When the Peruvian scholar José Eusebio Llano Zapata travelled to Spain in the middle of the eighteenth century, he remarked on the difference between the book markets in a letter to the Archbishop of Charcas: ‘The publications of Elzevir, Gryphius, and Stefanos, which today can hardly be found in Europe; there is no market, thrift store, or junk shop in our America, principally in Lima, which would not sell them’.Footnote 1 Llano Zapata highlighted the contrast between the two markets, and to him it was back home, in the Viceroyalty of Peru, not in Spain, where the titles of the celebrated European printing families were readily available. In his luggage from Lima he had even packed two books, originally published in the German city of Mainz, which he believed to be very rare. He concluded his observations by stating that ‘[o]f Italian, French, and Portuguese books, for almost a century now, there are so many that have been brought to these countries [in Spanish America] that today […] through the trade, these have become known to the American erudite men and also to […] women’.Footnote 2 The Peruvian scholar who had travelled across the Atlantic and had experienced both places clearly judged the colonial book market favourably, as bearing comparison with Europe. In characterising the trade, he emphasised the wide variety of available books, their different publication sites, as well as the various locations of book sales in the capital of Lima. In addition, he outlined a broad readership composed of both men and women, conveying the impression that books were generally available at the time. In the following decades, more and more people in colonial society gained access to locally printed and imported books.

This is a social history of books in late colonial Peru during the Age of Enlightenment. By tracing print publications as commodities that circulated in the specific social setting of the Viceroyalty of Peru during the last decades of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth, A Colonial Book Market studies these publications as material objects, in quotidian use. To date, we have no comprehensive framework to analyse the scale, geography, and practices of either local production or the import trade, which together account for the volume of distribution and acquisition of books on the colonial market. Much attention has been paid to the circulation of single political writings containing revolutionary ideas, and to prohibited books, which, however, were owned by very few people. While research has concentrated on the distinguished libraries of erudite individuals and illustrious authorities, the interplay between print production, import trade, and the circulation of books in the Age of Enlightenment, as designed for broad parts of the population, mostly eludes us.

The Enlightenment, at the same time an idea, a movement, and a global project, characterised a whole era that had started in the early eighteenth century. As a key term of the age, used and discussed by contemporaries themselves both in Spanish America and in Europe, the Enlightenment is a contested term of scholarship that needs to be understood in its specific contexts. Colonial power relations shaped the rise of printed words, a critical component in the Age of Enlightenment. Though the printing press did not serve as an agent of revolutionary change in Peru, the profound impact of the expanding print culture transformed daily life with enlightened tendencies. Among other things, reading material encouraged self-study, communicated new ideas, stimulated critical debates, and conveyed practical knowledge. To appreciate the Enlightenment in the Viceroyalty of Peru, and Spanish America more broadly, we need to consider not only celebrated European authors, in particular the prominent Spanish authors of enlightened thought, such as Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes, Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, and Fray Benito Jerónimo Feijóo, who were all readily available on the colonial book market, but moreover the new practices of access to and uses of print. This study will not focus on particular authors or single texts, but instead on printers, traders, and book possessors who made use of the Enlightenment as a print practice in which many participated. Considering diverse modes of reception and popular uses of print in Peruvian cities, this study reveals how a larger mass of printed commodities than ever before was available to a diverse customer group.

Against the division between a small, lettered elite and the majority of illiterate people in Peru, A Colonial Book Market attempts to show how ordinary individuals from various backgrounds accessed print and possessed books. While, of course, not all reading matter contained practical knowledge in an enlightened sense but provided, for instance, entertainment, religious meditation, or royal propaganda, the period was characterised by a new and growing participation in print culture. A Colonial Book Market weaves two claims into a central argument. Its first claim is that, by import and through Limeño production, the book market was quantitatively large and qualitatively diverse. It was from the 1760s onwards that workshops in Lima and transoceanic imports supplied the Peruvian market with unprecedented quantities of print publications, including books, leading to a diversity of reading material. The second claim concerns the locations of printing and selling, and unveils an integrated trade and everyday contact zone in the marketplace where customers of different backgrounds encountered books, exchanging and handing the items on to others. Through this composite book market in late colonial Peru, which is set out in the two claims, more people than ever before had access to print and, by this, participated in the Enlightenment project. This is not to say that print was a mass medium or to deny that the book market was controlled mainly by the Spanish-speaking elements of society. It is to say, however, that despite its limits and the restrictions in place, by the late eighteenth century print publications were a daily commodity within the reach of many men and women living in Lima and other parts of the viceroyalty.

