Introduction

Multimorbidity, the coexistence of multiple health conditions, is associated with polypharmacy, greater frequency and complexity of health service utilisation, suboptimal care outcomes, and premature mortality (Skou et al. Reference Skou, Mair, Fortin, Guthrie, Nunes, Miranda, Boyd, Pati, Mtenga and Smith2022; World Health Organization, 2016). It complicates clinical care as treatment guidelines are often informed by clinical trials that typically exclude participants with multiple conditions (Hidalgo et al. Reference Hidalgo, Blumm, Barabási and Christakis2009; Kuan et al. Reference Kuan, Denaxas, Patalay, Nitsch, Mathur, Gonzalez-Izquierdo, Sofat, Partridge, Roberts, Wong, Hingorani, Chaturvedi, Hemingway and Hingorani2023). Multimorbidity can include physical and mental health conditions. It also increases the risk of chronic mental health disorders (Ronaldson et al. Reference Ronaldson, Arias de la Torre, Prina, Armstrong, Das-Munshi, Hatch, Stewart, Hotopf and Dregan2021).

The global prevalence of multimorbidity is increasing, partly driven by the accumulation of conditions among older people in the context of increasing life expectancy (Álvarez-Gálvez et al. Reference Álvarez-Gálvez, Carretero-Bravo, Suárez-Lledó, Ortega-Martín, Ramos-Fiol, Lagares-Franco, OFerrall-González, Almenara-Barrios and González-Caballero2022; Chowdhury et al. Reference Chowdhury, Das, Sunna, Beyene and Hossain2023). Individuals facing socioeconomic deprivation are at greater risk and tend to develop multiple conditions up to a decade earlier than those in more affluent groups (Skou et al. Reference Skou, Mair, Fortin, Guthrie, Nunes, Miranda, Boyd, Pati, Mtenga and Smith2022).

Definitions and measures of multimorbidity vary significantly across health research. As a minimum, the state has been defined as the presence of two or more diseases (Johnston et al. Reference Johnston, Crilly, Black, Prescott and Mercer2019; Sharma et al. Reference Sharma, Schwendimann, Endrich, Ausserhofer and Simon2021). More sophisticated approaches are based on the co-existence of specific conditions predictive of harm, including the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, which includes 30 medical, psychiatric, and behavioural conditions most strongly associated with adverse health outcomes (Elixhauser et al. Reference Elixhauser, Steiner, Harris and Coffey1998; Sharma et al. Reference Sharma, Schwendimann, Endrich, Ausserhofer and Simon2021).

The association between substance use and chronic disease is positive and bidirectional. People who use drugs (PWUD), especially those with substance use disorders (SUD), are more likely to have multiple health conditions including physical (notably chronic pain, cancer, and cardiovascular disease) and mental health problems (including anxiety and/or depressive disorders, psychotic illness) (Lewer et al. Reference Lewer, Tweed, Aldridge and Morley2019), European Union Drugs Agency 2023). Those with chronic health conditions are also at increased risk of developing SUD (Lewer et al. Reference Lewer, Freer, King, Larney, Degenhardt, Tweed, Hope, Harris, Millar, Hayward, Ciccarone and Morley2020; Schulte & Hser 2014; Torrens et al. Reference Torrens, Mestre-Pintó and Domingo-Salvany2015).

PWUD are more than three times as likely to be hospitalised compared to the general population (Lewer et al. Reference Lewer, Tweed, Aldridge and Morley2019). Around 21% of excess admissions were drug-related, and the remainder were predominantly due to mental and behavioural disorders, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), digestive diseases and external causes (e.g. head injuries). PWUD were over six times more likely to die. Around half of excess mortality was due to drug-related causes, with substantial contributions from digestive (primarily liver), respiratory diseases (mainly COPD), and external causes (primarily accidents). The most common recorded medical conditions among people having a drug-related death (DRD) in Scotland include physical (respiratory and cardiovascular disease, blood borne viruses, epilepsy) and psychiatric conditions (depression, anxiety, personality disorders, schizophrenia), with evidence of increasing multimorbidity over time (Public Health Scotland, 2022).

