Introduction

Weed interference remains one of the most significant constraints to achieving optimum corn yields (Soltani et al. Reference Soltani, Dille, Burke, Everman, VanGessel, Davis and Sikkema2016, Reference Soltani, Geddes, Laforest, Dille and Sikkema2022). Weeds compete with corn for light, water, nutrients, and space, and early-season weed interference can significantly reduce corn yield (Kaur et al. Reference Kaur, Kaur and Chauhan2018; Rana Reference Rana and Rana2016; Reddy Reference Reddy2018). In Ontario and much of the North Central United States, key problematic weeds in corn production include broadleaf species such as velvetleaf, green pigweed, common ragweed, and common lambsquarters, as well as grass species such as barnyardgrass and green foxtail (OMAFRA 2024). Effective control of these species with preemergence herbicides is critically necessary for minimizing corn yield loss from early-season weed interference and for improving the efficacy of postemergence herbicides by reducing weed density and size at the time of postemergence herbicide application. Moreover, combining multiple herbicides helps lower the selection intensity for the evolution of herbicide-resistant weed populations (Owen Reference Owen2016). In Canada, no new herbicide mode of action has been registered for corn production in more than 25 yr. As a result, corn growers urgently need new herbicide options to effectively manage challenging weed species in their cropping systems.

Diflufenican is a selective herbicide belonging to the phenyl ether family and is categorized as a Group 12 herbicide by the Weed Science Society of America (WSSA). Diflufenican has both contact and residual activity against key weeds and has long been used in European agriculture, particularly for weed control in cereal and pulse crops such as lentils (Effertz Reference Effertz2021). In North America, diflufenican represents a novel mode of action for major crops; it was recently registered for use in Canada by the Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) in February 2024 for preplant and preemergence weed control in corn and soybean production (PMRA 2024a) and is currently under review by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA 2025) for potential registration for use in corn and soybean.

The introduction of diflufenican into North American crop production for weed management in corn and soybean is significant, because no other WSSA Group 12 herbicide is registered for use on these crops (Effertz Reference Effertz2021). Diflufenican is registered for use in Canada either preplant or preemergence for the control of redroot pigweed, green pigweed, waterhemp, and Palmer amaranth (PMRA 2024a), The preformulated mixture of isoxaflutole + diflufenican is registered for the control of five annual grasses and 14 annual broadleaf weeds in Canada (PMRA 2024b). The co-application of diflufenican with other herbicides has demonstrated effectiveness against a range of annual grass and broadleaf weeds, particularly when included in mixtures with herbicides that possess complementary modes of action (Effertz Reference Effertz2021; Haynes and Kirkwood Reference Haynes and Kirkwood1992; Tejada Reference Tejada2009).

Diflufenican is absorbed primarily through the shoots of emerging seedlings, with minimal systemic movement within the plant (Haynes and Kirkwood Reference Haynes and Kirkwood1992). Diflufenican is a phytoene desaturase inhibitor that prevents carotenoid biosynthesis, thereby depriving chlorophyll of its protective pigments. By interfering with this process, diflufenican causes the accumulation of phototoxic intermediates, leading to photobleaching, cellular damage, and eventual plant death under light exposure (Haynes and Kirkwood Reference Haynes and Kirkwood1992; Miras-Moreno et al. Reference Miras-Moreno, Pedreño, Fraser, Sabater-Jara and Almagro2019). From environmental and toxicological perspectives, diflufenican exhibits several favorable characteristics (Bending et al. Reference Bending, Lincoln and Edmondson2006). It has low water solubility and minimal volatility, which reduces the risk of off-target movement. Additionally, it has low toxicity to non-target organisms such as mammals and pollinators, including honeybees, and it degrades relatively quickly in soil, thereby limiting its persistence in the environment (Ashton et al. Reference Ashton, Abulnaja, Pallett, Cole and Harwood1994; Bending et al. Reference Bending, Lincoln and Edmondson2006).