Peru offers a particularly interesting site to investigate the role of books in colonial society. In colonial contexts, and especially in the process of imperial expansion and consolidation, the printing press had turned into a critical tool for colonial administrators and others that was often contested and used for own ends.Footnote 3 Forming an important part of the Spanish realm, the Viceroyalty of Peru was officially not a colony, yet the development of print culture and its book market depended directly on Spain.Footnote 4 Its circumstances were marked by a particular historical setting: a typographical tradition in the capital reaching back as far as 1584, the distance from other book trading centres, its longstanding trade and political connections with the European market, and its highly stratified and diverse society with unequal access to education. In this setting, Peruvian readers partook in the print culture of their time to an extent that is comparable to other sites, such as Western Europe and British America. Unlike other forms of cultural production, books were especially mobile objects, printed both in Lima and abroad, traded across borders, marketed in the cities at various sites, and sold, resold, or passed on to someone else who was interested, transgressing social divisions in the process. Following such itineraries, this social history of reading material in Peru is a contribution to acknowledging the book as a medium in societies that are considered peripheral to the developments of both print culture and the Enlightenment. Against an increasing reductionism in Enlightenment studies that limits the field to certain print genres, geographical areas, and classes of readers, A Colonial Book Market offers a different approach by integrating new modes of making and consuming print.

Lima, with the old name City of Kings (Ciudad de los Reyes), was an attraction on the South American continent. As the high court of the Spanish crown and seat of the viceroyalty, the audiencia capital presided over a vast region through the centralisation of power: the Viceregal Palace, the old University of San Marcos, archiepiscopal institutions, and the courthouses were all located in the bustling city that formed the political centre.Footnote 5 A considerable number of professionals, producing texts and interested in books, had made Lima a suitable place to set up and run printing businesses.Footnote 6 After Mexico, where a press had existed since 1539, Lima was the second place with a printing press in the Americas, continuously operating from 1584 on.Footnote 7 Until late into the eighteenth century, it was the only place of continuous printing production on the whole continent – apart from individual publication enterprises by the Jesuits at other sites. Established about a century after the first workshops in Europe and pre-dating activities in the British American realms by half a century,Footnote 8 printing in the Peruvian capital had a longstanding typographic tradition. Through its position of power, Lima had developed into the ‘lettered city’ par excellence.Footnote 9

The meaning of the book in colonial Peru connects extensively with the act of alphabetic writing – in a society largely based on orality.Footnote 10 The gradual spread of literacy transformed society’s practices through standardising forms of expression and the emergence of a single common language: Spanish, which however was not the language of the majority, who spoke Quechua or other indigenous languages. The topic of writing and power in Spanish America has been famously addressed by Angel Rama’s concept of the ‘lettered city’, which has defined the colonial space as highly hierarchical, largely due to a network of signs and literacy in which only a few participated.Footnote 11 Though literacy was an essential prerequisite for the very small colonial elite, it was not their exclusive domain.Footnote 12 While print culture was no longer restricted to the upper classes alone – as A Colonial Book Market contends – books circulated above all in urban spaces. Lima’s position within the book market was unparalleled due to both the printing workshops and the connection to the harbour at Callao. Protected by a monopoly, the harbour built the economic gateway for trade in a wide array of products, among them books, stimulating commercial life in the capital from which redistribution was organised to other major cities where, apart from individual consignments to rural areas, the trade concentrated. Among the major cities in the viceroyalty were Arequipa, Cuzco, and Trujillo, which were also primary places of book consumption. As ceremonial, administrative, and social urban centres, the cities experienced important commercial and cultural activity. Their leading role as trade centres led to a comparatively large and diverse population (Table 0.1).

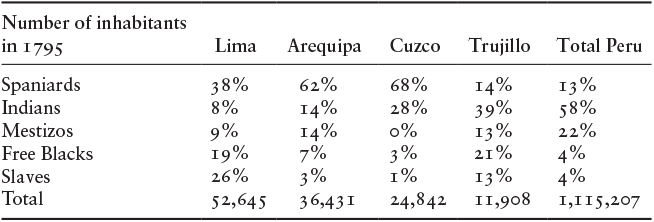

Table 0.1 Population of Peru in some major cities with its ethno-social distribution as counted in colonial terms in 1795.

