Introduction

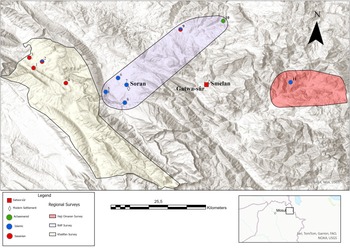

The site of Gatwa-sûr (UTM WGS84 36°40′31.97″N, 44°43′56.04″E) is located in a mountainous area between the modern villages of Mawan and Smelan, within Mawan municipality, 500 meters south of the village of Smelan (Choman district, Erbil province, Kurdistan region of Iraq). The site is situated fifteen kilometers to the west of the present-day Iranian border and seventeen kilometers to the east of the city of Soran (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Map showing Gatwa-sûr’s location, the extent of the surveys described in the text, and other relevant archaeological sites

The toponymy of the site is derived from the Kurdish term for “red blackberry”. This term is also employed to refer to the entire region, which is characterized by the presence of high peaks and valleys. The topography is composed of limited pastureland, which is primarily used for animal husbandry, constituting the region’s predominant economic activity. The landscape is irrigated by numerous streams that flow into the Balakian River, ensuring a consistent supply of fresh water throughout the year (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Terrain and environment of the site of Gatwa-sûr

In the 1990s, the owner of a rural property discovered an ancient tomb on the northern summit of a mountain while clearing the land to flatten it for the construction of a hut. The northern section of the tomb was unearthed, consisting of a single ceramic coffin buried two meters below the current surface. Following the discovery, the burial was disturbed by removing the skull and some bones from the upper part of the postcranium, which were subsequently reburied in an undisclosed location. The exposed portion of the coffin was covered with plastic fabric, and the new hut was built over it. Thirty years later, the owner opted to report the discovery, prompting Abdulwahab Suliman, Director of the Soran Directorate of Antiquities, to conduct a rescue excavation in collaboration with the Research Group SAPPO-GRAMPO (Grup de Recerca Arqueològica de la Mediterrània i del Pròxim Orient - Seminari d’Arqueologia Prehistòrica del Pròxim Orient) from the Autonomous University of Barcelona. A stratigraphic analysis was conducted, revealing damage to the northern part of the coffin, attributable to the substantial weight of the hut’s walls situated above it. During the fieldwork, some remnants of the hut were still standing, along with the modern embankment that had been dug thirty years prior.

From the outset of the excavation, the burial exhibited clear Christian characteristics. A fragmentary ceramic cross pattée, discovered during site cleaning, in addition to another cross carved on the coffin, indicated a Christian affiliation. Of particular significance is the ceramic cross’s original placement atop the coffin lid, directly above the deceased’s head, as evidenced by the marks of the cross’s base on the coffin’s surface.

This paper aims to underscore the significance of this discovery through a thorough survey of archaeological and textual sources, performing an archaeothanatological analysis that includes the study of the earthenware coffin and its religious symbolism. Additionally, an anthropological analysis to determine the age, sex, stature and health of the buried individual has been conducted. The significance of Gatwa-sûr’s first archaeological remains lies in the novel and compelling insights they offer into the early Christian population in the region during Late Antiquity.

Archaeological and Textual Sources about Early Christianity in the Region

The mountainous area of Soran province, northeast of the Erbil governorate, has received scant attention from archaeologists. In 2014, a team from the University of Pennsylvania, led by Dr. Michael Danti, initiated an investigation project in the Delizan plain, near Soran city and only twenty kilometers west of Gatwa-sûr, as well as in areas further north. In the plain, the team conducted excavations at the multiperiod mound of Girda Dasht and undertook rescue excavations at several locations, including the Neolithic site of Gird Banahilk. Further north, along the Balakian River, the team conducted rescue excavations at sites ranging from the Iron Age to the late Achaemenid period. Our research group, the SAPPO-GRAMPO team from the Autonomous University of Barcelona, has also conducted research programs at two sites in the region: the aforementioned Gird Banahilk and a group of caves called Gal-î Çinaran, located near Soran city. In addition, in 2017, a survey was conducted by the same team in which up to twenty-four archaeological sites were recorded (Molist et al. Reference Molist, Bach Gómez, Zibare, Abdullrahman, Bradosty, Soleiman, Montero Fenollós and Brage Martínez2021). The province of Khalifan, to the west of the province of Soran, has also been surveyed in recent times (Beuger et al. Reference Beuger, Helms, Suleiman, Dlshad and Hussein2015; Reference Beuger, Heitmann, Schlüter, Schulz, Suleiman, Dlshad, Rashid and Hussein2018) . This survey is especially relevant because specific research on the Christian population spread throughout the region has been published (Beuger Reference Beuger, Kaniuth, Lau and Wicke2018).

The mountainous region east of the Delizan plain has received even less attention than the plain itself. The archaeological landscape surrounding Gatwa-sûr remains under-explored, yet it is evident that the discovery of a solitary tomb of this nature cannot be regarded as an isolated find. It is reasonable to assume that this tomb was part of a larger necropolis, a hypothesis that is supported by the discovery of other ancient objects in the area. This assertion is further substantiated by the account of the landowner’s sons, who reported the discovery of a metal sword in the vicinity of the site many years prior. Unfortunately, this sword has since gone missing. Additionally, pottery fragments were found scattered on the surface near the tomb; however, due to limitations of time, a more thorough survey could not be conducted. Beyond the area of the site of Gatwa-sûr, there are reports of rock reliefs in the region dating back to the Sasanian period (A. Suliman, personal communication, 2023). While the possibility that this site could be part of a necropolis has been considered, there is currently no evidence of any ancient settlement or religious site associated with the burial ground. It is noteworthy that the absence of related settlements has been documented in other Late Antique cemeteries investigated in Northern Iraq and other regions of Mesopotamia and Iran, such as the Sasanian levels at Gird-î Bazar (Squitieri Reference Squitieri2020), Tell Mohammad Arab (Roaf Reference Roaf1984), and Umm Kheshm (Ball and Black Reference Ball and Black1987), suggesting that isolated cemeteries were common in this period.

Archaeological discoveries in the Delizan plain have revealed evidence of both Late Antique and Islamic eras. A notable site is Girda Dasht, where a complete Islamic sequence extending up to the Soran Caliphate has been documented. In addition, the same research team documented late Achaemenid and Sasanian remains in the modern city of Sidekan (Danti Reference Danti2014).

