Much has been said and written about democracy. From Aristotle to today, a broad variety of theories and meanings of democracy have been expressed by philosophers, politicians, and lay persons. And there have been different realizations of democracy over time. In fact, there is no single nor ideal meaning of democracy but rather a multiverse of concepts, theories, definitions, and meanings. The multiverse's commonality seems to be that they all anchor their argumentation on how people can and should be governed in the notion of democracy.

Whereas some models of democracy (Reference HeldHeld 2006), such as republican, deliberative, and especially liberal democracy, are predominant in contemporary political theory and practice, other approaches of democracy were rather “out of sight” of mainstream western political thought until more recent writers promoted the reception and comparison of non-western political thought (e.g., Reference DallmayrDallmayr 2004; Reference Freeden and AndrewFreeden and Vincent 2013; Schubert and Weiss 2016; Reference WeissWeiss 2020). The same is true when it comes to meanings of democracy formulated by politicians and lay people, as people vary widely in defining democracy. For example, Reference GagnonJean-Paul Gagnon (2020) identifies more than 3,500 different “complex designators” of democracy in English language literature that specify meanings of democracy by adding adjectives or short descriptions. Others, like Reference NaessArne Naess (1956) or David Collier and Steven Levitsky (1997), find a substantial variety of definitions.

Studies on meanings of democracy show that people construct democracy differently depending on regional, historical, and political contexts (Reference Andersen, Jennie L. and KüllikiAndersen et al. 2018; Reference Bratton, Robert and EmmanuelBratton et al. 2005; Reference BrowersBrowers 2006; Reference Canache, Jeffery J. and Mitchell A.Canache et al. 2001; Reference CanacheCanache 2012; Reference Dahlberg, Sofia and SörenDahlberg et al. 2020; Reference Dalton, Doh Chull and WillyDalton et al. 2007; Reference Frankenberger and DanielFrankenberger and Buhr 2020; Reference SchafferSchaffer 2014; Reference Shin and Hannah JuneShin and Kim 2018). This leads to different orientations toward politics (e.g., Reference Ferrín and HanspeterFerrín and Kriesi 2016; Reference Wegscheider and ToralfWegscheider and Stark 2020) and different actions to be taken. Reference SchafferFrederic Schaffer (2014) argues that the wide range of complex meanings of democracy can only be grasped by using qualitative methods. In his interview-based research in Senegal (2000) and the Philippines (2014), he shows the multivalence in understanding complex terms such as democracy. Similar studies showing local, regional, and national differences can be found on the Arab World (Reference BrowersBrowers 2006) and Russia (Reference CarnaghanCarnaghan 2011). Other authors use Q-Methodology to create taxonomies of meanings of democracy for the United States (Reference Dryzek and JeffreyDryzek and Berejikian 1993), post-communist Europe (Reference Dryzek and Leslie TemplemanDryzek and Holmes 2002), and Estonia (Reference Andersen, Jennie L. and KüllikiAndersen et al. 2018). In a phenomenological approach to meanings of democracy, we show that meanings of democracy vary according to their “world at hand” and influence both evaluation of democracy and political action (Reference Frankenberger and DanielFrankenberger and Buhr 2020). Norma Osterberg-Kaufmann and Ulrich Stadelmaier (2020) use repertory grid and semantic differential methods to identify different clusters of meanings of democracy in a study of Singaporean middle classes. Stefan Dahlberg, Sofia Axelson, and Sören Holmberg (2020) point at the necessity to analyze the use of the concept of democracy in its natural habitat to identify cross-cultural discrepancies.

For a comparative democratic theory as an inductive and indefinite task (Reference WeissWeiss 2020) that aims at identifying relevant cases of non-western democratic thought, interpreting it from a globally comparative perspective and playing back conceptual insight to democratic theory (Reference WeissWeiss 2020: 32), this poses several theoretical, conceptual, methodological, and empirical challenges, for example, normativity of democratic theory, concept formation, comparison as methodological foundation, and data to be included in theory development. We argue that Grounded Theory is an approach and methodology we can use fruitfully to address these issues in the context of comparative democratic theory.

In the following sections we first discuss some core challenges for developing a comparative democratic theory. Then we introduce the basic assumptions and procedures of Grounded Theory and discuss its strengths and weaknesses as a method for comparative democratic theory. We then present a sample analysis of 17 documents and the resulting grounded comparative democratic theory. Finally, we reflect on some strengths and weaknesses of such an endeavor and highlight the benefits of applying Grounded Theory in developing a comparative democratic theory rooted in empirical data from unlikely and unorthodox sources.

Challenges for a Developing a Comparative Democratic Theory

We argue that if a comparative democratic theory is to be indefinite, then a normative, ideal, and a priori formulated concept of democracy is not suitable. Rather it has to be open, bottom-up, and formulated without predefining the phenomenon by theoretical reflection. Here, a genuine problem of normativity arises. For example, Christian Welzel argues that “only under a normative judgement of empirical realities are we able to study the sources and consequences of these realities in a meaningful manner” (2021: 114–115). We argue that the opposite is true. Only without pre-judging empirical realities can we be sure not to miss important phenomena that contribute to a more comprehensive theory of democracy.

