Introduction

Labor returned to government with a narrow single-party majority. The year began with multiple devastating flood events on the Eastern seaboard, raising the salience of the climate emergency in the 2022 Federal election campaign. Politics was dominated by rising inflation, which fuelled the cost-of-living crisis, saw interest rates rise and compounded the impacts of soaring energy costs—the result of a decade of policy drift. Australia sent more than AUD $650 million in military aid to Ukraine. The Albanese government undertook a major foreign policy reset in the Pacific and with China (Simons Reference Simons2022).

Election report

Parliamentary elections

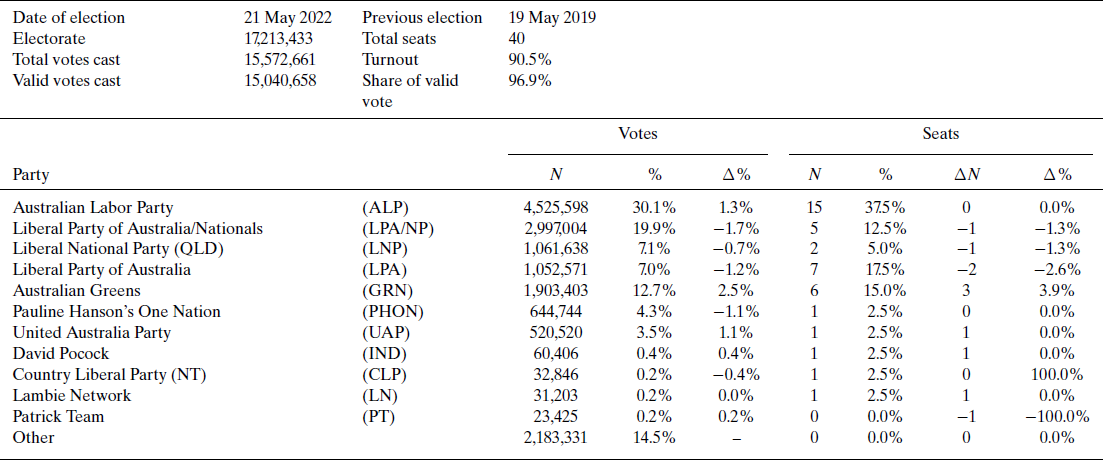

The federal election was held on 21 May 2022 (see Tables 1 and 2). The Australian Labor Party (ALP) won 77 (32.6 per cent) of 151 seats and formed a narrow single-party majority government. The Coalition, comprising the Liberal Party of Australia (LPA), The National Party (NP) and the Liberal National Party (LNP, Queensland [QLD] only) endured their worst-ever result (35.7 per cent), winning only 58 seats (LPA: 27, NP: 10 and LNP: 21). The remaining seats were divided amongst an expanded cross-bench of Greens (4), Independents (10) and micro parties (2). The 2022 poll represented the lowest-ever primary vote shares of both the ALP and the Coalition, indicative of the ongoing decline in levels of party identification (see Cameron & McAllister Reference Cameron and McAllister2022, for further trends).

Table 1. Elections to the lower house of the Parliament (House of Representatives) in Australia in 2022

Notes:

1. The incumbent government grouping is called ‘The Coalition’, made up of the LPA, LNP, NP and the CLP.

2. The LNP Party is the merger of the Queensland divisions of the LPA and the NP. Members choose to sit in either the NP or LPA party rooms in the Federal Party.

3. The CLP only exists in the Northern Territory. Members sit with the Liberal Party in the Federal Parliament.

Source: Australian Electoral Commission website (2022).

Table 2. Elections to the upper house of the Parliament (Senate—Half) in Australia in 2022

Notes:

1. In total, the Senate has 76 seats.

2. Percentages about votes are calculated as percentages of half Senate results, not for the whole chamber.

3. The Liberal Party of Australia and National Parties run a joint Senate ticket in NSW and Victoria.

4. The LNP Party is the merger of the Queensland divisions of the LPA and the NP. Members choose to sit in either the NP or LPA party rooms in the Federal Party.