Isoxaflutole is widely used in corn production for the control of a broad range of weed species, and can be applied preplant, preemergence, or early postemergence (Grichar et al. Reference Grichar, Besler and Palrang2005; Sprague Reference Sprague1999). Isoxaflutole inhibits 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase following rapid transformation within the plant to form a biologically active diketonitrile metabolite (Bayer 2017; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Prisbylla, Cromartie, Dagarin, Howard, Provan, Ellis, Fraser and Mutter1997; Pallett et al. Reference Pallett, Little, Sheekey and Veerasekaran1998). This metabolite interferes with the biosynthesis of plastoquinone, a critical component in carotenoid production (Pallett et al. Reference Pallett, Little, Sheekey and Veerasekaran1998). As a result, treated weeds exhibit bleaching symptoms followed by tissue death (Bayer 2017; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Prisbylla, Cromartie, Dagarin, Howard, Provan, Ellis, Fraser and Mutter1997; Pallett et al. Reference Pallett, Little, Sheekey and Veerasekaran1998; Sprague Reference Sprague1999). Isoxaflutole is particularly effective against broadleaf weeds and suppresses some grass species (Sprague Reference Sprague1999; Steckel et al. Reference Steckel, Simmons and Sprague2003). Its residual activity and broad-spectrum efficacy make it a reliable herbicide option for weed management in corn (Bayer 2017; Pallett et al. Reference Pallett, Little, Sheekey and Veerasekaran1998; Shaner Reference Shaner2014). However, its performance can be inconsistent against certain small-seeded grasses, such as green foxtail and barnyardgrass, with control often influenced by application rate, soil characteristics, and rainfall after application (Smith Reference Smith2019; Sprague Reference Sprague1999; Steckel et al. Reference Steckel, Simmons and Sprague2003).

Limited data exists on the weed control efficacy of diflufenican in corn and its enhanced weed control when co-applied with isoxaflutole. Diflufenican and isoxaflutole offer different spectrums of activity and modes of action against key problematic weeds, thus the co-application of these herbicides may increase the spectrum of weeds that can be controlled, extend their residual activity, and reduce the evolution of herbicide-resistant biotypes. Herbicide mixtures with multiple effective modes of action are a cornerstone of integrated weed management strategies by helping to delay the onset of resistance in weed populations (Ofosu et al. Reference Ofosu, Agyemang, Márton, Pásztor, Taller and Kazinczi2023; Owen Reference Owen2016). Additionally, there is limited information on the interaction between isoxaflutole and diflufenican for the control of troublesome weeds under Ontario field conditions. It remains unclear whether the co-application of isoxaflutole and diflufenican results in antagonistic, additive, or synergistic interactions across common annual broadleaf and grass weed species in Ontario corn production, and the effects of these combinations on corn safety and yield performance have not been well documented. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to 1) assess the effectiveness of isoxaflutole, diflufenican, and their combination applied preemergence at various rates for the control of common annual broadleaf and grass weed species; and 2) determine the effects of these treatments on corn injury and grain yield.

Materials and Methods

Field experiments were carried out in 2019 at the Huron Research Station in Exeter, Ontario (43.315497°N, 81.887765°W), and in both 2018 and 2019 at the University of Guelph campus in Ridgetown, Ontario (42.448644°N, 81.510569°W). The soil at Exeter was classified as Brookston clay loam, consisting of 29% sand, 44% silt, 27% clay, and 4.5% organic matter, pH 7.8. At Ridgetown, the soil was Fox sandy loam. In 2018, it contained 33% sand, 34% silt, 33% clay, and 3.8% organic matter, pH 6.7. In 2019, the composition was 41% sand, 28% silt, 31% clay, and 4.0% organic matter, pH 7.1. Prior to planting, all sites were prepared using fall mouldboard plowing, followed by two spring passes with a field cultivator with rolling basket harrows to create a suitable seedbed.

The field experiments were established using a randomized complete block design with four replications. Treatments included a nontreated control, three rates of isoxaflutole (Balance Flexx) applied preemergence at 52.5, 79, and 105 g ai ha−1 and three rates of diflufenican applied preemergence at 75, 105, and 150 g ai ha−1. In addition, combinations of isoxaflutole and diflufenican were applied preemergence at corresponding rates of 52.5 + 75, 79 + 105, and 105 + 150 g ai ha−1. Each plot measured either 8 or 10 m long and 3 m wide, consisting of four corn rows spaced 0.75 m apart. Glyphosate- and glufosinate-resistant corn hybrids (DKC 53-56, DS79C56, or PIONEER P9998AM) were seeded at approximately 85,000 plants per hectare.

Herbicides were applied 1 to 3 d after seeding using a CO2-pressurized backpack sprayer calibrated to deliver 200 L ha−1 at 240 kPa. The spray boom was 1.5 m wide and fitted with four ULD120-02 nozzles (Hypro; Pentair, New Brighton, MN), spaced 50 cm apart to produce a 2 m spray pattern.