If a democratic theory departs from a normative or conceptual core, we might learn more about how much the world resembles the mindset of the researchers rather than about the existing meanings and varieties of democracy. As consequence, we might miss important issues and facts, and even commonly shared normative standards. Open-endedness allows us to proceed and include material and insights from various places that might change or at least challenge established concepts and to avoid misjudgments of specific phenomena that do not fit into the pre-chosen role model but still could be considered democratic.

On a conceptual level, concept formation is broadly and controversially discussed in political science (cf. Reference Collier and James E.Collier and Mahon 1993; Reference Collier, Jody and JasonCollier et al. 2012; Reference GerringGerring 1999; Reference Gerring and Paul A.Gerring and Barresi 2003; Reference GouldGould 1999; Reference SartoriSartori 1970, Reference Sartori and Sartori1984) and often linked to democracy as a core example (Reference Collier and StevenCollier and Levitsky 1997, Reference Collier, Steven, David and John2009; Reference DalyDaly 2003). Whereas Reference SartoriGiovanni Sartori (1970) advocates classical concept formation with mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive categories, David Collier and James Mahon (1993) argue that instead of using classical categories, two other strategies can be used: family resemblance (Reference WittgensteinWittgenstein 1968) and radial (Reference LakoffLakoff 1987) categories.

Basically, there is no consent on what type of categorization should be used, as all three strategies have their advantages and disadvantages. One of the main arguments against radial categories is that they only offer minimal, often empty concepts, whereas family resemblance categories are said to mix substantially different phenomena. In turn, classical categories are facing critique for being too static and “western.”

Thus, for the task of a rather inductive comparative democratic theory, the question of concept has to remain unanswered until a comparison is done, as only comparison can show if there are root concepts and radial categories, family resemblances, or even classical categories to be formed. This straight inductive strategy of concept formation does not allow for letting the comparison start from a preexisting concept, but rather it is about controlling “whether generalizations hold across the cases to which they apply” (Reference SartoriSartori 1991: 244). Or to put it more simply, comparing is about finding systematic similarities and differences between observed phenomena—of concepts of democracy in this case.

On a methodological level, if we want to find similarities and differences in concepts of democracy, the question of how to compare arises (Reference SartoriSartori 1991). For the purpose of a comparative democratic theory as previously mentioned, a rather inductive approach seems to be preferable in order to keep theory building and concept formation as open as possible. Initial steps should therefore be made by using qualitative, interpretive approaches to identify the peculiarities and commonalities of meanings of democracy (cf. Reference Frankenberger and DanielFrankenberger and Buhr 2020), rather than using standardized, theory-driven quantitative methodology.

Empirically, a main question is what phenomena, material, and data the researcher should include. Traditionally, a political theory approach on democracy might tend to focus on writings by philosophers and political theorists who are identified according to the orders of discourse (Reference FoucaultFoucault 1971), thus reproducing canonical knowledge and again marginalizing other meanings of democracy found in non-canonical sources, including lay persons, and thinkers from non-western contexts. According to Barney Glaser and Judith Holton, “all is data” (2004). So, theoretical concepts as well as material from lay people can be included in an analysis if we treat them all equally as data. If we use mixed data, for example, from lay people, thinkers, and politicians, this would even be more comprehensive.

In a nutshell, comparative democratic theory has to: (a) suspend previous knowledge and imprint, (b) remain open in concept formation, (c) apply inductive and qualitative methodology, (d) compare frequently and systematically, and (e) be open for data from unexpected and unorthodox sources. We argue that Grounded Theory as a specific general “methodology in how to get from systematically collecting data to producing a multivariate conceptual theory” (Reference GlaserGlaser 1999: 836) meets these criteria and therefore can be used fruitfully in the context of comparative democratic theory.

Grounded Theory and Democracy Research

Grounded Theory as developed by Glaser and Anselm Strauss (1965, 1967, 1968) aims at a “conceptual theory, abstract of time, place, and people” (Reference Glaser and JudithGlaser and Holton 2004). It is comparative in nature and focuses on identifying structure and reducing complexity in data (Reference Strauss and JulietStrauss and Corbin 1990, 111). Theory building is strictly rooted in the data as it is “limited to those categories, their properties and dimensions, and statements of relationships that exist in the actual data collected—not what you think might be out there but haven't come across” (Reference Strauss and JulietStrauss and Corbin 1990: 112).