5. The LPA ran separately in WA, SA, Tas and the ACT. The NP ran separately in South Australia and it is not reported here (received <1% of the national vote).

Source: Australian Electoral Commission website (2022).

The election campaign was fragmented, aside from the debate about Scott Morrison's (un)popularity, character and leadership efficacy and the quality of substantive (sex, race and city/country) representation. Instead, two campaigns emerged, one focused on women's representation, the climate emergency and integrity in politics, and a more traditional contest about the economy, focused on wage stagnation, inflation, housing affordability and economic management. The campaign was highly gendered, with Labor emphasising their reform agenda for the care economy and the Coalition emphasising national security and the ‘traditional’ male-dominated economy (construction, trades and resources). Discussion of COVID-19 was largely absent but was an essential background for a campaign where events appeared to conspire against the government, underscoring how previous strengths in national security and the economy had been undermined after nine years of office.

Turnout was high in all states (ranging between 88 per cent and 92.4 per cent), with the exception of the Northern Territory (NT) where only 73.1 per cent cast a ballot. The NT has significant numbers of remote communities.

In the Senate, the Coalition collectively lost four seats, three of which were picked up by the Greens and one by an Independent. The United Australia Party (UAP) returned to the Senate. The result saw the Senate shift ideologically leftwards, giving the incoming Labor government greater scope to form coalitions to pass its legislation.

Regional elections

The Liberal South Australian government lost the 19 March 2022 election after only a single term. Labor won 27 (40.0 per cent) of the 47 seats to the Liberal's 16 seats (35.7 per cent), with Independents taking the remaining four (7.3 per cent). The Greens received 9.2 per cent of the vote but no seats. This was the first government to lose an election since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The result was a shock nationally (but not locally) and added to media speculation that the Federal Morrison government would lose office.

In Victoria, Daniel Andrews’ government was re-elected for a third term. Labor won 56 seats but only 36.6 per cent of the vote. The Liberals won 34.5 per cent, but only 27 seats, and the Greens translated their 11.5 per cent into three seats. Labor's victory, despite the unpopularity of its draconian COVID-19 measures, highlighted the dire state of the Liberal opposition. Labor suffered a 6.2 per cent swing.

Cabinet report

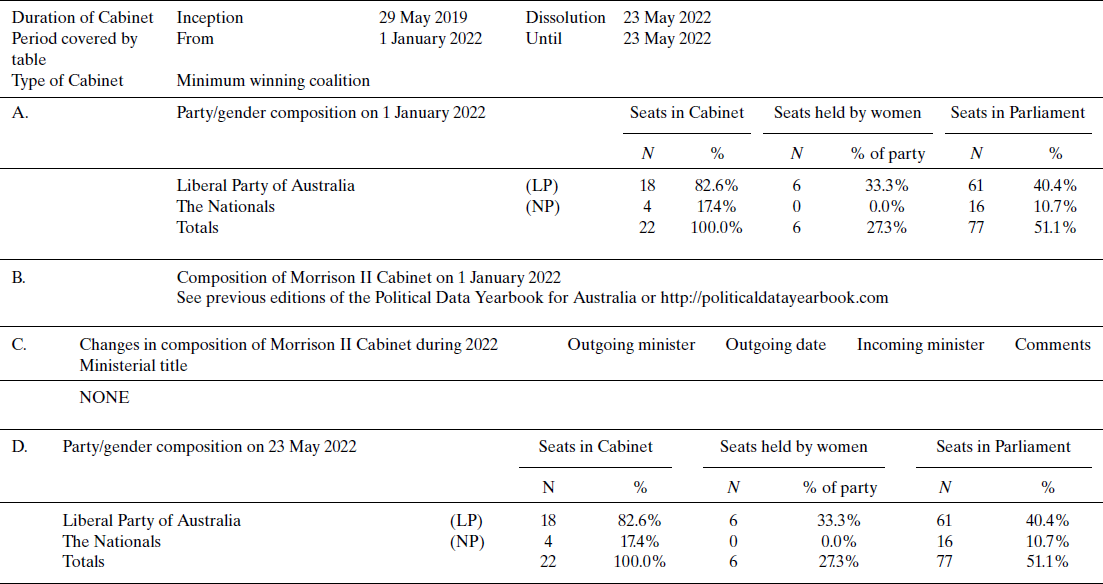

There were no changes to the Morrison II ministry (Table 3).

