Introduction

In the United States, political participation (including the right to participate) has been a cornerstone in the struggle for equality among racial minorities. Historically, black churches played an important role in this struggle, and church attendance among racial minorities has been linked empirically to higher political participation (Olsen Reference Olsen1970; Verba et al. Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; Calhoun‐Brown Reference Calhoun‐Brown1996; Jones‐Correa & Leal Reference Jones‐Correa and Leal2001). Increasingly, Europe's growing ethnic minorities' struggle for equality and representation mirrors the processes that have taken place in the United States. Yet, we know little about the role of religious involvement in mobilising political participation among European minorities. Footnote 18 This article seeks to address this question by investigating the impact of religious attendance on the political participation of ethnic minorities in a new context (Great Britain) and in new cases of non‐Christian religions such as Islam and Sikhism as well as Christianity (which has been the main focus of American research). On the theoretical side, we distinguish explicitly between mediating and moderating mechanisms and show the importance of the history of ethno‐religious struggles for understanding the role of religion.

Britain presents an especially interesting case for testing the effect of religious attendance on participation because of the contested role of religion in British politics. Whereas in the United States the political relevance of religion is well acknowledged and accepted, and in many European countries it is explicitly incorporated through policy (cf. Dutch pillarisation), in Britain religion is more marginalised in political life and explicit references to it from politicians are rare and controversial. The current Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government has more openly acknowledged the civic role of religion in its Big Society policy initiative (Kettell Reference Kettell2012) and Prime Minister David Cameron has made some specific remarks on the nature of Britain as a Christian country, but, as many opinion polls show, these references to religion remain unpopular. Generally, the British population is rather intolerant of religious beliefs, as a recent study of public attitudes shows (Voas & Ling Reference Voas, Ling and Park2009). Thus, minorities' religious involvement is often perceived with distrust. This negativity is especially pertinent in the context of the Muslim minority, who often stand accused of prioritising their religious loyalties over their British identity (Field Reference Field2007). Yet, the presence of a state church (the Church of England) and an array of laws recognising religious rights, freedoms as well as the more recent inclusion of religion in anti‐discrimination legislation separate Britain from such secularist countries as France. As Eggert and Giugni (Reference Eggert, Giugni, Morales and Giugni2011) suggest, Britain has tended towards a pluralist approach to cultural groups' rights, which may provide opportunities for religious groups to facilitate political action.

The most important advantage of studying the case of Great Britain, however, is the wide array of non‐Christian religions that can be studied and compared. Britain is unique in this regard: both the United States and most European countries will only have Christianity and Islam readily available for comparison. As we will argue later, the chance to look at a wider set of religions opens an opportunity to advance our understanding of the link between minority political participation and historically salient ethno‐religious identities, as well as to extend theories of the role of religion in politics to more world religions.

Existing literature shows that ethnic minorities in Britain are much more religious than the white majority and attend their places of worship more regularly (Voas & Crockett Reference Voas and Crockett2005). In the 2010 British Election Study, only 36 per cent of the general population said they attended religious worship more than just on festivals, whereas almost 70 per cent of ethnic minorities declared doing so in the accompanying 2010 Ethnic Minorities British Election Study (EMBES). In fact, the rates of religious participation of British minorities are comparable to the levels of worship found in the United States (Putnam & Campbell Reference Putnam and Campbell2010). But do these religious activities mobilise minorities politically? We will show that religious attendance does, generally, contribute to increased levels of participation. However, we will also argue that minority religions differ in how much they are associated with histories of political struggle (both in their homeland and in Britain) and that this is reflected in how effective these religions are at mobilising their faithful to participate in contemporary British politics.

This article will proceed as follows. We will first consider how and why theories linking religious attendance and political participation may apply in the British case. In particular, we will discuss potential mediating and moderating mechanisms for explaining the association between attendance and participation. The ensuing sections of the article will deal with the data, measurement issues and analysis. Finally, we will discuss the implications of our findings for the wider treatment of the political role of religious involvement.

Religious attendance and political participation of racial and ethnic minorities

In the United States, religious attendance has been shown to increase electoral participation (Peterson Reference Peterson1992; Wilcox & Sigelman Reference Wilcox and Sigelman2001), other forms of political participation (Beyerlein & Chaves Reference Beyerlein and Chaves2003) and other civic activities (Becker & Dhingra Reference Becker and Dhingra2001; Beyerlein & Hip Reference Beyerlein and Hip2006). Two main mediating mechanisms have been identified: the acquisition of political resources through attendance, and direct political mobilisation from the places of worship. In their seminal work, Verba et al. (Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995) proposed that racial minorities are usually resource‐poor and lack the basic civic skills needed to participate. For these minorities, religious involvement is a major route for acquiring civic skills. While Verba et al. (Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995) focused mostly on the practical civic skills learned through religious participation, Calhoun‐Brown (Reference Calhoun‐Brown1996) showed that regular attendance in religious activities increased relevant psychological resources such as political trust, political efficacy and racial consciousness (a particularly important predictor of African Americans' political mobilisation; see Chong & Rogers Reference Chong and Rogers2005). However, others have argued that it is the direct political mobilisation coming from the place of worship that matters (Brown & Brown Reference Brown and Brown2003; Djupe & Gilbert Reference Djupe and Gilbert2006). Some individual congregations choose to engage in more direct political debate and activity than others, and in this way influence the political participation of their members. Therefore, it is the efforts of these specific, individual ‘political churches’ rather than attendance per se that politically mobilises the faithful.