Grounded Theory was subsequently developed in different directions with slightly different epistemological and methodological orientations (Reference FlickFlick 2018: 6–11). Strauss and Corbin combined inductive and deductive strategies and highlighted verification as an important element of Grounded Theory. Others adopted constructivist (Reference Bryant and KathyBryant and Charmaz 2007; Reference Charmaz, Frederick J., Kathy, Linda M., Ruthellen, Rosemary and EmalindaCharmaz 2011, Reference Charmaz2014, Reference Charmaz2017) and postmodernist (Reference ClarkeClarke 2005) approaches and accounted for questions of data and theory construction beyond an “all is in the data” perspective. Still others are engaged with developing grounded normative theory by incorporating data and findings from empirical research into the process of justifying normative claims (Reference AckerlyAckerly 2018; Reference Ackerly, Luis, Fonna, Genevieve Fuji, Chris and AntjeAckerly et al. 2021; Reference CabreraCabrera 2020). We follow the perspective of constructivist Grounded Theory and argue that researchers cannot completely ignore and suspend their previously gained knowledge.

There is a vibrant and ongoing discussion around the question of the “right” approach to Grounded Theory. We do not want to engage with these debates in extenso in this article. For a discussion, see for example, Antony Bryant and Kathy Charmaz (2007), Reference KelleUdo Kelle (2007), or Reference FlickUwe Flick (2018). We argue that the versions of Reference Strauss and JulietStrauss and Corbin (1990) as well as the constructivist and postmodernist versions of Grounded Theory (e.g., Reference Charmaz, Frederick J., Kathy, Linda M., Ruthellen, Rosemary and EmalindaCharmaz 2011; Reference ClarkeClarke 2005) are suitable for the task of comparative democratic theory, as they take into account the necessity of verifying the data, including literatures, reflecting the roles of researchers and researched in constructing data about the world, and selecting data for Grounded Theory (Reference CharmazCharmaz 2014: 27; Reference ClarkeClarke 2005: 75f; Reference DunneDunne 2011).

In the following paragraphs we outline the main features of Grounded Theory as developed by Reference Strauss and JulietStrauss and Corbin (1990) with some amendments regarding methodology, selection of cases and data according to Reference ClarkeClarke (2005), Reference CharmazCharmaz (2014), Reference ScottJohn Scott (1990) and Uwe Reference FlickFlick (2018). The core element of Grounded Theory is coding. Reference Corbin and AnselmCorbin and Strauss (1990) propose three major types of coding: (1) open, (2) axial, and (3) selective coding.Open coding aims at breaking up, comparing, conceptualizing, and categorizing data along the core content and to find labels that represent the content in a more abstract way. Coding in vivo is one of the first steps in conceptualizing data (Reference GlaserGlaser 1978: 70; Reference StraussStrauss 1987: 33). If we find the phrase “the fulfilment of the will of the people” (Doc 05,5) as a description of democracy, we can use this as an in vivo code and will thus have a concept that is linked to democracy. Democracy itself serves as a category. The concept denotes a specific property of the category, namely the fulfillment of the will of the people. If we want to come to a grounded theory of democracy, then we would have to find and compare properties and dimensions that further specify the category democracy across cases.

Axial coding connects categories and their subcategories in terms of conditions and consequences (Reference Strauss and JulietStrauss and Corbin 1990: 96) in a coding paradigm model: Causal conditions bring about the phenomenon that itself is at the heart of research interest. Context includes a “specific set of properties that pertain to the phenomenon” as well as a “particular set of conditions within which the action/interaction strategies are taken” to handle the phenomenon (Reference Strauss and JulietStrauss and Corbin 1990: 101). Intervening conditions can be defined as the broader structural context pertaining to a phenomenon that bear upon action or interaction, including time, space, culture, economy, technology, history, and environment that could be of different relevance in the respective context (Reference Strauss and JulietStrauss and Corbin 1990: 103).

Selective coding as a final step fills in gaps by adding further data and analysis and validates the theory against the data (Reference Strauss and JulietStrauss and Corbin 1990: 133). For example, by analyzing many documents, one then can extrapolate the most frequent combinations of concepts in the light of this coding paradigm. A hypothetical axial coding of democracy then could be the following: As “the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail” (Doc 01,4). [Cause], there is a “government of the people, by the people, for the people” (Doc 02,4) [Phenomenon] that has to “Provide a better life for all” (Doc 08,14) [consequence] by claiming for “peace, unity, goodwill and brotherhood” (Doc 10,18) [strategy] under conditions of “law-based governance” (Doc 14,89) [context] and a situation where “lobbyists determine much of what goes on in congress” (Doc 04,30) [conditions].

Grounded Theory is genuinely comparative (Reference GlaserGlaser 1965: 51; Reference Glaser and Anselm L.Glaser and Strauss 1967: 102). Comparison systematically starts as soon as coding begins and makes Grounded Theory research an iterative, circular process (Reference Glaser, George and J. L.Glaser 1969: 20). Kelle highlights that “by looking for commonalities and differences between incidents, what is called ‘the constant comparative method’ can reveal two different kinds of theoretical properties: (1) possible sets of subcategories of a given category, and (2) relations to other categories” (2007: 196).