Table 3. Cabinet composition of Morrison II in Australia in 2022

Sources: Australian Parliamentary Handbook (2023); Current Ministry List (2023) (www.aph.gov.au/about_parliament/parliamentary_departments/parliamentary_library/parliamentary_handbook/current_ministry_list).

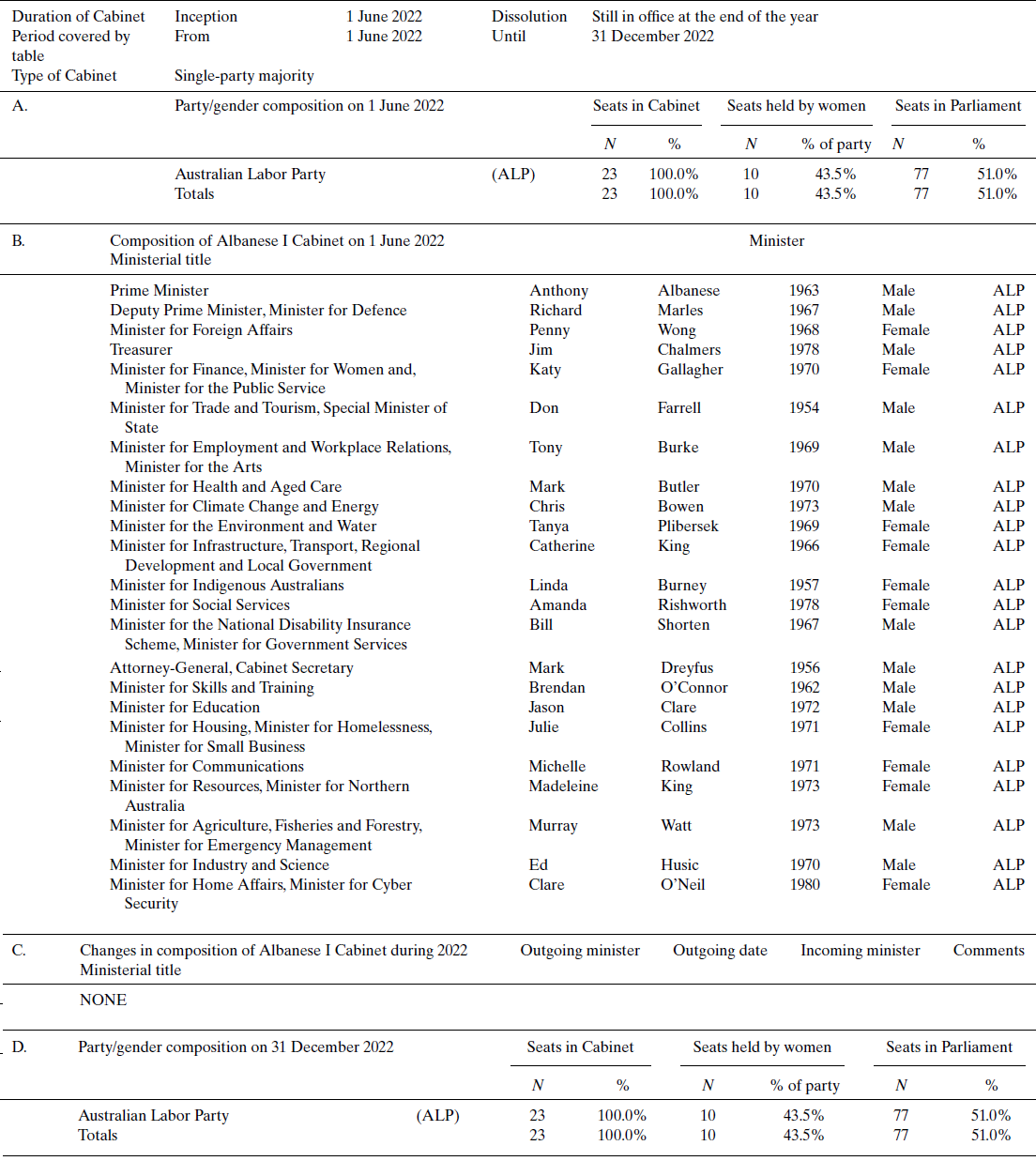

After the federal election, the incoming Labor government formed a single-party majority Cabinet with Anthony Albanese as Prime Minister (Table 4). Women held 10 of the 23 Cabinet positions (43.5 per cent), which is the highest ever for Australia. However, women were more likely to be lower down the Cabinet ranking. This is in part driven by age (younger on average). There were no changes to the Albanese I Cabinet in 2022.

Table 4. Cabinet composition of Albanese I in Australia in 2022

Note: There was technically an interim ministry of the most senior Cabinet that existed before they swore in the full group that last for a week.

Sources: Australian Parliamentary Handbook (2023); Current Ministry List (2023) (www.aph.gov.au/about_parliament/parliamentary_departments/parliamentary_library/parliamentary_handbook/current_ministry_list).

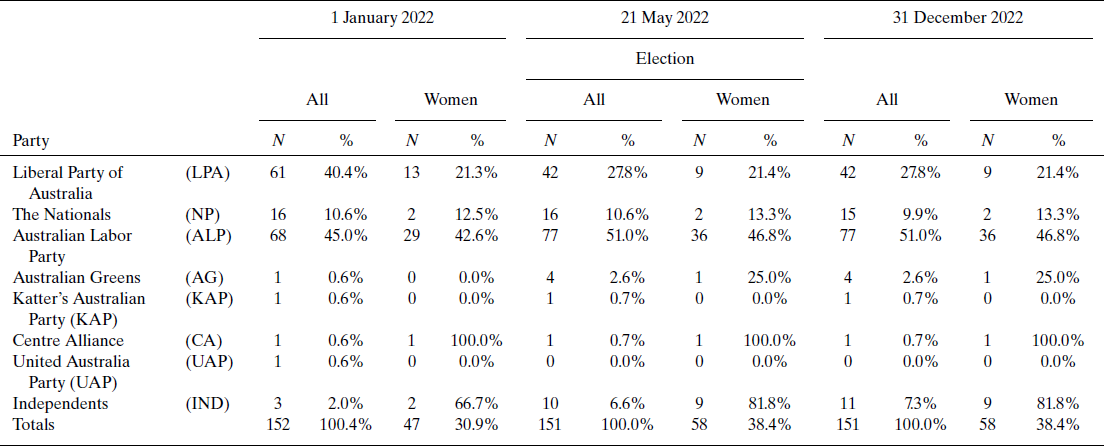

Parliament report

The composition of the Parliament changed as a result of the 2022 election. Collectively, women hold 101 of the 227 positions in both chambers and now make up 44.5 per cent of the Australian Parliament. Women's representation is greater in ideologically left parties and in the upper chamber, which uses a party list system in combination with the single transferable vote. The 47th Parliament was declared to be ‘Australia's most diverse’, but non-White Australians remain under-represented (Clure Reference Clure2022).

In the lower house, the Coalition lost seats to Labor, the Greens and a wave of ‘Teal’ independents (pro-environment ‘L’ and ‘l’ Liberals). The crossbench increased to 17 by year's end. Women finally make up more than one-third of elected MPs (38.4 per cent) in the lower chamber. This result was driven by an increase in ALP women and a large influx of female Independents. Women's representation amongst the Coalition remained virtually unchanged—with Coalition women making up one-fifth of their joint-party room and only 7.3 per cent of the Parliament (Table 5).

Table 5. Party and gender composition of the lower house of the Parliament (House of Representatives) in Australia in 2022

Notes:

1. Andrew Gee quit the NP on 23 December 2022 and now sits as an Independent.

2. George Christensen defected from the LNP to PHON on 13 April 2022. He declared he would run for PHON in the Senate race at the 2022 election. He was not elected.