Visible assessments of crop injury were conducted at 1, 2, 4, and 8 wk after corn emergence (WAE), while visible weed control was evaluated at 2, 4, and 8 wk after treatment application (WAT). Both types of evaluations used a percentage scale ranging from 0% (no injury or weed suppression) to 100% (complete plant death). At harvest maturity, the center two rows in each plot were harvested using a small-plot combine. Grain yield and moisture content were recorded; yield data were adjusted to a standard moisture level of 15.5% prior to statistical analysis.

Data analysis was carried out using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS software (v.9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and the level of significance threshold for hypothesis testing was α = 0.05. The generalized linear mixed model included herbicide treatment as the fixed effect and environment (year-location combinations), environment by herbicide treatment, and replicate within environment as the random effects. The Gaussian distribution best satisfied the assumptions of analysis, and all weed control evaluations, except velvetleaf control, which were arcsine square root transformed prior to analysis; these means were back-transformed for presentation. Treatments for a given variable with a value of zero and zero variance across environments were excluded from the analysis. Comparisons between these treatments and non-zero treatments were made using the P-value included in the LSMEANS output table.

Expected values of visible percent control for herbicide mixture treatments were compared to observed values using a two-sided t-test for the purpose of determining additive, synergistic, or antagonistic effects. If the t-test was nonsignificant, the effect of the herbicide combination in the mixture was additive. If the observed percent control was higher than expected, the effect was considered synergistic. Conversely, if the observed percentage control was lower than expected, the effect was considered antagonistic. Colby’s equation was used to calculate expected values for the mixture treatments (Colby Reference Colby1967):

where E is the expected weed control for the herbicide mixture, and X and Y are the weed control with the two individual herbicides.

Results and Discussion

The predominant weed species present at the study sites were velvetleaf, green pigweed, common ragweed, common lambsquarters, barnyardgrass, and green foxtail.

Velvetleaf Control

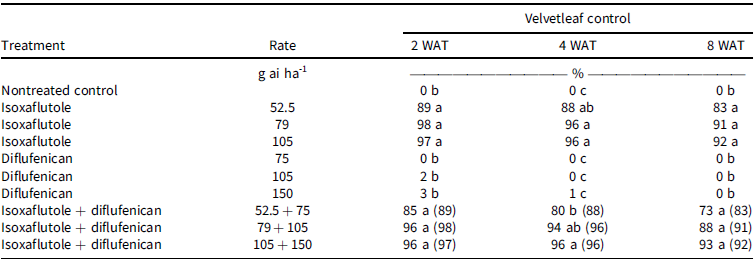

Isoxaflutole applied preemergence at 52.5, 79, and 105 g ai ha−1 provided 83% to 89%, 91% to 98%, and 92% to 97% velvetleaf control at 2, 4, and 8 WAT, respectively (Table 1). Diflufenican applied preemergence at 75, 105, and 150 g ai ha−1 controlled velvetleaf by ≤3%. A mixture of isoxaflutole and diflufenican applied preemergence improved velvetleaf control compared with diflufenican alone but control was equivalent to that of isoxaflutole applied alone (Table 1). There were no antagonistic or synergistic interactions between isoxaflutole and diflufenican applied preemergence at the tested rates for velvetleaf control; all interactions were additive (Table 1).

Table 1. Velvetleaf control with isoxaflutole and diflufenican alone or in combination, applied preemergence to corn at Ridgetown in 2018 and 2019.a–d

a Abbreviation: WAT, weeks after herbicide application.

b Expected values for control with herbicide combinations based on Colby’s equation (Eq. 1) are shown in parentheses following observed values.

c Means were separated according to the Tukey-Kramer multiple range test at α = 0.05.