Toward a Grounded Theory of Democracy—An Exemplary Analysis

Given the openness, the abductive, inductive, and comparative methodology as well as the theoretical claims outlined earlier, Grounded Theory is a promising methodology for developing a comparative democratic theory out of empirical data, as our exemplary analysis of speeches of political leaders that deal with democracy illustrates. We chose these speeches because political leaders represent a strand of thought that is dominant in their country and time and have an impact on lay perceptions of democracy that is influential for public discourse.

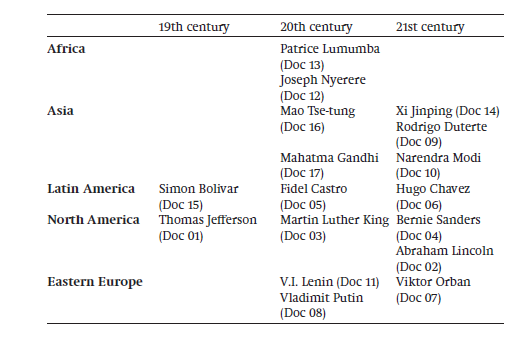

To have a broad variety of different meanings of democracy, we chose speeches from different times, places, cultures, and traditions of political thought. This includes speeches from North America, Latin America, Africa, Eastern Asia, and Asia from the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first century and liberal, socialist, communist, nationalist, and exceptionalist strands of thought. Table 1 displays the classification of authors along the regional and historic dimension and the abbreviations (Doc 01–17) used in the following analysis. The data include famous speeches like Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address or Martin Luther King's “I Have a Dream” speech as well as inaugural addresses and public reports to congresses and committees. Copies of these documents can be found in the online appendix to this article.

Table 1: Classification of Speeches

Source: Authors’ own compilation

Starting with the oldest document, Thomas Jefferson's first inaugural speech (Doc 1), codes, concepts, and categories emerged. For Jefferson, the principles of a “wise and frugal government” include first and foremost the will of the majority but also equality, justice, peace, republicanism, federalism, a minimal state as well as freedoms of religion, press, person, trial, and the will of the law. He formulates, for a colonial, racialized, and mostly male and Christian audience, the principles of an enlightened, liberal, and republican democracy, even though not mentioning the word democracy. While doing so, he evokes notions of religion when he speaks about the chosen and beloved country (Doc 01,3 and 05), his own weakness before the task of being president (Doc 01,3), and providence and blessings. There are also notions of struggle (Doc 01,3) for the “sacred principle” of majority rule and minority protection through equal law and rights (Doc 01,4), which has to be defended by minimal, “wise and frugal” government (Doc 01,5).

These concepts and categories either originate in in vivo codes (“sacred principle”; “chosen country”) or in more abstracting and paraphrasing open coding (“struggle”; “majority rule”). They served as basis for further comparison of the documents and were used parallel to further open and in vivo coding. We included the documents step by step and used constant comparison to subsequently carve out the core categories of a Grounded Theory of democracy until we reached theoretical saturation, that is, no new codes emerged. Thereafter we compared the documents regarding already existing codes as well as newly emerging codes, which means that once a new code was found, the already analyzed documents had to be reassessed.

For reasons of exemplarily displaying the results of the analysis, we decided to focus on presenting the concepts and categories and their core properties emerging from open coding in a first step. In a second step we used axial coding and the coding paradigm to develop a transactional model of democracy. These different steps of analysis often go hand in hand in a parallel and iterative process that through comparison leads to the results of the analysis.

The concept “the people” quickly crystallizes as one of central importance, as it appears in all documents and is by far the most frequently used concept in the sample with 603 appearances. To be clear, Grounded Theory is not so much about word counts (Reference SuddabySuddaby 2006: 636; Wolfswinkel et al. 2011): The simple fact that a word is mentioned quite often does not necessarily mean that it is meaningfully linked with other concepts under review. For example, even though mentioned more frequently than nation or state, the words country or world are not systematically linked with other categories revealed by the following analysis.

In close connection with the concept “the people,” the concept of “People's Government” emerges. It turns out to be the core category, around which other categories and concepts can be grouped. Notions of people's government and its properties also appear in all documents in various forms, such as:

• “government of the people, by the people, for the people” (Doc 02,4);

• “Democracy is the fulfillment of the will of the people” (Doc 05,5);

• “Democracy as the “running of the country by the people” (Doc 14,16); and

• “A Government not of the People is not a democracy” (Doc 05,6).

It is about the will of the people (Docs 01; 05–07; 12–14) and the will of the majority (Doc 01,4 and 6; Doc 07,34; Doc 12,20; Doc 13,23), which can only be realized through the “participation of the people” (Doc 10,22) and the “support and cooperation of the people” (Doc 09,4). To implement the will of the people, the government then is an important institution that must show “responsiveness to their needs and demands” (Doc 12,21) and “feel their pulse” (Doc 09,5).