Apart from these two mediating mechanisms, there are two possible moderating mechanisms that may alter the relationship between attendance and political participation. In particular, politicised black churches in the United States, predominantly attended by African Americans, have been shown to be more effective than other churches in mobilising the political participation of their worshippers (Olsen Reference Olsen1970; Verba et al. Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995; Calhoun‐Brown Reference Calhoun‐Brown1996). Calhoun‐Brown (Reference Calhoun‐Brown1996) argued that regular attendance at the highly politicised black churches was more effective in raising the levels of mediating psychological resources, especially a sense of group racial consciousness. We argue that this moderating effect of the type of church could have two different explanations: it could arise as a consequence of the predominantly co‐ethnic composition of the place of worship and the resulting ethnic social capital; or it could arise as a consequence of places of worship articulating or promoting politicised identities arising from histories of ethno‐religious struggle or shared ethno‐religious grievances.

With respect to the first possibility, although the moderating effect of black churches is thought to originate from the central role they played in the civil rights movement among African Americans, Jones‐Correa and Leal (Reference Jones‐Correa and Leal2001) found that the ethnic make‐up of the church also matters for the levels of participation of Latinos, whose mass immigration to the United States came after the civil rights movement. Jones‐Correa and Leal argue that this is probably because attending majority‐Latino churches increases the sense of ethnic community and in turn increases the chances that Latino church members will engage in community‐based political action. This explanation parallels the emphasis in European research on the role of ethnic social capital on minority political participation (Fennema & Tillie Reference Fennema and Tillie1999; Jacobs & Tillie Reference Jacobs and Tillie2004; Morales & Giugni Reference Morales and Giugni2011; Maxwell Reference Maxwell2010). Particularly relevant in this respect is the work of Klandermans et al. (Reference Klandermans, Van der Toorn and Van Stekelenburg2008), who show the moderating effect of social embeddedness on the relationship between a sense of political efficacy and political participation.

A second possible explanation for the moderating effect of place of worship is that, in cases where they are associated with a politicised minority group, places of worship may act as vehicles for the articulation and expression of political concerns and hence stimulate political participation among attendees. According to this line of argument (which has some parallels with the historical political role of black churches in the United States), it is not so much the ethnic composition and social embeddedness of worshippers as the historical political concerns and grievances of the ethno‐religious community that are crucial.

Among British ethnic minorities, who predominantly immigrated after the Second World War and thereafter from South Asia, Africa and the Caribbean, these historical political concerns and politicised identities are especially notable among Sikhs and Muslims, whereas they are much less marked among Hindus or Christians. Our hypothesis, therefore, is that it is in the case of Sikhs and Muslims that the effects of attendance on participation will be stronger, whereas they will be weaker among Hindus and Christians. We briefly review the historical backgrounds of these four religious traditions in order to support this expectation.

Muslims came to Britain mostly from Pakistan, to a lesser extent Bangladesh and more recently from Africa, so they are a fairly diverse group. Nonetheless, Pakistani Muslims are dominant demographically and politically. In the United Kingdom, Muslims face a complex political context. On the one hand, Islam is considered a socially conservative and insular religion (Georgiadis & Manning Reference Georgiadis and Manning2011). In parallel to some Protestant evangelical denominations, who were found to encourage more inward, church‐oriented participation or a more insular outlook and self‐segregation from the mainstream (Wuthnow Reference Wuthnow, Skocpol and Fiorina1999; Park & Smith, Reference Park and Smith2000; Lam, Reference Lam2002; Schwadel Reference Schwadel2005; Driskell et al. Reference Driskell, Embry and Lyon2008), this would give rise to the expectation that regular mosque attendance could discourage mainstream political engagement. This chimes in with the allegations that some British Muslims consider engaging in British politics as validating a non‐Islamic (haram) rule, which runs against their understanding of the prescriptions of Islam (BBC 2010). On the other hand, the literature on British Muslims' political attitudes paints them as a well‐adjusted and politically well‐integrated group (Maxwell Reference Maxwell2010), and Muslims in the United Kingdom appear to be politically well‐organised and represented (with the number of MPs of Muslim origin having grown from two to eight after the 2010 parliamentary elections).