Routinely collected health data now play a central role in multimorbidity research. These data allow researchers to move beyond simple disease counts and better understand how chronic conditions cluster among people. Methods such as correlation, network modelling, and cluster analysis have been used to uncover co-occurrence patterns (Cicek et al. Reference Cicek, Buckley, Pearson-Stuttard and Gregg2021; Fabbri et al. Reference Fabbri, Celli, Agustí, Criner, Dransfield, Divo, Krishnan, Lahousse, Montes de Oca, Salvi, Stolz, Vanfleteren and Vogelmeier2023; Hidalgo et al. Reference Hidalgo, Blumm, Barabási and Christakis2009). For example, correlations have been employed to identify co-occurring diseases and prescription burden (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Wang, Zhu, Zhang, Zhang, Zhang and Dong2023). Network-based methods model diseases as interconnected nodes, revealing central conditions and communities of co-occurring diseases (Hidalgo et al. Reference Hidalgo, Blumm, Barabási and Christakis2009). Clustering techniques have also been used to identify latent clusters of co-occurring conditions, or clusters of patients with distinct multimorbidity profiles (Poblador-Plou et al. Reference Poblador-Plou, van den Akker, Vos, Calderón-Larrañaga, Metsemakers and Prados-Torres2014; Uszko-Lencer et al. Reference Uszko-Lencer, Janssen, Gaffron, Vanfleteren, Janssen, Werter, Franssen, Wouters, Rechberger, Brunner La Rocca and Spruit2022). These data-driven approaches provide insights into the structure and complexity of multimorbidity in real-world populations with potential to inform the design and provision of prevention and treatment services in line with patient needs.

This study examined hospital admission data on DRD decedents in Scotland to explore the contribution different statistical methods can make to our understanding of multimorbidity among this group.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a register-based cohort study to explore patterns of multimorbidity among PWUD. We quantified ICD-coded admissions and used correlation, network analysis, and Bayesian clustering as part of the broader Bayesian profile regression framework (Molitor et al. Reference Molitor, Papathomas, Jerrett and Richardson2010), to examine co-occurrence of conditions defined by the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. In contrast to more standard clustering approaches such as K-means, Bayesian clustering allows us to evaluate the uncertainty that is associated with the number of clusters and the profile of the subjects within each cluster. Reporting followed the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology) guidelines (von Elm et al. Reference von Elm, Altman, Egger, Pocock, Gøtzsche and Vandenbroucke2008).

Data source and population

Anonymised data on people who had a recorded drug-related death in Scotland between calendar years 2008–2019 were extracted from the National Drug-Related Death Database and linked to data on general acute and psychiatric hospital admissions occurring since 1996 among this group.

Study variables

For each admission, we recorded the date and ICD-10 code for the primary condition. Decedent characteristics included sex, year of death, and age at death. Admissions matching Elixhauser comorbidities were identified using the R comorbidity library v1.1.0 (Gasparini, Reference Gasparini2025). Binary indicators were created to indicate whether each decedent had any recorded admissions for these conditions.

Statistical analysis

We used summary statistics and histograms to describe participant characteristics, and frequency tables to report admissions by ICD chapter and by Elixhauser comorbidities. When reporting decedent numbers, values <10 are suppressed throughout to avoid disclosure. Due to the low numbers of admissions for some conditions, the Fisher’s exact test was used to assess correlations between comorbidities (Neuhäuser & Ruxton, Reference Neuhäuser and Ruxton2025). Associations were quantified as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals, calculated from 2 x 2 tables for each condition pair. Associated p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg method (Benjamini & Hochberg, Reference Benjamini and Hochberg1995). Results were displayed in a correlation matrix and statistically significant relationships as a correlogram.

We included condition pairs with statistically significant associations in a network analysis, modelling each condition as a node and each association as an edge. We calculated network metrics (degree, betweenness, eigenvector) to identify conditions with important or structural roles. A network diagram was generated to visualise the direction and strength of associations (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Ma and McNally2021). Four community detection algorithms (Louvain, Leiden, Infomap, Walktrap) were compared using modularity measures to investigate whether conditions formed densely connected groups (Permana & Yaputra, Reference Permana and Yaputra2024).