In other studies, Effertz (Reference Effertz2021) reported that diflufenican applied preemergence at rates of 18.75, 37.5, and 75 g ai ha−1 provided velvetleaf control of 17% to 51%, 13% to 60%, and 23% to 77%, respectively. When isoxaflutole was applied preemergence at 13.13, 26.25, and 52.5 g ai ha−1 velvetleaf control was 85% at the lowest rate, and to up to 99% at all three rates (Effertz Reference Effertz2021). When applied in combination, diflufenican + isoxaflutole at 18.75 + 13.13, 37.5 + 26.25, and 75 + 52.5 g ai ha−1 provided even greater control, ranging from 93% to 99% (Effertz Reference Effertz2021). Bhowmik et al. (Reference Bhowmik, Kushwaha and Mitra1999) reported that isoxaflutole applied at 6.1 g ai ha−1 reduced velvetleaf biomass by 80% (ED80), a significantly lower rate than the rates used in this study. However, Knezevic et al. (Reference Knezevic, Sikkema, Tardif, Hammill, Chandler and Swanton1998) reported a much higher ED80 of 90 g ai ha−1 for velvetleaf control. Sprague et al. (Reference Sprague, Kells and Penner1999) reported similar levels of velvetleaf control to those in this study when isoxaflutole was applied at rates of 79 and 105 g ai ha−1. Similarly, Smith (Reference Smith2019) reported comparable results to the results of the current study, showing that preemergence applications of isoxaflutole at 52.5, 79, and 105 g ai ha−1 provided 82% to 95%, 96% to 98%, and 93% to 100% control of velvetleaf, respectively.

Green Pigweed Control

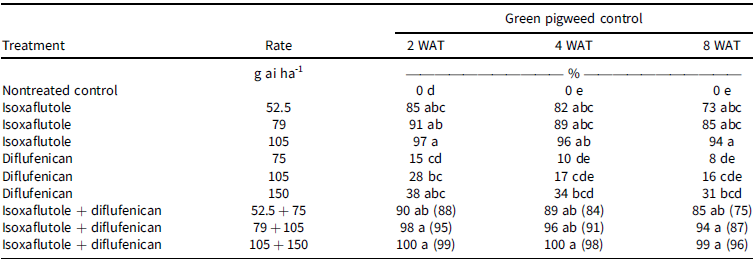

Isoxaflutole applied preemergence at 52.5, 79, and 105 g ai ha−1 provided 85%, 91%, and 97% control of green pigweed at 2 WAT. When assessed at 8 WAT, control levels dropped to 73%, 85%, and 94%, respectively, for those same application rates (Table 2). Diflufenican applied preemergence at 75, 105, and 150 g ai ha−1 provided ≤38% control of green pigweed. Control improved significantly when the isoxaflutole + diflufenican combination was applied preemergence, with the highest rate combination providing 99% to 100% control; however, control was statistically similar to that of isoxaflutole applied alone (Table 2). No antagonistic or synergistic interactions with isoxaflutole and diflufenican applied preemergence were observed at the rates tested; all interactions were additive (Table 2). Lower-than-expected green pigweed control with diflufenican treatments may be due to environmental conditions or biotype variability, which underscores the need to integrate diflufenican with other management practices.

Table 2. Green pigweed control with isoxaflutole and diflufenican alone or in combination, applied preemergence to corn at Ridgetown in 2018 and 2019.a–c

aAbbreviation: WAT, weeks after herbicide application.

bExpected values for control with herbicide combinations based on Colby’s equation (Eq. 1) are shown in parentheses following observed values.

cMeans were separated according to the Tukey-Kramer multiple range test at α = 0.05.

In previous studies, Effertz (Reference Effertz2021) reported that preemergence applications of diflufenican at rates of 18.75, 37.5, and 75 g ai ha−1 controlled redroot pigweed 73% to 99%, 97% to 99%, and 98% to 99%, respectively. Isoxaflutole applied preemergence at 13.13, 26.25, and 52.5 g ai ha−1 provided, respectively, 88% to 99%, 96% to 98%, and 99%, control of redroot pigweed (Effertz Reference Effertz2021). When applied in combination, diflufenican + isoxaflutole at 18.75 + 13.13, 37.5 + 26.25, and 75 + 52.5 g ai ha−1 controlled redroot pigweed by 98% to 99% (Effertz Reference Effertz2021). Smith (Reference Smith2019) found that preemergence applications of isoxaflutole at 52.5, 79, and 105 g ai ha−1 provided 34% to 87%, 56% to 98%, and 69% to 99% control of pigweeds, respectively. Similarly, Sprague et al. (Reference Sprague, Kells and Penner1999) reported up to 88% control of pigweed in corn with isoxaflutole applications of 79 and 105 g ai ha−1. Knezevic et al. (Reference Knezevic, Sikkema, Tardif, Hammill, Chandler and Swanton1998) observed that an ED90 of 100 g ai ha−1 was required to effectively reduce pigweed biomass.