| Number of inhabitants in 1795 | Lima | Arequipa | Cuzco | Trujillo | Total Peru |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spaniards | 38% | 62% | 68% | 14% | 13% |

| Indians | 8% | 14% | 28% | 39% | 58% |

| Mestizos | 9% | 14% | 0% | 13% | 22% |

| Free Blacks | 19% | 7% | 3% | 21% | 4% |

| Slaves | 26% | 3% | 1% | 13% | 4% |

| Total | 52,645 | 36,431 | 24,842 | 11,908 | 1,115,207 |

Note: Percentage calculated from numbers cited in Fisher, Government and Society, 251–253, Appendix 2, based on AGI, Indiferente General 1525. Rounding errors in sums have been corrected. Different numbers, based on other categories, are offered by the Guía from 1793, citing the census the year before: Unanue, Guía política, eclesiástica y militar … 1793, 1, 77, 94–95, 117. For a criticism of the population data drawn from the colonial census counts, Browning and Robinson, ‘The Origin and Comparability’. On the long-term development of Lima’s population, compiling data from 1570 (12,000 inhabitants) to 1876 (more than 101,000 inhabitants), see Haitin, Late Colonial Lima, 193–197.

Not only did the census of the time state the number of inhabitants, it also measured the lineage categories of the mixed society. In general Spaniards, counted as Iberian-born peninsulares and American-born criollos, dominated in the cities (although Trujillo was an exception). Ethnicity and purity of blood (limpieza de sangre), kinship and gender, good manners and economic resources constituted the principal determinants of social status in the Viceroyalty of Peru. They also defined a person’s education and occupation. Yet towards the end of the eighteenth century, cross-ethnic contacts increasingly subverted the normative boundaries that colonial authorities tried to implement. Due to family relations between Indians, Spaniards, and Africans, ethnic distinctions were diluted, and their common offspring, called castas, were further differentiated by classification terms like mestizo, zambo, or cuarterón.Footnote 13 This was remarkable especially for travellers who came to Peru, such as the Spanish scientist Hipólito Ruiz on his voyage between 1777 and 1788, who described the mixed population in harsh terms.Footnote 14 Against the strict framework of socio-ethnic categories, its permeability or subversion formed part of daily business through legal and cultural negotiations. Scholarship has shown the fluidity of colonial caste categories, for example with exogamous preferences in marriage patterns, especially for indigenous and mestizo groups, or the elegant clothing of slaves.Footnote 15 With its hierarchical and diverse society in addition to Lima’s longstanding typographical tradition, late colonial Peru offers a singular case to investigate the reach and scope of reading material in a colonial context.

Contemporaries described these social changes in Peru, sometimes even manifested them in print. Expressing themselves mainly as members of a shared Hispanic cultural community, authors followed Spanish literary models, creating a culture that very much followed that of the metropole.Footnote 16 Especially in the capital, debates and polemics raged against the new customs and many changes in the colonial order. After the devastating earthquake of 1746, Lima had experienced a resurrection with an expanding urban topography inhabited by a fast-growing population.Footnote 17 According to a benevolent contemporary article in the periodical Mercurio Peruano, Lima was prosperous, covering an expansive area, home to many, and offering various goods and new resources, which led to prosperity and the ‘common good’ (felicidad comun) for the middle social strata: artisans, petty merchants, and small traders.Footnote 18 Concurrently, but in a far more sarcastic tone, Esteban Terralla y Landa wrote about urban social chaos in his book Lima por dentro y fuera, published on a press in Lima in 1797. His city criticism in verse targeted the inhabitants, in particular the fraudulent customs of women, who were disguised behind a tapada veil or mantle, and the city’s reconstructed architecture in danger of collapsing, which illustrated the moral downfall of the place.Footnote 19 At the centre of debate, publishing, and trade, the Peruvian capital was a cultural hub for some and a city in decay for others. Print publications served as a medium of expression to describe and judge late colonial developments and generally to communicate. While, in the middle of the twentieth century, Irving A. Leonard still called the Lima of 1583 a ‘leading centre of transplanted Spanish culture in the New World’, research has shown how after more than two hundred years of entanglement between native and European culture, objects and practices had been fully appropriated, repeatedly diversified, and unpredictably enriched.Footnote 20 In the colonial context, the printing craft and the book had been integrated into the practices of the everyday life of Peruvian cities.

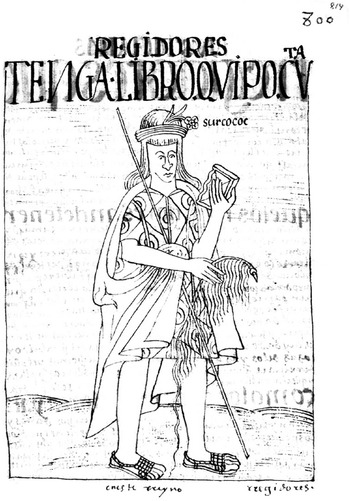

Books were only one of the various coexisting media for memory and communication, but they were the dominant one from the early years of colonial rule. Before the Spaniards brought alphabetic writing and the book, the Inca had their own system of recording information with the khipu, a knotted cord device. A drawing by Guaman Poma de Ayala depicts an administrator holding a khipu in one hand and a book in the other, representing the coexistence of the two types of media (Figure 0.1). Besides the introduction of alphabetic writing and the distribution of books, the accounting method provided by the khipu subsisted above all in rural Andean regions during the colonial time and beyond.Footnote 21

Figure 0.1 The indigenous administrator holding a khipu and a book for accounting. Regidores: tenga libro qvipo cv[en]ta, surcococ [administrator]. Guaman Poma de Ayala, El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, c. 1615, 800.