For a grounded theory of democracy developed out of the chosen sample material this means that democracy is about the will of the people and its realization, usually within national or nation state boundaries. But differences are already apparent here, as government of the people and the running of a country by the people rather imply direct involvement of the people in governing themselves, whereas the fulfillment of the will of the people points at a more unspecific responsibility to bring about the will of the people. This could theoretically include an enlightened monarch as well as a representative government, or a strong party, as long as they know and realize the will of the people.

The concepts emerging from the material are not that clear here. There is also a difference between the will of the people and the will of the majority that arises from the material. For example, Victor Orban argues that “the individual's appeal to freedom must not override the interests of the community. There is a majority, and it must be respected, because that is the essence of democracy” (Doc 07,34). He links majority with community and thus denies the equal rights of minorities, which is in sharp contrast to Jefferson's note that “the minority possess their equal rights” (Doc 01,4) that have to be protected as well. Moreover, the definitions of the people vary significantly between the documents and the interpretive sovereignty over how “the people” is defined as a property of the category “people's government” allows for opening different types of democracy.

One strand of documents, in principle, sees the entirety of individuals as constituting the people. They are “created equal” (Doc 02,2; Doc 03,8 and 19; Doc 12,24) and are granted “unalienable rights” (Doc 03,5) “to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement” (Doc 01,5) as well as equal and exact justice and liberty (Doc 01,4; Doc 02,2; Doc 03,5; Doc 08,15). Even if the entirety of individuals originally was limited to male and white citizens of a country, it was later expanded to women and non-white individuals after decades of struggle. Comparing these findings with established terms of democratic theory, this strand closely resembles the liberal strand of democracy.

A second group of documents considers the people to be those individuals belonging to a certain class of society. These can be the “peasants” (Doc 05), the proletariat (Doc 11), or an alliance of working class, peasantry, urban petty bourgeoisie (Doc 16,12) that is installing “a people's democratic dictatorship under the leadership of the working class” (Doc 16,12). In this system, “genuine freedom and equality” are realized and “the equality of citizens, irrespective of sex, religion, race, or nationality . . . is given immediate and full effect” (Doc 11,24). This strand constitutes a socialist, or proletarian meaning of democracy in the tradition of Marxist-Leninist thought.

A third type of democracy emerges from documents that highlight certain characteristics like a distinctive national character, unity, and “the subordination of personal interests to the common good” (Doc 09,21) as important features of the people. This notion of the “nationally-oriented people” (Doc 07,32) includes unity, citizens responsibility, and benefits for the community and states “that the individual's appeal to freedom must not override the interests of the community.” (Doc 07,34, cf. Doc 10,11). Unity, solidarity, and homogeneity of the people are superior to their individual liberties and interests in this meaning of democracy, which could be called populist or “illiberal democracy” (Doc 07,26).

The people must develop strength, unity, and faith and struggle to overcome the challenges to democracy. Struggle (mentioned in every document) and revolution (Docs 01; 03; 05; 06; 11; 14; 16) are major strategies for the fulfillment of the will of the people and the unfolding of “real democracy” (Doc 05,15). Depending on the kind of challenge they face, the struggle has different targets from segregation to imperialism, from poverty to classless society, from national unity to individual rights. They all have in common that democracy is something you must fight for or to defend against its enemies in a heroic “quest for freedom” (Doc 03,16) or “crusade for a better and brighter tomorrow” (Doc 09,39).

This quest for freedom and democracy is linked to religious insinuations and notions and put forward with a sense of mission. Those striving for the realization of democracy often recurse to such missionary zeal and religious charge that can be found in at least 11 documents (01–05; 07; 09; 10; 12; 13; 17), ranging from associations of providence, sacred principles and obligations, destiny, faith and dignity to more obvious linguistic images of “valley of despair” (Doc 03,17) to “worship of money” (Doc 04,20) and even more obvious linkages like “democracy owes its existence to Christianity” (Doc 07,34). This finding points at the necessity to consider religious dimensions while comparing meanings of democracy.

Visions of Democracy

Visions of democracy are developed to a different degree in the documents. Some provide a complex concept or theory of democracy. Castro, Mao, and Lenin (Docs 05; 11; 16) promote a model of proletarian democracy. Similar to Xi, they all promote a “democracy that lives through the direct participation of the people” (Doc 15,5) in a nonrepresentative but commune and council-based pure democracy. Sanders (Doc 04) highlights democratic socialism as a “vibrant democracy based on the principle of one person one vote” (Doc 04,58) that promotes economic and social justice actively (Doc 04,58). Orban (Doc 07) offers a model of “illiberal” democracy based on Christian values and the subordination of the individual under the common interest, and Xi (Doc 14) develops the vision of a socialist democracy that includes strong leadership of the Communist Party as well as permanent consultation and moderate development.