Muslim politicisation in the United Kingdom springs from a variety of international conflicts in which Muslims are thought to be victims, and their perceived victimisation as a religious group in the United Kingdom. The main such conflict imported into British Muslim politics is over the Kashmir region, which is contested between Pakistan and India, and from where many British Muslims originate (Werbner Reference Werbner, Ember, Ember and Skoggard2005). Also, conflicts such as those in Palestine, or Bosnia in the 1990s, gained political attention among British Muslims, and may be linked to the rise in political salience of Muslim identity (Werbner Reference Werbner, Ember, Ember and Skoggard2005). Domestically, the emergence of Muslim political leadership in Britain, such as the Muslim Council of Britain, can be traced back to the 1980s and the Rushdie affair, during which many Muslims mobilised to protest against the publication of Salman Rushdie's book The Satanic Verses – a book they thought offensive to Islam. As a result they were the first South Asian community to organise politically, and many of the organisations and leaders that emerged then remain important political players (Malik Reference Malik2009). Finally, Muslims in Britain are increasingly the main group against which prejudice is openly expressed both by the ideological left and right in Britain (Choudhury Reference Choudhury, d'Appolonia and Reich2009). Muslims also have an additional potential political grievance as they are economically disadvantaged in Britain (Office for National Statistics 2004; Khattab Reference Khattab2009). This group thus offers the closest comparison to African Americans' mobilisation against racism and disadvantage.

Sikhism is the second highly‐politicised minority religion in Britain. While Sikhs in Britain are diverse both in terms of geographic origin and caste (although less so than the Hindu Indians), most Sikhs originate from Punjab in India and many speak Punjabi. Crucially, Sikhism is not only a religion but is also an ethnic identity, akin to Judaism. Elements of military struggle for independence have permeated this religion from its inception, and it is part of traditional Sikh culture. Sikhs have experienced an oppressed minority status even in their Indian homeland. Their struggle for independence reached its zenith in the 1980s, and culminated in the tragic massacre in the Golden Temple in Amritsar, Punjab, where the Indian army killed many civilians in their effort to clamp down on Sikh separatists. This event is thought to be a direct cause for the 1984 assassination of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards. This event received a lot of attention, with some British Sikh politicians allegedly supporting the assassination. Footnote 19 The Sikhs' homeland political struggle with the Indian state has been imported to Britain (Singh & Tatla Reference Singh and Tatla2006: 102). In addition, Sikh places of worship (gurdwaras) are centres not only of community life, but also of the political life of Sikhs in Britain (Singh & Tatla Reference Singh and Tatla2006: pp. 127, 134). Sikh political organisations mobilise explicitly through their control of gurdwaras, from which they draw their followers and resources (Singh & Tatla Reference Singh and Tatla2006: 82). As a result, we expect Sikhs to be particularly likely to be religiously mobilised, especially through attendance at gurdwaras.

Hindus in Britain are divided through their two main routes of immigration: direct migration from the Indian sub‐continent and secondary migration from East Africa, where Indians first settled under British colonial rule, but from which they were forced out during the African states' struggles for independence. Overlapping with this are additional divergences of class, caste, region of origin and language. Despite this diversity, the British Hindu population arrived in Britain with more education, transferable skills and often with greater English fluency than other minorities (Office for National Statistics 2004). Consequently they have been more successful in terms of socioeconomic advancement than most other minority groups. Their social diversity, as well as lack of major grievances, has resulted in a lack of shared political identity and organisation and hence low levels of politicisation around religious belonging (Vertovec Reference Vertovec and van der Veer1995). Hence, we do not expect British Hindus to be particularly mobilised by their temple (mandir).

Ethnic minority Christians are the most diverse religious group: while most Caribbeans are Christians, there are also many African and Indian‐origin Christians in the United Kingdom. There are also important denominational differences. As a result, we do not expect there to be any shared historical concerns and grievances or distinctive politicised identities among minority Christians. Having said that, there are reasons to believe that minority Christians may be politically engaged. First of all, many ethnic minority Christians belong to protestant denominations, which in the classic American literature are considered to put more value on teaching the civic skills necessary for political participation. Also, some of these denominations, particularly Pentecostal, are traditionally associated with black Christians and may be expected to have the same effect as black churches in the United States.

Our hypotheses, then, are that regular attendance at a place of worship increases minority political participation, and that this effect is mediated both by the psychological resources (including racial consciousness) which regular attendance develops and by direct encouragement from the place of worship. We also hypothesise that the effect of attendance on participation is moderated by the character of the place of worship: this might be either a result of the community processes at an ethnically homogeneous place of worship, or as a result of the historical political concerns and politicised identities associated with Islam and Sikhism in Britain, but not with Hinduism or Christianity.

The claim that religious attendance increases participation is causal, but this causality can always be contested in non‐experimental research. Some critics posit that the influence of attendance is simply because religiously active people are generalist ‘joiners’ and therefore have an overall tendency to participate in many forms of public life (Van der Meer & Van Ingen 2009). While in cross‐sectional research one cannot definitively identify causal effects, we propose to take account of any ‘generalist’ joining tendency by controlling in our analysis for non‐political associational involvement, which we think is a reasonable proxy for a general tendency to participate in public life. Furthermore, by proposing specific hypotheses about mediators and moderators, we can narrow down the search for causation to precisely defined causal mechanisms. Again, this cannot be definitive, but a mechanism‐based approach offers the possibility of greater confidence in one's causal claims.

Data and measurement

We use the 2010 Ethnic Minority British Election Survey (EMBES) (Heath et al Reference Heath2010). EMBES contains 2,787 minority respondents, composed of the following: Indian 587, Pakistani 668, Bangladeshi 270, Caribbean 597 and African 524. Of these respondents, 2,410 declared that they belong to a religion: 1,140 to Islam, 841 to Christianity, 234 to Hinduism and 164 to Sikhism. These are the main religions in the United Kingdom and we have therefore limited our analyses to them.

