Introduction

The question of how racial and ethnic minorities vote is central to the study of representative democracy. Given the long history of excluding minority voices from the political process (Griffin and Flavin Reference Griffin and Flavin2011; Kroeber Reference Kroeber2018; Young Reference Young2002), improving descriptive representation – which occurs when representatives share demographic characteristics with their constituents – has substantial benefits for minority voters individually and for the health of democracy collectively. Existing studies suggest that descriptive representation increases policy responsiveness (Yeung Reference Yeung2023), contact with representatives (Gay Reference Gay2002), voter turnout (Barreto Reference Barreto2007; Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Segura and Woods2004; Griffin and Keane Reference Griffin and Keane2006), political activism (Bobo and Gilliam Reference Bobo and Gilliam1990), group consciousness (Junn and Masuoka Reference Junn and Masuoka2008), the sense of political efficacy (Merolla et al. Reference Merolla, Sellers and Fowler2013; Pantoja and Segura Reference Pantoja and Segura2003), and political knowledge (Tate Reference Tate2004).

However, as the social and psychological division between the parties grows, partisanship may overpower the relevance of shared identity (Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Mason Reference Mason2016, Reference Mason2018). Even though racial/ethnic minority voters may be conscious of and struggle with underrepresentation in a descriptive sense, they may trade off such descriptive presence for partisan representation. For example, Asian American Democratic voters may prefer non-Asian American Democratic candidates over Asian American Republican candidates.

Furthermore, group-based identities are often more complex than classic social identity theories suggest (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner and AustinWandWorchel1979). Individuals have multiple group identities that interact with each other (Roccas and Brewer Reference Roccas and Brewer2002). We do not clearly understand which of these identities for voters become salient and relevant in political decision making (Dovi Reference Dovi2002). In particular, it is unclear how some groups make choices when facing trade-offs where they must choose among these identities in elections.

When such identities conflict, do voters want representatives who share their race, ethnicity, or partisanship? How do they vote when candidates share one of these identities but not another? The phenomenon of constituents voting for co-racial (and co-partisan) representatives has long been studied in the context of African Americans and, to a somewhat lesser extent, Hispanic Americans (see, for example, Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Segura and Woods2004; Bobo and Gilliam Reference Bobo and Gilliam1990; Judis and Teixeira Reference Judis and Teixeira2004; Tate Reference Tate2004). Less is understood about Asian Americans, although they are the fastest growing racial/ethnic group in the United States (Budiman and Ruiz Reference Budiman and Ruiz2021a).

Asian Americans’ experiences highlight the blurred lines between in- and out-group constructions, as well as the sometimes weak connections between race/ethnicity and political affiliations (Leonhardt Reference Leonhardt2023; Pew Research Center 2018). This ambiguity arises because ‘Asian American’ is a pan-ethnic identity – a racial category based on consolidating different ethnic groups from varying cultures and national origins (Okamoto Reference Okamoto2014).Footnote 1 Because of their weak or varied partisan ties, Asian Americans can face a unique trade-off between descriptive (that is, Asian American) and partisan representation. At the same time, because of the strength of their ethnic identity, they may also face trade-offs involving ‘co-ethnic’ (for example, Korean for Korean) and ‘cross-ethnic’ (for example, Indian for Korean) descriptive representation.

To untangle such complicated preferences, we conduct two studies. First, we measure Asian American preferences for collective representation in Congress, which is the extent to which the legislative body as a whole represents its constituents. Second, we investigate the preferences for dyadic representation in a competitive election setting using a conjoint experiment, in which survey respondents are asked to choose one of two hypothetical candidates.

We find that when Asian Americans are asked about who they want in the legislature collectively, they favor descriptive over partisan representation. They report that they would prefer more Asian Americans overall in Congress rather than more representatives who share their partisan affiliation. In contrast, when presented with such trade-offs between two candidates, Asian Americans generally prefer partisan representation over descriptive representation. Descriptive representation is only prioritized when a black or Hispanic co-partisan candidate is on the ballot, although we later find that this effect may not be driven by animus against non-white candidates. For example, Korean American Democratic voters prefer a Korean American Republican candidate over a black Democratic candidate. Asian Americans are willing to cross party lines to vote for a co-ethnic candidate, but this never occurs for a cross- or pan-ethnic candidate (for example, Korean American Democratic voters choosing a Japanese American Republican candidate or an ‘Asian American’ Republican candidate).

These findings contribute to the broader literature on the political preferences and voting behavior of racial/ethnic minorities. Specifically, we shed light on the importance of considering heterogeneity within ‘in-groups’ to improve our general understanding of descriptive representation. Like other groups, Asian Americans are not monolithic, and they feel competition not only against non-Asian Americans but also among Asian Americans, especially when partisanship is also considered.

Preferences for Representation

Representation can take many forms. Substantive representation, the extent to which elected officials advocate on behalf of constituents (see, for example, Sabl Reference Sabl2015), is often discussed in the context of party politics. Both demographic characteristics like race and partisanship can bring substantive benefits to constituents (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999). We focus on descriptive and partisan representation, as well as how constituents may have preferences for each in a collective or dyadic setting.

Descriptive Representation

Descriptive representation occurs when there are shared characteristics between legislators and constituents (Pitkin Reference Pitkin1972). Although many characteristics may qualify as a ‘shared identity’ between legislators and constituents, the most commonly studied revolve around salient identities, such as gender, class, and race/ethnicity. Descriptive representation may have symbolic benefits for constituents, cultivating greater political trust and efficacy for voters who have a shared identity with their legislator (Sanchez and Morin Reference Sanchez and Morin2011). It can also result in substantive benefits through better communication and greater insights into the interests of marginalized groups (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Pitkin Reference Pitkin1972). Descriptive representatives may more readily advocate for the interests of their constituents in the policy-making process (Lowande et al. Reference Lowande, Ritchie and Lauterbach2019).

There is less research on what factors drive voters’ demand for descriptive representation. Some scholars find that the desire for descriptive representation is influenced by constituents’ feelings of linked fate or perceptions of discrimination (Manzano and Sanchez Reference Manzano and Sanchez2010; Schildkraut Reference Schildkraut2013; Wallace Reference Wallace2014).Footnote 2 As a group severely underrepresented in government and historically marginalized, Asian Americans, ceteris paribus, prefer candidates who share their co-ethnic (Sadhwani Reference Sadhwani2022b) or pan-ethnic identity (Lublin and Wright Reference Lublin and Wright2023). This effect of race/ethnicity on Asian Americans’ vote choice is mediated by the strength of their racial/ethnic identity (Schildkraut Reference Schildkraut2013).

Partisan Representation

Partisan representation can refer to several different ways that partisanship influences the representational relationship, including collective party presence and overall party control (Hurley Reference Hurley1989), concerns about policy responsiveness of the parties (Kastellec et al. Reference Kastellec, Lax, Malecki and Phillips2015), or how members of different parties represent constituents (Bartels Reference Bartels2016; Rhodes and Schaffner Reference Rhodes and Schaffner2017). Voters typically want their party to control the government to advance its platform, which reflects their ideological and issue preferences. As a result, partisan representation is often framed around policy competition. However, as partisanship becomes both expressive and instrumental (Huddy et al. Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015; Maxwell et al. Reference Maxwell, Pérez and Zonszein2023), a candidate’s party affiliation itself can independently influence voters’ preferences beyond the candidate’s policy positions (for example, Stokes Reference Stokes1963).