Common Ragweed Control

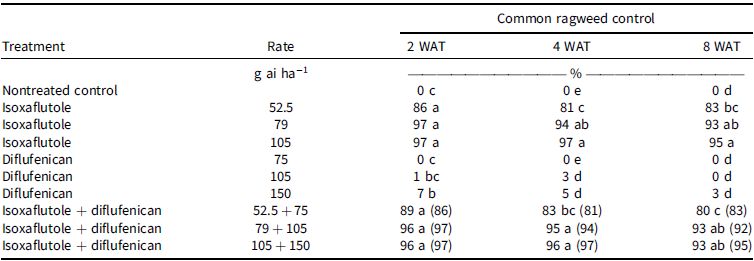

Isoxaflutole applied preemergence at 52.5, 79, and 105 g ai ha−1 provided 86%, 97%, and 97% control of common ragweed at 2 WAT, respectively. When assessed at 8 WAT, control was determined to be 83%, 93%, and 97%, respectively, for those application rates (Table 3). In contrast, diflufenican applied preemergence at 75, 105, and 150 g ai ha−1 was ineffective, providing ≤7% control at 2 WAT at the highest rate of the herbicide, and only 3% control at 8 WAT. The preemergence co-application of isoxaflutole + diflufenican improved common ragweed control compared with diflufenican alone but control levels were similar to those of isoxaflutole applied alone (Table 3). There were no antagonistic or synergistic interactions with isoxaflutole and diflufenican applied preemergence; all interactions were additive (Table 3).

Table 3. Common ragweed control with isoxaflutole and diflufenican alone or in combination, applied preemergence to corn at Ridgetown in 2018 and 2019, and Exeter in 2018.a–c

aAbbreviation: WAT, weeks after herbicide application.

bExpected values for control with herbicide combinations based on Colby’s equation (Eq. 1) are shown in parentheses following observed values.

cMeans were separated according to the Tukey-Kramer multiple range test at α = 0.05.

Results from this study are comparable to those reported by Smith (Reference Smith2019) that preemergence applications of isoxaflutole at 52.5, 79, and 105 g ai ha−1 provided 97%, 82% to 100%, and 93% to 100% control of common ragweed, respectively. Similarly, Sprague et al. (Reference Sprague, Kells and Penner1999) observed greater than 95% control of common ragweed with preemergence applications of isoxaflutole at 79 and 105 g ai ha−1.

Common Lambsquarters Control

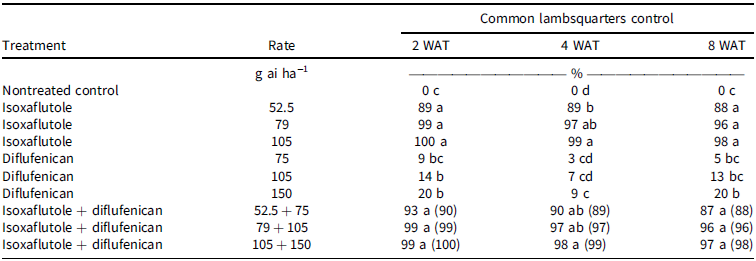

Isoxaflutole applied preemergence at 52.5, 79, and 105 g ai ha−1 provided, respectively, 89%, 99%, and 100% control of common lambsquarters at 2 WAT; and 88%, 96%, and 98% control at those respective rates when assessed at 8 WAT (Table 4). Diflufenican applied preemergence at 75, 105, and 150 g ai ha−1 provided ≤20% control. Control improved when isoxaflutole + diflufenican was applied preemergence compared with diflufenican alone, but the control was similar to that when isoxaflutole was applied alone (Table 4). There were no antagonistic or synergistic interactions between isoxaflutole and diflufenican when applied preemergence in these experiments; all interactions were additive (Table 4).

Table 4. Common lambsquarters control with isoxaflutole and diflufenican alone or in combination, applied preemergence to corn at Ridgetown in 2018 and 2019, and Exeter in 2018.a–c

aAbbreviation: WAT, weeks after herbicide application.

bExpected values for control with herbicide combinations based on Colby’s equation (Eq. 1) are shown in parentheses following observed values.

cMeans were separated according to the Tukey-Kramer multiple range test at α = 0.05.

In studies with isoxaflutole, Bhowmik et al. (Reference Bhowmik, Kushwaha and Mitra1999) reported that the calculated dose to reduce common lambsquarters biomass by 80% (ED80) was only 13 g ai ha−1, suggesting that the species is highly susceptible to isoxaflutole. However, Knezevic et al. (Reference Knezevic, Sikkema, Tardif, Hammill, Chandler and Swanton1998) reported that a broader ED80 range of isoxaflutole (60 to 130 g ai ha−1) is needed to control common lambsquarters, indicating that some variability in sensitivity exists.