Our outcome measures are electoral and non‐electoral political participation. Electoral participation is measured as a validated vote at the last parliamentary election in 2010, which was validated using administrative records, enabling us to correct for over‐reporting of turnout. For the respondents who did not express their consent to match vote validation to their survey responses, turnout was imputed. Footnote 20 Five measures were used to capture the less ubiquitous non‐electoral participation, with respondents who engaged in any of the five activities in the 12 months preceding the 2010 election coded as participants. The activities were: being active in a political voluntary organisation; donating money to a political cause; attending a demonstration; signing a petition; and boycotting or buying a product on political grounds. Since all of these forms of participation are quite different, they have been analysed separately as well as together, but the results of the separate analyses did not depart from what is presented here. Factor analysis confirmed that these activities formed one factor, although reliability was relatively poor at 0.56.

We use two measures of religious involvement: whether respondents consider themselves as belonging to a religion, and religious attendance. We coded those who attended their place of worship at least once a month as attending regularly.

To test the first set of mediating mechanisms, we include measures of psychological resources: political trust, efficacy and the perception of racial prejudice (as a proxy for racial consciousness), political knowledge, interest in politics and sense of duty to vote. Footnote 21 To test the second, we include a measure of whether respondents were encouraged to vote in their place of worship.

To test for the two proposed moderating mechanisms we include interaction effects of attendance with co‐ethnicity of the place of worship (coded as 1 when respondents said ‘most’ of their co‐worshippers are from the same ethnic group as themselves), and with religious tradition (Christian, Muslim, Hindu and Sikh).

All multivariate models include demographic controls: age, gender, class (middle or working), education (degree, A‐level equivalent, and anything below as reference category), house tenure (homeowner, social housing and renting privately as reference category) and local area deprivation. We also control for being born in Britain or elsewhere, and for fluency in English – the lack of which may be a major obstacle to political participation. In the case of voting models, we also include controls for strength of party identity and for external political mobilisation: being contacted by a political party.

To control for the confounding possibility that both political and religious participation are caused by a general tendency to participate in all forms of public life, we also include a measure of other forms of social participation in our models (based on belonging to non‐religious and non‐political organisations and clubs). Measures of associational involvement of this kind have been shown to be powerful predictors of political participation in their own right (see, e.g., Morales & Giugni Reference Morales and Giugni2011; Heath et al. Reference Heath2011, Reference Heath2013).

Setting the scene

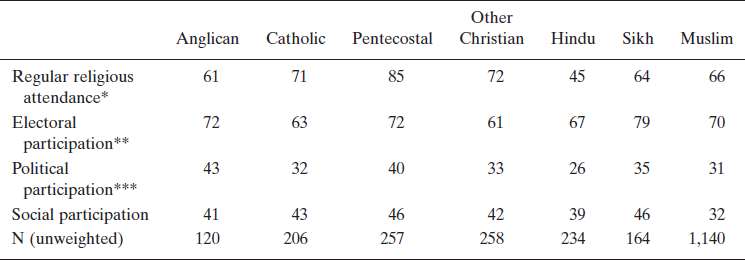

Before we can plausibly argue that religious participation generates political resources to compensate ethnic minorities for their relatively poor socioeconomic resources, we must confirm that religious attendance is in fact a major part of minorities' associational experience. In Table 1 we compare the various forms of social involvement: religious attendance, social participation (in apolitical associations) and the two forms of political participation: electoral and non‐electoral. Regular religious attendance among minorities in Britain is high – above 60 per cent for most groups, apart from Hindus (42 per cent). Importantly, it is the most ubiquitous form of participation in public life, apart from voting. Looking at the relationship between religious attendance and political participation in Table 1 we see that most groups with high levels of attendance also have high levels of participation. There are some exceptions, however – most notably Catholics, who attend their places of worship most often, have average non‐electoral participation rates but low levels of turnout; and the Hindus, who have low attendance and non‐electoral participation, but high turnout. However, the presence of a broad pattern of relationship between attendance and participation conforms to our expectation.

Table 1. Religion and participation in public life (weighted percentages)

Notes: * Attending at least once a month (includes only those who belong to a religion). ** Out of those eligible and registered. *** Having done ANY out of five possible political acts has been coded as participation – see data section.

Source: Heath et al. (Reference Heath2010).