Recent years have seen a growth in research on the introduction and spread of Christianity in Southwest Asia. According to the Christian tradition, the introduction of Christianity in Mesopotamia is attributed to the Apostles and disciples of Jesus Christ. According to sources such as the Acts of Thomas, a text dating to the third century C.E., the Apostle Thomas was sent as a missionary to India (Moffet Reference Moffet1992). Saint Thomas, also known as Mar Thoma, sent one of his disciples, Addai (also referred to as Mar Addai), to preach in the Mesopotamian lands (Baumer Reference Baumer2016). The expansion of Christian communities continued with the rise of the Sasanian Empire, reaching such a degree of consolidation that in 410 C.E., the ruler Yazdgird I established the Church of the East as an ecclesiastical entity to disassociate from Roman Christianity. This decision enabled the monarch to exert control over the Christian bishops, who gained significant political influence in the territory (Payne Reference Payne2015). The monarch’s decision further underscores the presence of prominent Christian communities that underwent rapid expansion throughout the vast empire (Hauser Reference Hauser, Pettegrew, Caraher and Davis2019). The dissemination of Christianity across the Sasanian monarchy during the Late Sasanian Period (sixth to seventh centuries C.E.) is evidenced by the ruler Khosrow II, who married two Christian wives (one of whom, Queen Shirin, was an active member of the Christian community), constructed numerous churches, and sponsored the construction of many more (Baum Reference Baum2004; Payne Reference Payne2015). Alongside the Church of the East, several other religious faiths coexisted in the territory: Zoroastrianism, Christianity of various doctrines (monophysitism, miaphysitism, and dyophysitism) and rites (melkites and East Syriac Christians), and Judaism (with numerous community members in the region of Assyria).

The presence of Christianity in Northern Iraq has been substantiated by written sources and archaeological evidence. The establishment of bishoprics and churches remains a subject of debate among researchers, however, as only secondary written sources have survived. The earliest extant written sources were compiled at least three centuries after the alleged events, prompting researchers to debate whether the creation of these documents was for the purpose of legitimising the Christian tradition by establishing the foundation of ecclesiastical districts and religious buildings at the earliest possible chronology (Hauser Reference Hauser, Kaniuth, Lau and Wicke2018; Jullien and Jullien Reference Jullien and Jullien2002). However, the existence of a reliable archaeological record, comprising religious structures and associated artifacts, offers substantial and verifiable evidence of Christian presence in the territory (Morony Reference Morony1984; Muhamad Amen Ali Reference Muhamad Amen Ali2009; Payne Reference Payne2015; Venco-Ricciardi Reference Venco-Ricciardi, Genito and Caterina2017).

One of the most noteworthy written sources about early Christianity in the region is the Chronicle of Arbela (Anonymous 1985), which was written in the sixth century C.E. Arbela, the modern-day city of Erbil, was the capital of the kingdom of Adiabene, a region situated between the Great and Little Zab rivers that existed from the second century B.C.E. to the fourth century C.E. (Brock Reference Brock1982; Squitieri Reference Squitieri2020). The text describes the existence of twenty bishoprics in Arbela prior to the overthrow of the Arsacid dynasty during the Late Parthian period (Hauser Reference Hauser, Pettegrew, Caraher and Davis2019). The first documented bishop, ordained by Addai himself, was Peqida of Arbela (104–114 C.E.) (Anonymous 1985). The cities of Arbela and Karka de Beth Selok (the modern-day city of Kirkuk), which already had bishops in the second century C.E., were designated as ‘metropolitanates’ of the Church of the East in the Sasanian era, thus indicating that northern Mesopotamia was a major center of Christianity in this period (Dauvillier Reference Dauvillier and Enciso Viana1948; Morony Reference Morony1984; Payne Reference Payne2015; Winkler Reference Winkler2003). Another potential early Christian community may have existed in the city of Hatra, likely settling after the city’s abandonment following its destruction by the Sasanian ruler Shapur I in 241 C.E. (Roaf Reference Roaf1984). In the city of Nineveh, the presence of bishops from the Church of the East has been attested since the fifth century C.E., indicating the presence of a prominent Christian community, so significant that they were considered the predominant group in the city during Late Antiquity (Simpson Reference Simpson2005). Many monasteries were established in the kingdom of Adiabene, one example being the Mar Mattai monastery, founded in 363 C.E. and located twenty kilometers northeast of Mosul. A substantial number of churches were constructed, with two notable examples located in Qasr Serij (south of Gebel al-Qusayr, approximately sixty kilometers northwest of the modern city of Mosul) (Oates Reference Oates1962) and in Tell Kuyunjik/Nineveh (Simpson Reference Simpson, Peruzzetto, Metzge and Dirven2013), both established in the final decades of the sixth century C.E. During the Islamic Period, more churches were founded, such as one located at the site of Khirbet Deir Situn, in the Eski-Mosul dam area. During the excavation of this building, up to 140 pottery sherds stamped with Sasanian seals (some with crosses), were unearthed (Curtis Reference Curtis1997).

The expansion of Christianity from the Sasanid Empire to East Asia was characterized by the establishment of monastic preparation schools, first in Edessa and later in Nisibis, with the objective of training and equipping monks as missionaries. The existence of the Silk Trade Route facilitated travel to East Asia, thereby enabling the dissemination of the Christian faith, which reached as far as China by the end of the Sasanian period in 635 C.E. (Fairbairn Reference Fairbairn2021; Nicolini-Zani Reference Nicolini-Zani2022). Archaeological remains discovered in Central Asia provide material evidence for Christian presence along the Silk Route. Of particular significance are the necropolis linked to a monastic complex recently reported at the site of Urgut, in Uzbekistan, dated to the seventh–twelfth centuries C.E. (Ashurov Reference Ashurov2019; Gilbert Reference Gilbert, Tang and Winkler2022, Reference Gilbert2024; Savchenko Reference Savchenko2023) and the site of Ilibalyk in southeast Kazakhstan, dated to the twelfth –fourteenth centuries C.E. (Gilbert Reference Gilbert, Tang and Winkler2022; Voyakin et al. Reference Voyakin, Gilbert and Stewart2020). Other notable cemeteries include Kara-Jigach and Tokmok, located in Kyrgyzstan and dated to the nineteenth century C.E. (Kolchenko Reference Kolchenko and Voyakin2018; Myakisheva Reference Myakisheva2021; Pantusov Reference Pantusov1886). The dissemination of Christianity in China began in the seventh century C.E., during the Tang dynasty (Nicolini-Zani Reference Nicolini-Zani2022). The so-called stele of Xi’an, discovered in this former Chinese capital and dated to 781 C.E., provides the earliest evidence of the arrival of a group of missionaries sent by Ishoyahb II, the patriarch of Adiabene from 628 to 645 C.E., to China in 635 C.E. Ishoyahb II, since he also founded additional “metropolitanates” in Hulwan (Iran), Herat (Afghanistan), Samarkand (Uzbekistan), Xi’an and India, enabled the arrival of further missionaries (Baum and Winkler Reference Winkler2003).

Fieldwork at Gatwa-sûr

The fieldwork at Gatwa-sûr was conducted over the course of two days. Upon arrival at the site, the archaeological team discovered a trench that had been previously excavated into the hillside, measuring 2 x 2 meters. A total of fifteen fragments of an earthenware coffin and its lid were previously uncovered, displaying clear indications of disturbance due to soil pressure and the construction of the modern hut. Notably, only a single piece of the coffin was found in situ, belonging to the coffin’s northwestern part. Subsequent to the removal of the disturbed fragments, it was observed that the coffin extended into the southern part of the trench. Consequently, we decided to extend the trench to the south by an additional meter.