Regarding voters’ demand for partisan representation, a growing literature on affective polarization is instructive (see Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019 for a review of earlier studies). Partisanship has become an ever-increasingly important part of American voters’ social identities, rising in prominence compared to, and intertwining with, other social identities (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Mason and Wronski Reference Mason and Wronski2018). Therefore, whether voters seek substantive policy benefits or symbolic feelings of representation (Ruckelshaus Reference Ruckelshaus2022), partisan identity is often the strongest predictor of vote choice.

It is unclear whether and how these trends have influenced Asian Americans specifically. Asian Americans tend to have weaker partisan identities, and they are more likely to identify as independents (Hajnal and Lee Reference Hajnal and Lee2011; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Ramakrishnan, Lee and Wong Junn2011). While they tend to be more economically well-off, some scholars have noted that socio-economic status does not seem to have a significant effect in shaping partisan identification for Asian Americans (Zheng Reference Zheng2019).

Trade-Offs Between Descriptive and Partisan Representation

Of course, individuals often possess multiple group identities that interact with one another. While existing research investigates how descriptive or partisan representation often operates independently, we shed light on how they work interdependently, specifically in situations where they conflict with each other. We examine Asian American voters’ preferences when facing a trade-off between their preference for partisan and co- or pan-ethnic descriptive representation.

There are two situations in which such trade-off situations would not exist. First, voters’ multiple group identities do not introduce conflicts when partisan and descriptive characteristics align. For example, an Asian American Democrat (Republican) can vote for an Asian American Democratic (Republican) candidate as opposed to a white Republican (Democratic) candidate without any conflict. Second, and more importantly, even when candidates present cross-cutting identities along the lines of race/ethnicity and partisanship, if voters choose solely or even primarily based on partisanship or descriptive attributes, vote decisions also do not present difficult trade-offs. In practice, voters do often need to make complex decisions between multiple social identities (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Brewer and Arbuckle2009; Roccas and Brewer Reference Roccas and Brewer2002) and such trade-offs are not uncommon in the real world (see, for example, Hayes and Hibbing Reference Hayes and Hibbing2017; White et al. Reference White, Laird and Allen2014). These decisions are increasingly relevant as the parties become more racially and ethnically diverse.Footnote 3

Nevertheless, little empirical research specifically examines such trade-offs between descriptive and partisan representation. Some studies show that black and Latino voters generally prioritize representatives’ party identification or ideology over race/ethnicity (Ansolabehere and Fraga Reference Ansolabehere and Fraga2016; Casellas and Wallace Reference Casellas and Wallace2015; Velez Reference Velez2023). Cuevas-Molina and Nteta (Reference Cuevas-Molina and Nteta2023) investigate Latino voting behavior for a hypothetical representative who is aligned on ethnic and/or partisan characteristics, finding that Latino voters are willing to vote for co-ethnic candidates even when they belong to the opposite party. Regarding trade-off situations for Asian Americans, the existing literature is more limited and focuses on specific elections in California (see, for example, Leung Reference Leung2022; Sadhwani Reference Sadhwani2022b).

Collective and Dyadic Representation

Another key dimension is the distinction between collective and dyadic representation (Weissberg Reference Weissberg1978). Collective representation refers to the extent to which a legislative body represents its constituents (for example, the presence of Asian Americans in Congress as a whole). Dyadic representation refers to the one-to-one relationship between a representative and an individual constituent (for example, whether an Asian American voter has an Asian American member of Congress).

Casellas and Wallace (Reference Casellas and Wallace2015) examine Latinos’ views of descriptive representation at both the collective and dyadic level. They find that descriptive representation at both levels is less critical for Latino Republican respondents than Latino Democratic respondents. Given that racial minorities are typically perceived to be Democrats, Casellas and Wallace (Reference Casellas and Wallace2015)’s finding may suggest that those who have cross-cutting identities (that is, Latino Republicans) are hesitant to trade off partisan representation for descriptive representation. The same may be true for Asian Americans with cross-cutting identities, as they might infer partisanship from race/ethnicity in the same way.

It is also unclear whether the preference for partisanship over race/ethnicity is observed at the collective or dyadic level. It is possible that, symbolically, individuals may value a more diverse and representative legislature at the collective level. But when it comes to dyadic representation – where personal issue alignment and accountability are more salient – partisan identity may take precedence.

The Case of Asian Americans

Amid the ‘blue wave’ in 2018, Gil Cisneros, a Hispanic Democrat, narrowly defeated Young Kim, a Korean American Republican, in the CA-39 district. Kim won the rematch against the incumbent Cisneros two years later by just over 4,000 votes. Despite the challenge of running against an incumbent in a district that ultimately favored Biden by over ten points, Kim managed to swing the district back in her favor (Godwin Reference Godwin, Foreman, Godwin and Wilson2022). This victory was made possible in part by many Korean Americans splitting their ticket – voting for Kim, a Republican, for the House while voting for Democrats for other seats (Leung Reference Leung2022; Staggs et al. Reference Staggs, Wheeler and Robinson2020).Footnote 4

The election between Kim and Cisneros is an illustrative example of Asian American voters being cross-pressured. Although Asian Americans are currently the most politically underrepresented group in the United States, they now make up a substantial minority in this country and are the fastest-growing racial group, projected to surpass 46 million by 2060 (Budiman and Ruiz Reference Budiman and Ruiz2021a).Footnote 5 Because around 60 per cent are foreign-born immigrants, many remain ineligible to vote (Budiman and Ruiz Reference Budiman and Ruiz2021a). However, over time, increasing rates of naturalization have expanded the Asian American electorate. In 2020, 57 per cent of Asian Americans were eligible to vote, but this figure has grown steadily, with the share of eligible voters nearly doubling between 2000 and 2020 (Budiman Reference Budiman2020). Their votes are now increasingly influential, particularly in some swing states where Asian Americans have become more common, including Georgia, Nevada, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Texas (Budiman Reference Budiman2020; Sadhwani Reference Sadhwani2022a).

There are several other reasons why examining Asian American voting behavior is essential for the study of partisan and descriptive trade-offs. First, partisanship is not as crystallized for this group compared to others. Like other ethnic minority groups in the United States, Asian Americans in the twenty-first century have tended to vote for Democrats (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Nguy and Masuoka2024; Masuoka et al. Reference Masuoka, Han, Leung and Zheng2018), but recent elections suggest that such an alignment is loosening (Balz Reference Balz2022; Zarsadiaz Reference Zarsadiaz2024). Asian Americans increasingly identify as independent and have weaker attachments to political parties than other minority groups (Hajnal and Lee Reference Hajnal and Lee2011; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Ramakrishnan, Lee and Wong Junn2011). One reason for this weak partisan attachment may be the limited outreach from local party organizations and campaigns (Wong Reference Wong2008). Because most Asian American voters are first- or second-generation immigrants, their partisan identities do not follow the traditional path of parental socialization, but rather through peer socialization or experiences of social exclusion (see, for example, Kuo et al. Reference Kuo, Malhotra and Mo2017; Raychaudhuri Reference Raychaudhuri2018).

Asian Americans’ ideological views and demographic characteristics (that is, high socio-economic status and religiosity) provide opportunities for the Republican Party to make inroads (Hajnal and Lee Reference Hajnal and Lee2011; Raychaudhuri Reference Raychaudhuri2018). Recent work also suggests that for Democratic voters, having a representative who shares their racial or ethnic identity can make them more accepting of ideological differences (Weissman Reference Weissman2024). In other words, identity congruence may allow representatives to deviate more from the party line without losing support.