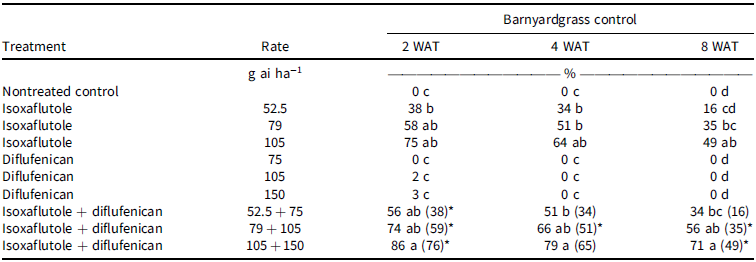

Barnyardgrass Control

Isoxaflutole applied preemergence at 52.5, 79, and 105 g ai ha−1 provided 38%, 58%, and 75% control of barnyardgrass at 2 WAT, respectively. When assessed at 8 WAT, control was 16%, 35%, and 49% at those rates (Table 5). In contrast, diflufenican applied preemergence at 75, 105, and 150 g ai ha−1 was essentially ineffective, providing ≤3% control. Isoxaflutole + diflufenican provided better barnyardgrass control than diflufenican alone but it was similar to that of isoxaflutole applied alone. There was a synergistic improvement in the control of barnyardgrass with isoxaflutole + diflufenican at 52.5 + 75 g ai ha−1 at 2 WAT; 79 + 105 g ai ha−1 at 2, 4, and 8 WAT; and 105 + 150 g ai ha−1 at 2 and 8 WAT; all other interactions were additive (Table 5).

Table 5. Barnyardgrass control with isoxaflutole and diflufenican alone or in combination, applied preemergence to corn at Ridgetown in 2018 and 2019.a–d

aAbbreviation: WAT, weeks after herbicide application.

bExpected values for control with herbicide combinations based on Colby’s equation (Eq. 1) are shown in parentheses following observed values.

cMeans were separated according to the Tukey-Kramer multiple range test at α = 0.05.

dAn asterisk (*) denotes a significant difference of P<0.05 between observed and expected values based on a two sided t-test.

Results from the current study are consistent with those reported by Smith (Reference Smith2019), that preemergence applications of isoxaflutole at 52.5, 79, and 105 g ai ha−1 provided 37% to 53%, 71% to 81%, and 87% to 89% control of barnyardgrass, respectively. In contrast, Bhowmik et al. (Reference Bhowmik, Kushwaha and Mitra1999) reported 99% barnyardgrass control with isoxaflutole at 72 g ai ha−1, exceeding the levels observed in the current study. Similarly, Meyer et al. (Reference Meyer, Norsworthy, Young, Steckel, Bradley, Johnson, Loux, Davis, Kruger and Bararpour2017) reported 99% control at 4 wk after application (WAA) of 100 g ai ha−1 isoxaflutole applied preemergence; however, control declined to 75% by 7 WAA. The same study found that combining isoxaflutole with metribuzin (100 + 414 g ai ha−1) resulted in a 9% decrease in weed control over time. In contrast, Smith (Reference Smith2019) observed both additive and synergistic effects when the two herbicides were applied preemergence.

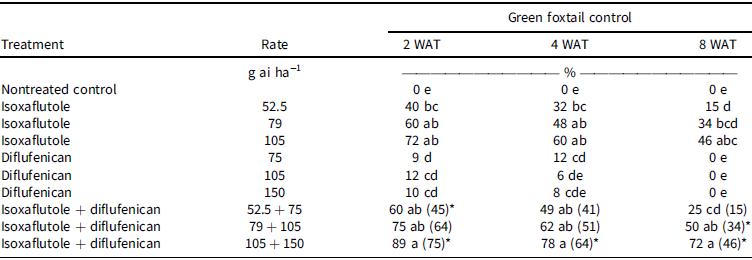

Green Foxtail Control

Isoxaflutole applied preemergence at 52.5, 79, and 105 g ai ha−1 provided 40%, 60%, and 72% control of green foxtail at 2 WAT, respectively. When assessed at 8 WAT, control levels fell to 15%, 34%, and 46%, respectively, at those rates (Table 6). Diflufenican applied preemergence at 75, 105, and 150 g ai ha−1 provided ≤12% control. Applications of isoxaflutole + diflufenican provided somewhat better control of green foxtail than diflufenican alone, but the percentages were similar to those when isoxaflutole was applied alone (Table 6). Significant increases in observed control over expected values were detected for the isoxaflutole + diflufenican mixture at 52.5 + 75 g ai ha−1 at 2 WAT; 79 + 105 g ai ha−1 at 8 WAT; and 105 + 150 g ai ha−1 at 2, 4, and 8 WAT, indicating synergistic interactions between isoxaflutole and diflufenican for the control of green foxtail while all other herbicide interactions exhibited additive interactions (Table 6).