Sources: Australian Parliamentary Handbook (2023) (www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp2223/Quick_Guides/CompositionPartyGenderJan23); Australian Parliamentary Library, ‘Gender Composition in Australian Parliaments by Party and Chamber’ (2023) (www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp2223/Quick_Guides/CompositionPartyGenderJan23).

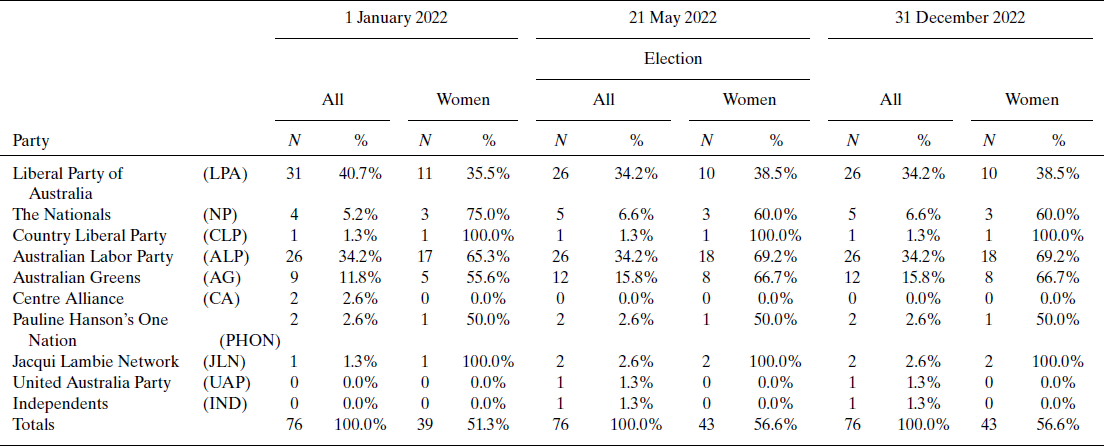

Women consolidated their majority status in the Senate (56.6 per cent), as a result of Labor and the Greens. Women's representation amongst the Coalition parties went backwards. The Coalition lost seats to the Greens and Independents, shifting the overall ideological balance of the Senate leftward (Table 6).

Table 6. Party and gender composition of the lower house of the Parliament (Senate) in Australia in 2022

Notes:

1. LNP members have been counted as part of either the LPA or the NP according to which party room they sit in.

2. After the 2022 election, the CLP Senator now sits in the NP party room.

3. Centre Alliance member Rex Patrick ran as an Independent ticket during the 2022 election campaign (see Table 1).

Sources: Australian Parliamentary Handbook (2023) (www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp2223/Quick_Guides/CompositionPartyGenderJan23); Australian Parliamentary Library, ‘Gender Composition in Australian Parliaments by Party and Chamber’ (2023) (www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp2223/Quick_Guides/CompositionPartyGenderJan23).

In August, it emerged that former PM, Scott Morrison, had sworn himself into five ministries (Health; Finance; Industry, Science, Energy and Resources; Home Affairs; and Treasury) during the course of the pandemic, in violation of the Westminster principle of ‘responsible government’. In the case of the latter two, he did not inform the relevant ministers or departments that he had done so. Additionally, Morrison had himself sworn into the Energy and Resources ministry in order to override approval of an unpopular exploration licence in the lead-up to the 2022 election (Martin Reference Martin2022). The Albanese government called an inquiry, which recommend stronger codification and transparency (Bell Reference Bell2022). The Albanese government accepted all of the recommendations.

In November, Labor passed legislation to establish a National Anti-Corruption Commission (NAAC) (Attorney-General's Department 2022), fulling its election promise. Labor's NAAC model was seen as a significant improvement on the Commonwealth Integrity Commission proposed by the Morrison government, which did not envisage that politicians or their staff could be investigated. However, the NAAC was criticised by experts and minor parties for only allowing hearings in the vaguely defined ‘exceptional circumstances’. The minor parties succeeded in forcing the government to require one non-government member to approve the selection of the NAAC's commissioner. The commission will come into operation on 1 July 2023 and will have the power to investigate retrospectively.