Others envision specific elements that must be realized to gain democracy. In almost all documents, except Lenin (Doc 11) and Gandhi (Doc 17), the quest for unity as a characteristic of ideal democracy can be found. But unity can mean different things from unity “in common efforts for the common good” (Doc 01,4) to national unity (Docs 01–05; 07–10; 12–16), highlight citizens responsibility (Doc 10), subordination of personal interest (Docs 07; 09; 10; 16) and benefits to the community (Docs 01; 07; 10). The nation and national unity are the most important features when it comes to democracy in these documents, which conceptualizes both democracy and the people (the demos) with clear territorial boundaries. Unity often has strong appeals of subordination under a common goal, under national interest or ideology, or in the name of the fight against grievances like segregation, poverty, or inequality. Without unity, the democracy to come cannot be reached.

The visions of democracy presented in this section were derived by constantly comparing the results of open coding and conceptualizing them on a more abstract level to highlight the aspects in which documents show similarities and differences.

Concluding Reflections

We argued that a comparative democratic theory has to: (a) suspend previous knowledge, (b) remain open in concept formation, (c) apply inductive and qualitative methodology, (d) compare frequently and systematically, and (e) be open for data from unexpected and unorthodox sources. As our analysis shows, Grounded Theory offers a genuinely comparative approach for analyzing meanings of democracy as well as for generating a comparative democratic theory that is rooted in data. It is powerful in identifying core concepts and visions without using a priori theory or previous knowledge about specific concepts of democracy to predetermine the analysis. Nevertheless, this methodological approach comes along with some caveats and challenges.

One challenge is linked with the status of previous knowledge. Here, the dualism between “discovering theoretical categories and propositions from empirical data versus drawing on already existing theoretical concepts when analysing data” (Reference KelleKelle 2007: 134) is highly relevant for analyzing meanings of democracy and developing a grounded comparative democratic theory. To be clear, to use the label “democracy” does not mean to buy any related concept. If we want to build a grounded theory of democracy, we need to suspend these theoretical meanings, especially if we do not want to force categories on the data. But to avoid parochialism (Reference SartoriSartori 1991) we will still have to check and compare claims made in primary documents against relevant existing literature. This is especially true if we talk about marginalized meanings of democracy that presumably do not fit into the canons of political thought.

Another challenge is to remain open in concept formation. Kelle argues that theoretical concepts with low empirical content can be useful for generating Grounded Theory (Reference KelleKelle 2007: 147). One could argue that democracy is such a concept with low empirical content (cf. Reference GallieGallie 1956) and then use the term to identify and analyze data to fill it with empirical concepts and visions. For example, there is a striking, but not surprising, overlap between our analysis and prior, theoretical knowledge about democracy concerning the role of “the people.” This finding highlights the necessity of Grounded Theory in two aspects. First, it shows that the core category “the people” holds both empirically and theoretically. Second, it adds substantially to understand who “the people” are and what role the specific definition of “the people” plays in understanding the respective concepts and theories of democracy. The value added of applying Grounded Theory is capturing these differences, relating them systematically to other categories and concepts, and comparing the causal models of democracy developed by inductive analysis.

This also highlights the usefulness of frequent and systematic comparison for concept formation in comparative democratic theory. Subtypes of democracy, for example, emerged as our analysis progressed. But constant comparison as a qualitative methodology has a limited processing capacity. Going back and forth between codes while analyzing data is an intensive task that produces manifold codes that need to be compared, condensed, and reformulated into concepts and visions (or definitions, narratives). Our relatively small amount of data produced a complex system of categories that needed to be integrated. Also, a systematic axial coding of concepts is necessary, which sometimes does not lead to satisfactory dimensions, and not all categories were included to the final model of democracy.

Another issue of concept formation comes along with the nature of Grounded Theory as a “transactional system” (Reference Strauss and JulietStrauss and Corbin 1990: 159). Analyzing meanings of democracy then is analyzing how people describe the way they are governed or the way they want to be governed under conditions of democracy. We then would have to understand a grounded theory of democracy as a theory of “doing democracy” in the sense of constructing the reality of democracy as it is perceived. And then, there also can be a normative grounded theory (cf. Reference AckerlyAckerly 2018 for a discussion of the term) of democracy, if we include the causes, phenomena, and consequences of, for example, people's government and how people evaluate them without any need of assuming and settling antecedent principles.

The openness for data from unexpected or unorthodox sources is another strength of Grounded Theory. In our analysis, the emerging concepts represent a broad variety of different models of democracy, some of them scholars of democratic theory are familiar with. One could argue that this would have been different when we only included texts from Marxist-Leninist thinkers. This leads to the challenges of data selection and theoretical saturation. As theoretical saturation is reached when (a) no new or relevant data seem to emerge from the data regarding a category and (b) a dense system of categories is developed and integrated in the paradigm model, a systematic variation and expansion of data is indicated, if we want to develop a more general or formal Grounded Theory (Reference Strauss and JulietStrauss and Corbin 1990: 174) of democracy. This would imply that we must study material on democracy from different sources, times, places, and people and to compare them constantly to find out whether a core category emerges and to reach a theoretical saturation. Reference CharmazCharmaz (2014) points at the possibility to select so-called extant documents, which are not produced for research but selected by researchers according to the principles of authenticity, credibility, representativeness, and meaning (Reference ScottScott 1990: 6). This then can and should also include writings of philosophers and scientists.