Second, studying desires for descriptive representation among pan-ethnic groups also sheds light on how voters consider trade-offs more generally (see, for example, Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Crabtree and Horiuchi2023; Junn and Masuoka Reference Junn and Masuoka2008; Wu Reference Wu2022). Unlike a co-ethnic representative, a cross-ethnic representative (for example, Indian for Korean) may have no shared background, culture, language, or phenotypical features, which may make them less desirable as a true descriptive representative (Cuevas-Molina and Nteta Reference Cuevas-Molina and Nteta2023; Lu Reference Lu2020). ‘Asian American’ identity may have developed as a strategic response to exclusion from state recognition and resources, as combining smaller ethnic groups into a broader racial category enabled more effective political mobilization and advocacy (Espiritu Reference Espiritu1992). Indeed, Asian Americans are more likely to associate with their co-ethnic rather than their pan-ethnic identities (Lien et al. Reference Lien, Conway and Wong2003; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Ramakrishnan, Lee and Wong Junn2011).

A clear pattern in the literature is the context-specific relevance of identities for Asian Americans. Recent qualitative research has highlighted the complexities of Asian American identity, particularly regarding ethnic origin and pan-ethnic representation. Using semi-structured interviews, Yeung (Reference Yeung2024) finds that many resist pan-ethnic identification, viewing it as inadequate to represent their diverse cultural experiences. Yet Asian Americans do prioritize and embrace their pan-ethnicity during more collective experiences (Yeung Reference Yeung2024). Other work shows that definitions and stereotypes regarding ‘Asian Americans’ vary based on the background of who is being asked (Goh and McCue Reference Goh and McCue2021; Lee and Ramakrishnan Reference Lee and Ramakrishnan2019).

Descriptive preferences also vary with the local or community context. Asian Americans place greater value on pan-ethnic representation in areas with low co-ethnic density, where a shared pan-ethnic identity is more salient or politically useful (Wu Reference Wu2025). In areas with a high concentration of co-ethnic individuals, social dynamics such as peer influence or stronger community mobilization may also shape support (Fraga Reference Fraga2016; White and Laird Reference White and Laird2020). Preferences may still vary depending on whether the candidate is co-ethnic (from the same Asian-origin ethnic group), cross-ethnic (from a separate Asian-origin ethnic group), or pan-ethnic (Asian American generally), particularly in competitive electoral contexts where partisan identity is also salient.

Indeed, Asian Americans are more likely to vote for co-ethnics who share their national origin (Sadhwani Reference Sadhwani2022b; Uhlaner and Le Reference Uhlaner and Le2017). However, regarding trade-off situations for Asian Americans, the existing literature is limited and focuses on specific elections in California (see, for example, Leung Reference Leung2022; Sadhwani Reference Sadhwani2022b). In these elections involving trade-offs, Asian Americans are more likely to vote for co-ethnic candidates but not for pan-ethnic candidates. While these studies provide initial insights, whether these patterns generalize to other electoral contexts is unanswered.

Hypothesis 1 (Partisan v. Descriptive): Asian Americans prefer partisan representation over descriptive representation, on average.

Hypothesis 2 (Pan-ethnicity v. Co-ethnicity): Asian Americans prefer co-ethnic candidates over pan-ethnic candidates and are more willing to trade off partisan representation for co-ethnic candidates than pan-ethnic candidates.

Drawing on these existing studies about Asian American voters, we expect that the type of descriptive representation – whether a representative is co-ethnic or pan-ethnic – affects voters’ preferences when they face a trade-off between descriptive and partisan representation. Specifically, Asian Americans are more likely to prioritize co-ethnicity, compared to pan-ethnicity, when race/ethnicity and partisanship conflict.Footnote 6 This pattern is perhaps more relevant in dyadic representation, but we do not have a strong expectation that it is exclusive to dyadic settings instead of collective ones.

Study Designs

To examine how Asian Americans evaluate descriptive and partisan representation, we conduct two separate pre-registered studies from an original survey fielded on Asian Americans.Footnote 7 The first study examines Asian Americans’ preferences for shared representation in Congress and collective presence in the legislature. The second study examines preferences for dyadic representation in a competitive election setting.

We fielded our survey from 26 February to 21 March 2022, using Lucid Marketplace, which tracks well with other sampling platforms and national benchmarks (Coppock and McClellan Reference Coppock and McClellan2019). The sample consists of respondents who identified as Asian or Asian American only. The total number of respondents is 2,362, excluding observations that Qualtrics flagged as potential bots. We collected our sample to reflect the nationwide distribution of ethnic groups, with 23 per cent Chinese American (excluding Taiwanese Americans), 20 per cent Indian American, 19 per cent Filipino American, 10 per cent Vietnamese American, 8 per cent Korean American, 7 per cent Japanese American, and 13 per cent all other Asian ethnic groups in the United States (Budiman and Ruiz Reference Budiman and Ruiz2021b). Our sample consists of 65 per cent Democrats and 35 per cent Republicans, including leaners. This partisan distribution is similar to recent estimates of Asian American partisan preferences, with 62 per cent identifying as Democrats and 34 per cent as Republicans, including leaners (Schaeffer Reference Schaeffer2023). We exclude true independents from our analysis since we are interested in trade-offs for partisans (Keith et al. Reference Keith, Magleby, Nelson, Orr, Westlye and Wolfinger1986).

Study 1: Preferences for Collective Representation

For Study 1, we designed survey questions to measure how Asian Americans prefer partisan and/or descriptive representation when asked outright about the makeup of Congress. These questions are modeled after the 2016 National Asian American Survey, or NAAS (Ramakrishnan et al. Reference Ramakrishnan, Lee and Wong Lee2018). Respondents were asked to indicate their agreement with five different statements in the following format: ‘We need more [type of representatives] in Congress’ (on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘Strongly Agree’ to ‘Strongly Disagree’). We split questions into ‘low’ and ‘high’ information categories because the presence of ethnic and/or partisan information may change how voters weigh these factors (Crowder-Meyer et al. Reference Crowder-Meyer, Gadarian and Trounstine2020; Kirkland and Coppock Reference Kirkland and Coppock2018). Low-information questions independently ask respondents preferences for race/ethnicity and partisanship, while high-information questions give information about both race/ethnicity and party. While the NAAS survey only includes the low-information items, we modify their questions to understand preferences for both descriptive and partisan representation when intertwined.

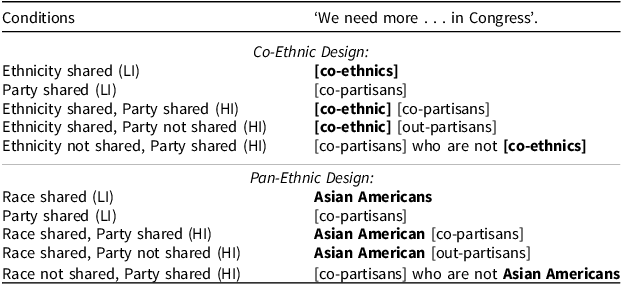

Respondents were randomly split across two research designs: Co-Ethnic Design and Pan-Ethnic Design (Table 1). In the Co-Ethnic Design, we asked questions about co-ethnicity (such as, ‘We need more Japanese Americans in Congress’ for Japanese American respondents). In the Pan-Ethnic Design, we asked questions about pan-ethnicity (such as, ‘We need more Asian Americans in Congress’). In both designs, the partisan questions are the same (such as, ‘We need more Republicans in Congress’). The ‘high-information’ questions include statements about both race and partisanship (such as, ‘We need more Asian American Democrats in Congress’). Each respondent indicated agreement with five items about shared presence in Congress: (1) Race or ethnicity shared, (2) Party shared, (3) Race or ethnicity shared and Party shared, (4) Race or ethnicity shared and Party not shared, (5) Race or ethnicity not shared and Party shared. The questions are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Study 1 survey design

Note: respondents would fill in the information in the brackets that correspond to their own racial and ethnic identity. (LI) refers to low information, (HI) refers to high information. The key differences between the two designs are highlighted in bold. The ‘co-ethnics’ include Chinese American, Indian American, Filipino American, Vietnamese American, Korean American, and Japanese American.