Early modern European conceptions of the book excluded Amerindian writing practices and sign carriers, such as the khipu. Renaissance philosophies followed a paradigmatic vision that writing was alphabetic, used for medieval manuscripts and printed books, and had a particular material appearance.Footnote 22 While there is a wide debate about the sophistication of pre-colonial writing systems,Footnote 23 we tend to take for granted the definition of what a book was. Today’s terminology is quite exclusive in comparison to the historical use of the word ‘book’, however. In archival inventories we often find under the heading ‘Books’ (Libros) a broad range of media, from multiple-folio volumes and editions bound in parchment, potentially handwritten, to single printed sheets and illustrated prints (estampas).Footnote 24 The many vendors of books in late colonial Lima would never have catalogued ‘popular books’ or ‘cheap prints’ separately, nor would they have sorted their stock by author name. The only sorting criteria frequently used were determined by the format and the material of the binding. By employing a historical scope and hence a comprehensive definition of the term ‘book’, this study incorporates a number of different print publications, calling them ‘printed commodities’ and ‘reading material’ with an inclusive understanding.

The book as an object together with the printing press as a tool brought profound transformations for societies, a process that has been addressed with the all-encompassing concepts of culture livresque, as studied by Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin, or ‘print culture’ as proposed by Elisabeth Eisenstein.Footnote 25 If we are to understand print culture during the Age of Enlightenment in the Viceroyalty of Peru, it is essential to study the logistics of production and the commercial contexts, as it was not the objects that were popular but their uses. From its making to its perusal among readers, in between and beyond, the book will be treated as an object with an itinerary entering different contexts. Various practices were involved in this process: writing, censoring, setting, printing, reviewing, distributing, selling, buying, reading, debating, and more, to constitute the book as ‘the negotiated and contested outcome of the interplay of material and social processes’.Footnote 26

In the viceroyalty, the printed book – either imported or of Limeño production – became a widely distributed medium. As occurred elsewhere, printing replaced in large part the practice of copying by hand. Mechanical print reproduction offered several advantages such as reproducibility, upscaling of production, and reliability, as well as the lowering of costs and the rise of prestige.Footnote 27 Contemporaries like Eusebio Llano Zapata highlighted the advantages of print over handwritten communication, as in 1769 when he stated – contrary to our conjecture – ‘printed examples will run faster than handwritten letters, which are issued with delay’.Footnote 28 Besides, printing was more durable than copying by hand. Print publications, in addition to often having a protective binding, also used another sort of ink, which was generally of a more long-lasting quality than the kind used for manuscripts.Footnote 29 Once more than a few copies of a text were required, utilising the services of a printer made sense. The author of the picaresque novel El Lazarillo de ciegos caminantes offers an insightful assessment of both reproduction mechanisms, stating that the full manuscript copy of the text was a very expensive undertaking in comparison to printing and, in addition, less faithful, as scribes were prone to introducing mistakes.Footnote 30 Despite all the advantages of mechanical reproduction, manuscripts continued to circulate in large numbers until the end of the colonial period and beyond.Footnote 31 Although the spread of printing with moveable type had revolutionised the reproduction of the written word, more than two centuries after the arrival of the technology the printing press was still only one – if an increasingly popular – method among others in Peru. In the period under consideration, the relationship between the manuscript copy and print can be described with D.F. McKenzie as complementary rather than competitive.Footnote 32