For a grounded comparative democratic theory, the foregoing implies a broad and diverse sampling of material including scholarly writings to create maximal variance in the data and greater density and formality in the analysis. Thus we suggest to re-study democracy by including data from unlikely places, from thinkers, politicians, and lay persons, and to let concepts and structures of democratic theory emerge by comparing data and integrating them into a formal theory of democracy.

Appendix 1: Documents included in the Analysis

Document 1 (Doc 1): Jefferson, Thomas (1801): First Inaugural Speech, https://www.ruhr-uni-bochum.de/gna/Quellensammlung/03/03_jeffersoninaugural_1801.htm

Document 2 (Doc 2): Lincoln, Abraham (Doc 2) (1863):Gettysburg Address, Bliss Copy; http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/gettysburg.htm

Document 3 (Doc 3): King, Martin Luther (1963): I have a dream. Speech at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington, D.C., 28.08.1963; https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/mlkihaveadream.htm

Document 4 (Doc 4): Sanders, Bernie (2015): On Democratic Socialism in the US. 19.11.2015; https://web.archive.org/web/20170720220054/https://berniesanders.com/democratic-socialism-in-the-united-states/

Document 5 (Doc 5): Castro, Fidel (1959): What is a Real Democracy? Speech at the July Meeting in the Civic Plaza, Havana, 20.07.1959; https://radicaljournal.com/essays/what_is_a_real_democracy.html

Document 6 (Doc 6): Chavez, Hugo Frias (2005): Opening Address given by the President of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela at the IV Social Dept Summit and Social Charter of the Americas, Caracas 25.02.2005;” https://tellingstoriesofthestoryteller.com/translation-of-chavezs-twenty-first-century-socialism-speech/

Document 7 (Doc 7): Orban, Viktor (2019): Speech at the 30th Bálványos Summer Open University and Student Camp, 27.07.2019; https://visegradpost.com/en/2019/07/29/orbans-full-speech-at-tusvanyos-political-philosophy-upcoming-crisis-and-projects-for-the-next-15-years/

Document 8 (Doc 8): Putin, Vladimir (2005): Annual Address to the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation, Moscow, 25.04.2005; http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/copy/22931

Document 9 (Doc 9): Duterte, Rodrigo Roa (2016): Inaugural Address of his excellency Rodrigo Roa Duterte, President of the Philippines, Rizal Ceremonial Hall, Manila, 30.06.2016; https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2016/06/30/inaugural-address-of-president-rodrigo-roa-duterte-june-30-2016/

Document 10 (Doc 10): Modi, Narendra (2014): Speech at Red Fort on the 68th Independence Day, 15.08.2014; https://www.narendramodi.in/text-of-pms-speech-at-red-fort-6464

Document 11 (Doc 11): Lenin, Vladimir Ilich (1919): Thesis and Report on Bourgeois Democracy and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, First Congress of the Communist International, Moscow, 04.03.1919; https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1919/mar/comintern.htm

Document 12 (Doc 12): Nyerere, Julius (1998): Good Governance for Africa, 13.10.1998; https://www.marxists.org/subject/africa/nyerere/1998/10/13.htm

Document 13 (Doc 13): Lumumba, Patrice (1958): Speech at the Assembly of African Peoples, Accra, 11.12.1958; https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/1958-patrice-lumumba-speech-accra/

Document 14 (Doc 14): Xi, Jinping (2017): Secure a Decisive Victory in Building a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects and Strive for the Great Success of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era. Speech at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, 18.10.2017; https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/19thcpcnationalcongress/2017-11/04/content_34115212.htm

Document 15 (Doc 15): Bolivar, Simón (1819): An Address of Bolivar at the Congress of Angostura, 15.02.1819; https://library.brown.edu/create/modernlatinamerica/chapters/chapter-2-the-colonial-foundations/primary-documents-with-accompanying-discussion-questions/document-3-simon-bolivar-address-at-the-congress-of-angostura-1819/

Document 16 (Doc 16) Mao, Tse-tung (1949): On the People's Democratic Dictatorship. In Commemoration of the Twenty-eighth Anniversary of the Communist Party of China, 30.06.1949; https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-4/mswv4_65.htm

Document 17 (Doc 17): Gandhi, Mahatma (1940): Democracy and Non-Violence. https://www.mkgandhi.org/ebks/political-and-national-life-and-affairs-Vol-1.pdf