We used flexible Bayesian clustering to perform unsupervised clustering of individuals based on hospital admissions. This data-driven method determined the optimal number of clusters from the data. Clusters represent subgroups with similar comorbidity profiles, and we identified the optimal clustering structure through post-processing the rich Markov chain Monte Carlo output from the adopted inferential procedure (Molitor et al. Reference Molitor, Papathomas, Jerrett and Richardson2010). We then characterised each subgroup by the prevalence of key conditions. Variable selection was implemented to highlight the conditions that drive the clustering (Papthomas et al. Reference Papathomas, Molitor, Hoggart, Hastie and Richardson2012). Model diagnostics and sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess stability and robustness to initial conditions.

Analyses and figure generation were performed using R v4.3 (R Core Team, 2024) with a significance level of 0.05. Fisher’s exact test and associated OR were calculated using the stats library in base R (R Core Team, 2024), networks were analysed and visualised using the igraph and ggraph libraries (Csárdi et al. Reference Csárdi, Nepusz, Traag, Horvát, Zanini, Noom, Müller, Schoch and Salmon2025; Pendersen, Reference Pedersen2025), and Bayesian clustering within the broader Profile Regression framework was conducted using the PReMiuM package (Liverani et al. Reference Liverani, Hastie, Azizi, Papathomas and Richardson2015).

Results

Data were obtained on 53,651 hospital admissions from 5,749 DRD decedents. Seventy percent were male and the median age at death was 40 years (IQR 33–47) (Figure S1), around 41 years earlier than the general population in Scotland in 2008–19 (National Records of Scotland, 2024). The median number of admissions per decedent was six (IQR 3–12) (Figure S2).

Causes of hospital admission: overall and elixhauser comorbidities

When categorised by ICD 10 chapter, the most common reasons for admission were Injury, Poisoning and other external causes (n = 12,772, 23.8% of all admissions), predominantly drug-related poisonings and head injuries; Mental and behavioural disorders (8,134, 15.2%), due to substance use and schizophrenia; Symptoms, signs and abnormal findings not elsewhere classified (6.132, 11.4%), mainly pain-related; inflammatory or functional; diverse Diseases of the digestive system (4,557, 8.5%) ; Diseases of the respiratory system (4,004, 7.5%), including worsening of chronic conditions and lower respiratory tract infections; a range of maternal and obstetric complications from Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium (3,917, 7.3%); and several Diseases of the circulatory system (2,380, 4.4%), including cardiovascular pathology, cerebrovascular and thromboembolic diseases (Table S1, Table S2).

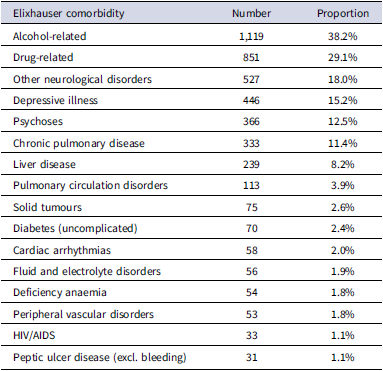

2,928 (50.9%) of people had one or more admissions for Elixhauser comorbidities (Table S3). These were mostly related to alcohol (1,119, 38.2%) or drug use (851, 29.1%), plus several neurological / mental health conditions, including other neurological disorders (mostly epilepsy, other seizures, and anoxic brain damage: 527; 18.0%); depression (446, 15.2%); psychoses (366, 12.5%), cardiovascular diseases (chronic pulmonary disease: 333, 11.4%; pulmonary circulation disorders: 113, 3.9%) and liver disease (239, 8.2%).

After removing comorbidities which each accounted for less than 1% of admissions, data on 16 conditions causing admission among 2,928 decedents remained (Table 1).

Table 1. Number and proportion of decedents with one or more admissions for Elixhauser comorbidities (N = 2,928 decedents ever admitted for an Elixhauser comorbidity)

These results quantify a substantial disease burden among this group of PWUD, including physical and psychological morbidity. Further analyses explored associations between Elixhauser comorbidities among decedents.

Correlation analysis

Figure 1 and Table S4 show statistically significant associations between pairs of Elixhauser conditions causing hospital admission among decedents. The OR and corresponding p-values from Fisher’s exact tests highlight specific patterns of co-occurring comorbidities.