Manuscripts and printed books coexisted but took on different roles in society. Although more expensive and exclusive than print, copying by hand offered a straightforward mode of replication. Until a book was published, the text could circulate in manuscript, maintaining its own status parallel to a printed book. Especially for short and subversive texts, manuscripts continued to be used.Footnote 33 Examples that point to an intended readership reveal the different spaces and purposes of the two media. Medical recipes could be found in hand-written recetarios directed at ordinary people, offering instruction for homemade treatment, often copied from printed books.Footnote 34 In the classroom, reading a handwritten copy was one of the skills taught to students, who in the morning learned to read handwriting and in the evening read print.Footnote 35 Yet more examples of manuscript use are known from the erudite classes. Among elite circles, manuscripts met the requirements of a progressive medium of the Enlightenment and people continued to employ them for the exchange of ideas. In 1771, in the possession of the canon Bernardo de Zubieta, holder of the Quechua chair at the University of San Marcos, manuscript books on physics and handwritten letters from the mission in China were listed together with printed books.Footnote 36 Far from the printing workshops in Lima, versified dramas in Quechua circulated as manuscripts among the elites of Cuzco.Footnote 37 For the elite, scholarly, and upper classes, the printing press was not simply a technology to use; rather, it occupied an ‘ambiguous place’: letters, short literary productions, and copies of articles or book chapters were straightforwardly interchanged on loose sheets of paper, written by hand. Printing, in contrast, in the eyes of manuscript-reading scholars, allowed a broader circulation of texts, the result of which was perceived to be educational, and a tool that assisted in the enlightenment of the many.Footnote 38 Though one needs to keep in mind that books coexisted with other, much older forms of media and communication practices, the following chapters will address popular practices of print circulation.

Since many scholars’ works are premised on the assumption that the book was a luxury object limited to intellectual ventures, there is no tradition or history of printed commodities as daily objects in Peru, and very little for colonial Spanish America. The historian Alberto Flores Galindo claimed that the book was a status symbol, in the possession of an exclusive minority only. He connected this with the assumption of a restricted Enlightenment from which the majority of Peruvians were excluded.Footnote 39 Recent studies in cultural history, however, have objected to his claim by tracing the participation of ordinary people and contributing thus to a broader understanding of the Enlightenment in Peru – beyond the lettered word.Footnote 40 From European categories to the Enlightenment as a global project in different parts of the world,Footnote 41 the occurrences and developments in eighteenth-century Peru have been described as part of an Ibero-American Enlightenment. Although one could debate the existence of different ‘national’ expressions, the Enlightenment in Spanish America has been characterised as marked, above all, by adaptions and transatlantic exchanges.Footnote 42 Taken together, scholarship on the Spanish American manifestation of the Enlightenment puts emphasis on the natural sciences,Footnote 43 its Catholic character that embraced rational empiricism within a religious framework,Footnote 44 and the modernising reform programmes,Footnote 45 which materialised in imported enlightened treatises or American newspaper publications.Footnote 46 However, as will be reasserted in the Conclusion, the classical titles do not occupy a central role in scholarly narratives about the Enlightenment in Peru, and even less so the book market. A few decades ago, the book historian Robert Darnton stressed the need to pursue a more ‘down-to-earth look at the Enlightenment’.Footnote 47 Following Darnton, it is revealing to redirect attention away from the classical literary canon towards the thousands of other titles of the time, as well as the patterns of dissemination and popular practices that made them circulate widely. In the following chapters, primers called cartillas and devotional novenas, the calendar and imported manuals, will be analysed as media of practical knowledge and as the protagonists of the Peruvian book market – not in isolation, but as part and parcel of a plethora of titles, as found in the period’s book lists and inventories.

This study is based on a vast array of research into book history, transatlantic trade, and the Spanish Empire that provides a point of departure for describing the colonial book market. The history of printing in Lima can be traced back more than a century, when the bibliographer José Toribio Medina and, later, the Jesuit historian Rubén Vargas Ugarte among others laid the basis through their descriptive bibliographies with biographical sketches of print masters.Footnote 48 At the same time, the products of Spanish and European printing presses were readily accessible in colonial Peru, which underlines the imperial and market relations of the time. Research on books as trade commodities has been leading in this perspective, especially in the sea convoy system of the Carrera de Indias of the first two centuries, which encompassed New Spain as well as Peru.Footnote 49 From the fifteenth to the early nineteenth centuries, the Spanish book market extended over to the transoceanic viceroyalties, yet the nature of this relationship has not been fully understood. Virtually no research so far has studied the composite structure of the market, which included Limeño print publications and imported books, together constituting a unique variety of print offerings at the time. As pointed out by Michael F. Suarez, the question remains to be answered of how to integrate this kind of entanglement into the largely national histories of print,Footnote 50 be they Spanish, Mexican, or Peruvian. Combining these strands, A Colonial Book Market analyses the trade of books from foreign workshops, as well as of local production, hot off the press, secondhand on the market, and as a private medium of exchange – probing both the reach of print and its limitations.