The last two rows of Table 1 in each design indicate trade-offs. Under the Co-Ethnic Design, they involve out-partisan but co-ethnic representatives (for example, more Chinese American Republicans in Congress for a Chinese American who is a Democrat) and co-partisan but not co-ethnic representatives (for example, more Democrats who are not Chinese Americans in Congress for a Chinese American who is a Democrat). Under the Pan-Ethnic Design, the questions are similar except with ‘Asian American’ rather than ‘Chinese American’, for example.

Study 2: Preferences for Dyadic Representation

In Study 2, we study Asian Americans’ choices in electoral settings, particularly when they face trade-off situations. While some scholars examine how voters react to cross-pressures in actual elections (Graves and Lee Reference Graves and Lee2000; Michelson Reference Michelson2005), using actual election data is often insufficient to understand these relationships more broadly. The presence of Asian American Republican candidates, while increasing, is still a relatively new phenomenon (Lublin and Wright Reference Lublin and Wright2023). To gain a more coherent understanding of how Asian Americans make vote choices with cross-pressures, we use an experiment to randomly manipulate multiple characteristics of hypothetical candidates.

Conjoint analysis is a valid experimental method to understand such multidimensional preferences underlying these choices (Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). In a conjoint experiment, respondents rate or choose from a set of hypothetical profiles that vary on a set of attributes of interest selected by researchers. This approach is advantageous for us to study trade-off preferences between two different candidates while averaging over various combinations of other attributes.

Outcome questions

After being shown two hypothetical candidates side-by-side, respondents were asked, ‘Consider the following two hypothetical candidates for Congress. Which candidate are you most likely to vote for? Even if you are not entirely sure, please indicate which of the two you would be more likely to prefer’.Footnote 8 This task was repeated ten more times for eleven total tasks, with the last task being the same as the first task. This repeated question is used to measure the intra-respondent reliability (IRR), which is helpful to accurately measure marginal means after correcting measurement-error-induced biases (Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Horiuchi, Kaufman, King, Komisarchik, Ebanks, Katz, King, Evans, King and Evans2023).

Candidate attributes

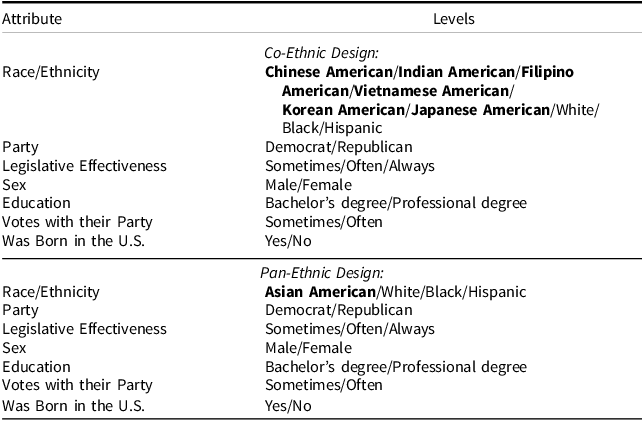

Each candidate has seven attributes. Each attribute has multiple levels, one of which is randomly assigned to each hypothetical candidate (see Table 2). Each level had an equal chance of appearing, except for the race/ethnicity (for over-sampling purposes) and education, to maintain external validity (see de la Cuesta et al. Reference de la Cuesta, Egami and Imai2022).Footnote 9 The main attributes of our interest are Race/Ethnicity and Party. Other attributes include Advances Favorable Legislation for District Constituents, Sex, Education, Votes with Party, and Was Born in the United States. We conducted a pre-test (n= 1,042) to validate attributes that are perceived to be associated with Asian American candidates and, thus, should be included in our conjoint design (see Appendix B for details). The order of attributes was randomized across respondents but fixed within respondents.

Table 2. Study 2 survey design

Note: in the experiments, the exact label for Legislative Effectiveness is ‘Advances Favorable Legislation for District Constituents’. We shorten it here for the presentation. The key differences between the two designs are highlighted in bold. See Figure A.1 for a visual example of the conjoint task.

Similarly to Study 1, respondents were split into two design conditions: Co-Ethnic Design and Pan-Ethnic Design. In the Co-Ethnic Design, for Race/Ethnicity, in addition to ‘white’, ‘black’, and ‘Hispanic’, there were six other levels corresponding to Asian Americans’ varying countries of origin: ‘Chinese American’, ‘Indian American’, ‘Filipino American’, ‘Vietnamese American’, ‘Korean American’, and ‘Japanese American’. These six ethnic groups compose around 87 per cent of Asians in the United States. In the Pan-Ethnic Design, the possible levels were ‘Asian American’, ‘white’, ‘black’, and ‘Hispanic’.

A combination of these designs allows us to test how three different types of descriptive representation affect Asian Americans’ vote choice: co-ethnic (from the same Asian country of origin), cross-ethnic (from a different Asian country of origin), and pan-ethnic (Asian American, no country of origin specified).

Measures of social identities

Respondents were also asked questions about their partisan and ethnic identities. First, we use Huddy et al. (Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015)’s four-item measure of partisan identity for respondents who affiliate with or lean towards one of the two major parties. Second, we asked three sets of four-item questions measuring the strength of their co-ethnic, pan-ethnic, or partisan identity (see Figure A.4 for baseline results). Specifically, we adapt Huddy et al. (Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015)’s partisan identity items to measure the strength of racial and ethnic identity. For example, for one of the partisan identity items, we asked respondents to answer: ‘To what extent do you think of yourself as being a [Democrat/Republican]?’ on a four-point scale. A corresponding question to measure co-ethnic identity is: ‘To what extent do you think of yourself as being a [Chinese/Indian/Filipino/Vietnamese/Korean/Japanese] American?” Similarly, a question to measure pan-ethnic identity is: ‘To what extent do you think of yourself as being an Asian American?”

Statistical methods

We report some deviations from our pre-registration. First, we exclude ‘ties’ (both profiles having the same level [for example, ‘black’] for the attribute of interest [for example, Race/Ethnicity]) in calculating marginal means. We pre-registered that we would measure a profile-level marginal mean (Leeper et al. Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020) for each attribute level. This profile-level marginal mean measures the probability of choosing a profile that includes the level of interest (for example, ‘Asian American’) for the attribute of interest (for example, Race/Ethnicity) averaged over (1) all the levels for this attribute (including the level of interest) in another profile, (2) all possible combinations of other attributes in both profiles, and (3) all respondents. However, since pre-registration, some studies have shown that including profile pairs with these ‘ties’ biases the marginal means by attenuating the estimates towards 0.5 for binary choices (Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Horiuchi, Kaufman, King, Komisarchik, Ebanks, Katz, King, Evans, King and Evans2023; Ganter Reference Ganter2023).