Figure 1. Correlogram showing statistically significant pairs of Elixhauser comorbidities causing admission. Notes: Yellow shading indicates negative associations (OR < 1), green to purple shading indicates increasingly positive associations (OR > 1). aids = HIV/AIDS; alcohol = Alcohol use; cpd = Chronic pulmonary disease; dane = Deficiency anaemia; depre = Depression; diabunc = Diabetes (uncomplicated); drug = Drug use; fed = Fluid and electrolyte disorders; ld = Liver disease; ond = Other neurological disorders; pcd = Pulmonary circulation disorders; psycho = Psychoses; pud = Peptic ulcer disease (excl. bleeding); pvd=Peripheral vascular disorders; solidtum = Solid tumours there were no statistically significant associations involving cardiac arrhythmias (carit).

Admissions for alcohol use demonstrated significant negative associations with several conditions, including chronic pulmonary disease (OR = 0.45, p < 0.001), deficiency anaemia (0.41, p = 0.029), depression (0.59, p < 0.001), drug use (0.43, p < 0.001), pulmonary circulation disorders (0.57, p = 0.039), psychoses (0.38, p < 0.001), and peripheral vascular disorders (0.28, p = 0.002). However, admissions for alcohol-related conditions showed a significant positive association with liver disease (2.00, p < 0.001).

Drug use-related admissions were significantly negatively associated with fluid and electrolyte disorders (0.04, p < 0.001), liver disease (0.51, p < 0.001), neurological disorders (0.53, p < 0.001), pulmonary circulation disorders (0.54, p = 0.042), peptic ulcer disease (0.17, p = 0.021), peripheral vascular disorders (0.14, p < 0.001), and solid tumours (0.21, p < 0.001). Conversely, admissions for the consequences of drug use were positively associated with those for psychoses (1.81, p < 0.001).

Psychoses demonstrated mixed associations, showing positive co-occurrence with depression (1.58, p = 0.01) and drug use (1.81, p < 0.001), but negative associations with fluid and electrolyte disorders (0.12, p = 0.031), liver disease (0.29, p < 0.001), and other neurological disorders (0.46, p < 0.001).

Notably, uncomplicated diabetes admissions were strongly correlated with fluid and electrolyte disorders (4.21, p = 0.039) but negatively correlated with depression (0.24, p = 0.029) and other neurological disorders (0.27, p = 0.021). HIV/AIDS showed a strong positive association with liver disease (3.67, p = 0.021) but was negatively associated with admissions for the consequences of alcohol use (0.28, p = 0.028). There were no significant associations involving cardiac arrhythmias.

These findings indicate substantial physical and psychiatric comorbidity and clear patterns of co-occurrence resulting from undiagnosed or poorly managed chronic conditions among this group.

Network analysis

Network analysis (Figure 2) provided further detail on relationships between conditions, shifting from focusing on comorbidity dyads to explore broader patterns among conditions that cluster together systematically. Key reasons for admission – including alcohol use, drug use, psychoses, and other neurological disorders – appear as larger nodes within the network, reflecting both their contribution to the burden of admissions and centrality in the comorbidity structure. Strongly weighted associations are shown as wider lines with stronger shading. Line colour indicated direction of association, with negative relationships shown in blue, and positive associations in red. The most notable positive associations included admissions for fluid and electrolyte disorders and uncontrolled diabetes, and those for HIV/AIDS and liver disease.

Figure 2. Network diagram. Notes: aids = HIV/AIDS; alcohol = Alcohol use; cpd = Chronic pulmonary disease; dane = Deficiency anaemia; depre = Depression; diabunc = Diabetes (uncomplicated); drug = Drug use; fed = Fluid and electrolyte disorders; ld = Liver disease; ond = Other neurological disorders; pcd = Pulmonary circulation disorders; psycho = Psychoses; pud = Peptic ulcer disease (excl. bleeding); pvd = Peripheral vascular disorders; solidtum = Solid tumours.

The network consisted of 15 health conditions (nodes) connected by 64 links (edges), with a density of 0.61, indicating that many conditions were closely linked. The average path length was 1.83, suggesting efficient connections between conditions, while the global clustering coefficient of 0.43 showed a moderate tendency for related conditions to cluster together.