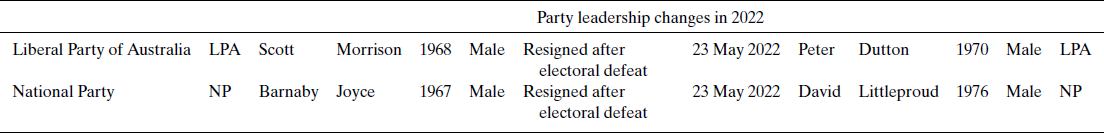

Political party report

Changes in political parties are reported in Table 7. Scott Morrison (New South Wales [NSW]), Centre-right faction) resigned as leader of the LPA on election night and was replaced by factional rival Peter Dutton (QLD, Right). Dutton became de facto leader of the Liberal-National Coalition. Barnaby Joyce (NSW), leader of the NP, resigned after the election and was replaced by David Littleproud (QLD). The election result was devastating for the metropolitan-based Left/Moderate grouping of the LPA. The LPA is now dominated by the QLD-based LNP, which means Conservative (Right/Centre-right) and regional and rural perspectives dominate both the LPA and joint party rooms.

Table 7. Changes in political parties in Australia in 2022

Source: Australian Parliamentary Handbook (2023).

Institutional change report

Australia got a new head of state, King Charles III, after the death of his mother, Queen Elizabeth II, on 22 September.

In early 2022, the Morrison government established the leadership task force to implement recommendations from the Set the Standard report, which investigated harassment and abuse within Australia's parliamentary culture (see Taflaga Reference Taflaga2022). As a result, the Parliamentary Workplace Support Service was expanded in April 2022, which provided previously unavailable independent dispute resolutions services for political advisers and other parliamentary workers. Upon election, Labor accelerated the implementation process, agreeing in principle to all of the recommendations. By year's end, changes were made to the Members of Parliament (Staff) Act 1984 (Cth), clarifying the duties owed to staff by parliamentarians and requiring parliamentarians to give reasons for terminating staff employment. Changes were also made to the order of business in both chambers to facilitate more family-friendly working hours and better work–life balance. The remaining recommendations for implementation include commitments to expanding diversity (including measurement and public reporting); best-practice human resource training for parliamentarians and bureaucrats; an ‘everyday respect’ inquiry to the standing orders and unwritten conventions of Parliament; the adoption of a behaviour standards code for parliamentarians, staff and commonwealth workers; and the establishment of an Office of Parliamentary staffing and Culture, which would be governed under the auspices of an Independent Parliamentary Standards Commission (Parliamentary Leadership Taskforce 2023). The bulk of recommendations are due to be implemented in 2023.

Issues in national politics

Aside from the election, the growing inflation crisis dominated Australian politics. By year's end, inflation was running at over 7 per cent, reflecting high and rapidly increasing prices for everyday essentials, energy and housing (rents and purchases). In response, the Reserve Bank increased interest rates by 3 per cent during 2022.

Insecure supplies of gas and sky-rocketing energy prices forced the government to suspend the national energy market to prevent power blackouts during the winter. The crisis was the result of Australia's inability to settle on a coherent climate policy, which resulted in policy drift and a failure to offer the industry a clear set of incentives and regulations to manage the long-term transition to renewable energy sources (Ludlow Reference Ludlow2022).

On election night, Prime Minister Albanese committed his government to hold a referendum in 2023 to enshrine an Indigenous Voice to Parliament and the executive in the constitution. This would be the first referendum since Australia voted against becoming a republic in 1999.

In late September, Australia abandoned its mandatory COVID-19 requirements and the accompanying government payments, ending the era of strong enforcement of public health policies (Butler & Remeikis Reference Butler and Remeikis2022).

The year ended with the government legislating the ‘Respect at Work’ Bill, which creates a positive duty on employers to create safe workplaces and proactively implement measures to prevent sexual harassment, discrimination and abuse. The Bill also grants the Australian Human Rights Commission new regulatory powers to undertake investigations and bring legal action against organisations and individuals (Australian Human Rights Commission 2022).

Acknowledgements

Open access publishing facilitated by Australian National University, as part of the Wiley - Australian National University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.