The first stratigraphic unit, comprising a surface layer of unaltered soil from the hillside, was excavated and had no archaeological remains. The sediment was taphonomically naturally deposited, as no anthropic activity was evidenced during its excavation. Under the surface layer, two different stratigraphic units were observed: the first, located to the east of the coffin, was characterized by compact, brown-colored clay, containing simple oxidized pottery fragments and animal bone fragments. The second was located immediately above the coffin lid, extending to the west. The layer above the lid was thin, while the western part had an approximate depth of forty-five centimeters. This layer was characterized by the presence of black, compact clay, rich in charcoal remains. A sample of the charcoal was collected for further analysis. The absence of evidence suggesting the presence of a pit or a shaft that had cut through the stratigraphic units in order to accommodate the coffin indicates that modern disturbances have not altered the remains of the southern part of the coffin. However, the potential existence of other structures, either subterranean or above ground, cannot be ruled out, though the remains were insufficient to undertake any hypothetical reconstruction.

Upon reaching the coffin, the excavation process of the burial was documented (Fig. 3), the coffin was outlined, and its parts were measured. The upper part of the coffin was found at a depth of 1.46 meters, while the lower part was 1.89 meters below the current surface level. Subsequently, the lid was removed, of which half was in situ and the other half was found collapsed inside the tomb. The soil covering the deceased was also removed. The first layer of sediment within the coffin was soft, while the second layer was harder and comprised clay. Within the sediment, we found small fragments of the upper part of the deceased’s body, particularly the skull and ribs. Following the complete exposure of the human remains, an anthropological analysis was performed, including bone identification, siding, measurement, age, and sex assessment. Thereafter, the bones were collected for further detailed analysis in the laboratory. Finally, the arrangement of the coffin parts was documented, and the coffin itself was removed for reassembly and future display at the Archaeological Museum of Soran.

Fig. 3. The excavation process of the coffin. a) The lower part of the lid in situ while the upper part has collapsed and been disturbed. b) The lower in situ part of the lid removed, revealing a large fragment of the left rim that collapsed inside the coffin. c) Disarticulated bones appearing once almost all the lid is removed. d) Exposed bones of the individual, some loosely articulated, but most disarticulated. e) Coffin without the individual

Archaeothanatological Analysis

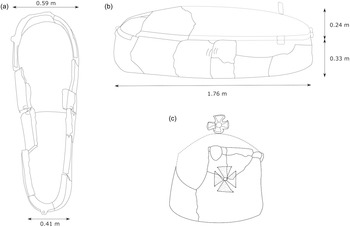

The coffin measures 1.76 meters in length and has an oval shape, with a wider northern part measuring 59 cm in width and a narrower southern part measuring 41cm in width (Fig. 4a). The morphology of the coffin corresponds to the measurements of a human body in an extended position, with the northern part wider to accommodate the shoulders, and the southern part narrower to fit the legs of the individual. The coffin, made of thick oxidized clay of a bright orange color, comprises two different parts: the lid, measuring 24 cm in height, with a vaulted morphology; and the coffin, measuring 33 cm in height (Fig. 4b). Both the coffin and the lid have a rim that enables them to fit together, accompanied by six handles (one positioned on the northern side, one on the southern side, two next to each other on the eastern side, and two next to each other on the western side of the coffin) for the insertion of a string, thereby securing the lid to the coffin.

Fig. 4. Drawing of the coffin. a) Upper view of the coffin, with width measurements of the northern (widest) and southern (narrowest) parts. b) Right side view of the coffin. Dashed lines reconstruct the collapsed parts of the coffin and the vaulted lid. c) Wider end of the coffin with appliqué of a cross pattée on the lid and incised cross pattée on the coffin

The coffin was constructed from two halves; the paired side handles each had a hole to tie the halves together. The coffin may have been made in two large pieces due to the size of the kiln (the entire coffin might not fit into the kiln) and to facilitate transportation (two pieces are easier to move from the workshop to the burial site than one large and heavy piece). However, the evidence does not support the hypothesis that the lid was made in two pieces. The coffin exhibited a roughly smoothed surface, without glaze, and some manufacturing marks are visible, particularly on the interior surface of the lid.

Atop the northern part of the coffin lid, there was a cross pattée with a circle in the middle as an appliqué, attached to the vaulted lid. Additionally, the northern part of the coffin itself is decorated with an incised cross pattée with an irregular dot pattern and a circle in the middle (Fig. 4c).

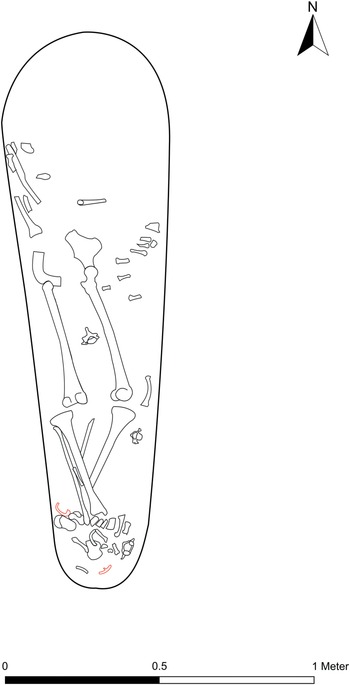

The burial consists of the inhumation of a single individual in primary deposition inside the ceramic coffin. The deceased was oriented in a north-south direction and was lying in an extended position. The type of posture remains ambiguous due to the disturbance of the bones; however, it may have been either supine or lateral. The position of the arms remains indeterminate, and the legs were crossed at the level of the feet. The remaining bones are displaced or disarticulated, a consequence of ancient and modern disturbances.

Two metallic objects were found on the lateral part of the tarsals. Their morphology suggests that they were part of the deceased’s footwear and could be interpreted as part of buckles (Fig. 5). The absence of any additional ornaments or offerings can be attributed to their non-existence or to looting during both ancient and modern times.

Fig. 5. Metallic objects interpreted as footwear buckles

In order to accurately reconstruct the burial practice of this inhumation, it is necessary to consider the available evidence. The landowners of Gatwa-sûr have stated that, upon first discovering the coffin, they removed the skull and some bones from the upper part of the body. These remains have not been recovered to date. The lower parts of the deceased’s body were found in a more or less loose anatomical connection, while the upper part of the body was completely disturbed and disarticulated. The axis and atlas vertebrae, which connect the skull to the spine, were found at the feet of the deceased instead of in their expected location. Additionally, some fingers and thoracic vertebrae were found below the level of the os coxae. All of these bones were significantly distant from their anatomical position (Fig. 6). The burial also appears to have been opened in ancient times, before the coffin was filled with soil. After the skeletonization of the deceased, the vaulted lid was opened, and many of the bones were displaced throughout the container. It is plausible that any valuable objects originally present within the burial were looted during this period. A subsequent disturbance, involving the removal of the majority of the skull and the upper part of the body, occurred in the 1990s during the construction of the nearby hut.