Additional metrics provide insights into the structural relationships between different comorbidities among decedents (Table S5). Conditions with relatively high degree centrality are connected to more conditions, suggesting their broader involvement in comorbidities severe enough to cause hospital admission. Several conditions – including those related to drug and alcohol use, psychoses, depression, other neurological disorders, chronic pulmonary disease, and liver disease – demonstrated high degree centrality (≥10), indicating their extensive co-occurrence with other conditions. Drug use had the highest degree (20), followed by alcohol use (18), psychoses (14), depression and other neurological disorders (12 each), and chronic pulmonary disease and liver disease (10 each).

Betweenness centrality reflects how often a condition acts as a bridge or intermediary connecting other nodes. Alcohol use, drug use, depression, psychoses, other neurological disorders, and liver disease each had relatively high betweenness scores (≥4.0), highlighting their pivotal role in mediating or connecting different areas of the comorbidity network. Drug use (34.04) and alcohol use (26.89) had particularly high betweenness, reflecting their wide involvement as causes for admission among the cohort.

Measures of eigenvector centrality further emphasise the influential role of these key conditions. This metric quantifies a condition’s importance based on its connections to other highly connected conditions; the high eigenvector centrality for drug use (1.00), alcohol use and psychoses (0.94 each), chronic pulmonary disease and depression (0.78 each), and other neurological disorders (0.73) suggests they are key drivers of multimorbidity admissions.

In contrast, conditions such as uncomplicated diabetes, fluid and electrolyte disorders, pulmonary circulation disorders, peripheral vascular disorders, deficiency anaemia, peptic ulcer disease, HIV/AIDS, and solid tumours had lower degree (≤6.00), betweenness (≤2.00), closeness (≤0.52), and eigenvector centrality scores (≤0.40), suggesting they have more peripheral roles in this network. While these conditions remain clinically significant, they exert relatively less influence or interconnection in the comorbidity landscape among this group of PWUD.

Cluster analysis

This approach aimed to identify clusters of people with similar multimorbidity patterns through analysis of admissions for all Elixhauser comorbidities. Detailed Bayesian clustering results are provided in Supplementary Figures S3 and S4 and summarised in Figure 3. Seven clusters were identified, with a mean size of 418.3 decedents (range 191–1048).

Figure 3. Profile of the different clusters in terms of posterior probabilities of Elixhauser comorbidities causing admissions among decedents. Notes: “L” = lower than average probability, “–” = average probability, “H” = higher than average probability. aids=HIV/AIDS; alcohol = Alcohol use-related; carit = Cardiac arrhythmias; cpd = Chronic pulmonary disease; dane = Deficiency anaemia; depre = Depression; diabunc = Diabetes (uncomplicated); drug = Drug use-related; fed = Fluid and electrolyte disorders; ld = Liver disease; ond = Other neurological disorders; pcd = Pulmonary circulation disorders; psycho = Psychoses; pud = Peptic ulcer disease (excl. bleeding); pvd = Peripheral vascular disorders; solidtum = Solid tumours.

Considering average probabilities within the entire sample, Cluster 1 was characterised by decedents with higher-than-average probabilities of admissions for psychiatric conditions (notably depression and psychosis) and those resulting from drug use, alongside lower-than-average probabilities of admissions for most physical health conditions.

Cluster 2 includes decedents with higher-than-average probabilities of admission for a broad range of physical comorbidities, including all cardiovascular and gastrointestinal conditions, as well as deficiency anaemia, HIV/AIDS, diabetes, fluid and electrolyte disorders, and solid tumours. In contrast, this group had lower-than-average probabilities of admissions for psychiatric, neurological, respiratory, and substance use-related conditions.

Cluster 3 was the largest, comprising 35.8% of the sample. It was defined by elevated probabilities of admissions for liver disease and alcohol-related conditions, and reduced probabilities for most other comorbidities.

Cluster 4 was characterised by higher-than-average probabilities for admissions for other neurological disorders (primarily epilepsy, other convulsions, anoxic brain damage), with average or below average probabilities across the remaining conditions.

Cluster 5 included subjects with increased probabilities of drug-related admissions but notably lower probabilities for alcohol-related, psychiatric, and other physical health conditions, except for average levels of admissions for uncontrolled diabetes.

Cluster 6, the smallest cluster (6.5% of decedents), was defined by a higher probability of admissions for depressive illness, with otherwise low or average levels of comorbidity.