Second, we measure marginal means corrected for possible measurement-error-induced bias (Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Horiuchi, Kaufman, King, Komisarchik, Ebanks, Katz, King, Evans, King and Evans2023). Respondents’ attention to every detail in a conjoint table may be limited. A new method proposed by Clayton et al. (Reference Clayton, Horiuchi, Kaufman, King, Komisarchik, Ebanks, Katz, King, Evans, King and Evans2023) addresses this concern and improves the accuracy of estimates by using the IRR we measure in our survey.

Third, we calculate choice-level, rather than profile-level, marginal means (Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Horiuchi, Kaufman, King, Komisarchik, Ebanks, Katz, King, Evans, King and Evans2023). We are specifically interested in how respondents make choices when they encounter trade-offs (for example, whether a Korean Democrat prefers a Korean Republican candidate or a Latino Democratic candidate, as in CA-39). For this purpose, it is more straightforward and informative to treat each (binary) choice as the unit of analysis. The standard method of analyzing conjoint data (Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014; Leeper et al. Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020) treats each profile as an independent observation and, thus, ignores the comparison between the two profiles.

Results

We first present the results of measuring Asian Americans’ preferences for collective representation. We then present the results of our conjoint analysis, focusing on the study of trade-offs for dyadic representation.

Study 1: Preferences for Shared Representation in Congress

Figure 1 shows the results of examining our collective representation questions. Each point corresponds to the mean agreement for each version of the question about respondents’ preferences for collective representation. The horizontal lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals. The results of subgroup comparisons are presented in Appendix A.2.Footnote 10

Figure 1. Mean response to more collective representation Note: we measure whether a respondent agrees or disagrees with the statement, ‘We need more . . . in Congress’, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The responses are treated as continuous. The horizontal lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Low-information questions (race/ethnicity or party)

The first two rows in each panel correspond to the average responses in low-information settings, where only one piece of information is given, either party (‘Own-party members’) or race/ethnicity (‘Co-ethnic Asian Americans’ or ‘Pan-ethnic Asian Americans’). There are no clear differences between the desire for more descriptive or partisan representation. The average agreement for partisan representation is 4.22 or 4.21 in the Co-Ethnic Design and the Pan-Ethnic Design, respectively. The average agreement for descriptive representation is 4.20 or 4.24, which also do not contain meaningful differences.Footnote 11

Overall, respondents have moderate to strong agreement that there should be more legislators in Congress who share their party or their race/ethnicity. One possible interpretation is that voters genuinely prefer to have more own-party and co-ethnic members of Congress without having stronger weights on one over another. However, because responses are clustered around this upper limit, another possibility is that this common way of measuring voters’ preference for collective representation results in a ceiling effect, making it difficult to distinguish between genuine preferences between party and race/ethnicity.

High-information questions (race/ethnicity and party)

Additional information that implies a trade-off may change preferences for collective representation. We first look at the average agreement when respondents are given another piece of information that aligns with their partisan and ethnic/racial identity (third row): ‘Co-ethnic Asian American and Own-party members’ or ‘Pan-ethnic Asian American and Own-Party members’. To repeat, Asian Americans agreed with having more co-ethnic legislators in Congress (second row; without information about partisanship) on average at 4.20. This agreement for more co-ethnic Asian Americans who share their partisan affiliation does not increase substantially: it is almost the same (4.21). The pattern is the same when asking about pan-ethnics, namely, only a slight increase from 4.24 to 4.26.

There are, again, two possible interpretations of these results. The first is, once again, a potential ceiling effect. That said, the lack of further increase in agreement may suggest that respondents consider both ethnicity/race and party even when asked about only one or the other. Specifically, when respondents are asked about their preference regarding race/ethnicity (for example, ‘more Asian Americans’) in the hypothetical legislature, they may assume the party as well (for example, ‘more Democrats’ for Democratic supporters).Footnote 12 As minority candidates are typically perceived to be more liberal (McDermott Reference McDermott1998; Sigelman et al. Reference Sigelman, Sigelman, Walkosz and Nitz1995), Republican respondents may assume that these candidates are less likely to be their own party members.

Trade-offs and strength of identity

The last two high-information items in Figure 1 show how respondents feel about trade-off situations – the increased presence of legislators who share their race/ethnicity but not their party (fourth row in both panels) and the increased presence of legislators who share their party but not their race/ethnicity (last row in both panels). Respondents seem to view shared race/ethnicity as more important than shared partisanship when considering trade-offs for collective representation in Congress. For example, the agreement about the need for more legislators who are co-ethnics but of the opposite party drops to 3.29 points. When legislators are not co-ethnics but of the same party, agreement drops even further to 2.98 points. The pattern for pan-ethnic out-partisans (asking about needing more Asian Americans, but not a shared co-partisan, in Congress) and out-ethnic co-partisans (asking about needing more co-partisans, but not Asian Americans) is nearly identical.

Overall, respondents are least likely to trade descriptive representation for partisan representation; the lowest agreement was for supporting more co-partisans in Congress who are explicitly not of their shared race/ethnicity (trading off descriptive for partisan representation).

One explanation for the preference for trading off partisan representation for descriptive representation is that respondents generally have stronger pan-ethnic and co-ethnic social identities than partisan social identities. To examine this potential mechanism, we measure the heterogeneity in the mean agreement by respondents’ strength in racial, ethnic, and partisan identities. We identify a respondent with a ‘strong’ social identity as one with a score in the top tercile, while ‘medium’ and ‘weak’ social identities correspond to the middle and bottom terciles.

Figure A.5 Questionmark in the Appendix shows that those with a strong co-ethnic or pan-ethnic identity are more likely to agree that Congress needs more representatives who share their race/ethnicity than representatives who share their partisanship. Specifically, the difference between ‘Co-ethnic [or Pan-ethnic] Asian American but Opposite-party members’ (fourth row) and ‘Not co-ethnic [or Pan-ethnic] Asian American but Own-party members’ (fifth row) is the largest among respondents with a strong racial/ethnic identity (in blue), while it is the smallest among respondents with a weak racial/ethnic identity (in black).

We do not observe a similar pattern of heterogeneity in respondents’ strength of partisan identity. Although we see differences by the strength of co-ethnic or pan-ethnic identity (Figure A.5), the differences are small and insignificant by the strength of partisan identity (Figure A.6). On the other hand, respondents with weak partisan identity are even more likely to trade off partisan representation for co-ethnic or pan-ethnic descriptive representation. These results highlight just how much Asian Americans are not willing to sacrifice collective racial/ethnic descriptive representation for the sake of partisan representation.

Study 2: Preferences for Candidates with Shared Characteristics

Study 1 suggests respondents prefer descriptive representation along ethnic/racial lines over partisan representation when the questions are about collective representation. However, their preferences can differ when asked about dyadic representation for two reasons. First, in a competitive election, feelings of group threat are more likely to be activated (Huddy et al. Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015). Second, the findings from Study 1 may be partly due to the direct questioning about partisanship and race/ethnicity. Respondents may feel that they are expected to report their preferences for more co-ethnic or pan-ethnic legislators because there are so few Asian Americans in Congress overall.

While directly asking about collective representation is a first step in understanding how Asian Americans weigh partisanship and race/ethnicity, we need to measure voters’ honest preferences when they make more explicit trade-off decisions between two candidates. The conjoint design of Study 2 is suitable for this purpose because we present difficult-to-choose trade-off options to respondents and ask them which one they would prefer. Conjoints are also known to mitigate social desirability bias (Horiuchi et al. Reference Horiuchi, Markovich and Yamamoto2022), which is a possible concern in Study 1.