Fig. 6. Drawing of the deceased showing anatomical connections, position, and orientation

No clear traces of a pit or any other burial feature were found at the site. The sole noteworthy find was the presence of a large stone slab, measuring 65 cm in height, 1 meter in length, and 25 cm in width. This slab appeared in proximity to the coffin, at a higher point, though it did not completely cover the coffin. It is not clear if this stone was part of a former covering, such as a roofed subterranean space, or a natural element. Additionally, the preserved stratigraphy in the section covering the southwestern part of the coffin, between the coffin and the stone slab, exhibited the presence of black layers with charcoal inclusions. However, these layers were not related to the primary deposition of the burial.

Chronology of the Burial: Radiocarbon Dating and Parallels

In order to determine an absolute date for the burial, a sample from the left tibia was collected during the excavation and subsequently subjected to radiocarbon dating. The sample (Beta-684933) yielded a date of 1550 ± 30 B.P. Calibration was conducted in accordance with the IntCal20 calibration curves published by Reimer et al. (Reference Reimer, Austin, Bard, Bayliss, Blackwell, Ramsey and Butzin2020), yielding an equivalent date of 430–587 cal. C.E. (2σ probability), encompassing the Mid to Late Sasanian period.

Further analysis revealed the presence of parallels from Late Antiquity related to the morphology and the decorative motifs of the coffin. Excavations in Northern Iraq have revealed Sasanian cemeteries at several sites, including Gird-î Bazar (Squitieri Reference Squitieri2020), Tell Mohammad Arab (Roaf Reference Roaf1984), and Tell Mahuz (Negro-Ponzi Reference Negro-Ponzi1968–69). The burial types at these sites possess significant variability. The first two cemeteries consist of pit graves, without coffins, which could be delimited by stones and covered by flat capstones (only occasionally in the second case). However, at the site of Tell Mohammad Arab, almost all of the pit tombs present a singularity in the form of a side chamber, a feature also present at the site of Umm Kheshm, but rather rare in Northern Iraq. The geographically closest example of clay coffins is that of the Early Sasanian cemetery at Tell Mahuz in Kirkuk province, although details of the excavation are not well documented and only a limited description of the earthenware coffins is available. The coffins were unglazed, with or without a lid (sometimes made in two pieces, probably resembling the lids at the site of Persepolis Spring Cemetery) and with rounded ends, appearing almost oval in shape in two cases (Negro-Ponzi Reference Negro-Ponzi1968–69).

Regarding the container, other Christian coffins have been documented in the cemetery of Umm Kheshm, in al-Hira town (Babil Governorate). However, these coffins were made of wood, and only traces of them were found (al-Haditti Reference al-Haditti1995; al-Shams, Reference al-Shams1987–1988; Ball and Black Reference Ball and Black1987; Roaf and Postgate Reference Roaf and Postgate1981). The closest parallels appear to be those found in the cemetery of Persepolis Spring, located near the site of Persepolis, which was excavated by Schmidt in the late 1950s. The excavation unearthed a total of 31 burials, all of which contained two-piece ceramic coffins. According to Schmidt (Reference Schmidt1957), similar coffins were discovered in Babylon and Susa (Unvala Reference Unvala1929), dated to the Late Achaemenid to Parthian period. However, a notable distinction emerges when comparing the coffins of Gatwa-sûr and Persepolis Spring. The former has a vaulted lid, suggesting a single-piece construction, while the latter’s lids have a near-flat design, indicating a two-piece construction.

From the Assyrian to the Achaemenid period, the “bathtub” coffin type was extensively used throughout all of Mesopotamia. Nevertheless, the example from Gatwa-sûr exhibits no resemblance to this type. Additionally, Parthian burial customs frequently incorporated a distinct type known as the “slipper” coffin, defined as a coffin with or without glaze, featuring a large opening in the head section (Olbrycht Reference Olbrycht and Olbrycht2017). This form was widely used across Central and Southern Mesopotamia, as well as in Iran (Negro-Ponzi Reference Negro-Ponzi1968–69). However, this type differs significantly from the Gatwa-sûr coffin. The use of unglazed earthenware coffins has been documented in Babylon and western Iran during the Achaemenid to Parthian periods (Olbrycht Reference Olbrycht and Olbrycht2017; Richter Reference Richter2011), and this fashion prevailed in western Iran during the Early Sasanian period. Examples of these unglazed clay coffins have been identified in the Persepolis Spring Cemetery (Olbrycht Reference Olbrycht and Olbrycht2017; Schmidt Reference Schmidt1957), at Tepe Golshan, which was dated to the Parthian period (Azandaryani et al. Reference Azandaryani, Habibolah and Khanali2016), and in various locations within the city of Hamedan (Mohamadifar et al. Reference Mohamadifar, Azandaryani, Dailar, Hasanlou and Babapiri2019). The morphology of the coffin of Gatwa-sûr exhibits a high degree of similarity to an unglazed earthenware “bathtub” coffin unearthed in the site of Ashur. The scarce remains that were recovered there belonged to the lower part of the coffin, and the straight rim suggests that it may have originally possessed a lid. The coffin from Ashur, in contrast to the one from Gatwa-sûr, is decorated with grapevine motifs framed by laces with fingerprint impressions. A cross, measuring 15 cm high and 12 cm wide, with a circle at the extremity of each arm, is situated near the base and on one end of the coffin. This significant discovery has been dated from the second to third centuries C.E., belonging to the Late Parthian or the Early Sasanian Period, marking the earliest known example of a coffin with Christian motifs within the region (Hauser Reference Hauser, Kaniuth, Lau and Wicke2018). Another parallel example that is more similar to the Gatwa-sûr coffin, with an anthropomorphic shape, is found in the Parthian necropolis of Susa. This cemetery has coffins with rounded corners and wider upper parts, thus partially imitating the human shape (Kleiss et al. Reference Kleiss, Delougaz, Kantor, Dollfus, Smith, Bivar, Fehérvári, Azarnoush, Dyson, Pigott, Tosi, Sumner, Whitehouse, Stronach, Naumann, Mortensen, Young and Zagarell1975). This form coexists with other types of burials, which are placed in collective semi-subterranean vaulted tombs (Boucharlat Reference Boucharlat and Moradi2019; Boucharlat and Haerinck Reference Boucharlat and Haerinck2011; Rahbar Reference Rahbar1997). More vaulted chamber burials from the first and second centuries C.E. have been found near Susa, at the site of Gelalak. In 1987, four clay Parthian sarcophagi were excavated, presenting more formal divergences from the coffin of Gatwa-sûr. These sarcophagi were rectangular in shape, highly decorated, with glazed surfaces and gabled lids (Olbrycht Reference Olbrycht and Olbrycht2017).