Appendix 2: Coding Paradigm Model

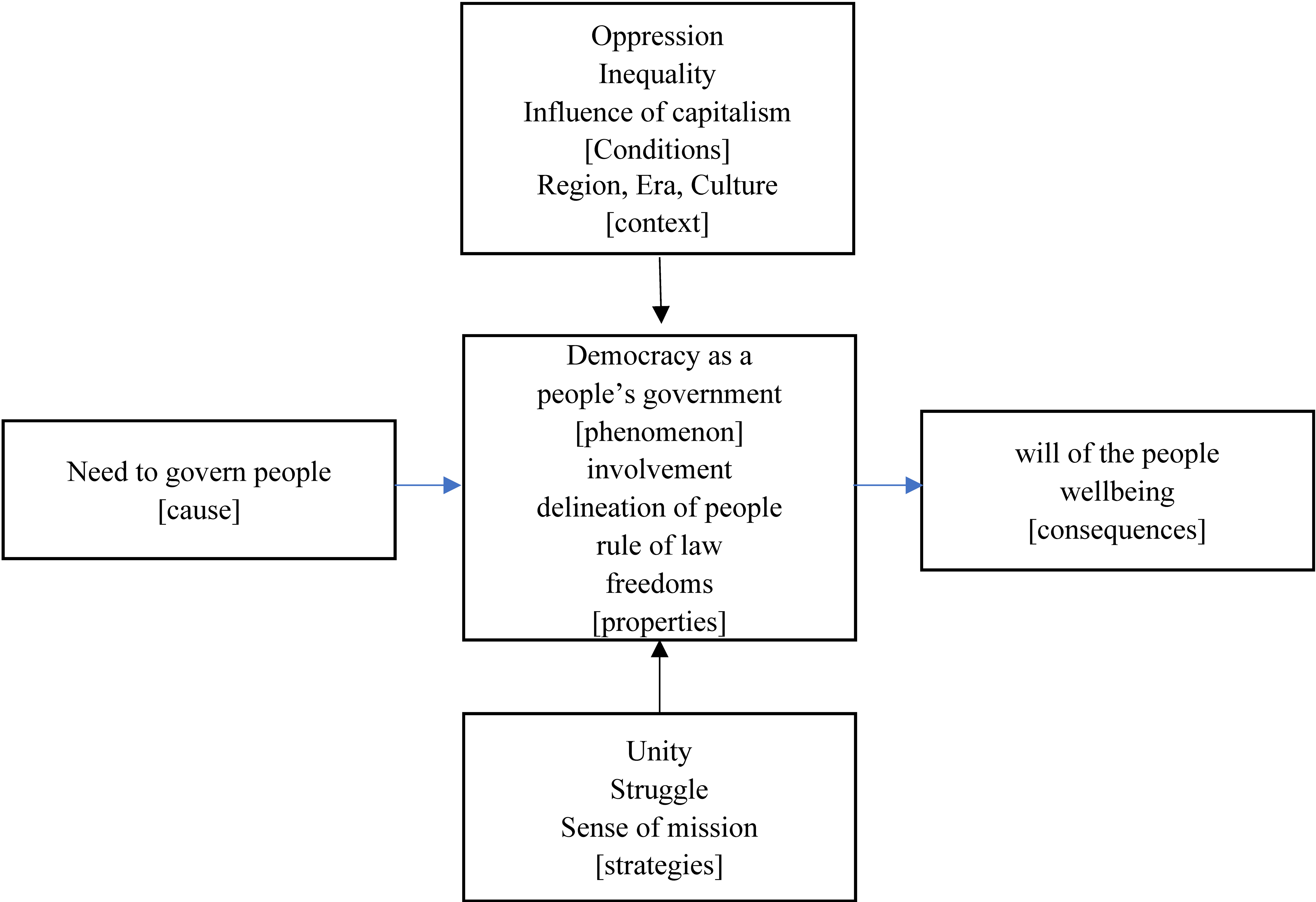

The categories presented in the article were derived by constantly comparing the results of open coding and conceptualizing them on a more abstract level to highlight the aspects in which documents show similarities and differences. The conceptualization is the basis for the next step in Grounded Theory analysis: axial coding and the coding paradigm model. By using the coding paradigm, we aim at linking the categories. If we relate these categories to one another, the result is a grounded theory of democracy that can be presented in a narrative as well as a graphic way. Figure 1 summarizes this very preliminary causal and transactional model of democracy derived from the material analysed in this article.

The core category is “people's government,” which can be further specified along the characteristics of definition of the people, inclusion of the people, freedom, justice, equality and rule of law. As there is a need to regulate the coexistence of the people (cause), democracy as the people's government (phenomenon) is established. Its main feature is the self-government of the people that can be organized in different ways on dimensions of: (a) intensive to extensive involvement of the people, (b) inclusive to exclusive definition of the people, (c) general to exclusive freedoms and rights, and (d) universal to particular rule of law. People's government operates in specific historic, cultural, and social environments (context) and faces challenges as poverty and inequality, corruption, and influence of capitalism (conditions) that have to be dealt with. They can be faced by struggling or even revolution against oppression, by uniting the people and motivating them by evoking a sense of mission (strategy). This results in the fulfilment of the will of the people for achieving a brighter tomorrow and wellbeing (consequence).

Figure 1: