond Duch, Philip Habel, Howard Lavine and Paul Whiteley, as well as the reviewers and editors of the European Journal of Political Research for their useful comments and suggestions. We take full responsibility for any remaining errors of fact or interpretation.

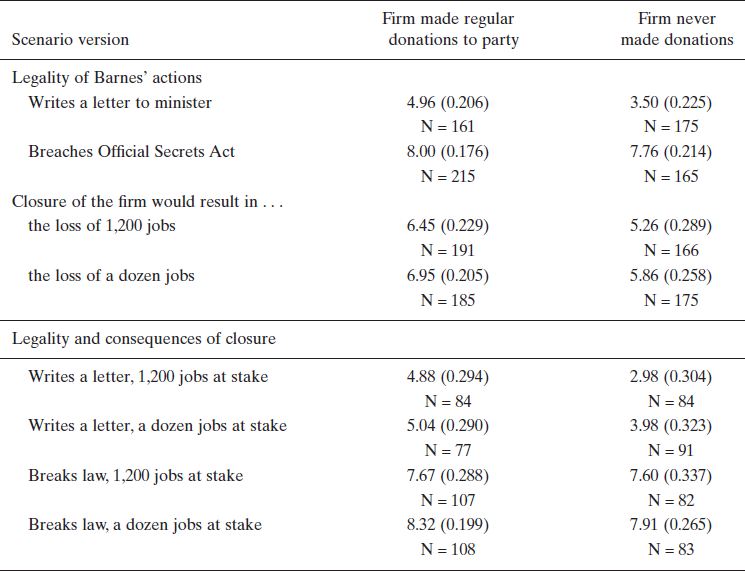

Appendix: Detailed permutation of experimental results

Appendix Table 1. Effects of scenario characteristics on reaction to vignette (Question: How acceptable/unacceptable?)

Notes: Mean responses for treatment groups. Higher scores indicate respondents found vignette more unacceptable and lower scores indicate that respondents found the vignette more acceptable. Values in parentheses are standard errors.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site:

Supplementary material: Survey question wording and variable construction Vignette wording