Table 6. Green foxtail control with isoxaflutole and diflufenican alone or in combination, applied preemergence to corn at Ridgetown in 2018 and 2019, and Exeter in 2018.a–d

aAbbreviation: WAT, weeks after herbicide application.

bExpected values for control with herbicide combinations based on Colby’s equation (Eq. 1) are shown in parentheses following observed values.

cMeans were separated according to the Tukey-Kramer multiple range test at α = 0.05.

dAn asterisk (*) denotes a significant difference of P<0.05 between observed and expected values based on a two sided t-test.

In other studies, Effertz (Reference Effertz2021) reported that preemergence applications of diflufenican at rates of 18.75, 37.5, and 75 g ai ha−1 provided, respectively, 48% to 96%, 88% to 99%, and 96% to 99% control of giant foxtail. Preemergence applications of isoxaflutole at 13.13, 26.25, and 52.5 g ai ha−1 controlled giant foxtail by 7% to 79%, 28% to 76%, and 94% to 99%, respectively (Effertz Reference Effertz2021). When applied in combination, diflufenican + isoxaflutole applied at rates of 18.75 + 13.13, 37.5 + 26.25, and 75 + 52.5 g ai ha−1 provided 65% to 99% control of giant foxtail (Effertz Reference Effertz2021). Smith (Reference Smith2019) reported that preemergence applications of isoxaflutole at 52.5, 79, and 105 g ai ha−1 provided 24% to 28%, 41% to 76%, and 52% to 83% control of foxtail species, respectively. In addition, Sprague et al. (Reference Sprague, Kells and Penner1999) noted that in trials with corn, preemergence applications of isoxaflutole at 79 and 105 g ai ha−1 resulted in highly variable giant foxtail control, with effectiveness ranging from 23% to 89%.

Corn Injury and Yield

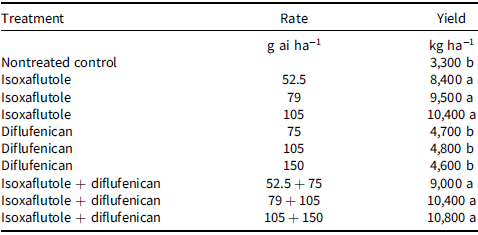

Minimal visible corn injury was observed at 1, 2, 4, and 8 WAE; therefore, the data were not analyzed (data not shown). These findings align with reports from previous research showing that preemergence applications of diflufenican and isoxaflutole, whether applied individually or together at different rates, caused little to no injury to corn (Effertz Reference Effertz2021; Grichar et al. Reference Grichar, Besler and Palrang2005; Janak and Grichar Reference Janak and Grichar2016; Soltani et al. Reference Soltani, Willemse and Sikkema2024a, Reference Soltani, Willemse and Sikkema2024b; Sprague Reference Sprague1999). In contrast, other studies have shown slight to moderate phytotoxicity in corn when high rates of isoxaflutole were applied alone or in combination with other herbicides (Benoit et al. Reference Benoit, Soltani, Hooker, Robinson and Sikkema2019; Bhowmik et al. Reference Bhowmik, Kushwaha and Mitra1999; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Shropshire and Sikkema2016; Geier and Stahlman Reference Geier and Stahlman1997; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Chahal and Regehr2012; Taylor-Lovell and Wax Reference Taylor-Lovell and Wax2001; Willemse et al. Reference Willemse, Soltani, Benoit, Hooker, Jhala, Robinson and Sikkema2021). Preemergence applications of diflufenican at rates ranging from 60 to 210 g ai ha−1 also resulted in no observable corn injury (Soltani et al. Reference Soltani, Willemse and Sikkema2024a)