To determine the many actors who participated in print culture, this monograph follows a tradition of research that one could label ‘the social history of the book’. To explore print beyond elite circles, folklorists and historians have focused on certain genres, such as pliegos de cordel in Spain, bibliothèque bleue in France, Volksbücher in Germany, and chapbooks in England.Footnote 51 While the study of so-called popular culture in the 1970s and 1980s opened up new subjects of analysis, the – justified – criticism of the distinction between high and low culture and the impossibility of ascribing genres to a certain audience have led to an ongoing debate about the concepts to use. Especially in the Romance languages, the term ‘popular print’ is often rejected on account of its exclusive association with the lower classes, not the idea of wide dissemination and appeal to a general public that it holds in English.Footnote 52 More recent publications have focused on certain genres, networks, and mechanisms of distribution, emphasising the role of protagonists such as blind sellers and street singers who performed in Spanish and Italian cities, or travelling pedlars who hawked cheap printed wares in England and the Low Countries.Footnote 53 This phenomenon existed in Lima too, but has not received much scholarly attention so far. The figure of the cajonero, who sold out of a stall or a box, as analysed in Chapter 3, could be regarded as a Spanish American counterpart. It is important to note that neither a certain genre nor the mode of sale, for instance peddling, pre-determined the customer; everyone could have read or heard a text and the pedlar, an essentially urban figure, served probably much the same clientele as a bookshop.Footnote 54 Yet we know little about the role that print played in daily life and for the many varied social groups in Lima. It is therefore important to embrace different ‘popular’ modes of acquisition as well as uses of books, in order to broadly understand the scope of the book market and the diversity of its customers. As surveys of book history in Latin America claim, even though printing production tripled in the viceroyalties at the end of colonial times,Footnote 55 and one might also add the increase in imports, ‘[v]ery few studies have focused on the social history of print in the eighteenth century and the first decades of the nineteenth century’.Footnote 56

How should we approach such a social history of reading material? By situating the study of print in the socio-historical context of late colonial Peru, the question of exclusion from or access to reading material gains major importance. Shifting the view away from volumes in the possession of renowned individuals to the many books on the marketplace is an important shift of focus to probe access possibilities and to better understand the book’s role in society. To this end, this study combines two approaches: the ‘communication circuit’ and the ‘cultural biography of things’. Regarding the first, Robert Darnton has proposed a general model that includes the different phases of the ‘life cycle’ of a book. To analyse how books came into being and trace their spread through society, the ‘communication circuit’ offers an actor-centred approach including the author or publisher, the printer (and suppliers), the shippers, the booksellers, and the readers (and binder).Footnote 57 Darnton’s concept has been criticised, reworked, and expanded by shifting the focus from groups of people to the corresponding events and practices: publishing, manufacturing, distribution, reception, and survival.Footnote 58 Books were thus studied as if they had their own ‘cultural biography’.Footnote 59 In parallel, debates in material culture studies ask how people attributed meaning to things, drawing on the publication The Social Life of Things by cultural anthropologist Arjun Appadurai. Materially produced and culturally marked as a certain category of things, books had their own cultural biographies and provoked particular uses like other things.Footnote 60 Combining these two different but congenial approaches, this monograph follows print in the form of books as ‘things-in-motion’ to ‘illuminate their human and social context’.Footnote 61

Conceptualising books as material objects is a productive way of looking at the everyday culture of the time. In line with descriptive bibliographers, and emphasising the physical character of books, size, form, and binding as well as layout and typography constituted important choices in how to publish a text, and especially the outer appearance defined the character of a book, contributing to its reception.Footnote 62 As material culture studies stress further, the materiality of objects (co-)determined their uses.Footnote 63 The importance of the weight of a folio publication in comparison to the easy dissemination of an octavo edition or, in the sources, the often-mentioned deterioration through dust – material traits characterised practices in the act of making, packing, storing, as well as reading. Mapping the sites of workshops, locations of sale, and trade routes will contribute to a deeper understanding of the reach of past print culture, popular uses, and its meaning in everyday life. This object-based research encompasses the scope and limits of circulation by following the books from the printing workshops, packed in boxes on ships and mules, to the stalls on the market and into the rooms of consumers in a colonial setting.

Time Frame and Book Structure

The late eighteenth century and the first decades of the nineteenth constituted a decisive period, marked by enlightened thinking and reform that would lead to dissolution and renewal across the Atlantic world. The many transformations also became manifest in a changing print culture. Robert Darnton has stated that ‘the late eighteenth century does seem to represent a turning-point, a time when more reading matter became available to a wider public’.Footnote 64 With regard to ‘strictly sales-oriented book production’, Reinhard Wittmann maintained that ‘[f]rom the second half of the eighteenth century onwards, the book was consistently regarded as a cultural commodity, […] the market was realigned according to capitalist principles’.Footnote 65 Rolf Engelsing claimed that during the same period a shift from intensive to extensive reading occurred, which he termed the reading revolution of Germany, stimulating an intense debate.Footnote 66 The same time frame also concludes the study of Roger Chartier, who has investigated ‘the penetration of printed works into popular culture’.Footnote 67 Do these developments of publications, the market, and reception also hold true for late colonial Peru?