Cluster 7 was moderately sized (7.6% of decedents) and included those who only had a higher probability of admission for chronic pulmonary disease.

The results of variable selection indicated that substance use (drugs, alcohol) and depression were the most strongly informative conditions driving the clustering results observed. Liver disease, other neurological conditions, chronic pulmonary disease, and psychotic illness also contributed meaningfully to the observed results (Table S9).

Diagnostic checks indicated that the model ran smoothly and reached stable results. Sensitivity analyses suggested that the number and size of clusters were robust to changes in starting conditions, increasing confidence in the stability and reliability of the results reported.

These findings illustrate how Bayesian clustering can uncover distinct patterns of comorbidity among PWUD, highlighting complex multimorbidity and clusters of people defined by dominant conditions. Several groups were characterised by combinations of admissions for mental illness and substance use, while others were defined primarily by combinations of physical health problems with minimal psychiatric comorbidity. This underscores the heterogeneity within this population and reveals important patterns in the interplay between physical and mental health. These insights may inform more integrated models of care that address both domains simultaneously, and support more nuanced approaches to risk assessment, treatment planning, and policy development.

Discussion

This study examined patterns of hospital-treated comorbidity among individuals who had a DRD in Scotland over an 11-year period. These findings offer novel insights into the complex and heterogeneous health profiles within this vulnerable population. The application of complementary statistical methods enabled a comprehensive exploration of multimorbidity.

Correlation and network analysis identified patterns in co-occurring conditions causing admission. The strongest correlation was observed between uncontrolled diabetes and fluid and electrolyte disorders. Poorly controlled diabetes can cause metabolic disturbances such as dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, and diabetic ketoacidosis, which often require hospitalisation. Admissions for depression and drug use-related conditions were positively associated with those for psychosis, while psychosis was negatively associated with alcohol-related admissions. Admissions for alcohol use were negatively correlated with those for several conditions including chronic pulmonary disease, depression, and psychosis. These should not be interpreted as protective effects of alcohol. A more likely explanation is collider bias, which arises when analyses are restricted to a group with a shared outcome, in this case drug-related death. Within this cohort, alcohol-related and non-alcohol-related conditions may represent distinct and competing pathways to death, giving rise to apparent inverse associations.

Network analysis also highlighted conditions as being highly interconnected. However, this did not identify strong positive connections, besides the key comorbidity dyads (fluid and electrolyte disorders with uncontrolled diabetes, and liver disease with HIV/AIDS) identified in the correlation analysis. Several conditions had high eigenvector values (drug use, alcohol use, psychoses, depression, chronic pulmonary disease, and other neurological disorders) and occupied central positions in the comorbidity network. Their eigenvector centrality indicates that these conditions were not only connected to many others but are also closely linked to other well-connected nodes, suggesting they could form part of the core structure of multimorbidity in this cohort. In practical terms, this means that alcohol and drug use disorders, together with major mental health conditions and chronic diseases such as pulmonary disease, could represent influential hubs that shape the overall pattern of admissions. Their prominence reflects both the clustering of substance use with mental and physical health conditions and the role of these disorders as key pathways through which multiple comorbidities interconnect.

We then explored the clustering of individuals based on their multimorbidity profiles. Bayesian clustering identified seven groups of decedents, each characterised by shared patterns of hospital admissions. These included a large group with alcohol-related and liver disease admissions, and a cluster with broad physical multimorbidity but low psychiatric and substance use admissions. Other clusters were primarily defined by specific psychiatric or physical health admissions.

These findings describe complex and heterogeneous health profiles of people who die drug-related deaths, revealing overlapping physical and mental health burdens with shared causes and pathways.

Correlated admission patterns may reflect undiagnosed or sub-optimally managed conditions and/or accelerated disease progression linked to substance use. For example, the observed link between uncontrolled diabetes and fluid/electrolyte disorders aligns with evidence of earlier onset and poorer diabetes outcomes in PWUD compared with the general population (Alhassan et al. Reference Alhassan, Elrashid, Alshehhi, Al Mamari, Abu Raddaha, Assaf and Elliot2023; Forthal et al. Reference Forthal, Choi, Yerneni, Zhang, Siscovick, Egorova, Mijanovich, Mayer and Neighbors2021; Warner et al., Reference Warner, Greene, Buchsbaum, Cooper and Robinson1998). Although the number of admissions for HIV/AIDS was small, these were strongly associated with those for liver disease. This could reflect hepatitis C and/or alcohol-related disease among those affected by the outbreak of HIV among PWUD in Glasgow detected in 2015 (McAuley et al. Reference McAuley, Palmateer, Goldberg, Trayner, Shepherd, Gunson, Metcalfe, Milosevic, Taylor, Munro and Hutchinson2019).