Marginal means

First, we calculate the marginal mean of each attribute of interest – Party or Race/Ethnicity – before we examine specific trade-off behavior. As explained earlier, we measure choice-level marginal means (with bias-correction) proposed by Clayton et al. (Reference Clayton, Horiuchi, Kaufman, King, Komisarchik, Ebanks, Katz, King, Evans, King and Evans2023). The unit of analysis is a profile pair. Therefore, the marginal mean of choosing an ‘Own-party candidate’ is the same as the complement of the probability of choosing an ‘Out-party candidate’ (that is, excluding the cases where two profiles have the same levels). This quantity of interest averages over the combinations of all other attributes. What is an ‘own-party’ is defined by each respondent’s partisanship and the party of a hypothetical candidate presented in Table 2. For the Race/Ethnicity attribute, to measure the marginal means for the levels relevant to Asian Americans, we focus on profile pairs for which one profile contains the level of interest. They include (1) ‘Co-ethnic [for example, Korean for Korean] Asian American candidate’, (2) ‘Cross-ethnic [for example, Indian for Korean] Asian American candidate’ in the Co-Ethnic Design, or (3) ‘Pan-ethnic [non-specific] Asian American candidate’ in the Pan-Ethnic Design. In each pair, the other profile should contain either ‘white’, ‘black’, or ‘Hispanic’. This means that we intentionally exclude pairs with the same level, such as black versus black or Asian American versus Asian American (for example, Korean American versus Indian American) pairs.Footnote 13

The estimated results are presented in Figure 2. We find some notable patterns. First, partisanship is the most critical factor in choosing candidates in a competitive electoral setting. The marginal mean of choosing ‘Own-party candidate’ is 0.89 in the Co-Ethnic Design and 0.91 in the Pan-Ethnic Design. Therefore, if one of the two candidates in an election shares the same party as a respondent, the respondent will vote for that candidate with approximately 90 per cent probability.

Figure 2. Marginal means on binary vote choice (main attributes) Note: the horizontal lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals. The comparison level is ‘Out-party candidate’ for the marginal mean of choosing ‘Own-party candidate’ and either ‘white’, ‘black’, or ‘Hispanic’ for the marginal mean of choosing a co-ethnic, cross-ethnic, or pan-ethnic Asian American candidate.

Second, respondents do not favor shared partisanship and race/ethnicity equally. The marginal means for ‘Co-ethnic Asian American candidate’, ‘Cross-ethnic Asian American candidate’, and ‘Pan-ethnic Asian American candidate’ are substantially smaller than the marginal mean for ‘Own-party candidate’. This finding in Study 2 differs from the finding in Study 1, which suggested that respondents do not distinguish between descriptive or partisan collective representation.

Third, Asian American respondents are the most likely to select candidates that share one’s own origin or co-ethnics, with a 76 per cent probability. When ethnicity is not specified, and candidates are just described as ‘Asian American’ (pan-ethnic), the probability of selection drops to 69 per cent. When the Asian American candidate is specified as having a different national origin as the respondent or cross-ethnics, the likelihood of voting for that candidate drops even further to 59 per cent. However, all three marginal means of choosing Asian American candidates are greater than 0.5, implying that any Asian American candidate, regardless of their particular ethnicity, would be favored in an election compared to a white, black, or Hispanic candidate for Asian American respondents.Footnote 14

In sum, respondents are most likely to choose similar party candidates over candidates of similar race/ethnicity. Moreover, among similar race/ethnicity candidates, respondents are most likely to choose an Asian American candidate with their own ethnic origin (co-ethnics), followed by an Asian American candidate with no ethnicity specified (pan-ethnics), and finally, an Asian American candidate who does not share their ethnic origin (cross-ethnics). Even so, some form of racial cross-affinity exists for all three types of Asian American candidates: co-ethnic, pan-ethnic, and cross-ethnic. What is more important is that the Asian American (cross-ethnic) candidate is distinct from the co-ethnic and pan-ethnic candidates. Asian Americans (cross-ethnic) are members of a respondent’s ethnic out-group but racial in-group, meaning they occupy a space between in-group and out-group status that is still more preferable than the white, black, or Hispanic candidates.Footnote 15 It appears that there are important nuances in how Asian American voters evaluate descriptive representatives regarding national origin and ethnicity.

We also examine whether the estimated marginal means are asymmetrical by respondents’ partisan affiliation and the strength of their racial, ethnic, and partisan identities and find no major heterogeneity (see Figures A.14, A.16, and A.17 in the Appendix). A notable finding is that, unlike Study 1, respondents with high co-ethnic and pan-ethnic identities still continue to prioritize candidates who share their party over their race/ethnicity.Footnote 16