The two crosses adorning the coffin of Gatwa-sûr are composed of four triangular arms, broad at the perimeter and narrow at the center and converging on a central circle or point. This morphology bears resemblance to the cross pattée. If the dots of the cross incised in the coffin are considered as part of the design rather than sketch marks, a resemblance to the type of crosses frequently encountered in Eastern Christianity symbology can be observed (Stewart Reference Stewart, Tang and Winkler2022). Numerous variations of the cross have been identified, reflecting the diverse cultural and historical contexts in which it was used. These variations are found across a broad geographical range, extending from the Near East to China and Tibet, thus underscoring the rapid and extensive dissemination of Christianity during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Notwithstanding the presence of Christians in Northern Iraq since the Late Parthian Period, it was not until the Sasanian Empire (224–651 C.E.) that the motif of the cross pattée appeared in houses, objects, and tombs, being associated with the Church of the East (Hauser Reference Hauser, Pettegrew, Caraher and Davis2019). A significant source of information regarding this matter is a type of stamped pottery, roughly dated to the fifth–seventh centuries C.E., during the Late Sasanian Period, and coincident with Gatwa-sûr’s coffin. These stamps feature Christian crosses of the same type as those adorning the coffin of Gatwa-sûr, accompanied by Zoroastrian motifs consisting of rams and stags with ribbons around their necks (Simpson Reference Simpson2005). These stamped cross motifs have been observed at numerous archaeological sites, including the previously cited Khirbet Deir Situn, and have been reported in archaeological surveys conducted in Iraqi Kurdistan (Gavagnin et al. Reference Gavagnin, Iamoni and Palermo2016). In Iraq, the cross pattée is also present on stelae and a metal pendant from the site of al-Hira (al-Kaabi Reference al-Kaabi2014), a plaque from the site of Kuyunjik (Simpson Reference Simpson2005), and in wall carvings from the site of Hatra (Venco-Ricciardi Reference Venco-Ricciardi, Genito and Caterina2017).

Similar examples of burials with cross motifs ascribed to the early Christian community in the Sasanian period have been identified in Iran. One such example is the island of Kharg, located in the Persian Gulf. It features an important monastic community as well as a Christian church decorated with Sasanian ornamentation. The foundation of this church is thought to date to the third century C.E., and it continued functioning until the eighth century C.E. (Ashurov Reference Ashurov2019). A necropolis composed of more than 120 niche and pit burials has been located on the island’s plateau. An analysis of the burials identified four distinct burial types, which have been initially associated with Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian communities (Haerinck Reference Haerinck1975). The Christian-associated burials are characterised by rectangular coffins, some of which have more squared, rectangular or rounded edges, some have vaulted roofs and an absence of decoration. Initially, the type associated with the Jewish community featured a cross motif resembling the Maltese cross (V-shaped arms, as described by Haerinck Reference Haerinck1975), as well as Syriac inscriptions. However, recent studies have identified these burials as Christian from the Sasanian period (Hauser Reference Hauser, Pettegrew, Caraher and Davis2019). In the area surrounding the site of Istakhr, an ossuary adorned with a cross motif has been discovered. Dating to the Sasanian period, it was initially attributed to a Christian individual (Huff Reference Huff, de Meyer and Haerinck1989), and upon further examination, it was later identified as a Zoroastrian burial (Huff Reference Huff and Stausberg2004). At the site of Susa, pithos burials have been found with cross decorations (Hauser Reference Hauser, Pettegrew, Caraher and Davis2019).

Regarding the content of the burials, a great variety of funerary customs is observed in the Sasanian Empire. In the Mesopotamian region, burials exhibiting Zoroastrian affiliations are uncommon, in contrast to Central Asia in later periods, since the burial pattern is identified as primary and single inhumations (Negro-Ponzi Reference Negro-Ponzi1968–69). The orientation of the deceased exhibits significant variations. The Christian tradition of orienting burials from west to east is evidenced in Sasanian cemeteries such as Tell Mohammad Arab, featuring 69 burials. However, this practice is most commonly observed in more recent necropoleis, including Urgut (Ashurov Reference Ashurov2019; Gilbert Reference Gilbert, Tang and Winkler2022, Reference Gilbert2024; Savchenko Reference Savchenko2023), Ilibalyk (Gilbert Reference Gilbert, Tang and Winkler2022; Voyakin et al. Reference Voyakin, Gilbert and Stewart2020), Kara-Jigach, and Tokmok (Kolchenko Reference Kolchenko and Voyakin2018; Myakisheva Reference Myakisheva2021; Pantusov Reference Pantusov1886), which date from the seventh to the nineteenth centuries C.E. (Fox and Tristaroli Reference Fox, Tritsaroli, Pettegrew, Caraher and Davies2019; Gilbert Reference Gilbert, Tang and Winkler2022; Haas Reference Haas and Tabberne2014). Cemeteries such as Gird-î Bazar (Squitieri Reference Squitieri2020) and Tell Mahuz present multiple variations in the orientation of the burials (Negro-Ponzi Reference Negro-Ponzi1968–69). Orientations that are clearly north-south, such as the burial of Gatwa-sûr, are documented in the Sasanian cemetery of Tell Mohammad Arab (Roaf Reference Roaf1984) and in the Persepolis Spring Cemetery (Schmidt Reference Schmidt1957). The positions of the bodies in Sasanian cemeteries are both flexed and extended (Mousavinia et al. Reference Mousavinia, Nemati and Mortezaei2018; Squitieri Reference Squitieri2020). At the site of Umm Kheshm, the deceased are either extended or flexed; however, in the group of tombs with wooden coffins, the predominant position was flexed (Ball and Black Reference Ball and Black1987). In the Gird-î Bazar and Tell Mohammad Arab cemeteries, the majority of individuals were found in an extended lateral posture position (Squitieri Reference Squitieri2020). At Persepolis Spring, all the deceased were lying in an extended prone position (Schmidt Reference Schmidt1957), as were three individuals at Tell Mohammad Arab (Roaf Reference Roaf1984). In the case of the Sasanian cemetery of Tell Mahuz, the position of the bodies has not been fully recorded. However, based on certain references, a supine position can be inferred.

Anthropological Analysis

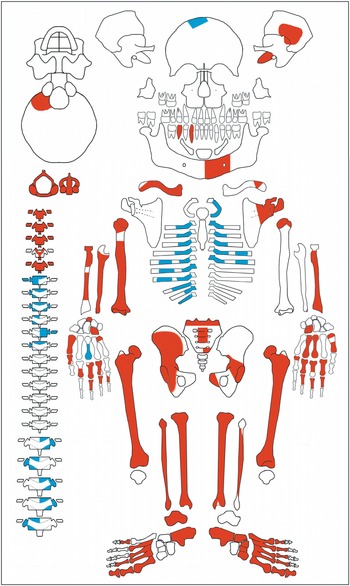

A comprehensive study of the anthropological remains has been conducted. The bones were initially wet or dry cleaned, depending on their state of preservation. Subsequent to this initial preparation, the bones were identified and sided, and then documented in a visual recording form (model provided by Roksandic Reference Roksandic2003) (Fig. 7). Thereafter, the age and sex of the individual were ascertained. Then, the maximum length was measured in all the preserved long bones following White et al. (Reference White, Black and Folkens2011) to perform stature estimation for further demographic studies. Finally, the bones were analyzed for paleopathologies and enthesopathies to reconstruct the lifestyle and health conditions of the buried individual.