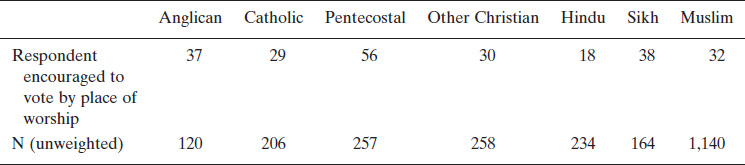

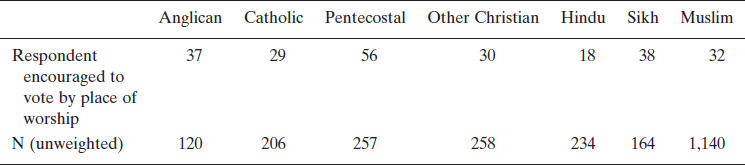

Similarly, before we test whether direct encouragement to vote from a place of worship matters for turnout, we must establish whether places of worship in fact issue any such encouragement. Table 2 shows which religious adherents heard these political messages. We can see that there are some large differences between religions and denominations of Christianity in their approach to politics. Contrary to the hypothesis that Islam is an insular religion, Muslims are not the most inward‐looking and politically shy religion. Although only a third of Muslim respondents had heard a message encouraging them to vote at their mosque, they are not far behind average. In contrast, only 18 per cent of Hindus said that their temple encouraged them to vote. The Christian minorities were the most politicised by their church, but the variations were large: whereas the Pentecostal churches were most likely to encourage their members, Catholics reported the least direct encouragement to vote.

Table 2. Political culture in places of worship (weighted percentages)

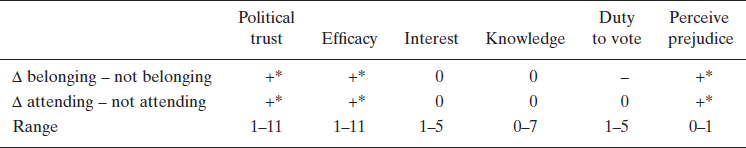

Similarly, before we test whether the effect of religious attendance on political participation is mediated through increased psychological resources, we need to first establish whether there is any relationship between church attendance and levels of psychological resources. Table 3 shows that religious attendance is associated with some, but not all, of the suggested psychological resources. It does not have a relationship with the sense of duty to vote, which undermines the theory that church instils participatory norms (Olsen Reference Olsen1970) – or interest in politics, or political knowledge. These variables, as a result, will now be treated as controls rather than mediators in our multivariate analysis. However, attendance is correlated with levels of the resources included by Calhoun‐Brown (Reference Calhoun‐Brown1996): those who attend church regularly have higher levels of political efficacy and trust, and they perceive more racial prejudice than those who do not attend. Interestingly, these resources are also higher among those who do not attend regularly but report belonging to a religion than among those who do not belong at all.

Table 3. Differences in psychological resources by religious belonging and attendance (N = 2,787)

Notes: * Differences significant at 0.000 level. ‘+’ indicates higher levels of resources among those who belong to a religion as opposed to those who don't belong to one, and among those who attend regularly in comparison to those who do not attend regularly but belong to a religion.

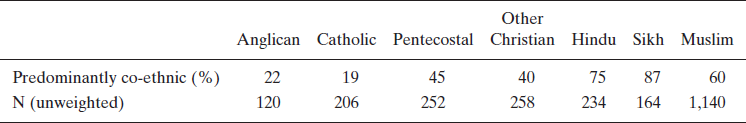

Finally, before considering whether co‐ethnic places of worship perform better at mobilising their members to participate in politics, we must investigate how many religions had predominantly majority‐minority places of worship. Table 4 shows that there is considerable variation between religious groups; most Hindus (75 per cent), Sikhs (87 per cent) and Muslims (60 per cent) attend ethnically homogenous places of worship, whereas the Christians attend more diverse churches. Among denominations, Pentecostals attend co‐ethnic churches most often (45 per cent) and Catholics the least (only 19 per cent). This is explained to a great degree by the differences in the ethnic diversity of religions and denominations in Britain.

Table 4. Proportion of majority co‐ ethnic places of worship by religion and denomination

Note: Those who refused to specify their religion are excluded.