Trade-offs

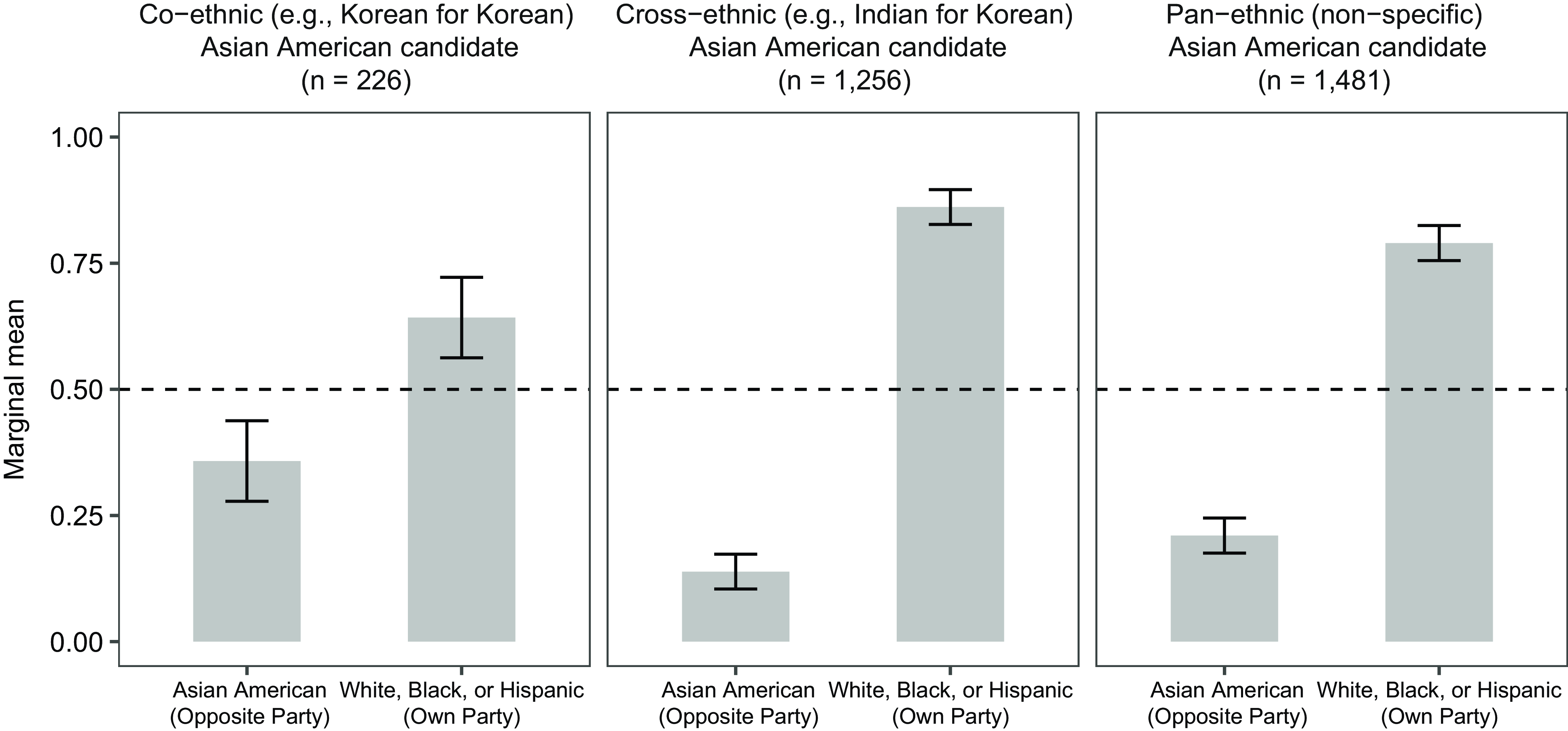

Finally, we analyze respondents’ decisions in trade-off pairs to examine whether Asian Americans are more likely to sacrifice descriptive representation for partisan representation. Figure 3 shows how often Asian Americans vote for candidates aligned with one characteristic but not aligned with another. That is, we choose profile pairs in which respondents compare an Asian American candidate (aligned with Race/Ethnicity) who is an opposite-party member (not aligned with Party) and a white, black, or Hispanic candidate (not aligned with Race/Ethnicity) who is an own-party member (aligned with Party).

Figure 3. Marginal means on binary vote choice (trade-offs) Note: the horizontal lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals.

In these trade-off situations, Asian American respondents continue to prioritize shared partisanship, as they consistently choose an own-party candidate who is white, black, or Hispanic more than 50 per cent of the time over an Asian American candidate who is from the opposite party. This finding does not vary based on whether the Asian American opposite-party candidate is a co-ethnic (for example, a Korean American Republican candidate for Korean American Democrats), cross-ethnic (for example, an Indian American Republican candidate for Korean American Democrats), or a pan-ethnic (an unspecified Asian American Republican candidate). When facing trade-off decisions that involve shared partisanship or shared race/ethnicity, Asian American respondents are always more willing to vote for the candidate who shares their party.

While race/ethnicity may be less critical than partisanship in determining vote choice in trade-offs, there is notable variation within descriptive representation itself (that is, across the left bars of the three panels in Figure 3). Asian American respondents are more likely to vote for co-ethnics of the opposite party (36 per cent) than those described as pan-ethnics or cross-ethnics. When candidates are just described as ‘Asian American’, the probability of vote choice drops to 21 per cent. When the Asian American candidate is specified as not having the same national origin as the respondent, however, the probability of voting for that candidate drops even further to 13 per cent.

One benefit of using profile pairs as the unit of analysis is that we can look at differences in trade-offs by the race/ethnicity of the other candidate for comparison. While keeping the Asian American opposite-party candidate fixed, we examine whether respondents react differently when their party candidate is either white, black, or Hispanic. The results are presented in Figure 4. While the pattern follows for white candidates (top row), there are substantial differences when Asian American respondents evaluate a black or Hispanic own-party candidate versus a co-ethnic opposite-party candidate. We find that Asian American respondents are willing to cross party lines to vote for an opposite-party, co-ethnic member only if their own-party candidate is black (first column, second row) or Hispanic (first column, third row).

Figure 4. Marginal means on binary vote choice by race of other candidate (trade-offs) Note: the horizontal lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Therefore, there seems to be a racial penalty extended to black and Hispanic members that is not present for white own-party members. Unlike previous results, Asian Americans will vote for the opposite party candidate 52 per cent of the time if the other candidate is black and 46 per cent of the time if the other candidate is Hispanic, neither of which are statistically significantly different than 50 per cent.Footnote 17

This behavior does not apply when the Asian American opposite-party candidate is either a cross-ethnic or pan-ethnic candidate (that is, the second or third column of the second or third row). In these instances, respondents revert to the previous pattern: they will vote for their own-party candidate regardless of whether or not they are white, black, or Hispanic.

One possibility to consider is whether these patterns reflect racial bias against black and Hispanic candidates. To assess this, we examine all profile pairs that include a black or Hispanic candidate on one side and a white candidate on the other. If racial bias were driving preferences, we would expect white candidates to be selected more often than black or Hispanic candidates. Instead, we find that white candidates are chosen 51.6 per cent and 50.0 per cent of the time over black and Hispanic candidates, respectively (both statistically indistinguishable from 50 per cent). We therefore do not find evidence for discrimination against non-Asian minority candidates compared to white candidates. This suggests that rather than racial animus against black and Hispanic candidates, our results are more likely driven by positive affect for Asian American co-ethnic candidates.

We examine the heterogeneity in trade-off choices among various subgroups of respondents, which are presented in the Appendix A.5. First, Democrats and Republicans follow much of the same patterns as the main results (see Figures A.22 and A.23).Footnote 18 Second, Figure A.24 shows the results for first-generation immigrants, who tend to have a weaker partisan identity (Hajnal and Lee Reference Hajnal and Lee2011). We find that they have stronger preferences for a co-ethnic candidate of the opposite party compared to second- and third-generation immigrants. The probability of voting for such a candidate is almost the same as the probability of voting for a white, black, or Hispanic candidate of the respondent’s party. However, these patterns are not seen for second- and third-generation immigrants. This is consistent with Raychaudhuri (Reference Raychaudhuri2018), who finds that first-generation Asian Americans have homogenous co-ethnic social networks, which is also correlated with a weaker partisan identity. This is in contrast to second- or third-generation Asian Americans, who describe their partisan socialization as occurring through conversations with a more diverse network of peers who are white, black, or Hispanic (Raychaudhuri Reference Raychaudhuri2018).

Finally, we again look at the differences in marginal means by respondents’ partisan, co-ethnic, and pan-ethnic social identities (see Figures A.25 and A.26). Just as expected, we find that respondents with the highest partisan identities are more likely to penalize all Asian American opposite-party candidates, while those with the lowest partisan identities are equally likely to vote for co-ethnic opposite-party candidates and white, black, or Hispanic own-party candidates. Regarding the heterogeneity by respondents’ ethnic identity, we see a less clear pattern in Figure A.26. Those with the highest and lowest levels of co-ethnic identities are again equally likely to vote for either the co-ethnic opposite-party or the white, black, or Hispanic own-party candidate.Footnote 19 However, those with a medium level of co-ethnic identity are significantly more likely to choose a white, black, or Hispanic own-party candidate.

Overall, Asian Americans are almost always willing to trade off their descriptive representation for partisan representation in a competitive electoral setting. However, Asian Americans seem to be willing to trade off their partisan representation for descriptive representation in one circumstance only – when a co-ethnic Asian American opposite-party candidate competes against a black or Hispanic own-party candidate. Descriptive representation must be on the terms of co-ethnicity.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the broader literature on voters’ preferences for descriptive and partisan representation. The common narrative that Asian Americans have weak partisan attachments is more complicated when considering the heterogeneity within the group. When asked outright about preferences for collective representation, Asian Americans prioritize descriptive representation over partisan representation. However, when voting for a specific candidate, they are almost always willing to trade off descriptive representation for partisan representation. All else equal, they will still vote for any candidate described as Asian American (co-ethnic, cross-ethnic, and pan-ethnic) more often than other candidates (that is, white, black, and Hispanic). These results suggest a shared affinity for candidates who are Asian Americans compared to non-Asian American candidates, regardless of whether or not these candidates are of the same ethnicity. But if Asian American respondents encounter a co-ethnic candidate of the opposite party, they are just as likely to vote against their own party if their only in-party alternative is a black or Hispanic candidate.