Fig. 7. Visual recording form of the individual of Grave 1 from Gatwa-sûr. Red indicates positively identified and sided bones. Blue indicates bones identified but not sided due to uncertainty

The visual recording form allows us to observe that the bones most affected by disturbances were those in the upper part of the skeleton, including the skull, the shoulder girdle, the thorax, the left arm, and the vertebrae. In contrast, the lower part of the body remained better preserved. The majority of the epiphyses were subject to alterations in their mineral composition, undergoing a transformation from cortical to trabecular bone due to the effects of taphonomic processes.

The determination of sex was based on cranial (Acsádi and Nemeskéri Reference Acsádi and Nemeskéri1970) and coxal features (Buikstra and Ubelaker Reference Buikstra and Ubelaker1994). The cranial features that have been preserved include the left mastoid process and the mental eminence. The mastoid process is characterized by its pronounced size, with dimensions that exceed those of the external auditory meatus, resulting in a score of five and an assessment of male. The left side of the mental eminence is projected and scored four, indicating a probable male classification. Coxal features are only discernible in the right os coxae. The greater sciatic notch is characterised by its small and narrow dimensions, which are scored as five and thus classified as male. A thorough analysis of the os pubis and the Phenice traits (Reference Phenice1969) reveals the absence of a ventral arch, a straight subpubic concavity on the dorsal aspect of the pubis and ischio-pubic ramus, and a broad flat surface on the medial aspect of the ischio-pubic ramus. These characteristics are considered male sex traits.

The determination of age was based on the examination of tooth wear attrition and the development of the pubic symphysis from the right os coxae. The analysis of the two preserved teeth was conducted following the Lovejoy system (Reference Lovejoy1985), a method based on dental occlusal attrition patterns. The lower right canine is assigned to Phase E, a category defined by crown loss ranging from 20% to 30%. The age range was determined to be between 24 and 30 years. The second lower right premolar is assigned to Phase G, indicating wear covering the crown but no exposure of the lingual cusp. The age assessment falls within the range of 35 to 40 years. According to the Suchey-Brooks system (Brooks and Suchey Reference Brooks and Suchey1995), the development of the pubic symphysis is assigned to Phase IV in males, characterized by the presence of remnants of the old ridge on the symphyseal face, the possible emergence of bony ligamentous outgrowths in the inferior portion of the pubic bone adjacent to the symphyseal face, and if lipping occurs, it is slight and located on the dorsal border. The 95% range of age is determined to be between 23 and 57 years, with a mean age of 35.2 years. In addition, the Todd system (Reference Todd1920) was employed to assess age. The development observed is classified into Phase 7 in males, characterized by alterations to the symphyseal face, a reduction in activity of the ventral aspect of the pubis, and the presence of bony outgrowths into the pelvic attachments of tendons and ligaments. The age estimation ranges from 35 to 39 years. A comparison of the two systems reveals that Todd’s method offers a more precise estimation of age than Suchey-Brooks system. Based on the analyses of tooth wear attrition and development of the pubic symphysis from the right os coxae, an approximate age of 35 to 50 years is determined. This range falls within the classification of middle adult age as proposed by Buikstra and Ubelaker (Reference Buikstra and Ubelaker1994).

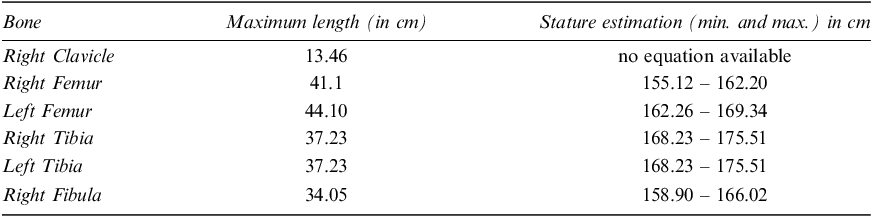

In order to estimate the stature of the buried individual, the maximum length of the best-preserved and complete bones was measured: the right clavicle and fibula, and both right and left femurs and tibias. The majority of the measured bones belongs to the legs, which are more highly correlated with stature than arm bones and provide more reliable stature estimations. The regression equations for white males, according to Trotter (Reference Trotter and Stewart1970), were employed, along with the modification equation for individuals over 30 years of age. The measures and results are displayed in Table 1. The estimated range of stature varied between 155.12 and 175.51 centimeters, with an average of 165.31 centimeters.

Table 1: Maximum length (in cm) of right clavicle and fibula, and right and left femur and tibia. The rest of the bones, due to their state of preservation, could not be measured

The studied bones present several paleopathologies, including tooth loss, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis and infectious periostitis. The preserved fragment of the mandible shows antemortem loss and complete or partial alveolar reabsorption of the left first and second incisors, the canine, the first and second premolars, and the right first and second incisors (Fig. 8d). The loss of these teeth likely resulted in difficulty with activities such as cutting, gripping, tearing, and chewing food. The presence of osteophytes, defined as fibrocartilage-capped bony outgrowths, serves as a diagnostic indicator of degenerative osteoarthritis (Wong et al. Reference Wong, Chiu and Yan2016). These can be found in various bones, including the vertebrae, the shoulder girdle, and the feet. Cervical, thoracic, and lumbar vertebrae present traction and claw osteophytes (Heggeness and Doherty Reference Heggeness and Doherty1998) (Fig. 8c). The articular surface for the manubrium of the right clavicle presents marginal osteophytes, which is usually related to degenerative sternoclavicular joint disease. Capsular osteophytes are also present in the base of the second proximal and distal hallucial right foot phalanges. Osteoporosis is characterized by reduced bone density and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, leading to increased bone fragility and a high risk of fractures (Lin and Lane Reference Lin and Lane2004). The presence of osteoporosis has been identified in the bodies of the vertebrae, in the sacral plateau of the sacrum, and in the acetabular fossa from both os coxae. The latter have macro- and microporosities that were beginning to transform to trabecular bone (Fig. 8b), which is related to the degenerative osteoarthritis that comes through the aging process (Rissech et al. Reference Rissech, Estabrook, Cunha and Malgosa2006). The presence of periostitis, an inflammatory reaction of the periosteum, has also been identified (Baxarias and López Reference Baxarias and López2008; Roberts and Buikstra Reference Roberts, Buikstra and Buikstra2019). This reaction can result from a traumatic injury or bacterial infection (Ortner Reference Ortner and Ortner2003). New periosteal reactive bone formation in the caudal edges and tubercles of the ribs is evident (Figs. 8f, 8g). This pathology has been associated with pulmonary diseases, such as tuberculosis, given the potential for lung diseases to inflame the pleura, which can then affect the bone as it attaches to the visceral surfaces of the ribs, thereby causing an inflammatory reaction on the surfaces of the ribs (Roberts and Buikstra Reference Roberts, Buikstra and Buikstra2019). The diaphysis of long bones from the arms and legs are other bones affected by periostitis. In the right arm, the humerus exhibits periostitis in its anterior surface, while the ulna shows signs of periostitis in its medial surface. In the left arm, the radius is affected with periosteal regrowth around the radial tuberosity, likely resulting from a fracture. The legs present bilateral periostitis: the right leg displays periostitis on the medial side of the femur, in the medial side of the tibia, and in the lateral surface of the fibula; while the left leg exhibits periostitis on the medial side of the femur, the proximal lateral side of the tibia, and the lateral and medial sides of the fibula.