Weed interference reduced corn yield by up to 69% in this study (Table 7). Diflufenican applied alone at 75, 105, and 150 g ai ha−1 resulted in corn yields of 4600 to 4800 kg ha−1, which is similar to the weedy control. In contrast, isoxaflutole applied alone at 52.5, 79, and 105 g ai ha−1 minimized weed interference and significantly increased corn yields to 8400, 9500, and 10400 kg ha−1, respectively (Table 7). Reduced weed interference with the preemergence co-application of isoxaflutole + diflufenican significantly improved yields compared to the nontreated control or diflufenican, with isoxaflutole + diflufenican mixtures applied preemergence at 52.5 + 75, 79 + 105, and 105 + 150 g ai ha−1, producing corn grain yields of 9000, 10400, and 10800 kg ha−1, respectively. Yields from all isoxaflutole-alone and herbicide mixture treatments were statistically similar and significantly higher than both the weedy control and diflufenican-alone treatments (Table 7). These results are similar to a number of studies that have shown no or minimal corn injury or yield reduction with diflufenican or isoxaflutole (Benoit et al. Reference Benoit, Soltani, Hooker, Robinson and Sikkema2019; Bhowmik et al. Reference Bhowmik, Kushwaha and Mitra1999; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Shropshire and Sikkema2016; Effertz Reference Effertz2021; Geier and Stahlman Reference Geier and Stahlman1997; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Chahal and Regehr2012; Soltani et al. Reference Soltani, Willemse and Sikkema2024a; Taylor-Lovell and Wax Reference Taylor-Lovell and Wax2001; Willemse et al. Reference Willemse, Soltani, Benoit, Hooker, Jhala, Robinson and Sikkema2021).

Table 7. Corn yield from treatments with isoxaflutole and diflufenican alone or in combination, applied preemergence at Ridgetown in 2018 and 2019, and Exeter in 2018. a

a Means were separated according to the Tukey-Kramer multiple range test at α = 0.05.

In conclusion, isoxaflutole provided acceptable control of velvetleaf, common ragweed, and common lambsquarters; and partial control of green pigweed, barnyardgrass, and green foxtail. Diflufenican alone was largely ineffective but showed utility when it was co-applied with isoxaflutole to control green pigweed, barnyardgrass, and green foxtail. The isoxaflutole + diflufenican combination is a viable preemergence weed control option for broad-spectrum weed control with minimal corn injury. These findings suggest that diflufenican, with its distinct mode of action, could be a component of an integrated weed management approach for managing certain weed species that grow among corn crops. Further research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of preemergence applications of diflufenican at various rates, in combination with other effective herbicides, as part of an integrated weed management strategy for controlling troublesome weeds in corn production.

Practical Implications

This study demonstrates that isoxaflutole, applied preemergence, is an effective herbicide for managing key broadleaf weeds such as velvetleaf, green pigweed, common ragweed, and common lambsquarters in corn production. Control levels of these species consistently exceeded 85% at application rates of 79 to 105 g ai ha−1. In contrast, diflufenican applied alone, even at rates of up to 150 g ai ha−1, was largely ineffective against all broadleaf species, offering ≤38% control.

Isoxaflutole applied alone provided moderate suppression of barnyardgrass (16% to 75%) and green foxtail (15% to 72%), while diflufenican alone was ineffective (≤12% control). However, the isoxaflutole + diflufenican combination provided a significant improvement in grass weed control. The highest mixture rate (105 + 150 g ai ha−1) provided 71% to 86% control of barnyardgrass and 72% to 89% control of green foxtail. Synergistic interactions were identified at multiple rate combinations and evaluation timings, particularly for grass species, highlighting the benefit of the co-application of both herbicides.

Corn showed no signs of injury from any of the herbicide treatments evaluated in this study. However, weed interference led to yield losses of up to 69%. Corn yields were significantly improved ranging from 8.4 to 10.8 T ha−1 when isoxaflutole was applied, whether alone or in combination with diflufenican. In contrast, when diflufenican was applied alone, weed suppression was insufficient, and corn yields remained comparable to those of the nontreated control.

These findings show that diflufenican, due to its distinct mode of action, may be effective in controlling specific weed biotypes in corn when used in combination with isoxaflutole, highlighting the importance of integrating herbicide modes of action with cultural and mechanical strategies for consistent control of problematic weeds.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Lynette Brown for her valuable technical assistance.

Funding

This study was partially supported by the Grain Farmers of Ontario, the Ontario Agri-Food Innovation Alliance Funding Program, and Bayer Crop Science Inc.

Competing Interests

The authors report they have no conflicts of interest related to this study.