Impact of regular religious attendance on political participation in Britain

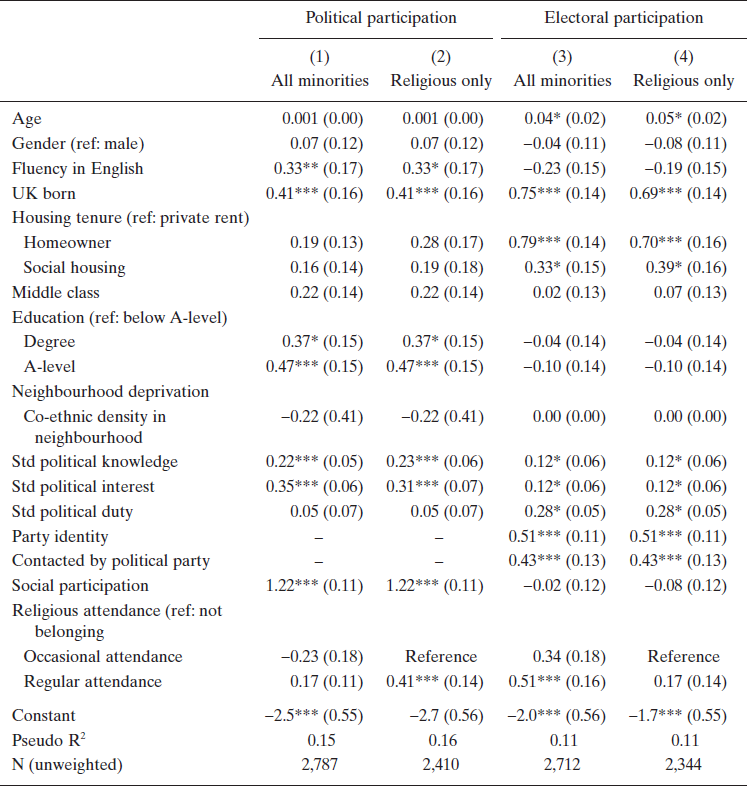

We now turn to multivariate data analysis of non‐electoral participation and of voting, respectively. Initially, we look at the impact of religious attendance on political participation controlling for the usual predictors, but not trying to establish what mechanisms mediate or moderate this impact. For both types of political participation we present two logistic regression models: one for the entire sample of minorities and the other for minorities who reported belonging to a religion (Table 5). In the first model, for all minorities, we introduce the usual sociodemographic controls (including political resources such as interest and knowledge, which did not correlate with religious attendance), plus place of birth and fluency in English. At this stage we also introduce the control for the possibly confounding influence of the general tendency to participate, measured here by social participation, and controls for ethnic origin (which were not in fact significant and therefore are not included in the final models shown). In this first model we include respondents who declared no religious belonging as a reference group against which those who belong but do not attend regularly and those who attend regularly are compared. In the second model we exclude those who declared no belonging and directly compare regular attendance with occasional attendance.

Table 5. Impact of regular religious attendance on political and electoral participation

Notes: Data are weighted and standard errors are adjusted for clustering as a result of sample design. Statistical significance levels: *** p ≤ 0.001; ** p ≤ 0.01; * p ≤ 0.05. Std = variables standardised.

The first two columns in Table 5 present models of non‐electoral political participation. When we look at the model for all minorities (model 1) and for those belonging to a religion only (model 2) we see that, the controls operate in the expected way. In model 1 neither the parameter estimate for occasional attendance nor regular attendance is significantly different from the reference category (non‐membership), but model 2, which excludes those who said they did not belong to a religion, shows that the difference between occasional and regular attendance is indeed statistically significant, supporting our hypothesis that regular religious attendance increases political participation. Further analysis shows that the difference amounts to five percentage points. Footnote 22 Crucially, this effect holds after controlling for social participation thus signalling that a distinct causal effect of attendance – apart from the general tendency to participate in public life – is plausible. In its own right, social participation is a large and significant positive predictor of non‐electoral participation.

Looking at the last two columns in Table 5, which present models for voter turnout, contrary to what we found for non‐electoral participation, regular religious attendance is a significant and positive predictor of turnout, when compared with the reference category of people who did not belong to any religion (model 3), although the difference between occasional and regular attendees does not reach statistical significance (model 4). Hence, religious belonging, not attendance, does most of the work in the case of turnout. Also in contrast to non‐electoral participation, the effect of social participation is tiny and non‐significant.

Mediating and moderating mechanisms

We now turn to examine the two mediating and two moderating effects suggested by the literature. For any mediating mechanism to be observed, preliminary tests must be conducted to establish that the mediated variable is in fact related to the outcome variable (this has been done in Table 5 where we show that attendance does impact political participation) and that the mediated variable and the mediating mechanism are also correlated (this has been done in Table 3 where we show that political resources correlated with regular attendance). We did not show the relationship between hearing direct encouragement to vote in the place of worship and attendance in Table 3, but we did confirm this had a relationship with regular attendance. Of the EMBES respondents who belonged to a religion, but did not attend regularly, 20 per cent reported that they heard direct encouragement messages, compared to 40 per cent of those who attended their places of worship regularly.

In this section, we turn to the final step, in which we will observe if there is any reduction in the impact of the mediated variable (attendance) on the outcome variable (participation) when the mediating mechanism is introduced. We will also test the two proposed moderating effects: with ethnically homogeneous places of worship better at mobilising their worshipers; and regular attendance increasing political participation among Muslims and Sikhs but not among Hindus and Christians. We expected significant interaction effects between regular attendance and the moderating variables.