Psychiatric comorbidity was prominent and complex. Positive associations between depression, drug use, and psychosis align with established links between substance use disorders and mental illness (Lewer et al. Reference Lewer, Freer, King, Larney, Degenhardt, Tweed, Hope, Harris, Millar, Hayward, Ciccarone and Morley2020). However, the negative association between psychosis and alcohol-related admissions diverges from existing literature linking alcohol use disorder with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (Archibald et al. Reference Archibald, Brunette, Wallin and Green2019; Grunze et al. Reference Grunze, Schaefer, Scherk, Born and Preuss2021), suggesting factors associated with this cohort or locale that warrant further investigation.

These findings have several clinical implications. The identification of subgroups with differing health burdens suggests that a one-size-fits-all model of care may be insufficient for PWUD. In particular, some clusters were defined by high levels of mental illness and substance-related hospital admissions, while others exhibited extensive physical comorbidity with little evidence of psychiatric admissions. Psychiatric comorbidities complicate substance use disorder treatment, are associated with suboptimal outcomes, and increase the risk of attrition (Krawczyk et al. Reference Krawczyk, Feder, Saloner, Crum, Kealhofer and Mojtabai2017). Many symptoms associated with psychiatric disorders may also result from substance use or withdrawal, complicating the differentiation between primary psychiatric conditions and substance-related presentations. Substance use and withdrawal can also mask underlying psychiatric conditions, delaying accurate diagnosis and treatment (Bahji, Reference Bahji2024; Davis et al. Reference Davis, McMaster, Christie, Yang, Kruk and Fisher2023).

Physical comorbidities pose similar challenges to the care of PWUD. Managing multiple health conditions can involve polypharmacy, increasing the risk of drug-drug interactions with prescribed and non-prescription drug use. Whilst addiction treatment services often address mental health needs, other specialties addressing key physical health comorbidities (e.g. endocrinology, hepatology, cardiology) may have less experience of working with people with substance use disorders. Ongoing substance use may be perceived by clinicians as a barrier to delivering standard medical care. Patient information resources and appointment systems may be less appropriate for people who experience challenges with literacy, memory, or self-management.

Tailoring care to these distinct profiles may improve outcomes, particularly where comorbidity contributes to poor engagement or treatment adherence. From a psychiatric perspective, the prominence of psychotic disorders and depression in multiple clusters reinforces the need for integrated mental health and addiction services, especially in hospital settings where such admissions may represent critical intervention opportunities. The central positioning of certain conditions within the network, especially psychoses, liver disease, and other neurological disorder, suggests they may serve as markers of wider health system contact or clinical complexity. Presentations for these conditions could offer opportunities for proactive intervention, coordinated care planning, and risk reduction, particularly in individuals with histories of repeated admissions, especially for escalating disease severity. Proactive intervention could reduce the personal and social costs of undiagnosed and sub-optimally managed multimorbidity and avoid preventable mortality including DRD.

This study has several strengths, including the use of routinely collected, linked national datasets and the application of advanced methods capable of capturing the multifaceted nature of multimorbidity. Whilst previous work has explored relationships between co-occurring conditions among people with substance use disorders (Charron et al. Reference Charron, Yu, Lundahl, Silipigni, Okifuji, Gordon, Baylis, White, Carlston, Abdullah, Haaland, Krans, Smid and Cochran2023; Flórez et al. Reference Flórez, López-Durán, Triñanes, Osorio, Fraga, Fernández, Becoña and Arrojo2015; López-Toro et al. Reference López-Toro, Wolf, González, van den Brink, Schellekens and Vélez-Pastrana2022; Shmulewitz et al. Reference Shmulewitz, Levitin, Skvirsky, Vider, Eliashar, Mikulincer and Lev-Ran2024), this is the first study to examine drivers of hospital admission among people in the years preceding their drug-related death.