To follow the developments of the last decades of colonial Peru, this investigation maintains a temporal focus on the Age of Enlightenment and starts in 1763 with a law in Spain regarding the free commerce of books without further book price fixing, which allowed for more permissive circulation.Footnote 68 This policy also held for colonial Peru, as the Spanish book market – and attendant legislation – extended to the viceroyalty. It was in 1763 that, for the first time, four different printing workshops operated simultaneously in Lima, a few years before the Jesuits, once the innovators of printing in Peru, were expelled in 1767. The time was marked by the end of the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) and the start of ambitious colonial reforms under the Bourbon King Carlos III of Spain (1759–1788), continued by his son Carlos IV (1788–1808). Changes in maritime trade likewise had an impact on the volume of book imports: the establishment of a direct sailing route via Cape Horn (1742) occurred along with the abandonment of the fleet system and the introduction of register ships. The regulations of ‘free trade’ (comercio libre) gradually liberalised the system (1765 and 1778). The establishment of the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata (today Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Bolivia) in 1776 and the increasing importance of Buenos Aires on the Atlantic coast as a transatlantic harbour, and with printing activity from 1780 on, likewise entailed political alterations on the subcontinent. Yet Lima remained an important entrepôt and the centre for the production and distribution of trade goods within Peru.Footnote 69 The largest of the rebellions in the Andes led by José Gabriel Condorcanqui, Túpac Amaru II (1780–1782), provoked the tightening of regulations and resulted in intensified scrutiny and recollection of the work of Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, as we will discuss in Chapter 1. During the Napoleonic war in Spain (1808–1814), the assembly of the Cortes de Cádiz not only passed the first liberal constitution, but also proclaimed the freedom of the press, which reached Lima in April 1811, turning previous censorship rules upside down.Footnote 70 Things changed again, however, in 1814 with the return of the absolutist regime for a few more years until in 1821 the Independence movement recorded its first success through the overthrow of the Viceroy Joaquín de Pezuela. In the following years during the wars for Independence, troops brought the hand press (imprenta volante) to other Peruvian cities, such as Arequipa (1821), Cuzco (1822), and Trujillo (1823).Footnote 71 The study closes in the early 1820s with the end of colonial times, which also put an end to Lima’s printing monopoly.

Despite intermediate turmoil, it was continuity and consolidation that marked the period under study, with a notable expansion of both the import of books and the local production of print and thus the selling and consumption of reading material, as the following chapters will show, extending in their course the sites of investigation. Expanding book production, trading, and consumption characterised this so-called Age of Enlightenment, recurrently defined by contemporary sources as a time of ilustración. While the capital Lima with its printing workshops and nearby harbour of Callao establishes the pivotal place for Chapters 1 and 2, Chapters 3–5 extend the analysis to Peruvian cities and other parts of the American continent and the Iberian Atlantic world. Following the steps of the ‘communication circuit’ and a ‘cultural biography’ of print, this monograph opens with an evaluation of the context, before turning to the production, pursuing the distribution, digging deeper into selected genres, and concluding with popular practices of acquisition and reception. Focusing on a social history of books, the modes of access and practices of participation in the colonial book market will be evaluated at every step.

It is no simple undertaking to reconstruct the everyday occurrence of printed commodities more than two hundred years ago, as printers and booksellers in Peru did not leave any account books revealing an overall picture of suppliers and customers and much-traded titles. As with other aspects of quotidian life, practices of book production, distribution, and use are elusive. In general, the experiences of ordinary people hide behind those of the elite, as they most often did not leave written accounts of their lives. Analysing the book market at large, I have studied diverse strands of sources – archival documents, bibliographical references, and books as material artefacts – from national and regional archives and libraries in Peru as well as Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Although there is no single source that clearly stated the implications of print culture, many different ones can be brought together like pieces of a puzzle to reveal an overall view of the market and, through this, an approach to study the meaning of books in late colonial Peru.