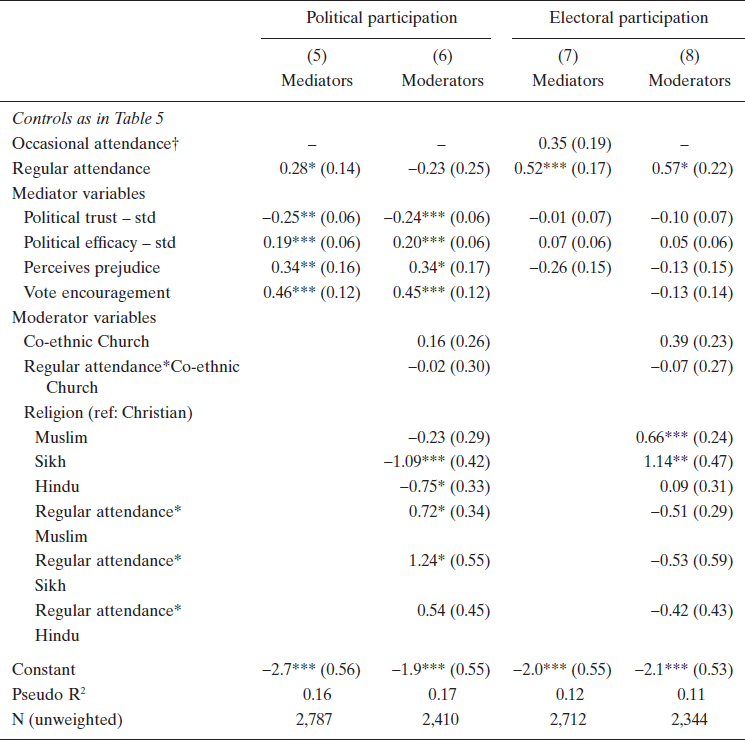

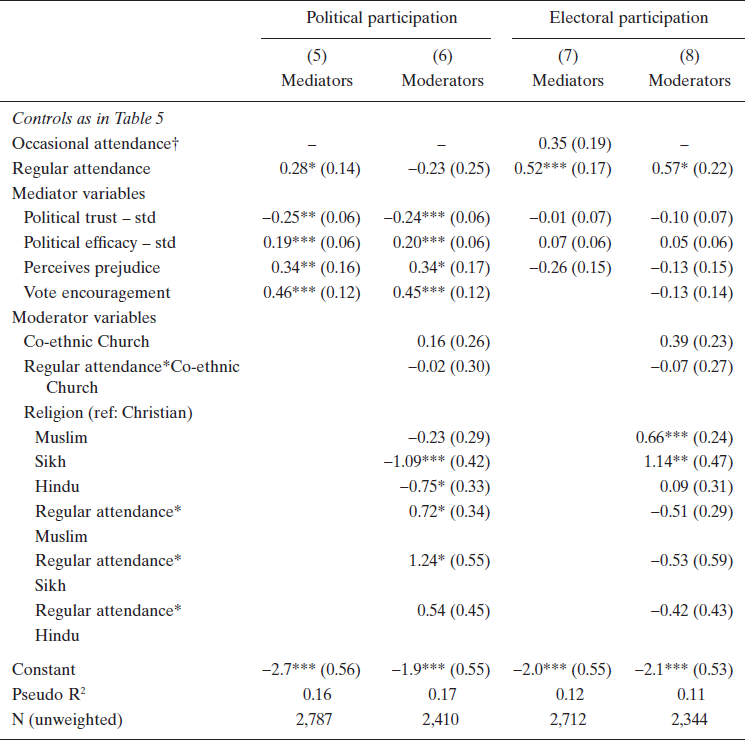

We added mediating and moderating effects to the base models presented in Table 5 for each of non‐electoral and electoral participation. Therefore, to compare the impact of moderating and mediating variables on the religious attendance main effect we need to compare Table 5 with Table 6 Footnote 23: model 2 with models 5 and 6, and model 4 with models 7 and 8. We present the analysis of mediating and moderating mechanisms for religious respondents only for non‐electoral political participation as the first step models presented in Table 5 showed regular attendance as a significant effect in the model for religious minorities only.

Table 6. Mediating and moderating mechanisms for the impact of regular religious attendance on political and electoral participation

Notes: Data are weighted and standard errors are adjusted for clustering as a result of sample design. Statistical significance levels: *** p ≤ 0.001; ** p ≤ 0.01; * p ≤ 0.05. Std = variables standardised. † For models 5, 6 and 8, only religious respondents are included; therefore, ‘Occasional attendance’ is the reference category.

First, looking at the two models for non‐electoral political participation (the first two columns in Table 6) we see that all our mediating variables are statistically significant. Sense of efficacy and perception of prejudice both have positive and statistically significant impacts, while political trust has a significant negative impact. Hearing a political message in a place of worship increases the probability of participation by ten percentage points. We can also see that there has been a reduction in the size of the effect of regular attendance after the introduction of controls (if one compares it to the base model 2 from Table 5) from 0.41 to 0.28, although it remains borderline significant. As a result, we feel that the mediators do mediate some, but not all, of the impact of religious attendance on political participation.

The impact of moderating variables is rather more uneven. Looking at model 6 in Table 6, attending an ethnically homogenous church does not have a significant impact on political participation in its own right, or as a moderator in interaction with regular attendance. The effect of regular attendance does, however, seem to depend on which religion is involved. Christianity is the reference category in this model. First, we find that Hindus, who are the group least politicised in the United Kingdom, are less likely to engage in non‐electoral participation than Christians, and that this holds equally true for occasional and regular attendees alike. Sikhs, who are the most politicised religious group, are – as we expected – more politicised by their place of worship in contrast. While those Sikhs who attend occasionally are much less likely to participate than Christians who do not worship regularly, regularly attending Sikhs are 14 percentage points more likely to participate than Sikhs who attend only occasionally. Muslims who do not regularly attend are as likely as Christians to participate, but – again as we expected – regular attendance in a mosque increases the probability of participation by seven percentage points. Finally, while as we saw in Table 2, minority ethnic Christians are encouraged to vote in their places of worship more than other minorities, their church attendance has a weaker relationship with political engagement than for Sikhs and Muslims.