However, there are limitations. The analysis employed data on primary cause for hospital admission and therefore does not capture undiagnosed disease, secondary conditions, or problems managed entirely in primary care. The study is cross-sectional and cannot determine the temporal order of comorbidities or infer causality. The data are limited to those who subsequently had a DRD so our findings may not generalise to PWUD who do not have this outcome. The relationships we observe between conditions might look different, often more strongly negative, than those in the wider population. This is due to a known statistical issue called collider bias, which can occur when studies focus only on people who share a specific outcome like hospital admission or death (Bagley & Altman Reference Bagley and Altman2016).

Multimorbidity was coded using Elixhauser categories, which may not be sufficiently detailed for this population. For example, “other neurological conditions” includes hypoxic brain injury, which may result from non-fatal overdose in this group. Elixhauser conditions are predictive of the complexity of care, but do not capture all admissions that provide opportunities for intervention.

Future work should examine a broader range of conditions by incorporating diagnosis and prescribing data to capture those managed in community settings. Including individuals who use drugs but have not been hospitalised or experienced a drug-related death would enable comparisons of risk profiles. Further research should investigate how variations in sex, age, and substances used shape patterns of multimorbidity and clinical outcomes in this population. Longitudinal methods should be explored to identify and describe temporal sequences in the development of comorbidities and associated outcomes including hospitalisation and death.

These findings have implications for clinical practice, training, and policy. Patterns in the clustering of substance use with both psychiatric and physical health conditions indicates that addiction cannot be addressed in isolation from wider health needs. Dual diagnosis services are essential, but clinicians in these roles may also need additional skills to recognise and manage the broad range of physical comorbidities highlighted in this research. Similarly, the central role of alcohol and drug use in acute hospital admissions among this vulnerable group strengthens the case for liaison addiction psychiatry within general hospital settings, where specialist teams can support integrated care, reduce repeated admissions, and improve continuity between hospital and community services.

There are also important implications for workforce development. Training in addiction medicine should be a standard part of both undergraduate and postgraduate medical curricula, ensuring that all clinicians are prepared to recognise and respond to substance use and its comorbidities. Strengthening this training across the medical pathway would help embed addiction expertise more firmly within healthcare, supporting translation of research into practice and contributing to more effective policy development. Ultimately, equipping clinicians to manage substance use as a core component of multimorbidity is essential to improving outcomes for patients and the wider health system.

In summary, our findings highlight the diversity of health profiles among a vulnerable group of people who use drugs and identify distinct patterns of physical and mental illness in the context of substance use. Greater recognition of these distinct multimorbidity patterns may support more responsive, integrated models of care and inform service planning and risk stratification strategies in addiction and mental health services.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2025.10149.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of (1) the eDRIS Team at Public Health Scotland for their involvement in obtaining approvals, provisioning, and linking data and the use of the secure analytical platform within the National Safe Haven; (2) National Records of Scotland for data linkage; and (3) Scottish Exchange of Data (Scottish Government) for allowing us to access the data. MMcC, SL, KS and BMA were funded by the Relationships and Health programme in the MRC/CSO Social and Public health Sciences Unit, funded by the Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00022/3) and the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office (SPHSU18). JS is undertaking a PhD at, and funded by, the University of St Andrews.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: JS, AB. Data Curation: JS. Formal Analysis: JS. Funding Acquisition: KS, MM, AB, JS. Investigation: JS. Methodology: JS, AB, MP, CM. Project Administration: JS. Resources: JS. Software: JS. Supervision: AB, MP, CM. Validation: MP, CM. Visualisation: JS. Writing – Original Draft: JS. Writing – Review & Editing: JS, AB, MP, CM, MM, BMA, SL, KS, FK.

Financial support

Data acquisition was funded by a grant from the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government HIPS/19/32.

Competing interests

The authors confirm they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The study was approved by research ethics committees at the College of Medical, Veterinary & Life Sciences (University of Glasgow, ref: 20210201), the School of Medicine (University of St Andrews, ref: MD17993), and the Public Benefit and Privacy Panel for Health and Social Care (NHS Scotland, ref: 1920–0196).