Chapter 1 presents the contexts for the making and distribution of books in Peru in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. It analyses, in particular, three limiting factors related to society, legislation, and materiality, and proves that circulation was never unfettered due to various barriers. Therefore, the chapter first addresses the topic of illiteracy. Although still only a minority could read, the period’s educational reforms promoted by contemporary theories of Enlightenment pedagogies and alternative ways of acquiring reading skills caused a moderate increase in literacy, which created new potential customers for the book market. This is illustrated by the case of popular primers (cartillas), richly documented in the archive with quarrels involving the workshop located at the Orphanage in Lima, with full name: La Casa de Niños Huérfanos de Nuestra Señora de Atocha. The chapter then focuses on legal barriers through the dual mechanism of control – peculiar to the Spanish realms – that determined the book market; however, actual practice could differ from legislation and subvert the order. The chapter finally presents an analysis of the material constraints that reveal how dependence on paper and printing types of European origin limited and restricted Peruvian print production and how printers redressed the shortcomings. Notwithstanding these confines, more people learned how to read, regulations were not always fully enforced, and materials could be reused or invented, allowing books to enter the Peruvian market in different ways and in increasing quantities.

Chapter 2 pursues a novel approach by combining the study of Lima’s printing workshops and book imports to examine the different forms of supply, which made the colonial book market a special case. The chapter argues that the book trade was a rising but risky business. Mapping the many workshops in Lima over the years, it shows that print production was continuous and the output growing. Examination of the interior of the workshop reveals much about the materiality of the craft as well as the management, calculations, and careers of printers in Peru. However, even more reading material arrived by import, as the quantitative evaluation of the number of boxes with books imported proves, including the works of several representatives of the Catholic Enlightenment. Merchants engaged in the trade with books, hoping to meet demand. Although the large majority of books came with a licence, the chapter pays attention to illegal trade, too. Hidden volumes in ships’ freight bypassed taxes and controls, while secret presses in Lima produced genres that were in high demand. By identifying and re-reading the sources used by José Toribio Medina a hundred years ago, and based on a quantitative analysis of the series of ship registers from the House of Trade (Casa de la Contratación) in Cádiz, Chapter 2 brings together our knowledge of local production and the transatlantic book trade.

Chapter 3 locates books on the market to assess questions related to access. Against notions of books as selected objects in colonial society, this chapter aims to demonstrate their presence and ordinariness in the marketplace. Through examples of merchants and traders, it first provides a synopsis of the variety of professions and bookselling ventures in the capital, before focusing on the activities of the cajonero who sold from moveable stalls in the street. Moving beyond Lima, the chapter then tracks intra-Peruvian trade patterns through the records of the custom houses. While the urban commerce of books had developed into an established business with a number of specialised booksellers in the capital, the regional trade worked quite differently, relying above all on small and individual commissions sent with muleteers into other parts of the viceroyalty. Brought together from stock inventories and official records of trials, the chapter next analyses the broad assortments of reading material in relation to the material context of selling displays in order to characterise books, whether used or new, as a ubiquitous commodity. The chapter closes by debating the prices of books, as an analysis of the economic conditions allows a more differentiated evaluation of the affordability of books.

Chapter 4 focuses on especially popular genres by analysing them in terms of production modes, materiality, and users. By this, the chapter will exemplify the breadth of the offerings. Largely neglected, small printing jobs on American affairs were key to keeping the workshops in Lima busy and had an important impact on the role of print in various spheres of urban life. The chapter exposes how a focus on popular print culture must necessarily include the dominant topic of religion, which continued to play a major role in the viceroyalty in the Age of Enlightenment. It therefore turns to the many small-format reprints of prayer booklets, novenas, before offering a reconsideration of the popularity of the almanac. The unpublished enterprise of the calendar serves as a case study to assess contemporary considerations about religious and scientific content in print. In line with hypotheses of a Catholic Enlightenment, the chapter turns from religion to practical knowledge with an analysis of manuals and how-to books, based on the import registers of ships, grouping them as a genre. In Spanish and translated into Spanish, how-to books about different subjects served for the self-instruction of a broad group of clients. Depending on their local relatedness, the titles of each genre originated either from workshops in Lima or from imports.

Chapter 5 studies the customers of the book market by looking into the modes of acquisition, the possession, and the uses of books. It proves how print permeated colonial society on a broad scale, analysing post-mortem inventories from national and regional archives. Considering additional modes of acquiring goods than just purchase, the chapter traces the circulation of books beyond the market. It then turns to the study of ownership by analysing wills, showing that books formed part of the possessions of diverse individuals, from different professions, women and men, most of them in the cities, and of all classes, some also of lesser financial means. Finally, the chapter will address the topic of book use, which took place indoors as well as outside and was led by different practices than today, characterised above all by intensive reading, particular emotions and interactions, as well as reading aloud. Such an analysis allows a more nuanced assessment of the many protagonists of different backgrounds who participated in the colonial book market and had access to the contents of print. While in Peruvian cities, as in most other parts of the world at the time, the majority of common people did not necessarily read, many knew about books, eventually possessed some, and had a measure of access to the content transmitted through them.