Fig. 8. a) Right clavicle, inferior view. b) Acetabular fossa from a fragment of the left os coxae. c) Fourth cervical vertebrae, superior view. d) Left fragment of the mandible, superior view. e) Third and fourth proximal phalanges from the right hand, palmar view. f) Fragment of a rib, posterior view. g) Fragment of a rib, anterior view. h) Proximal foot phalanx from the right foot, plantar view. i) Right tibia and fibula, lateral and medial view, respectively. j) Right fibula, lateral view

Enthesopathies are defined as injuries that occur at the entheses, where tendons and ligaments attach to the bone. When a muscle is under continuous stress, the tendons or ligaments undergo different tensions that provoke the remodeling of the entheses in the form of bony growths, also called enthesophytes. These injuries are considered musculoskeletal stress or activity markers, resulting from prolonged high-intensity physical activity (Baxarias and López Reference Baxarias and López2008). However, it is important to consider other potential etiologies, including inflammation, trauma, degenerative diseases, endocrine disorders, and metabolic conditions (Resnick and Niwayama Reference Resnick and Niwayama1983). The anatomical and enthesal regions have been identified according to Palastanga, Field, and Soames (Reference Palastanga, Field, Soames, Palastanga and Soames1989). The bones from the buried individual exhibit significant signs of enthesopathies, evident in the shoulder girdle, left arm, both legs, and both feet. In the shoulder girdle, the right clavicle presents enthesophytes in the enthesis for the costoclavicular ligament (Fig. 8a), which connects the shoulder girdle to the thorax and is involved in the pressure and tensions occurring in the upper extremity. Additionally, enthesophytes are present in the conoid ligament, which is in charge of limiting the movement of the scapula. A notably robust conoid tubercle is also observed. The small fragment of the left clavicle exhibits enthesophytes in the rugosity of the enthesis for the deltoideus muscle, which is responsible for arm abduction. In the left arm, the radius displays enthesophytes in the anterior oblique line of the pronator teres enthesis, responsible for pronating the forearm and flexing the elbow. Both hands show significant enthesophyte-related changes in the phalanges, as evidenced by the presence of a pronounced crest in the fibrous sheaths of the proximal and intermediate phalanges (Fig. 8e). It is associated with a developed pulley system in the fingers, as well as increased mechanical strain on the insertions, which may result in a stronger grip (Hermann et al. Reference Hermann, Eshed, Sáenz, Doepner, Ziegler and Hermann2022). This enthesopathy is frequently linked to the manipulation and holding of tools (Baxarias and López Reference Baxarias and López2008). The sum of all the injuries located in the upper limbs could be caused by repetitive and heavy manual activities. The femurs of both legs exhibit enthesophytes along the linea aspera, a bone part where multiple muscles attach, such as the adductor longus, the adductor magnus, the vastus medialis and the vastus lateralis. These muscles are in charge of controlling the movements of adduction and extension of the hips, thighs, and knees, in addition to providing stability to the knee joint. A similar enthesophyte pattern is observed in both tibias and fibulas, with enthesophytes located in the inferior tibiofibular syndesmosis attachment. This attachment plays a role in protecting the ankle joint by gripping upon the talus to prevent displacement of the foot when stopping suddenly while jumping or running (Fig. 8i). Finally, both feet, as well as the hands, exhibit a pronounced crest in the fibrous sheaths of the proximal and distal phalanges, in the entheses for the flexor digitorum longus and the flexor hallucis longus, respectively (Fig. 8h). These muscles are responsible for flexing the toes. This condition is associated with repetitive stress activities, such as running, jumping, walking or standing in the same position for long periods of time, as the toes tend to grip the ground to improve balance.

Bones from this burial also present signs of taphonomic staining and color changes. A light stain of red-brown coloration is identified in the distal part and lateral side of the right fibula (Fig. 8j). One possible origin for this stain could be the corroded iron-based buckle that was found at the feet of the deceased. Repeated disturbances of the burial caused the buckles to shift away from the individual’s legs. However, one buckle was found in close proximity to the right fibula, suggesting it may have been in direct contact with the bone (Dupras and Schultz Reference Dupras, Schultz, Pokines and Steven Symes2014) when it was still part of some form of footwear.

Discussion

Despite the scarce nature of the remains unearthed, the Gatwa-sûr coffin has enabled understanding a unique Christian burial from the Sasanian period in Northern Iraq. This discovery represents a significant advancement in the understanding of the mountainous region of Soran, as it is the first Late Antique Christian burial ever discovered in the area. While limited remains offer valuable insights about stature, sex, age and health of the deceased, they also provide information about the taphonomic processes involved in the burial and the funerary practices. However, the find prompts further questions regarding the social context of the deceased.

Concerning the matter of religious affiliation, numerous textual sources describe a uniform Zoroastrian burial custom throughout the Sasanian Empire, as it corresponds with the empire’s official religion. However, it is evident that the reality was more diverse. The archaeological record demonstrates that at the beginning of the Sasanian period, various religious faiths were able to practice their rites and bury their dead according to their own customs, even if these rituals contradicted common Zoroastrian practices (Simpson Reference Simpson, Gondet and Haerinck2018; Simpson and Molleson Reference Simpson, Molleson, Fletcher, Antoine and Hill2014). The coffin of Gatwa-sûr offers a significant example of the funerary customs of Early Christians in the Mesopotamian region, within the context of a Zoroastrianism majority in the Sasanian Empire, thereby revealing the coexistence of diverse funerary practices within the territory. The Zoroastrian religion allowed for the use of clay coffins as long as the deceased had been previously exposed and excarnated (Mousavinia et al. Reference Mousavinia, Nemati and Mortezaei2018; Simpson and Molleson Reference Simpson, Molleson, Fletcher, Antoine and Hill2014; Squitieri Reference Squitieri2020). This practice was not followed by Christians and Jews, who considered the exposure of human remains in a dakhma to be unholy (Olbrycht Reference Olbrycht and Olbrycht2017). Nevertheless, secondary depositions were also practiced not only by Zoroastrians but also by wealthy members of the Jewish community in their funerary rites from the second to the end of the third century C.E. The deceased were shrouded and buried in cave tombs, a space characterized by niches and an acrosolium. Following a one-year period, the bodies were collected and finally buried in ossuaries, often shaped like chests (Hachlili Reference Hachlili2005; Holzapfel et al. Reference Holzapfel, Chadwick, Judd, Wayment, Holzapfel, Judd and Wayment2008).