The contrasting findings between Study 1 and Study 2 – where respondents preferred descriptive over partisan representation at the collective level but favored partisan over descriptive representation at the dyadic level – raise important questions about how theories of representation should be conceptualized. These patterns are consistent with Casellas and Wallace (Reference Casellas and Wallace2015), who argue that Latino voters care less about descriptive representation at the dyadic level because individual legislators have limited influence. In contrast, collective representation allows co-ethnic legislators to form coalitions that can shape policy outcomes. Both descriptive and substantive representation serve as instruments for achieving policies that benefit a shared racial or ethnic group, such as anti-hate crime laws or immigration reform. Future studies could extend this logic by varying the specific policies supported by candidates to better isolate how policy goals relate to preferences for descriptive and substantive representation.

At the same time, this discrepancy between collective and dyadic representation may be an artifact of the survey design. If respondents are aware of their underrepresentation at the collective level or are surrounded by co-ethnic peers, they may feel compelled to choose descriptive representation over partisan representation, mirroring the pressures in the real-world of co-ethnic social influence (Raychaudhuri Reference Raychaudhuri2018). In contrast, the conjoint design in the dyadic representation study is better suited to capture respondents’ underlying preferences, as it reduces social desirability bias (Horiuchi et al. Reference Horiuchi, Markovich and Yamamoto2022). Still, it is important to interpret these results in light of the broader institutional and external factors that may shape preferences in a survey environment compared to the real world.

Our second contribution is to the growing study of pan-ethnic groups. Asian Americans are often studied as a monolith even though they differ in ethnic, cultural, religious, and phenotypical backgrounds (Junn and Masuoka Reference Junn and Masuoka2008; Sadhwani Reference Sadhwani2022a). We find that Asian American candidates who are explicitly not of the same origin as the survey respondents (that is, cross-ethnic) are penalized compared to Asian American candidates described in pan-ethnic terms. For example, Chinese Americans are more likely to vote for a candidate described as an ‘Asian American’ than a candidate described as a ‘Korean American’, even considering other characteristics. This finding opens up avenues for further research on heterogeneity among different ethnic groups within the broader racial group, such as examining potential explanations regarding animosity, competition, or historical differences (Liu and Carrington Reference Liu and Carrington2021).

At the same time, our results raise concerns about the potential for building multiethnic and multiracial coalitions (see, for example, Perez et al. Reference Perez, Vicuna, Ramos, Phan, Solano and Tillett2022; Perez et al. Reference Perez, Vicuna and Ramos2023). Asian Americans may continue to face difficulties in organizing around shared descriptive interests. Continued immigration from Asian countries may reinforce existing ethnic boundaries among first-generation immigrants, making it harder to develop a unified political identity (Jiménez Reference Jiménez2008). While Asian American candidates have succeeded in building multiracial coalitions with solid support from black and Hispanic voters (Lublin and Wright Reference Lublin and Wright2023), uniting Asian American voters across ethnic lines may remain challenging. The penalty applied to black and Hispanic candidates, even when they are co-partisans, raises the possibility that racial tensions between minority groups may still interfere with meaningful coalition building.

Scholars have theorized Asian Americans to be elevated above, yet ostracized politically compared to black Americans (a process that Kim (Reference Kim1999) calls relative valorization and civic ostracization). Our results suggest that while a penalty against black candidates exists, it does not necessarily stem from Asian Americans discriminating against black candidates, at least when we examine white–black pairs. We find a similar penalty for Hispanic candidates, even though Hispanics may be perceived as more similar to Asian American voters compared to black candidates because of their immigrant experiences and pan-ethnic categorizations (Masuoka and Junn Reference Masuoka and Junn2013; Zou and Cheryan Reference Zou and Cheryan2017). While the direction of the estimates is consistent with a penalty for black and Hispanic intraparty candidates when up against co-ethnic Asian American candidates, the limited sample size for these pairings restricts our ability to draw strong inferences. Our analysis suggests that the pattern is more likely driven by a preference for in-group (Asian American) candidates than by out-group animus, though we also cannot directly identify the mechanism because our survey did not include measures of racial resentment or stereotyping. Future studies should include such measures and use designs that enable higher-powered subgroup comparisons to assess whether these penalties result from prejudice, perceptions of substantive representation, or something else.

We acknowledge several other limitations of our research and areas for future research. First, while examining shared pan-ethnicity reveals essential insights about the type of descriptive representation Asian Americans value, it is difficult to imagine a ‘pan-ethnic’ but otherwise ethnically ambiguous candidate in the real world. One reason why we find the preference for pan-ethnic candidates over cross-ethnic candidates may be because respondents infer that Asian Americans (unspecified) are still co-ethnics. While candidates may campaign as ‘Asian Americans’ without reference to a specific identity in the real world, the distinctiveness of a national origin surname, campaign advertisements, or some phenotypical features may give voters some clues to the ethnicity of that candidate.Footnote 20 At the same time, candidates may strategically appeal as an ‘Asian American’ to increase their appeal to other Asian American constituents with whom they do not share a common ethnicity. The effectiveness of this framing strategy on its own is worth considering (see, for example, Boudreau et al. Reference Boudreau, Elmendorf and MacKenzie2019; Hurst Reference Hurst2023; Wu Reference Wu2023). While the profile-level conjoint allows us to simulate how voters make decisions in trade-off contexts (that is, comparing two candidates side-by-side on the ballot), we recognize that different types of presentations may improve the ecological and external validity of the study. Future experiments can reflect other aspects of the real world, such as campaign messaging or constituency communications, in order to determine the relative effects of these pan-ethnic Asian American and more specific ethnic American (for example, Korean American) frames when combined with more information about the candidates, such as last names and phenotypes.

Additional opportunities exist to study trade-offs among other minority groups or salient group identities such as gender or sexuality. Other pan-ethnic groups, such as African Americans and African immigrants (Gooding Reference Gooding2021) and pan-Indians and Native Americans (Herrick and Mendez Reference Herrick and Mendez2019), have yet to be studied in terms of trade-offs. As party lines and coalitions continue to shift, studying such interactions becomes more relevant.

Finally, while we only examine the US context, other major Western democracies, such as the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, have substantial Asian diaspora populations (see, for example, Martin and Blinder Reference Martin and Blinder2021; Pietsch Reference Pietsch2017). As Asians are also the largest non-white racial group in those countries, this group plays an increasingly critical role in the future of multicultural democracies, along with the potential backlash to this racial, ethnic, cultural, and religious diversification.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425101324.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OSSXEC.

Acknowledgements

Earlier drafts of this paper were written as a part of John J. Cho’s Honors Thesis submitted at Dartmouth College and presented at the 2022 Midwestern Political Science Association. We thank Jennifer Wu, Benjamin Valentino, Lucas Swaine, David Bodovski, Taran Samarth, and panel members and participants at the 2022 MPSA and Honors Thesis Presentations for their useful feedback.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Stamps Scholars Program and the Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for Public Policy.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.