Turning now to the last two columns in Table 6 – the models for turnout – we observe that none of the hypothesised mediating mechanisms have a significant effect on turnout, which is especially surprising in the case of direct encouragement to vote. Consequently, the effect of regular attendance on vote remains unchanged from the base model 3 in Table 5. To test our moderating mechanisms in model 8, we include the religious minorities only. We again introduce the measure of ethnically homogenous place of worship and moderating effects of different religious traditions on the impact of regular attendance. Similarly to what we saw for non‐electoral participation, members of a co‐ethnic church who attend regularly are not more likely to vote than those who regularly attend non co‐ethnic places of worship. Thus, both in terms of electoral and non‐electoral participation, we see no special impact of a co‐ethnic place of worship. Again, however, we see some interesting effects of individual religions. The main effect coefficient parameters, translated into predicted probabilities, show that among those minorities who attend only occasionally, Muslims are five points and Sikhs 12 points more likely to vote than occasionally attending Christians. This gives a picture of higher overall levels of electoral participation among these two religious groups, but since the interaction terms for these groups are of a similar size but in the opposite direction as the main effect of regular attendance, the model overall suggests that turnout does not vary with the frequency of attendance for Sikhs and Muslims. A similar story of compensating interaction and attendance main effect is true for Hindus, but without a strong Hindu main effect. In contrast, Christians who attend regularly are significantly more likely to vote than occasional Christian attendees. This is further confirmed by running separate regressions for each religious group separately (not shown), which confirms that regular attendance has a significant impact only on Christian minorities' turnout.

Conclusions

Our analysis has shown that in the 2010 British Parliamentary Elections regular religious attendance was associated with increased levels of political participation among racial and ethnic minorities, similarly to what has been found in the United States. Religious attendance is one of the main forms of associational life among racial and ethnic minorities, and functions as an important source of political mobilisation in both countries. We found that many minority groups who regularly attended were more likely to participate in non‐electoral activities and to vote. Our evidence on the mediating mechanisms is consistent with the hypothesis that attendance bolsters the psychological resources that directly contribute to non‐electoral political participation – namely political efficacy and a perception of racial prejudice (Calhoun‐Brown Reference Calhoun‐Brown1996). We also found that the political culture of a place of worship (measured by direct encouragement to vote) had a significant, direct effect on participation as is the case in the United States (Calhoun‐Brown Reference Calhoun‐Brown1996; Djupe and Grant Reference Djupe and Grant2001) – although surprisingly only for non‐electoral participation. Overall we can conclude that religious attendance is a significant political resource for ethnic minorities in Britain.

The major new finding of this study is that religious attendance has a strong positive effect on non‐electoral participation in the case of those religions – Islam and Sikhism – that are politically salient, but not in the case of Hinduism, which is not politicised in Britain to the same extent. In this way, out of the three proposed mechanisms through which religion might influence political participation, it is the notion of a highly politicised religion that finds most support. Christianity presents a more complex case, where regular attendance bolsters electoral, but not non‐electoral participation, which chimes with the fact that Christians are most likely to hear direct messages encouraging them to vote in their churches.

We hypothesised that the effect of religious attendance could be mediated through increased psychological resources, such as racial consciousness, but the effect of the separate religious traditions remained significant after controlling for this mechanism. We also thought that the attendance effect could be a proxy for ethnic social capital and other forms of co‐ethnic mobilisation, but we found that co‐ethnicity of the place of worship was non‐significant. In the end, it was our expectations developed by looking at religions' political history and struggles in their countries of origin and/or destination that were met. In our study, the gurdwaras and mosques seem equivalent to the African American black churches in the United States, implying that it is the history of political engagement through one's religious group or place of worship and not a general tendency to join, or a mere experience of attendance, that drives the link between regular attendance and political engagement for racial and minority groups. The history of homeland political struggles of Sikhs, the current political salience of Islamophobia in Britain and of international conflicts involving Muslims appear to be crucial.

While our results in many respects mirror those found in the United States, it is important not to generalise them too rashly. As Eggert and Giugni (Reference Eggert, Giugni, Morales and Giugni2011) convincingly argue, the role of religion in political mobilisation may be contingent on the opportunity structures provided by national political contexts. We would also add to this that the political salience of religion matters as well, and in the British context we can see that this can be generalised beyond Islam – arguably the most politicised religion in European society. Nevertheless, to find a comparable relationship between religious attendance and political participation, and support for two of the proposed explanatory mechanisms, in a different context, shows that the general theory of religion and politics can be a useful analytical framework in other countries and religions. We also hope that our distinction between mediating and moderating mechanisms will remain a useful organisational principle in any future studies of the relationship between religious attendance and political participation.

Acknowledgements

First of all we would like to thank the Economic and Social Research Council who generously funded this research (grant number ES/G038341/1). This article has been presented at the Council for European Studies conference in Barcelona and the European Consortium for Political Research conference in Reykjavik. We would like to thank our discussants and members of the audience who made many insightful comments. Last but not least, we thank the EJPR editors and anonymous reviewers for all their help in improving this manuscript.