In the region of Adiabene in Northern Iraq, burials from Sasanian cemeteries have been associated with Christianity based on certain characteristics of the containers or contents (Gird-î Bazar), or due to the significance of Christian communities in the vicinity (Tell Mahuz). However, the religious affiliation of these populations remains a subject of debate given the absence of clear evidence linking them to Christianity. While the absence of Zoroastrian practices and the existence of significant Christian communities within the region of Adiabene might suggest an affiliation with Christianity, the absence of Christian symbology on graves complicates the interpretation of the findings. Therefore, the present study emphasizes the importance of performing a thorough archaeothanatological analysis to accurately infer the religious affiliation of a burial. Conducting a multi-proxy study is of vital importance, as the accumulation of data concerning the containers (including their morphology and decoration motifs or symbology) and the contents of the burials (including the treatment, orientation, and position of the deceased, as well as the ornaments or offerings present) will facilitate a successful interpretation of the burial. The importance of performing archaeothanatological analyses is also observed in sites such as Mizdachakhan, located in western Uzbekistan. The debate among researchers in assigning the burials to one religious faith or another is due to the complexity of the funerary practices, which consist of secondary deposits in ossuaries with cross mark decorations. This type of deposition poses a challenge to the association of the cross marks with Christian iconography (Baumer Reference Baumer2016; Pavchinskaya Reference Pavchinskaya2019). The burial of Gatwa-sûr, which consists of a Christian burial defined by an earthenware coffin with cross motifs, can facilitate the determination of the religious affiliation of different burial practices to Early Christianity. This is particularly relevant in Central Asia, where the funerary contexts belonging to the period of the dissemination of Christianity are difficult to interpret due to the wide variety of proxies, as is the case with the site of Mizdachakhan. Consequently, further fieldwork at the site of Gatwa-sûr is encouraged, to enhance our understanding of Early Christianity burial practices in the region.

Notwithstanding the repeated disturbances to the Gatwa-sûr burial over ancient and modern times, which altered the original position of the deceased’s bones, age and sex have been positively assessed through dental attrition and the development of the pubic symphysis, as well as skull and coxal sexual traits, respectively. Paleopathological analysis has provided insight into the health state of the individual, revealing issues such as teeth loss, degenerative osteoarthritis, osteoporosis and infectious periostitis. This mid-adult male’s clinical profile suggests challenges with eating and mobility. His body would be quite fragile and susceptible to fractures due to bone mass loss, exacerbated by bacterial infections which could have originated from microfractures in the long bones and potentially contributed to the development of pulmonary diseases. The enthesopathies observed in the bones, however, are indicative of a person engaged in strenuous physical activities. The presence of developed musculoskeletal stress markers are associated with a strong grip in the hand and feet, as well as heavy use of the upper extremities, suggesting that the individual primarily relied on their body for demanding labor involving the upper and lower limbs. This activity likely involved prolonged periods of standing and repetitive manual tasks using tools that placed significant musculoskeletal stress on the shoulder girdle and the upper limbs. The use of rudimentary tools, such as hoes or axes, for activities like chopping wood or plowing fields, is proposed. Regarding the estimation of the deceased’s stature, Trotter’s regression equations were followed due to the absence of references for stature among West Asian populations. Given that this method is based on data from the Terry Collection, which includes 255 male individuals and 710 white male North American soldiers who fought in World War II, the interpretation of stature estimation must be taken with caution and considered as an initial approximation for demographic studies.

Conclusions

The site of Gatwa-sûr offers a glimpse into the rich archaeological heritage of the Zagros area of the Kurdistan region of Iraq. This initial view of the site is undoubtedly a first step toward understanding a location of unknown size, likely much larger than what is currently perceived. This discovery underscores the importance of protecting archaeological sites beyond well-known, protected areas, bringing attention to both society and cultural institutions. Involving residents and archaeologists in both fieldwork and laboratory investigations is a crucial step in raising awareness about the significance of these sites and the importance of avoiding disturbance or destruction, particularly in contexts where religious or cultural factors are a concern.

The involvement of several Kurdish mass media outlets, which included coverage of the excavation and findings, as well as the conducting of interviews, has led to a substantial increase in awareness among the regional population regarding the relevance of Gatwa-sûr. This engagement has also prompted authorities to consider extending protection to such sites and conducting additional preventive interventions in rural and remote regions, such as this mountainous landscape.

From an archaeological perspective, Gatwa-sûr is of particular interest due to the scarcity of evidence for Early Christian coffin burials in Northern Iraq, particularly considering the religion’s prominence during the Sasanian era in the region. The presence of Christian symbols adorning the coffin, including two crosses, is unique. No other examples of Sasanian period clay sarcophagi displaying crosses or other Christian symbols with such clarity have been found, despite the likely existence of Christian cemeteries in the region. Additionally, no settlements or religious buildings have been discovered yet, which is unsurprising given the lack of comprehensive and systematic surveys in the area.

In summary, the Gatwa-sûr coffin must be understood within the context of an empire characterized by religious diversity, where various faiths influenced many aspects of ancient life. However, this diversity may not always be evident in the archaeological record, as evidence for beliefs is often perishable and easily overlooked. Therefore, identifying rituals with clear connections to specific religions can aid in understanding burial customs, regional fashions, and particularities.

It is noteworthy that the closest parallels to Gatwa-sûr are found in the Early Sasanian period; however, numerous similar earthenware coffins have been discovered in Parthian and even Late Achaemenid contexts. The dating of this coffin highlights the transmission and endurance of burial customs across Mesopotamia, spanning different periods and surviving within various religious traditions. In this context, the Gatwa-sûr coffin makes a substantial contribution to our understanding of the complexity of society during the Sasanian period while also revealing the scarcity of material evidence and archaeological projects focused on this period.

It is evident that a single burial offers a limited amount of historical and archaeological information, as the presence of a single findspot prevented comprehensive comparisons with other funerary grounds in the area and beyond. The site of Gatwa-sûr holds great potential for further exploration, as the area has not been systematically surveyed and only a very brief intervention has been carried out. The interest demonstrated by the local authorities of the province of Soran, particularly the head of the directorate, Mr. Abdulhawab Suliman, in the preservation of discovered archaeological sites, has enabled the continuity of future explorations in the region. Subsequent investigations in this area are expected to yield additional data and further expand the historical scope of the site of Gatwa-sûr.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the General Directorate of Antiquities of Kurdistan for promoting the salvage excavation and documentation of this site, as well as for inviting the SAPPO-GRAMPO Research Group from the Autonomous University of Barcelona to perform the fieldwork and further research. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge Osman Ibrahim Abbas (the landowner) and his sons, Saman Osman Ibrahim, Sardar Osman Ibrahim and Dlawar Osman Ibrahim, for reporting the discovery, collaborating in the field excavation, and protecting the site. We thank the archaeologists Twana Abubakir from the Department of Archaeology of Salahaddin University, and Hidayet Hussein and Shler Ahmed Hussein from the General Directorate of Antiquities of Kurdistan (Soran District) for their work in the field; and Biel Soriano Elias from the SAPPO-GRAMPO Research Group for his help in elaborating the map of Gatwa-sûr. Special thanks are also extended to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments that have significantly enhanced the quality of this study. Their expertise has provided a substantial contribution to the topics covered in this research.

Funding details

This study has been funded by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (PID2022-139164NB-C21), the SAPPO-GRAMPO Research Group (2021 SGR 00744) and the Directorate of Antiquities of Kurdistan (Soran District). Alicia Gluitz was granted an FPU research scholarship from the Spanish Ministerio de Universidades (FPU20/03612), a support that has enabled the completion of this study.